ABSTRACT

This article discusses in/visibility regarding sexual identities, the ‘gay closet’, and ‘coming-out’ within the post-soviet context from a queer feminist perspective. Contemporary western-oriented global queer political culture favours individualized visual representation to fight for social acceptance. In many post-soviet and western contexts, however, LGBTIQ+ visibility is increasingly threatened. Accordingly, many choose strategies to sustain their queer lives beyond visibility and public representation. Queer and feminist theory does not offer adequate concepts to account for these forms of resistance. Building on Édouard Glissant, the decolonial and anti-imperialist philosopher, with his demand for the right to opacity, and off queer theory that reconceptualizes the gay closet, such as that of Anna T. I rethink visual in/visibility and the queer closet as space for relationality and recuperation. While Glissant and T. use the concept of opacity primarily on the level of the verbal, I will re-conceptualize opacity as in/visibility on the level of visual discourses. Engaging with the artistic practice of multimedia artist Ruthie Jenrbekova and filmmaker Masha Godovannaya, both of whom play with the in/visibilisation of queerness as artistic strategies, I show how visual opacity can facilitate coalitions beyond identity politics based on nationality, sexuality and/or gender.

Introduction

Contemporary queer feminist visual discourses and artistic production are dominated by a politics of visibility and representation, especially in the global northwest. Visibility in the form of ‘being out’ is seen as necessary for becoming socially recognized, gaining equality in the form of rights and beyond, and living a free and happy existence. A life of invisibility, in the ‘gay closet’ or the ‘trans closet’, is seen as unfree, dishonest, not livable. These ideas go back to the Gay Liberation Front and similar global northwestern movements (McRuer, Citation2004, p. 528), and are deeply rooted in a neo-liberal individualistic understanding of identity and self-expression. Moreover, the allegedly liberating act of coming out draws on problematic and essentialist notions of identity. It does not conceptually address ‘how lesbian or gay identities are socially constituted, [or] how they are intersected by other arenas of difference, or what sort of collective political action might develop from an assertion of one’s gay or lesbian identity’ (McRuer, Citation2004, p. 529). Yet, coming-out strategies of visibility, for example gay or queer pride marches, continue to be understood as the most important tools for combatting the oppression of non-normative minorities (Magdi & Ah-Ben, Citation2020; Ziyad, Citation2017).Footnote1

Queer theory, starting with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet (1990), has significantly contributed to the persistence of the idea that invisibility and the closet are oppressive modes of existence. Scholars such as the above-quoted Robert McRuer (Citation2004), Johanna Schaffer (Citation2008), Christoph Uehlinger (Citation2013), and, more recently, Koch-Rein et al. (Citation2020), however, have long since highlighted the plethora of problems associated with visibility politics and coming-out. These scholars join the choir of activists (Lang, Citation2020) who criticize visibility as a universal strategy for gaining recognition and equality, by demonstrating the violence against (hyper)visible populations.

Trans*gender, and particularly trans*women of colour, have been at the forefront of this criticism (Chu, Citation2016; Truitt, Citation2014; Ziyad, Citation2017). The hypervisibility of trans* women of colour renders them particularly vulnerable to trans*phobic, racist, sexist and xenophobic violence, and they are subsequently more affected by poverty, homelessness, etc. Trans*activists’ critique of visibility politics is further supported by scholars of colour, such as Black feminist Vanessa Thompson (Citation2021) or the Roma activist, social worker, and political scientist Isidora Randjelovič (Citation2016). Both of them show that Black people and people of colour are racialized and hypervisibilized in white-dominated contexts in the global northwest for the purposes of policing and other mechanisms of control and exclusion, up to and including murder. In addition to ethnic and racialized minorities within northwestern Europe and the USA, residents of Eastern Europe, Eurasia, and the Balkans are particularly critical of visibility policies in the form of coming out and LGBTIQ+ visibility (Horsey, Citation2015; Lang, Citation2020).

In the following text, I delineate why many scholars, artists, and activists from the post-soviet sphere question visibility as a queer political strategy. Moreover, by introducing the work of Kazakh trans* femme intermediaFootnote2 artist of colour Ruthie Jenrbekova, and Russian queer experimental filmmaker Masha Godovannaya, I show how post-soviet artists and activists draw on forms of opacity as an alternative to visibility politics. I chose these two artists’ works, because they both utilize, albeit in very different modes, among other things, the conceptualization of opacity elaborated the Afro-Caribbean poet and scholar Glissant (Citation2010 [1997], adapting it for their respective post-soviet positionalities.

In recent years, queer minorities in both the Russian and the Kazakh socio-cultural spheres have become hypervisibilized, while public coming-outs and other forms of visibility politics have been increasingly and violently sanctioned by state and public actors (Healey, Citation2017; HRW, Citation2014). Although anti-queer visibility politics are deployed to different nationalistic aims in the respective contexts, pro-queer discourse, and especially LGBTIQ+ visibility, in both Russia and Kazakhstan have become increasingly associated with, maligned, and rejected as the result of western influence (Riabov & Riabova, Citation2014; Sleptcov, Citation2017).

At the same time, media, state representatives, and supranational entities in the West have tried to shame Russia, in particular, and to a lesser extent Kazakhstan, into accepting homosexuality and gender diversity, through labelling homo- and transphobia as anti-modern, barbaric and backward (Wiedlack, Citation2017). The latter strategy is not unique to the post-soviet context. Queer studies researchers such as Jasbir Puar (Citation2007), Haritaworn et al. (Citation2014), or Joseph Massad (Citation2009) have provided ample analyses of how global northwestern states, together with supranational institutions, instrumentalize LGBTIQ+ visibility politics to confirm northwestern cultural and political hegemony. Furthermore, they use demands for social acceptance for LGBTIQ+ people in their neocolonialist endeavours in the middle east and the global south. The aforementioned queer theorists, among others, have developed concepts that deconstruct simplistic discourses presenting gay, lesbian, and trans* visibility as a sign of the moral and cultural superiority of the progressive northwest, in contrast to the backwardness, in the form of victims of homo and transphobic violence, of the rest of the world. Others, such as the queer theorists Popa and Sandal (Citation2019), or Pagulich (Citation2020), have developed methodologies that reveal how these global LGBTIQ+ visibility discourses penetrate Eastern European and post-soviet contexts in formal and informal, institutional and extra-institutional, ways, through pedagogical discourses that reinstate (neo)colonial and (neo)imperialist logics of western superiority and progress, aiming at transforming the global East according to a western model, and expanding western influence in an ideological, as well as material, sense. While they offer important critiques, only few scholars have developed alternative concepts of queer visual politics. Artists such as Jenrbekova and Godovannaya, however, have offered methods of creating queer opacity as alternatives to western-centred visibility politics, specifically for the post-soviet context.

In the following, I briefly delineate the cultural context of Russia and Kazakhstan regarding queer visibility and explain why queer visibility politics need to be interrogated in these post-soviet spaces. It builds on the claim that Russian and Kazakh homo- and transphobia are rooted in nationalism, and propelled by anti-western anti-imperialist sentiments. Within these spaces, artists and activists explore different strategies to sustain queer lives.

After my brief contextualization, I will introduce Glissant’s conceptualization of opacity (Glissant, Citation2010 [1997]). An anti-imperialist and decolonial anthropologist, philosopher, and poet, Glissant (1990) articulates a politics of recognition based on transparency, which he views as a colonial form of violence. Building on Glissant’s work, the queer feminist artist and researcher Anna T. deconstructs the assumption that in/visibility and the gay closet are necessarily repressive and unfree. Valuing forms of in/visibility and the gay closet as viable forms of queer existence, T. develops the concept of queer opacity to delineate forms of queer living, queer enjoyment, and relationality falling outside the common forms of visibility. She develops a poetic language to create these possibilities for queer opacity, using gaps and absences, as well as queer slang and polyglotism.

Through a semiotic analysis of the works of Ruthie Jenrbekova and Masha Godovannaya, I will relate T.’s strategies of creating opacity through language to the realm of the visual. While common forms of semiology in the tradition of Cultural Studies scholars such as Mieke Bal and Norman Bryson (1991, p. 174), or the visual sociologist Gillian Rose (Citation2016, p. 107), focus on visible signs, my close analysis of the artworks identifies opacities or in/visibilities, contextualizes them, and finds meanings in them. This process of interpretation or identification of meaning seeks out notions of queerness in the broadest sense, and can, accordingly, be called a queer reading of in/visibility. I will provide evidence that both artists offer forms of in/visibility that can be read queerly, as alternatives to individualized and identity-based forms of representation, such as coming-out. In my examination of Jenrbekova’s recent work, I show how fictional geopolitical mapping, deviation (as opposed to accuracy), and fantasy-gaming can facilitate alternative forms of queer visuality and visibility. Parsing one of Godovannaya’s most recent experimental films, a text floating on a river (Godovannaya, Citation2021), I will show how the shift from queer representation to the queer gaze can become a point of departure for queer solidarity.

My reading of Godovannaya’s film moves from a semiotic reading of signs in cinematic form to a discussion of the cinematic gaze. Looking for the queer gaze, it builds on the long tradition of analysing and theorizing the ‘gaze’ from a feminist perspective, initiated by Mulvey (Citation1975), who defines the gaze as ‘a key element in the construction of modem subjectivity, filtering ways of understanding and ordering the surrounding world’. (Citation2001, 5). A queer gaze, much like the ‘female gaze’ (Jacobsson, Citation1999) or the ‘oppositional gaze’ (Hooks, Citation1992), responds to the dominant ‘male gaze’ (Mulvey, Citation1975, p. 6f.) that objectifies women and non-normative Others. Such a gaze embraces the power that rests in the act of looking. A queer gaze has the potential ‘to deconstruct gender-based power dynamics, changing not only the object but also the intent of the male and female gaze [creating] a world completely free from binary notions of desire and storytelling, [and] space for plural identities and possibilities’ (Moss, Citation2019).

In locating the findings of my semiotic reading, as well as my analysis of the gaze within their socio-political context(s) of production, I explore the extent to which the map/game and film create a kind of closet, and address feminist and queer solidarity. Moreover, in addressing not only the artworks themselves, but their production processes and usages, I wonder if they can initiate what I call, in reference to T., ‘closet bonding’, and solidarity.

Queer visibility, post-soviet states, and western solidarity

Scholarly analyses and human rights advocates have long pointed out that the violence against sexual and gender minorities increased over the course of the last decade in many post-soviet regions, and particularly in Kazakhstan and Russia (Beyer & Finke, Citation2019; HRW, Citation2014, Citation2018; Kudaibergenova, Citation2019; Sheerin, Citation2017). These studies show that in both regions, the increase in physical and psychological violence against gender and sexual minorities went hand in hand with discourses that promote conservative heteronormative patriarchy and reject homosexuality and gender transgression, and that these discourses have become hegemonic national and state discourses. Although the reasons, goals and aims for the increase in homo- and transphobia are to be found within the respective local nationalisms, the discourses, and often also forms of physical and psychological violence, point to many similarities between Russia and Kazakhstan.Footnote3

The number of homo and transphobic discourses multiplied in many post-soviet states during the 2010s, but went largely unnoticed by the international media, until the summer of 2013, when the so-called Russian ‘Anti-Homosexual Propaganda Law’ was introduced. The first iteration of this law prohibited the positive portrayal of homosexuality towards minors, thus basically banning positive queer discourses from the public mainstream. The law targeted LGBTIQ+ visibility, not only in verbal discourses, such as affirmative writing or speech (Sheerin, Citation2017), but also all signs of gay, trans* or queer pride, such as the rainbow flag, and embodied signs of affection between individuals in photographs or other images, and, occasionally, even acts performed in public (life) (HRW, Citation2018). The introduction of the law was accompanied by homophobic public discourses and an increase of physical violence against gays, lesbians and trans* people throughout Russia (HRW, Citation2014). In November 2022 the Russian State Duma passed an even broader law that extended the earlier ban to any public sphere, not just spaces where minors are present (Sauer, Citation2022).

At the time, legal regulations of LGBTIQ+ visibility were proposed in many regions, although most of them were eventually abandoned or never passed. While NGOs and LGBTIQ+ activists had observed these trends with increasing concern prior to 2013, international media attention, as well as an outpouring of solidarity, particularly in western countries, followed only later. Within international debates, LGBTIQ+ visibility became the focus for both homo- and transphobic, as well as pro-queer, stances, and LGBTIQ+ people became a ‘lynchpin for value negotiations’ (Neufeld & Wiedlack, Citation2016) between western and post-soviet states. The preferred means of expressing global northwestern solidarity with queer people in the region, in the media and beyond, was creating visibility for individuals and groups. Northwestern media outlets strategically foregrounded wounded young men as innocent victims to persuade Russia to repeal the law and publicly reject homophobia (Wiedlack, Citation2017). These representations led to the construction of individual martyrs, which more than anything served to confirm western moral superiority. Such pro-western discourses were instrumentalized within Russia as evidence of the West’s hostile attitude towards the nation (Riabov & Riabova, Citation2014). Gays, lesbians, and trans*persons were marked as western agents, as un-Russian, and thus properly made visible, in yet another dimension, as social Others.

In Kazakhstan, ‘a version of this law was deemed unconstitutional in 2015’. (Levitanus, Citation2022, p. 498) Nevertheless, researchers and human rights activists have pointed out that the homophobic political discourse, public awareness, and negative visibility of LGBTIQ+ citizens increased noticeably across the region (Healey, Citation2017). ‘The existing naturalizations of state-ordered gender hegemony juxtapose “traditional” Kazakh identity to queerness, thereby creating a space of belonging (and exclusion) within a new national idea […]’. (Shoshanova, Citation2021, p. 113) Moreover, LGBTIQ+ people face censorship and discrimination, and are routinely denied their right to freedom of expression as Kazakh citizens (Article 19, Citation2015; Kudaibergenova, Citation2019).

Kazakh national discourses, much like their Russian counterparts, continue to signify liberal and pro-queer views as western throughout, and incompatible with the national values. This allows national discourses to reject any pro-LGBTIQ+ politics as western influenced, neocolonial, or neo-imperialist (Beyer & Finke, Citation2019, p. 318; Chebankova, Citation2016; Edenborg, Citation2018; Kudaibergenova, Citation2019; Riabov & Riabova, Citation2014; Stepanova, Citation2015; Wilkinson, Citation2014). As a result, nationalistic anticolonialism manifests frequently in homo- and transphobia. Trans- and homophobia are not single-issue sentiments, but rather part of an assemblage of various conservative, partly right-wing, anti-western ideas, and a ‘framework for making sense of the world [and] a genuine producer of common sense’ (Laruelle, Citation2020, p. 116). Moreover, homo- and transphobia are integrated into a value framework allowing the state to control dissidents and regulate them through laws that are framed as protection. The implementation of these laws (e.g. anti-gay propaganda laws, blasphemy laws, foreign agent laws), in turn, further empowers the existing illiberal sector of civil society (Laruelle, Citation2020, p. 118; Moss, Citation2017, pp. 197–9).

The social context and daily experience of heightened homo- and transphobia in both Kazakhstan and Russia suggest that politics focusing on LGBTIQ+ visibility are at present rather counterproductive, particularly if supported by western allies. This conclusion is supported by sociological research suggesting that queer public visibility is not desired by female-identified and female-passing people in the post-soviet regions (Asylbek, Citation2021; Stella, Citation2012). Yet, solidarity discourses with LGBTIQ+ people in the post-soviet space continue to be dominated by global northwestern visibility politics, though they do not solely originate in the global northwest. Besides playing into discourses that proclaim an incommensurability between so-called eastern and so-called western values, reinforcing both a false sense of western superiority and the anti-western political stance of the East, such visibility politics also privilege white cis-gendered male victims of homophobia. They create the false impression that physical violence committed by vigilante groups or the police is the most common form of violence, thus overlooking the psychological and structural repression of a large spectrum of non-normative people, in particular trans*gender people. Moreover, and importantly, focusing on individuals who are attacked while trying to establish gay and lesbian public visibility, in the form of street protests or Pride events in Russia’s major cities (Stella, Citation2013; Wiedlack, Citation2017) further supports the misconception that LGBTIQ+ communities choose or desire visibility through public coming-out or pride parades as form of self-expression and protest. In the next subchapter, before moving on to my discussions of the two artworks by Jenrbekova and Godovannaya, I will delineate the theoretical concept of queer opacity in regard to the post-soviet space, as an alternative to visibility politics.

Conceptualizing alternative visual politics: queer opacity and in/visibility

In his book Poetics of Relation (2010 [1997]), Glissant criticizes (global northwestern) thought for its demand for ‘transparency’ (2010, p. 190) as the basis for acceptance and societal inclusion. He argues that western politics of acceptance are built on a hierarchy that affirms (north-)western superiority towards the racialized Other. The social demand for transparency is the oppressor’s striving for control, and constitutes an act of violence. Through this process, the hegemon admits the Other into existence, thus creating the Other afresh. ‘Accepting differences does, of course, upset the hierarchy of this scale’ (Glissant, Citation2010 [1997], p. 190). But even if the (north-)western subject does attempt to understand the Other’s difference without creating a hierarchy, it necessarily relates it to the norm that it has previously established or defined. With regard to northwestern visibility politics, it becomes clear how the demand for transparency in form of visibility as the condition for societal acceptance not only victimized many within the post-soviet LGBTIQ+ community, but also defined who could be eligible for solidarity in the first place. In other words, northwestern solidarity discourses create the Other that they wanted to support by propelling societal acceptance. In order to break with the re-creation of this hegemony, Glissant proposes to ‘not merely [agree] to the right to difference but, carrying this further, agree also to the right to opacity’ (Glissant, Citation2010 [1997], p. 190).

At first glance, Glissant seems to position opacity and difference as binary oppositions; but looking deeper, one sees this is not the case. Opacity is constituted by difference from the hegemon, which it rejects by refusing to become transparent and legible to it. Glissant’s demand for the right to opacity is an anti-imperialist, decolonial and anti-racist claim. It is based on the experience that while white hegemonic individuals have the choice to remain invisible or opaque, the racialized oppressed are always forced to reveal themselves for the purpose of knowledge production. Even in the seemingly harmless act of ‘getting to know’ and ‘trying to understand’, hegemonic powers exercise violence against the already marginal populations. Glissant’s usage of opacity is a poetic strategy to resist the violence of Western knowledge production and societal inclusion. At the same time, his poetics actively creates relationality, as it connects speakers of Creole with those who can enjoy non- or partial comprehension.

In Opacity – Minority - Improvisation: An Exploration of the Closet Through Queer Slangs and Postcolonial Theory (Anna, Citation2020), Anna T. examines the gay closet and the refusal to subject oneself to the demand for LGBTIQ+ visibility through the lens of Glissant’s concept of opacity. Her partly autoethnographic analysis concludes that – given new possibilities of digital surveillance, corporate and state control – anonymity and in/visibility are valuable and valued aspects of queer existence. While Glissant finds opacity in the poetic usage of creole languages in the Caribbean, T. refers his concept to queer slang in the context of Greece, and other non-northwestern and non-European contexts. She highlights the potential and function of queer slang to navigate verbally between the hegemonic normative society and its demand for transparency and visibility, and subsequent sanctioning of queer expression or even punishment, and complete invisibility and isolation. T.’s examples of queer slang borrow terms from their respective hegemonic language context and give them slightly or completely different meanings. Additionally, they appropriate words from other languages. Thus, queer slangs are not secret languages, per se. Rather, they are variants of national languages, or polyglotism that sound non-sensical to mainstream society. In her mimicking of queer slangs through the production of poetic texts, T. mixes different queer slangs into English to create opacity. Additionally, she leaves out words through blank spaces. Through queer slang, so T. explains further, LGBTIQ±identified and other non-normatively living and loving people navigate their in/visibility within societies. They allow them to connect with queer individuals and community, while partly maintaining the safe space of the gay or queer closet. For T., the closet is not exclusively or primarily a violent space, but a home, a retreat, a space for recuperation, and self-care (Anna, Citation2020, p. 149). T.’s elaborations on queer opacity through language and the queer closet allow for a thinking of queer opacity through visual means. To mark the fluidity of queer opacity I will also refer to it as ‘in/visibility’.

Queer opacity and magic resistance in Ruthie Jenrbekova’s art

An example of the production of queer opacity through visual means is Ruthie Jenrbekova’s Geopolitical Queer Map of Eurasia (2021). A Kazakh trans* femme intermedia artist, Jenrbekova is part of the artist group Krёlex zentre,Footnote4 and collaborates frequently with activist and artist groups transnationally. The name ‘Krёlex zentre’ is a reference to Glissant: Glissant wrote from the position of a Creole person, a position that the Krёlex zentre mimics, by using the Kazakh/Russian word for Creole and relating the ethnic and cultural mix between Kazakh and Russian culture, language, and ethnicity to Glissant’s anti-imperialist context of the Caribbean. By aligning themselves with Afro-Caribbean decolonization projects rather than with LGBTIQ+ efforts aimed at reaching the western status quo, they position themselves within a decolonial post-soviet framework. Additionally, this implies a stance towards the history of soviet modernization and its perpetuation of Russian influence, viewing both as forms of imperialism and (neo)colonialism. Rather than simply transferring Afro-Caribbean knowledge and concepts to the post-soviet realm, such an alignment positions the artist and her ‘zentre’ within the tradition of decolonial internationalism. While theirs is a decolonial stance that is critical of western politics, by refusing an ethnic national identity and instead appropriating the concept of Creole/Krёl, Jenrbekova and the Krёlex zentre reject Kazakh nationalist, as well as Russian imperialist, anti-western sentiments.

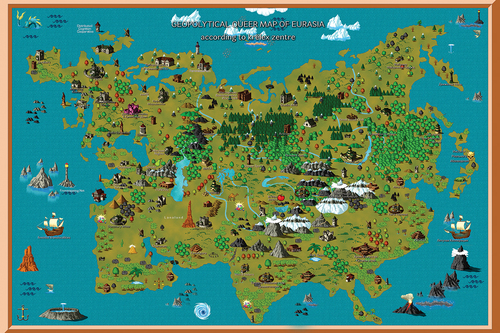

The Geopolitical Queer Map of Eurasia is a prime example of Jenrbekova’s internationalism, which is critical towards nationalisms and imperialisms of any kind, whether Russian or Western. It is a large-scale print and game board, last displayed in the Moscow Museum of Modern Art in summer 2021.

shows a fictionalized version of Eurasia, framed by the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean on the left, the Indian Ocean at the bottom, the Pacific Ocean to the right, and Arctic Ocean at the top. Besides deviating from the geographical coordinates, the map does not comply with common depictions of Eurasia, since it decentres Europe, and relegates it geographically to the the periphery. Jenrbekova transfers T.’s strategy of using a common language and signifying it with new meanings into the realm of the visual. She uses the traditional form of geopolitical mapping, but invests the common signs within such depictions with new meanings through rotating the direction of the map, and exchanging signs, like capital cities and border markings, etc., with self-organized, and mostly underground, collectives, and some NGOs, operating in the respective regions. Only a few of these communities or institutions include their locations in their names, like the Бишкек феминисттик демилгелери (Bishkek Feminist Initiatives) at the map’s bottom centre, or the Omsk Social Club in its upper-right corner. Most names, however, reveal neither location nor purpose, nor do they address viewers/readers who do not know about these organizations already. While the visual is readable as a geopolitical map, its signs are hardly identifiable by people who do not know at least one or several of the indicated NGOs or communities. However, those who do know one or several of them will understand that it displays a significant network of queer, trans*, feminist, anarchist, socialist, communist and anti-racist initiatives all over Europe and Eurasia. Although some of the initiative names are revealed through the map, Jenrbekova, very much like T., uses polyglotism to signal simultaneously queer presence and offer queerness up for relationality, and at the same time encrypt it through the introduction of a foreign language or even foreign alphabet. In the case of the Бишкек феминисттик демилгелери (Bishkek Feminist Initiatives), for example, the feminist politics are made opaque through the Kyrgyz language that is introduced into a Russian-speaking context. Another example is the English word ‘queer’, written in Arabic letters in the title of the work, which does not mean anything within Kazakh, Russian, or any other post-soviet languages, and has not yet reached the mainstream as an English loanword.

Figure 1. Geopolitical Queer Map of Eurasia. Printed with the kind permission of copyright owners Ruthie Jenrbekova and the Krёlex zentre.

Jenrbekova’s map, however, not only locates initiatives, thereby introducing those who recognize one or several of them to an entire network, while hiding them in plain sight from mainstream society; it also establishes itself as active networking practice. Jenrbekova, together with other members of the imaginary Krёlex zentre, first contacted their colleagues from other regions and initiatives with whom they already had a relationship, and asked for their permission to visualize their connection through putting their names on the map. These contacts introduced them to others that they had not been aware of before. Additionally, the Krёlex zentre put the word out on Facebook. They accepted all responses, and eventually the list of initiatives included between 65 and 70 names. They did not verify whether the initiatives were real or imaginary, and no other selection criteria were involved.

According to members of the Krёlex zentre, people who saw the map at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art exhibition and recognized some of the initiatives felt a sense of connection and empowerment from the large number of groups (personal communication 5 February 2022). People who did not recognize any of the groups were rather irritated by the project, since it does not reveal much of its purpose or significance to people who are not already predisposed to connect to some of the queer feminist names. Thus, it is an intervention into the museum space, as well as an irritation to common expectations of geopolitical knowledge.

The map’s role of opaque or in/visible representation is significant in the context of oppositional queer and feminist politics in the post-soviet region, since it allows communities and individuals to feel connected, and to expand their knowledge about queer solidarity networks. Yet, as a museum installation, the map is not only a visual representation, but also a role-play table game, with glass beads and a wooden mailbox. Visitors were invited to move the beads across the map and send notes to the Krёlex zenter. Instructions stated that although they themselves did not know how to play the game, members of the Krёlex zenter were open to suggestions by the audience. Moreover, they asked visitors to move the glass beads to a location they found appealing, to write the name of the initiative on a piece of paper, and explain why they chose it. They were additionally asked to write a fictional name, their real email address, and their game level on the same paper, and drop it into the wooden ‘magic’ mailbox. Instructions closed with the prospect: ‘[P]erhaps you will receive an answer from Krёlex zenter – even though this organization does not exist. The consequences of such direct contact with the non-existent are usually unpredictable’ (personal communication 2 February 2022). During the exhibition in the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, the Krёlex zentre received 173 letters.Footnote5

Jenrbekova’s Geopolitical Queer Map of Eurasia navigates in the same sphere of opacity as T.’s queer slang. However, it does not revert to the existing queer slang or ‘tema’ (Clech, Citation2018, p. 12) shared within Russian-speaking post-soviet regions, but instead uses fictional mapping and magical realismFootnote6 as a means of creating visibility of the initiatives for those in the know, and rendering them incomprehensible for those who are not familiar with queer existence in post-soviet regions. This in/visibility is enhanced even further by references to non-existence (the Krёlex zentre does not exist) and uncertainty (the lack of knowledge of how the game is played). Finally, the game makes a clever reference to the queer, trans* or gay closet, through the wooden box: rather than inviting people to declare their queerness and queer solidarity, the Krёlex zentre invites them to submit (themselves) to the sphere of in/visibility. It invites a process of stepping in, rather than coming out. When submitting to this closet, a relation in the form of a letter correspondence might occur. Within the space of the museum, the entire map/game can be seen, with T., as a kind of queer closet. It functions as a space of retreat for queer individuals to connect with each other, while it is relatively impenetrable to the interrogating gaze of homo- and transphobic onlookers. As an official museum exhibit, hence, as legitimate art, it demands, with Glissant, the right to opacity or in/visibility, respect, and acknowledgement, refusing transparency.

“Floating” significations and queer desires

My second of queer politics of in/visibility is Masha Godovannaya’s recent experimental film a text floating on a river (2021). The film was created in collaboration with the post-soviet trans* poet, artist, and art historian Koivo, and emerged explicitly out of the art and research project ‘The Magic Closet and The Dream Machine: Post-soviet Queerness, Archiving, and the Art of Resistance’ (2020–2024). The latter project included workshops, where people from and in the post-soviet context who identify themselves as queer, kvir,Footnote7 or can relate to queer/kvir ways of existence, come together and collectively create knowledge about their lives, identities and resistance against homo-, trans- and queerphobia, misogyny, ableism and racism. Koivo attended one of these workshops in summer 2020 and created several poems within its framework, among them a text floating on a river (2021).Footnote8 Godovannaya teamed up with Koivo to transform his writing, collaboratively, into an experimental film.

A text floating on a river (2021) is a montage of images collected on a short trip along the Danube River on public transport in April 2021. It is 8 minutes 50 seconds long, and filmed in black and white, with an old Soviet 16 mm camera. To understand how it comments on queer in/visibility and representations of post-soviet queer life, it is important to consider the context in which the film emerged. At first glance, the film represents absences and can be understood as a transferral of T.’s queer strategy of creating opacity through the absence of words within her writing to the realm of the cinematic. The first of these cinematic absences is the lack of a protagonist of the film’s narrative, or a whole actor, for that matter. In the beginning, the viewer only sees parts of a moving body.

As exemplified in the film still in , the body’s gender and sex are opaque. A person is sitting partly in front, partly beneath the camera, looking through a book of antique Greek architecture. We cannot identify who this person is, because his/her face is outside the frame and there is nothing that indicates anything concrete about his/her identity. Hands are flipping pages. The meaning of Greek Architecture remains opaque throughout the film, as well. Koivo reports that he found the book – Peter Green’s Parthenon (1973) – on a street in Vienna; or rather, that the book found him: an art historian interested in historic architecture (private communication, 28 February 2022). As an objet trouvé, disregarded by another resident of Vienna, the book speaks to Koivo’s status and experience as a member of the queer Russian- speaking diaspora, whose experience of the city diverges significantly from the average, heteronormative, privileged Viennese experience. What, for another person, might be a no-longer-relevant piece of bourgeois education, or a memory of long-forgotten summer vacations, becomes the basis for Koivo’s ‘inquiry about how the architectural elements of the past manifest themselves in the everyday – in those mundane structures that support our daily lives and moves: bridges, elevated highways, and underpasses’ (Godovannaya, Citation2021). The adaptation and resignification with new, personal, and queer meanings of a commonly known object transfers the strategy of queer slang and the allocation of new meanings to a commonly used word into the cinematic realm. As such, it is the first indication that the film is a kind of queer language, a visual language of in/visibility.

Figure 2. A text floating on a river film still 1. Printed with the kind permission of copyright owner Masha Godovannaya.

Additionally, the comparison between the Greek Parthenon in the book, and its architectonic transformation into the mundane, yet democratic structures of ‘the infrastructure’, might be also read as a comment on the history of European civilization and democracy, the pride and promise of western Europe that daily fails, not only migrants from the post-soviet space, but more broadly.

The concrete columns, over- and underpasses, and balustrades appear monumental in Godovannaya’s film, almost awe-inspiring. The film imparts an atmosphere of excitement and doom. The film still in exemplifies this mood.

Figure 3. A text floating on a river film still 2. Printed with the kind permission of copyright owner Masha Godovannaya.

While it seems to signal something pending, it also evokes images of the past. It shows Vienna – a Vienna that many members of the queer diasporic precariat frequent – and simultaneously brings up notions of soviet/socialist architecture, aesthetics, and pathos. Knowing that the artists are from Russia, one cannot not see ‘a text floating in a river’ as a cinematographic comment on the influence of Sergei Eisenstein’s aesthetic. Vienna’s architecture, as exemplified in , which shows an area close to the Danube, looks more like soviet brutalism and its promises of a brighter, better future for the masses, than Viennese rococo or neo-classicism, so closely connected to elitism and inequality. The strategy of allocating new and different meanings to commonly known objects can be identified here again; at the same time, it is not only meaning that is blurred or opaque, but vision itself. The film makes use of cinematic montage to disrupt any certain identification of time and space. Visual clarity and representation are further interrupted through the chemical processes involved in the film’s recording, developing, and editing. Godovannaya shot the sequences ‘on an expired colour film stock that was later self-developed and montaged with b/w parts’ (personal communication, 28 February 2022). Through the DIY photochemical processes, the filmed elements, human body parts, the book, architecture, trees, and the river are shown in unusual colours, unnatural contrasts and scratches, dust, chemical residues disrupt their forms and clarity and become the real actors in the film.

The film’s second absence is the text that the title promises. There is no text at all, in the narrow sense of the word – neither in floating written form, nor as a voice-over or in subtitles. Yet, a text floating on a river is based on Koivo’s poem that transports a sense of confusion of being caught in-between his new place of residency in Vienna and Russia – an in-between times, spaces, and localities (Koivo, “текст плывущий по реке”, Citation2021, n.p.). It is important to understand that the film, although shot by Godovannaya, tries to imitate Koivo’s gaze on the elements of the city, the structures that support its railway lines, street overpasses and bridges, as well as the Danube River that flows steadily between the two parts of Vienna. Koivo’s poem thus ‘directs’ Godovannaya’s camera, and the film is the result of their intimate engagement with each other, their emphatic efforts to understand and to support each other, and to realize each other’s vision.

As a film, a text floating on a river does not verbalize queer desire or relations. Yet, its existence and aesthetic form speak volumes to queer relations, queer friendship and the acknowledgement of queer desires. The Vimeo film description states that ‘the film [is] a space where we are fulfilling each other’s desires and trusting one another in our aspirations and interests. Together, we will depart for a cinematic errantry to practice mutuality of diverse materialities, histories, and realities, taking comfort and appreciation of our queer structure of feelings, human and more-than-human’ (Godovannaya, Citation2021, n.p.). Koivo, Godovannaya and the city landscape engage with each other, create, and answer each other’s desires through their process of filming. Thus, the film offers, with Anna T., a kind of queer closet, a space where queerly identified people can enjoy themselves without becoming fully transparent, hence vulnerable, to the outside.

Together, Godovannaya and Koivo collaboratively develop a visual language and aesthetic that speaks to and of their queer desires, relations, ways of living. This visual language is, however, opaque, resembling, in a sense, the queer slang of Anna T. It is a queer visual slang, utilizing landscapes that have specific meanings for queer migrants from the post-soviet context more broadly, and queer Russian migrants more specifically, yet mean something entirely different, or nothing at all, to the Viennese mainstream population. Importantly, the film does not aim at representing queer identities or bodies, but negotiates cinematographic forms to visualize what David L. Eng calls ‘the feelings of kinship’ – ‘the collective, communal, and consensual affiliations as well as the psychic, affective, and visceral bonds’ (Citation2010, p. 2). Such a visual artistic practice is not meant to represent identities or communities, or queer desires. Rather, it is supposed to ‘sustain [diasporic] queer living, loving, dreaming’ (Godovannaya, Citationforthcoming) and world-making. For anyone who does not know about the queer post-soviet migrant context of both artists, Godovannaya and Koivo, the films will not necessarily evoke any references to queerness at all, and it is meant to be like this. A text floating on a river does not represent queer embodiment, queer sexual interactions, queer bonding or verbalize any of those. Yet, it offers a queer gaze which brings to the fore sentiments that speak to queer diasporic existence, and queer feelings: queer anxieties, but also queer relationality, queer collaboration, and queer friendship.

Moreover, this seemingly striking absence of text – written or spoken language – draws attention to the film as text. The title’s text floating on the river is the film itself. It is not a sign of speechlessness in the context of queer life and queer migration. Instead, the visual language and the film’s soundscape are the text that emerges through queer bonding, and queer feelings. The film leaves a trace of queer existence in Vienna. ‘With [their] collective gesture of text-writing, image-making, and sound-recording, [Godovannaya and Koivo] establish a dialog with this landscape and translate it to [a] common language capturing and rendering it through [their] oppositional gazes’ (personal communication 28 February 2022). This trace too, however, is opaque or in/visible. Like Glissant’s poetic and T.’s slangs, Godovannaya’s and Koivo’s cinematographic language speaks in several tongues. Its queerness is not understandable to every viewer. But this does not mean that it does not speak to viewers. In its refusal to become transparent, a text floating on a river (2021) demands the right to opacity.

Conclusion

Queer visual politics that want to account for the vulnerability and precarity of hypervisible minorities and form meaningful queer-feminist solidarities need to develop new visual practices. The works of trans* femme intermedia artist Ruthie Jenrbekova and the queer experimental filmmaker Masha Godovannaya offer alternative forms of queer presence that floats between invisibility and visibility. Their art strays, in different ways, from individualized and identity-based coming outs, yet both Jenrbekova and Godovannaya redefine queer visual politics. Through their very different aesthetics and artistic forms, they both find ways to visibilize queer relationality. What is queer in their art, and how they speak to the queer post-soviet existence, is only evident through the contextualization of their works. Neither is it the kind of piece that willingly makes itself transparent to the western gaze or to that of the heteronormative post-soviet hegemon. On the contrary, the two artists I have discussed use in/visibility as an aesthetic to build and strengthen connections to vulnerable populations without exposing them. Thus, their art is an invitation to people who identify with or as queer/kvir into a magic closet, as an opaque space of collaboration and solidarity.

Jenrbekova’s Geopolitical Queer Map of Eurasia plays with the deviation (in opposition to accuracy) of place/location and the form of fantasy-gaming, creating alternative forms of queer visuality and visibility in the process. Following Glissant and T., Jenrbekova’s work refuses to make any identity transparent, attempting to resist the violence of western knowledge production or any other oppressive form of standardization, classification and hierarchization. The map transfers T.’s queer poetics of opacity into the realm of the visual, using loan words from English, introducing foreign names and writing systems into the Russian-speaking context. Moreover, through fictional mapping, Jenrbekova creates visibility for post-soviet queer and feminist NGOs and communities, and enables forms of queer relationality. However, through visual techniques such as abstraction, and the distortion of geographic spheres through rotating the map in an unfamiliar direction, moving mountains and rivers, and refusing to identify capital cities or borders, the queer institutions and groups are only visible for those who already know one or many of them. For those who are not familiar with, ignorant of, or hostile to queer existence in post-soviet regions, the map renders queerness, queer politics and relationality largely incomprehensible, which ensures that the map cannot be weaponised against queer communities, organisations or individuals.

Godovannaya’s experimental film, a text floating on a river (2021) shares the feature of creating uncertainty of identity, place, and time by Jenrbekova, yet activates it through very different aesthetic forms. Godovannaya and Koivo use unusual frames and perspectives that refer to different times and places, montage, and experimental chemical processes to create opacity concerning the locations they filmed. Their film represents, with Anna T., a kind of queer closet that offers space to rejoice and bond, while refusing to be made transparent. Queerness may, within this context, refer to identifications – but not exclusively. Rather, it is a way of relating to one other, hearing and caring for one other. As cinematic artwork, the film moves away from representation almost altogether, offering instead a queer gaze as a point of departure for queer solidarity. It echoes Glissant’s clamour for the right to opacity, refusing to be fully understood, yet demanding acknowledgement and solidarity.

Acknowledgments

The ideas and concepts of this article were developed within the framework of the project “The Magic Closet and the Dream Machine: post-soviet Queerness, Archiving, and the Art of Resistance” (AR 567), funded by the Austrian Science Fund (2020-2024).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katharina Wiedlack

Katharina Wiedlack is Assistant Professor for Anglophone Cultural Studies at the University of Vienna. Her research interests are queer and feminist theory, popular culture, post-socialist, decolonial, disability studies and transnational American studies. She has published on queer-feminist counter cultures, media discourses as well as on feminist and queer activism in the context of the USA and Russia among other things. Her current arts-based research project “The Magic Closet and the Dream Machine” (AR 567, 2020-2024) investigates issues around post-soviet Queerness, Archiving, and the Art of Resistance. It is conducted by Katharina Wiedlack, in collaboration with Masha Godovannaya, Ruthia Jenrbekova and Iain Zabolotny, and funded by the Austrian Science Fund.

Notes

1. This sentiment was recently showcased in the context of the World Economic Forum by Simon Freakley’s article ‘How do we solve LGBTQ discrimination? One word: visibility’. (https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/lgbtq-discrimination-one-word-visibility/, 18 January 2019).

2. The term ‘intermedia’ was coined by the artist group Fluxus in the mid-1960s, to describe various inter-disciplinary art activities that occurred between genres, including painting, poetry, filmmaking, theatrical performances and drawing.

3. While it is outside of the scope of this article, I want to emphasize that the violence against gender and sexual minorities in Kazakhstan and Russia must not be seen as isolated phenomena. In both contexts, but particularly in Russia, these forms of violence are deeply embedded in anti-democratic nation building processes that aim at national consolidation through conservatism and militarization. Although the homo- and transphobic violence does not exclusively or even primarily emerge from agents of the state, they are supported by national discourses and the general increasing suppression of oppositional movements and discourses by the state since the mass-uprising in form of street protests against the Putin regime in 2011.

4. The name is an assemblage of mostly Latin letters, the Cyrillic ё (io) and Russian and English language transcriptions of the word Creole (English) and Kreol (Russian) with a gender-neutral ending x.

5. As of today, there is no information available how many letters they answered.

6. I use the term magic realism in reference to the international literary fiction and art movement that emerged in many places simultaneously in the first half of the twentieth century and lives forth in the writing of Haruki Murakami, Shivaram Karanth, Devanur Mahadeva or Olga Tokarczuk etc. and the art of Wangechi Mutu and many others. Magic realism gives a generally realistic image of the world while also adding elements of magical, blurring the distinction between reality and fantasy. Despite including magic elements, it is not pure fantasy because of its usage of a substantial amount of realistic detail. Moreover, the employment of magical elements in magic realism is made to comment on reality, rather than creating an alternative reality.

Additionally, the usage of magic realism to describe Jenrbekova’s work seems justified, since her work oscillates between the application of western academic theory and jargon and the introduction of phantastic elements, from ghostly to magic matters.

7. The word ‘квір’ (‘kvir’) was introduced by both LGBT NGOs and grassroots activists in Ukraine around 2008. Within anarchist activists discourses in Kyiv the term was used to address intersecting forms of oppressions. Today, the word is used within both academic and activist discourses (Wiedlack et al., Citation2022, pp. 12–13). ‘Deprived of the connotations and meanings which this term has in Anglophone communities, who all recognize its origins as a homophobic term reclaimed by LGBTQ people, in Russia, the term kvir has so far been discursively linked with the neoliberal commodification of mediatized and mediated cultural prosumers’. (Andreevskikh, Citation2021, n.p.) The exception to this rule are some activists in metropolitan areas, who use it as political term. ‘Russian LGBT activists report that the term “queer” was introduced as an apolitical and elitist concept, undermining not only LGBT identities, but LGBT activism as such. Thus, “queer” as a concept is very ambiguous in the Russian-speaking context and “queer” as a term often remains a foreign word, not filled with any meaning and emotion, unlike in the English-speaking context’ (Neufeld & Wiedlack, Citation2016, p. 189).

8. The Russian version ‘текст плывущий по реке’ can be found on https://polutona.ru/?show=1125231704 (last accessed 22 March 2022).

References

- Andreevskikh, O. (2021): ‘Russian queer (counter-)revolution? The appropriation of western queer discourses by Russian LGBT communities: A media case study.’ Queer Asia. https://queerasia.com/2021-blog-russian-queer-revolution/

- Anna, T. (2020): Opacity - minority - improvisation: An exploration of the closet through queer slangs and postcolonial theory. Transcript.

- Article 19. (2015). “Don’t Provoke, Don’t Challenge” the censorship and self-censorship of the LGBT community in Kazakhstan. Report. https://www.article19.org/data/files/KZ_LGBT.pdf

- Asylbek, B. (7 June. 2021). Нетерпимость и агрессия к ЛГБТ+. В чем причины гомофобии в Казахстане? Radio Azattyq. https://rus.azattyq.org/a/kazakhstan-homophobia-causes-of-aggression/31292952.html

- Beyer, J., & Finke, P. (2019). Practices of traditionalization in Central Asia. Central Asian Survey, 38(3), 310–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2019.1636766

- Chebankova, E. (2016). Contemporary Russian Conservatism. Post-Soviet Affairs, 32(1), 28–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/1060586X.2015.1019242

- Chu, A. (30 March. 2016). The dark side of ‚visibility’: How we slept on trans people becoming the new scapegoats of the right. Salon. https://www.salon.com/2016/03/30/the_dark_side_of_visibility_how_we_slept_on_trans_people_becoming_the_new_scapegoats_of_the_right/20.Juni2021

- Clech, A. (2018). Between the labor camp and the clinic: Tema or the shared forms of late soviet homosexual subjectivities. Slavic Review, 77(1), 6–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/slr.2018.8

- Edenborg, E. (2018). Homophobia as geopolitics: ’Traditional Values’ and the negotiation of Russia’s place in the world. In J. Mulholland, E. Sanders-McDonagh, & N. Montagna (Eds.), Gendering nationalism: Intersections of nation, gender and sexuality (pp. 67–87). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eng, D. (2010). The feeling of kinship: Queer liberalism and the racialization of intimacy. Duke University Press.

- Glissant, É. (2010 [1997]). Poetics of relation. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

- Godovannaya, M. (2021). A text floating on a river. [Film]. https://vimeo.com/612393693

- Godovannaya, M. (forthcoming). Queer Partisaning: Scraps, Touches, and Traces of Cinematic Errantry [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Institute of Art Theory and Cultural Studies, Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.

- Haritaworn, J., Kuntsman, A., & Posocco, S. (2014). Queer necropolitics. Routledge.

- Healey, D. (2017). Russian homophobia from Stalin to Sochi. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.

- Hooks, B. (1992). Black Looks: Race and representation. South End Press.

- Horsey, J. (18 October. 2015). With visibility comes a cost: To be gay in the Bal-kans. In: Adaptation. https://globalist.yale.edu/in-the-magazine/features/with-visibility-comes-a-cost-to-be-gay-in-the-balkans/

- HRW. (2014). License to harm. violence and harassment against LGBT people and activists in Russia. Human Rights Watch https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/russia1214_ForUpload.pdf

- HRW (12 December. 2018). No support: Russia’s “Gay Propaganda” law imperils LGBT youth. Human Rights Watch https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/12/12/no-support/russias-gay-propaganda-law-imperils-lgbt-youth

- Jacobsson, E.M. A Female Gaze?. (1999). https://cid.nada.kth.se/pdf/cid_51.pdf

- Koch-Rein, A., Haschemi Yekani, E., & Verlinden, J. (2020). Representing trans: Visibility and its discontents. European Journal of English Studies, 24(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2020.1730040

- Koivo. (2021) “текст плывущий по реке.” Author’s personal webpage. https://polutona.ru/?show=1125231704

- Kudaibergenova, D. T. (2019). The body global and the body traditional: A digital ethnography of Instagram and nationalism in Kazakhstan and Russia. Central Asian Survey, 38(3), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2019.1650718

- Lang, N. (9 October. 2020). How do you celebrate coming out day when you can’t be out?Them. https://www.them.us/story/coming-out-day-2020-fawzia-mirza-interview

- Laruelle, M. (2020). Making Sense of Russia's Illiberalism. Journal of Democracy, 31(3), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2020.0049

- Levitanus, M. (2022). Agency and resistance amongst Queer people in Kazakhstan. Central Asian Survey, 41(3), 498–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2021.2008874

- Magdi, T., & Ah-Ben, L. (2020). Pride during a pandemic: Why visibility and connection still matter. CNN. June, 25. https://edition.cnn.com/2020/06/24/world/pride-pandemic-visibility-connecting-lgbtq-community-spc/index.html

- Massad, J. (19 Dezember. 2009). The West and the orientalism of sexuality. Reset-Doc web magazine https://www.resetdoc.org/story/the-west-and-the-orientalism-of-sexuality/

- McRuer, R. (2004). Boys‘own stories and new spellings of my name: Coming out and other myths of Queer positionality. In D. Carlin/J. DiGrazia (Eds.), Queer Cultures (pp. 526–560). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Moss, K. (2017). Russia as the saviour of European civilization: gender and the geopolitics of traditional values. In R. Kuhar & D. Paternotte (Eds.), Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe: Mobilizing against Equality (pp. 195–214). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Moss, M. (April 3, 2019). ‘Thoughts on a Queer Gaze.’ 3:am Magazine. https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/thoughts-on-a-queer-gaze/

- Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual pleasure and narrative cinema. Screen, 16(3), 6–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/16.3.6

- Mulvey, L. (2001). Unmasking the Gaze: Some thoughts on new feminist film theory and history. Lectora, 7, 5–14.

- Neufeld, M., & Wiedlack, K. (2016). Lynchpin for value negotiation: Lesbians, Gays and Transgender between Russia and ‚the West. In B. Scherer (Ed.), Queering paradigms VI (pp. 173–194). Peter Lang.

- Pagulich, L. (2020). New lovers … ? As patriots and citizens: Thinking beyond homonationalism and promises of freedom (the Ukrainian case). In K. Wiedlak/S. Shoshanova/M. Godovannaya (Eds.), Queer-feminist solidarity and the East/West divide (pp. 125–152). Peter Lang.

- Popa, B./Sandal, H. (2019). Decolonial Queer Politics and LGBTI + Activism in Romania and Turkey. Oxford Research Encyclopedia, Politics, (June), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.1282

- Puar, J. (2007). Terrorist assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Randjelovič, I. (2016). „Auf vielen Hochzeiten spielen“: Strategien und Orte widerständiger Geschichte(n) und Gegenwart(en) in Roma Communities (Nghi Ha, Kien/Lauré Al-Samarai, Nicola/Mysorekar, Sheila, Eds.). re/visionen. Unrast.

- Riabov, O., & Riabova, T. (2014). The decline of Gayropa? Eurozine https://www.eurozine.com/the-decline-of-gayropa/

- Rose, G. (2016). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. SAGE.

- Sauer, P. (24 November. 2022). Russia passes law banning ‘LGBT propaganda’ among adults. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/24/russia-passes-law-banning-lgbt-propaganda-adults

- Schaffer, J. (2008). Ambivalenzen Der Sichtbarkeit: Über Die Visuellen Strukturen Der Anerkennung. Transcript. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Sheerin, C. (2 March. 2017). The human impact of Russia’s ‘gay propaganda’ law Russia. INFEX. https://ifex.org/the-human-impact-of-russias-gay-propaganda-law/

- Shoshanova, S. (2021). Queer identity in the contemporary art of Kazakhstan. Central Asian Survey, 40(1), 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2021.1882388

- Sleptcov, N. (2017). Political homophobia as a state strategy in Russia. Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective, 12(1), 140–161.

- Stella, F. (2012). The politics of in/visibility: Carving out queer space in Ul’yanovsk. Europe-Asia Studies, 64(10), 1822–1846. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2012.676236

- Stella, F. (2013). Queer space, pride, and shame in Moscow. Slavic Review, 72(3), 458–480. https://doi.org/10.5612/slavicreview.72.3.0458

- Stepanova, E. (2015). ‘The spiritual and moral foundation of civilization in every nation for thousands of years’: The traditional values discourse in Russia. Politics, Religion & Ideology, 16(2–3), 119–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/21567689.2015.1068167

- Thompson, V. E. (2021). Beyond policing, for a politics of breathing Duff, Koshka. In Abolishing the police (pp. 179–192). London: Dog Section Press.

- Truitt, J. (21 June. 2014): Against Visibility. Feministing. http://feministing.com/2014/07/21/against-visibility/

- Uehlinger, C. (2013). Coming-out – zum Verhältnis von Sichtbarmachung und Anerkennung im Kontext religiöser Repräsentationspraktiken und Blickregimes. In D. Lüddeckens, C. Uehlinger, & R. Walthert Die Sichtbarkeit religiöser Identität. Repräsentation – Differenz – Kon-flikt (pp. 139–162). Pano Verlag.

- Wiedlack, K. (2017). Gays vs. Russia: Media representations, vulnerable bodies and the construction of a (post)modern West. European Journal of English Studies, 21(3), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825577.2017.1369271

- Wiedlack, K., Dmytryk, D., & Syaivo. (2022). Introduction. Fucking solidarity: Queering concepts on/from a post-soviet perspective. Feminist Critique, 5, 10–26. https://doi.org/10.52323/567892

- Wilkinson, C. (2014). Putting ‘traditional values’ into practice: The rise and contestation of anti-homopropaganda laws in Russia. Journal of Human Rights, 13(3), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754835.2014.919218

- Ziyad, H. (June 29, 2017): ‘For black queers, invisibility is often the best liberation strategy.” Slate. https://slate.com/human-interest/2017/06/is-lgbtq-visibility-politics-inherently-anti-black.html