ABSTRACT

Virtual agents (VAs) used by retailers for online contacts with customers are becoming increasingly common. So far, however, many of them display relatively poor performance in conversations with users – and this is expected to continue for still some time. The present study examines one aspect of conversations between VAs and humans, namely what happens when a VA openly discloses its knowledge gaps versus when it makes attempt to conceal them in a setting in which it cannot answer user questions. A between-subjects experiment with a manipulated VA, and with perceived service quality as the main dependent variable, shows that a display of a high level of ability to answer user questions boosts perceived service quality. The study also offers explanations of this outcome in terms of mediating variables (perceived VA competence, openness to disclose own knowledge limits, usefulness, and learning-related benefits).

1. Introduction

As retailing is becoming increasingly online-based, many retailers have introduced virtual agents (VAs) with which the customer can interact in online settings (Gnewuch, Morana, and Maedche Citation2017; Suich Bass Citation2018). VAs, sometimes also referred to as chatbots, virtual employees, virtual shopping agents, virtual customer service agents, and conversational agents (Crolic et al. Citation2022; Gnewuch, Morana, and Maedche Citation2017; Köhler et al., Citation2011), are computer programs that can provide cost-efficient and consistent customer service in several ways, such as dealing with complaints and helping customers find suitable products within a retailer’s assortment (Akhtar, Neidhardt, and Werthner Citation2019; Tan and Liew Citation2020). They can also capture market intelligence and engage in cross-selling opportunities (Köhler et al. Citation2011). And they will not be subject to the same type of stress-related reactions that are common among human employees, who often have to pay a high toll for constant exposure to customers (cf. Bromuri et al. Citation2020).

Typically, when a VA is used as a representative of a company, it is screen-based (i.e. it is non-embodied) and is accessible online on a firm’s website or in a mobile telephone app, and it can communicate with the customer in natural language. Many VAs resemble humans also in other ways; they may have a face, a name, a gender, and a voice (Crolic et al. Citation2022). So far, however, many VA applications have been disappointing when it comes to providing convincing conversations (Chaves and Gerosa Citation2021; Gnewuch, Morana, and Maedche Citation2017). The present study examines one particular VA aspect that has hitherto not been subject to empirical studies, namely explicit verbal responses to users’ questions when the VA does not know the answer. The main rationale behind this focus is that VAs will continue to perform at suboptimal levels for still some time. It may be noted that even ChatGPT, a chatbot that has stunned many humans with its abilities (Taecharungroj Citation2023), frequently fails to answer questions correctly. Yet, it makes attempts to conceal this by producing ‘hallucinations’; it provides nonsensical information that looks plausible (Taecharungroj Citation2023). In any event, one may foresee many situations when VAs are not able to answer questions – but they need to respond anyway, in one way or another. Such responses can vary in the extent to which a VA displays an ability to answer users’ question, and this particular aspect is assessed in the present study.

In a human-to-human context, one would expect that a person’s low ability to answer a question in a particular subject domain is an indication of the person’s lack of knowledge about the domain. In the light of the rapid progress of artificial intelligence, and its documented ability to outperform humans in settings such as chess and medical diagnosis, one may also expect that a VA that displays a lack of knowledge would disconfirm expectations about its (allegedly) superior information processing abilities. Indeed, people in general believe that AI-based recommenders are more competent than human recommenders, at least for utilitarian-focused recommendations (Longoni and Cian Citation2022). If such beliefs are not confirmed, however, the expected result is attenuated overall evaluations of the VA. This outcome thus implies that VAs should avoid displaying that it cannot answer questions.

Alternative outcomes, however, do exist. Again in a human-to-human setting, a display of a low ability to answer a question can indicate a willingness to openly disclose that one has knowledge gaps and thus personal limitations. This is a facet of humility (Exline and Geyer Citation2004; Owens, Johnson, and Mitchell Citation2013), a positively valenced person characteristic in many contexts (Exline and Geyer Citation2004; Wright et al. Citation2017), which can boost the overall evaluation of the speaker. Given that we humans react to (humanlike) non-human agents in ways that resemble how we react to real humans (Epley Citation2018; Reeves and Nass Citation1996), it is therefore possible that a VA that displays a low ability to answer questions would be rewarded with positive evaluations in a social perception situation. This, then, implies that a VA should not conceal a low ability to answer questions.

Against the backdrop of these rival outcomes, and given that various VAs are increasingly replacing human service agents in online interactions (Crolic et al. Citation2022), the purpose of the present study is to empirically examine effects of VAs’ ability to answer user questions in an assessment with perceived service quality (PSQ) as the main downstream variable. The present study also examines a set of mechanisms by which VAs’ ability to answer questions can influence PSQ. To this end, an experiment was carried out in which a VA was manipulated (low vs. medium vs. high display of an ability to answer user questions). The specific setting for the empirical assessment was a speech-based VA that is able to share knowledge about running shoes. In this setting, then, the main task of the VA is to serve as an advisor (cf. Tan and Liew Citation2020). Moreover, as a specific means to display different levels of an ability to answer questions, the VA’s ability was signaled by its use of the utterance ‘I do not know’ which, in a human-to-human context, is a common reply to an information question when the speaker is unable to supply the requested information (Tsui Citation1991).

An examination along those lines contributes in several ways to existing research on VAs; it contributes to the literature on (a) antecedents to perceived VA knowledge, competence and perceived usefulness, (b) learning benefits for the user from using VAs, and (c) it introduces the notion of intellectual humility in the context of VAs. These contributions are discussed further in section 5.1 below.

2. Theoretical framework and hypotheses

2.1 Conceptual point of departure

A main assumption in the present study is that we humans tend to react to (humanlike) non-humans in ways that are similar to how we react to real humans. This reaction pattern is commonly labelled anthropomorphism, and it can be seen as one of many ways in which people make sense of an unknown stimulus based on a better-known representation of a related stimulus (Epley et al. Citation2008). Typically, it is similarity (e.g. in terms of morphology or conversation style) between a non-human agent and a human agent that triggers anthropomorphism; exposure to a humanlike non-human agent can activate mental content related to real humans, and in the next step this content is applied to the non-human object (Epley Citation2018). Another main assumption in the present study, given anthropomorphism, is that theory about human-to-human interactions (as well as empirical findings based on such theory) can be useful for developing predictions about humans’ interactions with non-human agents. This second assumption serves as the basis for several of the study’s hypotheses.

More specifically, in a human-to-human setting, it is expected that observers in social situations use even minimal cues related to a target to infer various traits of the target (Barasch, Levine, and Schweitzer Citation2016). Previous research has repeatedly revealed that such inferencing occurs given cues about the target’s physical attractiveness, emotional expressions, gender, and age, and in the present study it is assumed that what a target says provides such cues, too. Given anthropomorphism and a conversational setting in which the asker is a human user and the replier is a VA, which is presented as an advisor knowledgeable in a specific domain, it is assumed that perceptions of the ability of a VA to provide answers would serve as a cue for the attribution of several other characteristics to the VA.

2.2 The ability to answer user questions and its consequences

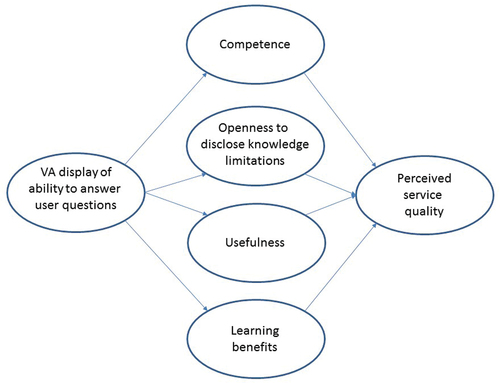

It is hypothesized that a VA’s ability to answer users’ questions influences perceptions of four VA characteristic (competence, openness to disclose knowledge limitations, usefulness, and provision of learning benefits), and of each them is hypothesized to affect perceived service quality (PSQ) in relation to a VA. The selection of these variables was made based on an examination of previous research in various areas in which it was possible to identify variables that were likely to have a potential to be (a) consequences of an ability to answer questions and (b) antecedents to perceived service quality (as an overall evaluation of a service). The selection, then, should be seen as an attempt to integrate parts from existing theories (or existing theoretical arguments) from different fields. An overview of the hypothesized associations is provided in .

First, it is expected that the VA’s ability to provide answers would be positively associated with perceptions about VA competence. Competence is viewed here as a universal dimension in human-to-human perception contexts; it reflects the extent to which a target person is seen as having traits related to abilities such as intelligence, creativity, and efficacy (Fiske, Cuddy, and Glick Citation2007). Moreover, attributions of competence are often based on the target’s communicative acts (Treem Citation2012). One particular act indicative of competence is talk time; the more a target talks about a topic, the more the target is seen as knowledgeable (Littlepage et al. Citation1995). Similarly, cues about a person’s dominance/assertiveness are typically diagnostic for perceptions of the person’s competence (Cuddy, Glick, and Beninger Citation2011). Given that a low ability to answer questions is likely to (a) cut talk time in relation to delivering an answer and (b) signal less assertiveness than answering the question (and given also anthropomorphism), the following is hypothesized:

H1:

The ability of a VA to provide answers to user questions is positively associated with perceptions of VA competence.

However, an unrestricted ability to provide answers may backfire when it comes to attributions of other characteristics: it may reduce the perceived humility of the replier. Indeed, in a human-to-human context, one main facet of humility is an ability to acknowledge one’s imperfections and gaps in knowledge in such a way that it involves a transparent disclosure of personal limits (Exline and Geyer Citation2004; Owens, Johnson, and Mitchell Citation2013; Wright et al. Citation2017). Similarly, intellectual humility is characterized by accepting one’s knowledge gaps rather than denying them or cover them up (Whitcomb et al. Citation2017); an intellectually humble person should be less likely to pretend to know something and can acknowledge that there are gaps in his/her knowledge (Haggard et al. Citation2017). With this view, then, explicitly displaying a low ability to answer a question as a response to a question can signal that the replier is open about his/her knowledge gaps. In the present study, and given again anthropomorphism, it is assumed that an unrestricted ability of a VA to provide answers to users’ questions can indicate that the VA is not open to disclosing that it does not know everything. Therefore, the following is hypothesized:

H2:

The ability of a VA to provide answers to user questions is negatively associated with perceptions of VA openness to disclose its knowledge limitations

Moreover, it is expected that the VA’s ability to provide answers to user questions would affect two additional outcomes: perceived usefulness of the VA and perceived learning benefits. Usefulness is a frequently employed variable in theories of users’ assessments of various technologies. In early studies, usefulness covered the extent to which users believe that a particular technology would enhance their job performance (Davis Citation1993), but in more recent studies of consumers it typically comprises beliefs about a technology as providing benefits in everyday life situations. In the case of synthetic agents, convenience and time savings are examples of such benefits (e.g. Ghazali et al. Citation2020; Hu Citation2021). Here, in the present study, it is hypothesized that a VA presented as knowledgeable in one particular domain would be perceived as more useful if it can indeed answer questions about matters in the domain:

H3:

The ability of a VA to provide answers to user questions is positively associated with perceptions of VA usefulness

Learning new things is a specific benefit that a VA can offer for the user. In consumer-related research, consumer learning has been measured as subjective knowledge about a domain (e.g. Li, Daugherty, and Biocca Citation2003) and in terms of actual knowledge as captured by a quiz (e.g. Poynor and Wood Citation2010). Here, in the present study, however, the focus is on perceived learning benefits; that is to say, the extent to which a user believes that his/her knowledge can increase as a result of an interacting with another agent (Froehle and Roth Citation2004). In the context of virtual agents, this aspect has been referred to as the extent to which an agent is believed to facilitate learning (Ryu and Baylor Citation2005). It is expected in the present study that VAs that can provide answers to questions would boost beliefs about learning benefits compared to when answers are not provided. The following, then, is hypothesized:

H4:

The ability of a VA to provide answers to user questions is positively associated with perceptions of learning benefits stemming from using the VA

2.3 Effects on overall evaluations

In the next step in a process in which judgments of a replier are formed, it is assumed that the outcomes covered by H1-H4 would be positively associated with the overall evaluation of the replier. In the present study, the overall evaluation variable is the perceived service quality (PSQ) with respect to the VA. The choice of this particular downstream variable was based on its important role as an overall evaluation variable in traditional service theories (e.g. Cronin and Taylor Citation1992; Hartline and Jones Citation1996). More recent applications of PSQ as an evaluation variable comprise technology-based services such as, for example, e-channels (Blut et al. Citation2015), service robots (Choi et al. Citation2020; Söderlund Citation2022), and AI-based services (Prentice, Dominique Lopes, and Wang Citation2020).

With respect to competence, a positive association between the perceived competence of a person and overall evaluations of the person is typical for human-to-human interaction contexts (Hartley et al. Citation2016; Wojciszke Citation2005). In a service encounter setting, it has also been reported that perceived service provider competence is positively associated with the customer’s positive emotions, negatively associated with his or her negative emotions (Price, Arnould, and Deibler Citation1995), and positively associated with intentions to try a service product (Min and Hu Citation2022). Similarly, customer beliefs in the capabilities of his/her interaction partner (i.e. other-efficacy) in a service context has been shown to be positively associated with perceived value (Wang Citation2018). Moreover, beliefs about employee competence typically have a positive influence on the overall evaluation of the employee (Söderlund and Berg Citation2020). In specific knowledge-related settings, such as when the transfer of knowledge is the core of an interaction (e.g. in education programs), lack of perceived competence of an interaction party is typically seen as dissatisfying (Chahal and Devi Citation2013; Voss, Gruber, and Reppel Citation2010). For example, and in terms of the ability to provide answers to questions, a professor who immediately answers a student’s question is seen as satisfying by students (Voss Citation2009); conversely, a professor who refuses to answer student questions, or cannot answer them, is seen as dissatisfying (Voss, Gruber, and Reppel Citation2010). With respect to studies of reactions to VAs, Verhagen et al. (Citation2014) report that VA expertise positively influenced social presence and personalization, and both these outcomes were positively associated with service encounter satisfaction. Similarly, VA competence was positively associated with the overall evaluation of the VA in Söderlund et al. (Citation2021). In task-oriented conversations with VAs, it has also been shown that the majority of users leave the conversation if the VA cannot give the desired answer right away (Akhtar, Neidhardt, and Werthner Citation2019), and leaving a conversation can be seen as an indication of dissatisfaction. Given this, then, it is expected in the present study that a VA’s perceived competence would be positively associated with the overall evaluation of the VA with respect to perceived service quality:

H5a:

Perceptions of VA competence are positively associated with PSQ

Openness to disclosing one’s limitations is one of several indicators of a person’s humility. And several authors have stressed that humility is a virtuous, positively charged characteristic (Exline and Geyer Citation2004; Hagá and Olson Citation2017; Nielsen, Marrone, and Slay Citation2010; Owens, Johnson, and Mitchell Citation2013). It has also been argued that disclosure of personal limitations has the potential to foster high-quality interpersonal relations (Owens, Johnson, and Mitchell Citation2013) and that humble people are likely to be seen as likeable (Exline and Geyer Citation2004). In addition, according to Skipper (Citation2021), we are likely to trust those who admit what they do not know; one main reason is that admitting this indicates a general aversion against making false assertions. Similarly, to be truthful is a common conversational norm, and admitting one’s knowledge gaps can signal truthfulness (Setlur and Tory Citation2022). In empirical terms, it has been shown that intellectual humility is negatively associated with neuroticism, dogmatism (Haggard et al. Citation2017), manipulativeness and social dominance (Wright et al. Citation2017), and positively associated with prosocial values such as empathy, altruism and benevolence (Krumrei-Mancuso Citation2017). This, then, suggests that a person who scores high on intellectual humility is likely to be liked – particularly when the person is providing service to others. Relatively few empirical studies of humility, however, have been made in a social perception context (i.e. examinations of participants’ views of a target person other than themselves). One exception is Huynh and Dicke-Bohmann (Citation2020), who found that patients’ perceptions of their clinicians’ humility were positively associated with both patient satisfaction and the extent to which patient felt trust in relation to their clinician. Similar results are reported by Hagá and Olson (Citation2017) in an everyday context and with respect to liking of the other person as a result of the person displaying intellectual humility. Taken together, then, and given anthropomorphism, it is expected that a VA’s perceived openness to disclosing knowledge gaps would be positively associated with perceived service quality:

H5b:

Perceptions of VA openness to disclosing its own knowledge limitations are positively associated with PSQ

Usefulness comprises beliefs about general benefits that a technology can offer, for example, convenience and time savings (Ghazali et al. Citation2020). Such benefits can been seen as the desirable consequences of using a product (Gutman Citation1982). They can also be seen as representing the main reason for consumers’ buying and usage behaviors (Botschen, Thelen, and Pieters Citation1999; Gutman Citation1982). Given that a positive perception in a pre-purchase phase of what quality level a product provides can determine buying and using the product, it is assumed that perceived usefulness of a VA would have a positive impact on PSQ. In empirical terms, a positive association between perceived usefulness and overall evaluations is a typical finding when human participants evaluate technologies, and this association has also materialized in several studies of chatbots (Rapp, Curti, and Boldi Citation2021). The same is expected here:

H5c:

Perceptions of VA usefulness are positively associated with PSQ

Finally, it is assumed that there would be a positive association between learning benefits provided by a service (i.e. beliefs about enhanced knowledge in a domain related to the service) and the overall evaluation of the service. One main reason is that enhanced knowledge can increase mastery (Alba and Williams Citation2013), which is typically a positively charged state of mind (White Citation1959). It is also likely that improved knowledge can result in a more stimulating and longer lasting consumption experience (Alba and Williams Citation2013). In addition, consumers derive greater enjoyment from an activity as their proficiency with it increases; feelings of insight provide particularly high increases in liking a product (Lakshmanan and Krishnan Citation2011). In empirical terms, Froehle and Roth (Citation2004) have reported a positive association between the extent to which an interaction in a commercial setting is seen as providing increased knowledge and overall evaluations of the interaction. Therefore, it is expected that a VA that is perceived as providing learning benefits for a user would be evaluated positively in terms of perceived service quality:

H5d:

Perceptions of learning benefits related to using a VA are positively associated with PSQ

3. Research method

3.1 Experimental design and participants

The hypotheses H1-H5 were tested with data from a between-subjects experiments in which a VA’s ability to answer user questions was manipulated (low, medium, high). The specific setting selected for the experiment was a VA programmed to be knowledgeable about running shoes, and it was designed to mirror what can be expected in the not-so-distant future when it comes to websites of retailers in the field of sporting goods. To be able to keep constant other aspects than a VA’s ability to answer questions in a conversation with a user, a script was made for a human-to-VA interaction. The script comprised a conversation with turn-taking in terms of an exchange of questions and answers between the two parties. In this conversation, the human asked eight running shoes-related questions to the VA. Three versions were made of the script in order to manipulate the level of the VA’s ability to answer questions. As a main means for the manipulation, it was assumed that the utterance ‘I do not know’ is a prototypical marker of an inability to supply information when it occurs in response turns (Tsui Citation1991).

In the low ability version, and for four of the human’s questions, the VA said ‘I do not know’ and nothing more before it was the human’s turn to speak again. In the medium ability version, and for the same four questions, the VA said ‘I do not know’ and continued to speak about related issues. When used in this way, it was assumed that ‘I do not know’ conceals an ability to answer questions by being used as a prompt to move the conversation forward (cf. Setlur and Tory Citation2022). In the high ability version, the VA never said ‘I do not know’ and instead proceeded by speaking about the same related issues as in the medium ability version.

These three script versions were enacted with a human user and a VA developed for the purpose of this study, their conversation was in voice mode, and the conversations were recorded on video. The resulting videos were used as stimuli for the participants in the study (see the Appendix for links to the videos). The VA was created by using a web-based service that allows users to design customizable speaking avatars with lip movement synchronized with their speech. This VA was given the name Alice, a female gender, the appearance of a human who is likely to be interested in sports, and a voice with a British accent. For the human user in the video (and for the participants), the VA appeared on the right side of a computer screen with the text ‘Your Virtual Running Guide’ on the left side (see ).

As mentioned above, the present study, as many other studies of humans’ reactions to VAs and other synthetic agents, has been influenced by an anthropomorphism assumption. That is to say, we humans tend to react to (humanlike) non-humans in ways that are similar to how we react to real humans (Epley et al. Citation2008). Therefore, it was viewed as informative to explicitly assess the extent to which the stimulus VA in the present study could be seen as humanlike. This was done in two ways.

First, a video with only the VA visible was submitted to FaceReader, a software developed to use videos with humans’ facial expressions as inputs to assess the intensity of a set of emotions. As a byproduct of this, FaceReader gives an assessment of the characteristics of the person whose emotions are gauged. For the VA in the present study, FaceReader concluded that its gender was female, that its age was in the 10–20 years range, and that its ethnicity was Caucasian. It also concluded that the VA’s happiness intensity (M = 0.15) was higher than the intensity for sad (M = 0.05), angry (M = 0.03) and scared (M = 0.03).

Second, a measure of perceived humanness (scored as 1 = low and 10 = high), and used by Söderlund and Oikarinen (Citation2021) in a study of bona fide VAs in the field, was distributed to the participants. The mean perceived humanness in the present sample was 5.23 (there were no significant differences between the three conditions), which is higher than the 4.79 mean in Söderlund and Oikarinen (Citation2021). Taken together, these observations indicate that the VA in the present study can indeed be seen as somewhat humanlike.

The participants were recruited from the Prolific online panel (n = 363, Mage = 42.94; 178 women, 182 men and 3 other, all were UK residents) and they were randomly allocated to watching one of the three video versions. Each video was followed by questionnaire items to capture the participants’ responses to the VA in the video.

3.2 Measures

All measures of the variables in the hypotheses were based on multi-item scales, and they were scored on a 10-point scale. Cronbach’s alpha (CA), composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) were used to assess the measurement properties. All item loadings were > .70 and a discriminant analysis with the heterotrait-monotrait approach indicated that no association was > .80.

The VA’s ability to answer questions was measured with the items ‘The virtual agent could answer all the questions from the human user’, ‘The virtual agent could provide information about everything that the human wanted to know’, and ‘The virtual agent was able to respond to all of the human’s questions’ (1 = do not agree at all, 10 = agree completely; CA = .91, CR = .92, AVE = .86). These items were developed for the purpose of conducting the present study.

Competence was measured with the adjective pairs ‘Incompetent-Competent’, ‘Did not know what it was talking about – Did know what it was talking about’, ‘Low knowledge about running shoes – High knowledge about running shoes’, and ‘Unprofessional – Professional’ (CA = .84, CR = .88, AVE = .67). Similar items have been used by Min and Hu (Citation2022).

Openness to admitting knowledge limitations was measured with ‘The virtual agent was open about its own knowledge gaps’, ‘The virtual agent had the ability to admit what it does not know’, ‘The virtual agent was willing to disclose its own lack of knowledge’, and ‘The virtual agent displayed awareness of its own knowledge gaps’ (1 = do not agree at all, 10 = agree completely; CA = .95, CR = .96, AVE = .90). The items were developed for the purpose of conducting this study, and they were based on the conceptual characteristics of the humility construct as discussed by, for example, Haggard et al. (Citation2017), Owens et al. (Citation2013) and Whitcomb et al. (Citation2017).

The measure of perceived usefulness comprised the items ‘A virtual agent of the type depicted in the video makes the life of humans more convenient when they need information’, ‘When humans lack information about something, virtual agents of the type depicted in the video make the life of humans less effortful’ and ‘When there is a need for information, using a virtual agent with capabilities of the type depicted in the video would be time-saving’ (1 = do not agree at all, 10 = agree completely; CA = .92, CR = .93, AVE = .87). Similar items were used in Söderlund (Citation2022). Somewhat similar items have been used for the assessment of a digital assistant by Chattaraman et al. (Citation2019).

Learning benefits were measured with the items ‘Using a virtual agent of the type depicted in the video would improve my knowledge about running shoes’, ‘Using a virtual agent of the type depicted in the video would increase my competence in evaluating running shoes’, and ‘Using a virtual agent of the type depicted in the video would make me learn more about running shoes’ (1 = do not agree at all, 10 = agree completely; CA = .94, CR = .95, AVE = .90). Similar items appear in the Ryu and Baylor (Citation2005) scale for assessing perceptions of the extent to which a pedagogical virtual agent facilitates learning.

Perceived service quality (PSQ) was measured with the question ‘What is your view of the service that the virtual agent provided?’ followed by the items ‘Low service quality – high service quality’, ‘Poor performance – Good performance’, and ‘It delivered below expectations – It delivered above expectations’ (CA = .94). This measure of perceived service quality, as an overall evaluation of a service, was used in a service robot study by Söderlund (Citation2022). Similar measures has been employed in human-to-human settings by Cronin and Taylor (Citation1992) and Hartline and Jones (Citation1996). To examine the validity of this measure (in the present setting, in which the main service of the agent comprised providing information), this item was used: ‘Do you think it would be bad or good for the human in the video to believe what the virtual agent had to say about running shoes?’ (1 = bad, 10 = good). The correlation between PSQ and this item was positive and significant (r = .63, p < .01), which indicates that the PSQ measure is measuring what it is supposed to measure.

It should be noted that the present study employed a Wizard of Oz approach (cf. Broadbent Citation2017). This means that the virtual agent was depicted in the videos as having more advanced capabilities than most existing virtual agent have when they are used for customer contacts by retailers. In other words, the stimulus virtual agent was not supposed to mirror any particular virtual agent in the world outside the experiment; it was supposed to mirror what is assumed to have the potential to exist in the not-so-distant future. This aspect of the stimulus VA calls for an assessment of its perceived realism, and it was made by asking the participants to respond to the following item: ‘Virtual agents with capabilities of the type displayed in the video…’ followed by the response alternatives ‘ … will never exist’ (chosen by 3 participant), ‘ … exist already’ (chosen by 235 participants), and ‘ … will exist in the future’ (chosen by 125 participants). This indicates that the virtual agent appeared as realistic for the majority of the participants.

4. Analysis and results

4.1 Manipulation check

The participants’ perceptions of the VA’s ability to answer to the human user’s questions was employed as a manipulation check. These perceptions reached the lowest level in the low ability condition (M = 4.49) compared to the medium ability condition (M = 5.88) and the high ability condition (M = 7.02). The omnibus test in a one-way ANOVA indicated that all means were not equal (F = 36.36, p < .01) and post hoc tests with Scheffe’s method showed that all pairwise differences were significant (all p < .01). The manipulation thus worked as intended. It should be noted that the utterance ‘I do not know’ can have other functions than indicating a replier’s ability to answer questions – for example, indicating low commitment to what follows, to avoid impoliteness, and to reject requests (Baumgarten and House Citation2010; Beach and Metzger Citation1997; Tsui Citation1991; Weatherall Citation2011). The manipulation check results, however, suggest that the presence or absence of ‘I do not know’ indeed had an impact on perceptions of the VAs ability to answer.

4.2 Testing the hypotheses

A structural equation modeling approach with SmartPLS 3.0 was used to test H1-H5 within the frame of the same analysis. In the proposed model (see ), the participants’ view of the VA’s ability to answer the human user’s questions was the independent variable. It was modelled as influencing perceptions of the VA’s competence (H1), openness to disclose knowledge limitations (H2), usefulness (H3), and learning beliefs (H4). Each of these variables was also modelled as influencing PSQ (H5a-H5d). In addition, the proposed model comprised a direct association between the VA’s ability to answer user questions and PSQ (to facilitate a mediation assessment; more about this below). The explained variance with this model (i.e. R2) for PSQ was .68. The path coefficients and their effect sizes are reported in .

Table 1. Path coefficients for the H1-H5 associations.

The results in indicate that all hypotheses except H2 (about the influence of answering ability on openness to disclose knowledge gaps) were supported. The Answering ability – Openness association was in the hypothesized (and negative) direction, but it was not strong enough to receive support (b = −0.08, p = .17). Openness, however, did produce the hypothesized positive association with PSQ (i.e. H5b), which is consonant with the positive association between perceived clinician humility and patient satisfaction reported by Huynh and Dicke-Bohmann (Citation2020).

Taken together, H1-H5 imply that the influence of the VA’s ability to answer questions on PSQ is mediated. To assess this aspect formally, a mediation analysis was conducted along the lines suggested by Sarstaed et al. (Citation2020). This means that mediation was assessed within the frame of the proposed model by an examination of the significance of indirect paths while the possible direct effect of the VA’s ability to answer questions on PSQ was controlled for (by a direct link in the proposed model between answering ability and PSQ). This analysis indicated significant indirect influence of the VA’s answering ability on PSQ via competence (b = 0.12, p < .01), usefulness (b = 0.13, p < .01) and learning benefits (b = 0.10, p < .01). The indirect influence via openness, however, was not significant (b = −0.009, p = .20). The direct association between answering ability and PSQ was significant, too (b = 0.20, f2 = .09, p < .01), which indicates that complementary mediation was at hand (Zhao, Lynch, and Chen Citation2010).

The results thus indicate that the VA’s ability to answer questions boosted PSQ. This can also be seen in a mean comparison between the three experimental conditions; the low ability condition produced a lower level of PSQ (M = 6.22, SD = 1.97) than the medium ability condition (M = 6.54, SD = 2.20) and the high ability condition (M = 6.90, SD = 1.79). The omnibus test in a one-way ANOVA indicated that all three means were not equal (F = 3.62, p < .05). Post hoc tests (with Scheffe’s method) showed that only the pairwise difference between the low ability condition and the high ability condition was significant (p < .05).

5. Discussion

5.1 Contributions

Thoughts about knowledge limits were shared already by Socrates, in Platon’s Charmides, when he suggested that awareness about what we know and do not know should be seen as wisdom. Socrates, however, expressed uncertainty about the extent to which this awareness would make us act well or make us happy. The present study does not answer this, but it does provide evidence about the effects of perceptions of others when those others vary in their ability to answer questions. In the present study, the ‘other’ was a (humanlike) non-human agent, and thereby the present study contributes to research on reactions to such agents by examining the agent’s ability to answer a human user’s questions – a hitherto understudied aspect of VA behavior. This means – in relation to existing research – that the present study broadens the nomological net of several variables that were included in the study.

Given that the display of an ability to answer questions can be seen as an indicator of a VA’s knowledge, existing research shows that perceptions of the knowledge of non-human agents are likely to be influenced by the social attractiveness of the agent (Chen and Park Citation2021) and by the participant’s gender (Liew, Tan, and Jayothisa Citation2013); that such perceptions can affect trust (Matsui and Yamada (Citation2019); and that they can mediate the influence of the agent’s role as a specialist/generalist on purchase intentions (Tan and Liew Citation2020). The present study contributes to the nomological net of perceptions of others’ knowledge, then, with the finding that a VA admitting that it does not know something results in lower evaluations of the VA compared to when the VA avoids admitting this. Oscar Wilde once stated that ignorance is like a delicate exotic fruit (Smithson Citation1993), thus implying that a low level of knowing can have a positive charge; the results in the present study, however, indicate the opposite with respect to the situation in which others’ level of knowing is perceived to be low.

Moreover, the finding in the present study that a VA’s ability to answer questions has a positive influence on its perceived competence contributes to previous research indicating that the competence of a non-human agent is a function of its perceived happiness (Söderlund, Oikarinen, and Tan Citation2021), agency (Lee et al. Citation2019), and usage of gestures (Bergmann, Eyssel, and Kopp Citation2012). It may be noted that – in conceptual terms – a negative association between the ability to answer questions and competence is possible in a social perception setting. That is to say, if a person never fails to answer any questions, it can indicate that this person is unaware of his/her incompetence. And, according to Dunning et al. (Citation2003), those who are most likely to have this unawareness are the low performers (here: those who indeed know little). If a perceiver is thinking along those lines when he or she faced with an agent that never admits a low level of answering questions, then, one would expect that it would result in a negative evaluation of the agent. Conversely, if I know that I do not know something (and admit this when I am asked about it), I display a high level of meta-ignorance (i.e. I know that I do not know; cf. Smithson Citation1993), which may represent a kind of advanced knowledge mirroring high as opposed to low competence. Therefore, one would think that my display of a low ability to answer would be rewarded with a high evaluation of me. Such response patterns, however, did not materialize in the present study.

If openness to disclosing one’s own personal knowledge limitations is seen as a facet of humility, the present study also contributes to the field of research on intellectual humility. In this growing field, the typical study is based on the participant’s self-reported intellectual humility and it assesses how humility is related to other personal characteristics such as dogmatism and narcissism (cf. the review by Porter et al. Citation2021). In contrast, the present study examined humility-related behavior in a social perception setting. Thus, the participants in the present study were asked about a target agent, not about themselves. So far, social perceptions of humility in a human-to-human context has been subject to only a limited number of studies (such as Hagá and Olson Citation2017). In the present study, it turned out that the perceived openness to admit one’s knowledge limitations was positively associated with PSQ in the case of a VA, which mirrors empirical results in a human-to-human setting (Hagá and Olson Citation2017). This part of the results, then, seems to indicate that the general response pattern to humanlike non-human agents (i.e. to react to them similarly to how we react to real humans) appears to be at hand also in terms of humility-related attributes of an agent.

Similarly, the present study contributes to research on learning-related variables by showing that perceived learning benefits mediate the impact of a VA’s ability to answer questions on perceived service quality. Previous studies within the field of e-learning with the aid of various non-human agents have examined, for example, if facial expressions, the instruction mode, and the verbal expressiveness of a virtual agent used for pedagogical purposes facilitate learning (Baylor and Kim Citation2009; Veletsianos Citation2009), and the present study’s focus on the ability of an agent to answer questions expands the nomological net of such research.

It should again be underlined that many existing studies of humans’ reactions to non-human agents (including the present study) are based on an anthropomorphism assumption. When such studies comprise agent characteristics and behaviors that are shared with humans (e.g. having a gender, display of happiness, and politeness), they can indeed capitalize on theory and findings from a human-to-human setting. The ability to answer questions in a human-to-human setting, however, has been subject to relatively few empirical studies. Given that a by-product of examining how humans react to (humanlike) non-human agents is that we may learn more about how humans react to other humans (e.g. Broadbent Citation2017), the present study can also be seen as taking some steps in the direction of a richer understanding of the ability to answer questions in a human-to-human setting. That is to say, if this ability of a humanlike non-human enhances PSQ, a human frontline employee’s perceived ability to answer questions in a service situation may enhance PSQ, too. If so, for example, humility in terms of acknowledging ones’ knowledge limits may not be a desirable characteristic of a person who is representing a company in interactions with its customers.

5.2 Implications for decision makers

The main finding in the present study was that a VA’s display of an ability to provide answers to user questions boosts PSQ. This implies that designers of VAs should deliberately program VAs so that they avoid an explicit display of a low ability to answer users’ questions (e.g. by avoiding saying ‘I do not know’). As already indicated above, ChatGPT, which is likely to become a point of reference for many VAs used for customer contacts in retailing, is frequently displaying this type avoidance when it is producing nonsensical information that looks plausible (Taecharungroj Citation2023).

Although there are not many empirical studies of how we humans react to other humans who claim that they do not know the answer to a question, the implication above seems to be in tune with various social media personalities who give advice to managers and employees about what to do and not do in a work life context. That is to say, many of them strongly recommend that ‘I do not know’ should be avoided, because it can, it is argued, make one come across as inexperienced and unprofessional. Instead, many alternative options are recommended, such as ‘Here is what I can tell you … ’, ‘I’ll find out’, ‘I have the same question’, and ‘My best guess is … ’. Thus there are several specific options to consider for the programmer who wants to avoid a VA to signal a low ability to answer questions. This programmer, however, should be mindful of the possibility that a user of a VA may be such a user at least partly because he or she can get answers in corporate lingo-sounding language elsewhere (i.e. from humans engaging in impression management).

Another issue also calls for caution: if a VA is programmed to never display a low level of an ability to answer questions (e.g. by never saying ‘I do not know’), it may interfere with the ability of the VA to learn. That is to say, using utterances such as ‘I do not know’ can signal to the VA itself that there is a need for additional learning, while never using such utterances may distort such signals. In other words, avoiding an explicit display of a low ability to answer questions may mask lack of knowledge – and to lack relevant knowledge without realizing it can have unwelcome (and even disastrous) consequences (Hansson, Buratti, and Allwood Citation2017). Using ChatGPT as an example again, it does not always pretend to know when it does not know; it frequently admits its knowledge gaps, too (Taecharungroj Citation2023). For example, when the author of the present study asked ChatGPT-4 about today’s opening hours for Sainsbury’s in London, this is what it answered: I’m sorry, but I don’t have access to real-time data, including current store hours for specific locations like Sainsbury’s in London.”

A related issue is that progress in artificial intelligence can make VAs experts in various domains. If this expertise is humanlike, however, it may produce a failure to recognize what one does not know, because (human) experts are likely to underestimate their own ignorance (Hansson, Buratti, and Allwood Citation2017). And if avoiding utterances of the type ‘I do not know’ boosts a VA’s view of its own expertise, one may again expect that the motivation to learn new things is mitigated.

5.3 Limitations and directions for further research

In the present study, the stimulus VA had a (synthetic) voice as opposed to VAs that communicate with written text. Previous research, however, suggests that spoken words are more effortful to process than written text, particularly when produced by synthetic speech (Lee Citation2008). If it is more cognitively taxing to receive information by a synthetic voice compared to a written text, the present study may have made individual utterances such as ‘I do not know’ less salient and thus less causally potent compared to when they are produced in the form of text. Further studies are therefore needed to examine if similar results would be obtained when a VA communicates with written text. In addition, the VA was given a female gender. This may have reduced the negative impact of answering ‘I do not know’ in relation to a VA with a male gender, because in human-to-human settings people seem to have preferences for intellectually humble women and intellectually arrogant men (Hagá and Olson Citation2017). Thus, further research is needed to examine the extent to which the results in the present study would replicate with a male-gendered VA.

Moreover, the VA’s ability to answer questions was manipulated by using the utterance ‘I do not know’, which represents a common phrase in human-to-human conversations to express an inability to provide requested information (Tsui Citation1991). However, a low ability to answer a question can be displayed in many other ways, for example, with utterances such as ‘nobody really knows this’ and ‘this is hard to say, because … ’. Thus, an agent can reduce the emphasis on ‘I’ and motivate its inability to answer by referring to gaps in the overall body of knowledge in a domain. Presumably, this can signal competence and may therefore have less negative effects than responses comprising ‘I’. Indeed, if a domain comprises material that can be subject to scientific research, one may view serious science as something that acknowledges the limits of existing knowledge. In any event, the possibility of different effects of different ways of communicating one’s knowledge limitations depending on the domain needs to be examined in further research. Researchers who study virtual agents’ answers to questions should also be mindful about the existence of another type of response, namely an explicit refusal to answer (e.g. ‘I do not want to answer this’ and ‘I am not going to answer this’). This type of non-answer has been examined in politicians’ responses to interview questions (Ekström Citation2009). Its valence appear to be ambiguous; it can signal a transgression of norms as well as skillfulness (Ekström, Citation2009). One may assume that there are situations in which such responses by a virtual agent can be positively charged, such as when the agent is concerned with the asker’s well-being and does not want to deliver answers based on too little or contradictory evidence. As an extension, also based on analyses of politicians in interview situations, there are several other ways in which someone can provide a non-answer to a question, such as ignoring the question, questioning the question, and attacking the questioner (Bull and Mayer Citation1993). Thus, ‘I do not know’ is one of many non-answers, and further research is needed to assess how the full gamut of non-answers affect evaluations of those who use them.

The present study showed that three variables (competence, usefulness, and learning benefits) mediated the influence of perceived VA ability to answer questions on PSQ. However, the direct effect was significant, too. This suggests that also other mediating variables are likely to exist. One possibility that needs to be examined in further studies is the functions of the utterance ‘I do not know’. In the present study, it was assumed that its presence or absence indicates a replier’s ability to answer questions, and the manipulation check suggests that this was indeed so. However, given that ‘I do not know’ can indicate other things too, such as low commitment to what follows and a willingness to avoid impoliteness (Tsui Citation1991; Weatherhall, 2011), which appear to have a valenced charge in a social perception setting, more research is needed to capture also other possible interpretations of ‘I do not know’ than an ability to answer questions. Usage of ‘I’, for example, may signal that an agent has self-identification and self-awareness abilities (i.e. it can distinguish itself from others), which is often seen as a prerequisite for having a mind. And perceptions of a non-human agent as having a mind can boost evaluations of the agent (Söderlund and Oikarinen Citation2021).

As for moderating variables, the context in which a low ability to answer questions is displayed may affect its impact on other variables. However, this was not assessed in the present study. One such contextual variable is the level of expertise displayed by a VA when it comes to things that it does know (and can answer questions about). More specifically, one would assume that an agent that displays a high overall level of expertise and displays (here and there in a conversation) that there are limits to this expertise, would produce less negative responses compared to when such answers are delivered by an agent that displays a low overall level of expertise. That is to say, if admitting that one has knowledge gaps is a facet not only of humility, but also of wisdom in the Socratic sense, it is possible that an agent that admits what it does not know can boost perceived agent competence when the agent has additional means to display that it has indeed high knowledge. It should also be observed that the setting for the VA in the present study was communication about one particular product category (i.e. running shoes), a domain for which there is indeed ambiguity when it comes to empirical evidence (such as how long you should keep a pair if running shoes). This means that a display of a low level of ability to answer questions may be less influential compared to domains in which ambiguity is lower. For example, if the domain is ‘the running shoes available from retailer X’, one would expect that an inability to answer questions such as ‘do you have the shoes XYZ in size 10.5?’ would produce stronger negative reactions. Thus further research is needed also to examine if the results in the present study would generalize to domains with other levels of ambiguity.

Finally, the present study can be seen as a typical contemporary experiment in the sense that it comprised an assessment of effects immediately after (one) exposure to stimuli. Thus the present study does not address what happens after repeated exposure to VA behaviors in conversations. One possibility, however, is that prolonged and repeated exposure to non-human (but humanlike) agents displaying one particular behavior could influence humans to behave in the same way (Cappuccio et al. Citation2021). This is basically the same assumption as when acknowledging that firms’ activities – in the aggregate – can produce unintended societal consequences. Examples of such (alleged) consequences, in the domain of firms’ advertising activities, are that advertising can reinforce materialism, cynicism, irrationality, selfishness, anxiety, social competitiveness, and sexual preoccupation (Pollay Citation1986). In the light of such influence, one would be tempted to believe this: if retailers and others who instruct their VAs to never display a low level of knowledge, it can result in an attenuated level of intellectual humility in society. Conversely, given that a virtuous non-human agent can contribute to users’ moral flourishing by continuously repeating certain behaviors (Cappuccio et al. Citation2021), explicitly instructing VAs to indeed admit what they do not know may enhance human-to-human intellectual humility. And as noted by Wright et al. (Citation2017), even a little more humility in the world would go a long way to make the world a morally better place.

Biographical note

Magnus Söderlund is Professor of Marketing and Head of the Center for Consumer Marketing at Stockholm School of Economics, Sweden. His main research current interest is how consumers react to various forms of marketing and service activities involving non-human agents such as virtual agents and robots.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Magnus Söderlund

Magnus Söderlund is a Professor of Marketing and at the Stockholm School of Economics and a Senior Fellow at the Hanken School of Economics. His main research interest is in how consumers react to various forms of marketing and service activities involving non-human agents such as virtual agents and robots.

References

- Akhtar, M., J. Neidhardt, and H. Werthner 2019. The Potential of Chatbots: Analysis of Chatbot Conversations. In: 2019 IEEE 21st Conference on Business Informatics (CBI), Moscow, 1, 397–404.

- Alba, J. W., and E. F. Williams. 2013. “Pleasure Principles: A Review of Research on Hedonic Consumption.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 23 (1): 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2012.07.003.

- Barasch, A., E. E. Levine, and M. E. Schweitzer. 2016. “Bliss is Ignorance: How the Magnitude of Expressed Happiness Influences Perceived naiveté and Interpersonal Exploitation.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 137 (November): 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2016.05.006.

- Baumgarten, N., and J. House. 2010. “I Think and I Don’t Know in English as Lingua Franca and Native English Discourse.” Journal of Pragmatics 42 (5): 1184–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.09.018.

- Baylor, A. L., and S. Kim. 2009. “Designing Nonverbal Communication for Pedagogical Agents: When Less is More.” Computers in Human Behavior 25 (2): 450–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.10.008.

- Beach, W. A., and T. R. Metzger. 1997. “Claiming Insufficient Knowledge.” Human Communication Research 23 (4): 562–588. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1997.tb00410.x.

- Bergmann, K., F. Eyssel, and S. Kopp2012. A Second Chance to Make a First Impression? How Appearance and Nonverbal Behavior Affect Perceived Warmth and Competence of Virtual Agents Over Time. In: International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Springer, Berlin, 126–138.

- Blut, M., N. Chowdhry, V. Mittal, and C. Brock. 2015. “E-Service Quality: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Retailing 91 (4): 679–700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2015.05.004.

- Botschen, G., E. M. Thelen, and R. Pieters. 1999. “Using Means‐End Structures for Benefit Segmentation: An Application to Services.” European Journal of Marketing 33 (1/2): 38–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004491.

- Broadbent, E. 2017. “Interactions with Robots: The Truths We Reveal About Ourselves.” Annual Review of Psychology 68 (1): 627–652. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010416-043958.

- Bromuri, S., A. P. Henkel, D. Iren, and V. Urovi. 2020. “Using AI to Predict Service Agent Stress from Emotion Patterns in Service Interactions.” Journal of Service Management 32 (4): 581–611. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-06-2019-0163.

- Bull, P., and K. Mayer. 1993. “How Not to Answer Questions in Political Interviews.” Political Psychology 14 (4): 651–666. https://doi.org/10.2307/3791379.

- Cappuccio, M. L., E. B. Sandoval, O. Mubin, M. Obaid, and M. Velonaki. 2021. “Can Robots Make Us Better Humans?” International Journal of Social Robotics 13 (1): 7–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-020-00700-6.

- Chahal, H., and P. Devi. 2013. “Identifying Satisfied/Dissatisfied Service Encounters in Higher Education.” Quality Assurance in Education 21 (2): 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684881311310728.

- Chattaraman, V., W. S. Kwon, J. E. Gilbert, and K. Ross. 2019. “Should AI-Based, Conversational Digital Assistants Employ Social-Or Task-Oriented Interaction Style? A Task-Competency and Reciprocity Perspective for Older Adults.” Computers in Human Behavior 90 (January): 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.048.

- Chaves, A. P., and M. A. Gerosa. 2021. “How Should My Chatbot Interact? A Survey on Social Characteristics in Human–Chatbot Interaction Design.” International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 37 (8): 729–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1841438.

- Chen, Q. Q., and H. J. Park. 2021. “How Anthropomorphism Affects Trust in Intelligent Personal Assistants.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 121 (12): 2722–2732. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-12-2020-0761.

- Choi, Y., M. Choi, M. Oh, and S. Kim. 2020. “Service Robots in Hotels: Understanding the Service Quality Perceptions of Human-Robot Interaction.” Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 29 (6): 613–635. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1703871.

- Crolic, C., F. Thomaz, R. Hadi, and A. T. Stephen. 2022. “Blame the Bot: Anthropomorphism and Anger in Customer–Chatbot Interactions.” Journal of Marketing 86 (1): 132–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429211045687.

- Cronin, J. J., Jr, and S. A. Taylor. 1992. “Measuring Service Quality: A Reexamination and Extension.” Journal of Marketing 56 (3): 55–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600304.

- Cuddy, A. J., P. Glick, and A. Beninger. 2011. “The Dynamics of Warmth and Competence Judgments, and Their Outcomes in Organizations.” Research in Organizational Behavior 31:73–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2011.10.004.

- Davis, F. D. 1993. “User Acceptance of Information Technology: System Characteristics, User Perceptions and Behavioral Impacts.” International Journal of Man-Machine Studies 38 (3): 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1006/imms.1993.1022.

- Dunning, D., K. Johnson, J. Ehrlinger, and J. Kruger. 2003. “Why People Fail to Recognize Their Own Incompetence.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 12 (3): 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01235.

- Ekström, M. 2009. “Announced Refusal to Answer: A Study of Norms and Accountability in Broadcast Political Interviews.” Discourse Studies 11 (6): 681–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445609347232.

- Epley, N. 2018. “A Mind Like Mine: The Exceptionally Ordinary Underpinnings of Anthropomorphism.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 3 (4): 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1086/699516.

- Epley, N., A. Waytz, S. Akalis, and J. T. Cacioppo. 2008. “When We Need a Human: Motivational Determinants of Anthropomorphism.” Social Cognition 26 (2): 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2008.26.2.143.

- Exline, J. J., and A. L. Geyer. 2004. “Perceptions of Humility: A Preliminary Study.” Self and Identity 3 (2): 95–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500342000077.

- Fiske, S. T., A. J. Cuddy, and P. Glick. 2007. “Universal Dimensions of Social Cognition: Warmth and Competence.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11 (2): 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005.

- Froehle, C. M., and A. V. Roth. 2004. “New Measurement Scales for Evaluating Perceptions of the Technology-Mediated Customer Service Experience.” Journal of Operations Management 22 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2003.12.004.

- Ghazali, A. S., J. Ham, E. Barakova, and P. Markopoulos. 2020. “Persuasive Robots Acceptance Model (PRAM): Roles of Social Responses within the Acceptance Model of Persuasive Robots.” International Journal of Social Robotics 12 (5): 1075–1092. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12369-019-00611-1.

- Gnewuch, U., S. Morana, and A. Maedche 2017. Towards Designing Cooperative and Social Conversational Agents for Customer Service, Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS), South Korea, South Korea, 1–13.

- Gutman, J. 1982. “A Means-End Chain Model Based on Consumer Categorization Processes.” Journal of Marketing 46 (2): 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298204600207.

- Hagá, S., and K. R. Olson. 2017. “‘If I Only Had a Little Humility, I Would Be perfect’: Children’s and adults’ Perceptions of Intellectually Arrogant, Humble, and Diffident People.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 12 (1): 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1167943.

- Haggard, M., W. C. Rowatt, J. C. Leman, B. Meagher, C. Moore, T. Fergus, D. Whitcomb, H. Battaly, J. Baehr, and D. Howard-Snyder. 2017. “Finding Middle Ground Between Intellectual Arrogance and Intellectual Servility: Development and Assessment of the Limitations-Owning Intellectual Humility Scale.” Personality and Individual Differences 124 (April): 184–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.014.

- Hansson, I., S. Buratti, and C. M. Allwood. 2017. “Experts’ and novices’ Perception of Ignorance and Knowledge in Different Research Disciplines and Its Relation to Belief in Certainty of Knowledge.” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (March): Article 377. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00377.

- Hartley, A. G., R. M. Furr, E. G. Helzer, E. Jayawickreme, K. R. Velasquez, and W. Fleeson. 2016. “Morality’s Centrality to Liking, Respecting, and Understanding Others.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 7 (7): 648–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550616655359.

- Hartline, M. D., and K. C. Jones. 1996. “Employee Performance Cues in a Hotel Service Environment: Influence on Perceived Service Quality, Value, and Word-Of-Mouth Intentions.” Journal of Business Research 35 (3): 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(95)00126-3.

- Hu, Y. 2021. “An Improvement or a Gimmick? The Importance of User Perceived Values, Previous Experience, and Industry Context in Human–Robot Service Interaction.” Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 21 (September). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2021.100645.

- Huynh, H. P., and A. Dicke-Bohmann. 2020. “Humble Doctors, Healthy Patients? Exploring the Relationships Between Clinician Humility and Patient Satisfaction, Trust, and Health Status.” Patient Education and Counseling 103 (1): 173–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.07.022.

- Köhler, C. F., A. J. Rohm, K. de Ruyter, and M. Wetzels. 2011. “Return on Interactivity: The Impact of Online Agents on Newcomer Adjustment.” Journal of Marketing 75 (2): 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.75.2.93.

- Krumrei-Mancuso, E. J. 2017. “Intellectual Humility and Prosocial Values: Direct and Mediated Effects.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 12 (1): 13–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1167938.

- Lakshmanan, A., and H. S. Krishnan. 2011. “The Aha! Experience: Insight and Discontinuous Learning in Product Usage.” Journal of Marketing 75 (6), November: 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.10.0348.

- Lee, E. J. 2008. “Flattery May Get Computers Somewhere, Sometimes: The Moderating Role of Output Modality, Computer Gender, and User Gender.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 66 (11): 789–800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2008.07.009.

- Lee, M., G. Lucas, J. Mell, E. Johnson, and J. Gratch 2019. What’s on Your Virtual Mind? Mind Perception in Human-Agent Negotiations. In: Proceedings of the 19th ACM International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Paris, France, 38–45.

- Li, H., T. Daugherty, and F. Biocca. 2003. “The Role of Virtual Experience in Consumer Learning.” Journal of Consumer Psychology 13 (4): 395–407. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1304_07.

- Liew, T. W., S. M. Tan, and C. Jayothisa. 2013. “The Effects of Peer-Like and Expert-Like Pedagogical Agents on learners’ Agent Perceptions, Task-Related Attitudes, and Learning Achievement.” Journal of Educational Technology & Society 16 (4): 275–286.

- Littlepage, G. E., G. W. Schmidt, E. W. Whisler, and A. G. Frost. 1995. “An Input-Process-Output Analysis of Influence and Performance in Problem-Solving Groups.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69 (5): 877–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.877.

- Longoni, C., and L. Cian. 2022. “Artificial Intelligence in Utilitarian Vs. Hedonic Contexts: The ‘Word-Of-machine’ Effect.” Journal of Marketing 86 (1): 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022242920957347.

- Matsui, T., and S. Yamada. 2019. “Designing Trustworthy Product Recommendation Virtual Agents Operating Positive Emotion and Having Copious Amount of Knowledge.” Frontiers in Psychology 10 (April). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00675.

- Min, H. K., and Y. Hu. 2022. “Revisiting the Effects of Smile Intensity on Judgments of Warmth and Competence: The Role of Industry Context.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 102 (April): 103152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103152.

- Nielsen, R., J. A. Marrone, and H. S. Slay. 2010. “A New Look at Humility: Exploring the Humility Concept and Its Role in Socialized Charismatic Leadership.” Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies 17 (1): 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051809350892.

- Owens, B. P., M. D. Johnson, and T. R. Mitchell. 2013. “Expressed Humility in Organizations: Implications for Performance, Teams, and Leadership.” Organization Science 24 (5): 1517–1538. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1120.0795.

- Pollay, R. W. 1986. “The Distorted Mirror: Reflections on the Unintended Consequences of Advertising.” Journal of Marketing 50 (2): 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298605000202.

- Porter, T., C. R. Baldwin, M. T. Warren, E. D. Murray, K. Cotton Bronk, M. J. Forgeard, N. E. Snow, and E. Jayawickreme. 2021. “Clarifying the Content of Intellectual Humility: A Systematic Review and Integrative Framework.” Journal of Personality Assessment 104 (5): 573–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2021.1975725.

- Poynor, C., and S. Wood. 2010. “Smart Subcategories: How Assortment Formats Influence Consumer Learning and Satisfaction.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (1): 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1086/649906.

- Prentice, C., S. Dominique Lopes, and X. Wang. 2020. “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence and Employee Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty.” Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 29 (7): 739–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1722304.

- Price, L. L., E. J. Arnould, and S. L. Deibler. 1995. “Consumers’ Emotional Responses to Service Encounters: The Influence of the Service Provider.” International Journal of Service Industry Management 6 (3): 34–63. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239510091330.

- Rapp, A., L. Curti, and A. Boldi. 2021. “The Human Side of Human-Chatbot Interaction: A Systematic Literature Review of ten Years of Research on Text-Based Chatbots.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 151 (July): 102630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2021.102630.

- Reeves, B., and C. Nass. 1996. The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press.

- Ryu, J., and A. L. Baylor. 2005. “The Psychometric Structure of Pedagogical Agent Persona.” Technology, Instruction, Cognition and Learning 2 (4): 291–314.

- Sarstedt, M., J. F. Hair Jr, C. Nitzl, C. M. Ringle, and M. C. Howard. 2020. “Beyond a Tandem Analysis of SEM and PROCESS: Use of PLS-SEM for Mediation Analyses!” International Journal of Market Research 62 (3): 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470785320915686.

- Setlur, V., and M. Tory 2022. How Do You Converse with an Analytical Chatbot? Revisiting Gricean Maxims for Designing Analytical Conversational Behavior. In: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, April, 1–17.

- Skipper, M. 2021. “The Humility Heuristic, Or: People Worth Trusting Admit to What They Don’t Know.” Social Epistemology 35 (3): 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2020.1809744.

- Smithson, M. 1993. “Ignorance and Science: Dilemmas, Perspectives, and Prospects.” Knowledge 15 (2): 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/107554709301500202.

- Söderlund, M. 2022. “Service Robots with (Perceived) Theory of Mind: An Examination of humans’ Reactions.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 67 (July). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102999.

- Söderlund, M., and H. Berg. 2020. “Employee Emotional Displays in the Extended Service Encounter: A Happiness-Based Examination of the Impact of Employees Depicted in Service Advertising.” Journal of Service Management 31 (1): 115–136. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-06-2019-0208.

- Söderlund, M., and E. L. Oikarinen. 2021. “Service Encounters with Virtual Agents: An Examination of Perceived Humanness as a Source of Customer Satisfaction.” European Journal of Marketing 55 (13): 94–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-09-2019-0748.

- Söderlund, M., E. L. Oikarinen, and T. M. Tan. 2021. “The Happy Virtual Agent and Its Impact on the Human Customer in the Service Encounter.” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 59 (March): 102401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102401.

- Suich Bass, A. 2018, GrAit Expectations, Special report, The Economist, March 31st.

- Taecharungroj, V. 2023. ““What Can ChatGpt do?” Analyzing Early Reactions to the Innovative AI Chatbot on Twitter.” Big Data and Cognitive Computing 7 (1): 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc7010035.

- Tan, S. M., and T. W. Liew. 2020. “Designing Embodied Virtual Agents as Product Specialists in a Multi-Product Category E-Commerce: The Roles of Source Credibility and Social Presence.” International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 36 (12): 1136–1149. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2020.1722399.

- Treem, J. W. 2012. “Communicating Expertise: Knowledge Performances in Professional-Service Firms.” Communication Monographs 79 (1): 23–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2011.646487.

- Tsui, A. B. 1991. “The Pragmatic Functions of I Don’t Know.” Text-Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of Discourse 11 (4): 607–622. https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1991.11.4.607.

- Veletsianos, G. 2009. “The Impact and Implications of Virtual Character Expressiveness on Learning and Agent–Learner Interactions.” Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 25 (4): 345–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00317.x.

- Verhagen, T., J. Van Nes, F. Feldberg, and W. Van Dolen. 2014. “Virtual Customer Service Agents: Using Social Presence and Personalization to Shape Online Service Encounters.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 19 (3): 529–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12066.

- Voss, R. 2009. “Studying Critical Classroom Encounters: The Experiences of Students in German College Education.” Quality Assurance in Education 17 (2): 156–173. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880910951372.

- Voss, R., T. Gruber, and A. Reppel. 2010. “Which Classroom Service Encounters Make Students Happy or Unhappy? Insights from an Online CIT Study.” International Journal of Educational Management 24 (7): 615–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513541011080002.

- Wang, C. Y. 2018. “Customer Participation and the Roles of Self-Efficacy and Adviser-Efficacy.” International Journal of Bank Marketing 37 (1): 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJBM-10-2017-0220.

- Weatherall, A. 2011. “I Don’t Know as a Prepositioned Epistemic Hedge.” Research on Language & Social Interaction 44 (4): 317–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2011.619310.

- Whitcomb, D., H. Battaly, J. Baehr, and D. Howard-Snyder. 2017. “Intellectual Humility: Owning Our Limitations.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 94 (3): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpr.12228.

- White, R. W. 1959. “Motivation Reconsidered: The Concept of Competence.” Psychological Review 66 (5): 297–333. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040934.

- Wojciszke, B. 2005. “Morality and Competence in Person-And Self-Perception.” European Review of Social Psychology 16 (1): 155–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280500229619.

- Wright, J. C., T. Nadelhoffer, T. Perini, A. Langville, M. Echols, and K. Venezia. 2017. “The Psychological Significance of Humility.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 12 (1): 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1167940.

- Zhao, X., J. G. Lynch Jr, and Q. Chen. 2010. “Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths About Mediation Analysis.” Journal of Consumer Research 37 (2): 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257.

Instructions to the participants:

In this study, you will be shown a video depicting a person who has questions about running shoes. The person had a chance to ask them to a virtual agent powered by artificial intelligence – an agent that can provide help for runners. After the video, there will be some questions for you about what happened. The study is a part of a research project examining how we humans react to synthetic agents.

Links to the video stimuli:

Low ability to answer: https://vimeo.com/706216666/7a8261241f

Medium ability to answer: https://vimeo.com/706219004/38f9f5a04f

High ability to answer: https://vimeo.com/706219960/17fc9899e9