ABSTRACT

This study presents an Information Systems (IS) research methodology for the conduct of critical research into sustainable development that encompasses the objectives of socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable economic growth. The specific context is the application of critical research in the problem definition phase of IS Design Science Research for sustainable development. The paper guides IS research through problem scenarios of unsustainable development where power can distort truth and corrupt the public discourse in the furtherance of their ambitions. The methodology provides a structured approach to engage in inquiry of topics which are by their nature, deceptive and opaque. The methodology enables research inquiry encompassing societal topics, macro-social issues related to sustainable development and the application of nomothetic inquiry to address systemic problems. The paper concludes with illustrative examples of outcomes from the application of the prescribed methodology. The study provides an IS response to systemic social and environmental challenges by identifying the routes to transformation which in turn inform the design of IS solutions. Consequently, the study lays a foundation for IS engagement in socially responsible design science research.

1. Introduction

The novelty of this study lies in its practical methodology for conducting critical Information Systems (IS) research into sustainable development issues, as a first phase in socially responsible design science research. Contextually, the methodology is applicable for a domain of research inquiry encompassing societal topics, macro-social issues related to sustainable development and the application of nomothetic inquiry to address systemic problems. These inquiry domain characteristics are expanded on in the section entitled, “Assessing the Applicability of the Methodology”.

The paper is positioned at the intersection of an ethos described as “Socially Responsible Design” (SRD) and the “Design Science Research” (DSR) paradigm, while it focuses on the imperatives of “Sustainable Development”. In order to give effect to DSR within the domain of sustainable development with its implied SRD convictions, the paper prescribes a methodology for “Critical Research Theory” (CRT). Specifically the methodology is intended as the means for initiating DSR in the sustainable development domain. It might therefore be misconstrued as being neither relevant to the discipline of IS nor specific to the practice of DSR. However, if the IS discipline is to transcend the confines of the organisational context within which it is predominantly perceived, it requires the means to grapple with research issues of the social domains. If it chooses to limit itself to being the enabling party for solutions originating in other disciplines, it deprives itself of opportunities to engage in understanding problems and formulating solutions devised under an IS ontology. Conversely, if it steers away from methodologies that directly engage the social domains, it restricts itself to formulating solutions that are insensitive to social issues. In order to breach this perceptual barrier, it needs to unshackle forward-looking research paradigms like DSR in collaboration with the socially transformational objectives of CRT. Such a forward-looking and expansive stance by IS will open the opportunities for initiating multidisciplinary research that enhances the role of IS research and serves to guide DSR endeavours in the sustainable development domain. In these contexts, the CRT methodology of this study provides a focused contribution to DSR endeavours within the IS discipline.

The paper is targeted at IS practitioners, including researcher, designers, programmers, engineers and the like, who are not only engaged in artefact development but who also seek to comply with the ethos of sustainable development. It accesses research opportunities beyond the more familiar confines of problems defined in the organisational domain, into the wider social and environmental domains. It serves to promote responsible practices in pursuing technological artefact creation (design and development) by bringing focus to bear on the potential social and environmental impacts of their application, during the early stages of design.

In this context, the term “artefact” means a practical, IS-based artefact for enabling processes and actions. While design science research in the IS field may be applied to the design and creation of various theoretical artefacts such as designs, methodologies and theoretical concepts, these would all be viewed as potentially intermediate steps or contributing (kernel and mid-range) theory that ultimately lead to the design and development of the practical, enabling artefact. This concept of the artefact is referred to as “the IT artefact” by Orlikowski and Iacono (Citation2001) and “the functioning, testable and observable artefact” by W. Kuechler and Vaishnavi (Citation2012). In practical terms, the concept of the artefact ranges from core technical IS functions that combine ICT hardware and software to perform single tasks (such as a search algorithm or security protocol), to the complex assemblies of these core, functional components into software-coded processes for interacting with, for and about humanity in the form of information systems. These information systems may be judged to be socially and environmentally either negative or positive when assessed against the values implicit in social responsibility.

This study has the additional ambition of introducing and clarifying the concepts and language pertaining to research directions that might be less familiar in IS practice, such as social responsibility, critical research and sustainable development. Consequently, in addition to the development and description of the CRT methodology, large sections of this paper are devoted to explanations of these key contextual concepts. It achieves these objectives in response to the research question; “How may critical IS research be conducted to fulfil the requirements of Socially Responsible Design?”

This question arises from reflection on the current state of our world from the IS perspective where we are increasingly aware of social and environmental circumstances and threats through communications facilitated by information and communications technologies (ICTs) but where we are not yet urgently engaging these problems through the application of ICTs.

While the topic is an emotive one, this paper attempts to present the methodology in an objective, prescriptive fashion of guidelines embellished with nuances and warnings appropriate for the subject matter, thereby translating the methodological steps and outputs into implications for ICT design. Striking examples of these outputs are presented in the final third of the paper.

The main objective of this paper is therefore to design a methodology for applying critical research in the pursuit of socially responsible design science research in the IS field. The outcome of this design study is an artefact complying with the definition of methodology;

“the study—the description, the explanation, and the justification—of methods, and not the methods themselves”. (Kaplan, Citation1964, p. 18)

In Kaplan’s (Citation1964) terms, the aim of methodology is to “describe and analyse … methods, throwing light on their limitations and resources, clarifying their presuppositions and consequences … to help us to understand, in the broadest possible terms, not the products of scientific inquiry but the process itself”. (Carter & Little, Citation2007, p. 23).

The resulting methodology facilitates IS research into societal and power structures that are identified through influences of demographics, economics and politics. It complies with the defining aspects of critical research that distinguishes it from the more widely adopted interpretivist and positivist paradigms and it seeks to play a pivotal role in socially responsible design through revealing opportunities arising from the sustainable development imperative.

However, it also has two secondary objectives. The first is to position the methodology firmly within the design science research paradigm and the second is to provide a critical and summative explanation (to convey an evaluation of the concept) of sustainable development as the basis and motivation for this study.

Achieving the primary objective provides practical responses to three prevailing research situations in the IS domain; Firstly, the paper is a practical guide for engaging in critical research theory to complement the numerous IS studies devoted to its theoretical aspects, secondly the paper provides an approach to performing the “conceptual investigation” phase of the tripartite methodology for Value Sensitive Design (Friedman et al., Citation2008), and thirdly the methodology gives practical effect to multinational state (EU & UK) policies developed to incentivise and control research and innovation in a socially responsible manner. Papers by Stahl et al. (Citation2013) and Von Schomberg (Citation2011) expand on the imperative arising from these policies to practice design and innovation in a socially responsible manner and this paper’s methodology builds on the principles revealed in those studies.

1.1. Study layout

The paper proceeds with an explanation of the methodology’s positioning within the broader arena of design science research. This is followed by a description of sustainable development through the tracing of events and circumstances that have led to the dire situation of unsustainable development and the need for urgent action to combat it. Then there is an explanation of the development of this study itself which applies the “Theory Development in Design Science Research” methodology of B. Kuechler and Vaishnavi (Citation2008) in which a new methodology is created by the testing and refinement of “design theory” against “kernel theory” and “mid-range theory”. The paper proceeds further with an introduction of the specific mid-range theories used to reflect and refine the designed methodology of this paper and is followed by exegetical commentaries on the kernel theories that form the foundation of knowledge upon which this methodology (design theory) is constructed. These kernel theories include;

“the principles for conducting critical research” that provide the guidance for constructing a methodology compliant with the paradigm,

an “explanation of the selection of relevant critical theories that provide a philosophical basis for the data collection and analysis strategy of the prescribed methodology and

an explanatory discussion concerning “the identification and selection of a value position” to provide the ethical stance required for a critical research undertaking.

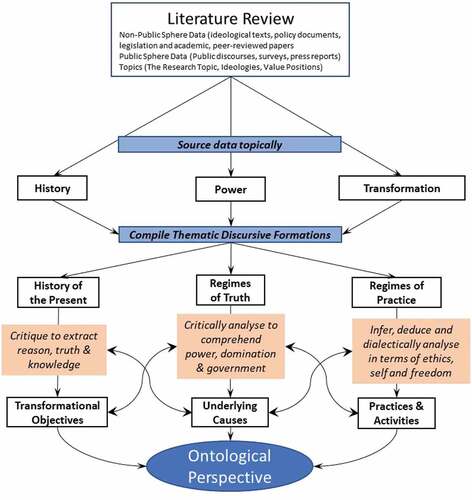

Thereafter, the design theory, as the method of execution (methodology), is explained as a three part process, including a diagrammatic model as a visual aid. The design theory is illustrated with examples extracted from the mid-range theories against which the design theories are evaluated and improved. The concluding remarks are pre-empted by a discussion on some of the obstacles to actually practicing CRT within the IS discipline and questioning the likelihood of this methodology resulting in the design and development of technologies to combat abuses of power and social injustice.

2. The design science research context

The justification of including a CRT research step within the DSR paradigm is explained in this chapter. Firstly, a justification is provided for the possibility of positioning a CRT-based step within accepted DSR processes. The second section explains this study’s alignment with the concept of SRD which establishes the social justice orientation that invites a CRT-based approach to DSR. The third section sets out to clarify the role of CRT in Socially Responsible Design Science Research by highlighting the suitability of CRT for delivering on SRD objectives. This section also addresses the difficulty of applying CRT in the prevailing organisational orientation of the IS discipline while strengthening the case for CRT as an essential first step in Socially Responsible Design Science Research. The final section discusses a taxonomy for assessing the suitability of the application of this methodology. It does so by defining the scope of research topics that the methodology may engage with, within the wider variety of situations and problems that could motivate DSR.

2.1. Justifying a CRT-Phase within design science research

This section explains the rationale behind the primary objective of “designing a methodology for applying critical research in the pursuit of socially responsible design science research in the IS field”. DSR seeks to contribute to the understanding of created, rather than natural phenomena (Hevner et al., Citation2004; Howcroft & Trauth, Citation2005; Lee, Citation2010) while accumulating knowledge in the process of construction and evaluation of artefacts (Vaishnavi & Kuechler, Citation2004).

In applying DSR as the research method, a researcher would likely adopt one of the guiding methodological frameworks. Reason dictates that these frameworks begin with processes aimed at defining and understanding a problem, as well as the determination of a solution direction. The design process model developed by Takeda et al. (Citation1990) refers to these initial steps as the “Awareness of Problem” and “Suggestion”. Frameworks developed by Hevner et al. (Citation2004), Purao (Citation2002), and Gregg et al. (Citation2001) proceed similarly. The Design Science Research Methodology (Peffers et al., Citation2007), describes these initial steps as; “Identify Problem & Motivate” and “Define Objectives of a Solution”.

The pervasiveness of IS throughout society in general as well as in organisations, implies that IS research is ideally positioned to address sustainable development issues that see an overlapping of phenomena of interests, methods of investigation (Vaishnavi & Kuechler, Citation2004) and an overlapping of hard sciences, economics and social sciences (Avison & Elliot, Citation2005). Consequently, there are often opportunities for innovation and artefact design in IS where it is positioned to provide the means to solutions. “Whereas natural sciences and social sciences try to understand reality, design science attempts to create things that serve human purposes”. (Simon, Citation1969, p. 55). In order to create effective solutions for problem scenarios in the sustainable development domain, logic dictates that the initial steps of understanding a problem and determining a route to a solution would employ forward-looking research paradigms such as CRT, seeking to address social and environmental challenges to achieving social emancipation through transformation. Critical research embraces fundamental criticism (Etzioni, Citation1968) tempered by an explicit value position to engage effectively with the social and ethical aspects of problems. The real world problems that manifest in the poor provision of social services and environmentally unsustainable systems are social problems seeking transformative solutions. They would therefore necessitate a critical research inquiry to achieve deep understanding of and forward-looking solutions to those problems. As CRT-based research is differentiated by the elements of critique and transformation in addition to interpretive research methods (Myers & Klein, Citation2011), its application meets the imperative for identifying and conceptualising transformational objectives. These transformational objectives in turn provide focus and impetus for innovation, either in the design of new artefacts or in the application of existing artefacts. Under the presumption that many problems of macro-social and environmental issues included in the sustainable development domain would require socially transformative solutions; a critical research phase would ideally underpin many SRD endeavours.

2.2. Alignment with socially responsible design

This section explains the correlation between sustainable development and “the pursuit of socially responsible design science research” referred to in the primary research objective. Alongside other human endeavours and social activities, an objective of compliance with the ethos of sustainable development motivates the need for research disciplines to develop and utilise methodologies that provide alignment with a socially responsible pursuit of economic activities whereby broader stakeholders’ interests are not abrogated in favour of returns to shareholders. Socially Responsible Design (SRD) focuses attention on the products, environments, services and systems that can alleviate real-world problems to improve quality of life through purposeful design. SRD encapsulates the central roles that designers might play across the various disciplines to use their specific skills for addressing problems concerning the macro-social issues (crime, education, government, health, fair trade, social inclusion and economic policy) and macro-environmental challenges (poverty, climate change, energy, pollution and rapid population growth in developing countries) (Dayey et al. Citation2007). The activities and structures deployed by states in provisioning services for societal needs arising from these macro-social issues, in a socially inclusive fashion, represent a manifestation of the practical dispensation of social justice. Of equal social significance, the recognition of issues and the collaborative, multidimensional action to address macro-environmental challenges, represents the key to a sustainable world. This study is aligned with the SRD objectives.

2.3. The role of critical research in SRD

This section positions the role of CRT within socially responsible design science research. The methodology for CRT developed in this study serves as “a practical guide for engaging in critical research theory to complement the numerous IS studies devoted to its theoretical aspects”. In the context of the overarching research question about the means and methods for conducting socially responsible design science in IS, the focus for this paper narrows onto the conduct of critical research as an integral and indispensable first step for pursuing design science research for social inclusion and sustainable development.

The practice of critical IS research is characterised as “a wide range of diverse research endeavours aimed at revealing, criticising and explaining technological developments and the use of IS in organisations and society that, in the name of efficiency, rationalisation and progress, increase control, domination, and oppression, and produce socially detrimental consequences” (Cecez-Kecmanovic, Citation2007, p. 1446). This characterisation reveals a context and understanding of problems that motivate for teleological responses from the IS discipline that in turn provides impetus for critical research into the socially responsible innovation and utilisation of IS. However, in spite of numerous studies having been produced on the principles and theories for conducting critical IS research, its application remains relatively rare and this state of low adoption has been a prevailing cause for concern (Brooke, Citation2002; Cecez‐Kecmanovic et al., Citation2008; Howcroft & Trauth, Citation2005; Kvasny & Richardson, Citation2006; McGrath, Citation2005; Myers & Klein, Citation2011; Palvia et al., Citation2015; Truex & Howcroft, Citation2001).

Aligned to the SRD ethos, purposefully designed IS solutions could harness the participation and voices of individuals within a context of communities and environments formed through their affiliation to common social and environmental causes, relating to each of the macro issues.

In spite of their pervasiveness, the potential for ICTs to be utilised to advance either the provision of socially inclusive services or collaborative action for sustainable development, is yet to be realised. To achieve this, the roles of the powerful and societies in general would require alignment for common purposes and goals related to achieving the maximum social benefit. Indicative of the failure of this alignment, the effective delivery of government services to citizens have been faced with challenges of accessibility, trust issues on both sides, legacy structures & attitudes and costs that remain persistent topics of research and reporting in global organisations like the UN and EU (as evidenced by results from popular search engines). While the roles of ICTs in collaborative actions between states and across societies for sustainable development solutions, are not yet apparent. Palvia et al. (Citation2015) found only 37 out of 2881 papers published in 7 top ranked journals over the decade 2004 to 2013, focused on the topic of E-government and further searches failed to locate any studies concerning IS solutions for Government Services to Citizens. This situation represents an underexploited field of research opportunities for the IS discipline to develop enabling artefacts. The term “enabling artefacts” specifically refers to practical artefacts of a technical nature that enable identified solutions.

2.4. Assessing the applicability of the methodology

The methodology for critical research theory developed in this paper is positioned as an initial process within socially responsible Design Science Research (DSR). However, DSR as a research paradigm may be applied to a wide diversity of purposes with a variety of methodologies and mental models. A researcher would have to be able to determine to what extent this approach to DSR or any other methodology, is appropriate for a research undertaking. Structures of categorisation to navigate through possible approaches would make such a determination simpler. A categorisation strategy, dubbed the “DSR genre framework”, for dealing with variety and complexity of DSR methodologies was initiated to provide a means of distinguishing between different approaches associated with different types of artefacts, as an aid to reviewers and editors in their assessment of DSR articles in the midst of this challenging variety (Peffers et al., Citation2018). However, in the context of this paper it is predetermined that the DSR approach addresses a single type of artefact and that CRT will be applied for the problem definition and solution identification phase, irrespective of the DSR methodology being applied. Therefore, a set of assessment criteria for CRT rather than DSR is required. As CRT has a social focus extending beyond the boundaries of the usual organisational focus of IS research, the social sciences were interrogated for examples of the treatment of qualitative data for categorisation as criteria. These data are analysed by applying principles of inductive reasoning and determining categorisation through code types for guiding data analysis and interpretation. “These code types (conceptual, relationship, perspective, participant characteristics, and setting codes) define a structure that is appropriate for generation of taxonomy, themes, and theory” (Bradley et al., Citation2007 p. 1).

Accordingly, a taxonomy for “Critical Research Theory Focus” is devised from the scoping criteria of the methodology developed in this paper. These criteria or code types are compiled to aid researchers in determining if the methodology is appropriate for the “Problem Definition and Solution Identification” stage of their DSR projects.

The first criterium considered is the breadth of the social domain of the inquiry which depends on whether the focus of the research topic is defined as an organisational or societal problem. Some DSR methodologies in IS prescribe an organisational setting, such as the Design Science Research Methodology (Peffers et al., Citation2007) and Action Design Research (Sein et al., Citation2011). However, a researcher may rest assured that not only are there other DSR methodologies which have not implied such limitations, such as Explanatory Design Theory (Baskerville & Pries-Heje, Citation2010; Niehaves & Ortbach, Citation2016) and Design-oriented IS research (Österle et al., Citation2011; Winter, Citation2008) but that those methodologies which do imply those limitations may also be adapted for different situations, provided such adaptations do not compromise their methodological integrity.

Aside from the societal vs organisational code type, the devised “Critical Research Theory Focus” taxonomy lists 3 further related code types for categorising the domain of focus for a research topic. These interrelated criteria, detailed hereunder, and their relevance are expanded upon further in the following section on Socially Responsible Design and in the prescribed methodology.

Critical Research Theory Focus;

Social domain breadth; societal or organisational (societal or the broader community may include organisations but organisational is restricted to the organisational domain)

Problem domain; macro or micro-social issues (For example, a Healthcare System versus a Hospital)

Research Goal; nomothetic (description of generally applicable problems and solutions) or ideographic (explanations obtained from individuals)

Topic Dominance; systemic or specific (a pervasive reality defined by human imposed circumstances rather than a specific, isolated situation, such as Climate Change vs problems arising from a snow storm in Texas – The specific may result from the systemic but not vice versa)

Applying the above taxonomy, the domain of Critical Research Theory Focus for this methodology is defined as; societal topics, focused on macro-social issues related to sustainable development, engaging in nomothetic inquiry to address systemic problems.

3. Sustainable development

3.1. The history and mechanism of unsustainable development

The following critique of the causes for the crisis of unsustainable development and assessment of reactions to it, serve to justify this study as a contribution to the cause of sustainable development. The concept of sustainable development arises from the reaction to human activities and their impacts on the natural environment. The start of the industrial revolutions was a pivotal point where mankind developed the means to harness various forms of thermal and hydro energy to perform work. While there is much speculation and conjecture about the causes and effects of the industrial revolution (Hudson, Citation2014), what is evident is that from that point onwards, the balance between the utilisation and regeneration of the natural environment that had been ensured by the limits on the capacity for work of the muscle power of man and his beasts of burden, were under threat. Along with the discovery of various chemicals and compounds, there were abounding innovations of mechanisms (Ashton, Citation1997) that consumed and continue to consume finite raw materials in production processes of artefacts designed to not only meet our needs and increase our comfort but also inflame our desires for unnecessary consumption (Southerton, Citation2011). Control of the sourcing and utilisation of raw materials and the mechanisms of production represents power and wealth. These sources of power attracted and continues to attract the traditionally powerful in the form of the previously endowed, nation states and political movements as well as a continuum of newcomers in the form of enterprises and investment collaborations able to profit from innovations and managerial efficiency (Hall, Citation2015).

With the birth of Capitalism, a mechanism for financially fuelling these activities was devised in the form of stock exchanges that facilitate the potentially profitable trading of and investment in every kind of enterprise arising from industrialisation and which in turn drives the speculation and risk taking that support new discoveries and innovations (Baumol, Citation2002). Free and properly regulated markets provide an egalitarian and efficient mechanism for every investor, large and small, to participate in the economic returns generated by enterprises.

However, throughout most of the 20th century, espoused economic theory supported the dictum that the prime objective of an enterprise was the maximisation of returns to shareholders. In a distortion of the egalitarian and socially just ethos of a balanced free-market mechanism, a profit-maximising-at-any-cost orientation became the norm for many enterprises (Primeaux & Stieber, Citation1994). Profit maximisation “has almost come to be regarded as equivalent to rational behaviour, and as an axiom, which is self-evident and needs no proof or justification” (De Scitovszky, Citation1943, p. 57). This economic principle continues to be promoted by educational institutions under the influence of the powerful who in turn became their benefactors (Ghoshal, Citation2005; Snelson-Powell et al., Citation2016). This distorted ethos encouraged increasing investment in profit maximising enterprises that generate high short-term returns from activities that invariably entail deferred or unaccounted for costs and consequences. Therefore, even when it is predictable that an enterprise’s products or processes cause harm to society or the environment (Clark, Citation1973), regulatory controls do not outlaw investment in them and redress or compensation for negatively affected parties is made legally onerous and expensive.

Proponents of the free market ideal resist any form of regulation in the belief that the forces at play ensure a naturally self-correcting mechanism based on the market forces establishing the “right price” for anything but opponents of this laissez-faire ethos point out that regulation is required to prevent harmful exploitation through market collusion, price distortions and transaction costs (Orlitzky, nd.). At its inception, the Capitalist system arose through interventions of the British state to dismantle feudal institutions and protect manufacturers through tariffs and other subsidies. The historian Polanyi (Citation1944 p.71, 132) observes that “ … . there was nothing natural about laissez-faire; free markets could never have come into being merely by allowing things to take their course … … laissez-faire was enforced by the state”. The imposition of capitalism was a double movement; one movement to establish capitalism itself but the other was a counter-movement to establish social protection through legislation and restricted associations (Polanyi, Citation1944).

Arising from the establishment of Capitalism and its ethos of private ownership of the means of production, legal transactions for investments into enterprises were legislated by states and as a consequence, an “investment industry” phenomenon arose to manage and facilitate investments on behalf of corporations and citizens alike. In order to serve the needs of its clients, this industry creates complexity and terminology that facilitates opaqueness and unaccountability, screened by mechanisms and structures that enable funds of anonymous investors to be applied, through 3rd party agents, via investment instruments constructed to achieve specific returns, to both harmful and harmless enterprises alike. “The use of multiple funds has evolved in the investment management industry – with a single holding company often having over 100 funds. The investment management industry decentralises its funds and often uses third-party entities for numerous operating responsibilities. They have decentralised boards and managers”. (W. A. Wallace, Citation2004 p. 270). In view of the apparent impotence of state or international legislation to regulate harmful capitalist activities and protect society, an inscrutable mechanism for enabling systemic profit maximisation is embedded in investment activities. This exploitative situation demands effective regulation by governments to provide protection for society from the detrimental effects of investments into harmful enterprises. However, the (Power) relationships between powerful parties appear to undermine efforts for protection. This state of affairs is evidenced by the continuing unfettered investments into harmful industries that have caused and continue to cause pollution, habitat destruction and environmental degradation, climate change, human exploitation in 3rd World countries and extreme social inequality. In reaction to insufficient regulation on investments, Christian church groups in the UK, Europe and the USA established movements for moral and ethical investment practices in the early 1900s (Louche & Lydenberg, Citation2006). These were the precursors of the modern Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) funds formed in 1970s and 80s, with names such as Friends Provident and Stewardship Fund (UK), Het Andere Beleggingsfonds (Netherlands), Ansvar Aktiefond Sverige (Sweden), KD Fonds Ökoinvest (Germany) and Nouvelle Strategie Fund (France) as well as the Pax World Fund and the Dreyfus Third Century Fund (USA) (Louche & Lydenberg, Citation2006).

The influences of powers that control key production inputs, especially raw materials and natural systems, overlap ideological and national boundaries in their quest to keep exploiting finite resources and the natural environment for maximised profit. While the consequences of industrialisation has seen an improved general standard of living, enhanced infrastructure development in well-managed societies and a persistent growth in population numbers (Southerton, Citation2011), it has also resulted in the highly polluted and damaged environments, looming mass extinctions of plants and animals and accelerated climate change that threaten to harm the support systems for life on our planet.

3.2. Reaction: warnings and push back

As direct human involvement in industrial activity on the planet was reaching its peak (ca. 1970), concerned thinkers in the form of the Club of Rome (formed in 1968 by Italian industrialist and economist, Dr Aurelio Peccei and the OECD’s Dr Alexander King) produced the first edition of the report entitled “The Limits to Growth” (De Rome & Meadows, Citation1972).

This study and report applied the System Dynamic Modelling (Forrester, Citation1961) techniques developed by Jay Forrester to produce models that illustrated how the Earth’s many systems and natural resources cannot be sustained under the impact of mankind’s consumptive activities (Colombo, Citation2001). This ground-breaking report received massive pushback from academic, industrial, national, religious and private wealth interests that effectively set out to discredit its message and warnings. The criticisms focused on various aspects of the model and the underlying assumptions, without ever advancing an alternative scenario except to imply that man’s ingenuity would prevail.

The report focused on five factors, namely population growth, industrial activity, agricultural activity, pollution and the rate of depletion of inherited natural resources – that we are living off capital instead of income.

In 2018, on the 50th anniversary of the formation of the Club of Rome, the latest edition of the report entitled “Come On!” (Von Weizsäcker & Wijkman, Citation2018), warned about the same issues but with even greater urgency. The report in turn, supported by empirical data, discredits entirely the detractors of the initial report of 1972 and shows that each one of the dangers warned about in the original report were proceeding as predicted in a scenario of inaction. In effect, 50 valuable years were wasted by world leadership on inaction (except for conferences and resolutions) against the consequences of perpetual economic growth policies and practices.

3.3. Achievements to date?

Internationally coordinated reactions to these looming and growing threats started five decades ago with the United Nations which culminated in a lengthy process of conferences and formulations of resolutions and policy. These conferences began in 1972 when governments met in Stockholm, Sweden for the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, to consider the rights of the family to a healthy and productive environment. This was followed over a decade later with the report, Our Common Future (Brundtland et al.,) which was produced by the United Nations’ World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) and defined the concept of sustainable development as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It contains within it two key concepts: The concept of “needs”, in particular, the essential needs of the world’s poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and the idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organisation on the environment’s ability to meet present and future needs.

The concept has since developed beyond the initial intergenerational framework to imply a goal of “socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable economic growth” (Sachs, Citation2015, p. 5).

Following WCED, there has been steady but very slow progress through a multitude of UN conferences during which the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted and subsequently replaced by the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2015. Significantly, the UN-led process that formulated the MDGs, involved collaboration between its 193 Member States and global civil society. The resolution produced is a broad intergovernmental agreement that acts as the Post-2015 Development Agenda.

Ban Ki-moon, the United Nations Secretary-General from 2007 to 2016, warned in a November 2016 press conference that: “We don’t have plan B because there is no planet B”.

However, newly formulated codes of corporate governance (OECD, Citation2015a, Citation2015b), indicated a low key, collective, international intent (not obligation) to either adjust business practices accordingly or accept that sustainable development is a social (not corporate) responsibility. In 2017, the world’s largest economy, the USA, announced its intention to withdraw from the 2015 Paris Agreement on Climate Change Mitigation. This potentially disastrous move was narrowly diverted through the loss of an election by the incumbent president in 2020. Nevertheless, the USA stance has emboldened other states such as Brazil, Australia and India to resist international agreements on climate change and pollution. In 2020, the Convention on Biological Diversity published its report “Global Biodiversity 5” (Secretariat Of The Convention On Biological Diversity, Citation2020) in which it details how the world collectively had failed to reach any of the 20 biodiversity protection targets agreed to at Aichi in Japan, 10 years previously. In addition, the “Living Planet Report 2020” (Almond et al., Citation2020) produced by the World Wildlife Fund reports a 68% decline in the number of wildlife species on Earth between 1970 and 2016. Large and powerful corporations collude with autocratic governments and buy political influence in democracies to stifle attempts to curtail damaging practices for profit. The reluctance of various governments to undertake the necessary changes (Baldwin & Lenton, Citation2020) is analogous to a tobacco addict who is aware of the detrimental consequences of smoking but continues on regardless, while both justifying the habit and ignoring the critics. A dangerous inertia has become the norm.

In desperate situations where leadership fails, history indicates through the records of numerous social revolutions, that problems are resolved at the grassroots level of ordinary members of societies and may be either orderly or chaotic. The orderly alternative involves mass collaboration between societies to oppose those doing harm and focused corrective actions, such as effective research & development (R&D) practices that might drive innovation of solutions. The IS discipline might be uniquely positioned as the means to both facilitate interaction and innovation across disciplines (all disciplines apply IS) and to reach across societies and states to empower positive action. Under the present ambivalence shown by governments and international organisations in supporting the adoption and enforcement of sustainable development practices, the least that could be expected from academic disciplines is to align R&D projects with the sustainable development ethos.

4. Methodological approach for this prescriptive study

The methodological approach adopted for designing this prescriptive framework is based on the exegesis of an IS design science research project conducted by B. Kuechler and Vaishnavi (Citation2008) in which the creation of (prescriptive) design theory through the processes of developing and testing of an IS artefact, is inextricably bound to the testing and refinement of its kernel theory.

The methodology, illustrated below (), is derived from modifications (shaded sections) to an original model developed by Goldkuhl (Citation2004).

Figure 1. Relationships between kernel theory, mid-range-theory and design theory, and the design process (modified from Goldkuhl, Citation2004).

In applying the methodology, the “Kernel theories”, which frequently originate outside the IS discipline and suggest novel techniques or approaches to IS design problems, are often “natural science” or “behavioural science” theories that explain and predict, whereas “Design theories” give explicit prescriptions for “how to do something”. “Kernel theories” provide theoretical grounding for the artefact and “Design theories” are considered as practical knowledge used to support design activities (Goldkuhl, Citation2004). “Mid-range theories” (conceptualised as; “data that are close enough to observed data to be incorporated in propositions that permit empirical testing”, Merton, Citation1949, p. 39) provide empirical data against which the developed artefact (design theories) may be tested and evaluated. The effect of this empirical evidence on the explanatory statements of the design theories, is a refinement process in which those explanatory statements may be revised to accord with the observations of the artefact that take place during evaluation – observations which expose the theories in situ (B. Kuechler & Vaishnavi, Citation2008). This methodology was chosen for this study because it is specifically designed for the purpose of creating new design theory and because it was assessed to be a feasible undertaking. This feasibility was based on the availability of empirical data sourced from a preceding research project that would be a source of mid-range theories as well as providing a tested set of theoretical foundations to serve as kernel theories.

In this application of the B. Kuechler and Vaishnavi (Citation2008) methodology, the various “theories” comprise the following:

Kernel theories;

The principles for conducting critical IS research per Myers and Klein (Citation2011) – these represent guiding principles to assess that the prescriptive methodology produced, conforms to established theory and provides a link between practice and theory.

An explanation of the selection of critical theories, in accordance with one of the aforementioned principles, to provide the basis for inquiry into a specific social problem-based topic of research. Dependent upon the nature of the problem and the inclination or direction of a solution, the researcher may adopt more than one social theory to provide the philosophical foundation of inquiry. The selected social theories inform the epistemological stance of the research, especially with regard to the sourcing and analysis of data.

An explanation of choosing a value position for the research. A further principle of CRT is the adoption of a value position that provides an ethical basis for the inquiry (Myers & Klein, Citation2011). The researcher might, because of an IS ontology, interpret the value position from an IS perspective where the technologies and artefacts of IS are viewed as giving effect to outcomes aligned to the precepts of the espoused value position and the social justice objectives implicit in CRT although both the problem definition and solution identification processes are essentially technology agnostic.

Design theories are the prescriptive statements derived from a process of reflective evaluation of the relationship between the methodological approach applied in the evaluative study and the outcomes of that study. This reflective evaluation seeks to confirm that the cause and effect relationships between research actions and outcomes are accurately understood and articulated in prescriptive statements. Where necessary, refinements are applied in the prescriptive statements wherever shortcomings are identified. Thus, knowledge is accumulated in the process of construction and evaluation of the artefact (Vaishnavi & Kuechler, Citation2004).

Mid-range theories are obtained from prior reference study/studies in which the methodology was applied (and possibly originated). These studies serve as evaluative studies. Examples from prior studies are used to illustrate, assess and reassess the outcomes of the prescriptive processes articulated in the methodology and are the sources of empirical data in the research process.

Based on reflection and analysis of the evaluative study, this paper develops a prescriptive theory for guiding critical research into social domains that transcend the realms of organisations and the enterprise, into societal structures that are identified through influences of demographics, economics, environmental factors and politics. Specifically, the evaluative study illustrates the prescribed methodology’s effectiveness for conducting CRT into a social service-based problem situation that is systemic in nature and requires the broader view associated with macro-social issues. The methodology navigates the researcher through an array of components able to deal with sensitive, multiple and complex research tasks comprising:

1. Intensive or in-depth examination of local [and national or international] situations and issues affecting communities

2. Critical explanation and comparative structural generalisation

3. Open discourse and transformative redefinition or action

4. Reflexive-dialectic orientation that underpins all other components

(after Cecez-Kecmanovic, Citation2007)

5. Mid-range theory – evaluation of an example

The evaluative study providing the mid-range theories in this design process is an extract of the first phase of a design science research thesis entitled, “Towards the Design of a Networked Social Services Media Model to Promote Democratic Community Participation in South African Schools” (Monson, Citation2013). That first phase is entitled, “Schooling and School Communities in South Africa – A Critical Evaluation”. These faithfully reproduced, illustrative examples serve to convey the outcomes arising from the application of the methodology comprising the “Design Theories”. These mid-range theories are contained in appendices and referred to in the main body of text where appropriate. These empirical examples comprise, sequentially, the selection and justification of specific social theories (these form the philosophical foundation for the methodology produced in this study as well), the adoption of a value position and extracts that illustrate outcomes from the application of the various processes detailed in the design theories arising from this study.

The evaluative study posed the following research questions; “What are the underlying causes for the persisting problems in South African school education?” and

“How may democratic participation of communities in support of their schools, lead to transformation?”

6. Kernel theories

The Kernel Theories that explain and predict the outcomes of the processes to develop Design Theories, will necessarily include key theoretical knowledge relevant to the category and type of artefact being designed.

6.1. Principles for conducting critical IS research

By way of definition, the following succinct overview of critical research appears on the Association for Information Systems’ website; “Critical researchers assume that social reality is historically constituted and that it is produced and reproduced by people. Although people can consciously act to change their social and economic circumstances, critical researchers recognise that their ability to do so is constrained by various forms of social, cultural and political domination. The main task of critical research is seen as being one of social critique, whereby the restrictive and alienating conditions of the status quo are brought to light. Critical research focuses on the oppositions, conflicts and contradictions in contemporary society, and seeks to be emancipatory i.e., it should help to eliminate the causes of alienation and domination” (https://www.qual.auckland.ac.nz/).

Critical researchers start out with a priori theoretical concepts derived from one or more critical theorists although the selection of theory depends upon which concepts are judged to be of most relevance to the social situation being studied (Myers & Klein, Citation2011). The social theories selected for a study would reflect the topic of the inquiry and influence the sourcing and interpretation of data. Assessment of the suitability of the various theories for any specific study would be based upon determining whether the theories, if applied, would embellish achievement of the 3 elements of insight, critique and transformative redefinition that characterise critical research (Alvesson & Deetz, Citation2000). The selected social theory/theories should provide a lens to focus on the research topic in order to establish a feasible means of achieving a deep understanding of the problems, given the data and research resources available. They should also provide the direction of transformative redefinition through solutions that may conceivably be facilitated through the application of IS at a later stage in the DSR process.

Guided by Myers and Klein (Citation2011), consideration was given to 3 social theorists who provide distinctly different approaches to engaging with the objectives of CRT. These were Bourdieu, Foucault and Habermas. Bourdieu’s social theories underpin ethnography that engages research participants directly and in their natural settings in order to gain insight into problem situations from the perspective of the subjects of study. This approach was deemed inadequate for engaging with the macro issues pertaining to sustainable development, especially those of a systemic nature as there would be a high likelihood of difficulty in reconciling any ethnographically defined sub-formation of society as being representative of the whole. Consequently, the social theories of Habermas and Foucault were assessed and compared to determine suitability for providing the philosophical basis for the methodology. From a philosophical perspective, Habermas’ social theory is based upon morality achieved through consensus and Foucault’s is based upon real history exposed in terms of conflict and power (Flyvbjerg, Citation1998). Foucault was considered the more appropriate social theorist for the methodology in the following respects;

Habermas’ theoretical approach to engaging with power through the distilling of consensual conclusions arising from analysis of public sphere information, is less reliable and achievable in research domains where power may restrict or dilute access to the public discourse, than Foucault’s theory of the “archaeology of knowledge”. Foucault’s theory interrogates “discursive formations” compiled from written texts, including verifiable public sphere data, academic writings, legislation, official reports and surveys, etc. that reflect the exercising of power. Habermas’ theories rely on sourcing data through accessing the public sphere of discourse (Myers & Klein, Citation2011) that encompasses political parties, politicians, lobbyists and pressure groups, mass media professionals and the vast networks of electronic and print media that focus on informing and transforming public opinion (Cukier et al., Citation2008). Specifically, academic studies, legislation and philosophical texts are excluded from the Habermas’ public sphere because they fail to meet one of the three “institutional criteria”, namely inclusivity, upon which the Habermasian public sphere for discourse is based (Habermas, Citation1989). For data organisation, Habermas postulates the (contentious) pre-existence of conditions for effective “discourse ethics” and “communicative rationality” that would deliver the truth by “the force of the better argument” (Flyvbjerg, Citation1998). By contrast, Foucault’s “archaeology of knowledge”, which examines the discursive traces left by the past in order to understand the processes that have led to what we are today (Foucault, Citation1972), provides a more robust and achievable approach for studying prevailing situations and circumstances arising from the legacy of past policies and actions of the powerful. For analysis to reveal problems, Habermas does not commend analysis of authority as the Habermasian view is of an idealistic authority reduced to a written constitution that defines the rules for democratic process (Flyvbjerg, Citation1998). Foucault on the other hand, places emphasis on analysis of authority wielded by the powerful [state] as the means of exposing the underlying causes of a social problem situation. Foucault’s method addresses questions to three broad domains: firstly, one of reason, truth, and knowledge; secondly, one of power, domination, and government; and finally, one of ethics, self, and freedom, collectively forming the “Foucauldian triangle” of truth, power and self (Dean, Citation1994a; Flynn, Citation1987).

Appendix A provides an example of the process of selecting critical theories and detailed explanations of the various Foucauldian theories and concepts applied in the design of the methodology repeated in this paper.

6.2. Selecting and justifying a value position

This section explains how the application of CRT within a DSR project provides a means of “performing the conceptual investigation phase of the tripartite methodology for Value Sensitive Design”. “Critical research appears to be the only research philosophy that moves values to the very core of research projects” (Myers & Klein, Citation2011, p. 33) and doing so, provides motivation and grounding for those projects. Doing so also acknowledges that certain values may conflict with other values, so the declaration of a specific value position establishes the ethical considerations that influence a particular design process. This CRT approach to defining a problem and conceptualising a solution builds on the “Value Sensitive Design” methodology (Friedman et al., Citation2008) wherein values are upheld as central criteria in the design of computer-based solutions. Friedman et al. (Citation2008) had in turn, built on earlier academic studies into this complex topic that is encapsulated by these words of Weizenbaum (Citation1972);

What is wrong, I think, is that we have permitted technological metaphors … and

technique itself to so thoroughly pervade our thought processes that we have finally

abdicated to technology the very duty to formulate questions … . Where a simple man

might ask: “Do we need these things?”, technology asks “what electronic wizardry will

make them safe?” Where a simple man will ask “is it good?”, technology asks “will it

work?” (pp. 611–612)

Whereas the “Value Sensitive Design” is an iterative methodology that integrates conceptual, empirical and technical investigations into design processes, this paper is purely concerned with the conceptual investigation of the design process and the influence that values would have on the definition of a problem and the design of conceptual solutions.

The adoption of a value position requires commitment and courage to be true to the ethos implied by the value position in the face of opposition by the powerful and their agents, in various roles, who may be opposed to your inquiry. Specifically, these are social values based on human concepts of morality and are exogenous to the IT artefact. The value position may be based on a philosophy, an ideology, an ethical stance or social convention that provides a focus and context for both the insight and critique (defining the problem) as well as the transformative redefinition (defining the solution) activities of critical research processes. The implication of the imposition of a pre-determined value position on the research processes is that the researcher might have given consideration to the potential impact of IS as an enabling influence to give effect to outcomes aligned to the value position but should nevertheless adopt a technology agnostic attitude. The researcher is therefore called upon to justify the selected value position and clearly explain its effect on transformational redefinition that will, at least in concept, make things better and be good for society. However, there are also potentially complementary values that might be encompassed in pursuing the social values and these are endogenous to the IT artefact. An IS researcher would likely be more aware of them as knowledge embedded through exposure to the IS discipline. These values are those associated with direct human interaction with ICTs and include values such as privacy, ownership and property, physical welfare, freedom from bias, universal useability, autonomy, informed consent and trust (Friedman et al., Citation2008). The adopted value position, along with the implicit social justice ethos in critical research, establishes the ethical stance to be maintained throughout all phases of the inquiry. This underpinning of the DSR research processes with a justified value position, sets it apart from other applications of the paradigm because it is embellished with social justice objectives that define it as a SRD activity. An example of the selection of a value position is illustrated in Appendix B.

7. Design theories – a critical research methodology in the sustainable development domain

Selected social theories of Michel Foucault (hereinafter referred to in italics), including “History of the Present”, “Regimes of Truth”, “Regimes of Practices”, “Power”, “Discourse” and “Discursive Formations” have guided the design of the methodology explained hereunder. These theories provide a substantiated approach towards dealing with issues that are underpinned by power relationships that characterise macro-social and environmental issues. The resulting methodology addresses all the objectives of this study; primarily, it is a methodology for applying critical research in the pursuit of socially responsible design science research in the IS field; it also provides a practical guide for engaging in critical research theory to complement the numerous IS studies devoted to theorising about critical research theory; additionally it provides an approach to performing the conceptual investigation phase of the tripartite methodology for Value Sensitive Design (Friedman et al., Citation2008); and finally the methodology gives practical effect to multinational state (EU & UK) policies concerning research and innovation in a socially responsible manner.

The designed method recommends a three-part process of discourse analysis that provides for a systematic, thematic, interrogation of non-public sphere data contained in ideological texts, policy documents, legislation and academic, peer-reviewed papers but also of validated public sphere data sourced from surveys and reputable media services. Inductive, deductive and dialectic reasoning are applied to varying degrees in critically analysing the data within an array of sub-themes that are specific to each topic of research.

In order to clarify the methodology both contextually and conceptually, it is necessary and prudent to define certain principles. “Principle (Durkheim) (as against complete inductions which can’t be had) can abridge the inductive process, and allow carefully chosen classifications. The origin of principles is independent of their function in ideal theoretical system. In all cases there is conceptually formulated knowledge and the facts to be subsumed under it = theoretical explanation [context of discover vs. justification]” (Horkheimer, Citation1972, p. 1). The particular principles for this methodology are encompassed in specific definitions for the terms; economic activity, powerful and society as these depict the focus of inquiry and the major role players in situations pertaining to the sustainable development context.

The topic of research will be an economic activity that is responsible for giving rise to a problem situation in a macro social or environmental context. Economic activities encompass any activities using economic measures to assess their success and include, amongst many others, industrial, agricultural, extraction of natural resources, military capacitation, infrastructural provisioning and social services activities. The terms powerful and society are ascribed meanings in the context of the sustainable development scenario. The powerful are those who are in a position through might, wealth, social authority or association, to undertake an economic activity that imposes consequences on society. The powerful, thus defined, may include amongst others, states, rulers, corporations, associations and management while society are all formations of the non-powerful, from the individual to communities in their various roles, who are subject to the actions of the powerful and require protection from abuse under the ethos of social justice.

In compliance with the three major objectives of critical research, the strategy engages three analytical activities; Insight informed by History, Critique of Power Relationships and Transformative Redefinition through Practices. The social theories and concepts of Foucault are adopted for reasons relating to; the dimensions and diversity of communities effected by social exclusions and unsustainable development practices; the power relationships between the powerful and societies that are implicit in economic activities; the conceptual approach provided for determining truth in the multi-layered and complex systems of administration that are typical of economic activities; and the intuitively sound means of determining effective practices for transformation.

Foucault’s social philosophies of discourse; archaeology and genealogy of knowledge, and panopticon (Myers & Klein, Citation2011) entail that detailed historical studies of the topics and subjects of research are conducted to reveal the interdependence of knowledge and power in discursive social practices. However, Foucault does not recommend a particular methodological approach or framework but his social theories pertaining to history of the present, discursive formations, regimes of truth and regimes of practice (Dean, Citation1994a; Flyvbjerg, Citation1998; Myers & Klein, Citation2011) serve to guide the approach of the framework developed in this paper when informed by the contexts provided by Foucault’s concepts of power, truth, the state and society.

Insight – In the critical research theory perspective, social reality is historically constituted and perpetuated by people (https://www.qual.auckland.ac.nz/). Insight is sought through the methodology prescribed in the following passages in accordance with Foucault’s “Archaeology of Knowledge”, whereby examining the discursive traces left by the past in order to understand the processes that have led to what we are today (Foucault, Citation1972). In Foucault’s theory, the general context of archaeology is that of a history of the present. The “history of the present” may be loosely characterised by its use of historical resources to reflect upon the contingency, singularity, interconnections, and potentialities of the diverse trajectories of those elements which compose present social arrangements and experience (Dean, Citation1994a). Therefore, in order to achieve insight into a topic of research, the historical route of events pertaining to the topic must become a focus of research. Interrogating the history of a research topic provides insight to present problems by revealing the evolution of situations arising from disjuncture between the actions of the powerful (state, rulers, corporations, management, etc.) and needs and expectations of society (citizens, communities, workers, consumers, etc.), over time. Through this process, the researcher derives the clear and deep understanding of insight into the nature of problems and knowledge to inform, through inference, the route to solutions.

Critique – Expose the power relationships of the powerful and between the powerful and society to critique their motives (philosophical, ideological and self-serving) and the consequential mechanisms of power (policies, decrees, plans, contracts or any other formalised agreements designed to execute the desires of power) spawned by them, to reveal and understand the nature of the underlying causes for present problems. The concept of power in the form of the relationship between the powerful (state) and society is central to a Foucauldian research strategy. Power structures and relationships define who, within the structure of powerful, wields what power, how the power is exercised in relation to contending social and political values and in which ways it is exercised to influence the social and political discourse that provide the focus for Foucault’s concept of regimes of truth. “Truth” is “a system of ordered procedures for the production, regulation, distribution, circulation and functioning of statements”; it is linked “by a circular relation to systems of power which produce it and sustain it, and to effects of power which it induces and which redirect it” (Foucault, Citation1980, p. 133). Power, as it is exercised by the state [the powerful], “consists in the codification of a whole number of power relations which render its functioning possible – Foucault (Citation1980)” (Dean, Citation1994b, p. 157). Foucault describes these relations of power and authority, working through disciplinary techniques, as infrastructural powers of the state [the powerful] that dominate through the control of the micro-structures of individuals. Thus the state [the powerful] brings together, arranges, and fixes within that arrangement the micro-relations of power (Dean, Citation1994b).

Transformative Redefinition – Infer the route to transformation and the practical steps necessary to achieve emancipation through the attainment of transformational objectives. This route is informed by the precepts of social justice and the value position adopted for the research which will later be assessed in terms of its enablement through IS. As a generalisation of the many philosophical and political variations applied to its meaning, the term “social justice” implies a striving for the individual to receive fair and just treatment from society and the powerful. While not venturing to argue the numerous variations and perspectives applied to the term, it is used with a bias based on the perception that it is analogous to principles of democracy while also conflicting with them, dependent upon prevailing political orientation and understanding of the concepts at a given time (Miller, Citation1978). Therefore, in the midst of a varied spectrum of understandings, nuances and opinions, this paper refers to social justice as the extent to which the powerful, including governments and their agents, apply the collective resources of society, including the resources of the state, for the general betterment and welfare of society, in an accountable way.

The analysis of data therefore must not only seek to reveal the truth about economic activity but also seek the route to transformation. In this regard, Foucault refers to regimes of practice as organised systems of practices rationalised according to particular forms of knowledge.

“ … the history of a morality has to take into account the different realities that are covered by the term. A history of ‘moral behaviours’ would study the extent to which actions of certain individuals or groups are consistent with rules and values that are prescribed for them by various agencies … a history of ‘codes’ would analyse the different systems of rules and values that are operative in a given society or group … a history of the way in which individuals are urged to constitute themselves as subjects of moral conduct would be concerned with the models proposed for setting up and developing relationships with the self, for self-reflection, self-knowledge, self-examination, for the decipherment of the self by oneself, for the transformations that one seeks to accomplish with oneself as object”. (Foucault, Citation1985, p. 29)

An analytic of practices can thus be worked out along four dimensions or forms of knowledge according to Foucault (Citation1985) (Dean, Citation1994c):

An ontological dimension, of what we seek to govern in ourselves or others by means of this practice.

A deontological dimension, of what we seek to produce in ourselves and others when governing this element.

An ascetic dimension, of how we govern this element, with what techniques and means. This would be a worldly asceticism as postulated by Max Weber (1905) (Wallace, Citation1999), as a practice of discipline and restraint in the pursuit of salvation or liberation where “the highest form of moral obligations of the individual is to fulfil his duty in worldly affairs” (Wallace, Citation1999, p. 278).

A teleological dimension, of the aim of these practices, of the kind of world we hope to achieve by them, of the kind of beings we aspire to be (Dean, Citation1994c).

The strategy entails an analysis of specifically sourced, literary data concerning the history, power structures & relationships and transformational issues related to the topic of research. These sourced data are arranged into discursive formations aligned to the themes of “History of the Present”, “Regimes of Truth” and “Regimes of Practice”. Interpretive analysis applies phenomenological and hermeneutical processes to produce insight into the phenomenon of the research topic, critique of the motives and methods of power and inference to deduce the routes to transformational objectives. These collectively build an ontological perspective of the problem that informs the design of a solution.

illustrates the sequence and activities described in the following framework.

The following prescriptive processes represent the critical research methodology. While the tutorial style of the text may appear dense and challenging, it is designed to guide inquiry into subject matter that may be both complex and deceptive. The prescriptive statements are guided by the Foucauldian theories mentioned above and refined through reflection on the experiences gained from their application.

7.1. Part one – Interrogating history

The following data sourcing and data organisation processes are also integral parts of the analytic processes that follow them inasmuch as knowledge derived from their execution provides further data into the analytic cycle.

7.1.1. Sourcing data

The systemic nature of economic activities related to macro-social and environmental problems imbues them with an aura of being “too big to handle” and the complex practices and structures applied by them create layers of imperceptibility. This deliberate opaqueness implies that data sourced to study topics concerning these economic activities be gathered from sources that are reflective of as wide a spectrum as is feasible. Doing so provides the means to gain insight through a nomothetic (in the sociological sense) accumulation of data to achieve an holistic picture (akin to a textual collage) of the problem that is inclusive of the multiplicity of related power relationships, misinformation, social consequences and environmental impacts. The systemic nature of macro-social and environmental issues preclude the adoption of the more idiographic approaches suitable in organisational settings where the assurance of reliable discourse is relatively high.

In accordance with Foucault’s discursive formations, the form of data is limited to written texts that are subject to transparent rules and ethics in their formation that reflect a verifiable striving for accuracy and truth. As the inquiry focuses on the exercising of power and the relationships of the powerful, the data should include historical and current policies and agreements governing the execution and performance of the economic activity. Acceptable sources are academic papers, government policy documents, statutory reports and returns, survey reports, the public printed & digital media (where care has been taken to distinguish the “tabloid” from the “ethical”) and published reference works concerning the economic activity. In order to achieve insight into the motivation behind the exercising of power, the data should also include published policies and communications originating from the economic activity, reference works on relevant ideological, philosophical and social theories adopted by the powerful who benefit from the economic activity, as well as texts of original ideological and philosophical treatises espoused by the powerful. As the ethical foundation of the research is reflected in the adopted value position, ideological and philosophical texts concerning the value position must, of necessity, be included. (Appendix C provides an example of a Data Sourcing Process from the mid-range theories)

The scoping of the inquiry requires careful consideration. When dealing with issues effecting widely distributed communities that may be ethnically, culturally and socio-economically diverse, caution should be exercised as follows: The validity of data obtained from sources reflecting collations and analysis of empirical data that are too narrowly or parochially based within the broader community, are to be avoided in order to prevent results that are unduly skewed to cause deviations in perception and understanding of the broader problem situation. However, if the research topic and scope dictates a specific sub-section or strata of society, the data reflecting the specific should be extracted from the wider scope of data in order to position the specific within the context of the whole. An estimation based on an informed perception of the size and locale of the section of society effected by the economic activity is required in this regard.

Applying a rationale based on the focus of the inquiry, the nature of the problem being addressed would determine the scope of the inquiry. If the problem arises from continuing maladministration or corruption of process and governance, a guiding principle for making this determination is, “the proportion of society defined by the extent and reach of the administrative power that governs the economic activity”. In other words, the size of the effected community may be determined by the structures of the powerful that wield the laws and policies that govern the economic activity. Therefore, the more decentralised the structures, the more narrowly focused may the community be. However, if the problem arises from consequential environmental impacts, a guiding principle for making this determination would be “the proportion of society located within the geographical range of the adverse environmental consequences arising from the economic activity”. Variations and combinations of the nature of the problems being addressed would inform deviations from these guidelines.

7.1.2. Data organisation

Michel Foucault articulates three interrelated themes of history, power structures and transformation for social emancipation (Myers & Klein, Citation2011) for critical inquiry. Within each pre-defined theme, the data should also be sorted into relevant sub-themes identified by the researcher and be continuously refined as the researcher’s knowledge of the research topic increases. When further sub-themes are not forthcoming, the process is complete. The rigour of this process ensures that all necessary and relevant aspects of the research topic are adequately covered. An analysis of the data by sub-theme and source must be undertaken to provide an overview of the data and its contents within each of the major themes in order to illustrate the depth and sufficiency of the sourcing process. (Appendix D provides an example of Data Organisation for Analysis from the mid-range theories)

7.1.3. Analytical approach

The strategy requires a thematic review of data reflecting the historical and social contexts of the society effected by an economic activity related to either a macro-social or environmental issue. Upon identifying an issue, a researcher would engage in finding responses to the questions; When, Why and How. Each factor arising from these questions would in turn be subjected to the same 3 questions. When responses to cycles of questions start to replicate themselves to the point that no new responses are uncovered, the inquiry process has achieved saturation. Throughout this process, the researcher’s knowledge and understanding grows and this in turn enhances the researcher’s capacity for interpretation. The aim is to build an understanding inductively, deductively and dialectically, of the historically foundational circumstances of the society in the context of the research topic. (For example, if the research topic related to industrial pollution, data would be gathered on the roles and activities of all stakeholders in the economic activity that results in pollution, in order to identify and track, over time, both the causes and the consequential effects.)