Abstract

Talent designation is one of the most sensitive and controversial topics in talent management. As organisations adopt workforce differentiation practices, a subset of employees is often considered ‘talent’, while other employees may implicitly perceive ‘non-talent’ status. Taking a social comparison perspective, we examine under which conditions employees are more likely to respond positively or negatively to perceived non-talent designation. Specifically, we draw on research on personal goals and extend the self-evaluation maintenance model. We argue that, contrary to common assumptions, perceived non-talent designation may not universally cause negative responses. Comparison can be experienced as inspiration or envy – depending on the relevance of talent status to one’s identity, attainability of talent status in the future, and a multitude of micro-, meso-, and macro-level contextual factors. This, in turn, shapes both employees’ approach motivation to gain talent status and self-serving attributions to defend non-talent status. In doing so, we provide a more nuanced understanding of employee reactions to perceived non-talent designation and highlight the value of dynamic talent designation in organisations.

1. Introduction

Talent designation, defined as ‘an organization’s assignment of talent status to an employee’ (Tyskbo & Wikhamn, Citation2023, p. 684), has been identified as a critical event that alters expectations and substantially shapes the employee-organisation relationship (King, Citation2016). Given the associated workforce differentiation (Marescaux et al., Citation2021), employee reactions to talent designation have emerged as one of the most sensitive topics in talent management (Sumelius et al., Citation2020). The extent to which organisations communicate talent designations and differentiate their workforce remains controversial (Swailes, Citation2013), particularly in the context of creating inclusive workplaces and adopting more inclusive talent management approaches (Dries & Kaše, Citation2023; Kaliannan et al., Citation2023). The purpose of this study is to examine under which conditions employees are more likely to respond positively or negatively to perceived ‘non-talent’ designation.

Talent management can broadly be defined as the attraction, identification, development, retention, and deployment of ‘talent’ (Vaiman et al., Citation2012). It commonly entails a disproportionally high investment in individuals, who are deemed to possess the requisite knowledge, skills, and abilities to succeed in pivotal positions (Collings & Mellahi, Citation2009). This often results in a broad segmentation of the workforce into two groups: employees with ‘talent’ status and employees with perceived ‘non-talent’ status (Gelens et al., Citation2014). In practice, it is unlikely that employees will receive such an explicit designation. However, as firms adopt approaches that differentiate the workforce, talent pool inclusion/exclusion for a subset of employees is a salient feature (Björkman et al., Citation2013; Jooss et al., Citation2021b). Depending on the level of awareness of differential treatment (Ehrnrooth et al., Citation2018; Sonnenberg et al., Citation2014), exclusion from a talent pool does at least implicitly convey non-talent status (Daubner-Siva et al., Citation2018). In addition to inclusivity concerns, this also remains controversial because too often there is either no clarity on the meaning and identification of talent or a too narrow perspective of what talent may entail is adopted (Vardi & Collings, Citation2023). While research has examined the meaning of talent and developed multiple approaches to better understand this construct (e.g. Gallardo-Gallardo et al., Citation2013; Meyers et al., Citation2020), it is most commonly associated with the identification of high-performing and high-potential individuals (Jooss et al., Citation2021a; McDonnell et al., Citation2017).

Research is largely built on the premise that talent management positively impacts organisational performance and individuals’ careers (McDonnell et al., Citation2017; Swailes, Citation2020). However, it does not paint a clear picture on employee reactions to talent or perceived non-talent designation (Boonbumroongsuk & Rungruang, Citation2022; Tyskbo & Wikhamn, Citation2023). Most research on employee reactions focuses on the relationship between an individual’s talent status and affective, cognitive, and behavioural outcomes (De Boeck et al., Citation2018; Gelens et al., Citation2013). A general assumption is that employees who have been designated as talent exhibit higher levels of positive work attitudes and behaviours than other employees (De Boeck et al., Citation2018; Sonnenberg et al., Citation2014). For example, these attitudes and behaviours include commitment, satisfaction, motivation, engagement, trust, performance, and effort (De Boeck et al., Citation2018). More recently, scholars have also considered the potential negative consequences of talent designation, such as performance pressures, powerlessness, frustration due to unmet career expectations, and work-life balance struggles as well as jealousy or resentment from others (e.g. Daubner-Siva et al., Citation2018; Petriglieri & Petriglieri, Citation2017; Tansley & Tietze, Citation2013; Tyskbo & Wikhamn, Citation2023; van Zelderen et al., Citation2023).

In contrast, our knowledge of work attitudes and behaviours as a response to exclusion from a talent pool is limited (Dries & Kaše, Citation2023); the basic tenet often being that it is unlikely that employees react any other than negatively to their perceived non-talent designation (Krebs & Wehner, Citation2021). Non-talent designation signals decision-makers’ disbelief in an employee’s potential (Sumelius et al., Citation2020; Swailes & Blackburn, Citation2016) and generally results in less access to resources and opportunities in comparison to those employees designated as talent (Swailes, Citation2013). Therefore, it bears significant ethical risks (Painter-Morland et al., Citation2019) and raises concerns around employees’ commitment (King, Citation2016) and organisational citizenship behaviour (Wikhamn et al., Citation2020). Adverse and unintended reactions such as identity threat, questioning the fairness of the designation process, harming behaviours directed at talents, withdrawal behaviours, and a drop in performance may likely follow (Krebs & Wehner, Citation2021; Malik & Singh, Citation2014; Sumelius et al., Citation2020). However, non-talents may also react positively in that they may focus on self-improvement and view stress as a challenge rather than a threat (Zhou et al., Citation2023).

How employees respond to being excluded from a talent pool has traditionally received little theoretical attention (De Boeck et al., Citation2018; Ehrnrooth et al., Citation2018). However, in recent years, several studies have focused on the ‘non-talent’ cohort; for example, van Zelderen et al. (Citation2024) found that employees identified as talents and non-talents reacted more favourably to exclusive, secretive practices than to inclusive, transparent practices. They refer to this phenomenon as ‘the paradox of inclusion’ where practices designed to be more inclusive may decrease individuals’ perceived inclusion. Dries and Kaše (Citation2023) examined perceived fairness of talent management, finding a clear effect of talent status, in that self-interest impacts these perceptions. They further found that preferred allocation norms, that is, being for or against the idea of merit-based allocations, impacts fairness perceptions. Yet, we argue that our relatively sparse knowledge on employee reactions to perceived non-talent designation is a limiting aspect in the effective design and communication of talent management approaches.

Responding to Troth and Guest’s (Citation2020) call for multi-disciplinary research, integrating psychology in talent management, our paper takes a social comparison perspective (Greenberg et al., Citation2007) to gain insights on employee-centred reactions. In doing so, we recognise employees as critical stakeholders in talent management. Specifically, we draw on research on personal goals (Brunstein, Citation1993) and extend the self-evaluation maintenance model (Tesser, Citation1988) to propose a conceptual model of social comparisons upon perceived non-talent designation. Tesser’s (Citation1988) model allows us to unpack how individuals engage in social comparisons to maintain or enhance their self-evaluation while Brunstein’s (Citation1993) work is utilised to consider the role of perceived possibility of gaining talent status in shaping social comparisons. Addressing the call for more research on non-talents (De Boeck et al., Citation2018; Wikhamn et al., Citation2020), we ask in our conceptual paper: Under what conditions do employees react more positively or negatively to perceived non-talent designation?

Our paper provides two primary contributions to the talent management literature. First, we provide a more nuanced understanding of employee reactions to perceived non-talent designation. We argue that, contrary to common assumptions, perceived non-talent designation may not universally cause negative responses, and we contend that individuals may experience social comparison as either inspiration or envy. We note the relevance of talent status to one’s identity and attainability of talent status in the future as two critical conditions which impact the social comparison experience. Further, we illustrate that this, in turn, shapes employees’ approach motivation to gain talent status in the future and self-serving attributions to defend non-talent status. At the same time, we acknowledge that a multitude of micro-, meso-, and macro-level contextual factors impact the social comparison experience. Ultimately, we suggest a more refined perspective when drawing conclusions on employee reactions, detailing conditions which are more likely to lead to negative or positive reactions.

Second, we highlight the value of dynamic talent designation practices in organisations. Conceptually, this is illustrated in extending the self-evaluation model with an attainability component. In practice, at an individual level, the focus on attainability recognises the potential for self-development and changes in talent status over time. At an organisational level, attainability should become a salient feature in discussions, moving away from more static approaches to talent management and fixed talent status towards more dynamic (i.e. potentially changing) talent designations. Combined, these insights indicate that organisations may adopt workforce differentiation practices as part of their talent management approach without necessarily leading to adverse reactions from non-talents. This is noteworthy as firms continue to seek effective investments in talent while also increasingly striving for inclusive workplaces.

2. A Social comparison perspective on employee reactions

2.1. Social comparison in organisations

Social comparison refers to the comparison of individuals in relation to others in social contexts (Greenberg et al., Citation2007). Social comparison theory (Festinger, Citation1954) suggests that individuals have an inherent need to self-evaluate their abilities and performance; notably, some individuals might engage more in social comparisons and are more sensitive to the outcomes of the comparison process than others (Buunk & Gibbons, Citation2007). As part of social comparison, a set of both positive and negative emotions can be experienced (Gerber et al., Citation2018). Aligned with research on social comparison emotions (e.g. Boekhorst et al., Citation2024; Watkins, Citation2021), we distinguish between inspiration and envy as our two central emotions experienced during social comparison. Inspiration refers to a positive affective state that encompasses three aspects: evocation (external source evokes inspiration), transcendence (awareness of desirable possibilities), and motivation (motivation to realise these possibilities) (Boekhorst et al., Citation2024; Thrash & Elliot, Citation2004). Envy is defined as ‘the painful emotion experienced when one lacks and desires others’ superior qualities, achievements, and possessions’ (Duffy et al., Citation2012, p. 643; for a review on workplace envy, see Duffy et al., Citation2021).

In an organisational setting, social comparison processes have been utilised to explain a range of phenomena, for example, organisational justice, performance appraisals, virtual work environments, affective behaviours, stress, and leadership (Greenberg et al., Citation2007). In contrast, social comparison theory has received relatively little attention in the talent management literature (for exceptions, see van Zelderen et al., Citation2024; Zhou et al., Citation2023) despite its strong relevance when considering performance evaluations of employees (Suls & Wheeler, Citation2013). This might be due to the ongoing challenge of establishing more multi-disciplinary research in the talent management field (McDonnell et al., Citation2017), with a particular need to integrate psychological research (Troth & Guest, Citation2020). Several studies have drawn on social comparison theory in the context of workforce differentiation (e.g. Koch & Marescaux, Citation2021; Schmidt et al., Citation2018). These studies have highlighted the potential negative reactions to workforce differentiation when engaging in social comparison, possibly undermining investments made in talent-designated employees. For example, individualised resources and arrangements, so-called ‘i-deals’, might trigger envy in a social comparison process (Marescaux et al., Citation2019) and talents might become a target of victimisation, i.e. experience harmful interpersonal behaviour (Kim & Glomb, Citation2014).

2.2. The self-evaluation maintenance model

Taking a social comparison perspective, we utilise Tesser’s (Citation1988) self-evaluation maintenance model to better understand employee reactions to perceived non-talent designation. This model is built on the premise that individuals compare themselves with salient others which can lead to both positive and negative reactions. It further assumes that individuals strive to maintain or enhance their self-evaluation and that their relationships with others impact their self-evaluation (Suls & Wheeler, Citation2013). The self-evaluation maintenance model has three core components that interact with each other to affect an individual’s self-evaluation when engaging in social comparisons: (1) level of performance, (2) psychological closeness to the comparing person, and (3) relevance of the performance domain to one’s identity. Considering the level of performance, an individual might find that the person they are comparing to has a higher, lower, or the same level of performance. In terms of psychological closeness, Tesser (Citation1988) distinguishes between psychologically close (e.g. family member, friend, or a co-worker in the same team) and psychologically distant (e.g. an acquaintance or an employee from another function) when considering the relationship between an individual and the comparing person. For the purpose of this paper, we conceptualise psychological closeness as a feeling of attachment and perceived connection (Tajfel et al., Citation1971), which may also lead to increased levels of awareness and knowledge about the co-worker’s job and performance. High psychological closeness is more likely to exist where co-workers share a common identity or other similarities; in contrast, low psychological closeness is more likely to exist where co-workers have no common identity or similarities; collocation, geographical area, and level of interactions may impact psychological closeness, but one might also develop psychological closeness with co-workers in a virtual context. Finally, in a social comparison process, we might find high or low relevance of the performance domain to an individual’s identity, meaning the level of performance in a particular domain, for example, sports, music, business, etc., is more or less important to a person (Tesser, Citation1988).

Whether the social comparison is experienced as inspiration or envy is particularly determined by the relevance of the performance domain to an individual’s identity (Tesser, Citation1988). The assumption is that only a small subset of performance domains are relevant to an individual’s identity. When comparing one’s performance with a psychologically close person who has achieved high performance, an individual might derive inspiration by ‘basking in the reflected glory’ (Cialdini et al., Citation1976, p. 366). However, an individual can also experience envy when feeling outperformed, and the social comparison may result in ‘potential harm to the value, meanings, or enactment of an identity’ (Petriglieri, Citation2011, p. 644). In sum, the self-evaluation maintenance model suggests that social comparisons with higher-performing individuals only have negative implications when the other person is psychologically close and the performance domain relevant to one’s identity.

2.3. Extending the self-evaluation model with an attainability component

Drawing on research on personal goals (Brunstein, Citation1993), we propose an extension of the self-evaluation maintenance model by including a fourth component—attainability of superior performance in the future. Attainability can be defined as the perceived possibility of being able to achieve a particular outcome (e.g. higher performance) with a reasonable amount of effort (Lockwood & Kunda, Citation1997). We view attainability as an important component for two reasons. First, at an individual level, it recognises the ‘possibility for self-improvement’ (Tesser, Citation1988, p. 189) and the underexplored role of proactivity in talent management (Meyers, Citation2020). Second, at an organisational level, it reinforces the need to move away from more static approaches to talent management and fixed talent status towards more dynamic talent designations, which can increase organisational agility (Jooss et al., Citation2024).

Research has conceptualised goal achievement as a tripartite construct composed of progress in goal achievement, the attainability of goal achievement, and commitment towards goal achievement (Brunstein, Citation1993). Each of these dimensions is directly relevant to social comparisons: First, being outperformed reflects lower or slower goal achievement by an individual; second, being outperformed can be experienced as inspiration or envy, depending on an individual’s attainability of the same level of performance; and third, it can decrease or increase commitment towards goal achievement through its effect on an individual’s self-evaluation. Ultimately, we argue that an individual’s attainability of the comparing person’s level of performance attenuates the negative implications of the comparison process. This is because the comparison process is seen as more motivating rather than discouraging; instead of feeling inferior, an individual may feel empowered, resulting in a more positive self-evaluation (Tesser, Citation1988).

In sum, a social comparison perspective (Greenberg et al., Citation2007) and the extended self-evaluation maintenance model provide us with a theoretical foundation to consider reactions of non-talents when comparing themselves with talents. In the following, we introduce our conceptual model of social comparisons upon perceived non-talent designation.

3. Social comparisons upon perceived non-talent designation

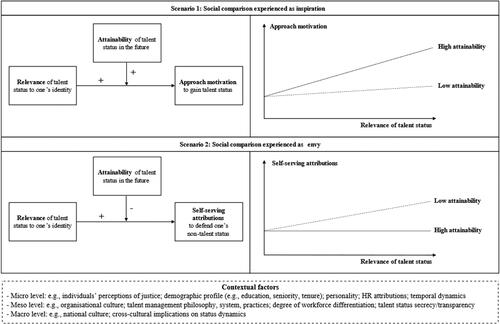

presents our conceptual model encompassing two scenarios of social comparisons upon perceived non-talent designation. In the first scenario, individuals experience social comparisons with talent-designated, psychologically close co-workers as inspiration. In the second scenario, individuals experience social comparisons with talent-designated, psychologically close co-workers as envy. The model is built on core components of the extended self-evaluation maintenance model (i.e. relevance and attainability). Additionally, we introduce two employee-centred reactions as a response to perceived non-talent designation that have important implications for how employees act upon this designation: approach motivation and self-serving attributions. For our argumentation, level of performance relates to the talent designation outcome (i.e. talent or perceived non-talent status) and psychological closeness refers to the proximity to the co-worker compared to. Importantly, our conceptual model is premised on high performance (talent status) and high psychological closeness (e.g. sharing a common identity or other similarities) of the comparing person.

Figure 1. Social comparisons upon perceived non-talent designation. Note: The model is premised on high performance (talent status) and high psychological closeness of the comparing person.

First, following the conceptualisation of the self-evaluation maintenance model (Tesser, Citation1988), it is critical to understand the relevance of the performance domain, in our case talent status, for one’s identity. An employee might view talent designation as an important aspect of their career, taking a high priority in their life (high relevance). Talent status is often associated with additional economic and socio-economic resources for employees (Wikhamn et al., Citation2020). Economic resources are tangible benefits which relate to increased investments by organisations, leading to greater development and career advancement opportunities (e.g. Björkman et al., Citation2013; Gelens et al., Citation2015). Socio-economic resources are symbolic in nature and address social and esteem needs (e.g. Cropanzano & Mitchell, Citation2005; De Boeck et al., Citation2018). Alternatively, an employee might prefer other forms of recognition or prioritise non-work aspects (low relevance). Given the ‘mixed blessing’ of talent designation (Daubner-Siva et al., Citation2018; Tyskbo & Wikhamn, Citation2023), desirability of talent status may vary. Individuals may choose to opt out of such conferrals given the potential negative consequences of being named talent for oneself, within and outside the workplace, for example, performance pressures or work-life imbalance (Kirk, Citation2021). Similarly, we note that how others view oneself (Scheff, Citation2018) may also impact the desirability of talent designation. Both the management (e.g. Hendricks et al., Citation2023) and psychology (e.g. Call et al., Citation2015) literatures have examined how talentsFootnote1 are viewed by non-talents. For example, non-talents might consider talents as role models, potentially enhancing self-efficacy through vicarious experience (Hendricks et al., Citation2023). In such a scenario, talent status might be positively viewed by talents given the positive reactions from non-talents. However, research also highlights the oftentimes more negative reactions, including feelings of envy from non-talents (Campbell et al., Citation2017) and victimisation of talents (Kim & Glomb, Citation2014), leading to a ‘burden of elitism’ (Kamoche & Leigh, Citation2022, p. 817). As talents are likely affected by unfavourable treatment of non-talents as a result of social comparisons, some individuals may view talent status as less desirable (Kehoe et al., Citation2022). In sum, we base our theoretical analyses on the premise that a social comparison of a non-talent with a talent is only leading to inspiration or envy when there is a high relevance of talent designation.

Moreover, we argue that the higher an individual’s attainability to achieve talent designation, the less an individual will perceive their identity to be threatened and the more they will derive inspiration from social comparison. In many organisations, ‘talent reviews’ are conducted on a regular basis (i.e. every six to twelve months) as part of which managers identify talents that contribute to the firm, aligned with current and future business needs (Jooss et al., Citation2021b; Mäkelä et al., Citation2010; Zesik, Citation2019). These calibration sessions are utilised by organisational leaders to make decisions related to development, promotions, and succession planning (Church et al., Citation2021). Given the general practice of reassessing talent status during these meetings, employees can gain talent status during a future talent review meeting if they were not designated as talent. While several factors impact talent designation (e.g. perceptions, prototypes, and impression management; see Finkelstein et al., Citation2018), attainability will particularly be shaped by employees’ performance and potential (Church et al., Citation2021; Jooss et al., Citation2021a). Performance is often evaluated considering quantitative key performance indicators (KPIs) and qualitative competency assessments (for a review on performance appraisal, see DeNisi & Murphy, Citation2017). Potential is either evaluated based on changes to performance ratings over time or on the basis of more formal assessments of various indicators of potential (Church et al., Citation2021). These indicators include, for example, analytical skills, cognitive abilities, emergent leadership, drive, learning agility, personality, and social competence (for models of potential, see Dries & Pepermans, Citation2012; Finkelstein et al., Citation2018; Silzer & Church, Citation2009). Thus, we contend that low/high attainability depends on individuals’ capability to demonstrate performance and show potential, as well as organisations’ talent review processes, facilitating regular reassessment of talent status.

Proposition 1a: Individuals experience social comparisons with talent-designated psychologically close co-workers as inspiration if relevance of talent status and attainability of talent status in the future are high.

Proposition 1b: Individuals experience social comparisons with talent-designated psychologically close co-workers as envy if relevance of talent status is high, but the attainability of talent status in the future is low.

Second, we argue that individuals who experience social comparisons as inspiration will, in turn, increase their approach motivation (Harmon-Jones et al., Citation2013) towards goal achievement (i.e. talent status). Approach motivation can be defined as ‘eagerly focusing on where one wants to go, striving for desired end-states’ (Scholer et al., Citation2019, p. 111). We suggest that approach motivation is a key variable when considering talent designation given its crucial role in enhancing employee engagement and performance (Harmon-Jones et al., Citation2013). Oftentimes, approach motivation relates to an impulse towards positive stimuli and goals (Lang & Bradley, Citation2008). In that sense, comparison with a talent-designated co-worker inspires an individual if talent status is relevant to an employee’s identity and attainable in the future. Approach motivation is reinforced where organisations regularly reassess talent status, providing employees with the opportunity to strive for their desired goals, subject to demonstrating performance and showing potential.

This situation is likely to occur when, for example, junior employees or recent hires compare themselves with more senior or longer-tenured psychologically close co-workers who have received talent designation because of a strong performance track record over time. Junior employees and recent hires could not develop the same performance track record yet but may well do so by the time they reach the same level of seniority or tenure. This is particularly the case if non-talents are able to show potential, utilising their learning agility (Finkelstein et al., Citation2018) to translate experiences into applicable knowledge, often resulting in higher performance in the long term. Increased approach motivation can be expected in cases where the profiles of the two employees are very similar in terms of other characteristics such as educational background and qualifications (Tesser, Citation1988). In this context, comparison can be construed by a non-talent to perceive themselves similar to a talent (Collins, Citation1996). We propose that such comparison will inspire non-talents, leading to an increase in approach motivation, i.e. a positive reaction despite perceived non-talent designation.

Proposition 2: Individuals who experience social comparisons as inspiration are more likely to have increased approach motivation than those who do not (or than those who experience it as envy).

Third, we contend that individuals who experience social comparisons as envy will, in turn, increase their self-serving attributions (Bradley, Citation1978). Self-serving attributions can be defined as attributions made by individuals to assign positive outcomes to internal factors such as effort and ability while attributing negative outcomes to external factors beyond one’s control such as luck or task difficulty (Hamilton & Lordan, Citation2022; Rudolph et al., Citation2015). Self-serving attributions can be considered as an example of a more general set of flawed self-assessments that are quite commonplace, particularly when experiencing envy in the workplace and when coping with performance pressures (Duffy et al., Citation2021). Taking a more positive perspective on self-serving attributions, they are also considered defensive biases through which individuals alleviate identity threat, thus protecting self-esteem (Hamilton & Lordan, Citation2022).

Self-serving attributions are often made unconsciously by individuals ‘who overestimate the informativeness of positive outcomes about their ability, as they take too much credit for their achievements, and they underestimate the informativeness of negative outcomes, as they hold external contingencies responsible for any failures’ (Hestermann & Le Yaouanq, Citation2021, p. 199). Thus, the latter is particularly relevant upon perceived non-talent designation as an outcome of a talent review. We suggest that following an identity-threatening social comparison, employees will potentially engage in self-serving attributions which rationalise their own (inferior) performance (Campbell & Sedikides, Citation1999; Hamilton & Lordan, Citation2022). For example, for employees who did not achieve talent status in a talent review, it is tempting to attribute a talent-designated psychologically close co-worker’s success to external factors such as luck or task difficulty rather than internal factors such as effort and ability (Rudolph et al., Citation2015).

We argue that attainability of talent status in the future will impact to what extent employees seek out ways to reduce the potential identity threat, i.e. engage in self-serving attributions (Brunstein, Citation1993). When an organisation’s talent review process does not regularly reassess talent status, employees may view the attainability of talent status in the future as low, increasing their self-serving attributions. This might be particularly the case when the profiles of a talent and a non-talent are very similar in terms of seniority and tenure as well as other characteristics such as educational background and qualifications (Tesser, Citation1988). In contrast, when a senior or longer-tenured psychologically close co-worker has been designated as talent, a more junior employee or recent hire might reflect on gaining talent status in the future through demonstrating performance and showing potential over time. We suggest that gaining insights into self-serving attributions is critical as these attributions can subsequently impact a range of areas such as well-being, motivation, interpersonal relationships, personal and professional growth, and performance accountability (Hestermann & Le Yaouanq, Citation2021).

Proposition 3: Individuals who experience social comparisons as envy are more likely to use self-serving attributions than those who do not (or than those who experience it as inspiration).

4. Discussion and conclusions

This conceptual paper elucidated under what conditions employees react more positively or negatively to perceived non-talent designation. In doing so, we explicitly focused on a group of employees which, to date, has been underexplored in the talent management literature—non-talents (De Boeck et al., Citation2018). We took a social comparison perspective (Greenberg et al., Citation2007) to better understand how social comparisons upon perceived non-talent designation are experienced and we examined two important employee-centred reactions. In the following, we present our theoretical contributions, practical implications, and limitations and future research suggestions.

Our paper provides two primary contributions to the talent management literature. Our first contribution stems from developing a more nuanced understanding of employee reactions to talent management (De Boeck et al., Citation2018), specifically, reactions to perceived non-talent designation. Conceptually, we propose a model of social comparisons upon perceived non-talent designation (). Our second contribution derives from building theory by extending Tesser’s (Citation1988) self-evaluation maintenance model with an attainability component. Consequently, we argue for a move from static to dynamic talent designation practices in organisations, making attainability a salient feature in talent management discussions. The combined insights from our two primary contributions indicate that organisations may adopt workforce differentiation practices as part of their talent management approach without necessarily leading to adverse reactions from non-talents.

Our study expands the discourse on employee reactions in talent management which has reported significant differences between talents and non-talents (De Boeck et al., Citation2018) but largely neglected interindividual differences in the responses among non-talents. We argue that, contrary to common assumptions, perceived non-talent designation may not universally cause negative responses, and we contend that individuals may experience social comparison as either inspiration or envy. Importantly, we delineate two critical conditions which impact the social comparison experience—the relevance of talent status for one’s identity and the attainability of talent status in future talent reviews. We contend that these conditions, in turn, shape approach motivation to gain talent status in the future and self-serving attributions to defend non-talent status.

Individual-level studies have painted a relatively bright picture on employee reactions towards talent status (De Boeck et al., Citation2018). However, unintended adverse effects on non-talents have not been depicted in most studies. Yet, some scholars have highlighted that such effects may pose severe challenges to companies (Painter-Morland et al., Citation2019; Swailes, Citation2020). Our paper suggests that these concerns are supported in some contexts, but less justified in other contexts; focusing on the attainability of talent status in particular, we challenge the general assumption that employees always react negatively to perceived non-talent designation. While this assumption stems largely from concerns that non-talents feel excluded (Swailes, Citation2013), our conceptual model indicates that perceived non-talent designation does not universally cause negative responses if talent status is attainable in the future. We contend that this requires an organisational setting where talent status is regularly reassessed, providing employees with the opportunity to demonstrate performance and show potential over time. In sum, we illustrate a case for relevance and attainability to be more centrally placed in discussions on employee reactions to perceived non-talent designation. We assert that workforce differentiation can be adopted (Marescaux et al., Citation2021), alongside a focus on self-improvement at an individual level (Tesser, Citation1988) and supportive workplaces at an organisational level (Kaliannan et al., Citation2023).

In terms of communicating talent designation, we recognise that strategic ambiguity is viewed as a rhetorical asset (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2010), providing firms with some level of flexibility over talent pool inclusion. Moreover, van Zelderen et al. (Citation2024) found that employees identified as talents and non-talents reacted more favourably to exclusive, secretive practices than to inclusive, transparent practices. Thus, while organisations may not end up communicating talent or non-talent designation per se, we suggest that attainability and encouragement of approach motivation are critical components to consider in developmental conversations with employees.

While our conceptual model centres around the relevance and attainability of talent status, we also illustrate a set of contextual factors that may shape the social comparison process (see ). For example, we recognise the critical moderating role that justice plays in social comparisons (Gelens et al., Citation2014), particularly as employees devote more time to justice issues in settings involving uncertainty (i.e. talent/non-talent designation). Justice, defined as ‘the perceived adherence to rules that reflect appropriateness in decision contexts’ (Colquitt & Zipay, Citation2015, p. 76) may impact how individuals react to organisational talent management practices and, specifically, perceived non-talent designation. Thus, how organisations integrate distributive, procedural, informational, and interpersonal justice matters in the context of talent decisions (Gelens et al., Citation2013).

From a distributive justice perspective, perceptions of inequity and equality can strongly impact employee reactions (Swailes & Blackburn, Citation2016), which is increasingly relevant for diversity and inclusion considerations (Daubner-Siva et al., Citation2017; Kaliannan et al., Citation2023). This is particularly the case where allocation of resources is centred around a very small talent-designated percentage of the workforce. From a procedural justice perspective, talent identification is frequently a source of tension (e.g. McDonnell et al., Citation2023; Tyskbo, Citation2021). As there often exists a lack of clarity around the meaning of talent in firms, talent identification appears to be based on subjective judgement, which can differ significantly among organisational stakeholders, impacting perceived effectiveness of talent designation practices (Khoreva et al., Citation2017).

From an informational justice perspective, employee reactions to perceived non-talent designation will arguably depend on how they were informed of the outcome of a talent review (Sumelius et al., Citation2020). Decisions might be communicated formally as part of a performance evaluation process; alternatively, employees might be notified through informal communication with their manager or only hear about decisions through the grapevine. Further, employee reactions will also depend on expectation management prior to talent reviews, in other words, what has been signalled to employees in terms of talent considerations. Discrepancies between individuals’ perception of talent status and the actual status awarded are likely common (Sonnenberg et al., Citation2014) and, therefore, expectation management and informational justice are critical. Finally, from an interpersonal justice perspective, we note that the relationship between a non-talent and the decision communicator as well as the identification with management and the wider organisation may impact social comparisons and employee reactions to perceived non-talent designation (Wikhamn et al., Citation2020).

In addition to perceptions of justice, we acknowledge that there are various other micro-, meso-, and macro-level factors, influencing the social comparison process. At a micro level, we indicate that demographic profiles (e.g. education, seniority, tenure), alongside HR attributions and personality traits (e.g. narcissism; Kanabar & Fletcher, Citation2022), will likely impact whether social comparison is experienced as inspiration or envy. If a co-worker is significantly more senior, a social comparison might not be regarded as a source of self-relevant information at all or potentially result in inspiration rather than envy. In addition, we also acknowledge that various temporal dynamics shape social comparison over time, including temporal markers (i.e. position, velocity, acceleration, mean level, and minimum/maximum position) and factors of uncertainty (i.e. time span, interruptions, and fluctuations) (see Reh et al., Citation2022).

At a meso level, organisational norms and contexts (e.g. organisational culture; talent management philosophy, system, and practices; degree of workforce differentiation; talent status secrecy/transparency) can shape the social comparison experience (De Boeck et al., Citation2018). In this regard, research in real-life contexts, including organisations with different talent management philosophies and programmes (Meyers & van Woerkom, Citation2014) and varying organisational cultures (e.g. collaborative versus competitive), might also reveal more nuanced insights on the impact of talent/non-talent designation on employee reactions. At a macro level, we highlight the potential role of national culture and cross-cultural implications on status dynamics. For example, there might be less status competition in cultures with more rigid social hierarchies or in more collective societies (for a review on status dynamics, see Bendersky & Pai, Citation2018).

4.1. Practical implications

Our research provides several practical implications for organisations. First, employee reactions to talent designation remain a particularly sensitive aspect of talent management and universal reactions should not be assumed. Instead, firms need to recognise that under some conditions, employees are more likely to react positively or negatively to perceived non-talent designation. Our research illustrates that relevance and attainability are two core conditions, shaping the social comparison experience. Thus, key organisational stakeholders involved in making and communicating talent decisions need to gain a solid understanding of these and other contextual factors which positively or negatively shape social comparison experiences in their organisations. Once identified, organisations can take actions to reinforce the conditions that more likely lead to positive employee reactions.

Second, we highlight the value of dynamic talent designation practices in organisations. Firms should explain to individuals that talent designations are made at a particular point in time and that they will revisit talent status on a regular basis during upcoming talent review meetings. This provides employees with reassurance that there is a chance to attain talent status in the future. Organisations should lay out how talent status can be attained, providing transparency around what is valued in the organisation, and more specifically the make-up of the talent construct, including performance criteria and assessment of potential. At an individual level, a focus on attainability recognises the opportunity for self-development and changes in talent status. It provides employees with a setting that allows them to demonstrate performance improvements and show potential over time. At an organisational level, attainability shifts one-to-one conversations from past performance evaluations to future-focused goal setting, development, and employee empowerment, creating more inclusive workplaces. This is critical as individuals with a perceived non-talent designation need encouragement to maintain their well-being and potentially improve their performance (Malik & Singh, Citation2014).

Third, in order to increase approach motivation, organisations ought to gain a better understanding of the dynamics in and priorities of their workforce. Organisations should have open conversations around employees’ career plans to understand the relevance of talent status. This includes insights into whether employees seek economic resources such as development and career opportunities and/or socio-economic resources, i.e. social recognition, esteem, and status (Wikhamn et al., Citation2020). This, in turn, can help firms to determine appropriate development and rewards offerings for individuals. In addition to workforce differentiation for effective talent investments (Koch & Marescaux, Citation2021), organisations should provide inclusive learning opportunities across the organisation. When individuals are encouraged to set learning goals and establish development plans, they are taking actions to potentially achieve talent status. Finally, in order to reduce some of the negative effects of self-serving attributions such as rejecting performance outcomes (Greenberg et al., Citation2007), and thus avoiding performance accountability, organisations should have a transparent approach to their talent review meetings, including the structure, stakeholders involved, and decision-making processes. This transparency further promotes employees’ understanding in terms of inclusion/exclusion in talent pools and ultimately provides a better sense of employees’ attainability of talent status.

4.2. Limitations and future research

Our paper is subject to limitations, which we see as opportunities for future research. As our paper is conceptual in nature, we call for empirical research to test our model of social comparisons upon perceived non-talent designation and our propositions. All key constructs can be readily captured with survey measures: Relevance could be measured with a self-assessment considering low or high relevance of talent status; attainability could be captured by drawing on the perceived goal attainability scale (Pomaki et al., Citation2009); approach motivation could be assessed using Prestin’s (Citation2013) approach motivation scale; and self-serving attributions could be captured drawing on the multidimensional observer attributions for performance (MOAPS) scale (Rudolph et al., Citation2015).

Arguably more important than the choice of empirical measures is the appropriate methodological approach. A survey study would be subject to endogeneity concerns, which is particularly relevant to research on talent status (Krebs & Wehner, Citation2021). A laboratory or vignette experiment would allow for the manipulation of talent status, attainability, and relevance, and for holding potential confounding factors under control of the researcher (van Zelderen et al., Citation2023). We consider individuals who compete for senior technical or managerial roles as the appropriate sampling frame for such research. Access to that population could, for example, be attained through alumni associations of elite MBA programmes.

Alternatively, we see potential in a field study that exploits insider information (Shaw, Citation2009). For example, information on the implementation of a talent management programme in an organisation could be used to identify the relevant population of employees ahead of the implementation of the programme and to set up a panel survey. The first wave (prior to implementation) would ask employees whom they consider as relevant comparison referents for evaluating their own career outcomes and gather data on potential confounds—for example, core self-evaluations (Judge & Hurst, Citation2007) and achievement motives (Lang & Fries, Citation2006) to account for interindividual differences in the approach to deal with challenges and adversity. The second wave (post implementation and the first talent review) would then measure perceptions (i.e. relevance and attainability of talent status) and reactions to social comparisons (i.e. approach motivation and self-serving attributions) of non-talents. However, such a field experiment requires a sufficiently large sample (van Zelderen et al., Citation2023), and the obtained evidence might not be generalisable to other organisational contexts.

Beyond considerations of methodological rigour, we recognise that we focused on approach motivation and self-serving attributions as primary employee reactions. We suggest that employees engage in approach motivation to gain talent status in the future and utilise self-serving attributions to defend non-talent status. While approach motivation and self-serving attributions are important reactions given their relevance in the context of social comparisons and their impact on individuals, teams, and organisations, we acknowledge that a range of other affective, cognitive, or behavioural reactions and outcomes could be considered (De Boeck et al., Citation2018). For example, at an individual level, future studies might examine the impact on commitment, satisfaction, engagement, or well-being. At a team level, the effect of talent and perceived non-talent designation on peer dynamics (Painter-Morland et al., Citation2019) with potential status changes over time (Kehoe et al., Citation2018) merits future research. At a firm level, the impact on organisational culture and performance could be studied (De Boeck et al., Citation2018).

Finally, we did not distinguish between different types of talent, for example, in terms of organisational priorities or scarcity. In this context, status characteristics theory (Correll & Ridgeway, Citation2003) offers great potential to understand our conceptual model in more granular detail by paying closer attention to interindividual ability-related differences. Building on the concept of talent hierarchies, i.e. the differential appreciation of particular types of talents (Nijs et al., Citation2022), non-talents may show approach motivation and self-serving attributions to a greater or lesser extent depending on the socially significant characteristics on which talents differ from non-talents. We propose to examine social comparisons of non-talents with talents across layers of the talent hierarchy to move towards more nuanced insights into how employee reactions to perceived non-talent designation might play out.

Acknowledgment

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Notes

1 In the broader management and psychology literatures, both ‘high performers’ and ‘stars’ are commonly adopted terms. For the purpose of this paper, we refer to these as talents.

References

- Bendersky, C., & Pai, J. (2018). Status dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5(1), 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104602

- Björkman, I., Ehrnrooth, M., Mäkelä, K., Smale, A., & Sumelius, J. (2013). Talent or not? Employee reactions to talent identification. Human Resource Management, 52(2), 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21525

- Bradley, G. W. (1978). Self-serving biases in the attribution process: A reexamination of the fact or fiction question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.1.56

- Boekhorst, J. A., Basir, N., & Malhotra, S. (2024). Star light, but why not so bright? A process model of how incumbents influence star newcomer performance. Academy of Management Review, 49(1), 56–79. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2020.0519

- Boonbumroongsuk, B., & Rungruang, P. (2022). Employee perception of talent management practices and turnover intentions: A multiple mediator model. Employee Relations, 44(2), 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2021-0163

- Brunstein, J. C. (1993). Personal goals and subjective well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(5), 1061–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.5.1061

- Buunk, A. P., & Gibbons, F. X. (2007). Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007

- Call, M. L., Nyberg, A. J., & Thatcher, S. M. B. (2015). Stargazing: An integrative conceptual review, theoretical reconciliation, and extension for star employee research. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(3), 623–640. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039100

- Campbell, E. M., Liao, H., Chuang, A., Zhou, J., & Dong, Y. (2017). Hot shots and cool reception? An expanded view of social consequences for high performers. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(5), 845–866. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000183

- Campbell, W. K., & Sedikides, C. (1999). Self-threat magnifies the self-serving bias: A meta-analytic integration. Review of General Psychology, 3(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.3.1.23

- Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(3), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.3.366

- Church, A. H., Guidry, B. W., Dickey, J. A., & Scrivani, J. A. (2021). Is there potential in assessing for high potential? Evaluating the relationships between performance ratings, leadership assessment data, designated high-potential status and promotion outcomes in a global organization. The Leadership Quarterly, 32(5), 101516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2021.101516

- Collings, D. G., & Mellahi, K. (2009). Strategic talent management: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 19(4), 304–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.04.001

- Collins, R. L. (1996). For better or worse: The impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51

- Colquitt, J. A., & Zipay, K. P. (2015). Justice, fairness, and employee reactions. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2(1), 75–99. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111457

- Correll, S. J., & Ridgeway, C. L. (2003). Expectation states theory. In J. Delamater (Ed.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 29–51). Kluwer Academic Press.

- Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31(6), 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

- Daubner-Siva, D., Vinkenburg, C. J., & Jansen, P. G. W. (2017). Dovetailing talent management and diversity management: The exclusion-inclusion paradox. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 4(4), 315–331. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-02-2017-0019

- Daubner-Siva, D., Ybema, S., Vinkenburg, C. J., & Beech, N. (2018). The talent paradox: Talent management as a mixed blessing. Journal of Organizational Ethnography, 7(1), 74–86. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOE-01-2017-0002

- De Boeck, G., Meyers, M. C., & Dries, N. (2018). Employee reactions to talent management: Assumptions versus evidence. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(2), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2254

- DeNisi, A. S., & Murphy, K. R. (2017). Performance appraisal and performance management: 100 years of progress? The Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(3), 421–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000085

- Dries, N., & Kaše, R. (2023). Do employees find inclusive talent management fairer? It depends. Contrasting self-interest and principle. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(3), 702–727. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12501

- Dries, N., & Pepermans, R. (2012). How to identify leadership potential: Development and testing of a consensus model. Human Resource Management, 51(3), 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21473

- Duffy, M. K., Scott, K. L., Shaw, J. D., Tepper, B. J., & Aquino, K. (2012). A social context model of envy and social undermining. Academy of Management Journal, 55(3), 643–666. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.0804

- Duffy, M. K., Lee, K., & Adair, E. A. (2021). Workplace envy. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 8(1), 19–44. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-055746

- Ehrnrooth, M., Björkman, I., Mäkelä, K., Smale, A., Sumelius, J., & Taimitarha, S. (2018). Talent responses to talent status awareness: Not a question of simple reciprocation. Human Resource Management Journal, 28(3), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12190

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Finkelstein, L., Costanza, D., & Goodwin, G. (2018). Do your high potentials have potential? The impact of individual differences and designation on leader success. Personnel Psychology, 71(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12225

- Gallardo-Gallardo, E., Dries, N., & González-Cruz, T. F. (2013). What is the meaning of ‘talent’ in the world of work? Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 290–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.002

- Gelens, J., Dries, N., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2015). Affective commitment of employees designated as talent: Signalling perceived organisational support. European Journla of International Management, 9(1), 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2015.066669

- Gelens, J., Dries, N., Hofmans, J., & Pepermans, R. (2013). The role of perceived organizational justice in shaping the outcomes of talent management: A research agenda. Human Resource Management Review, 23(4), 341–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.05.005

- Gelens, J., Hofmans, J., Dries, N., & Pepermans, R. (2014). Talent management and organisational justice: Employee reactions to high potential identification. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(2), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12029

- Gerber, J. P., Wheeler, L., & Suls, J. (2018). A social comparison theory meta-analysis 60+ years on. Psychological Bulletin, 144(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000127

- Greenberg, J., Ashton-James, C. E., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2007). Social comparison processes in organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.006

- Hamilton, O. S., & Lordan, G. (2022). Ability or luck: A systematic review of interpersonal attributions of success. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1035012. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1035012

- Harmon-Jones, E., Harmon-Jones, C., & Price, T. F. (2013). What is approach motivation? Emotion Review, 5(3), 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073913477509

- Hendricks, J. L., Call, M. L., & Campbell, E. M. (2023). High performer peer effects: A review, synthesis, and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 49(6), 1997–2029. https://doi.org/10.1177/01492063221138225

- Hestermann, N., & Le Yaouanq, Y. (2021). Experimentation with self-serving attribution biases. American Economic Journal: Microeconomics, 13(3), 198–237. https://doi.org/10.1257/mic.20180326

- Jarzabkowski, P., Sillince, J. A., & Shaw, D. (2010). Strategic ambiguity as a rhetorical resource for enabling multiple interests. Human Relations, 63(2), 219–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709337040

- Jooss, S., Collings, D. G., McMackin, J., & Dickmann, M. (2024). A skills-matching perspective on talent management: Developing strategic agility. Human Resource Management, 63(1), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22192

- Jooss, S., McDonnell, A., & Burbach, R. (2021a). Talent designation in practice: An equation of high potential, performance and mobility. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(21), 4551–4577. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1686651

- Jooss, S., Burbach, R., & Ruël, H. (2021b). Examining talent pools as a core talent management practice in multinational corporations. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(11), 2321–2352. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1579748

- Judge, T. A., & Hurst, C. (2007). Capitalizing on one’s advantages: Role of core self-evaluations. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1212–1227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1212

- Kaliannan, M., Darmalinggam, D., Dorasamy, M., & Abraham, M. (2023). Inclusive talent development as a key talent management approach: A systematic literature review. Human Resource Management Review, 33(1), 100926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2022.100926

- Kamoche, K., & Leigh, F. S. (2022). Talent management, identity construction and the burden of elitism: The case of management trainees in Hong Kong. Human Relations, 75(5), 817–841. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726721996778

- Kanabar, J., & Fletcher, L. (2022). When does being in a talent pool reap benefits? The moderating role of narcissism. Human Resource Development International, 25(4), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2020.1840846

- Kehoe, R. R., Call, M. L., & Bentley, F. S. (2022). Shining a light on star scholarship: Progress and prospects. In D. G. Collings, V. Vaiman, & H. Scullion (Eds.), Talent management: A decade of developments (pp. 85–106). Emerald.

- Kehoe, R. R., Lepak, D. P., & Bentley, F. S. (2018). Let’s call a star a star: Task performance, external status, and exceptional contributors in organizations. Journal of Management, 44(5), 1848–1872. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316628644

- Khoreva, V., Vaiman, V., & Van Zalk, M. (2017). Talent management practice effectiveness: Investigating employee perspective. Employee Relations, 39(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-01-2016-0005

- Kim, E., & Glomb, T. M. (2014). Victimization of high performers: The roles of envy and work group identification. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 619–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035789

- King, K. A. (2016). The talent deal and journey: Understanding the employee response to talent identification over time. Employee Relations, 38(1), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2015-0155

- Koch, M., & Marescaux, E. (2021). Talent management and workforce differentiation. In I. Tarique (Ed.), The Routledge companion to talent management (pp. 372–383). Routledge.

- Krebs, B., & Wehner, M. (2021). The relationship between talent management and individual and organizational performance. In I. Tarique (Ed.), The Routledge companion to talent management., (pp. 539–555) Routledge.

- Kirk, S. (2021). Sticks and stones: The naming of global talent. Work, Employment and Society, 35(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017020922337

- Lang, J. W. B., & Fries, S. (2006). A revised 10-item version of the achievement motives scale: Psychometric properties in German-speaking samples. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 22(3), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.22.3.216

- Lang, P. J., & Bradley, M. M. (2008). Appetitive and defensive motivation is the substrate of emotion. In A. Elliott (Ed.), Handbook of approach and avoidance motivation (pp. 51–66). Psychology Press.

- Lockwood, P., & Kunda, Z. (1997). Superstars and me: Predicting the impact of role models on the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(1), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.91

- Mäkelä, K., Björkman, I., & Ehrnrooth, M. (2010). How do MNCs establish their talent pools? Influences on individuals’ likelihood of being labeled as talent. Journal of World Business, 45(2), 134–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2009.09.020

- Malik, A. R., & Singh, P. (2014). ‘High potential’ programs: Let’s hear it for ‘B’players. Human Resource Management Review, 24(4), 330–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2014.06.001

- Marescaux, E., De Winne, S., & Brebels, L. (2021). Putting the pieces together: A review of HR differentiation literature and a multilevel model. Journal of Management, 47(6), 1564–1595. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320987286

- Marescaux, E., De Winne, S., & Rofcanin, Y. (2019). Co-worker reactions to i-deals through the lens of social comparison: The role of fairness and emotions. Human Relations, 74(3), 329–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267198841

- McDonnell, A., Collings, D. G., Mellahi, K., & Schuler, R. S. (2017). Talent management: A systematic review and future prospects. European J. of International Management, 11(1), 86–128. https://doi.org/10.1504/EJIM.2017.081253

- McDonnell, A., Skuza, A., Jooss, S., & Scullion, H. (2023). Tensions in talent identification: A multi-stakeholder perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(6), 1132–1156. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1976245

- Meyers, M. C. (2020). The neglected role of talent proactivity: Integrating proactive behavior into talent-management theorizing. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100703

- Meyers, M. C., van Woerkom, M., Paauwe, J., & Dries, N. (2020). HR managers’ talent philosophies: Prevalence and relationships with perceived talent management practices. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(4), 562–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1579747

- Meyers, M. C., & van Woerkom, M. (2014). The influence of underlying philosophies on talent management: Theory, implications for practice, and research agenda. Journal of World Business, 49(2), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.11.003

- Nijs, S., Dries, N., Van Vlasselaer, V., & Sels, L. (2022). Reframing talent identification as a status-organising process: Examining talent hierarchies through data mining. Human Resource Management Journal, 32(1), 169–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12401

- Painter-Morland, M., Kirk, S., Deslandes, G., & Tansley, C. (2019). Talent management: The good, the bad, and the possible. European Management Review, 16(1), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12171

- Petriglieri, J. L. (2011). Under threat: Responses to and the consequences of threats to individuals’ identities. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 641–662. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0087

- Petriglieri, J. L., & Petriglieri, G. (2017). The talent curse. Why high-potentials struggle and how they can grow through it. Harvard Business Review, 95(3), 89–94.

- Pomaki, G., Karoly, P., & Maes, S. (2009). Linking goal progress to subjective well-being at work: The moderating role of goal-related self-efficacy and attainability. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 14(2), 206–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014605

- Prestin, A. (2013). The pursuit of hopefulness: Operationalizing hope in entertainment media narratives. Media Psychology, 16(3), 318–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2013.773494

- Reh, S., Van Quaquebeke, N., Tröster, C., & Giessner, S. R. (2022). When and why does status threat at work bring out the best and the worst in us? A temporal social comparison theory. Organizational Psychology Review, 12(3), 241–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/204138662211002

- Rudolph, C. W., Harari, M. B., & Nieminen, L. R. (2015). The effect of performance trend on performance ratings occurs through observer attributions, but depends on performance variability. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 45(10), 541–560. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12318

- Scheff, T. J. (2018). Looking glass selves: The Cooley-Goffman conjecture. In N. Ruiz-Junco, & B. Brossard (Eds.), Updating Charles H. Cooley (pp. 111–125). Routledge.

- Schmidt, J. A., Pohler, D., & Willness, C. R. (2018). Strategic HR system differentiation between jobs: The effects on firm performance and employee outcomes. Human Resource Management, 57(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21836

- Scholer, A. A., Cornwell, J. F., & Higgins, E. T. (2019). Should we approach approach and avoid avoidance? An inquiry from different levels. Psychological Inquiry, 30(3), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2019.1643667

- Shaw, K. (2009). Insider econometrics: A roadmap with stops along the way. Labour Economics, 16(6), 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2009.09.001

- Sonnenberg, M., van Zijderveld, V., & Brinks, M. (2014). The role of talent-perception incongruence in effective talent management. Journal of World Business, 49(2), 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.11.011

- Silzer, R., & Church, A. H. (2009). The pearls and perils of identifying potential. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 2(4), 377–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2009.01163.x

- Suls, J., & Wheeler, L. (2013). Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research. Springer.

- Sumelius, J., Smale, A., & Yamao, S. (2020). Mixed signals: Employee reactions to talent status communication amidst strategic ambiguity. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(4), 511–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1500388

- Swailes, S. (2013). The ethics of talent management. Business Ethics: A European Review, 22(1), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12007

- Swailes, S., & Blackburn, M. (2016). Employee reactions to talent pool membership. Employee Relations, 38(1), 112–128. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-02-2015-0030

- Swailes, S. (2020). Responsible talent management: Towards guiding principles. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 7(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-04-2020-0068

- Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P., & Flament, C. (1971). Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. European Journal of Social Psychology, 1(2), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2420010202

- Tansley, C., & Tietze, S. (2013). Rites of passage through talent management progression stages: An identity work perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(9), 1799–1815. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.777542

- Tesser, A. (1988). Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 21, 181–227.

- Thrash, T. M., & Elliot, A. J. (2004). Inspiration: Core characteristics, component processes, antecedents, and function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(6), 957–973. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.957

- Troth, A. C., & Guest, D. E. (2020). The case for psychology in human resource management research. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(1), 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12237

- Tyskbo, D. (2021). Competing institutional logics in talent management: Talent identification at the HQ and a subsidiary. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(10), 2150–2184. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1579248

- Tyskbo, D., & Wikhamn, W. (2023). Talent designation as a mixed blessing: Short- and long-term employee reactions to talent status. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(3), 683–701. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12485

- Vaiman, V., Scullion, H., & Collings, D. G. (2012). Talent management decision making. Management Decision, 50(5), 925–941. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211227663

- van Zelderen, A. P. A., Dries, N., & Marescaux, E. (2023). Talents under threat: The anticipation of being ostracized by non-talents drives talent turnover. Group & Organization Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/10596011231211639

- van Zelderen, A. P. A., Dries, N., & Marescaux, E. (2024). The paradox of inclusion in elite workforce differentiation practices: Harnessing the genius effect. Journal of Management Studies. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.13084

- Vardi, S., & Collings, D. G. (2023). What’s in a name? Talent: A review and research agenda. Human Resource Management Journal, 33(3), 660–682. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12500

- Watkins, T. (2021). Workplace interpersonal capitalization: Employee reactions to coworker positive event disclosures. Academy of Management Journal, 64(2), 537–561. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.1339

- Wikhamn, W., Asplund, K., & Dries, N. (2020). Identification with management and the organisation as key mechanisms in explaining employee reactions to talent status. Human Resource Management Journal, 31(4), 956–976. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12335

- Zesik, B. (2019). The rhetoric, politics and reality of talent management: Insider perspectives. In S. Swailes (Ed.), Managing talent: A critical appreciation (pp. 51–69). Emerald.

- Zhou, J., Zhan, Y., Cheng, H., & Zhang, G. (2023). Challenge or threat? Exploring the dual effects of temporal social comparison on employee workplace coping behaviors. Current Psychology, 42(21), 18300–18316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-02999-y