ABSTRACT

Introduction

The relationship between psychosocial factors and bodily pain in people with knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is unclear.

Purpose

To examine whether widespread pain was associated with poorer self-efficacy, more anxiety, depression, and kinesiophobia in people with KOA.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional study based on data from Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D®). The association between widespread pain (multiple pain sites) and self-efficacy (Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale), anxiety and depression (item from the EQ-5D-5 L), and kinesiophobia (yes/no) was examined using multiple linear tobit or logistic regression models.

Results

Among 19,323 participants, 10% had no widespread pain, 37% had 2 pain sites, 26% had 3–4 pain sites, and 27% had ≥5 pain sites. Widespread pain was associated with poorer self-efficacy (−0.9 to −8.3 points), and the association was stronger with increasing number of pain sites (p-value <.001). Significant increasing odds ratios (ORs) were observed for having anxiety or depression with 3–4 pain sites (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.12; 1.49) and ≥5 pain sites (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.56; 2.07). Having 2 and 3–4 pain sites were associated with lower odds of kinesiophobia compared to having no widespread pain.

Conclusion

Widespread pain was associated with lower self-efficacy and more anxiety and depression but also lower kinesiophobia in people with KOA.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the leading causes of musculoskeletal pain and disability worldwide (GBD, Citation2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, 2020). At a global level, 595 million people have OA (GBD, Citation2021 Osteoarthritis Collaborators, 2023) and the prevalence increases with age; 14% of adults aged 25 and older have clinical OA, while the prevalence is 34% among adults age 65 and older (Neogi, Citation2013). KOA is the most common type of OA and a major cause of pain and functional limitations (Ma, Chan, and Carruthers, Citation2014; Neogi, Citation2013).

Most individuals with KOA have pain as their main complaint (Leyland et al., Citation2012). However, there is high variability both in the intensity and spreading of pain as well as in its natural history in patients with KOA (Chang et al., Citation2023). Moreover, despite the attempt to identify specific pain phenotypes among patients with KOA, these phenotypes still require validation (Neelapala et al., Citation2023). For most patients with KOA, pain remains stable, a significant proportion worsen while a few improve over time (Nicholls et al., Citation2014). KOA has previously been demonstrated to be associated with later development of widespread pain (Carlesso et al., Citation2017) and widespread pain is associated with poorer physical and mental health (Lacey et al., Citation2014). It seems that psychosocial factors are not associated with the severity of the disease (Alaca, Citation2019); however, they may partly explain the variability in the intensity and spreading of pain in patients with KOA (Lluch Girbes et al., Citation2016; Somers, Keefe, Godiwala, and Hoyler, Citation2009). Indeed, the potential role of (maladaptive) psychosocial factors (i.e. catastrophization, kinesiophobia) in the individual pain experience of people with KOA has been discussed in the scientific literature (Rayahin et al., Citation2014; Urquhart et al., Citation2015). Individuals with KOA have shown psychological impairments related to pain coping, self-efficacy, somatizing, pain catastrophising, and helplessness (Briani et al., Citation2018; Lentz et al., Citation2020; Urquhart et al., Citation2015). In addition, a positive relationship has been demonstrated between the presence of maladaptive psychosocial factors (e.g. catastrophizing) and knee pain intensity in people with KOA (Urquhart et al., Citation2015). Psychological factors have been shown to have a key role in the development of persistent pain and disability and in treatment outcomes (Linton and Shaw, Citation2011). Interestingly, a recent systematic review highlighted the important role that psychosocial factors have in predicting recovery after total knee replacement (Bay et al., Citation2018). In particular, the presence of catastrophic thinking and poor coping strategies at baseline (i.e. before surgery) was associated with higher levels of pain after knee replacement surgery (Baert et al., Citation2016). In line with all the abovementioned studies, clinical practice guidelines currently advise clinicians to perform a comprehensive assessment of psychosocial factors in people with KOA (Bannuru et al., Citation2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines, Citation2022). However, uncertainty exists around the best psychological screening and assessment methods for this population (Kittelson, Stevens-Lapsley, and Schmiege, Citation2016).

The association of psychosocial factors with the spreading of pain to multiple body sites in people with musculoskeletal pain has been investigated in recent literature. For instance, higher levels of depression and lower levels of self-efficacy were found to be associated with more areas of bodily pain in some painful musculoskeletal conditions (Falla et al., Citation2016; Hayashi et al., Citation2015). However, the literature on this topic is still scarce and a definitive answer on the relationship between psychosocial factors and bodily pain areas in people with chronic musculoskeletal pain including people with KOA is still not available (Reis et al., Citation2019). Knowledge of such relationship would be important in order to inform clinical practice as to whether a more in-depth psychological assessment should be done in those with widespread pain.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine whether having widespread pain (two or more bodily pain sites) was associated with lower self-efficacy, and more anxiety, depression, and kinesiophobia in people with KOA.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study based on data from the registry-based cohort study Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA:D®) registry. This study used data that were collected prospectively in the GLA:D® registry. GLA:D® is a nationwide implementation initiative aimed at implementing supervised exercise therapy and patient education according to international knee and hip OA guidelines into clinical practice (Skou and Roos, Citation2017). In this study, only baseline data were included and the study was reported according to the STROBE statement for cross-sectional studies (Von Elm et al., Citation2007).

Participants

Participants with complete data on exposure (widespread pain), outcomes (self-efficacy, anxiety and depression, and kinesiophobia), and covariates (age, sex, educational level, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, pain intensity, and physical activity level) from April 2014 (introduction of pain mannequin to assess bodily pain sites) until 10th of April 2018 were included.

The inclusion criteria for participation in the GLA:D® program is having “joint problems from the knee that have resulted in contact with the health care system” (Skou and Roos, Citation2017). Physiotherapists trained specifically in the clinical diagnosis of hip and/or knee OA evaluated the eligibility criteria. Radiographs are not needed to diagnose OA according to international guidelines (Sakellariou et al., Citation2017) and therefore not part of the eligibility criteria for being included in GLA:D®18. However, 89% self-reported having radiographically confirmed OA. Participants are excluded from GLA:D® participation if they have another reason than OA for the knee joint problems such as tumor or an inflammatory joint disease, other symptoms that are more pronounced than the knee problems (e.g. chronic, generalized pain, or fibromyalgia) (Skou and Roos, Citation2017), or do not understand Danish.

Ethical approval for the GLA:D® program was not needed, according to the local ethics committee of the North Denmark Region (Skou and Roos, Citation2017). The GLA:D® program was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The GLA:D® registry has been approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (SDU; 10.084). Before study participation, participants were informed about the data registration in GLA:D®. According to the Danish Data Protection Act, patient consent was not required as personal data were processed exclusively for research and statistical purposes.

Data collection procedure

Data were registered in the national electronic GLA:D® registry. The registry is designed to record the characteristics of the patients participating in the GLA:D® program at baseline and evaluate outcomes immediately after the program (approx. 3 months) and at 12 months of follow-up. In the current study, baseline data were retrospectively extracted and used for analysis.

Variables

Demographic characteristics (covariates)

Age, sex, cohabitant, educational level, BMI, presence of comorbidities, pain medication, pain intensity, and physical activity level were collected at baseline. Previous literature has supported the importance of these variables on the intensity and spreading of bodily pain (Calders and Van Ginckel, Citation2018; Mørup-Petersen et al., Citation2021; Muckelt et al., Citation2020).

Widespread pain (exposure)

Widespread pain was defined as at least two bodily pain sites using a pain mannequin, where patients marked areas of the body where they had experienced pain for the last 24 hours. Pain mannequins have previously been used to obtain a graphical representation of bodily pain distribution in people with KOA (Arendt-Nielsen et al., Citation2010, Citation2015; Coggon et al., Citation2013; Creamer, Lethbridge-Cejku, and Hochberg, Citation1998; Sengupta et al., Citation2006; Skou et al., Citation2013; Wood, Peat, Thomas, and Duncan, Citation2007; Thompson et al., Citation2009).

The pain mannequin consisted of a total of 56 pain sites (26 on the front of the body and 30 on the back). The total number of marked pain sites was calculated and then categorized into four categories (no widespread pain (0–1 pain sites), 2 pain sites, 3–4 pain sites, and ≥5 pain sites) (Supplements – ).

Outcomes

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was assessed using the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Scale (ASES). The scale ranges from 10 (very uncertain) to 100 (very certain) – How certain the patient is that he/she can manage the arthritis symptoms (Lorig et al., Citation1989). In GLA:D®, the subscales self-efficacy for managing pain (pain self-efficacy) and self-efficacy for controlling other symptoms (other self-efficacy) were collected.

ASES is a widely used self-report measure of beliefs evaluating confidence in one’s capacity to function despite pain and control of either pain or other symptoms related to OA. ASES has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure of self-efficacy in patients with KOA (Lorig et al., Citation1989).

Anxiety and depression

Anxiety and depression were assessed using one item from the self-reported EuroQol 5-Dimension 5-Level questionnaire (EQ-5D-5 L) with the following response categories: 1) I am not anxious or depressed, 2) I am slightly anxious or depressed, 3) I am moderately anxious or depressed, 4) I am severely anxious or depressed, and 5) I am extremely anxious or depressed (EuroQoL Group, Citation1990). For the present study, a binary variable was created distinguishing whether participants had experienced anxiety or depression (response options 2–5) or not. The EQ-5D-5 L is a reliable and valid generic instrument used to assess health status which can be applied to a broad range of populations (Bilbao et al., Citation2018).

Kinesiophobia

Fear of movement was assessed using a yes/no question: “Are you afraid that your joints will be damaged from physical activity and exercise?” with the responses: Yes/No. This variable has been previously used in studies in people with chronic musculoskeletal pain (Lundberg, Grimby-Ekman, Verbunt, and Simmonds, Citation2011; Luque-Suarez, Martinez-Calderon, and Falla, Citation2019).

Statistical analyses

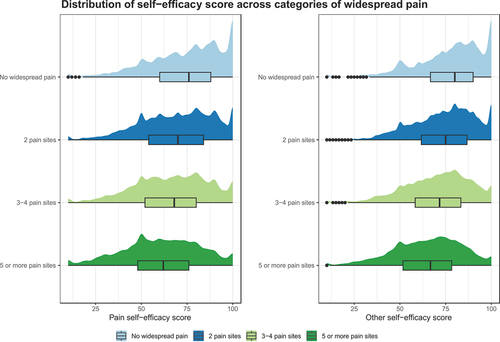

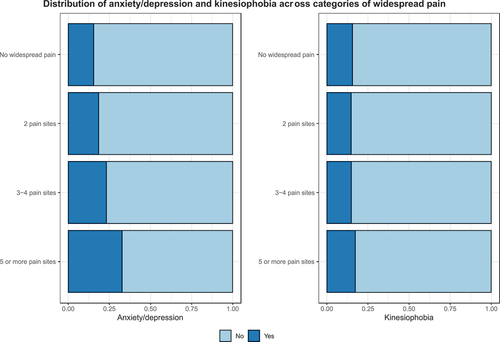

Cross-tabulations were conducted to describe characteristics among participants across categories of widespread pain (no widespread pain, 2 pain sites, 3–4 pain sites, and ≥5 pain sites) and were summarized as numbers, proportions, median, and interquartile range (IQR). Further, half-density-plots were performed to present the distribution of self-efficacy scores across categories of widespread pain, while bar charts were performed to present the distribution of anxiety or depression and kinesiophobia across categories of widespread pain.

The cross-sectional association between widespread pain (in categories) and self-efficacy was examined using a multiple linear tobit regression due to a floor and ceiling effect of the pain self-efficacy and other self-efficacy scores. Furthermore, multiple logistic regression models were performed to examine the association between widespread pain and anxiety or depression and kinesiophobia. In addition, tests for trends in outcomes across categories of widespread pain were conducted (Royston, Citation2014). All models were adjusted for age, sex, educational level, BMI, comorbidities, pain intensity, and physical activity, which were suggested a priori to be potential biasing paths between the exposure and outcomes according to the directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) (Supplements – ). Strength of the associations was reported with ß coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for tobit regression models representing mean difference in self-efficcacy in categories of widespread pain with no chronic pain as the reference. For logistic regression models, strength of the associations was reported with odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CI representing ORs of having anxiety or depression and kinesiophobia in categories of widespread pain with no chronic pain as reference. Both crude and multivariable adjusted models were conducted and presented.

Figure 2. Distribution of experiencing anxiety/depression and kinesiophobia (No/Yes) across categories of widespread pain presented with bar charts. No widespread pain equals 0–1 pain sites.

All statistical analyses were performed in STATA/BE 17.0 and R statistical (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) software version 4.2.2 (10th of November 2022), RStudio (RStudio Inc., Boston, MA, USA) version 2022.07.2 using an α-level of 0.05 two-sided.

Results

Of 19,323 participants included, 1,972 (10%) had no widespread pain, 7,186 (37%) had 2 pain sites, 5,042 (26%) had 3–4 pain sites, and 5,123 (27%) had ≥5 pain sites. Participants with ≥5 pain sites were more often female, more obese, had more comorbidities, higher medication intake, and experienced more intense knee/hip pain ().

Table 1. Participant characteristics in categories of widespread pain.

Better self-efficacy scores were observed among participants with no widespread pain or few pain sites (). The prevalence of experiencing anxiety or depression was highest among participants with ≥5 pain sites, and the prevalence of experiencing kinesiophobia was equally distributed across categories of widespread pain ().

Having widespread pain was associated with worse pain self-efficacy and other self-efficacy both in the crude and adjusted analysis. This association was stronger with increasing number of pain sites (p-value <.001). Having 2 pain sites, 3–4 pain sites, and ≥5 pain sites were significantly associated with worse pain self-efficacy (2 pain sites: −2.1 points, 95% CI −3.0; −1.1, 3–4 pain sites: −4.3 points, 95% CI −5.3; −3.3, and ≥5 pain sites: −8.3 points, 95% CI −9.3; −7.3) and worse other self-efficacy score (2 pain sites: −0.9 points, 95% CI −1.8; −0.1, 3–4 pain sites: −4.3 points, 95% CI −4.1; −2.4, and ≥5 pain sites: −6.9 points, 95% CI −7.8; −5.9) after adjustments compared to having no widespread pain ().

Table 2. Linear regression on the association between categories of widespread pain and self-efficacy.

The crude analysis showed that having 2 pain sites, 3–4 pain sites, and ≥5 pain sites were significantly associated with increased odds of experiencing anxiety or depression compared to having no widespread pain. In the adjusted analysis, increasing odds ratios were observed for having anxiety or depression with increasing number of pain sites. This association was statistically significant for 3–4 pain sites and ≥5 pain sites ().

Table 3. Logistic regression on the association between categories of widespread pain and anxiety and depression.

The adjusted analyses between categories of widespread pain and kinesiophobia revealed that having 2 pain sites and 3–4 pain sites were significantly associated with lower odds of experiencing kinesiophobia compared to having no widespread pain ().

Table 4. Logistic regression on the association between categories of widespread pain and kinesiophobia.

Discussion

The main finding of this study was that having widespread pain was significantly associated with worse self-efficacy, with a stronger association with more pain sites, and with having anxiety and depression, with increased odds with more pain sites. Also, having widespread pain was associated with decreased odds of experiencing kinesiophobia compared to having no widespread pain.

Psychosocial factors have been postulated to be related to widespread pain reported by patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain of different etiologies (Reis et al., Citation2019). Although psychosocial and sociodemographic factors may be important determinants of pain levels reported by patients with KOA (Eberly et al., Citation2018), the relationship between widespread pain and psychosocial factors in people with KOA is not clear. Patients with KOA may have psychological impairments related to coping, self-efficacy, somatizing, pain catastrophizing, and helplessness (Lentz et al., Citation2020; Urquhart et al., Citation2015). Some of these psychosocial variables, such as pain catastrophizing, high level of depression, anxiety, or pain-related fear of movement, have been suggested as negatively influencing KOA-related pain and disability (Baert et al., Citation2016; Somers, Keefe, Godiwala, and Hoyler, Citation2009) and may also be related to chronic postoperative pain in patients receiving total knee arthroplasty (Fernández-de-Las- PeñPeñAs et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, postoperative pain catastrophizing and pain attitudes have recently been shown to be independent predictors for chronic postsurgical pain after total knee arthroplasty (Terradas-Monllor, Ruiz, and Ochandorena-Acha, Citation2024). Multiple psychological factors have been associated with the development of pain and disability in the long term in people with KOA (Helminen et al., Citation2016). A recent study by Helminen, Arokoski, Selander, and Sinikallio (Citation2020) concluded that variables such as anxiety, pain-related cognitions, and psychological resources may predict symptoms in the long term in this population. This study adds to the existing literature suggesting that widespread pain is associated with worse self-efficacy scores, anxiety and depression, and less kinesiophobia in patients with KOA.

Previous studies investigating the association between widespread pain and psychosocial factors in people with KOA have showed contradictory results. Thompson et al. (Citation2009) found positive correlations between enlarged areas of pain and anxiety, whereas Lluch, Torres, Nijs, and Van Oosterwijck (Citation2014) did not find any association between widespread pain, anxiety, and catastrophizing. Further, a systematic review by Carnes, Ashby, and Underwood (Citation2006) concluded that the assumption that widespread pain in unselected populations with musculoskeletal pain indicates disturbed psychological state is not supported by available evidence. According to Luque-Suarez et al. (Citation2022), widespread pain was associated with pain intensity. However, widespread pain was not associated with any psychological measure nor with pain-related disability. Similarly, in a more recent systematic review, Reis et al. (Citation2019) found that only depression has a weak relation with widespread pain in chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions. In neither systematic reviews, authors found compelling evidence to support the use of pain mannequins as a screening tool to help clinicians to identify patients who might benefit from a more in-depth psychological assessment. In contrast, it was found that widespread pain assessed by a pain mannequin was associated with lower self-efficacy and more anxiety and depression in the current study. Because there is no gold standard for pain drawings recording and analysis, an important aspect that may contribute to the divergence of findings is the different scoring systems used to record and analyze widespread pain such as a computer analysis (Barbero et al., Citation2015) or a region-divided body chart. Furthermore, different psychosocial variables were taken into consideration and there were some variations in the populations included. In this study, it was observed that patients with widespread pain had lower odds of having kinesiophobia. However, this should be interpreted with caution and likely reflect a chance finding as there appears to be no logic causal explanation to this finding. The result could also stem from using only one question with yes/no answer or because the participants that were willing to take part in exercise therapy had less fear of movement. As such, it might be interpreted as a lack of relation between widespread pain and kinesiophobia in patients with KOA.

This is an analysis using large-scale, real-world data from patients with KOA treated in primary care with important clinical implications. This is an analysis using large-scale, real-world data from patients with KOA treated in primary care with important clinical implications. As patients with KOA and widespread pain were found more likely to also have maladaptive psychosocial factors, the presence of widespread pain may prompt clinicians to a more in-depth assessment of psychosocial factors. In addition, physiotherapists often lack confidence and ability in identifying psychosocial factors and this recognition task is time demanding (Henning and Smith, Citation2023; Stearns, Carvalho, Beneciuk, and Lentz, Citation2021). However, screening for widespread pain using a simple body chart might be less time demanding and easier to apply in clinical practice on a general level. Previous studies have already shown that psychosocial factors may influence outcomes and recovery after total knee replacement surgery (Bay et al., Citation2018; Edwards et al., Citation2009; Feeney, Citation2004; Giesinger, Kuster, Behrend, and Giesinger, Citation2013; Goubert, Crombez, and Van Damme, Citation2004). In addition, results from randomized, controlled trials suggest that total knee replacement and non-surgical treatments such as exercise therapy and education have a positive effect on number of bodily pain sites and pain sensitization (Skou et al., Citation2016a; Skou et al., Citation2016b). Indeed, number of pain sites/enlarged areas of pain are associated with sensitization (Lluch Girbes et al., Citation2016). Whether this change in number of bodily pain sites from surgical treatment also leads to changes in psychosocial factors in patients with KOA treated in primary care would be important to investigate in future research.

Some important limitations should be acknowledged in this study. First, the study design was cross-sectional, so any conclusions on causal relationships between the variables are precluded. Thus, conclusions about, e.g., the predictive role of widespread pain in people with KOA pain cannot be drawn. Second, the broad eligibility criteria might have resulted in the inclusion of patients that did not have KOA. However, the physiotherapists were specifically trained in the clinical diagnosis of KOA and differential diagnoses. Third, in contrast with other studies, where more sophisticated methods to measure the area of pain were implemented (e.g. by using computer analysis (Barbero et al., Citation2015; Reis et al., Citation2014)), a self-reported region-divided body chart was used to measure widespread pain in the current study. More elaborated and highly developed methods to record pain extension have been used to explore the relationship between pain area and psychosocial factors in people with chronic musculoskeletal pain (Barbero et al., Citation2015; Reis et al., Citation2014). However, this approach is easier to apply in clinical practice. Harmonizing measurement methods of pain areas could help advance the understanding of how the distribution of pain in different regions of the body occurs (Øverås et al., Citation2021). Another limitation was the way widespread pain was measured. It can be long-lasting; however, it was registered just for the last 24 hours, so it is not possible to be sure if the pain was long-lasting or not. Regarding depression and anxiety, EQ-5D-5 L was used to measure both variables. Although the validity of single items from this instrument has not been investigated and therefore may not measure this construct adequately, it has been done several times before in a similar population (Garval et al., Citation2023; Judge et al., Citation2012; Sanchez-Santos et al., Citation2018).

Finally, although we identified statistically significant associations between widespread pain and psychosocial factors, the clinical relevance of some of the between-group differences can be questioned, including the surprising association between widespread pain and lower odds of kinesiophobia.

In conclusion, it was found that widespread pain assessed by the number of bodily pain sites was significantly associated with worse self-efficacy, increased odds of having anxiety or depression, but not higher odds of experiencing kinesiophobia in people with KOA. Further research on the impact of widespread pain on treatment outcome and the interplay with psychosocial factors is needed. Also, understanding the potential mechanisms underlying the association between widespread pain and psychosocial factors in patients with KOA could be interesting for future research.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (272.5 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all participating patients, physiotherapists reporting data to the GLA:D®-registry, and others involved in GLA:D®.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2024.2372381.

Disclosure statement

The authors, STS and EMR, are the co-founders of GLA:D® which is a non-profit initiative hosted at University of Southern Denmark aimed at implementing clinical guidelines for OA in clinical practice. Furthermore, STS has received personal fees from Munksgaard, TrustMe-Ed, and Nestlé Health Science outside the submitted work. EMR is the copyright holder of Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) and several other patient-reported outcome measures.The authors report no other potential conflict of interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alaca N 2019 The relationships between pain beliefs and kinesiophobia and clinical parameters in Turkish patients with chronic knee osteoarthritis: A cross-sectional study. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 69: 823–827.

- Arendt-Nielsen L, Egsgaard LL, Petersen KK, Eskehave TN, Graven-Nielsen T, Hoeck HC, Simonsen O 2015 A mechanism-based pain sensitivity index to characterize knee osteoarthritis patients with different disease stages and pain levels. European Journal of Pain 19: 1406–1417.

- Arendt-Nielsen L, Nie H, Laursen MB, Laursen BS, Madeleine P, Simonsen OH, Graven-Nielsen T 2010 Sensitization in patients with painful knee osteoarthritis. Pain 149: 573–581.

- Baert IA, Lluch E, Mulder T, Nijs J, Noten S, Meeus M 2016 Does pre-surgical central modulation of pain influence outcome after total knee replacement? A systematic review. A Systematic Review Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 24: 213–223.

- Bannuru RR, Osani MC, Vaysbrot EE, Arden NK, Bennell K, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA, Kraus VB, Lohmander LS, Abbott JH, Bhandari M, et al. 2019 McAlindon TE 2019 OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 27: 1578–1589.

- Barbero M, Moresi F, Leoni D, Gatti R, Egloff M, Falla D 2015 Test–retest reliability of pain extent and pain location using a novel method for pain drawing analysis. European Journal of Pain 19: 1129–1138.

- Bay S, Kuster L, McLean N, Byrnes M, Kuster MS 2018 A systematic review of psychological interventions in total hip and knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 19: 201.

- Bilbao A, Garcia-Perez L, Arenaza JC, Garcia I, Ariza-Cardiel G, Trujillo-Martin E, Forjaz MJ, Martín-Fernández J 2018 Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D- 5L in patients with hip or knee osteoarthritis: Reliability, validity and responsiveness. Quality of Life Research 27: 2897–2908.

- Briani RV, Ferreira AS, Pazzinatto MF, Pappas E, De Oliveira Silva D, Azevedo FM 2018 What interventions can improve quality of life or psychosocial factors of individuals with knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review with meta-analysis of primary outcomes from randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Sports Medicine 52: 1031–1038.

- Calders P, Van Ginckel A 2018 Presence of comorbidities and prognosis of clinical symptoms in knee and/or hip osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 47: 805–813.

- Carlesso LC, Segal NA, Curtis JR, Wise BL, Frey Law L, Nevitt M, Neogi T 2017 Knee pain and structural damage as risk factors for incident widespread pain: Data from the multicenter osteoarthritis study. Arthritis Care and Research 69: 826–832.

- Carnes D, Ashby D, Underwood M 2006 A systematic review of pain drawing literature: Should pain drawings be used for psychologic screening? The Clinical Journal of Pain 22: 449–457.

- Chang AH, Almagor O, Lee J, Song J, Muhammad LN, Chmiel JS, Moisio KC, Sharma L 2023 The natural history of knee osteoarthritis pain experience and risk profiles. The Journal of Pain 24: 2175–2185.

- Coggon D, Ntani G, Palmer KT, Felli VE, Harari R, Barrero LH, Felknor SA, Gimeno D, Cattrell A, Vargas-Prada S, et al. 2013 Patterns of multisite pain and associations with risk factors. Pain 154: 1769–1777.

- Creamer P, Lethbridge-Cejku M, Hochberg MC 1998 Where does it hurt? Pain localization in osteoarthritis of the knee. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 6: 318–323.

- Eberly L, Richter D, Comerci G, Ocksrider J, Mercer D, Mlady G, Wascher D, Schenzk R 2018 Psychosocial and demographic factors influencing pain scores of patients with knee osteoarthritis. Public Library of Science One 13: e0195075.

- Edwards RR, Haythornthwaite JA, Smith MT, Klick B, Katz JN 2009 Catastrophizing and depressive symptoms as prospective predictors of outcomes following total knee replacement. Pain Research and Management 14: 307–311.

- EuroQoL Group 1990 EuroQoL – a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 16: 199–208.

- Falla D, Peolsson A, Peterson G, Ludvigsson ML, Soldini E, Schneebeli A, Barbero M 2016 Perceived pain extent is associated with disability, depression and self-efficacy in individuals with whiplash-associated disorders. European Journal of Pain 20: 1490–1501.

- Feeney SL 2004 The relationship between pain and negative affect in older adults: Anxiety as a predictor of pain. Journal of Anxiety Disorders 18: 733–744.

- Fernández-de-Las- PeñPeñAs C, Florencio LL, de-la-Llave-Rincón AI, Ortega-Santiago R, Cigarán-Méndez M, Fuensalida-Novo S, Plaza-Manzano G, Arendt-Nielsen L, Valera-Calero JA, Navarro-Santana MJ 2023 Prognostic factors for postoperative chronic pain after knee or hip replacement in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: An Umbrella review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 12: 6624.

- Garval M, Runge C, Holm CF, Mikkelsen LR, Pedersen AR, Vestergaard TAB, Skou ST 2023 Prognostic factors of knee pain and function 12 months after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective cohort study of 798 patients. The Knee 44: 201–210.

- GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators 2020 Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990 – 2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396: 1204–1222.

- GBD 2021 Osteoarthritis collaborators 2023 articles global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990 – 2020 and projections to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatology 5: e508–e522.

- Giesinger JM, Kuster MS, Behrend H, Giesinger K 2013 Association of psychological status and patient-reported physical outcome measures in joint arthroplasty: A lack of divergent validity. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 11: 64.

- Goubert L, Crombez G, Van Damme S 2004 The role of neuroticism, pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear in vigilance to pain: A structural equations approach. Pain 107: 234–241.

- Hayashi K, Arai YC, Morimoto A, Aono S, Yoshimoto T, Nishihara M, Osuga T, Inoue S, Ushida T 2015 Associations between pain drawing and psychological characteristics of different body region pains. Pain Practice 15: 300–307.

- Helminen E-E, Arokoski JP, Selander TA, Sinikallio SH 2020 Multiple psychological factors predict pain and disability among community-dwelling knee osteoarthritis patients: A five-year prospective study. Clinical Rehabilitation 34: 404–415.

- Helminen EE, Sinikallio SH, Valjakka AL, VäVäIsänenänen-Rouvali RH, Arokoski JP 2016 Determinants of pain and functioning in knee osteoarthritis: A one-year prospective study. Clinical Rehabilitation 30: 890–900.

- Henning M, Smith M 2023 The ability of physiotherapists to identify psychosocial factors in patients with musculoskeletal pain: A scoping review. Musculoskeletal Care 21: 502–515.

- Judge A, Arden NK, Cooper C, Kassim Javaid M, Carr AJ, Field RE, Dieppe PA 2012 Predictors of outcomes of total knee replacement surgery. Rheumatology 51: 1804–1813.

- Kittelson AJ, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Schmiege SJ 2016 Determination of pain phenotypes in knee osteoarthritis: A latent class analysis using data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Arthritis Care and Research 68: 612–620.

- Lacey RJ, Belcher J, Rathod T, Wilkie R, Thomas E, McBeth J 2014 Pain at multiple body sites and health-related quality of life in older adults: Results from the north Staffordshire osteoarthritis project. Rheumatology 53: 2071–2079.

- Lentz TA, George SZ, Manickas-Hill O, Malay MR, O’Donnell J, Jayakumar P, Jiranek W, Mather RC 2020 What general and pain-associated psychological distress phenotypes exist among patients with hip and knee osteoarthritis? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 478: 2768–2783.

- Leyland KM, Hart DJ, Javaid MK, Judge A, Kiran A, Soni A, Goulston LM, Cooper C, Spector TD, Arden NK 2012 The natural history of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: A fourteen-year population-based cohort study. Arthritis and Rheumatism 64: 2243–2251.

- Linton SJ, Shaw WS 2011 Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain. Physical Therapy 91: 700–711.

- Lluch E, Torres R, Nijs J, Van Oosterwijck J 2014 Evidence for central sensitization in patients with osteoarthritis pain: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Pain 18: 1367–1375.

- Lluch Girbes E, Duenas L, Barbero M, Falla D, Baert I, Meeus M, Sánchez-Frutos J, Aguilella L, Nijs J 2016 Expanded distribution of pain as a sign of central sensitization in individuals with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Physical Therapy 96: 1196–1207.

- Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman HR 1989 Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatology 32: 37–44.

- Lundberg M, Grimby-Ekman A, Verbunt J, Simmonds MJ 2011 Pain-related fear: A critical review of the related measures. Pain Research and Treatment 2011: 1–26.

- Luque-Suarez A, Falla D, Barbero M, Pineda-Galan C, Marco D, Giuffrida V, Martinez-Calderon J 2022 Digital pain extent is associated with pain intensity but not with pain-related cognitions and disability in people with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 23: 727.

- Luque-Suarez A, Martinez-Calderon J, Falla D 2019 Role of kinesiophobia on pain, disability and quality of life in people suffering from chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review. British Journal of Sports Medicine 53: 554–559.

- Ma VY, Chan L, Carruthers KJ 2014 The incidence, prevalence, costs and impact on disability of common conditions requiring rehabilitation in the us: Stroke, spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, multiple sclerosis, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, limb loss, and back pain. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 95: 986–995.

- Mørup-Petersen A, Skou ST, Holm CE, Holm PM, Varnum C, Krogsgaard MR, Laursen M, Odgaard A 2021 Measurement properties of UCLA Activity Scale for hip and knee arthroplasty patients and translation and cultural adaptation into Danish. Acta Orthopaedica 92: 681–688.

- Muckelt PE, Roos E, Stokes M, McDonough S, Grønne D, Ewings S, Skou ST 2020 Comorbidities and their link with individual health status: A cross-sectional analysis of 23,892 people with knee and hip osteoarthritis from primary care. Journal of Comorbidity 10: 2235042X20920456.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines 2022 Osteoarthritis in over 16s: Diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).

- Neelapala Y, Neogi T, Kumar D, Jarraya M, Frey-Law L, Lewis C, Nevitt M, Kobsar D, Macedo L, Hanna S, et al. 2023 Exploring pain phenotypes in people with early knee osteoarthritis: The multicenter osteoarthritis study (most). Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 31: 707–708.

- Neogi T 2013 The epidemiology and impact of pain in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 21: 1145–1153.

- Nicholls E, Thomas E, Van Der Windt DA, Croft PR, Peat G 2014 Pain trajectory groups in persons with, or at high risk of, knee osteoarthritis: Findings from the knee clinical assessment study and the osteoarthritis initiative. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 22: 2041–2050.

- Øverås CK, Johansson MS, de Campos TF, Ferreira ML, Natvig B, Mork PJ, Hartvigsen J 2021 Distribution and prevalence of musculoskeletal pain co-occurring with persistent low back pain: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 22: 91.

- Rayahin JE, Chmiel JS, Hayes KW, Almagor O, Belisle L, Chang AH, Moisio K, Zhang Y, Sharma L 2014 Factors associated with pain experience outcome in knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care and Research 66: 1828–1835.

- Reis F, Guimaraes F, Nogueira LC, Meziat-Filho N, Sanchez TA, Wideman T 2019 Association between pain drawing and psychological factors in musculoskeletal chronic pain: A systematic review. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 35: 533–542.

- Reis FJ, De Barros E, Silva V, De Lucena RN, Mendes Cardoso BA, Nogueira LC 2014 Measuring the pain área: An intra and inter-rater reliability study using image analysis software. Pain Practice 16: 24–30.

- Royston P 2014 PTREND: Stata module for trend analysis for proportions. Statistical Software Components. Boston College Department of Economics. https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s426101.htm

- Sakellariou G, Conaghan PG, Zhang W, Bijlsma JWJ, Boyesen P, D´agostino MA, Doherty M, Fodor D, Kloppenburg M, Miese F, et al. 2017 EULAR recommendations for the use of imaging in the clinical management of peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 76: 1484–1494.

- Sanchez-Santos MT, Garriga C, Judge A, Batra RN, Price AJ, Liddle AD, Javaid MK, Cooper C, Murray DW, Arden NK 2018 Development and validation of a clinical prediction model for patient-reported pain and function after primary total knee replacement surgery. Scientific Reports 8: 3381.

- Sengupta M, Zhang YQ, Niu JB, Guermazi A, Grigorian M, Gale D, Felson DT, Hunter DJ 2006 High signal in knee osteophytes is not associ- ated with knee pain. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 14: 413–417.

- Skou ST, Graven-Nielsen T, Rasmussen S, Simonsen OH, Laursen MB, Arendt-Nielsen L 2013 Widespread sensitization in patients with chronic pain after revision total knee arthroplasty. Pain 154: 1588–1594.

- Skou ST, Roos EM 2017 Good Life with osteoArthritis in Denmark (GLA: D™): Evidence-based education and supervised neuromuscular exercise delivered by certified physiotherapists nationwide. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorderers 18: 72.

- Skou ST, Roos EM, Simonsen O, Laursen MB, Rathleff MS, Arendt-Nielsen L, Rasmussen S 2016a The effects of total knee replacement and non-surgical treatment on pain sensitization and clinical pain. European Journal of Pain 20: 1612–1621.

- Skou ST, Roos EM, Simonsen O, Laursen MB, Rathleff MS, Arendt-Nielsen L, Rasmussen S 2016b The efficacy of non-surgical treatment on pain and sensitization in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A pre-defined ancillary analysis from a randomized controlled trial. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 24: 108–116.

- Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Godiwala N, Hoyler GH 2009 Psychosocial factors and the pain experience of osteoarthritis patients: New findings and new directions. Current Opinion in Rheumatology 21: 501–506.

- Stearns ZR, Carvalho ML, Beneciuk JM, Lentz TA 2021 Screening for yellow flags in orthopaedic physical therapy: A clinical framework. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 51: 459–469.

- Terradas-Monllor M, Ruiz MA, Ochandorena-Acha M 2024 Postoperative psychological predictors for chronic postsurgical pain after a knee arthroplasty: A prospective observational study. Physical Therapy 104: 41.

- Thompson LR, Boudreau R, Hannon MJ 2009 Osteoarthritis initiative investigators. The knee pain map: Reliability of a method to identify knee pain location and pattern. Arthritis & Rheumatism 61: 725–731.

- Urquhart DM, Phyomaung PP, Dubowitz J, Fernando S, Wluka AE, Raajmaakers P, Wang Y, Cicuttini FM 2015 Are cognitive and behavioural factors associated with knee pain? a systematic review. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 44: 445–455.

- Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP 2007 The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ: British Medical Journal 335: 806–808.

- Wood LR, Peat G, Thomas E, Duncan R 2007 Knee osteoarthritis in community-dwelling older adults: Are there characteristic patterns of pain location? Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 15: 615–623.