ABSTRACT

Rebel governance assumes a symbiotic relationship between coercion and public goods provision. However, in the rebel-held town of Ndélé, Central African Republic, we find that governance happens in rebel-held territory, but rarely by rebels. Rebels allowed other actors to provide services for the people only when this did not hinder rebels extracting political clout and economic benefit from the people and their lands. We show how rebels’ extractive ambitions and governance discourses evolved during successive stages of rebellion through a diachronic comparison rooted in multimethod fieldwork from 2018 to 2022. We ask, why were rebel groups able to set up their rule, then rule for seven years, before ultimately losing power? Rebels evoked public goods at the onset of rebellion to justify the use of coercive means. After rebel rule was established, rebels outsourced public goods to international and state actors allowing for governance in rebel-held territory while focussing their own efforts on extraction. When their rule was challenged, rebels targeted governance actors and spaces in their territory in pursuit of economic gain and political dominance. Our findings call for a re-evaluation of existing rebel governance studies and the ways in which rebel groups are engaged with.

Introduction

In 2017, the Minister for Education of the Central African Republic sought to eradicate corruption during the grading of the baccalaureate examinations. Results obtained by students throughout the country in 2018 thus for the first time in decades more accurately reflected their actual exam performance. That year, the Ndélé secondary school obtained one of the best rates of successful graduates vis-à-vis the number of candidates sitting the examination. This prefectural capital in the country’s northeast – bordering Chad and not far from Sudan – is no ordinary town. Rebels ruled Ndélé almost undisputedly from 2012 to 2020. It seemed they brought the population relative security and an improvement in service provision, symbolized by the surprising success rate that baccalaureate candidates enjoyed.

It is tempting to argue that the success of rebel rule in Ndélé stems from a mixture of non-state coercion and service provision, or as one growing research trend terms it from the creation of rebel governance. At the onset of rebellion in Ndélé, rebels indeed used public goods provision as a narrative to legitimize taking up arms. However, during rebel rule such services were outsourced to state and international actors. Rebels meanwhile focussed on increasing economic and political influence. We argue that rebel governance and rebel extraction are two distinct forms of ordering and thereby take issue with the literature that often confounds rulemaking for the people with that which gains from the people but for the rulers only. Through a slight – but key – change to common definitions,Footnote1 we see rebel governance where non-state armed groups provide public goods or organize decision-making processes in a way that is appreciated – and thereby legitimized – by at least a significant part of the population they rule over. Rebel extraction on the other hand is the enrichment of a small circle of non-state armed group members through physical and structural coercion, to which most of the populace is opposed. We thus argue that the reactions and opinions of the populace vis-à-vis non-state armed actors are key to understanding the legitimacy of forms of ordering beyond the state (see introduction to this special issue).Footnote2

The alleged success of rebel governance in Ndélé is partly a methodological artefact that arises when looking only at certain outcome indicators – such as baccalaureate numbers. It is also a product of heightened interest by the international community and the state in the rebel-held town following the onset of rebellion. It is not due to rebel service provision. In fact, when rebel infighting began in 2020, services ground to a halt as administrators and humanitarians were intimidated by armed factions and evacuated. Finally, the population saw its own vote of no confidence and abandoned Ndélé. We investigate how the security and public goods sectors were split between different actors, creating a governance cycle (see introduction to this special issue)Footnote3 that contributed to the establishment and duration of rebel domination in Ndélé. By studying the responses of those the rebels ruled over, we find the town to be an example of non-state ordering under the guise of alleged rebel governance at the onset of and then during their rule. When the latter was challenged, however, they showed their true priority in pursuing rebel extraction.

A variety of terms describe the management of public affairs in spaces not dominated by an omnipotent central state: hybrid orders,Footnote4 informal institutions,Footnote5 public authority,Footnote6 security arena,Footnote7 and – more contested – fragile states.Footnote8 These approaches have in common that they investigate the creation and operation of public affairs, doing so by not focussing their attention on the state alone but by opening up the field of study to non-state players too.Footnote9 Within this wider literature of multi-actor ordering, a subset emphasizes the rule of an armed group that opposes the state’s claim to a monopoly on the use of force: rebels. Prominent studies have focussed on the origins of rebellion. Ted Robert Gurr claimed, for instance, that relative deprivation – that is, a discrepancy between what ought to be and the actual state of what is – breeds rebellion.Footnote10 Scott Gates delved further into why people join rebellion, finding geographic, ethnic, and ideological proximity to be the main causes.Footnote11 With the growing sophistication of quantitative analysis, the onset of civil war became a key interest here. Lars-Erik Cederman, Andreas Wimmer, and Brian Min concluded through large-N regression models that excluded groups, especially those with high mobilizational capacity and conflict experience, are the most likely to rebel.Footnote12 We critically evaluate how these prior findings aptly describe certain developments at the start of rebellion in Ndélé. However, relative deprivation, proximity, and exclusion mostly explain legitimation narratives rather than underlying practices.

The more recent literature has shifted focus from rebellion’s onset to the political ordering of it. The most popular term became rebel governance: non-state actors who militarily oppose the state, create rules, and provide for social, political, as well as economic goods.Footnote13 Most rebel governance literature concentrates on the production of security, since the essence of rebellion is a contestation of the monopoly on the use of force wielded by the state.Footnote14 The impact of rebel groups on the creation and changes to public order is often accidental and indirect.Footnote15 Ana Arjona distinguished between armed groups engaging deeply in civilian affairs, which she termed ‘rebelocracy’, and those with a minimalist approach, an ‘aliocracy’. According to her, how much a rebel group intervenes in local affairs depends on their time horizon and on pre-existing local institutions.Footnote16 Her work explained why local rebel actors with a claim to autochthony preferred involvement, or at least the enabling of civilian affairs, while the more distant overall leadership with no direct connection to pre-existing institutions instead favoured a minimalist approach.

However, such differentiations by degree of involvement overlook the key distinction between governance by rebel actors and governance in rebel territory. Ndélé’s rebels’ surprisingly long rule can be explained more by substitution via state and international actors than by the former’s own management of civilian affairs. Other actors’ accidental, unwanted prolongation of rebel rule leads us to re-read with a more critical eye some of the literature that too readily sees symbiotic relations existing between international, state, and non-state actors in service provision.Footnote17 Non-state delivery of goods was argued to be potentially just as viable as state delivery.Footnote18 One author found a relatively efficient substitution of health provision in Somalia by international stakeholders,Footnote19 while further observers, however, warned of the negative effects of too much substitution within the framework of international trusteeships.Footnote20 The viewpoint of the affected population is lacking in these studies: it is they who ultimately decide whose rule is considered legitimate, for instance due to service provision being welcomed, and whose is simply endured for fear of reprisal.

Three types of services were observable in Ndélé: health, education, and public-infrastructure construction. We excluded the latter given its limited relevance to interpersonal negotiations in terms of daily service provision. Health could have been a highly intriguing avenue of inquiry, because Ndélé had a well-functioning hospital supported by an international non-governmental organization treating both rebels and their victims. Rebels even went as far as guarding the hospital entrance through two soldiers wearing an ‘MP’ (abbreviation for ‘Military Police’) armband. However, studying health services might consequently have been too contentious of an issue. We chose, then, education due to the prior expertise of author two and given the alleged education success story of Ndélé that caught the interest of stakeholders in Bangui – thus calling for closer examination.

Scholars consider a population rich in young people but poor in education levels fertile ground for conflict.Footnote21 Studies also describe education as a factor providing countries at war with a way out of cycles of violence.Footnote22 However, when the nature of education becomes politicized during conflict it can become a bone of contention between warring parties: as in the case of Afghanistan.Footnote23 Intriguingly, education in CAR has not been politicized to date. The rebels in question want children to respect their teachers and be taught within the national education system.Footnote24 Studying Ndélé thus provides a unique opportunity to understand shared governance of education between the rebels and the state.

We selected Ndélé as a typical caseFootnote25 of rebel governance because it features a lengthy period of control by a non-state armed group and the the absence of state armed forces, as well as being an instance of rebel involvement in creating public rules. While multiple areas of CAR saw rebel control, few witnessed it so undisputedly over a number of years. The goal of in-depth research of such a singular case is to draw general results that can be applied to other regions elsewhere.Footnote26 The ongoing conflict in CAR and the politically contested nature of rebel rule in Ndélé meant we had to limit our immersion in the field to ensure our own, our colleagues, and our respondents’ safety.Footnote27 We used site-intensive methods inspired by Anthropology and applied to Political Studies.Footnote28 Importantly, we always sought to speak with respondents where they felt most at ease, never pressed them to speak about a topic they felt uncomfortable with, and ensured strict data anonymity. Data validity nevertheless remained high, since people spoke with surprising frankness. Also, our abstract questions, such as on the education system and the social contract, led to elaborate responses on the roles of different actors in political ordering even if we avoided discussing specific abuses – which could have put participants at risk. Rather, detailed knowledge of events and abuses were gathered from expert interviews with international stakeholders in Bangui and remotely, as well as from in-depth reports. Our collaborative approach allowed each of us to reflect on our positionalities and combine these perspectives: Author one is a long-term observer of political developments in the country, but as a white male from Europe lacks many inherent understandings and access to the more intimate aspects of CAR society. Author two had a similar constraint, but as a woman and education expert she more easily engaged with teachers, parents, and pupils. The honorary co-author, Igor Calvin Acko, a Central African peace and conflict expert, was a crucial facilitator of our fieldwork and led the way in developing our understanding of societal drivers of peace and conflict in Ndélé and CAR more generally. His untimely demise hindered him from co-writing this article. A local journalist and another Central African peace and conflict researcher opened further doors and drove the topics we would discuss.Footnote29

To examine the period prior to rebel ascension in late 2012, we analysed interviews with local inhabitants present before that critical juncture as well as relevant both primary and secondary reports. During our first fieldwork phase, from June to July 2018, we divided our two-month stay between the capital and Ndélé, conducting 28 interviews, several focus group discussions, while also studying a wide range of primary documents too. From January to June 2019 we conducted three short research stays, which included interviews with 32 stakeholders in the capital Bangui and Ndélé as well as open questionnaires with 60 inhabitants in and around Ndélé within a larger research project that also included three other localities.Footnote30 Finally, we followed up with some of our previous interview partners (partly remotely) between October 2020 and March 2021 so as to analyse the demise of rebel rule in 2020. Based on this data, we used process tracing and hermeneutic analysis to study how Ndélé’s education and security sectors were governed.Footnote31 We seek to understand why rebel groups were able first to establish their rule, why they were able to maintain it for seven years, and why they ultimately fell from power.

1) Rebel governance arises amidst civil war (2012–2013)

Ndélé with its 20,000 inhabitants has been at the epicentre of political dynamics for centuries. It hosts a sultanate that was involved in slave raids in the 19th century, which reverberates in today’s prejudices among southern and western population groups in CAR against northern groups of Arab descent.Footnote32 This sultanate also defied rule by the French colonial regime and effectively continued a parallel government on its own terms into the early 20th century.Footnote33 People in the region are thus accustomed to self-rule and have only a brief history of political integration with what was to become the Central African Republic. This remained unchanged after CAR’s independence as governments focussed on developing the capital and western parts of the country. People in Ndélé related through trade to their own nation’s capital and not less importantly to bordering Chad and Sudan. Poaching, as well as the diamond, cattle, and gold trades became major activities and increasingly militarized as international and state actors securitized these domains.Footnote34 The government neglected the area at large, only keeping a token presence in town while leaving the lucrative economic activities taking place in rural areas – gold, diamonds, cattle, and poaching – to non-state armed actors. In the early years of the 21st century, two armed groups roughly composed of the Rounga and Goula ethnic groups respectively engaged in armed combat over the sourcing and trade of diamonds and gold. Strongly confirming the prominent theses of rebel scholarship, prior conflict experience was a key factor here.Footnote35 The rebel groups counted among their ranks mercenaries from neighbouring Chad and Sudan, including some formerly hired by François Bozizé when he took power in 2003 but who were disgruntled when they did not receive their promised rewards.

In seeming support of the exclusion and relative deprivation theories of rebellion, President Bozizé marginalized the region economically and politically, attempting a coordinated military campaign with France in 2008 purely to gain access to resources controlled by the armed groups.Footnote36 Unrelated to this, Chad and Sudan – who had previously supported opposing armed factions in CAR – signed a peace agreement in 2010. These two developments taken together meant rebel factions no longer had opposing external backers while gaining the common goal of toppling a president who undermined their combined economic interests.Footnote37 In late 2012, several rebel groups joined under the name of Seleka (‘Coalition’ in the Sango language) and took control of Ndélé as their first strategic conquest in the country.Footnote38

The rebel alliance succeeded in occupying towns in the region, where new recruits joined them for opportunistic reasons despite scant ‘proximity’ to the original rebel forces,Footnote39 before continuing to the capital, Bangui, in March 2013. They then wrested power from the autocratic Bozizé and installed a new government headed by the rebel president Michel Djotodia. In their public speeches and open letters, the rebel alliance claimed to be seeking the political integration of CAR’s marginalized people and the greater development of their home region. Rebels did not corroborate this narrated legitimation strategy through improvements in governance.Footnote40 On the contrary, the rebel government committed atrocities against the population.Footnote41 After six months in power, Djotodia stepped down after facing international pressure. Entrenched mostly in the northeast region after their defeat, one rebel faction of the former rebel alliance renamed itself Front populaire pour la renaissance de la Centrafrique (hereafter, FPRC). They controlled a territory extending hundreds of kilometres from Kaga-Bandoro to Birao, with Ndélé at the centre, claiming to be fighting for the region’s development and to end its marginalization. A powerful message, since the CAR as a whole ranks as the second least developed country in the world according to the Human Development Index 2020 – including an exceptionally low score on education.

State-supplied public goods were minimal in Ndélé. For instance, the entire prefecture had only one high school (lycée). We gained first-hand information on that institution’s functioning in 2018, when the rebels had already ruled the town for six years and asked respondents to describe the changes having occurred since 2012. While respondents detailed many deficiencies in the education sector, most were present before rebels took over. The principal contribution of the state to education in the northeast region is the provision of human resources. The government in Bangui pays and deploys teachers as well as inspectors and trainers via the regional teacher-training centre in Ndélé.Footnote42 However, most of the teachers appointed to Ndélé do not take up their posts. In 2018, appointees expressed fear of the rebels as the main reason to abstain from assuming their post or leave it early. However, even before the current crisis, teachers frequently refused to take up their post in Ndélé because of its isolation.Footnote43 The 650 km journey from the capital has long been full of danger due to bandits known as ‘coupeurs de route’.Footnote44 Roadblocks make each trip costly.Footnote45 Added to the costs of moving to Ndélé is the loss of supplementary income available through teaching at Bangui’s private schools or private tutoring. Even if the Ministry of Education’s official position is that teachers who do not assume their posts will be suspended from the national education system this punishment is rarely enforced. Teachers appointed to Ndélé feel little pressure to follow through. Further, under Bozizé’s rule and before under President Ange-Félix Patassé, salaries going unpaid for months or even years was commonplace for state employees. The situation was comparable in other public-service domains too, such as health, infrastructure, and general administration.

In their declarations, the FPRC rebels claimed to be in favour of education. The general coordinator of the armed group in Ndélé said they supported education and protected teachers.Footnote46 The origins of this affirmation of support lie in the founding principles of the rebellion, as based on the defence of the marginalized northeastern region’s interests.Footnote47 This narrative contrasts with Seleka factions pillaging institutions that provided public services and chasing away state employees: The secondary school and the teacher-training centre were looted during the onset of rebellion, and all their equipment was stolen.Footnote48 One could attribute this violent beginning to the vagaries of changing orders during political upheaval and expect the ruling group to install services when things calm down eventually. We turn, therefore, to extraction and governance, with rebels demonstrating their hegemony in Ndélé over a longer period of time.

2) Prolonged rebel rule over Ndélé (2013–2020)

While state weakness allowed for rebels’ swift ascension to power, the latter’s rule lasting seven years is harder to explain. In terms of coercion, they faced opposition from a resourceful peacekeeping mission as of 2014 and an internationally re-trained state army as of 2019. Additionally, the population, it seems, would have to be kept appeased through the provision of public goods. The rebels focussed entirely on dominating the security sector, pushing back international and state actors here. On the other hand, they allowed state and international actors to become involved in service provision as long as this did not impede the rebels’ extractive ambitions. These ambitions are twofold: controlling trade routes and recognition as political leaders respectively. Economic aims are achieved through controlling diamond and gold trading routes as well as cattle trails; the amount of wealth that leaders and lower-ranking soldiers can accumulate through this is not vast in global terms but must be seen in the context of a highly impoverished local population. Politically, leadership is gained through controlling militias, which leads to involvement in peace agreements and potentially official government posts. This is thus key to understanding why the rebels sought to dominate the security sector so as to achieve these extractive aims, while other actors were willing to substitute for the former’s lack of service provision – not to mention how this influenced the duration of their rule as well as behaviour during it.

The FPRC’s level of resources, organizational capacity, and armament make it one of the strongest non-state armed groups in CAR. Nevertheless, the peacekeeping mission and the national state army became increasingly powerful rivals. Some form of peacekeeping mission had been present in CAR since the late 1990s. Early in the new millennium, the regional intervention force focussed particularly on CAR’s northeast to mitigate spill-over effects from Chad and Sudan – thus on the same region the FPRC later controlled. The mission was, however, exceedingly modest, with just a few hundred soldiers, not being well-resourced until civil war broke out in 2012. Thereafter, first the African Union took over the mission, scaling it up to a few thousand soldiers. By late 2014, the mission transferred to United Nations tutelage, who increased it to 12,000 soldiers under the name of the Mission multidimensionnelle intégrée des Nations unies pour la stabilisation en Centrafrique (MINUSCA). Of these peacekeepers, only approximately one hundred are permanently based in Ndélé. The UN peacekeeping mission is stronger in all military categories: they are more highly resourced, they have better military equipment, functioning logistical supply networks, and see the regular rotation of troops. While there are no exact estimates of the FPRC’s size, and they claim themselves to have tens of thousands of fighters; a more realistic estimate by a high-ranking UN source spoke of at most 3,000 rebels in total.Footnote49 From the perspective of sheer force, the UN peacekeeping mission would thus be able to defeat the FPRC armed group easily.

While a peacekeeping force is meant to act with restraint wherever possible, MINUSCA is mandated to protect the population, extend state authority, and enforce the peace agreement of 2019.Footnote50 The FPRC has attacked some members of the local population, hindered most state personnel from returning to Ndélé, and frequently violated the terms of the peace agreement. Thus, the mandate would enable MINUSCA to engage the FPRC with force. Strategic considerations explain some of the hesitancy to do so: the FPRC is not CAR’s only armed group and forcefully pushing back all armed actors in the country would strain even the relatively high capabilities of MINUSCA. Also, the contingents present in CAR are not only dependent on the UN hierarchy but also their sending countries, who hesitate to risk their soldiers’ lives by getting more involved than they absolutely must. The likely costs of wresting back control from the rebels largely explain why peacekeeping forces have left the FPRC to reign freely in Ndélé. Another answer hereto lies in believing they can make rebels partners in peace agreements and developmental projects.

This international stance is based on assumed rebel governance – that is, the presence of the non-state armed group has some benefit for the local population compared to the costs of dislodging them in the form of casualties, displacement, and a void of authority. The rebel governance discourse has three aspects to it: first, their assumed autochthony, granting them popular legitimacy. Second, within the FPRC’s territory there were relatively few incidents of insecurity when compared to more contested parts of the country. Third, some public goods such as health, education, and youth activities are available in Ndélé and its surroundings. We will discuss how these three aspects come together and how the local population itself views these alleged assets.

Autochthony

The story of an indigenous rebellion is convincing at first glance. When we met the general coordinator of the FPRC at his headquarters in Ndélé, he wore a t-shirt, jogging pants, and flip-flops. We sat on wooden chairs under a mango tree. He pointed at the small hut next to him, which was the town’s FPRC headquarters, and said: ‘that is my house’. Then he pointed to a slightly larger compound opposite him and said: ‘that is my father’s’. Finally, pointing into the distance slightly, he stated: ‘and my grandfather lived just over there’.Footnote51 A handful of men sat around him, most in civilian clothing, some with weapons, four in military fatigues, of which two were the town’s ‘gendarmerie’ and the other two ‘military police’. The members of the FPRC permanently stationed in Ndélé mostly sit by idly, live off local revenue generation, and are themselves dependent on local services to get food at the market or send their children to school.

Among the larger rebel group, the level of autochthony is more contentious. While one of the two main FPRC leaders was born in Ndélé, he has since used the armed group to amass massive wealth without funnelling it back into his home community.Footnote52 The other main FPRC leader similarly continues to claim to be fighting to ‘develop the country and lift Central Africans out of poverty and precariousness’,Footnote53 but forms changing opportunistic alliances to gain economic influence and political power. Of 60 inhabitants randomly selected for structured qualitative questionnaires in and around Ndélé, only a handful expressed confidence in the rebels.Footnote54 Alleged autochthony thus does not automatically lead to legitimacy. On the contrary, statements like this one by a male barber were more commonFootnote55:

Let them no longer allow themselves to be enlisted by the rebels to turn against us. We were one family. We were walking together when they were the first to kill us.

Security

Security is the main good that rebels claim to bring to the local population. Indeed, from 2014 to 2019 the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (hereafter, ACLED) dataFootnote56 on Bamingui-Bangoran, the prefecture Ndélé is the capital of, depicts lower rates of violence when compared to CAR’s conflict hotspots but higher ones when compared to the western regions that the Seleka rebels barely reached. The easiest explanation for this difference is that Ndélé was for a long time at the centre of FPRC control, while the heaviest fighting took place where claims of control overlapped between different armed non-state groups or with the state.

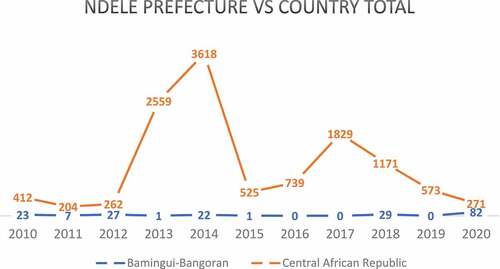

This first graph shows that Bamingui-Bangoran (the prefecture of which Ndélé is the capital) was a relatively fought over region before the onset of nationwide rebellion, accounting for about 1/20 of conflict-related deaths in CAR in 2010 and 2011, and more than 1/10 in 2012 (while accounting for an estimated 1/100 of the country’s population). Thereafter, however, when the FPRC was clearly in control (as of 2013) the prefecture accounted for few conflict-related deaths, at times even none, as all the while the civil war caused hundreds or even thousands of deaths a year countrywide. Finally, when the FPRC fell from power in 2020, Bamingui-Bangoran saw the most deaths of any prefecture, accounting for more than 1/4 of CAR’s overall fatalities due to conflict.

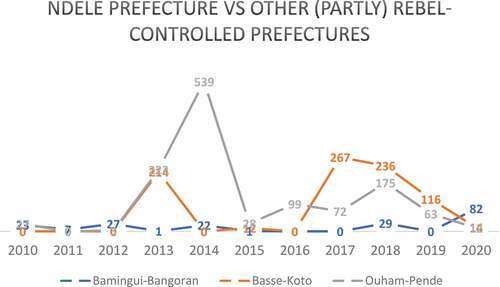

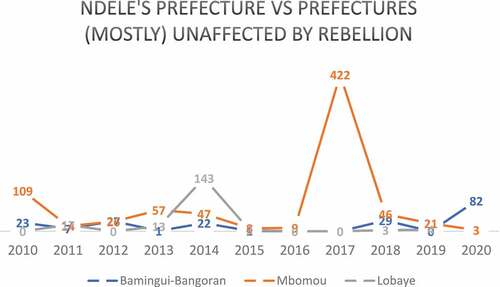

Commonly, civil wars do not engulf entire countries at a time. It is thus also intriguing to look at the prefectural level and see the numbers in comparison to other (at least partly) rebel-controlled areas and those mostly unaffected by the Seleka rebellion. The following prefectures were selected because we also studied them qualitatively during certain instances throughout the observation period. Thus we can better contextualize ACLED’s raw numbers.Footnote57

The second graph shows that violence in Basse-Kotto spiked in 2013 because the rebellion moved from the far northeast (including Ndélé) to the country’s central provinces and on to the capital. Afterwards Basse-Kotto was quite incontestably rebel-controlled (lull in violence from 2014 to 2016) before becoming the epicentre of violence between non-state armed group factions from 2017 to 2019, who were then mostly expelled by peacekeepers in 2020. Ouham-Pendé saw multiple armed groups compete for control of trade routes, political clout, and economic benefits with varying degrees of intensity until peacekeepers took a tougher stance against them beginning in 2019. Bamingui-Bangoran was comparatively calm during this period.

The third graph shows that the level of violence in Ndélé’s prefecture resembled more that in those mostly unaffected by rebellion, such as Lobaye and Mbomou. Even more, the latter two saw greater spikes in violence, as brought about by non-state but also non-rebel armed factions (colloquially labelled ‘Anti-Balaka’)Footnote58 – which Ndélé did not have. Intriguingly, when violence subdued in all other prefectures (see ) in 2020, it peaked in Bamingui-Bangoran (more on the reasons why below).

Figure 2. Violent-event deaths in Bamingui-Bangoran in comparison to Basse-Kotto and Ouham-Pende prefectures, that are considered conflict hotspots and which witnessed the presence of non-state armed groups; source: ACLED (2021).

Figure 3. Violent-event deaths in Bamingui-Bangoran in comparison to Mbomou and Lobaye prefectures, that are considered mostly unaffected by conflict and most of the time did not witness the presence of an organized non-state armed group; source: ACLED (2021).

However, ACLED only measures conflict incidents and not whether security is subjectively perceived as (a) ‘good’. Subjective insights from interviews with the local populace in 2019 – and thus during a lull in violence – point to a discrepancy between few recorded incidences of insecurity and simultaneously high levels of security frustration in Ndélé.Footnote59 For instance, a female shopkeeper responding to our questionnaire in 2019, rather than attributing security provision to the rebels – in a year when ACLED recorded no conflict-related deaths in Ndélé (!) – called them the root cause of her (felt) insecurityFootnote60:

Creating security and justice in this city can be the ideal once the DDR [Disarmament Demobilization and Reintegration] programme has been implemented and solutions are found for the rebel groups who are the root cause of our local security problem.

Rebels are to be considered the ‘root cause of [the] local security problem’ because they dominate the security sector, doing so not first and foremost to provide safety to inhabitants but rather to control the means of extraction. Our data does not tell us much about the reasons for such rebel behaviour. Rather, we focus on the ramifications for the local populace – from whom we have ample insights – and on the political order such rebel extraction foments. Rebels focus economic activity on extraction and the movement (not the production) of goods, which means they have no stake in the well-being of the local economy via direct investment therein. Abundant resources in a certain area are recurrently used as an explicator of violent rebel behaviour,Footnote61 whereas the Ndélé example shows that the movement through rebel-held territory can also be a key economic activity.Footnote62 Moving goods is dependent on safe passage, which remains the exclusive prerogative of the rebel group. Diamonds, gold, and cattle are taxed heavily even though they are not consumed within the rebel group’s territory, and often not originally extracted there either.

During our visit to Ndélé in 2018 only a few dozen rebels were visibly present from a movement claiming to have thousands of (armed) members. Ndélé had lost its relevance to rebel groups as they conquered politically and economically more relevant hubs elsewhere. Rebels thus made the choice to position the brunt of their forces closer to extraction opportunities such as mining sites around Bria and politically contentious towns, such as Kaga Bandoro. The few rebels remaining in Ndélé gained modest revenues by taxing local traders and the trucks bringing goods to town for sale. For instance, each artisanal miner must pay a mining tax of CFA 10,000 to 25,000 (EUR 15–40),Footnote63 each discharged truck an offloading fee of around CFA 50,000 (EUR 75), and each shop a tax of CFA 1,000 (EUR 1.5).Footnote64

The rebels focus their activities on security, but in doing so they are responsible for creating a safe environment for other public goods to function – such as education. Indeed, security is indispensable for education in the CAR, where many schools only function intermittently as they are in zones of recurrent combat. Schools in Bangassou (Mbomou prefecture), for instance, were unable to let students sit their baccalaureate examinations in June 2017 and 2018 at the same time as other regions of the country. Candidates had to wait until calm was restored before being able to catch up with their lessons and take their examinations.Footnote65 In contrast, Ndélé’s secondary school – located in the heart of rebel territory in a zone under their full control and far from the borders of state-controlled regions – does not suffer directly from the insecurity caused by armed conflict. Each year, students were able to start their semester on time and continue without interruption through their final examinations.

Nevertheless, the security guaranteed by the rebels’ presence should be qualified. In 2018, there were clashes in Ndélé between two ex-Seleka rebel factions: the FPRC in town and a new grouping claiming to be close to the so-called Mouvement Patriotique pour la Centrafrique, which includes many Chadian militias. They exchanged gunfire during the baccalaureate examination period in June. Even if the rebels claim that they tried to reassure students of their safety, being so close to fighting and the almost 30 recorded deaths had a detrimental effect on candidates’ concentration and exam performance.Footnote66

Governance exemplified through education

In Ndélé, there is no public-service provision apart from education and health. The state supplies the necessary human resources within the education sector: teachers, school inspectors, trainers, and the few officials who take up their appointments in the northeast region must live alongside the rebels. The rebels accept the presence of education officials and do not envisage checking the ideological content of their teachings.

However, the rebels do not organize any educational or related activities. The local taxes rebels gather from the markets and from trucks crossing the country from Chad and Sudan are not spent on the education sector. They bar the presence of state officials representing the Ministry of Finance, with whom responsibility for funding the operations of educational establishments semester by semester regularly lies. The rebel-governance literature typically asks what the interest of armed groups is in taking up governance provision.Footnote67 Given the stated mission of decreasing the marginalization of CAR’s northeastern peripheries, the FPRC would likely have faced massive opposition had it refrained from investing its significant resources into means of development such as education and further restricted the functioning of an already low level of state-provided formal instruction. We thus turn the typical rebel-governance question upside down and ask why Ndélé’s rebel group was able to forego governance provision without this deliberate negligence undermining their overall rule. The answer needs a thick description of how governance – exemplified by the education sector – could function in rebel-held territory in a highly dysfunctional manner, without this shortcoming being attributed to the rebels per se.

Teachers find it difficult to do their jobs as the secondary school receives no material resources from the state. The school administration must use a 1970s typewriter to draw up the official documents for the institution, while filling in by hand school reports and attendance registers. The state has not replaced any of the looted resources. As rebels occupy the region, the secondary school receives no operating credit. The institution only survives due to the CFA 1,500 (about EUR 2) paid by each student at the beginning of the school year. A substantial proportion of students work on top of their studies. Thus, instead of following six days of classes they can often only attend two or three days a week. The repeated absences prevent them from achieving the necessary grades to pass the baccalaureate, explaining the high rate of repeated years and of school dropouts, accounting for around 2/3s of students in each year.

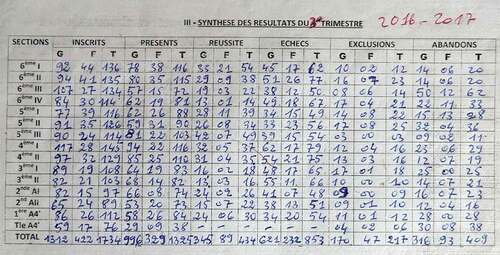

Figures from the local handwritten school registry (see ) show that while for the academic year 2016/2017 some 519 students registered for Year Six (sum of rows ‘6ème’ [first year of secondary school], column ‘Inscrits, T’ [total number of registered students]), the first year of secondary education, only 76 did so for the final year (row ‘Tle A4’’ [terminale, last school year], column ‘Inscrits, T’). For girls, the numbers are even worse: while 142 registered for Year Six only 17 did so for Year Twelve (same rows, column ‘Inscrits, F’ [total number of registered girls]). Of the 76 students making up Year Twelve, only 40 sat the baccalaureate exam that concludes high school – of which finally a ‘high’ 80% succeeded. In other words, less than one in ten students starting high school sits the final exam. The situation is similarly bad in other regions: In Bangassou (Mbomou prefecture), for instance, 1,309 students signed up for the first class of secondary school (6ème) in the 2017/2018 academic year but only 203 did so for the last class.Footnote68 Looking at overall student numbers and talking to academic staff in Ndélé and Bangassou thus calls into question the idea of terming education provision in Ndélé a success story.

Figure 4. Student overview of ndélé secondary school in the final trimester of the school year 2016/2017; source: office du proviseur du lycée de Ndélé (2018).

Despite the personal hardship, some national education officials nevertheless do move up to the country’s northeast region. Only one teacher who had taken up his post in Ndélé’s secondary school for the 2017/2018 academic year had been fond of this appointment. As a Muslim, he was living with his wife and young daughter in the PK5 neighbourhood in Bangui – an area well-known for being unsafe. He was therefore happy to be appointed to the northeast, a region where the majority of people are Muslim and where he felt he would be less anxious than he had been in the capital. Other teachers are driven by another form of opportunism: namely, the hope of promotion. While Ndélé has only two regular teachers, another around 15 have been promoted to the level of teacher-trainer. But since there are no other teachers to train, they spend most of their time teaching at the secondary school like regular teachers. For most education staff this economic and career opportunity was the primary motivation in assuming their posts.

International agencies fill the funding gap in terms of educational needs and try to function as a bridge between the two opposing players and systems. The state and the rebels both outsource, in part, the development of education in Ndélé to these international agencies. The latter construct school buildings and provide equipment and furniture. In 2018, the Norwegian Refugee Council (hereafter, NRC) was the only agency to build and renovate primary schools in the region’s villages. There is a monthly meeting during which teachers, administrators, and civil society representatives present a list of grievances to the (I)NGO representatives also in attendance. In June 2018, for example, they were asking for the construction of more wells so that children could have access to drinking water near the school.

Governance in rebel-held territory by other actors has its advantages for rebel groups as compared to governance by rebel groups themselves. Given the revenue-scarce context that is CAR, any local authority is destined to face criticism due to the perceived inadequacy of the public services provided. Rebels would thus have not been able to provide significantly improved services themselves, and even well-funded international actors are not able to wholly fulfil popular demands. Governance in their territory rather than by rebels directly thus redirected inevitable criticism about current services to the actors providing them.

3) Rebels’ fall from power (2020–2021)

Ndélé’s rebel group fell from power in 2020 as a result of their violent disintegration. This process tore down the façade of rebel governance to reveal a system rooted rather in extraction: governance provision in this rebel-held territory received no significant structural support or investment from rebel groups. International actors were able to provide governance in Ndélé due to an absence of fighting and as long as doing so left rebels’ power unchallenged. It is tempting to argue that the absence of fighting over a prolonged period is a service provided by the rebel group in Ndélé and thereby qualifies as governance. And, indeed, while fighting is absent it might seem that the provision of security to the local populace represents a by-product of rebel rule in the area. The diachronic approach taken in this article, however, allows the researcher to study the counterfactual evidence at hand: namely, whether Ndélé’s rebels also provided security when doing so incurred costs to their own economic and political interests.

The FPRC, as an umbrella group that brought together former enemies, began disintegrating when a new alliance of three smaller rebel groups challenged their monopoly on cross-border trading and smuggling routes northeast of Ndélé. These three rebel groups targeted a void of authority left by the rebel leadership increasingly focussing on arenas far from Ndélé and Birao, where more lucrative economic and political benefits were at stake. The new groups tried to gain an advantage vis-à-vis the powerful FPRC by mobilizing fighters along ethnic lines, including from among the Goula – who form a key part of the FPRC.Footnote69 As MINUSCA defended Birao and its civilian population against the FPRC’s attack launched to recapture the town between 13 and 16 February 2020, the entente between the FPRC and MINUSCA ended. The FPRC did not relinquish control of these peripheral regions because they cover important illicit-trading routes, even though they do not hold significant resources themselves. Also, losing such large swathes of territory – even if scarcely populated – significantly undermined their position as one of the most powerful rebel groups in political negotiations. The FPRC thus published a communiqué on 16 February 2020 declaring that MINUSCA was now considered an enemy for their taking of sides with the smaller rebel coalition in Birao.Footnote70 On 6 March, a MINUSCA staff member was killed near the FPRC base in downtown Ndélé.Footnote71

Goula members of the formerly interethnic FPRC tried to gain a political advantage by splintering away from the dominant group, led by Nourreddine Adam, as early as 2019. On 11 March 2020, some members from this new three-group alliance attacked Ndélé. Observers from the UN Panel of Experts argued that the attackers’ ‘leadership hoped to claim control over the three prefectures of the north-east to secure political gains after the elections, in particular the appointment of a Goula prime minister’.Footnote72 During this attack even the hospital was targeted, with 16 of the 27 people killed being civilians. A few weeks later, on 29 April, the FRPC-Goula faction targeted again people in Ndélé’s main market, killing a further 21 civilians.Footnote73

Already during the March attack, many civilians would seek shelter near the MINUSCA base to flee the fighting between warring FPRC factions. However, they were compelled by armed elements of the FPRC-Rounga to return to their homes on multiple occasions, with these combatants even hindering humanitarian actors from providing basic goods to those seeking shelter near the MINUSCA base. While the armed elements made no official statement on these actions, we can interpret the visible displacement as having challenged their claim to legitimacy based on protecting civilians. Leaving Ndélé was a civilian vote of no confidence regarding the FPRC’s ability to protect them, and even more a form of resistance against the increasing harassment by FPRC-Rounga elements. Rather than simply returning home at gunpoint, many civilians fled even further afield out of Ndélé – leaving the town largely depopulated. Whereas in February 2020 there were no internally displaced sites,Footnote74 by May of the same year more than 16,000 people had sought shelter in locations around Ndélé – which previously had had an estimated town population of around 20,000 people.Footnote75

The disintegration of the FPRC was not simply a matter of a breakdown in relations between different ethnic groups but also between the overall leadership – most notably Adam and Abdoulaye Hissène – and the local elements with a more legitimate claim to autochthony in Ndélé. The local general coordinator, who could claim to have roots in the local community of Ndélé, published a scathing letter against the FPRC leadership on May 3: he not only broke rank from the leadership of Adam and Hissène, whom he held responsible most notably for the attack on civilians on 29 April 2020, but even requested state security forces to return and inhabitants to welcome them as well as more international humanitarian assistance.Footnote76 This statement shows the diametrically different appreciations of the role of state and international actors existing between the local and overall FPRC leaderships. In a statement by Adam on 16 February, the local population was called on to revolt (or rather it was assumed they would) against MINUSCA in pursuit of liberation by the FPRC from dissenting factionsFootnote77 – an assumption that clearly contrasted with the reality of many people seeking shelter at the MINUSCA base from FPRC violence.

Other actors were pulled into the confrontation between disintegrating FPRC factions when assumed to be siding with an enemy movement. Armed factions threatened actors providing services and safety to the local populace when it was felt their practices undermined rebels’ economic and political interests. For instance, the prefecture was threatened (and evacuated), MINUSCA’s movement was barred, and the sultan’s compound attacked.Footnote78 Moreover, humanitarians suffered increased attacks and harassment while their compounds were increasingly looted after the FPRC accused MINUSCA of taking sides in their attack on Birao in February.Footnote79 By 10 May, all INGOs present in Ndélé had decided to halt their operations and evacuate.Footnote80 Two days later, the army deployed to Ndélé for the first time since 2012 and expelled the rebels.Footnote81 Thereafter, relative calm returned to Ndélé; in August an agreement between the warring factions was signed, but elements outside Ndélé town did not adhere to it. Furthermore, state security forces together with Russian mercenaries themselves harassed the local population and were thus not fulfilling people’s prior expectations of the return of a benevolent state.Footnote82

The answer to the question raised above – Do rebels allow security and governance to be provided when doing so is against their own political and economic interests? – is thus no. When their rule was contested, Ndélé’s disintegrating rebel factions used violence against civilians and humanitarian actors to try to uphold it. Ndélé’s local population thus never witnessed security provided by rebels, but rather the absence of fighting in rebel-held territory due to a lack of contestation of their rule by other armed actors – including the military, peacekeepers, and other non-state armed groups. Rebels extracted benefit economically from goods that moved through Ndélé and politically via control over the marginalized local population, granting them the status of being their representatives in government and peace deals. When these extractive interests were challenged, their governance discourse crumbled in the face of a recourse to blatant and indiscriminate violence to gain more immediate economic benefit through looting; the also sought (unsuccessfully) to restore political influence by forcing the local populace to return to their homes.

Conclusion

We argued that the rebel groups of Ndélé never set up a functioning public goods sector themselves. They used governance as a legitimization strategy at the onset of rebellion but provided no improvements in public services when taking over power. Worse even, they looted the institutions providing those services previously and committed atrocities against the local population. The narrative of defending a marginalized region thus contrasts with Seleka factions pillaging and chasing away state employees, including in Ndélé.

While the national rebel government was short-lived, Ndélé witnessed seven years of rebel dominance. Some services indeed were provided in Ndélé, such as a hospital, and as we showed in more detail a moderately successful secondary school. Rebel rule endured for so long in Ndélé because of discourses of autochthony, security, and governance provision. The local rebel leadership’s willingness to talk at length about any subject and idle soldiers often walking around unarmed underscored coming from and belonging to the Ndélé community. It also showed, however, that these rebels’ lives had not significantly changed compared to the previous era, nor did they have a meaningful impact on others’ well-being in a positive sense. Alleged autochthony does not automatically lead to legitimacy. The local rebel forces were also not in charge. Those leaders that did pull the strings and came to Ndélé with their armed battalions had no claim to (still) be part of the town’s community.

Rebels did not provide security during their rule. Fighting was simply absent. No other rebel group challenged the FPRC; if they did dare, brief spurts of violence – such as in the summer of 2018 – were the result. Nor did the state or peacekeepers challenge the rebels even as they continued to engage in practices that went against the UN mandate of the protection of civilians or that were barred by the January 2019 peace agreement. Public goods were minimal in Ndélé – and in that sense, not so different to other areas of CAR. Rebels did not get involved in their provision, redirecting people’s frustration about lacking services towards INGOs and the minimal state presence. Autochthony, security, and governance (exemplified through the education sector in this article) were thus discourses to legitimize rule and to avoid or redirect confrontation.

However, these were services provided in rebel territory not by rebel actors, as this article’s diachronic comparison laid bare: when their rule was challenged in 2020, more autochthonous (and idle) elements’ decisions were overturned by higher-ranking leaders; the lack of fighting turned into violence against civilians; and the public services provided by state and international actors were directly targeted. Rebel governance can thus not explain the duration of rebel rule in Ndélé: it is more adequately attributed to rebels’ unchallenged coercion via a form of rule we have termed here extraction. The latter emphasizes rebels’ authority, as designed to extract political and economic benefit from the people and territory of Ndélé as well as its wider surroundings. Unlike in rebel governance, coercion and service provision were not intertwined to gain legitimacy and continuously rule over the local populace. Rather, differentiating between the two – that is, coercion by rebels but governance in their territory by other actors – insulated rebels from the resource drain and potential criticism accompanying (inadequate) service provision. Rebel rule thus also did not end due to a notable change in governance, rather after violent internal competition over leadership and ethnic representation.

Ndélé, we argue, can – with its seven-year predominance of a rebel group as well as much longer histories of self-government and armed struggle – be counted as a ‘typical’ case of what the literature discusses as rebel governance. However, if the Ndélé case is not an exception then rebel-governance research could be too readily attributing governance in rebel territory to governance by rebel actors, as well as misinterpreting security actions for extractive purposes – as reflected in the modest number of reported conflict deaths – creating felt subjective security among the local population.Footnote83 Our qualitative analysis of the origins of rebellion in Ndélé thus counters the assumptions found in the previous scholarship and calls for a re-evaluation of existing case studies and the focussing anew of our theoretical lens when it comes to studying rebel authority in the future. For instance, quantitative findings pointing to excluded groups rebelling does not explain why Ndélé’s rebel groups continued on the same path even when offered generous packages of political inclusion and development, or as a notable Ndélé resident put itFootnote84:

They took weapons because of the road, school etc., so when you give them all that, if they take up weapons, they are bandits.

Distinguishing rebel governance from rebel extraction is a matter of longitudinal analysis – often the underlying rule system reveals itself only when compared across situations of ascending to, holding, and then falling from power. More than just an academic matter, making this distinction is also pertinent to policy. People on the ground are often acutely aware of whether a ruling order provides for them or takes from them.

Making such a distinction calls for a strong regard for local opinion, as well as acting upon it. While it might seem that governance in rebel-held territory is a better-than-nothing situation, it goes against the principle of do-no-harm: public goods can only be provided as long as rebels have an interest in them – or at least do not mind their existence. This provision might, however, justify inaction by peacekeepers and a lack of international, national, and domestic pressure on rebels to honour popular demands. Moreover, the very goods provided can become the target of looting and thereby resources for rebels when their extractive demands take precedence in changing circumstances. Finally, assuming rebel governance where rebel extraction is the underlying rule system ill prepares those mandated to protect civilians, as they are taken by surprise by the degree of violence and disrespect for civilian institutions and lives witnessed when rebel authority is challenged.

Acknowledgments

This article is inspired by and dedicated to Igor Calvin Acko. We thank the participants of the author workshop on rebel governance and the editors of this special issue, Regine Schwab and Hanna Pfeifer for their invaluable comments. We thank two anonymous collaborators for research assistance on the ground and Thibaut Le Forsonney for remote research assistance. We are thankful for research financing by I-WOTRO, award number W08.400.172, the Knowledge Management Fund, award number 8703_1.1. and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), project number 437386574.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tim Glawion

Tim Glawion is co-Editor in Chief of Africa Spectrum and a research fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies in Hamburg, Germany. He is the author of The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland and South Sudan (Cambridge University Press 2020) and numerous articles on order-making, local security, and the security arena. His current research focuses on security paradoxes and the monopoly on the use of force in Lebanon and the Central African Republic.

Anne-Clémence Le Noan

Anne-Clémence Le Noan is a PhD student at the Hertie School in Berlin, Germany and at Sciences Po in Paris, France. After working as a teacher in France, she conducted research on education in conflict affected zones such as the Central African Republic and Haiti. Her current work compares educational policies targeting social inequalities in Germany and France.

Notes

1. Kasfir, “Rebel Governance – Constructing a Field of Inquiry: Definitions, Scope, Patterns, Order, Causes,” 24.

2. Pfeifer and Schwab, “Politicising Rebel Governance.”

3. See note 2 above.

4. Boege, Brown, and Clements, “Hybrid Political Orders, Not Fragile States.”

5. Helmke and Levitsky, “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda.”

6. Lund, “Twilight Institutions: Public Authority and Local Politics in Africa.”

7. Glawion, The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan.

8. Glawion, de Vries, and Mehler, “Handle with Care! A Qualitative Comparison of the Fragile States Index’s Bottom Three Countries: Central African Republic, Somalia and South Sudan.”

9. Förster, “The Formation of Governance – the Politics of Governance and Their Theoretical Dimensions.”

10. Gurr, Why Men Rebel.

11. Gates, “Recruitment and Allegiance: The Microfoundations of Rebellion.”

12. Cederman, Wimmer, and Min, “Why Do Ethnic Groups Rebel? New Data and Analysis.”

13. Arjona, Kasfir, and Mampilly, Rebel Gov. Civ. War, 3.

14. Mampilly, Rebel Rulers.

15. Worrall, “(Re-)Emergent Orders: Understanding the Negotiation(s) of Rebel Governance,” 712.

16. Arjona, Rebelocracy.

17. Krasner and Risse, “External Actors, State-Building, and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction.”

18. Lee, Walter-Drop, and Wiesel, “Taking the State (Back) Out? Statehood and the Delivery of Collective Goods.”

19. Schäferhoff, “External Actors and the Provision of Public Health Services in Somalia.”

20. Lake and Fariss, “Why International Trusteeship Fails: The Politics of External Authority in Areas of Limited Statehood.”

21. Barakat and Urdal, “Breaking the Waves? Does Education Mediate the Relationship Between Youth Bulges and Political Violence?.”

22. Davies, “Education, Change and Peacebuilding.”

23. Pherali and Sahar, “Learning in the Chaos: A Political Economy Analysis of Education in Afghanistan.”

24. Interview with FPRC general coordinator, 22 July 2018, Ndélé.

25. Gerring, “Case Selection for Case-Study Analysis: Qualitative and Quantitative Techniques,” 648ff.

26. Gerring, “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good For?.”

27. Krause, “The Ethics of Ethnographic Methods in Conflict Zones.”

28. Kapiszewski, MacLean, and Read, Field Research in Political Science – Practices and Principles; Wedeen, “Reflections on Ethnographic Work in Political Science.”

29. Cf. Malejacq and Mukhopadhyay, “The ‘Tribal Politics’ of Field Research: A Reflection on Power and Partiality in 21st-Century Warzones.”

30. Glawion, van der Lijn, and de Zwaan, “Securing Legitimate Stability in CAR: External Assumptions and Local Perspectives”, we thank Aristide Oula for participating in our field study of Ndélé.

31. Cf. Bennett and Checkel, Process Tracing : From Metaphor to Analytic Tool.

32. Woodfork, Culture and Customs of the Central African Republic, 33.

33. Lombard, “Raiding Sovereignty in Central African Borderlands,” 83–96.

34. Cf. Lombard, Hunt. Game.

35. See note 10 above.

36. International Crisis Group, “Central African Republic. Anatomy of a Phantom State,” 23–27.

37. de Vries and Glawion, “Speculating on Crisis: The Progressive Disintegration of the Central African Republic’s Political Economy.”

38. Weyns, Hoex, and Spittaels, Mapping Conflict Motives: The Central African Republic, 21.

39. See note 9 above.

40. Glawion and De Vries, “Ruptures Revoked: Why the Central African Republic’s Unprecedented Crisis Has Not Altered Deep-Seated Patterns of Governance.”

41. Lombard, State of Rebellion. Violence and Intervention in the Central African Republic.

42. Appointment of national education officials is centralized and not regional. Qualified teachers receive, often after a wait of several years, an appointment in a region of the country as a mission order.

43. And more than a year after the rebels were dislodged the number of teachers taking up their posts in Ndélé had still not increased. Cf. Brice Ledoux Saramalet (21/02/2022), ”Centrafrique: Un seul enseignant titulaire pour le lycée de Ndélé”, Oubangui Media No 121.

44. The ”coupeurs de route” bandits have a long history in the RCA: Chauvin and Seignobos, ” L’imbroglio Centrafricain » État, Rebelles et Bandits,” 248.

45. Schouten, ”Roadblock Politics in Central Africa.”

46. See note 22 above.

47. International Crisis Group, “Centrafrique : Les Racines de La Violence,” 10 f; Weyns, Hoex, and Spittaels, Mapping Conflict Motives: The Central African Republic, 24ff.

48. Anonymous interviews, Ndélé, July 2018.

49. Interview with high-level civilian staff of MINUSCA, June 2019, Bangui.

50. United Nations Security Council, S/RES/2605 (2021).

51. See note 22 above.

52. The Sentry, “Fear, Inc.: War Profiteering in the Central African Republic and the Bloody Rise of Abdoulaye Hissène.”

53. Author’s translation. Jeune Afrique (19 January 2021), “Noureddine Adam: « Rien n’empêche d’imaginer François Bozizé à la tête de la CPC, » available online at: https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1107253/politique/noureddine-adam-rien-nempeche-dimaginer-francois-bozize-a-la-tete-de-la-cpc/.

54. The assessment was not representative but randomized and diversified. It is however intriguing that people being assessed in rebel territory during rebel rule were overwhelmingly and openly critical of them.

55. Male barber, identifying as Catholic and Ngadja ethnicity. Most of the interviews were conducted in Sango or a local language and then transcribed into French. All the interviews have been anonymized. All the interviews with the local population took place between February and April 2019. The dates are not given to avoid identification of specific respondents. French original: « Qu’ils ne se laissent plus enrôler par les rebelles pour se retourner contre nous. Nous étions une même famille. Nous nous promenions ensemble, alors qu’ils étaient les premiers à nous tuer.

56. Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset.”

57. Cf. Glawion, The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan.

58. In contrast to the rebel groups of the former Seleka, the Anti-Balaka were deliberately fluid in their organization, composition, and resource extraction. They were hundreds of unconnected, barely armed, locally rooted village defence groups.

59. Le Noan and Glawion, ”Education Nationale En Territoire Rebelle: Le Cas Du Lycée de Ndélé En République Centrafricaine.”

60. Female shopkeeper, identifying as Muslim and Runga ethnicity, translation by Aristide Oula and the authors.

61. Cf. Weinstein, Inside Rebellion.

62. See note 43 above.

63. United Nations Security Council. (2018). Midterm report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2399 (2018): Vol. S/2018/729, pp. 97–99.

64. Interview with a leading FPRC member, July 2018, Ndélé. It is not confirmed how regularly these taxes are levied and how far they are negotiable.

65. Interview with officials in the education sector in Bangassou, August 2018.

66. Cf. Focus group discussion with students of secondary high school, August 2018, Ndélé.

67. Cf. among many others Weinstein, Inside Rebellion; Arjona, Rebelocracy.

68. Document viewed and photographed in Bangassou, 6 August 2018. Proviseur du Lycée de Bangassou: ”Rapport du fin du 1e semestre de l’année académique 2017–2018”.

69. International Crisis Group, ”Réduire Les Tensions Électorales En République Centrafricaine.”

70. Cf. communiqué available in United Nations Security Council, “Final Report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic Extended Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2507 (2020),” vol. S/2020/662, 2020, 91 f, 10.1017/s0020818300030599.

71. MINUSCA (7 March 2020) ”La MINUSCA condamne énergiquement le meurtre d’un de ses employés à Ndélé [Press release]”, available online at: https://minusca.unmissions.org/la-minusca-condamne-energiquement-le-meurtre-d%E2%80%99un-de-ses-employes-ndele.

72. United Nations Security Council, S/2020/662:9.

73. Ibid.:11.

74. UNHCR (2020), « Rapport mensuel de monitoring de protection: Bamingui-Bangoran | Août 2020 »: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/79637.

75. Cluster Protection Centrafrique (2020), “CMP Juin 2020 statistiques detaillees des sites PDIs en RCA”: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/78469; However, since many thousands had already sought shelter in Bamingui-Bangoran coming from Birao, some of those seeking refuge in camps might be from the neighbouring prefecture Vakaga.

76. Cf. letter available in United Nations Security Council, S/2020/662:73 f.

77. United Nations Security Council, S/2020/662:91 f.

78. United Nations Security Council, S/2020/662:84 f.

79. OCHA: Spike in attacks against humanitarian organisations in Ndélé town, 9 May 2020, available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/spike-attacks-against-humanitarian-organisations-nd-l-town.

80. Joint statement on the suspension of activities in Ndélé, Central African Republic,” 19 May 2020, available online at: https://reliefweb.int/report/central-african-republic/joint-statement-suspension-activities-nd-l-central-african-republic.

81. See note 70 above.:15.

82. United Nations Security Council, “Final Report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic Extended Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2536 (2020).”

83. Cf. Glawion, “Cross-Case Patterns of Security Production in Hybrid Political Orders: Their Shapes, Ordering Practices, and Paradoxical Outcomes.”

84. Interview with Ndélé luminary, 17 July 2018. French original: « Ils ont pris des armes à cause de la route, l’école etc., alors quand on donne tout ça, s’ils prennent des armes, ils sont des bandits. »

Bibliography

- Arjona, Ana. Rebelocracy. Rebelocracy: Social Order in the Colombian Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016. doi:10.1017/9781316421925.

- Arjona, Ana, Nelson Kasfir, and Zachariah Mampilly. Rebel Governance in Civil War. Edited by, Ana Arjona, Nelson Kasfir, and Zachariah Mampilly. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316182468

- Barakat, Bilal, and Henrik Urdal. “Breaking the Waves? Does Education Mediate the Relationship between Youth Bulges and Political Violence?” Policy Research Working Paper (2009).

- Bennett, Andrew, and Jeffrey T Checkel. “Process Tracing : From Metaphor to Analytic Tool.” In Strategies for Social Inquiry, edited by Andrew Bennett and Jeffrey T Checkel. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Boege, Volker, M Anne Brown, and Kevin P Clements. “Hybrid Political Orders, Not Fragile States.” Peace Review 21, no. 1 (2009): 13–21. doi:10.1080/10402650802689997.

- Cederman, Lars-Erik, Andreas Wimmer, and Brian Min. “Why Do Ethnic Groups Rebel? New Data and Analysis.” World Politics 62, no. 1 (2010): 87–119. doi:10.1017/S0043887109990219.

- Chauvin, Emmanuel, and Christian Seignobos. “« L’imbroglio Centrafricain » État, Rebelles et Bandits.” Afrique Contemporaine 248 (2014).

- Davies, Lynn. “Education, Change and Peacebuilding.” FriEnt Working Group on Peace and Development, no. 1 (2013): 1–7.

- Förster, Till. “The Formation of Governance - the Politics of Governance and Their Theoretical Dimensions.” In The Politics of Governance - Actors and Articulations in Africa and Beyond, edited by Lucy Koechlin and Till Förster, 197–218. New York, Oxon: Routledge, 2015.

- Gates, Scott. “Recruitment and Allegiance: The Microfoundations of Rebellion.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46, no. 1 (2002): 111–130. doi:10.1177/0022002702046001007.

- Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good For?” American Political Science Review 98, no. 2 (2004): 341–354. doi:10.1017/S0003055404001182.

- Gerring, John. “Case Selection for Case-Study Analysis: Qualitative and Quantitative Techniques.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by Janet M Box-Steffensmeier, Henry E Brady, and David Collier, 645–684. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Glawion, Tim. The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020. doi:10.1017/9781108623629.

- Glawion, Tim. “Cross-Case Patterns of Security Production in Hybrid Political Orders: Their Shapes, Ordering Practices, and Paradoxical Outcomes.” Peacebuilding (2022): 1–16. doi:10.1080/21647259.2022.2079246.

- Glawion, T, and L De Vries. “Ruptures Revoked: Why the Central African Republic’s Unprecedented Crisis Has Not Altered Deep-Seated Patterns of Governance.” Journal of Modern African Studies 56, no. 3 (2018): 421–442. doi:10.1017/S0022278X18000307.

- Glawion, Tim, Lotje de Vries, and Andreas Mehler. “Handle with Care! A Qualitative Comparison of the Fragile States Index’s Bottom Three Countries: Central African Republic, Somalia and South Sudan.” Development and Change 50, no. 2 (2019): 277–300. doi:10.1111/dech.12417.

- Glawion, Tim, Jair van der Lijn, and Nikki de Zwaan. “Securing Legitimate Stability in CAR: External Assumptions and Local Perspectives.” SIPRI Policy Study, no. September (2019): 20. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/0919_policy_study_car.pdf.

- Gurr, Ted Robert. Why Men Rebel. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1970.

- Helmke, Gretchen, and Steven Levitsky. “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda.” Perspectives on Politics 2, no. 4 (2004): 725–740. doi:10.1017/S1537592704040472.

- International Crisis Group. “Central African Republic. Anatomy of a Phantom State.” Africa Report 136, no. November (2007).

- International Crisis Group. “Centrafrique : Les Racines de La Violence.” Rapport Afrique N° 230, no. September (2015). http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/africa/central-africa/central-african-republic/230-centrafrique-les-racines-de-la-violence.

- International Crisis Group. “Réduire Les Tensions Électorales En République Centrafricaine.” Rapport Afrique N°296 (2020).

- Kapiszewski, Diana, Lauren M MacLean, and Benjamin L Read. Field Research in Political Science - Practices and Principles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Kasfir, Nelson. “Rebel Governance – Constructing a Field of Inquiry: Definitions, Scope, Patterns, Order, Causes.” Rebel Governance in Civil War (2015). doi:10.1017/CBO9781316182468.002.

- Krasner, Stephen D, and Thomas Risse. “External Actors, State-Building, and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction.” Governance (2014): 1–23. doi:10.1111/gove.12065.

- Krause, Jana. “The Ethics of Ethnographic Methods in Conflict Zones.” Journal of Peace Research 58, no. 3 (2021): 329–341. doi:10.1177/0022343320971021.

- Lake, David A, and Christopher J Fariss. “Why International Trusteeship Fails: The Politics of External Authority in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Governance 27, no. 4 (October, 2014): 569–587. doi:10.1111/gove.12066.

- Lee, Melissa M, Gregor Walter-Drop, and John Wiesel. “Taking the State (Back) Out? Statehood and the Delivery of Collective Goods.” Governance 27, no. 4 (2014): 635–654. doi:10.1111/gove.12069.

- Lombard, Louisa Nicolaysen. Raiding Sovereignty in Central African Borderlands. Durham, NC: Duke University, 2012.

- Lombard, Louisa. State of Rebellion. Violence and Intervention in the Central African Republic. London: Zed Books, 2016.

- Lombard, Louisa. Hunting Game. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020. doi:10.1017/9781108778794.

- Lund, Christian. “Twilight Institutions: Public Authority and Local Politics in Africa.” Development and Change 37, no. 4 (2006): 685–705. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2006.00497.x.

- Malejacq, Romain, and Dipali Mukhopadhyay. “The ‘Tribal Politics’ of Field Research: A Reflection on Power and Partiality in 21st-Century Warzones.” Perspectives on Politics 14, no. 4 (2016): 1011–1028. doi:10.1017/S1537592716002899.

- Mampilly, Zachariah Cherian. “Rebel Rulers.” Rebel Rulers (2017). doi:10.7591/9780801462979.

- Noan, Anne-Clémence Le, and Tim Glawion. “Education Nationale En Territoire Rebelle: Le Cas Du Lycée de Ndélé En République Centrafricaine.” ABI Working Paper 10, no. 10 (2018).

- Pfeifer, Hanna, and Regine Schwab. “Politicising the Rebel Governance Paradigm. Critical Appraisal and Expansion of a Research Agenda.” Small Wars and Insurgencies 0(0).

- Pherali, Tejendra, and Arif Sahar. “Learning in the Chaos: A Political Economy Analysis of Education in Afghanistan.” Research in Comparative and International Education 13, no. 2 (2018): 239–258. doi:10.1177/1745499918781882.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen. “Introducing ACLED: An Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 September 28 (2010): 651–660. doi:10.1177/0022343310378914.

- Schäferhoff, Marco. “External Actors and the Provision of Public Health Services in Somalia.” Governance 27, no. 4 (2014): 675–695. doi:10.1111/gove.12071.

- Schouten, Peer. “Roadblock Politics in Central Africa.” Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space 37, no. 5 (2019): 924–941. doi:10.1177/0263775819830400.

- Sentry, The. “Fear, Inc.: War Profiteering in the Central African Republic and the Bloody Rise of Abdoulaye Hissène”. November (2018).

- United Nations Security Council. “Final Report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic Extended Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2507 (2020).” 2020, no. 662 (2020). doi: 10.1017/s0020818300030599

- United Nations Security Council. “Final Report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic Extended Pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2536 (2020).” 2021, no. 569 (2021). doi: 10.1017/S0020818300023481

- Vries, Lotje de, and Tim Glawion. “Speculating on Crisis: The Progressive Disintegration of the Central African Republic’s Political Economy. ” Clingendael CRU Report, no. October (2015). https://www.africabib.org/htp.php?RID=397799888

- Wedeen, Lisa. “Reflections on Ethnographic Work in Political Science.” Annual Review of Political Science 13, no. 1 (2010): 255–272. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.052706.123951.

- Weinstein, Jeremy M. “Inside Rebellion.” In Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511808654.

- Weyns, Yannick, Lotte Hoex, and Steven Spittaels. Mapping Conflict Motives: The Central African Republic. IPIS, Edited by. Antwerp: IPIS, 2014.

- Woodfork, Jacqueline. “Culture and Customs of the Central African Republic.” In Culture and Customs of Africa, edited by Toyin Falola. Westport, CN, London: Greenwood Press, 2006.

- Worrall, James. “(Re-)emergent Orders: Understanding the Negotiation(s) of Rebel Governance.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 28, no. 4–5 (2017): 709–733. doi:10.1080/09592318.2017.1322336.