ABSTRACT

(a) Background

Home-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is an attractive alternative for frail older patients who are unable to participate in hospital-based CR. Yet, the feasibility of home-based CR provided by primary care physiotherapists (PTs) to these patients remains uncertain.

(b) Objective

To investigate physiotherapists’ (PTs) clinical experience with a guideline-centered, home-based CR protocol for frail older patients.

(c) Methods

A qualitative study examined the home-based CR protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Observations and interviews of the CR-trained primary care PTs providing home-based CR were conducted until data saturation. Two researchers separately coded the findings according to the theoretical framework of Gurses.

(d) Results

The enrolled PTs (n = 8) had a median age of 45 years (IQR 27–57), and a median work experience of 20 years (IQR 5–33). Three principal themes were identified that influence protocol-adherence by PTs and the feasibility of protocol-implementation: 1) feasibility of exercise testing and the exercise program; 2) patients’ motivation and PTs’ motivational techniques; and 3) interdisciplinary collaboration with other healthcare providers in monitoring patients’ risks.

(e) Conclusion

Home-based CR for frail patients seems feasible for PTs. Recommendations on the optimal intensity, use of home-based exercise tests and measurement tools, and interventions to optimize self-regulation are needed to facilitate home-based CR.

Introduction

Comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is recommended for older patients who experienced a hospital-admission for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (Achttien et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; Rohrbach et al., Citation2017). Likewise, the benefits of CR in frail older populations have been researched and documented (Afilalo, Citation2019; Doll et al., Citation2015; Shields et al., Citation2018; Taylor et al., Citation2015). Frailty may be defined as a syndrome of physiological decline characterized by marked vulnerability to adverse health outcomes such as hospital readmission and mortality (Buurman et al., Citation2012; Krumholz et al., Citation2013). Consequently, providing CR for the frail older patient with CVD is met with distinctive challenges (Doll et al., Citation2015; Shields et al., Citation2018), like low participation rates (i.e. 20–30%) in hospital-based CR because of a lack of transportation facilities, the patient’s perception about the worth of the rehabilitation program, and their apprehensions regarding the risks of exercising (Ruano-Ravina et al., Citation2016).

To mitigate these reservations, home-based CR is gradually becoming a good alternative to hospital-based CR to effectively improve the physical functioning of low-to-moderate risk (non-frail) patients (Taylor et al., Citation2015; Verweij et al., Citation2019). Yet, the feasibility of a home-based CR program for frail older patients from a primary care physiotherapist’s perspective is uncertain. The current CR guidelines for physiotherapists (PTs) are largely based on research involving non-frail patients, not adjusted to the home situation, and there is a lack of specific recommendations for modifying CR in the presence of frailty and comorbidities (Achttien et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; Dekker, Buurman, and van der Leeden M, Citation2019; Piepoli et al., Citation2014; van Weel and Schellevis, Citation2006; Vigorito et al., Citation2017). Consequently, physiotherapists may be reluctant to prescribe exercise therapy, resulting in less adequate treatment. Therefore, the current study aimed to investigate physiotherapists’ clinical experiences in light of the present guidelines for CR and the home-based CR protocols that are followed for frail older patients.

Methods

Study design

The conduct of this qualitative study involved observing primary care PTs who performed home-based CR for frail older patients, followed by semi-structured personal face-to-face interviews. The home-based CR component was a part of a larger randomized trial, the “Cardiac Care Bridge (CCB)” (Jepma et al., Citation2021b; Verweij et al., Citation2018) in collaboration with one teaching hospital and five other regional hospitals in and around Amsterdam. The study was registered with Netherlands Trial Register 6316, https://www.trialregister.nl/trial/6169. The Medical Ethical Review Board of the Amsterdam University Medical Center approved the study protocol for the CCB (MEC2016_024). All participants provided written informed consent before participating. This manuscript follows the COREQ checklist for reporting qualitative research (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig, Citation2007).

Home-based CR in the CCB intervention

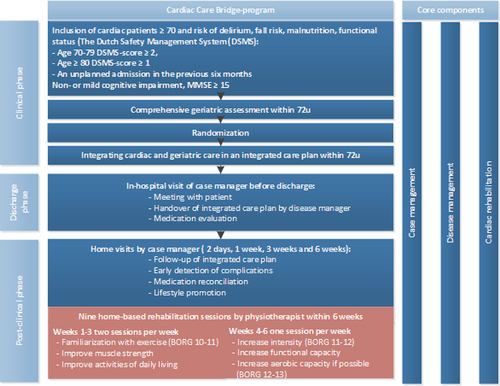

The CCB trial, conducted from June 2017 to March 2020, evaluated the effects of a transitional care program to prevent hospital readmission and mortality in frail, older patients with CVD (). The detailed study design and outcomes of the CCB study have been described in a previously published report (Jepma et al., Citation2021b; Verweij et al., Citation2018). Briefly, the CCB program is an integrated transitional-care program from the hospital to the patients’ home and is composed of three components: 1) case management; 2) disease management; and 3) home-based PT-led CR. Component 1 consisted of an in-patient comprehensive geriatric assessment-based integrated care plan implemented during the hospital stay and followed-up at home. In component 2, cardiac and community nurses coordinated with an affiliated pharmacist to carry out medication-checks, monitor medical parameters, and administer lifestyle coaching. In the last component, the PTs focused on facilitating participation in activities of daily living, performing regular exercises, monitoring weight, heart rate, and blood pressure, besides educating the patient striving for an active lifestyle.

Figure 1. Overview of the CCB program including home-based cardiac rehabilitation.

The CCB-integrated-home-based-CR protocol was based on the Dutch cardiac rehabilitation guidelines for PTs (Achttien et al., Citation2011, Citation2013, Citation2015) and was adapted for the CCB by two skilled PTs with more than 5 years of experience in the field of cardiopulmonary rehabilitation. The principal modifications done to the CR-guidelines include a substitution of regular exercise field tests, namely the shuttle walk test (Singh et al., Citation1992) or six-minute walk test (Bellet, Adams, and Morris, Citation2012; Butland et al., Citation1982) and the 6–10 repetition maximum strength test, which require sufficient floor space or strength testing equipment, with a home-executable version as a two-minute step test (Bohannon and Crouch, Citation2019; Rikli and Jones, Citation1999) and the 30-second chair-stand test (Jones, Rikli, and Beam, Citation1999), respectively. The two-minute step test requires patients to march in place, raising their knees to a height halfway between the patients’ iliac crest and patella, and has proven to have good validity and reliability for the assessment of exercise capacity in older patients (Bohannon and Crouch, Citation2019; Rikli and Jones, Citation1999). For the chair-stand test, the times that a patient comes to a full stand within 30 seconds are counted, when rising from a chair with their arms crossed in front of their chest. Research has shown good reliability and validity for the assessment of strength in older patients (Jones, Rikli, and Beam, Citation1999). Further modifications entailed elaborate directions for increasing exercise intensity and volume (Appendix A) and physical activity in old patients with CVD; specific instructions on when and how to communicate and collaborate with the community nurse; and how to act in the case of an emergency in the home setup. The CCB-CR protocol also consisted of recommendations for goal setting, exercise intensity, and exercise forms tailored for these patients (). Following discharge from the hospital, the first 3 weeks of home-based CR had 2 sessions/week which focused on familiarization with exercise at Borg RPE (Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion) of 10–11 points (Noble et al., Citation1983), and gain in muscle strength and increasing participation in activities of daily living (ADL) as indicated by an increase from 250 metabolic equivalents (METs) in the first week to 350 METs by week-3. In the following weeks, week 4–6, the prescribed sessions were once-a-week, ADL performance was further increased by 50 METs/week to achieve 500 METs by week-6, and exercise intensity was raised to Borg-RPE 12–13 indicating improved functional capacity, and if possible, the aerobic capacity.

Patient population

Patients aging ≥ 70 years falling in the high-risk category of functional loss measured by the Dutch Safety Management System (DSMS) screening instrument (Appendix B) and admitted for more than 48 hours to the cardiology or cardiac surgery departments of the participating hospitals, were eligible for participation in the CCB study. The DSMS screens for four geriatric conditions: 1) limitation in Activities of Daily Living (ADL); 2) falls; 3) malnutrition; and 4) the risk of delirium. Patients are considered at high risk of functional decline if they are 70–79 years old with ≥ 2 geriatric conditions, or aged ≥ 80 years with ≥ 1 geriatric condition (Heim et al., Citation2015). The exclusion criteria followed were: failure to provide informed consent and follow instructions owing to severe cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination, MMSE < 15); known case of congenital heart disease; a life expectancy of ≤ 3 months; those transferring to another hospital or nursing home; and unable to communicate in the Dutch language. The CCB-research nurses collected baseline data for patients during their hospital admission (Verweij et al., Citation2018).

Physiotherapists

PTs enrolled in the CCB study were either members of a local PT network ‘LoRNA, affiliated with homecare organizations or were experienced in the field of rehabilitation for CVDs along with the relevant educational qualification necessary to provide CR. Additionally, they had at least one year of experience with home-based care and treatment for old patients with comorbidities. These PTs received five additional training sessions on cardiac disease and frailty, and on the CR protocol followed in the CCB study. The training sessions covered the following items: 1) pathology of congestive heart failure; 2) adaptations of exercise frequency, intensity, time, and type (FITT-factors) according to comorbidity and frailty; polypharmacy; motivational interviewing; when and how to collaborate with CCB community nurses; and practical application of the study protocol (Verweij et al., Citation2018). The PTs in the CCB study were then approached for the current qualitative study after they had completed the provision of the home-based CR program for at least one patient.

Data collection and measurements

The process of data collection consisted of observations and interviews performed by MT, a PT researcher with experience in CR and trained in performing qualitative research. The observations and interviews were structured according to the Gurses et al. (Citation2010) framework (Appendix C) on compliance to evidence-based guidelines.

The observations regarding PTs’ adherence/non-adherence to the CCB-CR protocol and identifying the potential barriers and facilitators were executed in weeks 2–5 of the treatment period. MT recorded patient’s characteristics (e.g. present comorbidity, motivation), provider’s characteristics (e.g. displayed habits), and the system characteristics (e.g. serviceability of the patient registry, used exercise materials, and measurement instruments) on the observation form (Appendix D).

Following an observation, MT interviewed the PT about their experiences regarding the feasibility of the home-based CCB-CR protocol and perceived barriers and facilitators. Similar to the observation-phase, demographic characteristics (i.e. age, gender, work experience, and education) for all PTs were recorded. The interview topics (Appendix E) based on Gurses’ framework were: 1) provider characteristics (e.g. knowledge of the content of the CCB-CR protocol); 2) guideline characteristics (e.g. compatibility of the CCB-CR protocol with daily practice, experienced complexity of the protocol); 3) system characteristics (e.g. experienced workload and work environment); and 4) implementation characteristics (e.g. involvement of their organization’s management) (Gurses et al., Citation2010). Each interview lasted approximately 45 minutes and all proceedings were audio-recorded and transcribed ad verbum. Our sample size was based on when data saturation (i.e. when the same information is repeated) was reached (Malterud, Siersma, and Guassora, Citation2016).

Data analysis

First, two researchers (MT and LV) independently coded (coding category based on Gurses’ framework, Appendix C) the extended field notes of the observations and “ad verbum” transcriptions of the interviews in Max-QDA 12 (Gurses et al., Citation2010). Subsequently, axial and selective coding was used to compare categories and identify the central themes related to the feasibility of the CCB-CR protocol (Corbin and Strauss, Citation2008). The examiners added newly-identified categories to the observation and interview forms after each analysis, wherever applicable. Disagreements between the two researchers regarding the coding categories were settled by discussion. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation SD, median and interquartile range IQR or percentages and range) for the baseline participant and patient characteristics were computed and tabulated.

Results

Study population

Data saturation was reached after the sixth and confirmed in the seventh and eighth observation and interview. The eight observed and interviewed PTs (median age 45 years, IQR 27–57) had a median work experience of 20 years (IQR 5–33) (). Four PTs were skilled in CR and seven had practiced geriatric care. All eight PTs had more than one year of experience in home-based treatment, and seven had previously worked in multidisciplinary teams. All PTs had treated at least one patient in the CCB before observations and interviews took place. The cumulative number of patients treated by the PTs at the time of observations was 21.

Table 1. Characteristics physiotherapists

The average age of patients in the observed treatment sessions was 81 ± 8.2 years, of which five were males (). The majority of the patients had at least two geriatric conditions out of: 1) limitations in Activities of Daily Living (ADL); 2) falls; 3) malnutrition, and 4) risk of delirium according to the DSMS screening. All patients were diagnosed with congestive heart failure and the cause for hospital admissions were decompensated congestive heart failure (n = 5), endocarditis (n = 1), angina pectoris (n = 1), and pacemaker implantation (n = 1). The following comorbidities were reported – diabetes mellitus (n = 4), peripheral arterial disease (n = 2), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 1), knee osteoarthritis (n = 1), stroke (n = 1), and renal failure (n = 2).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of the patients (n = 8) in the observed treatment sessions

Adherence and feasibility themes

summarizes the reasons reported by PTs for adherence or non-adherence to the CCB-CR protocol (Gurses et al., Citation2010). Mean intercoder agreement in the analyses of the combined observations and interviews was 94.5% (range 90.3–100%). Our analyses revealed three sets of themes that influenced the practicability of the protocol. The subsequent paragraphs elaborate on each theme structured according to the system, provider, guideline, implementation, and patient characteristics (Gurses et al., Citation2010). Briefly, the first theme encompasses the feasibility of exercise testing and the exercise program. The second theme covers the motivational aspects of home-based CR, consisting of both patient motivation or self-regulation and the use of motivational techniques by the PT. The third theme elucidates on the interdisciplinary-collaboration and task-division between the community nurse and other healthcare providers in monitoring the patients’ health status and risks of hospital readmission.

Table 3. Reasons for physiotherapists’ adherence or non-adherence to the CCB Cardiac Rehabilitation protocol

Theme 1: feasibility of exercise testing and the exercise program according the CCB-CR protocol

System characteristics

Most PTs reported that the most common barrier was the administration of exercise tests and the time consumed in taking repeated blood pressure measurements. It was further observed that availability of sufficient time facilitated the application of the Borg-RPE scale and METs table, supplemented with the availability of practical tools like dumbbells and mobile sitting bicycle and the PT’s experience in using the equipment, encouraged the PT to prescribe higher intensity exercises. As a facilitator to adhere to the CCB-CR protocol, some PTs reported a positive culture for change in the organization, (quote 1 (Q1)).

(Q1) “Their (the management’s) opinion is that you should improve yourself every time by following education or by any way possible. So, they create space to do this (e.g. for participation in the CCB intervention).” (PT C)

Provider characteristics

As facilitators for adherence to the CCB-CR protocol, most PTs reported an increase in the patients’ physical activity levels (Q2) resulted in a positive attitude and expectations of better outcomes from the home-based CR. All PTs reported a positive attitude about participating in research and displayed sufficient knowledge of the CCB-CR protocol during the observations.

(Q2) “Nine out of ten patients sit too much and that won’t help them. So, I am convinced that the intervention can prevent hospital readmissions.” (PT C)

All PTs adhered to the suggested exercise tests (i.e. two-minute step test and 30-second chair stand test) and described them as feasible for evaluating patients’ endurance and strength (Bohannon and Crouch, Citation2019; Jones, Rikli, and Beam, Citation1999). Most PTs did not frequently use the table with metabolic equivalents of tasks (METs), which was intended to provide insight into patients’ daily activities energy expenditure (Ainsworth et al., Citation2000). Additionally, most PTs reported a lack of knowledge on how to calculate METs and their non-applicability to frail patients and preferred the “patient-specific functioning scale” or the activity log (Cleland, Fritz, Whitman, and Palmer, Citation2006). Likewise, most PTs reported difficulty in applying the Borg-RPE scale of perceived exertion to estimate exercise intensity due to the patients’ limited ability to discriminate between the scale’s levels (Q3) (Noble et al., Citation1983).

(Q3) “With this lady, I didn’t even try to explain the BORG properly, because it just costs too much time and energy in contrast to what it yields. That is something you judge within two times when they indicate the same score.” (PT E)

It was observed that all PTs prescribed functional exercises (e.g. walking, climbing stairs) as recommended in the CCB-CR protocol. All PTs reported that their objective of home-based CR was not an improvement in cardiovascular fitness alone, but encouraging the patients to improve their physical functioning and self-management.

Guideline characteristics

All PTs reported that adherence to the CCB-CR protocol was facilitated by the simplicity of the protocol (Q4), except for the description of the METs. Some PTs also reported a need for more examples of home exercises.

(Q4) “Well, I think the protocol, which can be found in the CCB file online, is really quite clear. I mean considering its complexity. I don’t think it is very complex.” (PT D)

Patient characteristics

A reported barrier for exercise therapy was the presence of a psychiatric condition. To adapt the exercise therapy to the patient’s characteristics, most PTs indicated that they adjusted the following FITT-factors: 1) training intensity because congestive heart failure limited the patient’s exercise capacity; 2) exercise type and intensity because comorbidities limited the exercise possibilities (e.g. gout); and 3) timing, because exercise had to be postponed if kidney failure was present. For patients with higher activity goals PTs were able to prescribe aerobic training (e.g. walking or cycling > 5 minutes) in the last two weeks of the treatment period. For patients with lower activity goals, PTs deemed that aerobic training was not feasible. Exercise intensity could vary between training sessions and no PTs reported any adverse events in patients during or after the exercise sessions. The researcher did not observe and neither did any PT report any implementation characteristics related to this theme.

Theme 2: motivational aspects

Provider characteristics

All PTs spent time on motivating patients to increase daily activities and the patients’ self-regulation, as instructed in the CCB-CR protocol. PTs used goal setting to match the exercise needs of the patients, like exercising to walk independently to the mailbox. However, some PTs found it difficult to motivate sedentary patients, while it was easier if the patient was self-motivated to be independent in daily activities (Q5). All PTs had to balance the time spent on motivational interviewing and exercise. One PT prioritized patient-coaching over exercise therapy, while some PTs indicated a need for further training in motivational techniques that may be used in older patients with CVD.

(Q5) “No, because he is committed, because he really wants to. That is to say: his youngest son is handicapped. And he really wants to be able to independently take a cab to go to his son, and then be able to walk with his walking aid together with his son and go to a restaurant for a cup of coffee. And that is just not possible at this moment.” (PT D)

Further, PTs inspired self-management in patients by spreading CR-sessions over a longer period than the suggested six weeks, asking open-ended questions, and letting the patient formulate their own goals and concrete actions, such as restrictions of fluid intake in congestive heart failure (Q6).

(Q6) “How should we approach this? Do you want to do it yourself? Or with a dietician? Or do you want to use a fluid diary?” (PT F)

Patient characteristics

Some PTs indicated that it was harder to motivate patients for exercise or physical activity if the patient had a sedentary lifestyle or anxiety (Q7). They also reported that two patients had dropped out from physiotherapy because they found the number of care workers visiting them overwhelming.

(Q7) “No. I already did it this morning. I’m finished. I’m afraid to end up horizontally.”

No relevant system, guideline, or implementation characteristics for this theme were observed or reported during the PT interviews.

Theme 3: interdisciplinary collaboration in monitoring health status and risks of readmission

System characteristics

All therapists monitored blood pressure, heart rate, and weight. Some PTs reported that occasionally, the home-care nurses measured and reported the patients’ weight, allowing the PT or CCB-community nurse to focus on the interpretation of the measurement outcomes.

All PTs indicated that communication with other caregivers was facilitated through personal interactions (like from the training sessions or joint intake), and having collaboration-agreements with home care organizations. An often reported barrier for inter-professional communication was the absence of an institutional, secured communication system. All PTs preferred to communicate by telephone or e-mail if a situation was urgent, or through the documented patient-log, if less urgent.

Provider characteristics

All PTs said they were more aware of their responsibility in the interdisciplinary team to monitor patients’ health status by measuring blood pressure, heart rate, and weight, and reported three potential risk situations for hospital readmission, namely hypotension after medication changes, weight loss (i.e. risk of sarcopenia), and weight gain (i.e. potential decompensated congestive heart failure) (Q8). Most PTs said they were satisfied with their collaboration with the community and hospital nurses (Q9).

(Q8) “I had measured the blood pressure, which was quite low. And then it turned out that she had stopped with a medicine. She didn’t really know which one. Luckily, someone from homecare came along and found out which medicine it was.” (PT C)

(Q9) “Yes, I really appreciate that (meaning close collaboration with the nurse from the hospital). Because last week I called, because he had a low blood pressure, around 100 (systolic), so that is fine, but he was worried about it. I said: “Well, if it worries you. We discussed dizziness and other signs to monitor and how to respond when this happens ….” “Yes, but I do worry about it”. … I said: “Well, let’s call.” So, I called the hospital. I got her on the phone right away (meaning the cardiac nurse). She said the same as I did. And that, yes, that. He felt understood. And that was really satisfying.” (PT F)

Neither did the researcher observe, nor did the PTs report any guideline, implementation, or patient characteristics relevant to this Theme 3.

Discussion

The present study efficiently demonstrates that PTs find home-based cardiac rehabilitation (CR) to be feasible in frail older patients with CVD. Accordingly, no adverse events were reported. We identified three main issues that may be targeted for further improvements in home-based CR in these patients: 1) room for personalization of exercise testing and exercise intensity according to patients’ capabilities; 2) accounting for patients’ motivation and level of self-regulation when formulating activity goals; and 3) facilitating interdisciplinary communication in primary care. Through well-executed interviews, PTs reported experienced leadership as a facilitator and timing issues as an important barrier for the implementation of home-based CR. Our study is a first step toward offering frail older patients with CVD an alternative to traditional hospital-based CR, and the results may aid in developing a personalized, home-based CR program for this population.

We observed sufficient PT-reported CR-content acceptance and satisfactory levels of PT protocol adherence, ascertaining the feasibility of our home-based CR program. Based on our results and supported by the current literature, the guidelines for exercise prescription should, ideally, provide sufficient room for customization of exercise intensity and volume according to patients’ performance capabilities (O’Neill and Forman, Citation2019). This recommendation translates into CR-exercise protocols that suggest a range of exercises from low to high intensity, beginning with improving the patients’ muscle strength through functional training and practicing ADLs in the first three weeks of CR (e.g. chair rising for one frail patient and stair climbing for another) (Khadanga, Savage, and Ades, Citation2019; O’Neill and Forman, Citation2019; Tamuleviciute-Prasciene et al., Citation2018). For patients who can perform more than 5 minutes of exercise at > 3 METs, CR-exercise protocols can incorporate endurance-building exercises according to the patient’s activity goals. Although the 6MWT and incremental shuttle walk test are valid and reliable in clinically stable patients (Bellet, Adams, and Morris, Citation2012; Pepera, McAllister, and Sandercock, Citation2010) we chose to evaluate physical capacity within the patient’s home setup with the 2-minute step test, and the 30-second chair stand test, which were practical alternatives for the regular hospital-based cardiac exercise testing protocol (Jones, Rikli, and Beam, Citation1999; Rikli and Jones, Citation1999). Validity and reliability of these tests were demonstrated in various older patient populations, but our study is the first to demonstrate the feasibility in frail cardiac patients (Bohannon and Crouch, Citation2019). Minimal clinical important difference of these tests in frail patients should be further investigated. In addition, the present study’s findings suggest that a physical-activity log or METs table was less feasible in older patients with CVD. A more attractive alternative for the home situation can be the use of an activity tracker, which provides the patient an insight into their recovery process while encouraging them to become more active and engaged (Bostrom, Sweeney, Whiteson, and Dodson, Citation2020; Forman et al., Citation2014; Pol et al., Citation2019).

Our findings reaffirm the concept that the individual’s level of motivation for physical activity and self-regulation in undertaking and sustaining such activities should be considered when formulating activity goals for frail older patients (Nied and Franklin, Citation2002). Additional recommendations to communicate these goals to the target geriatric population, such as: tailored information about the risks and benefits of physical activity in this population (Bell and Saraf, Citation2014); motivational interviewing techniques (Schertz et al., Citation2019); and tools that support shared-decision-making (Backman, Levine, Wenger, and Harold, Citation2020), can potentially help in personalizing CR-protocols for frail older patients.

Finally, secured transmural interdisciplinary communication systems may aid primary care PTs in monitoring and exchanging health and risk information. Current communication systems and electronic patient records vary with organizations, forcing health professionals to fall back to less secure communication channels such as writing, faxing, e-mail, or telephone.

Our results are corroborated by systematic reviews and the American Heart Association’s guidelines, in which they reported that home-based CR was as effective and safe as center-based CR in patients with low-to-moderate risk (Doll et al., Citation2015; Taylor et al., Citation2015; Verweij et al., Citation2019). In addition, home-based CR has shown to be cost-effective, and improves QALY’s in patients with heart failure (Bakhshayesh et al., Citation2020). O’Neill and Forman (Citation2019) also reaffirmed the safety and effectiveness of CR in older patients. The results of our study ascertain that home-based CR is also feasible in very old (above 80 years) and frail populations and it is possible to organize home-based CR in primary-care PT practices in the Netherlands. Patients’ adherence and satisfaction to the CCB-intervention have been evaluated and published separately (Jepma et al., Citation2021a; Verweij et al., Citation2021).

Strengths and limitations

There are several strengths of the study. We used a qualitative design that combined observations with consecutive interviews, thereby obtaining a unique in-depth insight into how contextual variables and characteristics of frail older patients influence a PT’s professional practice (Jensen, Gwyer, and Shepard, Citation2000). This way we were able to evaluate the observed-adherence of PTs to the suggested CCB-CR protocol and identify points of improvement for improving the feasibility of home-based CR in frail older patients. Second, by separately coding all transcripts we reduced the risk of confirmation bias. The different professional backgrounds of the coders (nurse and PT) resulted in an inter-professional assessment of the relevant themes that influenced feasibility. After a consultation, the researchers attained an excellent intercoder agreement which supports the robustness of our study outcomes. Finally, the PT-sample varied in age, experience, and education, giving a realistic representation of Dutch primary care PTs. The review of Taylor et al. shows that PTs in other countries like Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom were able to perform home-based CR in non-frail patients (Taylor et al., Citation2015). Our findings add to the body of knowledge by suggesting that trained primary care PTs can also utilize home-based CR in frail older patients.

Some aspects of our study warrant consideration. First, the sample size in our study was small, potentially limiting the scope of our findings. However, our observations and interviews with the last two PTs did not reveal new codes or themes. Combining data from observations and interviews may have accelerated saturation. Second, not all included patients in the CCB-study were willing to participate in home-based CR. Also, PTs reported that two patients had dropped out of the home-based CR component of the CCB-study because they found the many healthcare professionals visiting them to be overwhelming. Our result may therefore not apply to highly unmotivated frail patients. Finally, our study was conducted in the Netherlands. Studies in other countries with their specific healthcare systems may provide additional insights on the local challenges for implementation.

Recommendations for further research and implementation

Findings in our pilot study indicate that home-based CR is feasible, but with adjustments to meet the needs of frail older patients, such as: 1) replacing the usual exercise tests like the 6-minute walk test with more functional (i.e. 30-second chair stand test) and feasible tests (e.g. 2-minute step test) (Rikli and Jones, Citation1999); 2) using different tools for measuring activity levels (e.g. activity tracker instead of METs) (Theou, Jakobi, Vandervoort, and Jones, Citation2012); and 3) adapting exercise type and intensity according to the patient’s comorbidities and capability (Dekker, de Rooij, and van der Leeden M, Citation2016). Further research is needed to confirm the applicability and responsiveness of exercise tests and to select the best tool for measuring daily activity levels. It is unclear which exercise components lead to the best results regarding physical functioning, hospital readmission, and mortality. Sandercock, Cardoso, Almodhy, and Pepera (Citation2013) found a limited effect on mortality and morbidity for low volumes of exercise prescription, however for this frail population aiming on physical independence seems more important. The optimal amount of exercise and physical activity remains unclear. Since there are no norms for frail older cardiac patients (Tudor-Locke et al., Citation2011) exercise programs should be tailored based on patients capacity, activity levels, and personal goals. To objectively assess the effects of physical therapy in frail older patients, activity levels (e.g. activity monitor) are more practical than the VO2-max measures (Brubaker et al., Citation2009; Witham, Daykin, and McMurdo, Citation2008). Home-based cardiac rehabilitation including tele monitoring showed similar outcome effects and higher satisfaction rates in the low- to moderate risk patients, and may also be feasible for coaching frail older cardiac patients to increase physical activity (Brouwers et al., Citation2020). Future research should investigate whether this approach will lead to improved activity in this older population, whilst PTs experience difficulty in motivating these patients face to face. Considering the heterogeneity of frail older patients with CVD, more research analyzing subgroups within this population is needed to identify groups for whom home-based CR is feasible, safe and effective (Vaduganathan et al., Citation2015).

Conclusion

This study suggests that primary care PTs found the CCB-home-based CR protocol to be feasible, and that it provided practical guidance in the treatment of a sample of frail older patients. Important challenges to further improve home-based CR are the identification of an optimal level of CR intensity, selection and identification of exercise tests and measures that are suited for home-based CR, and the integration of interventions to optimize the patients’ self-regulation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants in the pilot of the CCB transitional care program and the contribution of all participating physiotherapists and nurses. We especially thank Ferdinand de Haan for his work on the CCB-CR protocol.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achttien RJ, Staal JB, Merry AH, van der Voort SS, Klaver RJ, Schoonewille S, Verhagen SJ, Leeneman HT, van Beek J, Bloemen S, et al. 2011 KNGF clinical practice guideline for physical therapy in patients undergoing cardiac rehabilitation; [Accessed 25 May 2021]. https://www.kngf2.nl/binaries/content/assets/kennisplatform/onbeveiligd/guidelines/cardiac_rehabilitation_practice_guidelines_2011.pdf.

- Achttien RJ, Staal JB, van der Voort S, Kemps HM, Koers H, Jongert MW, Hendriks EJ 2013 Practice recommendations development group 2013 exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease: A practice guideline. Netherlands Heart Journal. 21: 429–438. DOI:10.1007/s12471-013-0467-y

- Achttien RJ, Staal JB, van der Voort S, Kemps HM, Koers H, Jongert MW, Hendriks EJ 2015 Practice recommendations development group 2015 exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with chronic heart failure: A dutch practice guideline. Netherlands Heart Journal. 23: 6–17. DOI:10.1007/s12471-014-0612-2

- Afilalo J 2019 Evaluating and treating frailty in cardiac rehabilitation. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 35: 445–457. DOi:10.1016/j.cger.2019.07.002

- Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WL, Bassett DR, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, et al. 2000 Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 32: S498–504. DOI10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009

- Backman WD, Levine SA, Wenger NK, Harold JG 2020 Shared decision-making for older adults with cardiovascular disease. Clinical Cardiology 43: 196–204. DOi:10.1002/clc.23267

- Bakhshayesh S, Hoseini B, Bergquist R, Nabovati E, Gholoobi A, Mohammad-Ebrahimi S, Eslami S 2020 Cost-utility analysis of home-based cardiac rehabilitation as compared to usual post-discharge care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Expert Review of Cardiovascular Therapy 18: 761–776. DOi:10.1080/14779072.2020.1819239

- Bell SP, Saraf A 2014 Risk stratification in very old adults: How to best gauge risk as the basis of management choices for patients aged over 80. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 57: 197–203. DOi:10.1016/j.pcad.2014.08.001

- Bellet RN, Adams L, Morris NR 2012 The 6-minute walk test in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation: Validity, reliability and responsiveness - A systematic review. Physiotherapy 98: 277–286. DOi:10.1016/j.physio.2011.11.003

- Bohannon RW, Crouch RH 2019 Two-minute step test of exercise capacity: Systematic review of procedures, performance, and clinimetric properties. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy 42: 105–112. DOi:10.1519/JPT.0000000000000164

- Bostrom J, Sweeney G, Whiteson J, Dodson JA 2020 Mobile health and cardiac rehabilitation in older adults. Clinical Cardiology 43: 118–126. DOi:10.1002/clc.23306

- Brouwers RW, van Exel HJ, van Hal JM, Jorstad HT, de Kluiver EP, Kraaijenhagen RA, Kuijpers P, van der Linde MR, Spee RF, Sunamura M, et al. 2020 Cardiac telerehabilitation as an alternative to centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Netherlands Heart Journal 28: 443–451. DOI:10.1007/s12471-020-01432-y

- Brubaker PH, Moore JB, Stewart KP, Wesley DJ, Kitzman DW 2009 Endurance exercise training in older patients with heart failure: Results from a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 57: 1982–1989. DOi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02499.x

- Butland RJ, Pang J, Gross ER, Woodcock AA, Geddes DM 1982 Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. British Medical Journal 284: 1607–1608. DOi:10.1136/bmj.284.6329.1607

- Buurman BM, Hoogerduijn JG, van Gemert Ea, de Haan Rj, Schuurmans MJ, de Rooij Se 2012 Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized older patients with distinct risk profiles for functional decline: A prospective cohort study. PLoS One 7: e29621. DOi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029621

- Cleland JA, Fritz JM, Whitman JM, Palmer JA 2006 The reliability and construct validity of the neck disability index and patient specific functional scale in patients with cervical radiculo-pathy. Spine 31: 598–602. DOi:10.1097/01.brs.0000201241.90914.22

- Corbin J, Strauss A 2008 Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Dekker J, Buurman BM, van der Leeden M 2019 Exercise in people with comorbidity or multimorbidity. Health Psychology 38: 822–830. DOi:10.1037/hea0000750

- Dekker J, de Rooij M, van der Leeden M 2016 Exercise and comorbidity: The i3-S strategy for developing comorbidity-related adaptations to exercise therapy. Disability and Rehabilitation 38: 905–909. DOi:10.3109/09638288.2015.1066451

- Doll JA, Hellkamp A, Thomas L, Ho PM, Kontos MC, Whooley MA, Boyden TF, Peterson ED 2015 Wang TY 2015 effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation among older patients after acute myocardial infarction. American Heart Journal 170: 855–864. DOI:10.1016/j.ahj.2015.08.001

- Forman DE, LaFond K, Panch T, Allsup K, Manning K, Sattelmair J 2014 Utility and efficacy of a smartphone application to enhance the learning and behavior goals of traditional cardiac rehabilitation: A feasibility study. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention 34: 327–334. DOi:10.1097/HCR.0000000000000058

- Gurses AP, Marsteller JA, Ozok AA, Xiao Y, Owens S, Pronovost PJ 2010 Using an inter-disciplinary approach to identify factors that affect clinicians’ compliance with evidence-based guidelines. Critical Care Medicine 38: S282–291. DOI:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e69e02

- Heim N, van Fenema EM, Weverling-Rijnsburger AW, Tuijl JP, Jue P, Oleksik AM, Verschuur MJ, Haverkamp JS, Blauw GJ, van der Mast Rc, et al. 2015 Optimal screening for increased risk for adverse outcomes in hospitalised older adults. Age and Ageing 44: 239–244. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afu187

- Jensen GM, Gwyer J, Shepard KF 2000 Expert practice in physical therapy. Physical Therapy 80: 28–52. DOi:10.1093/ptj/80.1.28

- Jepma P, Latour CH, Barge IH, Verweij L, Peters RJ, Op Reimer WJ S, Buurman BM 2021a Experiences of frail older cardiac patients with a nurse-coordinated transitional care intervention - A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research 21: 786. DOi:10.1186/s12913-021-06719-3

- Jepma P, Verweij L, Buurman BM, Terbraak MS, Daliri S, Latour CH, Ter Riet G, Karapinar-Carkit F, Dekker J, Klunder JL, et al. 2021b The nurse-coordinated cardiac care bridge transitional care programme: A randomised clinical trial. Age and Ageing 50: 2105–2115. DOI:10.1093/ageing/afab146

- Jones CJ, Rikli RE, Beam WC 1999 A 30-s chair-stand test as a measure of lower body strength in community-residing older adults. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 70: 113–119. DOi:10.1080/02701367.1999.10608028

- Khadanga S, Savage PD, Ades PA 2019 Resistance training for older adults in cardiac rehabilitation. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 35: 459–468. DOi:10.1016/j.cger.2019.07.005

- Krumholz HM, Lin Z, Keenan P, Chen J, Ross J, Drye E, Bernheim S, Wang Y, Bradley E, Han LF, et al. 2013 Relationship between hospital readmission and mortality rates for patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, or pneumonia. JAMA 309: 587–593. DOI:10.1001/jama.2013.333

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD 2016 Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research 26: 1753–1760. DOi:10.1177/1049732315617444

- Nied RJ, Franklin B 2002 Promoting and prescribing exercise for the elderly. American Family Physician 65: 419–426.

- Noble BJ, Borg GA, Jacobs I, Ceci R, Kaiser P 1983 A category-ratio perceived exertion scale: Relationship to blood and muscle lactates and heart rate. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 15: 523–528. DOi:10.1249/00005768-198315060-00015

- O’Neill D, Forman DE 2019 Never too old for cardiac rehabilitation. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 35: 407–421. DOi:10.1016/j.cger.2019.07.001

- Pepera G, McAllister J, Sandercock G 2010 Long-term reliability of the incremental shuttle walking test in clinically stable cardiovascular disease patients. Physiotherapy 96: 222–227. DOi:10.1016/j.physio.2009.11.010

- Piepoli MF, Corra U, Adamopoulos S, Benzer W, Bjarnason-Wehrens B, Cupples M, Dendale P, Doherty P, Gaita D, Hofer S, et al. 2014 Secondary prevention in the clinical management of patients with cardiovascular diseases. Core components, standards and outcome measures for referral and delivery: A policy statement from the cardiac rehabilitation section of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Endorsed by the Committee for Practice Guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 21: 664–681. DOI:10.1177/2047487312449597

- Pol M, Peek S, van Nes F, van Hartingsveldt M, Buurman B, Krose B 2019 Everyday life after a hip fracture: What community-living older adults perceive as most beneficial for their recovery. Age and Ageing 48: 440–447. DOi:10.1093/ageing/afz012

- Rikli RE, Jones CJ 1999 Development and validation of a functional fitness test for community-residing older adults. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity 7: 129–161. DOi:10.1123/japa.7.2.129

- Rohrbach G, Schopfer DW, Krishnamurthi N, Pabst M, Bettencourt M, Loomis J, Whooley MA 2017 The design and implementation of a home-based cardiac rehabilitation program. Federal Practitioner 34: 34–39.

- Ruano-Ravina A, Pena-Gil C, Abu-Assi E, Raposeiras S, van ‘T Hof A, Meindersma E, Bossano PEI 2016 Gonzalez-Juanatey JR 2016 participation and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs. A systematic review. International Journal of Cardiology 223: 436–443. DOI:10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.08.120

- Sandercock G, Cardoso F, Almodhy M, Pepera G 2013 Cardiorespiratory fitness changes in patients receiving comprehensive outpatient cardiac rehabilitation in the UK: A multicentre study. Heart 99: 785–790. DOi:10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303055

- Schertz A, Herbeck Belnap B, Chavanon ML, Edelmann F, Wachter R, Herrmann-Lingen C 2019 Motivational interviewing can support physical activity in elderly patients with diastolic heart failure: Results from a pilot study. European Society of Cardiology Heart Failure 6: 658–666. DOi:10.1002/ehf2.12436

- Shields GE, Wells A, Doherty P, Heagerty A, Buck D, Davies LM 2018 Cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation: A systematic review. Heart 104: 1403–1410. DOi:10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312809

- Singh SJ, Morgan MD, Scott S, Walters D, Hardman AE 1992 Development of a shuttle walking test of disability in patients with chronic airways obstruction. Thorax 47: 1019–1024. DOi:10.1136/thx.47.12.1019

- Tamuleviciute-Prasciene E, Drulyte K, Jurenaite G, Kubilius R, Bjarnason-Wehrens B 2018 Frailty and exercise training: How to provide best care after cardiac surgery or intervention for elder patients with valvular heart disease. BioMed Research International 2018: 9849475. DOI:10.1155/2018/9849475

- Taylor RS, Dalal H, Jolly K, Zawada A, Dean SG, Cowie A, Norton RJ 2015 Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 8: CD007130.

- Theou O, Jakobi JM, Vandervoort AA, Jones GR 2012 A comparison of physical activity (PA) assessment tools across levels of frailty. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 54: e307–314. DOi:10.1016/j.archger.2011.12.005

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J 2007 Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Society for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–357. DOi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Tudor-Locke C, Craig CL, Aoyagi Y, Bell RC, Croteau KA, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Ewald B, Gardner AW, Hatano Y, Lutes LD, et al. 2011 How many steps/day are enough? For older adults and special populations. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 8: 80. DOI:10.1186/1479-5868-8-80

- Vaduganathan M, Butler J, Roessig L, Fonarow GC, Greene SJ, Metra M, Cotter G, Kupfer S, Zalewski A, Sato N, et al. 2015 Clinical trials in hospitalized heart failure patients: Targeting interventions to optimal phenotypic subpopulations. Heart Failure Reviews 20: 393–400. DOI:10.1007/s10741-015-9485-8

- van Weel C, Schellevis FG 2006 Comorbidity and guidelines: Conflicting interests. Lancet 367: 550–551. DOi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68198-1

- Verweij L, Jepma P, Buurman BM, Latour CH, Engelbert RH, Ter Riet G, Karapinar-Carkit F, Daliri S, Peters RJ, Op Reimer WJ Scholte 2018 The cardiac care bridge program: Design of a randomized trial of nurse-coordinated transitional care in older hospitalized cardiac patients at high risk of readmission and mortality. BMC Health Services Research. 18: 508. DOI:10.1186/s12913-018-3301-9

- Verweij L, Spoon DF, Terbraak MS, Jepma P, Peters RJ, Op Reimer WJ S, Latour CH, Buurman BM 2021 The cardiac care bridge randomized trial in high-risk older cardiac patients: A mixed-methods process evaluation. Journal of Advanced Nursing 77: 2498–2510. DOi:10.1111/jan.14786

- Verweij L, van de Korput E, Daams JG, Ter Riet G, Peters RJ, Engelbert RH, Op Reimer WJS, Buurman BM 2019 Effects of postacute multidisciplinary rehabilitation including exercise in out-of-hospital settings in the aged: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 100: 530–550. DOi:10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.010

- Vigorito C, Abreu A, Ambrosetti M, Belardinelli R, Corra U, Cupples M, Davos CH, Hoefer S, Iliou MC, Schmid JP, et al. 2017 Frailty and cardiac rehabilitation: A call to action from the EAPC Cardiac Rehabilitation Section. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 24: 577–590. DOI:10.1177/2047487316682579

- Witham MD, Daykin AR, McMurdo ME 2008 Pilot study of an exercise intervention suitable for older heart failure patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 7: 303–306. DOi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.01.109

Appendices Appendix A. Directions for increasing exercise intensity and physical activity in old patients with cardiovascular disease

Appendix B. Screening tool for frail elder of the Dutch Safety Management System (DSMS)

Appendix C. Theoretical framework of Gurses

Figure C1. Conceptual interdisciplinary framework of clinicians’ compliance with evidence-based guidelines, by Gurses 2010.

The framework of Gurses () shows the expected interrelationships among four major categories of factors (System, Provider, Guideline, and Implementation characteristics) that influence guideline compliance. System (e.g. a checklist or communication system) and guideline characteristics (e.g. relative advantage, complexity, compatibility) can positively and negatively influence provider characteristics (e.g. awareness, agreement with the guidelines, self-efficacy). Pre-existing characteristics influence compliance with the guideline through their impact on implementation characteristics. These implementation characteristics (e.g. tension for change) function as mediators and moderators of the pre-existing characteristics toward the behavior of clinicians’ compliance or noncompliance to guidelines. For example, low self-efficacy (provider characteristic) may diminish implementation quality and thus lead to low compliance (mediation). Or, as a moderator, adequate implementation can diminish the impact of low self-efficacy. Clinicians’ compliance to guidelines influence patient outcomes, but patient outcomes are also influenced by patient characteristics. For example, present comorbidity may influence guideline adherence, e.g. PTs may prescribe too low exercise intensity because they don’t understand complex interactions between diseases and as a consequence decide to underload the patient just to be safe. Finally, next to unintentional errors (e.g. forgetting to check glucose levels before and after exercise), careful and deliberate clinical decision-making may lead PTs to intentionally deviate from the guidelines (e.g. postponing aerobic exercise due to a COPD exacerbation).