ABSTRACT

Ballroom dancing, nowadays a multibillion-dollar industry, has emerged and developed within western, (post-)industrial, (post-)modern societies. As such, its representations rely heavily on heteronormative gender performances, most of which – as shown in this paper – reiterate rape culture codes. To do so, focusing on how heteronormativity is staged and performed in Rumba, the challenging situation that dancers face is first identified. Embodying DanceSport’s aesthetic and technical norms disrupts dancers’ adequacy to the gendered symbolic order, resulting in the dire need to overstate their genders, in order to achieve a subject position. Second, the ways through which male dancers perform dominance is brought into focus. With a close textual analysis of the performance of the six best couples from the World Championship 2019 with methods such as Feminist film theory, semiotics or nonverbal communication, a range of signs, from non-reciprocal gaze and touch, through polarizing positions emphasizing male dominance and female submission, to abstracted physical violence, are identified. Here, a comparison of two couples shows how these signs are used in different manners and, most importantly, various intensities by the dancers, drawing finally, like a photo negative, a possible subversive performance, in which the partners would be equal and these signs obsolete.

1. Introduction

Considering DanceSportFootnote1 from a gender point of view, several issues might jump to mind. First, there is the competition rule stating that ‘a couple consists of a male and a female partner’ (WDSF Competition Rules, Citation2018, p. 23). Second, as I will show in this paper, the traditional gender narratives transcribed in the performance, through the choreography, reiterate rape culture codes.

A popular start in Rumba nowadays consists of the female partner standing in front of the audience, caressing herself. The male dancer, walking casually behind her, approaches and touches or even grabs her with no further notice. The Rumba performance of multiple World Champions Gabriele Goffredo and Anna Matus at Brno Open in 2014 (hiptwisted) constitutes a good example. He approaches her from behind until his chest touches her back, then thrusts his hands to her lower thighs and caresses her upwards. After grabbing her waist, he pushes her away and sharply pulls her back to him, provoking an impact of her back against his ribcage. This is an extreme example, but, considering their success, something DanceSport’s audiences (and adjudicators) want to see. Of course, there is shared knowledge that they are together (since then married), and that the choreography aims at making both partners feel safe during the performance. Nonetheless, the gender representations offered are questionable at best.

This research combines as much from my academic curiosity as from my personal engagement. As an active DanceSport competitor, I am confronted every day with injunctions to masculinity,Footnote2 which definitely have an impact on my mental and social health. Furthermore, identifying with feminist values, I do not wish to foster patriarchal heteronormative oppressive mechanisms. At the same time, I recognize the valuable contribution in multiple domains this activity made to my life.

DanceSport encourages men’s entitlement to women’s bodies, glorifies and sexualizes abstracted violence, and it does not need to – or so I will show in this paper. Considering how dancers perform heteronormativity in DanceSport, I wish to exemplify that its performance could still be very different. The competitive Ballroom industry needs to face its contradictions and address its ethical issues in order not to participate in a modernist and oppressing hegemony anymore. I focus on Rumba since it is understood in the scene as the dance of love, and I aim at showing how distorted this heterosexist vision of love is, or how sexual assault is at times coded as love in the DanceSport community.

If the intersections of (age, class,) gender and sexuality (Ericksen, Citation2011; Picart, Citation2006), the cultural appropriation process (Bosse, Citation2015; Daniel, Citation2009, Citation1995) or the participant’s involvement despite traditional gender roles (Harman, Citation2019; Leib & Bulman, Citation2009) raised continuous interest in scholarship concerned with DanceSport, the various ways with which gender and rape culture codes are implemented choreographically into performance have not been considered yet.

Along with Sanyal, I understand rape culture as ‘all social and cultural acts that trivialize, excuse or even glorify sexual violence’, as well as those encouraging male entitlement to women’s bodies (Citation2016, 119; see also Brownmiller, Citation1975). Although examples of abstracted sexual violence are seldom, the entitlement trope is common. It is enough to ask dancers to narrativize the first bars of their dance to notice it.

Constitutive of the heterosexual relationship, sexual violence is intrinsic to normative masculine or feminine identities, for instance through the ways in which ‘sexual dominance is rendered “sexy”’ (Pascoe & Hollander, Citation2016). The omnipresence of rape culture in contemporary popular culture has been already highlighted, manifesting itself through benevolent sexism, slut-shaming, representations of idealized masculinity or femininity in advertising, or in the normative gendered discourses emphasizing men as strong and impulsive and women as vulnerable and chaste (Fanghanel, Citation2019). The relationship between DanceSport and rape culture has yet to be considered.

To make my case, I rely on the one hand on close textual analyses run on Rumba performances from the six best couples of the World Championship 2019. These dance recordings, which I analysed with methods from feminist film theory, semiotics or nonverbal communication, constitute what DanceSport considers success – what younger or less successful couples aspire to and from which their inspiration is drawn. On the other hand, I relied on Grounded Theory to draw insights on what the scene expects from both genders from two hour-long qualitative expert interviews I conducted during the summer of 2018. This methodology, developed by Glaser and Strauss, is characterized by a tight entanglement of data collection, analysis and theory development, ensuring optimal alignment with reality. The generation of an object-based theory occurs through systematic collection and analysis of a wide variety of data (e.g. from interviews and observations). The process-oriented character is central to the construction of the theory, since the data are simultaneously collected, coded and analysed (theoretical sampling) (ibid.: 517). The resulting theories are in permanent and mutual confrontation and exchange with the empirical data (Lampert, Citation2005, p. 516–523).

In accordance with the ethical guidelines of the University of Graz, the interviewees have been anonymized. Participants were given project information and provided with an informed consent form. The consent form confirmed that they could withdraw from the research project at any time and have their data deleted. In addition, interviewees were provided with the interview extracts used in this publication so that they could correct or modify their statements if required. Interviewees were known to the researcher as a consequence of participation in DanceSport. Additionally, contact with more famous trainers, such as former world champions, was attempted but it was not possible to engage any of them in interview.

In the course of the paper, I will first outline the gendered cultural dynamics leading to a highly polarized heteronormative gender performance, showing why sexual assault comes to be coded as love. Second, I will describe the palette used by male dancers to perform dominance, compensating the threat felt, highlighting how concretely sexual assault is coded as love. Finally, I will picture an imaginary performance where these oppressing mechanisms would be obsolete.

2. Participation, challenge, compensation

2.1. Gender dynamics in DanceSport

Gender, so Butler states, is a performance produced by everyone and read on the medium of the body. It is ‘in no way a stable identity or locus of agency from which various acts proceed; rather, it is an identity tenuously constituted in time–an identity instituted through a stylized repetition of acts’ (Citation1988, p. 519). A specific repertoire of ‘representative symbolisms’ (dress code, facial expressions, gestures and posture) is available, but by no means arbitrary. Rather, the pre-existing historical and temporal conventions within a certain culture determine the valid symbolisms (Reuter, Citation2011, p. 86–7).

The constant repetition, or citation, of these actions produces the illusion of a stable gender identity – a fiction shared collectively, as an unspoken agreement (Butler, Citation1988, p. 522). This illusion is the product of a sedimentation (of acts, gestures), which ultimately seems to be a natural effect – something visible, considered objective (Reuter, Citation2011, p. 93).

The constraint to repeatedly materialize one’s body is accepted in order to increase one’s personal agency. The distinct attribution and performance of a gender ‘humanizes’ individuals in contemporary culture and adequately responds to the heterosexual normative process. One becomes an ‘intelligible’ subject through the process of submission to the symbolic order only, earning one’s status as a subject through performing gender (Reuter, Citation2011, p. 91).

This conceptualization of gender has several consequences. First, according to Butler, ‘gender reality is performative which means, quite simply, that it is real only to the extent that it is performed’ (Citation1988, p. 527). Formulated differently, the need for constant repetition at the same time constitutes the instability of this symbolic order. It is continually renegotiated, since a quotation does not correspond exactly to the original. A quotation too distant might remind us of the fragility of our binary gendered conception and bodily contingency, triggering social sanctions as a result. This conceptualization reminds us that gender is fundamentally unstable.

Despite operating in a subculture, the dancers and the DanceSport institution are well aware (be it only unconsciously) of the symbolic order structuring the broader culture they take part in daily: Western, (post-)industrialized, (post-)modern culture, and the expected gender performances of hegemonic masculinity and emphasized femininity (Connell, Citation1995). Yet, the technique and aesthetics expected from dancers by adjudicators and the audience do not quite align with gendered norms, for they employ characteristics traditionally associated (and essentialized) with the other gender.

This situation is very challenging, for it causes dancers to lose their intelligibility and their subject status, to endure social pressure, and suffer the sanctions associated with not performing their genders well enough. Their citation is, in Butler’s sense, too distant, reminding us of the instability of our gendered conception and bringing to our subjects’ consciousness the realm of the abject – a feminine man or a masculine woman …

Charles, an Austrian adjudicator, explained: ‘The man should be recognizable as the man, and the woman as the woman, also in the movement’s execution. It would seem rather strange if the man were very gentle and round and she very strong. [Then] the balance within the couple would be [broken]’. Social or psychological characteristics associated with femininity or masculinity constitute a social order that must not be reversed. The reproduction of this social order contributes to maintaining a balance between two dancers whose genders oppose completely, but who, for the duration of the performance, complete each other.

Dancers solve this conflict by doing ‘more’. Through compensation and over-performance, they aim at asserting their intelligibility by re-stating more clearly their belonging to their gender. On top of the technique expected of them, they display traditional gendered representative symbolisms. Niall Richardson describes this situation as follows:

Although this particular Latin movement of weight forward, toe-ball lead and locking hips and knees to create hip-movement may well give an impression of femininity this must also be paired with strong arm movements and deeply retracted shoulder blades to expand the chest and promote a peacock stance. Therefore, the official dance requirements of Latin American dancing create a surreal haemorrhaging of gender semiotics in which signifiers of hyper-masculinity are paired with signifiers of femininity […] A male Latin dancer may not stride across the floor, charging forward with a confident heel lead as this, in accordance with WDSF regulations, is incorrect technique. Instead, the young male ballroom dancer is compelled to learn a particular feminine movement (in the case of Latin this is the toe-ball lead and hip movement) and then superimpose codes of masculinity onto this. (Citation2016, p. 212-3)

Feeling the urge to belong to their gender, dancers respond with what seems to be a quotation too plain to be true. It is so accentuated, so exaggerated that it just seems fake. But the stakes are real – it is about proving that they are masculine or feminine enough.

Because of this overcompensation and of the combination of movements and gestures ‘which may be read as both male and female’ (ibid., p. 213), gender performance in DanceSport may evoke camp, as a kind of parody and caricature, drawing attention to gender performativity (ibid., p. 211). However, because the participants must justify and legitimize their practice, and render themselves intelligible, I argue that the practice is in no way intentionally camp or subversive (see Oliver & Risner, Citation2017, p. 3).

Competitive dancing performances threaten the dancers’ masculinity, femininity, and DanceSport’s couple ideal. The dynamic is similar for the three categories: Western culture sets out specific norms, which dancers partly cannot embody because of their involvement in DanceSport, so they compensate.

2.2. Masculinity

Masculinity is a heterogeneous phenomenon and takes many forms. These forms differ from each other in social inequality and are positioned in relation to the power and authority structures that permeate society. First, towards women, in the correlation between masculinity and authority, and towards men, in a hierarchy of authorities (Simonis, Citation2002, p. 277). The power relations between these different groups (men and women; men and other men) are maintained through hegemonic masculinity. Connell defines it as ‘the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees (or is taken to guarantee) the dominant position of men and the subordination of women’ (Citation1995, p. 77).

In Western culture, hegemonic masculinity glorifies self-confidence, determination, dominance, aggressiveness, superiority, authority, (physical) control, independence, competitive individualism, a requirement for performance and functionality, physical prowess, courage, economic resources, a heterosexual, decidedly homophobic behaviour and a certain misogynistic tendency. It is associated with sport, war, anger, hatred and violence (see Mühlen-Achs, Citation2003, p. 121; Messerschmidt, Citation2005; Lewis, Citation2003, p. 108).

This unattainable cultural ideal constitutes a fantasmic scale, on which men position themselves in relation to each other. The degree of compliance with male hegemony is measured by other men, via concurrence – competition for the most appropriate gender performance (Simonis, Citation2002, p. 277). This performance relies on appropriate actions, in relation to women and to other men. It relies also on symbols, objectifying or even quantifying masculinity (the type of car men drive, their ability to swallow huge quantities of alcoholic beverages, the number of sexual conquests). Yet the most important characteristic remains the performance of power and control, as Lewis describes:

Men define themselves in ways that underscore their autonomy, their ability to define situations in terms compatible with their interests. […] Masculinity is predicated on the presumption of power, whether real or imagined (Citation2003, p. 97).

Maybe even more so, since masculinity is always contested, criticized and negotiated (ibid., p. 95). Extremely unstable, it can easily be threatened. Ridicule by a woman, a public challenge, but also homosexuality, sexual dysfunction, unemployment or incarceration can be profoundly destabilizing for a man’s masculinity (ibid., p. 97). No matter what, the illusion of associating masculinity with power remains the most important. This must permeate performance for it to be judged masculine enough. The construction and masquerade of masculinity can thus be determined based on behaviours, actions, signs and attitudes, which can be observed on the body and ‘connote ways of performing powerfully’ (McDonald, Citation1997, p. 283).

In the decisive moment of the male social structure; the competition for the correct performance of his gender identity (Simonis, Citation2002, p. 277), the male dancer cannot live up to the cultural ideal of hegemonic masculinity and risks being marginalized. He is guilty of breaking with the legitimate male corporality, reduced to defined contexts such as work, sport or combat, in which the male body is not marked erotically (ibid., p. 282).

In DanceSport, the male dancer offers himself as the object of the gaze, to be looked at, using his body expressively – a position decidedly feminine (ibid.). The attention paid to appearance and the use of makeup reinforces the male dancer’s association with femininity (and thus evocation of effeminacy) (Picart, Citation2006, p. 77), as well as the (technical) expectations of the genre, in which hip actions and affected gestures are commonplace.

Western culture tells us that ‘real’ men are neither feminine, nor homosexual, nor soft (Sanyal, Citation2016, p. 134). Navigating between legitimate/illegitimate, or intelligible/impossible dichotomies, the male dancer is in the insoluble position of performatively legitimizing his masculinity in the eyes of other men (Simonis, Citation2002, p. 274). So, despite their participation in an activity associated with femininity, men’s performance on the dance floor strongly denies that they possess even an ounce of femininity (see Burt, Citation1995: 53; Gard, Citation2010, p. 108).

To retain control of the situation in the eyes of the audience (and hence not be objectified and perceived as feminine), the male dancer cannot appear as a fragmented body. Instead, it must operate as a dynamic, holistic actor, filling the space and determining its occupation (Simonis, Citation2002, p. 282). Male dance must represent control and domination over the female body and present itself through a vocabulary based on strength, speed, potency, aggressiveness, violence, or power, in movement and gesture (ibid., p. 284). As a final attempt, male dancers pair with decorous, submissive, passive, fragile, excessively feminine and sexualized female bodies to appear masculine by contrast (Richardson, Citation2016, p. 207).

2.3. Femininity

The overwhelming majority of female representations fit into two distinct categories. On the one hand, Maria, the saint, the idealized virginal love, the submissive, the good girl, the wife. On the other, Eva, or Magdalena, the evil, the red, the femme fatale, the prostitute (Klein, Citation2014, p. 25). Maria’s role ‘exhibits the passivity required by the active male subject in order to qualify as his object of desire’. The femme fatale presents a ‘threat to the male hero, through her seductiveness and her activity’. She is ‘beautiful, desirable, mysterious, ambivalent and dangerous, but also […] active and ambitious’ (van Lenning, Maas, & Leeks, Citation2001, p. 88). These constitute the two poles of a visual repertoire defining filmic and pictorial representations of women (ibid.).

The two antithetical representations of women are woven in the choreographic fabric of DanceSport. Indeed, the characteristics of Rumba comprise alternating two contradicting narratives. The trope of hesitation on the one hand is the domain of the virgin, shown through patterns of refusal and innocent chastity. This is contrasted by seduction – or the domain of the femme fatale. Choreographically, innocent chastity appears through distance variation patterns (contrast between intimately close and distant), overturns (the woman turns and steps away from the man, before he pulls her back towards him), or by sudden changes of direction. Legs open, raised, and extended towards the sky, hip oscillations, intimate positions, or turns around each other signify seduction.

Female dancers’ performance corresponds rather closely to Western culture’s definition of femininity. The disruption may happen in two ways. First, the female dancer can prove too strong, powerful, and athletic, and threaten to overshadow the male dancer’s sportiveness. Second, the balance between the good girl and the femme fatale can be disturbed and calls for a restoration. During a limited period, the female dancer may act powerfully, posing as spell caster, manipulator and seducer. She controls her male dancer, enticing him. In doing so, she embodies fully the role of femme fatale, shifting away from the good girl trope. However, keeping to this role for too long risks threatening her partner’s masculinity.

Overall, female dancers’ representation in DanceSport corresponds more closely to that of Western societies. Since dance is in Western culture associated with femininity, participating in DanceSport might feel less threatening for them than for male dancers. Indeed, overstating femininity through characteristics such as decorous, submissive, passive and fragile mostly matters to their male partners, to appear masculine by contrast.

To prevent the female dancer overshadowing the male dancer athletically, the female dancer must support the man’s sporting abilities, while showing herself vulnerable, combining strength with elegance and calmness.

Finally, whenever a female dancer acts as femme fatale, male hegemony must be restored. To achieve this, the male dancer can use abstracted violence. Sadistically, he shows her who is ‘in charge’ – a violence accepted by the female dancer, as if justified and legitimate. Second, the partners can unite in an abstraction of sexual act or marriage. The third way is through fetishism: The female dancer is presented as a precious sexual object (of status). Her flexibility, abandonment and submission are emphasized and highlighted in various positions.

Fourth and finally, performing masculine domination and female submission through a contrast in posture can restore the symbolic order. For the time of a figure, the couple assumes an inequality in positions. The woman depends on the man for stability, she reduces her height and size, leans backwards or forwards, arches her back, rotates her spine, bends her knees, finds herself locked between arms. All the while, he is either wide or high, but always straight, filling the space.

2.4. The couple

The relationship between the two partners is based on a traditional ideal of the patriarchal nuclear family. According to this trope, the man is responsible for the public sphere and production and is characteristically associated with activity. The woman, in contrast, accounts for the private sphere and reproduction and is associated with passivity.

However, according to my experts, both partners are equally active in DanceSport. This is a necessity: to allow DanceSport to develop from an athletic point of view (see Picart, Citation2006), the conservative trope according to which ‘the man leads and the woman follows’ has been neglected.Footnote3 Both partners are to be aware of the interpretation they choose to deliver to the audience, and to do their part of the job. This equal responsibility has developed over time for the partners to rely on and help each other be faster in specific movements.

The equally shared responsibility between the partners places both the male and the female dancers in contradiction to what Western culture expects of their genders. The male dancer must be attentive to the female dancer’s needs, empathetic (two values connoted feminine) while she must be assertive and active in the realization (two male values). However, although this emotional work is required for the performance to function, the product presented to the audience is decidedly traditional.

The compensation happens through neat separation of characteristics. He is bigger, faster, stronger, more stable, protective, trustworthy, takes up more space, occupies the central position around which the female dancer evolves. He initiates and controls the interaction, making her turn, holding her, interrupting her movement. She is expressive, emotional, desirable, sexualized, handled like an object …

How dance functions, then, has not much to do with what it looks like. If the practice of DanceSport must be egalitarian, the representation it produces is far from it. The balanced dance mechanisms are used to construct an illusion of masculine dominance and female subordination. The female dancer is sexually objectified and shown as vulnerable, while the male dancer takes control of the situation and the female dancer.

3. Variations in the use of masculinity signifiers

If taking part in DanceSport is threatening for most male dancers, their personal style in responding to the threat and compensating is different for each. Several tools are at their disposition to reassert their masculinity, for instance abstracted violence, unequally distributed touch and gaze (mutual or not), positions displaying a contrast in the partners’ posture, or exhibition of the female body. Furthermore, I consider that non-reciprocal prolonged gaze of one partner at the other implies power (Burgoon, Guerrero, & Floyd, Citation2010, p. 139). Mutual gaze, on the contrary, can convey respect and shared attraction (Hanna, Citation1988, p. 160).

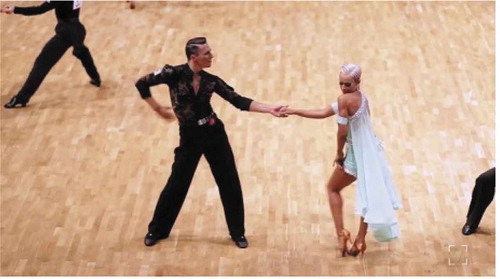

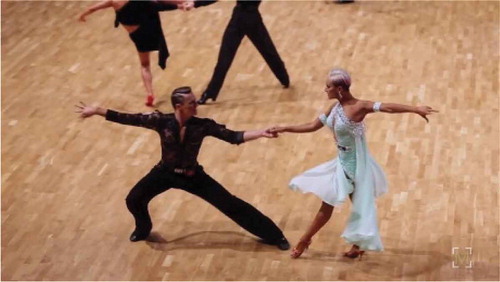

In this section, I will show how differently each of these tools can be utilized. I focus on two couples, Andrey Gusev and Vera Bondareva, and Marius-Andrei Balan and Khrystyna Moshenska. Their contrast exemplifies this difference ideally. Both Rumba performances originate from the same competition, from round three of Finland Open 2018. Both videos are available on YouTube on the channel of Marius Mutin. I thank him and his team very much for the remarkable work they do, and the permission they gave me to use their videos for this paper.

3.1. Gusev – Bondareva (Mutin, Citation2018a)

In the course of their performance, Bondareva touches his neck, his legs (but to hold on to him and prevent herself from falling at 1:04), his lower back, and his ribs. He touches her neck, shoulders and back, her belly and ribs, her head, her waist and face. He is more permissive than her, which indicates that he considers her his property, enough to touch her as and when he wants.

Concerning non-reciprocal gaze, she only looks at him once, while he looks at her four times. This inequality indicates to the audience that she is the one to look at, the object of desire and attention. Gusev looks at the audience repeatedly with defiance, while Bondareva remains more compliant, smiling on several long occasions. Through this, they suggest that she, not him, is to be objectified by the audience.

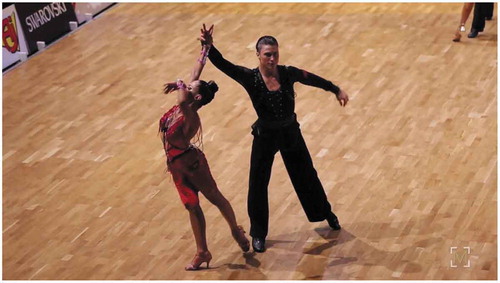

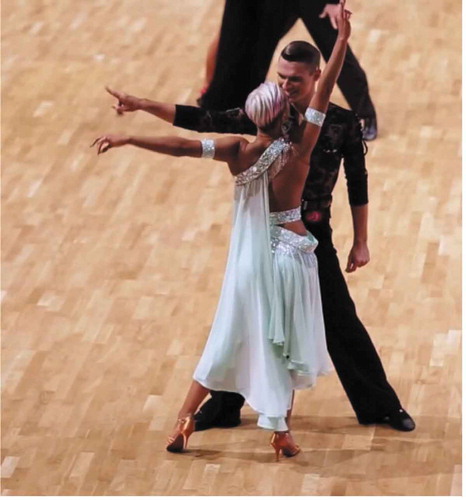

Gusev and Bondareva’s performance is overloaded with contrasting positions. In the start position (), Gusev closes his fist while looking at Bondareva, full of desire. In this position, her legs are bent, while he stands tall behind her.

On , his legs are also stretched. He is high on his toes, reaching towards the sky, while she ‘sits’ knees bent, in an entangled and arched position.

The next position () could be understood as a reversal, since Bondareva is upright and he is in a split. However, he occupies space while she is constrained by the arm behind her back. Splits permit male dancers throughout the choreography to indicate direction to female dancers.

The fourth figure () captures his movement to stop her momentum as she passes in front of him.

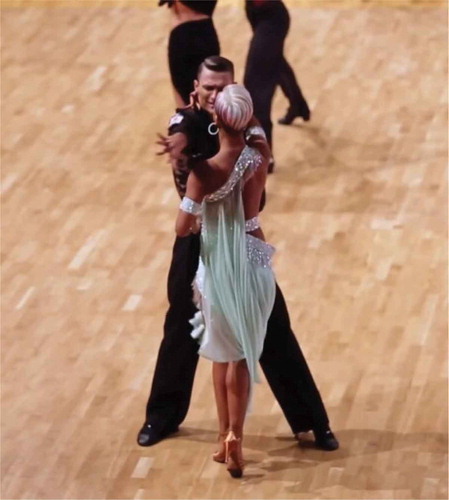

The next displays Bondareva exposed to the audience by Gusev. From 0:54 to 1:02, he orientates her inclination and rotation. She tilts backwards, offered to his and the public’s gaze. Although her feet touch the ground, her balance depends on his grip. She is displayed as an expensive object, reduced to her beauty and availability.

represents her fall between his legs. Shortly after, Gusev bends towards her and kisses her. Here too, she holds onto him while he is in a very stable position, legs wide apart and leaning over her, while she is prostrated near the ground and must tilt her neck up to see and kiss him.

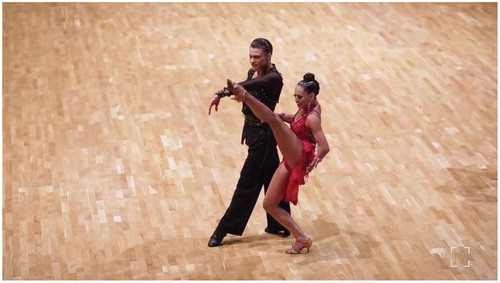

On we can see Bondareva lifting her leg gradually. To ensure her stability, she must gure further prevents her from keeping her standing leg straight, which reduces her size compared to him. This figure also ensures her sexual availability. She reveals her private parts to a large proportion of the audience, by circling her foot over her head, from front to side.

shows Bondareva in an overbalance that narrows her size, while also ensuring her dependence on him for stability.

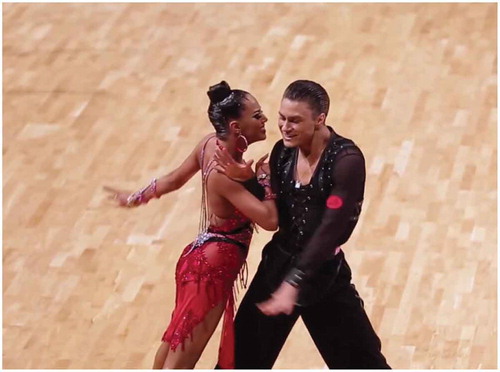

The following – illustrate the sequence of movements from 1:38 to 1:45 during which Bondareva leans backwards, then straightens up and leans towards him before he violently pushes her away.

For a short moment (), she poses as a femme fatale. She leans on him with her whole body, smiling wickedly. She looks at him directly, he sideways; her body is directly oriented to him, his is not. Her attempt to seduce him is quickly rebalanced by the violent rejection movement he has towards her (). By pushing her back, he places her in a position of sexual object, which she enhances by extending her legs and arching her back. Bondareva’s tenuous attempt to be active in her seduction is followed by his violent reminder of his dominance and her objectification.

This performance testifies to his refusal to be the object of her desire and his dedication to make her the object of his, as the unequal distribution of touch and gaze and the many contrasting positions show. He is displayed as stable, strong, and trustworthy because he supports her. In several instances, he manipulates or controls her, for example when he interrupts her at 0:45 (). At times, he handles her as if she was an object. Shortly after their position on , holding her at the waist, he pulls his left hand to his body, showing her to turn.

He objectifies the female dancer by touching her repeatedly in several places of her body. By looking at her many times, and showing a defying expression when looking at the audience, he indicates that she is the one to objectify. The female dancer as sexual object represents the reward for the male dancer’s bravery. During many figures and positions, she is shown as a sexual object, the action being interrupted many times to allow the audience to contemplate her. Her short attempt to seduce and control him, threatening his masculinity, is choreographically resolved by objectification and violence. Overall, she limits herself to the role of the good girl, making herself small and entangled to accentuate his masculinity and domination by contrast.

3.2. Balan – Moshenska (Mutin, Citation2018b)

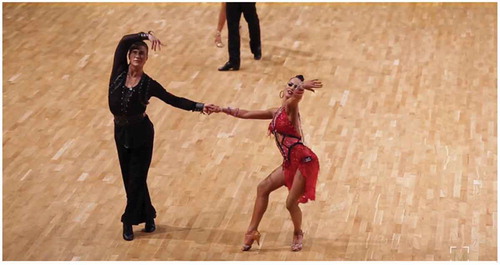

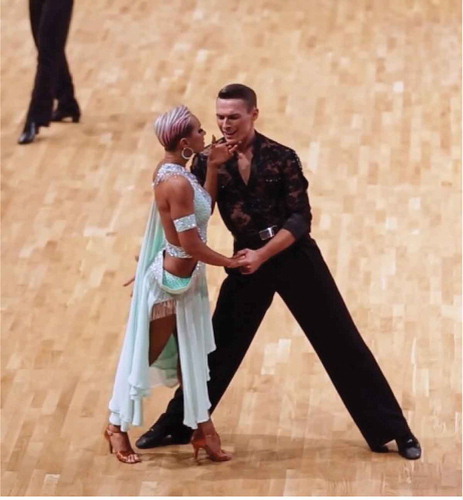

In contrast, Balan and Moshenska display more positions that emphasize reciprocity and equality in desire and agency than positions that highlight male dominance and female submission. On many occasions, their proximity and contact over a large body surface signify their intimacy, as – illustrate.

At the start of their choreography, Balan stands in front of the audience, while Moshenska looks at and approaches him (). represents the female dancer grabbing and pulling the male dancer’s chin to make him look at her, while he touches her buttocks. and illustrate additional occasions where both dancers commune in an embrace.

During this performance, Moshenska touches Balan’s torso, chin, back and belly, while he touches her neck, buttocks, head and face. Overall, he is slightly more permissive in caressing her, while her touching him often has a function: holding herself back, so for instance in .

Unlike the other couples, Balan and Moshenska show very few uneven positions.

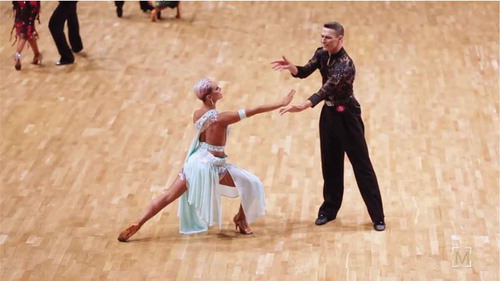

shows Moshenska straight and Balan in split. He occupies a lot of space, while she is constrained by their connection that passes behind her back – a position known from Gusev and Bondareva.

On , Moshenska executes a split from 1:07 onwards. As Balan turns and straightens up, she remains in this posture.

Finally, illustrates an idiosyncratic position of this couple – a kind of ‘signature move’. Though both of them are stretching outwards, in an impression of an abstracted sexual act, her balance fully relies on him.

Overall, this couple shows a more egalitarian performance. They display several signs of a loving behaviour, as when they caress each other’s heads at 1:14, for example. Very few positions decrease Moshenska’s size compared to Balan’s. Moshenska is rather active and communicates her agency clearly, as when she approaches him at the very beginning of their performance and turns his chin towards her.

The choreography is designed so both partners react effortlessly to each other’s movements. A good example constitutes Moshenska’s ‘hesitation’, from 0:36 to 0:38. She moves away from him, then seems to hesitate and turns around for a second. She seems caught in the throes of doubt, knees bent and hands in front of her face, while he remains straight. She makes up her mind right away and turns away from him again, this time taking more space. As soon as she turns away again, Balan turns on the spot, reacting immediately to her decision. In this instance, both of them alternately propose or react to an intention set by the other.

Over the course of the choreography, Balan asserts his masculinity in two different ways, by controlling the space and by manipulating the female dancer. Space management includes 1) positions in which he stands on wide supports, increasing the perception of his presence (at 0:59, for example), 2) the movements by which he takes up a lot of space (the opening of his arms at 1:02, at 0:38, or when he progresses towards her at 0:42), and 3) the principle of centrality (the female dancer orbits around him, for example from 0:23 to 0:37 or at 0:48).

The above series exemplifies the second aspect, the manipulation of the female dancer (0:25 to 0:29, ). She closes her feet in the Fan position, then moves towards him. Through pressure in the connection, he rotates her on her standing leg, then moves away from her to the side and turns her again in the opposite direction. She is on the same leg all along these pivots and he manipulates her to one side and then to the other. This dynamic also takes place at 0:17.

Finally, Balan supports Moshenska several times, counterbalancing her weight. The most striking example is at 1:24 (), in which her entire weight rests on him.

Balan positions himself as active and powerful to the audience by controlling the female dancer, occupying the space, acting protectively, and showing speed and strength. However, Moshenska takes very few positions that, through contrast, highlight Balan’s masculinity. She is less sexualized, less objectified than Bondareva. She touches him (almost) as often as he touches her, with no reaction on his part required to restore his domination (unlike Gusev and Bondareva’s performance).

Moshenska displays much more agency than Bondareva and visibly initiates figures. Gusev manipulates Bondareva much more, steering her around the dance floor and exhibiting her. And finally, Gusev and Bondareva expose significantly more positions signifying male domination and female submission.

4. ‘You don’t know what love is”

My contribution takes up where Richardson (Citation2016) left off, by highlighting how gender performance and rape culture codes transpire into the choreographic fabric of DanceSport. By participating in DanceSport, both men and women embody characteristics essentialized with the other gender. This situation threatens their participation in the gendered symbolic order. This is especially true for male dancers, since dance is in Western culture considered a feminine activity, and they deviate heavily from performing hegemonic masculinity. Dancers, doing their best to assure their gender belonging and escape social sanctions, over-perform by resorting to a myriad of signs, gestures and symbols.

The intersection of the dancers’ compulsive need to affirm their gender and the scene’s expectation to witness a touching love story plays out strangely, sexualizing female dancers and violent acts against them. Steering the female dancer around, violently pushing her away, insistently looking at her or touching her, ensuring her balance, exhibiting her or producing visual contrasts in size or use of space are all choreographic ways for male dancers to reassert their masculinity. This bodily behaviour is encouraged by an ideology conditioning all practitioners of DanceSport, persuading them that this is a laudable goal to achieve and with which to identify.

Rumba is described as the dance of love. This narrative is omnipresent, feeding our phantasies, weaving into personal narratives, permeating dancers from their very first lessons. But what kind of love is that? To degrade one’s partner, to sexualize and objectify her, are these signs of love? Is compulsively dominating one’s partner love? The heterosexuality represented in DanceSport is part of a broader (bodily) discourse, which constitutes the subjects and their desires. A discourse telling of a woman-object and a man entitled to her body. A discourse that is comfortably anchored in the culture of rape, legitimizing and sexualizing violence against women. Gusev and Bondareva embody this performance exemplarily.

A performance based on hierarchy, on a compulsive need to be reassured of one’s acceptability in expressing one’s gender, can express only a distorted vision of love. The reflexive questions participants in DanceSport need to ask themselves are: what kind of love do they want to show? What kind of love do they want to see? Is a partnership designed to compensate normative shortcomings through dominance all ‘love’ is about?

Considering all six couples reaching the finals of the World Championships in 2018 and 2019, Gusev and Bondareva’s way seems to be the consensus, although on the more extreme end of the spectrum. However, I have shown that there is room for manoeuvre, for subversion. Balan and Moshenska display significantly more female agency, and less contrast in body language and postures signifying female submission and male dominance. Imagine, for a second, that DanceSport would evolve further in this direction … The vocabulary constitutive of DanceSport has evolved so drastically since the 1960s, as anyone comparing performances from various periods could notice. Why would it not again?

What if DanceSport aimed at showing a different kind of love, a more reciprocal one? What if both partners were equal not only in the movement’s execution but also in the gender representation? What if there were no need to assert dominance through contrasts in positions, through exhibition of a sexualized female dancer? What if we could witness a performance closer to complex, diverse real-life experiences, where the female partner initiates as much as, or even more than, the male partner? Where he doesn’t need violence each time she seduces him? Where he can also rest, rely on her, and trust her? Where she can set boundaries? Reciprocity, trust, vulnerability might bring more tears to people’s eyes than dominance and submission – I know they would for me.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Valentin Meneau

After completing two Masters Degrees, in Musicology and Gender Studies, Valentin Meneau registered for a PhD in Dance Studies at the University of Salzburg. His topic of interest starting with his first Masters was DanceSport. Being himself an active competitor, social research satisfied his need to confront the contradictions he was irritated by in his daily practice. In Musicology, he researched the performance of musicality in the Slow Foxtrot. For his thesis in Gender Studies, he focused on choreographed gendered narratives in the Rumba. He has presented his findings to various international conferences. In his current research, he aims to establish a genealogy of female hypersexualization in Latin American competitive dancing. To do so, a scholarship has been awarded to him by the Austrian Academy of Science . Meneau is a native of France and currently lives in Austria.

Notes

1. DanceSport is the competitive form of ballroom dancing, comprising two branches, Latin American, and Ballroom. The object of my research, the former branch, includes Samba, Chachacha, Rumba, Paso Doble, Jive.

2. Comments about what a man should do or be or look like or act are extremely common during private lessons or group lessons, mostly as demarcation to femininity and said in a normative manner. It is a corrective statement, indicating what movement is right or wrong (i.e. feminine) for a male dancer.

3. Relics are still to be found, in the position of the hands, the concept of lead/follow itself, the visually causal choreographic relationship between the partners. For instance, in Back Basic, he steps towards her, communicating to her by his energy and physical pressure that she must move back, driving her away from her foot and place.

References

- Bosse, J. (2015). Becoming beautiful: Ballroom dance in the American heartland. Urbana, USA: University of Illinois Press.

- Brownmiller, S. (1975). Against our will. Men, women, and rape. Fawcett New York, USA:Columbine.

- Burgoon, J., Guerrero, L., & Floyd, K. (2010). Nonverbal communication. London, UK: Pearson Education.

- Burt, R. (1995). The male dancer. London, UK: Routledge.

- Butler, J. (1988, December). Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. Theater Journal, 40(4), 519–531.

- Connell, R. (1995). Masculinities. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press.

- Daniel, Y. (1995). Rumba: Dance and social change in contemporary Cuba. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, USA.

- Daniel, Y. (2009). Rumba then and now: Quindembo. In J. Malnig (Ed.), Ballroom, boogie, shimmy sham, shake: A social and popular dance reader, 146–165. Urbana, USA: University of Illinois Press.

- Ericksen, J. (2011). Dance with me: Ballroom dancing and the promise of instant intimacy. New York, USA: NYU Press.

- Fanghanel, A. (2019). Disrupting rape culture. Public space, sexuality and revolt. Bristol, UK: Bristol University Press.

- Gard, M. (2010). Moving and belonging: Dance, sport and sexuality. Sex Education: Sexuality, Society and Learning, 3(2), 105–118. Routledge.

- Hanna, J. L. (1988). Dance, sex and gender. Signs of identity, dominance, defiance, and desire. Chicago, USA: University of Chicago Press.

- Harman, V. (2019). The sexual politics of ballroom dancing. London, UK: Palgrave McMillan.

- Hiptwisted. (2014). Gabriele Goffredo—Anna Matus, Brno open 2014, WDSF WO latin, semifinal—Rumba. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cE76ghvZ4ns

- Klein, G. (2014). Tanz als Aufführung des Sozialen. Zum Verhältnis von Gesellschaftsordnung und tänzerischer Praxis. In M. Bischof & C. Rosini (Eds.), Konzepte der Tanzkultur. Wissen und Wege der Tanzforschung, 125–145. transcript, Bielefeld, Germany.

- Lampert, C. (2005). Grounded theory. In L. Mikos & C. Wegener (Eds.), Qualitative Medienforschung: Ein Handbuch, 596–605. Stuttgart, Germany: UTB.

- Leib, A., & Bulman, R. (2009). The choreography of gender. Masculinity, femininity, and the complex dance of identity in the ballroom. Men and Masculinities, 11(5), 602–621. Sage Publications.

- Lewis, L. (2003). The culture of gender & sexuality in the Caribbean. Gainesville, USA: University Press of Florida.

- McDonald, P. (1997). The male body in take that videos. In S. Whiteley (Ed.), Sexing the groove. Popular music and gender. London, UK: Routledge.

- Messerschmidt, J. (2005). Flesh and blood. Adolescent gender diversity and violence. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, USA.

- Mühlen-Achs, G. (2003). Wer führt? Körpersprache und die Ordnung der Geschlechter. Munich, Germany: Verlag Frauenoffensive.

- Mutin, M. (2018a). Andrey Gusev – Vera Bondareva, RUS | Finland Open 2018 – GS LAT – R3 R. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dzCx_3VpQp4

- Mutin, M. (2018b). Marius Andrei Balan – Khrystyna Moshenska, GER | Finland Open 2018 – GS LAT – R3 R. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=les3GXijEcQ

- Oliver, W., & Risner, D. (2017). Dance and gender: An evidence-based approach. Gainesville, USA: University Press of Florida.

- Pascoe, C., & Hollander, J. (2016, February). Good guys don’t rape. Gender, domination, and mobilizing rape. Gender and Society, 30(1), 67–79.

- Picart, C. (2006). From ballroom to dancesport: Aesthetics, athletics, and body culture. New York, NY: SUNY.

- Reuter, J. (2011). Geschlecht und Körper. Studien zur Materialität und Inszenierung gesellschaftlicher Wirklichkeit. transcript, Bielefeld, Germany.

- Richardson, N. (2016). ‘Whether you are gay or straight, I don’t like to see effeminate dancing’: Effeminophobia in performance-level ballroom dance. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(2), 207–219.

- Sanyal, M. (2016). Vergewaltigung. Aspekte eines Verbrechens. Nautilus, Hamburg, Germany.

- Simonis, T. (2002). Zwischen (Ohn)macht und Begehren: Männlichkeitsinszenierungen im populären Tanzfilm. In G. Klein & C. Zipprich (Eds.), Tanz, Theorie, Text, 273–289. LIT, Münster, Germany.

- van Lenning, A., Maas, S., & Leeks, W. (2001). Is womanliness nothing but a masquerade? An analysis of the crying game. In E. Tseëlon (Ed.), Masquerade and identities. Essays on gender, sexuality and marginality, 83–101. London, UK: Routledge.

- World DanceSport Federation. (2018). WDSF competition rules. Lausanne, Switzerland: AGM Lausanne.