ABSTRACT

Research has shown that the counterinsurgent proposition of ‘winning Hearts and Minds’ is more complex than building a road. This paper examines how project workers in three infrastructure projects in Colombia sought community support not for military intelligence or to improve government-community relations, but to intervene with armed groups on the project’s behalf. The findings highlight the role of community institutions in negotiating between two actors – rather than being ‘won over’ by either. This paper also indicates the limitations of community agency in the face of changing local orders, questioning the local empowerment of goods delivery in conflict areas.

Introduction

In an office in Bogota, I sit across the table from a former Minister of Transport. He explains that the construction of infrastructure – roads, electrical grids, dams, bridges, pipes – provokes attacks by armed groups against both communities and construction companies, requiring the military ‘to manage this public disorder’.Footnote1 This may be due to the supposedly counterinsurgent nature of these projects: Zeiderman observes that since the mid-20th century, public works in rural and isolated territories in Colombia ‘were conceived as antidotes to insurgency’ against groups such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) or National Liberation Army (ELN), winning the ‘Hearts and Minds’ of civilians away from armed groups and towards the state.Footnote2

However, closer examination of public goods delivery and ‘Hearts and Minds’ reveals cracks in the efficacy and legitimacy of the strategy. Extensive literature highlights how such programmes are often counterproductive,Footnote3 presume the idea of an overly simplistic legitimacy marketplace’ where local communities allocate their loyalty to the highest bidder,Footnote4 and may be prescriptive and imperialistic in its approach.Footnote5 So if its counterinsurgent credentials are so dubious, what – if any – is the value of civilian support in the construction of infrastructure in conflict areas?

I argue that project workers – engineers, managers, contractors, and public officials – perceive a strategic value in gaining civilian support during the construction of the infrastructure project. Rather than try to win civilian loyalty away from armed groups, project workers rely on their relationship to navigate complex security environments so that civilians will intervene with armed groups on the project’s behalf. However, the ability of civilians to exert influence is affected by fluctuations in the local order.

I examine three cases of infrastructure in Colombia: the construction of tertiary roads and schools in the municipality of Leiva (Nariño), of a secondary road in the municipality of Barbacoas (Nariño), and of a hydroelectric dam in the municipality of Chaparral (Tolima). Despite variation in type of infrastructure and location, project workers in all three cases viewed the community’s relationship to the armed group as a source of security. Project workers appealed to the Communal Action Councils (Juntas de Accion Comunal - JAC), indigenous councils (cabildos) or afro-Colombian community councils (consejos comunitarios)Footnote6 to negotiate with armed actors, including the FARC, ELN, and neoparamilitary groups.

This capacity to negotiate was affected by changes in the local order between the armed group and the military. Where the state showed little interest in securing the project at all, armed groups had fewer incentives to adhere to community needs. When the state elected to remove the armed group out by force, the resulting confrontations robbed civilians of direct influence. However, these cases indicate that when the state and armed group reached a ‘tacit coexistence’,Footnote7 civilian institutions took a central role in negotiating the shared presence of project workers and the armed group in the territory.

To demonstrate the important – but limited – role of civilian institutions in infrastructure construction, I first review the research on counterinsurgency, public goods delivery and aid, and local orders. I discuss the data collection process, including case selection, methods, and ethical considerations. I then present the findings, tracing the construction of the three projects and the strategies used by project workers in ‘winning’ community support. Finally I discuss how these cases inform our understanding of infrastructure and counterinsurgency, further questions, and the importance of putting local agency and it’s limitations at the heart of public goods delivery in conflict areas.

The centrality of community support

The road to winning civilian support requires more than the road itself. In Afghanistan, Kilcullen argues that counterinsurgent success emerges when people use the ‘process of the road construction … as a framework around which to organise a full spectrum strategy … to separate insurgents from the people’, rather than just rely on providing the road itself.Footnote8 Colombian policies in the 1950s and 1960s sought to empower local organisations such as the JACs as a bulwark against FARC advancement.Footnote9 Developed alongside Plan Lazo, this approach put locally-geared public goods delivery at the heart of its counterinsurgent strategy,Footnote10 including infrastructure provision.Footnote11 JACs, along with the later creation of consejos comunitarios and cabildos, brought marginalised communities into the political system: a rationale best characterised as ‘decentralize to pacify’.Footnote12 As Rempe observes, this approach was intended to help ‘security forces overcome ‘the traditional suspicion of the military held by the people in violent regions’, improving intelligence and support for internal security operations”’.Footnote13 Kalyvas terms this support defection, where one actor seeks to ‘maximize the support they receive from that population and minimize the support that rival groups receive from the same population’ through a variety of instruments, not all violent.Footnote14

Ironically, as Gutierrez argues, this attempt to win over communities in Colombia did not go as planned, as civilian institutions often became so close to the FARC that ‘even the state’ knew about the relationship.Footnote15 This raises questions about the efficacy of this locally-geared Hearts and Minds approach. For example, in neighbouring Peru the Fujimori government created the FONCODES programme to empower local communities through infrastructure construction to improve relations with the state and prevent the further ‘insertion’ of insurgent groups.Footnote16 However, Palmer observes that FONCODES only resulted in temporary empowerment during the project’s construction and only superficial improvement in local-government relations.Footnote17 Sexton and Zurcher’s recent examination of locally-geared infrastructure projects in Afghanistan also demonstrates that these projects had little effect on the presence of armed groups, and that robust consultation with local communities only prevented negative attitudes towards the state, rather than improving government-community relations.Footnote18

Therefore if the objectives of ‘winning Hearts and Minds’ appear largely unsuccessful, why would project workers continue to appeal to local communities during infrastructure construction? To answer this, I turn to the literature on humanitarian work in conflict areas. Civilians may choose a myriad of ways to react to aid projects, either by actively opposing and threatening the project, tolerating it, or promoting and acting on the project’s behalf.Footnote19 Breslawski examines the third option, where aid workers access difficult territories in conflict areas by ‘winning over’ the community so that they intervene with armed groups on behalf of the project.Footnote20 The strategy appears anecdotally in aid work done in Somalia, Afghanistan, and Syria,Footnote21 yet this negotiated dynamic is still underexplored. As Breslawski argues, ‘community acceptance has received scant attention in the academic world, despite the fact that community acceptance has emerged as one of the strongest factors in determining humanitarian security and access’.Footnote22

Many project workers in Colombia view the local communities as more important to their security in conflict areas than the military, even if their governmental roles are more charged than ‘neutral’ humanitarian organisations.Footnote23 A senior official in Bogota explained that ‘it is not recommended [to enter with the military] … Because when they leave, things will be worse. And the [armed] groups will then understand the project as a military objective’.Footnote24 An engineer working in another municipality of Nariño also argued that ‘the army did not provide security, the community did’.Footnote25 This approach often put project workers at odds with other branches of government, as the Colombian government since Uribe in the 2000s has prioritised military protection of infrastructure construction.Footnote26

Therefore project workers often build infrastructure in the midst of rapidly changing local orders between the military and armed groups. Drawing from strategies of ‘community acceptance’ in the humanitarian literature, but recognizing the intersection of goods delivery and counterinsurgency, I examine how community support becomes most valuable when the local order resembles what Staniland refers to as a ‘tacit coexistence’. This dynamic occurs when neither the state nor armed groups is confident in securing the territory militarily.Footnote27 Therefore, the role of civilian institutions becomes crucial in negotiating project workers’ safety.

Case selection and research designFootnote28

To explore the role of community support in infrastructure construction during conflict, I took a grounded approach in a two-phase data collection in Colombia.Footnote29 Colombia has a comparatively low-level international intervention in its statebuilding processes.Footnote30 This means that project workers are usually directly associated with the state, such as the three engineers I first interviewed at a government agency in Bogota. I used these interviews to identify how project workers valued community support. I then conducted in-depth fieldwork on different infrastructure projects in Nariño with 25 interviews with local leaders, project workers, and international observers in early 2019.

Bearing in mind the ‘ethical imperative of research’ in conflict zones,Footnote31 I paid particular attention to the relative position, perspective, and power of the participants. In my own positionality as a native non-Colombian Spanish speaker, project workers and community leaders saw me as a neutral actor. However, as a white researcher from a privileged university in the global North, I had an ability to leave when situations were complex that not all of my participants possessed. Indeed, security concerns prevented me from visiting Leiva at the time, and I had to rely on interviews with project workers in the city of Pasto. Therefore I took every precaution to ensure that the data was collected with the consent and complete anonymity of all participants to ensure their contribution did not generate any problems during or after the fieldwork process.Footnote32

Nariño has been targeted by the state for infrastructure construction and seen a growing presence of multiple armed groups since the early 1990s, with the region largely ignored by both the central state and armed actors prior to that decade. Military efforts to dislodge the guerrillas and coca production were introduced in the north-east Cordillera region, including the municipality of Leiva by the late 1990s.Footnote33 The central municipality of Barbacoas faced this military crackdown later in the mid-2000s as cultivation shifted from the neighbouring department of Putumayo.Footnote34 I selected infrastructure projects in these two municipalities to unpack the community support strategy used by project workers despite military presence.

To demonstrate the broader scope of this strategy beyond Nariño, I also examine the construction of the River Amoyá hydroelectric dam in the department of Tolima as a shadow case. Dams are usually outside the scope of ‘Hearts and Minds’ cases or humanitarian work as they are often heavily opposed by local communities, particularly in Colombia.Footnote35 The similarities across these cases demonstrates that community agency is unlikely to depend solely on the type of infrastructure project as much as project workers’ strategy and the conditions of the local order.

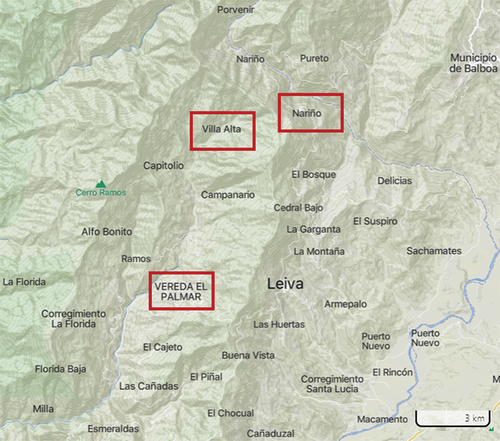

Path through the mountains: schools and roads in Leiva (1995–2015)Footnote36

In 1995, the departmental government of Nariño set out to build tertiary roads, schools, and other local infrastructure projects in the mountainous municipality of Leiva. Aside from treacherous conditions and poor existing roads, the engineers and project managers sent from Pasto also had to contend with the FARC’s 29th Front, established several years earlier. The FARC’s arrival to the communities had been marked by declarations of revolutionary intent and criticisms of the state for failing to invest in the region.Footnote37

Yet the arrival in 1995 of engineers and project managers undermined the FARC’s position. The state entered to build highly-desired roads in the mountainous municipality. In response the FARC appeared willing to allow the project, even co-opting elements of it by attending all the meetings with project engineers and workers, establishing when and where project workers could move, and even organising community labour to assist.Footnote38

This arrangement quickly fell apart as the military began a concerted incursion into the territory for the first time in the late 90s, and by 1999 were joined by the paramilitary forces of the Southern Liberation Block (Bloque Libertadores del Sur).Footnote39 The paramilitary group eventually demobilised in 2005, but many combatants regrouped under the neoparamilitary banner New Generation Self-Defence Organisation (OANG). Between 2006 and 2008 different groups wrestled over control of the drug trade, leading to multiple clashes, violence against civilians accused of acting as informants, and a dizzying arrays of alliances and enmities amongst the FARC, smaller factions of the ELN, and OANG.Footnote40 Fighting continued until 2008 and the infrastructure projects in Leiva were left to languish for almost eight years.Footnote41 As one of the head engineers noted, ‘it was an impressive violence and we could not work. We tried to coordinate with the local organisations to defend ourselves for the project. But it was six or seven years of that’.Footnote42

By 2008 the combination of violence and community protests in Leiva led to a reassessment of territorial strategy by the Colombian state.Footnote43 Communities, tired of the violence, coca crop fumigation, and lack of infrastructure investment, took to setting up blockades on the Panamericana road connecting the capital of Nariño with the rest of the country in 2008, grinding the economy of the department to a stop. After negotiations with local JACs and mayors, the government launched in 2009 a development initiative called Si Se Puede (Yes we can) to encourage rural development, including reinstating the local infrastructure projects.Footnote44 These new efforts sent project workers back to Leiva.

This time, instead of entering a relatively peaceful territory under FARC control, the project workers had to navigate a tense coexistence between FARC and state forces. Informal boundaries emerged where military forces stayed largely in the municipal centre of Leiva, while the FARC remained present in the corregimientos – sub-municipal administrative units organised around a JAC – of Nariño, Villa, and el Palmar. One official from the Department of Infrastructure of Nariño sent to check on the Si Se Puede project observed in 2012:

There was a [state] military checkpoint on the road. They said, if you go past here, we are no longer responsible for your security. I then had to explain [to the guerrillas] that I was there for the educational project so that they let us in.Footnote45

The military could not guarantee the project workers’ safety: instead, they had to rely on community support for the project.Footnote46 This approach also applied to other groups in the municipality. By 2008 the OANG was actively clashing with government forces.Footnote47 The engineer noted that by the time they went back, the OANG had begun to build a:

Similar relationship with community councils as these councils had with the guerrillas … some went with the guerrillas and some with the paramilitaries … [We went in] always with the support of the local leaders, like the presidents of JACs. We would also work with the mayor’s office. Sometimes we could not travel or move around certain times. We would communicate with local leaders and they would advise us. With other commanders it was more difficult. But there was no trouble working for these communities. The armed groups would not oppose these projects because they would also benefit, and it was a good relationship with the community.Footnote48

The JAC were considered integral to ‘guaranteeing the entry into the territory’ for the technical teams in carrying out the projects,Footnote49 which indicated even on official documents how project workers had to navigate the ongoing presence of the FARC or the OANG in the territory to gain ‘entry’.Footnote50

This strategy by project workers – and the community’s ability to mediate with the FARC and OANG – provided communities with the desired schools and roads.Footnote51 However, the armed groups also used the community to dictate how the project was built. The head engineer noted that whenever there ‘were some misunderstandings [with the FARC]’ about their intentions in the territory, they were informed by members of the community that they ‘had to leave’.Footnote52 Another project worker observed that they could work in the territory as long as they were ‘prudential’ and depended on the relationship between the guerrilla and the community.Footnote53 The fact that the JACs were considered heavily infiltrated by armed groupsFootnote54 was leveraged by project workers as a way to ensure their security, and by the FARC as an effective conduit for relaying their conditions of entry and to tell the engineers when they had to leave.Footnote55

Changes in the project could affect this mediated agreement. The head engineer, who continued to work on occasional projects in Leiva after Si Se Puede concluded, lamented that new project managers and government officials were jeopardizing the progress made:

‘New [project managers] bring external contractors where there are issues with corruption. There is more tension between the presidents of the JAC and the mayors, but it is saveable. We just have to have a reunion every month’.Footnote56

The engineer viewed the relationship to the JAC presidents as crucial to continued safe entry into the territory, even if less experienced colleagues did not. This reflects not only how the project workers’ security strategy can fortify civilian leadership with local authorities such as the mayor, but also the complicated and informal nature of such a strategy.

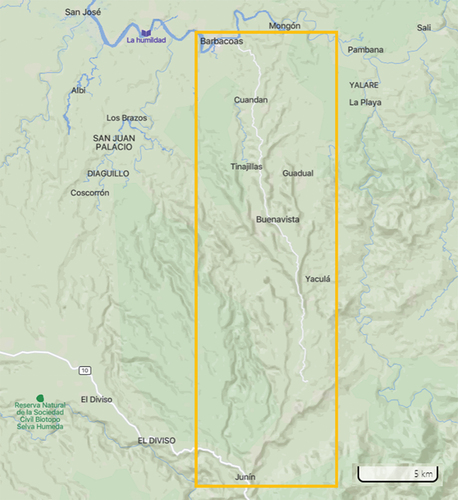

Connections in the jungle: the Barbacoas-Junín road (2012–2018)Footnote57

Project workers deployed a similar strategy of community support in the construction of a secondary road in Barbacoas. An unpaved path was the only main connection between the municipality to the rest of the department, whose population largely depended on a network of river systems for mobility. The path was also the focal point for the presence of multiple armed actors that sought to control its scant 55 kilometres. Neoparamilitary groups were concentrated at the initial entry point in the village of Junín, with the Rastrojos established since 2006 and then slowly pushed out by the Clan del Golfo in 2014.Footnote58 Military operations in the early 2000s in the area had been concentrated on the road and rarely penetrated the jungle. As a result, the ELN, with the Martyrs of Barbacoas were concentrated from the mid-point stop at Buenavista while the FARC’s Daniel Aldana Front – which controlled the territory north of Barbacoas – also maintained a strong presence on the northern part of the road and still patrolled further south.

Promises by the Nariño regional government to pave and improve the road to viable conditions failed to materialise, often succumbing to lack of political will and corruption.Footnote59 Efforts were also met by extortive demands by the Rastrojos, as well as the ELN and FARC, despite support for the project by the local communities.Footnote60 As one local afro-Colombian leader noted, ‘the FARC was charging vacuna [extortion] because they did not care about having the road well paved … so the “vacunas” were very present’.Footnote61

This dynamic changed when a group of local women mobilised in 2010, leading to national and international coverage.Footnote62 The national government eventually took action and by 2012 construction officially recommended with a battalion of military engineers and a protective military unit deployed in early 2013Footnote63 against the wishes of the community.Footnote64 As one indigenous Awa leader complained, ‘they did not warn us that a military battalion would arrive … there were no protocols of relation with the community … we were not okay with this permanent presence of the armed forces’.Footnote65

Despite some initial clashes it became evident that this military strategy was not sufficient to dislodge armed groups from the territory. On a visit to Barbacoas near the end of 2013, a UN official noted that the military and the FARC has established an uneasy truce, even appearing to agree to control different sections of the road, with the army telling him that they could not ensure his safety after a certain point, much like the army officials in Leiva. Instead, the UN official noted that ‘having a relationship with a social leader would help’.Footnote66 A later report by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights also indicated that the military presence on the Junín-Barbacoas road did not devolve into clashes with armed groups, but had rather resulted in a ‘tense calm’, where the army controlled the road to the south near Junín, while the FARC and ELN continued to have presence in the north.Footnote67

The regional government began to prioritise the community as their entry point into the territory. In 2014 the Nariño government created a Special Unit for the Junín-Barbacoas road. The Unit was intended to put the road management in civilian hands, who did not see the military as a source of security: ‘[the military battalion of engineers] has affected our project because there is always tension when the army arrives. It ends in shootings … ’.Footnote68 The social officer understood that his role was to win community support to secure the project from armed groups:

‘Here there has to be a social bridge. The engineers came and [the armed groups] thought they were here to do an investigation. They would threaten them. They know me and I have more access. You have to ask permission of the people. They would then ask for permission from the armed group that I could be there’.Footnote69

Other efforts by the Unit to win back community support including censuring one of the contracting companies and removed it from the project for mismanaging their construction and presenting falsified documentation on its completion after public outcry in Barbacoas.Footnote70 The Awa also benefited from locally hired labour – much like project managers in Leiva had tried to doFootnote71 – that in turn incentivised them to support the project with the armed groups:

The contractors came in and even used local labour … We then made it clear to everyone that we all would benefit from such a road. The armed groups understood our message in the territory. Yes, there were attacks against the military but that was just between the groups.Footnote72

Alongside hiring local indigenous labour, government officials also promised to provide smaller public goods and services that the Awa had requested. One official viewed this as a major reason for why the project did not face ‘any more significant inconveniences’,Footnote73 including FARC efforts to mine the road. The governor of the Awa cabildo intervened: ‘we all protested that that was not alright. We are very interested that the road project advance for our benefit. The patients were not reaching the hospitals in leaving for Junín. It was a very high priority. The FARC stopped mining’.Footnote74 The consejo comunitario of Nueva Esperanza also interceded with efforts by armed groups to extort the project workers. When the Clan del Golfo began extorting the Junín-Barbacoas contractors in 2014, a local leader explained:

‘in that moment it was up to me to sit down with the paramilitaries. You cannot tell us what to do, I told them; this project is ours and from our taxes. They said okay well that is alright … there is a strong pressure from the communities who say we want this [infrastructure] here. That makes them be aware and have a conscience and then they ask for less money because if not the project is just abandoned there. There is not opposition from the guerrillas, not even from paramilitaries, because the communities come out’.Footnote75

For project workers, strengthening a positive relationship with the community meant its officials and project managers could rely on the community to secure their presence by interceding on their behalf with armed groups. If the community were to provide project workers with military intelligence it would jeopardise civilians own security – which the state was unable to guarantee even with the military – and the security of the project. As the official for the Junín-Barbacoas project explained, the project construction was always aware that it was sharing space with armed groups despite the presence of the Colombian military:

There were unofficial rules. The workers are from there and they tell us when to go in. We can only go in until 10pm. The local leaders themselves tell us these rules. They will accompany us and only for half an hour, and then for example we could not work anymore. The technicians were also from the area and they would anticipate the risks. Today yes, tomorrow no, only go up until that point, don’t get too far from us.Footnote76

A local inhabitant of Barbacoas even explained that the FARC agreed not to interfere with the road project but required that the workers refrain from using a camera; ‘a very simple rule’ to keep the peace.Footnote77 It ensured that the community could have a road, the project workers could secure their presence and continue working on the project, and the FARC reduced the chances of intelligence being put in the hands of Colombian military. Armed groups, like the FARC in Leiva, used the community as an intermediary to impose guidelines on project workers that prevented the state from gaining a military advantage.

In the heartland of the FARC: Amoyá hydroelectic (2008–2013)Footnote78

In 1999 the utilities company Generadora Union was awarded the rights to build a hydroelectric dam on the River Amoyá in the municipality of Chaparral located in the south-central department of Tolima. The proposed construction was particularly ambitious given the presence of the 21st Front of the FARC. The mountainous region was the oldest stronghold of the group, where in 1964 a small group of rebels fought the Colombian army in the battle of Marquetalia, the mythologised origin story for the leftist guerrillas.Footnote79

The Colombian government’s initial foray into the territory was to send aid money to local families (Plan Familias Guardabosques – PFGB) in 2003, purportedly for coca substitution but also to assess viability for a hydroelectric project.Footnote80 Unlike the 29th Front in Leiva, the FARC in Chaparral prohibited local villagers from accepting governmental aid, seeing it as a threat to their territorial control.Footnote81 Faced with the looming risk of FARC backlash, Generadora Union tried to deploy non-military strategies to safely enter the territory in 2005. Like the project managers and officials in Leiva and Barbacoas, Generadora Union considered the relationship between the FARC’s 21st Front and the local community in Amoyá an asset to securing the project. An environmental impact report in 2003 by Generadora Union and its partner ISAGEN (another utilities company) observed that the close relations between the FARC and the local community presented an opportunity to mitigate risk:

‘The presence of the armed group generated a certain level of “security and protection” in the region, as there were no longer any fights, thefts, or family abuse. Although this situation could be considered a threat to the Project, we could also think that the coordination and co-management that are consistent with the principles of [local] participation and agreement between all the different actors involved in the processes in the region, could generate the adequate conditions to ensure that the project is carried out in the best possible terms. It is important to note and highlight the need to carry out a work of concertation and sensitization of the Project that involves the various social actors of the region, the ignorance of any of the parties may be misunderstood and generate an inappropriate environment for the development of the Project [emphasis own]’.Footnote82

However, this strategy was complicated since the dam project itself was not desired by local civilians. The officials and project managers of Generadora approached the local JACs to offer them additional concessions in road constructions and small schools that would help develop the local villages in exchange for serving as part of the security protocol in the project’s construction and avoiding the army. The project workers viewed the community as a necessary conduit to reaching the FARC’s approval for the dam, since ‘by obligation, [the community] had to go consult the guerrillas’.Footnote83

Yet initial efforts to establish a good working relationship with the JAC struggled to gain traction due to opposition by the FARC, who had begun to ‘jump at shadows’ since the implementation of the PFGB, accusing civilians of passing information to the military if they cooperated with the project.Footnote84 Generadora Union’s community support strategy was finally completely disrupted by a change in management when ISAGEN took full control in 2006. Unlike Generadora Union, ISAGEN insisted on accompaniment by the military,Footnote85 despite project workers within the same company preferring to avoid it.Footnote86

This lead to active combat between the FARC and the state between 2006 and 2008, with direct clashes rising from 85 events per year in 2005 to nearly 180 in 2007,Footnote87 as well as increasing attacks by FARC and military against civilians.Footnote88 The FARC were aggressive against the project in this period, considering it a ‘trap for the Army to consolidate territorial control’, and continuing to victimise civilians as potential informants (sapos) if they appeared to support the project.Footnote89

Between 2008 and 2010 the intensity of the battles began to wane and both actors established informal boundaries, with the FARC in mountains of Las Hermosas while the military established a base near the village of Chaparral in the valley.Footnote90 The engineers and builders still needed assurances for their safety as their work took them sometimes up into the mountains. ISAGEN’s social team had been trying to work around the difficulties generated by the military presence in the area by convincing civilians that the presence of project workers was not designed to communicate intelligence to the army, even actively avoiding military accompaniment where possible.Footnote91

However, local communities were now hostile to the project, worried about flooding and angry about the increased military presence and fighting in the territory, leading protests to emerge under the banner ASOHERMOSAS between 2007 and 2009.Footnote92 By 2010 ISAGEN refocused efforts to win back the community, when the director of ISAGEN agreed to use a Transparency Table – established in 2007 but virtually abandoned since – as a platform to improve communication between the company, the military, and the local community.Footnote93 The Table brought civilian leaders from JACs and ASOHERMOSAS to voice their grievances. ISAGEN also brought military officials to the Table to make promises and assurances to civilian leaders that they would investigate cases of victimisation and respect local communities in the territory.Footnote94

With a tense co-existence established in the local order, and ISAGEN attempting to win over the community through the Transparency Table, the FARC became more wary of losing community support; ‘the guerrillas did not want to antagonise the community, so they cautiously accepted the implementation of the project’.Footnote95 One local leader even explained that the shift in FARC attitude towards the dam was a reflection of the relationship between the FARC and the community: ‘if [the community] wanted the company to come in, the guerrillas would accommodate that. But if they wanted to oppose [the dam], the comrades would be there as well’.Footnote96 Much like the leaders in Barbacoas, civilians explicitly referenced their own agency in affecting the behaviour of the armed group. This appeared to be true to an extent. With community support, project workers were able to enter the more remote parts of the mountain as long as – as one ex-FARC combatant explained – the military stayed ‘in the valley’.Footnote97 This was considered a success by ISAGEN leadership, who viewed improved relation with civilians through the Transparency Table as key to the ‘continuation of the construction at the most critical moments of the project’.Footnote98

Infrastructure and the limitations of local agency

Political actors often frame infrastructure construction in conflict areas as proof of the state’s successful delivery of goods in the face of armed opposition,Footnote99 despite the messy realities that project workers navigate on the ground. President Santos declared in 2013 that the River Amoyá dam in Chaparral had been ‘built through fire and blood’ and ‘against the will of the FARC’.Footnote100 In Barbacoas, Major Sánchez Peralta of the Colombian army assured that engineers and project workers ‘depended on our trained troops and special forces, including anti-explosive unites to counter criminal actions and keep not just our engineers safe during their work but also our civilian population, the primary motive for our work’.Footnote101 In Leiva, the language was less charged but still positioned as a political win; the project heralded, according to the Governor of Nariño, a new step towards peace and cultures of legality.Footnote102 State actors positioned the constructions as military victories and statebuilding successes,Footnote103 despite the fact that the projects had ultimately been constructed with the tacit – if begrudging – approval of armed groups.

Inverting this counterinsurgent framing, project workers saw community support as crucial to the successful construction of infrastructure, rather than the other way around. In all three cases, some degree of uneasy coexistence with armed groups – pressurized by the close presence of state military forces – generated the space for civilians to take a greater role in negotiating the safety of the infrastructure construction. Therefore project workers went beyond the project itself, relying on local labour, smaller infrastructure projects, and increased transparency to win over the community. Their objective was not to separate the civilians from the armed group, but rather rely on their closeness.

This strategy reflects the fact that relationships between armed groups and local civilians can cut both ways, allowing civilians to influence armed groups as well. Arjona argues that strong local institutions are able to negotiate with armed imposition,Footnote104 and Rubin observes that groups may even seek civilian institutions because it can better support rebel groups with information gathering and resource mobilization, even if this agency improves the bargaining ability of civilians.Footnote105 The creation of these local civilian institutions also improve collective action capacity to pressure the state in providing desired goods or services,Footnote106 especially in generating media attention and agenda setting,Footnote107 as shown in all three cases.

However, civilian agency is still limited. ISAGEN designated the Transparency Table in Amoyá as a relationship-building platform to enable the safe construction of the project. ISAGEN continued to host discussions at the Table between 2014 and 2017, promising improvement of roadworks, the building of schools, better energy provision, and assurances of measures taken to mitigate the environmental damage caused by the dam. Yet by 2018 none of them had been implemented. With the dam finished and the FARC officially demobilised from the area, the interest by ISAGEN in continuing to use the Table had faded, leaving civilian leaders frustrated.Footnote108

These cases also challenge the supposition that armed groups always act on behalf of the wishes of the community. Multiple actors across the three cases, from project workers to civilians themselves, echoed the expectations in humanitarian circles that armed groups acquiesce to the wishes to the people. One analyst in Bogota even argued that the FARC always allowed projects popular with communities.Footnote109 This may be the case in some circumstances, as the FARC demonstrated in Leiva before the arrival of the military. Yet local support is not always foremost in the minds of armed groups, especially in the face of military pressure.Footnote110 Where all-out confrontation emerged, the projects were often abandoned or became military targets. Yet where there was no military presence at all, armed groups could reject any governmental projects entirely – as in Chaparral – or seek to extort it beyond viability – as in Barbacoas, despite the community’s wishes.

These local dynamics constrain the strategies of project workers and civilian agency. As Worral posits, armed groups not only respond to external orders (which dictate military incursions) but also how this affects their relationship with other societal agents and structures within their locality,Footnote111 such as the relationship they have with JACs, consejos comunitarios, and cabildos. Similar to Staniland’s tacit coexistence, Idler argues that pacific coexistence between armed groups and the military generates a greater incentive for opposing actors to ‘strive for the social recognition of the local population in order not to be out-ruled by the other’.Footnote112 Therefore armed groups may have similar incentives to project workers in winning community support when they coexist with military forces: their willingness to listen to civil leaders is therefore less a reflection of an ideological position and more a response to the immediate security concerns in the local order.

The agency and limitations of civilians mediating between project workers and armed groups deserves further exploration. This paper has demonstrated that the logic and decision of project workers to seek community support functions as a temporary security strategy rather than a long-term statebuilding project that reflects the fluctuating and complex nature of local orders.Footnote113 Future research could build on this to better understand why and how civilians and armed groups play their part in this dynamic. Assumptions about a positive relationship between civilians and armed groups overlooks key variations in when and why armed groups are more susceptible to community pressure. The type of government leading the project may influence armed group response, just as the group’s own internal order may shape its interactions with local social actors and external players.Footnote114 Indeed, this is a concern in the humanitarian sector as well, since there are cases where aid workers have endangered themselves by assuming there were linkages between communities and armed groups where there were not.Footnote115

These cases represent only a small sample of a wider universe where governments build infrastructure in areas controlled by armed groups. However, here I have unpacked the confrontations, miscommunications, and negotiations that can underpin public goods delivery in conflict areas. I show how actors – even within government – may disagree on strategy during infrastructure construction. I explore how the fragility of a ‘tacit coexistence’ keeps the ground shifting underfoot and project workers must constantly renew their appeal to local communities to gain safe passage. Finally I demonstrate both the opportunity these projects provide for local agency to assert itself and the limitations generated by local orders and finite construction. Identifying community support as a pragmatic response to complex local orders rather than a blunt measure of counterinsurgency success allows researchers and policy-makers to better assess public goods delivery in contexts where armed groups, project workers, military forces, and civilian institutions must unhappily co-exist.

Interviews

1. Development bank engineer (2), Bogota – September 2018.

2. Development bank official (3), Bogota – September 2018.

3. Thinktank analyst (7), Bogota – September 2018.

4. Development bank senior official (44), Bogota – February 2019.

5. Former Transport Minister (45), Bogota – February 2019.

6. Project manager for Junín-Barbacoas road (50), Pasto – February 2019.

7. Project support staffer (52), Pasto – February 2019.

8. Government infrastructure official (54), Pasto – February 2019.

9. Project engineer (56), Pasto – February 2019.

10. UN official (61), Pasto – February 2019.

11. Development agency director (62), Pasto – March 2019.

12. UN official (63), Pasto – March 2019.

13. Regional leader (67), Tumaco – March 2019.

14. Project social officer (72), Barbacoas – March 2019.

15. Local inhabitant (73), Barbacoas – March 2019

16. Local councilor (74), Barbacoas – March 2019.

17. Local leader (75), Barbacoas – March 2019.

18. Piernas Cruzadas activist (76), Barbacoas – March 2019.

19. Indigenous leader (77), Pasto – March 2019.

Acknowledgments

This work has was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council for the completion of DPhil in International Relations at the University of Oxford. All data collection was done in line with Ethics requirements of the University and approval of the CUREC Review Board. I would like to thank the research participants for their openness and generosity with their time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Clara Voyvodic

Dr Clara Voyvodic is currently a Senior Research Fellow on the ESRC project “Getting on with it: Understanding the microdynamics of post-accord intergroup social relations”. Clara is also co-Chair of the Peace, Conflict, and Violence Working Group (GIC) at the University of Bristol, and Fellow at the Centre for Armed Groups, Geneva. She received her PhD from the University of Oxford in International Relations, and has a background in studying transnational organized crime, conflict, and development at the Universities of Glasgow and St Andrews, as well as working as a practitioner. Clara’s research focuses on the intersections of rebel governance, community organizing, statebuilding, and illicit economies, particularly around conflict transitions, with extensive fieldwork experience in Colombia and Northern Ireland.

Notes

1. Interview with former Transport Minister (45), Bogota – February 2019.

2. Zeiderman, ‘Concrete Peace’, 8; Yepes et al., ‘Infraestructura de Transporte En Colombia’.

3. Crost, Felter, and Johnston, ‘Aid under Fire’; Khanna and Zimmermann, ‘Guns and Butter?’; Weintraub, ‘All Good Things’; Sexton, ‘Aid as a Tool against Insurgency’.

4. Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, ‘Virtuous or Vicious Circle?’; Brinkerhoff, Wetterberg, and Dunn, ‘Service Delivery and Legitimacy in Fragile States’; Mcloughlin, ‘When the Virtuous Circle Unravels’.

5. Porch, Counterinsurgency.

6. These institutions were developed as semi-autonomous community organisations, although the special protected status of cabildos and consejos comunitarios in the 1991 Constitution generated more intensive land rights than granted to JACs (Pinzón, ‘Las Minorías Étnicas Colombianas En La Constitución Política de 1991’; IDPAC, ‘Preguntas Frecuentes Sobre La Organizacion Comunal’).

7. Staniland, ‘States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders’, 252.

8. Kilcullen, The Accidental Guerrilla, 71; Berman, Shapiro, and Felter, ‘Can Hearts and Minds Be Bought?’, 810; Sexton, ‘Aid as a Tool against Insurgency’.

9. Gutiérrez, ‘The Counter-Insurgent Paradox’.

10. Rempe, The Past as Prologue?, 19.

11. Gutiérrez, ‘The Counter-Insurgent Paradox’, 107; Ballvé, ‘Everyday State Formation’, 612.

12. Ballvé, ‘Everyday State Formation’, 4.

13. Rempe, The Past as Prologue?, 22.

14. Kalyvas, ‘Micro-Level Studies of Violence in Civil War’, 660.

15. Gutiérrez, ‘The Counter-Insurgent Paradox’; Larratt-Smith, ‘Navigating Formal and Informal Processes’.

16. Palmer, ‘FONCODES y Su Impacto En La Pacificación En El Perú’.

17. Palmer, 171–73.

18. Sexton and Zürcher, ‘Aid, Attitudes, and Insurgency’. Multiple large-N studies have used defection of civilians due to service delivery to try and understand fluctuations in violence, with mixed results; Zürcher, ‘What Do We (Not) Know about Development, Aid, and Violence?’; Sexton, ‘Aid as a Tool against Insurgency’; Beath, Christia, and Enikolopov, Winning Hearts and Minds through Development; Khanna and Zimmermann, ‘Guns and Butter?’

19. Fast et al., ‘In Acceptance We Trust?’, 11.

20. Breslawski, ‘The Shortcomings of International Humanitarian Law’.

21. Jackson and Giustozzi, ‘Talking to the Other Side: Humanitarian Engagement with the Taliban in Afghanistan’; Haddad and Svoboda, ‘What’s the Magic Word? Humanitarian Access and Local Organisations in Syria’; Smith and Minear, Humanitarian Diplomacy: Practitioners and Their Craft.

22. Breslawski, ‘The Shortcomings of International Humanitarian Law’, 3.

23. It should be noted that aid workers do not always appear apolitical and that can also increase their risk of attack by armed groups (Hoelscher, Miklian, and Nygård, ‘Conflict, Peacekeeping, and Humanitarian Security’).

24. Interview with development bank senior official (44), Bogota – February 2019.

25. Interview with engineer (65), Tumaco – March 2019. This sentiment was also expressed by a public official (64), Tumaco – March 2019, development bank project manager (3) and engineer (2), Bogota – September 2018, and the senior official (44), Bogota – February 2019.

26. Ministry of National Defence, ‘Democratic Security and Defence Policy’, 37.

27. Staniland, ‘States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders’, 251–52.

28. See .

29. Yepes et al., ‘Infraestructura de Transporte En Colombia’.

30. Tellez, ‘Peace Agreement Design and Public Support for Peace: Evidence from Colombia’, 832; Herbolzheimer, Innovations in the Colombian Peace Process, 3.

31. Wood, ‘The Ethical Challenges of Field Research in Conflict Zones’, 373.

32. Ethics approval was granted by the University of Oxford: CUREC number SSH_DPIR_C1A_18_037.

33. Muñoz, ‘Municipio de Leiva (Nariño)’, 205.

34. Idler, Borderland Battles, 91.

35. Chato, ‘Hidroituango o La Criminalización de La Resistencia’; Leguizamón Castillo, ‘Conflictos Ambientales y Movimientos Sociales’; Lakhani, Who Killed Berta Caceres?: Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet; Kiik, ‘Confluences amid Conflict’; Delina, ‘Indigenous Environmental Defenders and the Legacy of Macli-Ing Dulag’.

36. See .

37. Muñoz, ‘Municipio de Leiva (Nariño)’, 206.

38. Interview with project manager (56), Pasto – February 2019.

39. Muñoz, ‘Municipio de Leiva (Nariño)’, 207.

40. MAPP/OAS, ‘Octavo Informe Trimestral Del Secretario General al Consejo Permanente’, 9; HRW, ‘Paramilitaries’ Heirs: The New Face of Violence in Colombia’; Muñoz, ‘Municipio de Leiva (Nariño)’, 220.

41. Verdad Abierta, ‘La “Cacería” Del Frente Libertadores Del Sur’.

42. Interview with director of NGO and civil engineer (56), Pasto – February 2019.

43. Jiménez Villabona, ‘Leiva, Nariño y Su Relación Con La Coca Desde 1990 al 2014’, 63.

44. Jiménez Villabona, 2.

45. Interview with government official (54), Pasto – February 2019.

46. A UN team describes a similar dynamic in 2013 in relying on community support to enter Leiva past the military checkpoint (interview with UN officials [63], Pasto – March 2019).

47. HRW, ‘Paramilitaries’ Heirs: The New Face of Violence in Colombia’.

48. Interview with project manager (56), Pasto – February 2019.

49. Ceballos Varela, ‘Efectos de Formalización de Tierra, Leiva’, 99; Ministerio de Justicia, ‘Drogas Ilícitas, Departamento de Nariño’, 63.

50. Gonzales Skaric and Landa Peredo, ‘Cultura de La Legalidad’, 20.

51. For civilian attitudes towards the road projects see a survey conducted in Gonzales Skaric and Landa Peredo, 28.

52. Ibid.

53. Interview with project support staff (52), Pasto – February 2019.

54. Ceballos Varela, ‘Efectos de Formalización de Tierra, Leiva’, 100.

55. Interview with engineer (56), Pasto – February 2019.

56. Interview with engineer (56), Pasto – February 2019.

57. See .

58. Semana, ‘Bacrim Se Expanden En El Sur Del País’.

59. Interview with local councilor (74), Barbacoas – March 2019; interview with development agency director (62), Pasto – March 2019; interview with local leader (75), Barbacoas – March 2019.

60. Interview with social worker (72), Barbacoas – March 2019; interview with public official (50), Pasto – February 2019; interview with local leader (75), Barbacoas – March 2019; interview with regional leader (67), Tumaco – March 2019; interview with development agency director (62), Pasto – March 2019.

61. Interview with leader of regional collective (67), Tumaco – March 2019.

62. Under the name Piernas Cruzadas (literally, Crossed Legs) the group, in a modern echo of Lysistrata, went on a sex strike to protest the failure of the state to build the road. By June 2011 the strike gained national and even international attention, successfully incentivising national leadership to put pressure on the regional government to renew its efforts in building the Junín-Barbacoas road and led to the deployment of military engineers to tackle part of the construction (Interview with Piernas Cruzadas activist (76), Barbacoas – March 2019).

63. HSB Noticias, ‘Creen Que La Vía Junín – Barbacoas Está Maldita’; El Nuevo Siglo, ‘Perspectiva. Arreglaron “Vía de La Muerte” Con Ingenieros Militares’.

64. Interview with local leader (75), local councillor (74), local inhabitant (73), and project social officer (72), Barbacoas – March 2019.

65. Interview with Awa indigenous leader (77), Pasto – March 2019.

66. Interview with UN official (61), Pasto – February 2019.

67. UNHCHR, ‘Barbacoas: Un Olvido, Muchos Conflictos’.

68. Interview with project manager for Junín-Barbacoas road (50), Pasto – February 2019.

69. Interview with social officer (72), Barbacoas – March 2019.

70. Diario del Sur, ‘Vía Junín-Barbacoas Lista Este Año’.

71. Two national-level engineers also explained that they viewed local hiring practices as part as a ‘strategy for working in conflictive areas’, linking improved relationship with the community to a safer relationship with armed groups (interviews with development bank project manager (3) and engineer (2), Bogota – September 2018).

72. Interview with indigenous leader (77), Pasto – March 2019.

73. Interview with project manager for Junín-Barbacoas road (50), Pasto – February 2019.

74. Interview with indigenous Awa leader (77), Pasto – March 2019.

75. Interview with local leader (75), Barbacoas – March 2019.

76. Interview with project manager for Junín-Barbacoas road (50), Pasto – February 2019.

77. Interview with a local inhabitant (73), Barbacoas – March 2019.

78. See .

79. Villamizar Herrera, Las Guerrillas En Colombia, 89.

80. Vargas Hernández, ‘El Estado Diferenciado’, 62.

81. Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá’, 15.

82. Garcia Lozano, Generadora Union, and Isagen, ‘Estudio Ambiental Hidroelectrico Rio Amoya’, 3–4.

83. Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá’, 17.

84. Patiño and Miller, 16.

85. Vargas Hernández, ‘El Estado Diferenciado’, 95; Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá’, 18.

86. Patino y Miller 25.

87. FIP, ‘Dinámicas Del Conflicto Armado En Tolima y Su Impacto Humanitario’, 22.

88. ILSA, ‘Tolima | Las Hermosas: Hidroeléctrica Del Río Amoyá y Luchas Por El Territorio’, 78.

89. Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá’, 21.

90. Aguja Zamora, ‘Organización de Comunidades Campesinas de Las Hermosas’, 21; Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá’, 25.

91. Patino y Miller 25.

92. Aguja Zamora, ‘Organización de Comunidades Campesinas de Las Hermosas’, 20–21.

93. Ñungo, ‘Se Realizó Mesa de La Transparencia En El Cañón de Las Hermosas En Chaparral’; Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá’.

94. Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá’, 26; Aguja Zamora, ‘Organización de Comunidades Campesinas de Las Hermosas’, 62.

95. Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá’, 26.

96. Aguja Zamora, ‘Organización de Comunidades Campesinas de Las Hermosas’, 75; Another local leader observed that the dam was built with permission of the FARC through negotiations with communities at the Transparency Table (Vargas Hernández, ‘El Estado Diferenciado’, 44).

97. Interview with former FARC guerrilla in Patiño and Miller, ‘ISAGEN y La Construcción de La Central Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá-La Esperanza’, 26.

98. Patiño and Miller, 2.

99. Zeiderman, ‘Concrete Peace’; Bachmann and Schouten, ‘Concrete Approaches to Peace: Infrastructure as Peacebuilding’.

100. El Nuevo Dia, ‘Central Hidroeléctrica Del Río Amoyá’.

101. El Nuevo Siglo, ‘Perspectiva. Arreglaron “Vía de La Muerte” Con Ingenieros Militares’.

102. Gobernación de Nariño, ‘Positivo Balance Del Programa de Desarrollo Rural Alternativo, “Sí Se Puede”’.

103. This counterinsurgent narrative can be found in other conflict areas: Sen observes in India that high-ranking officials claimed that new roads had undermined the Maoist guerrillas, even putting up banners to that effect, while former Maoist guerrillas argued the roads had little impact (Bullets to Ballots, 121.)

104. Arjona, Rebelocracy; Arjona, ‘Institutions, Civilian Resistance, and Wartime Social Order’.

105. Rubin, ‘Rebel Territorial Control and Civilian Collective Action’.

106. Price, ‘Keystone Organizations Versus Clientelism’; Auerbach, Demanding Development; Boulding, NGOs, Political Protest, and Civil Society.

107. Amenta et al., ‘The Political Consequences of Social Movements’; Burstein, American Public Opinion, Advocacy, and Policy in Congress.

108. Briceño Alvarado et al., ‘La Transformación de Las Comunidades Desde Los Procesos Educativos’, 59.

109. Interview with analyst (7), Bogota – September 2018.

110. For a recent overview on the dynamics of civil-military relationships in armed conflict see Balcells and Stanton, ‘Violence against Civilians during Armed Conflict’; Malthaner, ‘Violence, Legitimacy, and Control’; Wood, ‘Opportunities to Kill or Incentives for Restraint?’; Kalyvas, Logic of Violence.

111. Worrall, ‘(Re-)Emergent Orders’.

112. Idler, Borderland Battles, 312.

113. Staniland, ‘States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders’, 249.

114. Worrall, ‘(Re-)Emergent Orders’, 725.

115. Carter and Haver, ‘Humanitarian Access Negotiations with Non-State Armed Groups’, 63.

Bibliography

- Aguja Zamora, Rafael Antonio. “Organización y Re-Existencia de Las Comunidades Campesinas de Las Hermosas: Estudio de Caso Sobre Las Dinámicas de Protesta y Organización Campesina Frente al Proyecto Hidroeléctrico En La Cuenca Del Río Amoyá.” (2021).

- Amenta, Edwin, Neal Caren, Elizabeth Chiarello, and Su. Yang. “The Political Consequences of Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 36, no. 1 (2010): 287–307. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120029.

- Arjona, Ana. Rebelocracy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Arjona, Ana. “Institutions, Civilian Resistance, and Wartime Social Order: A Process-Driven Natural Experiment in the Colombian Civil War.” Latin American Politics and Society 58, no. 3 (2016): 99–122. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2016.00320.x.

- Auerbach, Adam Michael. Demanding Development: The Politics of Public Goods Provision in India’s Urban Slums. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Bachmann, Jan, and Peer Schouten. “Concrete Approaches to Peace: Infrastructure as Peacebuilding.” International Affairs 94, no. 2 (2018): 381–398. doi:10.1093/ia/iix237.

- Balcells, Laia, and Jessica Stanton. “Violence Against Civilians During Armed Conflict: Moving Beyond the Macro-And Micro-Level Divide.” Annual Review of Political Science 24, no. 1 (2021): 45–69. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102229.

- Ballvé, Teo. “Everyday State Formation: Territory, Decentralization, and the Narco Landgrab in Colombia.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30, no. 4 (2012): 603–622. doi:10.1068/d4611.

- Beath, Andrew, Fotini Christia, and Ruben Enikolopov. “Winning Hearts and Minds Through Development? Evidence from a Field Experiment in Afghanistan.” The World Bank (2012): 1–31.

- Berman, Eli, Jacob N. Shapiro, and Joseph H. Felter. “Can Hearts and Minds Be Bought? The Economics of Counterinsurgency in Iraq.” Journal of Political Economy 119, no. 4 (2011): 766–819.

- Boulding, Carew. NGOs, Political Protest, and Civil Society. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Breslawski, Jori. “The Shortcomings of International Humanitarian Law in Access Negotiations: New Strategies and Ways Forward.” International Studies Review 24, no. 1 (2022): viac007.

- Briceño Alvarado, Patricia, Néstor Daniel Sánchez Londoño, Yolanda Lemus Sánchez, Ginna Constanza Méndez Cucaita, Alba Inés Osorio Cuenca, Diego Alberto Ortegón González, Karim Sanabria Poveda, Mariana Andrea Cardozo, Harvey Oliver Criollo, and Martha Lucía García Tapia. La Transformación de Las Comunidades Desde Los Procesos Educativos. Bogota: Sistematización de Experiencias de Proyección Social de UNIMINUTO En Los Territorios.’, 2020.

- Brinkerhoff, Derick W, Anna Wetterberg, and Stephen Dunn. “Service Delivery and Legitimacy in Fragile and Conflict-Affected States: Evidence from Water Services in Iraq.” Public Management Review 14, no. 2 (2012): 273–293. doi:10.1080/14719037.2012.657958.

- Burstein, Paul. American Public Opinion, Advocacy, and Policy in Congress: What the Public Wants and What It Gets. Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Carter, William, and Katherine Haver. ‘Humanitarian Access Negotiations with Non-State Armed Groups: Internal Guidance Gaps and Emerging Good Practice’. Secure Access in Volatile Environments (SAVE) Research Programme. London: Humanitarian Outcomes, 2016.

- Ceballos Varela, Catalina. “Efectos de La Formalización de La Propiedad de La Tierra En El Desarrollo Rural: El Caso de Leiva, Nariño.” Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (2016).

- Chato, Pilar. “Hidroituango o La Criminalización de La Resistencia.” Colombia Plural (2016). https://colombiaplural.com/hidroituango-la-criminalizacionde-la-resistencia/.

- Crost, Benjamin, Joseph Felter, and Patrick Johnston. “Aid Under Fire: Development Projects and Civil Conflict.” American Economic Review 104, no. 6 (2014): 1833–1856. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1833.

- Delina, Laurence L. “Indigenous Environmental Defenders and the Legacy of Macli-Ing Dulag: Anti-Dam Dissent, Assassinations, and Protests in the Making of Philippine Energyscape.” Energy Research & Social Science 65 (2020): 101463. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101463.

- Diario del Sur. “Vía Junín-Barbacoas Lista Este Año.” Diario Del Sur (2019). https://diariodelsur.com.co/noticias/local/junin-barbacoas-lista-este-ano-518627

- El Nuevo Dia. “Central Hidroeléctrica Del Río Amoyá: Una Obra Que a Sangre y Fuego Salió Avante.” El Nuevo Dia (2013). http://www.elnuevodia.com.co/nuevodia/actualidad/politica/186821-central-hidroelectrica-del-rio-amoya-una-obra-que-a-sangre-y-fuego-salio-

- El Nuevo Siglo. “Perspectiva. Arreglaron “Vía de La Muerte” Con Ingenieros Militares.” Redaccion Politica El Nuevo Siglo (2023). https://www.elnuevosiglo.com.co/articulos/11-12-2022-perspectiva-arreglaron-carretera-de-la-muerte-con-ingenieros-militares

- Fast, Larissa A, C. Faith Freeman, Michael O’Neill, and Elizabeth Rowley. “In Acceptance We Trust? Conceptualising Acceptance as a Viable Approach to NGO Security Management.” Disasters 37, no. 2 (2013): 222–243. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2012.01304.x.

- FIP. “Dinámicas Del Conflicto Armado En Tolima y Su Impacto Humanitario.” Fundación Ideas Para La Paz 62 (2013): 1–28.

- Garcia, Lozano, Luis Carlos, Generadora Union, and Isagen. “Proyecto Hidroelectrico Rio Amoya : Estudio de Impacto Ambiental.” The World Bank (2003). https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/992071468744095085/pdf/E8420VOL102010PAPER.pdf.

- Gobernación de Nariño. ‘Positivo Balance Del Programa de Desarrollo Rural Alternativo, “Sí Se Puede” Del Primer Trimestre de 2013’, 2013. http://2012-2015.narino.gov.co/index.php/component/content/article/55-gobernacion-de-narino/despacho-del-gobernador/oficina-de-prensa/noticias/3105-positivo-balance-del-programa-de-desarrollo-rural-alternativo-si-se-puede-del-primer-trimestre-de-2013?highlight=WyJzaSIsInNlIiwicHVlZGUiLCJsZWl2YSIsInNpIHNlIiwic2kgc2UgcHVlZGUiLCJzZSBwdWVkZSIsInNlIHB1ZWRlIGxlaXZhIiwicHVlZGUgbGVpdmEiXQ==.

- Gonzales Skaric, Javier, and Ignacio Landa Peredo. “Cultura de La Legalidad: El Caso de Los Municipios de Leiva y Rosario.” Observatorio de Cultivos Declarados Ilícitos (2014): 1–43.

- Gutiérrez, José Antonio. “The Counter-Insurgent Paradox. How the FARC-EP Successfully Subverted Counter-Insurgent Institutions in Colombia.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 32, no. 1: 103–126. (2 January 2021). doi:10.1080/09592318.2020.1797345.

- Haddad, Saleem, and Eva Svoboda. ‘What’s the Magic Word? Humanitarian Access and Local Organisations in Syria’. HPG Working Paper. London: ODI, 2017.

- Herbolzheimer, Kristian. “Innovations in the Colombian Peace Process.” NOREF, Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Centre (2016): 1–10.

- Hoelscher, Kristian, Jason Miklian, and Håvard Mokleiv Nygård. “Conflict, Peacekeeping, and Humanitarian Security: Understanding Violent Attacks Against Aid Workers.” International Peacekeeping 24, no. 4 (2017): 538–565. doi:10.1080/13533312.2017.1321958.

- HRW. “Paramilitaries’ Heirs: The New Face of Violence in Colombia.” Human Rights Watch (2010). https://www.hrw.org/report/2010/02/03/paramilitaries-heirs/new-face-violence-colombia#.

- HSB Noticias. “Creen Que La Vía Junín - Barbacoas Está Maldita.” HSB Noticias 12 February 2015. https://hsbnoticias.com/noticias/nacional/creen-que-la-v%C3%ADa-jun%C3%ADn-barbacoas-est%C3%A1-maldita-125591.

- Idler, Annette. Borderland Battles: Violence, Crime, and Governance at the Edges of Colombia’s War. Oxford University Press, 2019.

- IDPAC. “Preguntas Frecuentes Sobre La Organizacion Comunal.” Alcaldia de Bogota (2023). https://www.participacionbogota.gov.co/sites/default/files/2020-04/PREGUNTAS%20FRECUENTES%20ORGANIZACIONES%20COMUNALES.pdf.

- ILSA. ‘Tolima | Las Hermosas: Hidroeléctrica Del Río Amoyá y Luchas Por El Territorio’. Instituto Latinoamericano para una Sociedad y un Derecho Alternativos, 2014. https://issuu.com/ilsaenred/docs/tolima.

- Jackson, Ashley, and Antonio Giustozzi. “Talking to the Other Side: Humanitarian Engagement with the Taliban in Afghanistan.” Humanitarian Policy Group (2012): 1–29.

- Jiménez Villabona, Camilo Fernando. “Leiva, Nariño y Su Relación Con La Coca Desde 1990 al 2014.” Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (2014).

- Kalyvas, Stathis N. “The Logic of Violence in Civil War.” In Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Kalyvas, Stathis N. “Micro-Level Studies of Violence in Civil War: Refining and Extending the Control-Collaboration Model.” Terrorism and Political Violence 24, no. 4 (2012): 658–668. doi:10.1080/09546553.2012.701986.

- Khanna, Gaurav, and Laura Zimmermann. “Guns and Butter? Fighting Violence with the Promise of Development.” Journal of Development Economics 124 (2017): 120–141. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.09.006.

- Kiik, Laur. “Confluences Amid Conflict: How Resisting China’s Myitsone Dam Project Linked Kachin and Bamar Nationalisms in War-Torn Burma.” Journal of Burma Studies 24, no. 2 (2020): 229–273. doi:10.1353/jbs.2020.0010.

- Kilcullen, David. The Accidental Guerrilla: Fighting Small Wars in the Midst of a Big One. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Lakhani, Nina. Who Killed Berta Caceres?: Dams, Death Squads, and an Indigenous Defender’s Battle for the Planet. London, UK: Verso, 2020.

- Larratt-Smith, Charles. “Navigating Formal and Informal Processes: Civic Organizations, Armed Nonstate Actors, and Nested Governance in Colombia.” Latin American Politics and Society 62, no. 2 (2020): 75–98. doi:10.1017/lap.2019.61.

- Leguizamón, Castillo, and Yeimmy Rocío. “Conflictos Ambientales y Movimientos Sociales: El Caso Del Movimiento Embera Katío En Respuesta a La Construcción de La Represa Urrá (1994-2008).” Memoria y Sociedad 19, no. 39 (2015): 94–105. doi:10.11144/Javeriana.mys19-39.cams.

- Malthaner, Stefan. “Violence, Legitimacy, and Control: The Microdynamics of Support Relationships Between Militant Groups and Their Social Environment.” Civil Wars 17, no. 4 (2015): 425–445. doi:10.1080/13698249.2015.1115575.

- MAPP/OAS. “Octavo Informe Trimestral Del Secretario General al Consejo Permanente.” Misión de Apoyo al Proceso de Paz de La Organización de Estados Americanos (2007): 1–18.

- Mcloughlin, Claire. “When the Virtuous Circle Unravels: Unfair Service Provision and State De-Legitimation in Divided Societies.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12, no. 4 (2018): 527–544. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1482126.

- Ministerio de Justicia. “Caracterización Regional de La Problemática Asociada a Las Drogas Ilícitas En El Departamento de Nariño.” Ministerio de Justicia (2016). https://www.minjusticia.gov.co/servicio-ciudadano/CaracterizacionUsuarios/RE0639_narino.pdf.

- Ministry of National Defence. Democratic Security and Defence Policy. Bogota: Republic of Colombia, 2003.

- Muñoz, Federico Guillermo. “Municipio de Leiva (Nariño): Zona Roja, Historias de Destierro y Escenario de Reconfiguración Narcoparamilitar.” Tendencias 12, no. 2 (2011): 200–229.

- Ñungo, Doris. “Se Realizó Mesa de La Transparencia En El Cañón de Las Hermosas En Chaparral.” Colosal Noticias Flash (2018). https://colosalnoticiasflash.com/se-realizo-mesa-de-la-transparencia-en-el-canon-de-las-hermosas-en-chaparral/.

- Palmer, David Scott. “FONCODES y Su Impacto En La Pacificación En El Perú: Observaciones Generales y El Caso de Ayacucho.” Concertando Para El Desarrollo: Lecciones Aprendidas Del FONCODES En Sus Estrategias de Intervención (2001): 147–175.

- Patiño, Simon, and Ben Miller. “ISAGEN y La Construcción de La Central Hidroeléctrica Río Amoyá-La Esperanza.” Fundacion Ideas para la Paz (FiP) (2016). http://ideaspaz.org/media/website/primer-estudio-caso-isagen-VF.pdf.

- Pinzón, Omar Antonio Herrán. “Las Minorías Étnicas Colombianas En La Constitución Política de 1991.” Prolegómenos: Derechos y Valores 12, no. 24 (2009): 189–212. doi:10.18359/prole.2488.

- Porch, Douglas. Counterinsurgency: Exposing the Myths of the New Way of War. Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Price, Jessica J. “Keystone Organizations versus Clientelism: Understanding Protest Frequency in Indigenous Southern Mexico.” Comparative Politics 51, no. 3 (2019): 407–435. doi:10.5129/001041519X15647434969966.

- Rempe, Dennis M. The Past as Prologue?: A History of US Counterinsurgency Policy in Colombia, 1958-66. Carlisle, USA: Strategic Studies Institute, 2002.

- Rubin, Michael A. “Rebel Territorial Control and Civilian Collective Action in Civil War: Evidence from the Communist Insurgency in the Philippines.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 64, no. 2–3 (2019): 459–489. doi:10.1177/0022002719863844.

- Schmelzle, Cord, and Eric Stollenwerk. “Virtuous or Vicious Circle? Governance Effectiveness and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12, no. 4 (2018): 449–467. doi:10.1080/17502977.2018.1531649.

- Semana. “Bacrim Se Expanden En El Sur Del País.” Semana (2014). https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/bacrim-se-expanden-en-27-departamentos/407958-3.

- Sen, Rumela. Bullets to Ballots: Maoists and the Lure of Democracy in India. Ithaca, USA: Cornell University, 2017.

- Sexton, Renard. “Aid as a Tool Against Insurgency: Evidence from Contested and Controlled Territory in Afghanistan.” American Political Science Review 110, no. 4 (2016): 731–749. doi:10.1017/S0003055416000356.

- Sexton, Renard, and Christoph Zürcher. “Aid, Attitudes, and Insurgency: Evidence from Development Projects in Northern Afghanistan.” American Journal of Political Science ((25 April 2023)). doi:10.1111/ajps.12778.

- Smith, Hazel Anne, and Larry Minear. Humanitarian Diplomacy: Practitioners and Their Craft. Tokyo, Japan: United Nations University Press, 2007.

- Staniland, Paul. “States, Insurgents, and Wartime Political Orders.” Perspectives on Politics 10, no. 2 (2012): 243–264. doi:10.1017/S1537592712000655.

- Tellez, Juan Fernando. “Peace Agreement Design and Public Support for Peace: Evidence from Colombia.” Journal of Peace Research 56, no. 6 (2019): 827–844. doi:10.1177/0022343319853603.

- UNHCHR. ‘Barbacoas: Un Olvido, Muchos Conflictos’. Oficina del Alto Comisionado de Derechos Humanos, 2015. https://www.hchr.org.co/index.php/compilacion-de-noticias/53-victimas/6272-barbacoas-un-olvido-muchos-conflictos.

- Vargas Hernández, Santiago. “El Estado Diferente: Presencias Diferenciadas, Ausencias Deliberadas, y Construccion de Imaginarios En El Sur de Tolima.” Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (2019).

- Verdad, Abierta. “La “Cacería” Del Frente Libertadores Del Sur.” Verdad Abierta (2011). https://verdadabierta.com/la-caceria-del-frente-libertadores-del-sur/.

- Villamizar Herrera, Dario. Las Guerrillas En Colombia: Una Historia Desde Los Orígenes Hasta Los Confines. Bogota, Colombia: Debate, 2017.

- Weintraub, Michael. “Do All Good Things Go Together? Development Assistance and Insurgent Violence in Civil War.” The Journal of Politics 78, no. 4 (2016): 989–1002. doi:10.1086/686026.

- Wood, Elisabeth Jean. “The Ethical Challenges of Field Research in Conflict Zones.” Qualitative Sociology 29, no. 3 (2006): 373–386. doi:10.1007/s11133-006-9027-8.

- Wood, Reed M. “Opportunities to Kill or Incentives for Restraint? Rebel Capabilities, the Origins of Support, and Civilian Victimization in Civil War.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 31, no. 5 (2014): 461–480. doi:10.1177/0738894213510122.

- Worrall, James. “(Re-)Emergent Orders: Understanding the Negotiation(s) of Rebel Governance.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 28, no. 4–5 ((3 September 2017)): 709–733. doi:10.1080/09592318.2017.1322336.

- Yepes, Juan Mauricio Ramirez, Leonardo Villar, and Juliana Aguilar. “Infraestructura de Transporte En Colombia.” Fedesarrollo, Cuadernos de Fedesarrollo 46, (2013): 011563.

- Zeiderman, Austin. “Concrete Peace: Building Security Through Infrastructure in Colombia.” Anthropological Quarterly 93, no. 3 (2020): 497–528. doi:10.1353/anq.2020.0059.

- Zürcher, Christoph. “What Do We (Not) Know About Development Aid and Violence? A Systematic Review.” World Development 98 (2017): 506–522. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.05.013.