ABSTRACT

Introduction

Active patient participation is an important factor in optimizing post-stroke recovery, yet it is often low, regardless of stroke severity. The reasons behind this trend are unclear.

Purpose

To explore how people who have suffered a stroke, perceive the transition from independence to dependence and whether their role in post-stroke rehabilitation influences active participation.

Methods

In-depth interviews with 17 people who have had a stroke. Data were analyzed using systematic text condensation informed by the concept of autonomy from enactive theory.

Results

Two categories emerged. The first captures how the stroke and the resultant hospital admission produces a shift from being an autonomous subject to “an object on an assembly line.” Protocol-based investigations, inactivity, and a lack of patient involvement predominantly determine the hospital context. The second category illuminates how people who have survived a stroke passively adapt to the hospital system, a behavior that stands in contrast to the participatory enablement facilitated by community. Patients feel more prepared for the transition home after in-patient rehabilitation rather than following direct discharge from hospital.

Conclusion

Bodily changes, the traditional patient role, and the hospital context collectively exacerbate a reduction of individual autonomy. Thus, an interactive partnership between people who survived a stroke and multidisciplinary professionals may strengthen autonomy and promote participation after a stroke.

Introduction

Acute stroke care has improved considerably over the past several decades, as practices and systems for rapid and efficient assessment, diagnosis, and treatment have been refined (Phipps and Cronin, Citation2020). For reducing mortality rates and loss of function, the practice of treating patients in a dedicated stroke unit has been the single most important factor (Langhorne and Ramachandra, Citation2020) but this development has also been driven by the more expeditious recognition of stroke symptoms along with the combination of acute medical treatment and early multidisciplinary rehabilitation including physiotherapy (Bernhardt, Godecke, Johnson, and Langhorne, Citation2017; Langhorne and Ramachandra, Citation2020). After a stroke, active patient participation involving engagement in meaningful activities is essential for bolstering the neuroplastic basis for functional recovery (Brodal, Citation2010). Indeed, since neuroplasticity is most prominent in the initial phase after a neural lesion (Bernhardt, Godecke, Johnson, and Langhorne, Citation2017) patient participation is especially exigent in the stroke unit and the subacute rehabilitation facility if patients are to recover the abilities used for daily living.

Yet, despite the manifest importance of patient participation, current practices can often hinder or even discourage it during both acute admission and subsequent rehabilitation; patients remain inactive (Field et al., Citation2013) and systemically excluded from decision-making (Légaré et al., Citation2018). While research has demonstrated that patient participation can optimize recovery (Elloker and Rhoda, Citation2018; Ezekiel et al., Citation2019; Jones et al., Citation2021; Paolucci et al., Citation2012), in reality patient participation in social, leisure, or professional activities after a stroke are consistently reported to be low irrespective of initial stroke severity, level of disability, or geographical location (Eriksson, Baum, Wolf, and Connor, Citation2013; Foley, Nicholas, Baum, and Connor, Citation2019; Paolucci et al., Citation2012). Foley, Nicholas, Baum, and Connor (Citation2019) suggested that factors other than the presence of impairments are crucial to consider when investigating active participation after a stroke. There is a need for more in-depth contextualization and exploration of the reasons behind restricted participation and how this proclivity develops from the acute incident and across the rehabilitation journey. After all, the experience and consequences of a stroke are not determined exclusively by the body, but rather are shaped by the whole set of institutions, practices, and networks through which the individual passes often over the course of months or years.

Participation is a complex and subjective term, one difficult to delimit and measure and yet nonetheless important to investigate and facilitate (Eriksson, Baum, Wolf, and Connor, Citation2013; Ezekiel et al., Citation2019). Definitions of participation in previous reports span taking part in therapy, training, and activities (Paolucci et al., Citation2012), contributing to decision-making (Légaré et al., Citation2018), and involvement in a life situation (World Health Organization, Citation2013). For the purpose of this paper we apply Mallinson and Hammel’s (Citation2010) perspective that “participation necessarily occurs at the intersection of what a person can do, has the affordances to do, and is not prevented from doing by the world in which he or she lives and seeks to participate.” This conceptualization of participation encompasses both social and everyday activity participation, a scope that would include the rehabilitation process immediately following a stroke.

Autonomy, a requisite of participation, is reportedly reduced over the long term among people who survived a stroke (Palstam, Sjödin, and Sunnerhagen, Citation2019). Moreover, active interaction, engagement, and a sense of belonging promote participation (Foley, Nicholas, Baum, and Connor, Citation2019) yet it is not clear what restricts these after a stroke. In a review of qualitative studies on post-stroke physical rehabilitation Luker et al. (Citation2015) called for a deeper consideration of how we engage with people who have survived a stroke, and of how the physical and regulatory environments of hospitals influence recovery more broadly. Only by understanding how patient participation is facilitated and constrained by the regulatory environment of hospitals can we properly support the recovery of those who have had a stroke both during admission and after discharge.

To understand the complexity of post-stroke patient participation, it is instructive to explore how persons who survived a stroke have experienced the stroke and their journey toward recovery. To aid in the interpretation of such first-person experiences we turn to enactive theory, as it can illuminate previously under-investigated aspects of patient participation following a stroke. Within this framework, autonomy captures how individuals generate and maintain their identity in interaction with their various (physical and social) environments (Thompson, Citation2007). What is interesting about this approach is that just like individuals are autonomous, the social interaction processes that emerge between them can also take on a certain autonomy (De Jaegher and Di Paolo, Citation2007). Social interactions can develop a temporary ‘life of their own,’ as they can coordinate the behaviors of their participants. In addition to this “local” autonomy of interactive processes, practices around behaviors are often also highly conventionalized and rooted in strong social norms (De Jaegher, Peräkylä, and Stevanovic, Citation2016). Institutional settings like hospitals may involve or even demand specific pre-coordinated applications of these rules such as with staff-patient relations. Tensions then arise between the self-organization of the patient as an autonomous living being and the interactional coordination which is partly determined by social norms. The concepts of self-organization and the role of social norms may reveal heretofore unrecognized dimensions of patient participation, which could improve the follow-up practices for people who have had a stroke. The purpose of the present study is to explore how people who have survived a stroke perceive the transition from being an independent individual to a dependent one, their role in post-stroke rehabilitation, and the subsequent influence of these self-perceptions on participation in their life and in society. In exploring these experiences, we addressed the following research question: What are the basic environmental and personal factors that influence patient participation during the acute and subacute phases after a stroke?

Methods

Design

Based on the research question, qualitative interviews within a phenomenological hermeneutic methodological framework was chosen, as it allows knowledge to be derived from lived experiences (Cresswell and Poth, Citation2018; Malterud, Citation2015).

Theoretical framework

In the analysis of data, enactive theory was chosen as the framework for interpretation. Enactive theory has previously been utilized quite successfully within the fields of neurorehabilitation and physiotherapy (Hay, Connelly, and Kinsella, Citation2016; Lahelle, Øberg, and Normann, Citation2020; Martinez-Pernia, Citation2020; Normann, Citation2020). It is rooted in phenomenology and embodied cognition and it has strong links to dynamic systems theory (Varela, Thompson, and Rosch, Citation2016). Five closely related concepts constitute the enactive approach: 1) autonomy; 2) sense-making; 3) emergence; 4) experience; and 5) embodiment. Most relevant for this study is the term autonomy which is defined as “a system composed of several processes that actively generate and sustain an identity under precarious conditions” (De Jaegher and Di Paolo, Citation2007). In this context, the term precarious points to the fact that isolated components would diminish or extinguish in absence of the organization of the system as a network of processes. Autonomy thus refers to the ability of an organism (i.e. a living cell or a human being) to behave as a coherent, self-determining, and self-sustaining unit as opposed to a machine that is controlled from the outside (Di Paolo, Rohde, and De Jaegher, Citation2010). As cognitive systems, we are also autonomous in an interactive sense vis-à-vis our engagement with our environment. We actively participate in the generation of meaning through our bodies and actions; we “enact a world.” This creation and appreciation of meaning is called sense-making (Di Paolo, Rohde, and De Jaegher, Citation2010). The concept of emergence describes how a new property or process emerges out of the interaction of different existing processes or events. Experience is intertwined with being alive and immersed in a world of significance, and it is viewed as a skillful aspect of embodied activity. Within the enactive framework, cognition equals embodied action; the individual is understood as an experiencing and expressing body (i.e. an embodied self) in relation with others through the sensorimotor processes of social interaction, where social understanding and sense-making are interactional and inter-corporal processes (Fuchs and De Jaegher, Citation2009; Varela, Thompson, and Rosch, Citation2016).

Context of the study

This study was nested within a randomized controlled trial (RCT) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04069767) comparing a new physiotherapy intervention I-CoreDISTFootnote1 to usual care (). Informants were recruited from those already included in the RCT. The study was conducted from December 2019 to December 2020 and encompassed two stroke units, their collaborating rehabilitation units, and neighboring municipalities in two regions of Norway. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in .

Table 1. I-Core DIST intervention and standard care.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the RCT.

Following admission to a stroke unit in Norway patients are usually discharged to an in-patient rehabilitation unit, to their home, or to residential care depending on their level of independence. About 45% of patients are discharged home after a stroke, the majority without help (Norwegian Stroke Registry, 2019). All participants in the RCT, regardless of group allocation, received physiotherapy; this was either on a daily basis at an in-patient rehabilitation unit or three times per week at the participant’s home or an outpatient clinic. In most cases this represents a more intensive physiotherapy follow-up course than usually offered, and in this respect, we have created a somewhat artificial pathway for the purpose of the RCT.

Participants and sample

Following approval from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in Norway (REK North: 2017/1961), recruitment for the RCT was conducted at the two stroke units by designated physiotherapists. Informed, written consent was obtained for all participants. To ensure a rich material and to strengthen the credibility of the study, informants were purposively sampled for interview (Cresswell and Poth, Citation2018). Seventeen participants (ID1–ID17) were strategically selected from both study arms and from different geographical locations. To further ensure the diversity of the sample these informants also vary in gender, age, stroke location, and level of disability. The characteristics of the informants are shown in . We initially aimed to interview the informants 6–12 weeks after inclusion, but due to challenges with RCT recruitment mainly due to lockdown and subsequent restrictions related to the Covid-19 pandemic, informants for the interview study were sampled from the initial 40 RCT participants rather than from the full sample which was expected to be 80. This resulted in some being interviewed up to 38 weeks after inclusion.

Table 3. Overview of informants.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted and recorded by MS between December 2019 and December 2020. They lasted between 20 and 91 minutes, constituting a total interview time of 774 minutes and an average interview-time of 45.5 minutes. The first six interviews were held face-to-face in a location of the informant’s choosing. The remaining interviews were, due to Covid-19 restrictions, performed over the phone, using a loudspeaker and a separate digital recorder. A theme-based interview guide with open-ended questions addressed the informants’ experiences and initiated their reflections on: 1) the acute situation; 2) the participation in daily tasks and activities in hospital; 3) the transfer from hospital to home or to rehabilitation unit; 4) the daily activities at home; and 5) the in-patient or out-patient rehabilitation (). Communicative validation and credibility was ensured during interviews by asking follow-up questions, by rephrasing, and by requesting details of positive and negative experiences (Brinkmann and Kvale, Citation2015). A debrief was conducted and revealed no negative experiences from participating in the interviews.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim by MS and a secretary otherwise unconnected to the project. Data were coded using NVivo software, v12.6.0 (QSR International, 2019) and analyzed thematically through systematic text condensation (STC), a pragmatic procedure based in phenomenology that allows researchers to search for the essence of a phenomenon (Malterud, Citation2012). When the analysis of data stopped revealing new themes, we considered saturation to be obtained and consequently concluded that the data gathered possessed adequate information power according to recommendations for qualitative research (Malterud, Siersma, and Guassora, Citation2016). The analysis followed four steps: 1) Overall impression – Each interview was read as a whole by MS and BN who independently suggested preliminary themes. Subsequently, workshops by MS, BN, and ECA who had read most of the interviews, were conducted and agreement was established; 2) Decontextualization – MS identified meaning units, text fragments containing information about the research question in the transcribed material (Malterud and Malterud, Citation2012). Based on content, these were sorted into code groups. In this process we continuously moved between the meaning units and the research question to ensure that the code groups reflected the main themes in the material relevant to the research question; 3) Condensation – MS sorted the meaning units of each code group into subgroups and reduced the contents of each subgroup into a condensate written in first person and illustrated with a quote. Interpretations of condensates were discussed by MS, BN, ECA and HDJ; and 4) Synthesizing – Condensates were recontextualized as an analytical text in the third person, reviewed against the full transcript, and validated to ensure that the syntheses of the data reflected the original context. A category name replaced the previous code group name.

The final text was reviewed, and interpretations were informed by the existing literature, the theoretical framework, and the authors’ varied professional experiences. An example of the analysis process is shown in . Two main categories were generated through the analysis.

Table 4. Examples of the analysis process.

Research team and reflexivity

Reflexivity was maintained throughout preparation, analysis, and writing by regularly discussing and challenging our established assumptions. In aiming for transparency we have adhered to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) (O’Brien et al., Citation2014). The research team encompasses several areas of competency. BN, ECA, and MS are experienced in neurological physiotherapy, KBA is a medical doctor specializing in neurology, and HDJ is a philosopher and an expert in enactive theory. Knowledge about the patient group from clinical practice in physiotherapy (BN, ECA, MS) and medicine (KBA) provided the research team with positioned insight (Paulgaard, Citation1997) and warranted awareness of our preconceptions. This insight guided MS, BN, ECA, and KBA with creating the interview guide - a process in which a user representative who is part of the project group participated to ensure the inclusion of themes important to stroke survivors. The interview guide was assessed and adjusted after the first two interviews (). These interviews were evaluated in depth by BN to enhance the competency of MS as an interviewer with a developmental emphasis on asking open-ended questions and adequate follow-up questions. None of the members of the research team were personally or professionally acquainted with any of the informants.

Results

The 17 informants were between 39 and 82 years of age and had National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)Footnote2 scores between 0–14 when admitted to hospital. 10 were allocated to the usual care group and 7 to the intervention group in the RCT (). The findings are organized in the two categories below, each presented as analytical text condensates supplemented with citations.

From an autonomous person to an assembly line object

The informants described the onset experience as an abrupt awareness of bodily change, one that manifested as a sudden inability to perform actions they normally took for granted, such as standing, driving, or other daily activities. As one informant put it:

What I noticed was that I could not speak, that I struggled to get the words out and say what I wanted. I was frustrated, because I couldn’t speak and I could not move like I wanted to. (ID 12)

Although the sudden loss of function was dramatic, most did not deem their situation an emergency, with the exception of three informants who fell and/or lost consciousness. Nine informants detailed changes that they did not associate with a stroke, despite some experiencing common symptoms, such as numbness or weakness in an extremity.

I actually don’t know. It was a very strange sensation […]. It was like, I just became a bit conscious of it. Almost like an inner voice saying there is something here. […] I wasn’t scared. I think now that I should have been, but it was so undramatic. So, I didn’t call the emergency number until later that evening. (ID 14)

Most felt a need to consult family or friends prior to contacting medical services. Two informants contacted emergency services themselves.

When admitted to hospital, informants figured themselves as passive receivers of treatment and care, subordinating their own actions to those of others in their descriptions. They trusted medical staff to provide updates on their condition and to make decisions on their behalf. In their stories, informants often described the days as long and boring, during which they simply remained in bed awaiting what they were doing next.

Well, I was lying there and it was: I was to have an x-ray, I was to have an MRI, and I was going for a CT-scan. So, I lay there waiting, the days went by waiting for those things. (ID 6)

However, the close monitoring provided a sense of security and care. None reported any activities apart from investigations, assessments, monitoring, or meals in the stroke unit. One felt no commitment from the hospital in terms of facilitating activity and another said he would have had the capacity for more activity than what was offered. Only two informants reported that they needed the rest, as they felt ill or exhausted. Most informants described being able to get help when needed, but some opted to struggle on their own with personal care as independence was of particular importance to maintaining dignity. Most found the staff helpful and supportive, but one sensed that his reduced function was a burden.

The staff found it a bit stressful. When getting help on the ward, there was a lot of irritation, that I shouldn’t spill water when I tried to wash and things like that. They thought I was clumsy. I mean, I needed help with lots of things, I spilled water on the floor. They were nice, but they got impatient. (ID 7)

With regards to early rehabilitation in the hospital stroke unit, five informants said that they did not see any therapists during their stay, while ten saw a physiotherapist or a speech therapist. These encounters were frequently described as assessments rather than therapy.

The informants described a transition from being active agents and decision-makers in their own lives to passive receivers of care while in hospital after the stroke. The interactions with the multidisciplinary team were viewed as assessments, and descriptions of a coordinated multi-disciplinary approach to rehabilitation were lacking.

Emergent passivity versus participatory enablement

When discharged from hospital, seven of the informants that went directly home experienced the decision as sudden and premature. All but one described being told that they were to be discharged, some only a couple of hours before leaving the ward.

I wasn’t part of the decision at all. I haven’t asked my husband, but I guess the nurses and the doctors there thought it would be good. I thought it was too soon. I didn’t say anything either. In a way, you just have to do as you´re being, well, as they tell you. But I can remember thinking: this has to be way too soon. (ID 14)

Two informants did not feel ready to go home, while others looked forward to home comforts, such as a familiar bed or a home-cooked meal. One was unable to remember anything from the day of discharge. Some informants believed they were discharged because all the necessary assessments had been performed, and one did not think the stroke unit had more to offer as he was quite independent. The anticipation of physiotherapy, three times a week for twelve weeks, afforded a sense of security for those discharged to their home.

When discharged to a rehabilitation unit, experiences varied between being told about the transfer to being asked if they were interested in going. Three informants described having mixed feelings about rehabilitation, fearing the association with “elderly” people or the prospect of “becoming stuck” in an institution. Seven informants transferred to in-patient rehabilitation. Experiences from the rehabilitation units were characterized by structure and team work. The informants positively highlighted being an active member in team meetings and goal-setting discussions.

It´s about how you´re being met […]. That everyone in the team stops by for a talk, that you´re being asked questions about how you´re feeling, how you view your situation […]. How you think and feel. That it shows that they care, that they take the time with the patient and focus on them. (ID 15)

Informants valued the fact that staff were engaged on their behalf; this helped maintain both motivation and a sense that their care was the main focus. Developing independence in personal care was still a priority, and several informants worked hard toward this goal on their own. The informants had regular physiotherapy and occupational therapy while in the rehabilitation unit, and several had more than one session per day. Some performed independent exercises, but most had no other activities outside of formal therapy sessions.

Returning home after a stroke was a mixed experience for many informants, characterized by both relief and frustration. Some felt comfort in being able to relax and were eager to return to their families and daily routines. However, increased demands at home, such as elevated activity levels, parenting or caring responsibilities, led to the discovery of difficulties that were not obvious while in hospital, such as fatigue, balance problems, struggles with reading and writing, and mood changes.

I get more tired when walking now than just after the stroke, perhaps its normal. They talk about aftershocks after an earthquake, perhaps that’s what it is, I guess it’s the proper term. (ID 13)

One said that her family found her to be angrier than before and that her speech problems led to misunderstandings and frustration. Another found it difficult to go out for coffee with his wife as he did before, because he “took in” all the noise in the café, which made him tired.

Yes, the invisible things. They tell me I look so well and that I´m just like before, and I think: you should have known, but they can´t see that the head suddenly will not work and that I have to lie down. (ID 10)

These issues were more commonly raised among those being discharged directly home from the hospital stroke unit. Informants in the intermediate rehabilitation unit had the opportunity to gradually habituate with home visits or short leaves and thus felt more prepared for life at home.

All the informants participated in out-patient physiotherapy, and some received help with medications and showering from community nursing staff. None reported follow-up from any other professions. Despite the fact that several struggled with cognitive issues and fatigue that limited their participation in work, family life, or social activities, they were able to keep up with the intensive physiotherapy program. For some, the training sessions represented a positive element in their everyday life, while others saw it as a necessity, but not a particularly enjoyable one. Noticing signs of progress, such as increased strength or balance, was emphasized as positive and motivating.

I was very unsteady at first. Most of the exercises are difficult, but lately I have been looking forward to them. As I have felt how positive everything has been on my balance and strength, I have become more positive myself. (ID 5)

At the time of the interview, several informants had finished their 12-week course and expressed a desire to continue their training. Several also performed independent exercises in addition to their physiotherapy treatment. For a period, some were provided with home exercises only, due to prohibitions against one-on-one physiotherapy treatments invoked during the Covid-19 pandemic. All found them difficult to execute, as they felt dependent upon the support and motivation provided by their physiotherapist.

Several informants lived in rural areas, and the post-stroke prohibition against driving for at least six months had significant consequences: impeding a return to work; increasing dependence upon family members; and for those living alone engendering social isolation and loneliness.

Discussion

One of the major findings of this study is that the culture and protocols of hospitals discourage active patient participation for people who have survived a stroke, despite its high importance during the period spent there. Patient participation fluctuates significantly throughout the course of a stroke and rehabilitation. Participation varies from patients being active agents, or autonomous subjects and decision-makers when a stroke hits, to becoming passive receivers of treatment and care while in hospital. Such changes may have lasting consequences after discharge. Furthermore, patient participation is characterized participatory enablement in the rehabilitation unit and in the community. Based on this, and informed by enactive theory, one may ask how participation depends on both individual autonomy and the context of interactions.

Autonomy: a prerequisite for patient participation – lost on the assembly line?

The immediate bodily changes attendant to stroke onset, which informants described mainly as an inability to perform familiar tasks, differ from those reported previously, as here they were less associated with distinct traumatic experiences (Connolly and Mahoney, Citation2018; Simeone et al., Citation2015). The autonomy of both individuals and interaction processes is by nature precarious and may be threatened by bodily changes, such as those caused by a stroke (De Jaegher, Peräkylä, and Stevanovic, Citation2016). A threat to an autonomous system such as the individual’s identity demands adaptations involving a regulation of the relationship to the environment and internal states (Stilwell and Harman, Citation2019).

The fact that several informants opted to wait-and-see before seeking medical help is consistent with previous research in which laypersons did not categorize common stroke symptoms as a medical emergency (Li, Galvin, and Johnson, Citation2002). The informants report a distinct perception that ‘something is not right.’ This perception seems mainly triggered by the experience of “becoming unable” rather than by a recognition of specific neurological symptoms. Nevertheless, this triggers a need for adaptation to preserve identity (Stilwell and Harman, Citation2019) and this we posit is when the participants decide to get help. Excepting those who lost consciousness, the informants were still agents and active decision-makers in their own lives deciding if, how, and when to seek help.

Admission to hospital (i.e. becoming a patient) alters the roles and contexts connected to individual autonomy and changes the parameters of active participation. The rules and practices that are the basis for the autonomy of interactions between patients and health professionals are largely pre-coordinated, in the sense that they act together according to their roles in, or the conventions of, the institution (De Jaegher, Peräkylä, and Stevanovic, Citation2016). In the acute management of a stroke the inherent conventions of a hospital environment, both physical and social, reduce the autonomy of the individual into “a case” to be solved, like an item on an assembly line. This approach does however serve a purpose. Every minute counts when aiming to reduce damage to the brain, and the systematic efficiency and timeliness of measures can significantly optimize survival and function (Risitano and Toni, Citation2020). In this context there is meaning in letting the medical personnel take over to ensure bodily/identity protection. The cost is however that the autonomy of the individual is reduced, and our findings suggest that it may have prolonged consequences on participation.

The reduction of autonomy is evident in the way that patients submit to the hospital system and become passive receivers of treatment and care. The inactive and sedate time reported in our study is consistent with other investigations of patient activity levels in stroke units (Field et al., Citation2013; Normann, Arntzen, and Sivertsen, Citation2019; West and Bernhardt, Citation2012). Our results suggest that the level of activity, and thus active participation while in the stroke unit, remains unchanged despite concerns having been raised for many years. The long-term consequences on participation have not been previously highlighted. Additionally, descriptions of coordinated multidisciplinary early rehabilitation, involving active patient participation as outlined in several stroke guidelines (Lindsay et al., Citation2014; Norrving et al., Citation2018; Norwegian Directorate of Health, Citation2017) are lacking in our data. Despite caution being taken with regards to mobilization in the very early (< 24 hours) stages of a stroke (Langhorne et al., Citation2017) there are few reasons for further delay if the patient is medically stable and able to tolerate it (Bernhardt, Godecke, Johnson, and Langhorne, Citation2017; Winstein et al., Citation2016). This period of time is an important window of opportunity in terms of brain plasticity (Brodal, Citation2010; Langhorne and Ramachandra, Citation2020). As experiences and activities guide the brain’s remodeling processes (Brodal, Citation2010), it is remarkable that the stroke units allow for inactivity. It is worth investigating whether the focus on acute care and its temporal demands along with the uncertainties surrounding the safety and amount of very early mobilization has displaced rehabilitation from the stroke unit more than is warranted.

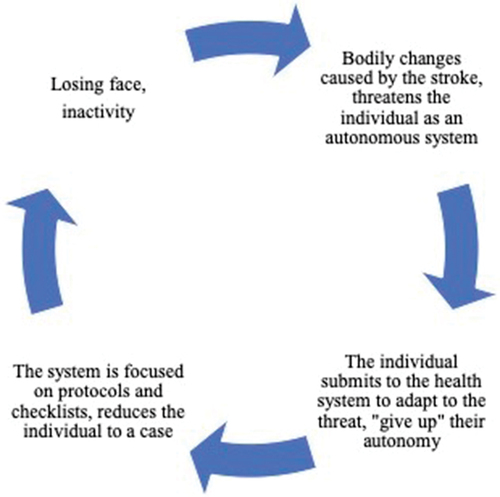

The informants’ descriptions of passivity and exclusion from decision-making are seemingly connected with the pre-coordinated patterns of these early and very institutionalized interactions. The informants did not question or oppose this praxis but accepted it and expressed that ‘you just do as you’re told.’ The negative impact that paternalism in health care has on patient participation has been previously reported (Peoples, Satink, and Steultjens, Citation2011; Proot, ter Meulen, Abu-Saad, and Crebolder, Citation2007). The exception to the stated passivity is that the majority of informants made an active effort to be independent with regards to personal care. This indicates that such tasks are of great significance, and that dependence threatens one’s sense of autonomy. Losing dignity in these situations was highlighted by the informants as negative experiences. Some expressed mixed feelings toward in-patient rehabilitation; they recognized it as beneficial to recovery but associated it with disability and institutionalization. From an enactive perspective, we believe these experiences are best explained in terms of vulnerability in social interactions where the socially-recognized self-image, or how the individual is viewed by others, is at stake or in danger of “losing face” (De Jaegher, Peräkylä, and Stevanovic, Citation2016; Goffman, Citation1983). De Jaegher, Peräkylä, and Stevanovic (Citation2016) stated that “our images as competent human actors, as men or women, or as incumbents of any other social identity are in the hands of our interaction partners.” It seems that in terms of autonomy the bodily changes caused by the stroke, the pre-coordination to the norms of behavior in a hospital, and the fear of losing face mutually reinforce the reduction in autonomy and thus diminish or somehow hollow out the basic and essential prerequisites for participation (). While the initial reduction of autonomy may serve a purpose, the reduction in autonomy attendant to hospital culture should be conscientiously balanced against patient participation. In practical terms this means that wherever possible restrictions on participation should not be prolonged beyond the acute medical assessment and treatment.

Facilitation of participation through partnership in interactions

Rehabilitation is most effective when organized, from diagnosis to recovery, by coordinated stroke rehabilitation teams (Hartford, Lear, and Nimmon, Citation2019). For many, including those in our study, the stay in the stroke unit is the only period offering access to multidisciplinary treatment as such services are not commonly available in the community (Bernhardt, Godecke, Johnson, and Langhorne, Citation2017; Winstein et al., Citation2016). Lack of teamwork or poor communication between people who had a stroke and health professionals, may compromise and disempower the rehabilitation process with potential to diminish autonomous participation, confidence, and motivation (Hartford, Lear, and Nimmon, Citation2019; Luker et al., Citation2015; Voogdt-Pruis et al., Citation2019). This dynamic is affirmed by the fact that those informants who spent time in a rehabilitation unit between acute admission and return home described a smoother transition and saw themselves as better prepared for life at home. Our findings indicate that their time in the rehabilitation unit had strengthened their autonomy, making it easier to meet increasing demands and to participate actively in their life after discharge. We consider this a direct result of the facilitation of interdependent autonomy, and thus of participation through coordinated teamwork in the rehabilitation unit. The informants described efforts targeted to the challenges specific to their daily lives, and they recalled being actively involved in decision-making and goal-setting. The pre-coordination of behavior in such a unit seems to be characterized by partnership and increased participation from patients in their interactions with health professionals. With what we call “partnership” here, we refer to the medical professional creating an opening in their interactions with patients for the latter’s active participation in these interactions. Patient and physiotherapist are partners in the recovery journey, even if their contributions are necessarily asymmetrical, since one is a person in need and the other is an expert guide. To work properly, however, the rehabilitation process needs an opening to be made for active participation on the part of the health expert, and an uptake of this more active role on the part of the patient. From an enactive point of view, sense-making or meaning is generated between persons participating in interaction, and the partnership described between the patient and the staff at the rehabilitation unit reinforces the creation of meaningful action in therapy and activity. This view is supported by Luker et al. (Citation2015) who stated that good communication and information during rehabilitation could directly foster autonomy through their positive influence on patient engagement. Among our informants, the support from the physiotherapist and the progress experienced in training crucially contributed to continuity and motivation during both in and out-patient treatment. The value of such a facilitator was struck into relief by the lockdown in March 2020 which occasioned an abrupt cessation of physiotherapy treatments. Many informants found it difficult to maintain exercises at home on their own. In this context there is no doubt a need to further explore precisely how physiotherapists function as motivators.

For those discharged directly home from the stroke unit, the transition represented a breach where resuming usual tasks at home and social interactions became difficult, even for those who felt they were ready. Our findings are in line with other studies that have found that both patients and caregivers feel unprepared for the transition from hospital to home (Faux et al., Citation2018; Gustafsson and Bootle, Citation2013). Other authors propose that rehabilitation needs, particularly in mild strokes, are commonly overlooked due to a lack of awareness of and sensitive assessment for cognitive problems, depression, or apathy (Faux et al., Citation2018). Several informants described that unexpected difficulties such as fatigue or cognitive problems, only surfaced after returning home. Some saw this as a deterioration, one which they were not helped in addressing since none received cognitive rehabilitation or counseling in the community. We interpret this less as an absolute deterioration than as a result of a discrepancy between the patient’s actual and expected levels of autonomy; a discrepancy occasioned by the abrupt increase in demands and the lack of support when transitioning from “an object on the assembly line” or an individual in the hospital system to an active participant in the life world system.

Limitations

This study was conducted in two regions in Norway which somewhat limits the findings to the Scandinavian health care system. However, guidelines for stroke rehabilitation and patient participation are international, and applying concepts from enactive theory serves as a theoretical generalization (Malterud, Citation2015). We strategically sampled participants aiming for a broad representation. That said, we cannot rule out the possibility that participants who were excluded may have been able to add valuable contributions. Furthermore our sample is influenced by the criteria for participation in the RCT which omitted those with more severe disabilities. No specific cognitive or mental assessments except ruling out dementia were made. Due to the pandemic some interviews were delayed which might have introduced recall bias. However, our impression was that most participants recalled these events clearly.

Implications for practice

Health care professionals should be mindful of the importance of interdependent autonomy for participation, from the early stroke rehabilitation phase throughout the whole process of returning to local communities. This implies making activity and participation possible in the hospital setting and providing increased access to multidisciplinary support in the community. Attention to these notions is of particular importance for physiotherapists as it may motivate and facilitate activity for people who have survived a stroke throughout the whole rehabilitation continuum as an active partnership between patient and expert.

Conclusion

The present study elucidates how participation is important and how it is precarious and dependent upon both individual autonomy and social and institutional context. Bodily changes, the roles of both patient and health care professionals, and the hospital context mutually reinforce a reduction in autonomy after a stroke. These effects seem to last beyond discharge from hospital. Our results point to the usefulness of considering individual autonomy as a prerequisite for participation, a view that clarifies how partnership, activity, multidisciplinary support, and bodily improvements may strengthen autonomy and promote participation. This potential for promoting participation seems underutilized, particularly in the early phase of rehabilitation, but also in the community setting.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the individuals who participated in this study, the Nordland and Nord-Trøndelag Hospital Trusts for their support and for contributing to data collection, the participating hospitals and municipalities, and the user representative.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. I-CoreDIST: Individualized Core activation combined with DISTal functional movement. I = individualized, Core = trunk, D = dual task, I = intensive, S = specific, stability, somatosensory stimulation, T = teaching, training.

2. An 11-item scale used to quantify the impairment caused by a stroke. A score of 0 indicates normal function while a higher score is indicative of some level of impairment. Maximum score is 42.

References

- Bernhardt J, Godecke E, Johnson L, Langhorne P 2017 Early rehabilitation after stroke. Current Opinion in Neurology 30(1): 48–54. doi:10.1097/WCO.0000000000000404.

- Brinkmann S, Kvale S 2015 InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd) ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Brodal P 2010 The central nervous system. Structure and function. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Connolly T, Mahoney E 2018 Stroke survivors’ experiences transitioning from hospital to home. Journal of Clinical Nursing 27(21–22): 3979–3987. doi:10.1111/jocn.14563.

- Cresswell JW, Poth CN 2018 Qualitative inquiry and research design. Choosing among five approaches. (4th), London: Sage Publications Ltd.

- De Jaegher H, Di Paolo E 2007 Participatory sense-making: An enactive approach to social cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 6(4): 485–507. doi:10.1007/s11097-007-9076-9.

- De Jaegher H, Peräkylä A, Stevanovic M 2016 The co-creation of meaningful action: Bridging enaction and interactional sociology. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society London. Series B, Biological Sciences 371(1693): 20150378. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0378.

- Di Paolo E, Rohde M, De Jaegher H 2010 Horizons for the enactive mind: Values, social interaction and play. In: Stewart J, Gapenne O, Di Paolo E (Eds) Enaction: Toward a new paradigm for cognitive science. Cambridge: Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Elloker T, Rhoda AJ 2018 The relationship between social support and participation in stroke: A systematic review. African Journal of Disability 7: 357. doi:10.4102/ajod.v7i0.357.

- Eriksson G, Baum MC, Wolf TJ, Connor LT 2013 Perceived participation after stroke: The influence of activity retention, reintegration, and perceived recovery. American Journal of Occupational Therapy 67(6): 131–138. doi:10.5014/ajot.2013.008292.

- Ezekiel L, Collett J, Mayo NE, Pang L, Field L, Dawes H 2019 Factors associated with participation in life situations for adults with stroke: A systematic review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 100(5): 945–955. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2018.06.017.

- Faux SG, Arora P, Shiner CT, Thompson-Butel A, Klein L 2018 Rehabilitation and education are underutilized for mild stroke and TIA sufferers. Disability and Rehabilitation 40(12): 1480–1484. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1295473.

- Field MJ, Gebruers N, Shanmuga Sundaram T, Nicholson S, Mead G 2013 Physical activity after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Scholarly Research Notices 2013: 464176.

- Foley EL, Nicholas ML, Baum CM, Connor LT 2019 Influence of environmental factors on social participation post-stroke. Behavioural Neurology 2019: 2606039. doi:10.1155/2019/2606039.

- Fuchs T, De Jaegher H 2009 Enactive intersubjectivity: Participatory sense-making and mutual incorporation. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 8(4): 465–486. doi:10.1007/s11097-009-9136-4.

- Goffman E 1983 The interaction order: American Sociological Association, 1982 Presidential Address. American Sociological Review 48(1): 1–17. doi:10.2307/2095141.

- Gustafsson L, Bootle K 2013 Client and carer experience of transition home from inpatient stroke rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation 35(16): 1380–1386. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.740134.

- Hartford W, Lear S, Nimmon L 2019 Stroke survivors’ experiences of team support along their recovery continuum. BMC Health Services Research 19(1): 723. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4533-z.

- Hay ME, Connelly DM, Kinsella EA 2016 Embodiment and aging in contemporary physiotherapy. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 32(4): 241–250. doi:10.3109/09593985.2016.1138348.

- Jones F, Gombert K, Honey S, Cloud G, Harris R, Macdonald A, McKevitt C, Robert G, Clarke D 2021 Addressing inactivity after stroke: The Collaborative Rehabilitation in Acute Stroke (CREATE) study. International Journal of Stroke 16(6): 669–682. doi:10.1177/1747493020969367.

- Lahelle AF, Øberg GK, Normann B 2020 Physiotherapy assessment of individuals with multiple sclerosis prior to a group intervention – A qualitative observational and interview study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 36(3): 386–396. doi:10.1080/09593985.2018.1488022.

- Langhorne P, Ramachandra S 2020 Organised inpatient (stroke unit) care for stroke: Network meta‐analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD000197. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000197.pub4.

- Langhorne P, Wu O, Rodgers H, Ashburn A, Bernhardt J 2017 A Very Early Rehabilitation Trial after stroke (AVERT): A phase III, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment 21(54): 1–120. doi:10.3310/hta21540.

- Légaré F, Adekpedjou R, Stacey D, Turcotte S, Kryworuchko J, Graham ID, Lyddiatt A, Politi MC, Thomson R, Elwyn G et al. 2018 Interventions for increasing the use of shared decision making by healthcare professionals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7: CD006732. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006732.pub4.

- Li J, Galvin HK, Johnson SC 2002 The “prudent layperson” definition of an emergency medical condition. American Journal of Emergency Medicine 20(1): 10–13. doi:10.1053/ajem.2002.30108.

- Lindsay P, Furie KL, Davis SM, Donnan GA, Norrving B 2014 World Stroke Organization Global Stroke Services Guidelines and Action Plan. International Journal of Stroke 9(Suppl A100): 4–13. doi:10.1111/ijs.12371.

- Luker J, Lynch E, Bernhardsson S, Bennett L, Bernhardt J 2015 Stroke Survivors‘ Experiences of Physical Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 96(9): 1698–1708. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.03.017.

- Mallinson TP, Hammel JP 2010 Measurement of participation: Intersecting person, task, and environment. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 91(9): 29–33. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2010.04.027.

- Malterud K 2012 Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 40(8): 795–805. doi:10.1177/1403494812465030.

- Malterud K 2015 Theory and interpretation in qualitative studies from general practice: Why and how?. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 44(2): 120–129. doi:10.1177/1403494815621181.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD 2016 Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research 26(13): 1753–1760. doi:10.1177/1049732315617444.

- Martinez-Pernia D 2020 Experiential Neurorehabilitation: A Neurological Therapy Based on the Enactive Paradigm. Frontiers in Psychology 11: 924. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00924.

- Normann B 2020 Facilitation of movement: New perspectives provide expanded insights to guide clinical practice. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 36(7): 769–778. doi:10.1080/09593985.2018.1493165.

- Normann B, Arntzen EC, Sivertsen M 2019 Comprehensive core stability intervention and coordination of care in acute and subacute stroke rehabilitation - A pilot study. European Journal of Physiotherapy 21(4): 187–196. doi:10.1080/21679169.2018.1508497.

- Norrving B, Barrick J, Davalos A, Dichgans M, Cordonnier C, Guekht A, Kutluk K, Mikulik R, Wardlaw J, Richard E et al. 2018 Action plan for stroke in Europe 2018-2030. European Stroke Journal 3(4): 309–336. doi:10.1177/2396987318808719.

- Norwegian Directorate of Health 2017 Nasjonal Faglig Retningslinje for Behandling og Rehabilitering ved Hjerneslag [National guidelines for treatment and rehabilitation in stroke]. Oslo, Norway. https://helsedirektoratet.no/retningslinjer/hjerneslag

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA 2014 Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine 89(9): 1245–1251. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388.

- Palstam A, Sjödin A, Sunnerhagen KS 2019 Participation and autonomy five years after stroke: A longitudinal observational study. PLoS One 14(7): e0219513. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0219513.

- Paolucci S, Di Vita A, Massicci R, Traballesi M, Bureca I, Matano A, Iosa M, Guariglia C 2012 Impact of participation on rehabilitation results: A multivariate study. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine 48(3): 455–466.

- Paulgaard G 1997 Feltarbeid i egen kultur: Innenfra, utefra eller begge deler? [Fieldwork in their own culture: From within, from outside or both?. In: Fossåskåret E, Fuglestad OL, Aase TH (Eds) Metodisk Feltarbeid. Produksjon og Tolkning av Kvalitative Data [Methodical Fieldwork. Production and Interpretation of Qualitative Data], pp. 70–93. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Peoples H, Satink T, Steultjens E 2011 Stroke survivors’ experiences of rehabilitation: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy 18(3): 163–171. doi:10.3109/11038128.2010.509887.

- Phipps MS, Cronin CA 2020 Management of acute ischemic stroke. British Medical Journal 368: l6983. doi:10.1136/bmj.l6983.

- Proot IM, ter Meulen RH, Abu-Saad HH, Crebolder HF 2007 Supporting stroke patients’ autonomy during rehabilitation. Nursing Ethics 14(2): 229–241. doi:10.1177/0969733007073705.

- Risitano A, Toni D 2020 Time is brain: Timing of revascularization of brain arteries in stroke. European Heart Journal Supplements 22(Supplement_L): L155–L159. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/suaa157.

- Simeone S, Savini S, Cohen MZ, Alvaro R, Vellone E 2015 The experience of stroke survivors three months after being discharged home: A phenomenological investigation. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing 14(2): 162–169. doi:10.1177/1474515114522886.

- Stilwell P, Harman K 2019 An enactive approach to pain: Beyond the biopsychosocial model. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 18(4): 637–665. doi:10.1007/s11097-019-09624-7.

- Thompson E 2007 Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology, and the Sciences of Mind. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Varela FJ, Thompson E, Rosch E 2016 The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience (6th) ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Voogdt-Pruis HR, Ras T, van der Dussen L, Benjaminsen S, Goossens PH, Raats I, Boss G, van Hoef EF, Lindhout M, Tjon-A-Tsien MR et al. 2019 Improvement of shared decision making in integrated stroke care: A before and after evaluation using a questionnaire survey. BMC Health Services Research 19(1): 936. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4761-2.

- West T, Bernhardt J 2012 Physical activity in hospitalised stroke patients. Stroke Research and Treatment 2012: 813765. doi:10.1155/2012/813765.

- Winstein CJ, Stein J, Arena R, Bates B, Cherney LR, Cramer SC, Deruyter F, Eng JJ, Fisher B, Harvey RL et al. 2016 Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 47(6): e98–e169. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000098.

- World Health Organization 2013 How to Use the ICF: A Practical Manual for Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Appendix 1

Table A1. Initial interview guide.

Appendix 2

Table A2. Amended interview guide.