ABSTRACT

A violent extremist group poses a significant threat to parts of Cabo Delgado province. Since its first major attack in October 2017, it has perpetuated a conflict to the detriment of sections of the population and government, as well as disrupting economic development. Little is known about the group and there is a considerable amount of confusion in policymaking and academic circles about the nature of the violent extremists (VE) and their relationship to the wider global Salafi-Jihadi community. By analysing the theological underpinnings of VE and their action in Cabo Delgado (CD), we bring clarity to this debate to enable international actors and policymakers in Mozambique navigate the complexities of the situation. From this analysis we conclude the following: VE are not Salafi-Jihadis as they do not share their ideological and theological understanding of the world. It is more accurate to present VE as challengers to the established order. Their struggle is best understood as a challenge to authorities to secure increased political and religious representation, and socio-economic benefits in CD.

A Salafi-Jihadi insurgency in Cabo Delgado?

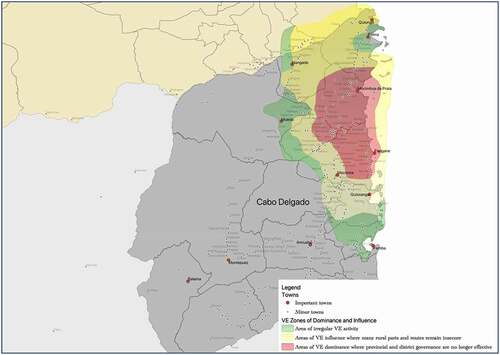

On 5 October 2107, violent extremistsFootnote1 made an explosive appearance on the world stage by launching a high-profile inghimasFootnote2-style attack against government installations in the coastal town of Mocimboa da Praia (MDP). Since then, VE have been waging an ever-expanding, malignant insurgency against representations of national and state governance, the military and security forces of the Mozambican state (FDS), as well as perceived agents and sympathisers of the state. VE have successfully established themselves in parts of CD, dominating significant areas of the province (see map), and have challenged the security primacy of the FDS in the region. More importantly, they have shown themselves to be resilient, adaptable, and capable of rapid expansion – within specific geographical boundaries- by tapping into widespread disenfranchisement with the central government, among the local youth.Footnote3 VE have created a simple, enticing narrative for many young men in CD, by expertly playing on socio-economic deprivations, ethnic resentment, and generational clashes, presenting these complex issues as the product of ‘degenerate’ and un-Islamic governance. Their resiliency and capacity for rapid expansion can also be explained by the low opportunity cost of engaging in violence, combined with the enticements of financial reward and spoils of conflict. The political, economic, religious, ethnic, and geographical isolation of CD vis-à-vis the rest of the country has created ideal circumstances for the flourishing of an insurgency.

Although VE have undoubtedly been successful in dominating certain territory in the last few years, key questions about the nature of the movement, its ideology, and its potential links to global Salafi-Jihadism – in particular Islamic State (IS) – remain. The first part of this article will address some of these ambiguities by first proposing a definition of Salafi-Jihadism, before exploring the theological underpinnings of the VE movement and analysing its strategic decisions so far. Building on this research, this article proposes a radical paradigm shift and argues that the VE group is not a Salafi-Jihadi movement, and not currently connected in any impactful way to IS. Though they undoubtedly started as a Salafi group, they have, since militarisation, largely abandoned the trappings of Salafi-Jihadism, resorting instead to vague demands for increased political and religious representation within established structures.

What is Salafi-Jihadism?

Common understandings of Salafi-Jihadism has been anchored on tradition more than definition. Many argue that Islamist movements are, by their very nature, Salafi-Jihadis.Footnote4 This is hardly a working definition because it encompasses a variety of movements with radically different aims, ideologies, religious traditions, and methods.

In recent years, academics have started to rigorously study Islamic theology and history to construct and articulate a better understanding of the concept. As a result, a consensus has emerged among scholars of four core tenets which define Salafi-Jihadism: tawhid (unitary oneness of God), hakimiyya (the rule of God – both religiously and politically), al-wala wa-l-bara (loyalty and disavowal for the sake of God), takfir (excommunication), and jihad (struggle, in the context of religious war).Footnote5 All these factors are equally important to the definition and all need to be exhibited in some way for a movement to be identified as part of the Salafi-Jihadi nebula.

Tawhid

Tawhid is a central tenet of Salafi-Jihadism because it is focused on the preservation of the purity of the faith.Footnote6 For Salafi-Jihadis, there can be no compromise with the authority of God. If one desires to be a good Muslim, one has to live fully in the path of God. Such a concept makes Islam a living ideal where faith and action cannot be divorced. Proclamation of faith is not enough, one must act and devote one’s very life, body and soul, to the creation of an Islamic world.Footnote7 As such, Salafi-Jihadis oppose secular forms of governance, the pursuit of worldly pleasures, and the corrupting influence of modernity. It posits a world where the only path to salvation is total devotion to the Salafi ideals. Tawhid represents a rigid doctrine of political absolutism which is used to discredit the modern world and attack ‘un-Islamic’ forms of governance.Footnote8 This belief in the unitary nature of God leads them to often display the index-finger salute, a reminder of their attachment to tawhid and the omnipresence of God, both universal and absolute, that sanctions their struggle.

Hakimiyya

Hakimiyya is a concept derived from tawhid which posits that the sole acceptable form of governance for Muslims is the rule of God as outlined in the sharia.Footnote9 Not only does it theoretically enable Muslims to live in peace and harmony with God, in a perfect politico-legal framework, both it serves to promote Islam throughout the world.Footnote10 Hakimiyya serves as a propaganda tool for Salafi-Jihadis because they put forward a dichotomy between the rule of God through sharia and the disorder and chaos of secular governance.Footnote11 Salafi-Jihadi groups have gone to great length to discredit secular forms of governance, emphasising the injustices and abuses Muslims have suffered under secular regimes. Against this system of chaos, they offer peace and tranquillity through hakimiyya. Under sharia, there would be no disorder, no brutality, and no oppression as leaders would be guided by God to protect the people and their faith.Footnote12

Jihad

For Salafi-Jihadis, jihad is the second most important pillar of Islam after faith itself. Unlike historical understanding of jihad,Footnote13 which date back to early Islamic history and argue that legitimate authority and proportionality are needed to declare jihad, Salafi-Jihadis believe that it is the duty of every Muslim to fight for their faith.Footnote14 This unorthodox and radical stance is the product of a perceived existential threat to Islam posed by secular governance and modern social norms. In line with the principle of fiqh al-muwazanat, that is the jurisprudence of balance, they argue that, should nothing be done, the umma will perish.Footnote15 Therefore, faced with the prospect of annihilation, all other tenets of Islamic jurisprudence are suspended and unrestricted jihad against kufrs and ‘degenerate’ Muslims is acceptable.Footnote16 This extremist belief has been further reinforced by theological arguments putting forth the idea that jihad is ‘in the path of Allah’ and therefore exists as a concept beyond human agency.Footnote17 As God is the supreme authority and jihad is waged in his name, all legal and theological limits on violence are removed. This gives rise to unrestricted warfare against the non-believers, which is embodied by jihadis following an extremely permissive code of conduct.Footnote18

Al-wala wa-l-bara

Al-wala wa-l-bara, loosely translated to loyalty and disavowal for the sake of God, is central to Salafi-Jihadi ideology as it authorizes violence against non-believers as well as demanding obedience to Salafi-Jihadism from mainstream Muslims.Footnote19 In essence, it instrumentalises Muslim identity as a tool of political control.Footnote20 As such, al-wala wa-l-bara serves to delineate between Muslims, understood within the boundaries of Salafi-Jihadi thinking, and non-Muslims (that is, anyone who opposes them). Furthermore, this theological concept is used as justification for violence as those who belong to Islam are meant to be protected against “outsiders”. Faith, if practiced according to the norms of Salafi-Jihadis, is the sole determinant of belonging to the umma. Al-wala wa-l-bara is also understood by Salafi-Jihadis as a zero-sum game.Footnote21 This implies that damage to the interests of the kufrs and apostates is always a net gain for the umma, and vice versa. This, therefore, creates a Manichaean world view which forces Muslims to either side with the Salafi-Jihadis and defend their faith, or with the infidels and their ungodly ways. Finally, this concept has given legitimacy and authority to Salafi-Jihadis, because it has ‘allowed them to delegitimise their opponents for not having displayed adequate levels of al-wala wa-l-bara, while presenting themselves as the custodians of a pure, unadulterated form of Islam.’Footnote22

Takfir

Takfir is a concept closely connected to al-wala wa-l-bara. It is similar to the principle of excommunication within the Catholic Church. Takfir allows Salafi-Jihadis to cut off Muslims who oppose them from the umma and therefore justify their use of violence against them.Footnote23 It has been used against forms of Islam which Salafi-Jihadis have accused of bid’a (heretical practices) and labelled ‘degenerate’. It has also been used to justify attacks against Muslims who support secular forms of governance. Salafi-Jihadis have argued that, in dar al-Islam,Footnote24 Muslims who support heretical leaders are guilty of ansar al-tawaghit and therefore should be considered as enemies of the faith.Footnote25 This is a powerful tool to facilitate the transition into violent extremism for everyday citizens, who might have moral qualms about killing their neighbours and compatriots, since it effectively makes all the opponents of Salafi-Jihadis into infidels and apostates.Footnote26 Finally, it has served to delegitimise alternative Islamic models of governance which rival Salafi-Jihadi ideology. Abrogated forms of sharia or modernised forms of Islamic governance are decried as bid’a, and, therefore, become legitimate targets.

Who are the violent extremists in Cabo Delgado and what do they want?

The VE are a complex, multifaceted organisation with opaque origins, an obscure ideology, and lack a coherent and steadfast strategic vision. Before we can comprehend its insurgency campaign and the role it might play on a local, national, or global stage, it is crucial to explore in depth the origins, ideology and strategy of the movement.

Origins: from Salafi sect to violent extremism

To understand the nature of the VE over recent years, it is essential to first study the origins of the non-violent movement to understand its original founding principles and development. This is complicated by the relative lack of credible sources on the early days of this non-violent movement. Short of an excellent study by Morier-Genoud, based on preliminary fieldwork, there remains extensive gaps in our understanding of the genesis of the movement, resulting in conflicting theses about its birth.Footnote27 We can, however, reliably confirm a few key events in the development of VE in CD. The movement started as a non-violent Islamist sect, ASWJ, which had gained traction in MDP and Macomia by 2014 (see ). In October 2017, under severe pressures from the government, they militarised and became VE.

ASWJ was anchored in the radicalisation of Muslim intellectuals in Islamic universities in the 1990s.Footnote28 Financed by generous scholarships provided partially by CISLAMOFootnote29 and partially by Islamic NGOs operating in the country, young Muslim intellectuals were sent to study Islamic theology abroad, most notably in Sudan and Saudi Arabia.Footnote30 On their return, many were forced to endure spells of unemployment, while living in precarious conditions due to the poor socio-economic situation in CD.Footnote31 This led a number of them to create groups which clamoured for stricter forms of Islam, to assuage some of the socio-economic problems in CD, most notably in Nangande in the early 1990s and in Balama in 2007.Footnote32 This view of Salafism as a force for change and a tool of social empowerment was consistent with the global development of Salafism in the Third World after the Soviet-Afghan war.Footnote33 By instrumentalising Salafism as mean of liberation, it is likely that these groups contributed to creating a broader dynamic milieu of sects that wished to apply stricter Islam, and from this ASWJ emerged.Footnote34

In 2014, ASWJ first appeared in MDP where it started to denounce the ‘corrupt’ and ‘degenerate’ forms of Islam practised in CD – legitimised and protected by CISLAMO – and clamoured for a purification of religious life by preaching for a return to the Islamic practices of the first three generations of Muslims.Footnote35 By attempting to mirror the spiritual life of this idealised ‘golden age’ of Islam, the newly emerging sect aimed to revitalise the faith through authenticity and purity. Initially, violence was not part of their modus operandi.

From 2014 to 2017, ASWJ was seemingly content with living in isolation from mainstream society, focusing on building parallel institutions and insulating their community from the ‘poison’ of secular governance and ‘degenerate’ Sufi Islam.Footnote36 The group had a formalised presence in MDP and Macomia, with permanent mosques and madrassas, as early as 2014, expanding informally to other districts, most notably Ancuabe, Montepuez, and Quissanga from 2016 onwards.Footnote37 However, their highly atypical religious practices quickly put them in conflict with local religious authorities in CD.Footnote38 This conflict was further exacerbated by the virulent denunciations by ASWJ followers of the alleged self-serving, corrupt and bid’a (heretical) practices of the Sufi orders, the mainstream version of Islam in CD. The youthful leadership of the group was, in effect, accusing established religious elites of propagating a heretical form of Islam for their own financial benefit, taking particular offence at the common practice of charging the faithful to conduct religious rites.Footnote39 Moreover, they accused Sufi clerics of pandering to Frelimo elites at the expense of their religious duty to preserve the purity of the faith and work for the common good of the umma.Footnote40 They also launched aggressive recruitment campaigns in several mosques across the province, focusing on Macomia, Quissanga, Palma, and MDP.Footnote41 After the eviction fiasco in Montepuez, where artisanal miners and illicit traders were forcibly removed from the area by the FDS in order to facilitate legitimate ruby mining, the group also sought to recruit from the district by tapping into local grievances, as well as accessing firearms which were available through illicit trade.Footnote42 This recruitment campaign further compounded the friction between the established religious authorities and ASWJ. Followers were banned from mainstream mosques and religious authorities started to appeal to the central government to crack down on the dissident group.

Concurrently, ASWJ also sought to undermine the legitimacy of the government by highlighting their disregard for Islamic law and customs. In November 2015, ASWJ followers attempted to ban the sale of alcohol in Pangane, arguing that it was against sharia. They intimidated and attacked several local businessmen, who called on the authorities to restore order. A riot ensued in which a policeman was killed, and two militants injured.Footnote43 In November 2016, sect members provoked clashes between ASWJ members and mainstream Muslims in Ancuabe which prompted the authorities to arrest 21 followers.Footnote44 The ASWJ mosque in the area was also destroyed. In response to the crack down, militants besieged the police station and demanded the release of their comrades.

In November 2016, at their conference in Nampula, CISLAMO denounced ASWJ, criticising their unorthodox religious practices and accusing them of challenging the primacy of the state in matters of education and governance. CISLAMO was particularly appalled by the refusal of ASWJ followers to have their children educated in state institutions and their rejection of secular law when it came to matrimonial concerns.Footnote45 This led authorities to repress the sect, sometimes violently. In Montepuez, Balama, Ancuabe and Chiure, the group was expelled by authorities in 2016 and their mosques and madrassas were demolished.Footnote46 In Macomia and MDP, authorities proved reluctant to act so decisively. In Macomia, though arrests were made, the culprits were released after sympathetic individuals lobbied the provincial government in Pemba. In MDP, the authorities did not crack down on the group as several local government officials and traders had personal ties to its leadership and were reliant on its activities to survive, living partly on food handouts from ASWJ followers to supplement their meagre salaries.Footnote47 Regardless of the reason for this perceived leniency, the sect continued to flourish until their attack on 5 October 2017.

The reason for a switch of strategy, from a counter-society approach to armed insurgency, remains unclear. A variety of factors appear to have motivated this change.

Firstly, ASWJ seemingly adopted violent extremism as a response to government repression and mismanagement. Following their expulsion from several districts and the arrest of dozens of followers, it had become obvious that the authorities, be they religious or governmental, would not let the sect cut itself off and live in a counter-society based on their radical Salafi ideology. Though the MDP branch had been spared the fate of other branches, ASWJ’s leadership must have been wary of imminent suppression. As such, militarisation was not only an ideological choice, but a matter of organisational survival based on sound strategic thinking.

Secondly, the sect might have been buoyed by an influx of new members coming from Montepuez, primarily recruited from the expropriated artisanal miners and illicit traders. These men, with little to no opportunities and seriously aggrieved by their expropriation were ideal recruits for the group since their opportunity cost for engaging in violent extremism was very low. They also had extensive connections to illicit trade networks, as many of them had worked as low-level facilitators in the shadow economy. These links proved useful to finance militarisation, and the escalation into VE.

Thirdly, militarisation became an obvious choice because the group’s finances were strong and their support among certain sections of the population of MDP was high. In late 2017, the group had secured steady sources of income, most likely through organised crime via interaction with informal traders who had extensive links to business cabals in CD. These business elites were, in all likelihood, interested in using the capabilities of the armed group to facilitate their own economic aims. After 3 years of recruitment, radicalisation and expansion, coupled with the government’s ham-fisted repression campaign, the leadership must have felt that the moment was ripe to escalate their challenge to the established order into violent extremism.

The picture that emerges from the origins of ASWJ, from small Salafi-quietist group to a movement with local support ready to engage in violent extremism, is one of the rational decision-making influenced by a loosely defined Salafi ideology, which serves as a basis for the group’s local socio-political aims.

Violent extremism and ideology

VE ideology is an intricate mix of intra-religious, socio-economic and ethnic grievances. Mixing religious discourse and marginalisation, they have created a powerful narrative of dissent which resonates with many in CD. Their ideology, however, is neither sophisticated nor communicated in a systematic way. Unlike Salafi extremists, who have gone to great lengths to rationalise and publicise their views, VE have remained remarkably discrete about their ideological foundations. They have also struggled to spread their message consistently and in a sophisticated manner, their highly limited propaganda being subpar compared to IS, Al-Shabaab, or Boko Haram.

Since VE have struggled to articulate a coherent ideology or systematically spread their views, we have based our analysis of their movement on what we can observe as fact. Our analysis of VE ideology is based on the structural factors that pushed them to embrace violent extremism and an analysis of their use of violence within the context of the insurgency.

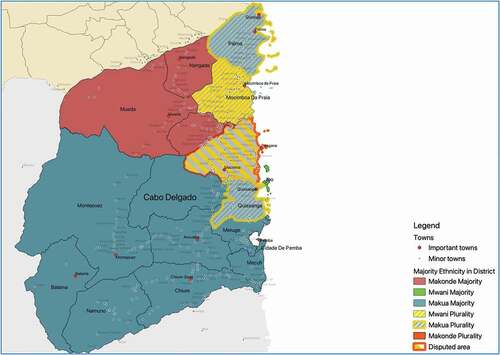

The structural causes of the insurgency in CD are to be found in the marginalisation of Muslims, primarily from the Mwani ethnic group, who felt that they had no means of increasing their participation in local decision-making processes, particularly those relating to the benefits of significant natural resources.

Religious inclusion and governance

From the onset of the group as a radical scripturalist sect, the VE leadership have indicated their desire for the return to a ‘purer’ and idealised version of Islam. They were prevented from doing so by the authorities who decided to repress the group. Prevented from living their faith as they saw fit, ASWJ militants turned to violent extremism to contest their powerlessness and increase their ability to participate in governance. Although the desire to live in a society based on stringent interpretation of Islam has been somewhat side-lined within VE ideology, partly due to strategic concerns and partly due to the success of the insurgency,Footnote48 it remains a constant feature of VE propaganda.Footnote49 It is important to note that there is nothing fundamentally violent or exceptional about this desire.Footnote50 Although the conflict is framed in religious discourse, it is not a religious conflict per se. VE have been fighting against the authorities, both religious and political, to secure channels for political participation which would enable them to live in accordance with their religious principles while benefitting from economic opportunities in the territories that they influence.

Ethnic grievances and governance

VE have also sought to present themselves as the defenders of Mwani people in CD (see ). Once more, this highlights their struggle for political inclusion within the framework of governance in CD. This desire for political inclusion has been a long-standing grievance and is deeply intertwined with both the history of CD and the history of the Mwani people in the region.

Before the full implementation of Portuguese colonisation in Mozambique, which commenced following the Berlin Conference of 1885, the Mwani were the dominant ethnic group of the northern coast of Mozambique.Footnote51 They were prosperous traders and controlled the political landscape of the region. With the Portuguese occupation, the Mwani elites lost their position of influence which prompted a severe political and social crisis as their well-established patronage networks were dismantled.Footnote52 Authority passed to Portuguese colonial authorities who viewed Islam as a dangerous anti-colonial force capable of challenging their rule by uniting the masses through faith.Footnote53 Until the start of the independence war in 1964, the Portuguese continued to fear the Mwani people and their faith. During the war, however, Portuguese colonial intelligence started working with Swahili Muslims to counterbalance the influence of Frelimo in CD.Footnote54 They played on their fears of communism, arguing that Frelimo would impose an atheist dictatorship. As a result, a majority of Mwanis supported the Portuguese in their colonial war. Once Frelimo took power in 1975, they were quick to brand them ‘collaborators’ and side-lined the community.Footnote55

Since then, the Mwanis have effectively been excluded from governance and have been marginalised by the authorities. This is further compounded by the government’s partiality for the Makonde, a predominantly Christian ethnic group which inhabits the Mueda plateau, as well as the eponymous Makonde plateau of Tanzania. The Makondes were the key instigators of the War of Independence and have, since then, occupied some of the key posts in Frelimo. They control most of the licit and illicit trading networks in CD, dominate the political life of the province, and enjoy the protection and patronage of Frelimo.Footnote56 Little has changed under President Nyusi, another Makonde, who has overseen the deeply unpopular expropriation campaigns – disproportionately affecting the Mwani – which followed from the arrival of energy and mining multinationals in the province.Footnote57 This socio-economic dominance of the Makonde has frustrated a majority of Mwani-speaking Cabo Delgadans.Footnote58 Abandoned and marginalised by the government, they have become targets of VE propaganda.

VE have sought to portray themselves as the defenders of the marginalised, particularly the Mwani in CD, presenting their struggle as the antidote to political exclusion and economic marginalisation.Footnote59 As Southerners continue to see Northerners as backward irredentists, coupled with the geographical, political and social isolation of CD vis-à-vis the rest of the country, demands for political inclusion and socio-economic integration are widespread.Footnote60 VE believe that increased channels for political participation within the framework of national governance can be obtained through popular violent uprising. Such a project has become central to VE ideology and is even reflected in their self-perception, with the movement often referring to itself as ‘Swahili Sunna’, loosely translated as ‘Swahili Way’.Footnote61 This desire to control their own destiny has not, however, morphed into a rabid form of ethno-nationalism. VE have been careful not to alienate the Makua people and have sought to merge their grievances with those of the Mwani.Footnote62 The VE have created a narrative that promotes violent extremism as a tool of liberation for both ethnicities, using the dominance of the Makonde as a crucible in which to form an alliance of convenience between disenfranchised groups.Footnote63 This desire for increased political participation is reflected in the propaganda of the movement, with repeated calls to expel the ‘Maputo invaders’ and to fight the government that ‘humiliates the poor’.Footnote64 The push to liberate the people of CD from the perceived tyranny of the regime in Maputo is, therefore, as central to VE ideology as is their desire for the implementation of a more stringent form of Islam in CD.

Lack of sophistication and communication

VE have developed an ideology that is anchored in two interrelated objectives: the possibility of living their faith in accordance with stricter forms of Islam and their desire for increased political participation and socio-economic benefit for marginalised groups. Their ideology, however, is far from sophisticated or communicated in a systematic way.

Since the movement’s inception, its ideology has been remarkably unsophisticated. Unlike Salafi insurgencies, they have not published pamphlets outlining their ideology and the rationale for their actions. It appears that the bulk of their understanding of Salafism, which they exhibited in their counter-society phase, was based on the teachings of Sheikh Aboud Rogo Mohammed, a deceased Kenyan Salafi propagandist who made a name for himself preaching in Swahili.Footnote65 As ASWJ militants were, for the most part, incapable of reading Arabic, they were cut off from much of the intellectual Salafi circles which operate in the Middle East and North Africa. Therefore, their messaging appeared crude in comparison as it is based on limited source material, primarily Arabic texts translated into Swahili by Aboud Rogo Mohammed. Since then, based on testimonies gathered among locals who were captured by the group, VE indoctrination appears to have continued down that rather rudimentary path, with militants handing out recordings of Aboud Rogo Mohammed’s sermons to potential recruits and captives.Footnote66 VE have also sought to recruit and indoctrinate new recruits by linking perceived local injustices to a lack of Islamic governance.Footnote67 This is mainly done by communal readings of the Quran followed by discussion among captives, recruits, and VE.Footnote68

The propaganda produced by VE is also extremely crude. The bulk of their communication has been in the form of poorly filmed videos, often without any audio and shot on mobile phones. The group has also released pictures of their loot and victims after successful operations. Dissemination, however, has been limited to encrypted social media channels with minimal followers. In a few rare cases, pictures and announcements by the group have made their way onto IS-affiliated news outlets. As we shall explore later, this is not evidence of significant links between the two movements but appears to be the work of a single individual with links to the global Salafi-Jihadi sphere.

Strategy and modus operandi

Since the attack on MDP town in October 2017, VE have adopted violent extremism to achieve their aims of increased political participation and socio-economic benefit for Muslims and marginalised groups in CD. In this conflict, VE have proven remarkably resilient and capable of evolution. To build a comprehensive picture of their strategic outlook, we explore VE’s target sets, their recruitment and indoctrination practices, their sources of financing, and their relationship to the Salafi-Jihadi global nebula. To do so, we will highlight important patterns that emerged from data collected since the beginning of the insurgency, using an extensive and unrivalled database, with over 1200 incidents, each with casualty figures, location, date, incident types, and operational details.

Target sets

Since the start of the insurgency, VE have overwhelmingly targeted the authorities and those who actively support them. Authority figures such as religious elders, village elders, local administrators, public officials, policemen and politicians have all been associated with the government and have been perceived as sympathisers. Furthermore, Sufi elders and CISLAMO-affiliated preachers, whom VE consider impious and in league with the government, have also been marked as legitimate targets.

So far, the FDS has been the most explicit target of VE. This situation emerged out of the VE’s desire to rid areas of governance structures and create an atmosphere of terror in which they could step in and replace the government. In an attempt to thwart those plans, the FDS was tasked with protecting what remained of local official governance structures. As such, they have become the primary targets because they are often the last manifest representation of state authority in embattled areas. In their propaganda, VE have gone to great lengths to demonise the military and security forces, arguing that they are an invading force who have inflicted misery and suffering on the people of CD:

We have to fight these leeches and corrupt people who are uniformed everywhere and specifically here in our land. We will get our revenge because it is Allah’s will and we are sons of this land and we know our land and our forests well. Those who will come, will come from Maputo to kill us. They will need guides to approach. If that happens, we will hunt everything that breathes, and nothing will be left behind.Footnote69

The uncompromising nature of VE’s struggle against the armed forces is further evidenced by their reference to the FDS as ‘pigs’, ‘Crusaders’, and ‘cowards’.Footnote70 They have also gone to great lengths to discredit the FDS’s counterinsurgency campaign, denouncing its brutality:

And this is especially so as it is of the policy of this cowardly army that after it receives a damaging defeat at the hands of the soldiers of the Caliphate, it increases its hostility against the peoples in the area in which it is defeated, hoping in that to recover a claimed prestige it tries to impose on the oppressed through tyranny and terror.Footnote71

All of this is consistent with research conducted by other academics who have studied the recruitment patterns of VE and have argued that over 70% of recruits joined the movement in response to the brutality of the FDS.Footnote72

The primacy of the FDS within VE target sets is also corroborated by our own quantitative research. Since 2017, the movement initiated more than 200 attacks on the FDS, with half of those being ambushes, around 90 being prepared offensives against the FDS positions, and 11 of those ‘spectaculars’ in which VE attempted to capture an important town defended by a garrison. Our best estimates indicate that, in those attacks initiated by VE, over 450 FDS servicemen lost their lives (with many more injured). More than half of the casualties inflicted were in prepared offensives against FDS positions. Upwards of 140 FDS casualties were inflicted during the 11 ‘spectaculars’, with over 100 fatalities coming in three operations in or around MDP towns in March, June, and August 2020. The majority of incidents initiated by VE which resulted in FDS casualties were in areas under their domination, namely Macomia and MDP, in which FDS troops were often isolated and surrounded by a hostile population. At the tactical level, they have targeted isolated FDS units operating among an often-hostile Mwani-majority populations. At the strategic level, VE have been focusing their efforts on areas they can dominate, concentrating on coastal CD, mainly in Macomia and MDP, where there are significant Mwani communities.Footnote73 This suggests that VE have been carefully selecting targets based on sound tactical and strategic thinking.Footnote74

VE have also been targeting the civilian authorities and those accused of supporting them. In those attacks, they have, so far, refrained from indiscriminate violence against ‘neutral’ civilians. Although the majority of attacks initiated by VE have been against undefended town or villages, most of these incidents did not result in casualties. Out of around 600 town/village attacks conducted by VE since October 2017, only about 250 have resulted in confirmed casualties. In those 250 town/village attacks, upwards of 1400 civilians were killed. However, according to our preliminary data, only 62 town/village attacks resulted in more than 5 civilian casualties, with over a third of these in Macomia, an area under heavy VE dominance as a result of their violent campaign in the district. Furthermore, over a third of the fatalities caused by these high-casualty attacks were in Muidumbe, an area heavily populated by Makondes who have been specifically targeted by VE for their close association with the Frelimo regime. From this data, it is clear that VE do not engage in indiscriminate violence against the civilian population. When violence is inflicted on the civilian population, it is either part of a reprisal campaign or to consolidate support by eliminating suspected government collaborators.Footnote75 Though VE can display incredible levels of brutality, with beheadings and mutilations being commonplace, there is absolutely nothing exceptional about such methods in the context of non-state armed groups in Africa.Footnote76 This conclusion is further supported by interviews conducted by other academics which have shown that VE generally target only those civilians who have actively supported the government, for example those involved in local governance or people who have ‘betrayed’ the movement.Footnote77 It is clear indeed that VE use both violence and atrocities for strategic effect. When town/village attacks result in mass casualties among the civilian population, this is generally the result of collateral damage in a ‘spectacular’ attack on a FDS strongpoint or targeted killings against ethnic enemies. This was the case with the series of attacks in Muidumbe against Makonde civilians from 2nd to 5th of November 2020 which resulted in over 300 confirmed casualties, some of which can be attributed to the FDS and their air support component provided by the Dyck Advisory Group. Extreme violence, however, is not always a rational choice borne out of a strategic policy.Footnote78 Some of the massacres that have taken place can only be explained by an irrational desire for violence among certain sections of the public. Such unrestrained violence is often the result of brutalisation and a general absence of respect for human rights and the rule of law that exists in societies which have experienced warfare, misery, and death on a grand scale.Footnote79

As of February 2021, VE have always refrained from attacking international assets in CD. Although disinformation has been running rampant about alleged attacks on the installations of extractive or energy multinationals in CD, there has been no evidence of any intention, or coordinated campaign by VE, to target international assets or foreign personnel in the region. Only a handful of incidents have involved employees of multinationals, and these were a consequence of collateral circumstances rather than direct targeting. They do not reflect a broader pattern of targeting international assets by VE. Since the attack on Palma in March 2021, the modus operandi of VE has not changed. Though foreigners were indeed killed during the fighting in the city, they were not directly targeted by VE. The Amarula Lodge, where most foreigners sought refuge, was not attacked, even though VE were in proximity and could have stormed it with absolutely no difficulty. Foreigners were only engaged when their convoy sought to force a VE barrage at the gate of the Lodge. Those who remained inside the compound were not harmed. Though this shows escalation, i.e. the Palma cell now seemingly considers foreigners as acceptable collateral damage, it does not indicate a deliberate targeting of international persons or assets.

Two competing hypotheses have emerged to explain the lack of interest VE have for international assets. On the one hand, some commentators have argued that the insurgents have not targeted international assets as those are heavily defended sites and they do not have the means to attack them yet. On the other hand, competing analysis argues that international assets are of little concern for insurgents because they are not a direct threat to their aims. Moreover, VE have not attacked international assets because they see them as part of their future, in which co-existence would be beneficial for the movement.

The first hypothesis rests on two assumptions. Firstly, they assume that VE are part of a global Salafi-Jihadi nebula which seeks to harm Western interests throughout the globe. We will examine this assumption further at a later point. Secondly, they assume that VE do not have the capability to attack these assets with any success. This is a serious misunderstanding of the tactical situation. The main project in the region, the Total Afungi LNG site, is protected by a Joint Task Force (JTF) made up of chosen units within the FDS. Though the JTF has grown exponentially in the last year, the strength of the unit per se is not important as a simple stand-off attack – firing directly at the site – would be enough to halt proceedings. Furthermore, though the site is now heavily defended, it would have been easy for militants before the construction of the defensive fence to attack the site to secure supplies or loot. The fact that they did not pursue such a potentially profitable operation discredits the idea that international assets have been spared because they are hard targets. If VE wanted to shut down the site, they could easily do so, ergo the site is still active because VE want it to be.

A competing hypothesis is anchored in VE ideology, as communicated through their propaganda. VE propaganda has made it clear that they have no interest in targeting the energy sector, declaring in one of their communiques that ‘Our war is not about this gas [referring to the LNG site in Afungi].’Footnote80 Furthermore, their ideology does not preclude them from tolerating, and even profiting from, the presence of multinationals in the region. Even if they were Salafis, provisions can be made for Muslims to work with non-Muslims, thus defying the proscription on working with kufrs (isti’ana bi-l-kufr) within Salafi theology.Footnote81 Isti’ana bi-l-kufr is acceptable if it is the lesser of two evils (akhaff al-dararayn), serves the public good (maslaha al-mursala), and does not conflict with their quest to impose sharia (maqasid al-shari’a).Footnote82 The presence of multinationals in CD does not violate these conditions. VE are at war with the government, not international businesses, therefore, according to the principle of akhaff al-dararayn, the focus will remain on the enemies of stricter Islam (primarily the government and its organs) and not on multinationals, regardless of their reputation within VE. Furthermore, mega-projects could still have a positive impact on the socio-economic development of the province, even though they are unpopular with some among the local population, and thus the criteria of maslaha al-mursala can be fulfilled. Finally, international assets do not, in principle, conflict with the desire of VE to live within a more stringent interpretation of Islam based on literal application of sharia. The development of international projects by foreign multinationals can be done in accordance with maqasid al-shari’a as is explored later in this article. Overall, international assets have not been targeted by VE as they pose no direct threat to their current aims. However, should this change, either through continued and substantial direct association between mega-projects and the government – particularly if it is perceived that the association is supporting counterinsurgency efforts – international assets might be targeted.

Recruitment and indoctrination

VE have used a variety of means to recruit and indoctrinate young people to join their movement. Though ideology plays a part, the primary drivers of recruitment are socio-economic hardships, the pervasive marginalisation of youth from Mwani communities, and a generational clash between young people in CD and established religious authorities.

Ideology has played, in comparison, a minor role in VE recruitment strategy. This can be explained by two compounding factors. Firstly, complex arguments about theology and ideology are not ideal recruitment tools as they necessitate both cognitive and behavioural radicalisation of potential recruits.Footnote83 Cognitive radicalisation, that is the acceptance of extremist beliefs, is not a guarantee of behavioural radicalisation, that is the embracing of extremist behaviour.Footnote84 Many young men might be receptive to the ideology of the VE, but unless they are ready to actively join the movement and engage in violent extremism, they are no threat to the authorities. The step into violent extremism is, for most people, a difficult one to take as they have everything to lose. As such, ideology can only go so far in providing recruits for the movement. Personal gain, individual grievances, and the low opportunity cost of engaging in violence are far more potent recruitment tools as they provide tangible reasons to engage in violent extremism.Footnote85 Secondly, VE have struggled to spread their ideology in an engaging and sophisticated way. As has previously been discussed, VE propaganda is rather rudimentary. As these are either in physical formats such as tapes and recordings, or on restricted social media channels, the ability of VE to reach a wide audience is limited.

VE have been extremely successful at instrumentalising socio-economic hardships to recruit in Nampula, and Niassa. Due to a lack of opportunities, a significant proportion of young men in the province are stuck in a state of perpetual adolescence. They cannot get an education due to a lack of resources; they cannot start a business due to the lack of capital, and they cannot even get married because they lack the funds to pay bride money. For many young men, the lure of riches is enough to entice them into joining the VE. The movement is known to offer steady wages, in stark contrast to the majority of jobs in CD. This has driven many young men from Nampula and Niassa, who originally came to CD to work in fishing, to join the movement as the wages offered were simply much better than anything in the licit economy.Footnote86 They have also provided interest-free loans to young men to start their own businesses or get married.Footnote87 In exchange, they simply demand loyalty. For many, this is the opportunity of a lifetime. They would never be able to secure the sums needed to integrate themselves into the licit (or illicit) economy through conventional means and thus, the loan is a way to drag themselves out of poverty.Footnote88 The promise of education is also commonplace. VE have sent several recruits to be educated in universities in Sudan and Saudi Arabia, providing them with generous scholarships.

VE have also been playing on generational divides to recruit among the youth. For many young people in CD, the future looks bleak, and the older generations have failed to provide answers to the problems plaguing the province. Lack of opportunities, poor governance, and structural inequalities have all been blamed on the ineptitude of established elites. From its inception, VE have been attempting to tap into this generational clash, presenting the established authorities as being out of touch with the youth and showcasing their movement as a young, innovative, and radical answer to the problems of the day.Footnote89 For many disenfranchised young men, often those who have failed to establish themselves, this radical discourse of social justice framed in a novel way is an appealing proposition, and offers them the opportunity to ‘do something’ with their life and better themselves and their community.Footnote90

Furthermore, the Mwani and Makua youth in CD, have felt especially marginalised in recent years, a feeling VE have been using to recruit extensively in those demographic groups. This feeling of marginalisation, which dates back to the end of colonial rule, has been exacerbated by the recent influx of successful Makonde businessmen into traditionally Mwani and Makua areas. As previously mentioned, Makonde elites have profited immensely from government programmes that foster economic development in CD. They have been granted lucrative mining concessions and prestigious administrative posts at the expense of other ethnicities in CD.Footnote91 Their newly acquired wealth and status, which they have allegedly used to humiliate locals, have been seen as an egregious example of Frelimo’s partiality to the Makonde and have further poisoned community relations in CD.Footnote92 This has proven to be fertile ground for VE recruitment.

VE have also benefitted generally from the low opportunity cost of engaging in violence and anti-social behaviour for the majority of young men in CD. As most recruits are unemployed, uneducated, and single, they have little to lose, and potentially a lot to gain, by joining the insurgency. The prestige that also comes with carrying a firearm is not to be underestimated. For young men with nothing, a firearm is a symbol of power and prestige, which serves to assuage their misgivings about their social standing and gives them ‘control’ over their environment. Acts of extreme violence are therefore a way to increase self-worth and pride while imposing dominance on individuals who are perceived to be benefactors of the system.Footnote93

Financing and the illicit economy

VE have used a variety of means to finance their operation since the start of the insurgency in 2017. Revenues from the licit and illicit economy and donations have provided the majority of the funds.

Before the movement militarised and embraced violent extremism, the majority of income came from the proceeds of legitimate small businesses which their leaders and influencers controlled.Footnote94 The proceeds from these companies were then used to offer loans or scholarships to potential recruits and build mosques and madrassas. Since the start of the insurgency, however, these businesses have been closed by the authorities. Nonetheless, the VE continue to finance themselves through the licit economy by relying on supporters who own small shops and provide a portion of their income to the movement. Some of these businesses are indebted to VE as they were set up using loans provided by the movement. The movement has also charged protection money to legitimate businesses to finance their operation, most notably in Nampula, where businessmen have allegedly been working with VE to protect their trading operations.Footnote95

VE also have links to the illicit economy, charging facilitation money to different smuggling networks to transit through the territory they dominate. They have also reportedly financed their operation through human trafficking by helping Somali migrants in their journey to South Africa,Footnote96 or by engaging in sexual human trafficking by selling young women they hold captives in Tanzania.Footnote97 VE have also financed their operations by receiving a portion of the income of illicit networks that were set up using their loans. As the cost of entering the lucrative illicit economy in CD is prohibitive for the majority of the population, many young men took interest-free loans from VE to set up their informal trading networks. In return, they contribute financially to the movement. It is important to highlight that this was not a concerted effort by VE to overtake illicit networks but a by-product of the indistinguishable nature of the licit and illicit economy in CD.Footnote98

VE have also been financed by private donations from supporters. These donations transit from a variety of Mozambican bank accounts before being sent abroad, first to Somalia, then to Dubai, and finally to Sudan, using mobile applications. Once the money is in Khartoum, it is used to pay wages to fighters, provide more loans to locals in a bid to recruit them, finance scholarships for potential recruits, and buy weapons and supplies.Footnote99

The influence of the illicit economy in VE financing cannot be understated and it is important to understand the profound implications of this reliance on criminal proceeds. Over time, it is likely that VE might become more and more ‘commercially’ interested and less ideological.Footnote100 Proceeds from the illicit economy will drive new recruits to the movement, thus further marginalising the ideologues: ‘Comrades who share a cause can quickly become clients whose demands need to be met.’Footnote101

International links and external influences

So far, there has been little to no evidence of substantial links between VE and the wider global Salafi-Jihadi community. Though plenty of alarmist reports have emerged following the news that IS had claimed the establishment of a province in Central Africa (ISCAP), the reality is that IS has no command-and-control ability over the insurgency, has not shared technical or tactical knowhow, and cannot provide training or weapons to VE.Footnote102 Claims of influential links to other groups, such as Al-Shabaab in Somalia or the Allied Democratic Forces in the DRC are also unproven and fanciful given the limitations of geography and communications.Footnote103 Most of these alarmist reports are based on a fundamental misunderstanding of baya, that is a declaration of allegiance, and a simple declaration of support to prevent fitna, which means the introduction of sedition within the Salafi camp.Footnote104 In essence, though groups might loathe each other, it is still customary to offer words of sympathy and exchange offers of support, all of which do not imply that a formal relationship between the groups exists.Footnote105 Furthermore, baya does not necessarily provide tangible benefits for the group pledging allegiance.Footnote106 IS has been more than happy to accept baya from a variety of actors only to strengthen their image and increase their Wilayah, Islamic provinces, without sending help or technical knowhow to the groups involved, as is the case for Boko Haram.Footnote107

It is also extremely unlikely that such substantial links between IS and VE will ever emerge because, on a fundamental level, the two movements do not share the same ideology or common goals. Unlike IS, VE are, in theory, a scripturalist movement and does not embrace millenarianism. Their concerns are not global but limited to CD.Footnote108 Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of members do not speak Arabic and therefore, it would be very difficult for the two movements to even communicate on a substantial level.Footnote109 Finally, the two movements have widely different religious practices. VE have highly unusual religious rites, as previously mentioned, which would prove offensive to Salafi-Jihadi movements.

The two movements, however, do share some propaganda channels and VE communiques have appeared in online publications by the AMAQ news agency, affiliated to IS. It appears, however, that this is the work of a single individual within the VE group, a South African national, who has been communicating with IS propagandists through encrypted social media networks.Footnote110

Finally, there is no evidence that VE have been recruiting extensively internationally. Though Tanzanians, Gambians, Kenyans and Malawians may have joined the movement, with some even ascending to senior roles, the majority of militants are from CD, a fact that has been supported extensively by testimonies from locals who have often recognised militants during their attacks. It also appears unlikely, given VE local aims, that foreign fighters will flock to their banner in the near future – and certainly not from beyond the continent as proclaimed by some commentators, none of whom provide primary evidence in support of this. Though external accelerators, such as violent repression of Islamist movements in the Great Lakes region, might push some foreign nationals to join the insurgency, this has not been the case so far.Footnote111

Violent extremists and Salafi-Jihadism

Are VE part of a Salafi-Jihadi insurgency? The question is important not only to understand the movement, but has profound repercussions for the future of CD, be it for future prosperity and socio-economic development fostered by international investments, or for issues of governance and regional stability.

This analysis, based on the criteria outlined previously, indicates that VE are not a Salafi-Jihadi movement. Though they exhibited, to some extent, a few of the characteristics of Salafism in their earlier iteration as ASWJ, primarily when it came to promotion of the faith (tawhid and hakimiyya), they fall short of the established definition when it comes to the protection of the faith (jihad, al-wala wa-l-bara, takfir). It is crucial to mention that strict adherence to all these principles is the norm among Salafi-Jihadi groups. IS, Boko Haram, Al-Qaeda all fanatically observe these criteria and deviation by cells or individuals is severely punished. Therefore, it is clear that VE are not part of the global Salafi-Jihadi nebula as the principles, if applied at all, are only loosely so.

Tawhid

In their counter-society phase, ASWJ militants sought to live in perfect harmony with the will of God, cutting themselves off from secular society and devoting their lives to religious matters. They shunned secular education, refused to engage with mainstream society, and sought to live like the first three generations of Muslims, echoing some of the interpretations of the principle of tawhid as exhibited by Salafi-Jihadis. However, some of their religious practices were clearly bid’a and are not in line with mainstream Salafi-Jihadi practices. This is crucial as tawhid is not a fluid concept which one can compromise. Salafi-Jihadi movements put it as their most important ideological tenet and deviation from standard practices of worship are severely punished.

Since militarisation, VE have not consistently engaged with the principle of tawhid, short of displaying the famed one-finger salute in propaganda pictures. VE have not demanded the imposition of the rule of God throughout CD but have instead pushed for increased political and religious representation within established frameworks of governance. Though they clearly loathe the authorities and those who support them, VE have been careful not to alienate the general public with rabid Salafi rhetoric. The lack of theological depth in their propaganda is both a symptom and a proof of their reluctance to apply the principle of tawhid consistently. Furthermore, VE have clearly not ‘lived in the path of Allah’ since militarisation. Their already unusual religious practices have been further bastardised and diluted by the influx of large numbers of greed-driven recruits to the movement, who have little to no interest in complex theological matters. The fact that such recruits are welcomed within the organisation is further proof that VE do not apply tawhid consistently.

Hakimmiyya

VE have not exhibited a desire to apply hakimiyya in a coherent or systematic way on the territory they dominate. Though reports have emerged that VE-dominated areas have been subjected to a form of sharia this is most likely due to strategic and political concerns more than a desire to impose stringent forms of Islamic governance on the population.Footnote112 In essence, hakimiyya serves to control the population, by using sharia as a political-legal framework to legitimise their struggle, and as a recruiting tool to undermine government rule, as sharia proposes swift and orderly justice based on religious law as opposed to the disorganised and often corrupt governmental processes. Since VE aspire to present themselves as righteous actors in a liberation struggle against corrupt and tyrannical authorities, hakimiyya serves to support a ‘hearts and minds’ strategy, ensuring that militants do not harm the population and that VE can efficiently manage the considerable territories they have grown to dominate in recent years.

Jihad

VE have been remarkably quiet on the notion of jihad, especially for a movement that has been readily associated with Salafi-Jihadism by so many international commentators. So far, VE have only declared a jihad against the Mozambican government and the armed forces in order to protect Muslims in CD. This is a crucial distinction which differentiates them from Salafi-Jihadi groups who have global ambitions and seek to defend the umma worldwide. Unlike IS and Al-Qaeda, VE have not voiced a hatred of the West or a desire to be part of a global caliphate – or even the creation of a local emirate. They have also refrained from commenting on the perceived persecution of Muslims worldwide. Though threats of retaliation have been made against South Africa when it indicated a willingness to intervene militarily in CD, these were only spread through IS propaganda channels and it is possible that they did not emanate from VE per se. Furthermore, VE do not appear to reject the international order or even aspire to undermine the principle of the nation state. In essence, their aims are more akin to a violent challenge against the Mozambican state for increased political representation and religious liberties. These aims are clearly not irreconcilable with the current international system. Plenty of Muslim-majority territories within Muslim-minority states have sharia-based systems of governance and operate seamlessly within the national framework. Should VE succeed in their insurgency, increased political representation and religious liberties would not fundamentally alter the current paradigm of governance. Based on current analysis, VE likely use jihad as a tool in their struggle against the perceived marginalisation of Muslims in CD by the authorities, not as a tool to fundamentally transform the province, country or world into a global caliphate. As such, as their aims are not millenarian, it is difficult to argue that they are akin to Salafi-Jihadi movements.

Al-wala wa-l-bara

VE have not used al-wala wa-l-bara in their struggle for increased political representation, which differentiates them from the majority of Salafi-Jihadi movements worldwide. Overall, VE have sought to gain the trust and support of those who are neutral in CD and have not displayed extreme violence against them. The fact that the movement has worked to gain the support of neutrals shows they do not apply al-wala wa-l-bara systematically, as it implies that loyalty is not inherent but must be gained. Furthermore, VE have only specifically targeted individuals and communities who have actively supported the government. Unlike IS or Al-Qaeda, they do not, as a general rule, murder innocent civilians or conduct indiscriminate attacks. They have gone so far as to warn civilians before attacks to prevent unnecessary casualties. Therefore, it is clear that VE have not made use of the full potential of al-wala wa-l-bara.

Takfir

VE have used takfir as a tool to discredit some religious authorities and the government but have refrained from applying the concept systematically. Though they have targeted the leadership of the Sufi orders using takfir, they have not extended its use to the general population, which supports them. Non-combatants and unaffiliated persons have not been systematically targeted, and violence has, to a great extent, been limited. In conventional Salafi-Jihadi thinking, those who engage in bid’a practices can legitimately be targeted. VE have not gone to such lengths, though they have committed significant atrocities and have inflicted horrendous violence on communities to create terror. VE, however, have displayed great violence when targeting Muslims whom they accuse of working with the government. Village elders, local officials and even teachers have been targeted by the group for their active participation in the regime, though this does not imply that the killings were solely motivated by takfir. Many of these officials were targeted because they were accused of betraying the group or actively working with the armed forces. Such betrayals cannot go unpunished if the insurgency is to survive. As such, these attacks are more likely motivated by strategic thinking than by takfir.

Challengers of the established order?

Based on these criteria, VE cannot be described as Salafi-Jihadis as they fail to consistently exhibit the criteria required. Though they have occasionally applied Salafi-Jihadi thinking to aspects relating to the promotion of the faith, especially in their counter-society phase, they fall significantly short of deploying the full theological arsenal when it comes to protection of the faith. VE leaders needed to choose among many divergent scriptures and histories from their religion’s past, which are consistent with their specific situation and objectives in CD, in order to portray their aspirations of the present and future. Many of their choices are inconsistent with the Salafi-Jihadism of IS. Conveniently, VE have never referenced the end-of-days prophecy of the final battles against the ‘infidels’ which is associated with achieving the so-called Islamic State. Furthermore, many VE choices display the cultural bias and modern sensibilities that their so-called inspiration and directors (i.e. IS) try so hard to displace (such as financing through organised crime). Therefore, we argue that it is more accurate to present VE as challengers to the established order. Since they do not engage systematically with all the elements of the protection of the faith and lack the millenarian ambitions of Salafi-Jihadi groups, their struggle is best understood as a challenge to authorities to secure increased political and religious representation, and socio-economic benefits in CD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Thomas Heyen-Dubé

Thomas Heyen is a PhD Candidate in History at Mansfield College, The University of Oxford. His research focuses on the impact of the revolutionary ideology on the development of military strategy. He also holds a MA and BA in War Studies from King’s College London.

Richard Rands

Richard Rands is a strategic and policy development advisor with extensive experience throughout Africa and the Middle East. He currently provides analysis on politics, security and economics in sub-Saharan Africa to regional and international public and private sector actors. A former director for a leading risk management consultancy and a regular military officer, Richard has held multiple senior leadership and management appointments over a 35-year career. He is currently the Managing Director of a leading business intelligence consultancy and advises governments on the development of strategies for Africa.

Notes

1. For this study, the term violent extremism is used, which defines the actions of the group not their beliefs and ideologies (e.g. religious extremists or Islamic extremists). The term ‘insurgents’ is used on occasion since the violent extremists display behaviour consistent with an organization seeking to control a population and its resources through the use of irregular military force. The name Ahlu- Sunna Wa’l Jama’ah (ASWJ) is acknowledged as a group that practised stricter Islam in parts of Cabo Delgado prior to the onset of the conflict, but whose members expulsion and arrest was one of the catalysts for subsequent violence.

2. Many Muslim armies have used the belief in fate and divine pre-destination to motivate advancing soldiers, particularly through inghimas attacks (plunging into the enemy) – a charter for bold and brazen assaults.

3. Geographically limited as a result of ethnic boundaries, occasionally successful security operations and land owned by influential elites.

4. Söderberg Kovacs, “Negotiating Sacred Grounds? Resolving Islamist Armed Conflicts,” 378.

5. Maher, Salafi-Jihadism The History Of An Idea, 14.

6. Ibid., 145.

7. Ibid., 149.

8. Ibid., 153.

9. Sharia is an Islamic politico-legal framework which serves to protect individuals and property.

10. Khatab, “Hakimiyyah and Jahiliyyah in the Thought of Sayyid Qutb,” 145–46.

11. Ibid., 154–55.

12. Ibid., 160–61.

13. Jihad is a complex phenomenon which can be broken down in two concepts: greater jihad and lesser jihad. Greater jihad is, in essence, a spiritual struggle against one’s base impulses. This interpretation of jihad is, however, fairly recent and though popular amongst academics, there is a great deal of controversy surrounding its origins and its prevalence in the Muslim world. Lesser jihad has to do with religious war and its use to defend and expand Islam. It serves to sanction violent struggle by codifying the use of violence under the auspices of God. See Cook, Understanding Jihad, 3.

14. Ibid., 130.

15. The umma is understood by Salafi-Jihadis as representing the whole global Muslim community. For Salafi-Jihadis, faith is the sole basis of citizenship and belonging. As such, for them, the primary identity of all Muslims should be defined by Islam, and their relationship to others should be defined by belonging to the umma. See Maher, Salafi-Jihadism The History Of An Idea, 114.

16. Kufrs are infidels, namely non-Muslims who have not accepted the faith.

17. Maher, Salafi-Jihadism The History Of An Idea, 39.

18. Cook, Understanding Jihad, 104.

19. Ibid., 141.

20. Maher, Salafi-Jihadism The History Of An Idea, 112.

21. Ibid., 113.

22. Ibid., 141.

23. Cook, Understanding Jihad, 162.

24. Dar al-Islam is understood to be the ‘land of Islam’ that is Muslim majority areas.

25. Ansar al-tawaghit is a term to label the crime for Muslims of supporting heretical leaders who rule over dar al-Islam. See Maher, Salafi-Jihadism The History Of An Idea, 95.

26. Ibid., 94.

27. See Morier-Genoud and Habibe, Forquilha, Pereira for excellent background information on ASWJ: Morier-Genoud, “The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique”; and Habibe, Forquilha, and Pereira, Islamic Radicalisation in Northern Mozambique.

28. Morier-Genoud, “The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique,” 401.

29. The Islamic Council of Mozambique (CISLAMO), a national body established through support from Frelimo.

30. Villallon, “Between Democracy and Militancy,” 188.

31. Dembele, Mozambique: Islamic insurgency, 9.

32. See note 28 above.

33. Maher, Salafi-Jihadism The History Of An Idea, 125.

34. See note 28 above.

35. Bonate, “Why the Mozambican Government’s Alliance with the Islamic Council of Mozambique Might not end the Insurgency in Cabo Delgado.”

36. Mangena and Pherudi, “Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique,” 351.

37. Ibid., 349.

38. Morier-Genoud, “The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique: Origins, Nature and Beginning,” 399.

39. Bonate, “Transformations de l’islam à Pemba au Mozambique,” 71.

40. Morier-Genoud, “The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique: Origins, Nature and Beginning,” 402.

41. Habibe, Forquilha, and Pereira, Islamic Radicalisation in Northern Mozambique, 12.

42. Mapfumo, “The Nexus Between Violent Extremism and the Illicit Economy in Northern Mozambique,” 105.

43. Morier-Genoud, “The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique,” 404.

44. Ibid., 402.

45. Ibid., 400.

46. Ibid., 403.

47. Habibe, Forquilha, and Pereira, Islamic Radicalisation in Northern Mozambique, 12.

48. There has been a precipitous decrease in Salafi rhetoric among VE in recent years. This is partly due to strategic concerns. As we shall explore later, the first followers of ASWJ were idealists; the current VE recruits are primarily driven by financial gain. Hard Salafi ideology provides insufficient sway – promises of quick cash and opportunities are far more potent. Insurgency success has also been important. VE now dominate sizeable territory and likely make significant profit through illicit trade. It has become difficult to reconcile the wealth and power of the movement with the lofty aspirations of worldly poverty and devotion to God. See following for information on financing and its impact on group stability: Kan, “Defeating the Islamic State: A Financial-Military Strategy,” 73–74.

49. Violent Extremists, Propaganda video: 29/05/2020 (2020).

50. Villallon, “Between Democracy and Militancy: Islam in Africa” 190.

51. Bonate, “The Advent and Schisms of Sufi Orders in Mozambique, 1896–1964.” 486.

52. Ibid.

53. Von Sicard, “Islam in Mozambique,” 478–80.

54. Barnett, “The “Central African” Jihad.”

55. Ibid.

56. Mapfumo, “The Nexus Between Violent Extremism and the Illicit Economy in Northern Mozambique,” 104.

57. Ibid., 104–05.

58. Forster, “Jihadism in Mozambique,” 1.

59. See note 54 above.

60. Mangena and Pherudi, “Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique,” 350.

61. Ibid.

62. See note 54 above.

63. Ibid.

64. Violent Extremists, Propaganda video: 29/03/2020 (2020); Violent Extremists, Propaganda Video: 11/05/2020 (2020).

65. Campbell, “From Separatism to Salafism.”

66. Habibe, Forquilha, and Pereira, Islamic Radicalisation in Northern Mozambique, 28.

67. Feijó, Caracterizacao E Organizacao Social Dos Machababos A Partir Dos Discursos De Mulheres Raptadas, [Characteristics and Organization of the Violent Extremists based on the Testimonies of Abducted Women], 12.

68. Ibid.

69. Violent Extremists, Propaganda Video: 11/05/2020.

70. Ibid.; Islamic State Al-Naba’ newsletter, Violent Extremists’ Communique in IS Newsletter (2020).

71. Islamic State Al-Naba’ newsletter, Violent Extremists’ Communique in IS Newsletter.

72. Mangena and Pherudi, “Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique,” 357.

73. Columbo, “The Secret to the Northern Mozambique Insurgency’s Success.”

74. Ibid.

75. Mangena and Pherudi, “Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique,” 355.

76. Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War, 223.

77. Mangena and Pherudi, “Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique,” 356.

78. Kalyvas, The Logic of Violence in Civil War, 52.

79. Mitton, Rebels in a Rotten State: Understanding Atrocity in the Sierra Leone Civil War, 240–45.

80. See note 69 above.

81. Maher, Salafi-Jihadism The History Of An Idea, 126.

82. Ibid., 129.

83. Habibe, Forquilha, and Pereira, Islamic Radicalisation in Northern Mozambique, 8.

84. Ibid.

85. Vicente and Vilela, Preventing Violent Islamic Radicalization, 2.

86. Hayson, “Where Crime Compounds Conflict,” 17.

87. See note 65 above.

88. Hayson, “Where Crime Compounds Conflict,” 17.

89. Mapfumo, ‘The Nexus Between Violent Extremism and the Illicit Economy in Northern Mozambique, 102.

90. Ibid., 112.

91. Ibid., 104.

92. Habibe, Forquilha, and Pereira, Islamic Radicalisation in Northern Mozambique, 24.

93. Mitton, Rebels in a Rotten State, 177.

94. Hayson, “Where Crime Compounds Conflict,” 17.

95. Ibid., 18.

96. Ibid., 12.

97. Feijó, Caracterizacao E Organizacao Social Dos Machababos A Partir Dos Discursos De Mulheres Raptadas, [Characteristics and Organization of the Violent Extremists based on the Testimonies of Abducted Women], 13.

98. Hayson, “Where Crime Compounds Conflict,” 16.

99. Ibid., 18–19.

100. See note 73 above.

101. Kan, “Defeating the Islamic State,” 74.

102. See note 54 above.

103. Ibid.

104. Milton and al-Ubaydi, “Pledging Bay`a,” 2.

105. Ibid.

106. Ibid., 5.

107. Ibid., 6.

108. Morier-Genoud, ‘The Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique,’ 406.

109. Ibid.

110. See note 54 above.

111. Forster, “Jihadism in Mozambique,” 5.

112. The objectives of sharia priorities the protection of life and belongings, with a focus on those assets that are necessary to life as a priority. It could be argued that sharia is the best form of interim governance for those that remain, given the havoc VE have created among so many communities.

Bibliography

- Barnett, James. 2020. “The “Central African” Jihad: Islamism and Nation-Building in Mozambique and Uganda“. Hudson Institute, October 29.

- Bonate, Liazzat. 2019. “Why the Mozambican Government’s Alliance with the Islamic Council of Mozambique Might Not End the Insurgency in Cabo Delgado“. Zitamar, June 14.

- Bonate, Liazzat J. K. “Transformations De L’islam À Pemba Au Mozambique.” Afrique Contemporaine 231, no. 3 (2009): 61. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/afco.231.0061.

- Bonate, Liazzat J. K. “The Advent and Schisms of Sufi Orders in Mozambique, 1896–1964.” Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations 26, no. 4 (2015): 483–501. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09596410.2015.1080976.

- Campbell, John. 2021. “From Separatism to Salafism: Militancy on the Swahili Coast“. Council on Foreign Relations, January 13. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://www.cfr.org/blog/separatism-salafism-militancy-swahili-coast.

- Columbo, Emilia. 2020. “The Secret to the Northern Mozambique Insurgency’s Success“. War on the Rocks, October 8. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://warontherocks.com/2020/10/the-secret-to-the-northern-mozambique-insurgencys-success/.

- Cook, David. Understanding Jihad. Oakland: University of California Press, 2015.

- Dembele, Yonas. Mozambique: Islamic Insurgency: In-depth Analysis of Ahl Al- Sunnah Wa al-Jama’ah (ASWJ). Santa Ana, CA: World Watch Research: Open Doors International, July 2020.

- Feijó, Joao. Caracterizacao E Organizacao Social Dos Machababos A Partir Dos Discursos De Mulheres Raptadas [Characteristics and Organization of the Violent Extremists based on the Testimonies of Abducted Women]. Maputo: Observatorio de Meio Rural, April 2021.

- Forster, Peter. 2020. “Jihadism in Mozambique: The Enablers of Extremist Sustainability“. Small Wars Journal, October 20. Accessed January 17, 2021.

- Habibe, Saide, Salvador Forquilha, and Joao Pereira. Islamic Radicalisation in Northern Mozambique: The Case of Mocimboa da Praia. Maputo, Mozambique: Cadernos IESE. IESE Scientific Council, 2019.

- Hayson, Simone. 2018. “Where Crime Compounds Conflict: Understanding Northern Mozambique’s Vulnerabilities“. Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, October 25. Accessed January 20, 2021. https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/northern_mozambique_violence/.

- Islamic State Al-Naba’ newsletter. Violent Extremists’ Communique in IS Newsletter. 2020.

- Kalyvas, Stathis N. The Logic of Violence in Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Kan, Paul Rexton. “Defeating the Islamic State: A Financial-Military Strategy.” The US Army War College Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2014): 71–80.

- Khatab, Sayed. “Hakimiyyah and Jahiliyyah in the Thought of Sayyid Qutb.” Middle Eastern Studies 38, no. 3 (2002): 145–170. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/714004475.

- Maher, Shiraz. Salafi-Jihadism The History Of An Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Mangena, Blessed, and Mokete Pherudi. “Disentangling Violent Extremism in Cabo Delgado Province, Northern Mozambique: Challenges and Prospects.” In Extremisms in Africa, edited by Alain Tschudin, Stephen Buchanan-Clarke, Lloyd Coutts, Susan Russell, and Tyala Mandla. Auckland Park, 348–365, South Africa: Tracey Macdonald Publishers, 2019.