ABSTRACT

Background

Physiotherapy has the potential to benefit people with voice and throat problems in conjunction with existing services.

Purpose

This study aims to explore the impact and role of physiotherapy in voice and throat care, from the perspective of people who have accessed such care. Gaining a better understanding of how physiotherapy contributes to care has the potential to improve services.

Methods

An interpretive description design was used to explore participants perspectives of the impact and role of physiotherapy through individual semi-structured interviews with people who had accessed physiotherapy for voice or throat care through a single private practice. Transcripts were analyzed with a general inductive approach suitable for qualitative evaluation data. Data were analyzed from six interviews and four main themes emerged, with each theme further characterized by categories.

Results

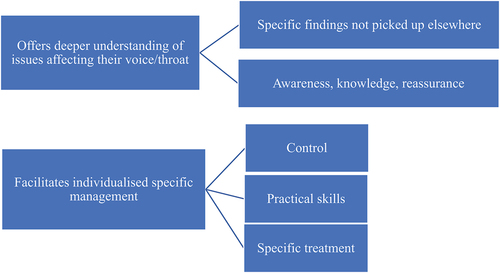

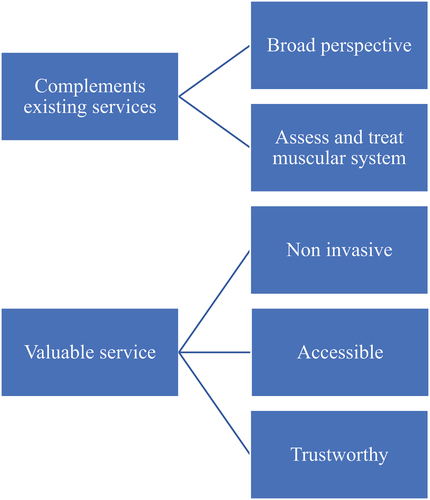

Two themes related to the impact of physiotherapy in voice and throat care: Offers a deeper understanding of issues affecting their voice/throat; facilitates individualized specific management. Two themes related to the role of physiotherapy in voice and throat care: Complements existing services; Valuable service. Each theme is further illustrated by categories.

Conclusion

This study indicates that physiotherapy for voice and throat problems can complement existing services while adding value, providing people with a deeper understanding of their problem and facilitating specific management. There is great potential for physiotherapy to benefit voice users. Future research should further evaluate the potential to include physiotherapy in the voice care team and consider how best to capture the broad impacts illustrated.

Introduction

Voice problems affect approximately one in every thirteen adults annually (Bhattacharyya, Citation2014). This can impair communication, which may have a significant impact on an individual’s quality of life, and ability to participate and work (Cohen, Dupont, and Courey, Citation2006; Roy et al., Citation2004). This is particularly pertinent for professional voice users, including singers, who, due to the intense and highly specific nature of their job are more likely to experience voice problems (Pestana, Vaz-Freitas, and Manso, Citation2017; Roy, Merrill, Gray, and Smith, Citation2005).

Physiotherapy has the potential to benefit people with voice and throat problems by contributing to care. Due to the large variation in etiology and contributing factors to voice and throat problems, management has traditionally involved a range of interventions, from multiple clinicians, such as an Otolaryngologist, or Ear Nose and Throat specialist (ENT), and a Speech Language Therapist (SLT). The role of the ENT is to assess and rule out the presence of lesions in the area and provide medical interventions if necessary. An SLT assesses voice parameters and laryngeal function and applies voice therapy to retrain vocal function. (Guzmán et al., Citation2016; Patterson et al., Citation2020; Van Houtte, Van Lierde, and Claeys, Citation2011; Watts et al., Citation2015) The role of physiotherapists in voice and throat management is relatively novel and underexplored. Research indicates that broader musculoskeletal conditions, such as cervicalgia, reduced neck range of motion, and postural changes commonly contribute to voice problems as well as localized changes in laryngeal muscle tone (Angsuwarangsee and Morrison, Citation2002; Menoncin et al., Citation2010; Murray et al., Citation2013). Physiotherapists can offer skills specific to posture and breathing pattern retraining, treatment of muscle tension and joint problems in the neck, shoulder, and thorax, as well as voice and throat specific manual therapy and massage techniques, to reduce laryngeal muscle tension (Cardoso, Lumini-Oliveira, and Meneses, Citation2019; D’Haeseleer, Claeys, and Van Lierde, Citation2013; Jahn, Citation2009; Johnson and Skinner, Citation2009; Mathieson, Citation2011; Pettersen and Westgaard, Citation2004; Roy et al., Citation2017; Staes et al., Citation2011; Ternström, Andersson, and Bergman, Citation2000; Tomlinson and Archer, Citation2015). Physiotherapy may therefore be a complimentary addition to traditional voice and throat management, using an approach that considers the role of structures external to the larynx.

Physiotherapy has been shown to benefit voice and throat problems through manual therapy (Mathieson, Citation2011; Tomlinson and Archer, Citation2015), exercise therapy (Lowell et al., Citation2022; Staes et al., Citation2011) and a combination of physiotherapy techniques (Cardoso, Meneses, and Lumini-Oliveira, Citation2017; Craig et al., Citation2015). Yet, the overall impact of physiotherapy management in the wider context of voice and throat care is unclear. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the impact and role of physiotherapy for voice and throat care from the perspectives of those who have accessed such care. This information will help illustrate the perspective of service users, with potential benefits for both voice users and health professionals involved in voice and throat care. This study has two objectives, 1. to explore the impact of voice physiotherapy, and 2. to explore the role of physiotherapy in voice and throat care. These objectives informed the evaluative design of the study.

Methods

Design

An interpretive description methodological approach (Thorne, Kirkham, and J, Citation1997) guided the study design. Interpretive description is a practice-based methodology that enables the experiences and views of individuals to be combined with clinical knowledge to inform clinical practice. (Thorne, Kirkham, and K, Citation2004) Ethical approval was given by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee H21/154 (see appendix). The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) were used to structure reporting of study methods and findings (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig, Citation2007).

Setting

The study was based in a small urban private practice physiotherapy clinic that operates from a medical center in Christchurch, New Zealand. Within this clinic, one physiotherapist (KH) offers care for people with voice and throat problems, including offering a traveling clinic that serves Wellington and Auckland patients on an intermittent basis (large urban centers). KH has experience working with voice and throat problems, including close mentoring from an experienced colleague and has completed a postgraduate certificate on “The Foundations of Voice, Physiotherapy for the Larynx and Voice” at Performance Medicine, Australia, prior to the study period. Patients can access the clinic directly, or via referral from SLTs, ENTs, or general practitioners. The clinic has supportive relationships with SLT, ENTs, and general practitioners to provide care to voice and throat patients.

Research team and reflexivity

KH is a female doctoral candidate and the physiotherapist who has treated the participants. She considers herself an insider with her expertise in voice and throat problems, and with professional relationships with the participants prior to the study commencing. EK is the primary supervisor to KH. He has more than ten years clinical experience and is an academic researcher with expertise primarily in musculoskeletal conditions. EK is a male and is an outsider to the field of voice and throat problems and had no prior relationship with the participants. To aid reflexivityEK and KH discussed their respective positioning both prior to and asinterviewsprogressed and debriefed after each interview, as well as keeping reflective notes. This was to acknowledge and mitigate potential preconceptions and assumptions around the topics explored that might influence data collection and inform the data analysis. Further regular research team meetings throughout data analysis also helped ensure rigor.

Participants and recruitment

All patients over 16 years old who accessed the voice and throat physiotherapy service, with (KH) within a calendar year period (October 01, 2020 to September 31, 2021)(were sent an e-mail inviting them to participate in a survey, as part of KH thesis research project, with basic demographic information and clinical characteristics. During this survey, they were given the option to voluntarily participate in a subsequent interview to discuss their experience with the service. This study reports data from participants who completed both the survey and subsequent interview.

Data collection

In the online survey, basic demographic information (age, gender, and ethnicity) and clinical characteristics (singer, presenting condition) were collected. All participants consenting to an interview were met either in-person or over video call. Interviews were facilitated by KH with support from EK following a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1). The guide comprised three primary questions stemming from the study objectives:

Can you please describe your experience of voice physiotherapy? (experience)

What impact did receiving voice physiotherapy have for you? (impact)

How would you describe voice physiotherapy to others? (role)

Semi-structured interviews were chosen to facilitate free flowing conversation to better understand the participant’s experience. Open questioning was used, and every effort made to ensure an open discussion around the broad objectives outlined. The interview guide was sent to the participants prior to commencing the interviews to provide them with an opportunity to consider their responses beforehand. Each interview was recorded and transcribed verbatim automatically on Zoom, and then the transcript was edited and corrected by KH for accuracy. The interviews lasted between 20 and 30 minutes. The transcripts were not sent to the participants to review for credibility following their interview as due to the nature of semi structured interviews, contradictions may occur, despite the transcripts being word for word of their interview (Thorne, Kirkham, and J, Citation1997). The interview transcripts and demographic data from the survey formed the data for subsequent analysis.

Data analysis

Interview data were analyzed for themes using a general inductive approach as described by Thomas (Citation2006). This involved the following procedures: (1) Data cleaning, where the automated zoom transcripts were cleaned and put into a consistent format by KH. (2) Close reading of the text, with multiple readings of the text by KH and EK, supporting familiarization with interview content and context. Textual analysis was informed by debriefings after each interview, and reflective notes taken during and post-interview. (3) Creation of categories derived from the text, then grouped under themes which were aligned with the evaluation aims. Using NVivo, KH identified the text segments with meaningful units and began creating categories and themes. Categories emerged from actual phrases or meanings from specific data text segments. Categories and themes were created, revised, and/or discarded through multiple iterations and repeated discussions between KH and EK, guided by the evaluation objectives. (4) Overlapping coding and uncoded text, where some text was coded into more than one theme, and some text not relevant to the evaluation objectives remained uncoded (Thomas, Citation2006). (5) Continuing revision and refinement of categories and themes. After a six-week stand down period, KH reexamined the thematic analysis to ensure satisfaction with the final themes. Themes were further refined during drafting of the study findings.

Results

Of the identified 52 individuals who were contacted, 11 completed the survey and seven indicated that they would be interested in participating in an interview. All seven were contacted, and six responded and participated in the interviews.

The six participants were all female. Three participants were aged between 20–30 years old, one 30–40 years, one 50–60 years, and one 70–80 years. Four were of New Zealand European ethnicity, one Māori, and one British. Four were singers, ranging from singing professionally to singing for leisure. Broadly, the presenting conditions of participants included muscular tension related issues (with or without the presence of a vocal fold lesion) oroveruse-related problems. All participants had seen at least one other health professional in their voice management journey, and most had seen multiple practitioners. This included ENT doctors, SLTs and in some cases a singing teacher or voice coach.

As shown in , the evaluative findings are organized into themes relating to the two study objectives, each further described by several categories. The figures are designed to present the main findings clearly, however, note themes and categories are not mutually exclusive and more interplay exists than is illustrated.

Figure 1. Themes (left) and categories (right) relating to the impact of physiotherapy in voice and throat care.

Figure 2. Themes (left) and categories (right) relating to the role of physiotherapy in voice and throat care.

Impact of physiotherapy in voice and throat care

Participant descriptions of the impact of voice physiotherapy can be described in two main themes: 1. Offers a deeper understanding of issues affecting the voice and throat; 2. Facilitates individualized and specific management. These two themes are closely related, as understanding affects management.

Physiotherapy offered participants a deeper understanding by recognizing findings not picked up elsewhere, such as muscular issues or postural alignment problems. This gave participants new information that they valued and could use to self-manage. Further, participants described gaining a greater awareness of their voice and knowledge about influencing factors. This was reassuring for participants and put them in a good position to assume greater control over their care.

I think it [physiotherapy] really addresses the cause of the issues, with the breathing and posture … she considered it all you know, overall, like my work, my job, what I did outside of work and health what I need my voice for, and … setting goals. P4

If I hadn’t met you, I wouldn’t have had that support … with the actual physical side of things, and the validation of like all this, a lot of tightness in these areas. P1

I’m more aware of my voice and I feel more able to manage certain things by myself. P1

Participants described physiotherapy as facilitating individualized, specific management in multiple ways, offering greater control, practical skills, and specific treatment. All six participants described gaining an ability to control their symptoms through techniques they had learnt in physiotherapy. This appeared to be closely related to learning practical skills that participants could use to self-manage.

If I’m feeling a bit of tightness, there are the exercises that you taught me that I can do, and that gives me that mental reassurance, and that gives me the physical release. P1

Because it’s physiotherapy, the first point of call is … to try a course of exercises or stretches first … So you’re not just fobbed off to, yet another practitioner. You’re given some practical, helpful, empowering, I suppose, tools. P6

I gained the ability to problem solve this in my own life. P2

Physiotherapy also offeredparticipantsspecific management of impairments, which included manual therapy and prescription of exercises that directly addressed musculoskeletal impairments affecting the voice and throat. This offered symptom relief and helped them understand and manage the problems they were dealing with.

One day I was with her [the physiotherapist] and my voice was wonky, and she did some massage around here and it [their voice] came back just like that P3

I’d go away from a session and then I would feel so much more relaxed and … vocally, everything was so much, so much easier … I could take the kind of tools that you’d given me, just in my normal week, and be able to, kind of reset where my voice was my sitting. P2

Role of physiotherapy in voice and throat care

Participants’ descriptions of the role of physiotherapy for voice and throat care aligned with two main themes: physiotherapy complements existing services, and it is a valuable service. These two themes closely relate, as part of what makes physiotherapy a valuable service is how it complements existing services in voice and throat care. Participants described physiotherapy as complementing existing services by offering a broad perspective that extended beyond the larynx and assessing and treating the muscular system.

That hands on is sort of like support … physio to me feels more of like a maintenance check in and spotting stuff before it becomes a problem. P1

Speech therapy is … fixed on the voice, one part of the body, but I think it’s[physiotherapy] a lot wider than that. P4

I think that it’s quite nice to go somewhere knowing, knowing that you’re going to get relief … whereas I suppose the ENT, like especially now that I’m quite down the journey of my voice treatment, often have no idea what to do with me. P5

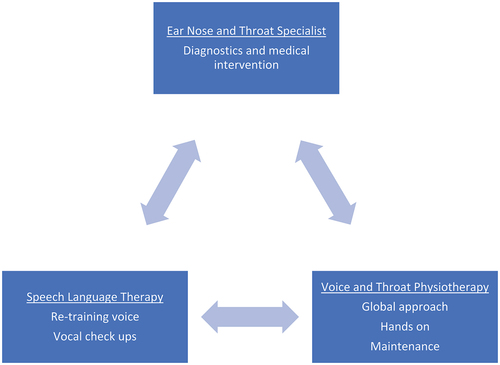

As all participants had seen at least one other health professional for their problem, they were well positioned to discuss the role of various professions in their care. Participants described each of the services in the voice care team playing a crucial role in their voice care experience, forming a triangle of services between ENT, SLT, and physiotherapy for voice and throat care ().

It’s this triangle, where they all inform each other, and you need to have all of corners of the triangle being strong. The ENT and the vocal scope is like that once a year, just to check in to make sure everything’s going okay, the physio is the in between, the yes this is tracking right or if something comes up … this is something that we can work on. The speech language therapist is if there’s maybe something very specific that sounds that I want to produce that I haven't done before, or … if I wanted to just get a check-up. P1

The ENT’S offer that medical side of what’s going to happen next for my vocal cords that aren’t working how they should … the SLT is more looking at, I think, how strong the vocal cords are getting. But the voice physio is keeping everything, I suppose, loose … so that the vocal cords can actually do what they’re supposed to do. I sort of need everyone- like I need the ENT’s I need the speech language therapist, but I need the voice physio as well, to help make everything work for me, I feel like it’s sort of a package. P5

Figure 3. Relative roles of health professionals in voice and throat care, as described by participants.

Participants also emphasized the value of physiotherapy in several ways. Having additional noninvasive options for voice and throat care was valued. Physiotherapy was described as an accessible and trustworthy type of care. This combination of factors suited an entry point for care, or as a place for more regular appointments.

It’s [physiotherapy] the more frequent check in that doesn’t exclude you with a really high price point like you get from vocal scope … it’s that bridge medically and mentally and physically and … also in the sense of accessibility, like a first step of feeling in safe hands. P1

I can feel relief from it and … it’s nice to have that relief, without anybody knocking me out, or anaesthetic in me. P5

Discussion

This qualitative study offers insights into the impact and role of physiotherapy in voice and throat care, from the perspective of people who have received such care. Interpretive description as a practice-based methodology enables integration of the qualitative data with clinical expertise, experience, and research to offer a descriptive analysis that informs clinical practice.

The impact of physiotherapy on people with voice and throat problems was broad, going beyond physical and functional benefits. The physical impacts are consistent with the findings of other studies, where techniques used by voice physiotherapists, such as laryngeal manual therapy (LMT), and techniques broadly utilized by physiotherapists, such as spinal manual therapy and exercise prescription have been shown to have positive impact on voice outcome measures and acoustic parameters (Cardoso, Lumini-Oliveira, and Meneses, Citation2019; Cardoso, Meneses, and Lumini-Oliveira, Citation2017; Lowell et al., Citation2022; Mathieson, Citation2011; Staes et al., Citation2011). The findings of this study highlight additional impact that are consistent with illness perceptions, in particular the dimensions of understanding and control (Broadbent, Petrie, Main, and Weinman, Citation2006). Illness perceptions are underpinned by the common sense model of self-regulation that describes how people respond to health threats (Leventhal, Phillips, and Burns, Citation2016). The control dimension divides into treatment control (how much the person thinks treatment can help their problem) and personal control (how much control the person feels they have over their problem), which are both apparent in the impact findings. This is not only relevant as a potentially unmeasured impact of physiotherapy, but there is also evidence for a strong link between functional voice disorders (e.g. muscle tension dysphonia) and psychological disorders (Andrea, Ó, Andrea, and Figueira, Citation2017; Willinger, Völkl-Kernstock, and Aschauer, Citation2005), in which illness perceptions may play a part. In this study participants described gaining understanding and control in several ways: locating and naming contributors to symptoms, especially through findings not picked up elsewhere; experiencing relief from specific treatment; and learning specific practical skills that helped them successfully manage their symptoms. This clearly indicates that the benefits of physiotherapy are not limited to physical relief and is consistent with the idea that giving patients tools to take an active role in their treatment appears to play a fundamental role in their care. (Coulter, Citation2012; Snyder and Engström, Citation2016) These broad impacts suggest physiotherapy might be valuable for people with a wide range of presentations, including those whose first port of voice care is voice physiotherapy and for people who have received ENT and SLT input. Future research should consider measuring the impact of care on illness perceptions, such as with the brief illness perceptions questionnaire (Broadbent, Petrie, Main, and Weinman, Citation2006).

This study helps illustrate a distinct role for physiotherapy in the care of voice and throat problems. Notably, physiotherapy was not seen to duplicate or compromise existing services, rather complementing, and adding value to care. The triangle of care articulated by participants () situates physiotherapy as complementing ENT care involving endoscopic evaluations and medical intervention, and SLT care using vocal parameters, air pressure, and contact quotient measures to assess and treat the voice mechanism (Guzmán et al., Citation2016; Patterson et al., Citation2020; Van Houtte, Van Lierde, and Claeys, Citation2011; Watts et al., Citation2015). These findings are consistent with the strengths of physiotherapy in identifying and managing muscle related problems, and wider contributing factors outside the larynx (Craig et al., Citation2015; Hockey and Kennedy, Citation2024). The broad/different perspective of physiotherapy enabled new findings and management opportunities. This feature aligns with recommendations for a combined approach to treatment of voice disorders, with results showing a combined approach provide better outcomes than that of a single treatment modality alone. (Gillivan-Murphy et al., Citation2006; Khatoonabadi et al., Citation2018; MacKenzie et al., Citation2001; Mansuri et al., Citation2019; Ruotsalainen et al., Citation2007; Ruotsalainen, Sellman, Lehto, and Verbeek, Citation2008; Sielska-Badurek et al., Citation2017). Ideally, the voice care service would include an ENT, SLT, and physiotherapist working together as a team.

Other characteristics of physiotherapy also contributed to a valued role.The non-invasive nature of physiotherapy was valued, offering further non-surgical management approaches. This may be especially relevant to people for whom surgery is inappropriate or unavailable, such as people with primary muscle tension dysphonia. (Van Houtte, Van Lierde, and Claeys, Citation2011) Then more practically, physiotherapy as a profession was described as accessible and trustworthy. This likely reflects the broad acceptance of physiotherapy services across the community; thus, physiotherapy was seen as approachable when applied to the voice. Supporting access, in New Zealand physiotherapists can be directly accessed without a referral. While those with expertise in voice care are few, physiotherapists more generally are easily accessed. For professional voice users and singers, physiotherapy appears to fill a space in between ENT and SLT services, and the singing coach/teacher. There are clear parallels with how physiotherapists work very closely with coaches and others in sporting contexts (Grant et al., Citation2014; Scott and Malcolm, Citation2015).

Strengths and limitations

This study was led by the treating physiotherapist, an insider in the field of voice and throat care. Insider research can offer a better understanding of the issues being studied due to established rapport, and through bringing their own knowledge and experiences to their research. (Bonner and Tolhurst, Citation2002) On the other hand, discussions may have been impacted by individuals' desire to protect or avoid discussion of any less positive impacts with their treating physiotherapist present. This, and the potential for participant views to be overshadowed by researcher views was acknowledged and mitigated through reflexivity, the steps outlined in the general inductive approach, and insider/outsider collaboration. Interviews were performed with a mentor present (EK), and participants were offered the opportunity for discussion without KH present. Participant views on the role of physiotherapy were strengthened by all having received care from at least one other voice professional prior to physiotherapy. Future studies should explore the nature of cases seen by ENT and SLTservicesto further clarify the potential role for physiotherapy within the established voice and throat care team.

Conclusion

This study offers a unique insight into the impact and role of physiotherapy for people with voice and throat problems. The impact of physiotherapy went beyond physical and functional benefits, improving people's understanding and control over their voice and throat problems. Physiotherapy complements and adds to existing services, with great potential to benefit voice users. Future research should further evaluate the potential to include physiotherapy in the voice care team and consider how best to capture the broad impacts illustrated.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrea M, Ó D, Andrea M, Figueira ML 2017 Functional voice disorders: The importance of the psychologist in clinical voice assessment. Journal of Voice 31: 13–22.

- Angsuwarangsee T, Morrison M 2002 Extrinsic laryngeal muscular tension in patients with voice disorders. Journal of Voice 16: 333–343.

- Bhattacharyya N 2014 The prevalence of voice problems among adults in the United States. The Laryngoscope 124: 2359–2362.

- Bonner A, Tolhurst G 2002 Insider-outsider perspectives of participant observation. Nurse Researcher 9: 7–19.

- Broadbent E, Petrie KJ, Main J, Weinman J 2006 The brief illness perception questionnaire. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 60: 631–637.

- Cardoso R, Lumini-Oliveira J, Meneses RF 2019 Associations between posture, voice, and dysphonia: A systematic review. Journal of Voice 33: 1–12.

- Cardoso R, Meneses RF, Lumini-Oliveira J 2017 The effectiveness of physiotherapy and complementary therapies on voice disorders: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Medicine 4: 45–45.

- Cohen SM, Dupont WD, Courey MS 2006 Quality-of-life impact of non-neoplastic voice disorders: A meta-analysis. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology 115: 128–134.

- Coulter A 2012 Patient engagement—what works? The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management 35: 80–89

- Craig J, Tomlinson C, Stevens K, Kotagal K, Fornadley J, Jacobson B, Garrett CG, Francis DO 2015 Combining voice therapy and physical therapy: A novel approach to treating muscle tension dysphonia. Journal of Communication Disorders 58: 169–178.

- D’Haeseleer E, Claeys S, Van Lierde K 2013 The effectiveness of manual circumlaryngeal therapy in future elite vocal performers. The Laryngoscope 123: 1937–1941

- Gillivan-Murphy P, Drinnan MJ, Tp O, Ridha H, Carding P 2006 The effectiveness of a voice treatment approach for teachers with self-reported voice problems. Journal of Voice 20: 423–431

- Grant M-E, Steffen K, Glasgow P, Phillips N, Booth L, Galligan M 2014 The role of sports physiotherapy at the London 2012 Olympic games. British Journal of Sports Medicine 48: 63–70.

- Guzmán M, Castro C, Madrid S, Olavarria C, Leiva M, Muñoz D, Jaramillo E, Laukkanen A-M 2016 Air pressure and contact quotient measures during different semioccluded postures in subjects with different voice conditions. Journal of Voice 30: 1–10

- Hockey K, Kennedy E 2024 Voice physiotherapy: Clinical characteristics of individuals presenting to physiotherapy for voice and throat care. Journal of Voice In Press 10.1016/j.jvoice.2024.01.007

- Jahn A 2009 Medical management of the professional singer: An overview. Medical Problems of Performing Artists 24: 3–9.

- Johnson G, Skinner M 2009 The demands of professional opera singing on cranio-cervical posture. European Spine Journal 18: 562–569.

- Khatoonabadi AR, Khoramshahi H, Khoddami SM, Dabirmoghaddam P, Ansari NN 2018 Patient-based assessment of effectiveness of voice therapy in vocal mass lesions with secondary muscle tension dysphonia. Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology 30: 131–137.

- Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E Burns E 2016 The common-sense model of self-regulation (CSM): A dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 39: 935–946.

- Lowell SY, Colton RH, Kelley RT, Auld M, Schmitz H 2022 Isolated and combined respiratory training for muscle tension dysphonia: Preliminary findings. Journal of Voice 36: 361–382.

- MacKenzie K, Millar A, Wilson JA, Sellars C, Deary IJ 2001 Is voice therapy an effective treatment for dysphonia? A randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal 323: 658.

- Mansuri B, Torabinezhad F, Jamshidi AA, Dabirmoghadam P, Vasaghi-Gharamaleki B, Ghelichi L 2019 Effects of voice therapy on vocal tract discomfort in muscle tension dysphonia. Iranian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology 31: 297–304.

- Mathieson L 2011 The evidence for laryngeal manual therapies in the treatment of muscle tension dysphonia. Current Opinion in Otolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery 19: 171–176.

- Menoncin LCM, Jurkiewicz AL, Silvério KCA, Camargo PM, Wolff NMM 2010 Alterações musculares e esqueléticas cervicais em mulheres disfônicas. Arquivos Internacionais de Otorrinolaringologia (Impresso) 14: 461–466

- Murray CJL, Abraham J, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bartels DH, Benjamin EJ, Birbeck G, Bolliger I, et al. 2013 The state of us health, 1990-2010: Burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. Journal of the American Medical Association 310: 591–608.

- Patterson JM, Govender R, Roe J, Clunie G, Murphy J, Brady G, Haines J, White A, Carding P 2020 COVID-19 and ENT SLT services, workforce and research in the UK: A discussion paper. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders 55: 806–817.

- Pestana PM, Vaz-Freitas S, Manso MC 2017 Prevalence of voice disorders in singers: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Voice 31: 722–727.

- Pettersen V, Westgaard R 2004 Muscle activity in professional classical singing: A study on muscles in the shoulder, neck and trunk. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology 29: 56–65.

- Roy N, Merrill RM, Gray SD, Smith EM 2005 Voice disorders in the general population: Prevalence, risk factors, and occupational impact. The Laryngoscope 115: 1988–1995.

- Roy N, Merrill Ray M, Thibeault S, Parsa Rahul A, Gray Steven D, Smith Elaine M 2004 Prevalence of voice disorders in teachers and the general population. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 47: 281–293.

- Roy N, Peterson EA, Pierce JL, Smith ME, Houtz DR 2017 Manual laryngeal reposturing as a primary approach for mutational falsetto. The Laryngoscope 127: 645–650.

- Ruotsalainen JH, Sellman J, Lehto L, Jauhiainen M, Verbeek JH 2007 Interventions for treating functional dysphonia in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010 138: CD006373–CD006373.

- Ruotsalainen J, Sellman J, Lehto L, Verbeek J 2008 Systematic review of the treatment of functional dysphonia and prevention of voice disorders. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery 138: 557–565.

- Scott A, Malcolm D 2015 ‘Involved in every step’: How working practices shape the influence of physiotherapists in elite sport. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 7: 539–556.

- Sielska-Badurek E, Osuch-Wójcikiewicz E, Sobol M, Kazanecka E, Rzepakowska A, Niemczyk K 2017 Combined functional voice therapy in singers with muscle tension dysphonia in singing. Journal of Voice 31: 23–31.

- Snyder H, Engström J 2016 The antecedents, forms and consequences of patient involvement: A narrative review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies 53: 351–378.

- Staes FF, Jansen L, Vilette A, Coveliers Y, Daniels K, Decoster W 2011 Physical therapy as a means to optimize posture and voice parameters in student classical singers: A case report. Journal of Voice 25: 91–101.

- Ternström S, Andersson M, Bergman U 2000 An effect of body massage on voice loudness and phonation frequency in reading. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology 25: 146–150.

- Thomas DR 2006 A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation 27: 237–246.

- Thorne S, Kirkham SR, J M-E 1997 Interpretive description: A noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Research in Nursing and Health 20: 169–177.

- Thorne S, Kirkham SR, K O-M 2004 The analytic challenge in interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 3: 1–11.

- Tomlinson CA, Archer KR 2015 Manual therapy and exercise to improve outcomes in patients with muscle tension dysphonia: A case series. Physical Therapy 95: 117–128.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J 2007 Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19: 349–357.

- Van Houtte E, Van Lierde K, Claeys S 2011 Pathophysiology and treatment of muscle tension dysphonia: A review of the current knowledge. Journal of Voice 25: 202–207.

- Watts CR, Diviney SS, Hamilton A, Toles L, Childs L, Mau T 2015 The effect of stretch-and-flow voice therapy on measures of vocal function and handicap. Journal of Voice 29: 191–199.

- Willinger U, Völkl-Kernstock S, Aschauer HN 2005 Marked depression and anxiety in patients with functional dysphonia. Psychiatry Research 134: 85–91.

Appendix One

Semi structured interview framework

Introduction

Thank you for participating in the survey and for agreeing to participate in this interview today. Do you have any questions about the research, for example, from the information sheet? Are you happy for this interview to be recorded?

If you have anything that you’d like to say but don’t feel comfortable sharing with me, just let me know at the end of the interview and we can organize a phone call with Ewan privately, or you can speak to him at the end.

Setting the scene:

I’m just going to read out a few things to set the scene before we get started.

Voice physiotherapy is a new service in New Zealand. We look forward to hearing about your experience with voice physiotherapy and any impact this service might have had for you. The purpose of collecting this data is to clarify the role of physiotherapy for voice and to improve quality of care.

This research forms part of (my) Kristina’s Masters research via the University of Otago. We are interviewing people like yourself who have accessed this service to better understand the impact of voice physiotherapy.

Do you have any questions so far?

In order to keep the transcript as clean as possible, I’m going to stay quieter than I usually do and react less, in order that we can have your thoughts and views as much as possible.

Experience

We are really interested in your overall experience with voice physiotherapy.

Would you like to start by describing your experience of voice physiotherapy?

Prompts for deeper discussion might include:

What led to you seeking voice physiotherapy?

Was there a part of physiotherapy that was most helpful? Least helpful?

What might have improved your experience?

Anything else you'd like to say on that

Section 2:

Impact

Let’s talk more about how this service has impacted you.

What impact did receiving voice physiotherapy have for you?

Prompts for deeper insight:

Impact might include effects of physiotherapy – for example effects on your voice, effects on your ability to participate in activities, and effects on your wellbeing.

To what extent did the issues you presented with resolve?

Were there any short-term impacts?

Were there any long-term impacts?

Anything else you’d like to add

Part 3:

Service provision

We’re interested in your perspective of voice physiotherapy as a health service.

How would you describe voice physiotherapy to others?

Further prompts for discussion

- Are there changes we should consider making to the service?

- Would you recommend voice physiotherapy to others?

- Is there anything about physiotherapy that was different from professions.

Wrapping up

Thanks so much for taking the time to share your views with us, we really appreciate your perspective.

Do you have anything further you would like to add?

Is there anything you’d like to say to Ewan without me present?

When we have completed these we will be able to share some information with you. Would you like to receive:

A copy of the interview transcript? Yes No

A preliminary analysis of the combined interview findings? Yes No