ABSTRACT

With this paper, we participate in the body of work seeking to develop ethically sustainable practices for addressing gender, sexuality and power in pre-teen peer cultures in an inclusive, non-normative and transformative manner. To do so, we draw on feminist new materialist and posthuman scholarship and a series of events from our school-based creative workshops with 10–12-year-old children. First, by analysing the gendered flows of forces of the workshop, we demonstrate how educational and research interventions on gender are entangled and fraught with heteronormative flows of force that circulate in peer cultures. Second, we argue that composing conditions for gender to be explored and addressed cannot be based on assumptions about how gender should matter when working with children but on how it does matter in the materially situated, affective and historically contingent practices of engagement. To achieve that aim, the paper proposes to ‘work in-tensionally’ to construct ‘ethically enabling conditions’ for school-based research and education on pre-teen gender and sexual cultures.

Introduction

In academic papers that report on educational research and praxis carried out with children, the issue of gender is often resolved with a reference to the self-identification of the research participants or bypassing the issue with references to ‘children’ or ‘pupils’. Gender is either a variable or a non-issue that is not subject to closer scrutiny. In the present study, by contrast, we delve deeply into the issue of gender to offer a more nuanced contemplation of the differential matterings of gender in the context of methodologies and pedagogies to explore and address gender with 10–12-year-old children.

Existing research shows how school-based practices for addressing gender are affective and not always inclusive but still imperative to support positive peer relations and relationship cultures (Allen & Rasmussen, Citation2017; Coll et al., Citation2018; Kearney et al., Citation2016). Critics have pointed to the persistent resort to gender and heteronormativity – such as focusing only on girls and boys or a gender-blind grouping of boys and girls – and the lack of attention to gender and sexual diversity in existing gender and sexuality education (Bragg et al., Citation2018). The aim of developing inclusive, anti-discriminatory and empowering gender and sexuality education for the primary school years by refraining from repeating normative girl–boy assumptions is easy to support. However, working in practice with children quickly reveals the complexities in the ways that normative gender operates as part of the methodological and pedagogical entanglements that ensue when children engage in exploring gender and sexual pre-teen cultures.

This has also been true for us. Since the latter half of 2010s, inspired by increased research invested in new materialist creative and arts-based methodologies (E. Renold, Citation2018; Hickey-Moody et al., Citation2021; Osgood & Giugni, Citation2015; Tumanyan & Huuki, Citation2020), we have worked co-productively with primary school children to explore gender and sexuality in children’s peer cultures, including abuses of power such as sexual harassment and gender violence (Huuki, Citation2019; Huuki et al., Citation2021; Pihkala & Huuki, Citation2019; Pihkala et al., Citationforthcoming). This has entailed diverse arts-based workshops planned and implemented with varying combinations of artists, scholars, educators and children. More than 200 children aged 10 to 12 have participated in these workshops to communicate their experiences on peer cultures, resistance to oppressive practices and visions for transformative ethically sustainable relationalities. These workshops have regularly become swarmed with ordinary affects (Stewart, Citation2007) of gendered peer cultures: a nervous giggle, fidgeting bodies, anticipatory silence or other affectively intensive and sometimes unpredictable behaviours that sweep over when sensitive and rarely addressed topics of gender and ‘liking’ or ‘crushes’ are raised (Coll et al., Citation2018; Pihkala & Huuki, Citation2019). Sometimes a topic has palpably increased the attention level among the children. In another occurrence, the making has been raised to new heights when experiences of hurt transform into feminist activist statements (e.g. Huuki et al., Citation2021). These are all familiar to us from working with children, as are the gendered normative regulatory undercurrents that affect and effect what one can say, how one can move, and how and where one can be. They are part and parcel of our workshops and resonate across a wide range of encounters with children beyond those workshops. Nonetheless, existing studies and feminist praxis have thus far focused mostly on showing the problematics of gendered practices such as the gender divide and displayed less interest in complicating gendered subject positions. Moreover, they have rarely gone beyond critique to explore further how intra-active dynamisms (Barad, Citation2007) of particular situated gendered bodies, practices and discourses, or what we call gendered flows of force, co-constitute conditions for gender to be productively explored and addressed with children.

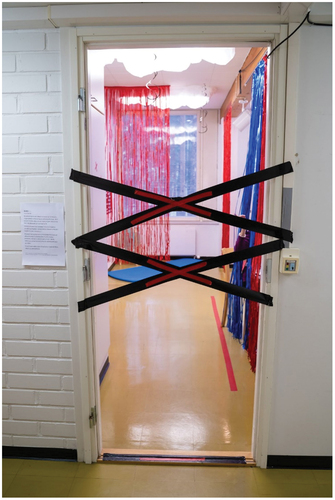

Prompted by these experiences and motivated by that gap, the present study’s aim is to examine the gendered flows of force within research and educational interventions on gender with pre-teen children. To do so, we draw on feminist new materialist and posthuman scholarship (Barad, Citation2007; Braidotti, Citation2013; Manning, Citation2016) to analyse a series of events from one of our school-based creative workshops on gender and sexual abuses of power in pre-teen peer cultures. Gender materialized in unanticipated ways in this workshop: As a result of the atmosphere unexpectedly turning uncontainable, we ended up splitting the participants into two groups – assumed boys and girls – and marking one of the rooms with a duct-taped X to ensure that the group of girls could work. The events that led us to work against our attempt to avoid binary gender divisions helped us ‘stay with the trouble’ (Haraway, Citation2016) and called on us to attend to the gendered flows of force so as to find response-able (Barad, Citation2007; Haraway, Citation2016 see also Strom et al., Citation2019) ways of working with children.

The present study makes a twofold contribution. First, we demonstrate how educational and research interventions on gender and sexual peer cultures are entangled and fraught with heteronormative flows that affect the ways children come to inhabit their bodies and how possibilities of addressing and communicating experience of hurt, resistance, and ethical visions can emerge. Second, we argue that ensuring conditions for sensitive issues such as gender in peer cultures to be explored and addressed cannot be based on pre-defined assumptions about how gender should matter when working with children. Instead, it should be based on careful and response-able engagement with how it matters in the materially, affectively and historically specific formations of methods, schools, children and peer cultures. Research and educational practice on gender is always in the middle, folded into the ambiguities, exhaustion and hurt of the past while committed to the desire for affirmative futures. Taking this seriously, we demonstrate the difficulties and benefits of ‘working in-tensionally’ to construct ‘ethically enabling conditions’ for school-based research and education on children’s gender and sexual peer cultures.

Gender, sexuality and schooling

Along with wider debates on gender and sexuality at school, in the Finnish context, schools have increasingly been called on to address issues of gender and sexuality and to support equality through systematic equality planning and gender sensitive pedagogical practices inclusive of gender and sexual diversity. These have been important steps on the levels of policy (The Act on Equality between Women and Men [609/Citationundefined], 1986) and the national core curriculum (Finnish National Board of Education, Citation2016) in that they give clear injunctions to dissolve gender segregation and develop systematic practices that address issues of sexuality, gender identity and equality.

Nevertheless, research has demonstrated since 1990s the multiple and contradictory ways in which children engage with their local school-based gendering practices, highlighting the gendered power relations at play in the production of heterosexual hierarchies (E. Renold, Citation2013; Saltmarsh et al., Citation2012; Thorne, Citation1993). Children have reported on gendered and sexual injustices and abuses of power such as harassment, everyday sexism and non-belonging (E. Renold, Citation2013; Pihkala & Huuki, Citation2019). Simultaneously, scholars have begun to explore the diverse ways that children make sense of gender and sexuality, showing that gender in children’s lives is fluid and emergent. They have shown children – along with a range of material and discursive forces (Barad, Citation2007) – as participating in crafting meanings, navigating gender categories and transgressing and engaging with alternative, more ethically sustainable visions for their peer cultures (Allen & Rasmussen, Citation2017; Bragg et al., Citation2018; Coll et al., Citation2018; E. Renold, Citation2013, Citation2018; Huuki, Citation2019). They have illustrated how gender fluidity and transformative visions can emerge in settings that leave room for them to do so.

There are thus heteronormative flows of force circulating in children’s lives that require them to reconcile and work with the cross-pull of those expectations on the one hand and the desires for more expansive gendered and sexual subjectivities on the other (Bragg et al., Citation2018). This creates a contradiction – or tension – in children’s everyday lives that cannot be addressed if the co-existence of the two is ignored or if the practices we employ jump straight to assuming equality and inclusion without accounting for the material, historical and affective conditions of children’s day-to-day lives.

Creative new materialist methodologies for addressing gender and sexual cultures

To tap into the tensions that can arise when working with such contradictory flows of force, we find it useful to invoke the emerging materialist arts-based methodologies that have approached gender in children and young people’s everyday lives (E. Renold, Citation2018; Huuki, Citation2019; Osgood & Giugni, Citation2015; Taylor, Citation2013). This work has shifted attention from bodies and objects as distinct entities to ‘intra-active entanglements’ of human and other-than-human bodies through which ‘matter comes to matter’ (Barad, Citation2007). In this line of thinking, gender in children’s lives is not a fixed property, a meaning assigned to a body or performed through discursive practices, but consists of material-discursive reconfigurings (e.g. Juelskjær, Citation2013; Taylor, Citation2013), intra-active entanglements where matter and meaning are co-constituted through an ongoing dynamism of forces (Barad, Citation2007). Attending to these flows of force helps reveal how different matterings of gender with differential affects and effects emerge in the intra-active entanglements of our creative practice. It also allows us to embrace such entanglements as sites of change (Huuki, Citation2019; Pihkala & Huuki, Citation2019; Puutio et al., Citation2021; E. Renold, Citation2018).

Methodologically and pedagogically, acknowledging gender this way has prompted inventive ways for not only engaging children in learning about gendered peer cultures in a normative framework but also for co-creating spaces where the what else and more than of gender and sexual pre-teen cultures can be explored (E. Renold, Citation2018; E. Renold & Ringrose, Citation2019 see Manning, Citation2016). This has inspired our methodology and arts-based workshopsFootnote1 to generate knowledge on and work towards just and safe young peer cultures (Pihkala et al., Citationforthcoming).

Our workshops, focused on gender and sexual relationalities, take place as part of the children’s regular schooldays, and their contents are aligned with school curricula. The workshops have been carefully constructed to afford safe and enabling conditions for children to explore issues of gender and sexuality in their peer cultures (Pihkala & Huuki, Citation2022). Safety refers to our understanding of the sensitivity of the workshops: their topics are intimately entangled with the pains, pressures and pleasures of peer relations, and the modalities and methods we employ could amplify that sensitivity by inviting the exploration of affective folds of experience. However, addressing and finding ways of exploring and transforming young peer cultures is vital. Thus, safety needs to work closely with the idea of enabling as the capacity of our creative praxis to allow for experiences to come to matter and be re-mattered, that is, how they change and how their material significance changes when, for example, experiences of hurt or harassment become statements of refusal and resistance or transformative visions in our work with children. And they are re-mattered anew when the statements and visions travel to realms of policy making and pedagogical practice.

To be safe and enabling, the materiality and making of the workshops are designed to allow issues of gender and sexual peer cultures to be approached little by little, from different angles and through multiple modalities – talking, moving, drawing, writing, crafting, sculpting and digital animations. Through this, experience can be explored, resistance to oppressive practices materialized, and ethical alternatives for peer relations envisioned and communicated. Artwork created by children then travels to new terrains as ‘activist vessels’ and pedagogical resources (Pihkala & Huuki, Citation2022; Pihkala et al., Citationforthcoming).

The composition of safe and enabling intra-action is co-constitutive of the ethical apparatus of our practice, which includes following national research ethical protocols. The research has undergone ethical review,Footnote2 with close attention paid to informing children and their legal guardians of its nature, ensuring children’s consent, and addressing issues of privacy and dignity throughout the research. Informed by the idea of response-ability (Barad, Citation2007), our ethical apparatus includes ongoing responsiveness to what our research apparatus – our choices, methods and concepts – helps bring about more than others, including the effects on gendered subjectivities (Juelskjær, Citation2013).

Analysing the gendered flows of force of creative practice

To investigate the differential matterings of gender in our creative practice, we zoom in on an event from one of our workshops. This workshop was facilitated by our team of four researchers,Footnote3 an artist, and a media producer, involved a series of creative activities over two consecutive five-hour school days and took place in a specifically reserved location: a 180 m2 multi-room space outside the immediate proximity of the participating school (for a video introducing the workshops, see https://en.fire-collective.com/showroom). The average Finnish primary school class has 20 to 30 students, so the class was divided into two groups of approximately 10 to 15 to facilitate the workshop. To organize this, the research team liaised with the class teacher. For grouping, we asked the teacher to consider whether some of the children were more caught up in the pressures of peer dynamics or invested in romantic relationship cultures. This was understood to give us important insight into the group and to be one indicator of how the themes of gender and sexuality were addressed and part of the children’s everyday lives. In addition to this general grouping, it was also our habit to work with smaller groups or individual children. This gave space to explore the issues at hand without the assumptions that all children of this age would be similarly invested in peer and relationship cultures.

For our analysis, we used researchers’ notes and audio-visual recordings from the two days with the group. This group struck us as somewhat restless, which was supported by information from the teacher. Although striking, this restlessness did not indicate exceptionality but rather resonated across our wider experiences from school, with the children reminding us of the affective atmosphere in many classes. The reason why this group caught and kept our attention was that we ended up splitting the participants in two in a manner that aligned with binary gender divisions. As this gender divide was in tension with our initial intent, it prompted us to contemplate how gender operates in the context of our workshops and how we, as researchers, might better respond to the diverse gendered flows of force in a way that would help maintain inclusive, safe and enabling conditions for children’s engagements.

The analysis unfolds through three readings that map the dynamics of gender and their differential effects and affects over the two days. The first section deals with the workshop’s first morning. Our focus here is on the normative gendered flows of force that reiteratively position bodies along the binary gender axis and materialize in a duct-taped X on the doorframe to one of the rooms to ensure a safe space for girls. In the second analytical section, we consider the intra-activating affective materiality of the duct-taped X, illuminating how working with and through the tension of this inadvertent gender divide enables a group of girls to communicate their exhaustion with boys’ dominance over the space that we understand to be firmly connected to the historically and socio-culturally specific gendered practices of children’s everyday lives at school in Finland. In the third section, we attend to the differential affects and effects of gender by focusing on the group of boys. We show how, rather than assuming solutions, working with the differential matterings of gender requires us to respond with its tensions intentionally, situationally and in an ongoing manner.

Normative gendered flows of force in creative practice with children

Our entry lobby being fairly small, the children entered the space in two groups divided by their class teacher into boys and girls. After leaving their jackets and lunches, they made their way to the opening circle in our Orange Room, sitting on the floor around a large oval plywood board. Here, the children were to settle into the space and orient themselves towards the activities to come.

As the children began to settle in a circle, four sat very close to one another. First, one settled in a back corner, then another one right next to him and yet another by the two of them. One was also claiming the space vertically by sitting on an amplifier while the others sat on the floor. The condensation of four bodies – all of whom had entered the space in the group of boys – was so tight that despite our subtle efforts to insert ourselves among them, they stuck together, as if magnetized, while the other children spread out more evenly around the oval shape. In the end, the children had settled in a manner that followed a boy–girl divide. The gendered formation of bodies not only was specific to the order they entered the space but also echoed the ways that gendered bodies inhabit space in Finnish primary schools more generally and correspond to the ways in which children have often inhabited our workshops over the years. To analyse these matterings of gender, we therefore refer in this paper to the ‘girl group’ and ‘boy group’, although without making assumptions about how any individual child might have identified.

Once settled, the orientation proceeded with line drawing, an activity of a few minutes during which children simply draw lines on the plywood in the middle of the room. As the plywood was equipped with microphones and an amplifier, the drawing was transformed into a soundscape. The soundscape soon became disruptive, as the boys in the corner started to throw crayons and pens onto the plywood. This created sharp knocking and rolling sounds that robbed the activity of attention and started to interfere with it. The disruption was produced mostly by two boys who voiced their preference to be eating lunch – only 20 minutes into the workshop and at around 9:00 am in the morning.

It did not take long for the already-confrontational knocks and lack of interest to morph into open contestation. Following the line drawing, the children convened in a circle of chairs in a separate room for the Hot Seats activity. The aim was to orient them to the topics of the workshops by exploring statements related to gendered and sexual power in peer cultures emanating from our previous workshops and fieldwork with children. After only a few rounds of warm-up statements, two boys were increasingly showing an open lack of interest. As this only made it more difficult to continue with the activity, the second author, Tuija, made the decision that those unwilling or unable to continue could leave to take a break and regroup with their usual teacher. The force of gendered peer culture worked here, as all the boys – not just the two at issue – exited, pulled in unison and reiteratively re-enforcing the habitual gender order. The girls continued behind a closed door and with an atmosphere of interest in and commitment to the activities that seemed to now have more room to flourish.

The children were then introduced to the main activity of the day, Relationship Knots, which involved crafting about experiences connected to their peer relations. The boys returned at this stage. The space had two rooms reserved for crafting. However, knowing that children often prefer to find a secluded corner for crafting in this activity, the workshop space was constructed so that children could opt for a comfortable place to work – whether by the tables set up in the rooms or on the floor, privately or in small groups. The workshop space was freely available to the children; some of the doors were even removed for easy access.

As the crafting began, an odd choreography took place: two researchers tried to ensure an enabling and safe space for the four girls who were continuing with their activities, and two other researchers were trying to facilitate the work of the other group. As Tuija was helping the girls get settled with their crafting, the restless and uninterested energy kept disrupting the making: some boys were constantly intruding, harassing, looming over the girls’ shoulders and creating a commotion despite the effort of the other team members to guide their energy towards the activities. After persistent but failed efforts to remind the children to allow the other’s the possibility to focus on their art-making, having a strong sense that what was taking place was distressing for the girls, knowing the history of gendered classroom and hassling so common in Finland, and recognizing it from our own school years and feeling its affective traces in our bodies, Tuija suggested finding a space that could ensure that the girls would be able to work. A short while later, our media producer placed a big X-sign with black duct tape across the doorway of the space where the girls were trying to work ().

It is impossible to know all that fed into the restlessness and resistance that materialized but during the morning in the Orange Room, bodies were almost literally climbing the walls – though not all the bodies. It was two of the boys who seemed to be particularly caught up in this hassling while the other boys, with more hunched postures and subdued gestures, got pulled in or perhaps ‘magnetized’ more by compulsory homosociality than investment in this disruptive behaviour, as if refusing to align oneself with this behaviour might risk one’s position and/or security in the group.

The group of boys was taking over the soundscape by talking loudly and even shouting. They claimed the physical space by climbing over material objects: sitting on an amplifier, going behind the drapery to decorate the walls and roaming and running around. Their intrusions dominated the affective space and sometimes even threatened the bodily integrity of others. The girl group, for its part, seemed to be cautious and fearful, waiting the hassle out in ‘exhausted silence’ as if frozen in place, taking up less space and adjusting themselves to the space taken up (and over) by the boys. Acknowledging that banning the boy group from the room might risk participating in the dichotomous dynamism, it was also partly in knowing the historicity of this dynamism that it felt imperative to respond by reserving for the girls a room of their own.

What occurred captures how the gendered flow of force surfaces and iterates other spaces and times (Barad, Citation2007) to enable the specific formation of gendered space and gendered subjectivities for both the ‘boy group’ and the ‘girl group’, here conforming to what is familiar and ‘as it usually is’. Bodies are ‘pulled’ in accordance with sedimented practices of historically specific, gendered relationality that had already enforced the positioning of bodies in the Orange Room – the girls there, the boys here, with the gendered subjectivities thus settling into their familiar categories, positions and postures. While this positioning underwent attempted disruptions in the form of refraining from resorting to it, this case also shows how staying with its trouble (Haraway, Citation2016), responding to it and moving with it (instead of ignoring it) might work as an affirmative situated practice.

The affective materiality of a duct-taped X: boys not welcome

With the duct-taped X in place, the children settled in to work with the Relationship Knots. A while later, the first author, Suvi, was having lunch in the kitchen and heard a commotion in the corridor. Checking what was going on, she found two children from the boy group attempting to slip under the duct-taped X into the space now assigned to the girl group while the children from the girl group voiced their disapproval. Suvi joined the chorus, shooing the children away to allow the others to continue in peace. As the children from the boy group soon left, Suvi stayed there to give the girl group the opportunity to settle back into their crafting while opening a discussion about the trespassing that had just been attempted. One of the children said that the boys were always doing that, and that – while it was annoying – there was nothing they could do about it at school. The researcher wondered whether they should write a sign with ‘Boys not welcome’ or something similar, which was taken up by a girl, who gestured at a marker in the researcher’s vicinity. Suvi contemplated what else could be done and if the girls would prefer to write the sign themselves. The notion was left at that at this point.

Initially the duct-taped X had been intended simply to ensure a calm space for the girl group to escape the others’ restlessness. However, we understand the duct tape doing more than separate a calm enclosure. It secluded the girls into some rooms while the boys were free to roam the rest of the space, it might have inadvertently invited boys to test and trespass the sign, and undoubtedly it participated in the gendered and gendering practices at play. But it also allowed a disruption. The intra-activating affective materiality of the taped X, uninvited bodies twisting to trespass its powerful signal to ban entry, the interference and hassle with the activities all en/folded in the event (Barad, Citation2007) and, rather than pulling bodies into the social habits of gendered order, the duct-taped X on the doorway became saturated with the possibility of an otherwise.

We argue that the affective materiality of the duct-taped X subtly allowed a disruption in the gendered histories of schooling that froze the girl bodies to wait their turn (the ‘good pupils’) and the gender-specific disruptiveness of the boy hassle (male privilege), which too often remains unaddressed and unspeakable (see Keller et al., Citation2018). The researchers responded to the completely obtrusive atmosphere in which two of the boys in particular were deeply caught up and into which the rest of the boys were pulled. The X seemed to shift the affective atmosphere to one that better enabled the girls to collaboratively begin to disrupt the silent patience and address male privilege. We might speculate that with the duct-taped X in place, as uninvited bodies were blocked from invading the room, exhaustion with the habitual order, irritation and a sense of safety of the atmosphere combined to render the girls – and the researchers – more capable of a response.

As the day proceeded, the children engaged with crafting. The possibility of working with craft materials eased out some of the disruptive energy of the morning even though it did not help to steer the boys’ making to the topics at hand. The girls, in turn, crafted a collaborative artwork they called ‘Strength in numbers’ (originally Joukkovoimaa in Finnish). It addressed how girls could join to resist unwanted behaviour from boys. Although it is impossible to know all that fed into the art-making, in one way or another it felt to us that this piece of art had caught some of the affects and effects of the duct-taped X on the doorway.

We cannot know how the events would have unfolded should the X have not been installed. Nonetheless, this constellation of the arts-based workshop, bodies and histories became generative of specific gendered flows of force. When addressed and responded to by this unplanned resort to a gender divide that found material articulation in the duct-taped X, it became possible for the girls to explore issues of the gendered injustices of their day-to-day school lives, if only in minor ways. The event also entangles other space-times as its force stemmed from socio-historical contingencies that extended beyond the present and opened the event to both past pains and future possibilities.

Considering the themes of the workshop, what was at stake was not only the overall commotion but also the very subject matter of gendered abuses of power we sought to address. This demands a careful construction of conditions that allow children to dwell with the abusive enfoldings of gendered peer cultures without the threat of normative gendered and sexual regulation. For example, it may in effect become impossible for girls in particular to invest in exploring gendered and sexual injustices that are entangled in boy–girl relations if they are asked to do so in the presence of the bodies and practices that enact those injustices and in a setting that is inattentive to the dynamics of normative regulations present. In our case, the space may have become safer and more enabling for the girls’ experiences to even be explored only when the situated, historically and culturally specific material-discursive gendered normative flows of force immanent to the event were answered.

The thing with the ‘boys’: differential matterings of gender

The force of the duct-taped X works as an example of how the safe and enabling conditions for exploring and addressing gender and sexuality that we strived to create risked deteriorating when the normative regulatory practices and affective histories of gender started to operate within the space. However, this is not to say that gender matterings would align with this gender divide in a linear or settled fashion. To illuminate this, we focus on the group of boys.

The boys clustering together was most striking in the mornings, when all the children convened in the Orange Room. The gendered positioning of bodies on opposite sides of the plywood gained force in the boy condensation around and on top of the amplifier positioned in the corner of the room: sitting there 50 centimetres above the floor further boosted the force of the entanglement. Similarly, it was particularly in the morning circle where it seemed as if the girls’ immediate presence magnetized the boys together, as if not permitting them to settle anywhere else. This is something that resonates more widely across our work. The moment we start to divide children into (usually two) groups, gender generates affective tension: attention heightens and materializes in the children in the form of, for example, nervous movement or rapid change of gaze and place to avoid the risk of being positioned on the ‘wrong’ side of the divide. This reminds us that within these situated practices, transgressing the gender divide risks trouble.

When the activities continued with the boys now forming one group, new kinds of gendered flows of force surfaced. Some of the boys were now distancing themselves from the boy-hassle condensation, following the hassle from the sides, withdrawing and thus becoming somewhat safe from being disturbed by the others. Being pulled in, plugging in and withdrawing from the boy group thus alternated on a moment-to-moment basis as friendship, humour, mutual play, rough and tumble – and even explicit jokes about beating up directed at one of the boys – generated ambivalent mixes of belonging and exclusion (Huuki et al., Citation2010). Here, the differential and dynamic matterings of gender remind us that working with gender cannot be based on monolithic assumptions or solutions.

Aiming to respond to these differential and dynamic matterings, instead of assuming that either a categorial gender division or a mixed-group division would have allowed for safe and enabling conditions for all, the research team worked in ways that aimed to attend to the diverse ways gendered power operates in girl–boy relations and as questions entangled in girlhoods, boyhoods and beyond. The boy group was not left at the mercy of the toxic decapacitating flows. Instead, the workshops were constructed to be responsive to the unfolding events through several arrangements steered towards safe and enabling intra-action: the children would be divided into smaller groups or pairs with the researchers or other adults facilitating the work – the space with its multiple rooms also helped. We might understand the space, the adult bodies, the rooms, the doors and myriad other elements all working to enable tensions such as the boy hassle, boy magnetism and toxic masculinity to be addressed safely. This, we maintain, is specific to the compositions of our creative workshops, where the discursive meets the materialities, affectivities and modalities of making. In such compositions, tensions of gendered power can emerge, but they can also be tapped into, escape routes can be crafted, and alternative gendered subjectivities enabled.

The duct-taped X, which remained in place for both days, was not addressed in detail with either group, but its affective pedagogical capacity (Hickey-Moody, Citation2013) appeared to reach the girls, who seemed to acknowledge its significance in maintaining a calm atmosphere for working. Some of the boys, on the other hand, appeared to be perplexed by being barred from going to the rooms reserved for girls. This is perhaps revealing of the ways that the boy hassles that are familiar in schools – and our workshop in this case – are affectively experienced quite differently by those in the boy group. On the second day, some of the girls became more ambivalent in relation to the X; eventually, one of them said, ‘the X can be taken down now’. This reminds us that the conditions of safe and enabling intra-actions will always be situational and subject to the ‘dynamism of forces’ of which they are a part (Barad, Citation2007); they are never achieved once and for all but require an ongoing response.

Working in-tensionally: ethically enabling conditions for addressing gender in young peer cultures

After the workshop days, we convened as a research team to ease out of the intensities of the experience, share things that had stuck with us and plan for the coming days. In this case, it was the ways gender played into the composition of the workshop that we contemplated, acknowledging the complex ways the children were drawn in and caught by normative gendered flows of force. We contemplated how we as researchers and educators responded to those flows of force and the spaces this opened up – or closed – for children’s exploration and expressions on gender.

We cannot know all that fed into the events of the workshop; nor are we capable of ‘getting behind them’. However, the matterings of gender that occurred resonated across a wide range of moments where the affective intensities of gendered peer cultures have come into view and where their affective force has seemed to prevent children from even engaging with the topics. The sedimented ways of how gender mediates in young peer cultures were so firmly present in the children’s lives that, if we had ignored them by dividing the children into mixed groups in the name of diversity, our intentions would have fallen into the unethical trap of gender blindness. Instead of resorting to universal ideals of how gender should (not) matter, these moments require us to stay with the trouble (Haraway, Citation2016) and tensions that occur when our creative practice, the promise of expanding gender and disrupting abuses of power in young peer cultures, and the historically and culturally specific sedimented practices of gender and heteronormativity coalesce. Acknowledging gender as an un-fixed, non-linear and emergent process entangled with normative practices requires us to work committedly, knowing that our efforts and solutions will always be partial and provisional, complicated and incomplete.

We might understand this as working in-tensionally, a neologism that combines tensions and intentionality and reminds us to stay with the trouble and account for the materializing effects of our practices (Barad, Citation2007; Haraway, Citation2016). Working in-tensionally is about engaging tensions with all their messiness and discomforts. It becomes particularly significant if we are to shift from detached, disembodied and adult-led pedagogical practices (e.g. EJ Renold et al., Citation2021) to ones where we find ourselves engrossed and engaged with the quotidian ways that gender matters for children and where our aims go beyond those of merely reciting ideals of gender equality and diversity (e.g. Hall, Citation2020). Working in-tensionally for such praxis is about composing ethically enabling conditions in which gender is not reduced to an either-or or assumed to be without tensions. In our case, it might be argued that naming a space restricted to girls was unjust to those children who did not align with the binary gender structure and that it enforced the very gender norms we particularly aimed to address critically and affirmatively. However, for us the gendering of the group that occurred was not a starting point but part of the co-constitutive relations of creative practice on and with gender. The division materialized and was iteratively reconfigured within this particular entanglement of bodies, amplifiers, duct-taped X, doorframes, rooms, artmaking and abstractions, all of which were combined with our ongoing responsiveness to the emerging gendered flows of force. This responsiveness was built into the very composition of the workshops, with materiality (space, objects, colours) and making (activities with their rhythms and alternating angles) pieced together to generate ‘middles’ from and within which particular capacities could emerge, from and within which more expansive gender expression could be explored (Huuki, Citation2019), and from and within which the persistence of normative gender orders is put to the test. Working in-tensionally to compose ethically enabling conditions for sustainable transformative gestures does not leave heteronormative flows untouched but rather seeks to engage with them in affirmative ways.

Safe and positive peer relations cannot be achieved by merely cultivating skilful diversity discourses that children learn to echo. Instead, it requires working in-tensionally and responding where the gendered histories and inclusive futures meet the messy, contradictory present. Ignoring tensions or glossing them over with ‘good intentions’ risks producing chaotic encounters – as we have seen here – that may make the encounters destructive and could prevent sensitive issues of gender and sexuality to be explored, let alone transformed.

Acknowledgments

This study is part of the Academy of Finland funded research project ‘Mapping, Making & Mattering: Arts and Research-Activism for Addressing Sexual Harassment in Pre-Teen Peer Cultures', 2019–2023 (grant number 322612). We wish to thank the team co-designing and facilitating the workshops and particularly the children participating in them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Suvi Pihkala

Suvi Pihkala works as a postdoctoral researcher in Gender Studies at the University of Oulu, Finland. Her research is inspired by feminist new materialist and posthuman theories and approaches to ethics. In her research, she is interested in exploring response-ability and (micro)politics of change in diverse practices of research. Currently she is exploring these issues in the contexts of creative research-activism on gender and sexual abuses of power in young peer cultures.

Tuija Huuki

Tuija Huuki works as Senior Researcher at the University of Oulu, Finland. Applying insights from feminist new materialist, indigenous and affect theories and co-productive creative and arts-based methods, her research explores how gender and sexual power shapes children’s peer and relationship cultures in settler and Indigenous Sámi contexts, how arts-based methods enable children to safely communicate and address power and other sensitive issues in their lives, and how children’s experiences can be conveyed to wider audiences through research-activism. For details, see www.tuijahuuki.com

Notes

1. For examples of creative interventions, see https://en.fire-collective.com/.

2. Ethics Committee for Human Sciences at the University of Oulu, Finland.

3. Along with Tuija and Suvi, the team included postdoctoral researcher Helena Louhela and doctoral researcher Eveliina Puutio.

References

- Allen, L., & Rasmussen, M. L. (Eds.). (2017). The Palgrave handbook of sexuality education. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-40033-8

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press.

- Bragg, S., Renold, E., Ringrose, J., & Jackson, C. (2018). ‘More than boy, girl, male, female’: Exploring young people’s views on gender diversity within and beyond school contexts. Sex Education, 18(4), 420–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1439373

- Braidotti, R. (2013). The posthuman. Edinburgh University Press.

- Coll, L., O’sullivan, M., & Enright, E. (2018). ‘The trouble with normal’: (Re)imagining sexuality education with young people. Sex Education, 18(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2017.1410699

- Finnish National Board of Education. (2016). New national core curriculum for basic education: Focus on school culture and integrative approach. http://www.oph.fi/download/174369_new_national_core_curriculum_for_basic_education_focus_on_school_culture_and.pdf

- Hall, J. J. (2020). ‘The word gay has been banned but people use it in the boys’ toilets whenever you go in’: Spatialising children’s subjectivities in response to gender and sexualities education in English primary schools. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(2), 162–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1474377

- Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Hickey-Moody, A. (2013). Affect as method: Feelings, aesthetics and affective pedagogy. In R. Coleman & J. Ringrose (Eds.), Deleuze and research methodologies (pp. 79–95). Edinburgh University Press.

- Hickey-Moody, A., Horn, C., Willcox, M., & Florence, E. (2021). Arts-based methods for research with children. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68060-2

- Huuki, T. (2019). Collaging the virtual: Exploring gender materialisations in the artwork of pre-teen children. Childhood, 26(4), 430–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568219862321

- Huuki, T., Kyrölä, K., & Pihkala, S. What else can a crush become: Working with arts-methods to address sexual harassment in pre-teen romantic relationship cultures. (2021). Gender and Education, 34(5), 577–592. . https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2021.1989384

- Huuki, T., Manninen, S., & Sunnari, V. (2010). Humour as a resource and strategy for boys to gain status in the field of informal school. Gender and Education, 22(4), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250903352317

- Juelskjær, M. (2013). Gendered subjectivities of spacetimematter. Gender and Education, 25(6), 754–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2013.831812

- Kearney, S., Gleeson, C., Leung, L., Ollis, D., & Joyce, A. (2016). Respectful relationships educations in schools: The beginnings of change. Final Evaluation Report. Our Watch. Accessed 20.8.2022. https://media-cdn.ourwatch.org.au/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/06/24034138/RREiS_R3_Final_AA.pdf.

- Keller, J., Mendes, K., & Ringrose, J. (2018). Speaking ‘unspeakable things’: Documenting digital feminist responses to rape culture. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1211511

- Manning, E. (2016). The minor gesture. Duke University Press.

- The Act on Equality between Women and Men 609/(1986). Ministry of social affairs and health, finland. https://finlex.fi/en/laki/kaannokset/1986/en19860609_20160915.pdf

- Osgood, J., & Giugni, M. (2015). Putting posthumanist theory to work to reconfigure gender in early childhood: When theory becomes method becomes art. Global Studies of Childhood, 5(3), 346–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043610615597160

- Pihkala, S., & Huuki, T. (2019). How a hashtag matters: Crafting response(-abilities) through research-activism on sexual harassment in pre-teen peer cultures. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 10(2–3), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.3678

- Pihkala, S., & Huuki, T. (2022). Safe and enabling: Composing ethically sustainable crafty-activist research on gender and power in young peer cultures. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1–13. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2022.2026132

- Pihkala, S., Huuki, T., Puutio, E., & Louhela, H. (forthcoming). Friendship Workshops - Feminist arts-based intra-activist methodology with children and young people. In A. Hickey-Moody, G. Coombs, M. Willcox, & S. Pihkala (Eds.), New materialist affirmations. Edinburgh University Press.

- Puutio, E., Huuki, T., Pihkala, S., & Lehmusniemi, A. (2021). Taidelähtöiset menetelmät ja queerit tyttökietoumat alakouluikäisten suhdekulttuureissa [Arts-based methods and girl-queer-entanglements in pre-teen relationship cultures]. Nuorisotutkimus, 38(3), 58–74.

- Renold, E. (2013). Boys and girls speak out: A qualitative study of children’s gender and sexual cultures (ages 10-12). http://www.childcom.org.uk/uploads/publications/411.pdf

- Renold, E. (2018). ‘Feel what I feel’: Making da(r)ta with teen girls for creative activisms on how sexual violence matters. Journal of Gender Studies, 27(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2017.1296352

- Renold, EJ, Ashton, M. R., & Mcgeeney, E. (2021). What if? Becoming response-able with the making and mattering of a new relationships and sexuality education curriculum. Professional Development in Education, 47(2–3), 538–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2021.1891956

- Renold, E., & Ringrose, J. (2019). JARring: Making phEmaterialist research practices matter. MAI: Feminism and Visual Culture. https://maifeminism.com/introducing-phematerialism-feminist-posthuman-and-new-materialist-research-methodologies-in-education/

- Saltmarsh, S., Robinson, K., & Davies, C. (2012). Rethinking school violence. Theory, gender and context. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stewart, K. (2007). Ordinary affects. Duke University Press.

- Strom, K., Ringrose, J., Osgood, J., & Renold, E. (2019). Editorial: PhEmaterialism: Response-able Research & Pedagogy. Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 3(2), 1–39 doi:https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.3649.

- Taylor, C. A. (2013). Objects, bodies and space: Gender and embodied practices of mattering in the classroom. Gender and Education, 25(6), 688–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2013.834864

- Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play. Rutgers University Press.

- Tumanyan, M., & Huuki, T. (2020). Arts in working with youth on sensitive topics: A qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Education Through Art, 16(3), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1386/eta_00040_1