ABSTRACT

Background

Social media offer opportunities for informal learning and are increasingly adopted by health professionals as learning tools. However, little is known of how new graduate physiotherapists engage with social media for learning.

Purpose

This study aimed to explore new graduate physiotherapists’ perceptions and use of social media as learning tools during their transition into professional practice.

Methods

This study used a qualitative general inductive approach. New graduate physiotherapists (n = 16) were recruited through purposive snowball sampling and participated in semi-structured interviews. Data were subjected to a general inductive analytical method.

Results

Four themes were generated: 1) social media as tools for learning; 2) navigating and engaging with social media as a learner; 3) thinking critically about social media; and 4) relevance to practice.

Conclusion

New graduate physiotherapists use social media as adjunct learning tools which can be positioned within several frameworks, including the Situated Learning Theory. However, new graduates voice uncertainties regarding information credibility, the importance of critical thinking skills in navigating information, and concerns regarding blurred work-life boundaries. Recommendations are made for research to further understand social media as emerging learning tools, especially for new graduates who are experiencing insufficient workplace support.

Introduction

The transition from being a supervised learner to an autonomous practitioner requires new graduates to become accountable for continuing professional development (PD) through formal and informal learning activities (Bennett, Grimsley, Grimsley, and Rodd, Citation2017; Farsi, Citation2021; Kind, Genrich, Sodhi, and Chretien, Citation2010; Leahy, Chipchase, and Blackstock, Citation2017). The exponential rise of social media (SM) has influenced the way new graduate health professionals learn, and has created new opportunities to undertake informal learning (De Gagne et al., Citation2018; Milošević, Živković, Arsić, and Manasijević, Citation2015).

Within the existing literature, the term “SM” has generally been used to describe online tools with a variety of functions, including social networking, video and photo sharing, blogging, podcasting, social gaming, creating and sharing of user-generated content, product reviewing, social bookmarking, and microblogging (Aichner, Grünfelder, Maurer, and Jegeni, Citation2020). This suite of tools creates virtual opportunities for digital health, collaborative projects and forums, and enterprise networks (Aichner, Grünfelder, Maurer, and Jegeni, Citation2020; Coughlin, Roberts, O’Neill, and Brooks, Citation2018). The definition of SM is ever-changing with its evolution, and it is increasingly recognized as emerging tools for information aggregation and learning by health professionals (Farsi, Citation2021; Kapoor et al., Citation2018; Scott and Goode, Citation2020). The current literature shows that health professionals consider SM as innovative and effective tools for learning (Fahimi, Citation2018; Maloney et al., Citation2015). Its implementation into practice has also been positioned within several learning theories, including the Situated Learning Theory (SLT) (Chu, Citation2020; Flynn, Jalali, and Moreau, Citation2015; Ignacimuthu and Kumar, Citation2020). It can therefore be expected that new graduates will need to navigate these informal learning tools during their formative years in the profession.

The first two years of a physiotherapist’s career have been identified as a critical learning period (Hayward et al., Citation2013) and current literature indicates new graduate physiotherapists feel ill-equipped when entering the workforce (Stoikov et al., Citation2022). Given that health professionals prefer to learn through secondary sources such as summarized research evidence (Dawson, Citation2010; De Leo, LeRouge, Ceriani, and Niederman, Citation2006; Pander, Pinilla, Dimitriadis, and Fischer, Citation2014) and physiotherapists find informal ways of learning useful for developing confidence (Pettersson, Bolander Laksov, and Fjellström, Citation2015). SM is anticipated to play a role in new graduate physiotherapists’ PD. Literature on physiotherapy students’ perceptions and use of SM for learning has suggested that the use of SM as adjuncts to pre-professional learning will continue to increase, with likely transference into new graduates’ PD practices (Depala and Greene, Citation2016; Nagi-Watkins and Carpenter, Citation2016). However, no research to date has specifically explored new graduate physiotherapists’ use or perspectives of SM as learning tools during their early, critical learning period. Given concerns regarding the reliability of information presented via SM and new graduates’ susceptibility to false information it is imperative to understand how new graduate physiotherapists are using these tools to learn (Booth, Citation2015; D’Souza et al., Citation2021; Wilkinson and Ashcroft, Citation2019). As identified by a recent systematic review (Bruguera, Guitert, and Romeu, Citation2019) initial research in this space has been predominantly survey-based and there has been little qualitative investigation on the role of SM and its perceived impact on learning. To better understand this developing field, further exploratory research may be helpful. Therefore, the aim of this qualitative study is to add to the current body of research by exploring new graduate physiotherapists’ perceptions and use of SM as learning tools in their transition into professional practice.

Methods

Design

Ethical clearance for this study was provided by the University of Queensland Institutional Human Research Ethics, approval number #2021002523. A qualitative research design using a general inductive approach was used to address the study aims, enabling participants to express perspectives without prior assumptions, theories, or hypotheses (Thomas, Citation2006). Semi-structured interviews were chosen to facilitate open discussions and allow detailed exploration of SM as a learning tool from new graduates’ perspective (Cohen and Crabtree, Citation2006).

Participants

As per the inclusion criteria, eligible participants must have graduated from an Australian physiotherapy program within the previous two years and have been actively employed as a registered physiotherapist in the workforce for a minimum of four weeks (Chipchase, Williams, and Robertson, Citation2008). New graduate physiotherapists were recruited through a purposive, snowballing strategy (Naderifar, Goli, and Ghaljaei, Citation2017). Professional networks of the research team including practice employers, previous graduates, and clinical educators were utilized to identify new graduate physiotherapists who met the inclusion criteria. Three members of the research team (AM, RF, RM) approached 29 potential participants with an invitation e-mail, which detailed the study’s aim and inclusion criteria. To express interest in participating in the study, the potential participants were asked to respond by providing their contact number and availability for interviewing. Follow-up e-mails were then sent to individual participants to propose a mutually suitable interview time, and to supply the participant information sheet and the consent form. Participants were also encouraged to contact other eligible participants (e.g. colleagues and former peers) who if interested, provided consent to be contacted for the study. Participants were asked to confirm interview details and return the signed consent form via e-mail reply. If this was not received within seven days, snowball sampling continued with other contacts collected through participants. This process continued until data saturation was determined by the research team and remaining participants were notified by e-mail if participation was no longer needed.

Data collection and interview procedure

Following an initial review of previous literature in this field (Depala and Greene, Citation2016; Maloney et al., Citation2015; Nagi-Watkins and Carpenter, Citation2016; Pizzuti et al., Citation2020) the primary researcher (TM) developed a semi-structured interview framework () containing open-ended and probing questions. The draft framework was revised by the research team to ensure that interview questions were unbiased, succinct, and appropriate in addressing the study’s aim.

Table 1. Example semi-structured interview questions and probing questions.

The primary researcher (TM) conducted all interviews (n = 16) via telephone, which allowed flexibility in scheduling and inclusion of geographically dispersed participants (Sturges and Hanrahan, Citation2004). An external recording device audio-recorded all interviews for transcription. Before each interview, verbal consent for audio-recording was reaffirmed. Participants were reminded of their right to withdraw and de-identification, prior to providing demographic information (). The research aim was restated, and the term SM was defined (Aichner, Grünfelder, Maurer, and Jegeni, Citation2020). All interviews were guided by the interview framework () to achieve sufficient depth of responses (DeJonckheere and Vaughn, Citation2019). Interviews were conducted between June and July 2022 and ranged from 28 to 42 minutes (mean = 35 minutes).

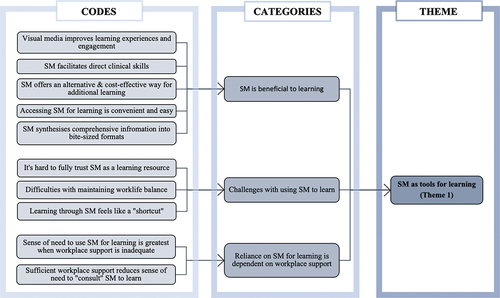

Figure 1. Theme 1 as an example to illustrate the general inductive approach to qualitative data analysis (Thomas, Citation2006) (SM = social media).

Table 2. De-identified participant demographic information.

To refine the direction of data collection, the research team regularly restructured the interview guide using a reflexive approach (Pessoa, Harper, Santos, and Gracino, Citation2019). This involved selectively exploring aspects of the study aims that lacked data from previous interviews capturing further details where required. Interviews were discontinued when data saturation was considered by the team to be reached, where no further themes or ideas were identified.

Data analysis

All audio recordings were transcribed with an automatic speech-to-text software. The primary researcher (TM) re-listened to the recordings and manually corrected transcriptions prior to data analysis. A general inductive approach was used as it condenses extensive raw text data into brief summaries and establishes clear links with the research aims (Thomas, Citation2006). Analysis followed the procedures described by Thomas (Citation2006): 1) data cleaning of raw files; 2) close reading of text; 3) creation of categories; 4) overlapping coded and uncoded text; and 5) continuing refinement of categories.

The primary researcher (TM) completed multiple close readings of each transcript for data immersion and inductively annotated meaningful ideas with codes. Codes with similar underlying concepts were grouped into categories, which were further organized into preliminary themes (). This process was repeated independently by a second member of the research team (RM). The research team openly discussed differences in data interpretation across five meetings to determine the final themes. Supporting quotations conveying the codes and categories of each theme were selected (Appendix).

Integrity and reflexivity of data analysis were maximized through several strategies. Interview transcripts were returned to participants for member checking to confirm data accuracy. The secondary researcher (RM) independently reviewed all recordings and transcripts to enhance credibility of analysis. Participants were not known to the interviewer (TM) and leading questions were avoided. Additional strategies included: systematic data collection with adherence to the pre-established interview framework, accurate transcription of interviews to minimize assumptions, and regular team meetings to discuss analytical processes.

Members of the research team (TM, LL, RM, AM, RF) were familiar with the physiotherapy profession and ensured transparency of data analysis by acknowledging individual differences in experiences, characteristics, and perspectives. The primary researcher (TM) was a final year physiotherapy student with some experience with using SM for learning at the time of the study. The secondary researcher (RM) is a practicing physiotherapist and qualitative researcher of new graduate physiotherapy education and practice.

Results

Sixteen new graduate physiotherapists (n = 16) met the inclusion criteria and provided written consent for interviewing. Four overarching themes were generated following analysis: 1) SM as tools for learning; 2) Navigating and engaging with SM as a learner; 3) Thinking critically about SM; and 4) Relevance to practice. Supporting quotes are provided under each theme, with additional supporting quotes outlined in the Appendix.

The interrelationships between the four themes are displayed pictorially in . “SM as tools for learning” is portrayed as the bridge, supported by the pillars of “thinking critically about SM.” The new graduate physiotherapist’s transition from university to professional practice is assisted by this bridge, where they can “navigate and engage with SM as a learner” but must reflect to consider its “relevance to practice.”

SM as tools for learning

Participants shared similar experiences using SM as tools for learning during their transition into professional practice. The use of SM spanned learning across a wide range of physiotherapy knowledge and skills, although most participants described SM as best positioned to facilitate direct clinical skills.

I definitely use [SM] as a learning tool … it’s really helpful, particularly Instagram and YouTube videos… they kind of give you exercise ideas, progressions, that side of things… (P10)

For some participants, SM offered opportunities to gain a sense of awareness of what is happening in the profession as they felt SM reflected up-to-date practices and often highlighted professional issues.

I think [SM] is a great tool to open your eyes into what’s out there … new techniques or new findings or new research … (P15)

It’s a good snapshot of the physiotherapy profession, to see what the politics are like and to see … the direction of the whole profession is going which I find you don’t really see that in other places… (P6)

Participants also acknowledged advantages of using SM for learning. The various modes of content delivery offered via SM were perceived as beneficial for providing alternative ways to learn. Visual media, such as images, videos, and infographics, were felt by some participants to improve learning engagement and understanding of information.

Something eye-catching like a video is going to summarize an article a lot better … like a picture portrays a thousand words … (P1)

A lot of times on Instagram or YouTube videos, you can get some really good visualizations, for example, like, seeing how the hip moves with FAI … I saw a video on that and thought it was really interesting to see exactly how it was moving. (P3)

While SM were perceived to be “helpful” (P3) and “useful” (P8) as “adjuncts” (P12) to learning, participants believed that they shouldn’t “replace” (P5) traditional learning strategies. However, where time and cost were seen as barriers to accessing formal PD, it was felt that SM can offer alternative ways for pursuing additional learning cost-effectively.

There are all these courses, but the problem is they’re expensive, there’s not that much you can access easily … in terms of broad professional development, the easiest way to learn a lot quickly is online … Twitter … podcasts … (P12)

Learning via SM was believed to be made easier by some participants, as comprehensive information were often “synthesized” (P9) into “more digestible” (P1 and 6) “snippets” (P1). Further, participants found the “accessible” (P1, 6, 10 and 16) and “convenient” (P1, 5, and 12) nature of SM allowed learning to be more seamlessly integrated within everyday life. This helped them overcome challenges around finding time outside of work hours to continue professional learning and stay “up-to-date” (P5) with new evidence.

It’s easier to keep up with evidence-based practice without having to read whole articles … there’s a couple of pages on Twitter and Instagram that summarize the newest research findings pretty well. (P2)

I found that social media snippets, like looking at Instagram pages, sorta keeps me in the loop of things … It’s a lot easier than having to set out time and do my own research. (P1)

However, some participants perceived the use of SM as a “shortcut approach” (P16) to learning, given the ease of access to information on SM in comparison to consulting traditional resources. For this reason, it was felt that information presented on SM were “harder to trust” (P4), especially when considering clinical practice.

I’d never go to social media to look for information, potential answers, or solutions to treatments … I’d always use textbooks, articles, talk to experienced people, peer support … (P16)

Because SM are so intertwined with most participants’ social and personal lives, some participants voiced challenges with maintaining a work-life balance when SM permeated both personal and professional roles. Some participants extended that SM is more appropriate for “relaxation” (P4 and 13) purposes, as using these tools for learning as well was felt to create a “dangerous trap … from a mental wellbeing point of view” (P4).

A challenge with following (clinical) pages on my Instagram account is when I’m at home scrolling and something pops up, like treatment ideas … it makes me think about work in non-work hours … it’s difficult to not think about work when scrolling at home. (P10)

Workplace support was perceived to influence the frequency of SM use for learning. Where participants felt unsupported by supervisors, and subsequently “desperate for knowledge” (P12), a greater sense of need to “consult” (P15) SM to learn and “make clinical decisions” (P15) was experienced.

A lot of the time, I felt quite like I had to make a lot of decisions on my own, and I felt that I was consulting social media quite a lot when working in that unsupported setting … (P15)

Participants suggested that having sufficient workplace support, with regular PD and supervision hours, reduced their dependence on SM to fill perceived “knowledge gaps” (P12).

It definitely depends on the support structure you have at work … my workplace has really good mentorship when bringing in new grads, so I didn’t really feel the need to go looking for anything myself. (P12)

Navigating and engaging with SM as a learner

Participants’ engagement with different SM tools varied due to differences in the way information was organized. Specifically, learning through Instagram was felt to be more passive and “incidental” (P14), as information “just appears” (P14) once content creators have been followed. Whereas, on other platforms such as Twitter, LinkedIn, and Podcasts, information needed to be actively sought out, bringing challenges associated with sifting through “the sheer amount of content” (P14).

On Instagram, videos and pictures are right there in front of you, whereas Twitter, you have to scroll through and actually read it … and similarly for LinkedIn and other social media sites like that, I have to be looking for something specific otherwise, there’s just too much information to go through. (P2)

Participants used SM to “view” (P3), “save” (P2) and “share” (P6) relevant information with colleagues and other new graduate physiotherapists. Whether participants utilized a “tag” (P7) on the direct post or a “share” (P1, 3 and 7) through online chat systems or “stories” (P7), the act of sharing on SM was viewed as opportunities to share learning. Additionally, being able to also share with those from other workplaces gave some participants a sense of connection, which made learning feel less of an independent endeavor.

It’s really easy to share an exercise or a topic to friends and colleagues (on SM) … we’ll bounce ideas back and forth … they may even introduce me to resources I might not have found on my own … (P1)

When I see something new, I’ll discuss it with my new graduate friends online … because all my friends work in different places, I feel like we can put all our heads together, get a broader perspective … (P15)

The sharing of SM content also occurred between participants and supervisors through “discussions” (P11 and 14), which were perceived as helpful for guiding the application of online content into clinical practice. Some participants appreciated supervisors sharing relevant past experiences, as it was felt to offer clinical context for the content and to assist with “clinical reasoning” (P15). Interestingly, some supervisors encouraged the use of SM as informal learning tools; in these cases, participants found they were more accepting of SM for additional learning.

When I speak to my field managers and mentors about having difficulties with X, Y, and Z, one of the top things they suggest is to follow so-and-so on social media or to check out certain pages for their great content. (P10)

Thinking critically about SM

When learning via SM, participants emphasized the need to take information “with a grain of salt” (P1, 4, 6, 9, 10, 13 and 15) as SM are open to the general public for content creation and consumption. Information on SM were described as “double-handled” (P16), reflecting “interpretations” (P4) and “opinions” (P3 and 7) of others rather than of factual evidence. Most participants believed that information displayed on SM can contain biases and subsequently lack validity. Thus, probing of information credibility and reliability was felt to be warranted when using SM to learn.

It’s harder to take things on social media seriously … you don’t necessarily know the person behind it or the bias they might bring … it’s essentially seeing information second-hand. (P4)

You can’t trust everything you see on social media … it’s heavily opinion-based … any average person can jump on social media and say what they want. (P16)

Participants recognized a fundamental purpose of SM to entertain and captivate. SM content created to gain traction, such as posts with over-promising “quick fixes” (P7), were frequently observed. These types of content were perceived to lack evidence, as information were often “too generalized” (P4) and “not patient-specific” (P16). A need to be “careful” (P3), “skeptical” (P11), and “wary” (P4) was felt by most when determining the appropriateness of content for learning.

I question posts that are very black and white … really general broad statements like ‘Five BEST exercises to do for low back pain’ … there really isn’t five best exercises, there’s best exercises for different people in different situations … (P5)

Participants often sought referenced literature in SM posts to determine whether the information are “backed by research” (P16) and “governed by science” (P7). This was perceived as important especially prior to “implementing” (P4) knowledge or skills learned from SM into clinical practice. Most participants believed they had the skills to critically appraise such literature, however, were limited by the discontinuation of access to scholarly journals through university after graduation. Participants felt their limited access to primary sources of information impaired their abilities in critical thinking, and was a barrier to discerning information credibility when learning via SM.

If I’m applying (SM content) to patients, I’m not just going to listen or just look at whatever that post says, I’ll check the journal papers that’s usually attached to those posts … but it’s pretty hard to look them up because our [university] library access got deactivated six months after graduation (P3)

Discerning credibility and reliability of content was perceived by most participants as the greatest challenge associated with learning via SM.

The main challenge would be deciding what’s reliable, what’s not, and which perspectives to trust … (P2)

A range of strategies were described to provide participants with a sense of confidence in “knowing” (P3) when and how to apply information acquired online. Although this process was not clear-cut, most participants recognized the need to combine their critical thinking skills with preexisting knowledge to “critically reason” (P15) and navigate SM tools for learning.

We have our background knowledge and really good critical thinking skills developed from university … being able to critically think has been the main thing … (P1)

The important skills of critical thinking were believed to be “taught” (P9 and 15) and developed during participants’ university education. These skills not only provided participants with a greater sense of confidence in navigating SM to learn but were also considered to be vital during their critical period of new graduate learning.

Through everything we’ve been taught (in university), I feel relatively comfortable in my skill set and ability to analyse and interpret things … see if something holds up using evidence … I feel quite confident that I won’t be led astray. (P9)

Due to the perceived surge of SM use and prevalence, participants expressed an increasing need for universities to equip students to navigate SM for learning, including how to discern information credibility and reliability.

I think social media should be covered in our (physiotherapy) undergraduate degree … like, how to navigate it … because it’s huge now, there’s so much misinformation but there’s also so much good. (P7)

Relevance to practice

Most participants specifically sought out SM content perceived as relevant to their current clinical practice and felt that actively “applying” (P15) this information or skill helped with knowledge retention. Most participants recounted experiences where knowledge acquired from SM represented as a range of content from diagnostic tests, treatment ideas, to patient education had directly facilitated their clinical practice.

I always go to the posts on scans, because patients always get scans and go ‘Oh my God, I’ve got five disc bulges in my back, that’s horrific, what does that mean?’ and I can point them towards the statistics and reassure them that this is pretty normal …(P12)

Conversely, some participants found it “rarely appropriate” (P14) to apply content from SM within their work setting. However, engaging with content that may not have direct clinical relevance to their typical caseload was felt as an opportunity to “refresh” (P3 and 15) the knowledge and skills of other areas of the profession. This offered participants a sense of preparedness for practice in clinical areas where they may have less experience. SM were thus perceived as supplements that consolidated and furthered existing clinical knowledge, which were believed to help maintain skills expected of a registered physiotherapist.

I use musculoskeletal [Instagram pages] more to keep up with my musculoskeletal knowledge while I’m not doing musculoskeletal like at all in my current job, like my knowledge is really low because if you don’t practice it, you lose it. (P6)

Discussion

This study explored new graduate physiotherapists’ perspectives and use of SM when transitioning into professional practice. Our findings show SM are viewed as adjunct learning tools that promote social approaches to learning and experience-mediated learning. New graduates within the current study used SM to learn through purposefully searching and pursuing information yet also described learning from SM in incidental ways. Importantly, new graduates noted advantages of SM over traditional routes of PD especially when workplace support was perceived as inadequate. Acknowledging the informal nature of SM, new graduates voiced uncertainties regarding information credibility, the importance of critical thinking skills in navigating content, and concerns with blurred work-life boundaries.

Younger age and fewer years of clinical experience have been identified as positive predictors for SM use by health professionals (Chan and Leung, Citation2018). New graduates within the current study, possessing both attributes, similarly reported engaging with SM in various ways to facilitate learning outside of work hours. This corroborates Pizzuti et al. (Citation2020), who conducted an electronic survey to explore health professionals’ views on using SM for educational purposes. The study found that out of 1,503 respondents, nearly 85% agreed or strongly agreed that SM are effective learning tools in healthcare, and 43% of SM users specifically sought opportunities for learning. Also consistent with previous research (Panahi, Watson, and Partridge, Citation2014; Ventola, Citation2014) the current study suggests that new graduates considered accessing up-to-date information quickly and in “digestible” formats on SM as opportunities to learn and keep up with evidence-based practice across various areas of the profession. Some new graduates within the current study also expressed that SM required far less time and cost commitment in comparison to traditional PD, allowing for unlimited informal learning opportunities. Previous research has identified cost and time constraints as prominent barriers to PD for not only new graduate physiotherapists but also other health professionals internationally (Ikenwilo and Skåtun, Citation2014; Stevens and Wade, Citation2017; Zou, Almond, and Forbes, Citation2021). The findings of the current study add to the current literature by suggesting a possibility for SM tools to be viable solutions for such barriers.

Given the prevalence of misinformation on SM (Morosoli et al., Citation2022), there is widespread skepticism and concern with SM being used for information sharing in healthcare (Chretien, Azar, and Kind, Citation2011). This was strongly reflected in our study, where new graduates expressed hesitations to rely on SM for learning due to concerns regarding credibility. This has been similarly reported in the literature, where physicians were reluctant to accept information related to medical knowledge or practice shared on SM due to a lack of trust (Panahi, Watson, and Partridge, Citation2014). To overcome the challenges with navigating SM and evaluating information credibility for learning, new graduates of the current study consistently relied on their critical thinking skills. Critical thinking skills that new graduates reported using included interpreting SM content with a “grain of salt”, and reflecting on who created the SM content and their motivations for doing so. Critical thinking has been defined as “a deliberate process used to evaluate information with a set of reflective attitudes that guide thoughtful beliefs and actions” (Mertes, Citation1991) and has been identified as an essential skill for recognizing misinformation (Machete and Turpin, Citation2020). Rose-Wiles (Citation2018) recommended university providers assist students in evaluating information sources by fostering lifelong critical-thinking and information-literacy skills. Our study adds a perspective to the literature, highlighting new graduates’ perceived importance of critical thinking skills when navigating SM in health professional contexts, and the role of university training in developing such skills. Further research is warranted to explore how universities can best prepare new graduates with critical thinking skills to navigate SM when they enter the workforce.

When transitioning into the workforce, health professionals encounter a steep learning curve and significant challenges with allocating time to developing clinical skills for practice (Sturman, Tan, and Turner, Citation2017; Zou, Almond, and Forbes, Citation2021). With such challenges also faced by new graduates, the current study supports the potential of SM in providing concise and contemporary information that can be accessed readily for learning and, in some cases, integrated into clinical practice. These findings corroborate a mixed-methods study, which indicated that out of 317 clinicians across multiple health disciplines and countries most believed learning via SM had influenced their practice and enhanced their clinical use of research evidence (Maloney et al., Citation2015). However, some new graduates from the current study expressed that information accessed from SM can lack evidence and may be inappropriate for application to individual clinical situations. This limitation of SM was especially difficult to navigate for new graduates who no longer had access to scholarly journals through their previous university of study. As physiotherapists are first-contact practitioners in Australia (Australian Physiotherapy Association, Citation2022) students and new graduates should be guided to recognize SM content that may be inappropriate, dangerous, or outside the scope of physiotherapy. This study thus supports the existing literature in prompting organizations to implement SM policies with greater practical guidance for health professionals (Hennessy, Smith, Greener, and Ferns, Citation2019) to not only assist the navigation of these emerging tools for learning, but to also ensure the quality of care provided in clinical practice.

Of concern, SM were perceived to provide a more valuable avenue for clinical learning by new graduate physiotherapists with less perceived workplace support in this study. These findings have important implications for employers and workplaces, where high-quality mentoring and workplace support has been identified to be critical in new graduate physiotherapists’ transition into the workplace (Lao, Wilesmith, and Forbes, Citation2022). Our study contributes to this existing research by suggesting that although SM may offer additional advantages to those who lack workplace support, how new graduates navigate ongoing concerns regarding the credibility and reliability of SM in situations where they lack sufficient workplace support, is an area that warrants further research.

The SLT argues that learning is most effective within collaborative group settings and during authentic activities situated in real-life experiences (Lave and Wenger, Citation1991). The internet has been described as a “powerful medium” for learning as it is able to facilitate the above characteristics of SLT (Oliver and Herrington, Citation2000). Our study has suggested how SM may also enable key characteristics underpinning SLT. New graduates recounted elements of sharing SM posts with colleagues and supervisors, which provided an impetus for discussions and collaboration perceived to contribute to clinical learning. This parallels the concept of “Communities of Practice” introduced in SLT, which highlighted that practitioners learn with and from each other in practice (Lave and Wenger, Citation1991). Similarly, literature has found SM to facilitate higher-level learning through such knowledge-sharing and collaborating with peers, colleagues, and experts in their community of practice (Ansari and Khan, Citation2020; Meyer, Citation2010). Further, new graduates within the current study sought out and engaged with SM content that could be applied directly into clinical practice. Such practice also relates to the SLT, which argues that learning is more effective when undertaken in the context in which it is applied (Lave and Wenger, Citation1991). The process of practicing knowledge acquired from SM in clinical settings may make the process of learning more effective for new graduates, as experience-mediated learning promotes a deeper understanding of acquired knowledge (Marks and McIntosh, Citation2006) and boosts learning productivity in health professionals (Cadorin, Bagnasco, Rocco, and Sasso, Citation2014). However, the role of SM in promoting social approaches to learning and experience-mediated learning have not yet been investigated in physiotherapy. Future research should explore the potential use of SM in creating and sustaining formal and informal communities of practice and how these may contribute to PD.

The current study introduced potential challenges with maintaining work-life balance when SM are used by new graduate physiotherapists for additional learning. Given current concerns regarding burnout and workforce attrition of physiotherapists (Bacopanos and Edgar, Citation2016; Carmona-Barrientos et al., Citation2020), the impact of SM on job satisfaction and workforce retention should be an area for future research.

Implications

The study findings highlight the importance of critical thinking skills in countering the challenge of discerning information credibility prevalent in SM. University providers should consider how students and new graduates can be equipped to navigate SM and potential misinformation. The use of learning activities that promote critical thinking should be considered, including: explicit instruction, teacher questioning, and active and cooperative learning strategies (Zhao, Pandian, and Singh, Citation2016). Additionally, healthcare stakeholders should also consider new graduates’ access to research as an important factor in implementing research into practice and maintaining a contemporary workforce. This study hopes to inspire further research on SM as emerging clinical learning tools, with a focus on informing the design of future university curricula for guiding SM use within physiotherapy and other health professions. Further research is warranted to explore SM as tools that encourage experience-mediated learning and social approaches to learning, and how this may contribute to PD and career intentions of health professionals. Lastly, given the challenges with maintaining work-life balance when SM are used and the increased reliance on SM where there is perceived inadequate workplace support, research into these areas is warranted to better understand how SM can be optimized to assist new graduates’ transition into professional practice.

Strengths and limitations

The implementation of a qualitative study design and use of semi-structured interviews generated in-depth exploratory data, which was a key strength given current gaps in the existing literature. Additional strengths included investigator triangulation through secondary data analysis and member checking to enhance trustworthiness.

However, several limitations must be considered. Primarily, response bias may have impacted the findings, as participants were aware of the research aim and may have altered responses in attempts to be helpful (Latkin et al., Citation2016). Further, despite reassurance of confidentiality, participants may have avoided discussions of negative experiences due to sensitivity regarding their employment. Secondly, the use of telephone interviews inhibited non-verbal communications, which may have restricted rapport building and subsequently impacted participants’ inclination to share honest perspectives (Novick, Citation2008). Lastly, the use of a purposive snowball sampling strategy introduces selection bias as avid SM users are more likely to express interest in participating in a study about SM. This precludes the recruitment of a representative sample of the population, and in addition to the small sample size, the generalizability and internal validity of our research findings may be limited. Moreover, this study only explored the perspectives of new graduate physiotherapists working in Australia. Given the rapidly increasing use and prevalence of SM globally, triangulation of data with those from other countries and further qualitative research with larger sample sizes should be considered.

Conclusion

SM are adjunct learning tools that may support new graduate physiotherapists with transitioning into professional practice and overcoming traditional barriers to PD. Given the informal nature of SM, critical thinking skills were identified as essential in navigating and discerning information credibility. New graduate engagement with SM can be situated within several learning frameworks, including the SLT which posits SM as opportunities for shared and collaborative learning. New graduates expressed the value of SM in facilitating their transition into clinical practice, especially when workplace support was perceived to be inadequate. Recommendations are made for future research to further understand SM as emerging clinical learning tools.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the physiotherapists who participated in this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aichner T, Grünfelder M, Maurer O, Jegeni D 2020 Twenty-five years of social media: A review of social media applications and definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 24: 215–222. 10.1089/cyber.2020.0134.

- Ansari J, Khan N 2020 Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning. Smart Learning Environments 7: 9. 10.1186/s40561-020-00118-7.

- Australian Physiotherapy Association 2022 What is physio? Physiotherapists help improve quality of life. https://choose.physio/what-is-physio.

- Bacopanos E, Edgar S 2016 Identifying the factors that affect the job satisfaction of early career Notre Dame graduate physiotherapists. Australian Health Review 40: 538–543. 10.1071/AH15124.

- Bennett L, Grimsley A, Grimsley L, Rodd J 2017 The gap between nursing education and clinical skills. ABNF Journal 28: 96–102.

- Booth RG 2015 Happiness, stress, a bit of vulgarity, and lots of discursive conversation: A pilot study examining nursing students’ tweets about nursing education posted to Twitter. Nurse Education Today 35: 322–327. 10.1016/j.nedt.2014.10.012.

- Bruguera C, Guitert M, Romeu T 2019 Social media and professional development: A systematic review. Research in Learning Technology 27: 2286. 10.25304/rlt.v27.2286.

- Cadorin L, Bagnasco A, Rocco G, Sasso L 2014 An integrative review of the characteristics of meaningful learning in healthcare professionals to enlighten educational practices in health care. Nursing Open 1: 3–14. 10.1002/nop2.3.

- Carmona-Barrientos I, Gala-León F, Lupiani-Giménez M, Cruz-Barrientos A, Lucena-Anton D, Moral-Munoz J 2020 Occupational stress and burnout among physiotherapists: A cross-sectional survey in Cadiz (Spain). Human Resources for Health 18: 91. 10.1186/s12960-020-00537-0.

- Chan W, Leung A 2018 Use of social network sites for communication among health professionals: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 20: e117. 10.2196/jmir.8382.

- Chipchase L, Williams M, Robertson V 2008 Preparedness of new graduate Australian physiotherapists in the use of electrophysical agents. Physiotherapy 94: 274–280. 10.1016/j.physio.2008.09.003.

- Chretien K, Azar J, Kind T 2011 Physicians on Twitter. JAMA 305: 566–568.

- Chu S 2020 Learning theories and social media. In: Chu S Ed. Social Media Tools in Experiential Internship Learning, pp. 47–57. Singapore: Springer. 10.1007/978-981-15-1560-6_4.

- Cohen D, Crabtree B 2006 Qualitative research guidelines project. http://www.qualres.org/.

- Coughlin S, Roberts D, O’Neill K, Brooks P 2018 Looking to tomorrow’s healthcare today: A participatory health perspective. Internal Medicine Journal 48: 92–96. 10.1111/imj.13661.

- Dawson J 2010 Doctors join patients in going online for health information. New Media Age 7: 596–615.

- De Gagne J, Yamane S, Conklin J, Chang J, Kang H 2018 Social media use and cybercivility guidelines in U.S. nursing schools: A review of websites. Journal of Professional Nursing 34: 35–41. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.07.006.

- DeJonckheere M, Vaughn L 2019 Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health 7: e000057. 10.1136/fmch-2018-000057.

- De Leo G, LeRouge C, Ceriani C, Niederman F 2006 Websites most frequently used by physician for gathering medical information. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings 2006, Washington, DC: 902.

- Depala N, Greene G 2016 Social media in physiotherapy undergraduate education: Who’s tweeting? Physiotherapy 102: e104. 10.1016/j.physio.2016.10.110.

- D’Souza F, Shah S, Oki O, Scrivens L, Guckian J 2021 Social media: Medical education’s double-edged sword. Future Healthcare Journal 8: e307–e310. 10.7861/fhj.2020-0164.

- Fahimi F 2018 Social media: An innovative and effective tool for educational and research purposes of the pharmaceutical and medical professionals. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 17: 801–803.

- Farsi D 2021 Social media and health care, Part I: Literature review of social media use by health care providers. Journal of Medical Internet Research 23: e23205. 10.2196/23205.

- Flynn L, Jalali A, Moreau K 2015 Learning theory and its application to the use of social media in medical education. Postgraduate Medical Journal 91: 556. 10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133358.

- Hayward L, Black L, Mostrom E, Jensen G, Ritzline P, Perkins J 2013 The first two years of practice: A longitudinal perspective on the learning and professional development of promising novice physical therapists. Physical Therapy 93: 369–383. 10.2522/ptj.20120214.

- Health Workforce Australia 2014 Australia’s health workforce series - physiotherapists in focus. https://www.health.gov.au/health-topics/health-workforce.

- Hennessy C, Smith C, Greener S, Ferns G 2019 Social media guidelines: A review for health professionals and faculty members. The Clinical Teacher 16: 442–447. 10.1111/tct.13033.

- Ignacimuthu L, Kumar M 2020 Theories of social media and learning: A study on the use of social media by undergraduate students. In: Nagarajan S Mohanasundaram R Eds, Innovations and technologies for soft skill development and learning, pp. 142–154. IGI Global. 10.4018/978-1-7998-3464-9.ch017.

- Ikenwilo D, Skåtun D 2014 Perceived need and barriers to continuing professional development among doctors. Health Policy 117: 195–202. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.04.006.

- Kapoor K, Tamilmani K, Rana P, Patil P, Dwivedi K, Nerur S 2018 Advances in social media research: Past, present and future. Information Systems Frontiers 20: 531–558. 10.1007/s10796-017-9810-y.

- Kind T, Genrich G, Sodhi A, Chretien K 2010 Social media policies at US medical schools. Medical Education Online 15: 5324. 10.3402/meo.v15i0.5324.

- Lao A, Wilesmith S, Forbes R 2022 Exploring the workplace mentorship needs of new graduate physiotherapists: A qualitative study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 38: 2160–2169. 10.1080/09593985.2021.1917023.

- Latkin C, Mai N, Ha T, Sripaipan T, Zelaya C, Le Minh N, Morales G, Go V 2016 Social desirability response bias and other factors that may influence self-reports of substance use and HIV risk behaviors: A qualitative study of drug users in Vietnam. AIDS Education and Prevention 28(5): 417–425. 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.5.417.

- Lave J, Wenger E 1991 Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leahy E, Chipchase L, Blackstock F 2017 Which learning activities enhance physiotherapy practice? A systematic review protocol of quantitative and qualitative studies. Systematic Reviews 6: 83. 10.1186/s13643-017-0475-x.

- Machete P, Turpin M 2020 The use of critical thinking to identify fake news: A systematic literature review. Responsible Design, Implementation and Use of Information and Communication Technology 12067: 235–246.

- Maloney S, Tunnecliff J, Morgan P, Gaida J, Clearihan L, Sadasivan S, Davies D, Ganesh S, Mohanty P, Weiner J, et al. 2015 Translating evidence into practice via social media: A mixed-methods study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 17: e242. 10.2196/jmir.4763.

- Marks A, McIntosh J 2006 Achieving meaningful learning in health information management students: The importance of professional experience. Health Information Management Journal 35: 14–22. 10.1177/183335830603500205.

- Mertes L 1991 Thinking and writing. Middle School Journal 22: 24–25. 10.1080/00940771.1991.11496002.

- Meyer K 2010 A comparison of Web 2.0 tools in a doctoral course. The Internet and Higher Education 13: 226–232. 10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.02.002.

- Milošević I, Živković D, Arsić S, Manasijević D 2015 Facebook as virtual classroom – social networking in learning and teaching among Serbian students. Telematics and Informatics 32: 576–585. 10.1016/j.tele.2015.02.003.

- Morosoli S, Van Aelst P, Humprecht E, Staender A, Esser F 2022 Identifying the drivers behind the dissemination of online misinformation: A study on political attitudes and individual characteristics in the context of engaging with misinformation on social media. American Behavioral Scientist: 000276422211183. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027642221118300.

- Naderifar M, Goli H, Ghaljaei F 2017 Snowball sampling: A purposeful method of sampling in qualitative research. Strides in Development of Medical Education 14: e67670. 10.5812/sdme.67670.

- Nagi-Watkins S, Carpenter C 2016 Undergraduate physiotherapists’ use of social media for learning: A qualitative exploration. Physiotherapy 102: e149. 10.1016/j.physio.2016.10.172.

- Novick G 2008 Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Research in Nursing and Health 31: 391–398. 10.1002/nur.20259.

- Oliver R, Herrington J 2000 Using situated learning as a design strategy for web-based learning. In: Abbey B (Ed) Instructional and cognitive impacts of web-based education, pp. 178–191. IGI Global.

- Panahi S, Watson J, Partridge H 2014 Social media and physicians: Exploring the benefits and challenges. Health Informatics Journal 22: 99–112. 10.1177/1460458214540907.

- Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer M 2014 The use of Facebook in medical education: A literature review. GMS Journal for Medical Education 31: 33.

- Pessoa A, Harper E, Santos I, Gracino M 2019 Using reflexive interviewing to foster deep understanding of research participants’ perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 1609406918825026. 10.1177/1609406918825026.

- Pettersson A, Bolander Laksov K, Fjellström M 2015 Physiotherapists’ stories about professional development. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 31: 396–402. 10.3109/09593985.2015.1024804.

- Pizzuti A, Patel K, McCreary E, Heil E, Bland C, Chinaeke E, Love B, Bookstaver B, Houwink EJF 2020 Healthcare practitioners’ views of social media as an educational resource. PLoS One 15: e0228372. 10.1371/journal.pone.0228372.

- Rose-Wiles L 2018 Reflections on fake news, librarians, and undergraduate research. Reference and User Services Quarterly 57: 200–204. 10.5860/rusq.57.3.6606.

- Scott N, Goode D 2020 The use of social media (some) as a learning tool in healthcare education: An integrative review of the literature. Nurse Education Today 87: 104357. 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104357.

- Stevens B, Wade D 2017 Improving continuing professional development opportunities for radiographers: A single centre evaluation. Radiography 23: 112–116. 10.1016/j.radi.2016.12.001.

- Stoikov S, Maxwell L, Butler J, Shardlow K, Gooding M, Kuys S 2022 The transition from physiotherapy student to new graduate: Are they prepared? Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 38: 101–111. 10.1080/09593985.2020.1744206.

- Sturges J, Hanrahan K 2004 Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: A research note. Qualitative Research 4: 107–118. 10.1177/1468794104041110.

- Sturman N, Tan Z, Turner J 2017 “A steep learning curve”: Junior doctor perspectives on the transition from medical student to the health-care workplace. BMC Medical Education 17: 92. 10.1186/s12909-017-0931-2.

- Thomas D 2006 A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation 27: 237–246. 10.1177/1098214005283748.

- Ventola C 2014 Social media and health care professionals: Benefits, risks, and best practices. Pharmacy and Therapeutics 39: 491–520.

- Wilkinson A, Ashcroft J 2019 Opportunities and obstacles for providing medical education through social media. JMIR Medical Education 5: e15297. 10.2196/15297.

- Zhao C, Pandian A, Singh M 2016 Instructional strategies for developing critical thinking in EFL classrooms. English Language Teaching 9: 14–21. 10.5539/elt.v9n10p14.

- Zou Y, Almond A, Forbes R 2021 Professional development needs and decision-making of new graduate physiotherapists within Australian private practice settings. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 39: 317–327. 10.1080/09593985.2021.2007559.