Abstract

Current approaches to assessing digital competence in education may be too broad to support teachers in developing their online learning designs in specific subjects. During the pandemic, studies have identified that the development of teaching practices (and subsequently their learning designs) has taken a leap. However, because digital cultures differ between schools, local approaches need to survey how their practices have developed and what emerging practices can become good examples for others. Using a descriptive multiple case (n = 20) study methodology with observations, interviews (n = 33), and a survey, 12 elements in second language online learning designs (LDs) that seemed to engage learners and support online learning were identified. Data were analysed using pattern matching and descriptive statistics. Post observation, teachers were asked to rate the importance of the ability to include the element and how difficult they perceived its implementation would be. A case overview was used to contrast the survey. Results reveal that the number of digital technologies has little to do with the complexity of designs, and teachers with relatively few digital resources can offer more complex LDs. While most teachers rated the elements suggested as easy, the observations did not support this. However, around 30% of the teachers rated at least seven important elements as difficult or very difficult and designing learning activities that stimulate engagement in nuanced ways was considered challenging. This paper proposes that, identifying local elements may be a suitable way forward to support professional development, as well as to reframe teachers’ digital practices post Covid-19.

1. Introduction

To offer attractive ways to engage in lifelong learning, adult education strives to be as flexible as possible by using digital technologies. Today, learners may use a range of digital devices to access learning from a variety of locations (Sugden et al., Citation2021). With emerging digital technologies, teachers are required to re-think their learning designs (LDs) (Dillenbourg, Citation2013). Several studies exploring online learning have focused on the effectiveness of online learning activities and often include interaction as a marker for quality. They address, for example, active (versus passive) learning through cooperation and collaboration (Prince, Citation2004) and interactivity in designs for computer-mediated learning (Rosell-Aguilar, Citation2005), as well as interaction with the Learning Management System (LMS) (Soleimani & Lee, Citation2021) or teacher and peer interaction (Strang, Citation2016). Research has shown that LDs that integrate digital technologies influence how students engage in individual (Engle & Conant, Citation2002) as well as collaborative learning activities (Mejia, Citation2020; Vuopala et al., Citation2014). While the ability to design engaging learning activities is included in quality standards for online learning (Powell & Oliver, Citation2019), it can be challenging.

While studies often refer to teachers as designers (e.g. Goodyear & Dimitriadis, Citation2013; Kress & Selander, Citation2012; Laurillard, Citation2012), it has been highlighted that there is a lack of guidance on how to approach design in complex digital learning environments (Goodyear, Citation2020). Such guidance could potentially be derived locally or informed by research. Locally, there is a strong belief that the teachers themselves can guide and lead the development of practices within a school. However, it has recently been pointed out that these initiatives may not be as effective as one might hope. Without proper documentation and often overlooking influencing conditions and context, such initiatives seldom lead to the contribution of new knowledge, partly because teachers may lack the necessary analytical and theoretical tools and scientific orientation (Eriksson, Citation2020).

Turning to other research, there is a subtle difference in focus between studies exploring learning activities and those exploring how learning is organised and supported online. For example, Andersen and Ponti (Citation2014) and Sunar et al. (Citation2015) explored personalisation and found that when students co-create the design of their (personalised) learning, the workload of the teacher was reduced. However, LD in second language learning (L2) should support students in progressing from language comprehension to language production, which requires more than organisation. A recent review on L2 learning revealed that most research focus on the four basic skills (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) (Peng et al., Citation2021). When progressing from comprehension to production, however, participants need to have listening- and speaking skills to enable meaning-making in interactions (Pekarek Doehler, Citation2018), where such interactions can be conversational and include verbal and non-verbal communication (Ellis & Ferreira-Junior, Citation2009) or collaboration.

In addition to language tutorials, subtitles, text-to-speech applications, spelling, and grammar checkers (see more in Chappelle, 2016), digital technologies can include media (e.g. visualisations, audio, video) to provide ample opportunities for language modelling, recording, and peer and teacher feedback (Saito & Akiyama, Citation2017). Traditional distance education has often focused on asynchronous (delayed) modes of delivery which require a high degree of self-directed learners. However, interaction is not exclusive to synchronous (real-time) modes of delivery (Akiyama & Cunningham, Citation2018). Some asynchronous courses do offer asynchronous interaction, which has been seen to have a positive impact on L2 learners (Ziegler, Citation2016). Recent research indicates that there may be a slight shift of attitude toward the traditional view of distance education, as teachers who taught asynchronous courses display an increased interest in implementing synchronous elements for specific pedagogical aims (Leijon & Juni, Citation2021). Leijon and Juni (Citation2021) predicted that this might be the first step toward a common blend of synchronous and asynchronous practices in distance education. Previous studies have also explored common practices in L2 learning but concluded that categories produced to capture these might be too broad to be informative and suggest a more detailed approach (Akiyama & Cunningham, Citation2018). This paper suggests that a systematic intervention can bridge the gap between academia and practitioners and strives to identify how teachers make learning design decisions in synchronous and asynchronous modes of delivery. Conducting a multiple case study in one school with several teachers can offer insights into current and innovative demonstrated design intentions in both asynchronous and synchronous modes, and this study aims to capture elements in LDs that may be at the forefront of this development by focusing on teachers’ ratings. With this objective in mind, the following research questions are raised:

What are some innovative elements in synchronous and asynchronous L2 LDs?

How do teachers rate the identified elements in terms of importance?

How do teachers rate the identified elements in terms of the difficulty in implementing them by building on their own ability?

2. Background

2.1. Elements of learning design in CALL

In recent decades, basic instructions on how language teachers should qualitatively teach language learning in online modes have been established (Bauer-Ramazani, Citation2006; Kern, Citation2021), and these have particularly strived to create and sustain an effective and enthusiastic community of learners whilst employing the potential of digital technologies (Butler-Pascoe & Wiburg, Citation2003; Goodyear, 2013; Citation2020). As asynchronous education is much more well-established than synchronous education, there may be a widespread belief that asynchronous learning must equal self-directed learning (Cho et al., Citation2017; Rienties et al., Citation2019; Toro-Troconis et al., Citation2019). Because of this, teachers may regard asynchronous education as learning with a ‘one-sided focus on individual cognition’, similar to what has been criticised (Spolsky, Citation1989). Learning design has a clear educational aim (Selander, Citation2008). It is concerned with information, communication, knowledge creation (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2001), pre-designed structure (which learners have been found to follow when they login to the LMS) (Zeng et al., Citation2020) and the multimodal production of learners to enhance meaning-making and knowledge construction (Kress & Selander, Citation2012; Selander, Citation2008). Multimodality refers to the possibility of making use of additional resources for language expression as can, for example, be seen in media, 3D sculptures, audio, and combinations of expression (Insulander et al., Citation2021). LD, on the other hand, is concerned with the design of learning activities and has been defined as ‘a methodology for enabling teachers/designers to make more informed decisions in how they go about designing learning activities and interventions, which is pedagogically informed and makes effective use of appropriate resources and technologies’ (Conole, Citation2012:121). In this study, the elements of learning designs are analysed, where several elements may be linked together to form a learning sequence, which can, in turn, form an LD (noun). As such, an LD can be viewed as a product that can describe tasks and resources with pedagogical intent (Lockyer et al., Citation2013). While LDs do reflect intended pedagogical actions, they are not detailed plans that convey logically arranged content, as found in a traditional lesson plan (Lockyer et al., Citation2016).

2.2. Connectivist theory

Connectivist theory incorporates central ideas from earlier learning theories and extends these to the 21st-century digital educational context (Siemens, Citation2004). As such, connectivist theory proposes that digital resources influence and are critical for (L2) learning (Kern, Citation2021; Stockwell, Citation2014). For example, teachers’ design considerations have included several critical elements such as preparation, personalisation, student-centred instruction, support, and collaboration (Coryell & Chlup, Citation2007), but the conditions for teaching and learning online change as digitalisation progresses. Today, L2 learners can engage in a variety of ways using both asynchronous and synchronous modes of learning (Akiyama & Cunningham, Citation2018; Loncar et al., Citation2021). Thus, teachers must have the insights and skills needed to make informed decisions concerning which elements to include in their LDs to ensure they provide qualitative education. A one-sided approach, e.g. focusing on the practice of one basic skill, will not lead to the same language acquisition, as varied learning activities that allow the practice of the multiple skills are needed to master the target language (Geeslin et al., Citation2006; González-Lloret & Ortega, Citation2014; Peng et al., Citation2021). Here, connectivist theory highlights that the ability to extend existing knowledge is more vital than a mere focus on the existing knowledge (Siemens, Citation2004). That is, how to use digital tools and resources in ways to further extend capacity and capability is central. In adopting a multimodal approach to exploring teacher instruction and interaction, Wigham and Satar (Citation2021) found that it was critical that the teacher use the technologies intentionally and seamlessly and move back and forth between different resources: first to embody a digital resource (i.e. a digital resource for practising basic skills) and then to make it accessible to learners. In another study, Canals (Citation2021) found that multimodal elements, the combination of multimodal elements and learners’ use of the native and target language, were more frequently used when learners corrected and adjusted their language use. They also found that such synchronous elements support learner progression.

2.3. Engagement and self-regulation

Engagement can be operationalised as a four-dimensional construct with a behavioural dimension reflecting actions that support learning: a cognitive dimension that includes students’ strategies and efforts, and focuses directly on learning; an emotional dimension with positive and negative reactions to learning; and a social dimension where students display pro-social behaviour (Bond et al. Citation2022; Fredricks et al., Citation2016). While engagement and self-regulation (SRL) are related, scholars are not yet in agreement with the exact nature of the relationship. Although much research explores SRL separately from engagement, self-regulation can be viewed as a subconstruct to engagement (Appleton et al., Citation2006; Reeve & Tseng, Citation2011). This, since engagement measures in the cognitive dimension, subsumes SRL measures (Fredricks et al., Citation2016; Greene, Citation2015). Self-regulated learning strategies include the ability to plan, monitor, and evaluate learning-related activities (Zimmerman, Citation2008). Thus, in asynchronous learning, owning self-regulative abilities is vital for academic success (Cho et al., Citation2017; Rienties et al., Citation2019). That students plan and decide on strategies and set goals can be described both as cognitive engagement and self-regulation (e.g. Fredricks et al., Citation2016). From a CALL perspective, researchers have suggested that scaffolding, and prompts can support learners in applying metacognitive and self-regulatory abilities and in developing their reading strategies (Mežek et al., Citation2022; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2018). While self-regulation has been used to operationalise cognitive engagement (e.g. Wang & Eccles, Citation2012; treating SRL and cognitive engagement indicators as identical), others have also included strategy (Appleton et al., Citation2006; Tempelaar, Citation2020), effort exertion (Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, Citation2012), avoidance of failure (Martin, Citation2007) and concentration (Bergdahl et al., Citation2020) as indicators when measuring cognitive engagement. Early L2 theories have been criticised for having a one-sided focus on individual cognition at the expense of social and cultural dimensions of learning (Spolsky, Citation1989). Others, in contrast, acknowledge the importance of the situatedness and social context of learning since, when learning together, students can draw on shared insights and mutual efforts can increase their capacity, allowing for greater progress compared than that achievable by one individual (Firth & Wagner, Citation2007; van Aalst, Citation2013; Johnson & Johnson, Citation2008). This, in turn, can lead to higher results (Lasry et al., Citation2008). A critical aspect of such group collaboration is socially shared regulation (SSRL), which refers to learners negotiating their understanding of the task and deciding on strategies and actions in order to reach the agreed goal(s) (Hadwin et al., Citation2018). However, by exploring learner engagement in SSRL, Järvelä et al. (Citation2013) found that shared regulation can be challenging for learners to sustain, and that support in regulating as a collective is beneficial. Students that are highly engaged show greater confidence in their effort and ability, have a supportive network (i.e. parents, teachers) and display an increased number of self-regulatory styles, higher goals, optimism, pro-social behaviour toward teachers and peers (Skinner et al., Citation2009).

2.4. Designing for engagement

While LD can be viewed as the teacher’s intention to design engaging learning activities (Dohn et al., Citation2019), teachers’ digital competence has been described as ‘the ability to design for learning with digital tools and resources’ (From, Citation2017). Therefore, it is unsurprising that some learning activities are associated with low levels of engagement (e.g. Bergdahl & Bond, Citation2021; Hampel & Pleines, Citation2013). For example, Rienties et al. (Citation2018) identified that learners’ workload was concentrated to assimilative, productive, and assessment types of learning activities and that 55% of the variation in learner activities was related to teachers’ LD. However, teachers can develop their LDs to increase learner engagement (Hampel & Pleines, Citation2013; Toetenel & Rienties, Citation2016). Such effort may also lead to an increased interest in exploring functionalities and integrating educational technologies into their designs (Asensio-Pérez et al., Citation2017). Thus, it seems as if both the design and the enactment of the design are critical for L2 online learning (Awuor et al., Citation2021; Rienties et al., Citation2018; Teng, Citation2017). Ernest et al. (Citation2013) asked higher education L2 teachers to rate areas they found important to address (and manage) in professional development. Those related to L2 LD were providing instructions, using forums and online tools, supporting a sense of community, synchronous and asynchronous use of technologies, and supporting ‘learning by doing’. Reinhardt and Thorne (Citation2019) propose that LD should reflect the multilateral qualities of today’s digital society and include web scavenger hunts, WebQuests, online role-play, and other simulation activities (Reinhardt & Thorne, Citation2019: 15). Furthermore, a recent literature review on emerging online practices suggests that teachers in the future will design and facilitate varied, engaging, inclusive, and collaborative learning in flexible learning environments where synchronous and asynchronous elements are blended (Leijon & Juni, Citation2021). In CALL, however, the critical component revolves around supporting the language acquisition of L2 learners. For example, when learners practice listening comprehension, digital technologies can assist with, for example, speech recognition and repetition (Matthews et al., Citation2017). While task interactivity can trigger active listening, it is unlikely to happen if the teacher has not provided the appropriate materials and favourable modes of delivery (ibid.). Notably, all the above LDs include communicative elements. Since information and communication are the core of LD (Selander, Citation2008), and digitalisation impacts both, it is easy to recognise the intertwined relation between L2 LD and digital resources, where it is difficult to imagine one without acknowledging the effects of the other (Stockwell, Citation2014). Researchers have concluded that careful consideration should be made in balancing activities that are of a collaborative and self-directed nature as these impact the effectiveness of online education (Toro-Troconis et al., Citation2019). The position in this study is therefore that teachers need to have a rich toolbox of approaches, methods, and strategies and the ability to use these in order to be able to offer varied learning that is suitable for both the educational aim and learners.

3. Methodology

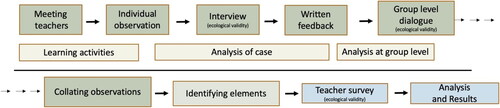

This 9-month intervention study was driven by a discovery motive, where the assumption was that we cannot propel teaching practices if we do not first identify and recognise practices at the forefront. Therefore, to answer the research questions, a mixed-methods approach (Creswell & Clark, Citation2011) was adopted together with a descriptive multiple case study methodology (Yin, Citation2014) in which each teacher was a case and the cases were grouped into the mode that they were currently teaching (see ) (Chapelle & Voss, Citation2016; Yin, Citation2014). A case study approach enables the exploration of a contemporary phenomenon in a real-life setting and is useful when exploring designs and technology use (ibid.).

Table 1. Participant background data * years in occupation.

3.1. Context and participants

The study was conducted at a school for municipal adult education in a Swedish city. The school provided Internet access and Google workspace for education. The purposive sampling (Bryman, Citation2016) was employed to enable the comparison of patterns across synchronous and asynchronous modes (Olofsson et al., Citation2020). Accordingly, all teachers involved taught second language learning courses, including English as a second language (ESL) and Swedish as a second language (SSL), levels 1–4, in the modes Synchronous Distance Education (SDE) or Asynchronous Distance Education (ADE) (see ). The course content (levels 1–4) focused on progressively challenging language training in all basic skills. ADE refers to asynchronous distance education and is a mode in which learners’ responses and interactions are delayed (they are not in real time). SDE, on the other hand, refers to synchronous distance education, and as such, it follows a schema for real-time communication and interaction. At times, teachers offer both ADE and SDE modes using an overarching description of the course as ‘Half-distance’ (HD) (see ).

describes (in order) the gender, mode of educational delivery, subject, level of course, number of observations conducted, and experience, which refers to teachers’ years in their current occupation. HD refers to a combination of ADE and SDE, in which teachers are free to decide on the combination of synchronous and asynchronous modes. While ESL has an equivalent in CEFR, SSL levels 1–4 do not. All ESL courses (marked here as 1–4) are all equivalent to CEFR B1.1.

3.2. Design, data collection and analysis

Data (observations, follow-up interviews and a short survey) were collected at one school between April 2021 and January 2022, and the teacher survey was implemented in the final stages of the intervention. Additional analyses of the intervention (comparing large-scale observations and facilitation of engagement in synchronous and asynchronous modes) is reported elsewhere (e.g. Bergdahl & Gyllander-Torkildsen, Citation2022).

shows the design of the intervention and indicates the role of the researcher. In this explanatory sequential design (Creswell & Clark, Citation2011), the researcher met with the teachers (n = 20) in three (subject-related) groups prior to the observations. The researchers’ role was to support reflective practice, which includes feedback on observed teaching at individual and group levels. During introductory meetings, the study and design were communicated. The observation outcomes were discussed and reflected on at the individual level (as a part of a follow-up interview adjacent to the observation) and the group level (see ), followed by consecutive analyses (following Yin, Citation2014). Data were routinely organised and filed digitally. The researcher then observed the LDs (at the case level) and identified elements (at the case and group level) (see ‘Collating observations’, ). Next, a survey was distributed to teachers in which they were asked to report on how important they found the identified elements to be, and how difficult the elements would be to implement, based on their own ability (see ‘Teacher survey’, ). Finally, the number of occurrences of the elements was combined with qualitative data in the cases overview (Appendix C, cases overview) (see ‘Analysis and Results’, ).

All data from synchronous and asynchronous learning situations consist of detailed minute-by-minute records of teachers demonstrating actual designs in real-time with the digital technology. To develop the observation schema, the first four synchronous lessons were recorded. Relevant sections of the video recordings were then transcribed verbatim. Transcriptions, notes and observation schemas were collated in MS Excel 16.54. For synchronous learning situations, real-time observations were made in situ (n = 9). However, for asynchronous learning situations (n = 24), teachers demonstrated their LDs, intention, and instructions and were asked to take on a student role using a ‘talk-aloud’ method (Li, Citation2016). The teachers completed all the elements in the design by using the technologies (for an overview of technologies used, see Appendix C). As asynchronous learning does not involve scheduled classes, all observations are referred to as learning situations. The think-aloud approach, common in design sciences, refers to when hypothetical users are employed to visualise useability, effectiveness, and risk in use-case scenarios (Kuropka et al., Citation2008). This allows for the arrangement to function as a ‘stimulated recall’ (Li, Citation2016: 108), where the teachers show actual submissions, online discussions, and similar asynchronous ‘proof’ of engagement. Stimulated recall enables insights into design-thinking, such as intention, instruction and considerations that influence teacher decisions, which are often guided by a ‘hunch’ or a ‘feeling’ (Thorpe, Citation2013). Teachers were asked to describe each action in detail and report the time they allocated. During both synchronous and asynchronous data collection, minute-by-minute notes were taken in an Excel schema that included time, learning activity, and description (see Appendix A, B). The teachers’ designs were subsequently discussed with them and their colleagues.

To identify elements in LDs that could potentially advance learning designs and reveal innovative practices in CALL, the following criteria were adopted: 1) the LD seemed to support engagement and learning, 2) teachers utilised digital technologies to enable their LD, and 3) the LD was not demonstrated by all teachers. The selection criteria are motivated as follows: as it is commonly acknowledged that engagement is important for all modes of learning (Bond & Bergdahl, Citation2022), one key aspect was to select those LD elements and foci that seemed to support engagement and learning. The reason for not including mundane LDs was that they were shared among all teachers and hence already being mastered. As the approach does not aim to capture rudimentary designs but rather inspire the further development of L2 LDs, the overview is referred to as the Advancement of Learning Designs (ALD) (see ). To be considered an element in the forefront, teacher demonstration and consideration of the following aspects were important: the complexity of the design, variation, differentiation, the use of resources, the flow of learning sequences, flexibility and innovativeness. Pattern matching was applied across the dataset, and identified elements were added to each case (Yin, Citation2014). Moreover, all cases were collated in an overview with the elements demonstrated (Appendix C). In line with that suggested by Yin (Citation2014), the narrative in the case descriptions includes citations from respondents and the observation schema, and follow-up interviews were used to provide a richer interpretation of what was observed. After having identified the elements, teachers were asked to answer an anonymous survey. The survey contained two questions about how important and difficult the teachers considered the LDs to be. The survey was sent out using Google forms, and data were analysed using descriptive statistics. As such, both narrative and tabular forms were used as data (Yin, Citation2014). The case overview (Appendix C) was then used to discuss the survey results.

Table 2. Advancement of learning designs (ALD).

Particular attention was paid to confirming the interpretation of observations (ecological validity) at both individual and group levels (see ). Adjacent to each observation, respondent confirmation of the interpretation and visual presentations of observations were sought for validity (Miles et al., Citation2014). In addition, group-level dialogues were used to discuss interpretations and findings, which fills a function of group-level validity. Informed consent was sought before the start of the study. The informed consent forms included information about the study, data collection, use and storage of data, principles of anonymity, and respondents’ right to withdraw at any time without questions asked in line with ethical guidelines (Ess, Citation2016; Hermerén, Citation2011). No respondent withdrew.

4. Results

4.1. What are some innovative elements in synchronous and asynchronous L2 LDs?

During the observations, twelve elements of teaching practices were seen to influence student engagement in ESL and SSL online classes. These are here referred to as the Advancement of Learning Design (ALD) (see ). The numbers 1–12 are used to identify the LD and do not reflect the ranking of the elements.

The teachers would often demonstrate different ALD elements, but no teacher demonstrated all ALD elements (Appendix C). It should be noted that, given the situation, demonstration ALD elements may not be in line with the learning situation, as in the case of an exam. Even with the technologies of today, it was observed that teachers might choose a traditional way of teaching, where synchronous elements, interaction, and differentiation, which may seem more demanding technically, are excluded.

4.2. How do teachers rate the identified elements in terms of importance?

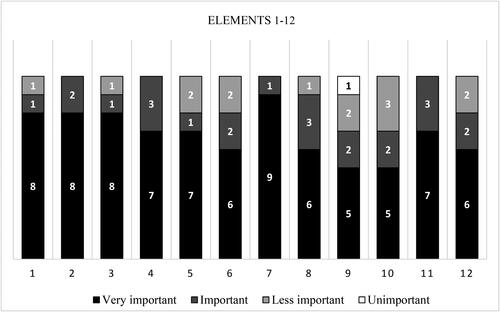

After completing the observations and collating the identified elements, the teachers were asked to rate how important it was to have the ability to implement them using a four-graded scale (ranging from Unimportant and Less important to Important and Very important) (see ). Teachers were informed, however, that having the ability does not mean the element should be or is suitable for inclusion in all learning situations.

(and ) shows that when rating the importance of ability, teachers reported the following four elements as Very important: no. 1, ‘To include practices on speaking, listening, writing and reading during one learning situation; no. 2’, ‘To design shorter learning sequences that frame and scaffold asynchronous learning to provide structural support, for example through nudges’; no. 3, ‘To combine 2–3 multimodal expressions that support communication, i.e. teacher verbal and written instruction, speech and spelling, visuals, and audio, to support understanding’; and no. 7, ‘To intentionally combine digital and physical resources during one learning situation’ (see ). In addition, the teachers rated the following elements and foci as Important: no. 4, ‘To combine synchronous and asynchronous elements in individual learning activities during one learning situation’; and no. 11, ‘To support all nuances of behavioural, cognitive, emotional, and social engagement in one learning situation’. In sum, the teachers rated all elements as important or very important (and none of the elements as rated unimportant). Moreover, half of the elements were more important than the others. Importantly, supporting learner engagement was considered a priority both in no. 6 and no. 11. On the other hand, no. 9, ‘To group and re-group learners by, for example, dividing learners into groups based on interest or focus on allowing for personalisation’ and no. 10, ‘To support engagement in ways other than those the educational mode stimulates (i.e. social engagement in asynchronous learning and emotional engagement in synchronous learning)’ were regarded as the least important. It seems unclear why supporting nuances within dimensions should be more important than supporting different dimensions of engagement altogether, but one reason could be that, for example, in asynchronous learning, a dominant focus on the cognitive dimension has been identified (Bergdahl & Gyllander-Torkildsen, Citation2022) where some teachers facilitated four nuances of cognitive engagement. This can be understood in relation to offering varied learning and is easier to accomplish than supporting social engagement asynchronously. In this regard, it is interesting to know that during observations only one (SDE) teacher was observed to facilitate all engagement dimensions and one (ADE) teacher successfully established a socially shared regulation for a group of learners (ibid.).

Table 3. Grouped responses.

4.3. How do teachers rate the identified elements in terms of difficulty to implement, building on their own ability?

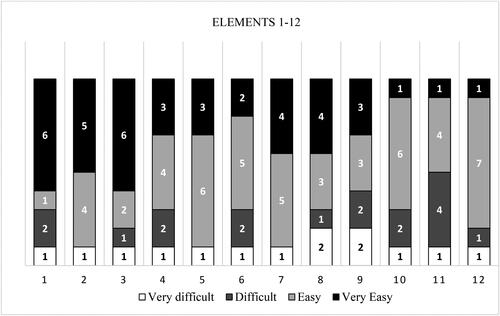

The teachers rated how difficult the elements would be to implement based on their own ability (see ) using a four-graded scale (ranging from Very difficult and Difficult to Easy and Very easy).

(and ) show that many teachers classified several elements as Easy or Very easy. However, in identifying potential needs for development, it is critical to review those elements that some teachers reported as Difficult or Very difficult as well as those unobserved elements considered Easy or Very easy (if also considered important). Half of the teachers reported that no. 11, ‘To support nuances of engagement within the behavioural, cognitive, emotional and social dimensions in one learning situation’ was Very difficult/Difficult. Two other elements were also reported as difficult, namely no. 9 ‘To group and re-group learners by, for example, dividing learners into groups based on interest or focusing on allowing for personalisation’ and no. 8, ‘To manage parallel activities: i.e. individual work and support for learners in need’. In addition, three or more teachers expressed challenges with seven of the twelve elements, and at least one teacher reported struggling with all of them. These can be compared to No. 2 ‘To design for shorter learning sequences that frame and scaffold asynchronous learning to provide structural support, for example, through nudges’., no.5 ‘Facilitation of interaction’, and no. 7 ‘To intentionally combine digital and physical resources during one learning situation’. Which were rated the easiest.

In matching the rate of importance to the reported difficulties in providing the element, a comparison of self-reports reveals that certain elements were found by teachers to be both important and easy, such as no. 2, ‘To design for shorter learning sequences that frame and scaffold asynchronous learning to provide structural support, for example through nudges’ and no. 7, ‘To intentionally combine digital and physical resources during one learning situation’.

In addition, some elements that were reported to be difficult were also rated as less important: no. 9, ‘To group and re-group learners by, for example dividing learners into groups based on interest or focusing on allowing for personalisation’ and no. 10, ‘To support engagement in ways other than those the educational mode stimulates (i.e. social engagement in asynchronous learning, and emotional engagement in synchronous learning)’. One interpretation of this could be that the more one does something, the easier one may perceive it to be. If the element is not prioritised, it may be thought of as a less valuable ability. Alternatively, it could also be that because some elements were perceived as harder, a reluctance to include them could be supported by the rational rejection ‘they are of less importance’. Interestingly, teachers reported that both no. 8, ‘To manage parallel activities: i.e. individual work and support for learners in need’ and no. 11, ‘To support nuances of engagement within the behavioural, cognitive, emotional and social dimensions in one learning situation’ were important and challenging. Such cross-findings can influence the direction of professional development.

Some elements such as no. 1, ‘To include practices on speaking, listening, writing and reading during one learning situation’, no. 4 ‘To combine synchronous and asynchronous elements in individual learning activities during one learning situation’ and no. 6 ‘To support all dimensions of learner engagement in one learning situation’ were rated as important and yet medium-hard. Furthermore, the results also show that even though digital creation (no.12) was rated as important, there are many other elements for teachers to consider prioritising.

The teachers demonstrated (Appendix C) and reported () that it was hard but important to facilitate nuances of engagement in their designs. Interestingly and somewhat contradictorily, teachers reported that stimulating dimensions of engagement were important and not as hard (still, three teachers reported this as hard). The observations (and follow-up interviews) revealed that only three teachers demonstrated stimulating all dimensions of engagement in their designs (even when combining the observations for each case) (See Appendix C). To support language acquisition, here understood as practising all four skills during one learning situation, was considered Very important/important and Easy/Very easy by the majority. However, as many as three teachers believed that this was a challenge, and this was not demonstrated extensively in the observations (See Appendix C). Similarly, ‘Scaffolding’ was reported as easy and important, but designing asynchronous learning activities in ways that clearly frame the tasks and provide sequences to the learner was very rare. Moreover, differentiated learning symbolises something interesting, although this was hardly demonstrated during the observations, which is reflected in its being rated the second most difficult element to implement. However, surprisingly, it was also one of the elements considered least important, together with overcoming the hindrances of the mode of delivery. Finally, reveals that several teachers report struggling with the four elements that all teachers rated as the most important, while Appendix C reveals that most elements were not observed in most demonstrations. Instead, several elements tended to be clustered with certain individuals.

5. Discussion

5.1. What are some innovative elements in synchronous and asynchronous L2 LDs? How do teachers rate the identified elements in terms of importance and in terms of difficulty to implement, building on their own ability?

Building on the research of Ernest et al. (Citation2013), who suggest that HE teachers prioritised learning by using synchronous and asynchronous tools, this study extends their results by adding inductively informed aims when using such tools, e.g. ‘To combine synchronous and asynchronous elements in individual learning activities during one learning situation’ and ‘To use synchronous and asynchronous elements to facilitate interaction’. These were not observed by all teachers and were yet seen to support engagement and learning. However, the teachers in this study did not rate these as the most difficult. During observation, differences concerning how digital technologies were employed to support individual and collaborative learning activities were detected, and LD is one of the tools through which teachers can foster engagement (Engle & Conant, Citation2002; Mejia, Citation2020; Vuopala et al., Citation2014). Without the qualitative aspects (or the know-how) of technology use to support learners (Conole, Citation2012; Mor & Craft, Citation2012), learning activities would merely be a checklist of activities with little information on elements used to provide varying and engaging activities. The results show that teachers found it to be most challenging to engage learners in varied ways, offer scaffolding, differentiation, and parallel learning activities. Engagement differs between learners (Khalil & Ebner, Citation2017; Sinha et al., Citation2014) but is critical for learning (Bergdahl et al., Citation2020; Fredricks et al., Citation2004; Fredricks et al., Citation2016). Hence, this study argues that different dimensions of engagement must be stimulated regardless of the mode of learning. Expanding on the results of Dohn et al. (Citation2019), the findings here indicate additional complexity in relation to designs for engagement. For example, the teachers reported that the most important and difficult element was to ‘facilitate nuances of engagement’ (i.e. to support engagement in varied ways). This was reflected in teachers (n = 6) challenging the mode of delivery to overcome barriers linked to synchronous and asynchronous teaching and learning. It seems that teachers, and in particular teachers new to synchronous designs, need increased awareness of the conditions and limitations that accompany a certain mode, as well as incentives to overcome any related hindrances. In synchronous and asynchronous learning, some teachers (n = 5) provided means to group and re-group learners to support differentiation, while others did not. Half of the teachers provided multiple opportunities to practice language acquisition in writing, speaking, and listening (Peng et al., Citation2021) during one learning situation, while others were seen to reduce the ways learners could practice language acquisition, employ traditional exercises, and reduce variation and pace. Linking to previous research (Beck, Citation2019; Leijon & Juni, Citation2021), the results show that innovative LDs may reflect an awareness of spatial aspects in varied learning environments and the ability to support the student in activities that may include more complex or innovative activities, such as creating digital- or immersive learning. Amongst the LDs there were indeed a plethora of great examples with multiple types of learning activities, uses for different modalities in digital technologies, different orchestrations of digital technologies, and resources or combinations of theses, on an advanced level, including various ways to differentiate, individualise, and stimulate different kinds of engagement in learning. However, these practices were not always observed even though teachers reported that they were both important and easy. Thus, tailored professional development and collegial work could help teachers excel in their digital proficiency.

Referring to the connectivist ideas presented initially, the elements are linked to teachers’ ability, which is seen as critical in the connectivist perspective (Siemens, Citation2004). Like Rienties et al. (Citation2018), this study identified that asynchronous learning would be concentrated on assimilative, productive, and assessment types of learning activities directly linked to teachers’ LD. Lastly, expanding on the findings of From (Citation2017), the results show that several teachers report struggling with the elements that all teachers rated as the most important. If teachers cannot select the most effective or preferred LD but are limited to what they can implement in an online setting, this will affect the quality of the education provided. In line with Reinhardt and Thorne (Citation2019 and Rienties et al. (Citation2018), this study emphasises that digital competence in LD should be linked to the ability to implement qualitative elements specific to the subject taught, since categories that try to capture digital skills that apply to all may be too generic. Adopting a method similar to that presented here, the results can inform teacher progression measures, the direction for individual training priorities, professional development at the department and identity the current state of digital competence in relation to creating engaging online learning designs that support learning.

5.2. Future research

As this study is limited to exploring learning situations, future studies linking elements, learning sequences, timing, and parallel activities would expand further on the findings presented. In addition, future studies can explore the relation between elements and learning activities in CALL with learner satisfaction, retention, and outcome as design intentions that may differ from what transpires. While there are given limitations to generalisation, for example, due to a local Covid-19 outbreak, where only half of the teachers filled out the survey, the study encourages that these initial findings be tested in other settings. A connectivist perspective holds that having the ability to access and create new information is essential. However, it is not only necessary to own the skills in order to enact L2 LD, but one must also know which mode of delivery is the most effective for a specific element and learning goal (Canals, Citation2021). In addition, different learners may opt for different modes of education; thus, future research should take learner engagement profiles into account when disseminating outcomes across educational modes.

6. Conclusion

This study contributes with re-framing teaching practices in SLL post Covid-19 by identifying practices that seem novel and by suggestion a method for schools to explore emerging online learning designs. The implication of these contributions is that, up until now, there has been little subject specific guidance or support to schools in re-framing teachers’ digital competence in online learning designs post Covid-19. The presented findings expand on those of From (Citation2017; who suggested that learning designs reflect digital competence). Teachers’ digital competencies have taken a leap during the pandemic (Bergdahl, Citation2021), which makes it difficult to navigate the ‘digital competence’ or ‘high-quality adoption’ of digital technologies in education. Current research that guides the assessment of digital competence education may be too broad to support teachers in developing their online learning designs in specific subjects. Moreover, teachers may be left to run development projects locally, with limited knowledge and resources (Eriksson, Citation2020). Because digital cultures differ between schools, local approaches need to systematically survey how their practices have developed and what emerging practices can become good examples for others. This paper suggests that the presented approach may be used to systematically inform the current state of digital practice in a subject and school, thereby supporting professional development, guiding individual progression, and reframing post-pandemic teaching practices.

Disclosure statement

The author declares no competing interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nina Bergdahl

Dr. Nina Bergdahl is a Lecturer of Learning in the digitalized society at Halmstad University. She has been teaching at the Department of Education for several years and currently runs courses that equip teachers with the skills to work with learners in digital learning environments. Her research focuses on the implications of the increasing digitalisation and datafication of education on the individual and collective. Her research draws on Educational Psychology, Educational Technologies and Didactics, covering topics such as Learner Engagement, Hybrid-, Remote- and Distance Education, Telepresence Robots, Artificial Intelligence, Learning Design and Professional Development.

References

- Akiyama, Y., & Cunningham, D. J. (2018). Synthesizing the practice of SCMC-based telecollaboration: A scoping review. Calico Journal, 35(1), 49–76. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.33156

- Andersen, R., & Ponti, M. (2014). Participatory pedagogy in an open educational course: Challenges and opportunities. Distance Education, 35(2), 234–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2014.917703

- Appleton, J., Christenson, S. L., Kim, D., & Reschly, A. L. (2006). Measuring cognitive and psychological engagement: Validation of the student engagement instrument. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 427–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.002

- Asensio-Pérez, J. I., Dimitriadis, Y., Pozzi, F., Hernández-Leo, D., Prieto, L. P., Persico, D., & Villagrá-Sobrino, S. L. (2017). Towards teaching as design: Exploring the interplay between full-lifecycle learning design tooling and teacher professional development. Computers and Education, 114, 92–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.06.011

- Awuor, N. O., Weng, C., Piedad, E., & Militar, R. (2021). Teamwork competency and satisfaction in online group project-based engineering course: The cross-level moderating effect of collective efficacy and flipped instruction. Computers & Education, 176, 104357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104357

- Bauer-Ramazani, C. (2006). Training CALL teachers online. In P. Hubbard, & Michael, L (Eds.), Teacher education in CALL (pp.183–202). John Benjamins Publishers.

- Beck, D. (2019). Special issue: Augmented and virtual reality in education: Immersive learning research. Journal of Educational Computing, 57(7), 1619–1625. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633119854035

- Bergdahl, N. (2021). Emerging practices and persisting challenges—A year into distance education in upper secondary school [Paper presentation]. Proceedings in 7th International Designs for Learning Conference; Remediation of Learning, (p. 11), May 24-25, 2021, Stockholm, Sweden. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13065.98400

- Bergdahl, N., & Bond, M. (2021). Negotiating K-12 (Dis-)engagement in blended learning. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 2635–2660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10714-w

- Bergdahl, N., & Gyllander-Torkildsen, L. (2022). Analysing visual representations of adult online learning across formats [Paper presentation]. In the 24th Human Computer Interaction International Conference HCII 2022, Part II, Gothenburg, Sweden, June 26- July 1, 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13309. Springer Nature.

- Bergdahl, N., Nouri, J., Fors, U., & Knutsson, O. (2020). Engagement, disengagement and performance when learning with technologies in upper secondary school. Computers and Education, 149, 103783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103783

- Bond, M., & Bergdahl, N. (2022). Student engagement in open, distance, and digital education. In Olaf Zawacki-Richter, Insung Jung (Eds.), Handbook of open, distance and digital education (pp. 1–16). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-0351-9_79-1

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods. (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

- Butler-Pascoe, M. E., & Wiburg, K. (2003). Technology and teaching english language learners. Pearson Education.

- Canals, L. (2021). Multimodality and translanguaging in negotiation of meaning. Foreign Language Annals, 54(3), 647–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12547

- Chapelle, C. A., & Voss, E. (2016). 20 years of technology and language assessment in language learning & technology. Language Learning & Technology, 20(2), 116–128.

- Cho, M. H., Kim, Y., & Choi, D. (2017). The effect of self-regulated learning on college students’ perceptions of community of inquiry and affective outcomes in online learning. The Internet and Higher Education, 34, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.04.001

- Conole, G. (2012). Designing for learning in an open world. (Vol. 4). Springer Science & Business Media.

- Coryell, J. E., & Chlup, D. T. (2007). Implementing e-learning components with adult English language learners: Vital factors and lessons learned. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 20(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220701489333

- Creswell, J., & Clark, V. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed-methods research. (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Dillenbourg, P. (2013). Design for classroom orchestration. Computers and Education, 69, 485–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.04.013

- Dohn, N. B., Godsk, M., & Buus, L. (2019). Learning design: Approaches, cases and characteristics. [Learning Design: Tilgange, cases og karakteristika.]. Laering Og Medier (LOM), 21(June), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.7146/lom.v12i21.112639

- Ellis, N. C., & Ferreira-Junior, F. (2009). Construction learning as a function of frequency, frequency distribution, and function. The Modern Language Journal, 93, 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2009.00896.x

- Engle, R. A., & Conant, F. R. (2002). Guiding principles for fostering productive disciplinary engagement: Explaining an emergent argument in a community of learners’ classroom. Cognition and Instruction, 20(4), 399–483. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532690XCI2004_1

- Eriksson, I. (2020). Knowing what works… (Från att veta vad som fungerar…). In Åsa Hirsch and Anette Olin (Eds.). School development in theory and practices. (Skolutveckling i teori och praktik) (pp. 185–299). Gleerups.

- Ernest, P., Guitert Catasús, M., Hampel, R., Heiser, S., Hopkins, J., Murphy, L., & Stickler, U. (2013). Online teacher development: Collaborating in a virtual learning environment. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 26(4), 311–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2012.667814

- Ess, C. (2016). Digital media ethics. In A. Jung, M. Keller, & D. White (Eds.), The Oxford research encyclopaedia of communication (pp. 1–47). Oxford University Press.

- Firth, A., & Wagner, J. (2007). Second/foreign language learning as a social accomplishment: Elaborations on a reconceptualized SLA. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 800–819. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2007.00670.x

- Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

- Fredricks, J. A., Wang, M. T., Schall Linn, J., Hofkens, T. L., Sung, H., Parr, A., & Allerton, J. (2016). Using qualitative methods to develop a survey measure of math and science engagement. Learning and Instruction, 43, 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.009

- From, J. (2017). Pedagogical digital competence—Between values, knowledge and skills. Higher Education Studies, 7(2), 43. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v7n2p43

- Geeslin, K. L., Klee, C. A., & Face, T. L. (2006). Task design, discourse context and variation in second language data elicitation. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on the Acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese as First and Second Languages (pp. 74–85). Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

- González-Lloret, M., & Ortega, L. (2014). Towards technology-mediated TBLT: An introduction. In M. Gonzélez-Lloret & L. Ortega (Eds.), Technology mediated TBLT: Researching technology and tasks (pp. 1–22). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/tblt.6

- Goodyear, P. (2020). Design and co-configuration for hybrid learning: Theorising the practices of learning space design. British Journal of Educational Technology, 51(4), 1045–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12925

- Goodyear, P., & Dimitriadis, Y. (2013). In medias res: Reframing design for learning. Research in Learning Technology, 21(1), 19909. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v21i0.19909

- Greene, B. (2015). Measuring cognitive engagement with self-report scales: Reflections from over 20 years of research. Educational Psychologist, 50, 13–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.989230

- Hadwin, A. F., Järvelä, S., & Miller, M. (2018). Self-regulation, co-regulation and shared regulation in collaborative learning environments. In D. H. Schunk & J. A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (2nd ed., pp. 83–106). Routledge.

- Hampel, R., & Pleines, C. (2013). Fostering student interaction and engagement in a virtual learning environment: An investigation into activity design and implementation. Calico Journal, 30(3), 342–370. https://doi.org/10.11139/cj.30.3.342-370

- Hermerén, G. (2011). Good research practice. Swedish Research Council.

- Insulander, E., Majlesi, A. R., Rydell, M., & Svärdemo Åberg, E. (2021). Multimodal analysis of classroom interaction [Multimodal analys av klassrumsinteraktion]. Liber.

- Johnson, D., & Johnson, R. (2008). Cooperation and the use of technology. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. van Merrienboer, & M. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (3rd ed., pp. 659–670). Routledge.

- Järvelä, S., Järvenoja, H., Malmberg, J., & Hadwin, A. F. (2013). Exploring socially shared regulation in the context of collaboration. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 12, 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.12.3.267

- Kern, R. (2021). Twenty-five years of digital literacies in CALL. Language Learning & Technology, 25(3), 132–150. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/73453

- Khalil, M., & Ebner, M. (2017). Clustering patterns of engagement in Massive Open Online Courses MOOCs: The use of learning analytics to reveal student categories. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 291, 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-016-9126-9

- Kress, G. R., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2001). Multimodal discourse. The modes and media of contemporary communication. Arnold.

- Kress, G. R., & Selander, S. (2012). Multimodal design, learning and cultures of recognition. The Internet and Higher Education, 15, 265–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.12.003

- Kuropka, D., Laures, G., & Tröger, P. (2008). Core concepts and use case scenario. In D. Kuropka, S. Staab, P. Tröger, & M. Weske (Eds.), Semantic service provisioning (pp. 5–18). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-78617-7_2

- Lasry, N., Mazur, E., & Watkins, J. (2008). Peer instruction: From Harvard to the two-year college. American Journal of Physics, 76(11), 1066–1069. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.2978182

- Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as design science building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. Routledge.

- Leijon, M., Juni, T. (2021). Future Learning Environments - A research overview [Framtidens lärandemiljöer - en forskningsbaserad översikt]. Akademiska Hus, 3–42.www.akademiskahus.se/aktuellt/event/2021/kvartal-4/framtidens-larandemiljoer–ny-forsknings-presenteras/

- Li, J. (2016). The interactions between emotion, cognition, and action in the activity of assessing undergraduates’ written work. In D. S. P Gedera & J. P. Williams (Eds.), Activity theory (pp. 105–119). Brill.

- Lockyer, L., Agostinho, S., & Bennett, S. (2016). Design for e-learning. The SAGE handbook of e-learning research (pp. 336–353).

- Lockyer, L., Heathcote, E., & Dawson, S. (2013). Informing pedagogical action aligning learning analytics with learning design. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(10), 1439–1459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479367

- Loncar, M., Schams, W., & Liang, J. S. (2021). Multiple technologies, multiple sources: Trends and analyses of the literature on technology-mediated feedback for L2 English writing published from 2015-2019. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–63 (Aug, 21). https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2021.1943452

- Matthews, J., O’Toole, J. M., & Chen, S. (2017). The impact of word recognition from speech (WRS) proficiency level on interaction, task success and word learning: Design implications for CALL to develop L2 WRS. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(1–2), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2015.1129348

- Martin, A. J. (2007). Examining a multidimensional model of student motivation and engagement using a construct validation approach. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 413–440. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709906X118036

- Mejia, C. (2020). Using VoiceThread as a discussion platform to enhance student engagement in a hospitality management online course. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport and Tourism Education, 26, 100236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2019.100236

- Mežek, Š., McGrath, L., Negretti, R., & Berggren, J. (2022). Scaffolding L2 academic reading and self-regulation through task and feedback. TESOL Quarterly, 56(1), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.3018

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, M. A., & Saldana, J. (2014). Drawing and verifying conclusions. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 275–322. January 11, 2016

- Mor, Y., & Craft, B. (2012). Learning design: Reflections upon the current landscape. Research in Learning Technology, 20(SUPPL), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.3402/rlt.v20i0.19196

- Olofsson, A. D., Fransson, G., & Lindberg, J. O. (2020). A study of the use of digital technology and its conditions with a view to understanding what ‘adequate digital competence’ may mean in a national policy initiative. Educational Studies, 46(6), 727–743. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2019.1651694

- Pekarek Doehler, S. (2018). Elaborations on L2 interactional competence: The development of L2 grammar-for-interaction. Classroom Discourse, 9(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463014.2018.1437759

- Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). Academic emotions and student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 259–282). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7

- Peng, H., Jager, S., & Lowie, W. (2021). Narrative review and meta-analysis of MALL research on L2 skills. ReCALL, 33(3), 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344020000221

- Powell, A., Oliver, W. (2019). National Standards For Quality Online Teaching. In Quality Matters and Virtual Learning Leadership Alliance. www.nsqol.org.

- Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. Journal of Engineering Education, 93(3), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x

- Reeve, J., & Tseng, C.-M. (2011). Agency as a fourth aspect of students’ engagement during learning activities. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(4), 257–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.05.002

- Reeve, J., Cheon, S. H., & Jang, H.-R. (2019). A teacher-focused intervention to enhance students’ classroom engagement. Handbook of Student Engagement Interventions, 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813413-9.00007-3

- Reinhardt, J., & Thorne, S. L. (2019). Digital literacies as emergent multifarious literacies. In N. Arnold & L. Ducate (Eds.), Engaging language learners through CALL (pp. 208–239). Equinox.

- Rienties, B., Lewis, T., McFarlane, R., Nguyen, Q., & Toetenel, L. (2018). Analytics in online and offline language learning environments: The role of learning design to understand student online engagement. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31(3), 273–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1401548

- Rienties, B., Tempelaar, D., Nguyen, Q., & Littlejohn, A. (2019). Unpacking the intertemporal impact of self-regulation in a blended mathematics environment. Computers in Human Behavior, 100, 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.007

- Rosell-Aguilar, F. (2005). Task design for audiographic conferencing: Promoting beginner oral interaction in distance language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 18(5), 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220500442772

- Saito, K., & Akiyama, Y. (2017). Video-based interaction, negotiation for comprehensibility, and second language speech learning: A longitudinal study. Language Learning, 67, 43–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12184

- Selander, S. (2008). Designs of learning and the formation and transformation of knowledge in an era of globalization. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 27(4), 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-007-9068-9

- Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age Ekim, 6, 2011.

- Sinha, T., Li, N., Jermann, P., & Dillenbourg, P. (2014). Capturing" attrition intensifying"structural traits from didactic interaction sequences of MOOC learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.5887. https://doi.org/10.3115/v1/w14-4108

- Skinner, E. A., Kindermann, T. A., & Furrer, C. J. (2009). A motivational perspective on engagement and disaffection. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 69(3), 493–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164408323233

- Soleimani, F., & Lee, J. (2021 Comparative Analysis of the Feature Extraction Approaches for Predicting Learners Progress in Online Courses: MicroMasters Credential versus Traditional MOOCs [Paper presentation]. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM Conference on Learning@ Scale, (pp. 151–159). https://doi.org/10.1145/3430895.3460143

- Spolsky, B. (1989). Conditions for second language learning. Oxford University Press.

- Strang, K. (2016). How student behavior and reflective learning impact grades in online business courses. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 8(3), 390–410. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-06-2015-0048

- Stockwell, G. (2014). Exploring theory in computer-assisted language learning [Paper presentation].Alternative Pedagogies in the English Language & Communication Classroom: Selected Papers from the Fourth CELC Symposium for English Language Teachers, In (pp. 25–30).

- Sugden, N., Brunton, R., MacDonald, J., Yeo, M., & Hicks, B. (2021). Evaluating student engagement and deep learning in interactive online psychology learning activities. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 37(2), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.6632

- Sunar, A. S., Abdullah, N. A., White, S., & Davis, H. (2015 Personalization in MOOCs: A critical literature review [Paper presentation]. International Conference on Computer Supported Education, In (pp. 152–168). Springer International Publishing.

- Tempelaar, D. (2020). Supporting the less-adaptive student: The role of learning analytics, formative assessment and blended learning. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(4), 579–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1677855

- Teng, M. F. (2017). Flipping the classroom and tertiary level EFL students’ academic performance and satisfaction. Journal of Asia TEFL, 14(4), 605. https://doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2017.14.4.2.605

- Toro-Troconis, M., Alexander, J., & Frutos-Perez, M. (2019). Assessing student engagement in online programmes: Using learning design and learning analytics. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(6), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v8n6p171

- Thorpe, M. (2013). Perceptions about Time and Learning. In I. Bernath, A Szücs, A. Tait, & M. Vidal (Eds.), Distance and E-learning in transition: Learning innovation, technology and social challenges (pp. 457–472). Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118557686.CH31

- Toetenel, L., & Rienties, B. (2016). Learning design—Creative design to visualise learning activities. Open Learning, 31(3), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680513.2016.1213626

- van Aalst, J. (2013). Assessment in collaborative learning. In C. Hmelo-Silver, C. A. Chinn, C. Chan, & A. O’Donnell (Eds.), The international handbook of collaborative learning (pp. 280–296). Routledge.

- Vuopala, E., Hyvönen, P., & Eagle, S. (2014). Collaborative processes in virtual learning spaces - Does structuring make a difference? Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Vol. 7697(271–278). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-43454-3_28

- Wang, M.-T., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Adolescent behavioral, emotional, and cognitive engagement trajectories in school and their differential relations to educational success. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 22(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2011.00753.x

- Wigham, C., & Satar, M. (2021). Multimodal (inter)action analysis of task instructions in language teaching via videoconferencing: A case study. ReCALL, 33(3), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344021000070

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and method. (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Zhang, L. J., & Zhang, D. (2018). Metacognition in TESOL: Theory and practice. In J. I. Liontas & A. Shehadeh (Eds.), The TESOL encyclopaedia of English language teaching, Vol. II: Approaches and methods in English for speakers of other languages (pp. 682–792). Wiley and Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118784235.eelt0803

- Zeng, S., Zhang, J., Gao, M., Xu, K. M., & Zhang, J. (2020). Using learning analytics to understand collective attention in language MOOCs. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(7), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1825094

- Ziegler, N. (2016). Synchronous computer-mediated communication and interaction: A meta- analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 38(3), 553–586. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226311500025X

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207312909

Appendix A

Observation schema with coding of synchronous class (sample)

Appendix B

Operationalization, overview of abbreviation

These dimensions refer to teachers’ enacted learning designs