ABSTRACT

Background

Access to pain education for healthcare professionals is an International Association for the Study of Pain's key recommendation to improve pain care. The content of preregistration and undergraduate physical therapy pain curricula, however, is highly variable.

Objective

This study aimed to develop a list, by consensus, of essential pain-related topics for the undergraduate physical therapy curriculum.

Methods

A modified Delphi study was conducted in four rounds, including a Delphi Panel (N = 22) consisting of in pain experienced lecturers of preregistration undergraduate physical therapy of Universities of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands, and five Validation Panels. Round 1: topics were provided by the Delphi Panel, postgraduate pain educators, and a literature search. Rounds 2–4: the Delphi Panel rated the topics and commented. All topics were analyzed in terms of importance and degree of consensus. Validation Panels rated the outcome of Round 2.

Results

The Delphi Panel rated 257, 146, and 90 topics in Rounds 2, 3, and 4, respectively. This resulted in 71 topics judged as “not important,” 97 as “important,” and 89 as “highly important.” In total, 63 topics were rated as “highly important” by the Delphi Panel and Validation Panels.

Conclusion

A list was developed and can serve as a foundation for the development of comprehensive physical therapy pain curricula.

Introduction

The widespread prevalence and also the large global burden of musculoskeletal (MSK) pain (i.e., four MSK-related diseases in top 11 ranking among 354 diseases) demonstrate the need for comprehensive education in pain for all healthcare professionals (HCPs) (Briggs, Carr, and Whittaker, Citation2011; Goldberg and McGee, Citation2011; Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Citation2019; International Association for the Study of Pain, Citation2011; Jackson et al., Citation2015; Rice, Smith, and Blyth, Citation2016). The major deficits in knowledge, attitudes, and skills of (student) HCPs about the mechanisms and management of pain are one of the reasons that pain management is inadequate worldwide (Giordano and Boswell, Citation2011; International Association for the Study of Pain, Citation2010; Miles, Kellett, and Leinster, Citation2017; Thompson, Citation2009; Thompson, Johnson, Milligan, and Briggs, Citation2018). To counteract this, education in pain is one of the cornerstones advocated in the National Pain Strategies of the International Association for the study of Pain (International Association for the Study of Pain, Citation2011). Education in pain for HCPs in general is often limited, fragmented, inadequately addressed, and inconsistent in the preregistration undergraduate health curricula of medicine, nursing, and physical therapy (Briggs, Carr, and Whittaker, Citation2011; Doorenbos et al., Citation2013; Gallagher et al., Citation2000; Institute of Medicine, Citation2011; Jones, Citation2009; Shipton et al., Citation2018). The documented content of these pain curricula is highly variable and often dominated by the biomedical model (Briggs et al., Citation2015; Briggs, Carr, and Whittaker, Citation2011; Doorenbos et al., Citation2013; Ehrström, Kettunen, and Salo, Citation2018; Giordano and Boswell, Citation2011; Hoeger Bement et al., Citation2014; Leegaard, Valeberg, Haugstad, and Utne, Citation2014; Mezei and Murinson, Citation2011; Murinson, Mezei, and Nenortas, Citation2011; Pöyhiä, Niemi-Murola, and Kalso, Citation2005; Shipton et al., Citation2018; Thompson, Johnson, Milligan, and Briggs, Citation2018; Watt-Watson et al., Citation2009), and often lacking essential content related to current pain (neuro)science (Briggs et al., Citation2015; Briggs, Carr, and Whittaker, Citation2011; Ehrström, Kettunen, and Salo, Citation2018). Education about pain tends to ignore the biopsychosocial framework; despite being advocated in clinical guidelines, cognitive-behavioral methods and multidisciplinary management receive limited or no attention (Ehrström, Kettunen, and Salo, Citation2018; Loeser, Citation2015; Scudds, Scudds, and Simmonds, Citation2001; Sessle, Citation2012).

Whereas the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy targets all levels of physical therapy training, the European Pain Federation (EFIC) targets postgraduates (European Pain Federation, Citation2019; Fishman et al., Citation2013; Hoeger Bement et al., Citation2014; International Association for the Study of Pain, Citation2018). Additionally, most research is into the postgraduate area (Hush, Nicholas, and Dean, Citation2018). Although the IASP core curriculum is helpful for curriculum designers of physical therapy programs, the outline is limited to describing competences and learning objectives, and guidance is lacking on the specific content (Hunter et al., Citation2008; Jones, Citation2009; Watt-Watson et al.,Citation2004). Considerable variation exists in the content of education about pain for physical therapy between countries (Hoeger Bement and Sluka, Citation2015; Scudds, Scudds, and Simmonds, Citation2001). An unpublished pilot inventory of pain content in physical therapy courses at the Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS) in the Netherlands revealed substantial differences in content, volume, and competence levels even within the country.

Even though increasingly more physical therapists recognize the multidimensional nature of chronic pain and the importance of self-management, systematically and adequately addressing psychological factors remains challenging (Cowell et al., Citation2018; Denneny et al., Citation2020; Singla, Jones, Edwards, and Kumar, Citation2015; Verwoerd et al., Citation2022). Given that physical therapists are frontline clinicians in pain management (Beswick et al., Citation2012; Edgerton et al., Citation2019; Kehlet, Jensen, and Woolf, Citation2006; Pendergast, Kliethermes, Freburger, and Duffy, Citation2012; Van Gorp et al., Citation2015; Wylde et al., Citation2015), preregistration undergraduate courses must integrate specific knowledge and skills and contain the latest evidence to prepare them to manage pain effectively (Briggs, Carr, and Whittaker, Citation2011; Cowell et al., Citation2018; Hoeger Bement et al., Citation2014; International Association for the Study of Pain, Citation2011; Synnott et al., Citation2015). Because the importance of education in pain is widely recognized, a description based on consensus of required content on a preregistration undergraduate level is needed.

This study aimed to identify a widely consented set of essential topics in the preregistration, undergraduate pain curriculum of the Dutch physical therapy program by consulting experts in the field of higher education and pain. The research question was: “What are the essential pain-related topics in pain evaluation and management that should be integrated within the curriculum of preregistration undergraduate physical therapy students to enable them to treat patients with pain according to applicable guidelines?”

Methods

Design

A modified Delphi study was administered online from February 2020 to May 2021. Four rounds were used to generate consensus between experts (Becker and Roberts, Citation2009; Hasson, Keeney, and McKenna, Citation2000; Keeney and McKenna, Citation2005; Okoli and Pawlowski, Citation2004; Skulmoski, Hartman, and Krahn, Citation2007; Thompson, Citation2009; Wilson, Averis, and Walsh, Citation2003). Feedback was collected and was forwarded to the next round, including a summary of comments and statistical measures (Murphy et al., Citation1998). In order to prevent group bias, national bias, and bandwagon effects, five special interest group Validation Panels were used in a single round. The results of the Validation Panels were combined with the results of the Delphi Panel to compose a consented set of essential pain-related topics for the preregistration undergraduate curriculum of physical therapists. Formal ethical review was not needed as judged by the medical ethics committee at the University Medical Center of Groningen (M21.289289). All participants provided written informed consent prior to the beginning of the survey. Guidance on Conducting and Reporting Delphi Studies was followed (O’Brien et al., Citation2014).

Participants Delphi Panel

The Delphi Panel experts were recruited from pain experienced physical therapy lecturers from all UAS in the Netherlands. Participants were eligible if they met the predetermined criteria: (1) have a minimum of 5 years of professional educational experience on the topic of pain; (2) involvement in pain-related curriculum development and teaching in it; and (3) willing and able to dedicate the time required for Delphi rounds. We aimed to form a panel of at least 20 experts to include sufficient expertise and diversity to cover pain’s multidimensional aspects and derive representative results (Jorm, Citation2015). Potential participants were informed by e-mail about the purpose and procedure of contributing as experts.

Participants Validation Panels

Five special interest group Validation Panels were used as a bias-reducing filter: Panel (1) early career physical therapists; 4th-year Bachelor physical therapy students with minimally 20-week internship experience and physical therapists up until 1-year work experience (i.e., reference for the prospective curriculum “consumers”); Panel (2) physical therapists with a minimum of 5 years working experience (i.e., reference for the broader work field of physical therapy); Panel (3) non-pain lecturers in the field of higher education of physical therapy (i.e., reference for less pain oriented, but higher education focused lecturers); Panel (4) postgraduate pain educators: educators of accredited postgraduate pain courses that are commercially accessible, including general practitioners, physician assistants, psychologists, occupational therapists, psychosomatic physical therapists, pediatric physical therapists, and manual therapists; and Panel (5) IASP and EFIC representatives: physical therapy pain curriculum committee members (i.e., international reference and content experts in the field of pain curricula). The national Validation Panels were recruited by Delphi Panel members, the associated UAS, social media, and a message in the online newsletter of the Dutch Physical Therapy Association. Pain educators in postgraduate pain courses were recruited using a database of accredited courses from the Dutch Physical Therapy Association. EFIC and IASP representatives were contacted by e-mail.

Procedures, Rating, and Analysis

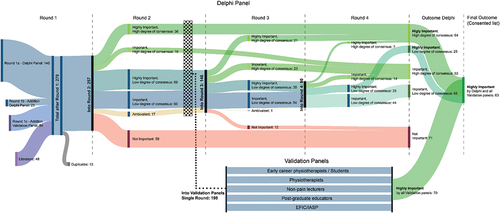

A web-based survey (Survey Monkey Company, Palo Alto, CA, USA) was used for all four rounds of the Delphi Panel and a single round of each Validation Panel. The invitation included instructions to take in mind preceding participation in the round: (1) the general level of competence of physical therapy education is on a preregistration undergraduate level; (2) what is minimal necessary (i.e., the curriculum space is limited); and (3) indicate the importance of the pain topic itself free of competence sublevel (i.e., degree of expertise) within the undergraduate level (Bergsmann et al., Citation2015). Members had four weeks to fill in the survey in every round, and a reminder was sent halfway through. All Delphi Panel members participated independently and anonymously. A total of four rounds were determined a priori ().

Delphi Panel

First round

The aim was to collect and define as many relevant pain topics as possible. The first round was an open consultation round in three steps: (1) the Delphi Panel was asked to liberally list as many pain topics as possible. The topics submitted by the individual participants were taken together and combined into one list by the first two authors (RR and AB); (2) the Delphi Panel was asked to verify the list and add topics if necessary; and (3) the list was provided to pain educators of accredited postgraduate pain courses (Validation Panel 4), who were asked to add omitted topics (Keeney and McKenna, Citation2005; Trevelyan and Robinson, Citation2015; Wilson, Averis, and Walsh, Citation2003). For completeness, existing IASP and EFIC curricula literature was screened to identify any additional topics. After data collection, duplicates between topics derived in steps 2 and 3 were removed, and the first two authors categorized all topics.

Second round

The aim was to rate and possibly reduce the number of First Round topics. Participants of the Delphi Panel were asked which topics are important for a starting physical therapist to treat patients with pain in daily practice according to applicable guidelines and state-of-the-art knowledge. For each topic, the panelists were asked “Rate per topic to what extent you consider this topic important for the preregistration undergraduate physical therapy pain curriculum.” The participants rated each topic on a 5-point Likert scale: (1) very unimportant; (2) unimportant; (3) important; (4) very important; and (5) extremely important. There was an additional “no opinion” option that could be used when the participant could not judge it to prevent uninformed response bias (Becker and Roberts, Citation2009; Trevelyan and Robinson, Citation2015). To avoid ceiling effects, a 5-point Likert scale was used with three positive choices (i.e., extremely important, very important, and important) and two negative choices (i.e., very unimportant and unimportant) (Crow et al., Citation2002; Lozano, García-Cueto, and Muñiz, Citation2008; Moret et al., Citation2007). For each category, comments could be left.

Third round

The aim was to reach consensus on Second Round topics emphasizing those topics on which no consensus had been reached. Summarized comments per cluster were presented together with statistical information (i.e., percentages and bar charts) to inform the Delphi Panel on topics that have gained collective opinion (see analysis). The Delphi Panel members were asked to rerate the topics based on the group’s opinion (i.e., statistical information and comments). During the round, Delphi panel members were asked to comment on all ambivalent topics next to general comments.

Fourth round

The aim and organization of the Fourth Round were identical to the Third Round and can be seen as a further iteration of the process. Extra information was added when comments revealed a misunderstanding of the ambivalent topics.

Validation Panels

In a single round, all Validation Panels were asked to judge the topics rated as important, very important, and extremely important, based on the analysis of Round 2 of the Delphi Panel. Unimportant topics were removed to reduce the completion time, consequently increasing the potential number of responses in the Validation Panels and reducing attention bias. Incomplete lists defined as missing three ratings or more consecutively and lists with a fill-in time smaller than 5 min were excluded to prevent careless responding (Goldammer, Annen, Stöckli, and Jonas, Citation2020; Huang et al., Citation2012).

Analysis

A response rate of 70% for each round of the Delphi Panel was considered sufficient (Sumsion, Citation1998). After the First Round, the collected topics were content analyzed, and duplicates were removed and pragmatically categorized into nine categories, partly overlapping the categorization used in the IASP and EFIC curricula (Table S2) (Keeney, Hasson, and McKenna, Citation2010; Keeney and McKenna, Citation2005). Authors (RR & AB) independently aggregated and identified responses. A consensus meeting took place to resolve any disagreements. A stepwise procedure was followed in all rounds to analyze the importance based on group position and degree of consensus (i.e., agreement or certainty based on group dispersion) of all topics (). Criteria for importance were based on the median, whereas criteria for consensus were based on percentage agreement and the interquartile range (IQR), rather than the mean and standard deviations, to reduce the influence of outliers in judgment (Trevelyan and Robinson, Citation2015). The choice of “no opinion” was excluded in all calculations.

Table 1. Importance and degree of consensus of topics.

Initially, all topics with highly variable ratings (IQR ≥ 2.5) were categorized as ambivalent and remained for the next round for reevaluation (Hasson, Keeney, and McKenna, Citation2000; Keeney and McKenna, Citation2005; Sumsion, Citation1998). Then, topics were categorized as unimportant, important, or highly important: unimportant when rated as important (3 or higher on the Likert Scale) by less than 75% of the participants, and highly important when rated 4 or 5 on the Likert Scale by minimally 75% of the participants. Further, the topic was categorized according to the median if not categorized by the former steps (1 or 2: unimportant; 3: important; 4 or 5: highly important) (Diamond et al., Citation2014; Trevelyan and Robinson, Citation2015; Von der Gracht, Citation2012). Second, consensus was assumed when IQR ≤ 0.75. Consequently, topics were taken out of the procedure when consensus was assumed or when topics were rated as unimportant, leaving the (highly) important topics without consensus for reevaluation (). After Round 4, all topics were categorized according to their importance and degree of consensus. Finally, all topics deemed “highly important” by all Panels (i.e., Delphi and Validation Panels) were presented as consented topics. The judgments of all topics in their respective categories, including the Validation panels’ judgments, is presented separately in Table S2.

Figure 2. Flowchart of topic analysis after Delphi and Validation Panels judgments. Topics judged as “not important” were taken out of the procedure, as were the topics judged as “highly important” or “important,” with a high degree of consensus. Validation Panels judged the “highly important,” “important,” and “ambivalent” topics based on Round 2. Finally, all topics judged as “highly important” by both the Delphi and all Validation panels were presented as a consented list. IASP: International Association for the Study of Pain, EFIC: European Pain Federation.

Comments of Delphi and Validation panels

The first two authors made a selection of the comments that were mentioned more than once by Delphi Panel members supporting the quantitative data and providing context for a better understanding of the results. These comments were forwarded to the next round as quotes preserving the original word usage as much as possible, without revealing the commenter’s identity due to writing style. The comments are presented in the Appendix.

Results

Participants in the Delphi Panel

A total of 22 lecturers participated in the Delphi Panel. Twelve out of 13 UAS in the Netherlands were represented. Ten UAS were represented by two lecturers in the Delphi Panel and two UAS by one lecturer. In the last round, there was one dropout (not responding). Descriptive characteristics of the participants are presented in .

Table 2. Sociodemographics of the Delphi Panel.

Participants in the Validation Panels

In Panel (1): the early career physical therapists, a total of 51 out of 91 (55%) completed their single round and were eligible based on their time to completion and completeness, and in Panel (2): physical therapists, 122/237 (51%) were eligible. For Panel (3): the non-pain lecturers, this was 81/100 (81%); Panel (4): the postgraduate pain educators, this was 17/19 (89%); and Panel (5): the EFIC/IASP representatives, this was 10/10 (100%). Descriptive characteristics of the Validation Panels are shown in Table S1.

First round

After an open consultation round, literature review, and duplicate removal, 257 topics were included in the initial list (Table S2). All topics were combined into nine categories: (1) taxonomy and defining pain (13 topics); (2) pain assessment and measurement (20 topics); (3) models and theories (i.e., health and psychosocial models, pain neurophysiology, and anatomy and biology models; 77 topics); (4) multidimensional nature of pain (47 topics); (5) management of pain (45 topics); (6) communication (15 topics); (7) beliefs and attitudes of patient and HCP including students (5 topics); (8) health policy and guidelines in pain (10 topics); and (9) pain subgroups/special populations (25 topics).

Second round

Of the total 257 topics rated in the Second Round, 36 were considered with a high degree of consensus as “highly important,” 16 as “important,” and 59 as “not important.” Additionally, 17 were categorized as ambivalent, resulting in 146 topics for the next round. See for the overview of judgment per round.

Third and fourth round

In Round 3, 146 topics were rated of which 90 remained to be rated in Round 4. After Round 3, only one topic (i.e., “mechanism-based approach”) was categorized as “ambivalent.” The comments revealed that not all panelists were familiar with this topic; consequently, additional information was given in the Fourth Round. After Round 4, the Delphi Panel rated 64 topics as “highly important and with a high degree of consensus,” 25 as “highly important with a low degree of consensus,” 53 as “important with a high degree of consensus,” 44 as “important with a low degree of consensus,” and 71 as being “not important.” A complete list of topics and judgments by the Delphi Panel and Validation Panels is reported in Table S2.

Single round of the Validation Panels

All topics rated as highly important, important, and ambivalent in the Second Delphi Round were presented to all Validation Panels. Out of these 198 topics, a total of 70 topics were rated as “highly important” by all Validation Panels and were used as a filter after the final Fourth Delphi Round. Summarized ratings of each Validation Panel are presented in .

Table 3. Summarized ratings of the 198 items by the Validation Panels.

Comments from the Delphi and Validation Panels addressed the complexity, relevance, and specificity of the judged topics. Representative comments are presented in Appendix.

Final results

After four rounds, the Delphi Panel reached a consensus on a total of 89 topics as “highly important.” After cross checking this list with the 70 topics rated as “highly important” by the Validation Panels, it was determined that collective consensus was reached on 63 topics (). A complete overview of all ratings of both the Delphi Panel and all Validation Panels is presented in Table S2.

Table 4. Categories and topics with a collective consensus between Delphi panel and validation panels.

Discussion

This study resulted in a list, by consensus, of 63 pain-related essential topics that preregistration undergraduate physical therapy students should learn in order to adequately treat patients with pain. Eight out of nine (at the start of this investigation addressed) categories are represented in the final list, showing the agreed broadness of pain education. Going more into detail, the results show that the topics should be seen from the perspective of hierarchy. Some topics resemble a broader area and can be considered a parent topic (e.g., “neurophysiology of modulation”), while others relate more in-depth to this topic as a child topic (e.g., “endogenous pain inhibition: conditioned pain modulation”). It is advised that this hierarchy is taken into account when developing a pain curriculum.

This study proposed a broad spectrum of biopsychosocial topics that could influence the patients’ experience and expression of pain related to current pain science. The agreed topics mainly represent understanding, assessing, and managing the complex multidimensional nature of pain. There is also consensus about a patient-centered approach to pain management, active interventions, and behavioral principles. In addition, Validation Panel (5) IASP/EFIC representatives commented to add the use of TENS and heat and cold as part of self-management strategy or manual therapy as a therapeutic strategy.

Topics such as “the biopsychosocial model,” “self-management,” and “patient-centered approach” are strategies that can be offered generically for several health problems, not only in pain rehabilitation. These general concepts create opportunities in the curriculum to develop competencies in general and more in-depth in specific areas such as pain. As pain is best approached using interdisciplinary collaboration, it has also been argued that students should learn about pain using interprofessional education (Carr and Watt-Watson, Citation2012; Gordon, Watt-Watson, and Hogans, Citation2018; Hoeger Bement et al., Citation2014; Van Lankveld, Afram, Staal, and Van der Sande, Citation2020). Therefore, cross-professional agreed competencies are needed to allow good collaboration. However, this also requires educators to adopt these strategies in their education and become competent in teaching them.

In “Management of pain,” some topics were commented on as “not suitable/too complex” and “knowing the concept but not supportive for practice.” For example, low consensus was reached on the topics “cognitive-behavioral methods” and “multi/interdisciplinary collaboration.” Nonetheless, these strategies may still be relevant for the preregistration undergraduate curriculum at a less advanced level. In fact, multiple studies support having competence in delivering psychologically informed interventions in physical therapy (Ballengee, Zullig, and George, Citation2021; Denneny et al., Citation2020; Main and George, Citation2011). At a preregistration undergraduate level, it is key that the student recognizes these management strategies as an option in chronic pain with a starting level of competence (Denneny et al., Citation2020). Comments of Delphi Panelists supported this: “Several concepts can at least be provided; they do not all have to be discussed with the same depth” and “Inter and multidisciplinary management; it is important to know when you have to work together and what the boundaries are.”

The current study results enable building curriculum outlines for education in pain, which shows considerable overlap with curriculum content described in earlier studies (Briggs, Carr, and Whittaker, Citation2011; Doorenbos et al., Citation2013; Hoeger Bement et al., Citation2014; Shipton et al., Citation2018) and by the IASP, EFIC, and the British Pain Society (British Pain Society, Citation2018; European Pain Federation, Citation2017; International Association for the Study of Pain, Citation2018). However, this study had a different focus: identifying content for education in pain for uniprofessional physical therapy education at a preregistration undergraduate level. The IASP provides a Curriculum Outline on Pain for Physical Therapy on competences and learning objectives. This study supplements this outline by providing guidance on the advised content required for treating patients with pain adequately.

Strengths

The composition of the Delphi Panel was representative of the target population of lecturers in pain in higher education. Additionally, a near-complete representation of all UAS in the Netherlands was achieved. Further, the liberal reporting of topics added topics from the IASP and EFIC literature and the verification of completeness by a Validation Panel, resulted in a complete and content valid list of topics. Furthermore, a complete response was obtained in the first three rounds, and only one was missing in Round 4 resulting in a consistent share of each Delphi Panel member’s judgment in all rounds.

Importantly, since the outcome of the Delphi study relies heavily on the quality of the judgment of the panelists, multiple methodological steps were taken for bias reduction. First, the multitude of topics could lead to rating topics less known to the rater as less important (i.e., recognition heuristic) (Erdfelder, Küpper-Tetzel, and Mattern, Citation2011). To address this, an option of “unknown topic” was added. Second, a social-desirability responder bias was mitigated by the anonymity of responses: raters were able to hide unfamiliarity with a topic (Edwards, Citation1953). Based upon the frequent usage of the “unknown topic” option in all panels, we postulate that this form of bias is not dominantly present. Additionally, in every subsequent round, an explanation of unknown topics based upon the ratings and comments or misunderstood topics based upon comments was given to increase the familiarity with the topic and thus the validity of each panel member's rating. Third, to avoid contrast effects, where two topics are judged compared to one another and therefore rated increasingly higher, topics were sorted based upon the importance obtained in the former round to reduce the actual contrast between topics (Sumer and Knight, Citation1996). Additionally, all topics were clustered into categories and presented as one cluster per page to avoid comparison with more extremely rated topics of other categories. Fourth, our results show many topics rated as important by most raters. An overestimation of importance could be addressed to the acquiescence bias (Lavrakas, Citation2008). To counter this, the positive importance of ratings was divided into three scales, which was also used to prevent ceiling effects. Fifth, national bias, which could limit the generalizability to a national level, was reduced by including the ratings of the Validation Panel consisting of EFIC and IASP representatives. Sixth, using different clusters of experts of non-equal level of expertise may enhance the validity and comprehensiveness of the consensus (Sorooshian, Citation2018). Seventh, group bias and a possible bandwagon effect were minimized using Validation Panels. The panels were either potentially more or less biased toward the higher importance of pain topics; the postgraduate educators versus the non-pain lecturers in the field of higher education in physical therapy. Finally, different levels of experience and applicability were taken into account by including advanced students, recent graduates, and physical therapists. The results of all panels showed usage of the unknown option, reduced ceiling effects, and panel differences (e.g., EFIC and IASP representatives rated more topics as highly important). In summary, by applying these strategies the risk of (serious) bias in this study is reduced and thereby contributing to the robustness of the results.

Limitations

Although many methodological steps have been taken to strengthen this study, there are still limitations to address. Even though all raters were asked to rate the importance of the pain topic free of competence level, some comments revealed that an ambiguous response was possible while using the same reasoning. Topics were rated as important, but only on a “recognition” level (i.e., Competence Level 1), while the panel used the same reasoning to rate the topic as non-important. Additionally, comments revealed that topics rated as non-important in this study can still be (highly) important on a higher level of competence (e.g., postgraduate courses). In contrast, different reasoning methods were shown to support an equal rating of importance: reasons based on complexity, clinical relevance, practical implications, applicability, and the evidence base of a strategy. To address these limitations within reasoning, a degree of consensus was added when analyzing the topics. A larger dispersion resulted in a rerating in the next round, and panelists were asked to comment on a specific topic. Finally, the global generalizability of the study results is enhanced by using an international Validation Panel. Still, direct use of these results could be limited by differences in educational systems per country and hence varying levels of educational standards (i.e., preregistration undergraduate, graduate, and postgraduate levels). Consequently, implementation of results needs to be done carefully.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the list of 63 topics could serve as a starting point for (further) development of a comprehensive preregistration undergraduate physical therapy pain curricula and should be taught as part of the development toward the graduate level as IASP and EFIC curriculum outlines. As national biases were reduced, the results could be generalized to other countries while considering the local curricula structure.

Educators can use this study as a benchmark for their own curriculum. If deficits exist, new content can be supplemented to their curriculum. Additional investigation of areas of disagreement will enable educators to consider the scope and depth of content on ideas that should be covered. Further, the level of competence should be taken into account in curriculum development. In developing these curricula, the following questions should be considered: (1) Dosage: What amount of time should the pain curriculum take; (2) Timing: Where in the curriculum should pain-related content be incorporated; (3) Delivery: What educational formats should be used; (4) Assessment: How should instructors assess the efficacy of the curriculum; and (5) Teacher competency: How can educators achieve competence in teaching in a pain curriculum?

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (642.7 KB)Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the Delphi Panel representing the Universities of Applied Sciences in the Netherlands: Hogeschool van Amsterdam; Hogeschool Arnhem Nijmegen; Hanze Hogeschool Groningen; Hogeschool Zuyd Heerlen; Hogeschool Leiden; Hogeschool Rotterdam; Hogeschool Saxion Enschede; Hogeschool Utrecht; Thim Hogeschool of Physical Therapy; Fontys Hogeschool Eindhoven; Avans Hogeschool Breda; and SOMT University of Physical Therapy Amersfoort. We thank all the participants of the Validation Panels: early career physical therapists; physical therapists; non-pain lecturers; postgraduate pain educators; EFIC; and IASP representatives. Finally, we thank A. Engers, S. Mooren-van der Meer, E. de Raaij, and H. Wittink for their help during the inception of the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2022.2144562

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ballengee LA, Zullig LL, George SZ 2021 Implementation of psychologically informed physical therapy for low back pain: Where do we stand, where do we go? Journal of Pain Research 14: 3747–3757. 10.2147/JPR.S311973.

- Becker GE, Roberts T 2009 Do we agree? Using a Delphi technique to develop consensus on skills of hand expression. Journal of Human Lactation 25: 220–225. 10.1177/0890334409333679.

- Bergsmann E, Schultes MT, Winter P, Schober B, Spiel C 2015 Evaluation of competence-based teaching in higher education: From theory to practice. Evaluation and Program Planning 52: 1–9. 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2015.03.001.

- Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P 2012 What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total Hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of Prospective studies in unselected patients. British Medical Journal Open 2: e000435.

- Briggs EV, Battelli D, Gordon D, Kopf A, Ribeiro S, Puig MM, Kress HG 2015 Current pain education within undergraduate medical studies across Europe: Advancing the Provision of Pain Education and Learning (APPEAL) study. British Medical Journal Open 5: e006984.

- Briggs EV, Carr EC, Whittaker MS 2011 Survey of undergraduate pain curricula for healthcare professionals in the United Kingdom. European Journal of Pain 15: 789–795. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2011.01.006.

- British Pain Society 2018 Pre-Registration pain education. https://www.britishpainsociety.org/pain-education-special-interest-group/pain-education-sig-resources/

- Carr E, Watt-Watson J 2012 Interprofessional pain education: Definitions, exemplars and future directions. British Journal of Pain 6: 59–65. 10.1177/2049463712448174.

- Cowell I, O’Sullivan P, O’Sullivan K, Poyton R, McGregor A, Murtagh G 2018 Perceptions of physiotherapists towards the management of non-specific chronic low back pain from a biopsychosocial perspective: A qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 38: 113–119. 10.1016/j.msksp.2018.10.006.

- Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, Hart J, Kimber A, Storey L, Thomas H 2002 The measurement of satisfaction with health care: Implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technology Assessment 6: 1–244. 10.3310/hta6320.

- Denneny D, Nee Klapper A, Bianchi-Berthouze N, Greenwood J, McLoughlin R, Petersen K, Singh A, Williams A 2020 The application of psychologically informed practice: Observations of experienced physiotherapists working with people with chronic pain. Physiotherapy 106: 163–173. 10.1016/j.physio.2019.01.014.

- Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM, Pencharz PB, Ling SC, Moore AM, Wales PW 2014 Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 67: 401–409. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002.

- Doorenbos AZ, Gordon DB, Tauben D, Palisoc J, Drangsholt M, Lindhorst T, Danielson J, Spector J, Ballweg R, Vorvick L, et al. 2013 A blueprint of pain curriculum across prelicensure health sciences programs: One NIH pain consortium center of excellence in pain education (CoEPE) experience. Journal of Pain 14: 1533–1538. 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.07.006.

- Edgerton K, Hall J, Bland MK, Marshall B, Hulla R, Gatchel RJ 2019 A physical therapist’s role in pain management: A biopsychosocial perspective. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research 24: 1–17. 10.1111/jabr.12170.

- Edwards AL 1953 The relationship between the judged desirability of a trait and the probability that the trait will be endorsed. Journal of Applied Psychology 37: 90–93. 10.1037/h0058073.

- Ehrström J, Kettunen J, Salo P 2018 Physiotherapy pain curricula in Finland: A faculty survey. Scandinavian Journal of Pain 18: 593–601. 10.1515/sjpain-2018-0091.

- Erdfelder E, Küpper-Tetzel CE, Mattern SD 2011 Threshold models of recognition and the recognition heuristic. Judgment and Decision Making 6: 7–22.

- European Pain Federation 2017 Curriculum for the European diploma in pain physiotherapy. https://europeanpainfederation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/EFIC-Pain-Physiotherapy-Curriculum1.pdf

- European Pain Federation 2019 Core curriculum for the European diploma in pain nursing. https://europeanpainfederation.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/EFIC-CORE-NURSING-WEB-FINAL-Published-on-website.pdf

- Fishman SM, Young HM, Lucas Arwood E, Chou R, Herr K, Murinson BB, Watt-Watson J, Carr DB, Gordon DB, Stevens BJ, et al. 2013 Core competencies for pain management: Results of an interprofessional consensus summit. Pain Medicine 14: 971–981. 10.1111/pme.12107.

- Gallagher R, Vaillancourt PD, Balter K, Cohen M, Garvin B, Charibo C, King SA, Workman EA, McClain B 2000 Undergraduate medical education in pain medicine, end-of-life care, and palliative care. Pain Medicine 1: 224.

- Giordano J, Boswell MV 2011 Maldynia: Chronic pain, complexity, and complementarity. In: Giordano J (Ed) Maldynia: multidisciplinary perspectives on the illness of chronic pain 201–212. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

- Goldammer P, Annen H, Stöckli PL, Jonas K 2020 Careless responding in questionnaire measures: Detection, impact, and remedies. Leadership Quarterly 31: 101384. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2020.101384.

- Goldberg DS, McGee SJ 2011 Pain as a global public health priority. BioMed Central Public Health 11: 770. 10.1186/1471-2458-11-770.

- Gordon DB, Watt-Watson J, Hogans BB 2018 Interprofessional pain education - With, from, and about competent, collaborative practice teams to transform pain care. Pain Reports 3: e663. 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000663.

- Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H 2000 Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing 32: 1008–1015.

- Hoeger Bement MK, Sluka KA 2015 The current state of physical therapy pain curricula in the United States: A faculty survey. Journal of Pain 16: 144–152. 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.11.001.

- Hoeger Bement MK, St. Marie BJ, Nordstrom TM, Christensen N, Mongoven JM, Koebner IJ, Fishman SM, Sluka KA 2014 An interprofessional consensus of core competencies for prelicensure education in pain management: Curriculum application for physical therapy. Physical Therapy 94: 451–465. 10.2522/ptj.20130346.

- Huang JL, Curran PG, Keeney J, Poposki EM, DeShon RP 2012 Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. Journal of Business and Psychology 27: 99–114. 10.1007/s10869-011-9231-8.

- Hunter J, Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, Raman-Wilms L, Cockburn L, Lax L, Stinson J, Cameron A, Dao T, Pennefather P, et al. 2008 An interfaculty pain curriculum: Lessons learned from six years experience. Pain 140: 74–86. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.07.010.

- Hush JM, Nicholas M, Dean CM 2018 Embedding the IASP pain curriculum into a 3-year pre-licensure physical therapy program: Redesigning pain education for future clinicians. Pain Reports 3: e645. 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000645.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2019 GBD Compare -Viz Hub. Washington, DC: University of Washington. http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare .

- Institute of Medicine 2011 Relieving pain in America: A blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).

- International Association for the Study of Pain 2010 International association for the study of pain. Declaration of Montreal https://www.iasp-pain.org/advocacy/iasp-statements/access-to-pain-management-declaration-of-montreal/

- International Association for the Study of Pain 2011 Desirable characteristics of national pain strategies. recommendations by the international association for the study of pain. https://www.iasp-pain.org/advocacy/iasp-statements/desirable-characteristics-of-national-pain-strategies/

- International Association for the Study of Pain 2018 IASP curriculum outline on pain for physical therapy. https://www.iasp-pain.org/education/curricula/iasp-curriculum-outline-on-pain-for-physical-therapy/

- Jackson T, Thomas S, Stabile V, Han X, Shotwell M, McQueen K 2015 Prevalence of chronic pain in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 385 Suppl 2: S10. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60805-4.

- Jones L 2009 Implications of IASP core curriculum for pre-registration physiotherapy education. Reviews in Pain 3: 11–15. 10.1177/204946370900300104.

- Jorm AF 2015 Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 49: 887–897. 10.1177/0004867415600891.

- Keeney S, Hasson F, McKenna H 2010 The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Hoboken: NJ Wiley-Blackwell.

- Keeney S, McKenna H 2005 Consulting the oracle: Ten lessons from using the Delphi technique in nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 53: 205–212. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03716.x.

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ 2006 Persistent postsurgical pain: Risk factors and prevention. Lancet 367: 1618–1625. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X.

- Lavrakas PJ 2008 Acquiescence response bias. Encyclopedia of survey research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Leegaard M, Valeberg B, Haugstad GK, Utne I 2014 Survey of pain curricula for healthcare professionals in Norway. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research 34: 42. 10.1177/010740831403400110.

- Loeser JD 2015 The education of pain physicians. Pain Medicine 16: 225–229. 10.1111/pme.12335.

- Lozano LM, García-Cueto E, Muñiz J 2008 Effect of the number of response categories on the reliability and validity of rating scales. Methodology European Journal of Research Methods for the Behavioral and Social Sciences 4: 73–79. 10.1027/1614-2241.4.2.73.

- Main CJ, George SZ 2011 Psychologically informed practice for management of low back pain: Future directions in practice and research. Physical Therapy 91: 820–824. 10.2522/ptj.20110060.

- Mezei L, Murinson BB 2011 Pain education in North American medical schools. Journal of Pain 12: 1199–1208. 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.06.006.

- Miles S, Kellett J, Leinster SJ 2017 Medical graduates’ preparedness to practice: A comparison of undergraduate medical school training. BioMed Central Medical Education 17: 33. 10.1186/s12909-017-0859-6.

- Moret L, Nguyen JM, Pillet N, Falissard B, Lombrail P, Gasquet I 2007 Improvement of psychometric properties of a scale measuring inpatient satisfaction with care: A better response rate and a reduction of the ceiling effect. BioMed Central Health Services Research 7: 197. 10.1186/1472-6963-7-197.

- Murinson BB, Mezei L, Nenortas E 2011 Integrating cognitive and affective dimensions of pain experience into health professions education. Pain Research and Management 16: 421–426. 10.1155/2011/424978.

- Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, Marteau T 1998 Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technology Assessment 2: i–iv, 1–88. 10.3310/hta2030.

- O’Brien BC, Harris IB, Beckman TJ, Reed DA, Cook DA 2014 Standards for reporting qualitative research: A synthesis of recommendations. Academic Medicine 89: 1245–1251. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388.

- Okoli C, Pawlowski SD 2004 The Delphi method as a research tool: An example, design considerations and applications. Information and Management 41: 14–20.

- Pendergast J, Kliethermes SA, Freburger JK, Duffy PA 2012 A comparison of health care use for physician-referred and self-referred episodes of outpatient physical therapy. Health Services Research 47: 633–654. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01324.x.

- Pöyhiä R, Niemi-Murola L, Kalso E 2005 The outcome of pain related undergraduate teaching in Finnish medical faculties. Pain 115: 234–237. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.033.

- Rice AS, Smith BH, Blyth FM 2016 Blyth FM 2016 Pain and the global burden of disease. Pain 157: 791–796. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000454.

- Scudds RJ, Scudds RA, Simmonds M 2001 Pain in the physical therapy (PT) curriculum: A faculty survey. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 17: 239–256. 10.1080/095939801753385744.

- Sessle BJ 2012 The pain crisis: What it is and what can be done. Pain Research and Treatment 2012: 703947. 10.1155/2012/703947.

- Shipton EE, Bate F, Garrick R, Steketee C, Shipton EA, Visser EJ 2018 Systematic review of pain medicine content, teaching, and assessment in medical school curricula internationally. Pain and Therapy 7: 139–161. 10.1007/s40122-018-0103-z.

- Singla M, Jones M, Edwards I, Kumar S 2015 Physiotherapists’ assessment of patients’ psycho-social status: Are we standing on thin ice? A qualitative descriptive study. Manual Therapy 20: 328–334. 10.1016/j.math.2014.10.004.

- Skulmoski J, Hartman TF, Krahn J 2007 The Delphi method for graduate research. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research 6: 1–21. 10.28945/199.

- Sorooshian S 2018 Group decision making with unbalanced-expertise. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, Makassar, Indonesia. 1028: 012003.

- Sumer HC, Knight PA 1996 Assimilation and contrast effects in performance ratings: Effects of rating the previous performance on rating subsequent performance. Journal of Applied Psychology 81: 436–442. 10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.436.

- Sumsion T 1998 The Delphi technique: An adaptive research tool. British Journal of Occupational Therapy 61: 153–156. 10.1177/030802269806100403.

- Synnott A, O’Keeffe M, Bunzli S, Dankaerts W, O’Sullivan P, O’Sullivan K 2015 Physio-therapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery: A systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy 61: 68–76. 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.02.016.

- Thompson M 2009 Considering the implication of variations within Delphi research. Family Practice 26: 420–424. 10.1093/fampra/cmp051.

- Thompson K, Johnson MI, Milligan J, Briggs M 2018 Twenty-five years of pain education research-what have we learned? Findings from a comprehensive scoping review of research into pre-registration pain education for health professionals. Pain 159: 2146–2158. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001352.

- Trevelyan EG, Robinson N 2015 Delphi methodology in health research: How to do it? European Journal of Integrative Medicine 7: 423–428. 10.1016/j.eujim.2015.07.002.

- Van Gorp S, Kessels AG, Joosten EA, Van Kleef M, Patijn J 2015 Pain prevalence and its determinants after spinal cord injury: A systematic review. European Journal of Pain 19: 5–14. 10.1002/ejp.522.

- Van Lankveld W, Afram B, Staal JB, Van der Sande R 2020 The IASP pain curriculum for undergraduate allied health professionals: Educators defining competence level using Dublin descriptors. BioMed Central Medical Education 20: 60. 10.1186/s12909-020-1978-z.

- Verwoerd MJ, Wittink H, Goossens ME, Maissan F, Smeets RJ 2022 Physiotherapists’ knowledge, attitude and practice behavior to prevent chronification in patients with non-specific, non-traumatic, acute- and subacute neck pain: A qualitative study. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice 57: 102493. 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102493.

- Von der Gracht HA 2012 Consensus measurement in Delphi studies. Review and implications for future quality assurance. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 79: 1525–1536. 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.04.013.

- Watt-Watson J, Hunter J, Pennefather P, Librach L, Raman-Wilms L, Schreiber M, Lax L, Stinson J, Dao T, Gordon A, et al. An integrated undergraduate pain curriculum, based on IASP curricula. for Six Health Science Faculties. Pain. 2004;110: 140–148.

- Watt-Watson J, McGillion M, Hunter J, Choiniere M, Clark AJ, Dewar A, Johnston C, Lynch M, Morley-Forster P, Moulin D, et al. 2009 A survey of pre-licensure pain curricula in health science faculties in Canadian universities. Pain Research and Management 14: 439–444. 10.1155/2009/307932.

- Wilson A, Averis A, Walsh K 2003 The influences on and experiences of becoming nurse entrepreneurs: A Delphi study. International Journal of Nursing Practice 9: 236–245. 10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00426.x.

- Wylde V, Sayers A, Lenguerrand E, Gooberman-Hill R, Pyke M, Beswick AD, Dieppe P, Blom AW 2015 Preoperative widespread pain sensitization and chronic pain after Hip and knee replacement: A cohort analysis. Pain 156: 47–54. 10.1016/j.pain.0000000000000002.