ABSTRACT

Background

This article focuses on knowledge development and health professionals’ opportunities to use evidence-based practice (EBP). We studied registered physiotherapists (PT), occupational therapists (OT) and nurses (RN) in Swedish elderly-care institutions, a sector known for high turnover and shortages of competent staff.

Objective

To examine the perspectives of healthcare providers on professional knowledge development and EBP in their organization.

Methods

We conducted on-site qualitative interviews with a purposive sample of PTs, OTs and RNs, in six elderly care institutions. Situational analysis was used to analyze the material.

Results

Three discursive professional positions were found: 1) Professional ambition in confusing work organization; 2) Professional ambition in a knowledge-promoting work organization; and 3) Professional indifference with few aspirations for knowledge development. Professional aspirations toward knowledge development were high in two of these positions, whereas the third represents a slightly different approach with fewer aspirations for knowledge development. Linked to these professional approaches to knowledge development is a continuum of aggravating or facilitating factors within the work organization, including varying degrees of support from leadership of the organization, as well as few opportunities for rewards.

Discussion and conclusions

It is concluded that elderly care needs to develop strategies for evidence-based practice in order for the sector to become a sustainable arena for health professionals’ career development, and in order to improve the quality of care for the elderly.

Introduction

This article focuses on knowledge development and health professionals’ opportunities to use evidence-based practice (EBP). The notion of evidence-based practice is a vital component of healthcare practice and clinicians are expected to be “research consumers” and to work as “reflective practitioners” (Schön, Citation2003) within healthcare institutions, which means using the best available evidence as a basis for professional judgments and clinical decision-making. Definitions of EBP identify three important characteristics: 1) using the best available research evidence in combination with; 2) professional expertise; and 3) patients’ experiences, participation and knowledge (Sackett, Citation1997). Haynes, Devereaux, and Guyatt (Citation2002) developed Sackett’s original definition of EBP to also include the clinical state of the patient and contextual factors such as the clinical setting. Di Censo, Guyatt, and Ciliska (Citation2005) developed the EBP model for nursing by adding a component named ‘healthcare resources.’ In Sweden, healthcare policies and healthcare law require practitioners to use available research findings and best practice. EBP has therefore become the tool with which to ensure that research findings are systematically used and integrated into everyday practice. This in turn means that clinical guidelines informed by ever evolving research are developed at national and regional levels and heavily promoted, disseminated and governed by healthcare authorities such as the National Board of Health and Welfare (Citation2013) as well as by professional associations.

EBP can thus be viewed as both an external and an internal drive for professional development, and it has long been regarded as the gold standard for Swedish healthcare and in judging criteria for high-quality care and rehabilitation. All of this requires professionals to be constantly updating their skills and knowledge. Accordingly, the promotion of EBP is closely connected to a discourse of quality in care and a strong belief in professional knowledge as a means of improving healthcare.

However, research reveals that the implementation of EBP into everyday healthcare work is beset with barriers and difficulties (Boström, Ehrenberg, Gustavsson, and Wallin, Citation2009; Boström et al., Citation2018; Heiwe et al., Citation2011; Perry et al., Citation2011). A number of studies demonstrate factors that obstruct knowledge development and the use of EBP to support clinical decision-making (Rudman et al., Citation2012; Scurlock-Evans, Upton, and Upton, Citation2014; Sirkka, Zingmark, and Larsson-Lund, Citation2014; Yoder et al., Citation2014). Scurlock-Evans, Upton, and Upton (Citation2014) listed a number of factors that either enable or hinder its implementation, of which the most important hindrances were time pressure, lack of skills for searching databases, and lack of resources. Other obstacles have been reported to be organizational inertia toward change and leadership inability to motivate and engage coworkers in knowledge development and EBP (Keisu, Öhman, and Enberg, Citation2016). Dannapfel (Citation2015) investigated Swedish physiotherapists and explored the conditions for using research evidence. She found that physiotherapists mostly value EBP in positive terms, but that its implementation into clinical practice is heavily dependent on work organization and leadership. Rudman et al. (Citation2012) studied Swedish registered nurses’ evidence-based practice and research usage and found variations ranging from 10% to 80%. In a recent study among registered nurses, Rudman et al. (Citation2020) found that registered nurses’ use of EBP was low to moderate, but the extent of practicing the EBP increased with the number of years in the profession and with specialist education. A qualitative evaluation of a structured implementation of EBP for physiotherapy in Swedish primary care emphasized collaboration between academy and practice in order to make EBP work in the clinical setting (Carlfjord et al., Citation2019). Another study investigated Swedish healthcare systems’ evidence-based policymaking in healthcare services and found that early phases of agenda-setting and policy formulation facilitate the implementation of EBP (Sundberg, Citation2016).

In this article, we focus on Swedish elderly care, a field that requires qualified professional competence. Work in elderly care is complex and accurate skills are a prerequisite for being able to provide care of good quality (Johansson, Citation2018). Due to increasing longevity and a growing elderly population, Swedish elderly care is facing immense demands in recruiting skilled professionals with adequate competence in order to deliver high-quality care and rehabilitation to the aging population. In ten years’ time, the sector will be experiencing a huge lack of competent and suitably trained staff (Statistics Sweden, Citation2017). The need for recruiting new employees within this sector is estimated to increase with 65% by the year 2035 (Johansson, Citation2018).

We believe all of these organizational drawbacks impact the work environment and therefore limit professionals from working in line with an evidence-based approach, as that requires both time and resources such as available technical equipement, IT-support and possibilities for literature search. Registered RNs, PTs and OTs do not constitute the majority of staff in elderly care, but they are essential in order to ensure quality of care and rehabilitation for the elderly. We argue, that through their academic education, they possess advanced competence regarding health, illness, bodily functioning and ability and thereby often act as managers and tutors to nursing aides and less educated caring staff. Hence, they have great responsibility for the outcome of care and rehabilitation. Studies focusing on knowledge development and EBP in elderly care are scarce. The aim of this study was to fill this knowledge gap by scrutizing RNs, PTs and OTs in elderly care to understand their views and ideas about professional knowledge development and EBP within their organizations. The following research questions provide the focus: 1) How do professionals view their competence in regard to elderly care; 2) How do they view and value knowledge development, continuing education and EBP; and 3) How do they regard organizational prerequisites and management support in terms of their needs for knowledge development, EBP and continuing education?

Methods

Study design and data collection

The study was approved by The Regional Ethical Review Board at Umeå University, Sweden. Informed consent was obtained through written as well as verbal information about the project, that participation was optional and that they could withdraw from the study at any point in time without explaining the reasons for withdrawal. They were also informed, and gave their consent, that information from the interviews could be published in research articles in which all identification characteristics were removed. To ensure confidentiality, the list of participants with its codes for their professions and workplaces was kept apart from the interview transcripts. When quoting the participants, we only use code number and profession.

The study design is qualitative, using a grounded theory situational analysis as developed by Clarke (Citation2005). We conducted on-site interviews with a purposive sample of RNs, PTs and OTs, in six elderly-care institutions. The current study is part of a larger, mixed-methods project where the primary goal was to investigate positive, rather than negative factors, for work in elderly care. We scrutinized work satisfaction, well-being, dignity, leadership and organization (Keisu, Citation2017; Keisu, Öhman, and Enberg, Citation2016, Citation2018; Öhman, Enberg, and Keisu, Citation2017). Thus, the institutions in the current paper were selected from a list of suggested well-functioning elderly-care facilities in the national survey included in the project (Keisu, Öhman, and Enberg, Citation2016; Öhman, Enberg, and Keisu, Citation2017). In a first step, we contacted the first-line manager of the institutions in order to get their permission to make on-site visits and conduct interviews with the employees. In a second step, and when having received permission from the managers, we invited professionals from the three professions to participate in on-site interviews. They signed up for interviews by contacting the research team.

In line with a grouned theory situational analysis approach, we were eager to cover a variety of elderly care institutions, in order to catch diversity and complexity (Clarke, Friese, and Washburn, Citation2015; Clarke and Keller, Citation2014). Therefore, we used a purposive sample technique (Dahlgren et al., Citation2019) by selecting institutions from the list with varying geographical location, arrangements of elderly care, ownership and organizational structure. This means that we covered facilities from the north to the south, and institutions that were run by both public authorities and private enterprises. They included nursing homes, rehabilitation centers for the elderly and geriatric hospitals.

The interviews were conducted in a conversational style, meaning that although they all followed a thematized interview guide, they varied slightly in focus and approach, depending on the informants and the situation under which they worked. All the three researchers were engaged in the data collection, and in conducting the interviews; sometimes alone, sometimes together two and two. In the latter situation, one took the role of steering the interview and the other served as observer and note-taker. In line with a grounded theory study, we applied a so called ‘emergent study design’ (Dahlgren et al., Citation2019) meaning that we did not decide on every detail beforehand, but used the emerging results in subsequent interviews, in which we then probed on preliminary outcomes from previous interviews. This enriched the data collection and helped build the final, negotiated outcome. Interviews lasted 60–90 minutes and were voice-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The thematic interview guide circled around the following questions: Is it possible to use your professional competence in your work?; How do you view professional competence and knowledge development in relation to elderly care?; How is knowledge development looked upon and organized in your workplace?; and What do managers do to support your knowledge development?

Data analysis

The interview texts were analyzed using grounded theory situational analysis, as described by Clarke (Citation2005). Clarke (Citation2005) defined situational analysis as a constructivist grounded theory approach that seeks to analyze a specific situation of interest by identifying and representing the range of variation and complexity in the data. Building on symbolic interactionism, a situational analysis focuses on the social worlds and the social arenas of importance for the study (Clarke, Friese, and Washburn, Citation2015). In our case, this means that we regard Swedish elderly care as the social world and the social arena (i.e. the situation under study). On this social arena, the healthcare professionals engage, act and interact with each other in professional groups of various kinds, as well as with clients. In line with Clarke (Citation2005) we also understand this social world as fluctuating and constantly changing. Further, the professionals are part of the organizational dynamics of elderly care specifically, and Swedish healthcare generally with all their prerequisites, circumstances and drawbacks. All of this results not only in personal experience, but also in collective, shared realities; realities that we in this study try to map and understand when it comes to evidence-based practice and knowledge development. This means, that a situational analysis goes beyond the individual, personal lived experiences and views the informants as collective actors in webs of social processes.

During a situational analysis, the researchers aim to analyze subject positions in the studied context and to identify how different discursive constructions intersect or diverge (Clarke, Citation2005). In line with a constructivist grounded theory analysis, we started the analysis by performing a sentence-by-sentence open coding of the texts to identify different positions among the professionals (Charmaz, Citation2006). Simultaneous memoing and constant comparisons between the emerging results allowed us to identify different positions; and the discourses that framed the professionals’ understanding of professional competence, knowledge development and the context in which professional performance is practiced. This iterative selective coding process continued until a higher level of abstraction was reached, meaning that axes of variation were identified. The emerging and final results were discussed and negotiated between the three researchers in a series of meetings and workshops.

The results of a situational analysis can be presented in several ways: as situational maps, arena maps or positional maps (Clarke, Citation2005). Situational maps are often used at the beginning of the analytical process to explore the relationships between the different elements present in the situation; arena maps allow the authors to identify the collective actors present in the situation, along with their relationships; and positional maps portray the collective actors’ different discursive positions within the situation. In this study, we have chosen to present the findings in a final positional map depicting different professional positions in relation to knowledge development in elderly-care organizations. The quotations serve as illustrations and examples of the ways in which the informants expressed their views on EBP and knowledge development.

Reflexivity and Trustworthiness

As described by feminist philosopher Donna Haraway, knowledge is partial, limited and situated, i.e. there is no view from no-where and the researcher with her/his worldviews, methodologies and interactions with the studied field, is an active part in the on-going process of investigation (Haraway, Citation1988). The social world/social arena theory also emphasizes “the negotiated nature of knowledge construction as conflictual and shaped by power” (Fosket, Citation2015). This notion rests heavily on Michel Foucault’s influential work on how knowledge and power are interwoven, produced, and re-produced. This shapes all social interaction (Foucault, Citation1988). As qualitative researchers, we embrace these epistemological and ontological views, and we are aware of the researchers’ subject positions as part of all research. In this particular study, we have used our social theory competences based in health systems’ research, profession theory and work organization theory. Throughout the research process, we have used these specific competences in varying degrees. Following Dahlgren et al. (Citation2019) we tried to bracket our pre-understanding and our theoretical frame of reference in the beginning of the coding process of the interviews. This was done in an attempt to better understand the social world of the interviewees’ and to discover new aspects of the situation under study, all in order to conduct open-minded interpretations. In the later stages of analysis, we used our theoretical frames of reference to mirror the findings from the interviews, so called ‘theory integration’ (Charmaz, Citation2006).

The sample consists of both women and men, but we do not compare the two groups. Such comparisons were not the aim of this study. However, the gender coding of healthcare work may well have played a role in how the professionals perceive and position themselves in relation to knowledge development in the organization. These aspects rest outside the aim and scope of this article. Therefore, we decided to not include a discussion about gender, as we have published substantially about the gendered nature of healthcare work, gendered organizations and gender and leadership in previous research (Enberg, Citation2009; Öhman, Citation2001; Öhman, Enberg, and Keisu, Citation2017; Tafvelin, Keisu, and Kvist, Citation2020). Further, we are fully aware of the fact that the three professional groups possess different competencies and work tasks; however, we decided not to make comparisons between the professional groups. The informants offered similar stories about evidence-based practice and knowledge development, and we therefore decided to regard them as one group (i.e. health professionals working in elderly care).

The truth value (trustworthiness) of a qualitative study can be increased by a number of tools and techniques. In this study we have chosen to use Lincoln and Guba (Citation1985) definitions and concepts credibility, transferability and confirmability. Credibility refers to the process in which the researchers are able to capture the multiple realities of the studied situation. In order to increase credibility, we used several techniques designed for this purpose. In the method section, we have thoroughly described (thick description) the processes of sampling and data collection. We have also clarified our theoretical points of departure. In the phases of analysis, we used triangulation of researchers as an important means to create trustworthiness. This allowed us to use our different social theory competencies of profession theory, health system’s research and organizational theory to mirror the emerging results from different angles. Following a grounded theory study design, the process of constant comparisons and memoing helped us in finding patterns and discoursive positions of importance for the aim and the research questions. Transferability has to do with how the findings can be transferred, or generalized, to other social contexts. The findings from this study will not be generelizable in a traditional positivistic way, and of course not from a statistical point of view. However, they may still be valid in other, similar social contexts. To facilitate such transfer, we used a theoretical and analytic perspective. In that sense, the concept transferability serves as a means to state that the findings are valid beyond the study context. In the discussion section, we contextualize and discuss the findings in relation to existing research on elderly care in Sweden, and by using social theory on work and organization, which we hope will allow for a theoretical generalization. In order to increase confirmability, we use quotations from the interviews as examples of the ways in which the informants talked about and positioned themselves in the web of personal and collective interactions in elderly care organizations.

Results

In total, 17 health professionals were interviewed (i.e. fourteen women/three men; five RNs, six PTs, and six OTs). No one acted as managers at the time of the interviews ().

Table 1. Study participants, type of institution and ownership of institutions.

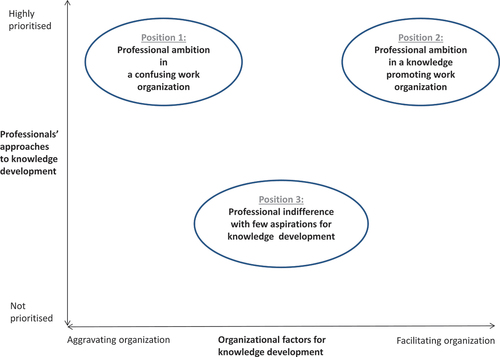

The situational analysis revealed three distinct professional discursive positions: 1) Professional ambition in confusing work organization; 2) Professional ambition in a knowledge-promoting work organization; and 3) Professional indifference with few aspirations for knowledge development. They portray different aspects of professional knowledge development in relation to the work organization and its varying abilities to support such development. Professional aspirations for knowledge development were found to be high in two of the professional positions, whereas the third represents a slightly different approach with fewer such aspirations. Linked to these professional approaches to knowledge development are aggravating or facilitating factors in the work organization. The positional map portrays the three professional positions along a continuum of ‘approaches to knowledge development’ on one axis, and a ‘continuum of organizational factors’ on the other ().

Figure 1. Positional map of professionals’ approaches to, and organizational factors for, knowledge development and EBP in elderly care.

Position 1. Professional ambition in confusing work organization

This discursive position represents an ambitious and positive approach toward EBP, and at the same time expresses ambiguity concerning organizational opportunities for knowledge development. The professionals within this position believe that they have acquired a certain amount of basic knowledge and competence from their undergraduate professional training to treat and deal with frail and sick elderly people. But they also strongly emphasize that this is far from enough and that there is a constant need to update one’s knowledge base through continuing education of different kinds and by searching for new evidence-based findings. They ask for formal and advanced courses at master’s level within the field of elderly care, but argue that few such courses exist. They experience a need for improved competence on issues around care for the elderly, on multi-sick elderly, on dementia and on the aging society. They believe that, with such an improved knowledge base, they would be able to use research evidence better and deliver more advanced care and rehabilitation for the elderly, all of which would improve quality of life for the elderly. This could save money for society, as the elderly would then probably become more independent, it was argued. They also wish to create networks for health professionals in elderly care in order to support each other.

Well, I’ve been engaged in a variety of working groups for developing the care here, I’ve taken many, many extra credits in university courses, for instance in public health, and all sorts of courses. (B5, OT)

However, there are a number of factors that create obstacles to gaining EBP and professional knowledge development, despite their high motivation. It seems as though these professionals receive different and contrasting messages from both managers and the wider organization. On the one hand, they are encouraged and expected to constantly update their knowledge base, but they reasoned that sometimes this is more rhetoric than actual support. They claimed that, although they are highly motivated, they do not get support from their managers. The obstacles are several and diverse, but can be summarized as a lack of resources in the organization and a management that either does not understand the importance of continuing knowledge development, or does not regard it as very important. It was argued that elderly care lacks general resources and therefore staff development and continuing education are often downsized when priorities are set. In addition, lack of staff means that there is no one to provide cover, if someone needs time to update her/his knowledge base. If the manager does not regard professional competency and continuing education as a key issue for good care, the professionals will lag behind in terms of their knowledge about the latest research findings and evidence for high-quality care for the elderly, they argued. And even when the professionals emphasize their need for continuing education in their dialogue with managers, very often nothing happens.

I don’t think that the leaders understand what our professional competence as occupational therapists is about, when it comes to elderly care. We have the ability, if we were allowed, to introduce a general thinking in all staff about rehabilitation and activity for the older living here, but the leaders don’t see it that way. But that requires time and training of all employees here. The leaders don’t understand the importance of that. (B3, OT)

These aggravating factors result in a situation in which the professionals are forced to use their spare time if they want to develop professionally. The issue of rewards and compensation for improved competence was brought up as another aggravating factor because they do not get paid more if they increase their knowledge base, for instance by upgrading their degree to master’s level. They claimed that there are too few career paths for the health professions in elderly care and that salaries are too low. The ambiguous stance and conflicting messages from managers and the organization’s lack of a distinct reward system, which requires them to constantly update and develop their knowledge base, but at the same time does not reward such development, makes the professionals ambivalent. They seem to have the ambition to develop their knowledge but are hampered by aggravating factors concerning resources and managerial support.

I think we have too few possibilities for knowledge development. They ought to do much more to make that happen ….but, unfortunately …… As it is now, it’s probably not very easy for the manager to do much about it, as we’re connected to many other managers who deal with much frailer people and it seems like they don’t regard competence development as important for us with higher education. In our previous organization, we were offered competence development in a completely different way than now. We’re supposed to be mentors and tutors for nurse aides and other staff, and I need to improve my competence regarding tutoring and supervision and teaching them. There are very few such opportunities, actually nothing …. And I take time from my leisure time to improve my competence, to go on courses, study and so on ….because I’m interested ….that’s it. The leadership talks a lot, and emphasizes competence development and its importance, they’ve been doing that for many years now, but so far I haven’t seen that they really prioritize it, I mean in terms of resources. So improving my competence, I do that during my leisure time, because I find it very important. I would never have time to do that during working hours! (F3, RN)

Position 2. Professional ambition in a knowledge-promoting work organization

This discursive position is in one sense similar to the previous one, in that knowledge development and EBP are highly valued by the professionals themselves. They have the desire and the ambition to constantly update their knowledge base and to work in accordance with EBP. They regard themselves as having a certain formal competence through their basic education, and expect that, with increased experience, this competence will increase. Also, from this position, they ask for more formal and advanced education within the field of elderly care, and specifically with regard to knowledge on dementia, which they foresee will increase in our aging society. They claimed that developing their competence will improve elderly care. As in position 1, they sought to establish professional networks for those working in elderly care.

In the team of occupational therapists, we’ve created something we call “evidence meetings”, in which we gather to discuss the latest research findings. (D3, OT)

Also similar to position 1, they argued that increased competence would make them work better for the elderly in order to support quality of life and health status even for the oldest and frailest. In the long run, this would reduce costs and save money for the community. Accordingly, they strongly believed in scientific knowledge and that the EBP approach to healthcare work is valid and necessary.

In contrast to position 1, however, professionals adhering to this position work in a knowledge-driven environment, a work organization which firmly emphasizes EBP and knowledge development. These professionals experience an obligation to develop professionally and their managers strongly encourage continuing education and competence development. The circumstance that research and other types of development work are present in these work organizations, and that the elderly care institution is part of a research unit, strongly contribute to the organizational support for knowledge development for professionals.

It’s required of me to contribute with my competence and to develop it at this workplace … and I really appreciate that, it’s very good. And in my development dialogue with the manager, which is held every year, I can express my own plans and wishes for knowledge development and education, but also what kind of support I need from her in order to achieve my plans. So far, I’ve been able to achieve my plans. I’m very interested in maintaining and developing my competence. (A3, RN)

It’s the manager who has the responsibility for staff knowledge development here. There are several options …… I went to a conference recently, and I’m now thinking of some kind of master’s degree, but it’s not so easy to find a master’s course for physiotherapists with a suitable focus on elderly care. (E4, PT)

Also in contrast to position 1, here, time and other necessary resources seem to be allocated specifically for competence progression among employees, although the institutions may still struggle due to scarce resources. Some of the workplaces had developed systems for career paths and reward systems in which the health professionals received an increased salary with increased competence, especially when achieving a master’s degree.

It’s very important that we’re allowed to go to continuing education. I mean, it’s important that I have the possibility to develop myself theoretically. There needs to be an allowance for this. At the moment, I’m enrolled on a course at an advanced level about tutoring and I do that in working hours. (C2, OT)

So far, it’s been pretty good in terms of possibilities for competence development at this clinic, and we’ve been encouraged to engage in continuing education. We’re encouraged to enrol in education within the field of elderly care. And I have the old and shorter degree in physiotherapy, so I’m now enrolled on a bachelor’s programme to update my competence. My employer is very generous in this; I can do it during working hours. Right now, I’m on my way to conduct an interview for my final thesis work on the programme. So this is very good! And I really want this myself; it’s not just something forced on me. It fits well, because this clinic has a lot of research activities and is a research unit for elderly care within this hospital, so it’s a research-friendly work environment. And I think that if I wanted to continue after my bachelor’s, I’d get support for doing that. (C3, PT)

In sum, the advantages for the professionals adhering to this discursive position is that both the work organization and the managers seem to be supportive of their ambition to achieve professional development and a research-based approach to care for the elderly. The problems here are more connected to the fact that there is a scarcity of continuing education programmes for these professional groups and that academic courses designed for elderly care barely exist.

Position 3. Professional indifference with few aspirations for knowledge development

This discursive position is not as prominent as positions 1 and 2, but it is still valid to name it as a separate and distinct position. It is characterized by a certain amount of indifference and inertia among the professionals. This inertia has to do with how they view their need for competence development and the inclusion of EBP into elderly care. It seems that these professionals hesitate to fully embrace EBP, innovation or change. They seem to have worked for a long time in elderly care, and consider that they have gained substantial experience that they can rely on in their daily practice.

Well, it’s not through formal education that I gain my competence, it’s rather through the vast experience that I’ve achieved through working in elderly care for so long. (D4, RN)

In that sense, they have few aspirations for personal development and a perception that they are ‘good enough’ was obvious. They seem to be rather satisfied with things as they are and do not feel the immediate need for additional knowledge, although some sort of updating is always needed.

I think I’m in a phase of life in which I feel quite satisfied with things as they are. But of course, that could change in the future. Here, we can enrol on short courses within working hours, that’s okay with me. But talking about competence, and longer courses at university level, then I kind of think, well …. that’s not really for me. You see, we get updates about systems for patient records, and about computers and IT …. and about aids for the disabled, things you need in your daily work. And we have fairly good support for that, and I think that’s what we need, I mean … updates, that’s enough. (B6, PT)

They work rather independently and at their own pace. Large-scale changes are not needed, they claimed, but they do appreciate moderate or even slow changes. Within this position, it was also more difficult for us to understand how they viewed the role of the manager and their work organization. The notion that elderly care is not specifically demanding in terms of knowledge development and recent research findings was prevalent within this position, which in turn means that continuing education is not really needed.

The work tasks for physiotherapists in elderly care are not advanced. You don’t need to use very complicated methods here, that is my opinion. (F5, PT)

And, similar to position 1, efforts made toward professional advancement will not be rewarded in terms of increased salary or other types of career promotion, it was argued.

Discussion

The three discursive positions in elderly care portray enabling and hindering factors related to professional knowledge development, continuing education and EBP. These factors include the external demands placed on professionals, managerial and organizational factors and individual ambition for competence development. And although our informants are supposed to work in elderly care institutions that in the national survey were listed as good and well-functioning work places, we can see from the findings, specifically in position 1, that negative views about the organizational and leadership support for knowledge development and continuous education are obvious. The results from this study confirm results from the vast research literature on EBP in healthcare with regard to the need for supportive and strong leadership, time allocation and other contextual and organizational factors (Baatiema et al., Citation2017; Björk Brämberg et al., Citation2017; Carlfjord et al., Citation2019; Fristedt, Areskoug-Josefsson, and Kammerlinf, Citation2016; Harding et al., Citation2014; Johansson, Fogelberg-Dahm, and Wadensten, Citation2010; Lindström, Bernhardsson, and Copley, Citation2018; Schuman, Citation2017). Ehrenberg et al. (Citation2016) results from a Swedish national cohort study of recently registered nurses’ own beliefs of their capability for evidence-based practice showed stability over the first three years of working life after graduation. Boström et al. (Citation2018) demonstrated varying results as to students’ and four professions’ readiness for using EBP in Swedish geriatric care, and conclude that there is a need to improve the use of EBP, especially among nurses and occupational therapists.

Elderly care is seldom in focus in previous research on perceptions about EBP in Sweden. Therefore, this study helps to fill this knowledge gap. This study also adds new knowledge on professional pride in their struggle and ambition to do a good job in elderly care. In the struggle for professionalism, Ns, OTs and PTs are often, but not always, subordinated groups within the larger fields of healthcare (Enberg, Citation2009). From our analysis it became clear that the professionals in position 1 were often not prioritized for continuing education, and appropriate courses in elderly care seem to be generally scarce. Therefore, they have to struggle in order to develop professionally.

We argue that the promotion of EBP can serve as a facilitating factor for professional knowledge development in elderly care. This was obvious in position 2, where the work organization heavily promoted knowledge development and EBP and there was a close collaboration between academic research and clinical practice. It can also help support employees’ own individual drive for professionalism. It may, however, also impose stressful demands in a healthcare context characterized by aggravating factors such as low priority, scarce resources and weak management, such as in elderly care. Furthermore, we interpret the ambiguity expressed by the informants in position 1, with high demands by managers to develop and use EBP, but with low rewards, to be part of the hierarchical power structure in healthcare. The discrepancy in decision-making power is obvious, between those in policymaking positions at the top of regional boards in the healthcare organization who develop policies on EBP, and the professionals in clinical practice. However, there are also other contextual factors and policy reforms which certainly have affected the organizations and the professionals’ opportunities for knowledge development. During recent decades the Swedish welfare sector has undergone extensive transformation in line with a new public management (NPM) approach and these reforms have been clearly visible in the women-dominated welfare sectors (Hood, Citation1995: Meagher and Szebehely, Citation2018). The changes are characterized by a purchaser-provider split and competition. Further, an organizational norm of standardization, auditing and accountability is widely used in Swedish healthcare including elderly care (Anttonen and Meagher, Citation2013: Dellve et al., Citation2015; Meagher and Szebehely, Citation2013). The Swedish welfare sector is perdominantly publicly funded, and 80% of healthcare is funded through taxation money (Statistics Sweden, Citation2018). The politicians have set ambitious goals of universal coverage of high-quality health and caring services. However, resources are scarce in terms of funding, as well as of professionals’ time allocation, and therefore performance and achievements have been reduced (Ranci and Pavolini, Citation2015). This in turn is due to the fact that NPM is implemented within a context of austerity, with the specific aim of reducing public spending on welfare services (Ranci and Pavolini, Citation2015; Theobald and Luppi, Citation2018). A series of studies show how the establishment of NPM-inspired regulations have negatively impacted the working conditions for employees, for example a combined effect of increased monitoring of time allocation of various services and difficulties in delivering services when the decision-making autonomy is decreased (Brodin and Peterson, Citation2019; Hayes and Moore, Citation2017; Keisu, Citation2017; Meagher, Szebehely, and Mears, Citation2016; Strandell, Citation2019).

We interpret the limited support for the professonals’ knowledge development seen in position 1 to be a significant part of the downsides resulted from NPM. Therefore, and in spite of all these hindering factors, the professionals took on the responsibility to develop their knowledge base and use evidence-based practice. In that sense, knowledge development becomes a personal, individual committment, instead of a responsibility on the organizational and managerial levels. The professionals felt obliged to implement and use policies on EBP, but without sufficient resources, or rewards. Even when they make personal sacrifices in order to develop professionally, they will receive little in the way of rewards. Following Kanter’s (Citation1977) theory on work and organization, we interpret that the ambition to use EBP among most of the interviewees was integrated and internalized into the professionals’ ‘internal mental work’ through official policies, as well as through their professional organizations and their training at the universities. In her classical organizational theory Kanter (Citation1977) claimed that the structure of the organization and the social circumstances in which people find themselves determine both their motivation and their career success. Accordingly, the positions that employees hold in the organizational power hierarchy are vital for their opportunities to act and develop at work. Power structures can be both formal and informal. From this perspective, it is possible to understand that an employee in a certain position at work, and with limited opportunities and power, will be restricted in her/his career development, as well as in terms of self-esteem. When someone works for the betterment of the organization and when that job causes positive effects within the organization, but is not acknowledged, or does not lead to rewards, this becomes a restricting structure that holds back coworkers, instead of rewarding and upgrading them. This according to Kanter (Citation1977) causes a downward vicious circle, in which not only do the opportunities seem to be fewer, but self-esteem also decreases. There is a risk that employees within power structures characterized by so few opportunities and such low rewards will start turning their interests and efforts in directions other than the job. The reverse is also possible, in which high degrees of opportunity and power to choose and decide will result in development and growth within the work role, which in turn leads to increased responsibility and more advanced job tasks. The greater the opportunities in a position or work role, the more the employees dare to challenge and, accordingly, their self-esteem will increase.

Evidence-based practice was originally based upon the idea that clinicians should constantly engage in critical appraisal of existing research and use their clinical experience (Sackett, Citation1997). However, the ways in which Swedish healthcare authorities have come to implement EBP reveals a form of top-down governing through which the authorities decide what should be considered evidence-based knowledge and practice. With the dominant discourse being that EBP is the solution and the way forward in healthcare, it becomes more or less impossible to say anything other than positive things about it. However, the views expressed in position 3 reveal hesitancy about EBP and is maybe a critique of it. Norms of professionalism as long-term experience, which were emphasized in this position, may be used as a silent resistance strategy against the top-down authoritarian governing of EBP. The professionals might foresee a process of de-professionalization, in which they will not be able to use their problem-solving skills or clinical expertise, but will rather be expected to adhere to readymade guidelines and checklists. Chapman (Citation2012) argues that EBP supports a new form of governing ideology labeled ‘Digital Taylorism,’ based on coding and routinization of work. It is argued that this has turned professional knowledge and practice into a series of standardized and manualized practices that can be replicated anywhere and by anyone. Isaac and Francesci (Citation2008) argued that EBP has created a hierarchical discourse of knowledge that affects physiotherapists. This hierarchy thus reproduces existing inequalities. This critique against EBP points to questions concerning differing knowledge regimes, norms of professionality, work organization, and de-professionalization processes.

The professionals’ ambition for development is clearly demonstrated in the first and second discursive position. Those adhering to position 1 represent notions that challenge the prevailing norms and the organizational structure. These professionals want more than what the organization can offer. They are strong enough to initiate competence development in order to deliver high quality care and service to the elderly and steer their own professional development even when they have little support and they are faced with limited possibilities. They are restricted by their managers and the organization’s inability to reward professional drive. Despite these limiting contexts, they are striving for advancement and there is a cost to this; they often pay for their continuing education themselves, in terms of leisure time and private money. They are struggling from a subordinate position, but still persist because they believe that professional development through continuing education is essential. We judge this to be part of their professional pride and dignity at work (Keisu, Citation2017) and a kind of professional altruism to work for the betterment of the healthcare organization. For those adhering to position 2 with their facilitating and positive organizations and possibilities, we envisage an upward spiral of professional development. This personal drive, with or without available opportunities and supportive structures, must be viewed as a robust factor supporting knowledge development and evidencebased practice.

Conclusion

The analyses pre-dominantly reveal professional ambition to develop and use EBP, although there was also a certain inertia and indifference among some of the health professionals. Few questioned the need for competence development or the EBP approach, and it was specifically made clear in positions 1 and 2. In these positions, it was taken for granted that healthcare must be organized in accordance with EBP. We argue that aspects of knowledge development and professional advancement are visible, in which health professionals try to provide good-quality care to the elderly, at the same time as they are being squeezed into a limited position with little power and few opportunities to influence decisions about resources or time allocation. The most prominent factors hindering professional advancement and knowledge development were lack of resources, management and organizational complications, and a lack of power and rewards. The professionals asked for continuous education specifically in elderly care. To our knowledge, it is only in nursing that there exit such a programme, and our nurse informants did not seem to be very aware of this. Although different in terms of professional autonomy and performance, we argue that the three professions under study here are equally subordinated within the wider healthcare organization and therefore possess less power, less continuing training in searching for evidence and less access to sources of new research findings and evidence than, for example, physicians.

Based on the findings from this, and other studies, we conclude that elderly care needs to attract more health professionals in order for the sector to become a sustainable arena for health professionals’ career development, and in order to improve the quality of care for the elderly. It is therefore vital that elderly care develops strategies for retaining and developing competence among healthcare professionals. There is a need for improved support and skills on searching the internet for research literature and systematic reviews. The eldery care organizations need improvement in terms of arenas and meeting points for professionals. First line manager has the economic and operational responsibility in the organization. It is therefore vital that first line managers fulfill this responisibility and support the employees’ professional development. If there is no formal education to offer, it can be organized internally, for instance as regular journal clubs to dicsuss EBP, seminars on latest research, and invited experts to disseminate research findings on care and rehabilitation for the elderly. Such actions would enhance professionals’ competency and build organizational culture and structure for continuing education and knowledge development, thereby facilitating continued utilization of EBP in practice.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the interviewees in this study, who shared their views and professional experiences on evidence-based practice and knowledge development in elderly care. The project was funded by Forte; The Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, dnr. 2011-1140.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anttonen A, Meagher G 2013 Mapping marketisation: Concepts and goals. Marketisation in Nordic eldercare. In: Szebehely M, Meagher G (Eds.). Marketisation in Nordic Eldercare. A Research Report on Legislation, Oversight, Extent and Consequences. Department of Social Work, Stockholm University, Stockholm.

- Baatiema L, Otim ME, Mnatzaganian G, de Graft Aikins A, Coombes J, Somerset S 2017 Health profesionals’ views on the barriers and enablers to evidence-based practice for acute stroke care: A systematic review. Implementation Science 12: 74. 10.1186/s13012-017-0599-3.

- Björk Brämberg E, Nyman T, Kwak L, Alipour A, Bergström G, Schäfer Elinder L, Hermansson U, Jensen I 2017 Development of evidence-based practice in occupational services in Sweden: A 3-year follow-up of attitudes, barriers and facilitators. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health 90: 335–348. 10.1007/s00420-017-1200-8.

- Boström AM, Ehrenberg A, Gustavsson J, Wallin L 2009 Registered nurses’ application of evidence-based practice: A national survey. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 15: 1159–1163. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2009.01316.x.

- Boström AM, Sommerfeld DK, Stenhols AW, Kiessling A, Manalo E 2018 Capability beliefs on, and use of evidence-based practice among four health professional and student groups in geriatric care: A cross sectional study. PLoS One 13: e0192017. 10.1371/journal.pone.0192017.

- Brodin H, Peterson E 2019 Doing business or leading care work? Intersections of gender, ethnicity and profession in home care entrepreneurship in Sweden. Gender, Work, and Organization 26: 1640–1657. 10.1111/gwao.12402.

- Carlfjord S, Nilsing-Strid E, Johansson K, Holmgren T, Öberg B 2019 Practitioner experiences from the structured implementation of evidence-based practice in primary care physiotherapy: A qualitative study. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 25: 622–629. 10.1111/jep.13034.

- Chapman L 2012 Evidence-based practice, talking therapy and the New Taylorism. Psychotherapy and Politics International 10: 33–44. 10.1002/ppi.1248.

- Charmaz K 2006 Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage.

- Clarke A 2005 Situational analysis – grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Clarke A, Friese C, Washburn R 2015 Situational analysis in practice: Mapping research with grounded theory. Walnut Creek CA: Left Coast Press Inc.

- Clarke A, Keller R 2014 Engaging complexities: Working against simplification as an agenda for qualitative research today. Forum: Qualitative Social Research 15: 1.

- Dahlgren L, Emmelin M, Graneheim U, Sahlén KG, and Winkvist A 2019 Qualitative methodology for international public health 3rd. Umeå: Umeå International School of Public Health: Umeå University.

- Dannapfel P 2015 Evidence-based practice in practice. exploring conditions for using research in physiotherapy. Dissertation Uppsala University: Uppsala.

- Dellve L, Williamsson A, Strömgren M, Holden RJ, Eriksson A 2015 Lean implementation at different levels in Swedish hospitals: The importance for working conditions and stress. International Journal of Human Factors and Ergonomics 3: 235–253. 10.1504/IJHFE.2015.073001.

- Di Censo A, Guyatt G, Ciliska D 2005 Evidence based nursing: A guide to clinical practice. London: Elsevier Health Sciences, Mosby, Inc.

- Ehrenberg A, Gustavsson P, Wallin L, Boström AM, Rudman A 2016 New graduate nurses’ developmental trajectories for capability beliefs concerning core competencies for healthcare professionals: A national cohort study on patient-centered care, teamwork, and evidence-based practice. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 13: 454–462. 10.1111/wvn.12178.

- Enberg B 2009 Work Experiences among Healthcare Professionals in the Beginning of Their Professional Careers: A Gender Perspective. Dissertation, Umeå University, Umeå.

- Fosket JR 2015 Situating knowledge. Clarke A, Friese C, Washburn R Eds. Situational analysis in practice: Mapping research with grounded theory, 198. Walnut Creek CA: Left Coast Press, Inc.

- Foucault M 1988 Power/Knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. USA Inc: Random House.

- Fristedt S, Areskoug-Josefsson K, Kammerlinf AS 2016 Factors influencing the use of evidence based practice among physiotherapists and occupational therapists in their clinical work. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences Practice 14: 7.

- Haraway D 1988 Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies 14: 575–599. 10.2307/3178066.

- Harding K, Porter J, Horne-Thompson A, Donley E, Taylor N 2014 Not enough time or a low priority? Barriers to evidence-based practice for allied health clinicians. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions 34: 224–231. 10.1002/chp.21255.

- Hayes LJ, Moore S 2017 Care in a time of austerity: The electronic monitoring of care workers’ time. Gender, Work, and Organization 24: 329–344. 10.1111/gwao.12164.

- Haynes RB, Devereaux PJ, Guyatt GH 2002 Clinical expertise in the era of evidence based medicine and patient choice. ACP Journal Club 136: A11–14.

- Heiwe S, Kajermo K, Tynni-Lenné R, Guidetti S, Samuelsson M, Andersson I, Wengström A 2011 Evidence-based pracitce: Attitudes, knowledge and behaviour among allied health care professionals. International Journal For Quality In Health Care 23: 198–209. 10.1093/intqhc/mzq083.

- Hood C 1995 The ‘New Public Management’ in the 1980s: Variations on a theme. Accounting, Organizations and Society 20: 93–109. 10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0001-W.

- Isaac I, Francesci A 2008 EBM: Evidence to practice and practice to evidence. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 14: 656–659. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2008.01043.x.

- Johansson B, Fogelberg-Dahm M, Wadensten B 2010 Evidence-based practice: The importance of education and leadership. Journal of Nursing Management 18: 70–77. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2009.01060.x.

- Johansson Y 2018 Skr. Framtidens Äldreomsorg – En Nationell Kvalitetsplan. (The future elderly care – A national plan for quality) (Regeringens skrivelse 2017/2018: 280). https://www.regeringen.se/49ee56/contentassets/faebe5c0bff14b9fb7cd9df7625d2e10/framtidens-aldreomsorg–en-nationell-kvalitetsplan-2017_18_280.pdf.

- Kanter RM 1977 Men and women of the corporation. New York: Basic Books.

- Keisu BI 2017 Dignity: A prerequisite for attractive work in elderly care. Society, Health and Vulnerability 8(Suppl 1): 40–52. 10.1080/20021518.2017.1322455.

- Keisu BI, Öhman A, Enberg B 2016 What is a good workplace?: Tracing the logics of NPM among managers and professionals in Swedish elderly care. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies 6: 27–46. 10.19154/njwls.v6i1.4884.

- Keisu BI, Öhman A, Enberg B 2018 Employee effort - Reward balance and first-level manager trans-formational leadership within elderly care. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences 32: 407–416. 10.1111/scs.12475.

- Lincoln YS, Guba E 1985 Naturalistic Inquiry. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Inc.

- Lindström AC, Bernhardsson S, Copley JA 2018 Evidence-based practice in primary care occupational therapy: A cross-sectional survey in Sweden. Occupational Therapy International 2018: 5376764. 10.1155/2018/5376764.

- Meagher G, and Szebehely M 2013 Marketisation in Nordic Eldercare: A research report on legislation, oversight, extent and consequences. Department of Social Work. 2013, Stockholm University, Stockholm. .

- Meagher G, Szebehely M 2018 Nordic eldercare: Weak universalism becoming weaker? Journal of European Social Policy 3: 294–308.

- Meagher G, Szebehely M, Mears J 2016 How institutions matter for job characteristics, quality and experiences: A comparison of home care work for older people in Australia and Sweden. Work, Employment and Society 30: 731–749. 10.1177/0950017015625601.

- National Board of Health and Welfare 2013 Socialstyrelsen. Evidensbaserad Praktik på Kunskapsguiden.se – Praktisk Vägledning för Verksamheter som Arbetar med att Utveckla en Evidensbaserad Praktik [ Evidence-Based Practice on Kunskapsbanken.se – Practical Guidelines for Developing Evidence-Based Practice].

- Perry L, Bellchambers H, Howie A, Moxey A, Parkinson L, Capra S, Byles J 2011 Examination of the utility of the promoting action on research implementation in health services framework for implementation of evidence based practice in residential aged care settings. Journal of Advanced Nursing 67: 2139–2150. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05655.x.

- Ranci C, Pavolini E 2015 Not all that glitters is gold: Long-term care reforms in the last two decades in Europe. Journal of European Social Policy 25: 270–285. 10.1177/0958928715588704.

- Rudman A, Boström AM, Wallin L, Gustavsson P, Ehrenberg A 2020 Registered nurses evidence-based practice revisited: A longitudinal study in mid-career. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 17: 348–355. 10.1111/wvn.12468.

- Rudman A, Gustavsson P, Ehrenberg A, Boström AM, Wallin L 2012 Registered nurses’ ecidence-based practice: A longitudinal study of the first five years. International Journal of Nursing Studies 49: 1494–1504. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.07.007.

- Sackett DL 1997 Evidence-based medicine. Seminars in Perinatology 21: 3–5. 10.1016/S0146-0005(97)80013-4.

- Schuman CJ 2017 Addressing the Practice Context in Evidence-Based Practice Implementation: Leadership and Climate. Dissertation, University of Michigan, USA.

- Schön DA 2003 The reflective practitioner. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Scurlock-Evans L, Upton P, Upton D 2014 Evidence-based practice in physiotherapy: A systematic review of barriers, enablers and interventions. Physiotherapy 100: 208–219. 10.1016/j.physio.2014.03.001.

- Sirkka M, Zingmark K, Larsson-Lund M 2014 A process for developing sustainable evidence-based occupational therapy practice. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 21: 429–437. 10.3109/11038128.2014.952333.

- Statistics Sweden 2017 Trends and forecasts 2017 population, education, labour market until 2035. Stockholm: SCB, Prognosinstitutet. .

- Statistics Sweden 2018 Statistical news from statistics Sweden 2018-03-28. www.scb.se/en/finding-statistics/statistics-by-subject-area/national-accounts/national-accounts/system-of-health-accounts-sha/pong/statistical-news/system-of-health-accounts-2016/.

- Strandell R 2019 Care workers under pressure: A comparison of the work situation in Swedish home care 2005 and 2015. Health & Social Care in the Community 28: 137–147. 10.1111/hsc.12848.

- Sundberg L 2016 Mind the Gap: Exploring Evidence-Based Policymaking for Improved Preventive and Mental Health Services in the Swedish Health System. Dissertation, Umeå University.

- Tafvelin S, Keisu BI, Kvist E 2020 The prevalence and consequences of intragroup conflicts in women-dominated work. Human service organizations: Management. Leadership and Governance 44: 47–62.

- Theobald H, Luppi M 2018 Elderly care in changing societies: Concurrences in divergent care regimes - A comparison of Germany, Sweden and Italy. Current Sociology Monograph 66: 629–642. 10.1177/0011392118765232.

- Yoder LH, Kirkley D, Mcfall DC, Kirksey K, Stalbaum AL, Sellers D 2014 Staff nurses’ use of research to facilitate evidence-based practice. American Journal of Nursing 114: 26–37. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000453753.00894.29.

- Öhman A 2001 Profession on the Move: Changing Conditions and Gendered Development in Physiotherapy. Dissertation, Umeå University, Umeå.

- Öhman A, Enberg B, Keisu BI 2017 Team social cohesion, professionalism and client-centeredness: Gendered care work, with special reference to elderly care – A mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research 17: 381. 10.1186/s12913-017-2326-9.