ABSTRACT

Background

Involvement of families in physiotherapy-related tasks of critically ill patients could be beneficial for both patients and their family. Before designing an intervention regarding family participation in the physiotherapy-related care of critically ill patients, there is a need to investigate the opinions of critically ill patients, their family and staff members in detail.

Objective

Exploring the perceptions of critically ill patients, their family and staff members regarding family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks of critically ill patients and the future intervention.

Methods

A multicenter study with a qualitative design is presented. Semistructured interviews were conducted with critically ill patients, family and intensive care staff members, until theoretical saturation was reached. The conventional content method was used for data analyses.

Results

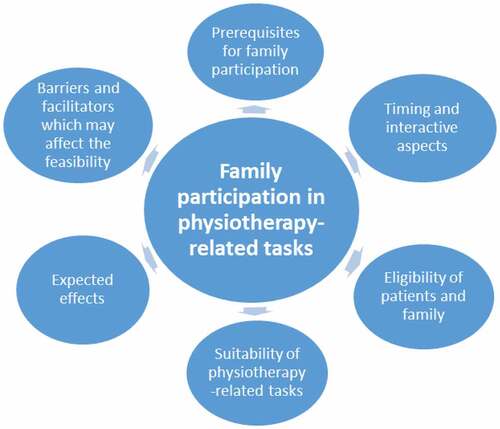

Altogether 18 interviews were conducted between May 2019 and February 2020. In total, 22 participants were interviewed: four patients, five family members, and 13 ICU staff members. Six themes emerged: 1) prerequisites for family participation (e.g., permission and capability); 2) timing and interactive aspects of engaging family (e.g., communication); 3) eligibility of patients and family (e.g., first-degree relatives and spouses, and long stay patients); 4) suitability of physiotherapy-related tasks for family (e.g., passive, active and breathing exercises); 5) expected effects (e.g., physical recovery and psychological wellbeing); and 6) barriers and facilitators, which may affect the feasibility (e.g., safety, privacy, and responsibility).

Conclusion

Patients, family members and staff members supported the idea of increased family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks and suggested components of an intervention. These findings are necessary to further design and investigate family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks.

Introduction

An admission to an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is often associated with a decrease in physical function and the emergence of ICU acquired weakness (ICU-AW) (Hermans and Van den Berghe, Citation2015; Parry and Puthucheary, Citation2015; Piva, Fagoni, and Latronico, Citation2019). Survivors of critical illness can experience new or worsening impairments in physical, cognitive and/or mental health (Rawal, Yadav, and Kumar, Citation2017). Early physical rehabilitation in the ICU can improve patients’ physical function, shorten ICU length of stay, and may reduce adverse psychological effects (Needham et al., Citation2010; Pandharipande et al., Citation2017; Parker, Sricharoenchai, and Needham, Citation2013). The psychological impact of an ICU admission is not limited to the patients, but may affect the mental health of their family members as well (Alfheim et al., Citation2018; Alfheim et al., Citation2019; Davidson, Jones, and Bienvenu, Citation2012; Garrouste-Orgeas et al., Citation2010; McAdam et al., Citation2012; Pochard et al., Citation2001).

Involvement of family in the ICU has the potential to optimize diverse outcomes. It can be beneficial for patients, family members and staff members (Al-Mutair, Plummer, O’Brien, and Clerehan, Citation2013; Haines, Citation2018; Kean and Mitchell, Citation2014; Kynoch, Chang, Coyer, and McArdle, Citation2019; Liput, Kane-Gill, Seybert, and Smithburger, Citation2016; McKiernan and McCarthy, Citation2010; Olding et al., Citation2016). It has been suggested that engaging families could humanize the patient illness and recovery experience, might enhance psychological well-being for both patients and family, could decrease the strain of families during a crisis, and might improve family member’s ability to cope with the patients’ situation by giving them a purposeful role (Al-Mutair, Plummer, O’Brien, and Clerehan, Citation2013; Haines, Citation2018; Kean and Mitchell, Citation2014; Kynoch, Chang, Coyer, and McArdle, Citation2019; Liput, Kane-Gill, Seybert, and Smithburger, Citation2016; McKiernan and McCarthy, Citation2010; Olding et al., Citation2016). In addition, active involvement can support staff by utilizing relatives as a supporting resource to deliver care outside of constrained time that staff members have (Haines, Citation2018). Since both early mobilization, physical exercise and family engagement were found to be beneficial in the daily care of critically ill patients (Pun et al., Citation2019), family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks could be promising (van Delft, Valkenet, Slooter, and Veenhof, Citation2021). Physiotherapists treat patients usually once a day due to constrained time, nurses often lack the time to help patients with their exercises or mobilization, and family is often not consulted to assist during the exercises, while they may be present at the bedside (Haines, Citation2018). Interventions aiming to increase family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks could, in addition to the previous mentioned benefits, optimize patients' physical function by increasing the frequency and thereby impact of physical rehabilitation. A recent review (van Delft, Valkenet, Slooter, and Veenhof, Citation2021) and viewpoint (Haines, Citation2018) demonstrate that there are positive attitudes among patients, family members and staff members toward family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks with critically ill patients. Haines thinks that family members can be engaged in many practical low-cost, high-value rehabilitative activities of critically ill patients (Haines, Citation2018). However, limited research has been done into the development, feasibility and effectiveness of interventions regarding family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks (van Delft, Valkenet, Slooter, and Veenhof, Citation2021).

The Medical Research Council (MRC) framework can be used for developing and implementing complex interventions (Craig et al., Citation2008). The first phase of this framework is the development phase. The first step of this phase was to identify what is already known about family participation physiotherapy-related tasks (van Delft, Valkenet, Slooter, and Veenhof, Citation2021). The next step is to identify and develop a theoretical understanding of the likely process of change. In this stage, it is crucial to gain knowledge on the area of concern, to get an understanding of the prospective users and their context, and determine which values and requirements the different stakeholders deem important to include in the further design of the intervention (Craig et al., Citation2008). Before further designing an intervention regarding family participation in the physiotherapy-related care of critically ill patients, there is a need to investigate the opinions of ICU patients, their family and staff members in detail. It is important to examine when, how and in which physiotherapy-related activities that family could and would like to be involved. Therefore, to assess the feasibility of an intervention for family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks of critically ill patients, the aim of this study was to explore the perceptions and ideas of patients, their family and staff members regarding this topic and the future intervention.

Methods

Design

This is a multicenter study, using a descriptive qualitative design. This study is the second step in the development phase of the MRC framework (Craig et al., Citation2008). The first step in the development phase was a systematic review to summarize the existing evidence about family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks of critically ill patients (van Delft, Valkenet, Slooter, and Veenhof, Citation2021). The method used in this study is based on the qualitative content method (Hsieh and Shannon, Citation2005), using individual semistructured interviews with open-ended questions. For reporting this study, the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig, Citation2007) were used.

Setting

To provide diversity allowing generalizability in terms of patient profiles, family experience and staff member opinions, this study was performed in an academic hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht (UMC Utrecht), and a non-academic community hospital, Diakonessenhuis (DH), which are both mixed medical-surgical adult ICUs. Unit one is a 36-bed medical, surgical, cardio, neuro transplant and trauma center. Unit two is a 12-bed medical surgical community ICU. The study protocol was assessed and approved by the local Medical Ethics Committee (study protocol # 18–842). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants of this study.

Participants

For this study, critically ill patients, family members, and ICU staff members were included for semi-structured interviews. Overall inclusion criteria for participation were the ability to speak Dutch and an age of 18 years or older. Patients had to be admitted to the ICU for more than 72 hours and be both verbally and cognitively capable to talk for 30 minutes, as assessed by the treating physicians. Regarding family members, only first-degree relatives and spouses (partners) of patients admitted at the ICU for more than 72 hours were included. Involved staff members were as follows: ICU nurses (formal relevant postgraduate training completed), ICU physicians (formal relevant postgraduate training completed), physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and managers working in the ICU for at least 4 months. Staff members were purposively sampled for semistructured interviews, based on discipline and years of work experience. The inclusion of patients, family and/or staff members continued until nothing new was heard in two consecutive interviews and theoretical saturation, described as the point where no new themes other than the one already existing obtained from the data, was reached.

Study procedures

Patients and family

Eligible patients and family members received verbal and written information about the study. In study unit one (UMC Utrecht), the first author approached potential participants face-to-face, provided information, answered questions, and asked for participation. In study unit 2 (DH), the enrollment was performed ditto by a research assistant (PT, BSc). Both researchers were female and also work as physiotherapists in the ICU, resulting in the possibility that there was a prior relationship to the patient and/or family as part of clinical care. The interviews with patients and/or family members were conducted at the end of the patients' ICU stay or within the first two days after discharge from the ICU. The interviews had a maximum of 30 minutes and took place in a quiet room according to the participants’ wishes (i.e., family room or meeting room in the ICU or in the patient room).

Staff members

All ICU staff members that met the inclusion criteria received an e-mail from the first author with information about the study and the question to participate in this study. Responses were selected based on discipline and years of work experience, and subsequently, an interview date and time was set by e-mail. Since the primary researcher also works as a physiotherapist at UMC Utrecht, it is possible that there was a professional relationship with staff members established prior to study commencement. The interviews had a maximum of 30 minutes and took place in an office in the ICU, privately.

Data collection

The semistructured interviews were guided by a topic list with open-ended questions: one for the patients, one for family, and one for staff members (Appendix A). The topic lists were developed by the first author (LvD), who had done a course for qualitative research and conducting interviews, and reviewed by the research team. All interviews were conducted by the first author and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were interviewed in random order. In addition to the interview data, the following data were collected for patients: age, sex, reason for ICU admission, length of ICU stay at the moment of the interview, and cause of ICU admission. Data collected for the family members were age, sex, relationship to the patient, and cause of ICU admission of the patient from his/her family member. For staff members, age, sex, profession and the number of years of working experience on the ICU were collected. To warrant the quality and consistency of the interviews, a second investigator (CV) listened back the first three interviews and evaluated and discussed these findings before continuing with the interviews.

Data analyses and trustworthiness

The conventional content approach was used for analysis (Hsieh and Shannon, Citation2005). The objective of this method is to systematically transform a large amount of text into a highly organized and concise summary of key results. Text was read verbatim to interpret its meaning and to start dividing up the text into smaller parts, called meaning units, before starting with coding. Coding involved assigning a “label” to a segment of text (the meaning units) to represent the meaning derived from that text. After this initial coding phase, common codes were sorted for the identification of (sub)categories. Using the process of abstraction, all the codes were categorized and categories were combined until all interview data was reduced to a few main categories, which are in this study labeled as major themes. The final analytical phase resulted in a narrative story line that accounted for the major themes and explained the research question. NVivo version 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, Australia) was used for all analyses.

The following strategies were incorporated to enhance credibility. The first three interviews were independently coded by two researchers (LvD and KV). To create consistency and equality in the data analysis, codes were discussed and subsequently categorized and themes were selected. After creating consensus about the codes, categories and major themes, the following interviews were analyzed by one researcher (LvD), and when found, appropriate new codes, categories and major themes were formulated until no new themes were obtained. To assure rigor and trustworthiness, finalized analyses were checked and suggestions were provided by a second researcher (KV) before the final thematic analysis of all qualitative data was produced. Consecutively, a consensus meeting was organized with two other researchers (CV and AS) to discuss the final categories and themes. In order to assure participant validation, a member check was performed at the end of each interview by providing a verbal summary of the findings, and by performing a member check of the final findings with two interviewed staff members.

Findings

Sample characteristics

Altogether 18 interviews were conducted between May 2019 and February 2020 of which four were with a patient and their family member simultaneously. In total 22 participants were interviewed; Four patients, five family members, and 13 ICU staff members (). The patients were mostly female (75%) with a mean age of 61 (Standard Deviation (SD) 6). Most family members were male (60%) and partner (80%) of the patient, with a mean age of 57 (SD 12) years. The majority of the interviewed ICU staff members were female (77%) and nurse (46%), with a mean age of 44 years (SD 12). provides detailed information of the participant characteristics. In one interview, the recording equipment failed, so field notes were made.

Table 1. Characteristics of the interviewed participants.

Main findings

Both patients, family members and ICU staff members supported the idea of increased family participation in ICU physiotherapy-related care and contributed to suggesting relevant components of an intervention. Six major themes emerged: 1) prerequisites for family participation; 2) timing and interactive aspects of engaging family; 3) eligibility of patients and family; 4) suitability of physiotherapy-related tasks for family members; 5) expected effects; and 6) barriers and facilitators, which may affect the feasibility (). See Appendix B for a summary of quotations divided per major theme and Appendix C for a full overview of the major themes and (sub)categories.

Prerequisites for family participation

The most frequently mentioned was that participation should be voluntary; family members must really want to get involved in the care of their loved ones.

Yes and therefore what is important, I think you should tell family that it is not a must! That it is allowed, but if you don’t want to, you don’t have to. And if you say later I don’t want it anymore, then that’s okay too. [ID 3, nurse]

In addition, the minority of staff members stated that also patients should agree, whenever possible. All staff members agreed that the ultimate responsibility regarding family participation should lie with the bedside nurse and/or physician. However, deciding which physiotherapy-related activities could be done by the family member should be decided by the physiotherapists, based on the patients’ physical condition. One team manager and nurse mentioned that, to guarantee continuity, it is important that most nurses support the program. Other prerequisites, which were often stated, were that family participation should always be an addition to normal physiotherapy care and that it must be tailored per patient, per family member, and per day.

But I think that it can differ greatly per patient or per case. And per day perhaps. But then I think as physio and nurse you have to communicate very good about it. [ID 16, nurse]

Timing and interactive aspects of engaging family

Staff members talked about the right time to appoint, offer and involve family. Most of them stated that family members should be allowed to participate when the patient is medically stable. Creating awareness about the possibility for family participation should start earlier, by naming the options for participation already in the first days of ICU admission. Furthermore, they thought that family participation may change over time. During the first phase of admission, family is likely to stay on the background more as they may be overwhelmed by the ICU environment and medical situation of their critically ill loved one. When patients become medically stable and the ICU environment becomes more familiar for family members, the readiness for family participation may increase.

Staff members find it challenging how to involve family, and two concepts were often discussed: the communication with family members and the way of offering. In the interviews, staff members agreed that the first contact with family members is best done by the nurses since they see them most often. It was suggested that if a family member wants to participate, the physiotherapist can subsequently approach them for further explanation and training.

I think that nurses are good point to start because they see the family members more often, even in the evenings when we are not there. So I think it is certainly useful but the nurses are also busy enough, so I think it is a nice task for physiotherapist to explain it to the family afterwards. But it is nice if nurses take the first step and the first contact and information [ID 6, occupational therapist]

All staff members decided that guidance of family is very important; it starts with clarification and clear instructions, followed by practicing the physiotherapy-related tasks together. In addition, they agreed that interim evaluation, supervision and feedback are crucial.

So that the physiotherapist really should do it the 1st time together, and maybe also evaluate regularly with family and how they are doing or if they have questions. I don’t think you can just give a booklet about family participation, what can you do yourself, get started [ID 16, nurse]

Regarding the activities one offers to the family to participate in, staff members think that it is important to set boundaries in advanced and predefined activities in which family members can participate. The majority of nurses mentioned the option where family members can choose tasks they feel comfortable with.

Various options were mentioned about how to offer it (in which form) to the family. Participants agreed with something tangible instead of only verbally. Examples of forms that were named are a folder/booklet, a list/poster with activities, and notes in a patient dairy.

Eligibility of Patients and Family

Participants had a clear opinion concerning the eligible patients, in terms of patient groups where family is allowed to participate in physiotherapy-related tasks or not. Most staff members mentioned patients with a long duration of ICU admission (e.g., admitted more than a week) and/or weak (e.g., ICU-AW) patients who will enter a rehabilitation process after ICU discharge as target groups. A few nurses stated that family of all patients receiving physiotherapy should be involved. Staff members agreed that patients who should be excluded are hemodynamic unstable, septic patients and patients with “no touch policy” due to increased intracranial pressure. Staff members also mentioned the protocolled short-stay surgery patients for exclusion because they already have strict mobilization and physiotherapy protocols. In addition, some participants had doubts about sedated patients since they cannot give permission and are mostly still medically unstable.

Well I would like it if we do offer that, that it does not only have to be patients’ with a rehabilitation process, but also ordinary patients who are here longer, the long-stayers, e.g. people after neuro trauma or people after, whatever, you know them also, there it can really be an advantage. [ID 7, physician]

Regarding eligible family members, the interviewed participants mainly thought first-degree relatives (i.e., parents, children, brothers and sisters) and spouses/partners. Most frequently mentioned by patients, family and staff members, was the relationship between the family member and the patient. Not all family members should participate in physiotherapy-related tasks since they may have objections to become a caregiver. The difference between sons and daughters was mentioned by a patient, where her daughters wanted to help and her sons not. In addition, one physician stated that young people are more used to participate (“doing it together”) than the older generation (i.e., 70 and older).

Yes, I think that they see their mother mainly as a mother, and not, because as soon as something will happen here, my sons will also leave. My daughters-in-law stay, they don’t mind, but the kids, boys, are leaving. [ID 11, patient]

Suitability of physiotherapy-related tasks for family members

Many different activities were named by staff members, patients and family members themselves. Staff members thought that suitable physiotherapy-related tasks can vary daily, due to the changing situation and physical functioning of the patient. Concerning physiotherapy-related tasks, passive exercises/passive range of motion (ROM) for the prevention of contractures, active exercises to increase or maintain muscle function/strength, and breathing exercises (e.g., incentive spirometer) were mentioned most.

If people are good enough that you give them an incentive spirometer something where people often don’t think of themselves to practice. That you say to the family, let them practice with that incentive spirometer, even if they only say it once, then it is already kind of, you already have a profit there. I don’t think about it every hour either … [ID 3, nurse]

In addition, nurses often considered massage as a possible task for family. Regarding mobilization out of bed, opinions were divided. Family members indicated that they would like to help with this activity, but most staff members consented as not all family members may be skilled to help. Letting them help will then result in more workload for the nurse of physiotherapist and possible patient unsafety. In addition, staff members think that mobilization should not be performed by family alone, but always together with staff, ensuring safety.

That may also depend on how it goes and how the family member helps. Someone can of course really help with mobilizing, but someone can of course also be too much on top of it, and then working against you. [ID 5, physiotherapist]

Expected effects

Several potential effects were identified. Often cited was the expectation that involvement of family members might reduce stress and anxiety for both patients and family members.

I think for the group thinking it’s too scary, who thinks everything is exciting/stressful, that you can lower the threshold (when they participate). If you notice gosh there is still just the one you love, there in bed, touching him, movements are possible. You can really mean something to him, that it is also very nice for their psyche, certainly. [ID 1, nurse]

Staff members (i.e., nurses, physiotherapist, physician, and team manager) mentioned that for patients, it might also improve their physical recovery and even facilitate discharge, when the frequency of physical exercise moments would increase.

Well maybe it is, in transferring a patient earlier (discharge ICU). I think that in the end, it might perhaps advance in the speed of the patient’s physical recovery. [ID4, team manager]

In addition, a few long-term effects were mentioned. Staff members expected the program to be valuable to mentally and physically prepare family and patients for the rehabilitation phase after ICU admission (i.e., the next ward, rehabilitation center, or at home).

Regarding the potential effects for staff members, opinions were divided. The majority of nurses indicated that it may save them time, but that they would only benefit from this in a later stage of the patients’ admission and that this would depend on the family member. The minority of nurses stated that they expected that family participation has no direct added value for them, in the sense that they do not have to do anything less when the family is participating in physiotherapy-related tasks.

There were also negative effects mentioned. Half of the nurses named the fear of family members participating too much, which might interfere with the patient or nurses wishes. Involving family too much could be counterproductive because patients might be going to rebel against their family members. Another unwanted consequence, which was indicated by nurses, is that family members could become overconfident and start doing things themselves they are not skilled in, resulting in unsafe situations.

Barriers and facilitators which may affect the feasibility

The relationship between the family member and the patient could be a factor of influence. Not all family members would be willing to participate in physiotherapy-related tasks and patients may not appreciate the help of a family member. The most important facilitator for family participation during ICU admission was considered caregiver by the family member before ICU admission.

Staff members often mentioned that the family may find it scary to perform physiotherapy-related tasks with the patient because of the many lines, equipment and alarms in the room. However, the interviewed family members did not name that.

Sometimes you are a bit afraid that you are touching the wrong line, but it is not that I really have the feeling that it is very scary, no. [ID 11, partner]

Besides, staff members agreed that not all family members are capable of participating physically and/or emotionally. Since patients’ safety is essential, they think it is necessary to criticize family members’ capability before they start participating in physiotherapy-related tasks. As for patients, they usually wear few clothes during their ICU admission jeopardizing patients’ privacy. However, this was mostly mentioned by staff members and not by patients themselves.

You have some family members who understand it very well, know exactly when you tell them what to do and stick to that, and you have families who are there and the moment an alarm starts they drop everything. Because then there will be a beep and then all at once “oh shit there is something going on”, then it is of no use to you, then you are actually guiding that family more than you monitoring your patient. [ID 3, nurse]

Finally, there were diverse barriers for staff members. Nurses stated that it could increase the workload of staff members because the assessment for capability, instructions and personal training may take time. Responsibility was also indicated by the majority of staff members since staff members are ultimately responsible for complications. One ICU team manager mentioned behavioral change as a possible barrier in the beginning because there is often resistance against something new.

I think the privacy of the patient and the safety. And especially with mobilization, that you can do that well, that safety can be guaranteed. If you had to do it normally with two nurses (transfer bed-chair), then not! [ID 16, nurse]

Discussion

This qualitative study on family participation in the physiotherapy-related care of ICU patients can be considered as an important step of the development phase of the MRC framework for developing and implementing a complex intervention (Craig et al., Citation2008). Findings of the current study demonstrate that patients, their family members and ICU staff members support the idea of increased family participation in the physiotherapy-related care of critically ill patients, but believe that diverse important requirements must be included in the further design and investigation of an intervention in this field.

The most important prerequisite seems to be that family participation should always be voluntary since not everyone wants to participate in the care. Current study results correspond to earlier studies reporting on family participation in ICU care, which also mentioned that the kind of relationship, younger age, non-European descent and previous ICU admission for their family member may influence the willingness to participate in patient care (Azoulay et al., Citation2003; Engström, Uusitalo, and Engström, Citation2011; Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018).

Involving families in physiotherapy-related tasks raises a number of concerns and possible barriers for the feasibility, which are comparable with barriers reported in previous studies focusing on family participation in ICU care; patient safety and privacy, family capability, and responsibility were often mentioned (Azoulay et al., Citation2003; Engström, Uusitalo, and Engström, Citation2011; Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018; Wong et al., Citation2019). Involving family in physical activities may risk adverse events such as accidental extubating or catheter removal (Wong et al., Citation2019). Therefore, it is of high importance that family receives structured information, training before participation, and evaluation moments (Azoulay et al., Citation2003; Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018; Kydonaki, Kean, and Tocher, Citation2019; Wong et al., Citation2019). In addition, family members' anxiety to participate were also cited as possible barriers in previous studies (Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018; Wong et al., Citation2019). Besides patients’ safety, patients’ privacy has to be taken into account as well. However, this may be more important when family is participating in nursing tasks such as washing (Engström, Uusitalo, and Engström, Citation2011), which might have higher thresholds for family and patients than rehabilitation-related tasks. In addition, not all family members are likely to be capable of participating (Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018; Kydonaki, Kean, and Tocher, Citation2019; Wong et al., Citation2019). This includes not only personal qualities of the family member such as functional factors (e.g., physical strength), psychological and emotional factors (e.g., willingness to be involved and emotional stability), and knowledge (e.g., disease and learning ability) but also the relationship between the family member and the patient (Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018). Staff members believe that it is important to maintain control over the situation and patient, since they are ultimately responsible (Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018; Kydonaki, Kean, and Tocher, Citation2019). It can differ per patient, per family member and even per day, whether participation, and which activities, is possible to execute. Therefore, there is a need for effective communication about rules and expectations (Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018; Kydonaki, Kean, and Tocher, Citation2019; Wong et al., Citation2019).

Multiple possible beneficial effects were mentioned in this study. Participation in physiotherapy-related tasks may generate a feeling of usefulness for family members, may decrease stress and anxiety for both patients and family, and may make patients feel more safe. These expectations are consistent with previous research investigating the effects of involving family in different types of care of critically ill patients (Amass et al., Citation2020; Black, Boore, and Parahoo, Citation2011; Skoog, Milner, Gatti-Petito, and Dintyala, Citation2016). Just as important, it may also promote physical recovery by increasing the frequency and thereby impact of physical rehabilitation, although this has not yet been investigated before. Many possible physiotherapy-related activities were indicated in the interviews, from relatively passive (e.g., PROM and massage) to active (e.g., active limb exercises, breathing training, and mobilization). Before developing an intervention and deciding which activities family members are allowed to perform, the goal of the intervention and clinical outcomes must be well-defined. If the intention is to increase physical functioning and promote physical recovery, then the emphasis should be on active physiotherapy-related tasks: active (limb) exercises, breathing exercises and/or mobilization. If the goal is only to reduce anxiety of families and patients or to make family feel useful, then passive physiotherapy-related tasks (e.g., massage or range of motion) may already be sufficient.

A major strength is that this is the first study focusing on physiotherapy-related care only. Another strength is the diversity of participants, since most of the previous qualitative exploration studies focusing on family participation in ICU care included staff members and/or family members only (Azoulay et al., Citation2003; Engström, Uusitalo, and Engström, Citation2011; Hetland, McAndrew, Perazzo, and Hickman, Citation2018; Smithburger, Korenoski, Alexander, and Kane-Gill, Citation2017; Wong et al., Citation2019). In the present study, critically ill patients, their family members and staff members were interviewed, resulting in valuable information from all stakeholders to be involved in family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks. This enables a better understanding of experiences, concerns and motivations, which is part of the first steps of the development phase of the MRC framework for developing and implementing a complex intervention (Craig et al., Citation2008). A limitation of the present study is that it was conducted right before the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the current pandemic, parts of the ICU care have been changed. For example, at this moment the visitation of loved ones in critical care has been minimized, resulting in fewer possibilities for family involvement. Additionally, the perceptions regarding family participation in the ICU might have changed due to the pandemic, whereby the findings of this study might be less applicable in the current pandemic and post-pandemic world. Future studies must take this into account and will experience the possible consequences. In addition, due to the COVID-19 crisis, the interviews had to stop early, and therefore, fewer interviews could be done with patients and family members in study center two. To improve the distribution between the two hospitals and participants, a few more interviews were planned in center two, but these were redundant because theoretical saturation had already been reached in center one. Another limitation is the fact that the researchers who approached the participants also worked as physiotherapists in the ICU, resulting in the risk of selection bias. Besides, for the sample inclusion of patients and their family, no prior selections in characteristics (e.g., gender, diagnosis, and admission duration) were made. This lack of purposive sampling could have influenced the credibility of this sample and generalizability of the results.

In conclusion, both patients, their family and staff members were found to have a positive attitude toward family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks and to recognize the added value of an intervention. However, the development of an intervention in this field is of high complexity and diverse requirements should be taken into consideration in the design and implementation. The goal of the intervention must be clearly defined before selecting the activities for family to participate in. Besides, the practical approach is challenging and influenced by diverse possible barriers and facilitators to keep in mind. Following steps are to merge these results and produce and test prototype(s). Since this is the first study focusing on this specific topic, a proper pilot study is needed to thoroughly evaluate the feasibility of an intervention to increase family participation in (active) physiotherapy-related tasks. Following the MRC framework, a pilot study is necessary to collect input to further design the final intervention before conducting a large-scale implementation and effectiveness study (Craig et al., Citation2008). When family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks of critically ill patients seems to be feasible, even in the postpandemic world, the effectiveness must be evaluated on relevant clinical outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alfheim HB, Hofso K, Smastuen MC, Toien K, Rosseland LA, Rustoen T 2019 Post-traumatic stress symptoms in family caregivers of intensive care unit patients: A longitudinal study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 50: 5–10. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2018.05.007.

- Alfheim HB, Rosseland LA, Hofsø K, Småstuen MC, Rustøen T, Alfheim HB, Rosseland LA, Småstuen MC 2018 Multiple symptoms in family caregivers of intensive care unit patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 55: 387–394. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.018.

- Al-Mutair AS, Plummer V, O’Brien A, Clerehan R 2013 Family needs and involvement in the intensive care unit: A literature review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 22: 1805–1817. doi:10.1111/jocn.12065.

- Amass TH, Villa G, Omahony S, Badger JM, McFadden R, Walsh T, Caine T, McGuirl D, Palmisciano A, Yeow M, et al. 2020 Family care rituals in the ICU to reduce symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in family members - A multicenter, multinational, before-and-after intervention trial. Critical Care Medicine 48: 176–184. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000004113.

- Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, Arich C, Brivet F, Brun F, Charles PE, Desmettre T, Dubois D, Galliot R, French Famirea Group 2003 Family participation in care to the critically ill: Opinions of families and staff. Intensive Care Medicine 29: 1498–1504. doi:10.1007/s00134-003-1904-y.

- Black P, Boore JR, Parahoo K 2011 The effect of nurse‐facilitated family participation in the psychological care of the critically ill patient. Journal of Advanced Nursing 67: 1091–1101. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05558.x.

- Craig P, Michie S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M, Petticrew M 2008 Medical Research Council Guidance. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. British Medical Journal 337: a1655. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655.

- Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ 2012 Family response to critical illness: Postintensive care syndrome-family. Critical Care Medicine 40: 618–624. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9.

- Engström B, Uusitalo A, Engström Å 2011 Relatives’ involvement in nursing care: A qualitative study describing critical care nurses’ experiences. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 27: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2010.11.004.

- Garrouste-Orgeas M, Willems V, Timsit J, Diaw F, Brochon S, Vesin A, Philippart F, Tabah A, Coquet I, Bruel C, et al. 2010 Opinions of families, staff, and patients about family participation in care in intensive care units. Journal of Critical Care 25: 634–640. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2010.03.001.

- Haines KJ 2018 Engaging families in rehabilitation of people who are critically ill: An underutilized resource. Physical Therapy 98: 737–744. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzy066.

- Hermans G, Van den Berghe G 2015 Clinical review: Intensive care unit acquired weakness. Critical Care 19: 274. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0993-7.

- Hetland B, McAndrew N, Perazzo J, Hickman R 2018 A qualitative study of factors that influence active family involvement with patient care in the ICU: Survey of critical care nurses. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 44: 67–75. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2017.08.008.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE 2005 Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 15: 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Kean S, Mitchell M 2014 How do intensive care nurses perceive families in intensive care? Insights from the United Kingdom and Australia. Journal for Clinical Nursing 23: 663–672. doi:10.1111/jocn.12195.

- Kydonaki K, Kean S, Tocher J 2019 Family INvolvement in inTensive care: A qualitative exploration of critically ill patients, their families and critical care nurses (INpuT study). Journal for Clinical Nursing 29: 1115–1128. doi:10.1111/jocn.15175.

- Kynoch K, Chang A, Coyer F, McArdle A 2019 Developing a model of factors that influence meeting the needs of family with a relative in ICU. International Journal of Nursing Practice 25: e12693. doi:10.1111/ijn.12693.

- Liput SA, Kane-Gill SL, Seybert AL, Smithburger PL 2016 A review of the perceptions of healthcare providers and family members toward family involvement in active adult patient care in the ICU. Critical Care Medicine 44: 1191–1197. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000001641.

- McAdam JL, Fontaine D, White D, Dracup KA, Puntillo KA 2012 Psychological symptoms of family members of high-risk intensive care unit patients. American Journal of Critical Care 21: 386–394. doi:10.4037/ajcc2012582.

- McKiernan M, McCarthy G 2010 Family members’ lived experience in the intensive care unit: A phenomenological study. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 26: 254–261. doi:10.1016/j.iccn.2010.06.004.

- Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, Pradhan P, Colantuoni E, Palmer JB, Brower RG, Fan E 2010 Early physical medicine and rehabilitation for patients with acute respiratory failure: A quality improvement project. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 91: 536–542. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.002.

- Olding M, McMillan SE, Reeves S, Schmitt MH, Puntillo K, Kitto S 2016 Patient and family involvement in adult critical and intensive care settings: A scoping review. Health Expectations 19: 1183–1202. doi:10.1111/hex.12402.

- Pandharipande PP, Ely EW, Arora RC, Balas MC, Boustani MA, La Calle GH, Cunningham C, Devlin JW, Elefante J, Han JH, et al. 2017 The intensive care delirium research agenda: A multinational, interprofessional perspective. Intensive Care Medicine 43: 1329–1339. doi:10.1007/s00134-017-4860-7.

- Parker A, Sricharoenchai T, Needham DM 2013 Early rehabilitation in the intensive care unit: Preventing physical and mental health impairments. Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports 1: 307–314. doi:10.1007/s40141-013-0027-9.

- Parry SM, Puthucheary ZA 2015 The impact of extended bed rest on the musculoskeletal system in the critical care environment. Extreme Physiology and Medicine 4: 16. doi:10.1186/s13728-015-0036-7.

- Piva S, Fagoni N, Latronico N 2019 Intensive care unit-acquired weakness: Unanswered questions and targets for future research. F1000Research 8: 508. doi:10.12688/f1000research.17376.1.

- Pochard F, Azoulay E, Chevret S, Lemaire F, Hubert P, Canoui P, Grassin M, Zittoun R, Le Gall JR, Dhainaut JF, et al. 2001 Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients: Ethical hypothesis regarding decision-making capacity. Critical Care Medicine 29: 1893–1897. doi:10.1097/00003246-200110000-00007.

- Pun BT, Balas MC, Barnes-Daly MA, Thompson JL, Aldrich JM, Barr J, Byrum D, Carson SS, Devlin JW, Engel HJ, et al. 2019 Caring for critically ill patients with the ABCDEF Bundle: Results of the ICU Liberation Collaborative in over 15,000 adults. Critical Care Medicine 47: 3–14. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000003482.

- Rawal G, Yadav S, Kumar R 2017 Post-intensive care syndrome: An overview. Journal of Translational Internal Medicine 5: 90–92. doi:10.1515/jtim-2016-0016.

- Skoog M, Milner KA, Gatti-Petito J, Dintyala K 2016 The impact of family engagement on anxiety levels in a cardiothoracic intensive care unit. Critical Care Nurse 36: 84–89. doi:10.4037/ccn2016246.

- Smithburger PL, Korenoski AS, Alexander SA, Kane-Gill SL 2017 Perceptions of families of intensive care unit patients regarding involvement in delirium-prevention activities: A qualitative study. Critical Care Nurse 37: e1–e9. doi:10.4037/ccn2017485.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J 2007 Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- van Delft LM, Valkenet K, Slooter AJ, Veenhof C 2021 Family participation in physiotherapy-related tasks of critically ill patients: A mixed methods systematic review. Journal of Critical Care 62: 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2020.11.014.

- Wong P, Redley B, Digby R, Correya A, Bucknall T 2019 Families’ perspectives of participation in patient care in an adult intensive care unit: A qualitative study. Australian Critical Care 33: 317–325. doi:10.1016/j.aucc.2019.06.002.