ABSTRACT

The role of local government in ensuring cities and town centres are attractive options for shoppers is well documented in the international literature. However, there is a paucity of research on the role and responsibility of local governments in tackling the complex marketing issues facing town and city retailing, particularly in regional and rural areas in Australia. Australian retailing differs markedly from retailing in the UK, U.S.A and Europe in a number of ways including fewer large, global retail stores, fewer large shopping centres and malls, and a slower uptake of online shopping. This paper reports a set of findings from a larger published study on consumer and retailer perceptions of the role of local government in the marketing of city-centre shopping and improving the overall experience for visitors in a regional Australian city. This research was commissioned by the local council. Traders and shoppers (N = 367) were surveyed on their perceptions of various aspects of city shopping. Qualitative data were analysed using the software program Leximancer to extract themes and concepts regarding specific actions the local council should take to improve city shopping and market the CBD to better attract shoppers and visitors. Findings show four main themes requiring council attention, as well as four additional and important retail-related factors identified by participants as the responsibility of the local city council, but which are actually not within the remit of local government. The findings of this study extend existing literature on town centre and small city retail marketing and are valuable for local governments, business associations, marketing organisations and individual business owners. Findings will assist efforts in two crucial activities: the marketing of cities and towns as attractive destinations for shoppers and visitors and improving and enhancing communication between councils and key stakeholders about the role of local government in marketing city-centre retail places

1. Introduction

The main drag was once the heart and soul of many regional Australian cities, but if you walk through a town’s central business district these days, you will often see for-lease signs and shuttered up shops. (Terzon, Parsons, and Ruddick Citation2018, n.p.)

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, local and independent retailers in city centres faced increasing competition from suburban shopping centres, ‘big box’ developments and online retailers (Källström, Persson, and Westergren Citation2021; Millington and Ntounis Citation2017; Parker et al. Citation2017; Slach et al. Citation2020). Over the last decade, governments and retailers in the United Kingdom, Europe and the United States, have focussed on the complex issues facing ‘high streets’, market towns and ‘main streets’. In particular, the imperative for local governments to work with a range of stakeholders to tackle the ‘wicked problem’ of retail decline in towns and cities (Dolega and Lord Citation2020; Hallsworth and Coca-Stefaniak Citation2018; Padilla and Eastlick Citation2009; Peel and Parker Citation2018) and build resilience across the retail sector (Rao and Summers Citation2016; Salgueiro and Erkip Citation2014). This issue is now even more vital given the impact of COVID-19 on retailing in cities (of all sizes) (Kavaratzis and Florek Citation2021; Mortimer et al. Citation2020; Roggeveen and Sethuraman Citation2020).

The retail sector helps create vitality, and importantly adds to the viability of city centres (as well as other retail precincts found in suburbs, villages and towns), and small retailers provide ‘flavour’ and interest to these areas in ways that cannot be replicated by international retailers and national chain stores alone (Alan and Steve Citation2000; Coca-Stefaniak, Parker, and Rees Citation2010; Parker et al. Citation2016). While these larger entities are important elements of any country’s retail industry, it is small and independent traders that play a significant role in local communities, particularly in smaller towns and cities (Grimmer et al. Citation2017; Ian et al. Citation2004). Small stores are more likely to support local makers and producers, to provide local consumers with a wide variety of goods and services and to offer something different from that provided by multinational corporations. Small, niche stores also attract tourists and visitors, and significantly, they keep profits circulating in the local economy (Rybaczewska and Sparks Citation2020). However, with the decline of the retail sector in towns and cities throughout the world coupled with continual changes in consumer shopping behaviour (Clarke et al. Citation2006; Elms et al. Citation2010; Evans, Grimmer, and Grimmer Citation2022; Helm, Kim, and Van Riper Citation2020), marketing, planning and policy scholars have sharpened their focus on the role of local government and key stakeholders in helping to revive retailing in struggling cities and towns.

Local government plays an important role in marketing towns and city centres as attractive retail and service destinations to visitors, workers, residents, tourists and investors. Retailing is important for cities and towns because it is a vital economic, social and cultural activity (Ryu and Swinney Citation2013) and a strong retail sector contributes significantly to economies (national, state and local) and to communities (Calderwood and Davies Citation2012; Clarke and Banga Citation2010; Grimmer, Grimmer, and Mortimer Citation2018).

This paper presents specific findings from a larger published study (Grimmer, Citation2021) which investigated the drivers and barriers of city shopping in a regional Australian city. The research was commissioned by the local council. Retailing in Australia differs markedly from retailing internationally, especially when compared with the UK, U.S.A and Europe, and these differences are discussed later. This paper highlights trader and shopper responses regarding improvements that could be made by the local council to the retail sector and shopping experience. The findings also reveal four specific retail marketing improvements which respondents believe are the responsibility of local government, but which actually fall outside the council’s control.

The key contribution of this paper is the extension of the city marketing literature through an applied study focussing on the role of local governments in marketing city centre retailing and the perceptions and expectations of key stakeholders (traders and shoppers) in this regard. This study broadens the international literature on high street and city centre retailing and contributes to the nascent Australian literature in this field. In this regard, the study identifies four major city retail marketing themes worthy of local government attention, as well as four misconceptions about the ability and scope of local councils to effect change regarding some of the retail-related problems facing city retailing.

This paper is organised as follows. First, a review of the literature on the function of retailing in cities, and the role of local government in marketing retail in towns and cities is presented. This is followed by a brief description of the research context and the method, results and discussion. The paper concludes with the study’s limitations, contributions and implications, as well as suggestions for future research.

2. Literature review

2.1. The function of retailing in cities and towns

Shopping precincts, featuring retail, hospitality and service businesses, are a vital part of local communities and economies, especially so in regional and rural areas where local businesses employ local staff and sell locally produced goods, thus helping small growers, makers and producers. Prior research (e.g. Martin and Patel Citation2011; Rybaczewska and Sparks Citation2020) shows the multiplier effect that occurs in local communities where, compared with money spent at national retailers, more of every dollar paid to independent, small businesses circulates back through the community’s economy.

There is a growing body of literature on the contribution of local retailers in preserving local communities and contributing to a ‘sense of place’ (Mortimer, Grimmer, and Maginn Citation2020; Saraiva, Sa Marques, and Pinho Citation2019). In smaller towns and cities, city centre retailing is less reliant on large chain stores and retailers, instead featuring smaller, independent and local stores. For this reason, local councils and related marketing organisations, in order to better match the needs of local and visitor demographics, are now more routinely called on to consider the best mix of chain and local stores in shopping precincts (Litvin and Rosene Citation2017). At the same time, there is an increasing understanding, particularly research conducted in the United Kingdom (e.g. High Streets Task Force Citation2022; Peel and Parker Citation2018), Western Europe (e.g. Brunetta and Caldarice Citation2014; Morandi Citation2011) and the United States (e.g. Litvin and Rosene Citation2017), that retailing will not continue to be the main or sole reason for city visitation. Whilst remaining important, retail will more often complement services, attractions and ‘experiences’ as the major factors in enticing people to visit city precincts (Lindberg et al. Citation2019; Peel and Parker Citation2018). Local councils, chambers of commerce and marketing organisations are therefore tasked with the ‘juggling’ act of marketing shopping precincts as being attractive for shoppers, as well as showcasing these areas as offering a range of other services and attractions to appeal to other types of visitors.

In this regard, evaluating the recent changes that have taken place in retailing in cities and towns requires an understanding of the function of retail within a city. Retail areas must not only ‘respond sustainably to the needs, wants and desires of different users, consumers and investors’ but also ‘be part of a structure enabling resilient everyday life’ (Karrholm, Nylund, and Prietode la Fuente Citation2014, p. 122). A city offering the ‘full spectrum’ of retail experiences and services should result in a well-functioning retail system, and this includes both private and public factors. A private exchange function facilitates the efficient economic exchange of goods and services, and a public good function contributes to a number of different priorities (Dobson Citation2015). Those priorities include contributing to the sustainability of a precinct, creating a unique sense of place, ensuring equity in accessibility to goods and services and supporting environmentally sustainable and healthy lifestyles (Rao and Summers Citation2016).

2.2. The role of local government in retail place marketing

At the core of retail precinct and place marketing, the role of local government is vitally important. In addition, the work undertaken by local councils, high streets, city centres and downtown areas is supported by formal initiatives such as Business Improvement Districts (BIDS) in the United Kingdom (Donaghy, Findlay, and Sparks Citation2013; Reenstra-Bryant Citation2010; Steel and Symes Citation2005), and marketing organisations such as ‘Main Street U.S.A’, as well as various local trader associations, which all play a role in coordinating and leading efforts to attract visitors and consumers to shopping areas (Grail et al. Citation2019). In Australia, retail precinct marketing in city centres and suburbs is predominantly the responsibility of individual local councils and there is a mix of approaches at the local, state and national levels to encourage support for town or city centre retailing. The larger research study, of which this paper forms a part, is the only known study to consider the role of a local government in city/town centre retail precinct marketing in Australia.

There is increasing literature on the importance of ‘place’ for local communities and local economies (de Noronha, Coca-Stefaniak, and Morrison Citation2017). As mentioned earlier, the role of local government and marketing organisations in promoting and marketing towns and cities as shopping destinations is gaining more focus (Hankinson Citation2010; Litvin and Rosene Citation2017; Skippari, Nyrhinen, and Karjaluoto Citation2017; Teller and Elms Citation2012; Teller, Alexander, and Floh Citation2016; Walzer, Blanke, and Evans Citation2018; Warnaby et al. Citation2004). Retail place marketing research brings together retailing, place marketing, planning, policy and government, and tourism and hospitality scholarship. There is a sizeable body of research from scholars in the United Kingdom who have sought to identify evidence-based strategies for improving the viability and vitality of the high street and other local shopping areas through increasing visitation (e.g. Millington and Ntounis Citation2017; Parker et al. Citation2017), and by examining the notion of ‘resilience’ and ‘adaptation’ in high street retailing (Salgueiro and Erkip Citation2014; Simmie and Martin Citation2010; Wrigley and Dolega Citation2011). In the United Kingdom, the academic focus on retailing, place marketing and high street revitalisation (Millington et al. Citation2018) has emerged alongside government attention in the form of reviews and policy formulation such as the earlier Portas Review (Portas Citation2011), the Grimsey Review (Grimsey Citation2013), The High Street Report led by Sir John Timpson (Timpson, Citation2018), the Grimsey Review 2 and the COVID-19 supplementary report (Grimsey Citation2018; Grimsey et al. Citation2020). A coalition of place management experts formed the High Streets Task Force (www.highstreetstaskforce.org.uk) with the objective of ‘supporting communities and local governments to transform their high streets’ (n.p., 2022).

There are a number of factors highlighted in both government and industry studies, as well as in the academic literature, which remain problematic for city retailing in the context of smaller cities and regional centres. Three important issues, as highlighted in this study, are car parking, empty stores and the appearance of vacant storefronts.

2.3. Car parking

Despite consistent community and media commentary, there is a scarcity of contemporary Australian retail and marketing research on the impact of car parking on the attractiveness of retail centres. An earlier study by Marsden (Citation2006) found, despite assumptions that restricting parking in city centres damages the attractiveness of city centre retailing, the evidence on parking policies did not support this.

2.4. Empty shops

Empty storefronts detract from the visual attractiveness of shopping areas (Coca-Stefaniak et al. Citation2005; Wrigley and Dolega Citation2011) and have a negative impact on business and consumer confidence where they are perceived to reflect both individual business failure (Teller and Elms Citation2012) and the broader failure of a particular retail precinct to support business survival. Talen and Park (Citation2022) explain common causes for retail vacancy including the broader structural transformation of the retail industry, changes in demographics, the rising costs of retail operations, and property owner behaviour.

2.5. The appearance of vacant stores

Empty stores, as well as unkempt and unattractive vacant sites, are visceral evidence of economic decline (Teller and Elms Citation2012) and have a negative impact on retail precincts where they are also considered a barrier to attracting visitors and shoppers (Wrigley and Dolega Citation2011). In addition, empty storefronts that are untidy or unkempt contribute to perceptions around crime, for example, they can lead to the belief that there is a decrease in safety and an increase in crime (Talen and Park Citation2022) in a specific area. Especially when there are several empty and untidy stores in a particular geographic area.

Given the challenges facing small city retailing, this study aimed to examine the perceptions of city retailers and city shoppers regarding the role of the local council in marketing the city centre as a retail and visitor destination.

This study poses three questions:

How do retailers perceive the role of local government in marketing city-centre shopping?

How do consumers perceive the role of local government in marketing city-centre shopping?

What are the differences between retailer and consumer perceptions?

3. Research context

The Australian retail sector has faced significant challenges over the past decade with high-profile retail failures and store closures in the 18 months prior to COVID-19 (Daly Citation2020; Robertson Citation2019). Several factors have contributed to a difficult trading environment for retailers in Australia, including unchanging economic conditions, stagnant wage growth and limits to discretionary household spending. Consumers continue to adapt how they shop (i.e. moving to shopping online and a focussing on ‘experiences’ and services in place of products). Many small and medium enterprise (SME) retailers (which make up the majority of the retail industry in Australia) have not been able to mount an effective response to these changing conditions (Devereux, Grimmer, and Grimmer Citation2020).

The arrival of COVID-19 sped up consumer ‘appetite’ for shopping online and resulted in further business closures and in the loss of jobs in the retail sector (McIlvaine Citation2020; Mortimer et al. Citation2020). City shopping precincts were especially impacted by diminished footfall (Arrieta-Paredes, Hallsworth, and Coca-Stefaniak Citation2020; Maginn and Mortimer Citation2020; Mortimer, Grimmer, and Maginn Citation2020). This has resulted in concerns for the future of many small traders operating physical stores, and the contribution they make to the local economy in the towns and cities in which they operate (Byun et al. Citation2020; Devereux, Grimmer, and Grimmer Citation2020). In addition, restrictions that were placed on physical shopping – such as social distancing measures, enhanced hygiene and cleaning practices, limiting the number of customers in stores, and the need to take appointments for fittings – have contributed, and may yet continue to contribute, to consumer reluctance to shop in physical stores (Daly, Citation2020). In addition, many small and micro retailers in Australia have not developed an ecommerce offering to complement their physical store and meet the needs of ‘connected’ consumers (Grimmer, Grimmer, and Mortimer Citation2018; Pantano et al. Citation2020). Indeed, at the same time the pandemic has dramatically impacted the way retailers and consumers engage, exchange and enact business, Paul and Rosenbaum (Citation2021) argue retailing and consumer services are at a tipping point in an era of globalisation, technology and fierce competition.

Despite the substantial body of international research on town and city retailing and the role of local governments in managing and marketing town centres, to date there has been little research conducted in this area in an Australian context. There are a number of important differences between Australia and retailing in countries such as the UK, U.S.A and Europe, and these differences make an examination of the Australian experience (for example, as presented in this paper) worthy of scholarly attention. First, it can be argued that Australia’s relatively small population (25.6 million) which is spread over a very large land mass of 7,617,930 square kilometres, results in fewer large retailers operating throughout the country, in addition there are fewer big box developments and fewer large shopping malls, as compared with the United States. Second, retailing in Australia is not based on the historical ‘market town’ as exists in many parts of the UK and Europe. Third, Australia has fewer small town and suburban shopping clusters compared with other international locations, and this results in less choice for consumers with regard to both independent and national chains, as well as international retailers. Finally, Australian shoppers were much slower to embrace online shopping than their international counterparts. Online shopping really only accelerated due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and even now in 2023, Australian consumers do not shop online at the same levels as consumers in other countries, particularly in the supermarket/grocery sector.

3.1. The city of Launceston, Tasmania, Australia

The challenges outlined above are manifested at a local level in towns and cities around Australia. This research was conducted in the regional city of Launceston in the southern Australian island state of Tasmania. Tasmania has a population of just over 520,000, and Launceston a population of approximately 68,388 (id.om.au Citation2022). Compared with most mainland states, Tasmania has a small, aging population with relatively high rates of unemployment and underemployment, lower socioeconomic status markers, low population growth and low rates of investment. The retail industry is the second largest employer in Tasmania, making up 11.3% of the total Tasmanian workforce (pre-COVID-19) (Institute for the Study of Social Change Citation2017) with the industry valued at approximately $580.7 million (Department of Treasury and Finance Citation2020).

Unusually for Australia, and despite its modest population, Tasmania has 29 local councils, each with a department of economic development (or equivalent) which has responsibility for businesses development and support for businesses operating within the council area. The local council under investigation (‘City of Launceston’) covers an area of 1,414 km2 and includes the CBD. The council is actively engaged with key stakeholders to market and promote the CBD as attractive for shoppers, visitors, workers and tourists.

4. Method

The aim of this study was to explore the perceptions of two key stakeholder groups – city traders and city shoppers – regarding the role of the local council in ensuring a city attracts shoppers and visitors and provides a high-quality visitor experience. To address this aim and answer the three research questions, the study used data collected as part of a larger retail place marketing study (for more details on the larger study please see Grimmer, Citation2021). This paper reports the specific findings of responses regarding improvements that the local council could undertake to ensure the city is an attractive destination and encourage shopping in the city. The study adopted a cross-sectional approach by examining a collection of respondents at a single point in time. This ‘snapshot’ approach is not designed to capture particular processes of change but is suitable for providing a detailed analysis of a relatively large-scale study of participants (Tharenou, Donohue, and Cooper Citation2007). It should be noted here that this study was conducted as a practical, empirical research project conducted on behalf of the City of Launceston, and as such the study did not adopt a theoretical lens, nor did it develop a conceptual framework.

The overall study made use of a paper-based survey of city retail and service firms (‘traders’) in the CBD, and an online survey of city-centre consumers (‘shoppers’). Both groups were asked a mix of questions using ranking and Likert scales, as well as some qualitative, open-ended questions; the current study discussed in this paper focusses on the specific open-ended question: ‘Please list up to three improvements the City of Launceston specifically could make to improve the overall shopping experience in the city’. The trader surveys were distributed using the ‘drop and collect’ method (see, for example, Brown Citation1987) under which a survey pack was hand-delivered to every retail and service business within the City of Launceston CBD boundary. The drop and collect method results in higher response rates from small business owners than mail, email/online or telephone surveys (e.g. Ibeh, Brock, and Zhou Citation2004; Stedman et al. Citation2019). The survey packs included an information sheet explaining the purpose of the survey and assuring respondents that all responses were confidential and that results would be reported in a generalised way so as to guarantee anonymity. The online survey of city shoppers, administered via the local council’s existing survey platform on its website, also included an electronic version of the information sheet with similar assurances and in addition that respondents were only able to withdraw before they completed and submitted the survey. The online survey was open to anyone aged 18 or over who had experience shopping in the Launceston city centre. The study was approved by the University of Tasmania Tasmanian Social Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee, reference number H0016926.

4.1. City traders

Survey packs were provided to all retailers operating within a defined CBD boundary (N = 250) who were informed the packs would be collected one week later (nonetheless, a small number were mailed back to the researcher). There were 99 completed surveys received, meaning the response rate was 39.6%. Woodside (Citation2014) recommends that 15% (±4%) is an acceptable reply rate for SME surveys (see also Billesback and Walker Citation2003; Dennis Citation2003; Newby, Watson, and Woodliff Citation2003). The response from traders in this study of almost 40% is thus a very good outcome and so the findings can reasonably be applied generally across the population of interest. One returned survey was incomplete, leaving a final usable sample of 98 surveys.

The sample characteristics for the trader respondents can been seen in . Traders classified their business according to one of the nine Australian and New Zealand Standard Industry Classification (ANZSIC) retail sector classification codes (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2008). The two largest sectors of respondents were clothing, footwear and personal accessories (28.6%), and pharmaceutical and other store-based retailing (11.2%). Those who indicated ‘No response’ (33.7%) may have been those that were service businesses and so not represented by the ANZSIC retail codes. Just above half of the respondents had traded in the city between 6 and 25 years, there were 7.1% who had traded less than two years, and 1% did not answer. Micro-businesses, those with 1–4 employees, made up 43.9% of the sample and non-employing businesses that had no staff additional to the owner/manager made up 4.1%. There were 2.0% who used volunteer staff additional to the owner/manager.

Table 1. Trader sample characteristics.

4.2. City shoppers

The online survey of city shoppers was administered through the City of Launceston survey portal, ‘Your Voice, Your Launceston’, hosted on the council’s website (www.launceston.tas.gov.au). This portal was the most effective way to produce a reasonable sample size; rate payers within the council area are familiar with the platform as it is used regularly to collect data on a range of issues including from people residing outside the area but using city facilities and services. The survey was promoted by the council to rate payers. In addition, online surveys are common in academic research in Australia for collecting consumer, policy and commercial data (Loomis and Paterson Citation2018). The survey was accessible for three weeks. There were 268 usable responses received. Respondents were al 18 years of age or over, and the majority of respondents resided in the local government area (N = 222), with 258 (96.1%) having shopped in the CBD in the previous six months. It should be noted here that no additional demographic information was sought by the research client (City of Launceston) and this is discussed later as a limitation in the concluding remarks.

5. Results and discussion

Qualitative data were analysed using the program Leximancer (http://info.leximancer.com). Leximancer is a computer-generated methodology for content analysis of text to reveal concepts, themes and relationships amongst the words therein. This program was selected for the study because it is well-suited to exploratory research, its use reduces researcher bias in terms of coding subjectivity and the software is reliable due to minimal researcher intervention (Sotiriadou, Brouwers, and Le Citation2014). The main outputs are concept maps which use statistics-based algorithms for semantic and relational information to be extracted (Biroscak et al. Citation2017). These maps provide ‘a visually attractive display of the key themes and concepts, their importance and proximity’ (Sotiriadou, Brouwers, and Le Citation2014).

Concepts in Leximancer are collections of words that generally travel together throughout the text. The concepts are clustered into higher-level ‘themes’ when the map is generated. The themes aid interpretation by grouping the clusters of concepts, and are shown as coloured circles on the map. The themes are heat-mapped to indicate importance. This means that the ‘hottest’ or most important theme appears in red, and the next hottest in orange, and so on according to the colour wheel (Leximancer Pty Ltd Citation2018).

Concept maps for all qualitative survey question responses were created for trader and shopper groups.

5.1. Suggestions for specific local council improvements to encourage shopping in the city

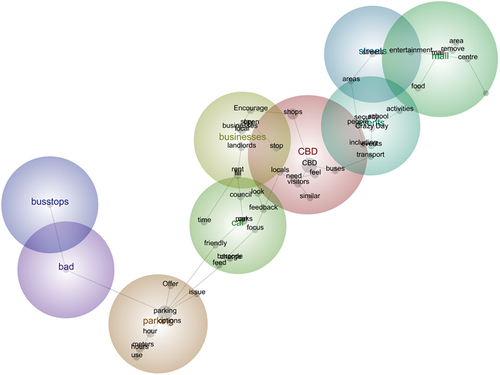

Traders and shoppers were asked to propose improvements that could be made specifically by the local council to improve the overall city shopping experience. shows the Leximancer concept map for trader responses to this open-ended question.

Figure 1. Trader suggestions for specific improvements by the local council to encourage shopping in the city.

The ‘hottest’ theme in terms of importance relates to a range of concepts linked to the CBD. Related concepts include (encouraging and welcoming) visitors to the CBD, (pop-up) shops, (improving the) feel of the CBD, and (keeping) buses (out of the CBD). This theme also overlaps with that of businesses (working with, engaging, supporting). The next theme concerns parking (related to the adjacent theme, car) and contains concepts similar to the previous question: options, hours, offer (−ing free parking), and meters (card as well as coin, cheaper). The next theme of the mall overlaps with those of events and streets, and covers concepts including entertainment, (police) presence, security, activities, (promoting) events, clean (streets), (having an) information booth, and removing (hazards). The remaining themes of bus stops and bad encompass issues of improving safety, relocating bus stops from specific locations, and reducing bad (anti-social) behaviour.

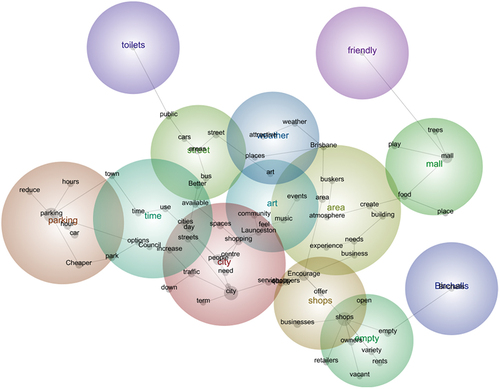

shows the Leximancer concept map for shopper responses to this open-ended question.

Figure 2. Shopper suggestions for specific improvements by the local council to encourage shopping in the city.

Similar to the previous question directed at business owners, the ‘hottest’ theme in terms of importance concerns a number of concepts associated with the city. In addition to what has been previously mentioned, concepts included making Launceston more pedestrianised, encouraging more people (by having inner-city flats), (reducing) traffic on streets, (improving) the shopping experience, and (having more inviting) social spaces. Parking is the next ‘hottest’ theme, related to the adjacent theme, time, with the recurring concepts of reduced/cheaper costs, and hour/hours (free). The nearby theme of street covers a range of suggestions including analysing why some streets ‘work’ and others don’t, reducing one-way streets, closing off some streets at specific times (related to the pedestrianisation suggestion), and removing buses from the city centre. This theme is also linked to the theme of toilets (public, bright, accessible, clean, family, more). The remaining themes cluster into two groups, one around shops, empty and Birchalls (a popular and well-regarded long closed-down store), and the other around area, art, mall, weather and friendly. The former concerns again encouragement for businesses to fill empty shops, especially Birchalls (reduced rents, one-off pop-ups, more variety). The latter concerns the general atmosphere of areas in the city including the mall, public art, buskers, community feel, weather-proofing outdoor shopping areas, beautification (trees), events, (making the city more) attractive, and friendly.

The aim of this study was to investigate trader and shopper perceptions of the role of the local council in marketing the city centre as well as identifying any differences between the two groups. Four main themes for improvement can be identified from this analysis, as well as four ‘misconceptions’ about the marketing responsibilities of the local council, and these are discussed next.

5.2. Local council improvements for encouraging city shopping

The top three suggested improvements to be initiated by the local council from both groups (shown in ) highlight four main themes: (1) interrelated factors associated with the CBD/city; (2) car parking; (3) support for local businesses, and (4) street improvements. In this regard, the perceptions of both groups were similar in terms of highlighting various ‘city factors’ as well as car parking. Traders indicated supporting local businesses was important, while shoppers nominated factors associated with street improvements as topical.

Table 2. Top three themes for local council improvements to encourage city shopping.

5.2.1. CBD/city theme

Results show traders and shoppers nominated similar broad issues associated with the CBD/City as the most important improvement. In this regard, it was suggested the council concentrate on making the city a welcoming place for visitors and encourage visitation broadly though: improving the feel and the ‘vibe’ of the city as well as the shopping experience, providing more inviting places for people to socialise in the city, as well as opportunities for pop-up stores and increasing the number of people living in the city centre. Also associated were suggestions for ensuring bus routes are diverted out of the central pedestrian area, thus improving pedestrianisation, walkability and access. These findings align with research from the United Kingdom identifying a number of factors essential for maintaining the vitality and viability of their high streets (Millington et al. Citation2018; Parker et al. Citation2016, Citation2017) as well as recommendations from recent industry and scholarly resources (for example, High Streets Task Force Citation2022).

5.2.2. Car parking

The issue of car parking was also important for both groups of respondents. Parking in cities of all sizes (specifically lack of parking, cost of parking, and convenience) is a factor consistently perceived by both city business owners and consumers as a pressing issue to be solved by local councils. In small and medium-sized cities, especially in regional and rural areas with small or modest populations, parking availability and cost is seen as a pertinent issue because these areas generally do not have reliable public transport networks and shoppers, workers and visitors to central areas often rely on private cars for transportation. The impact of problems with parking and the resulting effect on footfall, dwell time and therefore spending is under-researched in the contemporary retail marketing literature. While there is a vast literature on parking in the urban planning and transport disciplines, there are fewer recent studies linking parking with retail visitation and spend (Inci Citation2015; Marsden Citation2006), particularly in Australia. Further marketing research which can extend earlier studies (e.g. Mingardo and van Meerkerk, Citation2012) is required to empirically examine the relationship between parking and retail visitation and spending, particularly post-COVID-19. In addition, a research focus on the ‘tension’ between car parking and increased pedestrianisation (as discussed later in this section) is required to assist local councils to continue to support retailers reliant on the provision of car parking, whilst as the same time, making provision for increased walkability and reducing the number of vehicles in city centres and other shopping precincts.

5.2.3. Support for local businesses

Trader respondents nominated local council support for city businesses and business owners as an essential component of city marketing efforts. Respondents highlighted the essential role for local governments to work closely with local stores, engaging and supporting the wider retail ecosystem within the city. This finding supports recommendations from international government reviews (Portas Citation2011; Grimsey Citation2013; Citation2018, UK Government, 2018; Grimsey et al. Citation2020) that partnerships between local traders and local authorities are vital for ensuring high street and city retailing are supported and strengthened through key stakeholder groups working closely together.

5.2.4. Street improvements

The broad theme of ‘streets’ and how the local council and work to improve them, was identified by shopper respondents. This theme incorporated a number of important elements, most notably efforts to enhance the shopper experience through implementing measures to improve pedestrianisation, for example, closing off streets at certain times, and reducing vehicle access in the central area of the city (altering bus routes and shifting bus stops in the core area). Combined with issues around walkability and access, this finding supports studies showing the importance of interrelated measures in creating a distinctive and inclusive ‘sense of place’ for retailers and consumers (Rao and Summers Citation2016).

Pedestrianisation and walkability were also identified as key factors for retail place viability and vitality by Parker et al (Citation2016, Citation2017). Notably, their research focussed on the collaborative activities of stakeholders in improving the performance of the High Street, and factors for which the local authority could actually influence. Multiple factors related to ‘streets’ and ‘streetscapes’, such as traffic flow, parking, walkability, attractiveness, and greening are issues for which the local council in this study has great scope in addressing.

5.3. Misconceptions about the marketing role of the council

Responses from both the trader and consumer groups revealed several misconceptions about the role of the local council in marketing the city as a shopping and visitor destination. Four main themes were consistently identified in the data, from both groups. These four themes involve factors for which the council does not actually have responsibility, nor the ‘power’ to control, as was suggested by respondents. These four themes are: (1) ensuring empty shops are filled; (2) the appearance and upkeep of vacant storefronts; (3) setting business rents, and (4) controlling the mix and type of retail tenancies operating in the CBD. shows a sample of some of the responses from both groups based around these four themes, and these are discussed further in the following section.

Table 3. Misconceptions about the role of the local council.

5.3.1. Empty shops

The theme of empty shops was highlighted in the responses from both groups. This issue was of the most concern to respondents and this supports findings of previous studies that vacant stores are disadvantageous to towns and cities (Darwell Citation2012). Despite the fact individual building owners are responsible for leasing (or selling) stores to retailers and service providers, and that the local government has no authority to ‘fill’ empty shops, a number of respondents indicated council should ensure vacant stores are filled and/or leased. For example:

More shops should be filled, and something needs to be done about Birchalls [a prominent local retail store in the mall which closed down] still being empty after two years and two months.

While the council does play a role in liaising with key stakeholders to attract large businesses and organisations to locate their operations in local council areas, in terms of the leasing of individual stores and buildings, this activity is entirely at the discretion of individual building owners. There is no doubt that empty shops are unsightly and indicate business failure at an individual level (Darwell Citation2012); at a macro level, multiple vacancies can signal an overall downturn in the economic fortunes of a particular shopping precinct (Reenstra-Bryant Citation2010). Retail vacancy rates may also be tied to unemployment figures, in that as unemployment rises, so too do the number of retail vacancies (Mirel Citation2010). The number of empty shops may also indicate the level of ‘wellbeing’ in rural and regional towns (Burns and Willis Citation2011). An approach to addressing the problem of empty storefronts, therefore, may be for local government to work with landlords and real estate agencies (Mirel Citation2010) to create an ‘empty shops register’ which would provide the store address, the length of vacancy and who is responsible for the building’s leasing. A register could also prove useful for new business owners seeking premises by providing a ‘one-stop’ shop to access information about stores available for rent. There is currently limited scholarly research on the problem of empty shops. The findings of this study indicate empty shops, as well as the appearance of unkempt storefronts (an additional factor identified by respondents discussed next) are important issues that require attention from a range of key stakeholders and warrant further academic attention.

5.3.2. Appearance of vacant storefronts

Closely related to concerns about the number of empty shops, respondents noted problems with the appearance and upkeep of vacant buildings, particularly shopfronts. For example:

There needs to be less (sic) empty shops and also a program to clean up some of the facades.

5.3.3. Business rents

Shopper respondents highlighted the issue of retail rents as a factor that should be addressed by the council. In this respect, and again linked to the problem of empty stores, respondents believe high retail rents are a factor in business failure and resulting in vacant shopfronts in the city. For example:

Make shop rents more affordable for tenants so they can stay in the city heart.

This finding suggests that respondents are not aware that it is individual building owners, not the council, who set lease terms and rents for retail and service business tenants. Studies examining the relationship between retail rents and the tenant/retail mix have considered this issue within the context of shopping malls and managed shopping centres (Des Rosiers, Theriault, and Lavoie Citation2009; Yuo et al. Citation2010) where both the tenant mix and retail rents are controlled simultaneously by the centre or mall manager (Zhang, van Duijn, and van der Vlist Citation2020). However, in a city centre, ‘high street’ or ‘main street’ shopping district, where buildings are individually owned, there is no overall control of retail rents which will vary enormously from building to building within particular areas. Relatively few studies have considered retail rents in shopping districts (i.e. non-managed shopping areas). Previous studies by Koster, Pasidis, and Van Ommeren (Citation2019) and Teulings, Ossokina, and Svitak (Citation2017) have examined, respectively, the relationship between footfall, tenant mix (discussed below) and retail rents, and the link between land use and distance decay in retail rents from the centre of a shopping area. A further study found areas with a higher tenant mix can command higher retail rents compared with areas with lower tenant mix (Zhang, van Duijn, and van der Vlist Citation2020). Whilst the council does set and collect business rates (as opposed to rents) some respondents indicated the council should play a role in setting leases and rental amounts for individual businesses. It may be that shopper respondents are not making the distinction between business ‘rates’ and business ‘rents’.

5.3.4. Retail mix and tenancy type

Shopper respondents also reported that the mix and type of retail tenancies (‘retail mix’ or ‘tenant mix’) in the city was not sufficient and required improvement. For example:

Too many boring and pedestrian businesses with little to no reason to shop there.

This finding supports previous studies which have found the retail tenant mix is important because consumers prefer shopping districts which provide a wide range of goods and services (Glaeser, Kolko, and Saiz Citation2001; Talen and Jeong Citation2019b), allowing a wider choice and reducing transport and search costs (Koster, Pasidis, and Van Ommeren Citation2019; Teller Citation2008; Teller and Reutterer Citation2008). Retail agglomeration promotes consumer ‘trip-chaining’ behaviour (Koster, Pasidis, and Van Ommeren Citation2019), and in the context of shopping areas (as opposed to shopping malls or centres), those with a higher retail mix, allow for greater levels of ‘trip-chaining’ and footfall (Teller Citation2008). In the context of this study, local government does not have responsibility for the types of retail (or service or hospitality) businesses leasing storefronts in the city. Zhang, van Duijn, and van der Vlist (Citation2020) highlight areas with a diverse mix of retail tenants contribute to the image and attractiveness of the shopping area, and importantly that the tenant or retail mix is outside the control of individual building owners and local government. Findings from previous studies regarding links between areas with a greater retail mix and accompanying higher retail rents (as discussed above) would appear to be diametrically opposed with findings from this study. Respondents suggest the local government should ensure a greater retail mix (which according to prior research will result in higher retail rents), whilst at the same time associating store closures with high rents. In this regard, local government has no direct influence over the retail mix, the rate of retail rents nor store closures. A solution to solving the retail mix in some smaller towns and cities may lie in introducing or strengthening zoning regulations (Talen and Jeong Citation2019a). For example, for cities without business zoning regulations, it may be beneficial to introduce legislation/zoning requirements for different areas in the CBD to assist with achieving an optimal retail/business mix in particular sections of cities and towns. The challenge for small towns such as Launceston is that the CBD is too small to divide into distinctive areas. In larger cities it is easier and much more feasible to attempt to separate areas themed around shopping, dining, entertainment and activities, culture and history. Therefore, urban policies focussing on issues of land ownership, access and management (Dobson Citation2016) will be increasingly important for smaller cities to help local government make decisions about optimising the retail/tenant mix.

6. Conclusion

6.1. Contribution and implications

This study makes a contribution by extending the retail place marketing literature, especially research focussed on the problems facing the high street, and small cities, and the role of local governments in assisting efforts to attract visitation (High Streets Task Force Citation2022; Millington and Ntounis Citation2017; Millington et al. Citation2018; Parker et al. Citation2016, Citation2017; Peel and Parker Citation2018). In this regard, the findings of this study identify specific small city marketing factors that demand attention from local government from the perspective of two important stakeholder groups – traders and shoppers. The study also contributes to the nascent Australian city retail marketing literature. This is an important, but still emerging, field of research in the Australian retail context (*Author name redacted, 2021; Grimmer and Vorobjovas-Pinta Citation2019). This study is one of few incorporating feedback from both retailers and consumers on the role of the local council in ensuring city centres are attractive places for shoppers and visitors.

This research has a number of practical implications. First, the findings are valuable for local governments by providing insights into how local governments can best meet the needs of city centre traders by identifying those factors which are important for maintaining the vitality and vibrancy of retail trade in small cities. These include issues involving sufficient, convenient and affordable car parking, making improvements to city streets (particularly encouraging pedestrianisation) and engaging with and supporting business owners. The findings will also enable business owners and shoppers to better understand the role of the local councils in addressing the challenges facing town and city centre retailing. This is important, so that both groups can be encouraged to set realistic expectations about the scope (and limitations) of the marketing role of local government which will lead to the formation of appropriate partnerships to address the factors identified in the study. The findings of this study provide the opportunity to propose some broader policy recommendations related to small retailing in cities:

Support city traders to develop an understanding of the role of retailing in their city and the positioning of the city as offering a specialty shopping experience not to be found in other non-city locations;

City traders supported to develop their own individual ‘differentiation’ strategy to ensure that their product/services offerings are unique and/or not available from other stores, particularly those outside the city;

City traders supported to ensure high quality customer service is a priority for their businesses, recognising the importance of customer loyalty for encouraging repeat business and positive word of mouth;

City traders to work collaboratively with other complementary businesses in the city to leverage the power of collaborative marketing and encourage visitation to an entire precinct in addition to individual stores;

Local governments and trader associations to provide skills development workshops for retailers highlighting the changes in the retail sector and changes in consumer shopping behaviour, retail trends and opportunities presented by multi-channel retailing (in-store, online, mobile, app), collaborative marketing and contemporary retail strategy;

Developing strategic approaches to dealing with the visual aspect of empty shops which could include a public register of landlords who own empty shops and putting the onus on building owners to improve the appearance of empty stores, and

Consideration of policy development that allows for multi-use of some retail tenancies (e.g. a shop during the day, café/bar at night) and allows for complementary businesses to rent a single premise.

The findings also demonstrate the need for local governments to clearly articulate to their rate payers, local business owners and visitors to the city, what their role is in marketing local shopping precincts, and importantly, the limitations of their remit. In this regard, it is recommended that local councils develop strategic communication strategies to better inform key stakeholders about council’s role and responsibility (as well as council’s limitations) regarding issues such as vacant stores, appearance and upkeep of shopfronts and business rents. Through improved communication with business owners, building owners, local residents, visitors and other key stakeholders, local governments can continue to improve their important contribution to the future of retailing in towns and cities. It is also recommended that, where relevant, local councils develop a series of programs to address the concerns (misconceptions) raised in this research. It is clear from the findings of this study that the retail mix and the type of retailers in a CBD area are important for shoppers, so councils could be advised to develop policies which would allow them to have greater control over the types (and mix) of retail and service businesses operating stores in specific areas of the city.

6.2. Limitations and future research

Five limitations of the study provide potential opportunities for future research. First, data were collected within one local council area in one state in Australia. Tasmania has a relatively small population with low socio-economic status indicators and low levels of population growth (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2020). The study could be replicated in other local council areas, including areas with higher rates of population growth and stronger economic and social indicators. Second, the study employed a self-report survey for traders and a single informant from each of the businesses; this may have impacted the outcomes. It is also noted that many of the traders surveyed were non-employing or micro businesses (staffed predominantly by the owner/manager). Future research could gain a greater range of views from multiple informants including, where appropriate, retail employees. Third, the use of an online survey for consumers precluded shopper respondents who are not digitally educated or who may not have known of the survey. A customer intercept survey could be used in further research, or a paper-based survey delivered to homes in the council area. Fourth, demographic information such as gender, education and occupation were not sought by the study’s funder. In future research, this information, as well as information about consumer orientation and trip purpose would be very useful to collect, to help provide a deeper analysis of various perceptions of city shopping. It should be noted that this research was conducted just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and so the impact of coronavirus on retailing and consumer shopping behaviour was not a factor in the study. Despite the timing of the study, the findings remain salient for contributing to improving the retail experience in small cities. An extension of this research would use this study as a baseline and examine any changes in perceptions about the role of local government as well as examining the response to the findings of this study in terms of actions taken by the council and the response from retailers and consumers. This is one of the few-known Australian studies investigating the role of local government in city centre marketing. As such, along with the published findings from the larger study (author name redacted, 2021), recommendations for further academic research in this field could include a comparative study between Australia and city retailing in other international contexts. While there are broad similarities between Australian retail places and international examples on a range of issues, for example local government efforts to market city centres and shopping areas, as well as small trader concerns about competition from online shopping, the Australian context is quite unique. As previously discussed, there are a number of differences between Australian retailing and retail in the UK, U.S.A and Europe, and in the ways in which local governments are involved in marketing city retailing which would be worthwhile investigating and documenting, for example the nascent (in Australia) BID approach and the Main Street U.S.A movement would contribute to the growing field of small city retail research in the Australian context.

6.3. Concluding remarks

The ongoing impact of broad structural changes in economies and the global coronavirus pandemic are contributing to significant shifts in retailing and in consumer shopping behaviour. The ability for consumers to easily access goods and services provided by both individual retailers and via retail precincts has always been important, and even more so during the COVID-19 pandemic. Local retail stores continue to play a vital role in enabling people to shop locally for essential household items, especially during the global health crisis, as well as making a key contribution to local economies and communities. It is therefore critical that individual retailers, local governments and consumers, work together to ensure the resilience and ongoing sustainability of local shopping precincts. The role of local governments in leading efforts to ensure retail places such as small cities, town and suburbs remain attractive for visitors and shoppers is high on the policy agenda. In addition, the ability for local councils to be able to communicate effectively with key stakeholders regarding their efforts in marketing city retailing is an important part of the overall effort in ensuring city retailing in small cities remains vibrant and viable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Louise Grimmer

Louise is Senior Lecturer in Retail Marketing in the Tasmanian School of Business and Economics at the University of Tasmania. Her research focuses on small stores, city retailing, retail place marketing and consumer behaviour. She is a Fulbright Scholar and Senior Fellow of the Institute of Place Management.

References

- Alan, G. H., and W. Steve. 2000. “Local Resistance to Larger Retailers: The Example of Market Towns and the Food Superstore in the UK.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 28 (4–5): 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550010319959.

- Arrieta-Paredes, M. P., A. G. Hallsworth, and J. A. Coca-Stefaniak. 2020. “Small Shop Survival-The Financial Response to a Global Financial Crisis.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 53:101984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101984.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008. “1292.0 Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC), 2006.” ( Revision 1.0). https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/0/20C5B5A4F46DF95BCA25711F00146D75?opendocument.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2020. “8501.0 Retail Trade, Australia, June.” https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/mf/8501.0.

- Balsas, C. J. L. 2014. “Downtown Resilience: A Review of Recent (Re)developments in Tempe, Arizona.” Cities 36:158–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2012.10.002.

- Billesback, T. J., and J. Walker. 2003. “Stalking Goliath: What Successful Businesses are Doing Against Major Discount Chains.” Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship 15 (2): 1–17.

- Biroscak, B. J., J. E. Scott, J. H. Lindenberger, and C. A. Bryant. 2017. “Leximancer Software as a Research Tool for Social Marketers: Application to a Content Analysis.” Social Marketing Quarterly 23 (3): 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524500417700826.

- Brown, S. 1987. “Drop and Collect Surveys: A Neglected Research Technique?” Marketing Intelligence & Planning 5 (1): 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb045742.

- Brunetta, G., and O. Caldarice. 2014. “Self-Organisation and Retail-Led Regeneration: A New Territorial Governance within the Italian Context.” Local Economy 24 (4–5): 334–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094214535555.

- Burns, E. A., and E. Willis. 2011. “Empty Shops in Australian Regional Towns as an Index of Rural Wellbeing.” Rural Society 21 (1): 21–31. https://doi.org/10.5172/rsj.2011.21.1.21.

- Byun, S.-E., S. Han, H. Kim, and C. Centrallo. 2020. “US Small Retail businesses’ Perception of Competition: Looking Through a Lens of Fear, Confidence or Cooperation.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 52:101925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101925.

- Calderwood, E., and K. Davies. 2012. “The Trading Profiles of Community Retail Enterprises.” International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management 40 (8): 592–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551211245407.

- Clarke, I., and S. Banga. 2010. “The Economic and Social Role of Small Stores: A Review of UK Evidence.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research 20 (2): 187–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593961003701783.

- Clarke, I., A. Hallsworth, P. Jackson, R. D. Kervenoael, R. P. D. Aguila, and M. Kirkup. 2006. “Retail Restricting and Consumer Choice 1. Long-Term Local Changes in Consumer Behaviour: Portsmouth, 1980-2002.” Environment & Planning A 38 (1): 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37207.

- Coca-Stefaniak, J. A., A. G. Hallsworth, C. Parker, S. Bainbridge, and R. Yuste. 2005. “Decline in the British Small Shop Independent Retail Sector: Exploring European Parallels.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 12 (5): 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2004.11.007.

- Coca-Stefaniak, J. A., C. Parker, and P. Rees. 2010. “Localisation as a Marketing Strategy for Small Retailers.” Journal of Place Management and Development 38 (9): 677–697. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551011062439.

- Daly, J. 2020. “Retail Won’t Snap Back. 3 Reasons Why COVID Has Changed the Way We Shop, Perhaps Forever.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/retail-wont-snap-back-3-reasons-why-covid-has-changed-the-way-we-shop-perhaps-forever-140628.

- Darwell, J. 2012. “The Mail Keeps Coming (Empty Shops).” International Journal of Epidemiology 41 (5): 1237–1240. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys158.

- Dennis, J. W. J. 2003. “Raising Response Rates in Mail Surveys of Small Business Owners: Results of an Experiment.” Journal of Small Business Management 41 (3): 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-627X.00082.

- de Noronha, I., J. A. Coca-Stefaniak, and A. M. Morrison. 2017. “Confused Branding? An Exploratory Study of Place Branding Practices Among Place Management Professionals.” Cities 66:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2017.04.001.

- Department of Treasury and Finance. 2020. “Retail Trade (ABS Cat No 8501.0).” https://www.treasury.tas.gov.au/Documents/Retail-Trade.pdf.

- Des Rosiers, F., M. Theriault, and C. Lavoie. 2009. “Retail Concentration and Shopping Center Rents - a Comparison of Two Cities.” Journal of Real Estate Research 31 (2): 165–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/10835547.2009.12091241.

- Devereux, E., L. Grimmer, and M. Grimmer. 2020. “Consumer Engagement on Social Media: Evidence from Small Retailers.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 19 (2): 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1800.

- Dobson, J. 2015. “Britain’s Town Centres: From Resilience to Transition.” Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal 8 (4): 347–355.

- Dobson, J. 2016. “Rethinking Town Centre Economies: Beyond the ‘Place or people’ Binary.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 31 (3): 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094216640472.

- Dolega, L., and A. Lord. 2020. “Exploring the Geography of Retail Success and Decline: A Case Study of the Liverpool City Region.” Cities 96:102456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.102456.

- Donaghy, M., A. Findlay, and L. Sparks. 2013. “The Evaluation of Business Improvement Districts: Questions and Issues from the Scottish Experience.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 28 (5): 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094213488517.

- Elms, J., C. Canning, R. De Kervenoael, P. Whysall, A. Hallsworth, and J. Fernie. 2010. “30 Years of Retail Change: Where (And How) Do You Shop?” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 38 (11): 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551011085920.

- Evans, F., L. Grimmer, and M. Grimmer. 2022. “Consumer Orientations of Secondhand Fashion Shoppers: The Role of Shopping Frequency and Store Type.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 67:102991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102991.

- Glaeser, E. L., J. Kolko, and A. Saiz. 2001. “Consumer City.” Journal of Economic Geography 1 (1): 27–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/1.1.27.

- Grail, J., C. Mitton, N. Ntounis, C. Parker, S. Quin, C. Steadman, and G. Warnaby. 2019. “Business Improvement Districts in the UK: A Review and Synthesis.” Journal of Place Management and Development 13 (1): 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-11-2019-0097.

- Grimmer, L., M. Grimmer, and G. Mortimer. 2018. “The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: A Replicated Study of Small Retail Firm Resources.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 44:54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.05.012.

- Grimmer, L., M. Miles, J. Byrom, and M. Grimmer. 2017. “The Impact of Resources and Strategic Orientation on Small Retail Firm Performance.” Journal of Small Business Management 55 (S1): 7–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12368.

- Grimmer, L., and O. Vorobjovas-Pinta. 2019. “From the Sharing Economy to the Visitor Economy: The Impact on Small Retailers.” International Journal of Tourism Cities 6 (1): 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-01-2019-0015.

- Grimsey, B. 2013. “The Grimsey Review: An Alternative Future for the High Street.” The Grimsey Review Team: United Kingdom.

- Grimsey, B. 2018. “The Grimsey Review 2.” The Grimsey Review Team: United Kingdom.

- Grimsey, B., K. Perrior, R. Trevalyan, N. Hood, J. Sadek, N. Schneider, M. Baker, C. Shellard, and K. Cassidy. 2020. “Grimsey Review COVID-19 Supplement for Town Centres: Build Back Better.” The Grimsey Review Team: United Kingdom.

- Hallsworth, A. G., and J. A. Coca-Stefaniak. 2018. “National High Street Retail and Town Centre Policy at a Cross Roads in England and Wales.” Cities 79:134–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.03.002.

- Hankinson, G. 2010. “Place Branding Research: A Cross-Disciplinary Agenda and the Views of Practitioners.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 6 (4): 300–315. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2010.29.

- Helm, S., S. H. Kim, and S. Van Riper. 2020. “Navigating the ‘Retail apocalypse’: A Framework of Consumer Evaluations of the New Retail Landscape.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 54:101683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.09.015.

- High Streets Task Force. 2022. “High Streets Task Force.” www.highstreetstaskforce.org.uk.

- Ian, C., H. Alan, J. Peter, D. K. Ronan, P. D. A. Rossana, and K. Malcolm. 2004. “Retail Competition and Consumer Choice: Contextualising the” Food Deserts“debate.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 32 (2): 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550410521761.

- Ibeh, K., J. K. U. Brock, and Y. J. Zhou. 2004. “The Drop and Collect Survey Among Industrial Populations: Theory and Empirical Evidence.” Industrial Marketing Management 33 (2): 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2002.08.001.

- id.om.au. 2022. “City of Launceston Community Profile.” https://profile.id.com.au/launceston.

- Inci, E. 2015. “A Review of the Economics of Parking.” Economics of Transportation 4 (1–2): 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecotra.2014.11.001.

- Institute for the Study of Social Change. 2017. Insight Two: Tasmania’s Workforce by Industry Sector. Tasmania, Australia: University of Tasmania.

- Källström, L., S. Persson, and J. Westergren. 2021. “The Role of Place in City Centre Retailing.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 17 (1): 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-019-00158-y.

- Karrholm, M., K. Nylund, and P. Prietode la Fuente. 2014. “Spatial Resilience and Urban Planning: Addressing the Interdependence of Urban Retail Areas.” Cities 36:121–130.

- Katyoka, M., and P. Wyatt. 2008. “An Investigation of the Nature of Vacant Commercial and Industrial Property.” Planning, Practice & Research 23 (1): 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450802076704.

- Kavaratzis, M., and M. Florek. 2021. “Special Section: The Future of Place Branding.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 17 (1): 63–64. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41254-020-00197-w.

- Koster, H. R. A., I. Pasidis, and J. Van Ommeren. 2019. “Shopping Externalities and Retail Concentration: Evidence from Dutch Shopping Streets.” Journal of Urban Economics 114:10319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2019.103194.

- Leximancer Pty Ltd. 2018. Leximancer User Guide.” Release 4.5. Copyright, Leximancer Pty Ltd.

- Lindberg, M., K. Johansson, H. Karlberg, and J. Balogh. 2019. “Place Innovative Synergies for City Center Attractiveness: A Matter of Experiencing Retail and Retailing Experiences.” Urban Planning 4 (1): 91–105. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v4i1.1640.

- Litvin, S., and J. Rosene. 2017. “Revisiting Main Street: Balancing Chain and Local Retail in a Historic City’s Downtown.” Journal of Travel Research 56 (6): 821–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516652237.

- Loomis, D. K., and S. Paterson. 2018. “A Comparison of Data Collection Methods: Mail versus Online Surveys.” Journal of Leisure Research 49 (2): 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2018.1494418.

- Madanipour, A. 2018. “Temporary Use of Space: Urban Processes Between Flexibility, Opportunity and Precarity.” Urban Studies 55 (5): 1093–1110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017705546.

- Maginn, P., and G. Mortimer. 2020. “How Covid All but Killed the Australian CBD.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/how-covid-all-but-killed-the-australian-cbd-147848.

- Marsden, G. 2006. “The Evidence Base for Parking Policies—A Review.” Transport Policy 13 (6): 447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2006.05.009.

- Martin, G., and A. Patel. 2011. Going Local: Quantifying the Economic Impacts of Buying from Locally Owned Businesses in Portland, Maine. Augusta ME, USA: Maine Center for Economic Policy.

- McIlvaine, H. 2020. “Which Retailers Have Closed Stores so Far?” Inside Retail. https://insideretail.com.au/news/updated-which-retailers-have-closed-stores-so-far-202004.

- Millington, S., and N. Ntounis. 2017. “Repositioning the High Street: Evidence and Reflection from the UK.” Journal of Place Management and Development 10 (4): 364–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-08-2017-0077.

- Millington, S. N., C. Ntounis, S. Parker, G. Quin, G. Roberts, and C. Steadman. 2018. High Street 2030: Achieving Change. Manchester, United Kingdom: Institute of Place Management.

- Mingardo, G., and J. Van Meerkerk. 2012. “Is Parking Supply Related to Turnover of Shopping Areas? The Case of the Netherlands.” Journal of Retailing & Consumer Services 19 (2): 195–201.

- Mirel, D. 2010. “United Front: Real Estate Managers and Municipalities Tackle Empty Storefronts by Working Together.” Journal of Property Management 75 (3): 36–40.

- Morandi, C. 2011. “Retail and Public Policies Supporting the Attractiveness of Italian Town Centres: The Case of the Milan Central Districts.” Urban Design International 16 (3): 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2010.27.

- Mortimer, G. J., J. Bowden, L. Pallant, Grimmer, and M. Grimmer. 2020. “COVID-19 Has Changed the Future of Retail: There’s Plenty More Automation in Store.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/covid-19-haschanged-the-future-of-retail-theres-plenty-more-automation-in-store-139025.

- Mortimer, G., L. Grimmer, and P. Maginn. 2020. “The Suburbs are the Future of Post-COVID Retail.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-suburbs-are-the-future-of-post-covid-retail-148802.

- Newby, R., J. Watson, and D. Woodliff. 2003. “SME Survey Methodology: Response Rates, Data Quality and Cost Effectiveness.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 28 (2): 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1540-6520.2003.00037.x.

- Padilla, C., and M. A. Eastlick. 2009. “Exploring Urban Retailing and CBD Revitalization Strategies.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 37 (1): 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550910927135.

- Pantano, E., G. Pizzi, D. Scarpi, and C. Dennis. 2020. “Competing During a pandemic?” Retailers’ Ups and Downs During the COVID-19 Outbreak.” Journal of Business Research 116:209–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.036.

- Parker, C., N. Ntounis, S. Millington, S. Quin, and F. R. Catillo-Villar. 2017. “Improving the Vitality and Viability of the UK High Street by 2020: Identifying Priorities and a Framework for Action.” Journal of Place Management and Development 10 (4): 310–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-03-2017-0032.

- Parker, C., N. Ntounis, S. Quin, and S. Millington. 2016. “High Street UK 2020 Project Report: Identifying Factors That Influence Vitality and Viability.” Institute of Place Management: Manchester.

- Paul, J., and M. Rosenbaum. 2021. “Retailing and Consumer Services at a Tipping Point: New Conceptual Frameworks and Theoretical Models.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 54:101977. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101977.

- Peel, D., and C. Parker. 2018. “Planning and Governance Issues in the Restructuring of the High Street.” Journal of Place Management and Development 10 (4): 404–418. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMD-01-2017-0008.

- Portas, M. 2011. The Portas Review: An Independent Review into the Future of Our High Streets. United Kingdom: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, UK Government.

- Rao, F., and R. J. Summers. 2016. “Planning for Retail Resilience.” Cities 58:97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.05.002.

- Reenstra-Bryant, R. 2010. “Evaluations of Business Improvement Districts: Ensuring Relevance for Individual Communities.” Public Performance & Management Review 33 (3): 509–523. https://doi.org/10.2753/PMR1530-9576330310.

- Robertson, A. 2019. “Australian Retailers Shut Down by Foreign Competition.” ABC News Online. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-02-21/australian-retailers-shut-down-by-foreign-competition/10832062.

- Roggeveen, A. L., and R. Sethuraman. 2020. “How the COVID-19 Pandemic May Change the World of Retailing.” Journal of Retailing 96 (2): 169–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2020.04.002.

- Rybaczewska, M., and L. Sparks. 2020. “Locally-Owned Convenience Stores and the Local Economy.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 52:101939. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101939.

- Ryu, J., and J. Swinney. 2013. “Branding Smallville: Community Place Brand Communication and Business Owner Perceptions of Performance in Small Town America.” Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 9 (2): 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2013.6.

- Salgueiro, T. B., and F. Erkip. 2014. “Retail Planning and Urban Resilience. An Introduction to the Special Issue.” Cities 36:107–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.01.007.

- Saraiva, M., T. Sa Marques, and P. Pinho. 2019. “Vacant Shops in a Crisis Period – a Morphological Analysis in Portuguese Medium-Sized Cities.” Planning Practice & Research 34 (3): 255–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2019.1590766.

- Simmie, J., and R. Martin. 2010. “The Economic Resilience of Regions: Towards an Evolutionary Approach.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy & Society 3 (1): 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp029.

- Skippari, M., J. Nyrhinen, and H. Karjaluoto. 2017. “The Impact of Consumer Local Engagement on Local Store Patronage and Customer Satisfaction.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research 27 (5): 485–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2017.1383289.

- Slach, O., A. Nováček, V. Bosák, and L. Krtička. 2020. “Mega-Retail-Led Regeneration in the Shrinking City: Panacea or Placebo?” Cities 104:102799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102799.

- Sotiriadou, P., J. Brouwers, and T. A. Le. 2014. “Choosing a Qualitative Data Analysis Tool: A Comparison of NVivo and Leximancer.” Annals of Leisure Research 17 (2): 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2014.902292.

- Stedman, R. C., N. A. Connelly, T. A. Heberlein, D. J. Decker, and S. B. Allred. 2019. “The End of the (Research) World as We Know It? Understanding and Coping with Declining Response Rates to Mail Surveys.” Society & Natural Resources 32 (10): 1139–1154. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2019.1587127.

- Steel, M., and M. Symes. 2005. “The Privatisation of Public Space? The American Experience of Business Improvement Districts and Their Relationship to Local Governance.” Local Government Studies 31 (3): 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930500095152.

- Talen, E., and H. Jeong. 2019a. “Street Rules: Does Zoning Support Main Street?” Urban Design International 24 (3): 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-018-0076-x.

- Talen, E., and H. Jeong. 2019b. “What is the Value of ‘Main Street’? Framing and Testing the Arguments.” Cities 92:208–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.03.023.

- Talen, E., and J. Park. 2022. “Understanding Urban Retail Vacancy.” Urban Affairs Review 58 (5): 1411–1437. https://doi.org/10.1177/10780874211025451.

- Teller, C. 2008. “Shopping Streets versus Shopping Malls – Determinants of Agglomeration Format Attractiveness from the consumers’ Point of View.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution & Consumer Research 18:381–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593960802299452.

- Teller, C., A. Alexander, and A. Floh. 2016. “The Impact of Competition and Cooperation on the Performance of a Retail Agglomeration and Its Stores.” Industrial Marketing Management 52:6–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.07.010.

- Teller, C., and J. Elms. 2012. “Urban Place Marketing and Retail Agglomeration Customers.” Journal of Marketing Management 28 (5–6): 546–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2010.517710.

- Teller, C., and T. Reutterer. 2008. “The Evolving Concept of Retail Attractiveness: What Makes Retail Agglomerations Attractive When Customer Shop at Them?” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 15 (3): 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2007.03.003.

- Terzon, E., A. Parsons, and B. Ruddick. 2018. “Small Town Shops are Struggling, but Some Regional Australian Cities are Fighting Back.” ABC News Online, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2018-11-18/retail-in-regional-cities-struggling-fighting-back/10503598.

- Teulings, C. N., I. Ossokina, and J. Svitak. 2017. “The Urban Economics of Retail.” CPB Discussion Paper 352, Centraal Planbureau (CPB).

- Tharenou, P., R. Donohue, and B. Cooper. 2007. Management Research Methods. Cambridge University Press.

- Timpson, J. 2018. “The High Street Report.” Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, UK Government: United Kingdom.

- Walzer, N., A. Blanke, and M. Evans. 2018. “Factors Affecting Retail Sales in Small and Mid-Size Cities.” Community Development 49 (4): 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2018.1474238.

- Warnaby, G., D. Bennison, B. J. Davies, and H. Hughes. 2004. “People and Partnerships: Marketing Urban Retailing.” International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management 32 (11): 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550410564773.