Abstract

Speaking skills generally receive little attention in traditional English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms, and this is especially the case in secondary education in Indonesia. A vocabulary deficit and poor pronunciation skills hinder learners in their efforts to improve speaking proficiency. In the present study, we investigated the effects of using two language learning websites, I Love Indonesia (ILI) and NovoLearning (NOVO). These websites are equipped with Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) technology, with each website providing different types of immediate feedback. We measured written receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge of 40 target words before and after the intervention in which 146 students practiced with these two ASR-based websites, and compared it to that of a control group (n = 86). The ASR-based websites successfully helped students enhance their receptive vocabulary. Twenty-four students participated in a spoken pre-and post-test pronouncing the same 40 target words. We successfully developed an approach to measure pronunciation skills which showed that the treatment groups outperformed the control group. Our results indicate that our technology is successful in improving vocabulary and pronunciation skills.

1. Introduction

‘Look, look! I can speak (English words on NOVO) correctly!’

‘What score did you get (on NOVO)? I got this (feeling proud)!’

‘I got ‘excellent’ (when speaking on ILI)!’

(Excerpts from the first author’s note-taking during classroom observations)

Speaking skills are a vital component of the curriculum in Foreign Language (FL) teaching. Learners need to be sufficiently equipped with speaking skills necessary for communication in the target language. Unfortunately, in traditional teacher-centred FL classrooms, learners often receive little opportunity to practice speaking with appropriate feedback (Cucchiarini & Strik, Citation2019) and outside of class they encounter difficulties in finding an interlocutor or speaking partner (Timpe-Laughlin et al., Citation2020).

One of the common speaking problems that many FL learners experience is inadequate vocabulary knowledge, which is often associated with lower levels of oral proficiency. Vocabulary has frequently been underestimated in FL classrooms (Dodigovic & Agustín-Llach, Citation2020). Studies (Dodigovic, Citation2005; Nation, Citation1990; Thornbury, Citation2002) categorize vocabulary knowledge into receptive and productive. Receptive knowledge refers to being able to understand spoken and/or written words, while productive knowledge relates to the ability to use words accurately in a written form and/or in speech (Pignot-Shahov, Citation2012). Such a distinction is necessary in the pedagogy of oral training. This implies that FL learning facilitators and learners need to be aware that oral activities generally happen after sufficient receptive knowledge is in place. Uchihara and Clenton (Citation2020) observed a relatively strong correlation between receptive vocabulary size and oral lexical proficiency based on human ratings. Uchihara and Saito (Citation2019) found that productive vocabulary knowledge significantly correlated with Second Language (L2) oral ability, especially fluency.

Besides vocabulary, another aspect that FL learners struggle with is pronunciation. Albeit frequently neglected in teaching (e.g. Brown & Yule, Citation1983; Derwing & Rossiter, Citation2002), pronunciation is essential for learners to speak accurately and clearly. Studies have shown that communication competence in an FL is directly linked to the speaker’s level of pronunciation (e.g. Goh & Burns, Citation2012; Morley, Citation1991; Offerman & Olson, Citation2016). To favour optimal pronunciation learning, tailored feedback should be immediately given after utterances have been spoken (Cucchiarini et al., Citation2012). However, providing individualized corrective feedback by FL teachers on all learners appears to be time-consuming, costly, and not feasible, particularly in the FL classroom (Cucchiarini et al., Citation2012).

Recent studies on technological developments have suggested Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) technology as a fruitful tool for honing FL learners’ speaking skills. Some of these ASR-based systems are Carnegie Speech NativeAccent (Eskenazi et al., Citation2007), EduSpeak (Franco et al., Citation2010), Japañol (Tejedor-García et al., Citation2021), My Pronunciation Coach (Cucchiarini et al., Citation2012), NovoLearning (NovoLearning Research Report, Citation2019), Saybot (Chevalier, Citation2007), DISCO (van Doremalen et al., Citation2016), GREET (Penning de Vries et al., Citation2020), the PARLING system (Neri et al., Citation2008), SPELL (Morton & Jack, Citation2010), Rosetta Stone (www.rosettastone.com), ElsaSpeak (www.elsaspeak.com), Speechace (www.speechace.com), and English Central (www.englishcentral.com). In their review study Golonka et al. (Citation2014) pointed out that although ASR accuracy is not 100%, learners can have positive experiences when using ASR-based software. Chen (Citation2016) reported that most students enjoy using an ASR-based website and that the website could support students in improving their English speaking skills. Cucchiarini et al. (Citation2009) found that, although the developed ASR-based system did not reach 100% accuracy in detecting students’ errors, the feedback provided was effective in helping students improve their pronunciation after a shorter duration of practice. While error rates by ASR technology remain relatively high (e.g. Evanini et al., Citation2018; Morton et al., Citation2012), interacting with spoken activities on a computer may encourage more willingness to take part in speaking activities in the second or foreign language (Golonka et al., Citation2014). Additionally, studies by McAndrews (Citation2020), Yenkimaleki and van Heuven (Citation2019), and Yenkimaleki et al. (Citation2021) encourage the implementation of technology-enhanced language learning as it has been proven effective in helping improve learners’ pronunciation skills, especially prosody.

Researchers have begun to apply free speech-to-text processing ASR, among others, Windows Speech Recognition (WSR) (e.g. McCrocklin, Citation2016) or Google Speech Recognition (GSR) (e.g. Mroz, Citation2018) for oral practice focusing on pronunciation. McCrocklin et al. (Citation2019) reported that the GSR engine can correctly decode 93% of free non-native speech, but other speech recognition software generates significantly lower results. For instance, WSR can correctly decode 74% of free speech (McCrocklin et al., Citation2019), and Apple’s Siri only 67% (Daniels & Iwago, Citation2017). In Daniels and Iwago (Citation2017) study, the GSR engine performed better than Siri as regards: (a) the accuracy at recognizing second language speech, (b) the ability to make corrections more intelligently, and (c) being relatively easy to integrate into web-based language learning applications.

Despite its growing popularity and affordances, relatively little research has investigated the impact of ASR technology on FL learners’ speaking skills in educational settings in Indonesia. This is surprising as ASR offers a form of oral practice with feedback that might be particularly beneficial to overcome contextual constraints of FL teaching and learning, especially speaking. For example, low competence of teachers, large class size, student resistance to participation, structure-oriented textbooks, noncommunicative testing, and limited time allotment for teaching (Ariatna, Citation2016) are some of the relevant contextual challenges to date. Andy et al. (Citation2020) argued that lack of knowledge on features such as nuclear stress and vowel length can cause Indonesian Accented English (IAE) to be unintelligible. In addition, there has been concerns that promoting English in Indonesia may create problems such as learners being Anglicized or ‘imitative of the British or the Americans’ (Dewi, Citation2017), and this can trigger learners to aim for native-likeness as their only ultimate goal in speaking (pronunciation).

Due to a paradigm shift, recently, the notion of intelligibility in FL learning and teaching has drawn increasing interest from scholars around the world (e.g. Munro & Derwing, Citation1999; Citation2015; Citation2020), which encourages learners to have more freedom not to sound ‘too British or American’ and need not to worry too much about their local accent. Interestingly, the presence of ASR-based language learning systems may accommodate learners who pursue native-likeness and/or those who focus on being comprehensible and/or intelligible in speaking, as ASR offers flexibility in, among others, two criteria of the so-called ‘Smart-CALL systems’ suggested by Colpaert (Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020), namely ‘personalization’ and ‘contextualization’.

To address this knowledge gap, we employed two language learning websites equipped with ASR technology, namely I Love Indonesia (ILI) and NovoLearning (NOVO). Two preliminary studies (Bashori et al., Citation2020, Citation2021) evaluated these ASR-based websites and investigated to what extent they affect learners’ cognitive and affective domains. The results revealed that these websites were evaluated positively and helped learners improve their vocabulary knowledge, reduce their speaking anxiety, and enhance their language enjoyment.

The aims of the present study are to get more insight into the kind of linguistic gain the students made. English was the target language in this study. Our vocabulary test consisted of three different parts and these parts may provide relevant information on the receptive and productive aspects of learning vocabulary. In addition, we asked a subset of the students to pronounce target words, as pronunciation might be an aspect that is affected directly through ASR systems. We also employed an open-source software package, the Automated Phonetic Transcription Comparison Tool (APTct), to help analyze learners’ speech. The APTct is a readily available web-based application developed recently by Bailey et al. (Citation2021). This tool allows the comparison between reference and hypothesis phonetic transcriptions that use International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) symbols. We address the following research questions:

To what extent do ILI and NOVO positively affect students’ receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge?

To what extent do ILI and NOVO positively impact students’ pronunciation?

2. The relevance of ASR in EFL learning in Indonesia

Indonesia is the second most linguistically diverse nation in the world after Papua New Guinea (Simons & Fennig, Citation2017). Javanese is spoken by 40.2% of the nation’s population (BPS, Citation2011), while Indonesian or Bahasa Indonesia is used as a national and official language and the main means of communication. Within this internal superdiverse context, English, an external language, obtained a unique position as a Foreign Language (EFL), also in the country’s educational system. English became a compulsory subject taught in secondary and tertiary education, but not yet in primary education (Zein et al., Citation2020).

Zein (Citation2019) argued that Indonesia continues to establish its reputation as one of the largest and significant markets of English language education. This argument is based on the country’s status as the fourth most populous nation in the world and home to the world’s largest Muslim population (BPS, Citation2011). Despite the debate about English versus national identity and English versus Islam, Dewi’s (Citation2015) study revealed that students and teachers hold a positive perception of English and support the promotion of English in Indonesia.

The popularity of English in the national curriculum comes together with challenges in teaching language skills, especially speaking. Swan and Smith (Citation2001) identified a number of linguistic problems Indonesian learners encounter when learning English, such as differences in (a) phonology (vowels, consonants, spelling and pronunciation, rhythm and stress, intonation), (b) orthography and punctuation, (c) grammar, (d) vocabulary and style, and (e) culture. Wahyuningsih and Afandi (Citation2020) found at least six major problems faced by Indonesian students in learning to speak English; inadequate vocabulary, insufficient grammar mastery, poor pronunciation, less input of English outside of class, low confidence, and lack of English speaking curriculum development. Technology and social media can help face these challenges. This calls for substantial efforts to develop speech-enabled language learning systems, e.g. using Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR), which will help learners practice and improve their oral performance.

ASR technology has been widely acknowledged as a useful language learning tool in Foreign Language (FL) classrooms. In educational settings in Indonesia, two ASR-based websites used in the EFL classroom, I Love Indonesia (ILI) and NovoLearning (NOVO), have been evaluated positively by 167 secondary school students through a mixed-methods research (Bashori et al., Citation2020). This is in line with similar findings of a case study by van Doremalen et al. (Citation2016) that reported positive evaluations of an ASR-based language learning system by learners, teachers, and experts. In a follow-up study, these speech-enabled websites (ILI and NOVO) also appeared to improve English vocabulary knowledge, to reduce speaking anxiety, and to enhance language enjoyment of 146 students (Bashori et al., Citation2021). Vocabulary learning was investigated in Bashori et al. (Citation2021) in a global way, without making a distinction between productive and receptive knowledge. Considering that ASR, by nature, can allow learners to practice speaking, many studies have explored its affordances for pronunciation learning, finding that it can be useful in various respects (McCrocklin, Citation2016, Mroz, Citation2018; Neri et al., Citation2008).

However, relatively little research has investigated the benefits of using ASR to help Indonesian EFL learners improve their pronunciation quality, while various studies have provided useful inventories of English pronunciation difficulties by Indonesian learners (Dewi, Citation2009; Fakhrunnisa, Citation2015; Herman, Citation2016; Kosasih, Citation2017). Therefore, in the present study we investigate the use of ILI and NOVO and examine to what extent these systems affect learners’ linguistic achievement, more specifically on receptive and productive vocabulary and pronunciation skills.

3. Methodology

The present study is based on the data presented in Bashori et al. (Citation2021). In that study, both quantitative and qualitative data on vocabulary knowledge in general, foreign language speaking anxiety, and foreign language enjoyment were collected in a quasi-experimental design. In the present study we conducted a more detailed investigation of receptive and productive vocabulary learning and pronunciation skills.

3.1. Participants

A total of 232 first-year students (222 male; 10 female) at a vocational high school in Indonesia participated in this study. The participants were recruited from nine classes and were divided into two treatment groups and a control group. The treatment group A (n = 67) was asked to try I Love Indonesia (ILI), while the treatment group B (n = 79) used NovoLearning (NOVO). Eighty-six students in the control group received no web-based intervention and attended their regular classes.

The participants’ age ranged from 14 to 17 years with most of them having learned English for between five and ten years. To investigate the participants’ level of English proficiency, an Anglia Examination Online Placement Test (https://www.anglia.org/placement-test) was administered at the beginning of the study. There was a total of 100 questions, but the test terminated sooner for lower levels. The Anglia Examination levels correspond to the CEFR levels, but there is no exact equivalence between these two exam levels. The results indicated that the majority of the participants (n = 211) achieved a below-A1 level of English proficiency.

3.2. Procedure and instruments

below lists the steps in the present study, the measuring instruments, and the students who participated in each of the steps.

3.2.1. Vocabulary test

From a narrative text titled Malin Kundang, one of the learning materials in the current English language syllabus and curriculum in Indonesia, 40 English words were selected (see Appendix A). We adapted a study by Ma and Kelly (Citation2006) when designing the vocabulary test. The vocabulary test included in part (1) a receptive, multiple-choice test, (2) a receptive, word-translation matching test. In part (2), the 40 words were divided into four sections. Each section contained 10 words with 11 available choices. There was one pure distractor in each of these sections, which had no equivalent Indonesian translation with the targeted words. Part 1 and 2 were based on the concepts of the receptive recognition test and the vocabulary level test, respectively (Laufer & Nation, Citation1995). Part (3) was a productive gap-filling test (40 test items). The initial letter(s) and the Indonesian translations for each missing word had been given. Part 3 used the controlled active vocabulary test (Laufer, Citation1998). Examples of test items are given in Appendix B.

3.2.2. Pronunciation test

To investigate the improvement in pronunciation skills after using the ASR-based websites, a personalized word-level pronunciation (pre- and post-) test was administered to a subset of the participants (n = 24) from three groups (control, treatment A/ILI, and treatment B/NOVO – each consisting of eight students). They were asked to pronounce the set of target words of the vocabulary before and after the intervention and were recorded.

To evaluate the recordings, we collected judgments from two experts and employed an open-source software, the Automated Phonetic Transcription Comparison Tool or APTct (https://aptct.auburn.edu/), an online tool that enables the comparison of phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) developed by Bailey et al. (Citation2021).

Expert 1 was an independent, professional English teacher in Indonesia (non-native English speaker; TOEFL score = 590) who gave ratings on a three-point scale; the highest score of 3 was given to recordings that were highly intelligible and considered ‘correct’ by the rater. In order not to be dependent on only one expert, 25% of the pronunciation data was rechecked and rated by a more experienced rater, Expert 2, an assistant professor in a university in the Netherlands who is highly experienced in pronunciation. We examined the reliability between the ratings from the two experts; pre-test (.686), post-test (.879), and combination (.833). The reliability was acceptable, and the items were consistent in a satisfactory way. Therefore, we continued with the ratings of Expert 1.

Finally, the first author manually transcribed the recordings using the IPA. To avoid any potential bias and ensure objectivity, six samples amounting to 25% of the transcriptions (two from each of the control and treatment groups) were randomly selected and thoroughly evaluated by Expert 2. To reach a consensus the first author and Expert 2 discussed the discrepancies and disagreements over the phonetic transcriptions through Zoom. After discussion with the first author, Expert 2 concluded that the transcriptions were mainly fine and reasonable. One point of the discussion remained: vowel length. Particularly in relation to the word news, Expert 2 was in doubt whether all the six speakers pronounced this word with a long or a short vowel. She stated that this might be caused by the following consonant/s/that made the vowel’s length seem to be somewhat longer when pronounced. In this case, the first author transcribed the word news as/njʊs/with the short vowel/ʊ/for all the 12 samples (pre- and post-test).

A feature left out in the analysis is word stress. The first author did not indicate any stress sign at all in his transcription, while Expert 2 generally indicated that the speakers often stressed the last syllable. This might be considered for future research.

After reaching agreement with Expert 2, the first author employed the web-based APTct to measure the overall phonetic distance between two transcriptions, for instance a reference transcription or RT (the optimal pronunciation of the targeted utterances) and the hypothesis transcription or HT (the participants’ actual pronunciation of the utterances). We obtained RT by consulting the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, while for HT we included all the transcriptions from the 24 participants (n = 24x2x40 = 1,920 transcribed words). Since it is not possible to upload multiple entries at once, we had to input RT and HT (word after word) by hand in the provided separate slots, so that the tool automatically generated the outcomes (see Bailey et al. (Citation2021) for further explanation).

3.2.3. ASR-based experiments

The ASR-based experiments were held in the school’s computer laboratory, lasted for approximately six hours (360 minutes), and were carried out in about two weeks. Three classes (the treatment group A) used ILI, and the other three (the treatment group B) used NOVO.

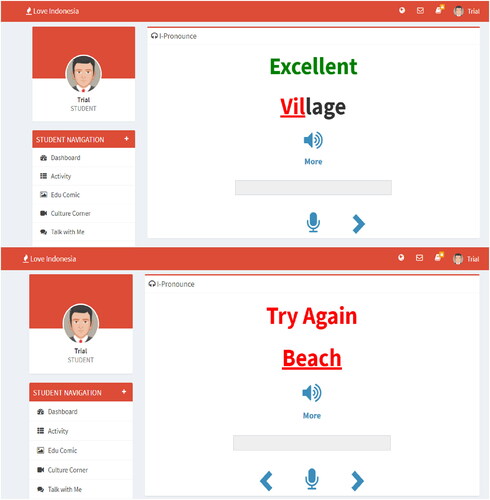

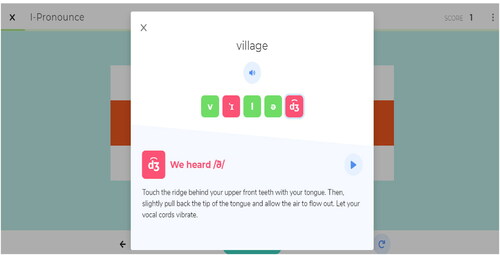

There were five main activities on the websites; i-watch, i-read, i-hear, i-pronounce, and i-speak. The first three activities included watching two videos related to the topic of narrative text, reading information that contained a pertinent picture about the narrative text, and choosing the correct word(s) from two similar options spoken by the websites. In the last two activities, i-pronounce and i-speak, the users were asked to pronounce the targeted words, and feedback was provided by means of ASR technology (see and ).

ILI only gave simple feedback on pronunciation such as ‘excellent’ for the correct answers and ‘try again’ for the incorrect ones. The second website, NOVO, provided its users with more sophisticated feedback on phonetics. and are the screenshots of the feedback samples provided by ILI and NOVO.

Meanwhile, the control group employed a similar amount of time for practicing the same topic (narrative text). They did not perform any ASR-based activities and just attended their regular classroom meetings. The teachers in charge of teaching the students in the control group mainly used a group-discussion technique; the former asked the students to give a presentation, but the latter did not require any presentation sessions. Further details can be found in Bashori et al. (Citation2020, Citation2021).

4. Results

4.1. The effects of ASR-based websites on students’ receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge

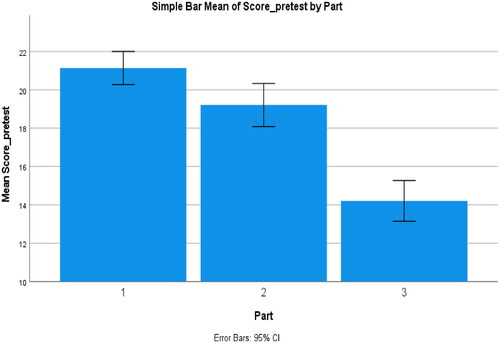

The items of the three parts of the vocabulary (pre and post) test were found reliable with Cronbach’s alpha values of above 0.80. Cronbach’s alpha values of the three post-test parts were higher than those of the pre-test (part 1: pre: 0.842, post: 0.913; part 2: pre: 0.921, post: 0.949; part 3: pre: 0.936, post: 0.954). The mean values of these three parts and their confidence intervals are given in .

An analysis of variance on the three test parts returned significant differences between the mean scores (F2, 462) = 262.99, p = .000). All differences between the parts were significant (pairwise comparisons, Bonferroni procedure, alpha = .05). The productive test was clearly the most difficult, but the difference between the two receptive parts was also significant. The second part was a bit harder than the first part. The correlations between the three parts are high (varying between .817 and .850), indicating that all the three parts relate to vocabulary knowledge in general.

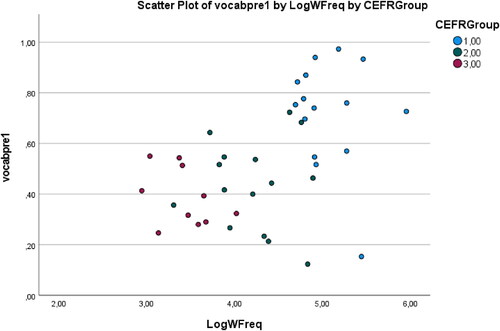

illustrates how the words in the vocabulary pre-test part 1 were distributed in connection to their Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) word frequency (its log value) and Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) levels. We divided the CEFR levels into three groups; A1/A2, B1/B2, C1/C2/unknown). Appendix A gives their values for the 40 target words involved.

Figure 4. Word distribution in the vocabulary pre-test and its correlation with the COCA word frequency and CEFR levels.

shows the regular structure of the vocabulary knowledge at the pre-test, which portrays the different sections of the lexicon. The two outliers (down, right side) were the words ‘become’ and ‘chase’. Overall, the students’ vocabulary knowledge is often predicted by the word frequency and the CEFR level.

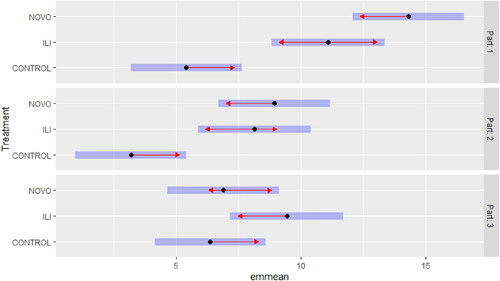

The gain scores from each part of the vocabulary test were analyzed by employing the R package lme4 for a mixed linear effects regression. By doing this, we could control for clustering effects of the nine classes in our research design. The results indicated that the treatment groups (three classes using ILI and another three using NOVO) significantly outperformed the control group (three classes) in the first two parts of the vocabulary test. There were no significant differences between the two treatment groups. There were no significant differences in part 3, the productive part. The gain scores in the three parts of the vocabulary test are visualized in .

shows that all three groups made progress in vocabulary knowledge in all three test parts. None of the confidence intervals includes the zero value.

4.2. The effects of ASR-based websites on students’ pronunciation

4.2.1. Expert ratings

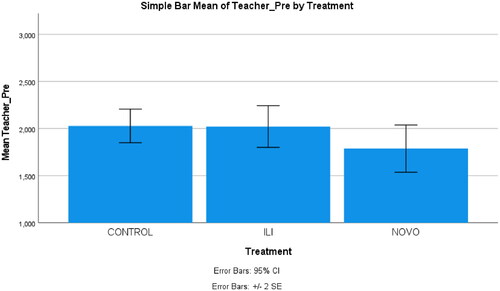

The overall items in the pronunciation pre- and post-tests were initially checked, and the results indicated high reliability with Cronbach’s alpha values of .892 and .914, respectively. We investigated the differences between the three groups in the pre-test and found no significant differences; F(2,21) = 1,568, p = .232 ().

We also delved into which words were the easiest and most difficult to pronounce in the pre-test based on the expert ratings. Words vary between ‘yell’ (2.92) and ‘prosperous’ (1.21). This indicates that the one-syllable word such as ‘yell’ is easily pronounced, while the three-syllable word like ‘prosperous’ is considered the most challenging.

Figure 6. Simple bar of the experts’ (rating) mean scores on the pronunciation pre-test by the control and treatment groups.

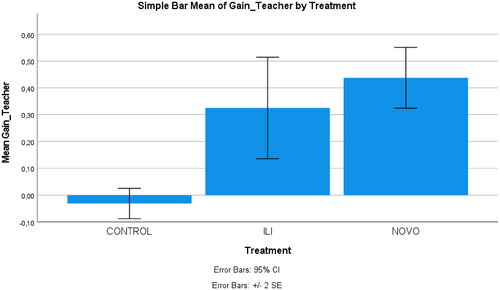

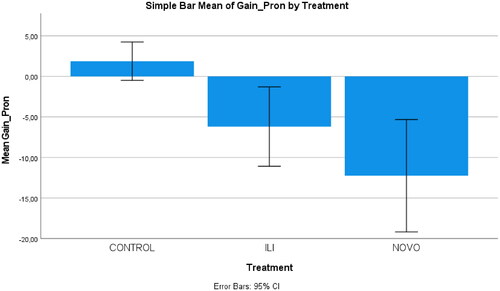

To examine the differences between the pronunciation pre- and post-test scores in the three research groups, an ANOVA was applied on the gain scores. The effect of treatment was significant (F(2,21) = 13.883, R2 = .569). Post hoc tests, multiple comparisons, and Tamhane T2 showed that the treatment groups significantly differed from and outperformed the control, while there were no significant differences between the treatment groups. There was no significant change or improvement in the control group. visualizes the teachers’ (rating) gain scores on pronunciation and their confidence intervals in the three research groups.

4.2.2. Results of comparing the phonetic transcriptions using the APTct

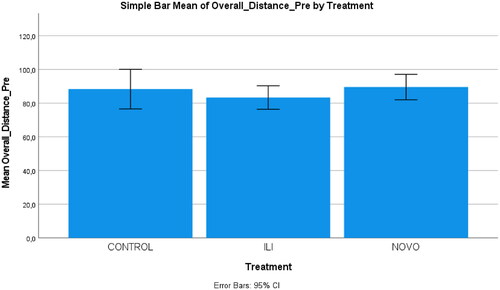

The web-based APTct generated the phonetic distance scores between the reference and the hypothesis transcriptions. In our study there were two hypothesis transcriptions, those in the pre-test and those in the post-test. We found large differences between means and varying degrees of variation (the word ‘yell’ has no variation). The items in the pre- and post-tests were also checked, and the results showed high reliability with Cronbach’s alpha values of .873 and .905, respectively. All item-rest sum correlations were positive (zero for ‘yell’). Removing specific words did not really raise the alpha. We decided to keep the 40 words as one scale. To investigate the differences between the research groups in the pre-test, we employed an ANOVA and found no significant outcomes; (F(2, 21) = .540, p = .000, R2 = .591) ().

We also examined which words were the easiest and most difficult to pronounce in the pre-test based on the phonetic distance. Word ‘yell’ is the easiest to pronounce (M = 0.0), while the hardest one is ‘confused’ (M = 6.42). This outcome is similar to the results of the expert ratings.

Figure 8. Simple bar of the mean scores of the overall phonetic distance in the pronunciation pre-test by the control and treatment groups.

To investigate the differences between the pre- and post-test distance (gain) scores in the three research groups, we employed an ANOVA. The effect of treatment was significant; F(2,21) = 7.758, p = .000, R2 = .425. The smaller distance (gain) scores reflect a higher quality of the hypothesis transcriptions. Post hoc tests, multiple comparisons, and Tamhane T2 showed that the treatment groups significantly differed from and outperformed the control, while there were no significant differences between the treatment groups. There was no significant change or improvement in the control group. visualizes the means of the phonetic distance gain scores on pronunciation and their confidence intervals in the three research groups.

Figure 9. Simple bar of the means of the phonetic distance (gain) scores by the control and treatment groups.

When compared to the expert ratings, we found a strong correlation between the two gain scores at −.778, which shows that the two measures are highly correlated and complementary, but at the same time possess distinct characteristics. The negative value here merely indicates that the two measures have an opposite way of assessing pronunciation skills.

One remarkable point from the results of using these two measures is that the control group did not indicate any significant gain at all. The zero-value included in the confidence interval.

The summary of the main results can be seen in .

4.3. Interviews on the effects of the ASR-based websites on the students’ vocabulary and pronunciation

We interviewed 12 students from the two treatment groups (ILI and NOVO) regarding their experiences using the ASR-based websites. Overall, all the students perceived the websites positively and stated that the websites, in combination with one of the Indonesian folklore stories, helped them improve their (receptive and productive) vocabulary and pronunciation skills.

Participant NOVO03 said that, through the website (NOVO), he learned vocabulary that previously he did not know. Participant ILI01 mentioned that the website (ILI) helped him understand English word by word, so that he could use the words. Regarding pronunciation, Participant NOVO03 stated that he learned how to pronounce the words. Participant ILI01 added that the ASR-based speaking activities on the website helped him improve his confidence.

However, Participant ILI02 pointed out that she had trouble using one of the ASR-based features on the website. Participant ILI03 also said that getting her voice recognized correctly on the website was difficult. Participant NOVO01 found that sometimes the ASR-based system did not succeed in recognizing his correct utterances or provided him with the false feedback.

Additionally, we interviewed three English teachers, and they stated that the majority of their students suffered from a vocabulary deficit. All the teachers supported the use of ASR-based websites (ILI and NOVO) because the websites facilitated students’ English vocabulary learning. Teacher T01 stated that: (The ASR-based websites) surely helps the students speed up their vocabulary mastery. Teacher T02 and T03 mentioned that the ASR-based websites also helped the students learn pronunciation of the (English) words accurately.

5. Discussion

In this section we discuss the results of the present study in relation to the research questions we addressed and, more generally, to those of previous research. The websites ILI and NOVO provide personalized pronunciation training and spoken vocabulary learning with automatic feedback. Practicing speaking with a computer that can ‘listen’ and provide feedback can help students build their confidence and reduce their speaking anxiety (Bashori et al., Citation2021). We adjusted these websites to the cultural context of the students in Indonesia, as can be seen from the selection of the learning topic used for the web-experiment. We also contextualized our study by conducting an experiment in a school’s computer laboratory supported by stable internet connectivity. Additionally, the websites seem to afford meaningful human-computer interaction that might in turn contribute to increasing socialization. Most of the students looked very excited to practice speaking with computers and were eager to share their experiences with their classmates. They were enthusiastic about using the speaking features on the websites. This is congruent with findings that examine the criteria to define so-called ‘Smart-CALL systems’ such as personalization and contextualization (Colpaert, Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2020).

5.1. First RQ: to what extent do ILI and NOVO positively affect students’ receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge?

The results presented above showed that the students in the two treatment groups (ILI and NOVO) significantly improved their receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge. It is important to note that the students in the control group also improved their vocabulary knowledge, but their improvement is not as significant as those in the treatment groups. In all three parts of the vocabulary test, the ILI and NOVO groups had higher gain scores than those of the control group. Part 1 (receptive) seemed to be easier than Part 2 (receptive). We argued that this might be because in Part 2, the students were provided with more alternatives (as distractors) than in Part 1, which probably made the students more confused. Part 3 (productive; written) seemed to be the most difficult one, which was to be expected (Pignot-Shahov, Citation2012). These findings suggest that it is important for learners and teachers to be able to distinguish receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge. Having a sufficient understanding on this matter will possibly help learners and teachers find or create an effective vocabulary learning (and teaching) method. Additionally, it seems that easier or more difficult words are often associated with their Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) level and Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) word frequency (https://www.english-corpora.org/coca/).

Interestingly, only in Part 3 of the vocabulary test, did the ILI group differ from the NOVO and control groups. The reason might be that the students in the ILI group had a higher proficiency level of English compared to the other participating groups, so that perhaps they could better acquire or retain vocabulary. This finding is congruent with the studies by Tekmen and Daloǧlu (Citation2006) and Golkar and Yamini (Citation2007). To check this, we employed a one-way ANOVA to investigate the relationship between the Anglia proficiency scores and the pre- and post-test scores in Part 3. The findings showed that there was a significant effect of the proficiency scores on the vocabulary pre- and post-test scores.

Looking at the higher gain scores in Part 1 and 2 compared to the results of Part 3, we suggest that more ASR-based training with a longer duration of the activities be provided to the students. The reason is that it is generally assumed that learners develop their receptive vocabulary before their productive vocabulary (Pignot-Shahov, Citation2012). To build the productive knowledge necessary for successful communication, a large receptive vocabulary is required (Milton, Citation2009). Therefore, having a longer interaction with ASR-based language learning systems might help learners turn their receptive vocabulary into productive vocabulary. In addition, writing down the words (e.g. after having oral practice) might help the students memorize and retain the vocabulary better. Studies show that writing tasks promote vocabulary acquisition (Dubiner, Citation2017; Pichette et al., Citation2012; Webb & Piasecki, Citation2018; Zou, Citation2017).

5.2. Second RQ: to what extent do ILI and NOVO positively impact students’ pronunciation?

The results of the pronunciation pre- and post-tests revealed that the students who received the web-treatment (ILI or NOVO) significantly improved their English pronunciation skills and outperformed the students in the control group. It is interesting to note that the students in the control group did not show any progress or improvement in their pronunciation, while in the vocabulary test, they did. We argued that the students in the control group only had a little individual, oral practice time in their regular classroom, especially on pronunciation. These results confirm our expectations about the positive effects of ASR-based websites as a language learning tool in the classroom in Indonesia. However, the number of students that took part in the pronunciation test was small (n = 24); eight students from each group (control, ILI, and NOVO). Through these websites every student can have access to ‘standard’ or native-like pronunciation, which is sometimes better and clearer than their teachers’ pronunciation. Additionally, due to the large classroom size, students on the back row in the traditional classroom might have difficulties in hearing/perceiving what teachers say. Besides, giving feedback on students’ pronunciation one by one within the allotted time is not possible for teachers.

Both websites appeared clearly to help address two crucial pronunciation problems faced by Indonesian EFL learners. First, the spelling of English words does not match the pronunciation (Swan & Smith, Citation2001), while Indonesian words are usually spelt the way they are pronounced. Second, there are some vowels and consonants in English that do not exist in Indonesian (Swan & Smith, Citation2001). For example, for ILI, one of the noticeable achievements was that the students changed the way they initially pronounced the word hijack as/hɪ.dʒek/in the pre-test into/ˈhaɪ.dʒaek/in the post-test, although the vowel/ae/was still a little bit off since this vowel does not exist in the Indonesian language system. Kosasih (Citation2017) reported that the vowel/ae/is one of the phonemes that trigger pronunciation problems in Indonesian EFL learners. For NOVO, the students at the beginning pronounced the word ‘ragged’ incorrectly in several different ways, but after using NOVO, they changed the way they pronounced this word into the near-correct pronunciation;/ˈraeɡ.ɪd/. However, there was still a problem with the/-ed/ending since in the Indonesian language system, words that end in/-d/are usually pronounced as/t/and are not emphasized. In English, words that end in/-ed/may be pronounced with one of three different final sounds;/t/,/d/, or/ɪd/(sometimes/əd/). This difficulty is congruent with Dewi’s (Citation2009) study, which mentioned that the Indonesian students’ ability in pronouncing/-ed/ending is still unsatisfactory. The study also explicitly stated that ragged is one of the problematic/-ed/ending words.

In the case of the pronunciation of tense or long vowels in English, which do not exist in Indonesian, such as in the words beach/biːtʃ/, sea/siː/, and crew/kruː/, the majority of the students did not pronounce these words with the appropriate, long duration and seemed to pronounce beach as/bɪtʃ/, with a shorter/i/. This can be troublesome and may be considered offensive. Additionally, word stress is also problematic for the students. Results from two expert judgments imply that word stress should receive more attention by the students as this feature is considered important in pronunciation. We argued that having correct word stress might lead to a greater and better intelligibility. These issues are in line with the findings in Andy et al. (Citation2020) study, which mentions that lack of knowledge on features such as nuclear stress and vowel length makes Indonesian Accented English (IAE) unintelligible. Moreover, as pronunciation brings social meaning, those who pronounce the FL words with near-native pronunciation might be considered more educated and culturally blended with the community that ‘owns’ the language.

Additionally, it is possible that the Indonesian experts involved in this study might have been aware of the above phenomena, but chose to ignore them when giving their judgments. Possibly, they took into consideration the linguistic background of the participants and might have thought that in a real conversation with a clear context, the quality of the tense vowels or word stress would not be very important. Overall, this clearly shows a native language interference on the students’ English pronunciation. Furthermore, recently there have been studies that discuss the emergence of Indonesian English (Dewi, Citation2015) and Indonesian Accented English (Andy et al., Citation2020; Waloyo & Jarum, Citation2019). This might suggest a gradual subtle shift from native speaker-oriented or ‘native-speakerism’ to supporting intelligibility in the Indonesian context.

As English has evolved as world Englishes, we argued that Indonesian learners of English might not need to fully adapt their English to the so-called ‘native-like’ model, especially with regard to pronunciation. It is still important, however, to have a native-speaker model in teaching and learning pronunciation, but the ultimate goal should not focus too much on being native-like. This issue is especially sensitive in the Indonesian context where English is often assumed to be the representative of ‘the West’, as Gunarwan (Citation1993) as cited in Dewi (Citation2017) claimed that English has led Indonesians to become ‘imitative of the British or the Americans’. Additionally, the notion of intelligibility in FL learning and teaching has drawn more attention from scholars around the world (e.g. Levis, Citation2005; Munro & Derwing, Citation1999, Citation2015, Citation2020). Given that speech can be heavily accented, but still highly intelligible, pronunciation researchers advocate that intelligibility be prioritized above nativeness. This implies that, in the Indonesian context, learners should not worry too much about their local accents (e.g. Javanese, Balinese, Madurese, Sundanese) when speaking English. As long as learners’ speech is intelligible (clear enough to be understood) – although the speech might not be considered to be near-native, there should not be a problem with communication in the target language. It is important to note that pronunciation is the aspect that deserves more attention in the Indonesian context because the current results are promising, but the study was too limited in this respect.

5.3. Limitations and future implications

One of the limitations of this study is that there was a huge gender imbalance between boys (n = 222) and girls (n = 10). This was due to the school’s study programs which are mostly chosen by boys. Another limitation is that some audio files were of low quality because of background noise (people talking, song playing, etc.). The first author manually recorded the students’ pronunciation using a smartphone. This situation makes the speech analyses even more challenging.

This study indicates that ASR-based websites could be useful to EFL education in Indonesia. However, the presence of this technology should not replace teachers in the classroom. Teachers are supposed to be the main learning designers and facilitators to help learners to make the most of ASR-based language learning systems. Higgins et al. (Citation2007) study implies that no matter how great technologies are, if teachers do not possess good pedagogical skills, technologies will be such a waste. Moreover, with the characteristics of today’s learners as iGeneration or Generation Z (González-Lloret & Ortega, Citation2014), learning environments supported by relevant technology are likely to be more interesting, promising, and favorable for language learners in the future.

6. Conclusions and future perspectives

The present classroom experiment has shed some light on the effects of two ASR-based language learning systems, I Love Indonesia (ILI) and NovoLearning (NOVO), upon Indonesian students’ receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge and pronunciation skills. ILI and NOVO successfully helped secondary school students in Indonesia enhance their knowledge of the targeted vocabulary and pronunciation skills. Both websites provide different types of feedback on students’ oral practice, but the differences between these websites appear not to be significant. The interview results show that the students and teachers perceived the websites positively.

Future studies should consider including a larger sample size with a better gender balance when investigating the effects of ASR-based language learning systems on learners’ pronunciation skills. Pronunciation descriptors and examiner/expert guidelines should be modified to acknowledge learners’ unique features that might be unproblematic for intelligibility, for instance, the typical English/r/versus the typical Indonesian rolling/r/. It is also interesting to design experiments that compare and examine groups who receive ASR feedback alone and those supported with ASR plus peer feedback. In addition, delving into learners’ log files stored in personalized ASR-based language learning systems may help elucidate learners’ actual engagement or participation rate, their linguistic development within a specified time period, and their learning trajectory.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the students and teachers who participated in this research for their cooperation and NovoLearning for their valuable supports.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Muzakki Bashori

Muzakki Bashori is a Ph.D. candidate at the Centre for Language Studies of the Radboud University Nijmegen. His research interests include automatic speech recognition technology for EFL learning, emotions in EFL classrooms, and the use of folklore as EFL teaching materials. E-mail address: [email protected] or [email protected].

Roeland van Hout

Roeland van Hout is an emeritus professor in applied linguistics and variationist linguistics at the Centre for Language Studies of the Radboud University Nijmegen. He publishes in the fields of sociolinguistics, dialectology and second language acquisition and has a special interest in research methodology and statistics. E-mail address: [email protected].

Helmer Strik

Helmer Strik is an associate professor at the Centre for Language Studies of the Radboud University Nijmegen. His fields of expertise include computer-assisted language learning (CALL), phonetics, speech production, speech processing, automatic speech recognition (ASR), spoken dialogue systems, e-learning, and e-health. E-mail address: [email protected].

Catia Cucchiarini

Catia Cucchiarini is a senior researcher at the Centre for Language Studies of the Radboud University Nijmegen. Her research activities address speech processing, computer assisted language learning (CALL), and the application of automatic speech recognition (ASR) to language learning and testing. E-mail address: [email protected].

References

- Andy, Muzammil, L., & Muhaji, U. (2020). Intelligibility and Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) in Indonesian Accented English (IAE) [PowerPoint Slides]. The 4th International Conference on Language, Literature, Culture, and Education, Fakultas Pendidikan Bahasa Dan Sastra Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia (FPBS UPI). http://icollite.event.upi.edu/file/ppt/PPT_ICOLLITE-Andy,_Lasim,_Uun.pdf

- Ariatna. (2016). The need for maintaining CLT in Indonesia. TESOL Journal, 7(4), 800–822.

- Bailey, D. J., Speights Atkins, M., Mishra, I., Li, S., Luan, Y., & Seals, C. (2021). An automated tool for comparing phonetic transcriptions. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2021.1896783

- Bashori, M., van Hout, R., Strik, H., & Cucchiarini, C. (2020). Web-based language learning and speaking anxiety. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1770293

- Bashori, M., van Hout, R., Strik, H., & Cucchiarini, C. (2021). Effects of ASR-based websites on EFL learners’ vocabulary, speaking anxiety, and language enjoyment. System, 99, 102496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102496

- BPS (Badan Pusat Statistik) [Indonesian Statistics Agency]. (2011). Kewarganegaraan, suku bangsa, agama dan bahasa sehari-hari penduduk Indonesia: Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010. [Citizenship, ethnicity, religion, and daily languages of Indonesian: The result of demography census 2010]. Badan Pusat Statistik.

- Brown, G., & Yule, G. (1983). Teaching the spoken language. Cambridge University Press.

- Chen, H. H. J. (2016, October). Developing a speaking practice website by using automatic speech recognition technology. In International Symposium on Emerging Technologies for Education (pp. 671–676). Springer.

- Chevalier, S. (2007). Speech interaction with Saybot: A CALL software to help Chinese learners of English. Proceedings of the SLaTE-2007 Workshop (pp. 37–40).

- Colpaert, J. (2018a). Exploration of affordances of open data for language learning and teaching. Journal of Technology and Chinese Language Teaching, 9(1), 1–14.

- Colpaert, J. (2018b). Transdisciplinarity revisited. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(1–2), 483–489. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1437111

- Colpaert, J. (2020). Editorial position paper: How virtual is your research? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(7), 653–664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1824059

- Cucchiarini, C., Nejjari, W., & Strik, H. (2012). My Pronunciation Coach: Improving English pronunciation with an automatic coach that listens. Language Learning in Higher Education, 1(2), 365–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/cercles-2011-0024

- Cucchiarini, C., Neri, A., & Strik, H. (2009). Oral proficiency training in Dutch L2: The contribution of ASR-based corrective feedback. Speech Communication, 51(10), 853–863. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2009.03.003

- Cucchiarini, C., & Strik, H. (2019). Second language learners’ spoken discourse: Practice and corrective feedback through automatic speech recognition. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Computer-assisted language learning: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications (pp. 787–810). IGI Global.

- Daniels, P., & Iwago, K. (2017). The suitability of cloud-based speech recognition engines for language learning. JALT CALL Journal, 13(3), 229–239.

- Derwing, T. M., & Rossiter, M. J. (2002). ESL learners’ perceptions of their pronunciation needs and strategies. System, 30(2), 155–166.

- Dewi, A. (2015). Perception of English: A study of staff and students at universities in Yogyakarta. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Dewi, A. (2017). The English (es) to teach after study and life in Australia: A study of Indonesian English language educators. Asian Englishes, 19(2), 128–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13488678.2017.1279762

- Dewi, A. K. (2009). Pronunciation problems faced by the English Department Students in Pronouncing–ed ending (A Case of the Sixth Semester Students of the English Department of Unnes in the Academic Year of 2008/2009) [Thesis]. Universitas Negeri Semarang.

- Dodigovic, M. (2005). Vocabulary profiling with electronic corpora: A case study in computer assisted needs analysis. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 18(5), 443–455. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220500442806

- Dodigovic, M., & Agustín-Llach, M. P. (2020). Introduction to vocabulary-based needs analysis. In Vocabulary in curriculum planning (pp. 1–6). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dubiner, D. (2017). Using vocabulary notebooks for vocabulary acquisition and teaching. ELT Journal, 71(4), 456–466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccx008

- Eskenazi, M., Kennedy, A., Ketchum, C., Olszewski, R., Pelton, G. (2007). Carnegie speech native accent the native accenttm pronunciation tutor: Measuring success in the real world. Proceedings of the SLaTE-2007 Workshop.

- Evanini, K., Timpe-Laughlin, V., Tsuprun, E., Blood, I., Lee, J., Bruno, J., … Suendermann-Oeft, D. (2018). Game-based spoken dialog language learning applications for young students. Proceedings from the 2018 Interspeech Conference (pp. 548–549). https://www.isca-speech.org/archive/Interspeech_2018/pdfs/3045.pdf

- Fakhrunnisa. (2015). Indonesian-Javanese students’ pronunciation of English monophthongs [Thesis]. State Islamic University Sunan Kalijaga.

- Franco, H., Bratt, H., Rossier, R., Rao Gadde, V., Shriberg, E., Abrash, V., & Precoda, K. (2010). EduSpeak®: A speech recognition and pronunciation scoring toolkit for computer-aided language learning applications. Language Testing, 27(3), 401–418. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532210364408

- Goh, C. C. M., & Burns, A. (2012). Teaching speaking: A holistic approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Golkar, M., & Yamini, M. (2007). Vocabulary, proficiency and reading comprehension. The Reading Matrix, 7(3), 88–112.

- Golonka, E. M., Bowles, A. R., Frank, V. M., Richardson, D. L., & Freynik, S. (2014). Technologies for foreign language learning: A review of technology types and their effectiveness. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 27(1), 70–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.700315

- González-Lloret, M., & Ortega, L. (Eds.). (2014). Technology-mediated TBLT: Researching technology and tasks (Vol. 6). John Benjamins Publishing Company.

- Gunarwan, A. (1993). Bahasa asing sebagai kendala pembinaan Bahasa Indonesia [Foreign languages as constraints in the development of the Indonesian Language]. Paper presented at the Kongres Bahasa Indonesia VI, Jakarta.

- Herman. (2016). Students’ difficulties in pronouncing the English labiodental sounds. Communication and Linguistics Studies, 2(1), 1–5.

- Higgins, S., Beauchamp, G., & Miller, D. (2007). Reviewing the literature on interactive whiteboards. Learning, Media and Technology, 32(3), 213–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17439880701511040

- Kosasih, M. M. (2017). Native language interference in learning English pronunciation: A case study at a private university in West Java, Indonesia. International Journal of Education and Research, 5(2), 135–150.

- Laufer, B. (1998). The development of passive and active vocabulary in a second language: Same or different? Applied Linguistics, 19(2), 255–271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/19.2.255

- Laufer, B., & Nation, P. (1995). Vocabulary size and use: Lexical richness in L2 written production. Applied Linguistics, 16(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/16.3.307

- Levis, J. M. (2005). Changing contexts and shifting paradigms in pronunciation teaching. TESOL Quarterly, 39(3), 369–377. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3588485

- Ma, Q., & Kelly, P. (2006). Computer assisted vocabulary learning: Design and evaluation. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 19(1), 15–45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220600803998

- McAndrews, M. (2020). Prosody instruction for ESL listening comprehension [Ph.D. dissertation]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Northern Arizona University.

- McCrocklin, S. M. (2016). Pronunciation learner autonomy: The potential of automatic speech recognition. System, 57, 25–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.12.013

- McCrocklin, S., Humaidan, A., Edalatishams, E. (2019). ASR dictation program accuracy: Have current programs improved. In Proceedings of the 10th Pronunciation in Second Language Learning and Teaching Conference (pp. 191–200).

- Milton, J. (2009). Measuring second language vocabulary acquisition. Multilingual Matters.

- Morley, J. (1991). The pronunciation component in teaching English to speakers of other languages. TESOL Quarterly, 25(3), 481–520. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3586981

- Morton, H., Gunson, N., & Jack, M. A. (2012). Interactive language learning through speech enabled virtual scenarios. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, 2012, 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/389523

- Morton, H., & Jack, M. (2010). Speech interactive computer-assisted language learning: A cross-cultural evaluation. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(4), 295–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2010.493524

- Mroz, A. P. (2018). Noticing gaps in intelligibility through Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR): Impact on accuracy and proficiency. Paper Presented at 2018 Computer-Assisted Language Instruction Consortium (CALICO) Conference, Urbana, IL, United States.

- Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (1999). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning, 49(1), 285–310. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0023-8333.49.s1.8

- Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (2015). Intelligibility in research and practice: teaching priorities. In M. Reed, & J. M. Levis (Eds.), The handbook of English pronunciation (pp. 377–396). Wiley.

- Munro, M. J., & Derwing, T. M. (2020). Foreign accent, comprehensibility and intelligibility, redux. Journal of Second Language Pronunciation, 6(3), 283–309. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/jslp.20038.mun

- Nation, I. S (1990). Teaching and learning vocabulary. Newbury House.

- Neri, A., Mich, O., Gerosa, M., & Giuliani, D. (2008). The effectiveness of computer assisted pronunciation training for foreign language learning by children. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 21(5), 393–408. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220802447651

- NovoLearning. (2019). Improving English Language Proficiency using Novo’s Mobile Learning Solution: A pilot project. https://www.novo-learning.com/assets/pdf/research-report.pdf

- Offerman, H. M., & Olson, D. J. (2016). Visual feedback and second language segmental production: The generalizability of pronunciation gains. System, 59, 45–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.03.003

- Penning de Vries, B. W., Cucchiarini, C., Strik, H., & Van Hout, R. (2020). Spoken grammar practice in CALL: The effect of corrective feedback and education level in adult L2 learning. Language Teaching Research, 24(5), 714–735. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818819027

- Pichette, F., De Serres, L., & Lafontaine, M. (2012). Sentence reading and writing for second language vocabulary acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 33(1), 66–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amr037

- Pignot-Shahov, V. (2012). Measuring L2 receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge. Language Studies Working Papers, 4(1), 37–45.

- Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (2017). Ethnologue: Languages of Indonesia (20th ed.) SIL International.

- Swan, M., & Smith, B. (2001). Learner English. A teacher’s guide to interference and other problems (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Tejedor-García, C., Cardeñoso-Payo, V., & Escudero-Mancebo, D. (2021). Automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems applied to pronunciation assessment of L2 Spanish for Japanese speakers. Applied Sciences, 11(15), 6695. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/app11156695

- Tekmen, E. A. F., & Daloǧlu, A. (2006). An investigation of incidental vocabulary acquisition in relation to learner proficiency level and word frequency. Foreign Language Annals, 39(2), 220–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2006.tb02263.x

- Thornbury, S. (2002). How to teach vocabulary. Longman.

- Timpe-Laughlin, V., Sydorenko, T., & Daurio, P. (2020). Using spoken dialogue technology for L2 speaking practice: What do teachers think? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1774904

- Uchihara, T., & Clenton, J. (2020). Investigating the role of vocabulary size in second language speaking ability. Language Teaching Research, 24(4), 540–556. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818799371

- Uchihara, T., & Saito, K. (2019). Exploring the relationship between productive vocabulary knowledge and second language oral ability. The Language Learning Journal, 47(1), 64–75.

- van Doremalen, J., Boves, L., Colpaert, J., Cucchiarini, C., & Strik, H. (2016). Evaluating automatic speech recognition-based language learning systems: A case study. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(4), 833–851. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2016.1167090

- Wahyuningsih, S., & Afandi, M. (2020). Investigating English speaking problems: Implications for speaking curriculum development in Indonesia. European Journal of Educational Research, 9(3), 967–977. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.9.3.967

- Waloyo, A. A., & Jarum, J. (2019). The Indonesian EFL students’attitudes toward their L1-accented English. Erudio (Journal of Educational Innovation), 6(2), 181–191.

- Webb, S., & Piasecki, A. (2018). Re-examining the effects of word writing on vocabulary learning. ITL-International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 169(1), 72–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1075/itl.00007.web

- Yenkimaleki, M., & van Heuven, V. J. (2019). The relative contribution of computer assisted prosody training vs. instructor based prosody teaching in developing speaking skills by interpreter trainees: An experimental study. Speech Communication, 107, 48–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.specom.2019.01.006

- Yenkimaleki, M., van Heuven, V. J., & Moradimokhles, H. (2021). The effect of prosody instruction in developing listening comprehension skills by interpreter trainees: Does methodology matter? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–37. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1957942

- Zein, S. (2019). English, multilingualism and globalisation in Indonesia. English Today, 35(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S026607841800010X

- Zein, S., Sukyadi, D., Hamied, F. A., & Lengkanawati, N. S. (2020). English language education in Indonesia: A review of research (2011–2019). Language Teaching, 53(4), 491–523. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444820000208

- Zou, D. (2017). Vocabulary acquisition through cloze exercises, sentence-writing and composition-writing: Extending the evaluation component of the involvement load hypothesis. Language Teaching Research, 21(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168816652418

Appendix A

Targeted Vocabulary

There were 40 targeted words in total, as shown in , taken from the text of Malin Kundang, a narrative from the traditional Indonesian folklore from West Sumatra.

Table A1. List of targeted vocabulary items.

Noun (n = 14)

Verb (n = 11)

Adjective (n = 10)

Adverb (n = 5)

Appendix B

Below are the samples of the vocabulary test items.

Part 1

Choose one correct meaning from the four choices for each given word.

1. Village

a. Desa b. Kota c. Hutan d. Sawah

2. Curse

a. Memukul b. Mengutuk c. Menampar d. Meninggalkan

Part 2

Match the words with their correct Indonesian translations.

Part 3

Please fill in the gaps with the suitable words for the contexts. The initial letter(s) and the Indonesian translations for each missing word have been given.

1. Malin Kundang and his mother lived in a small and quite (v_____). Desa

2. Malin Kundang’s mother said, ‘I (c_____) you to turn to stone’. Mengutuk

Table 1. Research steps, the instruments, and the participants.

Table 2. Summary of the main results including the values of Cronbach’s alpha, F, p and/or R2.