ABSTRACT

Research on crowdwork in developing countries considers it precarious. This reproduces its Western conceptualisation assuming that crowdworkers in developing countries imitate their Western counterparts, without close examination of their experiences and responses to work conditions. This study breaks this epistemological terra nullius to pursue an in-depth examination of workers’ lived experience in a developing country and provide a non-Western perspective. It questions how crowdworkers experience and respond to crowdwork and adopts an inductive approach in examining crowdworkers in Nigeria. Unlike the work precarity thesis, we find that crowdworkers in Nigeria transition and transform crowdwork into long-term employment, drawing on their own cultural heritage, social norms and traditions. Through the lens of the indigenous theory of liminality, we conceptualise crowdwork as liminal digital work and uncover three phases in this transformation process. The study concludes that the agency of workers, their culture and their own context play important roles in their experience of crowdwork. This demonstrates that the in-depth examination of the phenomenon in developing countries could destabilise the dominant knowledge, decoupling it from its origin of production and exposing and examining its implicit and explicit assumptions, and hence advance theorisation.

SPECIAL ISSUE EDITORS:

1. Introduction

Crowdwork is a model of digitally organised employment in which work is commissioned, carried out and delivered entirely online, mediated by what are termed digital platforms of work or labour digital platforms (Howcroft & Bergvall-Kåreborn, Citation2018; De Stefano, Citation2015). It is an important transformation in the world of work and is a globally proliferating phenomenon. A recent survey by the International Labour Organization (ILO) shows the global spread of crowdworkers, with “important representation” from workers in developing countries,Footnote1 including Brazil, India, Indonesia and Nigeria, in addition to Western countries (Berg et al., Citation2018, p. 31). Research on crowdwork in developing countries imitates and reproduces its Western perspective, which depicts it as precarious work. This is despite the lack of in-depth understanding of crowdwork in developing countries from workers’ perspectives (Berg, Citation2016). Precarious work is defined as “uncertain, unpredictable, and risky from the point of view of the worker” (Kalleberg, Citation2009, p. 2-emphasis added). Therefore, workers’ perspectives and experiences of crowdwork are key to the understanding of this new form of digital work. Importantly, imitating and reproducing the Western perspective and applying it uncritically to development countries carries the risk of: 1) encouraging “monological knowledge production” and accepting the myth of “epistemological terra nullius” (Martin & Mirraboopa, Citation2003; Motta, Citation2021); and 2) accepting the superiority assumption that crowdworkers in developing countries imitate and follow in the footsteps of their Western counterparts. To overcome these theoretical inadequacies, this study aims to answer the questions of: how crowdworkers in developing countries experience and respond to crowdwork? To answer the research questions, the study examines crowdwork in Nigeria and employs inductive in-depth research methods to foreground the phenomenon as experienced beyond the dominant Western conceptualisation. Theoretically and empirically, it focuses on macrotasking as one type of crowdwork that has been consistently under-studied and mistakenly amalgamated with the much studied microtasking, often under the wider label of “gig economy” or “platform economy”. Nigeria provides a rich context to study the experience of crowdworkers, given its high youth unemployment, growing educated and young population, and increasing adoption of information and communication technologies (ICTs) and digital technology (Gillwald et al., Citation2017). Moreover, its economic indicators, including unemployment and the informal economy, are representative of most developing countries; its sociocultural and economic climate is representative of the African collective culture; and its government has deliberately promoted crowdwork as a way of reducing the alarmingly rising unemployment rate in the country (Ramachandran et al., Citation2019). We had privileged access to crowdworkers in Nigeria that permitted us to collect rare rich data from multiple sources, including 44 interviews, observation of 17 crowdworkers over 9 days and different website reviews, in addition to observation of social media groups and closed crowdworker WhatsApp groups.

During data analysis, themes emerged that resonated with the indigenous theory of liminality (developed from studying tribes in the African countries of Zambia, Mozambique and Uganda), and hence this theory was adopted as a sensitising device to coherently explain the phenomenon.Footnote2 The findings show that crowdwork is liminal digital work that is initially “betwixt and in-between” employment models. Yet, crowdworkers in Nigeria transition and transform it into long-term employment that is culturally recognised and accepted, drawing on their culture heritage, social norms and traditions. The study identifies the phases of this transition and transformation and shows that the agency of workers, culture and their own context play important roles in their experience of crowdwork.

This study contributes to research in many ways. First, we provide an indigenous theorisation of crowdwork in the context of developing countries. Contrary to Western conceptualisations, we understand crowdwork in Nigeria through a culturally sensitive lens and indigenous theory that allows us to focus on the specificity of the context and come closer to the lived experience of workers. In doing so, the study destabilises the dominant knowledge, decoupling it from its origin of production to expose and examine its implicit and explicit assumptions and hence advance theorisation. Second, in understanding crowdwork as liminal work and accounting for the transition and transformation involved, and highlighting the role of workers’ agency, culture and social norms, we advance the theorisation of crowdwork. We also reveal and examine some of the implicit and explicit assumptions behind the current conceptualisation of precarity, including being inherently static, individualistic and digitally entrenched work. Third, in focusing on macrotasking as one type of crowdwork, the study sheds important light on the differences between types of crowdwork in developing countries and on the importance for research not to use crowdwork types as synonymous or to gloss over their differences, amalgamating them under the wider umbrella of “gig economy” or “platform economy”, echoing Western scholarship. Fourth, the study responds to scholarly calls for IS researchers to seriously consider non-Western contexts with fresh views beyond the dominant Western perspectives and to brave highlighting local perspectives (Davison & Martinsons, Citation2016). It shows the value of this approach not only in producing relevant knowledge that respects and acknowledges multiplicity but also in significantly contributing to the advancing of theories and knowledge. Finally, the findings could guide policy makers in facilitating positive experiences for crowdworkers, taking into account its ripple effect in society.

The paper consists of seven sections. Following the introduction, section two provides an overview of crowdwork literature while section three presents the theoretical grounding of the study. Section four details the research methodology, section five presents the empirical findings and section six discusses the findings and their theoretical contribution. Section seven concludes the research, highlighting its limitations, practical implications and further research avenues.

2. Crowdwork model and digital platform of work

2.1. Macrotask crowdwork

Crowdwork comprises two types, microtasks and macrotasks. Microtasks are small, marginal and largely repetitive tasks that can be conducted in a short period of time; macrotasks are typically associated with significant and creative knowledge work that usually requires longer durations and higher levels of skill and expertise to complete than the tedious microtasks. Despite these differences, research on crowdwork tends to treat both types as synonymous and even combines them with other types of on-demand work under the single vague umbrella of “gig economy” or “platform economy”. While the two types of crowdwork differ from each other, they also differ from on-demand platform labour. In crowdwork, the work is conducted entirely on digital platforms and, hence, work is disassociated from the geographical location of workers and employers; on-demand labour platforms such as Uber, Lyft, Deliveroo and others are based on the physical delivery of services and, hence, are dependent on the geographical location of workers and employers.

In macrotask crowdwork, digital platforms such as Freelancer.com, Upwork and Fiverr offer a wide range of tasks related to information technology (IT) and business services from employers in different geographical locations worldwide (Kittur et al., Citation2013). Tasks commonly offered on macrotask digital platforms include image creation, graphic design, web design, app development, software testing, branding, product design, data entry, content creation and market research (Bhandari et al., Citation2018). A recent analysis of four major crowdwork platforms finds that technology and software development account for 53 percent of all the crowdwork jobs posted and completed (Kässi & Lehdonvirta, Citation2018). To summarise and clarify, in its macrotask form, crowdwork provides task-based employment for skilled knowledge workers in which they obtain and deliver their work online through digital platforms.

The current understanding of crowdworkers is not only based primarily on microtask crowdwork, overlooking the specificity of macrotasks, but is also focused mostly on one particular microtask platform, namely Mechanical Turk (Berg et al., Citation2018; Deng & Joshi, Citation2016; Deng et al., Citation2016; Durward et al., Citation2020; Ma et al., Citation2018). The few studies that have considered macrotasks include it under the broader umbrella of “gig work” or “digital platform labour”, combining research results without recognising the differences between crowdwork and on-demand work or between the types of crowdwork (See for example: Anwar & Graham, Citation2021; Graham et al., Citation2017; Mann & Graham, Citation2016; Tan et al., Citation2021; Wood et al., Citation2019).

2.2. Crowdwork in developing countries

The digital properties and characteristics of crowdwork have prompted labour activists to warn about its precarity in developing countries. Yet, research on crowdwork in developing countries tends to mix the different types, amalgamate them with on-demand work in a single category (gig economy), and adopt a political economy perspective on capitalism (for a comprehensive review, see:Heeks, Citation2017). This mixing of different types of online work has led researchers to pronounce digital platforms “digital sweatshops” (Felstiner, Citation2011; Lehdonvirta, Citation2016; Schor & Attwood‐Charles, Citation2017). While studies of crowdwork in the context of developing countries are generally limited, the existing research further limits its exploration to a classic Marxist view on the struggle of working class and capitalism exploitation (Anwar & Graham, Citation2021; Graham et al., Citation2017). These studies raised concern regarding the precarity of crowdwork, suggesting that platforms’ bidding systems push crowdworkers to race to the bottom in terms of payment and emphasising the capital control of digital platforms over workers through digital means (Beerepoot & Lambregts, Citation2015; Graham et al., Citation2017; Scholz, Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2019). However valuable, the use of the Western notion of precarity to conduct surveys on workers in developing countries (Kalleberg & Vallas, Citation2018) lacks an in-depth understanding of context and of workers’ responses to this form of work. In studying African gig work, studies paradoxically suggest that such work brings freedom, flexibility, precarity and vulnerability to the lives of African gig workers, without offering a particular conceptualisation of why these mixed qualities of work are being experienced (Anwar, Citation2017; Anwar & Graham, Citation2021, Citation2020). Workers have hinted that skills allow them to “break the barriers to entry on Upwork” and earn higher income than the local rates for the same jobsFootnote3 (Anwar & Graham, Citation2021, p. 246); researchers observe that workers maintain social media interactions and digital communications with friends and fellow workers (Gray & Suri, Citation2019), and that workers are “able to exert their individual structural power over clients” (ibid., p. 252). Nevertheless, such research has continued to be pre-committed to the dominant knowledge regarding political economy and the precarity perspective. Research on crowdwork in developing countries in general, and in Africa in particular, appears to uncritically adopt Western conceptualisation without attempting to produce alternative knowledge, or even consider the possibility of doing so (Elbanna & Idowu, Citation2021).

Reviewing the positive and negative knowledge base on the gig economy in developing countries, Heeks (Citation2017) highlights the importance of taking crowdworkers’ perspectives seriously in determining any interventions based on the precarity arguments. Indeed, work traditions, culture, societal norms and social relations in developing countries are different from those assumed in the West (Barnard et al., Citation2017; Nyamnjoh, Citation2012). Moreover, precarity assumes a society dominated and ruled by the formal economy, which contrasts with the domination of the informal economy in developing countries (Charmes, Citation2012; Standing, Citation2014). What workers do on digital labour platforms and how they respond to this form of work within their own context is more important and relevant for developing countries than a Western understanding of how work should be. This is particularly the case as crowdwork is a new form of work; thus, comparing it to the traditional conventions misses the opportunities it might hold and the alternatives it might represent (Cheney, Citation2014; Kalleberg & Vallas, Citation2018; Miller, Citation2010). Hence, worker-centric and context-sensitive research is needed that can map crowdworkers’ experiences and how they deal with the conditions of work in developing countries. This study aims to close this gap and contributes to the debate on the value of crowdwork.

3. Theoretical grounding: theory of liminality

Liminality is an anthropological theory that describes the “betwixt and between” position of a rite of passage. While originally identified as a concept by Van Gennep, Citation1909/1960), it is through Turner’s extensions and development that the theory has gained popularity (Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018). Victor Turner developed it based on his examination of the rituals and rites of passage of the Ndembu tribe in Zambia, the Swazi of Mozambique and tribes in Uganda, later extended to many other contexts and life situations (Turner et al., Citation2017). According to Turner (Citation1969), the theory of liminality expresses “indigenous concepts” to understand human beings’ transition and change (Turner, Citation1969, p. 4). Turner explains that rites of passage indicate and constitute transitions between states as determined by “culturally recognized degree of maturation”, such as legal status, profession, office or calling, rank or degree (Turner, Citation1987, p. 4). An example of one of the many rituals and rites of passage of the Ndembu that Turner studied is the ritual surrounding the transformation of males from childhood to adulthood. In this ritual, a child is transformed into an adult through the liminal experience of going alone or with a group of peers to the bush, cut off from the normal social interactions within the village and household (Turner, Citation1974). Typically, in a liminal journey, the individual (s) acquires knowledge and skills and commits to society and their future role. Liminality is a transitional and transformative journey during which the individual is temporarily a structurally indefinable “transition-being”; “they are at once no longer classified and not yet classified” (Turner, Citation1987, p. 6). They are neither one thing nor another, neither here nor there and “at the very least ‘betwixt and between’ all the recognized fixed points … of structural classifications” (ibid., p. 7). In this sense, liminality is “not dealing with structural contradictions … but with the essentially unstructured (which is at once destructured and prestructured)” (ibid., p. 8).

Turner adds that “liminal personae nearly always and everywhere are regarded as polluting to those who have never been, so to speak, ‘inoculated’ against them, through having been themselves initiated into the same state” (ibid., p. 7). The Ndembu of Zambia define the liminals (subjects who go through a liminal experience) by clearly giving them the title “mwadi”. Liminality consists of three highly interlinked and overlapping phases: initiation and separation, transition and reincorporation.

The first phase, initiation and separation, is where the very name of the subject is taken away and they are called by a generic term for “initiand” or “neophyte”. They are structurally “invisible” and are treated as structurally neither living nor dead. The indigenous term for this liminal phase among the Ndembu is “Kundunka, kung’ula”, meaning “seclusion site”. The neophytes are considered to be “in another place” where they have physical but not social “reality”, so they have to be hidden, removed to a sacred place of concealment or ceremonially disguised. Turner explains that “their condition is indeed the very prototype of sacred poverty”, in which they are stripped from their social and cultural demarcation (Turner, Citation1987, p. 11). In this regard, transitional beings are “unaccommodated” and have nothing: no status, property, insignia, rank, secular clothing or anything to structurally demarcate them.

In the second phase, transition, the liminals are forced to think about their society and “the powers that generate and sustain them” while they continue to be structurally “invisible”, carrying ambiguous and paradoxical status (Turner, Citation1987, p. 14). In this stage, they reflect, learn, take actions and show symbolic articles to demonstrate their progress towards maturation. This phase represents growth, transformation and the reformulation of old elements in new patterns as liminals acquire knowledge that prepares them for “culturally recognised maturation”, and hence their roles and duties ahead. In this phase, there is “intermingling and juxtaposing of categories, experience and knowledge with a pedagogic intention” (ibid., p. 15). Their newly acquired knowledge combined with actions and symbolic exhibition transformsFootnote4 their being and redefines their social status. When the rites are collective, the neophytes in this stage develop comradeship with others in the same liminal journey, sharing food, knowledge and activities. The comradeship formed, known as “wubwambu” or “wulunda”, which means “feeding together”, is also characterised by outspokenness, exchange of support, frankness and social interconnections. Liminality at this stage is connected to the development of “communitas”, in which individuals facing a similar liminal experience converge into a supportive homogenised-by-the-experience group (Turner, Citation1987).

The third phase, reincorporation, occurs when “the neophytes return to society with enhanced knowledge of how things work, but they have to become once more subject to custom … [and] social norms” (Turner, Citation1987, pp. 15–16). As they reintegrate into society, those who were previously liminals are rid of the stress of the previous two phases and celebrate their new role or status. They also re-enter the structural realm of society equipped with new knowledge and understanding, ready for their new role or status. Thus, they are incorporated back into society with “a new and relatively stable state in which obligations and norms differ from those of the initial state” (Thomassen, Citation2015, p. 881).

provides a summary of the terminology of the theory of liminality. While the theory was originally developed to understand culture, rituals and rites of passage in Africa, Turner later expanded it in a series of publications to show that liminality is not necessarily an obligation “enforced by sociocultural necessity”, but could be optional, in what he terms “liminoid experience” (Turner, Citation1974p. 85). He argues that liminality could be experienced by individuals, groups or populations. It can be temporary and transitional, or a state in itself where its suspended character takes a more permanent state: “Liminality becomes a permanent condition when any of the phases in this sequence … becomes frozen, as if a film stopped at a particular frame” (Szakolczai, Citation2000, p. 220).

Table 1. Summary of key concepts/ideas in the indigenous theory of liminality

The theory of liminality has been applied in “all branches of social and human sciences” (Thomassen, Citation2015, p. 39) and is widely used in organisation and management studies, where it “is commonly taken to mean a position of ambiguity and uncertainty: being betwixt and between” (Beech, Citation2011, p. 287). It is celebrated as a postmodern theory that foregrounds agency and holds connotations of freedom, creativity and breaking away from restricting structural ties. Scholars argue that it “serves to conceptualize moments when the relationship between structure and agency is not easily resolved or even understood” (Thomassen, Citation2012, p. 42) and when there is no certainty concerning the outcome, but a world of contingency that can be carried in different directions (Thomassen, Citation2012, p. 41). They maintain that it offers a lens through which to analyse “indeterminacy, precarity and insecurity across different employment sectors in contemporary workplaces” (Reed & Thomas, Citation2019, p. 1) and “temporary elements of organizing and work” (Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018). In the world of work, liminality portrays open-ended or extended time periods of self-guided process, self-made communitas and incomplete or culturally problematic narrative where new scripts emerge (Ibarra & Obodaru, Citation2016).

4. Research methodology

4.1. Research methods and data collection

The study adopts a qualitative inductive approach to inquiry. This approach allows research findings to emerge from data without the constraints of existing conceptualisations about the phenomenon. It fits the research objective of overcoming monological knowledge production that uncritically echoes the Western perspective, in which “key themes are often obscured, reframed or left invisible because of the preconceptions in the data collection and data analysis procedures imposed” (Thomas, Citation2006, p. 238). This approach is recommended to “IS researchers interested in issues of process and context” (Urquhart & Fernández, Citation2016). For an in-depth examination of workers’ experiences and responses to crowdwork, we employed intimate data collection methods comprising interviews, observations, website reviews, and observation of social media groups and closed Nigerian crowdworkers’ WhatsApp groups in order to gain rich insight; in addition, we used follow-up emails to participants to clarify ideas, verify comments and request documents and evidence.

Consistent with the inductive approach, and to achieve deep, open exploration that significantly reduced the burden of existing Western assumptions, interviews ranged from unstructured to semi-structured and conducted in four phases. The first phase was conducted between December 2017 and January 2018 and consisted of unstructured interviews with six participants. In this phase, we used personal contacts to identify the first three participants, in light of the difficulty of accessing crowdworkers in Nigeria. This was followed by the adoption of the snowballing technique to identify the next three participants. Snowballing is particularly useful for finding “hidden populations” with the required characteristics which are difficult for researchers to access (Heckathorn, Citation1997; Naderifar et al., Citation2017).

Following the first phase, and to avoid the possible bias in the snowballing technique, we recruited participants in the next three phases through different channels, including WhatsApp groups, digital labour platforms and social media. The three subsequent phases took place in June–August 2018, October – November 2018 and June 2019, and consisted of 18, 12 and 8 in-depth semi-structured interviews, respectively. The respondents participating in these three phases were selected through purposeful sampling commonly used in qualitative research in cases where identification and selection of information-rich cases is required regarding a particular phenomenon of interest (Suri, Citation2011). The research inclusion criteria were as follows. Firstly, participants should have been involved in crowdwork for a minimum of two years prior to the research period. This ensured that they had sufficient experience to reliably provide insight on crowdwork and to allow the researchers to examine their response to their work conditions. Secondly, participants are specialised in IT and IT services (software programming, website design, graphics design and mobile application development). This focus on one category of professionals allowed the researchers to exclude variations relating to the nature of work and, hence, gain rich comparative insight into workers’ experience. The choice of this category in particular stemmed from different survey results showing that IT tasks and services constitute the majority of offered and conducted tasks on digital platforms (Kässi & Lehdonvirta, Citation2018).

A total of 44 interviews were conducted with 41 participants, with 3 participants interviewed twice in the first and second phases of data collection. Of the 41 participants, 12 were female and 29 were male. Interviews were mainly conversational, with our direct and indirect questions focused on understanding crowdworkers’ social and work practices, behaviour, perception of self, activities engaged in, how and why they engage in these practices, the challenges they face, how they organise their work, self and career, and their feeling and aspirations. Interviews lasted between 50 and 120 minutes (average 75 minutes), and the duration of follow-up interviews was 10–26 minutes.

In addition to the interviews, 17 participants were observed during 2 field visits to crowdworkers’ workspaces in Nigeria and notes were taken to record behaviour, conversations, interactions and experience in situ (Van Maanen, Citation1995). Participant observation is consistent with inductive research and is particularly useful in gaining in-depth insight on process, meaning, and understanding how people make sense of their lives rather than focusing only on outcomes (Mackellar, Citation2013).

In addition, we observed crowdworkers’ profiles on crowdwork platforms to follow their task completion, work patterns, earning and gained feedback. Group discussions on social media platforms, blogs and online discussions threads were also observed to gain in-depth understanding of issues and social relations. We gathered documents from respondents, comprising various worksheets and project files in addition to screenshots of mobile phone text message discussions. Participants also included us in closed WhatsApp groups and based on explicit consent, we also collected screenshots of discussions on these observed WhatsApp groups, took pictures of participants at work and their workspace, and obtained copies of work tools and artefacts such as business cards and stationery. summarises the key data sources over the phases of data collection.

Table 2. Summary of data collection phases

4.2. Data analysis

Data collection and analysis took place simultaneously to allow for exploratory themes to emerge and be formulated from data (Urquhart, Citation2012). The analysis followed an inductive thematic approach relying on the opinions of the respondents while triangulating content from different sources to enrich the research interpretive validity (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Nowell et al., Citation2017). This provided a bottom-up approach for examining the phenomenon in its context from the expressed views of participants supported by the researchers’ observations and other data sources.

The data analysis proceeded as follows. First, all interviews were transcribed verbatim and pseudonyms were assigned to interviewees to maintain their anonymity. Open coding was carried out without being influenced by extant theories or previous research findings (Braun et al., Citation2014), and members of the teams discussed the emerging codes and possible themes (Braun et al., Citation2014; Saldaña, Citation2015). Second, codes were related and interconnected with each other and the broader theme of “resistance to precarity” emerged (Hodkinson, Citation2008; Thomas, Citation2006). Third, data analysis proceeded with in-depth scrutiny of the processes workers follow and of how workers relate to their work, each other and their social environment. Literature on precarity was consulted and different theories were read. Concepts from the indigenous theory of liminality resonated with our data analysis. Hence, the theory was adopted in the following step as a sensitising device. The use of an existing theory is consistent with the inductive approach (Urquhart & Fernández, Citation2016; Urquhart et al., Citation2010) and is in line with similar inductive research (Berente & Yoo, Citation2012; Levina & Ross, Citation2003). This use can be considered in the conventional binary classification of research as “abduction”. However, the conventional classification assumes the purity of an inductive-deductive binary and, hence, the existence of a middle point between them, namely abduction. However, consistent with our postmodern orientation, we see inductive-deductive as a continuum and a loop in which different shades, degrees and combinations of inductive/deductive thinking feed into each other without having a discrete middle point.

Fourth, we found the theory of liminality a useful sensitising device to connect the themes that emerged and to provide an overarching explanation for the observed actions and behaviours. It emerged as a convincing explanation of the agency, culture, and transition and transformation of crowdworkers and their contribution to their social environment and communities and as an indigenous theory developed from examining the context of Africa, which is also the context of the study at hand.

5. Research findings: the liminal journey of crowdworkers

This section highlights the liminal experience of crowdworkers and how workers create a culturally accepted version that suits their own circumstances. The following sections present the highly interlinked and overlapping liminal phases through which crowdworkers transition and transform following their adoption of crowdwork.

5.1. Initiation and separation: neither here nor there and finding a seclusion site

Workers start crowdwork voluntarily for different reasons. For some, it was a good employment option that provides higher earning than their day job. For others, it was a way out of unemployment or a way to get flexible work that allow them to care for dependents.

As they start crowdworking, workers find it difficult to find a social reality for themselves, a culturally recognised social label that their social circles can use to define them. They recognise that they are neither workers in the traditional sense of formal work nor entrepreneurs in the sense of owning their own business. Furthermore, in the context of Nigeria, where the level of internet crime is one of the highest in the world (Kshetri, Citation2019), their online work is typically confused with internet fraudsters, or “Yahoo boys” as they are locally known in Nigeria. This liminal in-between state is precarious; it is insecure and socially unaccommodated. However, their social circles support them in disguising their undecided, “in between” employment and hide it using socially accepted labels in what resembles the seclusion site or Kundunka in Ndembu culture. Crowdworkers Seun and Taiwo describe this social cover-up of precarity and the start of their liminal experience and seclusion

“My parents tell their friends that I develop software for international clients. They don’t mention online or internet at all. I just go with it because of the poor reputation of Nigerians on the internet when it comes to making money … They understand what I do but are not proud enough to tell people I get my jobs online.” – Seun

5.2. Initiation and separation: socially hidden and performing digital platform rituals

Workers quickly find that gaining better ranking and rating is one of the routes to progress and transition to obtaining jobs on a more regular basis and achieving stable income. As with other African rituals, they go through it knowing that they need to engage with and pass this stage in order to move to another more stable maturation state. Hence, they reactively and proactively engage. In the reactive mode of engagement, they bid for lower fees knowing that this is a temporary period that they can successfully overcome to transition to a more a stable stage. Ola explain this view:

“I just take the projects at annoyingly lower rates just so that I can build my ranking and profile on the website. I knew once I have a higher project completion rate and reviews, I’ll be able to charge more.”. - Ola

In the proactive mode of engagement, crowdworkers do not simply submit and conform to digital platforms’ ranking and rating systems, but actively influence them, focusing on the goal (Pollock et al., Citation2018). For example, some workers hire bots to constantly visit their platform profile and increase their ranking. Femi, a crowdworker for over five years, explains this

“The way the site works is that apart from the reviews, the algorithm works in a way that if it sees that you’re having a regular visit to your profile, it assumes that you’re an expert and that’s why you are having many profile views. So anytime someone search for maybe “PHP” or “Java” on the platform, it brings your name to the top of the list and through this employers assume you’re the best … You just have to pay $10 for some of these guys in India, the bot visits your profile continuously and it works well. I’ve used it a number of times”. - Femi

Some crowdworkers ask their friends to offer them a mock job, then rank them highly and praise them for completing it. Others intuitively predict employers’ selection behaviour and proactively present themselves in a way that will appeal to them. For example, they might build a female profile to appeal to employers’ perceived behaviour of trusting women and offering jobs to them. Ayodeji, a crowdworker with four years’ experience, explains this

“They [employers] always give the female preference over male, so when you create a female account, believe men or women, they’d rather give the job to women, although depending on the need they would rather give it to a female than a male. Imagine a data entry expert who is a male, and the other who is a female, they would rather give it to a female than give it to a male at some point in time, so to create an account we tend to use a female profile … .” -Ayodeji

While engaging proactively and reactively with the digital platforms’ rituals of algorithmic management (ranking, rating and recommendations), crowdworkers also find ways to overcome the precarious remote employment model of the digital platform and build more secure relationships with employers that are in line with the African business tradition of building social and individual relationships and direct connections (Asongu & Odhiambo, Citation2019; Kuada, Citation2009). Accordingly, crowdworkers immediately exchange their details and contact information with employers and continue to keep in touch after finishing a job for them. They use various digital means to do this, overcoming the constraints of the digital platforms. One way of exchanging contact information with employers while avoiding platform detection is described here by Apostle:

“Most platforms don’t want sharing of contact, it’s [forbidden] to exchange contact on the platform but … I type the email directly in the inbox (on the platform) … I will send my email [address] through a text [file], send it through a document, or a text, or a link.” – Apostle

Other crowdworkers use web links, instant messaging and mobile phone text messaging to initiate contact. Regardless of the digital means they employ to directly contact employers and bypass the mediation of digital platforms, crowdworkers in Nigeria find more security in building direct personal relationships with employers and consider it a key aspect of the work that has to be maintained despite the digital model of crowdwork. For example, Joseph describes how workers build long-term relationships with employers and make themselves informally approachable to employers:

“I have their contacts now … so I build relationship with this kind of people [employers], so when they need my services they have to call me or send message to me through WhatsApp so that I can do the job for them.”. - Joseph

In sum, while overcoming the precarity of the algorithmic management through proactive and reactive engagement with the platform, crowdworkers also overcome the precarity of the distant digital relationship with employers. They pursue more secure, culturally grounded practices consistent with their traditions and with their conventions and norms of doing business, as expressed by Adesola, who has two years’ experience:

“You must always keep close relationship with them [employers] … always tell them you’re available after working for them and then capitalize on it to use it judiciously so that we can keep a constant, close relationship with our client [employer] … So that many times they come back and say I need a job, get it done … they can easily come back to you, so we maintain a relationship, a solid one.” – Adesola

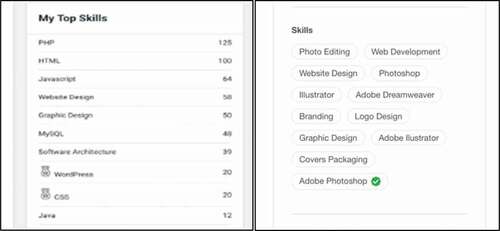

Moreover, workers overcome the insecurity of having one source of digital employment (i.e., one digital platform) by subscribing to several such platforms. They build different profiles depicting different sets of expertise that suit each digital platform. Each profile is based on an understanding of the most frequently offered tasks that could be competitive with low fees, and of niche areas that might be offered less frequently but are more financially rewarding. Across platforms, crowdworkers build a portfolio of profiles that could attract combinations of different types of jobs. shows a worker’s two profiles across two platforms and shows variations in fees and profits gained from a variety of tasks across different platforms.

5.3. Transformation and transition through communitas and wulunda (feeding together)

Crowdworkers reduce the precarity stemming from the individuality of crowdwork by developing comradeship with other crowdworkers, to support each other, share experiences, learn skills and be together socially. They do so using digital and/or physical strategies. For example, some crowdworkers create and/or are involved in WhatsApp groups with other crowdworkers. These groups are used almost daily to discuss issues and problems, exchange observations, give or receive hints, ask for help, or obtain assistance on a job they have successfully bid for but are unable to do by themselves. Ola describes his engagement in one of the WhatsApp groups:

“We have connections to each other and there’s a WhatsApp group with a few of us where we post projects when we need, questions and stuff like that”. - Ola

Another digital strategy adopted by crowdworkers to reduce the uncertainty of the individuality of work through comradeship is involvement in online forums, blogs and social media groups. In online forums, experienced crowdworkers share their knowledge and their own personal approaches, the tools they use, the problems they encounter, the solutions they have found, and the ideas that have worked best for them. Many crowdworkers find that their crowdwork is “only possible” through the insights they gain from these online forums and the experiences and knowledge shared by other crowdworkers. Femi and Daniel eloquently express the importance of this comradeship in their learning:

“Some experienced people share advice on how they started, what you should do, how you should speak with clients from different countries … You learn things like how you should address people with their first name if they have their names on their profile … I even learnt how to build my profile: I just copy what these people say has worked for them” – Daniel

These online forums serve as a learning hub for crowdwork novices. These novices read various forums and simply mimic the practices shared by established and experienced crowdworkers in order to better navigate the requirements and initial precarity of platforms and help them transition to a relatively more stable state. Crowdworker Ayodeji describes this process:

“I stumbled upon the crowdsourcing thread, and from there I learnt about it, and from people’s testimonies and their strategies and ideas I was able to pick, lead to a few, and from there I started researching on my own, and that’s how I got to become a crowdworker” - Ayodeji

In addition, social events and meet-ups in cafes and public places are organised through social media. The seminars and social events foster personal connections among crowdworkers and support their social bonding, overcoming the precarity of individualistic digital work. Ade describes this social bonding:

I met [another respondent] in one of the workshop training about six years ago, that’s how we became friends and now we are more like family. When you know other people doing the same job as you and you work with them, you can’t feel alone in this business [crowdwork]” - Ade.

5.4. Transformation and transition through developing knowledge and skills

To overcome precarity, crowdworkers aspire to maturation and associated stable status. In this regard, they acquire different types of knowledge and skills, including domain, platform and business skills (Elbanna & Idowu, Citation2021). These skills are developed through their involvement in crowdwork and supported by the comradeship and community they build and/or become part of. At the start of their crowdwork journey, crowdworkers typically create their first profile on a digital platform based on their existing set of skills and expertise at the time. Through the journey of understanding how digital platforms operate, the differences in the tasks they offer and the employers they attract, and their algorithmic management mechanism, crowdworkers strategically create profiles on many different platforms. These profiles emphasise different sets of skills that crowdworkers think will attract employers on each platform, and crowdworkers also create different profiles on the same platform to depict different skill sets. shows two different profiles for the same worker on two different platforms. Tunde explains this:

“One must be strategic with the platform we work on. For graphic design jobs, the best platform is Fiverr.com, that’s where the best graphics jobs are. And for software and web development work, Freelancer is the best place to meet clients … I do both graphics and web design, that’s why I use both sites in order to get the best of both [platforms].” - Tunde

Crowdworkers also regularly browse different job requests on digital platforms and observe which are popular jobs requests, highly paid jobs, unique jobs and regular jobs. This inspires them to learn new skills within their knowledge domain and expertise. This view is exemplified by this comment from Kingsley:

“As a crowdsourcer, when I see some job post online, it spurs me to go and learn those skills … I download books, watch YouTube tutorials … Most of the things that I do currently as a crowdworker, I had to learn on my own by seeing that they are skills employers need” -Kingsley

Crowdworkers’ understanding of the job market on each platform incites them to also expand their knowledge to other related domains. Ify, for example, explains how noticing popular requests had encouraged him to expand his knowledge from the technical domain of coding and developing software to the managerial domain of writing business cases and proposals:

“As a software engineer, I saw many projects where employers need people to write proposals for software development projects. I learnt it and now almost 40% of what I do is related to writing proposals and instruction guides for clients.” – Ify

In sum, crowdworkers believe that acquiring knowledge and learning new skills is part of their liminal journey, equipping them to transition towards stable employment and income on digital platforms.

5.5. Reincorporation: back to the accepted images of work

As they transition on digital platform work – from precarious, unstable income and employment towards stable employment and income across a portfolio of different levels of tasks, different platforms and different employers with whom they build relationships on and off digital platforms – crowdworkers find it desirable to reintegrate with their own societal norms. They opt for renting physical offices collectively and individually while continuing to pursue their essentially digital work. In doing so, they put an end to the socially liminal appearance of crowdwork and legitimise it as formal, respected office work. This transforms their social status from the “in-betweens” of digital platform workers, a status that needs to be covered up and presented as the more culturally recognised, accepted and stable social status of entrepreneurs and office workers. One of our participants, a crowdworker for three years, eloquently expresses this view:

“I have this small office I rent where I work … This work is serious business – you have to look professional. In Nigeria, people respect that … It feels different when I work in my office, I feel like any other person who is working in a company.”

Crowdworkers also attempt to transform crowdwork itself, not only by conducting it in physical public offices but also by following the business norms in Nigeria, observing typical office hours, wearing formal business attire and procuring business cards and labelled stationery. These practices help them to anchor crowdwork in a traditional business model, thus resolving another aspect of its precarity.

Moreover, crowdworkers transition to the social status of entrepreneurs through creating specialised crowdwork occupations of bidders and workers. Seniors will specialise in bidding to gain as many tasks as they can to subcontract to junior workers who are at the initiation stage of crowdwork against fees or profit margin. In doing so, they both reduce the uncertainty of starting crowdwork for others and become entrepreneurs and managers responsible for running their own business and employing others.

“This is what happens: I bid on as many projects as I possibly can, writing, Java, HTML, PHP, Python, designs, you name it. I don’t code Python so I send it to some of my guys who can do it. I pay them and get some profit from it.” Ola

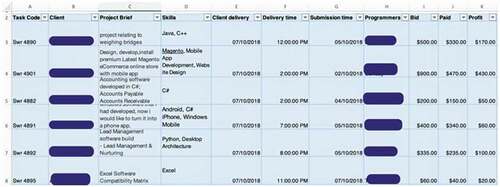

The transformation to entrepreneurs and bidders creates a need for crowdworkers to elevate their managerial skills. They learn to manage subcontractors, projects and finances and to create management artefacts and documentation systems for their personal use. shows part of one of the spreadsheets a crowdworker holds to manage crowdwork projects he owns and the subcontractors he manages. It shows the creation of a coding system for tasks along with deadlines, payments, profits and project-required skills. This spreadsheet complements a another “talent management” spreadsheet in which contact details and specialisations of different novice crowdworkers are kept.

Crowdworkers also make crowdwork retirement plan for themselves. Such retirement plans are typically gradual and allow crowdworkers to select a satisfactory end to their crowdwork liminal journey and achieve further work security in the future (Idowu & Elbanna, Citation2020). This is typically done by establishing crowdwork as a business, finance other business ventures from money earned from crowdwork or move to consulting or mainstream job market utilising the skills gained from crowdwork.

5.6. Reintegration: committing to social norms and family bonds (so called “black tax” system in the West)

When asked about job security, ageing and their pension plans, crowdworkers did not show concern and did not, for example, find a pressing need to have a formal pension scheme. Instead, they found security in their family and in the established norms and social protection mechanisms based on generational and family support. This view was expressed repeatedly by participants, and is eloquently summarised by Emeka and Adeshola, respectively:

“I’m my father’s retirement plan … When he was younger and in active service, he invested in his children’s education and took care of his aged parent. I’ll be responsible for him when he is not able to do anything for himself and I hope my children will do the same.” - Emeka

Studies have confirmed that in developing economies such as Nigeria, the family has been the key institution for the elderly, for their living arrangements and well-being (Albert & Cattell, Citation1994; Cowgill, Citation1986; Eboiyehi, Citation2015). This societal expectation is prevalent in African society and has been mistakenly described in the West as a “tax” on the individual, and termed “black tax” (Magubane, Citation2017; Matlala & Shambare, Citation2017). Black tax – as coined in the West – refers to the phenomenon in African societies in which employed and affluent individuals of working age are financially obliged to provide for their extended families and members of their in-group as part of the African collectivism culture (Abraham, Citation2017; Magubane, Citation2017; Matlala & Shambare, Citation2017). Crowdworker Joseph summarises this view:

“One thing we don’t do as Africans is neglect our aged parents and family, we support them … You know, I grew up with my grandparents living in our house so that we could keep an eye on them and take care of their needs. I remember every morning before school, it was my household chore to take their breakfast to their mini apartment that’s just beside ours … We all lived in the same compound.” - Joseph

Pension contributions are therefore viewed as a lower priority in Nigeria because retired people can expect to rely financially on the future contributions of younger members of the extended family and the in-group. Hence, crowdwork is likely to give a temporary advantage by providing a source of income for young people to care for themselves and their extended family and in-group. Ola, for example, expresses the importance of this work to him and others he knows

“This online work [crowdwork] is a hustle [job] that has saved a lot of people’s lives. Many are not thinking about a pension, they’re just happy to have something they are doing that’s bringing in good money.” – Ola

6. Discussion and theoretical contribution

Crowdwork has been widely adopted in both developed and developing countries. Research on crowdwork in developing countries imitates and reproduces its Western conceptualisation as precarious work, without in-depth investigation of workers’ lived experience (Beerepoot & Lambregts, Citation2015; Graham et al., Citation2017; Scholz, Citation2017; Wood et al., Citation2019). This study breaks this epistemological terra nullius through adopting in-depth worker-centric and context-specific approach to answer the question of how crowdworkers in Nigeria experience and respond to the employment conditions of crowdwork. Through the theoretical lens of the indigenous theory of liminality (Turner, Citation1974, Citation1987), the study conceptualises crowdwork as liminal digital work that puts crowdworkers “betwixt and between” formal traditional and informal employment. We argue that this liminal status does not necessarily lead to precarious work. The following sections unpack this argument and its implications and discuss the theoretical and empirical value of studying crowdwork and other ICTs in developing countries.

6.1. Agency of crowdworkers and the transformation of crowdwork

Crowdworkers in Nigeria embark on a liminal journey to transition and transform crowdwork from its initially insecure work conditions to a more stable culturally recognised form of work. They exercise agency and strong determination to transition from the “betwixt and between” status of crowdwork to stable long-term employment, drawing on their social norms and cultural heritage. In this liminal journey, they actively offset the digital platforms’ algorithmic management, employing other digital technology, such as bots, and non-digital social and cultural means, including friends and social relations. They also manage their presence and employment on digital platforms by subscribing to a range of platforms and creating different profiles, both on the same platform and on different platforms. In addition, they strategically bid low at the start of crowdworking to attract price-conscious employers and increase their ranking, as a temporary initial stage in building their transformational path. Once they pass the initiation stage and increase their ranking on the digital platform, they can ask for higher fees and expand their presence. These practices resemble the entrepreneurial spirit and habit of outsmarting the system to succeed in business endeavours (Fisscher et al., Citation2005).

Crowdworkers also actively learn new skills, expanding their domain knowledge and venturing into learning new domains. They exploit the information available on digital platforms to observe the frequency and popularity of job requests and understand the essential, desirable and competitive skills they should develop in order to attract more jobs (Elbanna & Idowu, Citation2021). They then proactively develop new skills and knowledge through self-learning, guided by the communities they create or become part of following their collective culture, as discussed in the next section. This gives them opportunities to change the nature of crowdwork by gaining more jobs, specialising in bidding and becoming contractors for other novice crowdworkers. Indeed, subcontracting is a well-documented progression in successful traditional freelance work (Kitching & Smallbone, Citation2012; McKeown, Citation2015). Crowdworkers also break away from the remote, exclusively digital nature of crowdwork to follow the cultural norm of having a physical office and establishing work relationships with employers. Moreover, they plan for the possibility of crowdwork retirement by pursuing parallel offline jobs. This is consistent with research findings in developing countries that show that people individually and collectively exhibit agency in closing gaps in resources (E. E. Osaghae, Citation1999b; E. Osaghae, Citation1999a; Trovalla & Trovalla, Citation2015).

These transitions and transformations present a picture of workers’ experiences that departs from the digital entrenchment assumptions underpinning the precarity and algorithmic control argument. Our approach of emphasising macrotask crowdwork and conducting in-depth examination of workers’ experiences in their local context and throughout their transitional phases yields conclusions that differ from the dominant Western conceptualisation of precarity and the static status of workers. This shows the importance of gaining an in-depth understanding of workers’ experiences of a particular type of crowdwork and of not categorising all crowdwork types and on-demand work types – with their different work conditions – under the vague umbrella terms of “gig economy” or “platform economy”. The findings confirm the recent general doubts expressed in research on the gig economy and platform economy that “dominant interpretations [of precarity and technological control] are insufficient” (Schor et al., Citation2020, p. 833) and also respond to the latest calls for specificity and in-depth understanding of gig workers (Dunn, Citation2020).

6.2. Crowdwork in developing countries: an opportunity to advance theory

In relation to macrotask crowdwork, the study shows that the digital nature of crowdwork brings about a fluid employment arrangement in which crowdworkers have to manage a nexus of “ambiguous” relationships (Valenduc & Vendramin, Citation2016), including between 1) crowdworkers and employers; 2) crowdworkers and digital platforms; and 3) crowdworkers and their social environment. These relationships have previously been conceptualised from the outset as precarious, from which the Western perspective draws conclusions describing crowdwork as precarious work and assumes the universality of this knowledge across cultures, histories and subjects. The findings show the liminal processes through which crowdworkers discard most of the precarious conditions of crowdwork, namely individuality, frequency of work, algorithmic management, virtual relations and vague social status. They reveal the agency of crowdworkers, not only in overcoming the signs of precarity but also in transforming crowdwork into more stable collective work that includes portfolios of tasks, client relationships, hierarchy and retirement plans, in addition to a culturally respected social status. In doing so, crowdworkers draw on their cultural heritage, conventions and social norms to enact a “rite of passage” transitioning through it to develop themselves and their communities.

In conceptualising crowdwork as liminal, this study offers a more inclusive view that accounts for the possibility of workers transitioning and transforming, as per the findings of this research, or to be digitally entrenched and trapped in it, as per the Western conceptualisation of precarity. This is consistent with Turner’s (Citation1969; Citation1987) conceptualisation of liminality as either transitional and temporary or a state in itself where it becomes permanent and frozen (Szakolczai, Citation2000, p. 220). This novel conceptualisation of crowdwork as a liminal experience recognises the key role played by workers’ agency, culture and social norms in crowdwork, despite its digital characteristics. It refutes the precarity argument, which offers a standardised perspective on the universality of the phenomenon and ignores the local conditions, traditions and economic compositions of different countries (Allison, Citation2014; Munck, Citation2013; Neilson & Rossiter, Citation2008). The current study shows that despite its fully digital nature and global reach, crowdwork cannot be separated from traditions, norms and the economy, and therefore generalisation across cultures, economies and “vastly different life circumstances” is problematic in projecting workers’ experience (Irani & Silberman, Citation2013).

Our study not only disputes the universality assumptions of crowdwork conceptualisations but also exposes other implicit assumptions that researchers risk when they uncritically apply the Western conceptualisation of precarity of crowdwork to developing countries. It makes explicit the implicit Western perceptions of crowdwork as static, digitally entrenched and individualistic work. This highlights the value of studying crowdwork in developing countries as a way of revealing hidden assumptions in Western scholarship and advancing theoretical understanding. Indeed, studying crowdwork in developing countries allows us to destabilise the knowledge production process and expose the conceptualisation of the phenomenon to new conditions that could unearth hidden assumptions and provide more depth to knowledge. compares some of the Western assumptions identified with the research findings.

Table 3. Underlying assumptions of Western conceptualisation compared with research findings

Our research shows that studying crowdwork in developing countries can not only produce more relevant knowledge to developing countries but can also significantly advance scholarship. The indigenous theorisation of this paper could be extended to other research on ICT in developing countries. Indeed, ICT research in developing countries could foreground context and delineate conditions of knowledge production to allow for in-depth examination of the phenomenon and take into serious consideration the lived experience of the people involved, beyond the pre-conceptualisation of dominant scholarship. ICT research in developing countries has a privileged opportunity to decouple the phenomenon from its knowledge production process to reveal hidden assumptions, and/or challenge many taken-for-granted assumptions. Thus, this indigenous theorisation advances scholarship and benefits businesses and policy makers in crafting relevant policies.

While the study contributes to the understanding of crowdwork as explained above, it also contributes to the theory of liminality. It takes this theory back to its origin in Africa. In doing so, it responds to the criticism of management and organisational research for forgetting the roots of the theory and calls for scholars to go back to its original formulation (Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018; Thomassen, Citation2012, Citation2015). We found the original formulation of the theory, which was embedded in African tribal rituals, useful in providing highly contextual analysis that attends to the details of the lives of those involved, uncovers the governing norms and practices that sustain social relations and structures, and emphasises the importance of the perspectives of those involved as sources of learning about crowdwork. This shows the generativity of adopting indigenous-rich theories.

Finally, the study provides a conceptualisation of crowdwork stemming from workers’ perspectives in a developing country beyond the dominant conceptualisation of precarity. In doing so, it responds to scholars who argue that the concept of precarious work is a “Eurocentric” concept and call for a “decolonial approach” (Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, Citation2010) to balance it with “contextual genealogy” from the Majority World beyond Europe (Munck, Citation2013). It also responds to calls to consider traditions and cultures in management studies (Lutz, Citation2009).

7. Conclusion, further research and practical implications

In conclusion, the research findings reveal that conducting crowdwork is context-dependent. Unlike previous scholarship on crowdwork, which has viewed Western precarity as a given when studying developing countries, this study offers a perspective from Africa and provides contextualised insights specific to its rich culture, socioeconomic conditions and the agency of workers that could be relevant to other developing countries. It reveals the workers’ agency in transitioning and transforming crowdwork into long-term employment benefiting from cultural heritage, social norms and traditions, in addition to the availability of parallel digital means. The study shows that the in-depth understanding of how crowdworkers respond to their work conditions could be fruitful for drawing conclusions on the impact of this work in a particular context. Our findings also reveal a number of implicit Western assumptions on crowdwork, including considering workers’ experiences to be static and frozen in time, and perceiving workers to be digitally entrenched in a single platform of work detached from other digital platforms, technologies and society. Moreover, the study reveals that the characteristics of crowdwork – that it is individualistic and fully digital, with only remote relationships with employers – are Western assumptions that could be materialised differently in practice. In addition, we show that context, culture and agency play important roles in workers’ lived experience beyond the façade of algorithmic management and assumptions of standardised work conditions.

Following inductive interpretive research, our findings generalise to theory (Lee & Baskerville, Citation2003, Citation2012). This theoretical generalisation is of practical importance. The research findings offer employers, digital platforms and policy makers a perspective on the conduct of crowdwork that informs the building of healthy working relationships. Digital platforms, policy makers, donors and international organisations that promote crowdwork should expand their programmes from simply encouraging more people to adopt it towards facilitating positive liminal experiences for crowdworkers in their context. However, the findings of this research do not generalise to population. Hence, they are not representative of crowdwork in Nigeria or Africa and in this regard can be seen only as indicative. For quantitative validity and generalisation to population, future research can adopt quantitative techniques including representative sampling and surveying methods. It should be noted that crowdwork could be a fluid phenomenon. While this research examines crowdwork at a particular time, future research could examine it in other periods. Future research could also examine the success and failure of crowdworkers’ trajectories to entrepreneurship (Idowu & Elbanna, Citation2020). While this study theoretically and empirically focused on macrotask crowdwork, future research could examine the applicability of its findings to and its conceptualisation in microtask crowdwork. Future research could also adopt post-colonial theory to further examine the disruption of colonial discourse and the production of differences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We use the term “developing country” to mean a less economically developed country. We are aware of the geopolitical term “Global South”, which emphasises power relations and the history of domination, and other terms such as “Third World” that emphasise periphery (Dados & Connell, Citation2012).

2. Indigenous theory is defined as “a theory of human behaviour or mind that is specific to a context or culture, not imported from other contexts/cultures and purposely designed for the people who live in that context or culture” (Davison & Díaz Andrade, Citation2018, p. 760).

3. For example, Kufuo, a user-interface designer in Ghana, told Anwar and Graham (Citation2021) that he is “earning twice [double] in comparison to his previous job as an app developer for a local start-up (Interview Accra, May 2017)”.

4. For example, this stage has been sometimes represented by the symbolism of a snake that is shedding its old skin while preparing for the new one to emerge.

References

- Abraham, I. (2017). The new black middle class in South Africa [book review]. Australasian Review of African Studies, 38(1), 136.

- Albert, S. M., & Cattell, M. G. (1994) Old age in global perspective: Cross-cultural and cross-national views.

- Allison, A. (2014). Precarious Japan. Duke University Press.

- Anwar, M. (2017). Digital gig work and outsourcing in Africa- update on geonet (Vol. 2017). Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford.

- Anwar, M. A., & Graham, M. (2020). Hidden transcripts of the gig economy: Labour agency and the new art of resistance among African gig workers. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(7), 1269–1291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19894584

- Anwar, M. A., & Graham, M. (2021). Between a rock and a hard place: Freedom, flexibility, precarity and vulnerability in the gig economy in Africa. Competition & Change, 25(2), 237–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1024529420914473

- Asongu, S. A., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2019). Challenges of doing business in Africa: A systematic review. Journal of African Business, 20(2), 259–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2019.1582294

- Barnard, H., Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Manning, S. (2017). Africa business research as a laboratory for theory-building: Extreme conditions, new phenomena, and alternative paradigms of social relationships. Management and Organization Review, 13(3), 467–495. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2017.34

- Beech, N. (2011). Liminality and the practices of identity reconstruction. Human Relations, 64(2), 285–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710371235

- Beerepoot, N., & Lambregts, B. (2015). Competition in online job marketplaces: Towards a global labour market for outsourcing services? Global Networks, 15(2), 236–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12051

- Berente, N., & Yoo, Y. (2012). Institutional contradictions and loose coupling: Postimplementation of NASA’s enterprise information system. Information Systems Research, 23(2), 376–396. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1110.0373

- Berg, J. (2016) Income security in the on-demand economy: Findings and policy lessons from a survey of crowdworkers. In: Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 74. International Labour Organization (ILO).

- Berg, J., Furrer, M., Harmon, E., Rani, U., & Silberman, M. S. (2018) Digital labour platforms and the future of work. International Labour Organization.

- Bhandari, R., Chatterjee, S., Gupta, K., & Panda, B. (2018). How to avoid the pitfalls of IT crowdsourcing to boost speed, find talent, and reduce costs (Vol. 2019). Mckinsey.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Terry, G. (2014). Thematic analysis. In P. Rohleder & A. C. Lyons (Eds.), Qualitative research in clinical and health psychology (pp. 95–114). Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Charmes, J. (2012). The informal economy worldwide: Trends and characteristics. Margin: The Journal of Applied Economic Research, 6(2), 103–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/097380101200600202

- Cheney, G. (2014) Alternative organization and alternative organizing. Critical Management. Retrieved 20 July 2020, from. http://www.criticalmanagement.org/node/3182

- Cowgill, D. O. (1986). Aging around the world. Wadsworth Inc.

- Dados, N., & Connell, R. (2012). The global south. Contexts, 11(1), 12–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504212436479

- Davison, R. M., & Díaz Andrade, A. (2018). Promoting indigenous theory. Information Systems Journal, 28(5), 759–764. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12203

- Davison, R. M., & Martinsons, M. G. (2016). Context is king! Considering particularism in research design and reporting. Journal of Information Technology, 31(3), 241–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.19

- De Stefano, V. (2015). The rise of the just-in-time workforce: On-demand work, crowdwork, and labor protection in the gig-economy. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, 37, 471. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_443267.pdf

- Deng, X., Joshi, K., & Galliers, R. D. (2016). The duality of empowerment and marginalization in microtask crowdsourcing: Giving voice to the less powerful through value sensitive design. Mis Quarterly, 40(2), 279–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2016/40.2.01

- Deng, X. N., & Joshi, K. D. (2016). Why individuals participate in micro-task crowdsourcing work environment: Revealing crowdworkers’ perceptions. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17(10), 648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00441

- Dunn, M. (2020). Making gigs work: Digital platforms, job quality and worker motivations. New Technology, Work and Employment, 35(2), 232–249. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12167

- Durward, D., Blohm, I., & Leimeister, J. M. (2020). The nature of crowd work and its effects on individuals’ work perception. Journal of Management Information Systems, 37(1), 66–95. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2019.1705506

- Eboiyehi, F. A. (2015). Perception of old age: its implications for care and support for the aged among the esan of South-South Nigeria. Journal of International Social Research, 8(36), 340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17719/jisr.2015369511

- Elbanna, A., & Idowu, A. (2021). Crowdwork as an elevator of human capital - a sustainable human development perspective. The Scandinavian Journal of Information Systems, 33(3). Forthcoming.

- Felstiner, A. (2011). Working the crowd: Employment and labor law in the crowdsourcing industry. The Berkeley Journal of Employment and Labor Law, 32, 143–203.

- Fisscher, O., Frenkel, D., Lurie, Y., & Nijhof, A. (2005). Stretching the frontiers: Exploring the relationships between entrepreneurship and ethics. Journal of Business Ethics, 60(3), 207–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-005-0128-1

- Gillwald, A., Mothobi, O., & Schoentgen, A. (2017). What is the state of microwork in Africa? A view from seven countries. In Policy paper. Research ICT africa. https://researchictafrica.net/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/After-Access_The-state-of-microwork-in-Africa.pdf

- Graham, M., Hjorth, I., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2017). Digital labour and development: Impacts of global digital labour platforms and the gig economy on worker livelihoods. European Review of Labour, 23(2), 135–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258916687250

- Gray, M. L., & Suri, S. (2019). Ghost work: How to stop silicon valley from building a new global underclass. Eamon Dolan Books.

- Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, E. (2010). Migration, domestic work and affect: A decolonial approach on value and the feminization of labor. Routledge.

- Heckathorn, D. D. (1997). Respondent-driven sampling: A new approach to the study of hidden populations. Social Problems, 44(2), 174–199. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3096941

- Heeks, R. (2017). Decent work and the digital gig economy (Vol. WP7). Global Development Institute. University of Manchester.

- Hodkinson, P. (2008). Grounded theory and inductive research. Researching Social Life, 3, 81–100. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/researching-social-life/book242913

- Howcroft, D., & Bergvall-Kåreborn, B. (2018). A typology of crowdwork platforms. Work, Employment and Society 33 (1): 21-38, 0950017018760136.

- Ibarra, H., & Obodaru, O. (2016). Betwixt and between identities: Liminal experience in contemporary careers. Research in Organizational Behavior, 36, 47–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.003

- Idowu, A., & Elbanna, A. (2020). Digital platforms of work and the crafting of career path: The crowdworkers’ perspective. Information Systems Frontiers. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10036-1

- Irani, L. C., & Silberman, M. S. (2013) Turkopticon: Interrupting worker invisibility in amazon mechanical turk. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 611–620.

- Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74(Feburary), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240907400101

- Kalleberg, A. L., & Vallas, S. P. (2018). Probing precarious work: Theory, research, and politics. Research in the Sociology of Work, 31(1), 1–30. https://arnekalleberg.web.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/7550/2018/01/Precarious-Work-CH-1.pdf

- Kässi, O., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2018). Online labour index: Measuring the online gig economy for policy and research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 137, 241–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.056

- Kitching, J., & Smallbone, D. (2012). Are freelancers a neglected form of small business? Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 19(1), 74–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211196415

- Kittur, A., Nickerson, J. V., Bernstein, M., Gerber, E., Shaw, A., Zimmerman, J., Lease, M., & Horton, J. (2013) The future of crowd work. Proceedings of the 2013 conference on Computer supported cooperative work, 1301–1318. ACM.

- Kshetri, N. (2019). Cybercrime and cybersecurity in Africa. Journal of Global Information Technology Management, 22(2), 77–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1097198X.2019.1603527

- Kuada, J. (2009). Gender, social networks, and entrepreneurship in Ghana. Journal of African Business, 10(1), 85–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228910802701445

- Lee, A. S., & Baskerville, R. L. (2003). Generalizing generalizability in information systems research. Information Systems Research, 14(3), 221–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.14.3.221.16560

- Lee, A. S., & Baskerville, R. L. (2012). Conceptualizing generalizability: New contributions and a reply. MIS Quarterly, 36(3), 749–761. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/41703479

- Lehdonvirta, V. (2016). Algorithms that divide and unite: Delocalisation, identity and collective action in ‘microwork’. In Flecker, Jorg (Ed.)., Space, place and global digital work (pp. 53–80). Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Levina, N., & Ross, J. W. (2003). From the vendor’s perspective: Exploring the value proposition in information technology outsourcing. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 331–364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/30036537

- Lutz, D. W. (2009). African Ubuntu philosophy and global management. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(3), 313–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0204-z