?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Milieu protection areas (MPAs) are a frequently used urban policy regulation method in large German cities such as Berlin or Munich. MPAs protect residents from displacement by restricting property rights in designated zones through limitations on modernisation and the conversion of rental apartments into condominiums. Policymakers expect this to have a price-dampening effect and slow gentrification while also anticipating corresponding effects on property markets. This study investigates the long-term empirical effects of these restrictions on the Berlin residential property market and examines how milieu protection affected the purchase prices and transactions of condominiums within Berlin’s MPAs and their surroundings. We relate transaction data from 1991 to 2019 with other neighbourhood characteristics, regress prices, and the number of transactions using geographic information systems and regression difference-in-differences models in different spatial submarkets both inside and outside of the MPAs. Results indicate that milieu protection reduces transaction activity in property markets and regulation has been ineffective in curbing price increases. Meanwhile, limitations on the conversion of former rental flats have led to lower price increases compared to the surrounding areas. This study contributes to the understanding of regulation as a potential determinant of supply and price effects in the property market.

Introduction

Many European cities have experienced significant population growth in recent years, leading to an increase in rents and purchase prices and thus to concerns about the displacement of residents. In many cities, public law instruments are used to regulate housing stock to protect the population from displacement (e. g., Levy et al., Citation2007; Lloyd, Citation2016).

In Germany, regulations to protect socially vulnerable residents have been in place for many years. A ‘Building Land Mobilization Act’ (‘Baulandmobilisierungsgesetz’) has recently tightened these regulations significantly in tense housing markets, where the conversion of rental apartments into condominiums is restricted and municipalities are granted the right to buy first when the owner wants to sell their property. Large parts of this law are inspired by an existing regulation in the German building code BauGB (1960), in which these properties are referred to as ‘social preservation areas’ or more commonly ‘milieu protection areas (MPAs)’.

Individual neighbourhoods can be designated as MPAs to protect residents from displacement to counteract gentrification tendencies. The state hopes to limit rent increases and property prices for the local residential population in order to decelerate displacement (Mitschang, Citation2017, pp. 51–52). Milieu protection allows authorities to limit the modernisation of apartments through installing elevators and terraces, or merging two housing units (Eckardt, Citation2021, p. 30; Walser, Citation2018, p. 192). It applies to all condominiums (including rented condominiums) or other owner-occupied units. This has a long-term negative impact on the condition of properties within MPAs and is intended to deter investors. Since 2015, Berlin has required permits for the conversion of existing rental apartments into condominiums or other owner-occupied units in MPAs. The aim is to protect lower-income populations from displacement during conversions, and possibly, the subsequent sale of properties. Moreover, the municipality (in the case of Berlin, the district) is granted the right to buy properties first within MPAs, if it is for sale. This is often accompanied by a so-called avoidance agreement: If the investor or buyer does not want the municipality to use the right of buying first, they commit themselves to further restrictions, such as refraining from energetic renovation measures, or additions such as balconies or elevators.

In urban discourse, the effectiveness of MPAs against gentrification is controversial (Eckardt, Citation2021, p. 30; Walser, Citation2018, p. 193). Regulations on milieu protection were incorporated into German building laws as early as 1977. In the mid-1990s, however, they were first systematically implemented in the districts of Berlin (Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen Berlin [SensW], Citation2021).

A rather unusual aspect is their spatial designation: Municipalities define parcel-specific areas in which MPA regulations apply. MPAs are comparable to zoning decisions in the US, where zoning districts set specific regulations for several purposes. This results in blocks of houses within MPAs facing homes outside MPAs just opposite them on the same street. This makes MPAs an interesting research subject because it allows comparable areas with and without regulation to be assessed. Before designation, an assessment is usually made at the request of the municipality regarding two issues: whether the conservation objectives apply to the area and whether the conditions for designation are met. The assessment focuses on the criteria for upgrading potential and demand as well as displacement risk.

A requirement for the designation of an MPA is the construction of lower-quality housing with potential for upgrades, which would displace vulnerable populations in the process. To measure this, household surveys are conducted within the areas. These surveys are methodologically questionable because households indirectly evaluate their own displacement risk and are therefore biased. MPAs are observed via annual monitoring, in which changes in housing conversions and rents are analysed descriptively. In theory, the MPA can be revoked and ended after five years; in practice, they mostly remain in place for much longer. The oldest existing MPAs at the time of this study, Luisenstadt and Graefestraße, have been in place since 1995.

While the local government of Berlin monitors rental prices, there is currently little empirical evidence of its impact on property markets. This monitoring only notes that a price increase observed in all building age segments has increased the number of conversions from rental apartments to condominiums in recent years. They conclude that the MPAs are effective, as conversions to condominiums have recently declined again (Nelle et al., Citation2021, pp. 64–65, 111). However, interventions in property markets often have undesirable side effects that are not anticipated by policymakers. Thus, there has been no empirical impact analysis on the property market for milieu protection in Germany or any comparable regulations internationally. Thus, a related question arises for property markets: Does regulation in MPAs affect transaction activity and prices in the property market?

Most contributions generally observe price increases and lower supply elasticity as an effect of government regulations (Gyourko & Molloy, Citation2015, p. 1316). However, modernisation constraints also reduce attractiveness and thus have opposite effects. Our contribution adds to the understanding of the effects of government regulatory interventions on the property market. This will allow evidence-based recommendations to accompany the introduction of similar interventions in equally tense housing markets, for example, the discussed transfer of milieu protection regulation to the United States of America by Walser (Citation2018).

The focus of our study is twofold: (1) how do condominium markets in MPAs compare to surrounding areas and (2) what is the quantifiable impact of milieu protection regulations on condominium prices and the number of transactions. To isolate and separate MPAs from other characteristics, we use geographic information systems (GIS) and regression difference-in-differences (DID) models in various spatial submarkets both inside and outside the MPAs. The regulations in the MPAs cover all residential properties. We focus on condominiums because they accounted for over 81% of apartment transactions over the period under review and are more directly linked to the rental housing market in Germany, as they are frequently used as rental properties after purchase.Footnote1

Literature review

The description of the phenomenon of gentrification varies, but it usually describes the transformation of a low-income neighbourhood to one that is no longer considered low-income (Watt, Citation2009). This transformation often creates displacement pressures where low-income residents are forced out of their homes and neighbourhoods. This can happen either directly through the demolition of flats, evictions by landlords, and rent increases, or indirectly through the loss of neighbourhood resources (see, Atkinson, Citation2000; Watt, Citation2009 for a further discussion).

Regulations [like MPAs] seek to counter these displacement pressures by limiting the quantity of new housing or increasing the costs associated with development, which reduces the potential supply of housing (Leguizamon & Christafore, Citation2021, p. 995). A body of research has examined the effects of regulation on the price and quantity of housing. The vast majority of these studies suggest that the average price of housing increases as supply is constrained (refer to Gyourko & Molloy, Citation2015, pp. 1316–1322, for an overview of numerous studies). Land-use regulations can increase the attractiveness of an area, thus increasing the demand for housing in such areas while further limiting the supply (Quigley & Rosenthal, Citation2005, p. 69). The price of a high level of regulation is thus lower housing affordability for residents (Leguizamon & Christafore, Citation2021, p. 1011). In this context, Kahn et al. (Citation2010) examined the impact of land use regulations on house prices, housing supply and gentrification patterns in the Californian coastal boundary zones (CBZ). They compared areas with land-use regulations with nearby areas without such regulations and found that they led to higher house prices (adjusted for quality) but a greater supply of housing. The regulations increased the attractiveness to such an extent that the demand effects had more than compensated for the supply-dampening effects. According to the authors, the introduction of CBZs also had a positive impact on gentrification in the affected areas . This result is relevant for the study of the possible impacts of MPAs, as both focus on spatial regulatory boundaries in the same local community. However, demand-side development differs in one important respect: while attractiveness is increasing in CBZs, regulations of MPAs aim to lower it (e.g. by preventing redevelopment). Leguizamon and Christafore (Citation2021) identify that regulations do not have to increase the attractiveness of a particular place uniformly across the neighbourhood concerned. While attractiveness may be increased in areas with already high-income households, the costs of renovating or converting lower-income neighbourhoods may also be driven up, limiting the potential for these areas to experience gentrification. Leguizamon and Christafore (Citation2021) measured this in an experiment that analysed the relationship of house prices with the probability of a neighbourhood’s gentrification. In contrast to previous conclusions, higher levels of regulation were associated with almost 10% higher increases in overall house prices – the likelihood of gentrification occurring in a lower income area was nevertheless three to four percentage points lower than in less regulated counterparts.

However, not all regulations have the same effect, as regulations come in many forms. Jackson (Citation2016) shows in a study of California cities that each land use regulation reduces permits for housing by an average of more than 6%. Zoning and general controls are the strongest barriers to development. The author further argues that not all regulatory actions harm the housing supply, stating that regulations that are classified as population controls (e.g. population growth limits) do not significantly impact development activity in the housing market (Jackson, Citation2016, p. 54). In many research studies, price premiums have been even higher, with an observed effect ranging from 10% (Mayer & Somerville, Citation2000) to 22% (Malpezzi, Citation1996). Particularly in urban areas where land prices represent a large share of the total costs, higher regulation is associated with higher prices (Kok et al., Citation2014, p. 146).

Research also indicates that the elasticity of the housing supply in the property market decreases with increasing regulation. Increases in housing and labour demand lead to greater increases in house prices and less construction activity in areas with stricter limits on the housing supply (Hilber & Vermeulen, Citation2016; Saks, Citation2008). While this is confirmed to theoretical models (Helsley & Strange, Citation1995), empirical studies show inconsistent indications. Davidoff (Citation2013) could not find empirical support for the assumption that supply constraints affect housing price volatility in an empirical study of the U.S. housing cycle of the 2000s. In an analysis of English municipalities by Hilber and Vermeulen (Citation2016), regulatory restrictions had a significant positive effect on the elasticity of the housing price-to-income ratio, which significantly increased housing price volatility, particularly in urban areas. Milieu protection regulations are, in essence, property growth controls because they limit, in effect, the number of marketable properties. They result in the marginal cost of housing being infinite beyond a certain point because the total number of housing transactions is limited (Gyourko & Molloy, Citation2015, p. 1316). Somerville et al. (Citation2020) find that, for similar regulations, acquisition restrictions have a small effect on housing prices in China, but they cause a substantial 40% decline in housing market activity in the short run, which tapers off over time.

While much of the literature indicates that regulatory interventions generally cause higher house prices and lower supply, restricting renovation activity may mitigate further price appreciation. As renovations improve residential properties by optimising their profitability, home prices rise. In particular, renovations in more modest neighbourhoods (such as MPAs) can lead to an increase in property values throughout the district (Charles, Citation2013, p. 1520). The location factor, precisely, appears to play a decisive role in adding value through the refurbishment of real estate (Dye & McMillen, Citation2007). Restrictions on renovations in the meantime hinder the improvement of the standard of housing in the area, thus, milieu protection is seen as an effective means of combating ‘luxury gentrification’ by some gentrification researchers (Riemann, Citation2016; Vogelpohl & Buchholz, Citation2017). However, higher housing prices do not necessarily result in higher neighbourhood gentrification. For example, if regulations restrict the ability of developers and households to renovate the existing housing stock and build new housing, this reduces the likelihood that a relatively low-income neighbourhood will experience gentrification because of the limited ability to increase its attractiveness (Leguizamon & Christafore, Citation2021, p. 1011). The conversion of rental apartments into condominiums may also be accompanied by the direct displacement of former residents. In their work on displacement causes in Berlin, Beran et al. (Citation2019) found several negative effects of terminations on displacement due to owner-occupancy or housing modernisation.

In German literature on gentrification, there is considerable interest in evaluating the effectiveness of MPAs in securing affordable housing, although empirical research is lacking. Becker (Citation1994) considers milieu protection as a powerful instrument for protecting affordable housing and thus emphasises its property as an instrument for preventing gentrification. Vogelpohl (Citation2013) also classifies MPAs as a means of curbing rising rents, tied to three conditions: (1) The early enactment of such areas, (2) the strict interpretation of the permit requirements, and (3) the area-wide use within a city. Riemann (Citation2016) supports this view from a legal perspective but also notes in this context that these conditions often express themselves as the actual limits.

Geßner (Citation2008) concludes that long-term milieu protection in the sense of protecting the existing resident population is only possible in areas that have previously undergone extensive upgradingFootnote2. However, such a combination would hardly prevent gentrification since it essentially supports displacement processes. Although new residents were protected effectively, the population composition existing before the start of development was acutely threatened by displacement. Such an approach would also therefore contradict the fundamental objectives of milieu protection (Mitschang, Citation2017).

Empirical studies have also been published on the effects of urban development interventions and regulations such as urban renewal areas or heritage conservation areas on prices, which positively affect property values (Ahlfeldt et al., Citation2017; Nesset & Oust, Citation2019; Oba & Noonan, Citation2017; Zahirovic-Herbert & Chatterjee, Citation2012).

Based on the empirical literature, we assume that regulation by the MPA has a threefold effect on the supply of residential properties in the market. First, the supply of condominiums within MPAs diminishes because converting rental apartments or non-residential units into condominiums is prohibited. Many renovation projects (e.g. a new bathroom or balcony) are subject to permit restrictions, which further limits the marketability of some apartments. Furthermore, owners who sell their apartments may fear that the state will use its right to buy first and force the owners to comply with certain obligations (e.g. limiting renovations). However, the increase in demand (analogous to the aforementioned study results of Kahn et al. (Citation2010)) due to attractiveness gains could compensate for this effect. In the case of housing prices, the empirical literature further finds that regulations cause prices to rise (not to be confused with a higher displacement rate). Moreover, a special feature in the MPAs is the prohibition of some measures to increase attractiveness (e.g. renovation); however, the extent to which these regulations influence the price formation, as well as individual components of the properties, remains unknown.

Data sources and study area

The study area is in Berlin and the instrument`s importance for Berlin can already be seen in the area covered: While approximately 4% of the city area is designated as an MPA, approximately 787.000 of the 3.8 mil. residents lived in MPAs in 2020. In Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, a popular district in Berlin, 40% of the area is designated as an MPA. Because tenant ratios are particularly high in MPAs (92% in 2019 compared to 82% in the rest of the study area), there is (theoretically) higher risk of displacement due to sharp rent increases in recent years, especially if the proprietor takes advantage of rent growth potentials.

We analyse data from the Expert Committees for Property Values (‘Gutachterausschuss für Grundstückswerte Berlin’), which provides a dataset for the MPAs with all condominium transactions since 1991. In this collection of prices, all contracts for the sale of real estate property of a municipality are recorded. The entry in the purchase price collection is made when the buyer and seller have already agreed on a contract. This is of great advantage, as the actual prices of the transactions are reflected, unlike the real estate listings on real estate portals. The committee also captures relevant characteristics of the properties. At the time of data collection in 2019, 59 MPAs existed in Berlin. Our control group of the surrounding areas includes all transactions in the 37 local districts (the next-smallest unit of analysis after city districts) that are located within a 500 m radius of the MPAs.

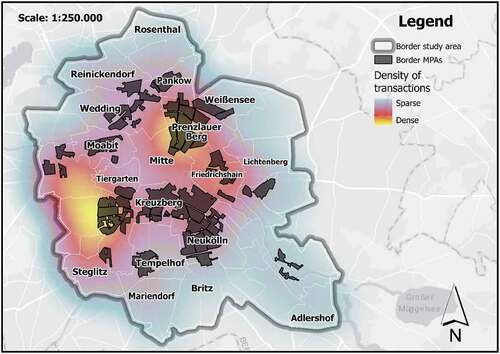

The dataset includes 229,369 data records on condominium transactions in the study area from 1991 to 2019. Among these, 26,675 transactions are within MPAs at the time of transaction (see, for borders of the MPAs). All transactions have a time stamp, which we compare with the respective MPA’s enactment time that is also available. If a transaction is considered to be both spatially within an MPA and temporally completed after the enactment of the regulation, it is counted as a transaction in the MPA. The transactions mostly involve private individuals; among buyers, 95% were private individuals, both in MPAs and outside. Among the sellers, approximately 40% are private individuals and 50% are companies; public-sector actors play only a minor role. The original price data contains 96 different attributes. The position accuracy corresponds to the block level, which in the vast majority, contain up to 1,000 residents with an average size of five hectares. The block allocation contains the greatest possible geographical accuracy while the anonymity of the transactions remains preserved. The allocation of the transactions to the MPAs is thus possible without any problems due to the block-wise boundaries of these.

Figure 1. Study area: Milieu protection areas in Berlin 2020 and heat map of available transaction data 1991–2019.

The transactions do not contain information on every characteristic of the property. For this reason, the data set had to be cleaned up accordingly. The number of cases examined is therefore reduced to 221,703 transactions. Only condominium transactions with block allocation, area details, and the contract type ‘purchase and offer/acceptance’ (e.g. no foreclosure) were considered. There are also implausible transactions in the present data set that deviate significantly from the usual transactions for reasons that cannot be verified (presumably personal circumstances or similar) and are therefore treated as outliers. In our dataset, transactions with purchase prices below €1,200/sqm and above €7,000/sqm (greater than or less than two times the standard deviation) are excluded. This further applies to buildings built before 1870, condominiums with living areas below 30 sqm and above 150 sqm, and special building types (e.g. vacation homes). In the corrected data set, the average purchase price outside of the MPAs was €161,667.71 (€2,125.16 per sqm); in the MPAs, this price was slightly higher at €213,758.24 (€2,876.57 per sqm). The average size of the condominiums was 72.99 sqm, in MPAs it was 73.24 sqm. Complete descriptive statistics on the transactions are described in of the appendices, and the variables used to estimate the regression DID model are described in detail in of the appendices.

Important attributes that are available in full include: purchase agreement date, seller and buyer group (e.g. private individual, company, state), floor space, purchase price, or statistical block number. We localise the transactions using a GIS to enrich additional location variables that are important for the regression DID model (Gröbel & Thomschke, Citation2018; Herath & Maier, Citation2013) and to explore implicit spatial relationships. The polycentric structure of Berlin poses a challenge for the price-relevant centrality and neighbourhood characteristic measurements. Location effects are therefore also simulated by measuring the travel time by public transport to the main station and the nearest university. In addition to the inclusion of the local district, a kernel-smoothed density of bars, pubs, nightclubs, and hotels existing in 2019 is mapped for the centrality measure. The search radius of 848.7 m used in the density calculation corresponds to the weighted standard distance around the geographical centre of the area.

Materials and methods

The objective is to isolate the effect of regulations in MPAs in condominium transactions. To achieve this objective, we use a modified regression DiD model for (a) the number of transactions to measure transaction activity and (b) purchase prices. One advantage of using a regression DID model is that it is easy to add and control for additional covariates in this framework (Angrist & Pischke, Citation2009, p. 176).

The dataset contains records indicating whether the transaction took place in an area that was an MPA at the exact date of the transaction. This allows us to measure spatial and temporal characteristics that arise due to the MPAs being established at different points in time, rather than all at once. Thus, transactions in the same area can belong to the treatment group if they happen after the establishment of an MPA, or the control group if the transaction happened before the establishment of an MPA. The third possible case, transactions of properties that were previously within MPAs but are not anymore, is not reflected in our data since, to the best of our knowledge, there is no comprehensive record showing the revocation dates of MPAs. This strategy follows similar approaches that use spatial and temporal factors to accurately determine the treatment and control groups (Linden & Rockoff, Citation2008; Pope, Citation2008; Turnbull et al., Citation2019).The model, therefore, takes the form

where is the vector of either logarithmised transaction prices or number of transactions for properties;

is a constant;

is a vector of coefficients for characteristics j;

is a matrix of property characteristics (e.g. floor space, elevator, balcony, and so on), as well as temporal (transaction year) and spatial characteristics (local district, proximity to amenities) j for transactions i;

is the coefficient for variable

;

is a vector that, for each transaction i, takes the value 1 if the transaction occurred in an area and at a time where and when an MPA regulation was in effect, and 0 otherwise;

is a vector of coefficients for the interaction between property characteristics and MPA; and

is the interaction between property characteristics and MPA. It should be noted that the model for the analysis of the number of transactions does not include characteristics of the condominiums themselves as the calculations are performed on the aggregated block level, not on the level of individual properties.

Statistically significant interaction effects would indicate that the respective transaction characteristics are valued differently for condominiums located in MPAs compared to those outside of MPAs. These differences can then be compared with policy objectives to assess the efficacy of MPAs. The models are further tested for the assumptions of linear regressions, such as heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and multicollinearity to assess the reliability of the results.

Results on the residential property markets in Berlin

Transaction analysis results

To better understand differences in the number of condominium transactions over time, we first consider trends in the number of MPAs in our interpretation. Among current MPAs, Luisenstadt and Graefestraße in the District Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg were the first two designated areas in 1995. Subsequently, the number of areas only grew slightly to 12 by 2014. In the following years until 2019, the number of MPAs grew rapidly by 46 new areas to a total of 59 MPAs at the time of the study. In 2015, the Berlin state government applied a conversion regulation in all MPAs.

The overall number of transactions in the study area has been quite volatile since 1991 since this period is associated with the real estate boost and crisis of the late 1990s, followed by a long period of relative stagnation (see, ). Since about 2010, recovery has regained momentum, peaking in 2015 after a slight downturn and then a sharp downward turn. Finally, transactions end up at a total of approximately 6,500 which equals the level from the year 2000.

The number of transactions in the MPAs has risen steadily over the years. While the share of total transactions was below 10% until 2012, it steadily increased from approximately 10% in 2013 to 43% in 2019. This is largely due to the increased designation of MPAs. Remarkably, the number of transactions has been growing steadily since 2015, although transactions in the non-MPAs and overall declined significantly.

Our regression analysis on annual transactions shows significant differences between the MPAs and the rest of the areas for eight out of 28 years (See, or or 2 for numerical data). We recognise that the number of transactions in MPAs is frequently lower. Especially significant declines in the MPAs in 1996 (right after the first MPAs were established in 1995) and especially after 2015 (after the extension of the conversion regulation to all MPAs and the designation of eight new MPAs in 2014) imply the effects of MPA regulation on the number of transactions. The development in 2015 is remarkable, as the number of transactions in the MPAs is still falling slightly, while there is already a strong increase in the rest of the study area.

Figure 3. Change in number of transactions at block level compared to baseline in 1991 derived from the regression model.

Table 1. Parametric estimates of the overall regression DID model on the number of transactions (ln) and prices (ln).

Table 2. Selected Regression-DID estimates of MPA effect on prices and number of transactions, 1991–2019.

In both declines, the number in the following years approximates the dynamics of the non-MP areas, although there is generally a sharp decline in the number of transactions across the study area from 2015 onwards. Transactions in MPAs have been significantly far below normal levels since 2015, which is certainly due to increased regulation. Transactions in the more peripheral districts such as Friedrichsfelde or Ober- and Niederschöneweide have declined even further, but popular local districts such as Friedrichshain, Kreuzberg, and Prenzlauer Berg show no further significant differences in terms of their transaction activity. In only two of the eight districts with significantly different transaction rates were these lower in the MPAs than in the rest of the district. In six MPAs, however, they were higher. After 2015, however, these effects are mostly outweighed as the negative interaction effects of MPAs from 2015 to 2019 are mainly larger than the positive effects of individual MPAs.

The transaction activity of former rental flats (converted to condominiums) is moderately higher, but not within MPAs. After 2015, the transaction rates for this property type become significantly lower but remain stable in the MPAs. Many rental flats were presumably converted shortly before regulation and sold in the following years (former flats converted into condominiums do not have to be sold immediately in Germany). Overall, we find that the designation of MPAs ultimately negatively impacts transaction activity. But this does not apply equally to all districts and transaction rates decline a little less in more popular districts. We also observe more former rental housing being sold in MPAs after 2015, which is a sign that landlords converted their flats into condominiums in anticipation of MPA regulation.

Price analysis results

A general increase can also be observed in the price trend, accelerating from around 2010. Descriptive statistics show a comparable development for MPAs and their surrounding areas, although the development in MPAs is rather volatile (see, ). Since 2006, prices here (apart from 2011) have been higher than in the surrounding areas, albeit slightly. Similar to transactions, prices stopped growing in MPAs in 2015 and 2016, after which prices in the rest of the areas caught up. However, since 2018, the gap has been widening again as prices in MPAs pick up more strongly.

shows the analysis of the regression DID model conducted on the purchase prices. These initially rose slightly, only to fall in the mid-1990s to −25% of their 1991 level in 2005. The model also shows that an upward trend has been evident again since 2006, accelerating further since 2010.

Figure 5. Change in condominium prices compared to baseline in 1991 derived from the hedonic model.

Many of the price differences previously noted between the MPAs and the other areas are likely to be related to housing characteristics and only partly to the locations within an MPA. Transactions in the MPAs are generally associated with slightly lower prices when characteristics are considered. A difference of up to 35% can be observed up to 2006. The difference subsequently levels out until it finally amounts to only 4% in 2019. On the contrary, a decline in transaction activity observed in 2015 had no apparent impact on prices. We did not see any slowdown in price increases due to regulations within MPAs when the Berlin property market became attractive again around 2011. MPAs tend to be established in areas with socially weaker populations, which explains the difference observed between MPAs and the other areas throughout the overall period. If the designation of MPAs were effective in containing prices, this difference would have to increase, or at least not continue to converge. As far as price differentials are concerned, regulation has not led to significant disparities.

To explore the question of whether transactions differ structurally across areas, we looked at pricing for some characteristics and noted differences in transaction characteristics between MPAs and non-MPAs. Considerably fewer apartments with occupancy rights for social housing were sold in the MPAs (4% vs. 15%). They are more often equipped with central heating; 98% of condominiums do have, compared to 93% outside of MPAs. Moreover, hardly any social housing has been sold, as shown by the comparatively low levels of public subsidies. The buildings are nearly 100 years old on average and 75% were built before 1945, which is indicative of the historic character of the pre-war neighbourhoods (Charles, Citation2013, p. 1519). In non-MPAs, the buildings were mostly built after 1945. Other major differences in structural characteristics of the apartments are not evident, which may contradict the premise of regulation. This could suggest that the claimed differences are not that great (which underpins the criticism of the MPAs designation process) or that only apartments with certain characteristics are sold within MPAs. Since there is limited information collected on structural characteristics, we cannot conclusively determine this.

We further derive the differences in the pricing of various characteristics in the MPAs and non-MPAs from the regressors of the DID model (see, ). The discussion of the coefficients at this point is limited to the interpretation of the most central differences. Among the structural variables, there are many contributing factors to the purchase price. The size/floor space is the most important (1.07% additional living space), and price differences in the MPAs are small (−0.03%). The premium for historic buildings (built before 1945) is moderate overall (6.7%) but increases sharply to 12.1% in MPAs compared with the reference group. In MPAs, buyers pay a much higher premium for historic buildings than in other areas. Since the share of condominium transactions in historic buildings is relatively high in MPAs, this is a particularly important factor. Consequently, this effect is reversed in newer buildings. Transactions of condominiums in new buildings (not older than 5 years) are generally associated with price increases of 36.4 %, while this drops to 25.6 % in the MPAs. While the rules of milieu protection only apply to existing buildings, it may be the historic buildings that are popular in MPAs and therefore diminish the marginal effect of new construction.

When examining the price effects of former rental apartments that were converted to condominiums, which are particularly regulated in MPAs and often associated with luxury renovations and displacement, we find an overall price discount of 6.7%. In the MPAs, this effect weakens considerably, with a discount of only 3% compared to the reference group. However, when looking at transactions after 2015 (the year where regulations of conversions to condominiums were introduced comprehensively in MPAs), a different finding emerges: Converted apartments are sold at a premium of 0.8%, while there is still a discount of 4.6% in MPAs. We found no evidence that former rental housing in the study area was specifically converted to higher-quality residential properties, but there is a clear indication that restricting conversion may well lower prices for transactions in former rental housing, partly reflecting the short-term increase in the supply of converted condominiums that resulted from the increased conversion seen shortly before regulation.

Considering the restrictions on modernisation in MPAs, we examine whether differences in pricing can be identified for structural housing characteristics. This shows a difference in the price premium for balconies becoming greater. Within MPAs, there is a premium of 4.3% compared to the reference group, whereas outside the MPAs, the premium only amounts to 2.6%. This also applies to elevators, where the premium rises from 10.2% to 12.1%. We interpret the price premiums due to regulation within the MPAs, which prevents the modernisation of the structural equipment of apartments. It is possible that due to the historic building structure of many MPAs, balconies and elevators are less common and therefore associated with higher prices. However, this may also reduce the potential for upgrading the apartments and thus reduce the risk of displacement.

If the condominium was (partially) financed by the social housing programme at the time of construction, a price discount of −9.8% is observed, reflecting a lower construction standard of these apartments. This type of housing is important for the supply of affordable housing and to provide existing tenants the opportunity to purchase their apartments. This discount is even bigger in MPAs (−14.7%). Thus, according to our evaluations, the former social housing is not being sold at comparatively soaring prices nor as luxury refurbishment, even within MPAs, and are comparatively rare among the transactions in the milieu protection areas.

Due to the spatial segmentation of transaction prices, fixed effects of all local districts are also included in the analysis (see, in appendices). The location in the model is interpreted in comparison to the Reinickendorf district since the lowest average prices were obtained here. A significant location effect can be identified for almost all local districts, with Tiergarten Süd and Prenzlauer Berg at the top with 39.6% and 36.7% respectively. A significant difference in MPAs can only be observed in Neukölln, Oberschöneweide, and Wedding. Only Oberschöneweide has a negative coefficient (−24.6 %); and Neukölln and Wedding MPAs are associated with significantly higher purchase prices (+28.7% and +13.8%).

Over the observation period since 1991, transactions in MPAs have tended to be associated with lower prices, as shown by the significant main effect of milieu protection. This reflects a 36.9% drop in transaction prices compared to the reference group. The significant interaction effects of MPAs with a year of transaction (see, ) gradually capture more and more of this effect from 2007 onwards (e.g. +29.8% compared to non-MPA in 2019. See, ). The differences between individual MPAs (apart from exceptions such as Neukölln, Wedding, and Oberschöneweide, where prices tended to be even higher) are not as great as the observed decline in the number of transactions. This suggests that prices in MPAs have caught up with other areas at a tremendous pace in recent years, especially in certain districts. This coincides with the time of a generally tight housing situation in Berlin in certain popular neighbourhoods. Milieu protection does not seem highly effective in dampening prices for residential properties in this market environment.

Discussion

The debate about appropriate strategies for urban development has become a controversial issue, with tenant protection and property promotion often at odds with each other. During the housing crisis in many European metropolises, ownership-restrictive instruments are repeatedly proposed as a means of solving housing issues. In this paper, we examined the instrument of milieu protection and its effect on condominium transactions in Berlin, which restricts the property rights of owners to protect the local population from gentrification. The results can be used to raise awareness of the previously unknown cause-and-effect relationships and make decision-makers aware of them.

In our regression DID analysis, we found that MPA designation reduces the overall condominium transaction rates significantly. This may be attributed to a reduced supply of condominiums due to the difficulty of converting rental housing in MPAs and the lower modernisation rate. This impact was smaller in popular local districts, probably because the attractiveness of the real estate market was high enough to disregard MPA restrictions. This is shown by the lack of significant differences in the number of transactions between MPAs and non-MPAs in the local districts of Prenzlauer Berg, Friedrichshain, and Kreuzberg (see, in the appendices). This difference across the local districts indicates that regulations likely did not add to the attractiveness (whereby the demand effects, similarly to the results of Kahn et al. (Citation2010), might have overcompensated for the supply-dampening effects) but were already established in areas with existing high housing demand. Negative supply effects observed in previous studies on regulations are thus generally also observed following the establishment of MPAs. However, these impacts can be compensated for in popular districts, but not in the other local districts. Furthermore, we discovered that especially former rental flats in MPAs have higher transaction rates, which may be due to owners’ anticipation of these regulations. This jeopardises short-term effectiveness because it motivates the owner to convert, which makes it easier to resell but also potentially facilitates displacement. The deteriorated supply situation in the MPAs outside popular neighbourhoods is likely to hurt property formation. Households (both Berlin residents and immigrants) who need to resupply in the property market are disadvantaged. Even if the formation of home ownership is an often-affirmed political goal, the shortage of condominiums in the MPAs is part of the MPA conception.

To assess effectiveness, it is necessary to measure the impact of the supply shortage on transaction prices in the MPAs, which may also be reflected in rents in the long term. Our regression DID approach has shown that prices in MPAs have increased considerably faster than in surrounding areas in recent years, but the baseline level of transaction prices was much lower. While in the 1990s and 2000s, the differences were consistently over 20%, and this went down to a 10% price difference in 2014 and 2015, when Berlin greatly expanded the concept of milieu protection. Regulation failed to help significantly slow price growth in the property market at that time. In 2019, transactions in MPAs were only 4% lower than other areas. If regulation had led to a loss of attractiveness, the difference would have increased. If the regulation aims to weaken the property market in MPAs, the areas have probably not been designated early enough and/ or comprehensively enough to increase the effectiveness of the instrument following the prerequisites of Vogelpohl (Citation2013). We conclude that regulation is not able to dampen prices in an attractive housing market effectively. In weaker market phases, the differences were indeed visible, but regulation against gentrification is unlikely to be necessary at this point. Politically, intervention is probably also difficult to justify when no distortions are yet visible in the market.

Certain price differences arise from structural differences between MPAs and the rest of the areas. For many of these characteristics, including balconies or elevators, significant premiums must be paid in the MPAs. The premium for a condominium in historic buildings is particularly large, which hurts the affordability of condominiums due to the large stock of this building type in the MPAs. Because other structural characteristics are also more common in MPAs (e.g. slightly larger size and fewer social housing units), prices for condominiums are now higher in total. An explicit price premium due to regulations could not be found (contrary to previous empirical studies), perhaps because the effects on housing supply were not long-term. The small-scale regulation has not diminished the long-term demand for properties in Berlin’s housing market. The milieu protection regulation should therefore not be regarded as a price-dampening instrument, but at most as a short-term intervention against undesirable developments in the housing market. Against this background, the appropriateness of the long duration of some MPAs may be reconsidered. At the time of the study, Berlin had designated every third area for more than five years. There also remains criticism that investments in the modernisation of the housing stock should not be hindered for other reasons such as climate protection or social standards.

On a positive note, we do not find in either the MPAs or the surrounding areas former rental properties being particularly associated with higher purchase prices. Overall, former rental housing showed price discounts of 6.7%, but from the time of stronger regulations in 2015, differences of only less than 1% were evident. We have not been able to find unmistakable evidence that specifically former rental apartments have been converted into higher-quality residential properties, as often opposed. The lack of price differences to the remaining condominiums since 2015 indicates that this housing type has also become more popular with investors. However, the regulations within the MPAs slowed down this price increase. As of 2015, there has been a 5.4% difference between the MPAs and remaining transactions, which can be considered an accomplishment of regulation. However, the results of the restriction on conversions should be viewed with some caution because our data does not contain a record of the time of the conversion. The (presumed) connection between the conversion of a rental flat with subsequent sale and displacement is still insufficiently empirically researched. In our transaction data, approximately 95% of the buyers were private and their rent increase behaviour is considered to be relatively low (Cischinsky et al., p. 137). This is still problematic in terms of displacement if a new proprietor wants to occupy the property personally. To address this, legislators would have to strengthen the tenants’ rights in case of owner-occupation, which is also a strong encroachment on property rights.

Conclusions

This study shows that the cause-effect relationship of instruments on property markets can be complex but is indispensable for evidence-based policy. In particular cases, effective interventions in the housing market can correct imbalances. Notably, other non-focused aspects, such as the municipal right of buying first or restrictions on luxury redevelopment, are also crucial factors in the political evaluation of MPAs. Regarding transactions and property prices, a mixed conclusion can be drawn. Significant inhibited transaction activity can be observed within MPAs and former rental flats were increasingly sold within the MPAs. Notwithstanding, there is a regulation-induced price gap, which subsequently disappears as the housing market tightens; property prices have risen more strongly within the MPAs and are now almost at a comparable price level to non-MPAs. Rather, some structural characteristics such as historic buildings or slightly larger flat sizes make condominiums in the MPAs more expensive compared to the other areas.

We find that the MPA impact on transactions and prices in popular local districts tended to be minimal. The limitation of price effects is, in fact, likely to be necessary for these districts. We suspect that the impact on the property market was not strong enough to generate long-term effects, because the transaction trend was similar sometime after the tightening of regulations in the districts. Limiting conversions, however, also slowed down the price increase of former rental flats, which benefit tenant protection within MPAs. Yet, political assessments of regulation aimed at preventing ownership formation should consider that such ownership formation prevents residents from being further displaced in the long run. This does not mean that interventions in property are generally not appropriate but it means that they must be well timed. Regarding property rights, policymakers should carefully consider whether benefits such as the right of the first buy or regulating conversions truly outweigh the negative effects in the property market.

There are limits to this research approach in terms of content and methodology. It was not possible to consider other structural housing characteristics that might be needed to assess the standard of furnishings and fittings due to the existing data basis. This would provide a clearer picture of what type of former rental housing was converted or how differences in pricing come about. A useful extension of the approach is the investigation of rental prices, which are not collected at specific intervals in a systematic manner, making it more difficult to conduct studies over longer periods. However, in conjunction with data on the social structure of the apartments, a more differentiated picture of possible displacement processes can emerge. Our data set is based on the official collection of purchase prices, which only records data once the buyer and seller have reached an agreement. This, therefore, does not allow for a time-on-market analysis, as no specific data is available. However, such an approach would certainly make a further contribution to increasing the explanatory power of the model. Further, at the time of the study, only data on MPAs that were designated in 2020 were available. We therefore have no information on areas that have since dropped out of the milieu protection, which may distort our results.

Acknowledgments

We thank Expert Committees for Property Values (‘Gutachterausschuss für Grundstückswerte Berlin’) for providing the data on which this article is based.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lion Lukas Naumann

Lion Lukas Naumann, M. Sc. in Spatial Planning and Research Assistant at the Chair of Real Estate Development at TU Dortmund University. Since 2019 he has been working on his doctoral thesis, which deals with the integration of geospatial data analysis in real estate research and practice.

Holger Lischke

Holger Lischke, Department of Planning and Construction Economics/ Real Estate Management, Head of Asset Management at Nox Capital, 2018 – 2020 Postdoctoral Researcher at the Chair of Planning and Construction Economics/Real Estate of TU Berlin. His PhD thesis titled ‘Impact of urban development programs on asking rents’ was supervised by Prof. Kristin Wellner and Prof. Gabriel Ahlfeldt and published in 2020.

Michael Nadler

Michael Nadler, Diplom-Kaufmann (equivalent to MBA) at University Cologne and PhD in Investment & Finance (Business School) at HH University Duesseldorf; Assistant Professor for Real Estate Development & Finance at TU Kaiserslautern; Full Professor for Facility Management HS Albstadt-Sigmaringen; Full Professor for Sustainable Building Management HTWG Konstanz; and Full Professor for Real Estate Development at TU Dortmund University.

Notes

1. The remaining transactions include undeveloped and developed land. In large cities such as Berlin, this includes fewer single-family homes but mostly the purchase of residential complexes or larger portfolios.

2. In Germany, this also applies to social housing, whose occupancy rights expire after up to 20 years without follow-up funding (a reason why the number of social housing units in major German cities is declining sharply).

References

- Ahlfeldt, G. M., Maennig, W., & Richter, F. J. (2017). Urban renewal after the Berlin Wall: A place-based policy evaluation. Journal of Economic Geography, 17(1), 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbw003

- Angrist, J. D., & Pischke, J. ‑. S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press.

- Atkinson, R. (2000). Measuring gentrification and displacement in Greater London. Urban Studies, 37(1), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098002339

- Becker, W. (1994). Lebensstilbezogene Wohnungspolitik — Milieuschutzsatzungen zur Sicherung preiswerten Wohnraumes [Lifestyle-oriented housing policy - milieu protection regulation to secure affordable housing]. Sozialer Fortschritt, 43(4), 96–100. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24510647

- Beran, F., Nuissl, H., & Krämer, S. (2019). Verdrängung auf angespannten Wohnungsmärkten: Das Beispiel Berlin [Displacement in tense housing markets: The example of Berlin] .Wüstenrot Stiftung.

- Charles, S. L. (2013). Understanding the determinants of single-family residential redevelopment in the inner-ring suburbs of Chicago. Urban Studies, 50(8), 1505–1522. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098012465908

- Davidoff, T. (2013). Supply elasticity and the housing cycle of the 2000s. Real Estate Economics, 41(4), 793–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.12019

- Dye, R. F., & McMillen, D. P. (2007). Teardowns and land values in the Chicago metropolitan area. Journal of Urban Economics, 61(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2006.06.003

- Eckardt, F. (2021). Helpless? What to do against gentrification. In F. Eckardt (Ed.), Gentrification: Research and policy on urban displacement processes (pp. 27–37). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-32406-3_6

- Geßner, M. (2008). Leistungsfähigkeit des städtebaulichen instruments milieuschutz für die stadtentwicklung in Berlin [Effectiveness of the urban development instrument milieu protection for urban development in Berlin]. Technische Universität Berlin. https://doi.org/10.14279/DEPOSITONCE-2029

- Gröbel, S., & Thomschke, L. (2018). Hedonic pricing and the spatial structure of housing data – An application to Berlin. Journal of Property Research, 35(3), 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/09599916.2018.1510428

- Gyourko, J. , Molloy, R. , Gyourko, J., Molloy, R. (Eds.). (2015). Regulation and Housing Supply. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics. (Vol. 5, pp. 1289–1337). Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-59531-7.00019-3

- Helsley, R. W., & Strange, W. C. (1995). Strategic growth controls. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 25(4), 435–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-0462(95)

- Herath, S., & Maier, G. (2013). Local particularities or distance gradient. Journal of European Real Estate Research, 6(2), 163–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/JERER-10-2011-0022

- Hilber, C. A. L., & Vermeulen, W. (2016). The impact of supply constraints on house prices in England. The Economic Journal, 126(591), 358–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12213

- Jackson, K. (2016). Do land use regulations stifle residential development? Evidence from California cities. Journal of Urban Economics, 91, 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2015.11.004

- Kahn, M. E., Vaughn, R., & Zasloff, J. (2010). The housing market effects of discrete land use regulations: Evidence from the California coastal boundary zone. Journal of Housing Economics, 19(4), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhe.2010.09.001

- Kok, N., Monkkonen, P., & Quigley, J. M. (2014). Land use regulations and the value of land and housing: An intra-metropolitan analysis. Journal of Urban Economics, 81, 136–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2014.03.004

- Leguizamon, S., & Christafore, D. (2021). The influence of land use regulation on the probability that low-income neighbourhoods will gentrify. Urban Studies, 58(5), 993–1013. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020940163

- Levy, D. K., Comey, J., & Padilla, S. (2007). In the face of gentrification: Case studies of local efforts to mitigate displacement. Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law, 16(3), 238–315. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25781105

- Linden, L., & Rockoff, J. E. (2008). Estimates of the impact of crime risk on property values from Megan’s Laws. American Economic Review, 98(3), 1103–1127. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.3.1103

- Lloyd, J. M. (2016). Fighting Redlining and Gentrification in Washington, D.C. Journal of Urban History, 42(6), 1091–1109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144214566975

- Malpezzi, S. (1996). Housing Prices, Externalities, and Regulation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas. Journal of Housing Research 7(2), 209–241.

- Mayer, C. J., & Somerville, C. (2000). Land use regulation and new construction. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 30(6), 639–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-0462(00)

- Mitschang, S. (2017). Satzungen nach § 172 BauGB [Regulations according to § 172 BauGB]. In S. Mitschang (Ed.), Berliner Schriften zur Stadt- und Regionalplanung: Vol. 32. Erhaltung und sicherung von wohnraum: Fach- und rechtsfragen der planungs- und Genehmigungspraxis [Preservation and safeguarding of housing: Technical and legal issues in planning and approval practice] (1st), pp. 51–118). Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. https://repository.law.wisc.edu/api/law_fileserve/search?mediaID=85689?accessMethod=download

- Nelle, A., Veser, J., & Diez, B. (2021). Monitoring zur Anwendung der Umwandlungsverordnung 2020 [Monitoring the application of the Conversion Regulation 2020]. Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen Berlin (SensW). https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/staedtebau/foerderprogramme/stadterneuerung/soziale_erhaltungsgebiete/download/jahresbericht2020.pdf

- Nesset, I. Q., & Oust, A. (2019). The impact of historic preservation policies on housing values. International Journal of Housing Policy, 108(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1688633

- Oba, T., & Noonan, D. S. (2017). The many dimensions of historic preservation value: National and local designation, internal and external policy effects. Journal of Property Research, 34(3), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09599916.2017.1362027

- Pope, J. C. (2008). Fear of crime and housing prices: Household reactions to sex offender registries. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(3), 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2008.07.001

- Quigley, J. M., & Rosenthal, L. A. (2005). The Effects of Land-Use Regulation on the Price of Housing: What Do We Know? What Can We Learn?. UC Berkeley: Berkeley Program on Housing and Urban Policy. 8(1), 69–137. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90m9g90w .

- Riemann, C. S. (2016). Baurechtliche instrumente gegen gentrifizierung [Building law instruments against gentrification] (1st) ed.). KSV Verwaltungspraxis. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783845282077

- Saks, R. E. (2008). Job creation and housing construction: Constraints on metropolitan area employment growth. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(1), 178–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2007.12.003

- Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Wohnen Berlin [SensW]. (2021). Soziale Erhaltungsgebiete [Social preservation areas].City of Berlin. https://www.stadtentwicklung.berlin.de/staedtebau/foerderprogramme/stadterneuerung/soziale_erhaltungsgebiete/index.shtml

- Somerville, T., Wang, L., & Yang, Y. (2020). Using purchase restrictions to cool housing markets: A within-market analysis. Journal of Urban Economics, 115, 103189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2019.103189

- Turnbull, G. K., Waller, B. D., Wentland, S. A., Witschey, W. R. T., & Zahirovic-Herbert, V. (2019). This old house: Historical restoration as a neighborhood amenity. Land Economics, 95(2), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.3368/le.95.2.193

- Vogelpohl, A. (2013). Mit der sozialen erhaltungssatzung verdrängung verhindern? Zur gesetzlichen regulation von aufwertungsprozessen am beispiel Hamburg [Preventing displacement with social preservation statutes? On the legal regulation of upgrading processes based on the example of Hamburg]. Hamburg University. http://www.geo.uni-hamburg.de/de/geographie/dokumente/personen/publikationen/vogelpohl/vogelpohl_soziale-erhaltungssatzung.pdf

- Vogelpohl, A., & Buchholz, T. (2017). Breaking with neoliberalization by restricting the housing market: Novel urban policies and the case of Hamburg. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(2), 266–281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12490

- Walser, M. (2018). Putting the brakes on rent increases: How the United States could implement German anti-gentrification laws without running afoul of the takings clause. Wisconsin International Law Journal, 186(36), 187–213. https://wilj.law.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1270/2019/11/Walser-Final-2.pdf.

- Watt, P. (2009). Housing stock transfers, regeneration and state-led gentrification in London. Urban Policy and Research, 27(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111140903154147

- Zahirovic-Herbert, V., & Chatterjee, S. (2012). Historic preservation and residential property values: Evidence from quantile regression. Urban Studies, 49(2), 369–382. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098011404936

Appendices

Table A1. Description of the variables used in the regression DID.

Table A2. Descriptive statistics.

Table A3. Regressors of the individual local districts in the hedonic price model.