ABSTRACT

Purpose

In acute care, effective goal-setting is an essential phase of a successful rehabilitation process. However, professionals’ knowledge and skills in rehabilitee-centered practice may not always match the ways of implementing goal-setting. This study aimed to describe the variation in how acute hospital professionals perceive and comprehend rehabilitee participation in rehabilitation goal-setting.

Methods

Data were collected by interviewing 27 multidisciplinary rehabilitation team members in small groups shortly after rehabilitation goal-setting sessions. A qualitative research design based on phenomenography was implemented.

Results

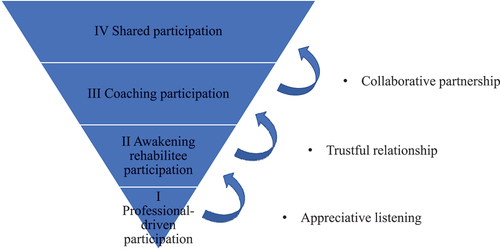

We identified four conceptions of rehabilitee participation, based on four hierarchically constructed categories: 1) Professional-driven rehabilitee participation; 2) Awakening rehabilitee participation; 3) Coaching participation; and 4) Shared participation. These categories varied according to four themes: 1) Use of power; 2) Ability to involve; 3) Interaction process; and 4) Atmosphere. Three critical aspects between the categories were also identified: 1) Appreciative listening; 2) Trustful relationship; and 3) Collaborative partnership.

Conclusion

The study generated new insights into the meaning of rehabilitee participation, as conceptualized in relation to rehabilitation goal-setting and an acute hospital context. The identified critical aspects can be useful for planning and developing continuing professional education (CPE) in rehabilitation goal-setting for professionals.

Introduction

Shared decision-making in rehabilitation goal-setting is becoming increasingly highlighted in contemporary society, also in acute hospital settings (Castro et al., Citation2016). Accordingly, current rehabilitation practice models emphasize a shift away from professional-led approaches toward new patient-centered and inclusive practices that incorporate the views of the patients and their families in addition to those of the professionals (Sjöberg and Forsner, Citation2020). However, in addition to the attained benefits of goal-setting and the new approaches, challenges have also been reported related to implementation in inpatient and acute care settings (Clissett, Porock, Harwood, and Gladman, Citation2013; Lewack, Dean, Siegert, and McPherson, Citation2011).

Successful rehabilitation goal-setting seems to be related to professionals’ personal perspectives on health and disability, their knowledge of patient-centered practice and the level of their practical skills (Parsons, Plant, Slark, and Tyson, Citation2018). Current clinical guidelines suggest that goals should nevertheless be set in collaboration with patients and their families, should be well-defined, specific and challenging, and should also be reviewed and updated regularly (National Health and Medical Research Council, Citation2017; Sugavanam et al., Citation2013). However, incorporating patient-centered goal-setting into clinical goal attainment frameworks such as the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework and Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) can be challenging (Cieza et al., Citation2009). Hence, it is essential that rehabilitation professionals have the up-to-date knowledge and skills required for successful goal-setting, patient-centered care, and the implementation of prevailing clinical frameworks.

For rehabilitation professionals to master a shift from a professional-driven approach toward a patient-centered approach in rehabilitation goal-setting, they must undergo continuing professional education (CPE) on how to enhance patient empowerment and inclusion, and take a more active role in general (Sugavanam et al., Citation2013). Hence, it is equally important for professionals to have CPE in patient participation and patient-centered practice (Mudge, Stretton, and Kayes, Citation2014), as they require CPE in how to educate patients in the pathology of and recovery from their disease (Cameron et al., Citation2018; Rose, Rosewilliam, and Soundy, Citation2017). Moreover, patients’ improved participation requires professionals to encounter patients with dignity and equality (Rose, Rosewilliam, and Soundy, Citation2017; Sugavanam et al., Citation2013). Skills in empathic listening and negotiation, and working in collaborative partnerships can help gain the patient’s trust and enhance their engagement in dialogue (Mudge, Stretton, and Kayes, Citation2014; Rosewilliam et al., Citation2015). However, limited resources, such as short hospital stays and low numbers of available staff, limit the opportunities for institutional rehabilitation (Lewack, Dean, Siegert, and McPherson, Citation2011), which again may have implications for professionals’ opportunities for CPE and shifting toward patient-centered practice, particularly in the early stages of rehabilitation.

A relatively small number of qualitative studies have been conducted on patient participation in rehabilitation goal-setting from the perspective of acute hospital professionals (Lloyd, Roberts, and Freeman, Citation2014; Parsons, Plant, Slark, and Tyson, Citation2018; Rosewilliam et al., Citation2016; Sjöberg and Forsner, Citation2020). Previous studies have identified three types of challenges in patient participation: 1) current goal-setting practices are inconsistent in terms of patient inclusion and collaboration between patients and professionals (Lloyd, Roberts, and Freeman, Citation2014; Parsons, Plant, Slark, and Tyson, Citation2018; Rosewilliam et al., Citation2016; Sjöberg and Forsner, Citation2020); 2) interaction with patients, families and other professionals can be demanding and require extra effort (Lloyd, Roberts, and Freeman, Citation2014; Parsons, Plant, Slark, and Tyson, Citation2018); and 3) professionals need a better understanding of the concept of person-centered care (PCC) and participatory methods in clinical practice (Parsons, Plant, Slark, and Tyson, Citation2018; Sjöberg and Forsner, Citation2020). One previous study illuminates rehabilitation experts’ approaches to rehabilitee participation in goal-setting and proposes four different approaches: authoritative, proposing, supporting, and inclusive (Rinne, Citation2017).

Previous studies have failed to lead to an in-depth understanding of the acute hospital professionals’ conceptions; that is ways of seeing, experiencing, or understanding patient participation in goal-setting which motivated this study. To address this gap, this study aimed to explore the ways of seeing, experiencing, and understanding rehabilitee participation in rehabilitation goal-setting from the perspective of acute hospital professionals. The research question was: “What are acute hospital professionals’ qualitatively different ways of understanding rehabilitee participation in rehabilitation goal-setting?”

In this study, we assumed that when a patient has been diagnosed and achieved medical stability (Frank, Citation2017), and a rehabilitation plan has been established, they become a rehabilitee, an autonomous person whose recovery will be supported by rehabilitation professionals on the basis of their knowledge and skills. As recommended in the guidelines (Rudd, Bowen, Young, and James, Citation2017) we use the term acute hospital setting as the context of rehabilitation goal-setting in the acute phase between 24 hours and 7 days. Accordingly, when referring to the research phenomenon, aim and findings of this study, we apply the term “rehabilitee” and “rehabilitee-centered” instead of “patient” or “patient-centered.” However, when referring to previous studies, we use their original terminology. Therefore, in this article, the use of the terms “patient-centered,” “person-centered,” “client-centered” or “consumer-centered” is determined by the context.

Methods

Study design

In this study, we used a qualitative research design to examine acute hospital professionals’ conceptions of rehabilitee participation in goal-setting (Åkerlind, Citation2012). Each of the 27 multi-disciplinary team members participated in interviews (20 in total) shortly after each rehabilitation goal-setting. The aim of the study was to understand and describe the variation in acute hospital professionals’ conceptions; that is different ways of seeing, experiencing, and understanding rehabilitee participation in rehabilitation goal-setting. Thus, the phenomenon under exploration is rehabilitee participation in goal-setting, as understood and conceptualized by professionals. However, it is the researcher who constitutes and describes the variation between the different ways of seeing, experiencing, and understanding rehabilitee participation, on the collective level (Marton and Pang, Citation2008). The consolidated criteria for qualitative research (COREQ) was used for both designing and reporting the study (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig, Citation2007).

Phenomenographic approach

Phenomenographic methodology commonly focuses on qualitatively different ways of seeing, experiencing and understanding or conceptualizing the phenomenon under exploration to illustrate the variation in the phenomenon (Åkerlind, Citation2012). Phenomenography was originally developed in educational research to investigate variations in educational phenomena such as how students learn and understand conceptions (Marton and Booth, Citation2009). The methodology has since been used widely in health research, to determine how professionals perceive their practice, for example (Holopainen et al., Citation2022; Jäppinen, Hämälinen, Kettunen, and Piirainen, Citation2020; Larsson, Liljedahl, and Gard, Citation2010; Sjöberg and Forsner, Citation2020).

Phenomenography argues that there may be only one world, but individuals perceive and apprehend this world differently, formulating different conceptions of it, depending on their socio-cultural backgrounds (Åkerlind, Citation2012). Phenomenography not only examines what constitutes a way of experiencing, seeing or understanding something; it also explores the differences between ways of experiencing the same thing, and how these differences evolve in terms of descriptive categories and their logical relationships (Marton and Pang, Citation2008). Phenomenography thus aims to determine the structure of experiencing and understanding phenomena, based on qualitatively different meanings, which can be characterized by the same set of variation. This framework assumes that the varying meanings are logically related to each other (Marton and Pang, Citation2008). Accordingly, phenomenography aims to describe the relationships between the set of dimensions of this variation, which is often described as hierarchical so that the descriptive categories forming the structure of the phenomenon expand from the narrowest to the more complex categories of understanding (Åkerlind, Citation2008, Citation2012). The aim of the study was thus to investigate the target phenomenon, namely rehabilitation professionals’ ways of experiencing rehabilitee participation in goal-setting; and to distinguish the aspects that are critical for expanding the awareness of the target phenomenon into a more complex, wider understanding.

Participants

In this study, we focused on health care professionals of multidisciplinary rehabilitation teams in one acute hospital in Finland. We recruited 27 professionals (24 females, 3 male), consisting of nurses (n = 14), occupational therapists (n = 4), and physiotherapists (n = 9). The participants had worked an average of 18 years (range 2 to 38 years) in their profession and an average of 10 years (1 to 25) in an intensive rehabilitation unit. Occupational therapists participated in goal-setting situations more often than other professionals due to their limited number at the hospital. Doctors and speech therapists were asked to attend but they declined, due to time constraints.

The study was launched in the spring of 2015, after the rehabilitation professionals had been provided with brief training on rehabilitation goal-setting at the hospital, consisting of two three-hour sessions. However, six professionals who participated in the study failed to attend the preliminary training due to absence from clinical work. The aim of the training was to improve the professionals’ knowledge of and skills in goal-setting, such as the implementation of the GAS method and participatory methods (e.g. setting meaningful goals related to GAS), the ICF framework, and teamwork. However, this study did not aim to evaluate its effect and the training was considered a contextual factor only. After receiving ethical approval for the study from the Hospital District Ethics Committee (24 June 2014), the senior physician and the director of the rehabilitation ward informed the professionals of the forthcoming study.

Data collection

The data were collected through group interviews (originally in Finnish) of 27 rehabilitation professionals by the same researcher-interviewer (first author), using in-depth, semi-structured interview techniques (Appendix). The participants were interviewed in small groups of three professionals (i.e. occupational therapist, physiotherapist, and nurse). The interviews took place in an acute hospital setting, in a private meeting room. The aim of the interviews was to allow the professionals to describe the phenomenon of interest as openly as possible, as they comprehended it, without leading them with questions. At the beginning of each interview, the interviewer asked all the participants the same question: “Please tell me about your experiences, views and opinions of rehabilitee participation in the goal-setting situation.” Open-ended questions were included to elicit additional and unexpected aspects of the experience and to ask for further clarification when required. Throughout the interviews, the professionals were encouraged to reflect on their own actions in the goal-setting situations. The group interviews were first audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. As it was possible to identify each participant by their name and profession, the researcher later removed all names from the data, substituting them with pseudonyms. The interviews lasted an average of 49 minutes (range 25 to 77 min) and culminated in 16 hours and 26 minutes of recorded data (Åkerlind, Citation2008). The transcribed data consisted of 254 pages (Times New Roman 12, spacing = 1.5).

Data analysis

As stated above, phenomenography is a qualitative research approach that aims to qualitatively describe different understandings of phenomena and to demonstrate how these different understandings are related to each other (Åkerlind, Citation2012, Citation2018). The outcome of phenomenographic research is thus a set of related categories of description of the phenomenon under exploration, known as the “outcome space,” which illuminates how the categories are internally related (Åkerlind, Citation2018; Marton and Pang, Citation2008). Although the study process begins with the analysis of individual participants’ descriptions of the phenomenon, the goal is to create a description of the collective view, generalizable across different situations in which the same phenomenon occurs (Marton and Pang, Citation2008). Hence, the end result in a phenomenographic study is the outcome space, which represents a collective level of the experienced phenomenon (Åkerlind, Citation2012; Marton and Booth, Citation2009); in this case, a conception of professionals’ collective experience of rehabilitee participation.

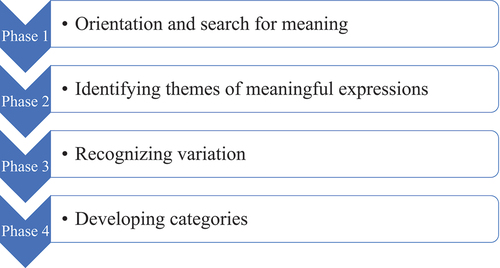

In the first phase of the phenomenographic analysis (i.e. orientation and search for meaning), the first author, with a high degree of openness to possible meanings (Åkerlind, Citation2012) read and re-read all the transcripts and listened to the audiotapes several times, highlighting and making notes of meaningful expressions in a Word document. The aim at this point was to identify the professionals’ views and understandings of rehabilitee participation in rehabilitation goal-setting. During the second phase of the analysis (i.e. identifying themes of meaningful expressions), the first author, within a frame of openness and repetitive readings, rearranged and grouped the meaningful expressions into preliminary themes after systematically comparing and contrasting them, in order to identify similarities and differences in the professionals’ conceptions (Åkerlind, Citation2012; Marton and Booth, Citation2009). The next phase of the analysis (i.e. recognizing variation) was performed in collaboration with the research team by searching for variation within the initial categories based on constructive but critical debate. Two of the research team members were experienced qualitative researchers. In the fourth phase of the analysis (i.e. developing categories) the key “candidate” themes were expanding awareness and highlighting the critical differences of the professionals’ conceptions, again in collaboration with the team, and were compared, contrasted, and grouped into descriptive categories of the phenomenon, forming the “outcome space.”

The four categories of description of the target phenomenon varied to form a hierarchical, logical, and structural whole (Åkerlind, Citation2008). The categories represent an expanded understanding of the phenomenon; the wider categories were more complicated than the previous categories (Åkerlind, Citation2018). During the elaboration process, the researcher, through constant discussion with the research team, aimed to establish consistency between the original data and the research findings and to minimize the influence of their own interpretations (Åkerlind, Citation2012). This process continued until a consistent set of categories had emerged and the main categories were identified.

During the analysis process, we also identified themes of expanding awareness, conveying the critical differences between the descriptive categories. To be regarded as a theme of expanding awareness, this had to occur in all the categories, reflecting the variation in progressing from a less complex understanding to a more developed one (Åkerlind, Citation2012). presents the process of phenomenographic data analysis. Phases 1 and 2 were performed by the first author, and Phases 3 and 4 were completed together with the research team.

Results

Categories of descriptions and themes of rehabilitee participation

The main outcome of the phenomenographic analysis was a hierarchically structured set of four descriptive categories of the target phenomenon: I) Professional-driven rehabilitee participation; II) Awakening rehabilitee participation; III) Coaching participation; and IV) Shared participation. The categories were based on four themes of expanding awareness, conveying the critical differences identified within the categories: 1) Use of power; 2) Ability to involve; 3) Interaction process; and 4) Atmosphere. The structural relationships between these qualitatively distinct categories, which describe variation in understanding the target phenomenon, express a hierarchy of ascending complexity, according to which more developed understandings are inclusive of less developed ones ().

Table 1. Categories of understanding rehabilitee participation in goal-setting: Four categories, described in terms of four themes of expanding awareness and critical differences.

We next present and discuss these categories, using quotes to elucidate their meaning. All the original quotes have been translated into English without stylistic corrections. Please note: All quotations use the following abbreviations: PT = physiotherapist; OT = occupational therapist; and N = nurse, and they contain the page number of the transcript in which they are situated.

Category I: professional-driven rehabilitee participation

The first category describes the conception of rehabilitee participation as a professional-driven approach to goal-setting; that is, the professional leads the rehabilitation goal-setting situation throughout. Within this category, the use of power theme manifested itself as prompted rehabilitee responsibility. The professionals reported persuading or even pressuring the rehabilitees, and afterward reflecting on whether they had used too much power over the rehabilitee and not allowed them to decide on their own goals. The professionals also faced challenges when prompting the rehabilitee to express their preferences and wishes in order to formulate their own goals in their own words.

“In that way it (goal-setting) was challenging, and I felt, can I still pressure the rehabilitee in this, or what. I felt I was pressuring … I felt a bit like, do I have to say them (goals) myself and relieve the rehabilitee, because it was beginning to be so difficult.” (OT2, p. 1).

The second theme (i.e. ability to involve) conveyed itself as the professionals’ lack of ability to consistently involve the rehabilitee in the goal-setting situation. The professionals reported incidents in which they only considered goals related to mobility suitable for rehabilitation goal-setting, explaining how this differed from the goals proposed by the rehabilitees. Some of the professionals reported having difficulties setting the goals in accordance with the expected GAS framework, or acknowledging goals related to everyday activities, such as fishing or chopping firewood, as suitable. Accordingly, their conception of setting goals together with the rehabilitees on the ICF level of participation presented as narrow and superficial.

“Well, when I [nurse] thought that if I have to set fishing as the goal, then I wasn’t thinking of it as a goal, I was thinking all the time that only exercise and other things (are good goals).” (N6, p. 2).

In this category, the interaction process theme conveyed the professionals’ lack of ability to involve the rehabilitees in goal-setting. The participants described situations in which they felt that the goal-setting was becoming professional-led, even if they acknowledged that the rehabilitees were supposed to take part in identifying meaningful goals for themselves. The professionals also reported difficulties in identifying the rehabilitees’ expectations and aims. This emerged as being specifically related to goal-setting situations in which rehabilitees had difficulties in setting and expressing realistic goals. According to the professionals, these rehabilitees needed guidance and encouragement to express their opinions when setting achievable goals as part of the rehabilitation process. However, the professionals also reported that they themselves lacked abilities to help the rehabilitees express and formulate their own goals. They also sometimes felt that the rehabilitees thought the professionals did not appreciate their opinions.

“ … He [rehabilitee] said that what he says isn’t good enough.” (PT7, p. 1). “That that’s how he [rehabilitee] understood it, when we [professionals] tried to dig it out of him, so that he would say it [the goal] himself, I mean the goals and different things. So, he understood it a little differently, that even though he tried to say something, it wasn’t good enough for us [professionals].” (OT2, p. 2).

In the fourth theme (i.e. atmosphere) as conveyed in the first category, the professionals acknowledge feeling confused about trying to explain the meaning of realistic and attainable rehabilitation goals to their rehabilitees. The participants reported that their rehabilitees had difficulties in understanding which goals were realistic and/or achievable. Sometimes the goals of the professionals, the rehabilitees, and their relatives did not match; this happened when the rehabilitee’s relatives seemed to react negatively to the rehabilitee’s ideas of realistic goals and offered their own goals instead. This confused the situation. The professionals expressed that in these cases, they felt inclined to prioritize their expertise over the rehabilitees’, and relatives’ perspectives, especially when considering the goals unrealistic and/or unattainable.

‘ … I [professional] was thinking that the daughter was quite strong and brought up writing. But was it really the rehabilitee’s own wish? I [professional] don’t think he brought it up unprompted, even though he took it up.’ (N8, p. 3). ‘It [driving the car] came as a great surprise to us [professionals]or I think that all of us were little bit confused at that moment … We had just talked about using the hand.’ (PT7, p. 3). ‘The wife’s presence at the goal setting was a bit negative.’ (N12, p. 17).

Category II: awakening rehabilitee participation

The second category illuminates a shift in the professional’s understanding of rehabilitee participation. Within this category, the use of power theme presented itself as anticipation of a more rehabilitee-centered approach to goal-setting. The participants highlighted the significance of appreciative listening and understanding of the rehabilitees, supporting, and offering them opportunities to express their opinions.

“ … Quite, in my [professional] opinion we let him speak and encouraged him to express his own opinions. And then, when he used humor, we joined in. Anyway, this showed that we respected his humanity.” (PT1, p. 7). “We appreciated his views” (PT1, p. 8). “So, we asked what you [rehabilitee] think and yes. He had opportunities.” (O2, p. 8). “And certainly, with this body language, that we sat in peace, and we gave him time and space.” (PT1, p. 8).

The focus in the second theme (i.e. ability to involve) was on how professionals apprehended the rehabilitee’s involvement in the goal-setting situation. The participants highlighted the importance of knowing the rehabilitee as a person and their needs and preferences, as well as their wish to help the rehabilitee in their goal-setting. The importance of prior preparations and discussions with the rehabilitee and relatives were also highlighted.

“Well, you [professional] have to know the rehabilitee anyway, if you haven’t seen their daily routines, it’s difficult to think of the rehabilitee as a person. It felt that the better you knew the rehabilitee, the easier it was to start thinking, or then, in their specific case, to help, where to start from … ” (N12, p. 13).

In the interaction process theme, as pronounced in this category, the professionals aimed for genuine interaction; that is, openness and authenticity in the communication between the rehabilitees and professionals. The participants described the importance of being genuinely involved and interested in the rehabilitees’ preferences; perceiving this as facilitating more interactive communication, in which both parties conversed in turns and no one spoke at the same time as anybody else.

“At least for my own part I [physiotherapist] can say it was being genuinely involved and interested in the rehabilitee’s own thoughts about their goal. And asking extra questions to show interest.” (PT4, p. 9)

In the atmosphere theme, the professionals’ focus was on appreciative encountering of rehabilitees. The professionals highlighted the significance of the time given to the rehabilitees and all the parties involved in the goal-setting situation. They described how all the parties listened to each other’s views, considered goals that would be meaningful and realistic for the rehabilitees, and felt that the group was permissive. The professionals addressed the value of a peaceful goal-setting situation having a positive atmosphere.

“ … He himself [rehabilitee] can say what (goals) walks he could do and think about which block to walk around and things like that. And there was still some realism in it.” (PH5, p. 2). “I [physiotherapist] think this

atmosphere was relaxed, that everyone dared say what they were thinking, sympathetic and easy-going.” (PT1, p. 7). “Exactly that, that the rehabilitee was given time to talk about things in peace.” (N12, p.7).

Category III: coaching participation

The third category describes the conception of rehabilitee participation as coaching participation; that is, the professionals sought to support the rehabilitees as the experts of their own goals. Within this category, the use of power theme illuminates increased rehabilitee responsibility; the professionals respecting the rehabilitee as a person and an expert in their own life, who takes responsibility for their own goals and actions. The participants emphasized the significance of setting rehabilitee-centered rehabilitation goals that were relevant to the rehabilitees; linked to their own interests and activities in their everyday lives. The professionals also described themselves as encouraging their rehabilitees to become more actively involved by asking reflective questions and thus increase the rehabilitees’ responsibility for forming their own goals.

“Well, I [occupational therapist] don’t know about power and responsibility, but these questions of ours. And what he [rehabilitee] himself could do. And how. That’s where he took responsibility, he could use his own power for this … That from here onwards we [professionals] asked some defining questions and made suggestions. Then he [rehabilitee] built from these, thought about what the goals were.” (OT1, p. 11).

The focus in the ability to involve theme is on the professionals’ trust in rehabilitee involvement. The professionals expressed that placing the rehabilitee in the center of the goal-setting highlighted the significance of allowing the rehabilitees and relatives to express their own thoughts and ideas, and to create individual, unique goals. The professionals also emphasized the importance of having enough time for goal-setting situations; not rushing.

“I have a feeling, that yes, we [professionals and rehabilitees] were on the same page, that yes, in a way were coloring the same flower.” (N9, p. 23). “Yes, and in a way, what I (occupation therapist) think, that here we are like this, when we have made the time (for goal-setting) we aren’t in any hurry … I feel that the rehabilitee can bring up these things (goals). (OT1, p.23-24).

In the interaction process theme, the focus in the third category was on respectful collaboration between the professional and the rehabilitee. The professionals perceived the role of trust and confidentiality in the situation as important. In the creation of trust, the participants highlighted the significance of coaching methods, such as insightful reflection, mindful listening and asking reflective questions, and giving the rehabilitees time to reflect on their own thinking, and to express their aims, wishes and goals.

“Well, yes, he [rehabilitee] got some space to talk about his thoughts, and by listening and what I thought, the atmosphere was relaxed … And yeah, that the questions were directed at him and in my opinion that kind of respect could be seen.” (PT1, p. 6).

In the atmosphere theme, the professional’s focus, in the rehabilitation goal-setting situation, was on rehabilitee empowerment. The professionals highlighted the importance of an open and safe atmosphere in which the rehabilitees would feel free to express their own thoughts and what was meaningful to them.

“At least, being relaxed, that’s one thing. And, well, questions about the things that were important to him [rehabilitee] and what’s come up earlier. Bringing precisely these up.” (PT4, p. 9). “In my opinion too [professional]. It was this that liberated him and this kind of trusting atmosphere, so you can ask and do and say whatever … ” (N3, p.9).

Category IV: shared participation

The fourth and widest category describes rehabilitee participation as shared participation; here the focus is on partnership and mutual involvement of the rehabilitee and the rehabilitation professional. Within this category, the use of power theme conveyed itself as shared responsibility; that is, the rehabilitees and the professionals being equally responsible for rehabilitation goal-setting. The participants acknowledged the significance of forming equal relationships based on mutual respect and two-way communication between the rehabilitee and the professional, which enables the rehabilitee to take responsibility for their own rehabilitation goals.

“But, yes, my [nurse] opinion is that he [rehabilitee] has the power and responsibility, for example, responsibility for what to do here, in my opinion the responsibility was his … we talked a bit about what measures are used now. But in my opinion, he realized that to get to the end he has to do something, I think that it became clear.” (N10, p. 9).

The second theme, ability to involve, emerged as mutual involvement, highlighting the significance of active collaboration and decision-making being shared between the rehabilitees and the rehabilitation professionals. The participants indicated that frequent participation in goal-setting situations had helped them acknowledge the importance of open dialogue and collaborative communication with their rehabilitees.

“I myself [professional] at least think that someone more active can really think better about these goals (after a few goal-setting situations), somehow more broadly, and not so simply and in my opinion the process approach feels good and sensible … Perhaps it somehow suits the rehabilitee’s life better …, that we understand what everything means in this goal-setting process.” (N12, p. 13).

In the theme of interaction process, the focus in the fourth category was on mutual but rehabilitee-centered interaction, indicating a true partnership between rehabilitees and professionals. This kind of partnership requires the rehabilitee’s needs and aspirations to drive the rehabilitation goal-setting process. The professionals expressed their willingness to support the rehabilitees and highlighted the importance of dialogue in the active engagement and mutual relationships of all parties.

“Yes, we asked her [rehabilitee’s] opinion, I [physiotherapist] believe, when those things were written down (on the wall), yes she was there deciding then.” (PT1, p. 4). “In my opinion the rehabilitee was at the center, and we helped her set her goals.” (N4, p.4).

In the atmosphere theme, the focus was on respectful and confidential communication between participants and valuing the presence of all parties in the rehabilitation goal-setting situation. The participants highlighted the fact that the rehabilitees were equally respected and considered experts on their own life situation and were treated as equals in the multi-professional team group in the goal-setting situation.

“The rehabilitee’s role IS different because he’s the one who says and brings things up. He was sort of the expert, and we were the ones who knew what’s supposed to happen (set a goal) during this hour, so then we started scaling.” (OT1, p. 1).

During category development we also identified three critical aspects in the four categories. These aspects can be envisioned as steps in expanding the awareness of the professionals (). The first step from Category I to II illuminated a shift in the professional’s understanding of the anticipation of rehabilitee-centered goal-setting; prompting the professional to listen to the rehabilitee. The second step from Category II to III reflected the professionals’ effort to create a trustful relationship with the rehabilitee; that is, acknowledgment of the rehabilitee’s opinions and expectations and taking them into account. The last step from Category III to IV conveyed the creation of collaborative partnerships: professionals’ understanding of the significance of equal participation and mutual responsibility between professionals and rehabilitees.

Discussion

Based on the data, we identified four descriptive, expanding categories that illuminated the target phenomenon at a collective level. These categories reflected the acute hospital professionals’ conceptions of rehabilitee participation in rehabilitation goal-setting, from the narrowest to the widest; that is, from professional-driven rehabilitee participation to shared participation. We also identified four themes of expanding awareness that conveyed the critical differences among the descriptive categories, which are essential for understanding the nature of the phenomenon in more depth.

The phenomenon of rehabilitee participation in goal-setting, as described in the study, reflects the aims proposed in the ecological approach, used in a variety of rehabilitation and health promotion programs and participatory frameworks. It sees the rehabilitee/client as an active participant and decision-maker in their own rehabilitation process (Mudge, Stretton, and Kayes, Citation2014; Rosewilliam, Roskell, and Pandyan, Citation2011; Vaz et al., Citation2017). In this framework, the professional needs to see the rehabilitee as an individual person, inseparable from their everyday life and what is meaningful to them, and must take this into account in their practice, including rehabilitation goal-setting. Additionally, the incorporation of the ecological model might provide a more holistic approach to rehabilitation goal-setting practice and help deepen the understanding of the complexity of its application and provide a better basis for the implementation of the rehabilitee-centered approach in clinical practice (Lakhan and Ekúndayò, Citation2013). The frame of the biopsychosocial model of health and disability also highlights similar aims (Cameron et al., Citation2018; Larsson, Liljedahl, and Gard, Citation2010; Wade and Halligan, Citation2017).

Our findings bear similarities to those of previous research, but they also differ. Three of the four descriptive categories found in this study present similar features to the findings of Larsson Liljedahl, and Gard (Citation2010) and resonate with context-similar studies on rehabilitee/client role and involvement in the rehabilitation process (Cameron et al., Citation2018; Larsson et al., Citation2018). However, we further identified an additional descriptive category (i.e. awakening rehabilitee participation) which conveys a shift in the professionals’ understanding of anticipation of rehabilitee participation, appreciative listening, and acknowledgment of the rehabilitee-centered approach. This shift in expanding awareness may have significant implications for practice, particularly when considered as a basis for planning and implementing continuous education for rehabilitation professionals and seeking to improve rehabilitee participation in rehabilitation goal-setting.

Another shift in the professionals’ understanding that we found in this study illustrated the endeavor to establish trustful relationships with rehabilitees and to invite them to participate in goal-setting. This resonates with a study by Mudge, Stretton, and Kayes (Citation2014) in which professionals highlighted the significance of open, genuine communication between rehabilitees and professionals. Also in line with previous studies, our findings suggest that professionals may perceive their communication skills as inadequate (Rosewilliam et al., Citation2016; Sjöberg and Forsner, Citation2020; Solvang and Fougner, Citation2016) specifically in goal-setting situations with rehabilitees who have difficulties in expressing realistic goals. Furthermore, the professionals in this study perceived themselves as setting goals for rehabilitees according to their own expertise, offering rehabilitees limited opportunities to participate, which again is in line with previous findings (Shier, Citation2001).

The third shift in the professionals’ understanding of rehabilitee participation discovered in this study illuminated the expanding awareness of the significance of collaborative partnerships and communication between professionals and rehabilitees. This is in harmony with previous findings that highlight the significance of understanding the life situation of the rehabilitees, if the aim is to implement rehabilitee-centered practice in hospital care (Mudge, Stretton, and Kayes, Citation2014; Sjöberg and Forsner, Citation2020; Solvang and Fougner, Citation2016). In this study, the professionals sometimes perceived the involvement of the rehabilitees’ family members in rehabilitation goal-setting as creating difficulties, as reported also in other studies (Parsons, Plant, Slark, and Tyson, Citation2018; Smit et al., Citation2019). Therefore, rehabilitation-specific communication skills training is an important aspect of rehabilitee-centered practice and professional education (Cameron et al., Citation2018).

The widest category of ways in which to understanding rehabilitee participation phenomenon emerged in the study as shared participation, highlighting the significance of mutual involvement and shared responsibility as well as the formation of equal relationships between professionals and rehabilitees in rehabilitation goal-setting. This is concordant with findings reported in another study (Truglio-Londrigan and Slyer, Citation2018). Our results, however, indicate that shared participation may not be easily achieved, as it was meaningfully related to the identified shift toward acknowledgment of the rehabilitees’ opinions and expectations, sometimes going against their own professional judgment, which is not easy. This resonates with previous studies related to the development of professionals’ understanding and skills in partnership with those involved in rehabilitation (Clissett, Porock, Harwood, and Gladman, Citation2013; Mudge, Stretton, and Kayes, Citation2014). Our findings also address the significance of mutual respect between professionals and rehabilitees and their family members as a key aspect of shared participation; an aspect that needs better acknowledgment in rehabilitation goal-setting education and practice.

Recommendations for future practice

The results of the study contribute to deepening the understanding of the target phenomenon – the qualitatively different ways of understanding rehabilitee participation in rehabilitation goal-setting in an acute hospital context. The critical aspects identified in the study can be used for planning and implementing continuing education for professionals to improve rehabilitee-centered practice and rehabilitee participation in acute hospital care. In addition, the critical aspects, in terms of the “steps” toward expanding the awareness of rehabilitee participation, can be beneficial for professionals’ self-reflection and identifying their own understanding of rehabilitee participation. However, the critical aspects identified in this study are not highlighted as the final outcomes portrayed in the ecological and ICF frameworks of rehabilitation. Further advancement of rehabilitee-centered practices is required at multiple levels and from multiple perspectives, including societal, organizational, and multidisciplinary team levels/perspectives.

We suggest that continuing professional education can be a way in which to help rehabilitation professionals develop meaningful, effective goal-setting practices and a shared understanding and language between professionals and rehabilitees. Furthermore, we propose that rehabilitation professionals need adequate training in rehabilitation and goal-setting-specific communication skills to help them feel better equipped for the challenges they may face in rehabilitation practice. However, this needs to be implemented through collaboration between all partners participating in rehabilitation goal-setting. The critical aspects identified in this study may help in this.

Finally, more research is needed from multiple perspectives to further understand rehabilitee participation in acute hospital settings, and how it can be advanced in the context of rehabilitation and professional education and practice, also on the societal level. Future studies could further explore rehabilitees and professionals’ conceptions of participatory methods, and the use of rehabilitee-centered approaches in general. In addition, more research is needed on the lived experiences of the phenomenon of participation from the perspective of the rehabilitees and other professionals.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study was its adequate number of participants in terms of information power for qualitative studies (Malterud, Siersma, and Guassora, Citation2016). Our data consisted of several small-group interviews (20 in total) of 27 professionals, which can be considered large enough for a phenomenographic analysis. A limitation of the study was that physicians and speech, and language therapists could not participate and therefore their voices were not heard. The first author, who conducted the interviews, had earlier experience in qualitative research and interviewing, and had over 20 years of experience in neurological physiotherapy. In terms of researcher’s reflexivity, the first author used her written preconceptions as a reflective tool to bracket earlier conceptions. To increase the trustworthiness of the results we used the authentic quotations of the professionals. The results were also discussed systematically during the process within the research group. The multidisciplinary nature (i.e. social and public policy, gerontology, health sciences, and physiotherapy) of the research group improved the quality of the study. Another limitation was that this was a context-limited study, carried out in the Finnish health care system in one acute hospital, and the knowledge gained is only applicable to context-similar situations. However, the transparency of the research process supports the possibility of transferring the qualitative study protocol to other rehabilitation contexts with different treatment procedures and working cultures. Future studies can take this into account.

Conclusions

The study generated new insights into the meaning of rehabilitee participation, as conceptualized in relation to rehabilitation goal-setting and an acute hospital context. Our findings communicated four descriptive, hierarchically structured categories of ways of understanding rehabilitee participation. Three steps were also identified, illuminating the critical aspects between the categories: 1) appreciative listening; 2) trustful relationship; and 3) collaborative partnership.

These steps of expanding awareness can be seen as essential for understanding the target phenomenon in more depth. The steps may also have significant implications for practice; for example, when planning continuous education for rehabilitation professionals and seeking to improve rehabilitee participation and the implementation of rehabilitee-centered goal-setting in acute hospital contexts. Health care experts at all levels (i.e. society, organization, multidisciplinary team, and professional) need to ensure the implementation and enhancement of a rehabilitee-centered approach in practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Central Finland Health Care District for giving us the opportunity to carry out this study in the Department of Demanding Rehabilitation, to which our thanks are also due. This research and development project was funded by The Social Insurance Institution of Finland and the scientific reporting was funded by Governmental Research Funding of the Kuopio Hospital District.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Åkerlind GS 2008 An academic perspective on research and being a researcher: An integration of the literature. Studies in Higher Education 33:17–31. 10.1080/03075070701794775.

- Åkerlind GS 2012 Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. Higher Education Research and Development 31:115–127. 10.1080/07294360.2011.642845.

- Åkerlind GS 2018 What future for phenomenographic research? On continuity and development in the phenomenography and variation theory research tradition. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 62:949–958. 10.1080/00313831.2017.1324899.

- Cameron LJ, Somerville L, Naismith CE, Watterson D, Maric V, Lannin N 2018 A qualitative investigation into the patient-centered goal-setting practices of allied health clinicians working in rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitaiton 32:827–840. 10.1177/0269215517752488.

- Castro EM, Van Regenmortel T, Vanhaecht K, Sermeus W, Van Hecke A 2016 Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Education and Counseling 99:1923–1939. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.026.

- Cieza A, Hilfiker R, Chatterji S, Kostanjsek N, Üstün BT, Stucki G 2009 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health could be used to measure functioning. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 62:899–911. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.019.

- Clissett P, Porock D, Harwood RH, Gladman JR 2013 The challenges of achieving person-centred care in acute hospitals: A qualitative study of people with dementia and their families. International Journal of Nursing Studies 50:1495–1503. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.03.001.

- Frank A 2017 The latest national clinical guideline for stroke. Clinical Medicine 17:478. 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-5-478.

- Holopainen R, Piirainen A, Karppinen J, Linton SJ, O’Sullivan P 2022 An adventurous learning journey. Physiotherapists’ conceptions of learning and integrating cognitive functional therapy into clinical practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 38:309–326. 10.1080/09593985.2020.1753271.

- Jäppinen AM, Hämälinen H, Kettunen T, Piirainen A 2020 Patient education in physiotherapy in total hip arthroplasty patients ’ and physiotherapists ’ conceptions patient education in physiotherapy in total hip arthroplasty patients ’ and physiotherapists ’ conceptions. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 36:946–955. 10.1080/09593985.2018.1513617.

- Lakhan R, Ekúndayò OT 2013 Application of the ecological framework in depression: An approach whose time has come. Andhra Pradesh Journal of Psychological Medicine 14: 103–109.

- Larsson I, Liljedahl K, Gard G 2010 Physiotherapists’ experience of client participation in physiotherapy interventions: A phenomenographic study. Advances in Physiotherapy 12:217–223. 10.3109/14038196.2010.497543.

- Larsson I, Staland-Nyman C, Svedberg P, Nygren JM, Carlsson IM 2018 Children and young people’s participation in developing interventions in health and well-being: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 18:507. 10.1186/s12913-018-3219-2.

- Lewack WM, Dean S, Siegert JS, McPherson KM 2011 Navigating patient-centered goal setting in inpatient stroke rehabilitation: How clinicians control the process to meet perceived professional responsibilities. Patient Education and Counseling 85:206–213. 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.011.

- Lloyd A, Roberts AR, Freeman JA 2014 “Finding a Balance” in involving patients in goal setting early after stroke: A physiotherapy perspective. Physiotherapy Research International 19:147–157. 10.1002/pri.1575.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD 2016 Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research 26:1753–1760. 10.1177/1049732315617444.

- Marton F, Booth S 2009 Learning and Awareness. New York:Routledge.

- Marton F, Pang MF 2008 The idea of phenomenography and the pedagogy of conceptual change. Vosniadou S Ed International Handbook of Research on Conceptual Change 533–559. New York:Routledge.

- Mudge S, Stretton C, Kayes N 2014 Are physiotherapists comfortable with person-centred practice? An autoethnographic insight. Disability and Rehabilitation 36:457–463. 10.3109/09638288.2013.797515.

- National Health and Medical Research Council 2017 Australian Clinical Guidelines for Stroke Management. Stroke Foundation. Accessessed 26 February 2021.: https://www.clinicalguidelines.gov.au/portal/2585/clinical-guidelines-stroke-management-2017.

- Parsons JG, Plant SE, Slark J, Tyson SF 2018 How active are patients in settin goals during rehabilitation after stroke? A qualitative study of clinician perceptions. Disability and Rehabilitation 40:309–316. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1253115.

- Rinne, V 2017; Seniorikuntoutujan osallisuus tavoitteen asettamisprosessissa. Asiantuntijan nakökulma. Master`s Thesis, University of Jyv’skyla Grerontology and Public Health. Master`s Thesis

- Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A 2017 Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling 100:65–75. 10.1016/j.pec.2016.07.030.

- Rosewilliam S, Roskell C, Pandyan A 2011 A systematic review and synthesis of the quantitative and qualitative evidence behind patient-centred goal setting in stroke rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation 25:501–514. 10.1177/0269215510394467.

- Rosewilliam S, Sintler C, Pandyan AD, Skelton J, Roskell CA 2016 Is the practice of goal-setting for patients in acute stroke care patient-centred and what factors influence this? A qualitative study. Clinical Rehabilitation 30:508–519. 10.1177/0269215515584167.

- Rudd AG, Bowen A, Young GR, James MA 2017 The latest national clinical guideline for stroke. Clinical Medicine 7: 154–155. 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-2-154.

- Shier H 2001 Pathways to participation: Openings, opportunities and obligations. Children and Society 15: 107–117. 10.1002/chi.617.

- Sjöberg V, Forsner M 2020 Shifting roles: Physiotherapists’ perception of person-centered care during a pre-implementation phase in the acute hospital setting - A phenomenographic study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 10.1080/09593985.2020.1809042. Online ahead of print 1–11.

- Smit EB, Bouwstra H, Hertogh C, Wattel E, van der Wouden JC 2019 Goal-setting in geriatric rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Rehabilitaiton 33: 395–407. 10.1177/0269215518818224.

- Solvang PK, Fougner M 2016 Professional roles in physiotherapy practice: Educating for self-management, relational matching, and coaching for everyday life. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 32:591–602. 10.1080/09593985.2016.1228018.

- Sugavanam T, Mead G, Bulley C, Donaghy M, Van Wijck F 2013 The effects and experiences of goal setting in stroke rehabilitation - A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation 35: 177–190. 10.3109/09638288.2012.690501.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J 2007 Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19:349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Truglio-Londrigan M, Slyer J 2018 Shared decision-making for nursing practice: An integrative review. The Open Nursing Journal 12: 1–14. 10.2174/1874434601812010001.

- Vaz DV, da Silva PL, Mancini MC, Carello C, Kinsella-Shaw J 2017 Towards an ecologically grounded functional practice in rehabilitation. Human Movement Science 52: 117–132. 10.1016/j.humov.2017.01.010.

- Wade DT, Halligan PW 2017 The biopsychosocial model of illness: A model whose time has come. Clinical Rehabilitation 31:995–1004. 10.1177/0269215517709890.

Appendix

Rehabilitees’ participation in goal setting situation

Participation to decision-making

Identification of all daily activity goal

Things helped goal setting (collection)

Relatives participating to goal setting situation