ABSTRACT

Fulfilment is a key driver for the digitalisation of the grocery sector and thus a major source of value creation. Although value creation is contingent on a multiplicity of contextual factors, extant research has mainly explored fulfilment in the generic realms of e-commerce and does not provide empirically grounded insights into the collective interplay of fulfilment attributes. Because e-grocery features unique exigencies and trade-offs that require non-generic theorisation, a functional and cross-domain perspective is required to comprehend the role of fulfilment in creating value in this sector. Following a multi-method approach, this paper combines a literature review with an empirical investigation of 111 e-grocers to produce three main outcomes. First, a conceptually-grounded and empirically-refined taxonomy to capture important decision attributes of e-grocery fulfilment. Second, six archetypes to indicate common combinations of these attributes. Third, a contingency model to disclose value relationships between attributes and outcome performance. Our results contribute to the body of knowledge on e-grocery value creation as well as the explanatory understanding of operational configurations and digital transformation conditions in this industry.

1. Introduction

The ubiquitousness of digitisation requires the retail sector to adapt its services, business model(s) and infrastructure (Trenz et al., Citation2020). Advancements in information technology (IT) have allowed retailers to integrate stationary infrastructure with online-channels and invent novel, pure-digital business models (Gu & Tayi, Citation2017). As a consequence, the online-channel has become indispensable for the retail landscape. Driven by changes in customer expectations and recent events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, e-grocery is a prospering retail opportunity space that yields economic and societal benefits (Milioti et al., Citation2021). With an increase of 1.2 billion USD from 08/2019 to 7.1 billion USD in 03/2021 (Statista, Citation2021) and a projected compound annual growth rate of 9.31% until 2030 (Verified Market Research, Citation2021), the e-grocery market is attractive for both, established brick-and-mortar retailers and digital players. Implementing novel business models or transforming existing e-grocery business models, however, is a complex task that is contingent on multiple factors. E-grocers need to reflect on specific challenges, including delivery constraints (e.g., preservation of fresh produce, Hays et al., Citation2005), diverse delivery schemes, limited shelf lives of perishables, and low margins (Enders & Jelassi, Citation2009). Accordingly, they face a heterogeneous set of options concerning order fulfilment in particular – a fact that is even accentuated in the digital age (Mithas et al., Citation2016; von Viebahn et al., Citation2020).

Information systems (IS) research has suggested that fulfilment attributes such as lead times can have a remarkable effect on the performance of online operations (Qureshi et al., Citation2009; Saeed et al., Citation2005). Yet, developing e-grocery fulfilment (EGF) strategies – the combination of attributes – is impeded through a series of context-dependent trade-offs. For example, the minimisation of inventory costs might lead to long lead times and vice versa, whereas short lead times require large quantities of stock. The impact of flawed decisions can be illustrated by various real-life examples, such as the Silicon Valley-based e-grocer Webvan. Webvan built fulfilment centres with advanced robot technologies to deliver groceries within 30 minutes of ordering. After being valued at 1.2 billion USD, Webvan went bankrupt within a few months. Among other reasons for their bankruptcy, they failed to balance efficiency and value creation. For instance, they built fulfilment infrastructure from scratch instead of using infrastructure through cooperation and they sold to the mass market instead of targeting upmarket consumers who would be more profitable in the face of low profit margins (Cleophas & Ehmke, Citation2014).

Because digital transformation can mitigate these trade-offs, choices made to achieve fulfilment efficiency need to be aligned with technological choices (Davis-Sramek et al., Citation2020; Milioti et al., Citation2021; Sandberg et al., Citation2014). Therefore, research stresses the importance of integrating digital transformation with order fulfilment (Lim et al., Citation2018). Given that “the grocery retail sector is generally known to pioneer the adoption of innovative technologies to enhance efficiency” (Kurnia et al., Citation2015, 1906), previous studies have contributed to our understanding of the use of digital technology for order fulfilment. Among others, this includes self-service technologies to increase shopping convenience (Saldanha et al., Citation2021) and Blockchain to foster process efficiency (Yacoub & Castillo, Citation2022). However, although several studies have attempted to conceptualise individual fulfilment attributes or supporting technologies (Appendix A), our review of the extant literature on value creation in e-grocery () indicates that research in this area is still fragmented.

Table 1. Contextual factors for value creation in e-commerce fulfilment.

Following calls to investigate the big picture (Hübner et al., Citation2016) and given that operational trade-offs confine value creation (Barua et al., Citation2004), there is a demand for a comprehensive understanding of EGF. Moreover, and even more importantly, in light of the immense number of EGF choices that can potentially be effective, it remains unclear as to why and how different combinations create value. IS scholars agree that value creation is contingent on a multiplicity of attributes and their interplay (Rai et al., Citation2012; Trenz et al., Citation2020). Yet, in the case of EGF, there is no holistic understanding of the effectiveness of EGF attributes and their interdependencies for value creation. This can be illustrated by looking at recent findings from research and practice, which have provided rather contradictory insights on individual attributes. For example, whereas Anshu et al. (Citation2022) and Qureshi et al. (Citation2009) highlighted delivery experience as a major driver of purchase intentions, Otim and Grover (Citation2006) did not uncover any effects of delivery arrangements on (re-)purchase intentions. Similarly, the use of automated fulfilment centres and short delivery lead times did not work out for the aforementioned e-grocer Webvan, whereas it is highly profitable for Amazon and Tesco (Cleophas & Ehmke, Citation2014). In response to the ambiguous knowledge base, there is an imminent need to conceptualise the combination of EGF attributes as an influencing factor for value creation in e-grocery.

Due to the plurality of feasible decisions as well as the highly dynamic environment (Van de Ven et al., Citation2013), this paper builds upon a contingency view (Luthans & Stewart, Citation1977). This view considers the individual business contexts in order to identify a combination of attributes capable of achieving an intended outcome. Researchers thereby develop functional relationships between the environment and the performance to cope with different situations (Miller, Citation1981). Following this idea, it is not about finding the one optimal combination of attributes, but rather a combination that reflects the current (external) setting and its goals (Turedi & Zhu, Citation2019). Consequently, we ask: What are the attributes of e-grocery fulfilment and how does their combination affect the value creation of an e-grocer?

Drawing upon interdisciplinary literature related to e-commerce, this paper opts to categorise EGF attributes and their combinations. By linking value creation to EGF attributes under consideration of fulfilment combinations, competitive focus, and organisational assets, we uncover distinct value relationships and provide a broad foundation for theorisation. For this purpose, we develop a contingency model for order fulfilment that relies on a review of 80 scientific literature sources and an empirical investigation of 111 e-grocers. The contribution of our paper is threefold. First, we organise EGF attributes through a taxonomy. Second, six EGF archetypes are proposed that represent the main contingency factors. Moreover, these archetypes advance the understanding of trade-offs and pave the way for designing comprehensive solutions for the digital transformation of the grocery sector. Third, we present a contingency model to disclose value relationships between EGF attributes and performance outcomes. This model elucidates the moderating role of EGF archetypes as well as archetype-related competitive focus and organisational assets as contingency factors for value creation in e-grocery.

In the ensuing sections, we first outline a synopsis of the related work and theoretical background to introduce the main constructs relevant to our contingency model. Following our research approach, we present the findings of our study. Finally, we discuss the paper’s implications and outline its limitations as well as future research directions.

2. Research background

2.1. Fulfilment-based value creation and influencing factors

The prosperity of e-commerce has fuelled scholarly interest in exploring online-channel value creation (Qureshi et al., Citation2009; Tan et al., Citation2016; Trenz et al., Citation2020). From our review of the extant literature on value relationships in e-commerce, we have found that fulfilment is essential for value creation (Bressolles & Lang, Citation2019; Davis-Sramek et al., Citation2020) and a prerequisite to successful transactions of any kind (Otim & Grover, Citation2006). Fulfilment not only fosters consumer trust (Shankar et al., Citation2002), but also impacts a company’s financial performance, operational costs, channel satisfaction and loyalty (Barua et al., Citation2004; Deng et al., Citation2010; Wollenburg, Hübner, et al., Citation2018). Thereby, its particular role and impact are contingent on numerous influencing factors, such as assortment size (Y. He et al., Citation2019), network effects (X. Luo et al., Citation2021), service technologies (Saldanha et al., Citation2021), and consumer habits (Zhang et al., Citation2021).

Owing to the competitive relevance of order fulfilment (Fang et al., Citation2021), the majority of work in the IS domain and adjacent fields elaborates on cause-effect relationships for service-related attributes. These range from general influencing factors that affect fulfilment performance to different value outcomes in the form of consumer responses to e-fulfilment and the organisational impact of specific e-fulfilment strategies (see overview in ). It illustrates that existing research has primarily focused on individual factors, rather than conceptualising fulfilment combinations (i.e., the interplay of attributes) holistically as a predominant moderator in the value creation process. Moreover, it shows that value creation and its influencing factors in the generic realm of e-commerce have been commonly investigated, whereas dependencies in the context of e-grocery are rather understudied. This is problematic as e-grocery significantly differs from other e-commerce contexts, such as fashion or electronics.

From a consumer viewpoint, grocery shopping involves repeatedly purchasing the same products with a low degree of involvement. In contrast to general online shopping, which produces feelings of enjoyment as customers look for novel or exclusive products (Jiang & Benbasat, Citation2007), grocery shopping is perceived as a routine task (Dawes & Nenycz-Thiel, Citation2014). Thus, a major reason for using e-grocery is its convenience in terms of speed, effort and flexibility (Trenz et al., Citation2020; Zhang et al., Citation2021), making service attributes such as delivery velocity highly important for competitive differentiation (Anshu et al., Citation2022). From an operational standpoint, the nature of the goods sold creates unique logistical challenges. EGF needs to ensure the visual and tactile integrity of fresh produce, while adhering to industry-specific regulations like maintaining the cold-chain (Hays et al., Citation2005). Contrary to traditional store-based fulfilment, e-fulfilment systems process a high number of orders with low product quantities (Bressolles & Lang, Citation2019). Thus, e-grocers need to mitigate cost pressure (Agatz et al., Citation2008; Enders & Jelassi, Citation2009).

Yet, the choice of EGF attributes entails operational and strategic trade-offs, including inventory and delivery costs or productivity and convenience (J. E. Scott & Scott, Citation2008). Consider, for example, the case of “click-and-pick” e-grocers, which collect groceries from third-party supermarkets and deliver them to the customers. On the one hand, this approach features distinct advantages such as large service areas with low financial requirements (due to the absence of own fulfilment infrastructure) and short lead times (due to a large network of fulfilment points). On the other hand, it also comes with limited control (due to the dependence on third parties), low operational efficiency (as order management routines are not aligned with delivery operations), and a high degree of competitive threat (as partnering supermarkets can choose to replace or discard their affiliates). Facing multiple fulfilment attributes, structural comprehension on an individual and a holistic basis is subject to intense research (Pereira & Frazzon, Citation2021; von Viebahn et al., Citation2020). Thus, in line with the unique business setting of e-grocery, there is a fundamental need to disclose and explain value relationships in this sector, rather than adapting insights from other e-commerce contexts.

Based on the extant literature on value relationships in e-commerce, we argue that the combination of fulfilment attributes and associated capacities constitute major contingency factors in the grocery sector. This is because the interdependencies of attributes and strategies are key influencing factors for a grocer’s online performance (Hulland et al., Citation2007; Otim & Grover, Citation2006; Qureshi et al., Citation2009). As an individual fulfilment attribute (e.g., fulfilment point) can influence value relationships in different ways, its impact on value outcomes can only be explained when considering a combination holistically. For instance, depending on the type of order reception, fulfilment from stores can either generate a low (in the case of self-collection) or a high degree of customer value (in the case of home-deliveries). In turn, these value relationships are subject to additional interdependencies and trade-offs (e.g., the competitive focus and organisational assets of an e-grocer).

Whilst the literature on e-grocery is advancing, it is still unclear as to where certain combinations fit better than others and which value outcomes are related to these combinations and associated capacities. Considering the heterogeneity of order fulfilment and related services (von Viebahn et al., Citation2020), it is important to integrate past findings into a model that explains how certain combinations influence the value outcomes holistically. In doing so, relevant trade-offs can be disclosed and the role of fulfilment for e-grocery success can be explained.

Focusing on the implications of EGF combinations, our research complements IS literature on multi- and omni-channel retail (Chen et al., Citation2018; Trenz et al., Citation2020), e-commerce value relationships (Fang et al., Citation2021; Polites et al., Citation2018), and digital technologies for order fulfilment (Cotteleer & Bendoly, Citation2006; Hardgrave et al., Citation2008). E-grocery value creation is an instance of e-commerce performance and design within a setting that combines IT-enabled customer value with operational elements. Therefore, it requires distinct theorisation within the IS literature. By organising e-grocery contingency factors, we create an understanding of the interrelationship between fulfilment and value outcomes (e.g., channel adoption and costs), which additionally lays the foundation for developing integrated IT solutions to meet the requirements of specific e-grocery business models.

2.2. Capacities and performance outcomes related to e-grocery fulfilment

Although the link between fulfilment and e-commerce success has been investigated in prior studies (Barua et al., Citation2004; Deng et al., Citation2010; Fang et al., Citation2021), there is scant research on value relationships in e-grocery. However, the distinct logistical requirements of grocery items (e.g., cooling) and the unique customer requirements create an environment where fulfilment is at the core of success (Boyer & Hult, Citation2006; Müller-Lankenau et al., Citation2005; Wollenburg, Hübner, et al., Citation2018). To address this, we conceptualise e-grocery value as an outcome that is contingent on EFG attribute combinations as well as the associated focus and assets of an e-grocer. This allows us to explore the potential impact on operational efficiency and customer value and improve the collective understanding of value creation in grocery.

2.2.1. Capacity constructs: focus and assets

Strategic integration refers to the harmonisation between organisational resources and competitive strategies and is vital for a company’s performance (Rivard et al., Citation2006). Although organisations require distinct assets to pursue a given strategy (Barney, Citation1991), resources per se do not explain the differences in a company’s performance, but rather the exploitation of these resources based on an e-grocer’s objectives and capacities (Boyer & Lewis, Citation2002). In e-grocery, resources are directly linked to strategy and business success (Lynch et al., Citation2000). Accordingly, competitive focus (i.e., objectives) and organisational assets (i.e., resources) need to be assessed collectively to elaborate on the interdependencies between individual EFG attributes and performance outcomes under consideration of attribute combinations and capacities.

In scientific research, the competitive operations focus of a company is commonly operationalised through competitive priorities. According to Krajewski and Ritzman (Citation2002), organisations can choose to prioritise costs, quality, delivery, and flexibility. The individual combination of priorities delineates a company’s logistics capacities and characterises its business strategy (Stock et al., Citation1998). When adopting a cost focus, e-grocers seek to compete based on low costs, for example, by reducing inventories or increasing productivity to minimise handling and transportation costs (Onstein et al., Citation2019). In turn, a quality focus describes the emphasis on EGF resources to compete on the basis of operational excellence (Krajewski & Ritzman, Citation2002). These organisations attach importance to capacities such as automation and staff training (Fernie et al., Citation2010; Hübner et al., Citation2016). As operational quality characteristics primarily relate to efficiency metrics (e.g., picking efficiency) in the value relationship between EGF attributes and performance (Boyer & Hult, Citation2006), we refer to this construct as efficiency focus in our contingency model. A delivery focus reflects an e-grocer’s intention to outperform the competition by offering superior (e.g., velocity) distribution routines (Krajewski & Ritzman, Citation2002). Nonetheless, with convenience and service level being the main differentiators for customer value in e-grocery (Anshu et al., Citation2022), we refer to this as service focus to highlight the role of service-related contingencies for value creation. Finally, flexibility focus represents the ability to (re-)deploy fulfilment resources in response to unforeseen changes (e.g., demand fluctuation) (Krajewski & Ritzman, Citation2002). Correspondingly, flexibility capacities include supply chain collaborations and internal infrastructure (e.g., delivery fleet) to enable an e-grocer to respond to changing exigencies (Fernie et al., Citation2010).

These competitive objectives can either complement or contradict each other. A pronounced focus on efficiency may help to foster other foci such as greater flexibility or lower costs. Thereby, trade-offs may arise that force e-grocers to prioritise based on the available distribution structures (Onstein et al., Citation2019). For instance, to minimise costs, e-grocers need to choose optimal order quantities, which jeopardise the availability of products and finally decrease the service focus.

In another capacity, EGF directly relates to physical and financial assets. Although the broad definition of assets additionally encompasses capabilities as intangible assets (Barney, Citation1991), we adopt a narrower definition for our contingency model. This allows for a clear distinction between assets and focus, which seems particularly suitable to explain contingencies in the case of EGF (Ellis-Chadwick et al., Citation2007). Physical assets can be defined as “stocks of available factors owned or controlled by the firm” (Amit & Schoemaker, Citation1993, p. 35). In the case of EGF, relevant physical assets include supermarkets, distribution facilities, inventories, IT systems, and delivery vehicles (Hübner et al., Citation2016; Prasarnphanich & Gillenson, Citation2003). Financial assets represent monetary resources to finance investments, capital, and business activities (Barney, Citation1991). They drive business performance by enabling companies to acquire physical assets to improve their operational capacities concerning costs, efficiency, service, or flexibility (Anckar et al., 2002; Mithas et al., Citation2016). Moreover, they can be employed to improve operational capacities directly, for example, when they are invested in staff training to drive flexibility. Correspondingly, assets are interrelated with each other and with the focus of an e-grocer.

2.2.2. Outcome constructs: operational efficiency and customer value

The purpose of aligning EGF combinations with competitive focus and organisational assets is to increase efficiency (Wollenburg, Holzapfel, et al., Citation2018). Different capacities have a direct impact on an e-grocer’s ability to handle orders (Boyer & Hult, Citation2006). A majority of e-grocers have been concerned with improving inventory, order, delivery, and return management practices to unlock potential efficiency gains and achieve a high degree of operational efficiency (Bressolles & Lang, Citation2019; Y. He et al., Citation2019). By considering the organisational value, operational efficiency reflects the internal value creation perspective in our contingency model that depicts the role of EGF archetypes as well as focus and assets for operational performance metrics (e.g., stock turnover rate).

Another higher-order outcome of an e-grocer’s focus and assets, which are related to its EGF combination, is customer value. It is defined as “the trade-off between the quality, or benefits, which the customer receives and the costs, such as monetary, energy, time and psychic transaction costs, which the customer incurs by evaluating, obtaining and using a product [or service]” (Chircu & Mahajan, Citation2006, p. 901). Because e-grocery service propositions directly depend on EGF attributes and their combinations (e.g., short lead-times require dense fulfilment networks and IT support), customer value is contingent on fulfilment structures (Boyer & Hult, Citation2006). Companies that can excel on post-purchase services are likely to create superior shopping experiences, which generate customer value (Saeed et al., Citation2005). In line with its inherent emphasis on market performance, customer value reflects the external value creation perspective in our model. It illustrates the impact of EGF archetypes and capacities on demand-related performance metrics, such as channel adoption, satisfaction, and loyalty.

2.3. Contingency theory

Facing a high number of decision attributes and the highly dynamic market situation, it is challenging to find an “optimal” strategy (Q. He et al., Citation2020; Zott & Amit, Citation2008). With the “growing demand for robust theorising and empirical research on new forms of organising ever-more-complex and dynamic situations” (Van de Ven et al., Citation2013, p. 394), contingency theory has received a resurgence. In the pursuance of contingency theory, organisations need to understand the variety of changing environmental contingencies and their dependencies to effectively align strategies with competitive surroundings (Crișan & Stanca, Citation2021; Iivari, Citation1992). There is, however, no single best way to do this because decisions made in some situations may not be successful in others as they are affected by several contingencies (Fiedler, Citation1964). Contingencies refer to any attribute that moderates the relationship between organisational characteristics and performance, such as organisation size, product variety, or service capacity (Turedi & Zhu, Citation2019). The theory argues that the most effective management concept depends on the set of circumstances at a particular point in time (Luthans & Stewart, Citation1977; Weill & Olson, Citation1989).

Referring to this paper’s context, we see similarities to contingency theory given that digital transformation in the e-grocery sector requires substantial changes, and e-grocers need to handle a variety of strategic options, particularly in the area of fulfilment. Yet, there are limited insights on trade-offs in implementing e-grocery business models and appropriate digitalisation strategies. Given the relevance of understanding the environment and aligning strategies accordingly, the theory has been employed in domains related to our context, including e-commerce (Giaglis et al., Citation2002), last-mile logistics (Lim et al., Citation2018), technology strategy (Teo & Pian, Citation2003), and digital transformation (Crișan & Stanca, Citation2021). The contingency theory lens offers an expedient framework to evaluate the multiplicity of EGF attributes and explain the corresponding value relationships in the e-grocery domain. In view of the fact that it theorises that organisational strategy and value creation depend on contextual conditions, we consider it as a viable underpinning to create a comprehensive understanding of the (potential) role of EGF archetypes and associated capacities for different value outcomes in e-grocery.

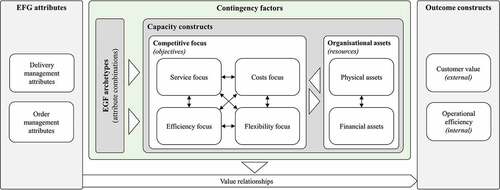

Building on the contingency lens, outlines the conceptual model for this study. We conceptualise value relationships based on attribute combinations from order management, which encompasses attributes that relate to backend operations (inventory handling, order preparation) and delivery management, which describes distribution characteristics (delivery planning, delivery operation, return handling) as well as from the focus and assets of e-grocers. These contingency factors moderate the relationship between individual fulfilment attributes of an e-grocer and the outcome constructs customer value and operational efficiency.

3. Research approach

3.1. Identifying e-grocery attributes

As a first step, we designed a taxonomy to disclose and organise e-grocery attributes (Nickerson et al., Citation2013) (see details in Appendix B). A taxonomy aids in structuring conceptual peculiarities and interdependencies (Wand et al., Citation1995), thus serving as a reference architecture that is suitable for comparing different conceptual elements such as fulfilment models. We performed two conceptual iterations in which we integrated attributes from prior conceptualisations and six empirical iterations in which we coded EGF instances obtained from the literature (Appendix C) and 111 e-grocers (Appendix D). Accordingly, we designed a conceptual-grounded taxonomy and extended it through an empirical investigation. The empirical focus corresponds to related studies dealing with creating taxonomies for strategic decisions (Malhotra et al., Citation2005; Segars & Grover, Citation1999).

In order to investigate the taxonomy’s usefulness, we evaluated its comprehensibility as well as its ability to support the classification of existing and the development of new EGF combinations through interviews and workshops (Kundisch et al., Citation2021). Here, we found (1) that e-grocers were able to classify their fulfilment strategies as well as (2) multiple statements from e-fulfilment specialists regarding the taxonomy’s high degree of practical usefulness (e.g., “[A] great tool to develop new fulfilment models in the grocery sector.”).

3.2. Developing EGF archetypes

Based on the taxonomy, we applied cluster analysis to extract common attribute combinations in the form of EFG archetypes (e.g., comparable to Vom Brocke & Lippe, Citation2011). Considering the number of compiled attributes, “clustering is the only method that can adequately construct the necessary typology” (Bailey, Citation1989, p. 17). We coded each of the final taxonomy’s attributes that was observable for one of the 111 e-grocers with a 1 and a 0 otherwise. As a result, a comprehensive classification of each of the e-grocers was created.

Unlike other studies that have derived clusters based on individual taxonomy dimensions to improve manageability (e.g., Malhotra et al., Citation2005), we conducted cross-dimensional cluster analyses with all attributes to grasp fulfilment-related trade-offs via useful archetypes. We followed a two-step clustering process, consisting of Ward’s (Citation1963) hierarchical clustering algorithm to identify the required number of clusters and K-means++ to assign e-grocers and attributes to the clusters. This procedure is widely accepted in IS research (Balijepally et al., Citation2011) and has been applied in similar research contexts with a moderate sample size and an extensive set of attributes (King & Sethi, Citation1999). Because the decision concerning the number of clusters entails conflicts between the solution’s manageability and the cluster’s homogeneity, we tested the robustness of the three- and six-cluster solution by comparing the means of each solution through K-means++. Although neither solution featured a significant difference for all attributes across all clusters, both showed a high degree of relative discriminatory power with significant differences across clusters (Appendix E.1). To account for the present and future EGF heterogeneity (Martín et al., 2019) and ensure that our empirical analysis represents a representative set of concept instances (Malhotra et al., Citation2005), our final selection of the six-cluster solution was then based on a priori theory (Ketchen et al., Citation1993).

To ensure external cluster validity, we conducted multiple evaluation episodes with seven representatives of an omni-channel-grocer, a pure-online-grocer, and three e-fulfilment specialists, who indicated that our findings are congruent with their operating models and likely to reflect common industry standards. Following the three think-aloud sessions and workshops that were conducted to evaluate the EGF taxonomy, we evaluated the archetypes through seven expert interviews and two workshops (Appendix B). First, during seven online interviews lasting between 21 and 45 minutes, the archetypes were introduced to the experts visually and verbally. Following Balijepally et al. (Citation2011), we asked participants to rate the applicability (“I find the archetypes useful”) and validity (“I think the archetypes show a realistic combination of EGF attributes”) on a five-point Likert-scale (1 – strongly disagree, 5 – strongly agree), indicating that the clusters are highly applicable (Ø 4.71) and valid (Ø 4.86). Second, during workshops (lasting between 44 and 96 minutes), which were performed with two representatives at the same time, practitioners were asked to use the archetypes to solve a fictive task. They collectively had to develop a fulfilment model for a grocery organisation planning to establish an online sales channel, while the main points of discussion were documented manually by the research team. Upon completion of the workshop, we collected verbal feedback on the applicability and usefulness of the archetypes for solving the task.

Based on the interview transcripts and the workshop logs, the feedback was consolidated and applied to improve the archetypes. Experts stressed the specific strategic relevance of the attribute combinations; for instance, concerning decision-making (e.g., “[A] great tool to find or refine a fulfilment strategy and establish competitive advantages.”). In other words, the archetypes provide support in the actual choice of EGF combination, identification of trade-offs and analysis of improvement potentials in a sense that provides competitive delimitation.

Afterwards, we employed abductive reasoning to derive the capacity constructs (i.e., focus and asset) for each of the derived archetypes based on the insights from the literature and the empirical analysis of e-grocers.

3.3. Deriving a contingency model

Finally, to theorise the value relationships, outcome constructs were identified by studying three selected e-grocers of each cluster through documentation and surveys. Operationalisation of the constructs was done via questionnaire items (measured on a 5-point Likert scale) that have been derived from literature: namely costs, productivity, stock turnover rates, and picking accuracy in the case of operational efficiency (Bressolles & Lang, Citation2019; Wollenburg, Hübner, et al., Citation2018), as well as delivery velocity, transaction costs, convenience, and product quality in the case of customer value (Chircu & Mahajan, Citation2006; Saeed et al., Citation2005).

A synopsis of the research process is given in (see Appendix B for a detailed overview of the entire research process).

4. E-grocery fulfilment archetypes

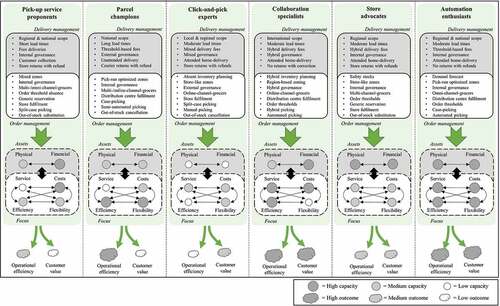

The focal centre points of each cluster depend on the attributes of the EGF taxonomy. synthesises the compiled order and delivery management attributes, including the respective occurrence frequency of an attribute across all e-grocers (see Appendix E.1 for individual frequencies per archetype). In a top to bottom sequence, the taxonomy reflects the journey of an order within the EGF process and comprises five meta-dimensions: Inventory handling covers relevant attributes around inventory planning, zoning of storage areas, governance of inventory, allocation of inventory to different business units, and inventory reservation times. Order preparation is composed of warehouse activities in which items are collected from their storage areas to physically prepare a customer order for shipping. It captures infrastructural attributes (e.g., point of fulfilment and degree of picking automation), procedural attributes (e.g., picking procedure and out-of-stock handling), and strategic attributes (e.g., fulfilment point governance and order threshold). The meta-dimension Delivery planning deals with planning tasks and frame conditions that are related to the physical delivery process of a grocery order. It involves, for instance, the delivery area in terms of geographical location and land arrangement, duration of lead-times, order packaging, delivery governance, and routing approaches. Delivery operations relates to the actual process of physical delivery, including information on the fleet that is to be utilised for the delivery process, cooling procedures, delivery intermediaries, tracking activities, and routines employed to hand over an order to a customer, as well as additional delivery services. Finally, Return handling describes the process of order retraction and complaint management. It differentiates attributes that are concerned with the return procedure, recovery for failures, and the integration of returned goods.

In the following section, we describe the EGF archetypes to improve the theoretical understanding of attributes, relationships, and trade-offs of different combinations for value creation (see Appendix C for a description of each attribute). An overview of real-world e-grocers for the six archetypes can be found in Appendix E.2.

4.1. Archetype #1 – Pick-up service proponents

These e-grocers have built on the provision of click-and-collect services that allow consumers to order groceries online and have them prepared for collection at store outlets, affiliated facilities or automated lockers. Compared to stationary shopping, this concept offers a high degree of access convenience. However, as multi- and omni-channel-practice, it requires a sophisticated network of physical assets. Typically, dedicated in-store collection facilities or service-oriented drive-in facilities are provided where pre-ordered items are directly loaded into the customer’s vehicle. Concomitant with the store-based reception type, store outlets, pick-run optimised front centres or an operational mix between store-outlets and distribution centres serve as main fulfilment points, with the e-grocer being in charge of inventory, fulfilment point, and delivery governance. The multi- and omni-channel grocers share inventories between offline- and online-channel and plan capacities based on demand forecasts or hybrid routines.

Orders are picked manually or semi-automated from individual store locations by piece or from front/distribution centres by case over a working day. Due to the fact that orders are collected rather than delivered, order thresholds are absent and lead-times between order placement and reception are short. Because of their sophisticated offline infrastructure, pick-up service proponents such as Delhaize in Belgium can offer grocery collection services on a regional and national scale. However, due to the manual, store-tailored operations, the preparation of individual orders for collection is labour-intensive. Hence, e-grocers adopt moderately long time-windows to capitalise on bundling effects and allow sufficient time for order preparation (Agatz et al., Citation2008). Given the absence of delivery operations, e-grocers frequently desist from charging additional service fees or offering hybrid incentives, whilst shorter lead times or narrower time windows are associated with dynamic pricing mechanisms. To cope with the lack of service value through deliveries, they provide additional services such as storage assistance. In order to ensure convenient collection, goods are wrapped in disposable packages such as plastic bags. With regard to complaint handling and return procedures, customers can directly claim a monetary refund from the collection location.

4.2. Archetype #2 – Parcel champions

Parcel champions rely on unattended deliveries with delivery boxes. They outsource the delivery governance to third-party couriers, which, depending on the respective delivery area and scope, employ light commercial vehicles (LCV) or heavy duty trucks (HDT) to transfer the items to their facilities close to the order recipient. Here, groceries are transshipped to LCVs and delivered to the customer. This archetype is operated by pure-online- and multi-/omni-channel-grocers, whereby the latter plan, utilise and pick inventories individually for offline- and online-channels (offline-channel: entire assortment; online-channel: dry foods). They benefit from reduced packaging requirements and costs as dry foods do not require cooling. In contrast, grocers with a larger product assortment, including fresh produce and chilled goods, need to invest in insulated packaging to maintain the cold chain. To achieve operational efficiency, parcel champions such as Rossmann (Germany) occupy pick-run optimised distribution centres. These are either centralised, decentralised and separated from offline-channels or decentralised and integrated into offline-channel operations. Orders are picked by case or pallet at generic times (perishables need to be prepared at different intervals to avoid spoilage), utilising semi- or fully-automated systems.

In order to cope with the requirements regarding physical (number/size of distribution centres) and technological (picking technology, channel-based order preparation) assets, this approach requires a sophisticated order management infrastructure (Wollenburg, Hübner, et al., Citation2018). In line with the courier-based nature of this concept, orders are shipped in reusable packages. Whereas courier companies provide estimated or real-time tracking information, e-grocers do not offer value-added delivery services themselves. Utilising the fulfilment infrastructure of delivery partners, parcel champions can benefit from efficient and reliable delivery routines, including dynamic routing, and can offer EGF on a national/international level for urban, sub-urban and rural areas. Nevertheless, relying on external partners to serve a large delivery area also entails drawbacks, because e-grocers are bound to the operational hours of their fulfilment partners and have to accept longer lead times and unspecific delivery windows. To account for the accruing delivery service costs, e-grocers raise dynamic threshold-, location- or subscription-based fees. For customers that opt to claim a refund, they either eschew return procedures and provide a claim-based, monetary compensation or offer returns via a designated courier.

4.3. Archetype #3 – Click-and-pick experts

Organizations in this cluster focus on outsourcing; inventories and fulfilment points of the pure-online-channel-grocers are governed by contractors or third-parties. Due to the implicated lack of control over stocks and fulfilment infrastructure, e-grocers generally refrain from sophisticated planning routines and handle out-of-stock situations by (partial) cancellation. Inventories are reserved at pre-designated time slots and picked from stores. E-grocers act as an intermediary between customers and supermarkets and manually pick online-orders by piece from selected outlets in close proximity to the recipient. Correspondingly, they predominantly serve local or regional areas, where the product reception is attended and items are delivered by cargo-bikes, crowd-shipping or LCVs. For national deliveries, third-party couriers are employed. As click-and-pick experts such as Com4Buy (Germany) are able to pick from a wide variety of third-party supermarkets, they can serve numerous delivery areas.

Although the widespread fulfilment point infrastructure and rigorous out-of-stock handling routines allow for short lead times and time windows, order reservation times, manual picking procedures, the absence of planning routines, and the need to rely on third-party couriers for national deliveries relativise these advantages and result in moderate lead times and delivery time slots. Moreover, click-and-pick e-grocers are dependent on the existing store infrastructure of the respective fulfilment points (Hays et al., Citation2005). Delivery services are either settled by a fixed service fee, a threshold-based pricing system or a hybrid pricing scheme (e.g., threshold-based/fixed pricing for local/regional consumers). Cooling requirements are met by employing cooling boxes or vehicles (local deliveries only). Regarding complaints and returns, click-and-pick experts either have service agreements with fulfilment partners that allow consumers to return items to the supermarket they have been picked from or refuse returns and provide an instant discount. Following the third-party based governance, return flows are generally separated from the e-grocer’s inventory system.

4.4. Archetype #4 – Collaboration specialists

Collaboration specialists leverage large partner networks and IT to ensure efficient order management routines, enabling geographically widespread deliveries. Depending on regional peculiarities and demand patterns, they operate a regional mix of inventory zoning approaches across a variety of decentralised distribution centres. Process and fulfilment automation require novel warehousing systems and penetrative organisational adaptations (Kembro & Norrman, Citation2021), whereas the management of large fulfilment networks is subject to mature communication and coordination (Pereira & Frazzon, Citation2021). Hence, this archetype is represented by pure-online-channel-grocers rather than multi-/omni-channel-grocers with established warehousing structures and a diversity of functional areas. Following the collaboration focus, inventories are reserved at specific, pre-scheduled times and picking processes are automated or semi-automated. Collaboration specialists such as Amazon Fresh and NetGrocer from the USA employ process automation in combination with an extensive delivery network to serve an international customer base with short lead times and moderate time windows.

Moreover, order thresholds and out-of-stock handling routines based on extended lead-times help to decrease handling costs. Because these kinds of operations and networks place a high demand on physical assets, collaboration specialists cooperate with third-party organisations in terms of inventory, fulfilment point and delivery management. Contingent on the geographical area, the availability of resources within that area and the prevailing customer density, the inventory, fulfilment point and delivery governance are either handled by the e-grocer (high customer density, availability of company resources) or an external partner (low customer density, absence of company resources). Delivery fees are charged dynamically or based on hybrid methods (e.g., reduced fees for urban subscribers). In order to further improve the flow of goods across the entire network and ensure short transit times, collaboration specialists employ stationary hubs as delivery intermediaries and transship orders with HDTs, before attended home-deliveries are conducted with LCVs or e-scooters. Cooling and packaging requirements are handled by insulated, reusable boxes or cooled vehicles and temporary transportation cases, which facilitate cross-docking and transshipment processes. Coinciding with their forward-oriented, large-scale distribution network, collaboration specialists do not offer product returns but provide monetary refunds, discounts or physical correction instead.

4.5. Archetype #5 – Store advocates

Omni-channel-grocers representing store advocates employ supermarkets as fulfilment and order management points and provide attended home-deliveries. E-grocers are responsible for inventory, fulfilment point and delivery governance. To leverage synergy effects resulting from integrated inventory handling (Agatz et al., Citation2008), inventories are shared between offline- and online-channels. Nevertheless, as picking and storing routines are administered manually in a given outlet with shelf-locations, inventories have to be reserved upon order occurrence. Order picking for offline operations is handled by customers themselves, for which reason the online-order picking management is separated from offline picking. Due to the large product assortment available in stores, out-of-stock situations are settled by substituting the respective product(s) with equivalent alternatives.

Compared to EGF archetypes that built on distribution centres, store fulfilment features a rather low degree of efficiency (J. E. Scott & Scott, Citation2008); this is compensated by high order thresholds and instance-based, threshold-based or hybrid delivery fee incentives. Depending on the scope of the existing supermarket network, store advocates offer local, regional and national deliveries to urban/sub-urban areas within 12 to 36 hours. In contrast to parcel champions, a unique selling point of store advocates such as Intermarche (France) is the provision of fresh produce and perishable items. To ensure excellent product quality, orders are delivered with cooled LCVs and routed dynamically to ensure fast deliveries (Agatz et al., Citation2008). Customers benefit from estimation-based tracking and, in high order-density regions, various value-added services. In the case of complaints or failures, they can return the respective item(s) through designated store outlets or instantly upon delivery. Failure recovery is handled by monetary refunds, discounts or hybrid strategies (customers keep faulty items and receive a discount).

4.6. Archetype #6 – Automation enthusiasts

Automation enthusiasts describe multi- and omni-channel-grocers and pure-online-players that rely on automated inventory handling and order preparation systems to ensure efficient processing routines. They operate pick-run optimised warehouses that are equipped with semi-automated or fully-automated picking technologies, thus enabling fast handling routines. In accordance with pick-run optimised inventory zones and a high degree of process automation, order picking is done by case and inventories are reserved directly upon order reception. Regarding out-of-stock situations, automation enthusiasts employ systems that automatically increase the lead-time for a given item when an out-of-stock situation is discovered or algorithmically anticipated. Given that automation enthusiasts scale capacity based on expected demand, utilise a high degree of automation, and establish region-based order thresholds, they can economically serve all delivery areas on a national scale (J. E. Scott & Scott, Citation2008). Contrary to collaboration specialists, automation enthusiasts such as Tesco (UK) do not manage external partner networks, they govern fulfilment points and deliveries themselves, and utilise centralised (highly automated) rather than decentralised distribution centres.

In order to secure fast delivery operations with lead-times under 12 hours, they operate hub-and-spoke networks. HDTs or LCVs with extensive transportation capacities are used to ship orders from the distribution centre to the stationary hub where they are transshipped to LCVs with multiple cooling mechanisms and delivered through attended reception. In line with the given delivery routines, consolidation objectives and the operational requirements of the hub-and-spoke networks, automation enthusiasts implement moderate time windows and dynamic routing procedures to minimise traffic delays. To compensate for the accruing handling costs, they charge delivery fees based on subscriptions, thresholds and lead-times, and countervail failures with monetary refunds or discounts.

5. Contingency model for e-grocery value creation

presents our contingency model, which is based on the archetypes and the associated capacities. The clustering points out that an EGF archetype is characterised by a magnitude of different, partially antithetical attributes. To improve conceptual understanding, we grouped attributes based on their operational scope. The combination of the fulfilment attributes for order and delivery management in each archetype forms the basis of a contingency model that is related to the focus (service, costs, flexibility, efficiency) and assets (physical, financial) of an e-grocer.Footnote1 In turn, archetypes and capacities are collectively linked in a trade-off relationship with operational efficiency and customer value, finally explaining e-grocery value creation. Next, we highlight differences in the manner in which the e-grocers manage fulfilment and explore value relationships based on the derived contingencies.

5.1. Cost emphasis by pick-up service proponents

The managerial focus of pick-up service proponents is reducing costs while maintaining a sound level of efficiency and flexibility. For this purpose, they leverage existing store infrastructure and offer order collection rather than home-deliveries to avoid additional logistics costs at the expense of added customer value. Similarly, demand forecasting and internal inventory governance help to choose appropriate order quantities, thus decreasing the relative inventory costs. However, this approach also jeopardises the availability of products, which negatively impacts service level and efficiency. Because they have established several routines fostering operational productivity (e.g., substituting products that are out-of-stock, shared inventory handling), these e-grocers still seem to focus on efficiency and flexibility to a moderate degree. In contrast, service-related attributes such as delivery services or short time windows are generally not implemented, revealing a lack of service focus. Finally, the scope of the delivery area, reception type, and delivery scope require a large network of individual store units, entailing a moderate demand on the physical assets (as fulfilment points are often, at least partially, governed by third parties) and a high demand on the financial assets of the e-grocer. As a consequence, the overall customer value provided by pick-up service proponents is rather low, which is compensated by a moderate degree of operational efficiency, enabling low operating costs.

5.2. Efficiency quest by parcel champions

Parcel champions appear to emphasise a particularly large delivery area. Delivery outsourcing and order management prioritisation allow efficient operations with moderate physical and financial assets. Because these e-grocers utilise integrated, decentralised fulfilment centres with dedicated, partially automated picking procedures and pick-run optimised inventory zones, they can flexibly react to changing demand patterns while maintaining a high level of productivity. Service appears to be a less important concern for parcel champions, which is evidenced by their lead-times, delivery time-windows, and delivery services. Hence, the overall outcome of this archetype is rather in favour of operational efficiency than customer value.

5.3. Purposeful waiver of control by click-and-pick experts

The physical and financial assets of click- and-pick experts appear to be limited, which these e-grocers compensate for by collaborating with local grocers to offer delivery services from facilities that are governed externally. On the one hand, the delivery services and governance model of this approach indicate a moderate degree of service, cost, and flexibility focus. On the other hand, it neither enables the alignment of order management routines with e-grocery operations, nor allows for the planning of inventories or the optimisation of pick-runs. Accordingly, click-and-pick experts appear to exchange operational efficiency for a minimum demand on assets, still allowing these e-grocers to provide a decent level of customer value based on their order and delivery management attributes.

5.4. Pursuit of service quality and efficiency by collaboration specialists

As indicated by their value-adding delivery services (e.g., moderate time-windows, short lead times, attended deliveries, the provision of replacements or refunds without the need for customers to return a faulty item) and productive order management routines (e.g., hybrid inventory planning, region-based inventory zoning, decentralised distribution, hybrid governance), collaboration specialists set the emphasis on high service levels, while at the same time trying to maximise efficiency and minimise costs. To achieve high degrees of operational efficiency and customer value, they cooperate with numerous external partners, ultimately decreasing the demands on physical assets at the cost of increased management and coordination requirements as well as reduced control. As their operations rely on partnerships to a great extent, their focus on flexibility appears to be rather low. In conclusion, the fulfilment characteristics of collaboration specialists necessitate high financial assets (e.g., due to human resource costs required for coping with the operational and managerial efforts) and moderate physical assets (e.g., in terms of fulfilment infrastructure). However, they also allow these e-grocers to simultaneously pursue multiple operational goals and excel on both, operational efficiency and customer value.

5.5. Exploitation of synergies by store advocates

Store advocates leverage a sophisticated store network to cover the targeted delivery area. They opt to capitalise on synergies from integrated order management procedures and emphasise multi- rather than omni-channelling. In contrast to pick-up service proponents, they govern inventories and fulfilment points internally and offer attended home-deliveries to provide additional customer value. Thus, despite a rather local delivery area, distinctive physical and financial assets seem to be necessary to operate this model and cope with the operational requirements. It appears that they have a balanced focus on service, cost, flexibility and efficiency, though in all cases this is moderate as store advocates operate the online business as a complement to the offline business unlike online-only providers such as collaboration specialists. In line with their balanced focus on competitive value creation factors, store advocates achieve a moderate degree of operational efficiency and provide a medium level of customer value.

5.6. Value creation through technological excellence by automation enthusiasts

Finally, automation enthusiasts focus on service, costs, efficiency, and flexibility to an equally large extent. As omni-channel-grocers, they seek to create an integrated shopping experience for their customers across all channels. Hence, they also attach a lot of importance to their online-channel and opt to excel on all relevant competitive priorities. They utilise automated, technically-assisted order and delivery management routines, featuring a high degree of control as well as extensive demands on physical and financial assets. Their fulfilment model, consisting of sophisticated order (e.g., automated picking) and value-adding delivery management attributes (e.g., short lead-times), suggests a high demand on financial assets (e.g., to invest in and maintain automation technology) and physical assets (e.g., storage robots, delivery fleet). Ultimately, their capacities in terms of cost minimisation, maximisation of efficiency and flexibility, as well as provision of additional service value allow automation enthusiasts to deliver salient value outcomes in terms of operational efficiency and customer value.

6. Discussion

Fulfilment is understood as a major factor for value creation in e-commerce. Whilst prior research has tended to examine individual fulfilment attributes in the generic realms of e-commerce, we presented a holistic contingency model that captures the relationships between diverse fulfilment attributes and value outcomes in the e-grocery domain. Next, we discuss the main implications for theory and practice.

6.1. Theoretical implications

Structuring the solution space of EGF decisions attributes. The theoretically-grounded and empirically-refined taxonomy organises relevant attributes for e-grocery. As “theory for analysing” (Gregor, Citation2006), our findings add descriptive knowledge to several IS research streams, including multi- and omni-channel commerce (Chen et al., Citation2018; Trenz et al., Citation2020) and digital technologies for order fulfilment (Cotteleer & Bendoly, Citation2006; Hardgrave et al., Citation2008). Our attributes share similarities with, for instance, work on logistics (e.g., delivery times, Lim et al., Citation2018), supply chains (e.g., supplier coordination, Iyer et al., Citation2009), and IT (e.g., technologies used, Weill & Olson, Citation1989). Contrarily, our taxonomy has unique attributes, such as “order cooling”, and more contextualised ones, including “picking technology” as an instance of technology and “delivery lead times” for order handling.

By focusing on the grocery context, our results advance and contextualise the rather isolated landscape of research on generic e-commerce. Context appreciation is important for reflection on digital options (Sandberg et al., Citation2014) as well as for contingency theory, which argues for considering the specific surroundings (Crișan & Stanca, Citation2021; Miller, Citation1981). Moreover, the compiled attributes and archetypes help to establish a shared, cross-disciplinary understanding of EGF, facilitating knowledge sharing and accumulation.

Assembling EGF archetypes. Building upon the taxonomy, we discovered common combinations of EFG attributes and conceptually enriched these combinations with associated capacities. Existing fulfilment classifications include general distribution models (e.g., Agatz et al., Citation2008) and typologies for a particular function, such as warehousing (Kembro & Norrman, Citation2021) or last-mile distribution (Hübner et al., Citation2016). By deriving archetypes that capture attributes across the entire fulfilment cycle, we complement these streams and help to detect interdependencies that can be subject to future investigation. For instance, when designing and implementing digital technologies to support fulfilment, the underlying attributes, capacity constructs, and value outcomes need to be aligned with the situation at hand. Our archetypes conceptualise operational characteristics and activities to identify trade-offs and strategize digital transformation transactions (e.g., Matt et al., Citation2015) in the grocery sector. As an example, store advocates will require technical order management solutions, such as RFID or ERP systems, to integrate information flows along the e-grocer’s sales touchpoints (Wamba & Chatfield, Citation2009).

Handling the interplay of attributes in a specific context. Following the underpinning assumptions from contingency theory, the business’s goals need to the aligned with the environment to make appropriate decisions (Crișan & Stanca, Citation2021). By disclosing relationships between EGF attributes and value creation based on EGF archetypes and capacities, our study advances IS research on e-commerce value relationships and adoption (Fang et al., Citation2021; Pavlou & Fygenson, Citation2006; Polites et al., Citation2018) and aids future research in adopting a more comprehensive view of value creation in e-grocery.

For illustration, we have shown that automation enthusiasts such as Tesco feature a high degree of operational efficiency and customer value, which coincides with the paradigm that order fulfilment performance is often driven by technology (Kembro & Norrman, Citation2019). Automation enthusiasts possess a logistics automation capacity profile, representing the “ability of interfirm logistics relationships to automate package labelling, schedule pickup/delivery times for shipments, and specify special processing requirements” (Rai et al., Citation2012, p. 240). Collaboration specialists achieve customer value and operational efficiency by leveraging an extensive partner network but need to be aware of the fact that today’s partners can become tomorrow’s competitors (Etzion & Pang, Citation2014). As opposed to other archetypes that also use collaboration (e.g., click-and-pick experts), the fulfilment operations of collaboration specialists feature unique exigencies, which can be evaluated via the proposed contingency model. Hence, our results complement existing findings on the interplay of attributes (e.g., Eriksson et al., 2019; Kembro & Norrman, Citation2021) by presenting archetypes across the entire fulfilment cycle as well as emphasising capacities, potential implications and trade-offs. Thereby, we help generate theory that informs how to support EGF approaches more efficiently.

6.2. Managerial contributions

Create value through EGF combinations. Our study has relevant practical implications for the design and implementation of EGF, especially in the digital era. The archetypes assist in selecting appropriate means of interaction, for instance in terms of partner networks or digital technologies, or deciding on an appropriate degree of automation and autonomy. By uncovering EGF archetypes, managers are enabled to holistically understand how fulfilment-based value creation can be affected by shortcomings in organisational capabilities and a lack of planning. As e-grocers seek to identify suitable fulfilment options, the interplay of attributes and their trade-offs present a major challenge.

Contextualise EGF choices. Our paper provides an outline of available options and helps e-grocers to align online-channels with their contexts. The contingency model can be used to assess the trade-offs between alternative operational setups and to make purposive design choices for EGF in their specific environment. Hence, our findings respond to practical challenges, including the demand for environmentally-friendly deliveries (Milioti et al., Citation2021).

6.3. Limitations and outlook

Like all research, our study has limitations that open avenues for future research. First, although several similarities between the e-grocery context and contingency theory can be made, the selection is based on own decisions. Despite matching our objective, one might want to rely on other theories, such as configuration theories that argue for multiple conditions and paths to achieve a certain state of performance (McLaren et al., Citation2011) or strategic choice theory to explore the role of leading groups on decisions (Turedi & Zhu, Citation2019). Nonetheless, contingency theory offers a valuable view on dynamic situations and is considered as a foundation that can be complemented through additional perspectives, such as configuration theory (Van de Ven et al., Citation2013). Second, contingency theory does not provide causality (Weill & Olson, Citation1989), which is why future research can prioritise the impact of certain options. Besides, the archetypes are based on the assumption that only one fulfilment structure may be adopted for a given scenario; in some markets, it is common to concurrently operate multiple fulfilment structures, which requires investigation of the interrelationships between the combinations. Third, our taxonomy represents the status quo of attributes in practice and literature. In terms of knowledge evolution, our results serve as a starting point for further investigation. Fourth, our sample of e-grocers was limited to 111 instances, thus it cannot be claimed to be exhaustive. To overcome this, we used techniques for triangulation that increase the result’s robustness. Nevertheless, future studies with larger sample sizes, country-specific samples, or e-grocers from emerging economies will be needed for additional validation. Also, although our sample only includes extant providers, this industry is highly dynamic, especially since COVID-19. Fifth, our paper was a cross-sectional rather than a longitudinal study, which uncovered archetypes of e-grocery, but did not investigate how and why enterprises switch from one archetype to another.

7. Conclusion

Fast-changing environments and quickly evolving technology-driven phenomena require organisations to consciously adapt decisions to survive in today’s dynamic markets. Although there is no single best option for aligning an e-grocery archetype with its environment, understanding the set of choices and their relations is a prerequisite to making (better) decisions. To foster this, our paper investigates relationships between EFG attributes and value outcomes. Thereby, we disclose promising indications assisting e-grocers to leverage the full potential of the emerging stream of digital transformation in grocery and establish a sustainable source of customer value. This will help to increase the overall popularity of e-grocery in the medium-term and provide worthwhile advantages for society and environment. Moreover, we hope that our study motivates other scholars to adopt and test the proposed archetypes and contingency model to create more holistic, generalisable knowledge on the increasingly important topics of (digital) fulfilment in general and EGF in particular.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. As we derived focus and asset capacities conceptually and did not directly observe or measure their development extent, these items are outlined in a dotted box ().

References

- Agatz, N. A., Fleischmann, M., & Van Nunen, J. A. (2008). E-fulfilment and multi-channel distribution: A review. European Journal of Operational Research, 187(2), 339–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2007.04.024

- Alagarsamy, S., Mehrolia, S., & Singh, B. (2021). Mediating effect of brand relationship quality on relational bonds and online grocery retailer loyalty. Journal of Internet Commerce, 20(2), 246–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332861.2020.1868213

- Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. (1993). Strategic assets and organizational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140105

- Anshu, K., Gaur, L., & Singh, G. (2022). Impact of customer experience on attitude and repurchase intention in online grocery retailing: A moderation mechanism of value Co-creation. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102798

- Bailey, K. D. (1989). Constructing typologies through cluster analysis. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology, 25(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/075910638902500102

- Balijepally, V., Mangalaraj, G., & Iyengar, K. (2011). Are we wielding this hammer correctly? A reflective review of the application of cluster analysis in information systems research. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 12(5), 375–413. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00266

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Barua, A., Konana, P., Whinston, A. B., & Yin, F. (2004). Assessing internet enabled business value: An exploratory investigation. MIS Quarterly, 28(4), 585–620. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148656

- Boyer, K. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2006). Customer behavioral intentions for online purchases: An examination of fulfillment method and customer experience level. Journal of Operations Management, 24(2), 124–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2005.04.002

- Boyer, K. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2002). Competitive priorities: Investigating the need for trade‐offs in operations strategy. Production and Operations Management, 11(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1937-5956.2002.tb00181.x

- Bressolles, G., & Lang, G. (2019). KPIs for performance measurement of e-fulfillment systems in multi-channel retailing: An exploratory study. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 48(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-10-2017-0259

- Chen, Y., Cheung, C. M., & Tan, C. W. (2018). Omnichannel business research: Opportunities and challenges. Decision Support Systems, 109, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2018.03.007

- Chircu, A. M., & Mahajan, V. (2006). Managing electronic commerce retail transaction costs for customer value. Decision Support Systems, 42(2), 898–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2005.07.011

- Cleophas, C., & Ehmke, J. F. (2014). When are deliveries profitable? Business & Information Systems Engineering, 6(3), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-014-0321-9

- Cotteleer, M. J., & Bendoly, E. (2006). Order lead-time improvement following enterprise information technology implementation: An empirical study. MIS Quarterly, 30(3), 643–660. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148743

- Crișan, E. L., & Stanca, L. (2021). The digital transformation of management consulting companies: A qualitative comparative analysis of Romanian industry. Information Systems and E-Business Management, 19(4), 1143–1173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-021-00536-1

- Davis-Sramek, B., Ishfaq, R., Gibson, B. J., & Defee, C. (2020). Examining retail business model transformation: A longitudinal study of the transition to omnichannel order fulfillment. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 50(5), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-02-2019-0055

- Dawes, J., & Nenycz-Thiel, M. (2014). Comparing retailer purchase patterns and brand metrics for in-store and online grocery purchasing. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(3–4), 364–382. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.813576

- Deng, L., Turner, D. E., Gehling, R., & Prince, B. (2010). User experience, satisfaction, and continual usage intention of IT. European Journal of Information Systems, 19(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2009.50

- Ellis-Chadwick, F., Doherty, N. F., & Anastasakis, L. (2007). E-strategy in the UK retail grocery sector: A resource-based analysis. Managing Service Quality, 17(6), 702–727. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520710835019

- Enders, A., & Jelassi, T. (2009). Leveraging multichannel retailing: The experience of Tesco.Com. MIS Quarterly Executive, 8(2), 89–100.

- Etzion H., & Pang M. (2014). Complementary Online Services in Competitive Markets: Maintaining Profitability in the Presence of Network Effects. MIS Quarterly, 38(1), 231–248. 10.25300/MISQ/2014/38.1.11

- Fang, Z., Ho, Y. C., Tan, X., & Tan, Y. (2021). Show me the money: The economic impact of membership-based free shipping programs on e-tailers. Information Systems Research, 32(4), 1115–1127. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2021.1001

- Fernie, J., Sparks, L., & McKinnon, A. C. (2010). Retail logistics in the UK: Past, present and future. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 38(11/12), 894–914. https://doi.org/10.1108/09590551011085975

- Fiedler, F. E. (1964). A contingency model of leadership effectiveness. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 1, 149–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60051-9

- Giaglis, G. M., Klein, S., & O’keefe, R. M. (2002). The role of intermediaries in electronic marketplaces: Developing a contingency model. Information Systems Journal, 12(3), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2575.2002.00123.x

- Gregor, S. (2006). The nature of theory in information systems. MIS Quarterly, 30(3), 611–642. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148742

- Gu, Z. J., & Tayi, G. K. (2017). Consumer pseudo-showrooming and omni-channel placement strategies. MIS Quarterly, 41(2), 583–606. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.2.11

- Hardgrave, B. C., Langford, S., Waller, M., & Miller, R. (2008). Measuring the impact of RFID on out of stocks at Wal-Mart. MIS Quarterly Executive, 7(4), 181–192.

- Hays, T., Keskinocak, P., & De López, V. M. (2005). Strategies and challenges of internet grocery retailing logistics. In Applications of Supply Chain Management and E-commerce Research (pp. 217–252). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-23392-X_8

- He, Y., Guo, X., & Chen, G. (2019). Assortment size and performance of online sellers: An inverted U-shaped relationship. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 20(10), 1503–1530. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00576

- He, Q., Meadows, M., Angwin, D., Gomes, E., & Child, J. (2020). Strategic alliance research in the era of digital transformation: Perspectives on future research. British Journal of Management, 31(3), 589–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12406

- Hübner, A., Kuhn, H., & Wollenburg, J. (2016). Last mile fulfilment and distribution in omni-channel grocery retailing. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 44(3), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-11-2014-0154

- Hulland, J., Wade, M. R., & Antia, K. D. (2007). The impact of capabilities and prior investments on online channel commitment and performance. Journal of Management Information Systems, 23(4), 109–142. https://doi.org/10.2753/MIS0742-1222230406

- Iivari, J. (1992). The organizational fit of information systems. Information Systems Journal, 2(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2575.1992.tb00064.x

- Iyer, K. N., Germain, R., & Claycomb, C. (2009). B2B e-commerce supply chain integration and performance: A contingency fit perspective on the role of environment. Information & Management, 46(6), 313–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2009.06.002

- Jeyaraj, A., Raiser, D. B., Chowa, C., & Griggs, G. M. (2009). Organizational and institutional determinants of B2C adoption under shifting environments. Journal of Information Technology, 24(3), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2008.22

- Jiang, Z., & Benbasat, I. (2007). Research note—investigating the influence of the functional mechanisms of online product presentations. Information Systems Research, 18(4), 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1070.0124

- Kembro, J. H., & Norrman, A. (2019). Exploring trends, implications and challenges for logistics information systems in omni-channels: Swedish retailers’ perception. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 47(4), 384–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-07-2017-0141

- Kembro, J. H., & Norrman, A. (2021). Which future path to pick? A contingency approach to omnichannel warehouse configuration. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 51(1), 48–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-08-2019-0264

- Ketchen, D. J., Jr., Thomas, J. B., & Snow, C. C. (1993). Organizational configurations and performance: A comparison of theoretical approaches. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1278–1313. https://doi.org/10.2307/256812

- King, W. R., & Sethi, V. (1999). An empirical assessment of the organization of transnational information systems. Journal of Management Information Systems, 15(4), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.1999.11518220

- Krajewski, L. J., & Ritzman, L. P. (2002). Operations management: Strategy and analysis. Prentice Hall.

- Kundisch, D., Muntermann, J., Oberländer, A. M., Rau, D., Röglinger, M., Schoormann, T., & Szopinski, D. (2021). An update for taxonomy designers. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 64(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-021-00723-x

- Kurnia, S., Choudrie, J., Mahbubur, R. M., & Alzougool, B. (2015). E-commerce technology adoption: A Malaysian grocery SME retail sector study. Journal of Business Research, 68(9), 1906–1918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.12.010

- Lee, J., Pi, S., Kwok, R., & Huynh, M. (2003). The Contribution of Commitment Value in Internet Commerce: An Empirical Investigation. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 4(1), 39–64. 10.17705/1jais.00029

- Li, H., Fang, Y., Lim, K. H., & Wang, Y. (2019). Platform-based function repertoire, reputation, and sales performance of e-marketplace sellers. MIS Quarterly, 43(1), 207–236. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2019/14201