ABSTRACT

Introduction

Different cultures and societal structures influence the ethical experiences of physiotherapists.

Objective

The study aimed to discover and describe contextual shades of ethical situations experienced by physiotherapists in their global practice.

Methods

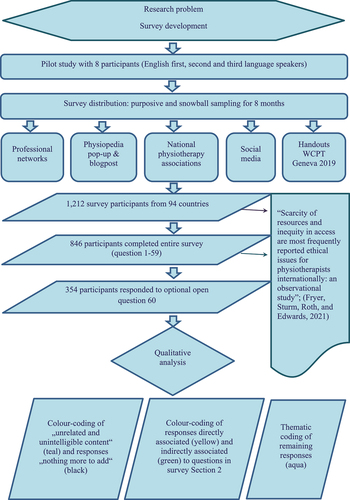

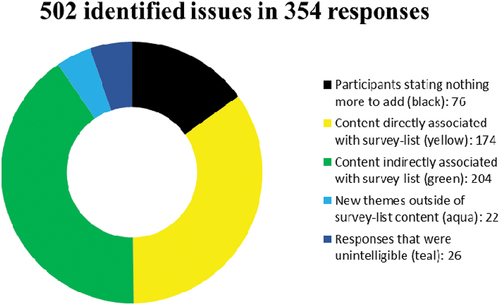

This paper reports the qualitative analysis of responses to an optional open question in an internationally distributed online survey (ESPI study) with 1,212 participants from 94 countries. All responses were coded to five categories describing the data’s relationship to the survey list of ethical situations. Data that described new ethical situations were analyzed thematically.

Results

Three hundred and fifty four individual responses to the optional survey question reported 400 ethical issues. Three hundred and seventy-eight of these issues were associated with the original survey questions. Twenty-two responses raised four new themes of ethical issues: lack of regulatory and/or accreditation policy and infrastructure, lack of recognition of the role and position of physiotherapists in healthcare, economic factors driving the conduct of practice, and political threats.

Discussion

Local contexts and pressures of workplaces and societies in which physiotherapists practice make it almost impossible for some practitioners to comply with codes of ethics. Physiotherapists need support and preparation to respond to local affordances and the complexity, ambiguity, and sometimes messiness of ethical situations encountered in their practice.

Conclusion

The findings highlight the relevance of cross-cultural research in the field of physiotherapy, and the necessity of investigating and bridging the gap between professional ethics theory and practice in diverse settings.

Introduction

Ethics research in physiotherapy is dominated by the experiences of western-based physiotherapists (Carpenter and Richardson, Citation2008; Chigbo, Ezeome, Onyeka, and Amah, Citation2015; Swisher, Citation2002). As a consequence, philosophy and literature influencing policy makers and underpinning the global profession’s Code of Ethics are largely based on Western values and experiences, implying that these are representative for all populations. However, emerging research from other world regions suggests that different cultures and societal structures influence the ethical experiences of physiotherapists (Chigbo, Ezeome, Onyeka, and Amah, Citation2015; Chileshe et al., Citation2016; Edwards, Wickford, Adel, and Thoren, Citation2011; Nyante, Andoh, and Bello, Citation2020; Oyeyemi, Citation2012; Souri, Nodehi Moghadam, and Mohammadi Shahbolaghi, Citation2020). The current understanding of ethical issues may be missing ethical experiences and understandings of physiotherapists in non-Western settings (Burgess and Jelsma, Citation2018; Edwards, Wickford, Adel, and Thoren, Citation2011; Ladeira and Koifman, Citation2017).

Recognition of diverse perspectives in ethics is already demonstrated in ethical guidance by some international health professions. For example, the World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) instructs its members to “reduce any vestige of colonialism or paternalism, and in turn foster a reciprocal partnership” (World Federation of Occupational Therapists, Citation2016). A stated objective of the Universal Declaration of Ethical Principles for Psychologists (International Union of Psychological Science, Citation2008) is “to encourage global thinking about ethics” and sensitivity and responsiveness to local needs and values. In comparison, the Code of Ethics of the International Council of Nurses (Citation2012), World Medical Association (Citation2006), and World Confederation for Physical Therapy (Citation2011) share a Western bioethical focus on obligations to the individual. A limitation in how the physiotherapy profession understands the international challenges of ethical practice is a risk to physiotherapists being provided with appropriate professional guidance and support for sustaining their ethical practice.

The World Physiotherapy Association (WCPT) is an international body that represents 125 physiotherapy associations from all world regions and provides guidance on their practice standards including ethical codes (World Physiotherapy, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). It was founded in 1951 by 11 national physiotherapy associations, of which South Africa represented the only non-Western country (World Confederation for Physical Therapy, Citation2001). The WCPT’s first set of ethical principles was ratified in 1959 and continuously updated since then (World Confederation for Physical Therapy, Citation2011). These jointly held ethical principles strengthened the South African Society of Physiotherapy’s opposition to apartheid in the 1980s (World Confederation for Physical Therapy, Citation2011). Since 1995 eight ethical principles, including a policy statement on the ethical responsibilities of physiotherapists and member organizations, guide global physiotherapists’ ethical conduct (World Physiotherapy, Citation2019a, Citation2019b) (). The guidance incorporates Human Rights (United Nations, Citation2015) and the Principles of Biomedical Ethics (i.e. respect for autonomy, nonmaleficence, beneficence, and justice) of Beauchamp and Childress (Citation2019).

Table 1. Glossary of terms

Member organizations of World Physiotherapy are expected to “ensure that the association, or relevant regularity body, has procedures for monitoring the practice of their members, handling complaints, along with appropriate disciplinary procedures and sanctions for members whose practice falls outside their code of ethics or code of conduct” (World Physiotherapy, Citation2019b). Of all World Physiotherapy member countries only 12% can define the scope of professional practice independently; most of them (70%) are regulated by government (World Physiotherapy, Citation2021). In 81% of the member countries, registration is required to practice, and in 54%, the regulatory and registration authorities set specific standards of practice. In 23% of the member countries, such guiding standards do not exist (World Physiotherapy, Citation2021). There is a large variation between countries in the healthcare contexts, within which the physiotherapy profession operates, including direct access, referral systems, access to funding, professional recognition, and entry-level requirements. Direct access without restrictions is available in 31% of the World Physiotherapy member countries, including many non-Western countries such as Brazil, Ecuador, Mali, Niger, India, or Bangladesh. In 25%, direct access is not possible, including Western countries like Czech Republic, Austria, Greece, or Romania (World Physiotherapy, Citation2021).

Some ethical challenges experienced by physiotherapists may transcend national boundaries (Swisher, Citation2002), but are not relatable to all national sociocultural frameworks (Ladeira and Koifman, Citation2017). Oyeyemi (Citation2012) stressed that a national code of ethics needs to embrace historical, sociopolitical, and economic dimensions of a country to increase alignment of physiotherapists’ practice to it. Recognition of the need to consider specifics of physiotherapists’ work environment in ethical expectations and guidance have also come from Ghana (Nyante, Andoh, and Bello, Citation2020), Iran (Souri, Nodehi Moghadam, and Mohammadi Shahbolaghi, Citation2020), and Afghanistan (Edwards, Wickford, Adel, and Thoren, Citation2011). Burgess and Jelsma (Citation2018) from South Africa argued that the starting point for professional ethics is the context-based relationship with others involved (i.e. patient, caregivers/family, other health professionals, and teaching/learning environment) rather than an obligation to act in certain ways. Sociocultural circumstances can set limits on a professional’s (and patient’s) autonomous behavior (Burgess and Jelsma, Citation2018; Chigbo, Ezeome, Onyeka, and Amah, Citation2015). This suggests that the concept of moral agency for a physiotherapist must be understood as relational, with an ethical course of action to be determined within a complex web of relationships (Cherkowski, Walker, and Kutsyuruba, Citation2015; Delany, Edwards, Jensen, and Skinner, Citation2010; Edwards, Delany, Townsend, and Swisher, Citation2011; Watson, Freeman, and Parmar, Citation2008). Limitations to the usefulness of an ethical code document to guide this dynamic and situated nature of ethical practice have already been recognized in several countries (Delany, Edwards, and Fryer, Citation2019; Figueiredo, Gratão, and Fachin-Martins, Citation2016; Kulju et al., Citation2020).

Purtilo (Citation2000) highlighted the need for a profession to adapt to the conditions of a given time and place, what she calls the “social landscape.” Learning about physiotherapists’ shady shoals of everyday ethical practice is necessary for professional ethics knowledge to keep the pace (Swisher, Citation2002) and be up-to-date (Griech, Vu, and Davenport, Citation2020; Ladeira and Koifman, Citation2017) with changes in the social landscapes. Situated knowledge (Haraway, Citation1988) can encourage and assist physiotherapy associations to frame their codes of ethics in a way that is related to their own social contexts and ethical challenges (Delany, Edwards, and Fryer, Citation2019; Edwards, Delany, Townsend, and Swisher, Citation2011). It can also help to identify further areas for research, education, and support for the ethical practice of physiotherapists in all World Physiotherapy regions (Bates et al., Citation2019; Ladeira and Koifman, Citation2017). This paper reports findings from a larger project, the ESPI-Study (Ethical Situations in Physiotherapy Internationally), which aimed to describe the ethical landscapes for physiotherapists internationally. The objective of the research reported in this paper was to discover “ethical situations” (Swisher, Arslanian, and Davis, Citation2005) experienced by physiotherapists in their global practice beyond what is already known from the existing literature, and to describe the contextual shades of the reported situations.

Methods

Design

The research presented in this paper is part of a larger survey study (ESPI), which investigated the type and frequency of ethical situations in physiotherapy internationally. We used the SurveyMonkey tool (Version April 2018) to create an online survey in the English language. A survey design was used to seek the views of a large sample of physiotherapists located in different places. English language was chosen for the survey to support its access to the largest sample of physiotherapists worldwide as translation to the hundreds of different languages used across the global profession was not achievable. The study received ethical approval from the University of South Australia’s Human Ethics Committee (Reference # 201295) and the Institute of Rights and Ethics in Medicine of the University of Vienna by Dr Stefan Dinges (Ethics Vote 2/2018).

The survey was separated into three sections. Section 1 contains 13 demographic questions. Section 2 contains 46 questions asking frequency of experience of universally expressed ethical situations that were informed by the international literature, divided into four categories: (A) physiotherapist and patient interaction, (B) physiotherapist and other health professionals, including other physiotherapists, (C) physiotherapist and the system that they are working in, and (D) professional and economic ethical situations. We defined an ethical situation for participants as “any issue in which an ethical tension is created in the physiotherapist’s practice for example, a conflict of values, beliefs, or norms; uncertainty as to the appropriate ethical action to take; or distress arising from an inability to act in a way that met the professional’s (or the profession’s) ethical standards.” Section 3 contains one optional question (question 60) asking participants to “Please describe an ethical situation you have experienced which was not on the list.” Participant responses to Section 3 provide data for this paper.

Participants and data collection

We invited physiotherapists and physiotherapy students from all over the world to participate (). The survey was distributed online using purposive and snowball sampling within professional networks on social media, by contacting all national physiotherapy associations globally, promoting the survey with a paid advertisement on the free online database Physiopedia, and distribution of printed handouts at the WCPT Conference in Geneva 2019. The survey was open from October 2018 to May 2019. One thousand two hundred and twelve participants from 94 countries completed survey Section 1. Eight hundred and forty-six participants completed the entire survey. Three hundred and fifty-four participants responded to optional question 60, but 76 of these participants indicated with their response that they had “nothing more to add.” Therefore, there were a total of 278 participants who responded to question 60 with data for the analysis (). The findings from these responses are reported in this paper.

Table 2. Description of samples by World Physiotherapy regions

Demographic information about each age, gender, occupation, education, and payment sources is provided in Appendix 1. The survey findings of Sections 1 and 2 are reported in another paper (Fryer, Sturm, Roth, and Edwards, Citation2021).

Data analysis

Data were exported from SurveyMonkey. Quantitative data related to question 60 were analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS version 25.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) by RR. Percentages and frequencies were calculated for the numbers of participants and locations by RR, identified ethical issues, and allocation to survey categories by AS. A chi-square test (alpha = 0.05) compared numbers of responses between World Physiotherapy regions. We employed a descriptive coding method (Sandelowski, Citation2010). This coding sought to categorize intelligible and/or sufficiently detailed question 60 responses in one of the three ways in terms of their relationship to the items in the other part of the survey.

The 354 participant responses to question 60 varied considerably in their text length and detail. Some were not more than a few words, and others were descriptions of ethical issues occupying several paragraphs. Not all responses contained sufficient detail to be certain about the respondent’s intention and meaning. We adopted a guiding principle that we would accept each response as an ethical issue even if we could not easily classify the issue in terms of a breach of known ethical principles or as part of a professional code of ethics. Our methodological approach was to therefore include and analyze every response where possible.

Two researchers (IE and AS) coded all data from the 354 participant responses into one of the five categories shown in . Some responses contained data on more than one ethical issue and more than one category could be allocated to data within a response. Once we coded all data pertaining to the “nothing more to add” (black) and “unrelated or unintelligible” (teal) categories, there were 400 issues identified in the data for further coding. The two coders worked independently to initially allocate the issues expressed in responses to one of the three remaining categories (yellow, green, and aqua). First, a two-category approach was used to compare data to the existing survey questions listed in Section 2 (yellow and green). Issues that were identified as closely aligning with existing survey questions were placed in the yellow category. For example, we coded a question 60 response, describing family members requesting continuous physiotherapy for an actively dying patient as data directly associated with survey question 30, which asked participants about the frequency of experiences of concerns regarding treatment of terminally ill patients, and so placed these data in the yellow category. Issues that were related to an existing survey question but were expressed differently to the intent of the survey question were placed in a second green category. An example was data indirectly associated with survey question 52, which asked about the frequency of instances where lack of available evidence existed to support effective treatment. The coded data included responses referring to practitioners who chose or were pressured not to use evidence-based management for economic or other reasons of convenience, due to the different intent about the ethics of use of evidence-based practice.

The two researchers (IE and AS) further identified data in the responses that were not covered by either yellow or green categories. These responses were seen to describe new issues raised by participants outside of the existing survey questions listed in Section 2 and were coded separately in a third aqua category (). The two coders constantly reviewed each other’s work via exchange of documents and online Zoom meetings to resolve any differences in interpretation. A strong consensus resulted from these meetings. A third researcher (CF) then randomly chose 35 responses that had been coded by IE and AS for review and comparison. CF corroborated the existing coding but identified 9 responses for further clarification. Consensus was further reached via online Zoom meetings in all cases. Re-examining the data-coded green and aqua after a hiatus of several months, the coders IE and AS agreed that a few of the aqua-coded responses presented themselves as better fitting into the green coding and, in one case, into the yellow category.

Findings

Participants shared their individual responses to the survey’s final question 60 as their lived experience of ethical situations, which unfolded into different shades. Analysis of these responses identified a spectrum of contextually based ethical issues ranging from various expressions of and new perspectives on the survey’s original list of ethical situations to entirely different ethical issues.

Various expressions of and new perspectives on ethical issues in the original survey

We termed the wide range of expressions and perspectives on existing survey items as “shades” of ethical issues already expressed in the literature. About 40% of the identified issues in the question 60 data were situated in the survey category (B) physiotherapist and other health professionals (41.79%). The remaining data were distributed across survey categories: (A) physiotherapist and patient interaction (17.43%), (C) physiotherapist and the system that they are working in (21.33%), and (D) professional and economic ethical situations (19.45%). More participants than expected responded to question 60 from the Africa region (AR) and less than expected from the European region (ER) [Chi2 = 20,487, p < .001].

Different and new perspectives on the survey’s original list of ethical situations were concentrated on three situations. Almost 50 identified scenarios embodied different shades of the ethical situation “Physiotherapist aware of misconduct by other health professionals including other physiotherapists” that was listed as survey question 37 (29 directly/20 indirectly associated). There were 34 identified scenarios describing different shades of the ethical situation “Bullying or harassment of physiotherapist” that was listed as survey question 34 (12 directly/24 indirectly associated). And 24 identified scenarios were shades of the ethical situation “Conflict with another health professional about patient’s management” that was listed as survey question 41 (13 directly/11 indirectly associated). These three ethical situations represented more than a quarter (109) of the 400 identified scenarios in the question 60 data ().

Table 3. Frequency and category of qualitative coding for each original survey question

In our reporting of findings, the original voices of participants in quotes are presented “as written” in their response including any grammatical errors to honor the authenticity of their contributions. The participant’s identification number and World Physiotherapy region are identified with each quote. Where we have closely aligned our reporting of a particular scenario with the participant’s original wording we have also included their study identification number (#) and their region.

Question 37: physiotherapist aware of misconduct by other health professionals including other physiotherapists

The different shades of this ethical situation in the question 60 data were extensive. Many reported scenarios concerned a physiotherapist’s lack of appropriate skills or ignorance of evidence resulting in poor quality patient care. Other reported examples were physiotherapists not respecting a patient’s privacy, gossiping about patients or using inappropriate language. The issue of a physiotherapist working without license was expressed several times. Inadequate supervision of physiotherapy assistants or inappropriate handovers of duties from senior to junior physiotherapists were also reported examples of misconduct.

Another shade reported by participants was misconduct ordered by employers, such as not changing towels to save cleaning costs or a practice owner advising students to practice in a way that did not reflect current evidence. Lack of proper supervision of treatment sessions and patients being undertreated were also reported. Other shades described unethical behavior or betrayal from professional leaders and trusted others. These examples of misconduct were intertwined with perceived abuse of rank and power within organizations and institutions or within working relationships, such as

Orthopedic surgeon referring patient for ambulatory training following ORIF/hemiarthroplasty but informally advising nothing of such to be done due to failure of surgical procedure. (Participant 227, AR)

Other examples were a participant being aware of an intentional misdiagnosis to cover up previous medical malpractice and nonphysiotherapist stakeholders perceived to be taking part in clinical decision-making without being qualified. There were also reports of corrupt management in a public facility and an organization not employing enough qualified physiotherapists to save on wages. One participant described a specific example of a private company winning health service contracts while removing experienced physiotherapy staff for financial reasons and putting sports and exercise therapists in physiotherapist uniforms without nametags (#94, ER).

Participants expressed that acting as a moral agent in such situations of misconduct was not always supported by the organization’s systems. The data showed participants to be ethically sensitive about what was going on and going wrong, but struggling to decide if they should report it because of unknown repercussions or coworkers encouraging them to remain silent. One participant described reporting another health professional for falsifying patient records, but the other professional was protected by a line manager and no further action was taken (#270, ER). Some participants did not trust their organization’s anonymous reporting system. Others reported their ethical actions being ignored or, in one response, led to detrimental consequences for the participant:

Physiotherapist I was employed by was addicted to pain medications and I believe that was effecting her judgment. She also let a student Physiotherapist treat a patient and paid the student for the treatment. I reported this to the (national association) and student’s university. Nothing happened and I lost my job! (Participant 77, AWPR)

Question 34: bullying or harassment of physiotherapist by other health professional(S)

Often the lack of support for ethical practice reported by participants was accompanied by undue pressure either within a professional or organizational hierarchy. Some shades of this situation embodied an abuse of professional interdependency or neglect of a physiotherapist’s distress by higher ranked colleagues, supervisors, or leaders:

Observed precepting PT performing poor hand hygiene, less than skilled care, and documentation and care plans not relevant or truthful Reported to supervisors Bullied by that and I had to resign due to no support from management. (Participant 18, NACR)

Many reported situations of bullying or harassment by management or administration were perceived to increase the income of the facility. One participant described untrained planners questioning their clinical reasoning and making funding decisions against it (#298, NACR). Other participants described being pushed to gain more reimbursement dollars or pressured to make more money; otherwise, workers would be cut off (#115, ER), and managers admonishing the participant to schedule excessive numbers of patients attain their own bonuses (#110, NACR). Participants also reported being bullied by administration staff when they complained about the staff’s work, and power fights occurring between office and clinical staff by maneuvering schedules and patients:

PTs are reprimanded or challenged by their administration if the amount of units that they charge is insufficient. (Participant 238, NACR)

Bullying and harassment between colleagues, supervisors, and senior colleagues was mentioned several times. Peer-to-peer harassment within a professional association represented one shade, and badmouthing other clinics to doctors and patients represented another (#74, NACR). One participant reported witnessing a physiotherapist vilify a colleague; another reported a colleague interrupting and commenting on the participant’s assessment process, both situations occurring in front of patients. In a further reported example, an employer and colleagues pressured a participant to provide treatment that was not supported by available evidence. Senior physiotherapy leaders were described as undermining young early career physiotherapy researchers at their own workshops, in conferences, and on social media (#104, ER). An abuse of rank and power within the medical or professional hierarchy was another shade of this issue. Participants reported that their refusal to comply with the “unwritten laws” of the system sometimes had bitter consequences for them:

I was asked by a physician who was also financially invested in the clinic I was working for, to see an adhesive capsulitis patient 3x week for 4-6 weeks. This patient was clearly in the frozen stage and had limited insurance benefits. When I discussed with the physician I would provide a HEP at this time and follow-up with the patient in several weeks to see if she was nearly the thawing phase where therapy would be more beneficial and therefore maximize her limited visits, the physician bullied me and told me I had to follow his orders. I ultimately quit over this situation and despite giving 6 weeks notice, he sued me for breach of contract. (Participant 319, NACR)

Another participant described having to vacate their treatment room for a doctor, leaving them without an appropriate space to continue their work with the patient (#52, ER). Other participants reported being expected to treat patients under inappropriate or unsafe conditions, with limitations on their physical and mental ability to practice not being considered in working conditions, such as when working while pregnant.

Question 41: conflict with another health professional about patient’s management

Different shades of conflict occurred with other physiotherapists or referring doctors, with reported consequences including misdiagnosis, ineffective treatment, and failure to meet patient needs. The reported conflicts were often related to a professional hierarchy:

Patients receiving poor value care by medical provider (both specialist and GP). Have written to provider and discussed in depth with patients to avoid the same situation happening to them again. (…) the medicos have been reluctant to change their practice based on information/dialogue. (Participant 134, AWPR)

A recurring example in the response data was participants’ conflict with treatment plans by other health professionals that were perceived to be ineffective or to not meet the patient’s need. One example described the participant’s identification of a doctor’s prescription as inappropriate, creating conflict between the two professionals and the patient (#70, AR). In other examples, participants reported health professionals giving “false hopes” to patients regarding recovery, providing unnecessary medications, or demonstrating a lack of understanding for the patient’s psychosomatic pain.

Participants also reported the presence of conflicts of interest for other health professionals. In the quote reported above, the participant describes their attempt to incorporate a patient’s insurance limitation in the treatment plan in conflict with the doctor who was financially invested in the clinic and perceived to dictate time-intensive and resource-intensive therapies. Another participant described being asked by the administration to send hospital patients to a specific rehabilitation clinic despite perceiving the patients would receive poor value care (#324, AWPR). Some medical specialists were perceived to create barriers between physiotherapists and patients. A participant reported being expected to interrupt their treatment session when an intern doctor was running late because a physiotherapist was considered a lesser entity in the hierarchy of the hospital (#158, AR).

The issue of misdiagnosis occurred in several situations of conflict reported by participants. In one example, the participant noticed a misdiagnosis and discussed it with the general practitioner, but the doctor sat on their opinion, so the participant felt forced to lie to the patient about the issue (#48, ER). Participants also reported observing doctors performing surgery for financial gain with little clinical evidence and unlikely to improve the patient’s symptoms.

Ethical issues outside of the original survey

Different ethical issues to those listed in the original Section 2 survey questions were also identified in the question 60 data. There were 22 ethical situations identified in this aqua category. Thirteen of these situations were reported by participants located in the AWPR, four by participants from the AR, three by participants from the ER, and two by participants from the NACR. The different situations are described by the following four themes: 1) lack of regulatory and/or accreditation policy and infrastructure, 2) lack of recognition of the role and position of physiotherapists in healthcare, 3) economic factors driving the conduct of practice, and 4) political threats.

Theme 1. Lack of regulatory and/or accreditation policy and infrastructure

Participants reported situations of unregulated practice including physiotherapists practicing without license or with no governing protocols in place. In one case, the participants reported that the governing body was aware of the lack of license, but did not intervene (#138, ER). Other expressed concerns included the implications of a lack of regulation or lack of a code of conduct for the integrity of both professional practice and training. Some participants believed that a large unqualified workforce was causing the professions’ devalorization on sociopolitical and intra- and interprofessional levels:

(…) we must face to defaming our professions due many untrended people do this job without any degree so we must want to a central label council established in India such as MCI and DCI, which regulates the physical therapy courses and degrees. (Participant 209, AWPR)

Other examples of this theme were newly graduated physiotherapists not being sufficiently trained by their educational institutes or appropriately supported by their workplace. One participant described new graduates being sent by the government to rural areas without completing an internship first and “required to see 20 patients within 4 hours” (#32, AWPR). Another participant experienced an ethical dilemma when delivering end-of-life care to a patient being interrelated with harassment. This example identifies the lack of an adequate infrastructure on an institutional and sociopolitical level to provide adequate care:

A patient who was actively dying was brought to our rehab facility. I was informed by management that I was required to put him on physical therapy caseload, otherwise he would not be able to stay in our facility. He did not have insurance and was homeless. He was unable to participate in treatment and was in extreme pain due to an open abdominal wound that was leaking gastric contents. Nursing was unable to keep a wound vac on it because of the size and nature of the wound. Basically it was posed to me that I could “find some reason” to put him on therapy caseload so he could die peacefully in our facility or that he would have to be discharged out onto the street because the hospital contract paying for his stay was only valid as long as he received therapy services.” (Participant 21, NACR)

Theme 2. Lack of recognition of role and position of physiotherapists in healthcare

Expressions of this theme in the question 60 data were a lack of knowledge about the scope of physiotherapy by patients and other health professionals and at a societal level influencing how the profession is valued. In one example, a local dialect described physiotherapy only by passive applications (“warming/heating”). The devaluation of physiotherapy by other health professionals of higher rank and power was described, including the nonacceptance of physiotherapy as a necessity for serving the society. Participants reported their professional skills being underestimated or their scope of practice not known, such as physiotherapists being equated to the role of a masseuse:

People often don’t know about what physical therapists can treat and they get convinced for surgery too early (eg Knee arthroscopy, Hallux valgus surgery or other foot-problems).” (Participant 234, ER)

Several responses identified a lack of respect occurring between physiotherapists including examples reportedly witnessed on social media platforms. An interprofessional lack of respect toward physiotherapists was perceived to lead, in some examples, to surgeons not referring patients who could benefit from physiotherapy treatment. Participants believed that this was because the physiotherapists’ qualification was classified by the surgeon as being low or the patient ostensibly was made to believe that physiotherapy would not be worth trying. There was also a perception that this attitude about the physiotherapy profession was shared by some patients:

Patients think that physical therapy is not as important as medicine. So they don’t pay much respect and appreciation as they should which disheartens me. (Participant 222, AWPR)

Theme 3. Economic factors driving the conduct of practice

The overall tenor of this theme was that participants perceived money sometimes mattered more to health professionals than their patients. Examples included managers overriding clinical decisions and the participants being pushed to increase quantity of care at the cost of its quality. Instances of overtreating and overcharging patients were described. Injustice and inequity were seen to be fostered by some funding modalities:

Prioritizing clients on waiting list - in public health system was according to clinical need. Since change of disability funding, according to who is funded first. (Participant 41, AWPR)

Aggressively acquisitive healthcare politics in some countries were described as having unethical consequences for patients and physiotherapists, including aspects of exploitation by employers. Participants reported quitting work in specific facilities or having thoughts about leaving the profession because of an incompatibility of workplace or system processes with their own values:

(…) we have to rehabilitate more patients with less workers, but it is for our own future and that they can keep us, thats what they tell us, but its only all about the money and not the patient anymore, and thats really sad and makes me almost not wanna work anymore in medical section, thinking about doing somethin else (…) really disappointing, in a first world country. (Participant 115, ER)

Theme 4. Political threats

Some participants reported receiving threats, which reflected the political reality of their countries:

(In my native country) Cases of surveillance when treating one or two victims of possible political violence/government brutality and there was always the possibility that there could be electronic bugging. (Participant 230, AR)

Other examples of threats in the data were expressions of a suppressive professional-political environment. This included participants reporting being faced with the choice of either following the hierarchy’s direction or not progressing their careers. One response described the removal and demotion of a physiotherapist who presented challenging information regarding research in an educational setting, which questioned the reliability of a common physiotherapy assembly (#107, NACR). Some professional organizations and leaders were reported to be intimidating members into compliance and silencing dissent. There was a reported example of a doctor warning therapists after they made a critical incident report. In another example, the participant experienced a societal atmosphere of mistrust underlying the patient’s defensive stance toward the physiotherapist:

Patients who are not willing to answer the subjective assessment questions saying but the Doctor gave you referral just read there. At one point, one man wanted to hit one of the therapists i work with saying, why you asking all these questions are you a policewoman.” (Participant 290, AR)

DISCUSSION

The result of the open question analysis was a spectrum of contextually based ethical issues ranging from various expressions of the survey items 14–59 to new perspectives on the survey’s original list of ethical situations to entirely different ethical issues. There was a concentration on three types of ethical situations listed in Section 2: “Physiotherapist aware of misconduct by other health professionals including other health professionals” (question 37); “Bullying or harassment of physiotherapist” (question 34); and “Conflict with another health professional about patient’s management” (question 41). We identified 22 ethical situations that raised new issues that were not asked in the original Section 2 survey questions, described by the following four themes: lack of regulatory and/or accreditation policy and infrastructure, lack of recognition of the role and position of physiotherapists in healthcare, economic factors driving the conduct of practice, and political threats. The optional opportunity of sharing lived (un)ethical experiences at the survey’s end allowed the participants to actively contribute situated ethics knowledge beyond the predefined list of 46 commonly shared ethical situations in the ethics literature of physiotherapy.

We identified the realm of physiotherapists’ everyday ethical challenges as existing in colorful shades beyond a dichotomous attribution of being “good” for complying with a code of ethics or “bad” if not. Physiotherapists may be more or less autonomous practitioners, but they are not islands. Their professional practice and experiences of ethical situations occur in diverse contexts, which are, in turn, related to and situated in particular sociocultural systems. These findings reveal that many of the injunctions contained in codes of ethics can become almost impossible for practitioners to comply with in the contexts and pressures of workplaces and societies in which they practice. The ethics literature in physiotherapy has not, until this study, demonstrated any significant acknowledgment of this severe challenge to ethical physiotherapy practice in international contexts.

The primacy of making profit or cost efficiency in conflict with patient care drives much of this and leads to pressure on physiotherapists to violate rules, laws, and obligations and an erosion of professional values (Baru and Mohan, Citation2018; Komesaroff, Kerridge, Carney, and Brooks, Citation2013). Furthermore, there are physiotherapists who are attempting to practice in contexts where there are poor levels of practice regulation (Mamin and Hayes, Citation2018; Souri, Nodehi Moghadam, and Mohammadi Shahbolaghi, Citation2020), little or nonexistent levels of practitioner/training accreditation, and poor recognition of physiotherapy knowledge and contribution to health care (Chigbo, Ezeome, Onyeka, and Amah, Citation2015; Mamin and Hayes, Citation2018), which makes it hard for them to find orientation, guidance, and acknowledgment.

According to Bell and Breslin (Citation2008), the factors of cost pressure and inadequate staffing, lack of institutional policies to ensure an appropriate guidance of health professionals’ actions, ineffective communication between healthcare staff, and patient family members all contribute to high moral distress and to leaving the profession (Cantu, Citation2019). Additionally, hierarchical structures may limit the ability to be assertive (Bell and Breslin, Citation2008). In such (un)ethical situations, physiotherapists may not perceive themselves as independent moral agents and autonomous practitioners because bureaucracies or planners, managers, and administrators influence the terms of their work (Jones, Citation1991; Sandstrom, Citation2007). Therefore, we should not overestimate the capacity for individual personal control by physiotherapists within the complex ethical landscapes in healthcare. This is supported by identification in the broader literature that organizational factors can contribute to a distortion of the ethical intentions of individuals (Jones, Citation1991) and to the degree to which a moral agent is able to act independently upon deliberated values (Watson, Freeman, and Parmar, Citation2008).

A code of ethics as an expression of a social contract should protect health care-receiving communities by ensuring accountability and trustworthiness (Swisher and Hiller, Citation2010), with a focus of attention on the patient (Hoffmann and Nortjé, Citation2015; Sandstrom, Citation2007). In this study, depending on contextual circumstances, even the existential vulnerability of physiotherapists becomes visible. Not only do the patient and society need protection, as part of the social contract expressed in a code of conduct, but also physiotherapists.

The new themes identified by our open question analysis have limited representation in broader reporting of ethical practice in the health professions, supporting the novel findings of this study. The ethical issue of “economic factors driving the conduct of practice” has been identified in other professional areas, such as the “pressure of productivity measures” influencing the quality of care in occupational therapy (Bushby et al., Citation2015), the effects of “privatization” on the practice of Saudi Arabia’s health professionals (Alkabba et al., Citation2012), and private healthcare clinics refusing to provide care for more expensive and complicated conditions in Gabon (Sippel, Marckmann, Ndzie Atangana, and Strech, Citation2015). The lack of recognition of a profession’s role by another professional has been reflected in a review of international nursing practice as power struggles between nurses and doctors limit the authority of nurses in care decision-making (Rainer, Schneider, and Lorenz, Citation2018) and as international occupational therapists perceive their professional identity being misunderstood, unappreciated, and undervalued by other health professionals and the public (Guru, Siddiqui, and Rehman, Citation2013; Turner and Knight, Citation2015). The political influence on healthcare institutions and practice has been identified as an ethical issue in the African Nation of Gabon where health professionals perceive that they have little agency to improve the ethical situation due to such politics. The threat of political violence against health professionals has also been recognized in a recent strategy by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to “Protecting health care from violence and attacks in situations of armed conflict and other emergencies” (International Committee of the Red Cross, Citation2020), in part prompted by the killing of ICRC workers in 2017 including a physiotherapist (International Committee of the Red Cross, Citation2017). “Role blurring” between occupational therapists, nurses, and physiotherapists due to a lack of specific professional boundaries, rules, and regulations has been reported for India (Guru, Siddiqui, and Rehman, Citation2013), mirroring the finding of a lack of regulatory and/or accreditation policy and infrastructure. The scarce reporting of these themes in the health professional literature recommends that there is more to know about sociocultural and political influences on ethical practice of health professionals to understand if these are newly emerging issues or have been perhaps “hidden” within other reported issues, and how they can be addressed.

In facing the many ethical issues encountered in clinical practice, physiotherapists have the right to be equipped and supported in their everyday practice and to not contemplate the alternative of leaving the profession due to factors such as burnout. In order to nurture and sustain the global diversity of the physiotherapy profession, we need more locally informed and situated ethics research. This is best conducted by colleagues with roots in specific contexts that give rise to the ethical issues that they investigate. Such research can further inform the wider physiotherapy community as to what difficulties that physiotherapists around the globe face, thereby creating a better foundation for the kinds of support in particular areas that physiotherapists and their associations require. This is an important step in further learning how physiotherapists can be assisted to become moral agents in their own contexts (Carpenter, Citation2010; Edwards, Delany, Townsend, and Swisher, Citation2011).

Embedding context into ethics teaching and codes can help to prepare (future) physiotherapists for the complexity, ambiguity, and sometimes “messiness” of the ethical situations that they will encounter in their (later) practice and lead to better alignment with a code of ethics with local requirements (Bates et al., Citation2019). Contextual variations of national physiotherapy associations’ codes of ethics can celebrate the diversity of the profession and countries in which physiotherapists practice and support physiotherapists to respond to the affordances of their local social landscapes (Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand, Citation2020; South African Society of Physiotherapy, Citation2017). To be capable of successfully resolving ethical conflicts, codes could be supplemented with practically related and contextually sensitive guidance notes (Burke, Harper, Rudnick, and Kruger, Citation2007) or a guide that helps practitioners to interpret a code of conduct (American Physical Therapy Association, Citation2010). Specific skill training could help students to be practitioners who remain true to their own values and be resilient even if their professional principles are infringed. But individual-based resilience training will not erase the conditions that are contributing to their moral distress. If an organization’s ethical values subvert the employee’s personal values, the likelihood that they will choose to leave the organization is high (Burchard, Citation2011). We must be careful about simply handing over the responsibility for remaining healthy and upright to individuals within broken or misguided systems.

Ferrari, Manotti, Balestrino, and Fabi (Citation2018) emphasized that planners, managers, and administration have an ethical responsibility toward healthcare organizations and health professionals to ensure a maximum level of safety and as part of the social contract to protect the single or collective good, by appropriate allocation and use of public resources. The enculturation of a constructive ethical climate is suggested by Bell and Breslin (Citation2008) to increase job satisfaction and retain health professionals and will enhance team efficacy and learning behavior (Kim, Lee, and Connerton, Citation2020). Also, policy makers and professional and political leaders are in positions to act for a change, by shaping healthcare systems and societies to become more just, collaborative, humane, esteemed, and protective (Benatar, Citation2016; Schuklenk, Citation2020; World Health Professions Alliance, Citation2019). Ongoing violations of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation2015) around the globe, either for political or religious reasons, underscore the undeniable value and necessity of overarching, jointly held ethical principles for a profession.

In this paper, we have demonstrated the overwhelming influence of “context” on the perception and experience of ethical issues in diverse physiotherapy communities. Just as there is a “universality” to evidence in clinical practice, there is a recognition that such evidence will need to be applied in context in various places. For example, consider the use of appropriate and local technologies in rehabilitation in different places – universal aims of treatment but with local solutions and methods. So, ethics also has a universality and an accompanying set of ethical concerns, which the physiotherapy profession shares internationally. However, the lived experience of ethical issues has its own expression in different places. It is our contention that support needs to be extended to our international colleagues to assist them to bridge, via research and education, the difficult gulf between what is universal in ethical practice and what is local.

Strengths and limitations

Some of the literature underpinning our original survey questions dates back to a period when ethics was characterized as the individual practitioner’s compliance with a professional code of ethics and when social and societal perspectives on determining factors of health and health systems were limited (Purtilo, Citation2000). Our bottom-up approach in question 60 to offer physiotherapists an opportunity to share their professional daily experiences strove to mitigate this limitation. The English language of the survey might have excluded interested participants in some regions and could be accounted for the lower numbers of participants from South America, but could have facilitated access to the survey in others (i.e. participation from African or Asian countries with a history of British colonization like Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, India, or Pakistan, which was higher than that in other African or Asian countries). There was a risk that participants who spoke English as a second or third language might interpret the survey question differently than intended. Therefore, we recommended using a dictionary in the survey introduction in the case of uncertainty, as this was reported back as being supportive by some non-English first language speakers in our pilot study. Furthermore, we had to exclude some responses (coded as teal) through a lack of detail because the survey design did not allow us to ask supplementary questions to seek clarification or explore individual experiences as possible in different qualitative study designs.

Conclusions

In this study, we described contextual shades of ethical situations, experienced by physiotherapists internationally. The sampling of physiotherapists and physiotherapy students from all World Physiotherapy regions allowed us to bear witness to many unheard voices of physiotherapists and their multifarious experiences in both, the scope of ethical situations, and a variety of individual themes. The findings implicate that the ethical actions taken (or not) by physiotherapists, as both healthcare practitioners and moral agents, must be judged and supported on the basis of an understanding of an individuals’ situation. Further work could elaborate what factors and pressures influence physiotherapists internationally in their daily ethical practice to inform guides and ethics education. Moreover, our findings highlight the relevance of cross-cultural research in the field of physiotherapy, and the necessity of investigating and bridging the gap between professional ethics theory and practice in diverse settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank our study participants for contributing their time and experiences, the physiotherapists from Australia and Europe who were piloting the survey, Dr Stefan Dinges from the Institute of Right and Ethics in Medicine at the University of Vienna, and the Department for Culture and Science of the Salzburg Government (Land Salzburg), Austria.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alkabba AF, Hussein GMA, Albar AA, Bahnassy AA, Qadi M 2012 The major medical ethical challenges facing the public and healthcare providers in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family and Community Medicine 19(1): 1–6. 10.4103/2230-8229.94003

- American Physical Therapy Association 2010 APTA guide for professional conduct. American Physical Therapy Association, Alexandria, United States of America. https://www.apta.org/your-practice/ethics-and-professionalism/apta-guide-for-professional-conduct

- Angus, T 2003 Animals & ethics: An overview of the philosophical debate. Peterborough, Canada: Broadview Press.

- Baldwin KM 2010 Moral distress and ethical decision making. Nursing Made Incredibly Easy! 8(6): 5. 10.1097/01.NME.0000388524.64122.41

- Baru RV, Mohan M 2018 Globalisation and neoliberalism as structural drivers of health inequities. Health Research Policy and Systems 16(Suppl S1): 91. 10.1186/s12961-018-0365-2

- Bates J, Schrewe B, Ellaway RH, Teunissen PW, Watling C 2019 Embracing standardisation and contextualisation in medical education. Medical Education 53(1): 15–24. 10.1111/medu.13740

- Beauchamp TL, Childress JF 2019 Principles of biomedical ethics (8th ed). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bell J, Breslin JM 2008 Healthcare provider moral distress as a leadership challenge. JONA’s Healthcare Law, Ethics, and Regulation 10(4): 94–99. 10.1097/NHL.0b013e31818ede46

- Benatar S 2016 Politics, power, poverty and global health: Systems and frames. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 5(10): 599–604. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.101

- Burchard MJ 2011 Ethical dissonance and response to destructive leadership: A proposed model. Emerging Leadership Journeys 4: 154–176.

- Burgess T, Jelsma J 2018 The ethics of care as applied to physiotherapy training and practice – A South African perspective. In: Nortjé N, De Jongh JC, Hoffmann WA (Eds) African perspectives on ethics for healthcare professionals. Advancing global bioethics, pp. 147–157. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Burke A, Harper M, Rudnick H, Kruger G 2007 Moving beyond statutory ethical codes: Practitioner ethics as a contextual, character-based enterprise. South African Journal of Psychology 37(1): 107–120. 10.1177/008124630703700108

- Bushby K, Chan J, Druif S, Ho K, Kinsella EA 2015 Ethical tensions in occupational therapy practice: A scoping review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 78(4): 212–221. 10.1177/0308022614564770

- Cantu R 2019 Physical therapists‘ ethical dilemmas in treatment, coding, and billing for rehabilitation services in skilled nursing facilities: A mixed-method pilot study. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association 20(11): 1458–1461. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.06.013

- Carpenter C 2010 Moral distress in physical therapy practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 26(2): 69–78. 10.3109/09593980903387878

- Carpenter C, Richardson B 2008 Ethics knowledge in physical therapy: A narrative review of the literature since 2000. Physical Therapy Reviews 13(5): 366–374. 10.1179/174328808X356393

- Cherkowski SL, Walker KD, Kutsyuruba B 2015 Principals’ moral agency and ethical decision-making: Toward a transformational ethics. International Journal of Education Policy and Leadership 10: 5.

- Chigbo NN, Ezeome ER, Onyeka TC, Amah CC 2015 Ethics of physiotherapy practice in terminally ill patients in a developing country, Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 18: 40–45.

- Chileshe KM, Munalula-Nkandu E, Shula H, Nkhata LA, Simpamba M 2016 Identification of ethical issues encountered by physiotherapy practitioners in managing patients with low back pain at two major hospitals in Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of Preventive and Rehabilitative Medicine 1: 74–81.

- Delany CM, Edwards I, Fryer CE 2019 How physiotherapists perceive, interpret, and respond to the ethical dimensions of practice: A qualitative study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 35: 663–676.

- Delany CM, Edwards I, Jensen GM, Skinner E 2010 Closing the gap between ethics knowledge and practice through active engagement: An applied model of physical therapy ethics. Physical Therapy 90: 1068–1078.

- Edwards I, Delany CM, Townsend AF, Swisher LL 2011 Moral agency as enacted justice: A clinical and ethical decision-making framework for responding to health inequities and social injustice. Physical Therapy 91: 1653–1663.

- Edwards I, Wickford J, Adel AA, Thoren J 2011 Living a moral professional life amidst uncertainty: Ethics for an Afghan physical therapy curriculum. Advances in Physiotherapy 13: 26–33.

- Ferrari A, Manotti P, Balestrino A, Fabi M 2018 The ethics of organizational change in healthcare. Acta Biomedica 89: 27–30.

- Figueiredo LC, Gratão AC, Fachin-Martins E 2016 Has the new code of ethics for physio-therapists incorporated bioethical trends? Revista Bioética 24: 315–321.

- Fryer CE, Sturm A, Roth R, Edwards I 2021 Scarcity of resources and inequity in access are most frequently reported ethical issues for physiotherapists internationally: An observational study. BMC Medical Ethics 22: 97.

- Gillen E 2003 Ethik und Autonomie [Ethics and Autonomy]: Wissenschaftliches Symposium an der Katholischen Fachhochschule Freiburg 2002. Münster: LIT Verlag.

- Griech SF, Vu VD, Davenport TE 2020 Toward an ethics of societal transformation: Re-imagining the American physical therapy code of ethics for 21st Century. Physical Therapy Journal of Policy, Administration and Leadership 20: 13–21.

- Guru R, Siddiqui M, Rehman A 2013 Professional identity (role blurring) of occupational therapy in community mental health in India. Isra Medical Journal 5: 155–159.

- Haraway D 1988 Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies 14: 575–599.

- Hoffmann WA, Nortjé N 2015 Ethical misconduct by registered physiotherapists in South Africa (2007–2013): A mixed methods approach. South African Journal of Physiotherapy 71: 248.

- International Committee of the Red Cross 2017 Afghanistan: Physiotherapist who helps amputee patients shot and Killed. Geneva, Switzerland: ICRC. https://www.icrc.org/en/document/Afghanistan-physiotherapist-who-helps-amputee-patients-shot-and-killed

- International Committee of the Red Cross 2020 Institutional health care in danger strategy 2020–2022 Protecting health care from violence and attacks in situations of armed conflict and other emergencies. Geneva, Switzerland: ICRC. https://healthcareindanger.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/ICRC-HCiD-strategy-2020-2022.pdf

- International Council of Nurses 2012 The ICN code of ethics for nurses. Geneva, Switzerland: International Council of Nurses. https://www.icn.ch/sites/default/files/inline-files/2012_ICN_Codeofethicsfornurses_%20eng.pdf

- International Union of Psychological Science 2008 Universal declaration of ethical principles for psychologists. International Union of Psychological Science, Montreal, Canada. https://www.iupsys.net/about/governance/universal-declaration-of-ethical-principles-for-psychologists.html.

- Jones TM 1991 Ethical decision making by individuals in organizations: An issue-contingent model. Academy of Management Review 16: 366–395.

- Kim S, Lee H, Connerton TP 2020 How psychological safety affects team performance: Mediating role of efficacy and learning behavior Frontiers in Psychology. 11: 1581.

- Komesaroff P, Kerridge I, Carney S, Brooks P 2013 Is it too late to turn back the clock on managerialism and neoliberalism? Internal Medicine Journal 43: 221–222.

- Kulju K, Suhonen R, Puukka P, Tolvanen A, Leino-Kilpi H 2020 Self-evaluated ethical competence of a practicing physiotherapist: A national study in Finland. BMC Medical Ethics 21: 43.

- Ladeira TL, Koifman L 2017 The interface between physical therapy, bioethics and education: An integrative review. Revista Bioética 25: 618–629.

- Mamin F, Hayes R 2018 Physiotherapy in Bangladesh: Inequality begets inequality. Frontiers in Public Health 6: 80.

- Nyante G, Andoh C, Bello A 2020 Patterns of ethical issues and decision-making challenges in clinical practice among Ghanaian physiotherapists. Ghana Medical Journal 54: 179–185.

- Oyeyemi A 2012 Ethics and contextual framework for professional behaviour and code of practice for physiotherapists in Nigeria. Journal of Nigeria Society of Physiotherapy 18: 49–53.

- Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand 2020 Aotearoa New Zealand physiotherapy 2011 code of ethics and professional conduct with commentary. Wellington, New Zealand: Physiotherapy Board of New Zealand. https://www.physioboard.org.nz/sites/default/files/NZ_Physiotherapy_Code_of_Ethics_with_commentary_FINAL_0.pdf

- Purtilo RB 2000 A time to harvest, a time to sow: Ethics for a shifting landscape. Physical Therapy 80: 1112–1119.

- Rainer J, Schneider K, Lorenz RA 2018 Ethical dilemmas in nursing: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27: 3446–3461.

- Sandelowski M 2010 What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing and Health 33: 77–84.

- Sandstrom RW 2007 The meanings of autonomy for physical therapy. Physical Therapy 87: 98–106.

- Schuklenk U 2020 What healthcare professionals owe us: Why their duty to treat during a pandemic is contingent on personal protective equipment (PPE). Journal of Medical Ethics 46: 432–435.

- Sippel D, Marckmann G, Ndzie Atangana E, Strech D 2015 Clinical ethics in Gabon: The spectrum of clinical ethical issues based on findings from in-depth interviews at three public hospitals. PLoS One 10: e0132374.

- Souri N, Nodehi Moghadam A, Mohammadi Shahbolaghi F 2020 Iranian physiotherapists’ perceptions of the ethical issues in everyday practice. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 18: 125–136.

- South African Society of Physiotherapy 2017 Code of Conduct. Germiston, South Africa: South African Society of Physiotherapy. https://www.saphysio.co.za/media/1115/policy-code-of-conduct-of-sasp-rev-3-may-2017.pdf

- Swisher LL 2002 A retrospective analysis of ethics knowledge in physical therapy (1970–2000). Physical Therapy 82: 692–706.

- Swisher LL, Arslanian LE, Davis CM 2005 The realm-individual process-situation (RIPS) model of ethical decision-making. HPA Resource 5(3): 1–8.

- Swisher LL, Hiller P 2010 The revised APTA code of ethics for the physical therapist and standards of ethical conduct for the physical therapist assistant: Theory, purpose, process, and significance. Physical Therapy 90: 803–824.

- Turner A, Knight J 2015 A debate on the professional identity of occupational therapists. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 78: 664–673.

- United Nations 2015 Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

- Watson GW, Freeman RE, Parmar B 2008 Connected moral agency in organizational ethics. Journal of Business Ethics 81: 323–341.

- World Confederation for Physical Therapy 2001 WCPT: The first 50 years. World Physiotherapy, London, United Kingdom. http://world.physio/resources/publications.

- World Confederation for Physical Therapy 2011 WCPT: Six decades of moving the profession forward. World Physiotherapy, London, United Kingdom. http://world.physio/resources/publications.

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists 2016 Position statement: Ethics, sustainability and global experiences. WFOT, London, United Kingdom. https://wfot.org/resources/ethics-sustainability-and-global-experiences.

- World Health Professions Alliance 2019 Stand up for positive practice environments. World Health Professions Alliance, Geneva, Switzerland. https://www.whpa.org/activities/positive-practice-environments.

- World Medical Association 2006 International code of medical ethics. World Medical Association, Ferney-Voltaire, France. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-international-code-of-medical-ethics/.

- World Physiotherapy 2019a Policy statement: Ethical principles. World Physiotherapy, London, United Kingdom. http://world.physio/policy/policy-statement-ethical-principles.

- World Physiotherapy 2019b Policy statement: Ethical responsibilities of physical therapists and member organizations. World Physiotherapy, London, United Kingdom. http://world.physio/policy/ps-ethical-responsibilities.

- World Physiotherapy 2020a World physiotherapy membership votes to admit three new member organizations. World Physiotherapy, London, United Kingdom. https://world.physio/news/world-physiotherapy-membership-votes-admit-three-new-member-organisations.

- World Physiotherapy 2020b Our regions. World Physiotherapy, London, United Kingdom. https://world.physio/regions.

- World Physiotherapy 2021 Profile of the global profession. World Physiotherapy, London, United Kingdom. https://world.physio/membership/profession-profile.