Abstract

This study is situated in the context of a design-driven master’s-level course at a Finnish university where pre-service teachers (PSTs) planned and carried out an online English learning project for 11- to 12-year-old pupils in two schools. During the working process, the PSTs needed to rethink their perceptions of technology-mediated language education and look for new ways to organise pedagogical activities for the children. The study explores how the PSTs’ professional vision and agency emerged in a hybrid space when orchestrating pupils’ participation online. Diverse materials from orchestration sessions were examined through nexus analysis. The findings highlight the PSTs’ professional vision and agency arising from interactions with the following activities while orchestrating language learning: 1) coordinating action and establishing continuity in design; 2) monitoring action and attending to emerging needs; and 3) attending to pupils’ engagement with the designed activities and revising the design during action if necessary. The setting allowed collaborative problem solving and sense making which advanced a balanced interaction order. This made space for new experiences and discourses contributing to the development of the PSTs’ professional vision as language teachers. The study has implications for language teacher education and language teaching in hybrid spaces.

1. Introduction

Despite the increasing use of technologies in everyday interaction, there are still challenges in integrating the pedagogical use of technologies in language education and language teacher education (Karamifar et al., Citation2019). The digital backgrounds of in-service teachers are diverse (Stickler et al., Citation2020), and few teachers had experience of online language teaching before the Covid-19 pandemic (Moser et al., Citation2021). Research on emergency remote teaching during the Covid-19 pandemic has further highlighted the need for addressing the pedagogical use of technologies in language teacher education (e.g. Harsch et al., Citation2021; Moser et al., Citation2021), and the importance of promoting teacher agency to act in changing environments (Ashton, Citation2022).

More research is called for from the perspectives of pedagogy, design, and teacher education (Gillespie, Citation2020; Levy et al., Citation2015). Studies related to technology-mediated language education have focused on the language learner, while less attention has been paid to the interaction between teachers and/or pre-service teachers (PSTs) who administer online language learning with the pupils physically in another space (Sun, Citation2017). During their studies in language teacher education, PSTs become gradually apprenticed to the practices of professionals in the formal settings of teacher education and other arenas of life as they approach their future careers (Buchanan, Citation2015; Voogt et al., Citation2015). Once graduated, they join the ranks of teachers overseeing the practical organisation of language learning in terms of pedagogical approaches and the tools used, thus having an impact on the future of the use of technologies in language education (Hubbard, Citation2008). If teacher education only focuses on what is currently available, the technology may be outdated due to rapid digitalisation when the PSTs graduate. Therefore, envisioning the future is essential for PSTs to be able to navigate the educational field as future professionals. Such envisioning can be promoted through design-driven approaches that involve PSTs to become designers of language learning in brainstorming, planning, producing, and executing language projects for real participants (Kuure et al., Citation2016). Design-driven work also provides opportunities for making uncertainties, decision making and problem solving accessible for participants to reflect upon (Laurillard, Citation2012; Tumelius & Kuure, Citation2021).

The current study aims to develop language teacher education by providing insight into how PSTs are prepared to guide language learning in spaces characterised by hybridity, i.e. the merging of the physical and digital, involving constant intertwining of multiple practices (Ryberg et al., Citation2018). It is not just a matter of transferring classroom-based approaches to digital environments as such. Rather, it requires a new way of thinking which emerges from participants’ sensemaking of theoretical issues and practical solutions (Buchanan, Citation2015; Golombek & Johnson, Citation2017). We will be using the term professional vision for a deepening understanding of what language learning and teaching in hybrid environments involves and what it means for pedagogical practice. This also involves agency for pedagogical decisions and actions (Barahona, Citation2020; Edwards, Citation2007; Meskill et al., Citation2020; Schön, Citation1987).

This research is part of a long-term venture exploring Finnish PSTs becoming language teachers in a technology-rich world. In Finland, language teachers are required to hold a master’s degree with advanced language courses and specialist pedagogical studies. Typically, the curriculum provides no specific training in technology-mediated teaching. We examine a case where the pedagogical use of technologies was integrated into university degree studies of English in Finland. The research materials come from an elective master’s-level course for PSTs where the participants designed and orchestrated an online English learning project for pupils. Orchestration refers here to managing spatially, temporally, and socially distributed activities with respect to their wider pedagogical framework and technologies available (Blin & Jalkanen, Citation2014; Dillenbourg, Citation2008; Guichon, Citation2010; Ryberg et al., Citation2018; see Section 2.1).

The research draws on nexus analysis, a qualitative and participatory approach to situated action with discursive dimensions (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004; see also Norris, Citation2004). The concepts of interaction order, historical body and discourses in place are used here as theoretical lenses (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). The research question that the study aims to answer is how professional vision and agency of PSTs emerged in hybrid spaces when orchestrating pupils’ online participation. Video recordings selected from a wider archive of materials are in focus in the analysis.

2. Background to the study

2.1. Orchestrating language learning in hybrid spaces

Design-driven approaches in education have arisen in recent years although they have not been widely applied yet in language teacher education. Designing and testing learning scenarios and activities in real-life situations with learners online enables PSTs to explore and question diverse aspects of language learning and being teachers (Anderson & Shattuck, Citation2012; Booth et al., Citation2017; Tumelius & Kuure, Citation2021). As pedagogical designs are developed gradually in collaboration with others through ideation, planning, content production, experimentation and evaluation, the work requires attending to a diversity of tasks and management of uncertainty (Kuure et al., Citation2016), The metaphor of orchestration has been used to illustrate the situated management of spatially, temporally, and socially distributed activities (Dillenbourg, Citation2008; Ryberg et al., Citation2018). In connection with pedagogical design, orchestration also involves configuring the relevance of situated needs with the wider pedagogical framework and the technologies available (Blin & Jalkanen, Citation2014; Dillenbourg, Citation2008; Guichon, Citation2010). Teachers as orchestrators of educational activities need to be prepared for the emergence of unexpected situations, which may require restructuring the ongoing pedagogical scenario and being sensitive to long-term developments and change (Dillenbourg, Citation2008; Guichon, Citation2010; Hubbard, Citation2019; Knight et al., Citation2020).

Situations where online language learning is orchestrated also require sensitivity to hybrid space, which Pischetola (Citation2022) defines as emerging from a socio-material assemblage characterised by ‘the blurring of boundaries between physical and virtual spaces, private and public spaces, personal and professional life and embodied and rational experiences’ (p. 71). Hybridity manifests itself when people manage multiple overlapping layers of time, space, and mediated action by switching their orientations, thus contributing to the emergence of sites of engagement (Jones, Citation2005). When engaged in design work, teachers and PSTs are interactionally creating their personal learning spaces, reaching new horizons of possibilities for their pedagogical practices that they may not have envisioned earlier (Blin & Jalkanen, Citation2014). The teaching profession has even been reconceptualised as a design science in which teachers have agency to become creators of new knowledge about teaching and learning in changing environments, being able to critically evaluate the appropriation of technologies for pedagogical purposes (Laurillard, Citation2012).

2.2. Language teachers’ professional vision and agency in a technology-rich world

The deepening understanding of what language learning and teaching in hybrid environments involves and what it means for pedagogical practice can be characterised as growing a professional vision. The term comes from Goodwin (Citation1994), whose definition focuses on how members of a profession use discursive practices to shape events in their disciplinary domain creating objects of knowledge such as theories and artifacts that distinguish it from other professions. Goodwin’s (Citation1994) work is based on the study of interaction in situ, but other researchers have extended the concept also to educators’ knowledge, practice, and pedagogical actions (Meskill et al., Citation2020; Stürmer et al., Citation2013). An important aspect of the growing professional vision of PSTs is how they assume responsibility for pedagogical decisions and actions (Barahona, Citation2020).

Professional vision is here understood to also involve professional agency, which is nurtured by exploring the relationship between theory and practice, and past and current experiences, and by envisioning the future (Barahona, Citation2020; Booth et al., Citation2017; Hammerness, Citation2008; Lindroth, Citation2015). Agency, referring to the socially mediated capacity to act (Ahearn, 2001), is incorporated in the professional vision as the ability to perceive possibilities and act according to emerging understandings in situationally relevant ways (van Lier, Citation2007). Language teacher agency has been theorised as relational, social, and collective by nature (Kayi-Aydar et al., Citation2019; Tao & Gao, Citation2021). Thus, the sense of agency can be promoted in collaborative action (Tao & Gao, Citation2021).

Importantly, PSTs need to gain hands-on practice and deepen their understanding related to designing and orchestrating language learning in hybrid spaces. They also need experience of design-driven approaches to explore and experiment with the pedagogical use of a broadening range of technologies in real-life teaching situations (Anderson & Shattuck, Citation2012; Booth et al., Citation2017; Tumelius & Kuure, Citation2021). This involves developing the relational side of their agency: the capacity to share experiences and expertise with others in situations which require fast decisions (Anderson & Shattuck, Citation2012; Edwards, Citation2007; Kubanyiova, Citation2020).

2.3. Language teacher education and practice as means to promote professional vision in multimodal interaction

Pedagogical approaches in language teacher education should allow PSTs the opportunity to develop their agency in becoming language teachers with expertise in technology-mediated language learning (Guichon & Wigham, Citation2016; Jeong, Citation2017). It has been suggested that future developments are not envisioned to a sufficient degree with PSTs (Colpaert & Gijsen, Citation2017; Karamifar et al., Citation2019). English foreign language teachers and teacher educators characterise ideal teachers as valuing innovation, creativity, adaptation, and open-mindedness, but they do not identify technology use as central to their professional expertise (Karamifar et al., Citation2019). As such beliefs may hinder innovation in the pedagogical use of technologies in education, language teachers, and PSTs need opportunities for collaboration in new technological configurations to strengthen their future orientation (Dooly, Citation2017; Dooly & Sadler, Citation2013; Karamifar et al., Citation2019).

Hands-on experience and practice are known to be fundamental in developing PSTs’ and in-service teachers’ professional vision to see situations more holistically and to act flexibly in rapidly changing situations (Pouta et al., Citation2020; Stickler et al., Citation2020). Teaching practice during pedagogical studies typically involves classroom-based language teaching, but fewer opportunities are provided for situated practice in hybrid environments, including designing and orchestrating language learning. Language teachers need expertise in the situated management of spatially, temporally, and socially distributed activities in the pedagogical context, especially in technology-mediated environments (Dillenbourg, Citation2008; Hindmarsh & Heath, Citation2007).

As Ensor et al. (Citation2017) point out, ‘teacher identity results from a complex interplay of institutional, professional, and informal discourses which may be both obstacles and bridges to pedagogical transformation’ (p. 1). In language teacher education which is design-driven, PSTs may be given space to adopt the perspective of a teacher (Ensor et al., Citation2017; Özverir et al., Citation2021; Tumelius & Kuure, Citation2021). PSTs may experience chaos and uncertainty in designing and orchestrating language learning with real participants but transform it to normalised practice by working with others and making sense multimodally (Koivistoinen et al., Citation2016). As changing perspectives from traditional to new ways of being teachers is challenging (e.g. Kuure et al., Citation2016; Tumelius & Kuure, Citation2021), PSTs need support in making sense of work in a technology-rich environment where their emotions, feelings, and reactions should not be neglected (Wang et al., Citation2010).

3. Research approach

3.1. Institutional setting and participants

The institutional setting for this study is an elective master’s-level course (5 ECTS)1 on language learning and technologies (LLT) in English studies at a Finnish university. In Finland, language teacher education is organised in 5-year-long master’s degree university studies (value 300 ECTS) which include pedagogical studies (60 ECTS). The curriculum for pedagogical studies does not highlight the use of technology as such but pedagogical expertise in general, and thus includes educational science, didactics, and school practice.

The aim of the LLT course was to familiarise the university students with sociocultural language pedagogy in a technology-rich world and provide hands-on experience in the pedagogical use of technologies by designing and carrying out a language learning project. The course provided opportunities for any student in English studies to explore the relationship between language pedagogy, technology, and language teaching as a career option. From the series of annually organised design-driven courses, one was chosen for this study. The collected research materials allow for a close inspection of orchestration and design (see Section 3.2). The chosen course implementation was led by one university lecturer and had 14 university students of English, 10 of whom were studying to become teachers (PSTs) and who comprised the research participants for the current study.

The first author was one of the PSTs, and the second author was the lecturer in charge of the course. Both contributed equally to the research including the writing process.

3.2. Research materials

Research materials were accumulated and gathered during the LLT course and the project () following the principles of triangulation (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). The nexus-analytical research approach involves examining situated data in its wider context. Therefore, the whole body of research materials is relevant although the focus will be on the video recorded sessions organised for synchronous online activities. These sessions were fruitful events where negotiation and problem solving related to the events at hand as well as multimodal aspects of orchestration among the PSTs and lecturer were on display for research. Therefore, the video footage from the sessions (ca. 12 hours from 10 sessions) and materials from the school project workspace were central materials in analysis.

Table 1. Research materials.

The research complies with the national ethical guidelines for research integrity as well as data privacy and protection (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity, Citation2019; Finnish Social Science Data Archive, 2022). The Ethics Committee of Human Sciences of University of Oulu has waived the ethical review because it is required neither by Finnish legislation nor by the criteria set by the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. The participants’ rights in this study were explained to the PSTs after which they filled out and signed the informed consent forms. A research permit was acquired from the participating schools, and the schoolteachers, pupils, and pupils’ legal guardians also filled out and signed the informed consent forms. The consent involved agreement to participation, data collection, treatment of personal information, data processing, and the publication of anonymised data.

3.3. The design-driven approach of the university course

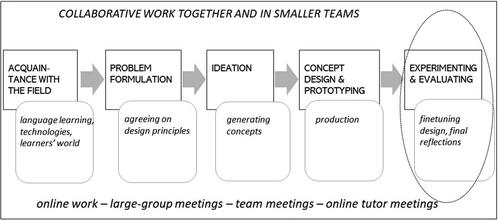

Design processes have been described with some variation in the field of language education due to different design goals and contexts (Özverir et al., Citation2021). The flow of the LLT course was the following (see ).

During the LLT course, the PSTs designed and implemented an online English learning project for 25 fifth graders (11- to 12-year-olds) from two Finnish schools. The lecturer led the course, but the PSTs were able to take the initiative in all aspects of the activities. The work was organised in different combinations of small groups and meetings with all course participants, both face-to-face and online. An online platform was used for documenting the work and sharing information between the PSTs and the lecturer.

The work proceeded from background research on LLT to problem formulation and ideation and the delineation of one concept for further development over a period of eight weeks. The PSTs produced a prototype (initial model) called Tech Town (marked by a circle in ). It was tested in a four-week school project with pupils. Afterwards, there was a wrap-up meeting, and the PSTs wrote their final reflections.

Tech Town involved a narrative of town life, which included both synchronous and asynchronous activities that the pupils could engage in flexibly. Several functions and tools available on the online platform and desktop conferencing system were used in the development, e.g. internal and external links, image maps, html and text pages, discussion lists, chats, images, and video files. Due to technical problems with video connection in one of the schools, the synchronous meetings were based on written online chats and discussion forums.

The PSTs had timetables from the schools indicating the lessons when the children would be linked to Tech Town for synchronous online activities such as quizzes in the chat or discussion forums for practice of asking and answering questions. The PSTs agreed on tutoring turns so that all had an opportunity to facilitate the children’s work in action at least once. During the synchronous activities, there were one to three PST’s online at the same time. Otherwise, the PSTs logged in on a regular basis to see what the children were doing outside the synchronous online activities. They also participated in the interactions where support was needed.

During the sessions for tutoring synchronous activities online, some PSTs came to the lecturer’s office while others were connected from their distant locations. The lecturer’s office was a practical choice as the office was only in the use of the lecturer and all the equipment needed, e.g. laptops and video cameras, could be stored there. For this study, the space provided access to studying collaboration and sense making in situ as the participants were interacting as colleagues despite their institutional role. illustrates the typical arrangement in the lecturer’s office where two PSTs are administering a quiz chat and facilitating pupils’ participation in Tech Town.

shows two camera angles in the office. Tuija (picture 1, left; picture 2, front) and Jenni (picture 1, right), are working on their laptops, and the lecturer Katri (picture 1, left front; picture 2, window corner) is working on her desktop computer (names are pseudonyms). During the tutoring sessions, the PSTs and the lecturer used a variety of tools and documents, thus bringing diverse material and digital spaces into foreground in their collaboration. During the sessions, the PSTs engaged in constant evaluation and adjustment of the designed activities—their meaningfulness for learners and usability.

3.4. Nexus analysis

The study draws on nexus analysis, which entails the view of social action as an intersection of three discourse cycles: historical body, interaction order, and discourses in place (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). Participants’ historical bodies emerge from individual histories, personal habits, understandings, and experiences (Nishida, Citation1958). Interaction order refers to mutual relationships between people (Goffman, Citation1971). Discourses in place emerge from various configurations of everyday interaction, language in use, as well as multimodal, wider-scale semiotic systems of practices (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). These concepts were used to answer the research question of how professional vision and agency of PSTs emerged in a hybrid space when orchestrating pupils’ online participation.

Nexus analysis proceeds through engaging, navigating, and changing the phenomenon in focus (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). Engaging includes data gathering and ethnographic observation (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004) as the researcher enters the community under study. In the current study, the researchers were among the key actors on the course as described in Section 3.1. During the navigation phase, the materials are explored using methodologies dependent on the research interest. Change characterises social action either as an overt goal or tacitly embedded in the social configurations between participants (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004).

The study started with a closer analysis of video data using other research materials such as interaction entries in the online working space and PSTs’ written reflections as additional resources (). Logs were created from the video footage and selected interactions were transcribed in more detail. Different visual techniques such as messy maps (Clarke, Citation2003), and modality graphs (Norris, Citation2004) were used to explore the research materials. The maps provided a deeper insight into design and orchestration but did not depict any final categorisations. The analysis is portrayed through representative examples from video recordings, with reference to the entire body of materials including the researchers’ observations and experiences ().

4. Findings

The analysis focuses on encounters in the lecturer’s office where the PSTs and the lecturer orchestrated synchronous online activities. The sessions provided interesting video data because the PSTs were able to discuss topics related to the activities and the pedagogical design that they would not have shared in pupils’ presence during the class. The setting gave us access to the participants’ sense making and reflections during the activities, which are important aspects of the development of professional vision and agency (Edwards, Citation2007; Goodwin, Citation1994; Schön, Citation1987).

The research process combined our participatory reflections, theoretical perspectives and data analysis, and revealed the orchestration of language learning as dealing with diverse intertwining actions as the PSTs focused on the emerging needs in situ with their connections to the overall design ().

Table 2. Orchestrating language learning in a hybrid space.

The aspects of orchestration illustrated in the table intertwine in action. They are discussed below from the perspective of professional vision and agency drawing on the theoretical lenses of interaction order, historical body, and discourses in place. We have analysed interaction from a multimodal perspective (e.g. Norris, Citation2004), and so, the examples include analysis of embodied action that is relevant for switching attention fluidly between digital and material spaces as well as for maintaining collaboration when orchestrating events. The findings are presented with representative examples chosen from one of the tutoring sessions with the typical set-up of two PSTs present in the lecturer’s office.

4.1. Coordinating action and establishing continuity

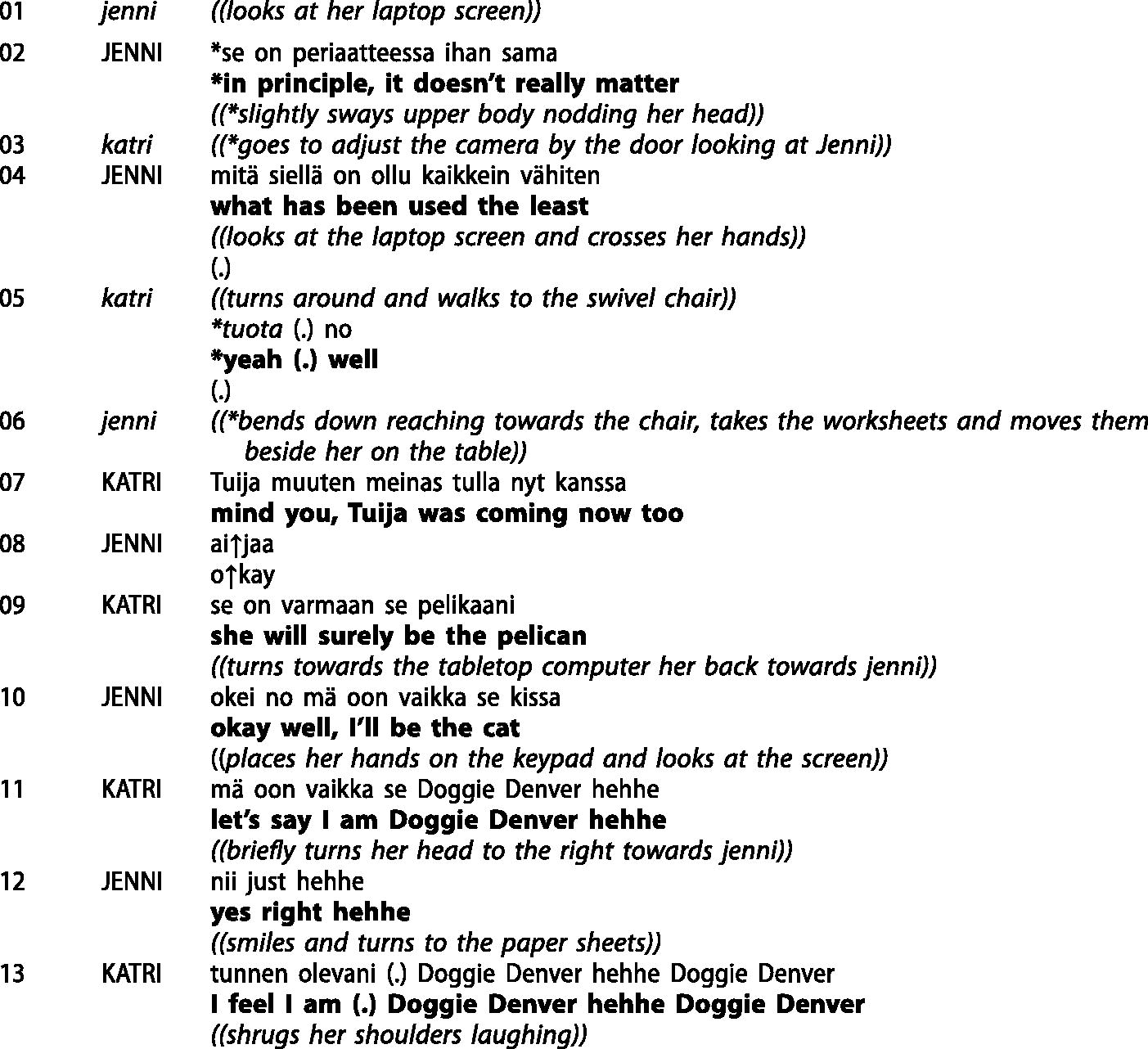

The orchestration of language learning involved different activities that contributed to the flow and continuity of the Tech Town learning project for the pupils. The participants coordinated their roles and responsibilities together, sometimes positioning themselves as designers and teachers, and sometimes as team partners or students on a university course. In Extract 1, Jenni and Tuija (PSTs) are taking their turns as online tutors in Katri’s (lecturer) office. The designed quiz activity at hand involves them playing animal characters. The extract starts after Katri has inquired about Jenni’s choice of animal character for the session which is about to begin. Italicised text indicates actions without verbalisation and the bold typeface is an English translation from the original Finnish. Transcript symbols drawing on Jefferson (Citation2004) are given in the Appendix.

(1) Coordinating tutor responsibilities (v8, 00:00–0:20)

As Jenni does not have a preference for an animal character (02), she replies to Katri’s question with another question about the overall situation concerning animal characters and their representation in Tech Town (04). She positions herself as a team member, but at the same time as responsible and committed to advancing the pedagogical scenario with the participating children. Without a direct answer, Katri shares her knowledge with Jenni about the other PST, Tuija, joining the session later (07). Katri’s statement and Jenni’s reply expressing positive assessment through prosodic emphasis (08 o↑kay) contribute to their balanced positioning in interaction and teamwork. Thus, the participants make the relational aspect of their professional agency visible as mutual support is given from the perspective of the shared goal (Edwards, Citation2007). The negotiation illustrated in the data example is resolved as Jenni chooses her animal character, which continues as a playful sequence when Katri acknowledges the joint resolution uttering her own animal character choice (11) jokingly via eager intonation, shoulder shrugging and laughter, establishing mutual rapport, and collegiality (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004).

A balanced interaction order was embedded in the pedagogical approach in general as the course was based on project work advancing through teamwork, but it was also established between the lecturer and the PSTs while configuring action in situ. This supported collaborative action for finetuning and timing activities and for negotiating meanings. Katri’s participation as one of the team members detached her from a traditional role of the teacher as someone who assigns the task, observes the students’ work from a distance and facilitates their work when needed. Based on our observations, it was an intentional choice for her to position herself as a co-participant, and the PSTs accommodated her stance without any visible problems. However, detaching from the traditional teacher–student relationship with the teacher being in charge is not straightforward, and among course-participants a tendency to assume the student position became sometimes apparent. For example, Jenni raised her concern to Katri about having been busy and perhaps needing to do more for the course. However, in the office sessions, the balanced interaction order was mostly apparent.

4.2. Monitoring action and attending to emerging needs

Various tools and documents in the office functioned as resources facilitating collaboration needed for monitoring action and attending to emerging needs. The applications on the screens served as entry points to various digital spaces, increasing the degree of hybridity that the PSTs needed to deal with (Goodwin, Citation1995; Ryberg et al., Citation2018).

The PSTs and the lecturer reached the pupils through the Tech Town online platform, a chat service, and the desktop videoconferencing system depending on the activities at hand. Contact was maintained with the teachers in the schools for organisational matters via mobile phones and an instant messenger. Various documents created for the learning project such as worksheets and the online course platform for the PSTs were utilised to advance the design, elaborate the activities in the spirit of the pedagogical approach, as well as finetune the design based on situated action with the pupils. The IT support services were contacted by landline to solve network issues. When using the occasionally slow browsers, university policies related to Internet access as well as the status of the technical infrastructure became foregrounded as discourse in place.

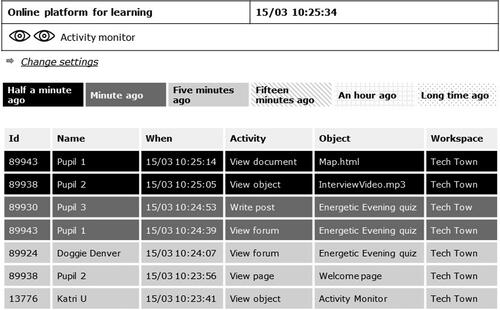

Tech Town was built on an online platform offered by the university. It became an essential hub for pupils’ activities, and therefore, a focal point for the PSTs, thus generating a hybrid space between the physically separate places. The activity monitor, one of the admin tools on the platform, emerged as an important feature throughout the whole project—it was used on a regular basis for monitoring pupils’ actions ().

The activity monitor shows the username (e.g. Pupil 1), the type of activity in question (e.g. View document), and the filename of the object being handled (e.g. Map.html). A timestamp gives the latest moment of access to the object. There is also a colour code giving a rough indication of the time flow (e.g. half a minute ago).

Katri gave all the course participants access to the activity monitor, which is not general practice on university courses. However, on this course, the PSTs were expected to use their full potential to design and guide activities for the pupils. By allowing and encouraging the PSTs to access the activity monitor, Katri assigned them some power, positioning them to assume agency and take on some professional responsibility (Barahona, Citation2020) as part of their learning of the practices involved in technology-mediated language teaching. This also reflected her attempts to establish a balanced interaction order, sharing work with the PSTs as equal team members.

While orchestrating online events, the PSTs and the lecturer used the activity monitor to anticipate the pupils’ actions online and speculate about what was happening in the classrooms. The information was utilised to evaluate the functionality of the pedagogical design and specific activities. During the session under analysis, the video materials show how Tuija sits quietly at the laptop monitoring the pupils’ actions online and then expresses some uncertainty about how the information from the activity monitor should be interpreted since there were unexpectedly few pupils online (there are no more than one, two, three [.] signed in or haven’t they just done anything). Katri joins Tuija to count the number of pupils’ usernames and they reach a shared understanding of the number. Tuija then presents a pedagogical assessment of a possible group configuration in the classroom (could it be so that they work like in pairs).

When the pupils are active in Tech Town, the activity monitor shows changes in the status of their work. Tuija renders her observation for others (now there is (.) <pupil name> writing a post), and comments on the benefit of using the tool (quite fun as one can see what everyone is doing). Jenni acknowledges Tuija’s turn with an affirmative ahmm. The PSTs’ assessments point to the activity monitor’s function as a resource for making guesses about what is going on in the classroom, and understanding what the overall orchestration of the online discussions involves. For the participants, the activity monitor opens new spaces for attention, which expands their professional vision as they need to interpret actions and interactions in converging hybrid spaces, and act accordingly.

Collaborative action in hybrid spaces is something that the PSTs had not encountered during their pedagogical studies as they focused primarily on classroom-based practices of language education. The design work and orchestration provided the PSTs with new experiences and practices of being language teachers to be integrated into their historical bodies, strengthening their professional vision and agency. In carrying out teamwork in a shared space, monitoring the participants’ actions, and rendering their reasoning to others (e.g. through talk) is necessary for the joint activity to proceed (Hindmarsh & Heath, Citation2007) as Extract 2 illustrates in the following section.

4.3. Developing the design with pedagogical insight

The design-driven course approach and action in the hybrid space in the office allowed the PSTs to follow how their Tech Town design was adopted by the pupils. It also made it possible to negotiate solutions in situ, changing the planned course of action immediately if needs arose. In this respect, the course differed from language teacher education approaches where PSTs’ collaborative negotiation and reflection during practice lessons is not easy.

The Tech Town concept was designed following the idea of language learning emerging from participation in meaningful social action (van Lier, Citation2007). The online environment provided bridges between design and use via the documents created by the PSTs. After the PSTs had tested and evaluated the functionality of the activities, they forwarded the amended documents to other course participants to advance the overall design in later meetings.

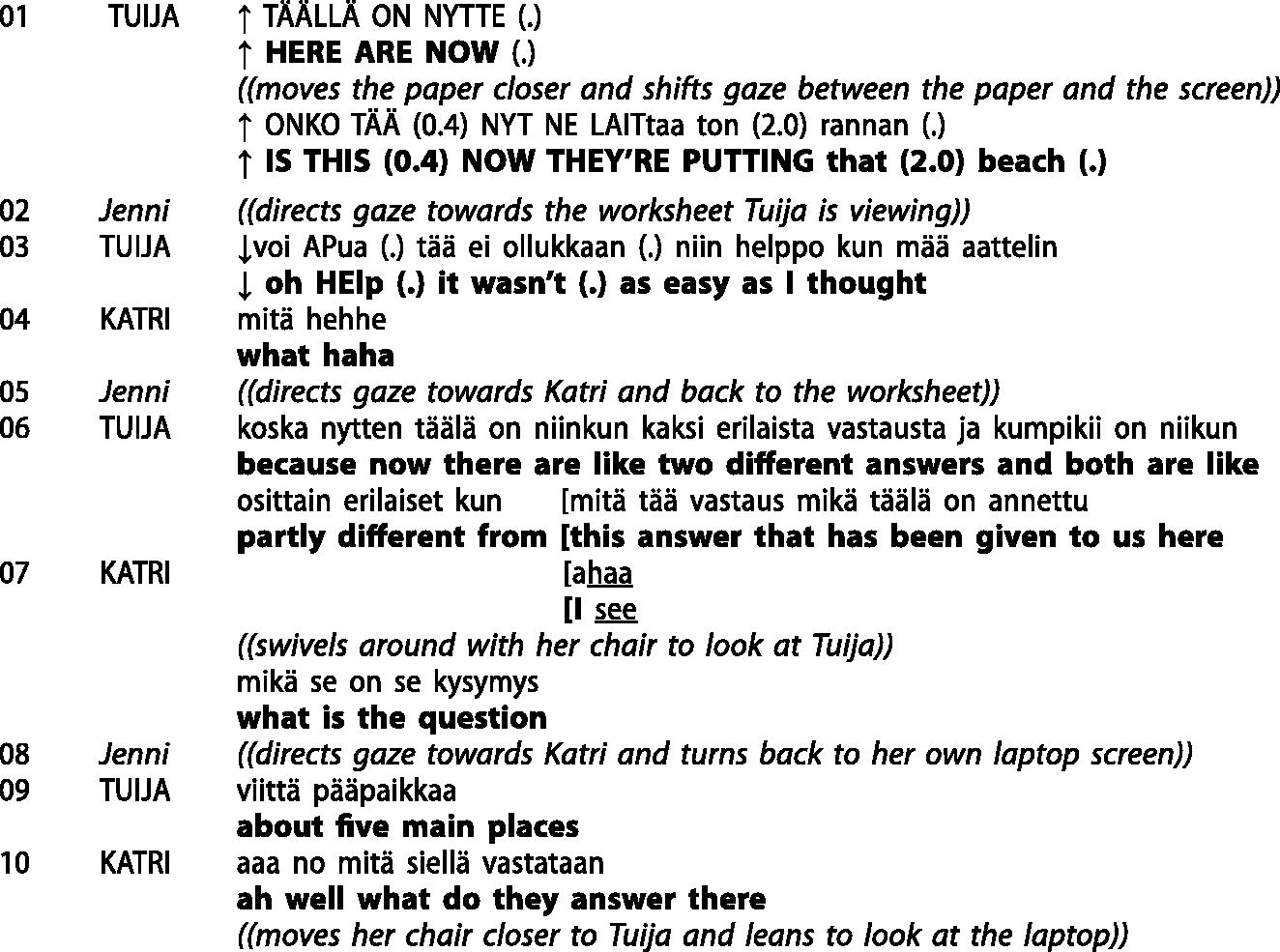

Extract 2 illustrates how unexpected answers from pupils lead Tuija to recruit the other team members to join her in a pedagogical evaluation of the activity at hand because she is unsure of an appropriate reaction. The pupils’ task had been to answer quiz questions about events in Tech Town during the past three weeks of the project. In the following, Tuija is viewing pupils’ responses to a seemingly simply question: What are the five main places in Tech Town?

(2) Reacting to unexpected answers (v8, 34:40 − 35:07)

Tuija is not able to use the planned answer on the printout of a design document produced by others on the course. She raises her voice, hence foregrounding the situation as something that needs attention from the others (01). By switching her orientation between the printout and the chat window on the computer screen showing the pupils’ answers, she moves in the hybrid space evaluating the relationship between the designed activity and how it works in practice from a pedagogical perspective. With a lower voice, talking to herself, she reflects on her earlier interpretation having been too optimistic (03), beginning to render a contradiction between the design and its success in real-life use.

Jenni pays attention to the problem by directing her gaze towards Tuija and then to the worksheet (02). Katri acknowledges Tuija’s concern asking for clarification with reassuring laughter (04) continuing her work on the computer, however. Tuija reformulates the problem about the possibility of more than one correct answer (06). This triggers Katri’s attention, who swivels around in her chair (07). At this point, Jenni apparently assesses the problem as not needing her contribution and turns her gaze and body posture back towards her own screen (08). After hearing Tuija’s reply (09), Katri asks what the pupils have answered and moves closer to Tuija changing her body posture to get a better view of her laptop screen, sharing her concern (10).

Considering the interaction order, the example illustrates how the lecturer positions herself as a participant while being engaged in joint problem-solving. Her questions voiced aloud provide scaffolds for them all to join in the reasoning to find an appropriate solution. After reaching a shared understanding on how to answer to the pupils, the situation continues with a joint negotiation between the participants as they attempt to make sense about the origin of the problem (Extract 3). The extract below exemplifies the discussions dealing with pedagogical considerations emerging in action in the hybrid space. These exchanges were typically brief, as the participants needed to maintain their focus on the online work with the pupils.

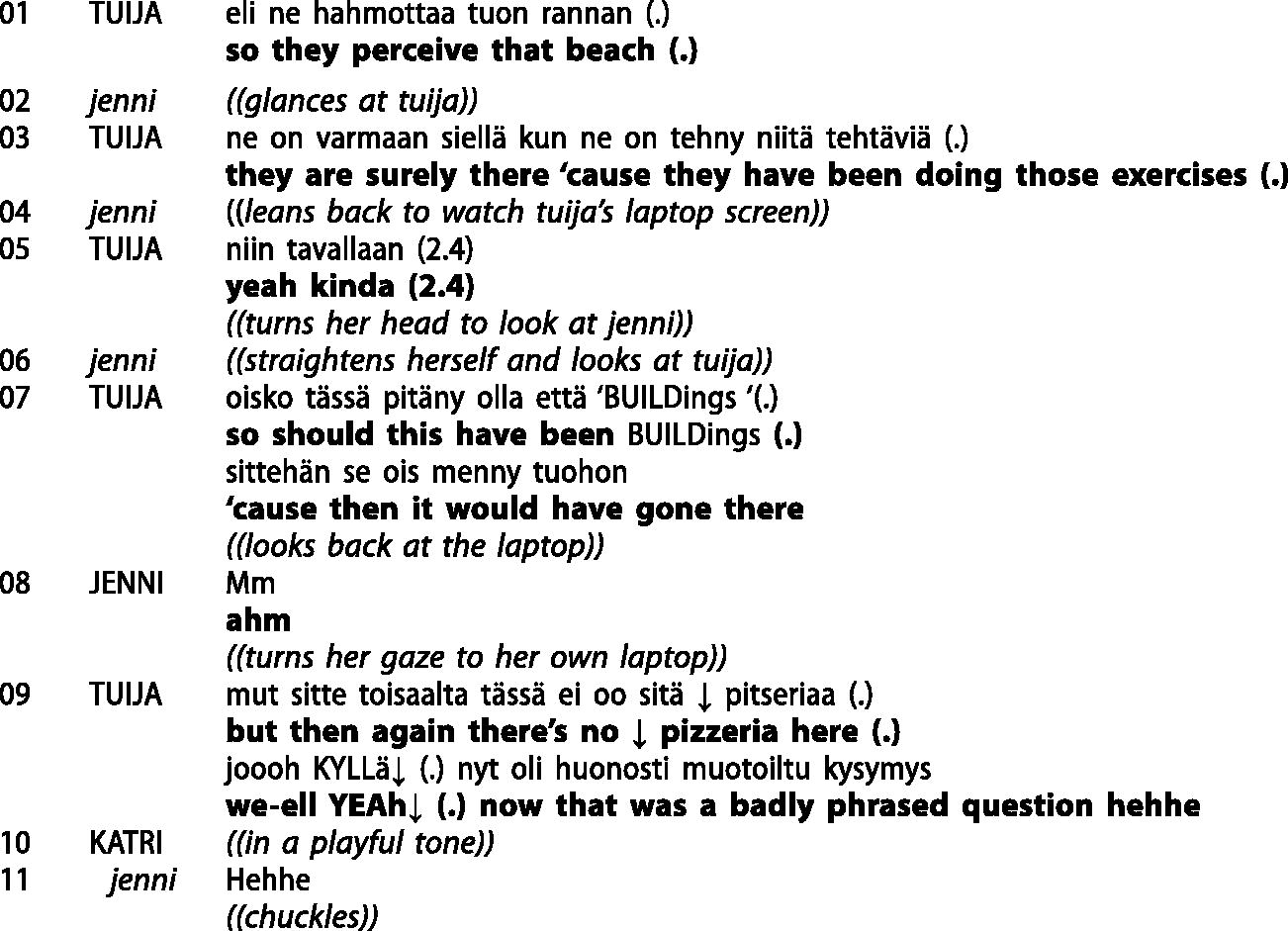

(3) Pedagogical assessment of the question (v8, 36:10–36:33)

In Extract 3, Tuija pays attention to the ambiguity of the question and quickly attempts to rephrase it. Tuija first reflects on the task from the pupils’ perspective and considers how the pupils’ experience of the learning project affects the interpretation of the question. She suggests that the pupils have considered the beach as a main place of Tech Town because it provided the venue for some online exercises earlier (03). The beach, however, was not listed as one of the main places in the answer key. Tuija contemplates on the wording of the activity and suggests that ‘building’ should have been used instead of ‘place’ to match the question and answer (07) but realises then that the answer key would still remain problematic (09). Jenni maintains her focus on the online space, but her embodied action (04, 06) and brief response (08) show that she follows Tuija’s reasoning and aligns with her. Tuija ends her reflection with a critical assessment we-ell YEAh (.) now that was a badly phrased question but does that in a playful manner (09). Katri laughs a little and Jenni chuckles as well creating rapport between participants.

The interaction exemplifies mutual trust between participants in joint problem solving, which allows the PSTs to assume relational agency in decision making as designers and teachers. The PSTs show their insecurities when facing a pedagogical problem, but also assume agency in pedagogical decision making. The lecturer provides support by asking clarifying questions but gives the floor to the PSTs to make the decisions as they evaluate the designed activity and finetune it on the fly.

Furthermore, the examples show how the PSTs consider the relationship between the pedagogical design and its practical implementation as they focus on issues arising from ambiguous tasks and instructions. The setting provides a possibility to reflect on the situation in action together with others. The reflections related to the design of the activities and ambiguity in the word choice of the question demonstrate the PSTs’ growing awareness of the complex relations that affect a well-functioning pedagogical question. The PSTs engage in finetuning the designs by considering revisions to clarify the question, which exemplifies their professional vision in emergence. The pedagogical vision here involves paying attention not only to managing momentary activities but also to the linkage of those activities to a wider frame of reference with long-term pedagogical goals.

5. Discussion

The study portrayed how PSTs’ professional vision (Meskill et al., Citation2020) and agency (Ahearn, 2001; Edwards, Citation2007) emerge in situated interaction when orchestrating language learning in a hybrid setting. Orchestration as social action was examined as an intersection of interaction orders between participants, their historical bodies, and discourses in place (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). The analysis brought to the foreground three main aspects of orchestration (see ). Firstly, the PSTs were engaged in coordinating action and establishing continuity, which made the pupils’ participation in the Tech Town activities online possible from their school localities. Secondly, when the children were accessing the online space, the PSTs were monitoring and attending to emerging needs of various kinds. Thirdly, the PSTs were involved in developing the Tech Town design by paying attention to the pedagogical aims for creating affordances for meaningful interaction and pupils’ active participation. This required reviewing ongoing actions and assessing needs for improvement, some of which were dealt with immediately, and others regarding the upcoming activities after the session. These aspects of orchestration intertwined during sessions due to the situationally emerging flow of pupils’ participation in the Tech Town activities.

The historical bodies of the PSTs have been shaped in a learning culture where the teacher is typically responsible for leading the overall flow of the work, even if activities are student-centred (Aalto et al. Citation2019; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). Promoted by the design-driven approach and the arrangement for the tutoring sessions in the lecturer’s office, an interaction order foregrounding equal participation was emerging as the PSTs were able to take more initiative in providing guidance and in the ongoing pedagogical design. This was made possible by the lecturer’s expression of uncertainty, for example, and the avoidance of tackling problematic situations herself, which gave the floor to the PSTs to decide how to proceed (see also Tumelius & Kuure, Citation2021). For the PSTs participating in our study, the design-driven course on designing and orchestrating language learning in hybrid spaces was the first opportunity for planning and implementing online school projects. Being able to experiment with a pedagogical configuration in a hybrid space gave them experiences of being language teachers, allowing them to assimilate new ingredients to merge with their historical bodies as pedagogical professionals of the future (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004; see also Blin & Jalkanen, Citation2014).

The configurations of the participants in the hybrid space and the working methods gave room for various kinds of discourses to arise among the PSTs and the lecturer (see also Tumelius & Kuure, Citation2021). The setting promoted a deeper understanding of the complexities of design work and orchestrating action in a hybrid space by allowing the PSTs to assume different positions as designers, teachers, and students. Moreover, the hybrid space with the pupils co-present online made the free exchange of ideas between the lecturer and the PSTs possible. They were able to discuss and evaluate their experiences of orchestrating the activities at hand. This had potential consequences for future actions during the on-going session as well as for the development of the overall design of the Tech Town learning environment. While engaging in in situ action, the PSTs were also enacting wider-scale discourses drawing from curricula, policies, and infrastructures (see Barahona, Citation2020; Hammerness, Citation2008; Kubanyiova, Citation2020).

The design-driven procedure and teamwork between co-present participants afforded fruitful circumstances for interaction opening a window to their reflections during the work (Schön, Citation1987). By engaging in collaboration with others and providing mutual support, the PSTs expanded their personal understandings and pedagogical repertoires, i.e. the relational aspect of their agency (Edwards, Citation2007). The lecturer also positioned herself as one of the team members. Instead of assigning responsibilities to the PSTs, she took part in joint problem solving and the emerging tasks that required attention during the work. She explicated her uncertainty and hesitance to provide solutions to the PSTs, giving them the opportunity to assume agency by taking the project into their own hands, which they did. This not only was a natural approach to teamwork in a design project but also the lecturer’s conscious choice in the role of teacher educator.

The design project allowed the PSTs to experiment with the pedagogically informed use of technologies: not with technology as a starting point, but elaborating a target design that the participants, both the PST designers and the pupils as users would find meaningful (see Colpaert & Gijsen, Citation2017). The analysis foregrounded the PSTs’ emerging professional vision and agency, gaining ownership and responsibility over the project (Ahearn, Citation2001; Barahona, Citation2020; Edwards, Citation2007; Goodwin, Citation1994).

6. Conclusion

The study brought to the foreground the complex and situationally changing nature of orchestration in a hybrid setting in the context of a pupils’ English learning project. From the perspective of the PSTs’ development of their professional vision and agency, the pedagogical approach of the course following a design process and the lecturer’s engagement in the project as an equal team member were important. The design and orchestration of pupils’ language learning proceeded as a joint accomplishment between the lecturer and the PSTs. Therefore, the final target was new to everyone including the lecturer. This situation supported the participants’ position as equal members in the team, and afforded opportunities for joint problem solving, sense making, and reflection, while leading the PSTs to assume agency in terms of making decisions and configuring their actions.

The balanced interaction order gave space for a broad range of discourses and sense making between familiar and new practices of language education. As the pupils were not physically co-present, the range of discourse also became more varied in the hybrid space than in a classroom as it was possible to render reasonings accessible for other PSTs freely, negotiate meanings aloud and redirect action in progress. The setting made ongoing design and orchestration in situ tangible for analysis.

Nexus analysis proved to be a useful tool in understanding the complexities involved in examining the emergence of professional vision and agency of future language teachers. The study sparks further research in diverse directions. From the perspective of integrating the pedagogical use of technologies in language teacher education, longitudinal research designs need to be promoted to follow the emergence of PSTs’ professional vision and agency as they move from being students to becoming practitioners. Another interesting path would be to explore in more detail the participants’ situated movements across digital and physical spaces, the linked rhizomes of discourses and the resemiotisation of pedagogical designs as an interactionally accomplished distributed process.

Note

1. ECTS is short for the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System where a credit unit refers to workload. In Finland, one ECTS credit equals 27 study hours, and the scope of one academic year of 1600 study hours is 60 ECTS (see https://www.study.eu/article/what-is-the-ects-european-credit-transfer-and-accumulation-system).

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the university students, language teachers and their pupils involved in our research, as well as to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments advancing our writing process.

Disclosure statement

No financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct applications of the research.

Data availability statement

The research materials for the study are not available due to restrictions set by informed consent.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Riikka Tumelius

Riikka Tumelius is a Doctoral Researcher at the University of Oulu, Finland, with a professional background of a foreign language teacher. She is interested in how to design language learning in the light of our changing everyday life with ubiquitous technologies, and how to investigate change in the accustomed practices of language pedagogies. She draws on mediated discourse theory and nexus analysis in her work.

Leena Kuure

Leena Kuure is a University Lecturer Emerita at the University of Oulu, Finland, and an Adjunct Professor at the University of Eastern Finland, with a research interest in how expertise in technology-mediated language education can be examined and advanced among language students through design and project based pedagogical approaches. Her theoretical and methodological perspectives draw on mediated discourse theory and nexus analysis.

References

- Aalto, E., Tarnanen, M., & Heikkinen, H. L. T. (2019). Constructing a pedagogical practice across disciplines in pre-service teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.06.006

- Ahearn, L. M. (2001). Language and agency. Annual Review of Anthropology, 30, 109–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.30.1.109

- Anderson, T., & Shattuck, J. (2012). Design-based research: A decade of progress in education research? Educational Researcher, 41(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X11428813

- Ashton, K. (2022). Language teacher agency in emergency online teaching. System, 105, 102713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102713

- Barahona, M. (2020). Developing and enacting professional pedagogical responsibility: A CHAT perspective. The European Journal of Applied Linguistics and TEFL, 9(2), 131–152.

- Blin, F., & Jalkanen, J. (2014). Designing for language learning: Agency and languaging in hybrid environments. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 8(1), 140–170. https://apples.journal.fi/article/view/97861

- Booth, P., Guinmard, I., & Lloyd, E. (2017). The perceptions of a situated learning experience mediated by novice teachers’ autonomy. The EUROCALL Review, 25(1), 76–91. https://doi.org/10.4995/eurocall.2017.7081

- Buchanan, R. (2015). Teacher identity and agency in an era of accountability. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 21(6), 700–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044329

- Clarke, A. E. (2003). Situational analyses: Grounded theory mapping after the postmodern turn. Symbolic Interaction, 26(4), 553–576. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.2003.26.4.553

- Colpaert, J., & Gijsen, L. (2017). Ontological specification of telecollaborative tasks in language teaching. In C. Ludwig, & K. Van de Poel (Eds.), Collaborative learning and new media. New insights into an evolving field (pp. 23–39). Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/b11402

- Dillenbourg, P. (2008). Integrating technologies into educational ecosystems. Distance Education, 29(2), 127–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802154939

- Dooly, M. (2017). A mediated discourse analysis (MDA) approach to multimodal data. In E. Moore, & M. Dooly (Eds.), Qualitative approaches to research on plurilingual education (pp. 189–211). Research-publishing.net. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2017.emmd2016.628

- Dooly, M., & Sadler, R. (2013). Filling in the gaps: Linking theory and practice through telecollaboration in teacher education. ReCALL, 25(1), 4–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344012000237

- Edwards, A. (2007). Relational agency in professional practice: A CHAT analysis. Actio: An International Journal of Human Activity Theory, 1(1), 1–17.

- Ensor, S., Kleban, M., & Rodriguez, C. (2017). Telecollaboration: Foreign language teachers (re)defining their role. ALSIC – Language Learning and Information and Communication Systems, 20(2). https://doi.org/10.4000/alsic.3140

- Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. (2019). The ethical principles of research with human participants and ethical review in the human sciences in Finland. Publications of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity TENK 3/2019.

- Finnish Social Science Data Archive (2022). Data Management Guidelines [Online]. Tampere: Finnish Social Science Data Archive [distributor and producer]. https://www.fsd.tuni.fi/en/services/data-management-guidelines/

- Gillespie, J. (2020). CALL research: Where are we now? ReCALL, 32(2), 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344020000051

- Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. Basic Books.

- Golombek, P. R., & Johnson, K. E. (2017). Re-conceptualizing teachers’ narrative inquiry as professional development. Profile – Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 19(2), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v19n2.65692

- Goodwin, C. (1994). Professional vision. American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606–633. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100

- Goodwin, C. (1995). Seeing in depth. Social Studies of Science, 25, 237–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631295025002002

- Guichon, N. (2010). Preparatory study for the design of a desktop videoconferencing platform for synchronous language teaching. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(2), 169–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221003666255

- Guichon, N., & Wigham, C. (2016). A semiotic perspective on webconferencing-supported language teaching. ReCALL, 28(1), 62–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344015000178

- Hammerness, K. (2008). If you don’t know where you are going, any path will do”: The role of teachers’ visions in teachers’ career paths. The New Educator, 4(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476880701829184

- Harsch, C., Müller-Karabil, A., & Buchminskaia, E. (2021). Addressing the challenges of interaction in online language courses. System, 103, 102673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102673

- Hindmarsh, J., & Heath, C. (2007). Video-based studies of work practice. Sociology Compass, 1(1), 156–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00012.x

- Hubbard, P. (2008). CALL and the future of language teacher education. CALICO Journal, 25(2), 175–188. http://www.jstor.org/stable/calicojournal.25.2.175

- Hubbard, P. (2019). Five keys from the past to the future of CALL. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching, 9(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJCALLT.2019070101

- Jefferson, G. (2004). Glossary of transcript symbols with an introduction. In G. H. Lerner (Ed.), Conversation analysis: Studies from the first generation (pp. 13–31). John Benjamins.

- Jeong, K.-O. (2017). Preparing EFL student teachers with new technologies in the Korean context. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(6), 488–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1321554

- Jones, R. (2005). Sites of engagement as sites of attention: Time, space and culture in electronic discourse. In S. Norris, & R. Jones (Eds.), Discourse in action: Introducing mediated discourse analysis (pp. 141–154). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203018767

- Karamifar, B., Germain-Rutherford, A., Heiser, S., Emke, S., Hopkins, J., Ernest, P., Stickler, U., & Hampel, R. (2019). Language teachers and their trajectories across technology-enhanced language teaching: Needs and beliefs of ESL/EFL teachers. TESL Canada Journal, 36(3), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v36i3.1321

- Kayi-Aydar, H., Gao, X., Miller, E. R., Varghese, M., & Vitanova, G. (2019). Theorizing and Analyzing Language Teacher Agency. Multilingual Matters.

- Knight, J., Dooly, M., & Barberà, E. (2020). Navigating a multimodal ensemble: Learners mediating verbal and non-verbal turns in online interaction tasks. ReCALL, 32(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344019000132

- Koivistoinen, H., Kuure, L., & Tapio, E. (2016). Appropriating a new language learning approach: Processes of resemiotisation. Apples – Journal for Applied Language Studies, 10(2), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.17011/apples/urn.201612145091

- Kubanyiova, M. (2020). Language teacher education in the age of ambiguity: Educating responsive meaning makers in the world. Language Teaching Research, 24(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168818777533

- Kuure, L., Molin-Juustila, T., Keisanen, T., Riekki, M., Iivari, N., & Kinnula, M. (2016). Switching perspectives: From a language teacher to a designer of language learning with new technologies. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29(5), 925–941. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2015.1068815

- Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a design science. Building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. Routledge.

- Levy, M., Hubbard, P., Stockwell, G., & Colpaert, J. (2015). Research challenges in CALL. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.987035

- Lindroth, J. T. (2015). Reflective journals: A review of the literature. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 34(1), 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/8755123314548046

- Meskill, C., Anthony, N., & Sadykova, G. (2020). Teaching languages online: Professional vision in the making. Language Learning & Technology, 24(3), 160–175. https://doi.org/http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44745

- Moser, K. M., Wei, T., & Brenner, D. (2021). Remote teaching during COVID-19: Implications from a national survey of language educators. System, 97, 102431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102431

- Nishida, K. (1958). Intelligibility and the philosophy of nothingness. Maruzen.

- Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction. A methodological framework. Routledge.

- Özverir, I., Mokhtari, L., & Özverir, A. (2021). A systematic analysis of design-based research in technology-enhanced language learning. HAYEF: Journal of Education, 18(3), 323–352. https://doi.org/10.5152/hayef.2021.21038

- Pischetola, M. (2022). Teaching novice teachers to enhance learning in the hybrid university. Postdigital Science and Education, 4, 70–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-021-00257-1

- Pouta, M., Lehtinen, E., & Palonen, T. (2020). Student teachers’ and experienced teachers’ professional vision of students’ understanding of the rational number concept. Educational Psychology Review, 33, 109–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09536-y

- Ryberg, T., Davidsen, J., & Hodgson, V. (2018). Understanding nomadic collaborative learning groups. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(2), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12584

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. Jossey-Bass.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2004). Nexus analysis: Discourse and the emerging internet. Routledge.

- Stickler, U., Hampel, R., & Emke, M. (2020). A developmental framework for online language teaching skills. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(1), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v3n1.271

- Stürmer, K., Könings, K., & Seidel, T. (2013). Declarative knowledge and professional vision in teacher education: Effect of courses in teaching and learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 83(3), 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02075.x

- Sun, S. (2017). Design for CALL – possible synergies between CALL and design for learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(6), 575–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1329216

- Tao, J., & Gao, X. (2021). Language teacher agency. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108916943

- Tumelius, R., & Kuure, L. (2021). Towards a shared vision of language, language learning, and a school project in emergence. Classroom Discourse, 12(4), 344–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2020.1808495

- van Lier, L. (2007). Action-based teaching, autonomy and identity. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 46–65. https://doi.org/10.2167/illt42.0

- Voogt, J., Laferrière, T., Breuleux, A., Itow, R. C., Hickey, D. T., & McKenney, S. (2015). Collaborative design as a form of professional development. Instructional Science, 43, 259–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-014-9340-7

- Wang, Y., Chen, N.-S., & Levy, M. (2010). Teacher training in a synchronous cyber face-to-face classroom: characterizing and supporting the online teachers’ learning process. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 23(4), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2010.493523

Appendix.

Transcription conventions

The transcription conventions applied from Jefferson (Citation2004) are illustrated below.