ABSTRACT

This article leverages data from an oft-overlooked case of rebel governance – India’s United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) – to demonstrate the importance of de-centring territorial control as a prerequisite for rebel governance. ULFA neither controlled territory nor developed formalised bureaucratic institutions, yet its ‘parallel government’ held considerable sway over Assamese public life during 1985–1990, underpinned by its social embeddedness, influence upon media discourse and crucially its subversion of state structures, until its ability to limit state repression collapsed. The rise and fall of ULFA’s rebel governance illustrates the hybrid socio-political terrain upon which rebel governance is often laid.

Introduction

The rebel governance literature generally holds that ‘territory enables control, and institutions and infrastructure enable governance’.Footnote1 Recent works have challenged this assumption, highlighting that rebel governance may in fact be possible when rebels lack territorial control or formal political institutions. As Worrall notes:

Some rebels may govern by taking and holding territory to create proto-states, others may not have sufficient resources to formally hold territory in such an overt manner and may instead look at temporary or temporal forms of governance, while others still may exert control from a distance, using psychological techniques or surveillance.Footnote2

Moreover, governance may simply take place ‘on the spot’, or may co-opt and rely on hybrid institutional arrangements vis-à-vis the state.Footnote3 However, the field has largely remained skewed towards powerful armed groups that have or are attempting to develop embryonic state structures, to the exclusion of rebel groups exercising minimalist forms of governance not reliant on territorial control.Footnote4

This article introduces a little-known yet fascinating case of rebel governance – that of the United Liberation Front of Assam (ULFA) insurgency in Assam, Northeast India – to underline the importance of de-centring both territorial control and formalised institutions as prerequisites for rebel governance. Widely seen as a disorganised, limited outfit in comparison to the neighbouring Naga insurgency, which has received comparatively more attention in the rebel governance scholarship,Footnote5 ULFA never established any formal territorial control. While some local units established rudimentary ‘people’s courts’ in rural areas, ULFA rebel governance for the most part lacked formalised institutions. Yet during ULFA’s heyday in the late 1980s, ‘the boys’, as they were affectionately known by sympathisers, constructed a ‘parallel government’ that ‘really called the shots’ across large swathes of everyday Assamese political life, at least until 1990.Footnote6 ULFA was known for its aggressive moral policing and ‘people’s courts’, its role in building schools, roads and flood defences and its ‘Robin Hood’-like taxation of Assam’s lucrative tea gardens.Footnote7

How was ULFA able to operate its parallel governance structure? ULFA rebel governance was built around three key dimensions that negated both the need for physical control of territory and the development of formalised institutions. Firstly, the group was socially embedded in key strategic networks, emerging from common membership of the 1979–1985 Assam Movement against migration and the ‘step motherly’ (or exploitative and neglectful) treatment of Assam by the central government.Footnote8 Through this social embeddedness, surrounded by an array of natural allies, the group was able to move freely across large parts of Assam, secure ad hoc coordination when opportunities to do so arose and conduct a combination of on-the-spot, project-oriented and mobile governance activities that did not require a sustained presence based on territorial control. Emerging from this social embeddedness, the second dimension facilitating ULFA rebel governance was its strategic penetration of state structures. The emergence of a tacit understanding between ULFA and their ideological allies in the ruling Asom Gana Parishad (AGP) during 1985–1990 allowed ULFA to nullify police and broader state-level efforts against it. At the local level, this allowed ULFA to operate unchallenged and to coerce and co-opt elements of the state to direct service provision where needed. Again emerging from its social embeddedness, the third dimension concerned its ability to influence the media discourse to amplify the political effects of ULFA activities. This had two simultaneous effects. First, it created what Ashley Jackson terms ‘atmospheric coercion’,Footnote9 a creeping, social-psychological form of influence in which the use or threat of violence created a ‘fear psychosis’ among the group’s opponents and targets.Footnote10 At the same time, however, it allowed news of the group and its activities to reach its broader constituencies, in doing so enhancing its existing social embeddedness. ULFA’s governance activities, in the form of its moral policing, service provision and taxation – at least initially - often involved the coercion of opponents. This simultaneously enhanced ULFA’s ‘Robin Hood’ image among its broader constituencies, which in turn contributed to the group’s rapid recruitment across Assam throughout the late 1980s.

Ultimately however, ULFA’s rebel governance collapsed under the weight of the group’s expansion. Recruitment and training forced excesses in group taxation practices, drawing the ire of the central government and leading to the introduction of central rule in Assam and the accompanying deployment of the Indian Army. This forced ULFA underground, compelling it to retreat from much of its ‘parallel government’ activities. Thus, while ULFA’s rebel governance flourished in the permissive conditions of the 1980s, its rebel governance was vulnerable when these three interlocking factors – in particular its subversion of state structures – were no longer able to create the right conditions.

Drawing on an extensive range of evidence and triangulating interviews, archival data and an array of secondary, ‘grey’, media and government documentation collected before, during and after fieldwork in Delhi and Assam in 2016, the article charts the rise and fall of ULFA’s rebel governance and the centrality of its enabling social and political conditions in Assam. It leverages this data to demonstrate the importance of decoupling the study of rebel governance from the characteristics of ‘stateness’ while also deepening our understanding of the hybrid social and political terrain upon which rebel governance is often laid.

Sifting through secondary, grey and media materials allowed for the identification of patterns in how ULFA’s ‘parallel government’ was conceptualised throughout the 1985–1990 period, but also highlighted gaps and important questions. Interviews with retired security forces members, politicians, administrators, journalists, civil society actors and academics then focused on these areas. Triangulating within and between these data sources thereby generated insights into the scope, depth and rationales of ULFA’s governance activities during the period.Footnote11

The article proceeds as follows. Section one interrogates the widely held assumptions regarding territorial control and political institutions in the rebel governance scholarship, highlighting how these have skewed case selection, with important consequences for the field. It then highlights recent challenges to these assumptions and the importance of exploring cases that do not conform to this pattern. Section two then introduces the ULFA insurgency in Assam and illustrates how the ‘parallel government’ of the 1980s was neither built on territorial control nor formalised administrative or bureaucratic institutions, exploring the reasons behind this. Section three outlines the three central conditions of social embeddedness, state penetration and media penetration upon which ULFA rebel governance rested. Section four illustrates how these dimensions facilitated ULFA’s three core governance activities – service provision, moral policing and taxation – each of which in turn fed back into and reproduced ULFA’s ‘Robin Hood’ aura. Section five then charts the collapse of ULFA’s rebel governance. The pressures of an ever-growing cadre base however pushed ULFA into actions that undermined its ability to subvert state structures, as the central government deposed its allies in the state government and launched counterinsurgency operations. While ULFA’s ‘aura’ and popular support endured beyond 1990, it was forced into a rapid retreat from much of its governance activities. The article concludes by reflecting on the implications of the rise and fall of ULFA’s ‘parallel government’ for the relationship between rebel governance, territorial control and institutions more broadly.

De-centring ‘stateness’ in rebel governance

The field of rebel governance emerged as part of a shift away from framing civil wars as the collapse of order towards understanding conflict zones as ‘ordered pieces of territory’.Footnote12 The notion that rebels could construct and maintain order came as a counterpoint to the Hobbesian notion – once prevalent in the civil wars literature – that states were the sole providers of order and rebels the agents of disorder.Footnote13 Rebel governance scholars have since unearthed a diverse ‘archipelago of local rebel political orders’ across conflict zones.Footnote14 This scholarship has highlighted how group type, objectives and local contexts have shaped variations in the scope and depth of the provision of services,Footnote15 the dispensation of justiceFootnote16 and the formation of local institutions.Footnote17 Emerging as a counterpoint to the idea of civil war as the ‘collapse’ of order, much of this work understandably draws from the state formation literature to illustrate how rebels too can create order. Rebel governance projects are thus associated with embryonic states,Footnote18 counter-states, or states within states.Footnote19

This lingering state-centrism has meant that a number of assumptions have carried over from the state formation literature and become engrained in how the field understands the conditions and characteristics of rebel governance. This article builds on recent calls to relax two tightly-connected assumptions; that to govern, rebels need to control territory, because territorial control enables the development of the institutions necessary to rule.Footnote20

The first assumption contained within this statement is the centrality of territorial control as a prerequisite to governance. Most research on rebel governance essentially starts from the assumption that ‘effective control over territory makes governance possible’.Footnote21 The logic underpinning this assumption is that territorial control allows rebels to establish structures and institutions through which to interact with and solicit participation from civilians. This assumption has been built into the very definition of rebel governance, which Kasfir defines as ‘the organisation of civilians within rebel-held territory’.Footnote22 Most rebel governance research has thus essentially explored how rebels govern once they control territory.Footnote23 This has had the effect of skewing the balance of cases studied towards those in which rebels exercise territorial control, while under-theorising those in which territorial control is contested, overlapping or non-existent.

The second, closely-related assumption emerging from this, as Loyle et al highlight, is that territorial control paves the way for ‘institutions and infrastructure [to] enable governance’.Footnote24 While recent scholarship has highlighted important variations in the depth, degree of institutionalisation and quality of rebel political institutions,Footnote25 the assumption has generally held that rebels need to establish formal institutions if they are to govern. Given the frequency with which rebels develop (or attempt to develop) formal institutions, this assumption is an understandable one. As Karen Albert has highlighted, almost 64% of rebels in the post-war era created at least one governing institution.Footnote26 With territorial control largely seen as a precondition of rebel governance, there is a tendency to focus on particularly ‘state-like’ cases with developed political, judicial and bureaucratic institutions, to the exclusion of cases where governance is informal, delegated or hybrid, comprising an assemblage of actors.Footnote27

Recent works have made important calls to relax these assumptions.Footnote28 Territorial control, rather than being seen as a critical determinant of whether governance can take place, should instead be understood as a spectrum along which the degree of rebel governance varies.Footnote29 Rebels may control territory more firmly at certain times of day, month or year (monsoon season, for example). Degrees of control may vary from near-exclusive rebel control, to overlapping forms of states and rebel control, to highly minimalist forms of rebel presence.Footnote30 These varying degrees of overlap, as works on wartime political order have highlighted,Footnote31 can create an array of possible institutional assemblages of authority and governance that go beyond the notion of rebels establishing their own structures and institutions.

A number of works have started to highlight this array of possibilities. Ashley Jackson highlights how Taliban rebel governance predated territorial control through its ‘creeping influence’ into government-controlled areas, adopting a blend of ‘atmospheric coercion, punctuated by occasional violence’.Footnote32 Accounts of Hezbollah’s rebel governance for example highlight how the group is both simultaneously enmeshed within state structures while operating its own independent governance structures.Footnote33 In the Naga-inhabited areas of Manipur, Northeast India, Thakur and Venugopal highlight how the main Naga rebel group, the National Socialist Council of Nagalim–Isak-Muivah (NSCN–IM), and local state structures operate parallel governance institutions with varying degrees of independence from and interdependence with one another depending on the specific sector of governance.Footnote34 These cases highlight important degrees of hybridity, but nonetheless continue to focus on powerful rebel groups with well-developed governance structures and institutions. If we are to unravel the full spectrum of hybridity in territorial control and rebel institutions in rebel governance, we need to explore cases towards the minimalist end of this spectrum and analyse the conditions that underpinned and facilitated rebel governance practices.

The ULFA Insurgency in Assam, Northeast India

This article adds to this broadening understanding of hybridity in rebel governance by introducing the ULFA insurgency from Assam, the largest and most-populous state in India’s understudied Northeast region. Unlike rebel governance in the neighbouring Naga conflict, which has received growing attention in recent years,Footnote35 ULFA’s ‘parallel government’ has surprisingly received no attention in the rebel governance literature. Indeed, unlike the main Naga rebel groups, which have developed governing institutions such as the GPRN and the Federal Government of Nagaland (FGN), ULFA has long been considered to be far more disorganised and lacking in guerrilla warfare skills.Footnote36 This is perhaps due to the group’s more recent history; since its heyday in the late 1980s, pressure from counterinsurgency operations and deepening internal fissures pushed the group away from being a mass-based insurgency towards a predominantly cross-border group alienated from its support base from the mid-1990s onwards. Yet while ULFA established neither any territorial control nor extensive institutions, the group governed large swathes of Assam during the peak of its insurgency, which occurred from the late 1980s until large-scale military COIN operations began in the early 1990s.

The ULFA insurgency itself originated in post-Independence mass movements to protect Assamese culture, language and economic resources against perceived threats from illegal migration and New Delhi’s exploitative, colonial treatment of the ‘unheeded hinterland’.Footnote37 Fears that the Congress government had deliberately manipulated Assam’s electoral lists to include illegal migrants in a bid to use them as a ‘vote bank’ for the Congress sparked the 1979–1985 Assam Movement, a large-scale social movement spanning a broad coalition of civil society and student organisations. State responses to the agitation, including forcing a controversial election in 1983, combined with lingering perceptions that Assam’s natural resources were being exploited by Delhi, deepened secessionist sentiment within the movement.Footnote38 The movement, spearheaded by the All Assam Students Union (AASU) and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP), was mostly nonviolent and characterised by mass rallies, blockades and strikes, but violent clashes between protestors and police, communal violence including the notorious Nellie Massacre of 1983 and bomb blasts against opponents of the agitation led to a growing normalisation of violence that facilitated ULFA’s rise.Footnote39 Following negotiations between AASU, AAGSP and New Delhi, the Assam Accord was signed in 1985 and contained provisions to protect Assamese identity, language and culture. Leading agitation members then formed the Asom Gana Parishad (AGP), winning the 1985 state assembly elections with 67 of the state’s 126 seats and becoming the incumbent state government.Footnote40 However, lacklustre implementation of the accord’s provisions deepened frustration with the central government, creating the conditions for ULFA’s meteoric rise.

ULFA was formed in 1979 on the radical fringes of the Assam Movement with the aim of creating an independent, sovereign Assam. During the years of the agitation itself, the group generally maintained a low profile. ULFA tapped into the starkly visible economic inequalities of tea garden life in Assam, while recruiting from mainstream sections of the Assam movement.Footnote41 The group established a series of camps (see ) and sought training from neighbouring Naga insurgents. From 1984–1985, the group gradually became more active, killing opponents of the Assam agitation, politicians associated with the 1983 elections, and conducting a series of daring bank raids. During 1985–1990, ULFA considerably intensified its activities, widening its targets to include state officials, economically influential individuals and members of ‘outsider’ business communities such as the Marwaris.Footnote42 By the time military operations were launched against the group in November 1990, ULFA had built a well-armed organisation of approximately 1,000–3,000 cadres and was responsible for at least 113 deaths.Footnote43

Figure 1. ULFA Camps 1986–1990.Footnote44

Enabling ULFA’s ‘parallel government’

ULFA initiated an array of governance activities during the 1985–1990 period, conducting forms of service provision in outlying communities, setting up informal, rudimentary court institutions to punish immoral activities and taxing industries long considered exploitative, such as the tea gardens of Upper Assam. By 1988, ‘ULFA’s influence was visible in every sphere of public life in the Brahmaputra Valley’,Footnote45 described by former publicity secretary Sunil Nath as ‘the government in those days’.Footnote46 This situation changed rapidly in November 1990, when the central government dismissed the AGP, declared central rule and launched Operation Bajrang against the group.Footnote47 While ULFA retained influence across Assam until well into the 2000s, its ‘invincible halo’ dissipatedFootnote48; much of the group’s leadership and operational cadre base were forced to relocate to camps in Bhutan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. Becoming increasingly physically disconnected from its core constituents, ULFA’s governance activities were ‘quickly pushed into the background’ in favour of a more straightforward campaign of military survival and cross-border strikes.Footnote49 For this reason, this article focuses on the 1985–1990 period.

Although ULFA was able to extend its influence across large swathes of Assam, at no point did the group control territory, in the sense of a capacity to keep opponents out of a specific area.Footnote50 Even in the upper-most districts of north-eastern Assam and its forest hinterlands, where ULFA’s strongholds lay and where the state has long retained only a minimalist presence, the group never established an open presence in truly defensible ‘liberated zones’ that state forces were required to later retake. Instead, ULFA’s camps, typically located deep within forested areas, functioned as sanctuaries that quickly dissipated after counterinsurgency operations were launched in 1990. While this indicates that territory in fact played some role in ULFA’s approach, its governance activities were by no means confined to the forested areas around their camps and their immediate localities, but extended into and penetrated areas where the state had a far greater presence.

With the exception of limited, largely informal judicial institutions in outlying areas, the group did not establish widespread administrative or political institutions designed to formalise rebel-civilian relationships. For ULFA, a 1,000–3,000-strong organisation in a state of 22.4 million, rebel governance instead relied on casting a shadow over Assamese social and political life. The group combined selective violence with widespread publicity from sympathetic local media to project an aura of power and authority,Footnote51 exercising social rather than territorial control. For the group’s foes, this created a ‘fear psychosis’ whereas for sympathisers and supporters it amplified the perception of the group as a ‘Robin Hood’ actor. This a-territorial, informal form of governance depended on its shared networks with former members of the Assam agitation. With agitation leaders holding the reins of state power in the state and with ULFA well-positioned to ride the broader wave of pro-agitation sentiment, this allowed the group to ‘infiltrate almost every level of governance and society’, for a time dominating the Assam Movement and in doing so generating a far-reaching impact across Assamese society.Footnote52 This section analyses these three closely-connected conditions, before illustrating how they enabled ULFA’s rebel governance in practice.

Social embeddedness

ULFA’s governance was facilitated to a great extent by its ability to leverage pre-existing social ties with an array of allies across Assamese society. Although the organisation emerged on the radical fringes of the Assam Movement, the group’s pro-secessionist ideology based on securing independence from colonial exploitation from the ‘step mother at the centre’ resonated ideologically with mainstream political discourse in Assam during the agitation.Footnote53 Crucially, many of ULFA’s early leaders shared the same activist networks with both other fringe and more mainstream organisations. Several founding ULFA members had for instance been members of the Asom Jatiyatabadi Yuva Chhatra Parishad (AJYCP), a radical student organisation critical of India’s ‘neo-colonial’ rule.Footnote54 For local academic Nani Gopal Mahanta, given the overlap between the two during ULFA’s formative years, ‘practically there were no differences between the ULFA and the AJYCP’.Footnote55 As members of ULFA participated in the agitation, they developed mutual associations with members of the All Assam Students Union (AASU), the main student body spearheading the agitation, and All Assam Gana Sangram Parishad (AAGSP), a political body constituted by the AASU. Each of these organisations were made up of broad coalitions containing elements of the Assamese urban middle classes as well as disaffected rural masses from the ‘hinterlands’.Footnote56 ULFA’s presence within these pro-agitation networks not only meant that it shared a broad ideological space with large swathes of the Assam Movement, but crucially meant that it was able to mobilise and co-opt specific organisations and components of civil society to support and promote its governance activities while nullifying action against it.

Penetration of state structures

Arguably the critical factor enabling ULFA’s rebel governance in the absence of territorial control and the development of governing institutions was its ability to effectively muzzle state repression and selectively leverage elements within the state as an institution and controller of (some) territory to augment its own governance efforts while projecting its own authority. As one journalist posted in Assam at the time recalled, while ‘[ULFA] did not have their own machinery, [.] they influenced and, in some areas, controlled the government machinery’.Footnote57 This process, which combined elements of both co-option and subversion, took place at different levels within the state, ranging from the highest levels of state politics in Assam to localized penetration of the district and village-level administration and police.Footnote58

The election of the AGP government in 1985 effectively extended ULFA’s social networks into the corridors of power in Guwahati. As the political party of the agitation emerging directly from the AASU and AAGSP there was a social and ideological ‘commonality’ between the AGP and ULFA.Footnote59 The group’s General Secretary, Anup Chetia, and chairman Arabinda Rajkhowa were, for instance, members of the AAGSP during the early 1980s.Footnote60 Indeed, elements of the AGP administration openly expressed sympathies for ULFA members. The then state government Home Minister, Brighu Phukan, stated for example that ‘they [ULFA] are from among us’.Footnote61 This ideological affinity did not create a clean, unproblematic state-armed group relationship. Rather, ULFA’s penetration mapped onto and exploited the party’s internal factional politics, particularly the rivalries between the Chief Minister Prafulla Kumar Mahanta and the Political Department led by Home Minister Brighu Phukan, to shape deal-making that, for ULFA, would at least paralyse the state government response.Footnote62

As the AGP’s tenure became plagued by dissatisfaction over its inability to implement the Assam Accord,Footnote63 elements of the party increasingly saw opportunities to ‘ride the tiger’ of ULFA’s growing popularity to extract concessions in implementing the Assam Accord from the central government.Footnote64 ULFA’s leadership, moreover, was aware that it could not grow and operate freely at the grassroots level without securing non-intervention from central and state-level security forces.Footnote65 Therefore, through a combination of ideological overlaps, political incentives to tolerate ULFA activities, offers to take a cut out of extortion money and direct pressure from ULFA,Footnote66 a tacit form of collusion and cooperation deepened between elements within the AGP administration and ULFA throughout 1985–1990. This cooperation ranged on a spectrum from direct forms of assistance to subverting efforts to counter it. During the Statefed rice scandal, for example, funds were misappropriated from a contract worth Rs. 20 million ($1,144,000 in 1990 U.S. dollars) to supply rations. When the then-Education Commissioner investigating the charges complained about the investigation’s slow progress, the Chief Minister told him ‘the money is for the boys’.Footnote67

ULFA exploited this tacit arrangement to limit attempts to arrest its cadres or counter its activities. India’s state governments are constitutionally responsible for law and order, and the Director General of the state’s police is directly answerable to the Chief Minister.Footnote68 This gives the political administration a great deal of influence over policing. The AGP administration refused to declare ULFA-affected districts ‘disturbed’ thereby sanctioning a security forces response, despite repeated requests from New Delhi.Footnote69 Furthermore, ministerial interventions into policing created a culture of inaction against ULFA. As one police officer noted: ‘whenever we got the ULFA boys arrested, they usually got released very quickly with the interference of the AGP ministers at that time’.Footnote70 This was ‘just a phone call away;’ ULFA members were simply able to say ‘it is our boy’ and in doing so secure their release.Footnote71 Police officers that were ‘too aggressive’ against ULFA were ‘moved out’, creating a culture that ‘you are not expected to act’.Footnote72 Later reports moreover disclosed that up to 500 individuals with ‘close ULFA links’ had been recruited into the police force during the AGP years, supplying intelligence to the group and even occasionally residing in major ULFA camps,Footnote73 underlining the extent of ULFA’s ability to subvert state attempts to counter it. By 1990, then, Governor D.D. Thakur lamented that:

The loss of faith in the efficacy and the credibility of the government apparatus is so great that the distinction between ULFA, AASU and AGP, which existed at some stage, stands totally obliterated.Footnote74

This combination of tacit arrangements with ideological allies and subversion and domination at the local level thereby effectively negated the need for territorial control. ULFA’s influence upon elements of the AGP meant that it was able to subvert efforts to counter it at the highest levels of the state government. With this permissive environment established, it was then able to dominate local state assets through a combination of co-option, coercion and subversion, meaning it was able to utilise elements of the state administration to conduct its governance activities.

Casting the shadow: vernacular media and ULFA

Crucial to the development of ULFA’s aura of social control was its use of highly selective, demonstrative – and therefore widely publicized – acts of violence to both appeal to allies within the Assam Movement as well as to intimidate opponents. Indeed, Nani Gopal Mahanta notes that during the early 1980s, ULFA’s activities were particularly brutal or shocking, ‘with the obvious objective of drawing attention’ to the organisation.Footnote75 During this period, ULFA entered the public eye by killing leading public figures opposed to the Assam Agitation, such as those responsible for the 1983 state assembly elections. A series of daring bank raids, such as a high-profile raid on a United Commercial Bank branch in Guwahati in 1985, amplified this ‘demonstration effect’ and brought ULFA’s activities into focus.Footnote76

To some extent, ULFA was able to benefit from elements of the Assamese vernacular press sympathetic to at least some of the group’s actions.Footnote77 However, as works on the relationship between the media and terrorism indicate, publicity does not have to be sympathetic to nonetheless support a strategy of simultaneously spreading fear and mobilizing support amongst key target populations.Footnote78 ULFA’s demonstrative acts of violence, its public moral policing (often in the form of public humiliation of offenders), and symbolic acts of forcing state officials to participate in service provision all attracted significant media attention.Footnote79 This made ULFA’s ideology, objectives and targets common knowledge. This enhanced ULFA’s social control beyond the immediate audience by undermining confidence in and support for the government, intimidating a broader audience of opponents while appealing to allies and constituents in sympathetic communities across Assam.

ULFA recognized the centrality of shaping media narratives, establishing the position of publicity secretary and actively seeking to establish links with local journalists to convey the group’s narratives. For instance, when ULFA encountered local resistance from an activist body highly critical of ULFA, the United Reservationist Minority Council of Assam (URMCA) – in June 1990, the group escorted a group of journalists to remote villages in Lakhimpur and arranged a press conference to ensure that the group’s perspectives were conveyed in the press.Footnote80 ULFA militants have also used coercion, issuing diktats to the press and intimidating journalists to ensure that particular messages are carried.Footnote81 By combining these demonstrative acts with a strategy to engage local media, ULFA was able to spread a ‘fear psychosis’ amongst its opponents while generating a ‘Robin Hood’-like image amongst those potentially sympathetic to its activities.

ULFA rebel governance

The following section highlights how the above conditions enabled ULFA’s parallel government to function by analysing three core, closely interlinked aspects of ULFA rebel governance: service provision, moral policing and taxation. Analysing these three elements, which are common across both the practice and study of rebel governance, thereby serves to illustrate the functioning of rebel governance in the absence of territorial control.

Service provision

A central part of ULFA’s strategy to mobilise popular support and boost its ‘Robin Hood’ image in rural Assam was to engage in an array of development activities, ranging from building road and bridge infrastructure, building and maintaining flood defences, farming and irrigation projects and the construction of schools.Footnote82 These forays into service provision were not the result of an established set of service-providing governance institutions designed by the group itself, nor did it create any formal governance infrastructure to supplant that of the state. Instead, ULFA usually coordinated welfare provision and construction work on individual projects by coercing, co-opting and directing an assemblage of non-state and local Indian state actors. This ability to leverage both local allies and the resources of the district-level state administration allowed the group to conduct ‘on the spot’ service provision that required neither territorial control nor significant investments in infrastructure.Footnote83

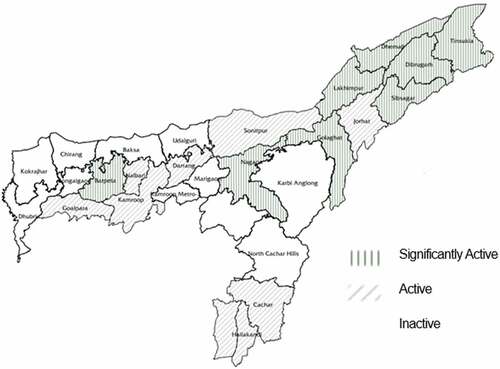

For instance, ULFA frequently worked alongside the Asom Jatiya Unnayan Parishad (JUP),Footnote84 a local development organisation formed in 1989, enabling it to engage in service provision ‘in almost every part of the Brahmaputra Valley in Assam’.Footnote85 The JUP is often labelled a front organisation of ULFA. While often denied, this charge does reflect the extent of the overlapping ties and shared membership between the two organisations and the strong overlaps between the ULFA and JUP areas of activity, which spanned large swathes of the Brahmaputra Valley of northern Assam (see ). The JUP was known for carrying out unimplemented government welfare projects where key development needs had already been identified by communities,Footnote86 often in response to the regular damage wrought by the Brahmaputra Valley’s flood seasons.Footnote87

Figure 2. Assam JUP Activity.Footnote96

ULFA’s influence on service provision essentially came through its association with the JUP, playing a key role in encouraging and supporting aid projects by both persuading, coercing and organising local labour, often involving entire villages.Footnote88 In Biphuria, Lakhimpur district of north-eastern Assam, for example, ULFA and the JUP mobilized at least 5,000 villagers from diverse communities to work on a flood defence project. In another example from 1990, ULFA’s Nityananda Anchalik Committee organised around 100 locals to build an embankment near Golaghat Bridge.Footnote89 ULFA was also involved with longer-term projects, including supervising the construction of local colleges and overseeing the development of cooperative farms that its JUP allies could then run in the longer-term.Footnote90 Taking up unimplemented government projects based on existing, locally-identified needs enabled ULFA to be seen to respond to local demands, while at the same time exposing the weaknesses of the state.

Since police interventions were discouraged to a great extent by the state administration, local state officials were forced to cooperate with ULFA projects on the ground, particularly in Lakhimpur and Dhemaji districts.Footnote91 As one government official posted in an ULFA-affected district stated:

For us, the choice was clear: toe the line prescribed by the ULFA leaders or get into trouble since it was clear that they had a tacit understanding with the political leadership. Whatever they demanded, had to be fulfilled. The requirements initially ranged from free use of telephone and official cars to improvement of roads or other facilities in a particular village.Footnote92

In some cases, ULFA played a much more assertive role, forcing state police, local officials and other elites (such as tea garden managers) to participate in the labour of building river embankments, cleaning community houses and maintaining sanitation facilities and in doing so showcasing their local dominance.Footnote93 These activities further amplified the ‘Robin Hood’ image which strengthened ULFA’s legitimacy in the rural hinterlands. For example, when police took part in an ULFA-JUP-organised flood defence reconstruction project in Biphuria, Lakhimpur district of north-eastern Assam, local observers noted that ‘it was a sight to watch how the local police went [.] to work in the site [.] all of us were delighted and could not stop appreciating the [ULFA] boys’.Footnote94 In other examples from 1990, the wives of police officers and in one case a deputy commissioner of the district administration assisted in these activities.Footnote95 While these service provision activities were only occasionally publicised, they consolidated local support for the organisation. Furthermore, some stories did appear in the vernacular press and thus continued to garner the image of a ‘Robin Hood’ actor beyond the area of activity, while undermining the credibility of the Indian state, until 1990.

Moral policing

Through its ability to tap into local social networks and subvert – and in some cases dominate – local state institutions, ULFA was able to regulate social life almost unchallenged in its areas of influence. Exploiting public discontent with the notoriously slow-moving nature of the Indian judicial system, the group issued diktats against and publicly punished social ills, including sexual harassment, prostitution, gambling, drugs and alcohol production and consumption, and bribery.Footnote97

The scope of ULFA’s judicial activities varied. In its rural strongholds, the group developed ‘people’s courts;’ ULFA’s only foray into institutional development, these limited, usually informal judicial institutions were designed to hear complaints about immoral behaviours and rapidly dispense justice through public acts of violence. According to Governor D. D. Thakur’s report to the President in November 1990, these courts had supplanted the judicial institutions of the Indian state in Lakhimpur, Tinsukia and Dibrugarh.Footnote98 Indeed, in Lakhipathar, near one of ULFA’s largest camps, ‘ULFA penetrated into almost all spheres of life’, influencing social practices such as dress codes (banning clothes representing ‘Indianness’) and regulating the conduct of personal relationships.Footnote99 Beyond its sanctuaries, the functioning of these courts relied on ULFA’s subversion and co-option of the state; ULFA members in Dibrugarh for instance openly used the guest house of the State Electricity Board to run their court sessions.Footnote100 Most of ULFA’s judicial interventions consisted of ad hoc acts of humiliation or violence against offenders. For example, in Guwahati in December 1989, three youths suspected of selling illegal alcohol were made to kneel in front of a cinema in a display of public humiliation, while the police did not intervene. In other instances of highly demonstrative violent acts, dead bodies were left in public places, marked with ULFA logos and ULFA statements were released detailing the reported crimes of the accused.Footnote101

Taxation

Recent works have noted that rebel taxation should be seen as ‘a technology of governance that rebels deploy to resolve a variety of political, economic, and organisational challenges’.Footnote102 ULFA’s taxation practices, which predominantly targeted exploitative or ‘outsider’ businesses and industries such as the tea industry, sought to resolve two key challenges. First, the group’s taxation sought to address organisational challenges; ULFA needed to finance its internal organisation-building, training and arms procurement, which was rapidly expanding and becoming increasingly expensive by the end of the 1980s.Footnote103 Second, ULFA’s approach to taxation is shaped ideologically by the group’s emergence from the Assam Agitation, specifically through its ideological opposition to extractive, ‘colonial’ enterprises and exploitation and the disproportionate influence of so-called ‘outsiders’ in the local economy. The logic of ULFA taxation was essentially that since tea industrialists and outsider businessmen were at the helm of vast economic inequalities, and since international companies such as Williamson Magor extracted huge profits from Assam, these industries should be give back to Assam.Footnote104 In this sense, ULFA’s taxation practices are fundamentally linked to its attempts to regulate moral conduct.

ULFA taxation was therefore highly selective in its targets. ULFA militants would for instance collect intelligence from lower-level tea garden managers from within the community to determine local grievances and cases of managerial abuse, and use this information to leverage tax demands.Footnote105 This selective practice differs for example from the nearby Naga armed groups whose taxes span the entirety of Naga society in a bid to support their claims as sovereign, separatist entities.Footnote106 The practice of taxation itself was ad hoc and far from institutionalised during the late 1980s. The scope of the demands themselves fluctuated between requests for increasingly large sums of money to more redistributively-focused demands blurring the lines between taxation and service provision. This included, for example, ULFA demands that tea gardens upgrade local medical facilities or institute scholarships for disadvantaged youths.Footnote107 To support its service provision efforts in conjunction with the JUP, ULFA also directly seized payments-in-kind such as manure, seeds and tools to aid its agricultural welfare projects,Footnote108 while collecting financial donations from other local businesses.

Rather than formally controlling the areas where tea gardens resided, ULFA’s taxation relied on its ability to generate atmospheric coercion, or ‘fear psychosis’ as it was popularly known in Assam at the time. Demands to tea gardens would for instance typically begin by taking away a tractor, paying a visit, or inviting tea garden managers to a meeting following a threatening phone call.Footnote109 With the police unable to respond substantively, ‘a simple telephoned threat, the display of weapons by tough-looking militants, “friendly advice” or even an occasional roughing up was enough to help local traders part with millions of rupees’.Footnote110 Indeed, ULFA collected between Rs. 4–5 billion ($285,000,000) in extortion funds during the 1985–1990 period, underlining the extent to which this atmospheric coercion was successful.Footnote111 At the same time, this strategy of coercion and violence, targeted as it was at symbols of wealth and exploitation in Assamese society, resonated with the group’s ‘Robin Hood’ image of taking from the rich to give to the poor.

These underlying conditions and the governance activities enabled by them produced a self-reinforcing dynamic that contributed to the group’s meteoric organisational growth during the late 1980s. ULFA’s pre-existing social embeddedness within the broader ethnonationalist movement provided it with a broad support base upon which it could both rely on for pre-existing social ties that would enable governance. Its ability to reach these constituents (and intimidate potential opponents) was enhanced by its ability to generate widespread vernacular media coverage. Its social embeddedness then enabled it to penetrate the state structures of the AGP government, preventing significant state responses against it.

ULFA’s governance activities fed back into and reinforced these conditions. The group’s service provision activities frequently co-opted allied organisations while forcing ‘others’ or state actors to participate in these projects, enhancing the group’s ‘Robin Hood’ appeal to its constituents. Similarly, widely-publicised instances of moral policing and taxation of exploitative industries both intimidated potential ‘others’ while again enhancing the group’s appeal to its support base.Footnote112 This self-reinforcing dynamic contributed to ULFA’s meteoric growth in its organisation, popularity and presence across Assam during the late 1980s. By 1990, the Governor of Assam D. D. Thakur estimated that the group had recruited up to 3,000 cadres.Footnote113

Collapse

However, as the organisation rapidly grew, new tensions began to emerge within this interaction between the underpinning conditions and the governance activities that ultimately contributed to its rapid downfall. From 1988 in particular, the group’s costs increased significantly. Its recruitment base was growing rapidly, it had established its base of operations in its forest sanctuary of Lakhipathar, and had secured an agreement to send a second batch of ULFA cadres to train with the Kachin Independence Army, an armed group operating in northern Myanmar. At the same time, ULFA’s service provision in conjunction with the JUP was placing a growing financial burden on the organisation, while the ad hoc nature of these activities meant that financial collections to sustain them often lacked accountability.Footnote114

The regularity and size of ULFA’s demands thus increased, as did its propensity to use violence to enforce these demands.Footnote115 The killing of Surendra Paul, Managing Director of Assam Frontier Tea Ltd. in April 1990 led to a dramatic flurry of negotiations between ULFA and representatives of the major international tea corporations in Assam. However, following complaints made by the tea corporations to Indian diplomats abroad, the central government increasingly became aware of the ULFA problem. Frustrated by the AGP’s inaction, in November 1990 Delhi arranged to dramatically airlift tea executives out of Assam without informing the state government.Footnote116 By the end of the month, the central government deposed the state government and declared ‘President’s Rule’, before deploying the Army and launching counterinsurgency operations. This undercut the group’s ability to limit state repression and in doing so facilitate its rebel governance. As a result, ULFA’s ability to direct and coordinate welfare activities with and through the JUP and other local allies quickly dissipated in the face of Indian Army operations.Footnote117

The three conditions of social embeddedness, state penetration and a conducive media environment created the conditions for the rapid expansion of ULFA’s rebel governance activities. The swiftness with which ULFA’s rebel governance efforts collapsed following the end of the AGP administration highlights the importance of the group’s subversion of state structures as a critical enabler of its governance programme.

Conclusion

Building on recent calls to de-centre territorial control and political institutions as key conditions for rebel governance, this article has utilised the often-overlooked case of ULFA’s five-year ‘parallel government’ in Assam in order to demonstrate the existence of – and the importance of studying – non-territorial forms of rebel governance.

The ULFA case, by challenging the centrality of territorial control and the existence of formal institutions emerging from it, underlines the importance of going beyond notions of ‘stateness’ as ‘the model and basis with which to compare rebel organisational structures’Footnote118 and the importance of focusing on the social and political ordering structures enabling non-territorial rebel governance. Existing research has already highlighted the existence of differing forms of political order in rebel-held territory, how they relate to institutions and how they evolve over time.Footnote119 As this article illustrates, this agenda can be extended into the realm of non-territorial rebel governance by better integrating the state and its interactions with both rebels and civilians.Footnote120 Comparative research could build on this by overlaying rebel governance data with data on state-group armed orders to explore whether certain types of state-armed group orders are more conducive than others to the development of non-territorial rebel governance.

The article further demonstrates that although ULFA rebel governance was primarily non-territorial in nature, place and space still played an important role in how the group operated. Even in the absence of territorial control, insurgents require some degree of sanctuary from which to operate, whether in the form of clandestine camps in difficult-to-access or foreign bases, underground networks, sacred spaces,Footnote121 or strongholds of support in cities. In the ULFA case, sanctuary was ensured by both nullifying the state response against it, by operating in rural communities in conjunction with local allies and by placing camps in remote jungles. This underlines the challenges of viewing sanctuary as a physical, territorially-based construct alone and supports existing calls to integrate the layered, textured nature of armed group sanctuaries into rebel governance research.Footnote122 Further research should examine an insurgency’s relationship to place and sanctuary, the reasons behind this and the opportunities and constraints this relationship places upon efforts to govern civilians. Here there are opportunities to better integrate notions of territoriality into our understanding of rebel governance,Footnote123 particularly in thinking about how rebels relate to space and place, whether insurgent capacities match these conceptions, and whether and how these intersect with civilians’ own understandings.Footnote124

Lastly, ULFA’s rebel governance raises questions of the relationship between temporality, the functioning of rebel organisations and pressures towards institutionalisation. Most of ULFA’s governance interventions required only temporary interventions into local communities without the need for institutions, laying the foundations for local allies. However, as ULFA grew as an organisation, institutional funding pressures forced tax demands of ever-increasing regularity and size, ironically creating the conditions for the downfall of the parallel government. Using non-territorial rebel governance as a starting point, further research should draw greater attention to the nascent, intermediary stages of rebel governance, analysing the functional pressures that drive shifts towards institutionalisation and territorial control.

Acknowledgments

Fieldwork in India was conducted in 2016 during visiting fellowships in India with the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. I thank Dr David Brenner, Dr Elisabeth Leake, participants of the 2022 European Scholars of South Asian International Relations conference, and lastly the reviewers for their thoughtful and constructive suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alex Waterman

Alex Waterman is a Research Fellow (India/Asia) at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA), Hamburg, Visiting Fellow at the University of Leeds and Co-Editor of Civil Wars. His research has been published in leading journals such as International Peacekeeping, Asian Security and Civil Wars, and in 2020 his doctoral research won the Global Policy North Outstanding Thesis Prize. He has held affiliations with the Modern War Institute at West Point, the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS), Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (MPIDSA) and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS).

Notes

1. Loyle et al., ‘New Directions in Rebel Governance Research’, 6–7.

2. Worrall, ‘(Re-)Emergent Orders’, 716.

3. See note 1 above.

4. Péclard and Mechoulan, Rebel Governance and the Politics of Civil War, 18.

5. Thakur and Venugopal, ‘Parallel Governance and Political Order in Contested Territory’; Suykens, ‘Comparing Rebel Rule Through Revolution and Naturalization: Ideologies of Governance in Naxalite and Naga India’.

6. Interview with a retired police official, 2016.

7. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 55–56; Mahanta, Confronting the State, 85; Hazarika, Strangers of the Mist, 176.

8. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 30–31.

9. Jackson, ‘Life under the Taliban Shadow Government’.

10. The notion of ‘fear psychosis’ gripping Assam was highlighted across interviews with local politicians, journalists and civil society members.

11. Volo and Schatz, ‘From the Inside Out’, 270.

12. Arjona, ‘Local Orders in Warring Times: Armed Groups’ and Civilians’ Strategies in Civil War’, 16; Waterman and Worrall, ‘Spinning Multiple Plates Under Fire’.

13. Worrall, ‘(Re-)Emergent Orders’, 710.

14. Mampilly and Stewart, ‘A Typology of Rebel Political Institutional Arrangements’, 29.

15. Stewart, ‘Civil War as State-Making’.

16. Loyle, ‘Rebel Justice during Armed Conflict’.

17. Mampilly and Stewart, ‘A Typology of Rebel Political Institutional Arrangements’.

18. See note 4 above.

19. Spears and Kingston, States-Within-States: Incipient Political Entities in the Post-Cold War Era.

20. Loyle et al., ‘New Directions in Rebel Governance Research’, 6.

21. Kasfir, ‘Rebel Governance – Constructing a Field of Inquiry: Definitions, Scope, Patterns, Order, Causes’, 28.

22. Kasfir, 24.

23. Kasfir, 22; Arjona, Rebelocracy, 44–45; Furlan, ‘Understanding Governance by Insurgent Non-State Actors’, 478; Schwab, ‘Insurgent Courts in Civil Wars’, 803.

24. See note 20 above.

25. See note 17 above.

26. Albert, ‘What Is Rebel Governance?.

27. For a notable exception see Wenner, ‘Trajectories of Hybrid Governance’.

28. Florea, ‘Authority Contestation during and after Civil War’, 151–52; Loyle et al., ‘New Directions in Rebel Governance Research’.

29. Florea, ‘Authority Contestation during and after Civil War’, 152.

30. Worrall and Waterman, ‘Taxonomies of Rebel Governance’.

31. Staniland, ‘States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders’, 248.

32. Jackson, ‘Life under the Taliban Shadow Government’, 25.

33. Worrall, ‘(Re-)Emergent Orders’.

34. Thakur and Venugopal, ‘Parallel Governance and Political Order in Contested Territory’.

35. This recent attention is perhaps due to the visible trappings of ‘stateness’ in Naga rebel governance institutions. Thakur and Venugopal; Suykens, ‘Comparing Rebel Rule Through Revolution and Naturalization: Ideologies of Governance in Naxalite and Naga India’; Mampilly, ‘Rebel Taxation: Between Moral and Market Economy’; Waterman, ‘Ceasefires and State Order-Making in Naga Northeast India’.

36. Rammohan, Insurgent Frontiers, 48; Singh, The ULFA Insurgency in Assam, 49. State practitioners during interviews would often draw unfavourable comparisons between ULFA and the Naga factions; Naga guerrillas were often framed as more capable, honourable and worthy of respect than their ULFA counterparts.

37. Gogoi, ‘Sovereignty and National Identity: The Troubled Trajectory in Northeast India’, 6–7; Misra, The Periphery Strikes Back, 128–45.

38. Weiner, ‘The Political Demography of Assam’s Anti-Immigrant Movement’, 288.

39. Assam Police data records a total of 471 bomb blasts and 101 fatalities during 1979–1984. See Mahanta, Confronting the State, 48; The Nellie Massacre involved the sectarian killing of 2,000 Bengali-origin Muslims. See Kimura, The Nellie Massacre of 1983.

40. Chadha, Low-Intensity Conflicts in India, 242.

41. Goswami, India’s Internal Security Situation, 70.

42. Mahanta, Confronting the State, 72–85; Das, ULFA, 73–75; Hazarika, Strangers of the Mist, 176.

43. Baruah, Durable Disorder, 154; Goswami, ‘India’s Counter-Insurgency Experience’, 74.

44. Data drawn from Mahanta’s breakdown of ULFA camps during 1986–1990. See Mahanta, Confronting the State, 106–9. Map produced using http://164.100.167.25/mapmyexcel/.

45. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 51.

46. Nath, ‘Assam: The Secessionist Insurgency and Freedom of Minds’.

47. See note 40 above.

48. Hazarika, Strangers of the Mist, 185.

49. Saikia, ‘Allies in the Closet: Over-Ground Linkages and Terrorism in Assam’.

50. See note above 21., 26.

51. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 41–64.

52. See note 49 above.

53. See note 8 above.

54. Dutta, 30–31.

55. Mahanta, Confronting the State, 59–61.

56. See note above 38., 288.

57. Interview with a journalist posted in Assam during the late 1980s, 2016.

58. Sinha, ‘Insurgencies in North-East India: An Appraisal’, 50.

59. Interview with a retired police officer based in ULFA-affected districts of Lakhimpur during the 1980s, 2016.

60. Sarma, ‘Factional Politics in Assam’, 76.

61. Sarma, 153.

62. Sarma, 138, 153.

63. For an overview of the conditions hampering the Accord’s implementation see Sharma, ‘Immigration, Indigeneity and Identity: The Bangladeshi Immigration Question in Assam’, 97–98.

64. See note 59 above.

65. Interview with Assam-based journalist, 2016.

66. During an interview with the author in 2016, former Chief Secretary H.N. Das noted that AGP-ULFA relations were shaped by 1) ideological sympathies, 2) financial incentives and 3) pressure applied by ULFA. Interviews with journalists based in Assam highlighted the political incentives driving whether AGP members accepted or tolerated ULFA activities.

67. See note 48 above.

68. Sharma, Police and Political Order in India, 21.

69. Raghuvir, Governor D. D. Thakur’s Report to the President of India, 26.11.1990, reproduced in Peoples Union for Human Rights v Union of India.

70. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 51.

71. Interview with an Assam-based journalist, 2016.

72. Interview with a police officer posted in Lakhimpur, Assam during the 1980s, 2016.

73. Routray, ‘Terrorists in Uniform’.

74. See note 69 above.

75. Mahanta, Confronting the State, 75.

76. Mahanta, 75–76; Das, ULFA, 72–74.

77. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 71.

78. Nacos, Terrorism and Counterterrorism, 270.

79. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 44–63.

80. Dutta, 71–74; Five months prior, ULFA had bussed journalists from Guwahati to Lower Assam for a press conference. See Goswami, Along the Red River, 233.

81. Goswami, Along the Red River.

82. Mahanta, Confronting the State, 85; Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 78–86.

83. See note 20 above.

84. Translates as “Assam National Development Council.”

85. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 56.

86. Mahanta, Confronting the State, 82.

87. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 55–56.

88. Interview with local Assam-based journalist, 2016.

89. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 56, 82.

90. Dutta, 56; Mahanta, Confronting the State, 82–84.

91. Mahanta, Confronting the State, 81.

92. Gokhale, The Hot Brew, 25.

93. Das, ULFA, 83.

94. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 83–84.

95. See note 48 above.

96. Data drawn from Mahanta, Confronting the State, 81–82. Map produced using http://164.100.167.25/mapmyexcel/.

97. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 10, 51.

98. See note 69 above.

99. Khanikar, State, Violence, and Legitimacy in India, 179–81.

100. See note 92 above.

101. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 53–55.

102. Mampilly, ‘Rebel Taxation: Between Moral and Market Economy’, 83.

103. Das, ULFA, 84–85; Hazarika, Strangers of the Mist, 179.

104. See note 92 above.

105. Interview with a journalist based in Assam during the 1980s.

106. Mampilly, ‘Rebel Taxation: Between Moral and Market Economy’, 84–85.

107. See note 92 above.

108. Goswami, Along the Red River, 243.

109. Interview with a journalist based in Assam during the 1980s, 2016.

110. See note 48 above.

111. See note 69 above.

112. Saikia, ‘The Political Economy and Changing Organisational Dynamics of the ULFA Insurgency in Assam’, 47.

113. See note 69 above.

114. Dutta, Creating Robin Hoods, 84; Mahanta, Confronting the State, 85.

115. See note 92 above.

116. Gokhale, 38–40.

117. See note 49 above.

118. See note 4 above.

119. Arjona, Rebelocracy; Breslawski, ‘The Social Terrain of Rebel Held Territory’.

120. van Baalen and Terpstra, ‘Behind Enemy Lines’.

121. Fair and Ganguly, Treading on Hallowed Ground.

122. Innes, ‘Deconstructing Political Orthodoxies on Insurgent and Terrorist Sanctuaries’; Korteweg, ‘Black Holes’.

123. Sack, Human Territoriality.

124. Worrall, ‘(Re-)Emergent Orders’, 714.

References

- Albert, Karen E. “What Is Rebel Governance? Introducing a New Dataset on Rebel Institutions, 1945–2012.” Journal of Peace Research, 2022, 00223433211051848. https://doi.org/10.1177/00223433211051848.

- Arjona, Ana. “Local Orders in Warring Times: Armed Groups’ and Civilians’ Strategies in Civil War.” Qualitative Methods 6, no. 1 (2008): 15–18.

- Arjona, Ana. Rebelocracy: Social Order in the Colombian Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Baalen, Sebastian van, and Niels Terpstra. Behind Enemy Lines: State-Insurgent Cooperation on Rebel Governance in Côte d’Ivoire and Sri Lanka. Small Wars & Insurgencies (2022): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2022.2104297.

- Baruah, Sanjib. Durable Disorder: Understanding the Politics of Northeast India. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Breslawski, Jori. “The Social Terrain of Rebel Held Territory.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002720951857.

- Chadha, Vivek. Low-Intensity Conflicts in India: An Analysis. New Delhi: SAGE, 2005.

- Das, Samir Kumar. ULFA: United Liberation Front of Assam: A Political Analysis. Delhi: Ajanta, 1994.

- Dutta, Uddipan. Creating Robin Hoods: The Insurgency of the ULFA in Its Early Period, Its Parallel Administration and the Role of Assamese Vernacular Press (1985–1990). New Delhi: Wiscomp, 2008.

- Fair, C. Christine, and Sumit Ganguly, eds. Treading on Hallowed Ground: Counterinsurgency Operations in Sacred Spaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Florea, Adrian. “Authority Contestation during and after Civil War.” Perspectives on Politics 16, no. 1 (March 2018): 149–55. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592717004030.

- Furlan, Marta. “Understanding Governance by Insurgent Non-State Actors: A Multi-Dimensional Typology.” Civil Wars 22, no. 4 (2020): 478–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2020.1785725.

- Gogoi, Dilip. “Sovereignty and National Identity: The Troubled Trajectory in Northeast India.” In Unheeded Hinterland. Identity and Sovereignty in Northeast India, edited by Dilip Gogoi. New Delhi: Routledge, 2016, 3–15.

- Gokhale, Nitin A. The Hot Brew: The Assam Tea Industry’s Most Turbulent Decade, 1987–1997. Guwahati: Spectrum, 1998.

- Goswami, Namrata. “India’s Counter-Insurgency Experience: The ‘Trust and Nurture’Strategy.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 20, no. 1 (2009): 66–86.

- Goswami, Namrata. India’s Internal Security Situation: Present Realities and Future Pathways. New Delhi: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, 2013.

- Goswami, Sabita. Along the Red River: A Memoir. Delhi: Zubaan, 2014.

- Hazarika, Sanjoy. Strangers of the Mist: Tales of War and Peace from India’s Northeast. New Delhi: Penguin, 1995.

- Innes, Michael A. “Deconstructing Political Orthodoxies on Insurgent and Terrorist Sanctuaries.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 31, no. 3 (2008): 251–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10576100701879646.

- Jackson, Ashley. “Life under the Taliban Shadow Government.” Overseas Development Institute, 2018. https://cdn.odi.org/media/documents/12269.pdf.

- Kasfir, Nelson. “Rebel Governance – Constructing a Field of Inquiry: Definitions, Scope, Patterns, Order, Causes.” In Rebel Governance in Civil War, edited by Ana Arjona, Nelson Kasfir, and Zachariah Cherian Mampilly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017, 21–46.

- Khanikar, Santana. State, Violence, and Legitimacy in India. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199485550.003.0007.

- Kimura, Makiko. The Nellie Massacre of 1983: Agency of Rioters. New Delhi: SAGE, 2013.

- Korteweg, Rem. “Black Holes: On Terrorist Sanctuaries and Governmental Weakness.” Civil Wars 10, no. 1 (2008): 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698240701835482.

- Loyle, Cyanne E. “Rebel Justice during Armed Conflict.” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 10 July 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002720939299.

- Loyle, Cyanne E., Kathleen Gallagher Cunningham, Reyko Huang, and Danielle F. Jung. “New Directions in Rebel Governance Research”. Perspectives on Politics, 2021, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592721001985.

- Mahanta, Nani Gopal. Confronting the State: ULFA’s Quest for Sovereignty. New Delhi: SAGE, 2013.

- Mampilly, Zachariah. “Rebel Taxation: Between Moral and Market Economy.” In Rebel Economies: Warlords, Insurgents, Humanitarians, edited by Nicola Di Cosmo, Didier Fassin, and Clemence Pinaud. Rowman & Littlefield, 2021, 77–99

- Mampilly, Zachariah, and Megan A. Stewart. “A Typology of Rebel Political Institutional Arrangements”. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002720935642.

- Misra, Udayon. The Periphery Strikes Back: Challenges to the Nation-State in Assam and Nagaland. Shimla: Indian Institute of Advanced Study, 2000.

- Nacos, Brigitte L. Terrorism and Counterterrorism. London: Routledge, 2015.

- Nath, Sunil. “Assam: The Secessionist Insurgency and Freedom of Minds.” Faultlines 13, no. 2 (2004). http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/publication/faultlines/volume13/Article2.htm.

- Péclard, Didier, and Delphine Mechoulan. Rebel Governance and the Politics of Civil War. Bern: Swisspeace, 2015. https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/45533/ssoar-2015-peclard_et_al-Rebel_Governance_and_the_Politics.pdf?sequence=1.

- Raghuvir, A. Governor D. D. “Thakur’s Report to the President of India, 26.11.1990, reproduced in Peoples Union for Human Rights v Union of India (Gauhati High Court.” 20 March 1991).

- Rammohan, E. N. Insurgent Frontiers: Essays from the Troubled Northeast. New Delhi: India Research Press, 2005.

- Routray, Bibhu Prasad. “Terrorists in Uniform: ULFA’s Boastful Claims.” Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies (blog), 22 December 2004. http://www.ipcs.org/article/terrorism-in-northeast/terrorists-in-uniform-ulfas-boastful-claims-1591.html.

- Sack, Robert David. Human Territoriality: Its Theory and History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

- Saikia, Jaideep. “Allies in the Closet: Over-Ground Linkages and Terrorism in Assam.” Faultlines 8 (2000). http://www.satp.org/satporgtp/publication/faultlines/volume8/Article4.htm.

- Saikia, Pahi. “The Political Economy and Changing Organisational Dynamics of the ULFA Insurgency in Assam.” In Ethnic Subnationalist Insurgencies in South Asia: Identities, Interests and Challenges to State Authority, edited by Jugdep S. Chima. London: Routledge, 2015, 41–61.

- Sarma, Dipak Kumar. “Factional Politics in Assam: A Study on the Asom Gana Parishad”. IIT Guwahati, 2017. http://gyan.iitg.ernet.in/bitstream/handle/123456789/1292/TH-1788_09614110.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y.

- Schwab, Regine. “Insurgent Courts in Civil Wars: The Three Pathways of (Trans)Formation in Today’s Syria (2012–2017).” Small Wars & Insurgencies 29, no. 4 (2018): 801–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2018.1497290.

- Sharma, Chandan Kumar. “Immigration, Indigeneity and Identity: The Bangladeshi Immigration Question in Assam.” In Unheeded Hinterland. Identity and Sovereignty in Northeast India, edited by Dilip Gogoi. New Delhi: Routledge, 2016, 89–114.

- Sharma, P. D. Police and Political Order in India. New Delhi: Research Publications, 1984.

- Singh, Rajinder. The ULFA Insurgency in Assam: Superb Operations by the Bihar Regiment. Noida: Turning Point, 2018.

- Sinha, S. P. “Insurgencies in North-East India: An Appraisal.” Aakrosh 3, no. 7 (2000): 40–61.

- Spears, I., and P. Kingston, eds. “States-Within-States: Incipient Political Entities in the Post-Cold War Era.” New York: Palgrave, 2004.

- Staniland, Paul. “States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders.” Perspectives on Politics 10, no. 2 (2012): 243–64.

- Stewart, Megan A. “Civil War as State-Making: Strategic Governance in Civil War.” International Organization 72, no. 1: 205–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818317000418.

- Suykens, Bert. “Comparing Rebel Rule Through Revolution and Naturalization: Ideologies of Governance in Naxalite and Naga India.” In Rebel Governance in Civil War, edited by Ana Arjona, Nelson Kasfir, and Zachariah Cherian Mampilly, 138–58. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Thakur, Shalaka, and Rajesh Venugopal. “Parallel Governance and Political Order in Contested Territory: Evidence from the Indo-Naga Ceasefire.” Asian Security 15, no. 3 (2018): 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/14799855.2018.1455185.

- Volo, Lorraine Bayard de, and Edward Schatz. “From the Inside Out: Ethnographic Methods in Political Research.” PS: Political Science & Politics 37, no. 2 (2004): 267–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096504004214.

- Waterman, Alex. “Ceasefires and State Order-Making in Naga Northeast India.” International Peacekeeping 28, no. 3 (2021): 496–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2020.1821365.

- Waterman, Alex, and James Worrall. “Spinning Multiple Plates Under Fire: The Importance of Ordering Processes in Civil Wars.” Civil Wars 22, no. 4 (2020): 567–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/13698249.2020.1858527.

- Weiner, Myron. “The Political Demography of Assam’s Anti-Immigrant Movement.” Population and Development Review 9, no. 2 (1983): 279–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/1973053.

- Wenner, Miriam. “Trajectories of Hybrid Governance: Legitimacy, Order and Leadership in India.” Development and Change 52, no. 2 (2021): 265–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12624.

- Worrall, James. “(Re-)Emergent Orders: Understanding the Negotiation(s) of Rebel Governance.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 28, no. 4–5 (2017): 709–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2017.1322336.

- Worrall, James, and Alex Waterman. “Taxonomies of Rebel Governance: A Linnaean Approach to Understanding Shapes of Rebel Rule.” Working Paper, 2020.