Abstract

This study investigated the effects of synchronous computer-mediated communication (SCMC) mode and interlocutor familiarity on frequency and characteristics of peer feedback in L2 interaction. Fifty dyads of EFL learners were equally assigned into familiar (+/–) groups and performed an interactive task in two SCMC modes (text/video-chats). After their interactions, they were interviewed individually about the impact of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity on the provision of feedback. Learners’ text/video-chats were coded for feedback frequency and characteristics (e.g. type, linguistic focus, accuracy, and modified output). Results show that more instances of feedback were observed in the video- than text-chats; however, interlocutor familiarity did not affect the amount of feedback. Despite differences in types, feedback’s linguistic focus and accuracy, frequency and characteristics of modified output were relatively similar between two SCMC modes. Content-based analyses of the interviews revealed that learners attributed the differences in feedback occurrence to various characteristics of the SCMC modes rather than interlocutor unfamiliarity. The results suggest greater benefits of the video-chat over the text-chat in promoting peer feedback and emphasise the importance of establishing a positive relationship among learners during L2 SCMC interaction.

Introduction

Peer feedback in (L2) task-based interaction, defined as a learner’s response to peer’s language issues (Iwashita & Dao, Citation2021; Philp, Adams, & Iwashita, Citation2014), has received much attention from both L2 instructors and researchers. Recent research has shown both benefits (e.g. facilitating L2 production accuracy) and challenges of this feedback type (e.g. low frequency and accuracy) for L2 learning (Iwashita & Dao, Citation2021; Philp et al., Citation2014; Sato & Ballinger, Citation2016). However, this body of research has largely explored peer feedback in face-to-face (FTF) interaction, with little examining it directly in relation to the affordances of synchronous computer-mediated communication (SCMC), a real time interaction between L2 learners via the use of a computer (Bueno-Alastuey, Citation2013; Cárdenas-Claros, 2020; Yanguas, Citation2010). With the development of technology, the use of SCMC in L2 learning and teaching has increased significantly and become relatively ubiquitous, especially in distance L2 learning courses and in the EFL context where the current study was conducted. Despite its prevalence in the context of the current study, little research has examined the impact of the use of SCMC on learners’ interaction and L2 learning, especially regarding whether and/or how the learners provide feedback to each other during this synchronous online chat. In addition, because peer feedback is considered facilitative and central to language development (Gass & Mackey, Citation2015), it is important to investigate how SCMC (i.e. text/video-chat) affects its occurrence and characteristics.

Investigating peer feedback in text/video-chat will also address a gap in the existing research which has largely compared the impact of SCMC mode (e.g. audio/video-chats, and text/audio/multimodal chats) on learners’ negotiation for meaning, and language related-episodes/LREs (i.e. learners’ discussion of language form) (Baralt, Gurzynski-Weiss, & Kim, Citation2016; Yanguas, Citation2010, Citation2012; Yanguas & Bergin, Citation2018; Ziegler & Phung, Citation2019), but paid little attention to peer feedback. Given that text-chat and video-chat, two major modes of SCMC, differ in many aspects such as absence/presence of visual cues, nature of discourse (texting versus speaking), turn-taking, immediacy of response (instant versus delayed), and communication pressure (Ortega, Citation1997, Citation2009), it is likely that the differences in these characteristics might either increase or decrease peer feedback’s frequency and that peer feedback’s characteristics might vary in these modes. Additionally, as compared to text-chat, video-chat has been under-researched and just recently received more attention due to technological development (Hung & Higgins, Citation2016; Jung et al., Citation2019; Lenkaitis, Citation2020; Shih, Citation2014; Wigham & Chanier, Citation2015; Yanguas, Citation2012). Thus, it is necessary to investigate the affordances offered by this newly developed mode for L2 learning with regard to peer feedback.

Apart from the mode of communication, peer feedback may also be influenced by several social factors, among which, learners’ unfamiliarity with each other has been reported to be an important aspect. Since SCMC (i.e. text/video-chat) may limit the depth, elaboration, and sophistication of conversations, and may diminish ‘social presence’ or ‘a sense of being together’ (Shih, Citation2014), it is possible that these negative impacts of SCMC on peer feedback may be stronger when learners are not familiar with each other. Previous research has documented that unfamiliarity with partners during FTF interaction reduced learners’ discussion of language form or LREs which includes peer feedback (Pastushenkov et al., 2020; Poteau, Citation2011). However, little research has documented whether these negative impacts of interlocutor unfamiliarity on peer feedback exist in text/video-chat and, if so, whether they vary between text/video-chat.

To fill in these gaps, the current study investigated peer feedback in SCMC, specifically focusing on its occurrence and characteristics (e.g. type, linguistic focus, accuracy and modified output) in text- and video-chat using Facebook Messenger, a popular videoconferencing tool. Additionally, given the mixed findings about learners’ perceptions (both negatively and/or positively) of varied SCMC modes, including text/video-chat (Bueno-Alastuey, Citation2010, Citation2011; Chen & Yang, Citation2014; Jauregi, Canto, de Graaff, Koenraad, & Moonen, Citation2011; Kozar, Citation2016; Ziegler & Phung, Citation2019), the current study also examined learners’ interview responses using a content-based approach to gain more insights into their perceptions of the text/video-chat experiences and interlocutor familiarity.

Theoretical accounts for the role of peer feedback in L2 learning

The benefits of peer feedback for L2 learning have been explained from multiple perspectives. Within the cognitive-interactionist perspective, peer feedback provides learners with opportunities to attend to language form, receive comprehensible input, and modify language output, all considered central to L2 learning (Gass & Mackey, Citation2015). Following the skill acquisition theory, peer feedback is perceived as a meaningful language practice that could result in learners’ restructuring of their declarative linguistic knowledge (DeKeyser, Citation2007) and improvement in language production accuracy and fluency (Sato & Lyster, Citation2012). Viewed from the sociocultural perspective, peer feedback is a dialogic scaffolding strategy that assists learners in performing tasks that they could not do individually and enables them to co-construct language knowledge (see Dao & Iwashita, Citation2018; Nassaji & Swain, Citation2000; van Compernolle, Citation2015). Guided by these theoretical perspectives, much L2 research has evidenced the facilitative role of peer feedback during FTF interaction in L2 learning (see Iwashita & Dao, Citation2021; Lyster, Saito, & Sato, Citation2013; Nassaji & Kartchava, Citation2017 for reviews). Recently, research has expanded to examine peer feedback in SCMC, which reflects a growing interest in the benefits of SCMC for L2 learning (Chapelle, Citation2001; González-Lloret & Ortega, 2014; Plonsky & Ziegler, Citation2016; Ziegler, Citation2016). The next section presents a review of research trends that investigated oral peer feedback in SCMC.

Oral peer feedback in SCMC

To date, there appears to be three strands of research that investigate oral peer feedback in SCMC. The first strand of SCMC research targets at the nature of feedback (provided by either learners and/or the teacher, and native speaker feedback) and its impacts on L2 learning (e.g. Arroyo & Yilmaz, Citation2018; Bower & Kawaguchi, Citation2011; Bryfonski & Ma, Citation2020; Lee, Citation2006; Loewen & Erlam, Citation2006; Sanz, Citation2004; Sanz & Morgan-Short, Citation2004; Sauro, Citation2009; Sotillo, Citation2005, Citation2009). The second strand of recent SCMC research compares peer feedback frequency between SCMC and FTF interaction (e.g. Baralt, Citation2013, Citation2014; Baralt et al., Citation2016; Gurzynski-Weiss & Baralt, Citation2014; Iwasaki & Oliver, Citation2003; Lai & Zhao, Citation2006). Despite providing some insights, the studies in these two strands have been largely restrained to feedback which is (1) deliberately manipulated along its explicitness, (2) provided by either native speakers or advanced/confederate learners, and/or (3) often examined as part of LREs or negotiation for meaning. Therefore, it is yet known as to whether and the degree to which learners naturally provide each other with peer feedback in SCMC (e.g. text/video-chat). In addition, existing studies have often focussed on one mode of SCMC and/or compared it (e.g. text-chat) to FTF mode. Thus, little is known as to whether and/or how modes of SCMC (e.g. text-chat versus video chat) differ with regard to their impact on learners’ provision of peer feedback. Furthermore, the results of existing research were mixed and generally showed different impact of SCMC modes on feedback, including peer feedback. These mixed results could be ascribed to social and contextual factors such as learners’ familiarity with each other in SCMC, which is part of the focus of the current study.

The third and recently growing line of research has focussed directly on comparing different SCMC modes (e.g. text, audio, video and multimodal) on peer feedback due to new technological features added to SCMC. For instance, Wigham and Chanier (Citation2015) reported that both text/audio-chats were used for different purposes, with text-chat used by learners as a platform to provide feedback (i.e. recasts) on lexical errors that predominantly occurred in audio-chat. To tease out the impact of different modes of SCMC, Ziegler and Phung (Citation2019) had a confederate interlocutor (advanced L2 speakers) interact with L2 learners in four modes (i.e. audio-, video-, text- and multimodal chats) to explore different features of interaction, including feedback. The results showed the largest proportion of feedback in the multimodal chat mode, indicating the potential of this mode over others for facilitating L2 learning opportunities. In sum, despite shedding some light on peer feedback use in text/video-chat, Wigham and Chanier’s study did not tease out the impact of text/video-chat on peer feedback provision. Also, feedback in Ziegler and Phung (Citation2019) study was provided by a confederate interlocutor who was asked to deliberately provide a certain type of feedback rather than the learners. Therefore, little is known about how frequent feedback is provided by learners themselves in different SCMC modes (e.g. text-chat versus video-chat).

In addition, although a growing number of SCMC studies have explored peer feedback, to the best of our knowledge, no research so far has investigated the accuracy of peer feedback in text/video-chat and whether or to what extent learners modify their output following peer feedback in these synchronous online chats. With regard to its accuracy, previous research has reported that peer feedback in FTF interaction is at times inaccurate (Iwashita & Dao, Citation2021; Leeser, 2004) and not reliable and thus less trusted by their peer partners (Katayama, Citation2007; Yoshida, Citation2021). However, it is unclear as to which extent concerns about peer feedback quality exist in SCMC and whether types of peer feedback differ between modes of text/video-chat.

Another aspect of consideration is modified output, or reformulation of an utterance following feedback, which is perceived as evidence for learner’s uptake and possible restructuring of their L2 knowledge, which implicates subsequent L2 learning (Mackey, Citation2012; Swain, Citation2005). Previous research has evidenced that modified output following peer feedback has positive impact on L2 learning (Egi, Citation2010; Loewen & Wolff, Citation2016; McDonough, Citation2005). However, the extent to which modified output occurs in SCMC and whether it differs between text- and video-chat is little known. Salomonsson’s study (2002) is one among very few studies investigating learners’ modified output in oral SCMC using Adobe Connect. The results show that modified output rarely occurred following the signal or initiation of errors by peers. In addition, learners never modified their output even though their peers corrected their errors. Despite providing some informative insights, an interesting question that arises is whether low frequency of modified output is the case for both text- and video-chat, and to what extent modified output following peer feedback is accurate. This therefore warrants further research into the occurrence and accuracy of modified output in SCMC.

Interlocutor familiarity in L2 interaction

As mentioned above, SCMC studies reported mixed findings about the impact of SCMC mode on different features of interaction (e.g. LREs and negotiation of meaning, and peer feedback). The mixed results could be due to whether the learners are familiar with each other. Previous research shows that in the context of L2 FTF interaction, learners’ familiarity with each other affected their communication. For instance, in comparison with unfamiliar dyads, dyads of familiar learners attended more to language features in their interaction (Pastushenkov et al., 2020), and increased their language use and grammatical accuracy (O’Sullivan, Citation2002) and comprehensibility (Gass & Varonis, Citation1984). Familiar dyads were also found to be more willing to negotiate for meaning, express non-understanding, and complete each other’s utterances; therefore, it is suggested that familiarity enables learners to perceive their interaction as less threatening and smooths the flow of the conversation even with interruptions (Plough & Gass, Citation1993).

Interlocutor unfamiliarity, however, appeared to negatively affect learners’ interaction. For instance, interlocutor unfamiliarity was reported to result in more transfer errors and greater use of the first language (Cholewka, Citation1997), less negotiation for meaning and little engagement in discussing language issues (Pastushenkov et al., 2020). Additionally, learners reported feeling less comfortable when interacting with strangers than friends (Cao & Philp, Citation2006), which creates an unfavourable context for practicing language use. Groups of unfamiliar learners also had lower retention of vocabulary, produced fewer quantities of texts, engaged less in activities, and found group work problematic (Poteau, Citation2011).

Overall, existing studies indicate that interlocutor (un)familiarity negatively affects how learners interact in L2 FTF interaction. However, whether interlocutor (un)familiarity affects learners’ provision of peer feedback in text/video-chats has been underexplored. Since peer feedback is considered as a face-threatening act which is vulnerable to social and affective factors (e.g. interlocutor familiarity), it is possible that learners’ unfamiliarity might decrease their provision of peer feedback, especially in SCMC mode (e.g. text/video-chat). In addition, given the physical distance in SCMC and the differences in the nature between text- and video-chat, it is likely that partner unfamiliarity could be a source of misunderstanding and formation of negative interactional relationship, which therefore affects peer feedback frequency and characteristics.

The current study

To summarise, despite an increased use of SCMC in the participants’ L2 learning context, little research has compared whether SCMC mode (text- versus video-chat) has differential impacts on the occurrence and characteristics of peer feedback, a feature of interaction crucial to L2 learning. Additionally, studies have documented the positive impact of pairing learners with familiar as opposed to unfamiliar peers on their FTF interaction. However, whether interlocutor familiarity exerts similar impacts when learners perform tasks in text/video-chats has been understudied. Furthermore, previous research reported learners’ mixed perceptions of different SCMC modes and revealed little insight into learners’ perceptions of the impact of interlocutor familiarity on text/video-chats. To fill in these gaps, the present study investigated the impact of SCMC mode (text- versus video-chat) and interlocutor familiarity on the frequency and characteristics of peer feedback.

Research questions

To what extent do SCMC mode (text- versus video-chats) and interlocutor familiarity affect the amount and characteristics of peer feedback in L2 interaction?

How do learners perceive the impact of characteristics of text/video-chats and interlocutor familiarity on their provision of peer feedback in L2 interaction?

Method

Participants

Participants were 100 EFL learners (61 females, 39 males) recruited from five English classes at two private language centres in two cities in the South of Vietnam. The participants’ ages ranged from 15 to 33 years old (M = 18.93, SD = 2.63). They reported to have studied English for a mean of 9.67 years (SD = 2.49). They were equally assigned into familiar (+/–) groups (see the study design), with their mean proficiency assessed by a TOEICFootnote1 test, delivered a day prior to their interaction, being 432.10 (SD = 139.20) and 423.60 (SD =150.18), respectively. An independent t-test showed no significant differences in proficiency level between two groups, t(98) = .29, p = .77, d = .06, indicating both groups’ similar proficiency level.

Design

The study adopted a mixed design to investigate the impact of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity on the occurrence and characteristics of peer feedback in L2 interaction. Independent variables included SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity. SCMC mode was operationalised as having two conditions: text-chat and video-chat. Although interlocutor familiarity could arguably be a colloquial construct representing several sub-variables, following Pastushenkov et al.’s (2020), it was defined in the present study following three criteria: 1) being a close friend/classmate, 2) having previous experiences of working together in pairs/groups or 3) never knowing and meeting prior to the interaction. Thus, interlocutor familiarity was operationalised as having two conditions: dyads in which learners are friends/classmates and used to work together in pair/group work (+familiar group), versus dyads in which learners did not know each other and had not worked together before (–familiar group). As reported in the participant section, familiar (+/–) groups were comparable in terms of their proficiency level. To control for proficiency-pairing difference within each group, learners were randomly paired within groups, with each group across all conditions consisting of both similar and mixed-proficiency pairs. The dependent variable was peer feedback, operationalised as all response information provided by a learner about their peers’ actual stage of language use and/or communication issues.

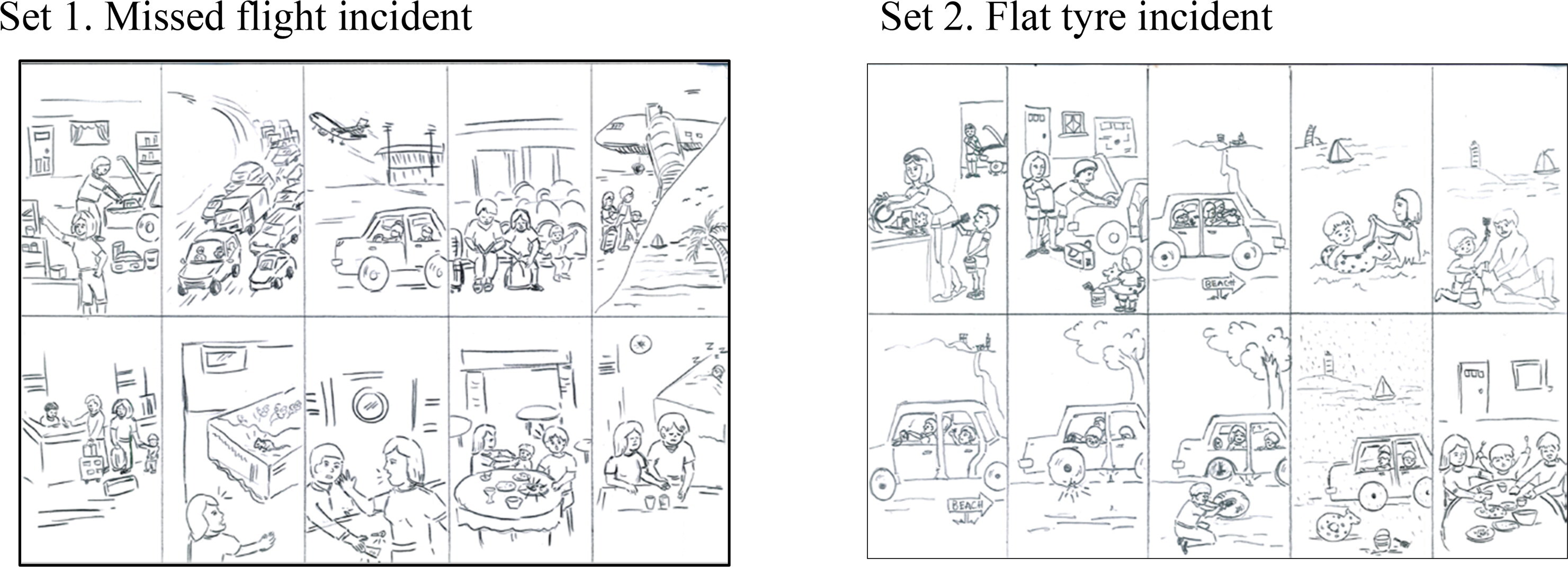

Materials

Materials included two similar versions of a communicative picture-sequencing task which asks dyads to discuss 10 pictures (each learner was randomly given five pictures) without showing each other their pictures and construct a meaningful story in writing. To control for possible impact of task topic and content, both task versions had a similar topic (i.e. vacation incidents) and featured similar activities in the same sequence, such as trip preparation, activities during the trip, occurrence of the incident, and returning home.

The materials also consisted of a questionnaire and an individual semi-structured post-task interview. The first part of the questionnaire concerned learners’ demographic information while the second part consisted of five open-ended questions used to assess learners’ familiarity and assign them into the familiar (+/–) groups. The individual interview elicited learners’ perceptions of the impact of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity on peer feedback provision (see Appendix for the questionnaire and interview prompts).

SCMC tools

Facebook Messenger was used to create SCMC modes (text- and video-chat). Given the popularity of Facebook Messenger in the participants’ context, it appears to be one of the SCMC platforms that participants might have had experience of using it every day. An online Google Docs form was used as a tool for the participants to co-construct their written texts. A brief training session prior to interaction was provided to help the participants become familiar with Facebook Messenger and the Google Docs form.

Procedure

After getting the teachers’ permission, the researcher (the first author) visited each class and introduced the research project. The learners who volunteered to join the project then contacted the researcher via email. Data were collected over a four-month period in a lab-based setting at a private language centre during a 120-minute session scheduled according to the participants’ availability. The learners were then given a consent form and a background information questionnaire to complete (see Appendix). Forty-eight learners (24 dyads) indicated their familiarity with partners by selecting 10 on the 10-point Likert scale (1 = not familiar, 10= very familiar). Two learners (one dyad) selected 9 on the familiarity Likert scale. These learners were assigned into the familiar (+) group. Fifty learners (25 dyads) who selected 0 on the 10-point Likert scale were assigned into the familiar (-) group. Once paired up and double-checked for the level of familiarity (30 minutes), each learner was seated in a separate room and received task instruction as well as time to practice using Facebook Messenger and Google Docs (20 minutes). After that, each dyad performed the first version of the task in the text-chat by using the Facebook Messenger text-chat function (30 minutes), and then the second version of the task in the video-chat by using the Facebook Messenger video call (30 minutes), with a 10-minute break between two tasks. To control for practice effect, SCMC mode and task versions were counterbalanced. Half of the dyads performed the tasks in the text-chat and then video-chat while the other half did the other way around. Two sets of task pictures were also counterbalanced across the familiarity conditions and SCMC modes. Each text-/video-based interaction was recorded using a portable digital recorder, a screen recorder software and an external portable camera. An informal 20-minute interview with each participant in Vietnamese (the learners’ L1) was carried out in a separate room after they completed the two tasks. For research ethics, the researchers followed the UK data protection regulations where the research ethics approval was granted, and the data were de-identified and reported with anonymity to protect the participant’s identities as specified in the participants’ consent.

Coding

Learners’ text-chats were copied and pasted into a word file, and the video-chats were transcribed by a research assistant and verified by the second author. Peer feedback was identified and coded for type, linguistic focus, accuracy, and modified output. Following previous frameworks of corrective feedback (Ranta & Lyster, Citation2007; Sheen & Ellis, Citation2011), five categories of peer feedback were identified: recast (i.e. a partial or complete reformulation of a learner’s erroneous utterance), explicit correction (i.e. provision of the correct form of a learner’s erroneous utterance with a clear indication of an error), repetition (i.e. a verbatim repetition of a learner’s erroneous utterance with a stress or a change in intonation to emphasise the error), clarification request (i.e. phrases such as ‘sorry?’, ‘what?’, ‘I don’t understand’ or ‘Pardon’ following a learner’s erroneous utterance to signal an error), and metalinguistic comment (i.e. comments related to the well-formedness of a learner’s erroneous utterance without providing the correct form). Following Iwashita and Dao’s (Citation2021) analytical framework of peer feedback in L2 interaction, peer feedback was also coded for linguistics foci: lexical, grammatical and multiple-linguistic focussed (i.e. more than one linguistic aspect addressed in feedback). Peer feedback was also examined regarding whether it was followed by modified output which was then coded with regard to accuracy (i.e. accurate versus inaccurate). Examples of feedback types, linguistic foci, and (in)accurate output are provided in Examples 1 to 8.

Feedback type

Five feedback types (e.g. recast, explicit correction, repetition, clarification request, metalinguistic comment) are provided in Examples 1 to 5.

Example 1 Recast, accurate feedback, grammar-focussed, accurate modified output (video-chat)

In Example 1, after Learner P2 missed an article in an utterance ‘they go to beach’ (line 1), Learner P1 reformulated it to ‘the beach’ (line 2), which was then acknowledged ‘yes’ and repeated by Learner P2 (line 3).

Example 2 Explicit correction, accurate feedback, grammar-focussed, no modified output (video-chat)

In Example 2, after Learner P1 produced a correct utterance ‘the wife was threatened’ (line 1), Learner P2 uttered ‘threat’ as a suggestion (line 2). However, Learner P1 corrected it as ‘threatened’, reiterated ‘the wife was threatened’ and explicitly indicated Learner P2’s simple past tense verb error ‘ed…ed…threatened’ (line 3).

Example 3 Repetition, accurate feedback, lexis-focussed, accurate modified output (text-chat)

In Example 3, Learner P1’s text message ‘we teeling the story’ (line 1) was not understood by Learner 2 who then questioned by repeating the word ‘teeling’ to indicate the trouble source (line 2). This led Learner 1 to correct the form ‘telling’ (line 3) which was later repeated by Learner P2 to show her understanding ‘ah we telling the story’ though the utterance had a subject/verb agreement issue (line 4).

Example 4 Clarification request, accurate feedback, accurate modified output (text-chat)

In Example 4, after Learner P1 said ‘stress’ (line 1), Learner P2 asked for a clarification ‘stress????’ (line 2) and ‘u[you] get stressed’ (line 3) and expressed an exclamation ‘man’ (line 4). Learner P1 provided a correction ‘street’ (line 7) to clarify his sentence ‘the tire is broken by a nail on the street’ (line 1).

Example 5 Metalinguistic comment, accurate feedback, grammar-focussed, no modified output (video-chat)

In Example 5, Learner P2 corrected Learner P1’s error ‘they have’ (line 1) as ‘they had’ and uttered a metalinguistic comment ‘you need to use the word past simple ‘had’ a traffic jam traffic jam…right for telling story…’ (line 2) to explain his correction.

Linguistic focus

Peer feedback on lexical aspects is shown in Examples 3 and 4, which focus on two lexical items: ‘telling’ and ‘street’, respectively. Peer feedback on grammatical aspects is illustrated in Examples 1, 2 and 5 which concern three grammatical issues: the use of article ‘the’, passive voice ‘the wife was threatened’ and simple past tense verbs ‘they had’. Example 6 exemplifies peer feedback that addresses multiple linguistic issues.

Example 6 Recast, accurate feedback, focus on multiple linguistic aspects, no modified output (text-chat)

In Example 6, Learner P1’s text message is an incomplete sentence ‘and have a warn dinner’ (line 1) which does not have a subject and contains a grammatical error ‘have’ and a spelling/lexical error ‘warn’. In line 3, Learner P2 corrected all of these language issues in one sentence in which he added a subject ‘they’, changed the tense and the verb choice of the sentence from ‘have’ to ‘got’, and corrected the spelling error from ‘warn’ to ‘warm’.

Feedback accuracy

Peer feedback’s accuracy was coded for two categories: accurate and inaccurate. Examples 1 to 6 represent accurate peer feedback. Inaccurate peer feedback is shown in Example 7.

Example 7 Explicit correction, inaccurate feedback, lexical focussed, inaccurate modified output (video-chat)

In Example 7, after Learner P1 stated ‘they get stuck’ (line 1), Learner P2 commented ‘no no no’ (line 2) to signal that something was wrong. This led Learner P1 to check whether the use of ‘stuck’ was appropriate (line 3). Learner P2 then suggested using ‘meet [traffic]’, which was agreed by Learner P1 who then incorporated it into the utterance ‘they meet traffic’. Example 7 shows that Learner P2 provided inaccurate peer feedback on a non-erroneous utterance ‘they get stuck’, which was, however, accepted and used by Learner P1.

Accuracy of modified output

Examples 2, 5 and 6 show that peer feedback was not followed by modified output. Meanwhile, in Examples 1, 3, 4 and 7, modified output occurred following peer feedback. All modified outputs in Examples 1, 3 and 4 were accurate but modified output in Example 7 was inaccurate.

For inter-rater reliability, the second author coded independently the whole dataset and the first author coded 20% of the data. Pearson r for the frequency of peer feedback between two coders was .93. Cohen’s kappa was used to assess reliability of classifying feedback by type (k = .94), feedback’s accuracy (k = .85), linguistic focus (k = .95), feedback followed by modified output (k = .98), and accuracy of modified output (k = .89).

Analysis

Instances of peer feedback were first summed up per dyad. To account for speech differences, normalised scores were obtained by dividing the sums by the total number of words per interaction. A mixed two-way ANOVA was conducted to compare the amount of peer feedback between the text- and video-chats across two familiarity (+/–) conditions. Sums (normalised scores) of peer feedback per dyad were then broken down according to type, accuracy, linguistic focus, and (in)accurate modified output. The data, however, did not meet normality assumptions as a result of the breakdown of frequency of peer feedback according to its characteristics. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to examine the differences in peer feedback characteristics between the text-and video-chats. To investigate learners’ perceptions of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity, learners’ interview responses were analysed using a content-based analysis approach (Dörnyei, Citation2007). The whole data were first read independently by the first and the third authors to locate and highlight segments that contain participants’ comments about the impact of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity on their provision of peer feedback. These highlighted segments were re-read and initial codes were created based on key words. The codes were then compared between the two independent coders (the two authors) to reach an agreement. Next, similar codes were grouped together into potential themes. Simple frequency counts (percentages) of the themes were then calculated, and quotes illustrating the themes translated from Vietnamese into English were presented.

Results

The results are organised into three sections. First, we present the quantitative findings about the impact of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity on the amount of peer feedback in learners’ L2 task-based interaction. The characteristics of peer feedback (e.g. type, linguistic focus, feedback’s accuracy, and modified output) are then presented and compared across the conditions. In the last section, we present qualitative findings about learners’ perceptions of the impact of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity.

Impact of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity on peer feedback

To answer the first research question which examines the impact of SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity on the amount of peer feedback, instances of peer feedback were first identified in the dataset and then sums of peer feedback instances per dyad were calculated. Overall, 347 instances of peer feedback were identified in the dataset, with 278 instances from the video-chat as opposed to 69 instances in the text-chat. presents descriptive statistics of raw and normalised scores of peer feedback per dyad in each condition.

Table 1. Frequency of peer feedback per dyad by SCMC mode and familiarity.

shows that for the familiarity (–) condition, the learners provided more peer feedback in the video-chat (M = .007, SD = .006) than in the text-chat (M = .002, SD = .003). Similarly, for the familiarity (+) condition, more peer feedback was provided in the video-chat (M = .008, SD = .005) than in the text-chat (M = .004, SD = .005). Additionally, the familiarity (+) group tended to provide more peer feedback than the familiarity (–) group in both the video-chat (M = .008, SD = .005 versus M = .007, SD = .006) and the text-chat (M = .004, SD = .005 versus M = .002, SD = .003), respectively.

A two-way mixed ANOVA shows no interaction effects between SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity on the amount of peer feedback, F(1,48) = .82, p = .38, ηp2 = .02; However, the main effects of SCMC mode on the amount of peer feedback were observed, F(1,48) = 17.21, p = .00001, ηp2 = .26. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons show that the amount of peer feedback in the video-chat was significantly higher in the video-chat than in the text-chat (p = .0001), with a medium effect size (d = .51). There were no main effects of interlocutor familiarity on the amount of peer feedback F(1,48) = 1.76, p = .19, ηp2 = .04. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons for interlocutor familiarity were non-significant (p = .19, d = .09).

Peer feedback was also examined in terms of type, linguistic focus, accuracy, and follow-up modified output. Of 278 instances of peer feedback identified in the video-chat (as reported above), 129 instances (46.40%) were recasts, followed by 58 (20.86%) clarification requests, 56 (20.14%) explicit corrections, 19 (6.83%) repetitions and 16 (5.77%) metalinguistic comments. Meanwhile, of 69 instances of peer feedback in the text-chat, 35 (50.72%) instances were clarification requests, followed by 19 recasts (27.54%), 8 (11.59%) explicit corrections, 5 (7.24%) metalinguistic comments, and 2 (2.91%) repetitions. summarises the breakdowns of the amount of peer feedback type per dyad in two SCMC conditions.

Table 2. Types of peer feedback.

In , the amounts of peer feedback in the video-chat were higher than in the text-chat across all feedback types. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests show that the learners provided significantly higher numbers of recasts (p = .001; r= .60), clarification requests (p = .001; r= .57) and explicit corrections (p = .003; r= .41) in the video-chat than in the text-chat. Effect sizesFootnote2 for these comparisons ranged from medium to large.

As for the linguistic focus, peer feedback was categorised into three groups: lexical, grammatical and multiple-linguistic focussed. Of 347 instances of peer feedback identified in the dataset, 154 (44.38%) were grammar-focussed as opposed to 127 (36.60%) lexis-focussed and 66 (19.02%) multiple-linguistic focussed. Both the video- and text-chat groups similarly produced higher amounts of grammar-focussed peer feedback (42.81% and 50.72%) than lexis-focussed (34.53% and 44.93%) and multiple-linguistic focussed feedback (22.66% and 4.35%), respectively. presents descriptive data of the amounts of peer feedback by linguistic focus.

Table 3. Feedback’s linguistic focus.

In , the learners provided greater numbers of lexical, grammatical and multiple-linguistic focussed instances of peer feedback in the video-chat than the text-chat. The differences reached significance as observed in the Wilcoxon signed-rank test results: grammar (p = .012, r = .36), lexis (p = .015, r = .34) and multiple-linguistic foci (p = .001, r = .51), with effect sizes ranging from medium to large.

For the accuracy of peer feedback, out of 347 instances of peer feedback identified, 80.12% (278) of them were accurate. Both the video- and text-chat groups similarly produced higher amounts of accurate (77.62% and 89.01%) than inaccurate peer feedback (22.38% and 10.99%), respectively. Breakdowns of the amounts of peer feedback by accuracy () show that the video-chat group produced significantly higher amounts of accurate (p= .002, r =.43) and inaccurate (p = .001; r = .47) peer feedback than the text-chat group. The differences show medium effect sizes.

Table 4. Accuracy of peer feedback.

Finally, of 347 instances of peer feedback, 310 (89.33%) were followed by modified output. Specifically, of 278 instances of peer feedback in the video-chat, 250 (89.92%) led to modified output, and 215 (86%) of these modified output instances were accurate. Meanwhile, of 69 instances of peer feedback in the text-chat, 60 (86.96%) resulted in modified output, and 51 (85%) of these modified output instances were accurate. presents the amount of modified output in two SCMC conditions.

Table 5. Modified output following peer feedback.

shows that there were higher numbers of modified output, accurate and inaccurate modified output in the video-chat (M = .006, SD = .004; M = .51, SD = .57; M = .002, SD=.002) than the text-chat (M= .003, SD= .003; M = .005, SD = .005; M = .001, SD=.002), respectively. Wilcoxon signed-rank test results show that the differences were significant with large effect sizes for modified output (p = .001; r = .85) and accurate MO (p = .0001; r = .64). The results were non-significant for inaccurate MO (p = .113; r = .22).

Learners’ perceptions of the impact of interlocutor familiarity

When asked whether the familiarity with partners affected feedback provision, ninety-seven out of a hundred learners (97%) reported that partner familiarity did not affect their feedback provision due to their positive relationship, and three learners (3%) perceived their interactions as neutral (i.e. neither liked nor disliked it), with no participants (%0) viewing their relationship as negative. The content-based analyses of the interview data revealed that the learners’ positive relationship established in the interaction and their previous experience were reported as reasons for determining their feedback provision. These results are exemplified in comments in Excerpts 1 and 2.

Excerpt 1. Feedback provision in the –familiarity pair: the impact of positive relationship

I did not see any problems with my new partner. In the first few minutes, I was kind of ‘testing’ and taking time to see how he responded when I corrected his errors. My partner seemed friendly and helpful, so we had a good interaction…we helped each other with language issues and completed the task on time. [Learner 24]Footnote3

Excerpt 2. Feedback provision in the + familiarity pair: the impact of previous experience

We used to study together and knew each other well, so it was a lot easy and comfortable. I could correct her errors if I noticed without worrying that she would be angry. I believe she felt the same way about correcting my errors and we could learn from each other. [Learner 49]

Excerpts 1 and 2 show that there were no perceived impacts of interlocutor familiarity on learners’ interaction and feedback provision. Prior familiarity with a partner helped learners feel ‘easy and comfortable’ to provide feedback. The unfamiliarity with new partners, however, did not negatively affect their feedback provision when these new partners showed to be ‘friendly and helpful’. These results supported the findings of the quantitative analyses reported above, that there were no main effects of interlocutor familiarity on the occurrence of peer feedback.

Learners’ perceptions of the impact of SCMC mode

When asked about the impact of SCMC mode on provision of feedback, a majority of learners (76%) reported that the video-chat was a better platform for offering feedback than the text-chat. Only 15% of learners said that they preferred the text-chat over the video-chat for feedback provision. The rest (9%) stated that SCMC mode did not affect their feedback provision. When asked to elaborate on the impact of SCMC mode, seventy-six learners who formerly reported to prefer the video-chat for feedback provision all converged to report six major factors related to the nature of the text-and video-chats: (1) interaction speed, (2) visibility of partner’s facial expression and emotions, (3) text-chat conventions, (4) time-lapse in composing messages, (5) visibility of errors and feedback, and (6) time for formulating feedback. The first factor is the speed of the interaction and time pressure cited by all participants as shown in Excerpt 3.

Excerpt 3. Interaction speed and time pressure

‘…it was very time consuming in the text-chat to provide feedback since we had to type. We often did not care much about errors if we could understand each other. We just kept moving to complete the task because the time was limited. For the video-chat, things were easier and quicker. Since we talked and discussed more, when we made errors, we corrected each other quickly. We could explain feedback effectively and quickly because we talked rather than typing. We could not do like this in the text-chat which was very slow…’ [Learner 20].

Excerpt 3 shows that infrequency of peer feedback was due to the pace and time-consuming characteristics of the text-chat (i.e. typing) as opposed to the video-chat (i.e. talking). The learners (100%) also reported to be under time pressure to complete the task and that providing peer feedback via typing rather than speaking seemed slow and ineffective, which led them to opt for not providing feedback.

Being unable to see each other’s facial expressions and emotions in the text-chat was another factor preventing learners (97.36%) from providing feedback, as exemplified in Excerpt 4.

Excerpt 4. Visibility of partner’s facial expression and emotions

‘In the text-chat, we did not see each other, so it was very difficult to know how the partner felt about my feedback. I was afraid that I could make my friend frustrated if I pointed out her errors. In the video-chat, I could see how my partner felt. It was like she was in front of me, so I could see her reactions if she was not comfortable with my feedback. If she was not happy, I would not provide feedback. Seeing my partner was very important since it helped me communicate easier and decide when it was necessary to correct my partner’s errors’. [Learner 31]

Excerpt 4 indicates that the text-chat precluded learners from seeing and judging their partner’s emotions through facial expressions. This consequently reduced the occurrence of peer feedback. Meanwhile, in the video-chat the learners could see and evaluate their partner’s response to his/her feedback.

Another factor affecting the provision of peer feedback, reported by 94.74% of learners, was the learners’ perceptions of the text-chat conventions as shown in Excerpt 5.

Excerpt 5. Learner perceptions of text-chat conventions

‘I don’t think it was necessary to correct language use in the text-chat because we used symbols, emoticons, phrases or short sentences rather than full sentences to make it quick. That is what texting is all about…we used symbols and emoticons to represent the language. So, how could we correct symbols and emoticons? We only asked for clarifications when we did not understand, but generally we could understand each other’s symbols well’. [Learner 22]

Excerpt 5 shows that learners perceived error correction and/or feedback provision as unnecessary in the text-chat given its conventions (e.g. abbreviations, phrases and short sentences, symbols and emoticons).

In addition, the learners (89.47%) did not provide feedback because of the long time-lapse in the text-chat. One learner explained this in Excerpt 6.

Excerpt 6. Time-lapse in composing messages

‘It took my partner a long time to compose the message. I had to wait for him to complete his message which often contained many lines. The time-lapse was long since he wrote many lines. In the end, I did not have time to tell him the errors. I decided to just focus on his ideas rather than language errors. But in the video-chat, I helped him right away because it was quick…we talked rather than typing’. [Learner 33].

Excerpt 6 indicates that the long time-lapse for writing the messages and the multiple lines of a text-message led the learners to opt for not pointing out peer’s errors and providing feedback. However, this learner admitted that he provided feedback in the video-chat because it was quicker when feedback was given in an oral form.

As for the 15% of learners who perceived the text-chat as suitable for feedback provision, two major reasons, cited by all these learners, emerged from their explanations. The first concerned the visibility of errors and feedback in the text messages (Excerpt 7).

Excerpt 7. Visibility of errors and feedback

‘In the text-chat, since we could see our messages, it was easier to notice the errors and thus we could correct each other. For me, it was easier to understand my partner’s feedback in the text-chat because I could see the feedback in writing. I am a slow learner, and my English was not good so it was easy for me to understand the feedback in writing rather than speaking which was too fast…I could read my partner’s feedback and clarify it if I did not understand’. [Learner 63]

Excerpt 7 shows that text messages created opportunities for learners to see errors in writing and thus they corrected each other’s errors more. Also, being able to see the feedback in writing helped them process and understand peer feedback.

The second factor was related to the time for formulating feedback. One learner expressed:

Excerpt 8. Time for formulating feedback

‘Providing feedback in writing was easier because I had time to formulate my feedback first in my mind and then explained it in writing. It was not possible in the video-chat because everything was fast. If my friend did not understand my feedback in the text, I could rearrange and rewrite my explanations [feedback]’. [Learner 85].

In Excerpt 8, the learner reported that the longer time lapse in text chats enabled them to better formulate and clarify the feedback.

Discussion

This study investigated whether interlocutor familiarity and SCMC mode affected frequency and characteristics of peer feedback in L2 interaction. The results show that learner familiarity did not affect the frequency of peer feedback. These results are not in line with the findings by Pastushenkov et al.’s (2020) study that reported the negative impact of learners’ unfamiliarity on learners’ LREs which include peer feedback. One possible reason could be learners of the present study had positive perceptions of peers and their newly established relationship during the interaction, and their anxiety level when communicating with unfamiliar peers was low (Satar & Özdener, Citation2008). Indeed, the learners reported that they did not have problems interacting with unfamiliar partners who were perceived as ‘helpful and friendly’. This indicates that the negative impact of interlocutor unfamiliarity could be reduced when learners perceive their unfamiliar peers positively and establish a good social relationship during the interaction. The results, however, support previous studies’ findings that familiarity with partners helped create a positive learning environment and increase feedback provision (Cao & Philp, Citation2006; Pastushenkov et al., 2020; Plough & Gass, Citation1993), since the learners reported to feel ‘comfortable’ and ‘easy’ to correct each other’s errors ‘without worrying that partners would be angry’ (Excerpt 2).

The second finding was that the video-chat group provided a greater amount of peer feedback than the text-chat group across types (i.e. recast, clarification request and explicit correction). Previous research suggested that the visibility of texts in SCMC helps learners notice language form and thus could result in more feedback (Lai & Zhao, Citation2006; Ortega, Citation2009; Smith, Citation2003, Citation2004). However, as indicated in the interview responses, various characteristics of the text-chat precluded the learners from providing feedback as compared to the video-chat. These included the slow pace of interaction (e.g. typing and time-consumption for composing messages), time pressure, and lack of visibility of visual cues. The results are in line with previous findings that learners continued their discussion without attending to mistakes and engaged in less correction in the text-chat than the video-chat (Baralt, Citation2013; Jepson, Citation2005; Yanguas, Citation2012). The learners also pointed out that the interaction pace in the text-chat was a stressor and increased time-demands rather than additional relaxed time (Sauro, Citation2011). These results support Zigler and Phung’s (2019) findings that the text-chat was perceived less effective and thus less preferrable than the video-chat.

The higher frequency of peer feedback in the video-chat could also be attributed to the learners being able to judge their partner’s emotions and reactions to their feedback via visual cues, as indicated in Excerpt 4. It should be noted that the text-chat was perceived as suitable for some learners because they reported that it enabled them to see errors and feedback and have time to formulate feedback (Lai & Zhao, Citation2006; Ortega, Citation2009). However, the number of the participants who favoured the text-chat over the video-chat for feedback provision was small (15% of the participants). Thus, the results overall suggest that the text-chat does not seem to be perceived as effective as the video-chat in terms of peer feedback provision.

Regarding feedback types, the results revealed that learners provided the highest number of recasts in the video-chat whereas they made more clarification requests in the text-chat. The most commonly cited reason is because recast is less intrusive and does not considerably affect the flow of the conversation in the video-chat (Loewen & Philp, Citation2006). This indicates that learners might have opted to provide more recasts rather than other feedback types. With regard to the highest amount of clarification requests in the text-chat, learners reported that they used this kind of feedback to clarify what they did not understand in the text. The frequent use of clarification requests could be ascribed to the limitations of text chat (e.g. lack of nonverbal cues and intonations). In Excerpt 5, one learner admitted that they often ‘asked for clarifications when they did not understand each other in the text-chat’. This suggests that learners seemed to perceive clarification requests as more suitable and prevalent as compared to other feedback types in the text-chat.

Another finding was that although the video-chat group provided more peer feedback than the text-chat group across all types, feedback in both groups targeted more grammatical than lexical aspects of language. The results could be related to the task’s nature. The task used in this study included a writing component, which might have encouraged learners to attend to grammar issues since they need to focus on grammatical accuracy of the jointly-produced texts (Azkarai & García Mayo, Citation2012).

Notably, a majority of feedback instances (80.12%) in both the video- and text-chats were accurate. One possible explanation is that learners in this study had good language knowledge because they were taught this knowledge explicitly in their English programs throughout their compulsory education. The results of learners’ high accuracy in feedback are very encouraging, which addresses the learners’ and teachers’ concern that peer feedback is often of low quality (Adams, Citation2007; Authors, XXXX; Sato & Lyster, Citation2012). As illustrated in Examples 1 to 6, all learners’ peer feedback instances accurately addressed the language issues. Only Example 7 shows that peer feedback was not accurate. These results suggest that learners are able to provide high quality feedback, which is more likely to result in higher accurate resolution of language issues (Yanguas & Bergin, Citation2018). It should be noted that since learners in the video-chat provided higher amounts of peer feedback than the text-chat group, they provided significantly higher amounts of both accurate and inaccurate peer feedback. Whether inaccurate peer feedback results in negative impact on L2 learning is not clear. However, it seems necessary to use pedagogical interventions in order to improve the quality of peer feedback given that some feedback is inaccurate (Sato & Lyster, Citation2012).

For the occurrence and accuracy of modified output, the results show that in both the video- and text-chats, a majority of peer feedback (89.33%) were followed by modified output and more than 85% of modified output were accurate. The high amount of modified output following peer feedback could be attributed to learners’ positive relationship established in the interaction. That is, learners felt comfortable interacting and trusted their peers’ feedback; therefore, they modified their output following their peers’ feedback. The learners’ high comfort level was confirmed in their interview responses, with 97% of them perceiving their interaction as positive and helpful. In addition, the high amounts of accurate modified output in both the video- and text-chats suggest that learners could modify their output accurately and thus could learn from each other via peer feedback.

Notably, the results show that there were more modified output and accurate output in the video-chat than the text-chat but there were no differences in inaccurate modified output between the two modes. One possible explanation is that turns or utterances in text-chat are intertwined and at times overlap with each other, so the learners might have missed seeing the feedback from partners and thus missed modifying the output. Meanwhile, for the video-chat, the turning taking is neater with each learner taking turns to talk. Thus, it is more likely that following a turn or an utterance where the partner provides feedback, the learner could hear it and modify his/her output accordingly. Also, the slow speed of the text-chat was cited by the learners as a factor preventing them from providing peer feedback and thus modified output, which could explain the low frequency of modified output in the text-chat. As suggested above, the learners in this study had good grammatical knowledge due to their extensive exposure to grammar-focussed instruction. Thus, as they modified their output, the output was more likely to be correct, and because the learners in the video-chat modified their output more often than the text-chat, they tended to produce more accurate modified output. Overall, the study provides evidence that learners modified their language production after receiving peer feedback especially in the video-chat and that their language modification was more likely to be accurate, which is essential and conducive to subsequent language learning (Gass & Mackey, Citation2015).

Conclusion

This study explored the impact of interlocutor familiarity and SCMC mode on peer feedback. The results revealed no differences in the amount of peer feedback between familiar and unfamiliar groups. This suggests that when learners perceive each other positively, whether they are familiar with peers does not seem to affect their provision of peer feedback. However, there were more instances of peer feedback in the video-chat than the text-chat. The results indicate that the video-chat creates more opportunities for learners to provide peer feedback than the text-chat. Notably, the linguistic focus of peer feedback as well as the frequency and characteristics of modified output following the feedback did not seem to be affected by both SCMC mode and interlocutor familiarity. Inevitably, the study has some limitations. First, it concerned only text- and video-chats, which excludes the multimodal SCMC where different technological elements of the text- and video-chats are integrated. This warrants additional research to explore the impact of both the text-, video- and multimodal SCMC on peer feedback. Second, the participants of this study shared the same L1 and relatively similar learning and cultural background, so it is not clear whether similar results about interlocutor familiarity could be observed in other groups of participants who have different linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Despite the limitations, the study suggests some implications. First, learners did not perceive partner unfamiliarity in SCMC as a problem for feedback provision when their partners were helpful and friendly. Therefore, it is important for teachers to create a supportive learning environment and promote learners’ mindset where learners can feel comfortable interacting with each other to reduce or alleviate the negative impacts of learner unfamiliarity. Second, given the greater amount of peer feedback in the video-chat, this modality could be used to support learners’ learning of an L2. Third, given the inaccurate peer feedback and inaccurate modified output that occurred, it is necessary to carry out pedagogical interventions to improve the quality of peer feedback and modified output.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Minh Chien Duong for his assistance in data collection. A special thanks to the students who participated in this study and to the teachers who allowed the data to be collected in their classes. We are also grateful to Language Learning’s Early Career Research Grant (2019) for its grant funding to the first author since a part of the data used in this study were collected thanks to its funding. All errors remain our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was partly funded by Language Learning’s Early Career Research Grant (2019).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Phung Dao

Phung Dao is a lecturer in TESOL and applied linguistics at the Department of Languages, Information and Communications, Manchester Metropolitan University, England. His research interests include classroom second language acquisition, peer interaction, learner engagement in task-based interaction, task‐based language teaching (TBLT), and second language pedagogy, Computer-Assisted Language Learning (CALL).

Phuong-Thao Duong

Mai Xuan Nhat Chi Nguyen, is a lecturer in TESOL and applied linguistics at the Department of Languages, Information and Communications, Manchester Metropolitan University, England. Her re-search interests include second language teacher education and development, second language teach-ing methodologies, and critical perspectives in TESOL.

Mai Xuan Nhat Chi Nguyen

Phuong-Thao Duong is a lecturer in the Faculty of Foreign Languages at Van Lang University. Her research interests include task-based language learning, vocabulary learning in a foreign language, and technology-enhanced language teaching/learning. She is also the editorial board member of the journal ITL-International Journal of Applied Linguistics.

Notes

1 TOEIC: Test of English for International Communication.

2 An effect size (r = Z/√N) of 10, .30 and .50 or above was considered small, medium and large, respectively.

3 All excerpts in the Results section were translated from Vietnamese into English.

References

- Adams, R. (2007). Do second language learners benefit from interacting with each other. In A. Mackey (Ed.), Conversational interaction in second language acquisition (pp. 29–51). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Arroyo, D., & Yilmaz, Y. (2018). An open for replication study: The role of feedback timing in synchronous computer‐mediated communication. Language Learning, 68(4), 942–972. doi:10.1111/lang.12300

- Azkarai, A., & García Mayo, M. P. (2012). Does gender influence task performance in EFL? Interactive tasks and language related episodes. In E. Alcón Soler & M. P. Safont Jordá (Eds.), Discourse and learning across L2 instructional contexts (pp. 249–278). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

- Baralt, M. (2013). Impact of cognitive complexity on feedback efficacy during online versus face-to-face interactive tasks. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 35(4), 689–725. doi:10.1017/S0272263113000429

- Baralt, M. (2014). Task sequencing and task complexity in traditional versus online classes. In M. Baralt, R. Gilabert, & P. Robinson (Eds.), Task sequencing and instructed second language learning (pp. 95–122). London: Bloomsbury.

- Baralt, M., Gurzynski-Weiss, L., & Kim, Y. (2016). The effects of task complexity and classroom environment on learners’ engagement with the language. In M. Sato & S. Ballinger (Eds.), Peer interaction and second language learning: Pedagogical potential and research agenda (pp. 209–239). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Bower, J., & Kawaguchi, S. (2011). Negotiation of meaning and corrective feedback in Japanese/English eTandem. Language Learning and Technology, 15, 41–71.

- Bueno-Alastuey, M. C. (2010). Synchronous voice computer mediated communication: Effects on pronunciation. CALICO Journal, 28(1), 1–20. doi:10.11139/cj.28.1.1-20

- Bueno-Alastuey, M. C. (2011). Perceived benefits and drawbacks of synchronous voice-based computer-mediated communication in the foreign language classroom. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24, 419–432.

- Bueno-Alastuey, M. C. (2013). Interactional feedback in synchronous voice-based computer mediated communication: Effect of dyad. System, 41(3), 543–559. doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.05.005

- Bryfonski, L., & Ma, X. (2020). Effects of implicit versus explicit corrective feedback on mandarin tone acquisition in a SCMC learning environment. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 42(1), 61–88. doi:10.1017/S0272263119000317

- Cao, Y., & Philp, J. (2006). Interactional context and willingness to communicate: A comparison of behavior in whole class, group and dyadic interaction. System, 34(4), 480–493. doi:10.1016/j.system.2006.05.002

- Cárdenas-Claros, M. S. (2020). Conceptualizing feedback in computer-based L2 language listening. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–26 doi:10.1080/09588221.2020.1774615.

- Chapelle, C. (2001). Computer applications in second language acquisition: Foundations for teaching, testing, and research. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, J., & Yang, S. C. (2014). Fostering foreign language learning through technology-enhanced intercultural projects. Language Learning & Technology, 18, 57–75.

- Cholewka, Z. (1997). The influence of the setting and interlocutor familiarity on the professional performance of foreign engineers trained in English as a second language. Spring Vale, Australia, Global Journal of Engineering Education, 1(1), 67–76.

- Dao, P., & Iwashita, N. (2018). Teacher mediation in L2 task-based interaction. System, 74, 183–193.

- DeKeyser, R. (2007). Skill acquisition theory. In B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (pp. 97–113). Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. New York: Oxford University.

- Egi, T. (2010). Uptake, modified output, and learner perceptions of recasts: Learner responses as language awareness. The Modern Language Journal, 94(1), 1–21. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00980.x

- Gass, S., & Mackey, A. (2015). Input, interaction and output in second language acquisition. In B. VanPatten & J. Williams (Eds.), Theories in second language acquisition: An introduction (2nd ed., pp. 180–206). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gass, S., & Varonis, E. M. (1984). Effect of familiarity on the comprehensibility of nonnative speech. Language Learning, 34(1), 65–87. doi:10.1111/j.1467-1770.1984.tb00996.x

- González-Lloret, M., & Ortega, L. (Eds.). (2014). Technology-mediated TBLT: Researching technology and tasks. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

- Gurzynski-Weiss, L., & Baralt, M. (2014). Exploring learner perception and use of task-based interactional feedback in FTF and CMC modes. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 36(1), 1–37. doi:10.1017/S0272263113000363

- Hung, Y. W., & Higgins, S. (2016). Learners’ use of communication strategies in text-based and video-based synchronous computer-mediated communication environments: Opportunities for language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(5), 901–924. doi:10.1080/09588221.2015.1074589

- Iwasaki, J., & Oliver, R. (2003). Chat-line interaction and negative feedback. Australian Review of Applied Linguistics. Series S, 17, 60–73. doi:10.1075/aralss.17.05iwa

- Iwashita, N., & Dao, P. (2021). Peer feedback in L2 oral interaction. In H. Nassaji & E. Kartchava (Eds.). The cambridge handbook of corrective feedback in language learning and teaching, (pp. 275–299). Cambridge University Press.

- Jauregi, K., Canto, S., de Graaff, R., Koenraad, T., & Moonen, M. (2011). Verbal interaction in second life: Towards a pedagogic framework for task design. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(1), 77–101. doi:10.1080/09588221.2010.538699

- Jepson, K. (2005). Conversations—and negotiated interaction—in text and voice chat rooms. Language Learning and Technology, 9, 79–98.

- Jung, Y., Kim, Y., Lee, H., Cathey, R., Carver, J., & Skalicky, S. (2019). Learner perception of multimodal synchronous computer-mediated communication in foreign language classrooms. Language Teaching Research, 23(3), 287–309. doi:10.1177/1362168817731910

- Katayama, A. (2007). Japanese EFL students’ preferences toward correction of classroom oral errors. Asian EFL Journal, 9, 289–305.

- Kozar, O. (2016). Perceptions of webcam use by experienced online teachers and learners: A seeming disconnect between research and practice. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(4), 779–810. doi:10.1080/09588221.2015.1061021

- Lai, C., & Zhao, Y. (2006). Noticing and text-based chat. Language Learning & Technology, 10, 102–120.

- Leeser, M. J., (2004). Learner proficiency and focus on form during collaborative dialogue. Language Teaching Research, 8, 55–81.

- Lee, L. (2006). A study of native and nonnative speakers’ feedback and responses in Spanish-American networked collaborative interaction. In J. A. Belz & S. L. Thorne (Eds.), Internet-mediated intercultural foreign language education (pp. 147–177). Boston: Thomson Heinle.

- Lenkaitis, C. A. (2020). Technology as a mediating tool: Videoconferencing, L2 learning, and learner autonomy. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(5–6), 483–509. doi:10.1080/09588221.2019.1572018

- Loewen, S., & Erlam, R. (2006). Corrective feedback in the chatroom: An experimental study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 19(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/09588220600803311

- Loewen, S., & Philp, J. (2006). Recasts in the adult English L2 classroom: Characteristics, explicitness, and effectiveness. The Modern Language Journal, 90(4), 536–556. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2006.00465.x

- Loewen, S., & Wolff, D. (2016). Peer interaction in F2F and CMC contexts. In M. Sato & S. Ballinger (Eds.), Peer interaction and second language learning: Pedagogical potential and research agenda (pp. 163–184). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Lyster, R., Saito, K., & Sato, M. (2013). Oral corrective feedback in second language classrooms. Language Teaching, 46(1), 1–40. doi:10.1017/S0261444812000365

- Mackey, A. (2012). Input, interaction and corrective feedback in L2 learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McDonough, K. (2005). Identifying the impact of negative feedback and learners’ responses on ESL question development. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27(01), 79–103. doi:10.1017/S0272263105050047

- Nassaji, H., & Kartchava, E. (2017). Corrective feedback in second language teaching and learning: Research, theory, applications, implications. New York: Routledge.

- Nassaji, H., & Swain, M. (2000). A Vygotskian perspective on corrective feedback in L2: The effect of random versus negotiated help on the learning of English articles. Language Awareness, 9(1), 34–51. doi:10.1080/09658410008667135

- Ortega, L. (1997). Processes and outcomes in networked classroom interaction: Defining the research agenda for L2 computer-assisted classroom discussion. Language Learning & Technology, 1, 82–93.

- Ortega, L. (2009). Interaction and attention to form in L2 text-based computer-mediated communication. In A. Mackey & C. Polio (Eds.), Multiple perspectives on interaction (pp. 226–253). New York, NY: Routledge.

- O’Sullivan, B. (2002). Learner acquaintanceship and oral proficiency test pair-task performance. Language Testing, 19(3), 277–295. doi:10.1191/0265532202lt205oa

- Pastushenkov, D., Camp, C., Zhuchenko, I., & Pavlenko, O. (2020). Shared and different L1 background, L1 use, and peer familiarity as factors in ESL pair interaction. TESOL Journal, 1–15. doi:10.1002/tesj.538

- Philp, J., Adams, R., & Iwashita, N. (2014). Peer interaction and second language learning. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Plonsky, L., & Ziegler, N. (2016). The CALL-SLA interface: Insights from a second-order synthesis. Language Learning & Technology, 20, 17–13.

- Plough, I., & Gass, S. (1993). Interlocutor and task familiarity: Effect on interactional structure. In S. Gass & G. Crookes (Eds.), Tasks and language learning (pp. 35–56). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Poteau, C. (2011). Effects of interlocutor familiarity on second language learning in group work. Unpublished Dissertation, Temple University.

- Ranta, L., & Lyster, R. (2007). A cognitive approach to improving immersion students’ oral language abilities: The Awareness–Practice–Feedback sequence. In R. DeKeyser (Ed.), Practice in a second language: Perspectives from applied linguistics and cognitive psychology (pp. 141–160). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Salomonsson, J. (2020). Modified output and learner uptake in casual online learner-learner conversation. System, 93, 102306. doi:10.1016/j.system.2020.102306

- Sanz, C. (2004). Computer delivered implicit versus explicit feedback in processing instruction. In B. VanPatten (Ed.), Processing instruction: Theory, research and commentary (pp. 241–254). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Sanz, C., & Morgan-Short, K. (2004). Positive evidence vs. explicit rule presentation and explicit negative feedback: A computer assisted study. Language Learning, 54(1), 35–78. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9922.2004.00248.x

- Satar, H. M., & Özdener, N. (2008). The effects of synchronous CMC on speaking proficiency and anxiety: Text versus voice chat. The Modern Language Journal, 92(4), 595–613. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2008.00789.x

- Sato, M., & Ballinger, S. (2016). Peer interaction and second language learning: Pedagogical potential and research agenda. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Sato, M., & Lyster, R. (2012). Peer interaction and corrective feedback for accuracy and fluency development: Monitoring, practice, and proceduralization. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 34(4), 591–626. doi:10.1017/S0272263112000356

- Sauro, S. (2009). Computer-mediated corrective feedback and the development of L2 grammar. Language Learning & Technology, 13, 96–120.

- Sauro, S. (2011). SCMC for SLA: A research synthesis. CALICO Journal, 28(2), 369–391. doi:10.11139/cj.28.2.369-391

- Sheen, Y., & Ellis, R. (2011). Corrective feedback in language teaching. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 593–610). New York: Routledge.

- Shih, Y. C. (2014). Communication strategies in a multimodal virtual communication context. System, 42, 34–47. doi:10.1016/j.system.2013.10.016

- Smith, B. (2003). Computer-mediated negotiated interaction: An expanded model. The Modern Language Journal, 87(1), 38–57. doi:10.1111/1540-4781.00177

- Smith, B. (2004). Computer-mediated negotiated interaction and lexical acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26(03), 365–398. doi:10.1017/S027226310426301X

- Sotillo, S. (2005). Corrective feedback via instant messenger learning activities in NS-NNS and NNS-NNS dyads. CALICO Journal, 467–496.

- Sotillo, S. M. (2009). Learner noticing, negative feedback, and uptake in synchronous computer-mediated environments. In L. B. Abraham & L. Williams (Eds.), Electronic discourse in language learning and language teaching pp. (87–110). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Swain, M. (2005). The output hypothesis: Theory and research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning pp. (471–483). New York: Routledge.

- van Compernolle, R. A. (2015). Interaction and second language development: A vygotskian perspective. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Wigham, C. R., & Chanier, T. (2015). Interactions between text chat and audio modalities for L2 communication and feedback in the synthetic world second life. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(3), 260–283. doi:10.1080/09588221.2013.851702

- Yanguas, I. (2010). Oral computer-mediated interaction between L2 learners: It’s about time. Language Learning & Technology, 14, 72–93.

- Yanguas, I. (2012). Task-based oral computer-mediated communication and L2 vocabulary acquisition. CALICO Journal, 29(3), 507–531. doi:10.11139/cj.29.3.507-531

- Yanguas, I., & Bergin, T. (2018). Focus on form in task-based L2 oral computer-mediated communication. Language Learning & Technology, 22, 65–81.

- Yoshida, R. (2010). How do teachers and learners perceive corrective feedback in the Japanese language classroom? The Modern Language Journal, 94(2), 293–314. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.2010.01022.x

- Ziegler, N. (2016). Taking technology to task: Technology-mediated TBLT, performance, and production. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 36, 136–163. doi:10.1017/S0267190516000039

- Ziegler, N., & Phung, H. (2019). Technology-mediated task-based interaction: The role of modality. ITL - International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 170(2), 251–276. doi:10.1075/itl.19014.zie

Appendix

An open-ended questionnaire

Have you met before?

Are you close friends and classmates in any English classes?

Have you worked together before in pair/group work?

If yes, how many times have you worked together before?

Indicate your familiarity with your partner on the 10-point Likert scale (1 = not familiar, 10 = very familiar).

Interview prompts

What do you think about the impacts of working with a close friend/classmate versus an unfamiliar partner on your feedback provision and interaction?

How did you perceive your relationship with your partners in the last interactions (positive, negative and neutral)? Please make a comparison between a familiar partner and a partner who you just met with regard to its impact on feedback provision,

Did SCMC mode affect your interaction and feedback provision? If yes, how? If no, why not?

Which SCMC mode (i.e. text- or video-chats) made it easier and suitable for you to provide feedback? Please compare two SCMC modes.

Task pictures

Set 1. Missed flight incidentSet 2. Flat tyre incident