ABSTRACT

Background and Objective

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a major and growing problem in India. Better knowledge dissemination and implementation of evidence-based practice in Indian physical therapy require a better understanding of approaches to OA (i.e. perceptions of the condition and its management by Indian physical therapists (PTs)) which was the aim of our study.

Design and Method

We used qualitative content analysis to analyze semi-structured interviews with 19 PTs from Maharashtra state, purposefully selected to represent both sexes, different ages and different educational and professional backgrounds.

Findings

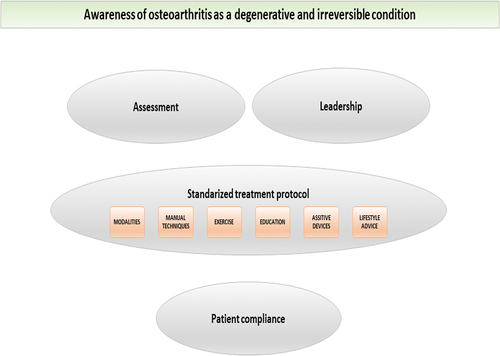

We identified a main overarching theme of meaning, OA as a degenerative and irreversible condition with the four descriptive themes Assessment, Standardized treatment protocol, Leadership and Patient compliance as PTs’ approaches to OA. The descriptive themes indicate that much focus seems to be on pain, physical impairments and biomechanics, with initial treatments being mainly passive. Communication appears to be mainly unidirectional with the PTs instructing the patients, who are expected to comply with PTs instructions. Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) were not mentioned.

Conclusions

Our findings can inform the design of awareness campaigns on evidence-based OA management and increase the understanding of the educational needs of students and PTs in non-Western countries. It is important to recognize that CPGs are mainly based on studies carried out in Western countries and that there are context-specific barriers to implementation in other parts of the world that have large populations.

Background

Globally, the prevalence and incidence rates of osteoarthritis (OA) are high and increasing. The years lived with disability due to OA will increase with increased life expectancy and aging of the global population (Safri et al., Citation2020). This will result in large societal costs (Murphy et al., Citation2018) and make OA a major public health challenge. The majority of people with OA do not receive appropriate management therapies (Runciman et al., Citation2012). Many people with arthritis have comorbidities (Hunter and Bierma-Zeinstra, Citation2019). A shift from imaging based to clinically based diagnostics (Altman et al., Citation1986; Zhang et al., Citation2010) allows for early diagnosis and treatment.

Clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) suggest that OA treatment should focus on self-management education, exercise and weight loss (Bannuru et al., Citation2019; Kolasinski et al., Citation2020). PTs may play a key role in early clinical diagnostics and implementation of the suggested management to prevent individual suffering, irreversible structural change and disability, as well as reduce individual and societal costs. However, many PTs do not seem to comply with CPGs (Battista et al., Citation2021; Zadro, O’Keeffe, and Maher, Citation2019) and barriers have been identified in the community and healthcare systems, among healthcare providers, and at the client level (Egerton et al., Citation2018; Ferreira de Meneses, Rannou, and Hunter, Citation2016; MacKay, Hawker, and Jaglal, Citation2018). Studies in Western countries using qualitative designs have explored aspects of the implementation of OA CPG among PTs, such as knowledge, confidence and learning needs, adherence, as well as the role of leadership (Barton et al., Citation2021; Tang, Pile, Croft, and Watson, Citation2020; Teo et al., Citation2020; Walker, Boaz, and Hurley, Citation2020).

With one of the world’s largest populations and a reported OA prevalence of 22–39% (Chandra, Citation2017) India is no exception to the looming OA epidemic (Luhar et al., Citation2020; Safri et al., Citation2020; Wei et al., Citation2019). Thus, optimal management of the future burden of OA in India is crucial. Indian PT colleges generally offer four and a half-year programs including six months of compulsory rotatory internship for Bachelor of PT (BPT) degrees, additional two-year programs for Master of PT (MPT) degrees, and less frequently PhD programs. Teaching is mainly provided by employed MPTs assisted by MPT students teaching BPT students in a master-apprentice system. The seamless integration of theoretical and practical knowledge, with the college often situated close to a large hospital and with easy access to primary health centers, is provided daily. The focus is on educating PTs for future clinical practice. Research methodology is taught, and the students perform small research projects, mainly with a quantitative design. The culture at PT colleges, like in the entire Indian school system, is quite authoritarian and based on learning facts rather than on reflecting on or questioning the knowledge provided by the highly respected teachers. Similarly, PTs at a clinic rarely challenge the opinions of medical doctors.

Based on the above we believe it is important to explore how well Indian PTs are equipped to play a leading role in early clinical diagnostics and evidence-based management of OA. To our knowledge, no studies with an explorative design have been undertaken in this field. More knowledge on this subject would hopefully enhance the implementation of CPGs, not only in India, but also in other non-Western countries. Our aim was to provide a better understanding of the approaches to OA, i.e., perceptions of the condition as well as its management, among PTs in Maharashtra, India.

Method

Study context and research team

The study was performed in Maharashtra state because several members of our research team have prior experience with PT there. Maharashtra state is situated in Western Central India and is India’s third largest and second most populated state. Mumbai is the capital of Maharashtra, Marathi is the most commonly spoken language, the literacy rate is 82% and over 75% of the population practice Hinduism. The Maharashtra healthcare system includes hospitals and primary health centers run by the government, private medical establishments, as well as a significant number of Ayurveda medical practitioners. Healthcare costs are covered by private insurance, social insurance or a government social welfare program.

All five members of our research team are PTs with PhD degrees and have at least five years of clinical experience working with patients with musculoskeletal conditions. Four of the members are employed at universities as lecturers (ES, KK), principal (SK) or full professor (CHO); one member (CAT) works as a research and development manager in health care. Four members (ES, CAT, KK, CHO) were formally trained in qualitative research methodology during their PhD studies and have since conducted studies with qualitative designs. One member (CAT) has her main research interest in OA, and another member (ES) in studies with qualitative designs. One member (SK) is active in India, and a further three members (CT, KK, CHO) are occasionally active at an Indian PT college.

Design and definition

We used qualitative content analysis because this method is suitable when existing theory or literature on a phenomenon is limited (Hsieh and Shannon, Citation2005). It is generally used in studies that mainly aim to describe a phenomenon, in this case, approaches to hip/knee OA among PTs in Maharashtra, India. Our use of the term OA refers to all hip/knee complaints that fulfil the clinical criteria, with or without radiological changes.

Participants

We purposefully sampled participants to explore the phenomenon and ensure maximum variation of perceptions. The 19 participants varied in terms of sex, age, educational background, specialization areas and professional experience of patients with unspecific hip/knee complaints and OA of the hip/knee, from rural to metropolitan areas, as well as the PTs’ own levels of physical activity ().

Table 1. Characteristics of the 19 participating physical therapists.

No formal ethical approval was required for this study, but it was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. We obtained permission to conduct the interviews from all the participants, as well as from their employers. Regarding risk-benefit, we considered the risk of this study to be minor. We treated all data confidentially and stored them in secure locations that were only accessible to members of our research team. The identity of the study participants is indicated by identification numbers, for which we stored the key separately from the databases. We report our results on a group level, and it is not possible to identify individual participants. Thus, we do not present any information on age or sex after each quote to avoid revealing the perceptions of individual participants.

Recruitment

We recruited the study participants from faculty and students at PT colleges in Ahmednagar (408,000 inhabitants) and Aurangabad (1.6 million inhabitants) and from PTs in private practice in Mumbai (22 million inhabitants). The principals at the Padmashri Dr. Vithalrao Vikhe Patil College of Physiotherapy, Ahmednagar and the Mahatma Gandhi Mission’s Institute of Physiotherapy, Aurangabad, personally approached potential participants from their respective institutions using the above-described criteria for purposeful sampling. The private practitioners from Mumbai were purposefully selected from the network of one research team member (SK), who contacted them via social media.

We provided oral and written information to all participants about the aim of our study and their right to abstain from participating, to withdraw at any point in time without giving any reason, and that this would not negatively impact their professional lives. We obtained the written informed consent of each participant.

Data collection

We collected demographic and background data (sex, age, educational background, years of employment, current employment, area of specialization, experience of managing patients with knee/hip OA, own level of physical activity) for descriptive purposes using a structured questionnaire.

One of the researchers (CHO), who was not previously acquainted with any of the study participants, conducted semi-structured qualitative research interviews in English in February 2018. She performed face-to-face interviews in dedicated rooms at the respective institutions in Ahmednagar and Aurangabad, and in a conference room of a Mumbai hotel, with no additional persons present. Two research team members (CHO, ES) constructed a predetermined interview guide, which was reviewed by another two members (SK, KK). The final interview guide consisted of a few main areas aimed to explore the study participants’ approaches to hip/knee OA (). We asked open-ended questions with follow-up and probing questions in order to elaborate and get more details. The interviews lasted between 21 and 40 minutes and were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Table 2. Interview guide used for semi-structured interviews.

Data analysis

We analyzed the interview data with inductive qualitative content analysis (Elo et al., Citation2014; Lindgren, Lundman, and Graneheim, Citation2020) using the following steps: 1) familiarization with the data; 2) open coding and identification of meaning units; 3) creation of descriptive themes; 4) refining and labeling them; 5) creation of a theme of meaning; and 6) selecting quotes for illustration purposes (). To ensure trustworthiness more than one member of the research team took part in the analysis. Thus, ES performed the first five analytical steps. CAT then independently read and familiarized herself with six randomly selected interviews to validate the preliminary analysis performed by ES. Also, they both refined and relabeled the themes by discussing and comparing the emerging results and interpretations with the content of the original interviews until consensus was reached. CHO acted as a peer reviewer in the latter part of the analytical procedure and also assessed whether the findings reflected the content of the interviews. ES selected a large number of quotes, and CHO then reduced them to suitable numbers for the final manuscript.

Table 3. Description of the data analysis.

Findings

We identified OA as a degenerative and irreversible condition as the main overarching theme of meaning with the four descriptive themes: 1) Assessment; 2) Standardized treatment protocol; 3) Leadership; and 4) Patient compliance as PTs’ approaches to OA in Maharashtra, India (). The theme of meaning and the descriptive themes are described below and are illustrated by direct quotes from the interviews followed by identification numbers to illustrate the inclusion of quotes from multiple participants. In the quotes, (–) indicates that text of no importance has been deleted, (*) indicates parts of the quotes that are inaudible, and (…) indicates silence for an extended period.

Figure 1. Overarching theme of meaning and four descriptive themes derived from the analysis of 19 interviews.

Awareness of OA as a degenerative and irreversible condition

The PTs’ awareness seems to be based on their understanding of OA as a degenerative and irreversible condition with pain, physical impairment and joint destruction as key features. This awareness appears to manifest in their selection of assessment elements, application of a standardized treatment protocol, and strong leadership to create awareness in patients to improve their understanding of OA and their compliance with instructions to reduce their symptoms. PTs also regarded that local health camps and community support groups, in which knowledge and advice can be shared in the local language and encouragement given to seek health care at an early stage in order to reduce symptoms and physical impairments, is beneficial for individualizing awareness of OA. It was suggested that OA management would improve if medical doctors were more aware of PTs’ expertise in reducing the consequences of OA.

Assessment

The following elements based on the PTs’ awareness of OA appear to be helpful in guiding the design of the treatment protocol and communicating about the patients’ outcome expectations. Their focus seems to be merely on body functions and body structures, including biomechanics.

A detailed history with questions related to age, the onset of symptoms and work conditions is collected by the PT before starting the treatment, as is any information about history of surgery, previous trauma, overuse and other diseases or causative factors.

“Mostly their age, any previous history of trauma, and have they undergone any calcium or vitamin D test? Just to know their bone structure. What are the main activities they do, like, does it include more of sitting on the floor or excessive knee bending?” (#18)

X-rays were used to establish OA type (medial, lateral or fully tricompartmental) and to determine the Kellgren-Lawrence grade in order to classify OA severity.

“ – we look at the radiographs, we see how much damage there is in the joint.” (#17)

Pain history is taken along with information on the type, duration and intensity of pain, including aggravating and relieving factors, because pain appears to have a major impact on patients’ lives.

“The intensity of pain on a VAS scale. — And any aggravating factors, relieving factors, I would like to know. And irritability of the symptoms. — Type of pain, what is bothering him. — Nature of pain. So basically, for the pain history I would go into detail.” (#34)

Observation of any structural signs and symptoms such as tenderness, spasms, crepitations and locking are taken into account, together with any swelling, deformities and patellar position.

“By observation I can see if there is any deformity, or something is there or if there is any changes in the posture.” (#33)

Physical examination includes palpation, assessment of the range of motion, isometric muscle strength, joint instability and patellar mobility.

“After that [observation] I go for palpation and examination of a particular joint – then patellar position, patellar mobility, I check, and I just … basically look for the knee’s range of motion, along with isometrics to check the strength of the muscles of the knee —.” (#33)

“I’m a manual therapist, so I would like to check the accessory movements, the glides, — And then muscle strength is very important. I would like to check MMT, manual muscle strength, and grade the muscle power. — Any balance issue the patient has. — Yeah, basically range of motion and MMT would be the main focus.” (#34)

Activity limitations, not least in typical Indian activities such as crossed leg sitting and squatting, are orally reported by the patients or by using structured activity measures as part of the basis for treatment design. The patients may also sometimes be asked about their level of physical activity.

“Then we also need to ask him, ki [OK], how much walking, or what type of activity he is doing, whether he’s sedentary or what’s the level of activity he’s doing.” (#28)

“And sometimes we ask for scales or for functional activity scales.” (#33)

Standardized treatment protocol

The PTs appear to plan the treatment protocol for each patient based on their professional awareness of the condition and on their clinical assessment. The radiological grade of OA seems to be particularly important for this. Passive treatment appears to be initially prioritized before moving on to counseling and active treatment.

“So, first we reduce the pain by giving some electrotherapeutic modalities. And if the patient is having, then we can start with some of the manual techniques. But if the patient is having pain, like, uh, the patient can do such activities that are not bothersome, but yeah, in certain activities it is limited, we go more for the muscle training.” (#27)

Because patients often expect immediate pain relief, pain management appears to be a first-line treatment that includes electrotherapeutic modalities such as TENS, interferential current, ice/hot packs, ultrasound, short-wave, and laser therapy.

“Uh, ultrasound … ultrasound on pulse mode, and pulse mode for phonophoresis for *, it works good. — I feel — Interferential therapy also works well.” (#28)

Manual techniques such as mobilization, gliding and traction seem to be used on virtually every patient to relieve pain and increase their range of motion. To increase flexibility, the PT mainly seems to perform passive techniques.

“— in arthritis patients, joints are stiff very early. So, we can’t do the exercise directly on stiff joints. First, we have to mobilize it. Improve the mobility of the joint. Then you can proceed with our exercises.” (#19)

Active stretching exercises or body-mind exercises (i.e. tai-chi) also appear to be endorsed. Simple isometric exercises to strengthen weak muscles, mainly the quadriceps, are complementary pain management and seem to be prescribed to almost every patient. Balance exercises to improve proprioception are also used, as well as aerobic exercises, but do not seem to be regular components of the standardized treatment protocol.

“We can, uh, treat the patient with the — exercises like strengthening protocols are given, flexibility exercise —, resistance training exercises are given. Aerobic exercises are given today. In, um, mostly the aerobic exercises are given, uh, to peoples, like, uh, walking, jogging, uh, like more, more major muscles, uh, are activated. — in that way, if there is an active lifestyle, a person has less chances to develop osteoarthritis.” (#22)

Educating patients on aspects of their condition appears to be a self-evident part of the PTs’ OA management. It includes joint protection techniques and ergonomics and seems to be tailored to the patient’s individual needs rather than a standardized form of treatment.

“So, I, uh, first I will educate them regarding the disease, or the problem, then I will tell them the importance of the physiotherapy, — why exercise is needed, and this is a lifelong process.” (#33)

“— many patients come over here with farming occupations or laboring activity. So, uh, we have to give them advice because they have to squat down, and even at home, they tend to sit crossed leg. Indian toilets are there.” (#25)

Assistive devices such as braces, walkers or insoles are prescribed to reduce pain and activity limitation. Taping and splints are used to support joints.

“Like a knee brace, but, uh, it is not exactly a brace to redu … to provide a stability or something, but just to provide, uh, proprioception to the person. Sensory feedback.” (#23)

A physically active lifestyle is recommended to increase physical capacity and reduce weight. However, the formal use of behavior change techniques to promote physical activity does not seem to be part of the structured treatment protocol.

“Because of overweight, the patient may cause … may be having the osteoarthritis at an early age. — some strategies to reduce that pain. — Unloading exercises for reducing weight. — cross-trainer, — maybe cycling, —. Something like jogging and all the jumping exercises, that may not be possible for those patients.” (#23)

Leadership

The PTs seem to consider themselves entitled to play a leadership role due to their awareness of OA. They appear to have a strong sense of responsibility for assessing a patient’s condition, treating their disabilities with a standardized recipe-like protocol, and teaching them about OA.

“Our responsibility is to treat the patient, uh, in the minimal number of days so that the patient can get their knee recovered as soon as possible and return to their activities.” (#27)

Individual scientific papers seem to be trusted as scientific evidence, while international guidelines for the management of OA do not appear to be recognized or implemented.

“— I just read the abstract of that article therein they said that dry needling helps in improving your joints, uh, like, maintaining the joint space — So, I want to learn it. — dry needling will create wonders.” (#25)

Despite listening to their patients, the PTs seem to consider themselves responsible for ultimately deciding on whether to use the treatment protocol and that the patients must respect this. The knowledge transfer appears unidirectional and does not include much dialogue or behavior modification techniques. Instructing patients on how to avoid the negative consequences of OA is regarded as conferring optimal treatment cooperation, although creating awareness and compliance appears to be challenging particularly among patients with poor education and difficult living conditions. The communication styles appear to stipulate the rules and regulations as well as fear induction, but also listening and showing interest in order to create mutual understanding. Diagrams and information sheets related to the treatment protocol are provided to enhance compliance. Some mistrust seems to manifest in verbal checkups when controlling whether the patients were complying with the treatment regimens.

“I need to make them understand the importance of exercises, and tell them, “If you do not do these exercises, you will end up here.” So basically, the fear factor is important, you need to really scare the patient — That’s my experience. In India, — because of the understanding level, and they are quite lazy.” (#34)

“So, we need to find out, or understand what exactly, why exactly the patient is saying yes or no to something. And then if we can help them to improve their lifestyle. — It becomes much easier for therapists to work — and then for patients also to accept and follow that. — if we understand the way they are doing things and change a little, it becomes easier for both of us.” (#37)

Patient compliance

The PTs suggest that patients become aware of OA by listening and learning from them, following their advice, and cooperating in the treatment, for example, performing exercises or using prescribed pain management. They also seem to think that patients expect to get better often with immediate effect or relief, but that they are not always very positive about the treatment; particularly active treatment such as exercise. Thus, problems regarding recurrent episodes of deteriorating symptoms may occur due to a poor level of compliance. If the patients are not satisfied with the treatment result, such as less pain, they will not show up for follow-ups or further treatment at the clinic.

“— the patients need immediate effect, or immediate relief, even if we have told them about the condition, it is a degenerative process —. The patient won’t understand.” (#23)

Some patients perform exercises regularly, but far from all of them. The patients who are hesitant about exercising, who only exercise for a couple of days, or who only ask for passive treatment may not recover satisfactorily.

“Some patients do it [exercise] religiously — but not all of them. — especially if a patient is not educated, it becomes really difficult. So, we may have — less than fifty per cent compliance in home exercise programs. But sometimes they don’t … they don’t do those exercises.” (#35)

“And patients who actually do the exercises, they recover. — But, again, as I said, supervised exercise works. Unsupervised, — I don’t think they really do it at home.” (#34)

Nevertheless, responsibility is considered to lie with the patient. Supervised exercise in a clinical setting may be a better option than home-based exercise that may be inconvenient and result in poor compliance. Furthermore, unsupervised exercise is considered difficult due to common hesitation on the part of patients to exercise at home on their own. Sometimes, local healthcare workers could supervise exercising to ensure that patients perform them properly and safely. It is regarded as the patients’ duty to comply with treatment so as not to waste the treatment they received at the clinic.

“— if I am able to give my 70 per cent, then the patient can give his 30 per cent. — My treatment should not go vai— in vain. It should not go wasted. — When we both are working together, nicely, only then can we expect the results. So, it’s obviously … both-sided.” (#28)

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to explore approaches to evidence-based management of OA among Indian PTs. The present findings indicate that their clinical practice is based on a general perception of OA as being a degenerative and irreversible condition, resulting in the frequent use of assessments, treatments, leadership styles and strategies for patient compliance that are not endorsed, or are even advised against in international CPGs. Other steps and measures recommended in CPGs do not seem to have been implemented (Kolasinski et al., Citation2020).

Barriers to the implementing OA CPGs in Western countries have previously been identified at different levels (i.e. in community and healthcare systems, among healthcare providers, and at the client level) (Ferreira de Meneses, Rannou, and Hunter, Citation2016; MacKay, Hawker, and Jaglal, Citation2018). Our findings from an Indian context are very similar to previous findings, but barriers that are specific to an Indian context were also identified in our study.

In India barriers at the client level include patients’ preferences that are important in PTs’ clinical decision-making because most people do not have health insurance and pay for physical therapy out of their own pockets. This is reflected in our findings in the perceptions of patients’ demands for immediate pain relief and the PTs’ frequent use of modalities and passive manual techniques. Furthermore, the approaches of Indian patients to OA (Swärdh et al., Citation2021) may cause them to delay seeking physical therapy, which prevents the early and active management of OA. Thus, the prevention of OA-related joint changes and disability may often be too late and leave PTs with a perception of OA as an irreversible condition and of CPGs as not applying to their practice.

Barriers at Indian healthcare provider and system levels are reflected in our findings of PTs’ desire to receive more recognition of their knowledge and skills from medical doctors. This is similar to previous findings on a perceived lack of respect for Indian PTs (Grafton and Gordon, Citation2019). Moreover, the mainly biomedical perspective reflected in our findings by the PTs’ choice of assessments and treatments, may indicate their lack of autonomy in the hierarchical Indian healthcare system, with PTs working under the guidance and proposals from medical doctors’ prescriptions (Grafton and Gordon, Citation2019).

Community-level barriers to the dissemination and implementation of CPGs in India might be partially addressed as suggested by our participants by local health camps and community support groups. Moreover, even though the Indian system of higher education is well developed, MPT degrees in India are clinical and may not result in the same development of reflective critical evaluation and research skills when compared to scientific MPT degrees in many Western countries (Grafton and Gordon, Citation2019). This may explain our findings of the neglect of CPGs and the reliance on individual studies on specific assessment or management techniques. Furthermore, the lack of certification boards on a national and state levels in India represents another barrier to the implementation of evidence-based practice among Indian PTs (Khatri and Khan, Citation2017).

It was surprising to find that neither CPGs nor any of the OA management strategies with robust scientific evidence were mentioned during any of our interviews. For example, it would have been reasonable to expect that our participants would be familiar with new insights into the role of sensitization and centralization as causes of OA pain and that a biopsychosocial model of pain management should have been brought up (Neogi, Citation2013). On the contrary, detailed interest in the physical aspects of pain and the frequent use of passive pain treatment formed their approaches, may not help patients but actually risk harming them by inducing more pain, learned helplessness, and fear-avoidance behaviors (Linton, Flink, and Vlaeyen, Citation2018). Similarly, physical activity which not only reduces the risk of comorbidity and premature death (Ekelund et al., Citation2019) but is also a powerful tool for pain reduction (Geenen et al., Citation2018) was perceived by our participants to be merely a strategy for weight reduction or for increasing aerobic capacity, per se. Yet another surprising finding concerns our participants’ frequent use of static quadriceps exercises and the failure to provide dynamic neuromuscular training, which has proven superior to education only as well as to conventional quadriceps training, and to be equally effective as analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs for reducing symptoms and disability in patients with OA (Holsgaard-Larsen et al., Citation2017; Rashid et al., Citation2019; Villadsen et al., Citation2014). Moreover, our participants seemed unaware of evidence-based approaches to guidance in behavior change to improve adherence (Demmelmaier, Åsenlöf, and Opava, Citation2013). Rather the PTs expected compliant behavior after merely instructing their patients about what they need to know and do.

One strength of our study was the recruitment of participants from different demographic and professional backgrounds, which resulted in a broad variety of perceptions supported by illustrative quotes, indicating that our data were rich (Kvale, Citation2009; Malterud, Citation2001). Trustworthiness was strengthened through the involvement of researchers experienced in qualitative methods and OA in the data analysis and peer review of the findings by a senior researcher. Since qualitative research methodology is currently not used much in Indian PT research, no experienced interviewer with the appropriate language and cultural skills was available for the data collection and analysis. Therefore, the interviews were performed by a Swedish PT in English, which was not the native language of either the interviewer or the participants. Although the interviewer had experience with Indian PT practice and education and used follow-up and probing questions to facilitate information, it cannot be ruled out that language and cultural barriers may have hampered data collection and analysis. Taking this into account, focus group interviews, with greater opportunities for common reasoning among our participants, may have facilitated more information than individual interviews. The interview guide was developed in collaboration between the Indian and two Swedish research team members. The former member agreed that Indian PTs’ approaches were familiar to him, as described in our findings, and he was also involved in their interpretation. Generalization of findings is not the aim of qualitative research. However, we believe that our findings can be recognized in similar settings to ours and can be useful to people interested in OA approaches among Indian PTs, as well as to PTs in similar contexts in non-Western countries.

The present findings increase the understanding of the context-specific reasons for the poor implementation of OA CPGs in India and probably in other non-Western countries. They suggest that a number of structural barriers need to be addressed. Thus, awareness campaigns about the effectiveness of OA management according to CPGs, and the important role that PTs play, could be informed by the present findings and tailored to the public and to policymakers, medical doctors and other health professionals in non-Western countries. Moreover, our findings can be used to understand the educational needs of PT students and practicing PTs for evidence-based practice in these countries (Khatri and Khan, Citation2017).

Future studies should address the challenges of disseminating and implementing CPGs for OA among PTs and people with OA in India and other non-Western countries. More original research from these countries is also required, for example, comparing the outcomes of the current management approach to OA versus management according to CPG.

Conclusion

The present findings can inform the design of awareness campaigns for different Indian stakeholders about the benefits of evidence-based OA management and increase the understanding of the needs for education about OA CPGs among PT students and practicing PTs in non-Western contexts. From an international perspective, it is important to recognize that CPGs are mainly based on studies carried out in Western countries and that there are context-specific barriers to implementation in other parts of the world that have large populations.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the principals at the Padmashri Dr. Vithalrao Vikhe Patil College of Physiotherapy, Ahmednagar, and at the Mahatma Gandhi Mission’s Institute of Physiotherapy, Aurangabad, for their cooperation in participant recruitment and to all participating PTs for giving their time and generously sharing their approaches to OA.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, Christy W, Cooke TD, Greenwald R, Hochberg M, et al. 1986 Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis and Rheumatism 29: 1039–1049.

- Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Kraus VB, Lohmander LS, Abbott JH, Bhandari M, et al. 2019 OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, Hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society 2711: 1578–1589. 10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011

- Barton CJ, Ezzat AM, Bell EC, Rathleff MS, Kemp JL, Crossley KM 2021 Knowledge, confidence and learning needs of physiotherapists treating persistent knee pain in Australia and Canada: A mixed-methods study Physiotherapy Theory And Practice. 1-13. Online ahead of print 10.1080/09593985.2021.

- Battista S, Salvioli S, Millotti S, Testa M, Dell’Isola A 2021 Italian physiotherapists’ knowledge of and adherence to osteoarthritis clinical practice guidelines: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 221: 380.10.1186/s12891-021-04250-4

- Chandra D 2017 Osteoarthritis. India: National Health Portal. Accessed 30-11-2021. https://www.nhp.gov.in/disease/musculo-skeletal-bone-joints-/osteoarthritis.

- Demmelmaier I, Åsenlöf P, Opava C 2013 Supporting stepwise change: Improving health behaviors in rheumatoid arthritis with the example of physical activity. International Journal of Clinical Rheumtology 81: 89–94.10.2217/ijr.12.75

- Egerton T, Nelligan RK, Setchell J, Atkins L, Bennell KL 2018 General practitioners’ views on managing knee osteoarthritis: A thematic analysis of factors influencing clinical practice guideline implementation in primary care. BMC Rheumatology 21: 30.10.1186/s41927-018-0037-4

- Ekelund U, Tarp J, Steene-Johannessen J, Hansen BH, Jefferis B, Fagerland MW, Whincup P, Diaz KM, Hooker SP Chernofsky A et al 2019 Dose-response associations between accelerometry measured physical activity and sedentary time and all cause mortality: Systematic review and harmonised meta-analysis. British Medical Journal 366: 14570.

- Elo S, Kääriäinen M, Kanste O, Pölkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngäs H 2014 Qualitative content analysis. SAGE Open 2014: 1–10.

- Ferreira de Meneses S, Rannou F, Hunter DJ 2016 Osteoarthritis guidelines: Barriers to implementation and solutions. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 593: 170–173.10.1016/j.rehab.2016.01.007

- Geenen R, Overman CL, Christensen R, Åsenlöf P, Capela S, Huisinga KL, Husebø ME, Köke AJ, Paskins Z, Pitsillidou IA, et al. 2018 EULAR recommendations for the health professional’s approach to pain management in inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 776: 797–807. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212662

- Grafton K, Gordon F 2019 A grounded theory study of the narrative behind Indian physio-therapists global migration. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 342: 657–671.10.1002/hpm.2725

- Holsgaard-Larsen A, Clausen B, Søndergaard J, Christensen R, Andriacchi TP, Roos EM 2017 The effect of instruction in analgesic use compared with neuromuscular exercise on knee-joint load in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A randomized, single-blind, controlled trial. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage / OARS, Osteoarthritis Research Society 254: 470–480.10.1016/j.joca.2016.10.022

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE 2005 Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research 159: 1277–1288.10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hunter DJ, Bierma-Zeinstra S 2019 Osteoarthritis. Lancet 39310182: 1745–1759.10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30417-9

- Khatri SM, Khan N 2017 A review of physiotherapy profession in India with SWOT analysis. Pravara Medical Review 9: 19–25.

- Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, Oatis C, Guyatt G, Block J, Callahan L, Copenhaver C, Dodge C, Felson D, et al. 2020 2019 American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, Hip, and knee. Arthritis and Rheumatology 722: 220–233. 10.1002/art.41142

- Kvale S 2009 InterViews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. 2nd Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Lindgren BM, Lundman B, Graneheim UH 2020 Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies 108:103632. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632

- Linton SJ, Flink FIK, Vlaeyen JWS 2018 Understanding the etiology of chronic pain from a psychological perspective. Physical Therapy 985: 315–324.10.1093/ptj/pzy027

- Luhar S, Timæus IM, Jones R, Cunningham S, Patel SA, Kinra S, Clarke L, Houben R, Joe W 2020 Fore-casting the prevalence of overweight and obesity in India to 2040. PLoS One 152: e0229438.10.1371/journal.pone.0229438

- MacKay C, Hawker GA, Jaglal SB 2018 Qualitative study exploring the factors influencing physical therapy management of early knee osteoarthritis in Canada. BMJ Open 811: e023457.10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023457

- Malterud K 2001 Qualitative research: Standards, challenges, and guidelines. Lancet 3589280: 483–488.10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05627-6

- Murphy LB, Cisternas MG, Pasta D, Helmick C, Yelin E 2018 Medical expenditures and earnings losses among US adults with arthritis in 2013. Arthritis Care and Research 70 6: 869–876.10.1002/acr.23425

- Neogi T 2013 The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 219: 1145–1153.10.1016/j.joca.2013.03.018

- Rashid SA, Moiz JA, Sharma S, Raza S, Rashid SM, Hussain ME 2019 Comparisons of neuromuscular training versus quadriceps training on gait and WOMAC index in patients with knee osteoarthritis and varus malalignment. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine 181: 1–8.10.1016/j.jcm.2018.07.003

- Runciman WB, Hunt TD, Hannaford NA, Hibbert PD, Westbrook JI, Coiera E, Day RO, Hindmarsh DM, McGlynn EA, Braithwaite J 2012 CareTrack: Assessing the appropriateness of health care delivery in Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 1972: 100–105.10.5694/mja12.10510

- Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Smith E, Hill C, Bettampadi D, Mansournia MA, Hoy D, Ashrafi-Asgarabad A, Sepidarkish M, Almasi-Hashiani A, et al. 2020 Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990-2017: A systematic analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 796: 819–828. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-216515

- Swärdh E, Jethliya G, Khatri S, Kindblom K, Opava CH 2021 Approaches to osteoarthritis - A qualitative study among patients in a rural setting in central western India. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 10.1080/09593985.2021.1872126 Online ahead of print 1–10.

- Tang CY, Pile R, Croft A, Watson NJ 2020 Exploring physical therapist adherence to clinical guidelines when treating patients with knee osteoarthritis in Australia: A mixed methods study. Physical Therapy 100 7: 1084–1093.10.1093/ptj/pzaa049

- Teo PL, Bennell KL, Lawford BJ, Egerton T, Dziedzic KS, Hinman RS 2020 Physiotherapists may improve management of knee osteoarthritis through greater psychosocial focus, being proactive with advice, and offering longer-term reviews: A qualitative study. Journal of Physiotherapy 664: 256–265.10.1016/j.jphys.2020.09.005

- Villadsen A, Overgaard S, Holsgaard-Larsen A, Christensen R, Roos EM 2014 Immediate efficacy of neuromuscular exercise in patients with severe osteoarthritis of the Hip or knee: A secondary analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rheumatology 417: 1385–1894.10.3899/jrheum.130642

- Walker A, Boaz A, Hurley MV 2020 The role of leadership in implementing and sustaining an evidence-based intervention for osteoarthritis (ESCAPE-pain) in NHS physiotherapy services: A qualitative case study. Disability and Rehabilitation 448: 1313–1320.10.1080/09638288.2020.1803997

- Wei Y, Wang Z, Wang H, Li Y, Jiang Z, Rizzo A 2019 Predicting population age structures of China, India, and Vietnam by 2030 based on compositional data. PLoS One 44: e0212772.10.1371/journal.pone.0212772

- Zadro J, O’Keeffe M, Maher C 2019 Do physical therapists follow evidence-based guidelines when managing musculoskeletal conditions? Systematic review. BMJ Open 910: e032329.10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032329

- Zhang W, Doherty M, Peat G, Bierma-Zeinstra MA, Arden NK, Bresnihan B, Herrero-Beaumont G, Kirschner S, Leeb B, Lohmander LS, et al 2010 EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 69: 483–489.