ABSTRACT

Emerging research points to the increasingly expansive ontologies of gender that young people engage with in contemporary society. This paper examines the representations of gender that emerged in one urban site: a science gallery exhibition in London that sought to de-centre fixed binary gender categories – a site where gender is explicitly being ‘redone’ (West & Zimmerman, Citation2009). Drawing on research work on curation (Acord, 2010) we examine data (drawings and text) produced by 516 young people who attended the exhibition, exploring the ways gender is narrativised and re-curated within the physical and discursive space(s) of the gallery. Our findings show the ways that gender was felt and represented in these recurations, as fixed and unfixed, and productive and unproductive. The participants reassembled the ideas of gender presented within the gallery through representations imbued with affect. This included representations that conflated sex and gender and privileged bio-essentialist narratives, as well as representations that drew on binary models and logics. These re-curations, we argue, point to the ways that young people are making sense of gender (im)possibilities. We argue that these narratives highlight the ways young people are grappling with discourses of gender as they transition into adulthood in contemporary society.

Introduction

A key aspect of transitions into adulthood and identity making for young people concerns gender. That is, how existing, persistent, and emergent ontologies and structures of gender are (re)produced as young people enter into adulthood. Risman’s (Citation2018) recent work exploring young people’s experiences of gender points to the varied everyday practices and strategies young people are engaged in that maintain, disrupt, change and/or rebel against the gender structure. Other recent work (Cover, Citation2018) has pointed to the proliferation of emergent labels that are used to make sense of and identify with gender. Indeed some young people are re-working language to suit individual experiences that are not confined to singular pre-existing categories (Robards et al., Citation2018; Russell et al., Citation2009). This includes new(er) labels, such as ‘non-binary’, ‘gender queer’ and ‘genderfluid’. Emergence of new media platforms, including Tumblr, Instagram and YouTube have offered new spaces for exploring and making sense of gender (Hanckel et al., Citation2019; Vivienne et al., Citation2021). These spaces of identity-making represent tensions and possibilities for young people, who are transitioning into adulthood in late modernity.

This paper aims to contribute to this growing discussion and debate that young people are engaged in as they navigate gender structures and ontologies of gender. In a science gallery exhibition confronting the intersections between gender, science, and biomedicine we invited young people (16-35 yrs) to contribute what gender meant to them as a picture or text in the gallery space. We examine engagement in this public exhibition where young people actively brought their perspectives into dialogic encounters with each other, through participation in a physical display in Science Gallery London which sought to de-centre fixed binary gender categories – a site where gender is explicitly being ‘redone’ (West & Zimmerman, Citation2009). In exploring participation in this gallery we draw on recent work on curation (Acord, Citation2010; Puwar & Sharma, Citation2012) to explore how young people engage in re-curating the narratives presented to them as a way to make sense of gender (im)possibilities and discourses of gender as they transition into adulthood in contemporary society. We argue that re-curation in the gallery is of interest as it surfaces practices and doings of gender that are situated within the everyday, grounded in and informed by experiences and knowing – lived expertise. In this way recurations represent the relational ongoing processes associated with re-curating gender in society that have, in this context, extended into the gallery context: Gender emerges as static and dynamic, certain and uncertain, as well as liberating, limiting and ambivalent. We surface the ways these perspectives interact and talk to the multiple levels of social processes where gender is reproduced, drawing on Risman’s (Citation2018) framework of gender as a social structure, which locates gender as occurring across individual, interactional, and institutional dimensions. Accounting for the onto-epistemological interconnectedness of both being and knowing, we draw on Lim and Browne’s (Citation2009) conceptual work on ‘senses of gender’ to make sense of the ways young people are engaged in knowledge production, and by extension doing gender. Our method surfaces the ways gender gets reproduced across these multiple dimensions, and the affective qualities and frustrations associated with gender ontologies that emerge across them, in a setting (gallery) where gender is being redone. In these moments we argue we can see emergent (and continuing) cultural scripts about gender and its (im)possibilities. In short the paper interrogates and surfaces young people’s perspectives of gender.

The site and exhibition

This research took place within Science Gallery London, a gallery that opened in 2018 and is positioned within a major pedestrian thoroughfare next to London Bridge Station. The gallery operates as a ‘public-facing facility connecting art, science and health to foster innovation in the heart of the city’ and their ‘key audience is young adults’ (Science Gallery Website, Citation2022). A critical aspect of the gallery is that it is both physically positioned next to a hospital, partners with hospitals and trusts, and has, as part of the broader ‘Science Gallery Network’, a goal to ‘ignite creativity and discovery where science and art collide’ (Science Gallery Website, Citation2022). This is important as exhibitions and work within the gallery explicitly seek to engage with ideas in relation to health, and how the ideas presented have been (re)produced within the context of health settings.

In January 2020 the gallery hosted an exhibition titled ‘GENDERS: Shaping and Breaking the Binary’, which is where the research for this project was undertaken. The exhibition ran from 13th January and had intended to run until 28th June, however due to COVID-19 restrictions it was closed in March 2020. Exhibitions are, as Greenberg and colleagues point out:

Part spectacle, part socio-historical event, part structuring device, exhibitions … establish and administer the cultural meanings of art. (Greenberg et al., Citation1996, p. 2)

This exhibition sought to present ‘a playful and kaleidoscopic view of genders and its relationship with science’ with the goal to examine ‘ideas of gender today’ (Science Gallery Exhibition Website, Citation2022). The exhibition included 15 pieces – photographs, artworks, and interactive installations – that were curated to engage the audience ‘in discussions that renegotiate our experiences of gender, and imagine alternative realities’ (Gallery Exhibition Booklet). These were situated across four themes:

‘Porous bodies and Queer Ecologies’,

‘Gaming and Role Play’,

‘The Exchange: Re-imagining repro-tech’, and

‘Everyday gender expression’

In each theme the artworks sought to locate gender and its (re)production and disruption through thinking about gender as experienced within and across on/offline environments, and bring into question biological determinist frameworks that underpin health and biomedicine. The exhibition offered an explicit space to think about existing or alternate ontologies of gender.

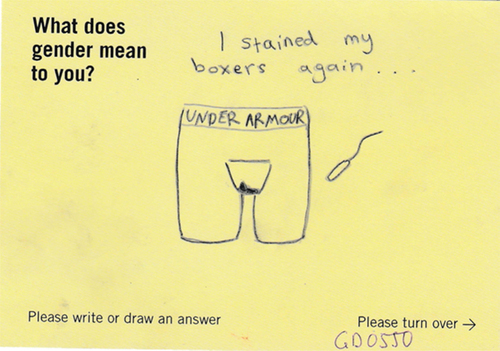

As visitors moved through the gallery space they were invited to participate in this research project – an interactive exhibit in the centre of the gallery. The project enabled visitors to add text or a drawing to a postcard sized piece of paper that posed the question ‘What does gender mean to you?’. These were subsequently displayed in the gallery to be seen by other visitors. Of the gallery visitors 516 young people (16–35) completed this activity. We discuss this throughout this paper as re-curation, as a conceptual tool to make sense of the ways gender is being re-curated in everyday lives.

Curation and Re-curation

In this paper we are framing the young people who participated as re-curators of ideas within (and beyond) the exhibition space. The idea of a ‘curator’ has shifted over time: from ‘overseer or carer of a collection’ to more recently, an ‘active producer’ of knowledge (Puwar & Sharma, Citation2012, p. 40). As Acord (Citation2010, p. 454) suggests, modern curators:

[M]ove artworks around during the installation in order to achieve two things: an overall sense of the exhibition as ‘feeling right’ and appropriate relationships between neighbouring pieces. This decision-making process blurs considerations of the symbolic meanings of particular artworks and their aesthetic properties.

What is critical here, is that the curator actively produces meaning in a space, and seeks to open up space to stimulate debate and ‘dialogue by bringing artists, places and publics together’ (Puwar & Sharma, Citation2012, p. 40). This conceptualization is important, because like the Science Gallery London in this study, curation is about active and participatory engagements, where the actors – both humans and objects – create space for dialogue around certain themes (i.e. gender). This pushes back against more traditional gallery spaces – ‘the normative curatorial framework of didactic or educative leisure’ (Franklin & Papastergiadis, Citation2017, p. 684). In this way, curators curate artworks, which ‘activate’ the ‘physical and discursive space of the exhibition’ (Acord, Citation2010, p. 456). This gallery was initially curated by Helen Kaplinsky, who sought to examine ideas of gender across themes that spoke to representations, categorizations and limits of gender imagination by curating an exhibition in a particular way. Of interest to us is how young people were brought into this space to actively (re)produce and re-curate meaning in the space through this research project.

We use re-curation to make sense of the action of participation in this exhibition, but more broadly, to point to the ways that gender gets re-curated and brought into existence in everyday lives. In the exhibition young people acted as re-curators through reworking the physical and discursive space by their participation in this research project. Our interest in this study was examining young people’s representations of gender with the exhibition themes, which sought to provide alternative narratives of gender in a space where gender is being ‘redone’ (West & Zimmerman, Citation2009). By putting physical cards on a table, spreading them out, and pinning them to a wall in the centre of the gallery young people re-curated meaning by having the opportunity to juxtapose codes and (re)write them, and talk to the construction of gender in a health gallery. Acord (Citation2010) suggests ‘the crux of curatorial practice in contemporary art is the construction of artistic meaning through the exhibition’ (447) – it is the multiple meanings and lenses of gender, and young people’s experiences of it in everyday life where they are curating identity, which enter into the gallery and which this project surfaces. Prior to sharing the findings from this work, we examine the socio-historical conceptualizations of gender, as a way to make sense of these gender re-curations in this project.

Gender

The question of what it means to be of a gender was laid before the law in 1969. Sir Ewan Forbes, a transgender man, contended his right to inherit the family estate through primogeniture (Playdon, Citation2021). At the time, the medical community valued the importance of ‘psychological sex’, or self identification, as recognition that biological sex is by its nature a complex phenomenon (174). This stance influenced the judge’s determination of Sir Ewan Forbes’ gender. However, a later court ruling regarding the divorce of April Ashley, a transgender woman, from her aristocratic husband narrowed the legal definition of gender to precise biological attributes to deny her designation as a woman (Playdon, Citation2021). As a result, the medical understanding of gender curtailed this reductionist biological determinist viewpoint which continues to prevail today.

We start with this vignette as a recognition of the ways gender is made through participation in everyday spaces and is subject to socio-historical categorization, membership, and class (see for example: Heyam, Citation2022). These are key aspects to sociological approaches to gender. In 1987 West and Zimmerman put forward the concept of ‘doing gender’, which

[I]nvolves a complex of socially guided perceptual, interactional, and micropolitical activities that cast particular pursuits as expressions of masculine and feminine ‘natures’

They argued that gender gets re-produced socially and occurs through interaction – the display and social regulation of sex. In later work they have emphasized that ‘the key to understanding gender’s doing is accountability to sex category membership’ (2009:116, italics in original). Making a distinction between sex, sex category, and gender, they argued sex was determined through societally defined biological distinctions, which usually occur at birth. Sex categorization, in contrast is used as a ‘proxy’ for sex, and is the socially regulated display and performance of gender to be accepted as claimed. That is, a sex category requires the doing and performance of gender, which includes physical appearance (i.e. hairstyles) as well as behaviour.

If social contexts enable the doing of gender, then debates that followed asked about the limitations of focusing solely on the doing of gender. Francine Deutsch, for instance, has argued that ‘doing gender’ has been conceptually useful to think about making sense of gender conformity and its reproduction, but has been limited in its capacity to account for social change:

‘Doing’ is an excellent word to emphasize that gender is created continually in ubiquitous ongoing social interactions. However, if ‘do’ refers to something that is accomplished, or brought about, then ‘doing gender’ will bring to mind the accomplishment of gender difference rather than the dismantling of difference.

Deutsch argues therefore for using the concept ‘undoing gender’ because of its capacity to evoke resistance. Risman (Citation2009), drawing on Deutsch’s work, has argued similarly, suggesting that ‘doing gender’ ‘creates conceptual confusion as we try to study a world that is indeed changing’ (Risman, Citation2009, p. 82). In doing so Risman argues for ‘undoing gender’ as a productive lens to think about the ways gender is changing and/or the ways it is being undone – through examining the ways traditional scripts are not followed within their cultural settings. However, in response to this argument, West and Zimmerman (Citation2009) have argued that we cannot ‘undo’ gender, but gender can only be ‘redone’. In making this argument, they argue that undoing is not possible, as this implies ‘abandonment’ of sex category membership, as being ‘no longer something to which we are accountable (i.e. that it makes no difference)’ (117).

A common thread across this scholarship has been a focus on sex category, and the ways that gender is positioned surfaces (im)possibilities within everyday spaces. Risman’s (Citation2004, Citation2018, Citation2013) work is useful here, offering the conceptual framework of gender as a social structure, which accounts for and emphasizes the impacts on (im)possibilities based on sex category at differing levels of social processes:

The gender structure differentiates opportunities and constraints based on sex category and thus has consequences on three dimensions: (1) at the individual level, for the development of gendered selves; (2) during interaction as men and women face different cultural expectations even when they fill the identical structural positions; and (3) in institutional domains where both cultural logics and explicit regulations regarding resource distribution and material goods are gender specific.

The ‘multidimensionality’ of this theory captures the complexity of gender as a dynamic structure – that is operating at the ‘individual, interactional and institutional levels’. As Risman (Citation2018) articulates, this provides a framework for thinking about the ways that these differing levels (or dimensions) overlap in symbiotic ways, but also the ways they can have dialectical relationships to each other.

A key aspect of this project is to examine young people as actively engaged in knowledge production, and representing what gender means to them, which is about knowing as much as it is about doing. This requires taking into account the onto-epistemological interconnectedness of being and knowing, where knowing is part of a material engagement with the world (Barad, Citation2007). Lim and Browne’s (Citation2009) concept of ‘senses of gender’ is useful here. Senses of gender locate gender as both an embodied set of phenomena as well as internal feelings and understanding of gender within one’s own head. This is not about a mind/body dualism, rather as Lim and Brown suggest, ‘senses of gender emerge in between bodies, discourses, institutions, technologies, expectations, experiences and thought’ (83). Senses of gender enable multiplicity, but also locate gender socio-historically and situated. We draw this out in this paper, exploring how the gallery, and (re)curations in it, reveal representations that surface tensions, ambivalences, uncertainties and limitations in relation to both the being/doing and knowing of gender.

Through this we examine the ways that young people’s perspectives intersect across the dimensions of gender as a social structure, making sense of where young people are locating gender and its power and effects in everyday contexts and settings.

Methods

Our aim in this study was to examine how young people were re-curating gender in a gallery exhibition focused on redoing gender. We sought to understand the ways young people understood gender, and positioned and experienced gender. In the Science Gallery London, people who attended the exhibit were given the option to draw or write on a postcard sized piece of paper a response to the question ‘What does gender mean to you?’. On the reverse was information about the study, and two open text demographic questions (gender, age). The method was developed in collaboration with the gallery, so that the postcards became part of the exhibit, and were placed alongside the existing artworks in the gallery (see below for an image of the postcard, ).

In total we had 637 postcard submissions. To focus on young people’s experiences, who were the target of the gallery, we excluded postcards outside of the age range (16–35), resulting in 516 postcards in total. See for an overview of the participants’ gender as reported. Notable here are the ways gender was categorized by participants and their participation (or not) in locating themselves in relation to gendered/sexed categories. It is notable for instance that 35 respondents used ‘cis’ as a prefix, that 19 were ambivalent or uncertain (either about their own location, or locating themselves within a category), 21 were not easily categorisable and used terms such as ‘apache helicopter’, which could be read as a transphobic joke, as well as indeterminate phrases such as ‘a bad bitch’ and ‘alien’, alongside drawings as a response to requests for categorizations. 131 chose not to answer, perhaps intentionally dislocating themselves from pre-set categorizations. There was also variation in that some participants described themselves using gender categories of ‘man’ and ‘woman’, and others sex categories of ‘male’ and ‘female’. While these terms are sometimes conflated, the authors consider gender to be the sense of self, whereas sex as genital phenotype.

Table 1. Overview of respondents.

The study had ethics approval from King’s College London: MRA-19/20-17198.

Analysis

We drew on Adele Clarke’s (Citation2005) framework for mapping visual discourses. This method allowed us to deconstruct the images and text written on the postcards to make sense of them within the context (i.e the gallery) in which they were situated. To do this we first took a sample of the cards with drawings and text (n = 100) and examined these according to Clarke’s criteria – writing memos to produce a narrative frame (‘big picture memo’) and wrote a ‘specification memo’ to deconstruct each text using specification criteria to “analytically ‘break the frame’ so that we can ‘see’ an image in multiple ways” (Clarke, Citation2005, p. 227). This created a preliminary thematic framework. We then coded half of the postcards each, identifying existing themes and new emergent themes in the sample. We then double coded all the postcards to ensure intercoder consistency. Inconsistencies were discussed and resolved.

The final themes that emerged were: gender as experienced internally and externally, gender as enacted through structure and agency, and gender as productive and unproductive classification. What was striking was the ways the themes encapsulated a debate or dialogue about gender, and its location(s) in society, and the ways it was felt and lived across varied levels (individual, interactional, and institutional). We discuss the findings in detail below showing how these speak to the ways that young people are making sense of gender, the tensions that emerge, and the ways they participate in and resist dominant constructions of gender.

Gender as experienced internally

Gender was located within the body by participants either through it producing affective experiences for them, or by situating it as an endogenous identity. In this theme participants did not view gender as a character to be assumed, but rather framed the gender structure at the individual level as a metaphysical essence that is omnipresent in society.

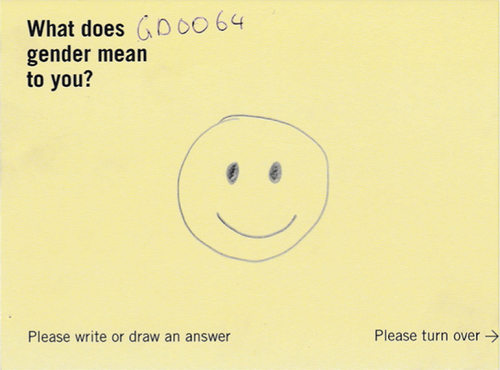

For some participants, the concept of gender produced affirmative feelings, imparting a sense of belonging (Female cisgender, 26) and love (no gender/age reported). One responder represented their idea of gender as a smiley face ().

Exhibiting apparent happiness here, emojis are commonly used to converse in online spaces where the recipient often does not see the sender; a happy emoji confirms the status quo. Emojis, and particularly this one, often have no evident gender markers. A smile here might also be conceived of the emotional labour or work produced as a gendered subject – a facade, with the participant perhaps projecting what they are expected to portray in order to maintain their sex category membership: ease with and acceptance of their gender. However, they may be hiding inner turmoil and discomfort behind this mask. The diverse readings of this emoji represent the complexity of ways gender is experienced internally associated with uncertainty, ambivalent, adverse and affirmative imaginings.

A few participants left their postcards blank, possibly to signal uncertainty. Others explicitly equated gender with a feeling of confusion (Female, 31): symbolically ??? (Non-binary, 29) and ¯\_(ツ)_/¯ (Agender, 29), or stating I don’t know yet (Female, 18) and IDK (Male, 19). By describing themselves as beyond the gender binary, the participants are purposefully undoing gender by positioning themselves outside the accepted sex categories. Some participants related to their feelings of indifference about gender:

I’m not really sure. My assigned gender is not at odds with how I feel so it’s not been a challenge to live as a ‘man’. But I’ve never felt a strong connection with it either.

What the hell is a gender? (Is it not enough that I’m here?)

The experience of gender here seems to transcend the corporeal and is construed as something intangible and ungraspable. Others expressed their ambivalence by drawing on both affirmative and adverse emotions.

Something felt. Something fluid. Sometimes certain. Often something fluctuating between uncomfortability* and euphoria.

*can also be described as aheartbreak

A friend when you need it. A bully when you don’t. (Cis male, 31)

This enigmatic view of gender leaves it open to interpretation in a way that wasn’t shared by all participants. For some, gender summoned distinct feelings of stress (Trans male, 17); erasure; a headache (27); and unnecessary pain and suffering (non binary, 16). Strikingly visceral reactions surfaced:

Fuck gender and how being put in boxes has been holding me back for 6 years

Die, Gender, Die

‘The, Gender, The’ - Sideshow Bob

A sense of entrapment and torment arises from these responses in how gender as a social structure malaligns with their identity and/or the place it occupies in the world. It is apparent how for these responders, their sense of gender has been deployed in ways that limit their sense of agency. For them, sex category membership is undesirable. Gender here is not something done by people, rather it is done to people. These tensions between the individual and institutional levels of the gender structure was called to attention by one participant to whom gender means:

Comfort within yourself understanding how you view yourself

How society views you, whether you like it or not – we live for the comfort of societal structures not the individual (Female woman, 21)

For those caught between these levels, living within the gender structure is a double edged sword, both enabling self understanding yet disabling legibility among those around us.

Gender as experienced externally

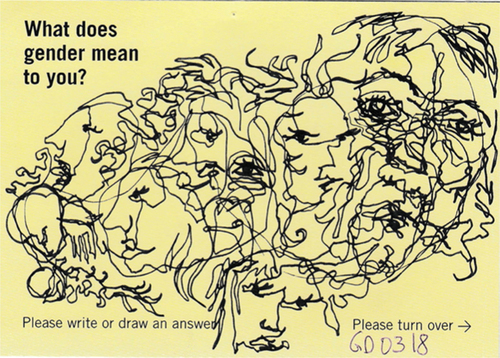

In other instances, gender was positioned outside the body, produced through interactions and in relation with the world. This relational nature of gender is illustrated in

From afar it appears to be a disarray of convoluted lines with no apparent purpose. Yet on closer inspection, faces become visible – interposed on each other, converging, fading in and out as the eye wanders over different areas of the drawing, with the intertwining lines making the faces not fully distinguishable. Akin to knotted hair, it becomes difficult, almost frustrating, to undo and unscramble the drawing. Providing a sense that there’s always more to discern the longer every nook and cranny is explored, it’s emblematic of how gender (and our accountability to sex category membership) is weaved into the fabric of society so intricately it can’t be simply removed with a seam ripper.

A dominant aspect to come out of these exogenous representations of gender was the role of gender as a social construct. As one young person put it, gender is a SOCIAL construct with REAL consequences (Female, 20), or as another indicated, gender is socially constructed, driven by stereotypes (Female Ciswoman, 22). For example, some participants positioned gender to reside on the body surface: It’s just body parts (Female 21) and Mostly [drawing of two breasts and one penis]. From this viewpoint, access to sex category membership is derived purely from our bare outward appearance.

Others had more abstract interpretations of this, positioning gender as an expression of one’s identity in the form of appearance and behaviour, whatever that means for one. Relating the idea of gender to clothes and conflicts caused by them was a common occurrence.

Being judged when I where [sic] clothing of the opposite gender (Female, 22)

[Drawing of a bra, underpants, t-shirt, and trousers hanging on barbed wire] (Female, 26)

Notable here is the symbolism of participants trying to push societal boundaries, and encountering resistance from those around them. The barbed wire evokes the impression of a sort of penal institution, with the clothes on display as a cautionary warning to not deviate from the style permitting access to one’s sex category membership. Gender here is not produced by individuals, but results from synergy within a society.

With a more philosophical viewpoint, some participants perceived gender as an interface for connecting with the world. Neither good or bad in itself (?, 28). It is notable that this participant referred to their own gender as ‘?’, in a way avoiding picking a side themselves by dis/locating themselves from pre-existing categories. Another participant explained that to her, gender is

a language, a discussion between what people understand by symbols and what I’m trying to say by using them.

The conundrum posed here is that language can be malleable with new terminology and meaning invariably evolving, but where vocabulary does not yet exist, this can limit gender (im)possibilities. As one responder lamented, gender to them means being forced into a box every time I speak my native language (None (I wish), 22). The act of discourse emerges as a point of gender production, albeit pernicious in this instance. While the participant seeks to undo gender by wishing to relinquish their sex category membership, the constraints of their native language hinder this.

Another participant related that gender is something for the world to identify me with [open-mouthed emoji]. The shocked emoticon conveys a sense of bewilderment at the palpable dominance that wider society has on their personhood. Gender is reduced to a tag (Hetero, 19), labels put on us to fit into the system (female, 22). As one young person elaborated,

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about my gender as a cis person, and have realised I only identify with womanhood b/c I identify with the mother that came before me.

The doing of gender occurs in the sense that it is passed down and redone between generations, like a family heirloom. Conversely, reminiscent of a tag identifying an item in a store, gender could be seen here in some ways as a pre-forged mould for us to occupy. Participants had varying attitudes towards this:

We extracted gender roles and meaning from our very initial human civilization (Female, 22)

What a woman can and can’t do, what she should do and what she is, has been defined by men a long time ago. (Female (should be irrelevant shouldn’t it?), 20)

I was born a girl and learned to be a better girl. The ‘girl road’ was already existed and help me to develop my personality based on this (Female, 24)

Although gender is posed as a learnt construct (Female, 20), the pliability of this construct – and opportunities to redo and undo gender – remains debatable. Regardless of how veritable this is, gender is postulated as not occurring in isolation. As one participant depicted his sense of gender,

[Drawing of a square box with double ended arrows connecting the inside and outside.]

This symbiotic portrayal of the relationship between the individual and interactional levels of the gender structure illustrates that they do not exist in a vacuum, but instead influence and impinge on each other.

Gender as enacted through structure

Narratives of gender being determined by the physical body were represented at differing levels, ranging from chromosomes, to reproductive organs, and depictions of other body parts. Drawing on science as a scholarly discipline, some participants converged sex and gender while others raised clear distinctions between these as two conceptually separate terms.

One respondent described gender as being ‘the X, Y chromosomes you’re born with. Anything else isn’t/shouldn’t be a concern’ (Female, 24). Bringing together sex and gender, these distinct identifications of the sex categories illustrate how sacrosanct they are to some people. This univocal depiction of gender draws on the authority of biology as a scientific discipline often viewed as a set of unarguable and unchanging facts in gender discourse. Gender as a concept in such postcards is predetermined and firmly set in stone. Yet, there is no inquiry as to why meaning is attributed to chromosomes, and what the significance of this meaning is.

One participant highlighted the complex reality of living organisms, adding nuance from both a sociological and biological perspective:

[Gender] Means combination. It is kind of self recognization and self management during your development ♂♀, ♂♂, ♀♀ XYY, XY, X, XO

While citing the role of chromosomes in forming an individual, the respondent recognizes that variations in chromosomal arrangements are possible and that there are external factors contributing to the production of our genders. Instead of biology being positioned as immutable and binary, it is being undone here. Gender (and sex) is described as an entangled bio-social process rather than a singular, pre-existing entity that can be embodied.

Alternative interpretations of gender made distinctions between the physical body as an inherent trait, and the personhood of an individual:

Medically: the sex you are born with whether it’s one, the other or both. In all the other aspects: what you identify as

An identification you feel comfortable in. Not necessarily your chromosome arrangement.

Biology is not viewed as a delimiting factor here, but rather as separate to our identities. By making a distinction between the body as simply being a material thing and the mind as capable of contemplation, these responses draw on the Cartesian dualism of mind and body (Mehta, Citation2011). On the one hand, gender is presented as a scientific, impersonal object devoid of individuality, but on the other it is also seen as a philosophical, elusive essence.

There were also allusions to narratives shifting away from the conflation of gender and sex. One responder’s perspective was that gender is ‘Your sex’ - I’ve grown up knowing that ‘gender’ means this … (f?, 30). The open endedness of this response leaves space for this viewpoint to be questioned and alternative answers to emerge, with a recognition that this shifts with development of identity. In another card one young person notes: …I’m not sure and its okay to say your [sic] not sure (cis female, 20), recognizing gender as a concept that is being made sense of within their lives and the gallery space they are immersed within.

Indeed, one participant detailed how the exhibition provoked them to re-think their understanding of gender:

Before visiting the exhibition Gender, to me, meant a type/set of reproductive organs, bodily features, hormone releases, but now, I see these things to be sex & gender to be a choice

The partition of sex and gender as distinct entities works to disembody gender as a concept. Another participant noted the non-physical ways in which what we might call a genderfication manifests, observing gender to be the direction of societal pressures that are placed on beings from infancy (fluid, 27). Surfacing the doing of gender in their response, the participant conscientiously undoes gender in dislocating themselves from the gender structure.

Gender is disembodied with the inference that it is an immaterial entity within society which is passed down through the generations, though paradoxically, by virtue of this synthetic reproduction of gender as mimicry of those around us, it becomes embodied (and done) in the way that individuals behave and live their lives.

To one responder, for example, gender is a broken mould of forced show and tell (female, 22). For her, there is something untruthful about gendering bodies and putting on a fake act for the sake of not defying societal expectations. The apprehension of ostracization from society for not doing gender in the appropriate way is apparent in such responses. However, the acknowledgement of knowing is also about agency, as put by one participant: Gender is … what you want people to believe is in your pants (male, 22). Here, the idea (and awareness) of cultural scripts is used to empower people to present themselves as who they want to be, not who they ought to be.

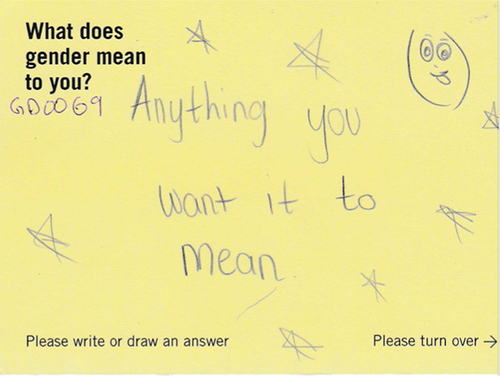

Gender as enacted through agency

In (see below), the stars are reminiscent of a night sky with its vast openness and space for unlimited opportunity. The implication contained in this drawing – that we are all entitled to decide our own genders – was reinforced by some participants actively advocating their lack of interest in other people’s genders. One respondent stated that gender to them means,

Not much. I feel like people should be able to decide without society judging them - who cares really?

For others it was an equally straightforward answer: I don’t care it’s your choice innit. Another participant succinctly summed it up as, Live & let live (non-binary, 24). The respondents here can be seen to be going towards completely undoing gender, by suggesting abandoning it. Yet the suggestion that gender is a free choice is also problematic as it delegitimizes internal experiences of gender by inferring that an individual’s sense of self is not an authoritative source. Far from liberatory, the implication from this is that both being and not being transgender is a choice, delegitimising lived experiences and ones sense of gender. However at the same time, this carefree attitude, or position as a ‘rebel’, as Risman’s (Citation2018) work might argue, works to accommodate an opportunity for diversification of gender. Individuals are empowered to make their own conclusions as to what gender is and what it means for any one person: Gender is what you make it.

These young people do not imagine a need to contort themselves to fit into a broken mould, but rather are they able to own their genders and make gender fit them. In a sense, this interpretation of gender as pliable and supple turns it into a plaything that can be kneaded and sculpted and forged in a process of self discovery and maturation. As one responder described it,

Gender is an applied concept with which to modulate and experiment until a destined identity is reached

The responder described gender as a process of becoming rather than an immutable state of existence, cultivating a sense of undoing gender. For others, participating in this exploration is harder.

I am a straight forward enough ‘man’ with a beard but I do consciously wear blokey colours when sometimes I’d rather wear pink/yellow/light blue ones so …

A tension emerges here not only between masculinity and femininity, but also how the participant perceives themselves as opposed to the world around them – that despite their occasional preference for pastel colours, read as non-masculine, they opt for the blokey colours they believe are expected of them to retain access to their sex category membership. In contrast to this self imposed restriction, one participant was of the opinion that clothing provides a safe(r) space for versatility and exploration:

As you choose what you wear, there is always room for everyone to put themselves in somewhere comfortable, which anything can be ‘an expression’ in

A number of responses related to confronting the commonly imagined division of male/female and masculine/feminine as separate, distinct boxes, intentionally complicating the existence of binaries:

[Gender] puts people into little boxes on what we associate. It should be explored, it should be questioned. There aren’t two genders

Such participant responses speak to how these young people are pushing back on binary logics, and complicating stereotypical masculine and feminine traits to redo gender. As elaborated by one responder,

Boys can be pretty. Girls can be strong. Gender isn’t genitals. Basing our preferences and opinions on someone’s genitals sounds perverted when you think about it. When you can be anything why would you be gendered?

For some, defying long held views of masculinity and femininity by amalgamating them is not so much an active choice, but rather a fact of life as seen in (below).

Undoing and redoing gender are presented as natural progressions of the human experience. Yet for some participants, these visionary advancements come too late. One responder reflected, ‘I guess I feel a bit slighted by gender norms growing up … I feel like I never got to make the choice not to wear a dress’ (big man, 30). Rather than having the flexibility to use gender as a process of self discovery, stereotypical gender norms constrict who these participants are/were allowed to be(come). This brings into question to what extent we truly have a choice about our gender if we are labelled as gendered from birth, and at the same time, the types of futures these young people imagine for themselves and those following in their footsteps.

Presently, we have considered interpretations of gender on the level of the individual and interactional level – how people make sense of and construe the significance of gender within themselves and in relation to the world around them. For the remainder of the paper we will examine gender on the institutional level – its perceived role and function within wider society.

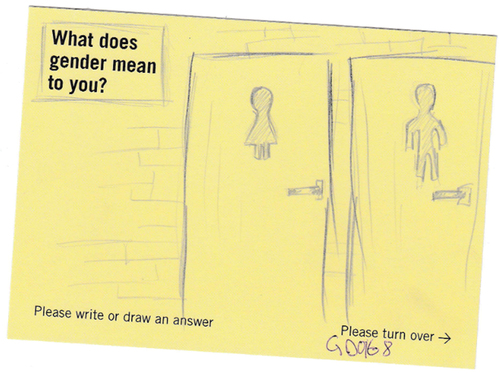

Gender as productive classification

Where gender was positioned as productive it was often because of the functionalist role it performed in society. As one young person outlined, gender to me is the role you play in procreation – if you make someone pregnant or you get pregnant (Female, 24). Other participants drew pictures of people with male and female characteristics with plainly defined genitals setup in clear binary distinction to each other (Cis, 30) and stick figures displaying intent to have sex (♂, 32). These are physical manifestations of how gender is seen to be done. Gender here is almost described akin to a material good with transactional value. Yet for others this perception left a bitter taste:

Arbitrary roles, associated with one’s sex, but convenient for the function of society

It’s just something that was made up to make the world simpler it mostly just made it more complicated

Although there is recognition for how gender came to be on the institutional level, the responders also convey a sense that gender to them has more of a cultural meaning in the sense that it is a way of life rather than a thing that can be possessed. A critical perspective that emerged in relation to this was the utilization of gender as a mechanism of control in our patriarchal society (F, 30). It was seen to cause a divide (F, 19) by representing both inclusivity and exclusivity (Female, 22), thereby serving as something to segregate us (Cis female, 24).

I don’t know. I don’t have one. I’ve never understood the concept. Gender is an invention for the purpose of control.

[Gender is] the constructions of social binaries which help [us] make sense but also divide us

Illustrated in is a classic example of such a partition. The basic function of a bathroom is to provide a dignified space for eliminating bodily waste, yet it is being co-opted in enduring debates around access to gendered locations.

In this response, the box around the research question implies that it’s a closed subject; there is a way that gender is intended to be done. Indeed, one argument against guarding access to bathrooms, is that it is cisgender people who are redoing gender who will be harmed most. To one participant, gender

Means I have to go to the ladies toilet but sometimes I want to go to the men’s to have a look! [emoji with tongue sticking out]

This seemingly tongue in cheek comment underlines how the concept of gender is employed to police our behaviour and actions within society. Although the respondent positions themselves outside the gender binary, they feel only permitted to enter one bathroom on account of their sex category membership. In spite of their curiosity to investigate the other bathroom, they appear to not have felt sanctioned to actually do so.

For others, the act of being under an apparent gaze feels like a PRISON (Enby, 27); a restriction [drawing of stick figure behind bars] (Female, 26); oppression (Female, 25); and a hijacking of their true selves. The fear of wrongdoing and thereby risking loss of sex category membership is palpable.

The power relations described here were directly called out by some participants, defining gender to be the construction of power and powerlessness (Woman not ‘girl’, 28) and irrelevance structured by those who seek power (Female, 21). As one participant expounded,

Gender is the unnecessary dogma that each unique human must be compartmentalised in order to keep them under control

This questions to what extent gender really can be redone or undone, if these changes can only occur within a predefined territory. Yet disruptions to the perceived authoritarian gender structure also surfaced:

Free people shall not be confined by the genes in the body! [translated from Chinese]

The idea of freedom and agency as linked to freedom from socially constructed biological markers is important, and highlights the ways that gender is imagined as operating for utilitarian purposes, disciplinarian purposes, and in so doing results in power (im)balances.

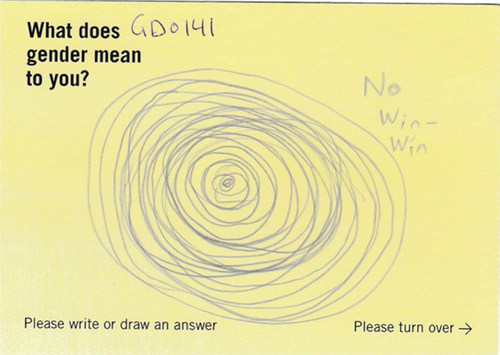

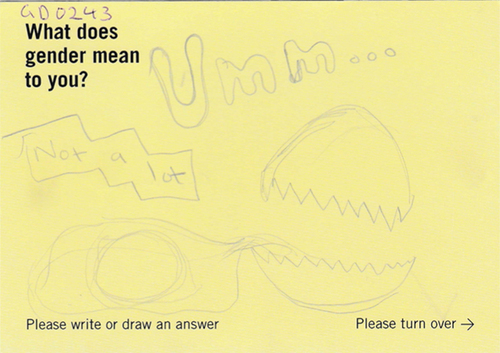

Gender as unproductive classification

In contrast to a productive narrative, the concept of gender was also positioned as a hindrance preventing individuals from thriving. A participant in their 30s denoted gender as a miserable little pile of problems. Another respondent described gender as a social construct with real consequences [spider web drawn in background] (female, 20). This notion of a human created cobweb ready to entangle unsuspecting prey speaks to the powerful ways that gender impacts individual lives.

The seeming inability to stray beyond these imagined boundaries, arguably, prevent these individuals from fulfilling their potential. Another participant echoed this sentiment:

Gender is a social construct that is foisted on individuals to try to uphold a very traditional and static way of being - and with great cost to individuals who don’t fit into a strict code of binary adherence

Those who dissent historic gender conventions face the dilemma between penalties being imposed on them for doing so, or enduring a personal forfeiture for abiding by the expected customs of their sex category. Unlike other responses which posited gender as a sense of becoming – an evolving process through space and time – here gender signifies immuration and stagnation. As reflected in , this can feel hopeless.

A different account of gender as unproductive, was the connotation that gender itself is a defective concept, and therefore does not serve a useful purpose. For some, gender is posited as an outdated ideal at odds with contemporary society. One respondent suggested that the concept of gender in our modern world does not function. It needs to be rethought from scratch (female, 26). This call for gender to be wholly redone was endorsed by others: Gender is a construct and we should tear that construct apart (female, aged 21). These views situate gender as a historic paradigm which has been outgrown by the needs and awareness of a modern (Western) culture.

In other sections of this paper we have discussed the multiple and varying ways of how gender can have deep, personal meanings to individuals. A smaller proportion of respondents, however, felt that gender is (becoming) meaningless, explicitly stating that gender means ‘nothing’. Below, speaks to this lack of personal interest.

The egg can be seen to embody the creation of a new life, though the raw, immature insides depicted could also represent the obstruction of a new life developing and taking shape by having its outer shell broken prematurely. Reminiscent of the saying ‘one can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs’, this visual also hints at the ways that the concept of gender has caused much malignity and division in our society. Within the trans community, ‘egg’ is a slang term for individuals who have not yet realized they are transgender; the cracking of the egg can symbolize their coming out, an act that can be perceived as proffering themselves up to either disregard or change sex category memberships.

Other respondents also noted the meaninglessness of gender with one declaring that ‘we’re all going to die eventually, nothing has inherent meaning, the universe doesn’t care what genitalia you have’ (female, 19). A young person suggested that gender means 25 things in the survey drop down (♀, mid 20s), hinting that the increasing number of labels utilized to redo gender reduce their inherent meaning by blurring the distinctions between them. To another participant, gender is ‘just grammar innit’ [sic]. These responses depict a sense that the use of gender to label people is not grounded in any reason. What these responses disregard, however, is that not everyone has the ability to freely uncouple the act of being labelled a specific gender, from the impact of living with gender.

Overall, I think gender is an irrelevant label used to separate people needlessly. However, if you have a gender that the majority discriminate against, it is painfully relevant & somewhat inescapable

Living in gendered institutions where gender is rooted within policies, practices, and power distributions requires redoing the foundations on which the institution is built, instead of merely altering processes to emulate gender differences (Acker, Citation1992). The historical significance of gender therefore cannot simply be erased because there is a shifting viewpoint towards gender being nugatory.

A social construct, by definition, is an idea created and accepted by people in a society. If collective attitudes towards gender are evolving, this can be seen as its own process of becoming – emblematic of a wider cultural shift towards a postmodern era of gender liberation. Gender liberation here, at least for the young people in this study, is generally not meant to be seen as living without gender, rather, that we live in harmony alongside gender. In this sense gender is redone in the way that West and Zimmerman (Citation2009) propose. People would be free to make of gender what they wish, without gender being used to vilify and divide. Gender could simply be, without having to be.

Discussion

In this paper we have examined how gender was recurated in an exhibition within a science gallery, which sought to explicitly disrupt binary notions of gender. In the themes from the postcards that emerge we see the ways that gender is both legitimized and (intentionally) de-legitimated in young people’s lives. The recuration which takes place involves gender being put back together and reassembled in physical and discursive spaces, demonstrating the (im)possibilities of gender for young people, and the ways it is understood in their lives. These depictions emerge scattered across the table and pinned to the wall, juxtaposed against a gallery space that curated an exhibition to break binaries/categorizations down. Re-curation of the gallery space here is part of the ways that gender is being re-curated across everyday contexts and settings and made sense of, felt and experienced, and refashioned into lives – the ‘senses of gender’ that are at once embodied, felt, and inside one’s mind (Lim & Browne, Citation2009) allowing us to make sense of both being and knowing.

One of the critical findings in this paper is the very differing ways young people understand and position gender, which we have discussed as part of a broader debate or dialogue that they are participating in as they are transitioning into adulthood. In a gallery focused on redoing gender, or where gender is being redone, it is notable that for some they emphasized the fixed nature of gender, and adherence to gender as a social structure. However, we also documented the ways that young people are being critical and frustrated by the gender structure, and its emergence at the individual, interactional and institutional levels, and how it is felt and perceived. That it emerged in these three ways support Risman’s (Citation2018) theoretical work, but also extends this work by tapping into the felt and affective experiences that young people have at these levels, and their belief systems which enables (and constrains) imagined possibilities for gendered futures. It also points to the persistence of sex category as critical in these narratives, signalling the omnipresent presence of gender in society, but also the ways we live with gender and do it; how we articulate senses of gender.

That gender is imagined as both fixed and unfixed, productive and unproductive across the voices in the sample is a critical finding. It points to the difficulties and centrality of gender in youth lives, but also the diversity of ways they are making sense of gender, and living it as they transition into adulthood. Indeed we must take these understandings of gender seriously – the expertise young people provide based on their lived experiences is a critical lens to talk back to our current theoretical approaches. Specifically there is, as discussed, an ongoing debate about the doing, undoing, and redoing of gender. Based on the data in this paper it seems more apt to re-position these debates as perhaps multiple sides of a die, representing variations of experiences of young people, whose worlds allow the undoings, doings, and redoings to co-exist. The reassembling work that is being done maintains gender norms, as well as unravels them, and enables them to assemble new futures. The ‘senses of gender’ that are embodied and felt are produced in the socio-historical space in which these young people are living.

An important aspect of this study has been not only the content, but also the context in which the study was conducted. It was conducted in a health gallery, which, in part, sought to bring a discussion of gender diversity into conversation with classification systems and biomedical discourses of health. ‘Gender’ and ‘sex’ are often used interchangeably in healthcare settings, with the gender denoted on medical records permitting healthcare staff to make inferences about a patient’s anatomy and physiology (see for instance: Shepherd & Hanckel, Citation2021).

The use of this categorization across varied aspects of dimensions of life comes out in the presentations of gender by young people, who are, in the space of the exhibition, putting forward ways to make sense of gender. Indeed it is notable that they are thinking of gender and making sense of it as a category, as personal, biological, as socio-biological, as essence, as physical body, and as social construction, which has implications for individuals but also health practices in everyday contexts. Thinking about how we might listen to and make sense of this gallery space located with(in) medical institutions with young people, we need to reconsider the usage of gender in health settings to legitimize gender possibilities as well as health possibilities. The question that should perhaps be asked is, if it is ever necessary for gender to be used in medical contexts? Operationalising gender as a proxy for anatomy and physiology is a fallacy because it presumes that bodies are static – when really, they are altered all the time whether it be due to malignancy, disease, infection, contraception, gender dysphoria, as well as cosmetic surgery. A patient centred approach to clinical care would be to consider the patient’s bodily reality rather than using imprecise and precarious surrogate markers.

Concluding comments

This study surfaces an emerging and ongoing discussion amongst young people in relation to gender, and the ways that gender logics are made sense of within everyday settings. We note that the study was limited by location in that it took place in one art/science gallery in a major urban centre in a western location. Future studies would benefit from replicating the study in galleries elsewhere to see if similar themes emerge, and the ways that gender operates at individual, interactional, and institutional levels. However, that being said, the study locates a critical dialogue that young people are involved in and living everyday in relation to gender, which is being made sense of as new ways of thinking and categorizing gendered lives emerge. It is critical we identify ways to best capture these ongoing discussions, as young people participate in and reimagine these futures together.

Acknowledgments

Thank-you to the Science Gallery London for allowing us to participate, and thank-you to Marcia Mihotich for designing the postcards for display and use in the gallery space.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Benjamin Hanckel

Dr Benjamin Hanckel is a sociologist at the Institute for Culture and Society and Young and Resilient Research Centre at Western Sydney University, Australia. Benjamin’s work examines health and wellbeing, social inequalities in health, and social change. His work includes projects on youth wellbeing, genders and sexualities research, as well as work examining digital technologies and health. He is co-editor of Journal of Applied Youth Studies, and associate editor of Health Sociology Review.

Adam Shepherd

Adam Shepherd completed his Master of Public Health at King’s College London and is currently pursuing his medicine degree. His research focuses on trans people’s experiences in healthcare and the discursive construction of gender.

References

- Acker, J. (1992). From sex roles to gendered institutions. Contemporary Sociology, 21(5), 565–569. https://doi.org/10.2307/2075528

- Acord, S. K. (2010). Beyond the head: The practical work of curating contemporary art. Qualitative Sociology, 33(4), 447–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11133-010-9164-y

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv12101zq

- Clarke, A. (2005). Situational Analysis: Grounded Theory After the Postmodern Turn. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Cover, R. (2018). Emergent Identities: New Sexualities, Genders and Relationships in a Digital Era. Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315104348

- Deutsch, F. M. (2007). Undoing Gender. Gender & Society, 21(1), 106–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243206293577

- Franklin, A., & Papastergiadis, N. (2017). Engaging with the anti-museum? Visitors to the museum of old and new art. Journal of Sociology, 53(3), 670–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783317712866

- Greenberg, R., Ferguson, B. W., & Nairne, S. (1996). Thinking about exhibitions. Routledge.

- Hanckel, B., Vivienne, S., Byron, P., Robards, B., & Churchill, B. (2019). ‘That’s not necessarily for them’: LGBTIQ+ young people, social media platform affordances and identity curation. Media, Culture & Society, 41(8), 1261–1278. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719846612

- Heyam, K. (2022). Before we were trans: A new history of gender. Seal Press.

- Lim, J., & Browne, K. (2009). Senses of Gender. Sociological Research Online, 14(1), 75–88. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1859

- Mehta, N. (2011). Mind-body Dualism: A critique from a health perspective. Mens Sana Monographs, 9(1), 202–209. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1229.77436

- Playdon, Z. (2021). The Hidden Case of Ewan Forbes. Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Puwar, N., & Sharma, S. (2012). Curating Sociology. The Sociological Review, 60(1_suppl), 40–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02116.x

- Risman, B. J. (2004). Gender as a social structure: Theory wrestling with activism. Gender & Society, 18(4), 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243204265349

- Risman, B. J. (2009). From doing to undoing: Gender as we know it. Gender & Society, 23(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243208326874

- Risman, B. J. (2018). Where the millennials will take us: A new generation wrestles with the gender structure. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199324385.001.0001

- Risman, B. J., & Davis, G. (2013). From sex roles to gender structure. Current Sociology, 61(5–6), 733–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113479315

- Robards, B., Churchill, B., Vivienne, S., Hanckel, B., & Byron, P. (2018). Twenty years of “cyberqueer”: The enduring significance of the internet for young LGBTIQ+ people. In P. Aggleton, R. Cover, D. Leahy, D. Marshall, & M. L. Rasmussen (Eds.), Youth, sexuality and sexual citizenship (pp. 151–167). Routledge.

- Russell, S. T., Clarke, T. J., & Clary, J. (2009). Are Teens “Post gay”? Contemporary adolescents’ sexual identity labels. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 38(7), 884–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-008-9388-2

- Science Gallery Website, (2022) Date Accessed: 12th April. 2022, https://london.sciencegallery.com/about

- Shepherd, A., & Hanckel, B. (2021). Ontologies of transition(s) in healthcare practice: Examining the lived experiences and representations of transgender adults transitioning in healthcare. Health Sociology Review, 30(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2020.1854618

- Vivienne, S., Hanckel, B., Byron, P., Robards, B., & Churchill, B. (2021). The social life of data: Strategies for categorizing fluid and multiple genders. Journal of Gender Studies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2021.2000852

- West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing Gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243287001002002

- West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (2009). Accounting for doing gender. Gender & Society, 23(1), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243208326529