1. Introduction to special issue on gamification: what legitimate business do information systems (IS) researchers have with gamification research?

With thousands of peer-reviewed publications and thousands of applications in education, industry, and government, gamification has taken the world by storm. But this explosion of gamification is increasingly rife with controversy, leaving unanswered many provocative questions: Is this old wine in new bottles? Is gaming running amok in our nongaming lives? Is it a good idea to treat nongaming situations as games? After all, although life can be like a game, it is not; the same is true of business. Perhaps most controversially, critics have even obtusely argued in peer-reviewed publications by esteemed publishers that “gamification is bullshit” or a mere “party trick” (i.e., Bogost, Citation2014, MIT Press). Thankfully, such schoolyard broadsides are being elegantly, systematically, theoretically, and empirically addressed in the maturing gamification literature (i.e., Bai et al., Citation2020). Regardless of where one stands on gamification, it can aptly be described as interesting, provocative, galvanising, and controversial. We view gamification research and practice as a largely uncharted new world in desperate need of brave navigators, generous benefactors, sturdy ships, abundant cargo, and dedicated crew – all working in concert to discover a bounty of new intellectual treasures that will subsequently address unresolved research and practice issues.

As classically trained IS researchers who engage in gamification research, we have observed substantial discomfort among some in the IS discipline who question why any serious IS researcher would delve into research involving gamification. The eyerolling, innuendo, and sideswipes from such staid scholars is that “real” scientists do not deal with games and must stick with austere, tried-and-true, business-like topics free from any trace of play. Sadly, much of this “austerity gospel” is based on the uninformed assumption that gamification is about games and that gamification research is not a serious science or that its purpose is to merely to induce fun. In fact, gamification’s focus is not on gaming; instead, it focuses on improving nongaming systems and processes using principles and artefacts partially derived from and inspired by gaming (e.g., Koivisto & Hamari, Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2017; Seaborn & Fels, Citation2015; Treiblmaier et al., Citation2018).

With this framing, we are pleased to offer a provocative editorial on gamification to open this EJIS special issue on gamification. In the remainder of our editorial, we deal specifically with the criticism lobbed at us by some IS researchers in conjunction with this special issue: “What legitimate business do IS researchers have playing in the gamification discourse?” Our position is that gamification is not a fad or a myth but an increasingly influential, interdisciplinary discourse in research and practice (which some would argue is emerging as a discipline in itself) and that the information systems (IS) discipline has the opportunity to play an outsized role in navigating this discourse. We assert that active engagement in the gamification discourse is a compelling IS research opportunity, especially in view of the growing, globalised platform-based economy: First, the IS discipline is highly interdisciplinary and thus open to new methods, theories, questions, and problems. Second, the IS discipline is strongly focused on the sociotechnical and the sciences of the artificial, such that IS researchers are often natural design thinkers who deal with system components and artefacts and who consider people, process, organisations, culture, and other crucial contextual nuances, with a strong focus on original theorisation. Third, the gamification research discipline has a strong need for original theorisation, and so does the IS discipline. Fourth, gamification and IS are highly complementary research discourses, because they delve into many of the same reference disciplines, theories, constructs, questions, and problems. Thus, entering into a mutual discourse could give rise to a vibrant network of synergies.

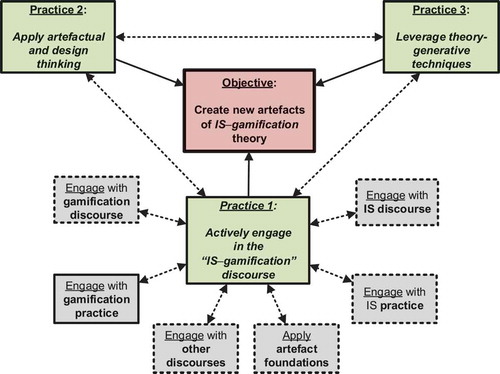

Consequently, we frame our editorial with the knowledge we have gained as IS researchers who engage in gamification research in an effort to share with both IS and gamification scholars what we have learned about artefacts and original theorisation. We do so by proposing a pragmatic path forward for gamification and IS researchers who wish to contribute to these related discourses. Next, we propose a framework of three practices that we are confident can more systematically generate the key theoretical artefacts needed to generate native theory in the IS–gamification discourse and hence to improve the associated research and practice.

2. An Approach to generating native IS–gamification theory

Our position is that both IS and gamification scholars need to actively foster conditions that enable strong native theory to emerge. It could be argued that IS researchers are further along in theorisation and that gamification researchers are further along in developing artefacts and metaphors. Thus, fusing these discourses is potentially synergistic, especially as they are both emerging. A common conundrum for an emerging discourse is that to conduct research that can be published in top journals, its researchers typically excessively borrow artefacts of theory (aka components or products) from other disciplines (i.e., frameworks, models, concepts, variables, laws, axioms, claims, statements, propositions, hypotheses, boundary conditions, and assumptions); ironically, this borrowing, which hastens publication of empirical work in the short term, thwarts original theorisation in the new discipline in the long run (Hassan, Citation2014; Hassan & Lowry, Citation2015; Hassan et al., Citation2019).

The pragmatic corollary is that the more a discourse has its own original artefacts of theory, the more the discourse can create native theory that has greater influence over the long term, allowing it to grow into a healthy, respected discipline that contributes to the larger scientific dialogue outside its discipline.i Thus, the objective of this editorial is to help interdisciplinary IS–gamification researchers create such original theoretical artefacts. We propose a framework for this goal (see ) that draws inspiration from the discourse emphasis and associated framework proposed by Hassan et al. (Citation2019, p. 202), with liberal modifications. Our editorial proceeds by explaining the three major practices encapsulated in :

Practice 1: Actively engage in the combined IS–gamification discourse

Practice 2: Apply artefactual and design thinking to the combined IS–gamification discourse

Practice 3: Leverage theory-generative techniques to expand the IS–gamification discourse

2.1. Practice 1: actively engage in the combined IS–gamification discourse

Fundamentally, each discipline or discourse generally cares about different questions. Thus, to practice discursive theorising, researchers must focus on the ideas that matter within the discipline’s discourse by forming the discourse itself, problematising, leveraging paradigms, and bridging nondiscursive techniques (Hassan et al., Citation2019).ii If pursued by IS–gamification researchers, these foundational discursive practices will result in what we call the “IS–gamification discourse”. Because both parent discourses are pragmatic, design-oriented disciplines focused on problems that occur in practice, it is imperative that the IS–gamification discourse be balanced and actively engage in both practice and research. To complete this section, we expound on these ideas with four related practices:

Practice 1a: Be well informed about the discourse entered and have an appropriate conversation

Practice 1b: Be deliberate about the context choices made in the IS–gamification discourse

Practice 1 c: Practice interdisciplinary-engaged scholarship with other discourses

Practice 1d: Be aware of new discourses and open to engaging with them

Figure 1. A framework of three practices for generating new artefacts of IS–gamification theory

2.1.1. Be aware of the discourse entered and have an appropriate conversation

The “gamification discourse” is not new; it began the moment the term “gamification” was coined. The larger issue is that many gamification and IS researchers are poorly informed about the discourses they are entering and thus often pursue the wrong conversation in the wrong discourse (e.g., asking or answering the wrong questions). As long as the primary discourse at hand is a “gaming discourse”, an “education discourse”, a “management discourse”, or a “psychology discourse”, the majority of the theoretical advancements will be specific to the discourse in question, not to the IS–gamification discourse. For IS–gamification theory to advance, more researchers need to be well informed about and to deliberately engage in the IS–gamification discourse, even if they are focused primarily on contributing to other discourses.

2.1.2. Be deliberate about the context choices made in the IS–gamification discourse

An especially useful way to further understand the IS–gamification discourse versus other discourses is to be more deliberate about context choices in research. Leading theorists in pragmatic disciplines have long asserted that good theory is highly contextualised – not just in specific contexts but for specific problems, questions, and phenomena of interest (Boss et al., Citation2015; Currie, Citation2009; Rousseau & Fried, Citation2001; Whetten, Citation2009; Zahra, Citation2007). Thus, context says a lot about discourse and a lot about the associated need for theory development. Consider the vast interdisciplinary array of research and practice contexts in which gamification has been applied – from education and employee productivity to healthcare, fitness, and sustainability. These legitimate and interesting IS–gamification research contexts have starkly different goals, research questions, and constructs and thus differing theoretical needs with varying theoretical explanations. Because of these fundamental differences, the artefacts and other “products of theory” (Hassan, Citation2014) involved are also highly disparate. This is a pragmatic illustration of why contextual thinking and discourse thinking are pivotal to any discipline. Moreover, we assert that most such contextualisation is fundamentally inspired by practice, not literature reviews – pointing to the necessity of engaging actively with practice.

2.1.3. Practice interdisciplinary-engaged scholarship with other discourses

We are not advocating isolationism; in fact, we advocate and embrace highly interdisciplinary-engaged scholarship (cf. Van de Ven, Citation2007). The more we collectively challenge, refine, and focus the IS–gamification discourse, the more we must understand and engage with other discourses to do this well. Other discourses are key sources of inspiration and theoretical artefacts that we would be foolish to ignore, because good concepts and good theory are not created in a vacuum. The legitimacy of an emerging discourse is highly determined by how much it inspires other disciplines and discourses. Aside from the discourses of IS and gamification, IS–gamification researchers should engage with related discourses to both provide and receive inspiration – especially gaming, computer science, healthcare, social media, exercise science, education, psychology, HCI, management, and marketing. Although this list represents a good foundation, there is no permanent or required set of discourses with which the IS–gamification discourse can or should engage; it is pivotal to seek continual inspiration from other emerging discourses as well.iii

2.1.4. Be aware of new discourses and open to engaging with them

It is flawed to assume there is a “blessed” and unmalleable set of discourses with which IS–gamification researchers should engage. New discourses often emerge as entirely new disciplines because of advances in an older discourse. AI has been around for decades, but it was not until enough cheap computational power, data storage, and advances in analysis software emerged that AI entered its current, dramatic wave of influence. Issues with population, pollution, wealth, pesticides, distribution inequities, and sustainability problems have breathed new life into food and agriculture science, with new theories, techniques, and discoveries emerging at a staggering pace – even though the science has been around for arguably around 12,000 to 23,000 years, since the time humans started studying and implementing systematic farming techniques. These are examples of why paying attention to scientific discourse matters. Moreover, emerging scientific disciplines and their associated discourses can provide impressive sources of inspiration for analogies, metaphors, taxonomies, and other theory-generation practices.

Without understanding and engaging in the IS–gamification discourse, as well as understanding and informing related discourses, it will be exceedingly difficult to advance related theory building – whether this entails the effective contextualisation of reference discipline theories, the creation of original artefacts of theory, or the generation of native gamification theory. By contrast, as this engaged thinking is broadly applied, it can result in radical changes to the way a researcher sees science and the world. This kind of thinking is highly inspiring because of the clear, abounding, and compelling opportunities it generates – the kind of inspiration that likely attracted us to science in the first place.

2.2. Practice 2: apply artefactual and design thinking to the combined IS–gamification discourse

Here, we adapt and propose techniques that researchers can use to improve the quality of the discourse and its resulting theory building. These techniques are grounded in design thinking, a lens that unifies the IS and gamification discourses because both have a strong relationship with practice, design, HCI, and system building. Thus, design and its artefacts are foundational artefacts of theory in the IS–gamification discourse that must be included as theoretical components that inform concepts and constructs. We thus suggest three key-related practices:

Practice 2a: Revisit, challenge, and refine the “IS–gamification design artefact”

Practice 2b: Broaden and build IS–gamification artefactual thinking

Practice 2 c: Problematise the research to raise “IS–gamification questions”

2.2.1. Practice 2a: revisit, challenge, and refine the “IS–gamification design artefact”

Because the IS–gamification discourse has strong roots in design, it is crucial to revisit, challenge, and refine the “design artefact.” We define the IS–gamification design artefact as the interface-design choices regarding mechanics and dynamics and the resulting functional affordances – whether intended or unintended – involved in implementing gamified IS. Intended and unintended consequences of design are manifest in the affordances the design offers juxtaposed to the users’ motivations. In view of this link, we recommend applying the concept of functional affordances developed by the IS researchers Markus and Silver (Citation2008) to derive and apply the formal concept of functional IS–gamification affordances.iv

To advance this conversation, we combine the gamification and IS discourses on motivation and design (Blohm & Leimeister, Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2015; Liu et al., Citation2017; Lowry et al., Citation2015; Markus & Silver, Citation2008; Santhanam et al., Citation2016; Seaborn & Fels, Citation2015; Silic & Lowry, Citation2020). Accordingly, we denote the degree to which the design artefact focuses on the mechanics (e.g., primarily through interface-design choices) or the dynamics (e.g., flow, interaction of design, or underlying spirit of the affordances that are selected), and we indicate some of the key motivations that are typically associated with the design choices.v Appendix A Table A1 depicts our taxonomy of these design artefacts, with their mechanics, dynamics, and motivations.

2.2.2. Practice 2b: broaden and build IS–gamification artefactual thinking

Although the design artefact – which focuses on the actual interface and interaction with humans – and its associated affordances are fundamental to theory generation in the IS–gamification discourse, the design artefact is not the only type of artefact that should be considered. Here, we turn to parallel lessons from IS researchers who similarly felt the broader IS discipline was too focused on the IT artefact itself, at the expense of other consequential factors, like processes, organisations, people, society, and the intersection of these and other factors (Currie, Citation2009; Lee et al., Citation2015; Lowry et al., Citation2017). We concur with Lowry et al. (Citation2017) that “such artefacts derive from the ‘sciences of the artificial’, such that they are not governed by natural laws of nature but are created by humans and organizations (Simon, Citation1996)” (p. 548). Thus, the key is to examine the contexts and questions in which gamification is (or should be) applied to IS and then consider the human-created factors that would bear on the adoption, effectiveness, or unintended implications of gamified IS. Last, these derived artefacts need to be systematically considered in terms of (1) broader design, artefact, and organisational choices that would deliver them effectively (e.g., processes and procedures, reward structures, implementation, training, change management, strategy, and governance), (2) resulting affordances and their interplay with various user motivations, and (3) the underlying concepts and constructs involved in the previous two considerations. Here, context is key.vi Our brainstorming about these possibilities has led to the following set of artefacts and definitions that bridge the IS–gamification discourse, which are further elaborated on in Table A2:

Ethical and legal artefact (phenomena related to the rational application of the morality of decisions and considerations of law and regulations that directly involve gamified IS)

Fitness artefact (phenomena involving the application of gamified IS to improve personal fitness or training)

Health artefact (phenomena involving the use of gamified IS in healthcare, by both patients and medical practitioners)

Information artefact (phenomena dealing with the data, information, and knowledge stored, accessed, and generated from gamified IS)

Learning artefact (phenomena related to how people learn best and retain knowledge in respect to gamified IS education or training)

Organisation artefact (organisation-level phenomena that directly involve decisions, processes, and outcomes within an organisation as they relate to gamified IS)

Security and privacy artefact (phenomena of process, organisation, people, threat, legal issues, protection, society, and vulnerability of gamified IS as they relate to privacy and security)

Social artefact (social, cultural, and group-level phenomena involving gamified IS)

Technology artefact (tangible phenomena related to the nexus between gamified IS and physical computing equipment, software, networks, or interfaces)

2.2.3. Practice 2 c: problematise the research to raise “IS–gamification questions”

To recognise and build the “IS–gamification discourse”, researchers must follow the pragmatic course of actively applying the concept of problematisation or problematising (Alvesson & Sandberg, Citation2011, Citation2013).vii Thus, we build the IS–gamification discourse and foundation for native theory when we ask and answer “IS–gamification questions” as opposed to “education questions”, “management questions”, or “psychology questions”. Naturally, there is a key theoretical tie between IS–gamification questions and IS–gamification artefacts, such that researchers are generating artefacts that other disciplines or discourses are not generating or are incapable of generating. These unique artefacts point to concepts and constructs that we uniquely want to explain and predict. We can make them more meaningful by putting them in a specific context, motivated by a problem in that context. Understanding and building on these IS–gamification artefacts is of paramount importance, because the artefacts and contexts lead to questions that are interesting and relevant to IS–gamification researchers and that help researchers identify better forms of theoretical contextualisation or problems that require native theorising.

2.2.3.1. Identify “good problems”.

It is not enough to address questions other discourses are incapable of handling, or worse, those they do not find interesting. Instead, the questions that should be raised are those that enable scholars to identify problems for which there is a compelling need for a solution, ideally those that involve conflict, paradox, trade-offs, uncertainty about underlying assumptions, or disputes that matter to both gamification research and practice (cf. Bacharach, Citation1989; Corley & Gioia, Citation2011; Van de Ven, Citation1989; Weick, Citation1989; Whetten, Citation1989). Accordingly, IS–gamification questions will not just be problematised well (e.g., Alvesson & Sandberg, Citation2011) but will also lead to vital and interesting research (e.g., Alvesson & Sandberg, Citation2013) that IS–gamification researchers and practitioners care about.viii

2.2.3.2. Pay close attention to the discursive conversation.

Mindfully entering a non-IS–gamification discourse can lead to powerful interdisciplinary research that contributes to other discourses. This can also help IS–gamification researchers better understand the work of the scholars with whom they are entering into a research conversation, which is a thorny issue in highly interdisciplinary areas. Pragmatically, most IS–gamification researchers have responsibilities to other discourses – aside from IS and gamification. This is particularly true because both of these foundational discourses were originally built by scholars trained in other disciplines and housed in departments of other disciplines. Thus, it is crucial to understand whether one is entering an existing reference discipline’s discourse, the discourse of one’s classical training, or a new interdisciplinary discourse. For example, we would argue that the question, “How can we encourage more workers to adopt gamification technology?” is a technology-adoption, and hence an IS, research question that can be contextualised to gamification and can thus become part of the IS–gamification discourse. Here, it may be appropriate to leverage a reference theory from the IS adoption literature, such as UTAUT (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003).ix We are by no means saying that those who are interested in the IS–gamification discourse must stay within its “bounds”; instead, we are asserting that awareness of the actual discourse into which a problem or question will lead us is crucial to how we frame our research and to our determination of which discourses we enter and which we avoid.x

2.2.3.3. Embrace reference discipline theories but challenge their assumptions.

Reference discipline theories can and should be a source of inspiration to IS–gamification researchers rather than a hindrance (cf. Treiblmaier et al., Citation2018). First, knowing these theories deeply is pivotal for successfully contextualising and extending them to IS–gamification questions and contexts, which is a foundational theory-building skill known as theoretical borrowing (Oswick et al., Citation2011). Second, in seeking inspiration for new theoretical artefacts, or even lofty native theory, it is highly generative to deeply understand the assumptions, boundary conditions, causal explanations, laws, axioms, claims, propositions, and other key artefacts of the theory being considered. Superficially relying on previous studies for this understanding thwarts theory generation and compounds incorrect traditions and misapplications of theories that, as a result of such carelessness, run through virtually every discipline. Challenging assumptions are foundational to theory building and advancing science and has long been the mark of the great scientists who focused more on innovative ideas that challenged the status quo than on novel methods and data.xi

2.2.3.4. Find tensions in the causal mechanisms.

Here, a careful examination of the underlying causal mechanisms that link predictors and the predicted, that is, the independent constructs and dependent construct(s), can be particularly helpful. This deep reflection is pivotal, because some of these elements – often the assumptions, causal explanations, and constructs – conflict with or even contradict the theory’s use in a gamification context. It is exhilarating to discover these tensions because they point to aspects of these theories that must be challenged with new theory or carefully recontextualised for more effective use in gamification. Thus, every such tension is a research opportunity to engage in and build the IS–gamification discourse.

2.2.3.5. Embrace the “dark side” and seek the “messy”.

Other kinds of tensions are found in messy or negative research results, or in the several “dark sides” of gamification involving unintended negative consequences. It is crucial to consider these negative consequences because they challenge the fundamental assumptions of our discourse. Pragmatically, it is widely claimed (and highly plausible) that most gamification attempts in industry fail (Gordon, Citation2015); thus, understanding why these failures occur is pivotal.xii

2.2.3.6. Tie the outcomes to contexts and to questions.

Researchers should especially carefully consider the dependent construct(s) of a theory, along with the quality of the underlying evidence, to explain the causal mechanisms that explain or predict the dependent constructs and hence to evaluate how compelling and elegant the theoretical story is. This alone says a lot about a theory, because a good theory in applied disciplines is designed to explain a meaningful construct or related constructs and to do so in specific contexts (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Whetten, Citation2009; Zahra, Citation2007). We can thus examine the outcome of the theory, along with all its other contextual considerations, to address some of the most pivotal questions of theory building, such as:

Which questions is this theory fundamentally designed to answer, and which questions does this theory not answer?

Which discipline(s) are best positioned to ask and answer the questions for which this theory is designed?

From an IS–gamification discourse perspective, we should carefully examine the questions answered by these theories and roughly categorise them into three buckets:

Questions that researchers should ideally be asking because the associated problems are at the core of IS–gamification artefacts, because the potential-associated answers are interesting and not obvious, and because researchers in this discourse are best positioned to contribute to addressing the question.

Questions that researchers could be asking because even though the associated problems are not at the core of IS–gamification artefacts, the potential-associated answers are interesting and not obvious and researchers in this discourse are well positioned to contribute to other discourses and foster interdisciplinary exchange and theory building.

Questions that researchers should likely not be asking because the associated problems are tangential to IS–gamification artefacts, because the potential-associated answers are not interesting or are considered obvious, or because researchers in this discourse are not well positioned to contribute to addressing the question.

Navigating towards the first two buckets will more likely steer researchers into the blue ocean.

2.3. Practice 3: leverage theory-generative techniques to expand the IS–gamification discourse

Design and artefactual thinking are pivotal to providing the necessary artefacts of theory (or “products” of theory) (cf. Hassan, Citation2014) that can provide building blocks for rich theorisation. Thus, in addition to all the generative practices we advocate, we endorse a continuous feedback loop between artefact generation and engagement with practice. Although these techniques are necessary, they are insufficient for native gamification theory to emerge. Given the importance of novelty, surprise, paradox, elegance, and other related factors of good theory (e.g., Corley & Gioia, Citation2011; Weick, Citation1989), IS–gamification researchers should engage in theory-generative techniques. Hassan et al. (Citation2019) calls these “generative theorizing practices”, and they focus on analogising, metaphorising, mythologising, modelling, and constructing frameworks. There are many others that can be practised. The generative techniques we believe are most fitting and promising for the IS–gamification discourse are:

Practice 3a: Challenge existing analogies and metaphors, and generate new ones

Practice 3b: Create novel constructs and measures

Practice 3 c: Create taxonomies and typologies

Practice 3d: Expand the epistemological assumptions and the accepted methods

2.3.1. Practice 3a: challenge existing analogies and metaphors, and generate new ones

Opportunities in this discourse particularly relate to analogising and metaphorising, because both discourses were, from their early stages, built on these concepts and because these tools contain powerful stories that galvanise human cognition. For theory-building purposes, we can state briefly that metaphors are basically analogies in linguistic form (Hassan et al., Citation2019); thus, we focus more on explaining the power of analogising for theory building. For convenience, we use “analogy” to refer to either term.xiii Analogies have long been the foundation of Western knowledge and science (Foucault, Citation1972; Hassan et al., Citation2019), and all the great scientists and theories have built heavily on analogies and metaphors. Just one impressive example is Watson and Crick’s discovery of the double helix (Watson, Citation1968).xiv

2.3.1.1. Gamification itself is an analogy

Accordingly, IS–gamification researchers are in excellent company, as gamification itself is an inspiring analogy. Consequently, gamification is replete with analogies and companion metaphors – providing fertile seeds to grow impressive native theory. Part of the idea here is not only to plumb new analogies, but also to understand, challenge, and re-examine the analogies we have been using. In fact, most of the design artefacts implemented in gamified IS are based on analogies, whether they are avatars, badges, competition, gaming, leaderboards, play, or quests. These analogies interact with all aspects of the IS–gamification artefact, from interface design and process to the user experience itself. Thus, in gamified IS design and research, there is a strong correspondence between analogies, design artefacts (mechanics and dynamics), and even concepts and constructs.

Given that gamification analogies come primarily from games and gaming, gaming is also a fertile hunting ground for analogies that people will naturally understand and transfer automatically to gamified IS. This transfer may seem magical, but it is based in cognitive science: Effective analogies and metaphors (and associated visualisations) invoke powerful stories that convey deeper understanding and associations because they tap into the fact that human memory consists of story-based schemas (Gaskin et al., Citation2016; Hull et al., Citation2019; Mirkovski et al., Citation2019). In just one word or phrase, the user automatically knows what to expect and even the rules of engagement – something that months of arcane corporate training cannot accomplish.xv Accordingly, in collaboration with several interdisciplinary researchers, we brainstormed a list of analogies and metaphors and corresponding visuals that may inspire future IS–gamification artefacts, theory, and research (see Table A3).

2.3.1.2. But do not apply them gratuitously!

Despite the inspiring and impressive array of metaphors and visuals that can be leveraged for IS–gamification research, we caution that many of these could be inappropriately applied. Thus, researchers need to examine the roots and assumptions of these analogies with great scrutiny and carefully contextualise them if they are applied to research and practice. We need to be especially cautious of cultural assumptions and harmful stereotypes infused into much of gaming and pop culture. Some analogies that might be appropriate for gaming could be highly inappropriate, offensive, or even harmful for gamified IS. For example, many pervasive gaming analogies and metaphors are rooted in masculinity, aggressiveness, or Western cultural ideals (Ching, Citation1993; Möring, Citation2013). Thus, it is pivotal not to fall into the “metaphoric fallacy” of confusing analogy/metaphor with its definition, such that we retain the following simile (a type of analogy) prominently in mind: although business (or life) may be like a game, it is not a game (Hamington, Citation2009). This is true of other compelling IS–gamification contexts, such as education, marketing, software engineering, and healthcare. For example, “shooting and reloading” could be a particularly inappropriate and harmful metaphor in a gamified IS in the workplace or in a training setting. Likewise, themes based on stereotypically Caucasian, male, Western cultural norms, imagery, and language would likely undermine work environments devoted to inclusivity.

2.3.2. Practice 3b: create novel constructs and measures

Without novel constructs, novel theory cannot emerge. The key purpose of a good theory is to explain and predict a phenomenon of interest in a specific context, and this phenomenon needs to be essential to the discourse and bolstered with at least some original, novel constructs from the discourse (cf. Corley & Gioia, Citation2011; Weick, Citation1989). Thus, native IS–gamification theories would deal with phenomena, explanations, predictions, and questions that are best studied by IS–gamification researchers because they are designed with this discourse in mind. Thus, the other foundational activities that precede concept generation are pivotal to advancing native theory.

As researchers gain a better understanding of the IS–gamification discourse, expand their knowledge of the artefacts, generate novel, context-specific questions, and generate new analogies and metaphors, they will have created conditions ripe for the creation and definition of novel constructs, along with associated novel manipulations and measures – which are not superficially borrowed from other discourses. Here, we remind researchers to think carefully about the difference between concepts, constructs, and variables and apply them at the right level in theorisation and application of methods, as confusing or misapplying these is a common theory-and-method stumbling block.xvi A starting point may be to consider the fundamental difference between instrumental outcomes and experiential outcomes (Liu et al., Citation2017), as this has long been a useful distinction in the TPB’s explanation of attitude differences and associated outcomes (Ajzen, Citation1991); nonetheless, this is an insufficient distinction for breakthrough IS–gamification research.xvii We instead must apply an engaged understanding of the context and problems in revisiting the artefacts, metaphors, and questions, determine what concepts and constructs are involved, and then consider how they can be designed, manipulated, and measured and what the broader harder-to-measure motives and conflicts might be. Too clean of a correspondence between all these parts is an indication of superficial conceptualisation, because it fails to capture how interesting problems in messy contexts present themselves in reality.xviii

Moreover, IS–gamification researchers should not dismiss measurement as “mere operationalisation” apart from theory. Measurement is essential to theory building because it bridges method and theory, which is why content and construct validity are vital (Boudreau et al., Citation2001; MacKenzie et al., Citation2011). Also, there are many other key validity considerations, such as test–retest validity, convergent validity, discriminant validity, nomological validity, external validity (i.e., reliability) (Boudreau et al., Citation2001; MacKenzie et al., Citation2011), and the increasingly vital consideration of ecological validity (Lowry et al., Citation2017). Bridging theory and method is pivotal to science because even when the theory is correct, procedures, manipulations, designs, artefacts, and measurement that do not correspond to the theory or the constructs will create misleading results. Moreover, a proper content-validity exercise is a discourse that involves participants, primary researchers, practitioners, and researchers outside of a research project.

2.3.3. Practice 3 c: create taxonomies and typologies

No mature discourse can emerge without a common nomenclature, foundational concepts, and taxonomies and typologies (e.g., Earl, Citation2001; Posey et al., Citation2013; Son & Kim, Citation2008). Our design artefacts are an ideal starting point because they are well documented in research and practice and thus lend themselves to typologising (cf. Table A1). Creating typologies or taxonomies is a critical step of theorising that is required before a field can advance its theorisation, construct generation, and measurement and deepen its discourse (Doty & Glick, Citation1994; Posey et al., Citation2013). Consider, for example, what the periodic table did for chemistry and what the classification of species did for biology.xix In early discipline development, because the core participants come from other discourses, they often introduce contrasting nomenclature that can foster a Tower of Babel phenomenon in which researchers are literally speaking different languages. This confusion of terms limits understanding and progress – making it difficult to meaningfully communicate with practitioners. This is a serious potential risk for gamification research, given the many disciplines in which gamification researchers have been trained.

2.3.4. Practice 3d: expand the epistemological assumptions and the accepted methods

Most gamified IS research to date has been conducted with either an exploratory empirical focus or a post-positivistic theory focus, and the most common methods employed are surveys, field experiments, and controlled laboratory experiments. Although there is no epistemological rule that one’s theoretical philosophy dictates method – as these should be separate considerations – many researchers fall into this trap, which blunts theory generation, such that their narrow methods expertise limits the theoretical possibilities they allow themselves to explore. The key solution here is to divorce method from theory and to divorce epistemological assumptions from theory.

2.3.4.1. Rigid post-positivism is a mental trap.

We also challenge researchers to avoid forcing themselves into rigid epistemological thinking.xx We argue that a trap of rigid post-positivistic thinking – especially in blue-ocean emerging discourses – is the mistaken belief that “theory is knowable” and should be figured out first and that the rest of the research, therefore, follows sequentially, similarly to applying the “waterfall method” to software development.xxi The waterfall method ensures software project failure in complex software projects – so why would computing-related scientists knowingly apply a similarly pedestrian process to their research and theory building, as though scientific research is a four-step process in which the steps can be checked off sequentially without iteration?

2.3.4.2. Practices that free us from rigidity.

But how can this realistically be done? Aside from discursive thinking and engaged scholarship, which we have emphasised, several high-quality methods are available that also enrich preliminary concept development and theory building. These are interviews, the case method, and various powerful forms of grounded theory building. Even for researchers who are highly data focused, rooted in post-positivism, and uninterested in learning rigorous new methodologies, we suggest a series of practices they can apply that can improve the quality of their theorisation, as shown in Online Appendix B.

3. Conclusion

We have made a strong case that gamification is not only an appropriate research area for IS researchers, but one on which the IS community has the opportunity to exert an outsized influence by building the IS–gamification discourse. We specifically explain and demonstrate how IS–gamification researchers can generate novel artefacts of theory that can foster original theorisation and more original contributions to this discourse. On this note, we are pleased to introduce the articles selected for the special issue, because we found each of them to be promising in furthering the IS–gamification discourse through the novel artefacts of theory they generate. These five articles expand the IS–gamification discourse and are theory-generative because they generate novel artefacts of theory, using design thinking, original data, and original contexts (we underline some key contributions that pertain to our editorial and framework), as follows:

Khan et al. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1780963 [framework and opinion]

In this conceptually focused opinion piece, the authors directly address the thorny issues of mixed results in organisational use of gamification. They do so by proposing a framework grounded in adaptive structuration theory that is used to reveal a compelling set of concepts, constructs, and research questions and a rich research agenda for expanding the IS–gamification discourse.

Schöbel et al. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1796531 [taxonomy]

This compelling effort provides an original taxonomy of gamification artefacts with the aim of helping researchers and practitioners create original gamification concepts and novel gamification designs. To do so, they leverage the literature and practice engaged scholarship using expert interviews. They also contribute by demonstrating a novel method for taxonomy building.

Dincelli et al. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1797546 [SETA-based storytelling]

These authors create innovative organisational training artefacts based on storytelling and leverage design thinking through design science techniques to help 1700+ employees better understand and improve their security and privacy intentions and behaviours related to online self-disclosure. Their use of a longitudinal but randomised and controlled field experiment focused on SETA with actual employees is a strong demonstration of ecological validity.

Sheffler et al. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1808539 [badges for bikes]

This study provides an innovative field experiment that shows one of many ways gamification can positively influence and contribute to both the original contexts of wellness and sustainability efforts. Moreover, the authors dig deeply into the artefact of badges and demonstrate how they can be more thoughtfully conceptualised and operationalised. By using a field experiment of actual use, they also demonstrate ecological validity in helping address sustainability issues.

Amo et al., https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1808540 [leaderboards article]

This study provides an original contribution by taking a fresh and deeper look at the effects of points and leaderboard design artefacts on user engagement and performance growth. They do so using a large-scale natural experiment over 300 days with a working interactive technology exhibit in a museum to achieve objective, ecologically valid, and long-term data, measures, and theoretical insights in an original context.

We thus conclude by issuing a broad appeal for a greater willingness in the IS research community to understand and engage in interdisciplinary research discourses, including but not limited to the IS–gamification discourse. We also need to better understand the discourses in the research communities in which we already participate, because much of this activity is not discursive but reflects one-sided conversations. Such research conversations thwart understanding and miss compelling opportunities. Good and interesting research discourse starts with good and interesting conversations, and in science, this is increasingly found in interdisciplinary discourse, not siloed, politicised, or protective disciplinary discourse.

Our collective involvement with other discourses, like gamification, is a strength, not a weakness, as this interchange informs theory and research and makes IS an interdisciplinary discipline that is not high paradigm, arid, and rigid, as our sister business disciplines of accounting and finance have become. Let us not forget that research and publication in such disciplines is a punishing, demoralising process, yielding research that too frequently puts a premium on “rigor over relevance” (Benbasat & Zmud, Citation1999) and thus is more likely to end up on dusty shelves with little influence on research or practice.

By contrast, the IS discipline is replete with promising and exciting blue-ocean opportunities, which make it a gratifying place for research and engagement with practice, and we can think of no better example than the emerging IS–gamification discourse. This is particularly true given that meme culture, gaming, pop culture, and the like are changing metaphors, artefacts, affordances, and general communication in ways that have direct relevance to all IS and organisation design – not just gamified IS. This should be highly concerning to those smugly hiding behind “serious systems” in their research or practice, because misapplication of key aspects of meme culture or metaphors alone can have culturally disastrous consequences for design, implementation, management, governance, and policy. Scientists do not dictate or provide value judgements on culture and communication trends; instead, scientists account for them and study them. No amount of seriousness or smugness in the face of the globalised gaming and meme culture will change the fact that they are culturally embedded in contextualised forms everywhere in the world and rapidly changing communication. Wearing Luddite or “culturally superior” blinders to filter out these cultural and artefactual influences while researching, managing, or practising IS will likely cause the same kinds of negative results as does classic cultural misappropriation in IS or designing and deploying systems without proper engagement with the actual users.

In conclusion, we emphasise that the best conceptualisation, theorisation, and science never occur in isolation. Instead, we advocate a more humble “standing on the shoulders of giants” approach to theory, and we can start with Aristotle and Darwin.xxii This philosophy has been publicly embraced by other luminaries such as Sir Isaac Newton and Stephen Hawking, and we argue that it is the widely embraced philosophy of how science is supposed to work within and between scientific communities. We urge the use of the same approach in research and theorisation. Pragmatically, this means there is no need for researchers to reinvent the wheel, and we need to embrace and foster our connection with other discourses.

Hence, we assert that our impressive interdisciplinary connection to other disciplinary discourses is not a weakness, but a strength. Not everything in our discourse needs to be new and novel – nor should it be – but what we reuse, build on, or create should be “better” than the status quo if we want to contribute to broader scientific progress or meaningfully inform practice. Collectively, IS researchers have more “giants” to stand on than do researchers in most other disciplines, especially those of a high-paradigm, staid nature that are theoretical sinks. Thus, we have more solid theoretical artefacts to build on. We thus suggest that IS theories cannot be independent of other disciplines and discourses but should be coherent with them and often informed and inspired by them. We assert that this pattern is true of all great theories and foundational to proper scientific practice that extends from concepts and constructs to theories, methods, measures, analysis techniques, standards of evidence, and the underlying discourse that unifies these around a discipline’s shared questions of interest.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (550.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2011). Generating research questions through problematization. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 247–271. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0188

- Alvesson, M., & Sandberg, J. (2013). Constructing research questions: Doing interesting research. Sage.

- Bacharach, S. B. (1989). Organizational theories: Some criteria for evaluation. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 496–515. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308374

- Bai, S., Hew, K. F., & Huang, B. (2020). Does gamification improve student learning outcome? Evidence from a meta-analysis and synthesis of qualitative data in educational contexts. Educational Research Review, 30(June), Article:100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100322

- Benbasat, I., & Zmud, R. W. (1999). Empirical research in information systems: The practice of relevance. MIS Quarterly, 23(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/249403

- Blohm, I., & Leimeister, J. M. (2013). Design of IT-based enhancing services for motivational support and behavioral change. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 5(June), 275–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-013-0273-5

- Bogost, I. (2014). Why gamification is bullshit. In S. P. Walz & S. Deterding (Eds.), The gameful world: Approaches, issues, applications (pp. 65–79). MIT Press.

- Boss, S. R., Galletta, D. F., Lowry, P. B., Moody, G. D., & Polak, P. (2015). What do systems users have to fear? Using fear appeals to engender threats and fear that motivate protective security behaviors. MIS Quarterly, 39(4), 837–864. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.4.5

- Boudreau, M.-C., Gefen, D., & Straub, D. W. (2001). Validation in information systems research: A state-of-the-art assessment. MIS Quarterly, 25(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250956

- Ching, M. K. (1993). Games and play: Pervasive metaphors in American life. Metaphor and Symbol, 8(1), 43–65. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327868ms0801_3

- Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0486

- Currie, W. (2009). Contextualising the IT artifact: Towards a wider research agenda for IS using institutional theory. Information Technology & People, 22(1), 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/09593840910937508

- Doty, D. H., & Glick, W. H. (1994). Typologies as a unique form of theory building: Toward improved understanding and modeling. Academy of Management Review, 19(2), 230–251. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1994.9410210748

- Earl, M. (2001). Knowledge management strategies: Toward a taxonomy. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045670

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Foucault, M. (1972). Archaeology of knowledge and the discourse on language. Pantheon Books.

- Gaskin, J. E., Lowry, P. B., & Hull, D. (2016). Leveraging multimedia to advance science by disseminating a greater variety of scholarly contributions in more accessible formats. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17(6), 413–434. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00430

- Gordon, B. (2015) Will 80% of gamification projects fail? Giving credit to Gartner’s 2012 gamification forecast. Centrical. Retrieved from June 6, 2020, https://centrical.com/will-80-of-gamification-projects-fail/

- Hamington, M. (2009). Business is not a game: The metaphoric fallacy. Journal of Business Ethics, 86(4), 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9859-0

- Hassan, N. R. (2014, December). Useful products in theorizing for information systems. Thirty-Fifth International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2014) (pp. 14–17). Auckland, New Zealand: AIS.

- Hassan, N. R., & Lowry, P. B. (2015, December). Seeking middle-range theories in information systems research. Thirty-Sixth International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2015) (pp. 13–18). Fort Worth, TX: AIS.

- Hassan, N. R., Mathieson, L., & Lowry, P. B. (2019). The process of information systems theorizing as a discursive practice. Journal of Information Technology, 34(3), 198–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268396219832004

- Hull, D. M., Lowry, P. B., Gaskin, J. E., & Mirkovski, K. (2019). Research opinion: A storyteller’s guide to problem-based learning for information systems management education. Information Systems Journal, 29(5), 1040–1057. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12234

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45(April), 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.013

- Lee, A. S., Thomas, M., & Baskerville, R. L. (2015). Going back to basics in design science: From the information technology artifact to the information systems artifact. Information Systems Journal, 25(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12054

- Liu, D., Santhanam, R., & Webster, J. (2017). Toward meaningful engagement: A framework for design and research of gamified information systems. MIS Quarterly, 41(4), 1011–1034. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.4.01

- Lowry, P. B., Dinev, T., & Willison, R. (2017). Why security and privacy research lies at the centre of the information systems (IS) artefact: Proposing a bold research agenda. European Journal of Information Systems, 26(6), 546–563. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41303-017-0066-x

- Lowry, P. B., Gaskin, J. E., & Moody, G. D. (2015). Proposing the multimotive information systems continuance model (MISC) to better explain end-user system evaluations and continuance intentions. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 16(7), 515–579. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00403

- MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2011). Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 293–334. https://doi.org/10.2307/23044045

- Markus, M. L., & Silver, M. S. (2008). A foundation for the study of IT effects: A new look at DeSanctis and Poole’s concepts of structural features and spirit. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 9(10), 609–632. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00176

- Mirkovski, K., Gaskin, J. E., Hull, D. M., & Lowry, P. B. (2019). Visual storytelling for improving the dissemination and consumption of information systems research: Evidence from a quasi-experiment. Information Systems Journal, 29(6), 1153–1177. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12240

- Möring, S. (2013) Games and metaphor–A critical analysis of the metaphor discourse in game studies. Doctoral Dissertation, IT University of Copenhagen, Center for Computer Games Research(https://sebastianmoering.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/20140624-SM-thesis-proofread-b.pdf; accessed September 2, 2020).

- Oswick, C., Fleming, P., & Hanlon, G. (2011). From borrowing to blending: Rethinking the processes of organizational theory building. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 318–337. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0155

- Posey, C., Roberts, T. L., Lowry, P. B., Bennett, R. J., & Courtney, J. (2013). Insiders’ protection of organizational information assets: Development of a systematics-based taxonomy and theory of diversity for protection-motivated behaviors. MIS Quarterly, 37(4), 1189–1210. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2013/37.4.09

- Rousseau, D. M., & Fried, Y. (2001). Location, location, location: Contextualizing organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.78

- Santhanam, R., Liu, D., & Shen, W.-C. M. (2016). Research Note—Gamification of technology-mediated training: Not all competitions are the same. Information Systems Research, 27(2), 453–465. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2016.0630

- Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. I. (2015). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 74(February), 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2014.09.006

- Silic, M., & Lowry, P. B. (2020). Using design-science based gamification to improve organizational security training and compliance. Journal of Management Information Systems, 37(1), 129–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2019.1705512

- Simon, H. A. (1996). The sciences of the artificial. MIT Press.

- Son, J.-Y., & Kim, S. S. (2008). Internet users’ information privacy-protective responses: A taxonomy and a nomological model. MIS Quarterly, 32(3), 503–529. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148854

- Treiblmaier, H., Putz, L.-M., & Lowry, P. B. (2018). Setting a definition, context, and research agenda for the gamification of non-gaming systems. Association for Information Systems Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction (THCI), 10(3), 129–163. https://doi.org/10.17705/1thci.00107

- Van de Ven, A. H. (1989). Nothing is quite so practical as a good theory. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 486–489. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308370

- Van de Ven, A. H. (2007). Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540

- Watson, J. D. (1968). The double helix: A personal account of the discovery of the structure of DNA. Atheneum.

- Weick, K. E. (1989). Theory construction as disciplined imagination. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 516–531. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308376

- Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 490–495. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4308371

- Whetten, D. A. (2009). An examination of the interface between context and theory applied to the study of Chinese organizations. Management and Organization Review, 5(1), 29–56.

- Zahra, S. A. (2007). Contextualizing theory building in entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(3), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.04.007