ABSTRACT

Background

Facial palsy rehabilitation therapy plays an essential role in treating facial palsy.

Purpose

This study aimed to gain insight into therapists’ perceptions and attitudes toward facial palsy rehabilitation therapy and to examine whether therapists could be categorized into distinct groups based on these attitudes and perceptions.

Methods

Thirteen semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted in a purposive sample of therapists. Interviews were analyzed using thematic analysis. Next, a questionnaire containing questions about therapists’ characteristics and perceptions and attitudes toward facial palsy rehabilitation therapy was sent to all facial palsy rehabilitation therapists in the Netherlands and Flanders (n = 292). Latent class analysis (LCA) was performed to identify and analyze distinct groups of therapists.

Results

Seven themes were derived from the interviews: treatment goals, therapy content, indications, measurement instruments, factors influencing success, emotional support, and cooperation with colleagues. The questionnaire was filled out by 127 therapists. A 2-group structure consisting of a positive class and a negative class was found to fit the questionnaire data best. No distinction could be made regarding therapists’ characteristics.

Conclusion

Considerable variation in stated treatment practices was present among therapists. Therapists could be classified into 2 groups. This study raises several hypotheses that require further study.

Introduction

Facial palsy is a peripheral nerve injury characterized by the inability to contract the facial muscles, resulting in (partial) loss of facial expression. Approximately half of all facial palsies are idiopathic, commonly referred to as Bell’s palsy (incidence of 20–30/100,000 individuals per year) (Myers et al., Citation1991); the other half are due to a wide variety of causes such as iatrogenic or traumatic injuries, head and neck neoplasms, otologic diseases, and congenital birth defects (Hohman and Hadlock, Citation2014). Facial palsy patients experience various functional and psychosocial difficulties related to their inability to voluntarily contract the facial muscles. Myriad treatment options are available, including surgical, pharmacological, and physical therapeutic measures, all aimed at improving facial function and psychological wellbeing (Kleiss, Citation2015; Luijmes et al., Citation2017). Ultimately, treating facial palsy is a multidisciplinary team effort, in which the facial palsy rehabilitation therapist plays an essential role (Butler and Grobbelaar, Citation2017; Hohman and Hadlock, Citation2014; Van Landingham, Diels, and Lucarelli, Citation2018).

Although many different types of facial palsy rehabilitation therapy have been described in the literature, only a small amount of evidence is available on their efficacy (Baricich et al., Citation2012; Pereira et al., Citation2011). In the Netherlands, mime therapy was developed in the 1980s through collaboration between a mime artist and an otolaryngologist (Devriese, Citation1994). The treatment consists of facial movement exercises, self-massaging, relaxation exercises, stretching, mirror exercises, and education about verbal and non-verbal communication (Beurskens, Citation2003).

Although previous studies have shown a beneficial effect of rehabilitation therapy on facial palsy outcomes, there is some variation in the types of treatments used and in the heterogeneity of the study populations (e.g. difference in etiology of facial palsy) (Barbara et al., Citation2010; Beurskens and Heymans, Citation2003, Citation2006; Manikandan, Citation2007; Nakamura et al., Citation2003; Paolucci et al., Citation2019; Ross, Nedzelski, and McLean, Citation1991; Segal et al., Citation1995). Studies from various medical fields such as gynecology, urology, cardiology, orthopedic surgery, and physical therapy reported an association between practice patterns and care provider characteristics (Archer et al., Citation2009a; Archer, MacKenzie, Castillo, and Bosse, Citation2009b; Graham, Maddox, Itani, and Hawn, Citation2013; Hamilton et al., Citation2012; Harper, Brown, Foster-Rosales, and Raine, Citation2010; Li and Bombardier, Citation2001; Mikhail, Korner-Bitensky, Rossignol, and Dumas, Citation2005). Similarly, treatment practices among facial palsy rehabilitation therapists may vary, possibly leading to different treatment outcomes. In order to better understand the outcomes of facial palsy rehabilitation therapy, it is important to gain insight into the therapists’ perceptions and attitudes regarding the therapy and how these are related to the therapists’ characteristics.

Methods

A mixed methods study that combined qualitative and quantitative research methods was performed in mime therapists in the Netherlands and Dutch-speaking Belgium (Flanders). A sequential design was used, in which a qualitative study was followed by a quantitative study (). Approval from the Medical Ethics Committee was obtained from the University Medical Center Groningen prior to the start of this study (METc 2018/326). All participants provided written consent to participate in this study.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the longitudinal mixed methods study design. Shown are all individual steps in the study in the order in time.

Qualitative Study

All mime therapists in the Netherlands and Flanders were eligible for participation with the exception of the mime therapist involved in this study. In both the Netherlands and Flanders, mime therapists are either physical therapists or speech and language therapists, and they have all received structured education in the field of mime therapy. Purposive sampling with a maximum variation strategy was performed, aiming at the inclusion of different perspectives. Initially, five mime therapists were actively contacted by the first author: four leading figures in the professional community and one practicing in the same medical center as the authors. For further participant selection, a snowballing technique was used: participants were asked to name colleagues who would possibly be interesting to interview, preferably with different views on mime therapy than their own. Therapists were approached via e-mail. Additionally, a balance between male and female therapists, physical therapists and speech and language therapists, and hospital-affiliated and non-hospital affiliated therapists was actively sought.

The in-depth interviews were semi-structured and audio-recorded. All interviews were performed at the work location of the mime therapist. An interview guide was used to ensure all relevant topics would be covered (Appendix 1 – Interview guide). The interview guide was updated during the interview process based on new themes emerging from the concurrent initial thematic analysis. Questions such as “What do you mean by that?” or “Could you elaborate on that?” were used to ensure the perspective of the mime therapist was covered and to limit interviewer bias. The main interviewer was the first author, who is trained as a physician and who received training on qualitative research methods before the start of this study.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and sent back to the mime therapists for member checking. Afterward, the transcripts were analyzed by two researchers, who independently used the principles of thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, Citation2006). This is a method for identifying, analyzing, organizing, describing, and reporting themes found within a data set. Thematic analysis is a useful method for examining the perspectives of different research participants, as it highlights similarities and differences. First, transcripts were coded using line-by-line readings. Important statements and sentences were identified and initial codes generated. Initial codes were cross-referenced between the coding investigators and initial themes were generated. After every few interviews, research meetings were held by the first, second, and last author so as to gradually generate the list of final themes and quotes.

Quantitative Study

After the qualitative study was finalized and themes were established, a quantitative, cross-sectional study was performed to gain insight into the perspectives of the therapist group in its entirety and ultimately identify different types of mime therapists. A questionnaire was developed covering all seven themes generated from the interviews. The questionnaire statements were derived from the most important or contradictory findings from the interviews. The final questionnaire consisted of two parts. The participant’s personal and work -related characteristics were collected. Additionally, questions were asked covering the most important and most controversial themes from the interviews. The majority of the questions concerned treatment dilemmas (e.g. “What would be more important in the treatment of the above described patient according to you? (A) relaxation and massage or (B) controlled coordination exercises?”). Participants were also asked to what extent they agreed with a certain statement on a 100-mm visual analogue scale (0 = absolutely disagree, 100 = absolutely agree). The content of the questionnaire was discussed within the research group including a mime therapist in detail in the developmental phase and subsequently pilot tested for comprehensibility in 3 mime therapists working at our institution who were not involved in the study. The questionnaire was distributed via RedCap (Vanderbilt University, TN, USA), an online survey distribution system, to all registered mime therapists in the Netherlands and Flanders who were on a list provided by the mime therapy course coordinator except for the therapist involved in this study (PUD). Multiple imputation, 20 imputations with predictive mean matching was performed using the IBM statistical package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0 (IBM, NY, USA) to estimate missing data in the questionnaire for the mime therapy-related questions.

To identify different groups of mime therapists, a latent class analysis (LCA) with robust maximum-likelihood estimation was performed in Mplus version 7.1. LCA models that ranged from 1 to 3 classes were tested primarily based on several criteria: Bayesian information criterion (BIC), Akaike information criterion (AIC), bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLRT) and Vuong–Lo–Mendell – Rubin likelihood ratio test (VLMR) for relative fit; entropy for class separation. Lower BIC and AIC values indicate a better fit. Significant BLRT and VLMR values indicate that the K-class model has a better fit to the data than the K-1 class model (Jung and Wickrama, Citation2008; Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén, Citation2007). A model with higher entropy is considered to have better class separation (Nylund, Asparouhov, and Muthén, Citation2007). Second, clinical interpretation (e.g. class prevalence and subgroup size) was used to select a model. Each participant was assigned to a class based on the latent class posterior distribution of the selected model. A 4-class model was run but contained a class with only two persons. Therefore, the 4-class model was considered to be unfavorable and was not further examined.

Descriptive data were presented using numbers and frequencies, means and standard deviations (SD), and medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Statistical differences in mime therapists’ characteristics were tested using SPSS. In case of nominal data, chi-square tests were used. For continuous data, Mann-Whitney U tests were performed due to non-normality of the data.

Results

Qualitative Study

Thirteen in-depth interviews with mime therapists were performed that lasted between 30 and 90 minutes. During the interviews, two researchers independently transcribed and analyzed the interviews. After the first seven interviews by the first author, a point of data saturation was reached. At this point, no new information could be gained from the therapists and interview transcripts. Therefore, the next three interviews were performed together with the second author, who indicated when a point of data saturation was reached. The last three interviews had already been scheduled at that point and were performed by the first interviewer.

In general, more experienced mime therapists were more explicit in voicing their opinions and beliefs (i.e. less use of phrases such as “I am not sure about that”) during the interviews. Their interviews also tended to take longer. However, the overall content of the opinions and beliefs of the experienced mime therapists was not considered to be drastically different from that of the less experienced mime therapists. In general, the interviews revealed that there is a need among mime therapists for more studies into mime therapy. Seven major themes were developed from the interviews: 1) treatment goals; 2) content of therapy; 3) indications; 4) measurement instruments; 5) factors influencing success; 6) emotional support; and 7) cooperation with colleagues.

Treatment goals

Two main treatment goals were improving symmetry of the face and increasing the ability to convey emotions. The focus on emotional expression in particular was stated by some therapists to be specific to mime therapy, as opposed to other forms of facial palsy rehabilitation therapy, such as neuromuscular retraining. Some therapists adhered to less strictly defined treatment goals and stated that mime therapy entails providing a patient with tools in order to cope with both the physical and psychosocial aspects of living with facial palsy. Individual patient goals were established with the patient and could be very specific.

The goal [of mime therapy] is optimal symmetry and expression of emotion.

Content of therapy

During the interview, it was difficult for the interviewers to gain an in-depth understanding of differences in treatment strategies between individual mime therapists. The therapists stated that mime therapy is highly individual and tailored to the wishes and personal needs of the patients. Most therapists referred to techniques and exercises they learned during their mime therapy course, which is centralized and was only offered at 1 location in the Netherlands and Belgium until recently. Some mime therapists stated that the actual coordinated movement exercises in the context of synkinesis were the core business of mime therapy. Advice on how to cope with paralysis was described to be part of their practical work because, in their experience, physicians often have too little attention and time for patients diagnosed with facial palsy.

Mime therapy is a combination of massage and exercise therapy.

Indications

The largest group of patients treated by the therapists consisted of patients with synkinesis or at risk of developing synkinesis, most of whom suffered from Bell’s palsy. These patients also have the most to gain from mime therapy because it requires at least some movement of the facial muscles in order to be possible. In contrast, patients with chronic flaccid paralysis have much less to gain from mime therapy because there is no existing movement to strengthen or alter. Some mime therapists also treated facial palsy patients after smile reanimation surgery. These mime therapists expressed the belief that mime therapy is essential for all patients who undergo smile reanimation surgery.

“If there is no movement at all you can’t really do anything. Well, except for providing some tips and tricks on how to deal with more practical issues such as drooling or spill of food when eating.”

Although not stated to be part of the core business of mime therapy, advice of how to cope with some practical disabilities resulting from paralysis could be given to any patient suffering from facial palsy, flaccid or synkinetic.

Measurement instruments

All therapists stated they use some kind of measurement tool to assess changes in facial function; however, the tools themselves and the frequency with which they were used differed considerably. The Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (SFGS) (Ross, Fradet, and Nedzelski, Citation1996) was used by all therapists. An advantage of this tool over the widely known House-Brackmann score (House and Brackmann, Citation1985), which was only used by a few therapists, was said to be that it provides detailed regional information on facial function and has a dedicated section on synkinesis, making a more detailed longitudinal assessment possible. Patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) were used less frequently and were not uniformly stated to be important. The most widely used PROM was the Facial Disability Index (VanSwearingen and Brach, Citation1996).

The use of photographic and videographic material was even more heterogeneous. Most mime therapists did use one or both to document changes in patients, although some mime therapists fully relied on their SFGS assessments.

As mentioned before, the assessment frequency differed greatly. Most mime therapists repeated their assessments as soon as they noted changes in facial function. Some only performed their assessment at the start and end of the treatment, and a very small number assessed at every visit.

The facial photographs, videos and, to a lesser extent, SFGS assessments, were used to remind patients during their treatment of how far they had come. Hence, they were used in managing patient expectations. Overall, measurement instruments were generally seen as supporting the therapy and not as essential elements in providing mime therapy.

Factors influencing success

The intrinsic motivation of patients was unanimously seen as the determining factor for the success of mime therapy. All therapists literally said “they have to do it themselves.” This principle was seen as a basic prerequisite for adherence to therapy.

(…) that someone is motivated is very important to me.

Another frequently mentioned factor for success was a certain level of intelligence. Mime therapy was considered to be a rather difficult form of therapy, and a certain level of intelligence was thought be necessary in order for a patient to understand which exercises are indicated at what moment and how these should be performed. In addition, a certain level of motor skills was described to be beneficial, as some people are more in contact with their face and can coordinate facial movements more easily.

The therapists did not state that therapy would fail in case the patient’s intelligence or motor skills were found lacking. They would then proceed to adapt their therapeutic and educational strategies to fit the specific needs of that patient. For some patients, they simplified exercises or adjusted treatment goals. Some variations were seen in the extent to which the therapists indicated who is ultimately responsible for treatment success. One therapist went as far to state that it was solely her responsibility to make the therapy work, whereas other therapists took a coaching approach to mime therapy that included more responsibility for the patient.

Ultimately it is my responsibility to make sure someone is being treated correctly.

Other less frequently mentioned factors were age (both very young and very old patients were stated to be more difficult to treat); a good working relationship with the mime therapist; the patient’s personality; the experience of the mime therapist; a calm attitude of the patient; and a healthy lifestyle of the patient.

Emotional support

The importance of emotional support given by the mime therapist was a recurrent theme in the interviews. All mime therapists stated that emotional difficulties resulting from facial palsy are a topic of discussion during the consultation. However, all mime therapists also stated they are not trained psychologists. When a patient’s psychological burden is too high, the patient will be referred to a psychologist. Clear differences in the extent of psychological involvement were present. Some mime therapists reported that emotional support for facial palsy patients is inseparable from the therapy itself, while others clearly stated that their primary focus is solely on the actual therapy and not on emotional support.

I feel that I should be open to [emotional support]

I do not go too deep into psychological support myself. That is not what I am trained for.

Cooperation with colleagues

Because relatively few patients are treated with mime therapy, therapists who had a colleague working alongside them perceived this as pleasant. Others formed loco-regional teams to discuss difficult patients with someone outside their own organization. A few mime therapists worked together with physicians in the treatment of facial palsy patients. They described this relationship as beneficial. The mime therapists without collegial support stated that this was generally not an issue because they could always discuss certain issues with the coordinator of the mime therapy course.

Quantitative Study

A total of 292 mime therapists were identified and invited to participate in the online questionnaire. After two reminder e-mails, 148 mime therapists (51%) responded, resulting in 106 fully completed questionnaires. Of 21 questionnaires, sufficient data were present to perform multiple imputation (> 80% complete). A further 21 questionnaires were assessed as being too incomplete and were not used.

The vast majority of the 127 mime therapists included in this study were women (n = 117 (92%)). Median (IQR) age of the therapists was 43.8 years (36.9; 52.1), and the majority lived in the Netherlands (n = 106 (84%)). Most mime therapists completed a bachelor-level program and did not work in a hospital setting. The mime therapists treated between 1 to 180 new facial palsy patients per year (median = 6) ().

Table 1. Comparison of therapist and work-related characteristics between the total sample and the two classes of latent class analysis.

Identification of classes

A 2-class model was best fitting according to the BIC, whereas the AIC showed better a fit for a 3-class model. The 2-class structure had the highest entropy, indicating it had the best class separation. Based on the entropy, BIC, and clinical interpretability, a 2-class structure was chosen ().

Table 2. Latent class structure selection.

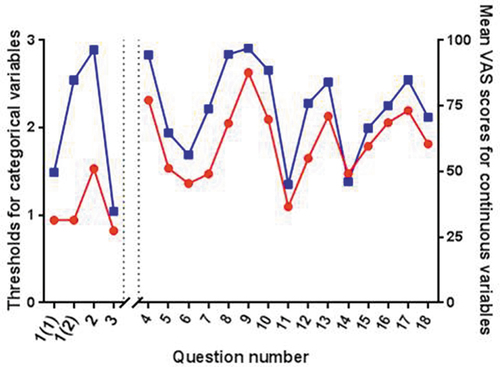

Questionnaire questions and the answers of both classes are presented in and , respectively. Class 2 generally gave higher scores or more positive answers to almost all questions from the questionnaire, compared with class 1 (). Question 14 (“How much time do you spend on emotional support of your mime therapy patients?”) was the only exception, as class 2 stated that they spend less time on emotional support compared with class 1.

Table 3. Developed questionnaire regarding mime therapy.

Figure 2. Answering patterns of the questionnaire questions of the 2 classes. Left are the thresholds for the categorical answering options, right are the mean values of the continuous answer scales. Red represents class 1, blue represents class 2. these findings indicate that class 2 therapists gave higher mean answers to all questions except for question 14 compared with class 1.

Association of classes with therapist characteristics

Therapist characteristics and work-related characteristics did not differ statistically significantly between both classes (). Therapists in class 2 did obtain a Master of Science degree more often (36.7% versus 23.0%), while physical therapists and speech and language therapists in the Netherlands commonly have a Bachelor of Science degree. Also, class 2 therapists had more experience regarding patient load (median 8.0 versus 5.5 new patients a year) and practiced mime therapy for a longer period of time (29.7% of class 2 practiced mime therapy training for more than 10 years versus 11.5% of class 1). Class 2 also worked in a university medical center more often (24.8% versus 3.8%), and a larger number of class 2 therapists valued working together with another professional (73.3% versus 57.7% for therapists, and 71.3% versus 61.5% for physicians).

Discussion

This study aimed to explore the attitudes and perceptions of mime therapists regarding their work and to see whether groups of therapists could be identified that exhibited different views on facial rehabilitation therapy. Hypothetically, these differences in attitudes and perceptions could lead to differences in treatment, which suggests that treatment outcomes may also vary.

Analysis of the in-depth interviews led to the identification of 7 major themes, some with more varying opinions between therapists (e.g. emotional support) than others (e.g. indications). As stated before, it was difficult to gain an in-depth understanding of the actual therapy practices because the therapists stated that these are highly individualized. However, several interesting findings resulted from the interviews. A certain level of intelligence and motor skills of patients was stated to be beneficial to treatment outcomes. Therapists said that they would adapt their therapies to the level of the patient, and sometimes this meant actually simplifying the exercises. Although it is not known whether this simplification changed the therapy outcomes for these patients, these outcomes and the methods to increase understandability of the therapy should be a topic of future research to ensure all patients receive the best treatment. The extent to which therapists offered emotional support varied significantly between therapists. A relationship between emotional support and treatment outcomes has not yet been established; however, it is plausible to suggest that emotional support influences the patient-therapist relationship and therapy adherence, among others. In general, very little is known about the psychological guidance of patients with facial palsy and the role of the therapist therein, making it a highly relevant topic for future studies. This was also corroborated by the mime therapists, who expressed a need for more research into this specific field during the interviews.

To generalize the qualitative findings, a questionnaire was created and sent to all registered mime therapists in the Netherlands and Flanders. From the LCA, a 2-class structure was found to best describe the data: class 2 generally gave higher scores or more positive answers compared with class 1. This indicates that those therapists expressed a more positive view toward the indications for, and the importance and effectiveness of mime therapy. No significant differences were found in personal and work-related characteristics, although it was noteworthy that class 2 therapists were more experienced and possibly more specialized. Differences between experienced and more inexperienced physical therapists in patient education practices have been described previously and could theoretically influence treatment outcomes (Forbes, Mandrusiak, Smith, and Russell, Citation2017). Studies comparing treatment results of experienced therapist and more inexperienced therapists could provide additional information.

The current study is the first to research the attitudes and perceptions of mime therapists regarding facial rehabilitation therapy and the possible differences therein. This study has, however, some limitations. The first limitation concerns the sample size. Although 292 therapists were invited to participate, only 127 questionnaires were collected, despite having sent out 2 reminders. This could imply a selection bias if the therapists that did not respond formed a distinct group that is now not included in the study. Therapists who treat very few facial palsy patients might not have felt the need to participate, which means that views of the more inexperienced therapists could be partially missing. Therapists with a very busy practice might have lacked time to participate, which means that views of the more experienced therapists could also be missing. Furthermore, with only 127 participants the strength of our LCA was limited, and structures with more than 3 classes could not be investigated. Multiple imputation was performed to make use of all the data present. This allowed for the inclusion of the answers of 21 therapists who only completed part of the questionnaire, even though multiple imputation does introduce imputation uncertainty to the data.

The interpretation of the 2-class structure was rather difficult. If both classes would have answered some questions very differently and other questions very similarly, the class identification could have been more easily attributed to the questions answered differently by both classes. In this study, class 2 gave higher scores/more positive answers to all questions compared with class 1. As mentioned before, this answering pattern can imply that therapists in class 2 had a more positive view on mime therapy in general. This was also apparent from the interviews, in which some therapists were more positive about treatment outcomes than others. However, this cannot exclude the fact that our findings to some extent represent an underlying response tendency not related to actual beliefs or practices of the therapist.

The findings from the current study are not directly applicable to clinical practice. Instead, they should be seen as a means to generate hypotheses that contribute to further research in this field. Considerable variation in attitudes and perceptions of facial rehabilitation therapists was found; however, it is not known whether these actually lead to different treatment choices and treatment effects. Participating observations would be necessary to study these phenomena, although these are extremely time-consuming. The exact magnitude of therapist’s influence on the improvement of facial function is not known. Prospective longitudinal follow-up studies that include multiple therapists in multiple centers are necessary to evaluate this effect.

Surprisingly, and contradictory to the findings from the interviews, the results from the questionnaire suggest that therapists think that teaching the patients compensation techniques (e.g. manual support of the lower lip while drinking) is more important than facial movement exercises. It can be hypothesized that this is because therapists are aware of the lack of information given to patients by their medical specialists, which means they will benefit greatly from such practical advice.

Also, quite a considerable number of therapists believe facial rehabilitation therapists can play a role in the treatment of patients undergoing dynamic reconstruction of the smile. To the best of our knowledge, the only published article claiming to show a beneficial effect of therapy in smile reanimation surgery is a before-after study in 11 masseter-to-facial nerve transfer patients without a control group (Pavese et al., Citation2016). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis found a beneficial effect of physical therapy after smile reanimation in terms of the development of a spontaneous smile (unpublished data). Although we do recognize the beneficial effect of physical therapy from our own clinic, we believe a true RCT with random allocation of patients to therapy or a waiting list after surgery would be a great addition to the knowledge about therapy in facial palsy patients.

In a recent report describing the experience of patients undergoing nerve-to-masseter-driven smile reanimation, only about half of the patients acknowledged the importance and beneficial effect of physical therapy and self-reported adherence to the physical therapy plan (Van Veen et al., Citation2019). Some therapists stated that their connection with a patient could influence the results patients get from their treatments. In other types of physical therapy, adherence to treatment and treatment outcomes are known to improve when the therapist-patient relationship is good (Hall et al., Citation2010). It would be interesting to see whether adherence to therapy and therapy outcomes differ depending not only on the actual treatment but also on the connection between a therapist and patient.

Conclusion

Facial rehabilitation therapy is known to be beneficial in patients with facial palsy. Previous clinical studies were limited because they were either highly controlled or observational studies of single therapists/institutions, which decreases generalizability. In both our interviews and questionnaires, considerable variation was found in the perceptions and attitudes of mime therapists regarding mime therapy and its content and effectiveness. This heterogeneity among therapists could potentially result in different treatment approaches and outcomes. Future studies should therefore measure treatment outcomes of facial palsy rehabilitation therapy involving multiple clinics and multiple therapists, and they should research the influence of the individual therapist on facial function recovery.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the therapists that have taken the time to be interviewed and/or fill out the questionnaire. We would also like to thank Sonja Hinzen for her language editing services.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Archer KR, MacKenzie EJ, Bosse MJ, Pollak AN, Riley LH 2009a Factors associated with surgeon referral for physical therapy in patients with traumatic lower-extremity injury: Results of a national survey of orthopedic trauma surgeons.Physical Therapy 899:893–905 10.2522/ptj.20080321.

- Archer KR, MacKenzie EJ, Castillo RC, Bosse MJ 2009 LEAP study group 2009b orthopedic surgeons and physical therapists differ in assessment of need for physical therapy after traumatic lower-extremity injury,Physical Therapy 8912:1337–1349 10.2522/ptj.20080200.

- Barbara M, Antonini G, Vestri A, Volpini L, Monini S 2010 Role of kabat physical rehabilitation in Bell’s palsy: A randomized trial.Acta Oto-Laryngologica 130:167–172 10.3109/00016480902882469.

- Baricich A, Cabrio C, Paggio R, Cisari C, Aluffi P 2012 Peripheral facial nerve palsy: How effective is rehabilitation?Otology and Neurotology 337:1118–1126 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318264270e.

- Beurskens CH 2003 Mime Therapy: Rehabilitation of Facial Expression. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Radboud University Press.

- Beurskens CH, Heymans PG 2003 Positive effects of mime therapy on sequelae of facial paralysis: Stiffness, lip mobility, and social and physical aspects of facial disability.Otology and Neurotology 244:677–681 10.1097/00129492-200307000-00024.

- Beurskens CH, Heymans PG 2006 Mime therapy improves facial symmetry in people with long-term facial nerve paresis: A randomised controlled trial.Australian Journal of Physiotherapy 523:177–183 10.1016/S0004-9514(06)70026-5.

- Braun V, Clarke V 2006 Using thematic analysis in psychology.Qualitative Research in Psychology 32:77–101 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Butler DP, Grobbelaar AO 2017 Facial palsy: What can the multidisciplinary team do?Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare 10:377–381 10.2147/JMDH.S125574.

- Devriese PP 1994 Rehabilitation of facial expression (“mime therapy”).European Archives of Oto-rhino-laryngology 12:s42–s43

- Forbes R, Mandrusiak A, Smith M, Russell T 2017 A comparison of patient education practices and perceptions of novice and experienced physiotherapists in Australian physiotherapy settings.Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 28:46–53 10.1016/j.msksp.2017.01.007.

- Graham LA, Maddox TM, Itani KM, Hawn MT 2013 Coronary stents and subsequent surgery: Reported provider attitudes and practice patterns.American Surgeon 795:514–523 10.1177/000313481307900528.

- Hall AM, Ferreira PH, Maher CG, Latimer J, Ferreira ML 2010 The influence of the therapist-patient relationship on treatment outcome in physical rehabilitation: A systematic review.Physical Therapy 90:1099–1110 10.2522/ptj.20090245.

- Hamilton AS, Wu X, Lipscomb J, Fleming ST, Lo M, Wang D, Goodman M, Ho A, Owen JB, Rao C, et al. 2012 Regional, provider, and economic factors associated with the choice of active surveillance in the treatment of men with localized prostate cancer.Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs 4545:213–220 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs033.

- Harper CC, Brown BA, Foster-Rosales A, Raine TR 2010 Hormonal contraceptive method choice among young, low-income women: How important is the provider?Patient Education and Counselling 813:349–354 10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.010.

- Hohman MH, Hadlock TA 2014 Etiology, diagnosis, and management of facial palsy: 2000 patients at a facial nerve center.Laryngoscope 1247:e283–e293 10.1002/lary.24542.

- House JW, Brackmann DE 1985 Facial nerve grading system.Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 932:146–147 10.1177/019459988509300202.

- Jung T, Wickrama KA 2008 An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling.Social and Personality Psychology Compass 21:302–317 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00054.x.

- Kleiss IJ 2015 Assessment of Facial Function in Peripheral Facial Palsy. Nijmegen, the Netherlands: Radboud University Press.

- Li L, Bombardier C 2001 Physical therapy management of low back pain: An exploratory survey of therapist approaches.Physical Therapy 814:1018–1028 10.1093/ptj/81.4.1018.

- Luijmes RE, Pouwels S, Beurskens CH, Kleiss IJ, Siemann I, Ingels KJ 2017 Quality of life before and after different treatment modalities in peripheral facial palsy: A systematic review.Laryngoscope 1275:1044–1051 10.1002/lary.26356.

- Manikandan N 2007 Effect of facial neuromuscular re-education on facial symmetry in patients with Bell’s palsy: A randomized controlled trial.Clinical Rehabilitation 214:338–343 10.1177/0269215507070790.

- Mikhail C, Korner-Bitensky N, Rossignol M, Dumas J-P 2005 Physical therapists’ use of interventions with high evidence of effectiveness in the management of a hypothetical typical patient with acute low back pain.Physical Therapy 8511:1151–1167 10.1093/ptj/85.11.1151.

- Myers EN, De Diego JI, Prim MP, Madero R, Gavilan J 1991 Seasonal patters of idiopathic facial paralysis: A 16-year study.Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 120:269–271 10.1016/S0194-5998(99)70418-3.

- Nakamura K, Toda N, Sakamaki K, Kashima K, Takeda N, Toda N, Sakamaki K, Kashima K, Takeda N, Sakamaki K, et al. 2003 Biofeedback rehabilitation for prevention of synkinesis after facial palsy.Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery 1284:539–543 10.1016/S0194-5998(02)23254-4.

- Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO 2007 Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A monte carlo simulation study.Structural Equation Modeling 144:535–569 10.1080/10705510701575396.

- Paolucci T, Cardarola A, Colonnelli P, Ferracuti G, Gonnella R, Murgia M, Santilli V, Paoloni M, Bernetti A, Agostini F et al. 2019 Give me a kiss! An integrative rehabilitative training program with motor imagery and mirror therapy for recovery of facial palsy.European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 561:58–67 10.23736/S1973-9087.19.05757-5.

- Pavese C, Cecini M, Lozza A, Biglioli F, Lisi C, Bejor M, Dalla Toffola E 2016 Rehabilitation and functional recovery after masseteric-facial nerve anastomosis.European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 523:379–388

- Pereira L, Obara K, Dias J, Menacho M, Lavado E, Cardoso J 2011 Facial exercise therapy for facial palsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis.Clinical Rehabilitation 257:649–658 10.1177/0269215510395634.

- Ross B, Nedzelski JM, McLean JA 1991 Efficacy of feedback training in long-standing facial nerve paresis.Laryngoscope 1017:744–750 10.1288/00005537-199107000-00009.

- Ross BG, Fradet G, Nedzelski JM 1996 Development of a sensitive clinical facial grading system.Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 1143:380–386 10.1016/S0194-5998(96)70206-1.

- Segal B, Hunter T, Danys I, Freedman C, Black M 1995 Minimizing synkinesis during rehabilitation of the paralyzed face: Preliminary assessment of a new small-movement therapy.Journal of Otolaryngology 24:149–153

- Van Landingham S, Diels J, Lucarelli M 2018 Physical therapy for facial nerve palsy: Applications for the physician.Current Opinion in Ophthalmology 295:469–475 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000503.

- Van Veen MM, Dusseldorp JR, Quatela O, Baiungo J, Robinson M, Jowett N, Hadlock TA 2019 Patient experience in nerve-to-masseter-driven smile reanimation.Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery 728:1265–1271 10.1016/j.bjps.2019.03.037.

- VanSwearingen JM, Brach JS 1996 The facial disability index: Reliability and validity of a disability assessment instrument for disorders of the facial neuromuscular system.Physical Therapy 7612:1288–1300 10.1093/ptj/76.12.1288.

Appendix 1 – Interview guide

Background

Age

Education/training

Career path

Description of work setting + facial palsy patient workload

General

What is mime therapy?/What does mime therapy consist of?

Work mechanism mime therapy

Indications?

Chronic versus acute paralysis

Flaccid versus non-flaccid paralysis

Smile reanimation surgery

Botulinum toxin treatment

Mime Therapy Practice

How to determine the exact treatment?

Different therapy for different types of palsy (e.g. flaccid versus synkinetic)?*

Changes in practices during your career path?*

Intensity treatment? Time & frequency

How do you define when the therapy is completed?*

Importance of education

How do you measure progress (e.g. sunnybrook, questionnaires, etc)?*

Other

Difference with other types of facial rehabilitation therapy

Electrostimulation/EMG/acupuncture or other techniques?

E-modules/video programs?*

Other therapists (preferably with a divergent view toward mime therapy)

*Additional topic that was added to the interview guide during the interview process.