ABSTRACT

The example of the Thirty Years War (1618–48) demonstrates that small war was already integral to the conduct of premodern hostilities. Commanders employed these methods with a purpose and generally tried to limit the accompanying violence to preserve discipline and effectiveness, as well as their claims to be waging a just war. We explain why conventional histories have neglected the presence of small war in premodernity, and show how its importance, methods, and wider impact can be reconstructed through innovative digital mapping techniques, which have the potential to be applied to conflicts in other times and places.

Small war resists a succinct definition and has changed character over time. Most studies understandably focus on recent or contemporary examples, while discussions of earlier periods sometimes risk becoming a teleological search for antecedents, especially in terms of doctrine. We should not mistake the frequently disparaging remarks contemporaries made about small war and its practitioners to mean that it was not an important part of premodern conflict. This paper will demonstrate that it was integral to the conduct of the Thirty Years War, Europe’s most destructive conflict prior to the two world wars, and that armies had already evolved sophisticated and effective ways of practicing it.

The first task will be to explain the relative neglect of small war in this conflict and the concomitant overemphasis on allegedly ‘decisive’ battles, which were in fact quite rare. A fruitful way forward will be explored in the main part of the article through a case study of small war in Westphalia, the region of north-western Germany usually considered as only of secondary importance in the wider history of the war. Westphalia’s experience will be contextualised, followed by an overview of small war operations there to indicate their character and variety. The discussion will illustrate how the application of digital mapping techniques assists the presentation and the interpretation of the patchy and often difficult evidence and improves our understanding of the dynamic between the different forms of warfare and their wider impact on the area of operations.

For clarity, the Thirty Years War is defined here as the struggle over the political and religious order within the Holy Roman Empire which began with the infamous Defenestration of Prague (23 May 1618) and concluded with the twin treaties of Münster and Osnabrück forming the Westphalian peace settlement (24 October 1648). This is in distinction to the common, but less precise use of the term to encompass Europe’s other conflicts, notably the Eighty Years War (or Dutch Revolt, 1568–1648), the Franco-Spanish War (1635–59), and Sweden’s intermittent conflict with Poland (1621–9). While several belligerents participated in more than one of these wars simultaneously, they nonetheless regarded them as distinct and demarcated their commitments carefully.Footnote1

Premodern small war in the literature and archives

The study of pre-modern small war has concentrated on tracing its presence in military treatises, as well as the perceived shift in the status and role of its practitioners during the mid-eighteenth century, which in turn is presented as a step towards the more fluid and hence ‘modern’ approaches associated with the era of the French Revolution and Napoleon.Footnote2 In fact, the term ‘petites guerres’ (small wars) was already widely used by the 1630s in public discussion of the Thirty Years War.Footnote3 The actual practice of small war has received less attention. There are excellent studies of French operations during 1672–1697, demonstrating the close correlation between efforts to secure vital resources, whilst simultaneously degrading the enemy’s capacity. The high level of violence attracted considerably public interest, which in turn could influence political and military decisions.Footnote4

The only substantial study for the Thirty Years War examines the use of irregulars by Sweden and Denmark in their separate conflict 1643–5, launched by the former to ensure the latter would not act as a hostile broker at the peace congress which had just opened in the Westphalian towns of Münster and Osnabrück.Footnote5 This relative neglect is not surprising given how conventional military history depicts the whole of Europe’s early modernity as the Age of Battles.Footnote6 The concept of ‘decisive’ battles is central to the influential thesis of a Military Revolution, which supposedly transformed warfare through the development of larger, more professional armies. The Thirty Years War has been seen as the peak of these developments, allegedly forging the ‘standing armies’ characterising Europe’s Old Regime.Footnote7

In fact, battles and major sieges were comparatively rare with only 48 engagements involving 7,000 or more combatants across the thirty years.Footnote8 Major sieges were equally uncommon. Battles have been noted for their bloody butcher’s bills, but the war’s deeper demographic, economic, and societal impact was primarily made through the far more numerous and extensive minor operations like skirmishes, raids, ambushes, and foraging expeditions.Footnote9

The nature of the surviving historical records has fundamentally influenced the conventional view, as well as posing considerable challenges to anyone seeking to understand small war at this time. The Thirty Years War was a conflict of multiple belligerents fought in a vast area of decentralised political authority. The Empire lacked a single, national archive, and the records of its main central institutions were deliberately dispersed amongst the successor states after these achieved sovereignty in 1806. Seventeenth century armies certainly generated mountains of paperwork, but administration remained largely in the hands of often relatively junior officers who were expected to sustain their units on what would today be considered a semi-private basis. Relatively few papers survive in private family archives, which are scattered and sometimes still only partially accessible.Footnote10 The concentration of forces for major operations required considerable effort and correspondingly left a more obvious archival footprint.

Battles were considered major events in participants’ lives and feature prominently in eyewitness accounts, as well as contemporary art. Paintings and engravings of battles and major sieges were usually large format works, whereas small war actions appear in compact genre paintings and engravings like the famous cycle ‘The Miseries of War’ produced by Jacques Callot, which are only each the size of a banknote. Other than infamous massacres, the events depicted are usually generic scenes of violence. These in turn have become iconic for the war as supposedly a directionless ‘all-destructive fury’, further hindering our understanding of how and why certain operations were conducted.Footnote11

Civilian records include summary lists and information compiled at the request of district and central authorities, as well as diaries and other personal accounts.Footnote12 The district of Ahlen in the bishopric of Münster was plundered 17 times between 1618–42. The official record for 1633–49 lists over 40 incidents of various factions causing damage, with only two years (1646, 1648) without incident.Footnote13 Such sources have traditionally been used to assess the war’s broader impact, but while they also offer detailed insight into small war operations, they are very difficult to use. The information is generally recorded without context, as those involved often did not know to which side parties of soldiers belonged, or why they were there, beyond their demands for resources.

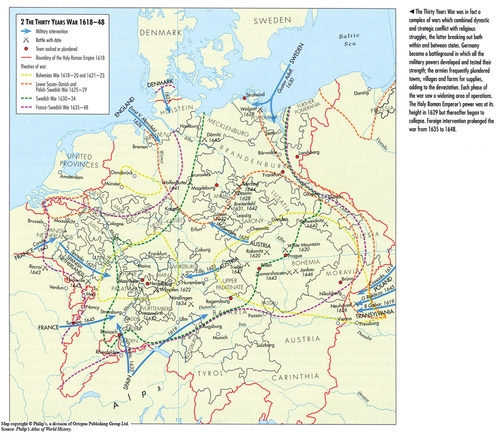

We propose mapping and spatial network analysis as additional research tools. Current cartographical approaches used in military history are not well equipped to depict small war and their deficiencies have helped obscure the significance of small war and its broader impact on civilians. Aside from showing the locations of the major battles and sieges, the existing maps usually display homogenous fronts, not distinguishing between empty spaces and areas with affected settlements. They also depict major campaigns as snail trails that not only fail to show the actual routes taken, but also do not reflect the dispersed character of military movement nor the dynamics of conflict at a more local level (see ). Small war operations are omitted completely.

Figure 1. An example of the conventional cartography of conflict. Source: P.K. O’Brien gen.ed. Oxford Atlas of wWorld hHistory (Oxford University Press, 1999), 159.

The true complexity of military operations begins to emerge when we combine what we can recover from archival sources with more creative mapping techniques. Our approach combines information on the location of garrisons with the historical road mapsFootnote14 and spatial network analysisFootnote15 to calculate the areas that could have been affected by operations. We assume a maximum zone of influence for each garrison as having a radius of 25 km, considering that a mounted man could ride a round trip of twice that distance by road in a day.Footnote16 Our calculations include adjustments for the effect of the slope of the roads on the travelled distance, as well as rivers and other topographical features.Footnote17 An advantage of this approach is that the discovery of additional historical data can be used directly to improve the digital maps.

Westphalia as a war zone

Westphalia is usually treated as a secondary theatre in general accounts of the war, probably because there were no major sieges and only three substantial battles, none of which is particularly famous or considered decisive. The region was indeed secondary to the war’s primary belligerents (the Habsburg emperor, his Spanish and Bavarian allies, and his Danish and then Swedish and French opponents). Nonetheless, its location in northwest Germany placed it directly next to the Low Countries, which saw prolonged fighting between Spain and the Dutch once their truce expired in 1621, as well as between Spain and France after the latter began its own war in support of the Dutch in 1635. Throughout, those belligerents engaged in the war in the Empire were concerned to keep their struggle separate from these western European wars: for instance, France’s incremental support for Sweden after 1630 was intended to prevent the emperor from defeating his German opponents and turning the Empire’s considerable resources to support Spain in the west.

Westphalia was one of the Empire’s ten administrative regions (called Kreise) which, together with the Bohemian lands and those collectively called Imperial Italy, formed the extent of imperial jurisdiction.Footnote18 It only loosely corresponds with the modern Federal State of Nordrhein-Westfalen and, at the time, encompassed around 59,600 km2, or just under 9% of Empire’s surface area (excluding Imperial Italy) with probably a similar proportion of its 23 million inhabitants. Within it, were around 50 secular principalities and counties, of which only six were substantial. The collapse of the Jülich-Cleves conglomerate after 1609 removed the only powerful local secular prince and increased the proportion of lords based elsewhere who held Westphalian land, notably the duke of Pfalz-Neuburg who secured Jülich and Berg in 1609.

By contrast, nearly four-fifths of Westphalia was composed of ecclesiastical territories (compared to a proportion of about a seventh of the Empire overall). In descending order of importance, these were the bishoprics of Münster, Paderborn, Osnabrück, Minden, Verden, and seven large abbeys and convents including Corvey and Herford. Another bishopric, Liege, formally belonged to Westphalia, but was isolated as an enclave within the neighbouring region known as Burgundy, which belonged to Spain under nominal imperial jurisdiction. The character of these lands was important because their disputed possession was both a primary cause of the war, and a core goal for most belligerents.

Another region, the Electoral Rhine totalling 26,500 km2, lay partially to the south, with the rump of the original duchy of Westphalia confusingly belonging to electoral Cologne as an enclave within the region of Westphalia. The Palatinate, the only substantial secular territory in Electoral Rhine, was the initial leader of the anti-Habsburg alliance, whereas the other three principal members were Mainz, Cologne, and Trier, which all joined the Liga (Catholic League), formed by Bavaria, which backed the Habsburgs throughout the war. Cologne was the most militant of the three and the most powerful principality in northwest Germany thanks to the common practice of electing his ruler to govern the Westphalian ecclesiastical lands. Ferdinand of Bavaria (1577–1650), archbishop-elector of Cologne from 1612, also ruled Münster, Paderborn, and Liege, as well as Hildesheim in the Lower Saxon region immediately east of Westphalia.Footnote19

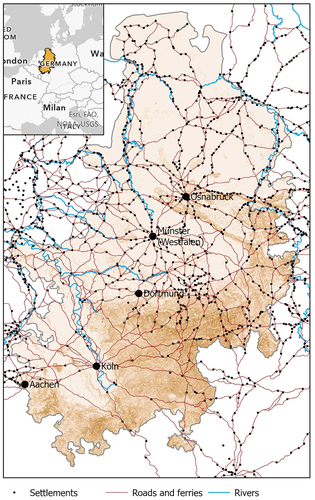

Most inhabitants lived in small villages and hamlets. The self-governing imperial city of Cologne was Westphalia’s principal city but – in a reverse of the duchy of Westphalia – was an enclave within electoral Cologne territory. It had around 40,000 people on the eve of the war, making it one of the Empire’s largest cities. Though Catholic, it tried to remain neutral to preserve its economic ties across northwest Europe.Footnote20 The region’s other two imperial cities, Aachen (pop.20–25,000) and Dortmund (pop.6–7000), attempted the same course, but with less success. Münster and Osnabrück each had 10–12,000 inhabitants, while around another ten towns had at least 2,000 each. Several of these were on the Hellweg, one of the Empire’s most important roads dating back to the neolithic era, which ran from the Rhine crossing next to Duisburg in the west, through Essen, Dortmund, Unna, Werl, Soest, Erwitte, Geseke, Salzkotten, Paderborn to Höxter and Corvey on the Weser in the east on the border with Lower Saxony (See ).

Figure 2. Westphalia around 1600. The blue lines and red lines represent rivers and roads, respectively. Black dots show the location of settlements. The brown shading indicates the topographic “slope The coloured version of this map can be viewed online”.

The western edge of Westphalia had already suffered raiding during the first phase of the Dutch Revolt against Spain (1568–1609), when the rival armies tried to outflank each other through incursions eastwards into the bishopric of Münster. Meanwhile, electoral Cologne had witnessed considerable fighting as Spain intervened to support a Bavarian candidate in a disputed episcopal election (1583–8). As a staunch Catholic, the Bavarian Wittelsbach family were considered more likely to deny access to their Westphalian lands to the Dutch. Though Spain concluded the Twelve Years Truce with the Dutch in 1609, the Lower Rhine was immediately plunged into renewed turmoil through a disputed succession to Jülich-Cleves, the only substantial conglomerate of secular land in the region. Both Spain and the Dutch were wary of reigniting their own war prematurely, and correspondingly restricted their involvement to seizing strategic minor towns improving their access to the Lower Rhine crossings. The Dutch remained entrenched in these until 1672, despite never becoming formally involved in what became the Thirty Years War.Footnote21

Many of the features of small war common during the Thirty Years War were already present during these events, though not on the same scale or level of destruction. The experience also shaped how the region’s numerous local authorities responded to events as they unfolded after 1618, notably by fostering widespread scepticism of the efficacy of robust military action against incursions and sustaining a belief that intra and supra-regional discussions offered a cheaper and less bloody way to limit violence.Footnote22 Such cooperation became much harder, but never entirely disappeared after 1618. The elector of Cologne supplied regular troops to support the Liga’s assistance to the emperor after 1619, but otherwise refrained from raising units for local defence for fear of antagonising the Dutch. Like other Westphalian rulers, he preferred to rely on local militias, despite their repeated failures to prevent earlier incursions. The militia were paid from local resources, whereas regular troops required new taxes and were thus more contentious in negotiations with the various assemblies known as Estates composed of the leading nobles, clergy, and urban representatives.Footnote23

The militia’s inadequacy was exposed in January 1622 when forces led by Christian of Brunswick burst into Westphalia. This began what was to become a cycle of incursions of forces allied to the anti-Habsburg faction. As in this case, these usually invaded from Lower Saxony to the east and had to be countered by forces organised by electoral Cologne from its dispersed territories, as well as those sent periodically by the emperor or Bavaria. Prior to the end of 1631, the invaders lacked a presence in the region and their inability to secure bases limited their operational effectiveness. Christian and his collaborator, Ernst von Mansfeld, were military entrepreneurs supporting the anti-Habsburg cause in the hope of personal advancement. Neither had substantial possessions, and they were entirely dependent on securing money and supplies locally to sustain their operations, since their nominal masters were rarely able to pay them.

Christian was driven out after four months but had captured Lippstadt, roughly equidistant from Münster, Paderborn, and Dortmund, which offered a strategic base and which his forces managed to hold until October 1623.Footnote24 Meanwhile, Mansfeld ensconced himself in the duchy of East Frisia, in Westphalia’s northwest corner next to the Dutch border.Footnote25 His failure to assist Christian contributed to the latter’s defeat at Stadtlohn in the bishopric of Münster on 6 August as he tried to escape the pursuing Liga main army. The engagement was the largest battle in Westphalia during the war, involving 35,700 combatants with 7,000 casualties.Footnote26 Despite these numbers, in terms of size it ranks only as 15th among the war’s 48 battles. The Dutch arranged in January 1624 for Mansfeld’s troops to be paid off at East Frisia’s expense once his presence there began to conflict with their own interests, which centred on a prolonged occupation of the port of Emden.

Spain had assisted in Christian’s defeat, but otherwise restricted its operations to ejecting the Dutch from the town of Jülich in February 1622, thereby blocking the route up the Rhine. Spanish troops remained there until 1660.Footnote27 These victories gave pro-Habsburg forces control of most of Westphalia from which they drew money and supplies at considerable cost to the inhabitants. Denmark’s intervention restarted the war in 1625 but did not affect Westphalia beyond a brief Danish incursion into Osnabrück.

The situation altered radically with Sweden’s victory at Breitenfeld in September 1631, fifteen months after its invasion of northeast Germany restarted the war after Denmark’s defeat in 1629. Despite French financial backing, Sweden could not pay its German allies and collaborators, upon whom it depended to sustain its war in the Empire. Payment came in the form of conquered lands which were ‘donated’ in return for military cooperation from the recipients. The landgrave of Hessen-Kassel and the duke of Lüneburg backed Sweden in the hope of acquiring the numerous, rich Catholic ecclesiastical lands in Westphalia and Lower Saxony. The location of these territories largely determined their operations, and they were reluctant to send their troops to support the Swedes elsewhere.Footnote28 Sweden tolerated this, because its own forces rarely constituted more than a third of the 10–20,000 or so anti-Habsburg troops in Westphalia. Its ability to control its allies declined further after the death of its warrior king, Gustavus Adolphus, in November 1632.

Both sides were repeatedly hampered by the requirement to despatch senior officers and troops from Westphalia to assist elsewhere in the Empire where the war became general after 1631, rather than being waged in no more than three regions simultaneously. The balance shifted first in Sweden’s favour in summer 1633 after the imperial and Liga field army in Westphalia was defeated in Lower Saxony where it had intervened to assist a beleaguered garrison. Sweden was able to seize Osnabrück, which it garrisoned until 1643 when this town, along with Münster, was declared neutral as venues for the peace congress. Though the Hessians also benefited, most of their army moved southeast in a bid to recover their homeland in 1634. The imperial victory at Nördlingen caused Sweden’s position across southern and much of western Germany to collapse that September.

However, the Hessians were left in possession of most of their Westphalian garrisons in the hope that they could be persuaded to accept disadvantageous terms at the Peace of Prague in May 1635 which was intended to end the war to the emperor’s favour. It was not until summer 1636 that the small imperial army in Westphalia seized key points along the Hellweg, thereby ramping up pressure on the Hessians who were cut off from their homeland. Facing defeat by 1637, the Hessians left two strong garrisons in their home fortresses and relocated their main army to East Frisia where they lived, like Mansfeld, at the locals’ expense. Distractions elsewhere encouraged continued toleration of Hessian neutrality into 1639. Meanwhile, an attempt by the exiled elector Palatine to recover his lands in collaboration with Sweden was crushed at Vlotho on 17 October 1638, the second of Westphalia’s three battles, which involved only around 8,400 combatants.Footnote29

Though small, the victory nonetheless encouraged Ferdinand of Cologne to revive efforts at regional cooperation, intending to persuade the various Westphalian territories to fund an army of at least 19,000 men to eject the remaining foreign troops and ensure future security.Footnote30 His efforts were hampered by the refusal of the prince of Pfalz-Neuburg to cooperate. As the leading secular Catholic prince, his voice mattered, while he had repeated sanction from the emperor for his armed neutrality which was seen as a way of demarcating war in the Empire from that between Spain and the Dutch.Footnote31

Pfalz-Neuburg neutrality collapsed in December 1639 as the Hessians re-entered the war while the imperial army became increasingly desperate for resources.Footnote32 The return of the main imperial field army to eastern Westphalia late in 1640 briefly tipped the balance again, but the situation changed as soon as it left. Meanwhile, Sweden’s former south German army, which had retreated west into Alsace late in 1634, passed more firmly under the control of its new French paymasters after the death of its commander in 1639. Keen to shore up its alliance with Sweden, France had sent this force into central Germany that year, but strategic disagreements led to it being redeployed to the Lower Rhine late in 1640 where it cooperated with Hessian efforts to secure more bases. A rash attempt by the local imperial commander to confront this combination ended in defeat at Kempen in electoral Cologne on 17 January 1642. The third and final Westphalian battle involved 16,500 combatants of whom around 2,500 were killed or wounded and 3,000 captured, ranking it 33rd of the 48 battles.Footnote33 The victory enabled the Hessians to seize a string of new bases along the Lower Rhine, but relations with the French remained difficult until the latter switched their troops back to southwest Germany in 1643, thus removing them as competitor for scarce resources.

Their departure assisted Ferdinand of Cologne who finally secured the Westphalians’ agreement to establish a regional army in June 1644. At around 15,000 effectives, this was large enough to stabilise the situation, but too small to eject the Hessians and remaining Swedish troops. Having conquered Verden and other areas on the Westphalian-Lower Saxon frontier in 1644–5, the main Swedish army finally launched an invasion in April 1646.Footnote34 This improved the Hessians’ position, but momentum was lost as soon as the Swedes left again a month later. Though Cologne joined Bavarian in temporarily adopting neutrality in April-August 1647, this gave it greater leverage over the emperor who was desperate for their support. Local generals replaced imperial officers in command of the Westphalian army which managed to hold its own against the Hessians until the end of the war.Footnote35

The conduct of small war

As the foregoing indicates, it proved difficult to secure a military preponderance in Westphalia because troops were frequently summoned elsewhere each spring, only returning as the autumnal rains signalled the end of the ‘campaign season’. As a relatively populous and agriculturally rich region, Westphalia was prized as a location for ‘winter quarters’ where field units could rest, re-equip, and prepare for next year’s campaign. The emperor and his allies regarded it as ‘home’ territory and expected the local authorities to accommodate their troops – naturally, at the inhabitants’ expense. Imperial demands for winter quarters carried some weight but were frequently met with requests for mitigation or exemption on the grounds of growing impoverishment as the war progressed.Footnote36 The presence of large forces over the winter offered the prospect of major operations at either end of the campaign season, but the wider strategic situation rarely permitted either side to leave substantial numbers in Westphalia for long.

Small war was less seasonally determined as it involved far fewer troops operating more quickly over shorter distances. It is better to consider the forces involved as appearing across a spectrum rather than the sharp division between special forces and line of battle troops envisaged by much of the secondary literature. All the types employed in small war also appeared on the battlefield. The imperial army possessed vastly superior light cavalry who were invariably called ‘Croats’ or ‘Cossacks’, though both were recruited across East Central and South-East Europe and included many Hungarians, Poles, and Ukrainians.Footnote37 Their employment reflected the early modern equivalent of later colonial ‘martial race’ theory, that certain peoples possessed unique skills and proclivities suiting them to particular kinds of warfare.

This explains their relative absence amongst the Swedish, French, and Hessian armies, which lacked the ability to recruit them. These powers relied on dragoons who also featured in the imperial and Liga armies and who had emerged around 1600 as mounted infantry. They and the eastern types of light cavalry could also be deployed in regular battles to perform broadly similar roles as in small war: scouting and screening movements, disruption of the enemy, notably by harassing his flanks, and raiding.Footnote38

Likewise, line troops could also be used for small war operations. Musketeers were frequently ‘commanded’ or drawn from their parent regiment and sent on detached duty. Raiding parties often included musketeers mounted on the cruppers of cavalrymen’s horses to speed movement. Medium cavalry called arquebusiers were also used, particularly in larger parties launching surprise attacks on enemy wintering in scattered billets. Arquebusiers briefly fell from favour in the imperial army during the 1630s but were used throughout by the Swedes and their allies as all-purpose cavalry.

The core components of line of battle formations appeared less frequently. Pikemen provided the backbone of infantry formations but were only effective when fighting in close order. Cuirassiers were better armoured than arquebusiers and were considered frontline cavalry who were usually too expensive and slow-moving to risk in small war. Artillery was also cumbersome, slow, and in short supply. The Westphalian army’s train in July 1638 totalled only 12 guns, 3 mortars, and 6 petards, but still required 109 wagons for ammunition and equipment, as well as 758 horses to move it.Footnote39

The local population was a variable resource. Militia were poorly suited for offensive operations but could perform well when defending their hometowns when they were often supplemented with armed inhabitants, such as the repulse of a surprise attack on Höxter in 1621.Footnote40 Though clergy often viewed the conflict as an apocalyptic showdown between good and evil, the secular authorities did not summon their populations to holy war and preferred that they remained passive, obedient subjects working to pay their taxes.Footnote41 The diversity of the Empire’s political geography and the corresponding complexity of the issues at stake also mitigated against partisan warfare, because the distinctions between the contending parties were frequently blurred or confused. This was a civil war into which foreign powers intervened, ostensibly in the name of supporting one of several interpretations of the Empire’s common legal and political order. Several important actors changed sides or retreated into at least temporary neutrality. Under these circumstances, it was hard to mobilise popular support, whilst all established political authorities remained suspicious of autonomous popular action. By contrast, the Swedish-Danish conflict of 1643–5 which was an inter-state war with more clearly defined fronts in which the Danish government encouraged its population to resist the Swedish invasion.Footnote42

The closest to partisans in Westphalia were the free companies operating on the fringes of official control or even beyond it. Some of these were the remnants of units, which were cut off in areas overrun by superior enemy forces, such as the small imperial and Liga detachments contesting Hessian control in the bishopric of Paderborn in 1631–3.Footnote43 The rulers and senior commanders feared independent action could slip entirely from their control, particularly as marauders added to the problem of banditry already present since the 1580s. Marauders were individuals or small groups wholly beyond official control, acting on their own accounts and using violence to sustain or enrich themselves. They included both deserters and civilians who joined them, either opportunistically, or if war had made a settled existence unsustainable. Their depredations hindered military operations by consuming valuable resources, antagonising the local population, and undermining the authorities’ claims to be waging a legitimate war. Rulers’ periodic efforts to raise new regiments were in part to soak up these freebooters and impose their authority.Footnote44

Freebooters added to the uncertainty and confusion, and communities were often unsure of soldiers’ true identity – a problem already endemic in the later sixteenth century.Footnote45 Given their generally bad behaviour, all soldiers were regarded with suspicion. The prevailing customs euphemistically termed the ‘laws of war’ gave soldiers a sense of entitlement. For instance, communities which were taken after refusing a summons to surrender were considered free to be plundered. The imperialists’ ‘liberation’ of Werl in ducal Westphalia from Hessian occupation in 1636 cost the inhabitants 10,500 talers (hereafter tlr). Footnote46 Autonomous popular action was limited to taking revenge on isolated parties or stragglers.Footnote47 However, inhabitants could serve as guides and often accompanied raiding parties in return for a share in the plunder.Footnote48

Though winning ‘hearts and minds’ was rarely an important element of strategy, commanders recognised that unrestricted plundering and violence undermined the material basis upon which all belligerents depended. The relative fluidity of operations contributed to this, since reversals of fortune were frequent, obliging troops to shift their location at short notice. It made little sense to devastate an area into which one might wish to move or might be forced into. For example, mandates were issued forbidding the stealing or slaughtering of breeding animals, not only in areas under current control, but also those in enemy hands.Footnote49

Commanders of small war operations exhibited a similar spectrum as their subordinates. There were few prominent specialists, the most famous of whom was Johann Count Isolani (1586–1640) from Gorizia famed as a general of Croats in imperial service.Footnote50 A few officers rose to senior command thanks to demonstrating skill in small war, notably Jan van Werth (1591–1652), a peasant from the Grevenbroich area, a district in the duchy of Jülich. Having begun his career as a stable hand, he advanced successively through Spanish, Cologne, and Bavarian service to become an imperial baron and general of cavalry. Unlike Isolano, he also served in Westphalia, commanding the imperial and Liga forces there in 1642.Footnote51

Lothar Dietrich von Bönninghausen (1598–1658) provides a more common example. He was a minor Westphalian nobleman who was not particularly successful as a field commander but excelled at raising new regiments at a time when recruiting was often very difficult. He rose through service in line cavalry and infantry units, but between 1632 and 1640 was often tasked with leading small detachments in Westphalia and elsewhere across north-central Germany. His notoriety as a plunderer led to his dismissal in 1643 and temporary switch to French service in 1645–7.

Whereas all three examples were men who campaigned over wide areas in mobile warfare, others were compelled to pursue small war thanks to their appointment as commanders of isolated garrisons. Konrad Widerholt (1598–1667) is an extreme case. A Hessian who had entered Württemberg service, he was appointed commander of the Hohentwiel fortress, perched on a volcanic outcrop far from the duchy in southwest Germany, just as the pro-Swedish position in southwest Germany collapsed after the imperial victory at Nördlingen in 1634. He sustained himself and his men thanks to systematic raiding and hostage-taking in the surrounding area till 1648, despite three major attempts to capture his castle.Footnote52

A good example for Westphalia is Daniel Rollin de St André (1602–61) from Metz who joined Hessian service in 1634 having previously fought for the Swedes and was appointed commandant of Lippstadt which was crucial to sustaining Hessian regional influence. He features in the novel Simplicissimus by Hans Jacob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen (1621–76) which is celebrated as the primary literary reflection on the war. Though not published until 1669, it draws heavily on the author’s personal experience with Simplicissimus, the central character, following Grimmelshausen’s own trajectory from an adolescent servant with imperial dragoons, escaping the defeat at Wittstock (1636) and becoming St André’s servant. Aged around 15, Simplicissimus assumes the nom de guerre Jäger von Soest (Huntsman of Soest) named after a town around 10 km southwest of Lippstadt. The narrative stays relatively close to real events, though presents these in a distorted, alienated manner reflecting the postwar critique of undisciplined soldiery. The Huntsman displays the cunning, skill, and personal bravery, which were praised as attributes of successful small war commanders, whilst his desire for promotion leads him to reject piety and embrace the necessity to shed blood and transgress moral and societal norms. The latter aspect is presented unfavourably as part of Grimmelshausen’s reflection of the widespread disquiet caused by the war’s disruption of society, as well as his old soldier’s grumblings at unfair advancement.Footnote53 The Huntsman figure has become a local mascot, while Widerholt was celebrated as a folk hero into the twentieth century, indicating how the positive attributes of small warriors could become mythologised.

These forces could perform a secondary function by supporting major operations, or act as the primary strategic tool. The customary focus on large battles and sieges is reflected in the fuller coverage of the former rather than the latter role. However, supporting small war operations were far more common than the general narrative of military history suggests, because they accompanied largely unrecorded manoeuvres, which did not result in major engagements because one or other side avoided contact.

Support for major operations included actions intended to facilitate the movement of the main field army by scouting terrain and enemy positions, as well as those to degrade enemy capacity through the surprise or ambush of detachments or the interdiction of supply convoys. The same operation frequently combined both aspects, whether originally planned or not. Scouting was essential because senior commanders generally lacked maps. Topographical information was often simply handwritten lists of settlements in sequential order along known routes between major destinations. Local knowledge was therefore vital. Scouting was frequently combined with actions intended to confuse the enemy or screen the movement of the main army, such as the Hessians’ devastation of settlements along the Lower Rhine in October 1642.Footnote54 Such activity could flow seamlessly into attempts to hinder the enemy by denuding an area of resources.

Westphalia is an ideal case study since the general shortage of troops forced commanders to rely on small war as their primary strategic tool to contest control of territory which was both a means to sustain themselves and a core political objective. It also reflected the structural conditions of the war zone in which political and economic power were decentralised. Territory could not be controlled effectively from large urban centres, which were few and far between, whilst such locations threatened to consume precious manpower. Even a middling town of upwards of 5,000 inhabitants required 1,000 or more troops to hold it against a determined siege. A shortage of troops compelled the Swedes to hold Osnabrück with only around 600 men.Footnote55 The Cologne-Westphalian army totalled 2,000 cavalry and 14,000 infantry at the end of 1642 but held 38 towns and castles.Footnote56

The reluctance to tie up significant numbers of troops conflicted with the desire not to leave major centres unoccupied. Cologne’s neutrality proved convenient for the pro-Habsburg side during the 1620s because the city hired its own self-defence force, which repulsed the only attack it suffered during the war when the Swedes assaulted Deutz, its bridgehead on the east bank of the Rhine, in December 1632. This action rebounded badly for the assailants, by persuading the city council to shift to a more pro-Habsburg stance, whilst still paying for its own defence.Footnote57

Large garrisons relied on smaller ones to sustain them as even small towns were not self-sufficient and depended on access to food, firewood, and other essentials from the surrounding countryside. Smaller garrisons were posted along access routes to keep open lines of supply and communication, as well as offering a manpower pool, which could be drawn on to provide a relief force in case of attack. Other than Cologne, few towns had modern defences and most larger communities, like Münster, relied on adding bastions to their medieval walls.Footnote58 Secondary or tertiary settlements rarely possessed even these, relying instead on fences, ditches, and solid buildings like churches and storehouses. Isolated castles or manors offered little protection against serious attack but were still useful for securing highways or acting as a tripwire to warn of major enemy operations in the area.

Secondary settlements could have garrisons of up to 500 men, while those in tertiary posts could be as few as a dozen. Where possible, garrisons included at least some cavalry to extend their reach into the surrounding area through mounted patrols to detect threats and demonstrate mastery of the area to its inhabitants and encourage compliance with demands. Cavalry could also escort friendly artillery trains or supply convoys as they passed through a garrison’s area.

Garrisons served as bargaining chips in future peace negotiations, either to consolidate claims to permanent possession of an area, or to be relinquished in return for other concessions. In August 1635, Sweden’s senior officers forced its government to promise to include their substantial pay arrears in its political demands; a goal, which was eventually secured in the Peace of Westphalia. A congress at Nuremberg in 1649 arranged a phased withdrawal in return for incremental payments from local taxation to cover the arrears.Footnote59

More immediately, possession of district towns enabled armies to access the network of local officials upon whom they depended to secure money and supplies. Billeting and transit were nominally regulated by imperial law to which all belligerents paid more than lip service, given that they legitimated their goals as defence of the Empire’s constitution. Communities were supposed to be notified in advance of the arrival of troops who were obliged to promise good behaviour and pay for goods and services at agreed rates.Footnote60 Military ordinances specified pay and provision rates with, for example, the average monthly cost of an imperial infantryman fixed at just over 4tlr, compared to 11.5tlr for a horseman. These averages hide large variations according to rank, with regimental staff being particularly expensive, costing an average of 57 to 59tlr per person.Footnote61

A significant proportion of these costs were expected to be met in kind rather than cash. Armies acted like locusts, consuming vast quantities of food and drink in an age when agricultural surpluses were relatively small – even grain exporting regions consumed about 90% of production. The official daily requirements of a 1,000-man Cologne infantry regiment in 1631 comprised 6,000lb bread, 3,000lb meat, 40 barrels of beer, 1 of wine, 50 chickens, plus salt, oats, and other goods, in total costing 326tlr. Whereas soldiers might wait years for their pay, their bodily needs were immediate, and commanders knew that they would desert or disperse to plunder if they were not fed and watered. Christian’s quartermaster expected the bishopric of Münster to provide 200,000 two-pound loaves, 800 barrels of beer, and 100,000 litres of oats within two days in July 1623.Footnote62

Belligerents largely stopped paying soldiers regularly shortly after the war began, instead reserving their limited funds to purchase weaponry and service their ballooning debts. Soldiers’ maintenance was devolved to the areas where they operated to be met through ‘contributions’. These could be levied through threats of violence, such as those issued by Christian of Brunswick whose quartermaster euphemistically warned of ‘displeasure’ and the threat of forced billeting and ‘all other inconveniences’, whilst singeing the edges of the letters with a candle to signal the intention to burn down recalcitrant communities.Footnote63 Commanders preferred negotiated agreements, since this burdened local officials with enforcing payments, though the threat of military action remained omnipresent.Footnote64

Soldiers rarely received the official rates, but the ordinances did serve as a guide to what was considered appropriate to demand from inhabitants, while the sums help put the figures quoted in this paper into perspective. Initial demands were clearly a point of negotiation, as when Christian accepted 20,000tlr rather than the initial summons for 50,000tlr from ducal Westphalia in January 1622.Footnote65 Community leaders usually feared that failure to agree would prompt the soldiers to impose themselves anyway at a much higher cost. Commanders provided a ‘safeguard’ (Salvagarda) or promise not to take more and to prohibit other units in their army from seeking resources from the same area. These documents were often backed up by small detachments who, of course, were also to ensure the community paid up.Footnote66 Enforcement naturally proved harder when troops were on the move, and Christian’s army received little of what it demanded as it raced through Westphalia in summer 1623 in its futile attempt to escape the pursuing Liga army.Footnote67

These circumstances encouraged the proliferation of garrisons, not only in Westphalia, but also as a general characteristic of the war. The growing permanence of the inflated military presence encouraged the regularisation of contributions, which increasingly replaced normal taxes, with money no longer going to district and territorial treasuries, but instead directly to military officials and units at noticeably increased rates.Footnote68 The inability of either side to gain a military preponderance by December 1637 encouraged the imperial and Westphalian commanders to conclude a pact with their Hessian opponents to demarcate zones of extraction at the cost of the local inhabitants who were expected to pay higher contributions in return for both sides suspending raiding and reprisals.Footnote69

The agreement tacitly acknowledged that both parties realised that their incessant raiding was devastating and depopulating the region, while the Hessian senior officers knew their government was negotiating over possible acceptance of the Peace of Prague, which could involve switching to the emperor’s side. The initial agreement was soon extended with the imperialists hoping it would be the first step to peace, while the new Hessian ruler, Amelia Elisabeth (1602–51), wanted to buy time to bargain a better deal from France. Both sides nonetheless valued the truce. Paderborn town was taken by surprise in an unauthorised raid launched by St André’s Hessian garrison in Lippstadt, but was subsequently returned, though only after it had been thoroughly plundered.Footnote70 The truce reduced the incidence of raiding in eastern Westphalia but did not include the Swedes and was abandoned once Hessen-Kassel resumed offensive operations in 1639 in alliance with France.

Even when regulated, the military burden was reaching the limits of what could be sustained by that point. The letters of Münster’s privy council to its absentee master, Ferdinand of Cologne, repeatedly complain about the ‘impossibility’ of meeting demands even from their own forces, which in summer 1638 cost around 21,000tlr monthly, of which only 5,000 was intended for the two field regiments, and the remainder for seven garrisons.Footnote71 The district of Ahlen, which probably had around 2,000 inhabitants, suffered damage and other military costs totalling 203,380tlr 1633–49.Footnote72

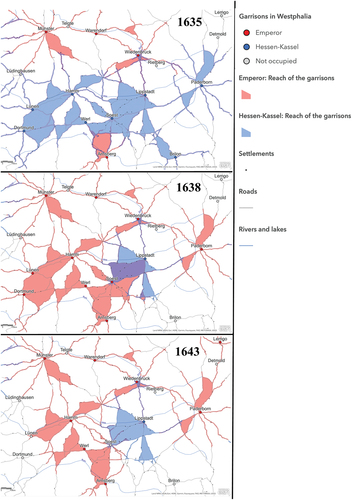

shows snapshots of the reach of soldiers stationed in garrisons in 1635, 1638 and 1643 for the district of Ahlen and some key towns nearby, such as Münster and Soest. The region features several garrisons held by the imperial and Hessian armies, with their daily reach shown shaded in red and blue respectively. The areas within daily reach are demarcated by the roads that can be seen as lines within the shaded space. Grey lines outside the shaded area show uncontrolled roads.

Figure 3. Maps showing the results of the spatial network analysis for the district of Ahlen and the surrounding area for 1635, 1638 and 1643.

The use of spatial network analysis allows for the identification of areas where multiple garrisons overlap. These areas are represented on the map by overlaps of multiple colour shadings. For example, the settlements around Wiedenbrück and Lippstadt could be reached within a day by raiding parties from multiple garrisons controlled by both armies. Comparing the situation in 1635 and 1638, the local position of the Hessians weakened as they lost control of seven garrisons while the imperial army gained six. One of those lost garrisons was Soest, which provided access to 48 settlements and control over several vital roads leading to other larger towns. Although the Hessian army maintained its control over Lippstadt in 1638, the garrison’s reach overlapped with other garrisons exposing the civilians to potential raids from multiple directions. Soest’s example highlights the advantage of our mapping approach over a textual description or traditional maps. The significance of the Hessians’ loss of Soest in 1638 is strikingly revealed, as is the imperialists’ ability to maintain their position in the area through possession of surrounding settlements despite losing the same town subsequently.

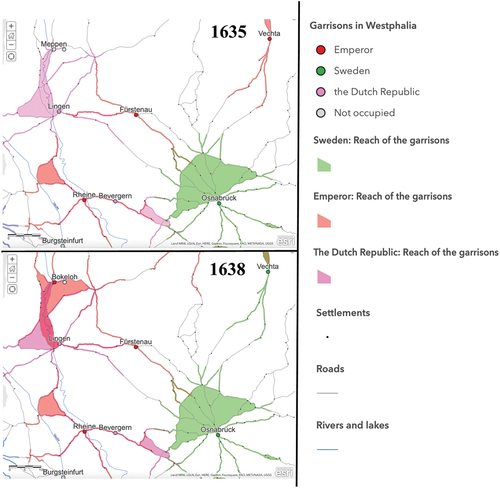

Other locations also experienced overlapping reach of multiple garrisons and changes in garrisons’ control. For example, the settlements near Meppen and Lingen were likely exposed to the raids of Dutch (shown in pink) as well as imperial soldiers in 1638 (see ). Comparison of the situations in 1643 and 1648 highlights the changes after Osnabrück was declared as a neutral venue for peace negotiations. The Swedes (shown in green) gained Fürstenau and regained Vechta, both previously controlled by the imperial army (shown in red). Although those were important gains, they could not compensate for the loss of the strategically valuable Osnabrück that provided access to 40 settlements and control over several important roads. In comparison, the garrisons in Vechta and Fürstenau gave access to 16 and six settlements, respectively. Their position with respect to the road network was also less prominent than Osnabrück’s.

Figure 4. Spatial network analysis for the area around Meppen and Osnabrück for 1635, 1638, 1643 and 1648.

Control of territory was the prerequisite for any offensive action, unless large numbers were to hand to facilitate a full-scale invasion as was the case with the Swedes and their allies entering Westphalia late in 1631. Most offensives were limited to rapid sorties to capture one or more enemy outposts. Flying columns were assembled by drawing out garrisons along the route to the objective and moved rapidly, usually without artillery. Attacks relied heavily on surprise or used ruses, as in Christian’s capture of Lippstadt at New Year 1622. If these failed, attackers could escalate the devastation of the surrounding area to encourage inhabitants to pressure the garrison into accepting the offer of a free passage to their nearest friendly outpost. Initial success could produce a snowball effect, where the capture of one post discouraged others from offering serious resistance. Discretion could easily appear the better part of valour, particularly as defenders could often count on the arrival of field troops in the following spring or autumn to provide an opportunity to recover their lost outposts. The local strategic balance thus oscillated regularly across the last seventeen years of war.

Offensives could involve what were, in regional terms, substantial numbers. Höxter was allegedly besieged by 10,000 imperialists who took it by storm in April 1634.Footnote73 Raiding parties were much smaller at around 60 to 400 men and were more concerned with seizing or destroying resources than capturing positions. Hostage taking was a routine practice, either to ensure fulfilment of contribution demands, or simply to profit. The usual targets were mayors, estate stewards, bailiffs, and other local officials, as well as nobles with some families suffering repeatedly.Footnote74 Larger numbers of captives could be forced to ransom themselves, with the 300 Hessian soldiers, 220 burghers, and 1,000 refugees taken at Höxter in 1634 each being required to pay 100-800tlr to be set free.

Raiding primarily seized movable goods and livestock. Threatened or actual violence was applied to coerce inhabitants, especially to hand over valuables and reveal where more might be hidden. The growing literature on the experience of the war indicates the contextual character of violence, as well as how victims were selected. Rape was underreported, yet clearly featured, including on a mass scale during the Swedish invasion in April 1646.Footnote75 Wanton destruction occurred when raiders met resistance or did not intend to return. Usually, the outskirts of communities suffered most as raiders burned and plundered. Destruction could be extensive as in Ahlen’s case when a certain ‘Colonel Horstmeister’ raided the town in 1636 and burned 80 houses, worth 41,000tlr.Footnote76

Conclusions

Westphalia’s example shows that the belligerents in the Thirty Years War employed their own form of small war which drew directly on practices already common in late sixteenth-century conflicts, rather than from learned treatises. Small war was integral to how hostilities were conducted, rather than specifically selected as some Fabian strategy of attrition. It was crucial to how the war was sustained and objectives pursued. The relatively high levels of destruction should not mislead us into dismissing these operations as meaningless violence perpetrated by freebooting mercenaries, as represented in innumerable clichés of the war. Not only did commanders employ these methods with a purpose, but they were usually at pains to keep the accompanying violence within bounds so as not to undermine discipline and effectiveness, and to preserve their claims to be waging a just war.

The ambiguities of small war could also serve these goals, as the frequent difficulty of identifying those involved created ‘plausible deniability’ for atrocities, which could be exploited where necessary to preserve the fiction of honourable warmaking. Despite its characterisation as a ‘religious war’, the conflict did not preclude dialogue between belligerents, and with the inhabitants of occupied areas. Soldiers profited when they could, but they also broadly recognised the dangers of cutting off the hands that fed them. These concerns influenced the mutually agreed demarcation of zones of control agreed in 1637. Finally, the application of mapping techniques allows the otherwise disparate local stories to be placed in context and related to the war’s wider dynamic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Peter H. Wilson

Peter H. Wilson is the Chichele Professor of the History of War at the University of Oxford, a Fellow of All Souls College, and Principal Investigator of a research project on the ‘European Fiscal-Military System 1530-1870’ funded by the European Research Council (2018-25). His books have been translated into Chinese, German, Italian, Japanese, Macedonian, Polish, and Spanish, and include Iron and Blood: A Military History of the German-speaking Peoples since 1500 (2022), The Holy Roman Empire: A Thousand Years of Europe’s History (2016), and Europe’s Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years War (2009).

Katerina Tkacova

KaterinaTkacova is a researcher at the Global Security Programme at the University of Oxford. Her research focuses on the dynamics of contemporary and historical armed conflicts. Her work combines visualisation techniques with data analysis.

Thomas Pert

Thomas Pert is a Leverhulme Trust Early Career Fellow based at the University of Warwick. He is a historian of early modern British and European history, and his current research project focuses on the experiences of refugees during the Thirty Years’ War.

Notes

1. Schmidt, Die Reiter der Apokalypse; Wilson, Europe’s Tragedy; Gantet, ‘Guerre de Trente Ans’.

2. Picaud-Monnerat, La petite guerre; Kunisch, Der kleine Krieg; Rink, Vom ‘Partheygänger’ zum Partisanen and his ‘The Partisan’s Metamorphosis’.

3. Bäckström, ‘Snapphanar and Power States’, 19–20 contrary to Deruelle, ‘Sixteenth-Century Antecedents’.

4. Fonck and Satterfield. ‘The Essence of War’; Satterfield, Princes, Posts, and Partisans; Dosquet, ‘Le feu et l’encre’.

5. Bäckström, ‘Snapphanar and Power States’

6. Weigley, Age of Battles.

7. Rodgers, ed. The Military Revolution Debate.

8. Wilson and Gantet, ‘Battlefields, Images and Cultures’ 81–82.

9. This has been re-emphasised in the latest and most detailed study of the impact of the war in Bavaria: Haude, Coping with Life. See also Kreike, Scorched Earth 97–136 for the Low Countries.

10. An important exception is the extensive and valuable collection relating to the imperial field marshal Melchior von Hatzfeldt edited by Günther Engelbert, Das Kriegsarchiv.

11. Wolfthal, ‘Jacques Callot’s Miseries’; Gantet and Wilson, ‘Les images des batailles’.

12. For example, the 24-page manuscript record of events in Höxter 1617–40 in Landesarchiv Münster (hereafter LAM) A295 Nr.1485, also printed from another copy in Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 90–105. Numerous other examples also in Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten.

13. LAM A58 Nr.271.

14. Data on the historical roads and settlements come from Holterman et al., ‘Viabundus Map of Premodern European Transport and Mobility’. For the information on garrisons, we rely on Salm, Armeefinanzierung, as well as archival data. This data is incorporated into and 4.

15. We use a similar approach as Tao et al., ‘A Hybrid Approach to Modeling Territorial Control in Violent Armed Conflicts’

16. Ohler, The Medieval Traveller, 101.

17. We assigned travel difficulty based on the following weights for speed. The weights loosely follow Tobler’s calculations on the impact of slope on the travel speed (see, for example, Tobler, Three Presentations on Geographical Analysis and Modeling). Given the different speeds per slope, we adjusted the distance that was possible to travel for a soldier on a horse within the day so the roads leading through areas with a higher slope decreased the travel distance. See the project GitHub page for more details: https://github.com/katerina-tkacova/Mapping-TYW-small-war.

18. Merian, Topographia Westphaliae.

19. Foerster, Kurfürst Ferdinand; Kaiser, “Der Krieg in der ‘Wetterecke’.

20. Bartz, Köln im Dreißigjährigen Krieg; Lewejohann ed., Köln in unheiligen Zeiten.

21. Kaiser, ‘Die vereinbarte Okkupation’; Rutz, ed. ‘Krieg und Kriegserfahrung’; Sodmann, ed. 1568–1648.

22. Morris, ‘Borderlands and Fatherlands’

23. Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 22–30, 249–264, 267–268. Lahrkamp, ‘Kölnisches Kriegsvolk’; Tessin and Behr, ‘Beiträge zur Formationsgeschichte’.

24. Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 18–36, 190–199, 449–453; Teske, Bürger, Bauern, Söldner, 51–58; Weskamp, Herzog Christian 47–88; Smid, Tolle Halberstädter.

25. Brunink, Mansfeld in Ostfriesland.

26. Flieger, Stadtlohn, Söbbing, Stadtlohn, Krüssmann, Mansfeld 460–473

27. Cañete, Los Tercios de Flandres 334–343.

28. Weiand, ‘Schweden und Hessen-Kassel’; Helfferich, The Iron Princess, and the documents in Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 43–62, 118–122. Operations are covered in Teske Bürger, Bauern, Söldner 93–121; Lahrkamp ’Bönninghausen’ pp.278–295.

29. Foerster, Kurfürst Ferdinand 157–171.

30. Foerster, Kurfürst Ferdinand 176–185, 196–205, 222–265; Salm, Armeefinanzierung 83–95; Schulze, Reichskreise im Dreißigjährigen Krieg 453–90, and the documents in Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 86–88, 89–94, 115–117, 125–127.

31. Leffers, Die Neutralitätspolitik des Pfalzgrafen; Ehrenpreis, Krieg im Herzogtum Berg.

32. Engelbert, ‘Hessenkrieg am Niederrhein’ 68–77.

33. Ibid 35–96; See generally Teske, Bürger,Bauern, Söldner 123–149.

34. Bäckström, ‘Snapphanar and Power States’ 128–140.

35. Foerster, Kurfürst Ferdinand, 271–299.

36. Examples of imperial demands in Haus-, Hof-, und Hofarchiv Vienna (hereafter HHStA), KA 94 (neu) 30 Jan.1638, 12 Nov.1638. Examples of appeals for mitigation of burdens include those from the abbess of Herford: LAM A230 Nrs.24, 51, and 61.

37. Weise, ‘Gewaltprofis und Kriegsprofiteure’, and his ‘Grausame Opfer?’; Gajecky and Baran, Cossacks.

38. Beaufort-Spontin, Harnisch und Waffe 80–94.

39. LAM A58 Nr.70.

40. LAM A295 Nr.1485 narrative, also printed in Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 91.

41. Wilson, ‘Total War’

42. Bäckström, ‘Snapphanar and Power States’

43. Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 63, 66–68.

44. Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 268–269, 354–356.

45. Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 55; Morris, ‘Borderlands and Fatherlands’.

46. Conrad and Teske (eds.), Sterbezeiten, 165.

47. Examples in Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 51–53, 312–314.

48. Examples in Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 53–55, 326–330; Wiese, ‘Gewaltprofis und Kriegsprofiteure’ 288.

49. Conrad and Teske (eds.), Sterbezeiten, 307–8. See also Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 203–204.

50. Schmidt-Brentano, Die Kaiserlichen Generale, pp.239–241.

51. Ibid pp.532–540; Lahrkamp, Jan van Werth.

52. Fritz, ‘Widerholt’.

53. The relevant section runs from Book 2 Chapter 19 to Book 4 Chapter 1. Discussion in Kaiser, ‘Der Jäger von Soest’; Teske, Bürger, Bauern, Söldner 128–130.

54. HHStA KA Fasz.110 (neu) General Wahl to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm 4 Oct.1642.

55. Pleiss, ‘Finnen und Lappen’

56. Salm, Armeefinanzierung 61; Lahrkamp, Jan von Werth 125–131.

57. Bartz, Köln im Dreißigjährigen Krieg 97–99.

58. See the 1636 illustration of Münster in Galen ed., 30jähriger Krieg I 120–121, II 13, and the contemporary engravings of Westphalian towns and villages in Merian, Topographia Westphaliae.

59. Oschmann, Der Nürnberger Exekutionstag.

60. See the formal notification from Duke Georg of Lüneburg of the imminent arrival of his forces in Corvey, 21 August 1624, in LAM A295 Nr.228.

61. LAM A58 Nr.273. Liga rates from 1631 are printed in Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 265–266, while Hessian rates from 1635 are in Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 163–165.

62. LAM A58 Nr.10; Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 305–306.

63. An example in LAM A58 Nr.10 25 July 1623 (Old Style).

64. Examples in LAM A58 Nr.67 complaint to the bishop of Münster 26 Nov.1636; Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 158–161.

65. Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 66–68.

66. See the Salvagarda issued by Tilly, the Liga commander, for Corvey on 6 Jan.1624 LAM A295 Nr.228. Further documents in Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 270–275, 300–304.

67. Flieger, Stadtlohn 159–160.

68. Examples in Conrad and Teske eds., Sterbezeiten 280–293.

69. Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 166–169; Foester, Kurfürst Ferdinand 144–156.

70. HHStA KA Fasz. 94 (neu) General Velen’s report 1 May 1638.

71. LAM A58 Nr.278.

72. LAM A58 Nr.271; Mayr, Ahlen in Westfalen 19–23.

73. LAM A295 Nr.1485 narrative, also printed in Neuwöhner ed., Im Zeichen des Mars 96.

74. Examples in Conrad and Teske eds. Sterbezeiten 47–48, 141–143, 296–7, 331–341.

75. Ibid 50. For the experience of war, see Haude, Coping with Life.

76. LAM A58 Nr.271.

References

- Archival sources in the Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv Vienna (HHStA) and Landesarchiv Münster (LAM)

- Bäckström, Olli. “Snapphanar and Power States: Insurgency and the transformation of War in Sweden and Denmark 1643-1645.” PhD, University of Eastern Finland, 2018.

- Bartz, Christian. Köln im Dreißigjährigen Krieg. Peter Lang: Frankfurt am Main, 2005.

- Beaufort-Spontin, Christian. Harnisch und Waffe Europas. Die militärische Ausrüstung im 17. Jahrhundert. Munich: Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1982.

- Brunink, Wolfgang. Der Graf von Mansfeld in Ostfriesland (1622–1624). Aurich: Ostfriesisches Landschaft, 1957.

- Cañete, Hugo Alvaro. Los Tercios de Flandes en Alemania: La Guerra del Palatinado 1620-1623. Malaga: Ediciones Salamina, 2014.

- Claire, Gantet, and Peter H. Wilson. “Les images des batailles de la guerre de Trente Ans (1618-1648) : témoignages, preuves, mémoires.” Dix-Septième Siècle n° 299, no. 2 (2023): 229–251. doi:10.3917/dss.232.0225.

- Conrad, Horst. Sterbezeiten. Der Dreißigjährige Krieg im Herzogtum Westfalen, eds. Gunnar Teske. Münster: Landschaftsverband Westfalen, 2000.

- Deruelle, Benjamin. “The Sixteenth-Century Antecedents of Special Operations ‘Small War’.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 25, no. 4 (2014): 754–766. doi:10.1080/09592318.2013.832924.

- Dosquet, Emilie. “Le feu et l’encre: La ‘désolation du Palatinat’. Guerre et information politique dans l’Europe de Louis XIV.” PhD Paris Sorbonne, 2017.

- Ehrenpreis, Stefan, ed. Der Dreißigjährigen Krieg im Herzogtum Berg und seinen Nachbarregionen. Schmidt: Neustadt an der Aisch, 2002.

- Engelbert, Günther. “Der Hessenkrieg am Niederrhein.” Annalen des Historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein 161, (1959): 65–113. 65-113, and 162 (1960): 35-96. doi:10.7788/annalen-1959-161-jg03.

- Engelbert, Günther, ed. Das Kriegsarchiv des kaiserlichen Feldmarschalls Melchior von Hatzfeldt (1593-1658). Düsseldorf: Droste, 1993.

- Flieger, Hans E. Die Schlacht bei Stadtlohn am 6. August 1623. Aachen: Shaker, 1998.

- Foerster, Joachim F. Kurfürst Ferdinand von Köln. Die Politik seiner Stifter in den Jahren 1634-1650. Münster: Aschendorff, 1976.

- Fonck, Benjamin, and George Satterfield. “The Essence of War: French Armies and Small War in the Low Countries (1672-1697).” Small Wars & Insurgencies 25, no. 4 (2014): 767–783. doi:10.1080/09592318.2013.832926.

- Fritz, Eberhard. “Konrad Widerholt, Kommandant der Festung Hohentwiel (1634-1650).” Zeitschrift für Württembergische Landesgeschichte 76 (2017): 217–268. doi:10.53458/zwlg.v76i.569.

- Gajecky, George, and Alexander Baran. The Cossacks in the Thirty Years War. 2 vols. Rome: Basiliani, 1969-83.

- Galen, Hans, ed. 30jähriger Krieg, Münster und der Westfälische Frieden. 2 vols. Münster: Stadtmuseum Münster, 1998.

- Gantet, Claire. “Guerre de Trente Ans et Paix de Westphalie: Un bilan historiographique.” Dix-septième siècle 277, no. 4 (2017): 645–666. doi:10.3917/dss.174.0645.

- Haude, Sigrun. Coping with Life During the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). Leiden: Brill, 2022. doi:10.1163/9789004467385.

- Helfferich, Tryntje. The Iron Princess: Amelia Elisabeth and the Thirty Years War. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674074668.

- Holterman, Bart. ed. Viabundus Pre-Modern Street Map 1.2 (Released 21-9-2022). https://www.viabundus.eu

- Kaiser, Michael. “Der Krieg in der ‘Wetterecke der europäischen Politik’: Kurköln und die Kriegführung der Liga unter dem Feldherrn Tilly (1621-1630).” Zeitschrift des Bergischen Geschichtsvereins 98 (1997/98): 29–66.

- Kaiser, Michael. “Der Jäger von Soest. Historische anmerkungen zur Darstellung des Militärs bei Grimmelshausen.” In 93118. .” In Grimmelshausen und Simplicissimus in Westfalen edited by Peter Heßelmann, 93-118. Bern: De Gruyter, 2006 93–118.

- Kaiser, Michael. “Die vereinbarte Okkupation. Generalstaatische Besatzungen in brandenburgischen Festungen am Niederrhein.” In Grimmelshausen und Simplicissimus in Westfalen, edited by Heßelmann Peter, 93–118. Berlin: De Gruyter, Bern, 2006.

- Kreike, Emmanuel. Scorched Earth. Environmental Warfare as a Crime Against Humanity and Nature. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021. doi:10.1515/9780691189017.

- Krüssmann, Walter. Ernst von Mansfeld (1580–1626). Grafensohn, Söldnerführer, Kriegsunternehmer gegen Habsburg im Dreißigjährigen Krieg. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2010. doi:10.3790/978-3-428-53321-3.

- Kunisch, Johannes. Der kleine Krieg. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner, 1973.

- Lahrkamp, Helmut. “Lothar Dietrich Frhr. von Bönninghausen. Ein westfälischer Söldnerführer des Dreißigjährigen Krieges.” Westfälische Zeitschrift 108 (1958): 239–366.

- Lahrkamp, Helmut. “Die Kriegserinnerungen des Grafen Gronsfeld (1598-1662).” Zeitschrift des Aachener Geschichtsvereins 71 (1959): 77–104.

- Lahrkamp, Helmut. “Kölnisches Kriegsvolk in der ersten Hälfte des Dreißigjährigen Krieges.” Annalen des Historischen Vereins für den Niederrhein 161 (1959): 114–145. doi:10.7788/annalen-1959-161-jg04.

- Lahrkamp, Helmut. Jan von Werth. Cologne: CologneDer Löwe, 1962.

- Leffers, Renate. Die Neutralitätspolitik des Pfalzgrafen Wolfgang Wilhelm als Herzog von Jülich-Berg in der Zeit von 1636-1643. Neustadt an der Aisch: Schmidt, 1971.

- Lewejohann, Stefan, ed. Köln in unheiligen Zeiten. Die Stadt im Dreissigjährigen Krieg. Cologne: Böhlau, 2014. doi:10.7788/boehlau.9783412217938.

- Mayr, Alois. Ahlen in Westfalen. Siedlung und Bevölkerung einer industriellen Mittelstadt mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der innerstädtischen Gliederung. Schöningh: Ahlen, 1968.

- Merian, Matthäus. Topographia Westphaliae. Matthäus Merian: Frankfurt am Main, 1647.

- Morris, Louis. Borderlands and Fatherlands: ‘Foreign’ Soldiery in the Holy Roman Empire, 1576-1618. PhD thesis University of Oxford, 2022.

- Neuwöhner, Andreas. Im Zeichen des Mars. Quellen zur Geschichte des Dreißigjährigen Krieges und des Westfälischen Friedens in den Stiften Paderborn und Corvey. Cologne: Bonifatius, 1998.

- Ohler, Norbert. The Medieval Traveller. New ed. Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2010.

- Oschmann, Antje. Der Nürnberger Exekutionstag 1649-1650. Das Ende des Dreißigjährigen Krieges in Deutschland. Münster: Aschendorff, 1991.

- Parrott, David. The Business of War. Military Enterprise and Military Revolution in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139023337.

- Picaud-Monnerat, Sandrine. La petite guerre au xviiie siècle. Paris: Économica, 2010.

- Pleiss, Detlev Heinrich. “‘Finnen und Lappen’ in Stift und Stadt Osnabrück 166-1643.” Osnabrücker Mitteilungen 93 (1990): 41–94.

- Rink, Martin. Vom ‘Partheygänger’ zum Partisanen. Die Konzeption des kleinen Krieges in Preußen 1740-1813. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1999.

- Rink, Martin. “The Partisan’s Metamorphosis: From Freelance Military Entrepreneur to German Freedom Fighter, 1740 to 1815.” War in History 17, no. 1 (2010): 6–36. doi:10.1177/0968344509348291.

- Rodgers, Clifford, ed. The Military Revolution Debate: Readings on the Military Transformation of Early Modern Europe. Boulder: Westview, 1995.

- Rutz, Andreas, ed. Krieg und Kriegserfahrung im Westen des Reiches 1568-1714. Göttingen: V&R Unipress, 2016. doi:10.14220/9783737003506.

- Salm, Hubert. Armeefinanzierung im Dreißigjährigen Krieg. Der Niederrheinisch-Westfälischen Reichskreis 1635-1650. Münster: Aschendorff, 1990.

- Satterfield, George. Princes, Posts, and Partisans. The Army of Louis XIV and Partisan Warfare in the Netherlands (1673-1678). Leiden: Brill, 2003. doi:10.1163/9789047402411.

- Scheipers, Sybille. “Counterinsurgency or Irregular Warfare? Historiography and the Study of ‘Small Wars’.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 25, no. 5–6 (2014): 879–899. doi:10.1080/09592318.2014.945281.

- Schmidt, Georg. Die Reiter der Apokalypse: Geschichte des Dreißigjährigen Krieges. Munich: C.H. Beck, 2018. doi:10.17104/9783406723391.

- Schmidt-Brentano, Antonio. Die Kaiserlichen Generale 1618-1655. Ein biographisches Lexikon. Vienna: Österreichisches Staatsarchiv, 2022.

- Schulze, Fabian. “Die Reichskreise im Dreißigjährigen Krieg”. Kriegsfinanzierung und Bündnispolitik im Heiligen Römischen Reich deutscher Nation Berlin: De Gruyter. (2018). 10.1515/9783110558739.

- Smid, Stefan, and Sascha Lunyakov. Der Tolle Halberstädter Christian von Braunschweig. Kriegsunternehmer, sine Heer und seine Feldzüge. Berlin: Zeughaus, 2011.

- Söbbing, Ulrich. Die Schlacht im Lohner Bruch bei Stadtlohn am 6. August 1623. Stadtlohn: Heimatverein und Stadt Stadtlohn, 1998.

- Sodmann, Timothy, ed. Zu den Auswirkungen des Achtzigjährigen Krieges auf die östlichen Niederlande und das Westmünsterland. Vreden: Landeskundliches Institut Westmünsterland, 1568-1648 2002.

- Tao, Ran, Daniel Strandow, Michael Findley, Jean-Claude Thill, and James Walsh. “A Hybrid Approach to Modelling Territorial Control in Violent Armed Conflicts.” Transactions in GIS 20, no. 3 (June 2016): 413–425. doi:10.1111/tgis.12228.

- Teske, Gunnar. Bürger, Bauern, Söldner und Gesandte. Der Dreißigjährige Krieg und der Westfälische Frieden in Westfalen. Münster: Ardey Verlag, 1998.

- Teske, Gunnar, ed. Dreißigjähriger Krieg und Westfälischer Friede. Münster: Vereinigten Westfälischen Adelsarchiv, 2000.

- Tessin, Georg, and Hans-Joachim Behr. “Beiträge zur Formationsgeschichte des Münsterischen Militärs.” Westfälische Forschungen 32 (1982): 83–111.

- Tobler, Waldo. “Three Presentations on Geographical Analysis and Modeling.“ National Center for Geographic Information and Analysis, no. 93 (1993): 1–25.

- Weiand, Kerstin. “Schweden und Hessen-Kassel: Denk- und Handlungsräume einese schwedischen Verbündten.” In Mit Schweden verbündet – von Schweden besetzt, edited by Inken Schmidt-Voges and Nils Jörn, 33–58. Hamburg: Verlag Dr Kovac, 2016.

- Weigley, Russell F. The Age of Battles: The Quest for Decisive Warfare from Breitenfeld to Waterloo. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991.

- Weise, Michael. “Gewaltprofis und Kriegsprofiteure. Kroatische Söldner als Gewaltunternehmer im Dreißigjährigen Krieg.” Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 68 (2017): 278–291.

- Weise, Michael. “Grausame Opfer? Kroatische Söldner und ihre unterschiedlichen Rollen im Dreißigjährigen Krieg.” In Zwischen Tätern und Opfern, edited by Philipp Batelka, Michael Weise, and Stephanie Zehnle, 127–148. Göttingen: V&R, 2017. doi:10.13109/9783666300998.127.

- Weskamp, Albert. Herzog Christian von Braunschweig und die Stifter Münster und Paderborn im Beginne des Dreißigjährigen Krieges (1618-1622). Paderborn: Schöningh, 1884.

- Wilson, Peter H. Europe’s Tragedy. The Thirty Years War. London: Allen Lane, 2009.

- Wilson, Peter H. “Was the Thirty Years War a ‘Total War’?” In Civilians and War in Europe 1640-1815, edited by Eve Rosenhaft, Erica Charters, and Hannah Smith, 21–35. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2012. doi:10.5949/UPO9781846317699.002.

- Wilson, Peter H., and Claire Gantet. “Battlefields, Images and Cultures of Remembrance in the Thirty Years War.” In The Battlefield After the Battle: Memories and Uses, edited by Catherine Denys, Gilles Malandin, and Jean de Préneuf, 62–91. Lille: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion, 2022.

- Wolfthal, Diane. “Jacques Callot’s Miseries of War.” The Art Bulletin 59, no. no.2 (1977): 222–233. doi:10.1080/00043079.1977.10787407.