ABSTRACT

Background

The novel Motor Imagery to Facilitate Sensorimotor Re-Learning (MOTIFS) training model, which began development in 2018, integrates psychological training into physical rehabilitation in knee-injured people.

Objective

This qualitative interview study aims to understand, interpret, and describe how physical therapists perceive using the MOTIFS Model.

Methods

One-on-one semi-structured interviews were conducted with six physical therapists familiar with the MOTIFS model and eight with experience with care-as-usual training only, analyzed using Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis.

Results

Two major themes were generated in the MOTIFS group: 1) “MOTIFS increases psychological focus during rehabilitation training”; and 2) “Care-as-Usual training is mainly physical, and lacks the necessary psychological focus.” Physical therapists perceived structured methods of addressing psychological factors, such as using imagery to influence patients’ motivation, fear, and preparation for return to activity. Three major themes were generated in the Care-as-Usual group: 1) “Rehabilitation is mainly to restore physical function”; 2) “Rehabilitation training includes a biopsychosocial interaction”; and 3) “Psychological factors are important to address, but strategies are lacking.”

Conclusion

Physical therapists perceive MOTIFS as a method of consciously shifting perspective toward an increased focus on psychological factors in knee-injury rehabilitation. Results indicate that a training model with integrated psychological strategies to create more holistic rehabilitation may be beneficial.

Introduction

Traumatic knee injuries, such as those of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), are common in sport and recreational activities. Care-as-usual (CaU) treatment includes physical rehabilitation incorporating neuromuscular and strength training to restore function to injured and surrounding structures of the knee (Andrade et al., Citation2019). Current best-practice recommendations, such as those proposed by Filbay and Grindem (Citation2019) and van Melick et al. (Citation2016) are often followed in rehabilitation. Despite this, approximately half of physically active people that suffer an ACL injury have persisting functional impairments (Ageberg et al., Citation2008; Thomeé et al., Citation2012) and only 65% return to the same level of sport after having undergone rehabilitation (Ardern, Taylor, Feller, and Webster, Citation2014).

Psychological aspects of injury such as motivation, optimism, self-confidence, and lower fear of re-injury have been shown to be predictors of return to activity following knee injury (Ardern, Taylor, Feller, and Webster, Citation2012; Czuppon, Racette, Klein, and Harris-Hayes, Citation2014; Everhart, Best, and Flanigan, Citation2013). They have been shown to be associated with physical dysfunctions such as altered knee flexion (Zarzycki, Failla, Capin, and Snyder-Mackler, Citation2018), hop ability (Thomeé et al., Citation2008), and self-reported knee function (Hart, Culvenor, Guermazi, and Crossley, Citation2020) leading to recommendations to incorporate psychological aspects into CaU (Filbay and Grindem, Citation2019). They have not, however, been systematically and organically incorporated into rehabilitation programs. Previous literature has called for interventional studies to influence psychological factors (Ardern et al., Citation2016; Piussi et al., Citation2021; Podlog, Dimmock, and Miller, Citation2011) indicating that a more holistic view of rehabilitation might be necessary to determine how to best prepare patients in terms of physical and psychological readiness to return to activity.

The novel Motor Imagery to Facilitate Sensorimotor Relearning (MOTIFS) training (Cederström, Granér, Nilsson, and Ageberg, Citation2021a; Cederström et al., Citation2021b) attempts to bridge this gap by integrating psychological training into CaU exercises to create a more holistic intervention for rehabilitation using ACL or other traumatic knee injuries which require long-term rehabilitation (i.e. longer than 3 months) as a model. MOTIFS training integrates Dynamic Motor Imagery (DMI) into physical rehabilitation protocols, in which patients psychologically simulate individualized and activity-specific situations while simultaneously executing physical aspects of that situation (Guillot and Collet, Citation2008). DMI has shown positive effects on motivation and affect in uninjured people (Simonsmeier, Andronie, Buecker, and Frank, Citation2021) and for reducing fear and increasing confidence in knee-injured athletes (Rodriguez, Marroquin, and Cosby, Citation2019). In MOTIFS training, the physical therapist and patient discuss the movement in order to design an exercise integrating physical and psychological aspects of a sport situation, which is then executed and evaluated for realism and relevance (Cederström et al., Citation2021b). MOTIFS training has been shown to increase enjoyment and effort while performing a rehabilitation movement and simultaneously simulating a relevant scenario such as kicking a soccer ball when compared to CaU (Cederström, Granér, Nilsson, and Ageberg, Citation2021a). Therefore, a rehabilitation movement can be modified to include psychological and physical task and environment-specific aspects to create a more holistic and individualized rehabilitation program. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is ongoing which hypothesizes that 12 weeks of physical therapist-administered MOTIFS training will result in greater psychological readiness to return to sport and better muscle function than CaU during late phases of rehabilitation in people undergoing treatment for traumatic knee injury.

Few qualitative studies have examined experiences of physical therapists and how they perceive meaning in their strategies to reach rehabilitation goals (McPherson and Kayes, Citation2012; Von Aesch, Perry, and Sole, Citation2016). Such interview data may aid in identifying how rehabilitation is performed with regard to both physical and psychological interventions. This may aid in generating new hypotheses, and provide information on how to improve rehabilitation to ensure both physical and psychological readiness to return to activity. The aim of this study is to understand, interpret, and describe how practicing physical therapists perceive using MOTIFS training in rehabilitation of traumatic knee injuries. In order to fully understand the context in which physical therapists using MOTIFS training perceive their lived experiences, one must gain an understanding also of the base phenomenon (i.e. CaU training) without the influence of the new intervention. Therefore, lived experiences of physical therapists using CaU training must also be explored.

Methods

This interpretive phenomenological interview study is part of the MOTIFS RCT (clinicaltrials.gov registration number NCT03473821; Lund University ethical approval number Dnr 2016/413, Dnr 2018/927) (Cederström et al., Citation2021b). Neither funders nor the study sponsor participated in design or execution of this study. Physical therapists in the MOTIFS and CaU groups were purposively recruited by telephone from the ongoing MOTIFS RCT in southern Sweden. Participants were recruited and interviewed by the study coordinator for both this interview study and the RCT. The study coordinator is the first author (NC), a male doctoral student at time of data collection with expertise in sport psychology and trained in interview techniques, has American English as a native language, is fluent in Swedish, and has regular telephone contact with the physical therapists active in the RCT eligible for the current study. Participant eligibility criteria included at least 2 years’ experience treating musculoskeletal disorders and treating knee-injured patients on a weekly basis; the MOTIFS group was also required to have undergone MOTIFS training and report applied experience with patients (Cederström et al., Citation2021b). Interviews were conducted with 6 MOTIFS physical therapists and 10 CaU physical therapists; data saturation was reached following interviews with 6 MOTIFS and 8 CaU physical therapists () with saturation defined as the point at which the conceptual model was not changed by two new interviews (Moser and Korstjens, Citation2018; Saunders et al., Citation2018) confirmed by screening remaining interviews.

Table 1. Demographics of interviewed physical therapists from the care-as-usual and MOTIFS conditions.

Written and verbal information was provided, and demographic information and informed consent were collected by the interviewer both prior to and repeated during the interview. One-on-one interviews were conducted between August 2019 and December 2020 (n = 1 MOTIFS face-to-face; n = 5 MOTIFS, n = 10 CaU digitally [due to COVID 19 pandemic restrictions]) with no non-participants present and no repeat interviews (). Both audio and video were recorded in order to aid in transcription and interpretation of positive and/or negative body language and other non-verbal communication. Interviews began with verbal information regarding the aims of the study and collecting verbal informed consent. During this process, participants were able to ask questions, and a conversational tone was taken to establish rapport between interviewer and interviewee. The interview then began by asking questions which had been tested with n = 2 non-participant practicing physical therapists to ensure relevance and depth of response (i.e. open vs closed questioning). The pilot participants had experience using the MOTIFS model but were not active in the RCT and were therefore ineligible for this interview study. The interview guide was deemed acceptable, and no changes were made following pilot testing. Open-ended, pilot-tested questions were asked in order to provide in-depth answers. The MOTIFS group was asked to “explain, in as much detail as possible, how you experience using MOTIFS training.” The CaU group was asked to “explain, in as much detail as possible, how you experience rehabilitation following traumatic knee injury.” Based on notes taken during interviews, follow-up questions in both groups included questions such as “can you explain what you mean by …” or “can you elaborate on …” to encourage thorough responses. All interview and personal data including audio and video records were stored on a secure server. Participation was voluntary during free time, with the ability to end participation at any time, and consent was provided to publish anonymized quotations. The interviewer does not have a position of power over the interviewees, so power imbalances are not seen as causing ethical issues. The content of the interview does not pertain to sensitive topics which might risk emotional or psychological issues in which special ethical consideration would be warranted.

Figure 1. Participant flow diagram. *Approached physical therapists pre-screened for eligibility § n=2 interviews not included in analysis due to reaching data saturation MOTIFS = MOT or Imagery to Facilitate Sensorimotor re-learning.

Data analysis was performed using QSR International’s NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software. Interview responses were analyzed according to coding reliability thematic analysis, grounded in an interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA) approach. IPA aims to identify unique aspects of a phenomenon, decode individuals’ experiences, and interpret individual context (Pietkiewicz and Smith, Citation2014). Thematic analysis aims broadly to identify and make sense of meaning, with ‘coding reliability’ indicating that an approach attempts to more objectively identify meaning-bearing themes (Braun and Clarke, Citation2021). This combined approach allows for presentation of what ‘rehabilitation’ is (i.e. objective presentation of themes confirmed by several coders) along with phenomenological interpretation to provide context based on physical therapist experiences (i.e. not only what they do but how they make sense of this reality). Similar combined approaches have been described previously which aim to interpret lived experiences while also providing a degree of quality control (Sundler, Lindberg, Nilsson, and Palmér, Citation2019). Reliability is secondary to describing the lived experiences but is used to ensure inter-coder agreement. A further explanation of the methodological rationale for using coding reliability thematic analysis is available in Appendix 1.

The primary coder (NC) transcribed anonymized interviews in Swedish verbatim. The transcription was corrected, anonymized, and meaning units were identified. Major themes were identified as an overarching shared topic, while subordinate themes were coded according to a shared meaning under the umbrella topic (Braun and Clarke, Citation2021). The primary coder inductively generated major themes, and subsequently more detailed subordinate themes (Moser and Korstjens, Citation2018). IPA was used to generate major themes based on keywords (i.e. “psychological” and “physical training”) or clear reference to an overall topic; subordinate themes were interpreted based on the contextual meaning of the quotation within that topic and consensus of the interdisciplinary coders. For example, Participant 14 described that “parameters guide […] load” identified as a discussion of physical training further interpreted as expressing the use of criteria-based progression strategies. This inductive coding strategy was used as the primary analysis to identify physical therapist experiences, and thereby answer the aims of this study.

Preliminary models generated from two interviews were sent to Coder 2 (SG; expertise in psychology) to deductively code an interview using a priori themes according to coding reliability thematic analysis, and discussions were held until relative agreement was reached. NVivo’s Coding Comparison Query tool was used to calculate a kappa value in order to evaluate the conceptual model’s face validity and inter-coder agreement. Agreement of k = 0.61 was determined to be acceptable (McHugh, Citation2012). If not reached, coding was discussed to resolve issues and calibrate the model and/or theme definitions. This process was repeated with Coder 3 (EA; expertise in physical therapy) until all coders were in agreement. The primary coder followed the same inductive process for all collected data, continuously updating the conceptual model. When two new interviews did not alter the model’s first three levels (i.e. major theme, subordinate theme 1, and subordinate theme 2) data saturation was deemed to have been reached, and the final model was compiled. Since all mentions were deemed relevant, themes mentioned by fewer than three participants are specified in the results. If mentioned by three or more participants, it was deemed prevalent enough to indicate a distinct pattern. Quotations were translated and cross-culturally adapted by the first author to ensure accurate meaning. More detail regarding coding procedures is presented in Appendix 1.

Throughout the data collection and coding processes, attempts were made to ensure trustworthiness and rigor. In order to do this, a thorough reading of the material was performed along with reactive phenomenological analysis in which interviews were coded separately and inductively, and by having an interdisciplinary team. As both the interviews and coding are reactive, this also allows for data which can better capture the lived experiences of participants and therefore may constitute a more powerful dataset (Malterud, Siersma, and Guassora, Citation2015). The phenomenological approach allows for the coders to gain a deep understanding of the text material and to interpret meaning as opposed to merely identifying. The interdisciplinary team ensures that the background of an individual coder does not influence the results by introducing personal biases. There is still a risk of bias as individual coder experiences within sport psychology, sports medicine, or experience with the MOTIFS model may still influence coding (Smith and McGannon, Citation2018). However, by utilizing both phenomenological and coding comparison approaches, this risk is seen to be minimal.

Results

Two conceptual models were created, one each for the MOTIFS and CaU groups. Due to the nature of qualitative studies, the models are presented separately, and are not meant to compare generalizable differences, rather to put the MOTIFS model in the context of CaU training. Participant quotations are marked in the text (P#).

MOTIFS group themes

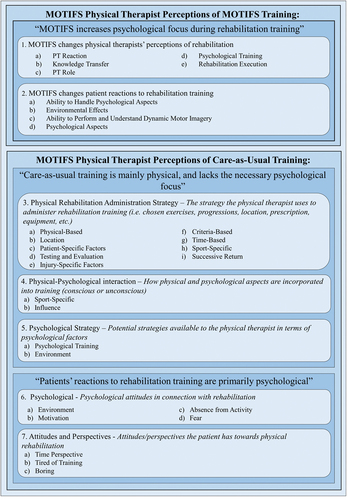

The MOTIFS conceptual model resulted in two major themes ():

Figure 2. Major Theme regarding physical therapists’ perceptions of rehabilitation training, along with more detailed subordinate themes.

1) “MOTIFS increases psychological focus during rehabilitation training”: Physical therapists perceive the MOTIFS model as distinct from CaU training and refer to differences in terms of their own role and patients’ reactions. This includes what physical therapists perceived as important to physical and psychological aspects of rehabilitation from their own and patient perspectives; and

2) “Care-as-Usual training is mainly physical, and lacks the necessary psychological focus”: Physical therapists perceive their role in CaU training as being to restore physical function, with few tools to address psychological aspects. They perceive patients’ reactions to be psychological in nature .

Subordinate themes are presented in text in descending order of density, from most to fewest references; subordinate themes are presented under their respective major themes.

Major theme: “MOTIFS increases psychological focus during rehabilitation training”

“MOTIFS changes physical therapist perceptions of rehabilitation”

Physical therapists perceive a desire to implement MOTIFS training earlier in rehabilitation, as illustrated in MOTIFS Theme 1a (“I would like to start using this stuff in the clinic much earlier. Like right from the start” [P08]) to individualize sport-specific and situational contextual factors. MOTIFS is perceived to do this by involving patients in exercise design through “discussion […] about the problems with – in this case it was a hip – and difficult to get in a lunge position. So we discussed, like, yeah, how would you- what’s your starting position” (P15). This increases focus on context-specific needs, desires, and meaning:

So I ask when in their sport this could happen and they can come up with a situation that, like, they are used to. […] we add that, yeah, think whether there’s an opponent there, or like you said last time you were here, that ‘what are you going to do once you have done the turn and look and see where to pass’ (P08)

They also perceive more consciously using psychological training strategies (MOTIFS Theme 1b) such as imagery to motivate and guide patients (“[there’s a physical development] then it’s I think a motivation for the person doing it. That they understand more.” [P16]). This results in a new perceived role (MOTIFS Theme 1c), with one physical therapist describing providing better psychological support and to “get you more engaged, in order to, like, make sure they get to be the best they can be later” (P15). Physical therapists describe a conscious effort to motivate and connect with the patient’s activity, since “you need a little, I feel, a little sport experience [laughs], be able to know when to push.” (P01). The novelty of MOTIFS is perceived as “maybe not a complement, but an extension to- to exercises that we had before,” (P16) and that

if I’m being totally honest, the exercises are ones we normally do in rehab, but the new thing is that you want them to get in these ideas of thoughts and senses […] is there a smell maybe, to notice things like that. (P03)

Physical therapists describe being helped by receiving education and concrete strategies (MOTIFS Theme 1d). One physical therapist perceives MOTIFS training (MOTIFS Theme 1e) as being “a little unclear” (P15), though confusions are cleared up through meetings and discussion. Others believe it is “a good complement to the care-as-usual training we work with. Especially in the phases where we’re transitioning them back to sport” (P16). Increasing focus on integrating physical and psychological training elicits a positive reaction:

it felt like a very exciting project to get- get the psychological part of, like, sport integrated […] into rehabilitation in a clearer way. It felt like it would contribute something- and I still think that- that it feels like it does. (P14)

“MOTIFS changes patient reactions to rehabilitation training”

Physical therapists believe that imagery integrated into rehabilitation training can increase patient ability to handle psychological aspects of rehabilitation (MOTIFS Theme 2a) through sport-specific exposure:

[Simulating sport-specific situations] is maybe missing in some cases if you don’t train it, so maybe you control your knee super well here, but then you go out on the field and have to think of other things and then lose the knee totally (P08)

Two physical therapists discuss the difference between clinical and sport environments (MOTIFS Theme 2b), and use this to modulate sport-relevant input. Strategies in which “they maybe do their exercises on the side while the others are training” (P01) are used to encourage vivid imagery by integrating MOTIFS into rehabilitation (“[t]hey get the environment around them, it’s with their teammates. […] Because then they are, like, there, they’re in it, they don’t need to imagine it” [P08]).

Divergent patient attitudes to MOTIFS training are perceived (“[a]t the end of this [rehabilitation] period maybe [patients] start to get tired of [MOTIFS training]” [P08]), though several believe that “especially athletes that are craving their sport like the idea” [P14], and “the [patients] that I have had have thought it was pretty fun” (P15). Individual ability and understanding of imagery (MOTIFS Theme 2c) may be influenced by imagery difficulty, as some are “pretty easily receptive to it, and the other has a harder time understanding … the thought process” (P01). A person not active in sport may struggle, as it “doesn’t have the same value in some way, maybe, even if there is a value in it for – to be healthy and able to train and move” (P14). Ability also relates to location, with imagery being “a little difficult sometimes to see it in front of them – here in the clinic” (P08).

Overall, physical therapists perceive MOTIFS as a rehabilitation approach informed by identifying and attending to patients’ individual psychological needs (MOTIFS Theme 1d). This includes adapting communication strategies (“[sport-specific] thoughts – not for everyone, for example not this skier that I talked about – but some can handle thinking about their sport” [P03]) and using imagery to relieve fears by increasing sport-specific movement exposure:

I think you can get rid of fears, because- yeah, you’re already prepared when you get out there … because you’ve already done this somehow, you recognize what you need to do, even though you haven’t done it for real out there, you’ve already done it … here. (P01)

Major theme: “Care-as-usual training is mainly physical and lacks the necessary psychological focus”

Participants in the MOTIFS group also discussed CaU training in order to contextualize and explain the perceived differences. CaU training is relatively standardized, leading to a model very similar to the CaU group. Therefore, in order to prevent repetition, a brief overview will be provided here in order to clarify this context.

“Care-as-usual rehabilitation is based primarily on physical function with few psychological tools”

Physical rehabilitation strategies (MOTIFS Theme 3) depend on time and physical evaluation criteria, type of injury, and the individual, with reduction of symptoms and increasing physical function described as key rehabilitation goals:

first it’s more about reducing swelling, and pain, and increase range of motion, and muscle activation exercises to re-gain normal muscle function (Physical-based). And those parameters guide how much you can load the patient and if there are any restrictions to take into account (Criteria-based and Patient-specific factors). […] And then successively increase the ability to handle the load in those structures and be able to have- execute- execute the exercise with good control (Successive Return). (P14; bold added by authors to indicate theme relevance)

A perceived physical–psychological interaction (MOTIFS Theme 4) includes training sport-specific aspects in which “they’re going back to sport at a pretty good level, so I think that you- you take things from their sport and- and practice those” (P15). This is also done by trying to psychologically influence (MOTIFS Theme 4b) the patient to ensure that the physical training is done well and at an appropriate level (“my role normally is, it’s pretty, I’m pretty motivating as a physical therapist and, and … I provoke quite a bit” [P01]; “It’s that push I use for all athletes, and always have done” [P01]). They expressed that psychological strategies (MOTIFS Theme 5) are needed and may include on-field training (“be a part of the group, in the changing room, and before and after, and to get this sense of belonging and feel … the closeness to the sport” [P01]), or pushing and challenging patients. However, the key perceived difference is the lack of structured strategies in CaU training (“I think I use [psychological training], but I can- I can be better, absolutely” [P16]).

“Patients’ reactions to rehabilitation training are primarily psychological”

Physical therapists perceive that psychological factors influencing rehabilitation (MOTIFS Theme 6) include motivation, the clinical environment, and absence from activity. Patients’ attitudes and perspectives (MOTIFS Theme 7) toward CaU training are that it is boring, but they understand that healing takes time:

[return to sport is] what I’m trying to reach. That’s why I’m doing this rehab (Motivation). That’s why I’m at the physical therapist doing these boring exercises [laughs] (Boring). And I think that’s a really important part in all rehabilitation. (P01; bold added by authors to indicate theme relevance)

Care-as-usual group themes

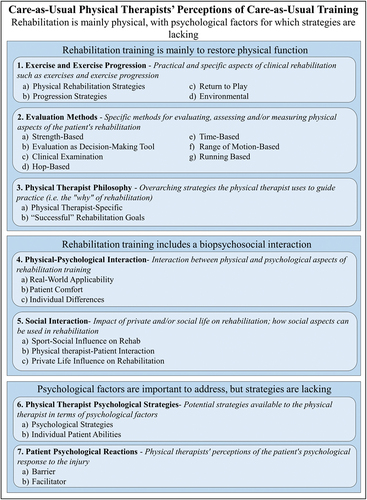

The Care-as-Usual conceptual model includes three Major Themes ():

Figure 3. Major theme regarding care-as-usual physical therapists’ perceptions of rehabilitation training and more detailed subordinate themes.

1) “Rehabilitation is mainly to restore physical function”: Physical therapists explain training philosophy, evaluation, and performance and progression throughout rehabilitation;

2) “Rehabilitation training includes a biopsychosocial interaction”: Physical therapists explain the complex interaction between social, physical, and/or psychological factors on rehabilitation; and

3) “Psychological factors are important to address, but strategies are lacking”: Physical therapists perceive psychological factors, including patient barriers and facilitators to training, and available psychological strategies as important.

Major and subordinate themes are presented from most to fewest references; subordinate themes are presented under their respective major themes.

“Rehabilitation is mainly to restore physical function”

“Exercise and exercise progression”

Physical therapists perceive strength training as important to “protect so you don’t get in a loaded position so that you disrupt the healing of the ligament” (P09), as presented in – CaU Theme 1a. Return to activity training includes individualizing event-specific (i.e. biopsychosocial) “back to sports movements, complex jumps, like hops with rotation, hop with a push and perturbation” (P06). This progression (CaU Theme 1b) follows a “sort of stepwise model” (P06) based on criteria explained in terms of time or “functional movement, […] before we can cycle and before we can go up stairs and stuff, we have to have a certain range of motion” (P07). Patient abilities, perception of difficulty, and symptoms influence development of rehabilitation programs (“when you then start with- with more rushes, that they should be able to change direction quickly, and feel safe on both feet” [P10]). Return to activity progression (CaU Theme 1c) can include modulating location (“we can maybe do a little at the clinic, the only problem is that […] we have like 4 meters free” [P04]; CaU Theme 1d).

“Evaluation methods”

By testing side-to-side strength measures using “equipment where we test the thigh musculature, quadriceps and hamstrings” (P11; CaU Theme 2a), physical therapists perceive an ability “to evaluate a little what we need to work more with” (P11; CaU Theme 2b). This includes observations (“we see that the patient can handle the load in the gym” [P05]; CaU Theme 2c), or “functional tests, we do 40cm single-leg hop side-to-side, single-leg hop for distance, 3 hops in a row” (P06; CaU Theme 2d), and can be done according to time (“we test them at 3, 6, 9, and 12months” [P05]; CaU Theme 2e).

“Physical therapist philosophy”

Previous research can serve as a basis for a physical therapist-specific strategy (CaU Theme 3a) for program development, with differing views on clinical application (“you read the articles and stuff, you think ‘that’s what I do,’ but you maybe don’t describe it in that way” [P09]). Some believe that “after a traumatic knee injury, it’s pretty much […] the same regardless of what type of injury it is” (P04), while others “absolutely do not have any fixed rehab programs for diagnoses” (P05). Rehabilitation goals (CaU Theme 3b) are based on a perceived personal philosophy, for example, “goal one: full range of motion” (P07).

“Rehabilitation training includes a biopsychosocial interaction”

“Physical–psychological interaction”

Preparing patients for return to activity (CaU Theme 4a) includes shifting focus of attention by introducing unknown factors, for example, “they jump and they get a push in an unknown direction” (P05) and “more event-specific exercises, so say you’re a soccer player, then you maybe do some more ball exercises with them at the same time as you do some stability exercises” (P06). Levels of comfort or fear (CaU Theme 4b) influence execution, because “often there’s, like, a barrier or a lock that, yeah it can be that they need to hop over, or hop up onto a low box or something” (P02). Physical progression can help, since “it often feels really good because when they have accomplished it, even if it’s on a low level, they start to grow in it” (P06). Individual differences (CaU Theme 4c) like training experience (i.e. distinction between “an elite athlete that, like, has done strength training before on a more […] structured level” [P02], and one that has little training experience) also influence strategy development.

“Social interaction”

Social factors from sport may influence rehabilitation (CaU Theme 5a), including the perspective that “some coaches just don’t give a shit what you say anyway, because yeah he’s training fully anyway so yeah, he’s playing a game this weekend” (P04). The interaction between patient and physical therapist (CaU Theme 5b) is important, because “if the patient isn’t thriving with us, or feels safe with- with me as a physical therapist, then it’s probably also hard to be successful” (P11). This includes, for example, adapting schedules (CaU Theme 5c), if “a mom, for example, that has a couple of small kids that maybe doesn’t have time to come so often to me” (P09).

“Psychological factors are important to address, but strategies are lacking”

“Physical therapist psychological strategies”

Psychological strategies (CaU Theme 6a) include providing support (“I talk to them about [their fear]” [P06]), or having patients “fill out a couple times this ACL Ready, I think it’s called” (P06 [referring to the ACL-Return to Sport after Injury scale]). Rehabilitation goals differ, as one patient may want to “‘ride my moped,’ it’s not the same … physical goal as the girl who plays soccer” (P10). Goal-setting includes informing patients that:

you need to do this first, then we can do this, and […] when you have done all those parts, then we can start to look at how you handle the load. So yeah, try to educate the patient in what rehab entails (P07)

Physical therapists perceive a need to focus on “the patient’s own abilities” (P02; CaU Theme 6b), describing psychological factors as “incredibly important, and there’s a lot we could improve” (P11).

“Patient psychological reactions”

Barriers to patients’ rehabilitation progression or execution are important (CaU Theme 7a), including athletic identity (“he lost his identity and wanted to get back to the field to be ‘the best’ again” [P10]), and “poor trust in their knee, and it feels scary to jump, and brake, or just balance on the knee” (P02). It is therefore “important to find that enjoyment, motivation, different goals” (P09). Facilitators (CaU Theme 7b) can include motivation, resulting from a “pat on the back, good job, you did this really well, and they feel strong and build their self-confidence” (P10). This also progresses naturally, as “they figure out themselves that they can do more challenging exercises […], the more their knee confidence grows” (P10).

Discussion

Physical therapists experienced MOTIFS training as a method of influencing psychological factors, indicating increased awareness of strategies to aid in achieving successful rehabilitation outcome goals. CaU training was described mainly in terms of strategies to restore patient strength and function, though psychological factors were perceived as important to meet patients’ needs. Results of this study seem to be in line with previous research and theoretical perspectives in which physical therapists are aware of a need to take an approach in line with the Biopsychosocial Model (Brewer, Andersen, and Van Raalte, Citation2002). PTs in the MOTIFS group report having received concrete tools for taking a more direct approach to addressing psychosocial as well as physical factors. This approach may indicate a shift toward rehabilitation which aligns with the Integrated Model of Response to Sport Injury (Wiese-Bjornstal, Smith, Shaffer, and Morrey, Citation1998). This model lifts the possibility of intervening directly on cognitive appraisal and emotional and behavioral responses (Wiese-Bjornstal, Smith, Shaffer, and Morrey, Citation1998) in contrast with the biopsychosocial approach. In the CaU group, however, the PTs confirm that this is a necessity, but express a lack of tools to be able to take direct action.

MOTIFS rehabilitation

Physical therapists in the MOTIFS group maintain their initial approach to rehabilitation training from a CaU perspective. That is, when presented with a person with a knee injury, the strategy includes evaluation of patient movement and ability in order to plan an effective strategy to restore strength and function. This is likely due to the introduction of MOTIFS training in later phases of rehabilitation, i.e. once hop training has begun (Cederström et al., Citation2021b).

Physical therapists understand the importance of psychological factors, echoing previous calls for more holistic rehabilitation training (Calmels, Citation2019; Piussi et al., Citation2021). They express appreciation for increased focus on, and concrete strategies for, addressing these using the MOTIFS model. The shift toward using the MOTIFS model to integrate psychological and physical rehabilitation training principles (Cederström et al., Citation2021b) was initially confusing, but educational workshops and individual meetings helped to answer questions regarding proper implementation.

This is perhaps not surprising, as they have not previously used this type of training. Preliminary reactions included a feeling that they already used psychological training methods in rehabilitation, potentially due to the fact that they still worked from the same physical rehabilitation principles (i.e. CaU). However, they were able to identify the novel aspects of integrating psychological training using imagery to shift focus toward sensory aspects of the situation to increase meaning and relevance.

Once they understood this, they began to perceive a shift regarding their role, including feeling that they began to be more mindful of providing psychological support than previously. For example, by using contextualization and individualized goal discussions, they felt an increased attention on patient needs and ability to provide psychological coping mechanisms. In line with previous research, they perceived that this subsequently improves self-determined motivation (Deci and Ryan, Citation2000); training quality (Masters and Maxwell, Citation2008; Wulf and Lewthwaite, Citation2016); and results in better physical and psychological readiness to return to activity (Rodriguez, Marroquin, and Cosby, Citation2019; Wesch, Callow, Hall, and Pope, Citation2016; Zach et al., Citation2018).

An interesting result of this is an understanding of patient needs to train sport-specifically, and an expressed desire to introduce this earlier, in contrast to current guidelines which recommend introducing sport-specific training in later phases (Ardern et al., Citation2016; Filbay and Grindem, Citation2019). This is seen as positive and based more on psychological readiness than on physical readiness (i.e. maintaining strict guidelines on activity allowance). Physical therapists seem to attribute this to what they perceived to be the main difference between MOTIFS and CaU training, namely the integration of factors such as sights, sounds, and other imagery-related stimuli (Cederström, Granér, Nilsson, and Ageberg, Citation2021a; Cederström et al., Citation2021b). This indicates a shift from unstructured psychological training to utilizing research-based dynamic motor imagery interventions inspired by Physical, Environmental, Task, Timing, Learning, and Perspective (PETTLEP) aspects of an activity-specific task (Guillot, Moschberger, and Collet, Citation2013; Holmes and Collins, Citation2001). They also perceived imagery as being more difficult in the clinical environment due to the lack of sport-specific cues (i.e. goals and other players) leading to an altered strategy in which the environmental factor was utilized more consciously. This included using on-field or on-court rehabilitation exercises to create a movement that is as physically and psychologically realistic as possible without actually executing the movement, known as functional equivalence (Holmes and Collins, Citation2001). This shows that they perceive a difference between rehabilitation strategies, in which CaU is inherently rehabilitation-specific, and MOTIFS allows for sport-specific rehabilitation training.

Care-as-usual rehabilitation

Physical therapists take a dualistic stance toward treating physical structures and symptoms following a traumatic knee injury, distinguishing between physical and psychological factors. This dualistic as opposed to holistic perspective leads to a primary focus on physical (i.e. musculoskeletal, injury, exercise, and ability-related) aspects with less attention paid to psychosocial factors (i.e. motivation, goals, and social influences).

When presented with a patient (or ‘knee,’ as some participants said) physical therapists perceive their role as being a physical therapist resulting in a focus on restoring function and strength to the knee and surrounding structures, which is in line with ACL rehabilitation recommendations (Andrade et al., Citation2019; Filbay and Grindem, Citation2019; van Melick et al., Citation2016). In order to progress through training, physical therapists look to recommendations to approach rehabilitation through a biopsychosocial lens (Gokeler, Seil, Kerkhoffs, and Verhagen, Citation2018) in an attempt to increase activity specificity. They seem to interpret the biopsychosocial model from a strongly biological perspective, for example, focusing on physical ability to maintain proper landing technique by introducing randomness and unexpected stimuli (i.e. quick change of direction or pushing while in the air). The psychosocial perspective includes shifting focus of attention more externally, though focus is still physical, rather than on contextually relevant sport-specific factors such as arousal levels, teammates, and decision-making.

Psychological factors, such as high motivation and self-confidence, facilitate quality of and compliance to rehabilitation training, and hinder rehabilitation if low or non-existent. Interestingly, these are seen as unmodifiable factors, with several physical therapists laughing while explaining that training is inevitably boring. This indicates a perception that there is nothing to do that will change this, it is outside the physical therapists’ area of expertise, and this is the price to pay to return to activity. This implies that psychological factors cannot be adequately addressed in the clinic, in line with suggested frameworks which recommend the involvement of an external sport psychologist (Hess, Gnacinski, and Meyer, Citation2019).

Physical therapists attempt to address psychological factors, and express a desire for more concrete strategies to fill a knowledge gap. Their current understanding is based on broad and unspecified psychological training strategies, including communication and providing support (i.e. discussing fears and pushing). Goal-setting is perceived as being patient-focused, but instead of including patients (Rose, Rosewilliam, and Soundy, Citation2017) in specific and self-determined goal-setting (Gennarelli, Brown, and Mulcahey, Citation2020) the physical therapist takes responsibility, in line with previous research (Rose, Rosewilliam, and Soundy, Citation2017). This seems to reflect previous indications of a lack of knowledge regarding psychological training (Truong et al., Citation2020).

Strengths and limitations

Strengths include that this is an interview study, in which more thorough and rich data can be collected than in questionnaires. There was also a rigorous standardization and coding process and thorough auditing by coders with backgrounds in psychology and in physical therapy (Lincoln and Guba, Citation1986). The resulting conceptual model therefore provides an interpretation representative of physical therapists’ experiences of rehabilitation of traumatic knee injury.

Limitations include participant familiarity with the interviewer and psychological focus of the MOTIFS study, so interviewer and/or social desirability bias cannot be ruled out. This may include an existing relationship with the interviewer and the purpose of the RCT influencing participant responses. However, the conceptual model was upheld for the entire CaU group, indicating that results were not affected by this potential source of bias. Interviews were limited to physical therapists clinically active in Sweden, which may influence rehabilitation strategies. The number of physical therapists in the MOTIFS condition was limited due to the requirement of having experience with the MOTIFS model. However, the themes stabilized according to pre-defined data saturation criteria and coders were in agreement, so the model was deemed complete and accurate. Different questions were posed depending on group allocation, but as qualitative methodology prevents comparison, this is not seen as detrimental.

Conclusion

Physical therapists perceive MOTIFS training as a method of shifting the rehabilitation paradigm toward a conscious and directed focus on simultaneously addressing psychological and physical factors by creating patient ownership, creativity, and new ways of thinking. This is described as a challenge which requires time and effort to individualize to patients depending on physical and psychological needs and abilities. Care-as-usual training for rehabilitation following traumatic knee injury was described as focusing mainly on aspects of rehabilitation relating to physical training (i.e. strength, hop ability, and range of motion). Psychological facilitators and barriers to return to activity were expressed, as well as a desire for structured psychological interventions. Results of this study indicate that physical therapists are aware of psychological issues but need to be provided with the necessary tools to actively and effectively address those aspects important for rehabilitation outcomes. This may be a reflection of physiotherapy culture and education, in which a dualistic focus is biased toward one aspect of injury and rehabilitation, which in reality is a complex biopsychosocial issue. Using an intervention that can easily be applied to current rehabilitation principles without extensive education may be an effective method of providing education in psychological skills training, though future research is needed to confirm this.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the physical therapists that agreed to participate in this interview study. This work was funded by the Folksam insurance company and the Swedish Research Council for Sport Science. Other funders include the governmental funding of clinical research within the National Health Services (NHS), the Kocks Foundation, the Swedish Rheumatism Association, and the Faculty of Medicine, Lund University.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ageberg E, Thomeé R, Neeter C, Silbernagel KG, Roos EM 2008 Muscle strength and functional performance in patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury treated with training and surgical reconstruction or training only: A two to five-year followup. Arthritis and Rheumatism 59: 1773–1779.

- Andrade R, Pereira R, van Cingel R, Staal JB, Espregueira-Mendes J 2019 How should clinicians rehabilitate patients after ACL reconstruction? A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) with a focus on quality appraisal (AGREE II). British Journal of Sports Medicine 54: 512–519.

- Ardern CL, Glasgow P, Schneiders A, Witvrouw E, Clarsen B, Cools A, Gojanovic B, Griffin S, Khan KM, Moksnes H, et al. 2016 2016 Consensus statement on return to sport from the First World Congress in Sports Physical Therapy, Bern. British Journal of Sports Medicine 50: 853–864.

- Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE 2012 A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. British Journal of Sports Medicine 47: 1120–1126.

- Ardern CL, Taylor NF, Feller JA, Webster KE 2014 Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. British Journal of Sports Medicine 48: 1543–1552.

- Braun V, Clarke V 2021 One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology 18: 328–352.

- Brewer B, Andersen M, Van Raalte J 2002 Psychological aspects of sport injury rehabilitation: Toward a biopsychosocial approach. In: Mostofsky D, Zaichkowsky L, Eds Medical and Psychological Aspects of Sport and Exercise p. 160–183. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Calmels C 2019 Beyond Jeannerod’s motor simulation theory: An approach for improving post-traumatic motor rehabilitation. Neurophysiologie Clinique 49: 99–107.

- Cederström N, Granér S, Nilsson G, Ageberg E 2021a Effect of motor imagery on enjoyment in knee-injury prevention and rehabilitation training: A randomized crossover study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 24: 258–263.

- Cederström N, Granér S, Nilsson G, Dahan R, Ageberg E 2021b Motor Imagery to Facilitate Sensorimotor Re-Learning (MOTIFS) after traumatic knee injury: Study protocol for an adaptive randomized controlled trial. Trials 22: 729–742.

- Czuppon S, Racette BA, Klein SE, Harris-Hayes M 2014 Variables associated with return to sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 48: 356–366.

- Deci EL, Ryan RM 2000 The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 11: 227–268.

- Everhart J, Best T, Flanigan D 2013 Psychological predictors of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction outcomes: A systematic review. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 23: 752–762.

- Filbay SR, Grindem H 2019 Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Rheumatology 33: 33–47.

- Gennarelli SM, Brown S, Mulcahey M 2020 Psychosocial interventions help facilitate recovery following musculoskeletal sports injuries: A systematic review. Physician and Sports Medicine 48: 370–377.

- Gokeler A, Seil R, Kerkhoffs G, Verhagen E 2018 A novel approach to enhance ACL injury prevention programs. Journal of Experimental Orthopaedics 5: 22.

- Guillot A, Collet C 2008 Construction of the Motor Imagery Integrative Model in Sport: A review and theoretical investigation of motor imagery use. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 1: 31–44.

- Guillot A, Moschberger K, Collet C 2013 Coupling movement with imagery as a new perspective for motor imagery practice. Behavioral and Brain Functions 9: 8.

- Hart HF, Culvenor AG, Guermazi A, Crossley KM 2020 Worse knee confidence, fear of movement, psychological readiness to return-to-sport and pain are associated with worse function after ACL reconstruction. Physical Therapy in Sport 41: 1–8.

- Hess CW, Gnacinski SL, Meyer BB 2019 A review of the sport-injury and -rehabilitation literature: From abstraction to application. Sport Psychologist 33: 232–243.

- Holmes PS, Collins DJ 2001 The PETTLEP approach to motor imagery: A functional equivalence model for sport psychologists. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 13: 60–83.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG 1986 But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Directions for Program Evaluation 1986: 73–84.

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD 2015 Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research 26: 1753–1760.

- Masters R, Maxwell J 2008 The theory of reinvestment. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 1: 160–183.

- McHugh ML 2012 Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica: Casopis Hrvatskoga Drustva Medicinskih Biokemicara 22: 276–282.

- McPherson KM, Kayes NM 2012 Qualitative research: Its practical contribution to physiotherapy. Physical Therapy Reviews 17: 382–389.

- Moser A, Korstjens I 2018 Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice 24: 9–18.

- Pietkiewicz I, Smith JA 2014 A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czasopismo Psychologiczne - Psychological Journal 20: 7–14.

- Piussi R, Krupic F, Senorski C, Svantesson E, Sundemo D, Johnson U, Hamrin Senorski E 2021 Psychological impairments after ACL injury - Do we know what we are addressing? Experiences from sports physical therapists. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 31: 1508–1517.

- Podlog L, Dimmock J, Miller J 2011 A review of return to sport concerns following injury rehabilitation: Practitioner strategies for enhancing recovery outcomes. Physical Therapy in Sport 12: 36–42.

- Rodriguez RM, Marroquin A, Cosby N 2019 Reducing fear of reinjury and pain perception in athletes with first-time anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions by implementing imagery training. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation 28: 385–389.

- Rose A, Rosewilliam S, Soundy A 2017 Shared decision making within goal setting in rehabilitation settings: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling 100: 65–75.

- Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, Baker S, Waterfield J, Bartlam B, Burroughs H, Jinks C 2018 Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity 52: 1893–1907.

- Simonsmeier BA, Andronie M, Buecker S, Frank C 2021 The effects of imagery interventions in sports: A meta-analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 14: 186–207.

- Smith B, McGannon KR 2018 Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 11: 101–121.

- Sundler AJ, Lindberg E, Nilsson C, Palmér L 2019 Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nursing Open 6: 733–739.

- Thomeé R, Neeter C, Gustavsson A, Thomeé P, Augustsson J, Eriksson B, Karlsson J 2012 Variability in leg muscle power and hop performance after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 20: 1143–1151.

- Thomeé P, Wahrborg P, Borjesson M, Thomeé R, Eriksson BI, Karlsson J 2008 Self-efficacy of knee function as a pre-operative predictor of outcome 1 year after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 16: 118–127.

- Truong LK, Mosewich AD, Holt CJ, Le CY, Miciak M, Whittaker JL 2020 Psychological, social and contextual factors across recovery stages following a sport-related knee injury: A scoping review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 54: 1149–1156.

- van Melick N, van Cingel RE, Brooijmans F, Neeter C, van Tienen T, Hullegie W, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW 2016 Evidence-based clinical practice update: Practice guidelines for anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation based on a systematic review and multidisciplinary consensus. British Journal of Sports Medicine 50: 1506–1515.

- Von Aesch AV, Perry M, Sole G 2016 Physiotherapists’ experiences of the management of anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Physical Therapy in Sport 19: 14–22.

- Wesch N, Callow N, Hall C, Pope JP 2016 Imagery and self-efficacy in the injury context. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 24: 72–81.

- Wiese-Bjornstal DM, Smith AM, Shaffer S, Morrey M 1998 An integrated model of response to sport injury: Psychological and sociological dynamics. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 10: 46–69.

- Wulf G, Lewthwaite R 2016 Optimizing performance through intrinsic motivation and attention for learning: The OPTIMAL theory of motor learning. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review 23: 1382–1414.

- Zach S, Dobersek U, Filho E, Inglis V, Tenenbaum G 2018 A meta-analysis of mental imagery effects on post-injury functional mobility, perceived pain, and self-efficacy. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 34: 79–87.

- Zarzycki R, Failla M, Capin JJ, Snyder-Mackler L 2018 Psychological readiness to return to sport is associated with knee kinematic asymmetry during gait following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 48: 968–973.

Appendix

Methodological rationale for using coding reliability thematic analysis

Methods – Data Analysis

Participants were recruited from the ongoing MOTIFS RCT, as well as from other parts of Sweden in order to provide CaU data representative of the physical therapy profession from a wider geographical perspective. Data was analyzed using notes taken during both the interview and transcription (as audio and video were available). This reflected non-verbal cues potentially relevant to meaning, such as laughing or pausing. It was not deemed necessary to return transcripts to participants for correction nor to send findings to participants for feedback. Prevalence of generated themes was noted, though the authors determined that the fact that mention was made warranted presentation in the model.

After the Primary Coder (NC; first author) had inductively coded and generated a preliminary conceptual model, inter-coder agreement was evaluated in order to ensure that the conceptual model is reflective of what is actually said and meant by the interview participants (Sundler, Lindberg, Nilsson, and Palmér, Citation2019). This serves as an auditing process to create a model that is not influenced by background or bias of one individual coder. As 2 coders have backgrounds in sport psychology (NC and SG) and one has expertise in physical therapy (EA), this was used as a method of ensuring rigor in the coding process and provides different perspectives, which in turn can result in a model which is more likely to accurately represent participant responses and be recognizable by the target audience (i.e. clinically active physical therapists). The primary coder provided a preliminary model with theme definitions to coders 2 and 3 (native Swedish speakers, fluent in English). The Coding Comparison Query tool available from QSR International’s NVivo 12 qualitative data analysis software (released March 2020) was used to evaluate the conceptual model’s face validity and agreement between coders. Coder 2 (SG) received the model first and deductively coded an interview to a priori themes up to subordinate level 2. A Kappa value was calculated based on inter-coder agreement by comparing number of characters coded to the same theme (), with k = 0.61 determined to be acceptable (McHugh, Citation2012). If not reached, coding was discussed to resolve issues and calibrate the model and/or theme definitions. This process was repeated with Coder 3 (EA) until all coders were in agreement with the conceptual model. The data collection and analysis process is presented in .

Table A1. Coding comparison analysis progression through versions of the generated conceptual models.

Table A2. Description of data collection and analysis process, including Coder roles and involvement.