ABSTRACT

High streets across Europe continue to lose consumers to online retail, leading to business closures and the decline of city centres, impairing cities’ overall liveability. To counter this vicious cycle, our study presents smartmarket2, the first instantiation of a digital actor engagement platform designed specifically for high streets. smartmarket2 enables hybrid online-offline customer journeys by connecting consumers to stores and other high street service providers. In an action design research (ADR) project, we design, implement and evaluate smartmarket2, involving 150 high street operators and 2,300 citizens in three cycles of building, intervention and evaluation. We derive four design principles that contribute prescriptive knowledge on the design of digital actor engagement platforms. Our results reveal that such a platform is able to increase engagement, but that it is subject to actors’ engagement dispositions.

1. Introduction

High street retail has come under immense pressure from online platforms, a phenomenon further intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Declines in turnover and revenue of small- and medium-sized (SME) enterprises (HDE, Citation2018) have significantly reduced the number and diversity of stores, and, consequently, the number of high street visitors, in a vicious cycle (Hart et al., Citation2013).

Information Systems (IS) research and neighbouring disciplines have proposed two technology-based solutions for retailers to overcome this vicious cycle. The first would involve digital technologies to improve customer’s in-store experience (Grewal et al., Citation2020; Lemke et al., Citation2011; Verhoef et al., Citation2009). For example, location-based advertising (LBA) (Bellavista et al., Citation2008) can help visitors find products more easily, saving them money and time. Simultaneously, retailers benefit from prolonged visiting times and rates, and an increased chance of purchases being made (Molitor et al., Citation2016, Citation2018). Despite high expectations vested in LBA, it has not diffused successfully because of retailers’ lack of technical capabilities and visitors’ data privacy concerns (van de Sanden et al., Citation2019). The second solution would be for retailers to harness digital platforms to develop online sales channels or set up their own online shops. However, joining multiple digital platforms can add new barriers to customer engagement (Becker et al., Citation2023), and further strengthen global platform providers, rather than local retailers. In 2021, retailers’ sales on Amazon Marketplace represented 36% of all online sales in Germany, while Amazon’s sales represented another 18% (HDE, Citation2022).

On a more fundamental level, a “[l]oss of engagement [with consumers] is the most obvious challenge facing businesses due to the pandemic” (Mandviwalla & Flanagan, Citation2021, p. 364). Recent research has called for establishing a citizen-centric design paradigm – City 5.0 – to eliminate restrictions that currently prevent individuals from engaging with each other (Becker et al., Citation2023). According to the City 5.0 paradigm, inclusive digital solutions could engage service providers and service consumers by establishing a market perspective to foster liveability for all actors in a city (Becker et al., Citation2023).

Inspired by the City 5.0 paradigm, this paper posits that a new type of digital platform could foster actor engagement on the collective level of the high street. Actor engagement refers to the disposition of actors to invest resources, beyond what is required for the transactional exchange of resources, to co-create value (Brodie et al., Citation2019). This resource exchange takes place in service ecosystems that are “relatively self-contained, self-adjusting systems of mostly loosely coupled social and economic (resource-integrating) actors connected by shared institutional logics and mutual value” (Lusch & Nambisan, Citation2015, p. 161). However, to successfully engage high street actors collectively requires moving beyond dyadic buyer-seller transactions – those connecting single stores to their visitors – to establishing many-to-many relationships. Engagement platforms (EPs), i.e., “digital applications […] that extend the reach and speed of interactions with multiple and diverse actors” (Frow et al., Citation2015, p. 472), could hold the potential for achieving precisely that.

Besides empirically analysing actors’ roles and engagement practices, an IS view enables investigating and unveiling the prospects and constraints of designing EPs. EPs aim to attract consumersFootnote1 by providing “physical or virtual customer touch points where actors exchange resources and co-create value” (Breidbach et al., Citation2014, p. 592). Thus, actors engage in hybrid online-offline value co-creation processes (Breidbach et al., Citation2014), integrating their resources for mutual benefit (Vargo et al., Citation2008). On high streets, actors can use EPs to access digital touch points that complement their physical interactions with other actors, combining the digital and the physical realms (Breidbach et al., Citation2014), whereby “engagement goes beyond seeing [the] physical space as a platform for completing a sale” (Mandviwalla & Flanagan, Citation2021, p. 364). This study aims to design and evaluate a digital actor engagement platform for local high streets that augments the primarily physical ecosystems with digital touch points, thereby fostering actor engagement on a collective level.

In an 18 month-long action design research (ADR) project (Sein et al., Citation2011), we designed, implemented, evaluated, and improved smartmarket2, the first instantiation of a digital actor engagement platform designed for a local high street. We conducted three iterations of the ADR cycle, culminating in an open field study that involved over 2,300 consumers and 150 complementors (retailers, restaurants and other service providers). Building on the actor engagement concept, smartmarket2 connects local complementors with high street visitors, enabling both groups of actors to propose, maintain, exchange, and integrate digital resources, resulting in hybrid online-offline customer journeys.

Our main contribution comprises four design principles (Gregor et al., Citation2020) as prescriptive knowledge on digital actor engagement platforms, which encapsulate the core learnings of our project. We find that digital actor engagement platforms ought to (1) distinguish actor roles to enhance their engagement dispositions, (2) individualise value-in-use to facilitate engagement on a collective level, (3) strive for network effects that are strongly related to engagement connectedness and (4) support the routinising of the engagement behaviour of all actors. Our empirical data provide evidence that the EP has stimulated actor engagement on the high street under study, subject to a short-head and long-tail distribution. In line with findings from previous literature, this distribution is usually observed in online communities (Anderson, Citation2006; Enders et al., Citation2008; Jung & Pham, Citation2011). Additionally, our study extends actor engagement theory (Brodie et al., Citation2019) and questions the effects of LBA in real-world settings.

The paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we revisit research on actor engagement and digital actor engagement platforms. In Section 3, we describe the problem context and justify our ADR approach. Section 4 presents three iterations of the building, intervention and evaluation (BIE) of smartmarket2. Section 5 formalises the knowledge acquired from our ADR process by deriving four design principles. After discussing our contributions in Section 6, the paper is concluded in Section 7.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Actor engagement in service ecosystems

Service ecosystems connect actors through shared institutional logics that integrate resources to co-create value (Lusch & Nambisan, Citation2015). While actors are often only loosely coupled, the greater intensity of the connections established among actors generally fosters their engagement, increasing the value created by all participating actors (Chandler & Lusch, Citation2015). The concept of engagement was first referred to in the literature stream on customer engagement, where it was defined as a “multidimensional concept that encompasses emotional and/or behavioural aspects” (Brodie et al., Citation2013, p. 107). Thus, it does not merely include (the quantity of) interactions with a firm but the emotional bonding of an individual consumer with a firm or brand (Kumar & Pansari, Citation2016). Hence, building relationships among stakeholders in service ecosystems is fundamental to engagement since “relationship concepts are engagement antecedents and/or consequences in iterative engagement processes within the brand community” (Brodie et al., Citation2013, p. 108).

Departing from customer engagement focused on static actor roles, recent literature (e.g., M. J. Alexander et al., Citation2018; Brodie et al., Citation2019; Storbacka et al., Citation2016) established the more general concept of actor engagement. Actor engagement develops customer engagement from a dyadic to a multi-actor concept. It covers a more abstract actor-to-actor view – incorporating social and economic actors – instead of the traditional customer-firm view (Brodie et al., Citation2019). This rationale is inspired by the fundamental premise of the service-dominant logic of marketing (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016), which acknowledges that diverse actors – including “suppliers, distributors, buyers, sellers and other actors” (Chandler & Lusch, Citation2015, p. 8) – continuously integrate resources in service ecosystems (Brodie et al., Citation2019). Against the theoretical backdrop of the service-dominant logic of marketing, Brodie et al. (Citation2019, p. 183) not only define actor engagement as a “dynamic and iterative process, reflecting actors’ dispositions to invest resources in their interactions with other connected actors in a service system”, but also provide five fundamental propositions ().

Table 1. Fundamental Propositions for Actor Engagement, building on Brodie et al. (Citation2019).

2.2. Augmenting physical ecosystems with digital actor engagement platforms

Beyond actors’ willingness to engage with each other, establishing actor engagement requires EPs that facilitate interactions in relationships that are not just dyadic (Storbacka et al., Citation2016). EPs are “purpose-built, ICT-enabled environments containing artefacts, interfaces, processes and people; permitting organisations to co-create value with their customers” (Breidbach et al., Citation2014; Ramaswamy, Citation2009). The physical and virtual touch points they provide enable interactions between diverse stakeholder groups (Breidbach et al., Citation2014; Ramaswamy, Citation2009). Importantly, EPs do not manipulate interactions but enable and facilitate engagement (Storbacka et al., Citation2016).

Depending on existing business models, available resources and infrastructures, organisations might design and use different types of EPs to describe and partially prescribe interactions between a specific brand and its consumers (Blasco-Arcas et al., Citation2016). According to Frow et al. (Citation2015), there are five types of EPs: (1) digital applications (e.g., websites, mobile applications) that add digital touch points to a servicescape, (2) software for continuous use that establishes continuing interactions, (3) physical resources for interactions with actors, (4) joint processes with multiple actors (e.g., innovation processes) and (5) specific engagement groups (e.g., call centres, social media chats).

One way of fostering actor engagement in a service ecosystem that mainly provides physical touch points is by digitalising engagement (Mandviwalla & Flanagan, Citation2021) through adopting type one EPs (Frow et al., Citation2015). This type of EP enables diverse actors to interact with each other and integrate resources via multiple online and offline channels (Brodie et al., Citation2011). Different types of digital platforms (Bartelheimer et al., Citation2022) have become omnipresent in many business-to-consumer markets (Parker et al., Citation2017; Tiwana, Citation2014), and are mostly viewed as a source of significant competitive advantage through the emerging network effects they generate (Iansiti & Lakhani, Citation2017). Depending on the number of independent groups of actors affiliated with a platform, they are either two- or multi-sided (Boudreau & Hagiu, Citation2009; Hagiu, Citation2006; Hagiu & Wright, Citation2015).

Initial design knowledge on digital platforms is available on digital, multi-sided platforms (Schreieck et al., Citation2016), which have been found to provide value in different domains (Asadullah et al., Citation2018; Hönigsberg, Citation2020; Schreieck et al., Citation2016). For example, design knowledge prescribes how to refer care assistants via online communities (Spagnoletti et al., Citation2015) or how to overcome cultural reluctance to engage in economic exchanges with strangers (Avgerou & Li, Citation2013).

3. Research approach

3.1. Problem formulation and objectives of our research

In Europe, more and more consumers shift from high street to online retail (HDE, Citation2022). In 2021, high street retail turnover in Germany decreased by 0.5%, while online retail grew by 18.9% to 86.7 billion Euro (HDE, Citation2022). Reasons for this shift are manifold and were intensified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Small- and medium-sized enterprises, which represent more than half of all businesses on (European) high streets (HDE, Citation2018) struggle with digitally transforming their business models (Bollweg et al., Citation2016, Citation2020). In a series of qualitative interviews that we performed on the high street under study (Berendes et al., Citation2020), retailers and town centre managers raised specific challenges in engaging with high street visitors (). While most interviewees were concerned about interactions with individual visitors (or the lack thereof), we recognised that a more fundamental problem on the high street was a lack of engagement on the collective level of the high street.

Table 2. Objectives of our Design Process, Pointing to Challenges in High Streets and the Fundamental Propositions for Actor Engagement (Brodie et al., Citation2019.).

Drawing on the fundamental propositions for actor engagement (Brodie et al., Citation2019) as our kernel theory, we aim to design the first digital actor engagement platform for the collective level of a high street, enabling actors to engage with each other for mutual benefit (). The platform is intended to supplement the local high street service ecosystem by establishing digital (online) interactions alongside traditional physical (offline) interactions. On our platform, we define all high street visitors as consumers and all other actors as complementors.

3.2. ADR approach and research context

ADR represents a “research method for DR [design research] that draws on action research” (Sein et al., Citation2011, p. 38). ADR projects encompass iterative cycles to overcome the bias of sequential design processes, consisting of four distinct phases (Sein et al., Citation2011): First, in the problem formulation phase, the problem space – i.e., the central element of the context (C. Alexander, Citation1964; Maedche et al., Citation2019) – is identified as a specification of a class of problems. Second, in the iterative building, intervention and evaluation phase (BIE), an IT artefact that meets the stipulated demands is developed and implemented with the help of organisational interventions before it is finally evaluated in its context. Third, in the reflection and learning phase, the abstraction of the knowledge gained during the design process is applied to the class of problems. This third phase is continuous and parallels the first two phases of the ADR cycle, as the artefact and its socio-technical context differ in each iteration. Fourth, the knowledge derived in the third phase is generalised in the formalisation of learning phase, e.g., in the form of design principles (Gregor et al., Citation2020).

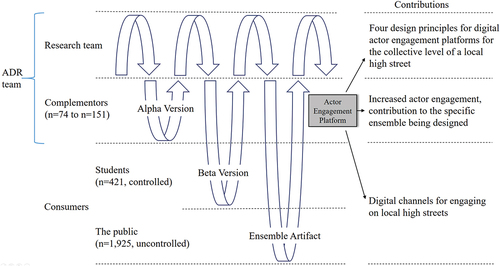

We conducted three major iterations of the ADR cycle, each comprising phases of building, intervention and evaluation in addition to reflection and learning (Sein et al., Citation2011). Our independent and publicly funded team of researchers approached the complementors in the high street of Paderborn. By cooperating with the local town centre management and a local business association, we were able to use their networks to recruit complementors for our research. However, neither the town centre management nor the local business association were affiliated with the platform during the three BIE phases. Each BIE iteration helped to improve the form and function of the digital platform, to sharpen the problem formulation and to continuously adapt the context with a view to including a broad group of actors. summarises the three iterations in terms of our artefact, smartmarket2, the participants involved and the contributions that address the distinct groups of involved actors. While we report major platform modifications, we black box the plethora of micro-changes made during each iteration (e.g., bug fixes). The three iterations were planned in line with the evaluation strategy of human risk and effectiveness (Venable et al., Citation2016), which had proven its usefulness in similar research projects (e.g., Giessmann & Legner, Citation2016; Hyvärinen et al., Citation2017). This strategy prescribes evaluating an IT artefact’s basic functionality in an artificial and formative way before evaluating the ensemble artefact in its real-world context (Venable et al., Citation2016). We chose this strategy to cope with the inherent design risk – the platform had to benefit all actors in a high street ecosystem to foster actor engagement – and to establish the IT artefact in the long term (Venable et al., Citation2016). After three BIE phases, we were able to develop four design principles resulting from our design process (Gregor et al., Citation2020) during ADR’s ultimate phase – the formalisation of learning (Sein et al., Citation2011).

4. Designing smartmarket2 as a digital actor engagement platform for local high streets

4.1. First ADR iteration: Alpha version

4.1.1. Building, intervention and evaluation

In the first iteration, we built our digital platform as an alpha version with skeleton features (cf. Appendix A). To ensure the artefact suits the needs and capabilities of complementors on high streets, we conducted interviews and workshops with town centre managers and selected retailers to obtain requirements, assess technology readiness and develop a project plan. We also identified personas and created user stories. The platform’s alpha version consisted of a web app for complementors that provided general functionality and a mobile application frontend for the consumer side.

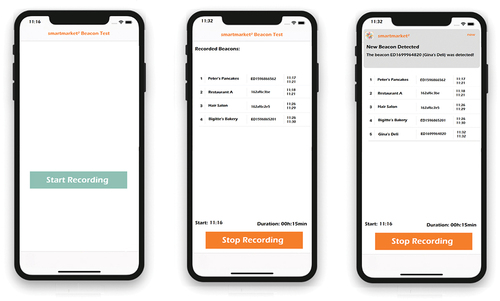

The main goal of the first BIE iteration was to ensure the technical feasibility of the platform. Hence, we added complementor profiles, locations and campaigns to the platform and hired 25 students as test consumers to check whether the artefact’s form and function met the identified technical requirements and whether it was technically feasible. While Bluetooth low-energy (BLE) beacons were applied in other contexts (e.g., inside and outside of retail stores, cf. Molitor et al., Citation2018), they had never before been used on a collective high street level to enable LBA. Hence, we simulated a high street at our university’s campus, choosing a building complex that is approximately 15 metres wide and surrounded by walls and windows. We simultaneously evaluated both leading protocols for BLE Beacons: Google’s EddystoneFootnote2 and Apple’s iBeaconFootnote3 standards. Subsequently, we equipped test consumers with smartphones that used different versions of Android and iOS operating systems. They installed the alpha version of smartmarket2 (cf. Appendix A) and entered our artificial high street, consisting of eight complementors broadcasting one campaign each via a BLE beacon. Each participant walked between three and eight times past the complementors.

4.1.2. Reflection and learning

In this artificial and formative setting, no significant technical problems were identified with smartmarket2’s core functions or with the use of BLE beacons to trigger push notifications. BLE beacons provided a sufficient means for establishing LBA in a high street via broadcasting signals to smartphones nearby, up to a maximum range of 30 metres. 86% of the campaigns were delivered correctly with the iBeacon standard, while 79% of the campaigns were correctly delivered based on the Eddystone standard. Therefore, we decided to use the iBeacon standard in our subsequent research.

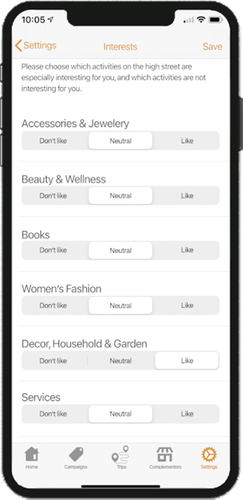

The first ADR iteration resulted in three major learnings. First, it became apparent that complementors also need a mobile application frontend. This finding is strongly related to the second learning, which indicated that digital resources on the complementor side are rare (e.g., pictures of products and location) and need to be created for the platform. While complementors can easily use their smartphones to create such resources, they were forced to then switch to a PC/notebook or use the web app via smartphone to add the resources to the platform. This is uncomfortable and may result in complementors’ decision not to integrate the resources. The third learning was derived from feedback from consumers who tested the application, with the finding that they prefer to receive only relevant campaigns (e.g., based on personal interests).

4.2. Second ADR iteration: Beta version

4.2.1. Building, intervention and evaluation

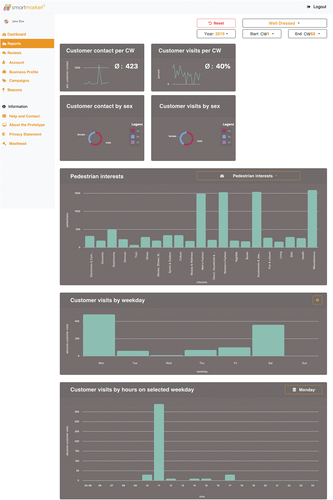

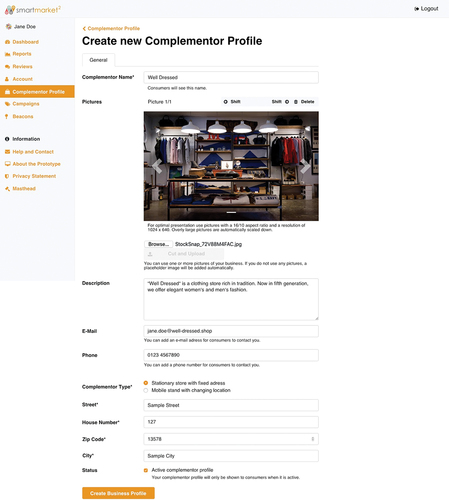

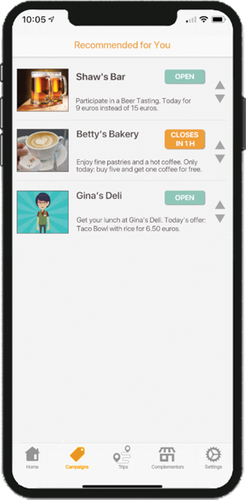

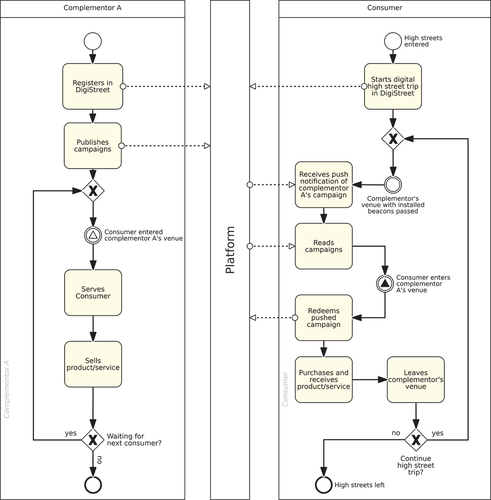

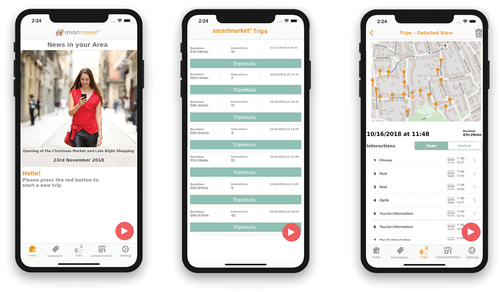

Based on the learnings from the first iteration, we enhanced platform functionality (cf. Appendix B) for complementors by developing a mobile application for smartmarket2 . Additionally, we implemented reports and visualised them in a dashboard, enabling complementors to assess consumer behaviour (Figure B1). Based on the observations made in the first iteration, we optimised the platform for the iBeacon standard on the consumer side. This included adding a feature that enables consumers to define their shopping interests and complementors to assign interest categories to their profiles and campaigns. A background service matches consumers’ interests with the campaign categories specified by the complementors to only present relevant campaigns and stores to consumers.

We conducted an eight-week field experiment in Paderborn, a German city with a population of approximately 150,000 to identify to what extent LBA mechanisms for campaign delivery can increase the number of interactions between complementors and consumers in a high street (i.e., actor engagement). Additionally, we strived to observe whether LBA impacts consumer behaviour in terms of high street trip length and number of complementors passed. This iteration comprised several interventions aimed at encouraging and supporting complementors to adopt our digital actor engagement platform, and observing the resulting changes in their practices. To promote smartmarket2, we co-hosted six workshops with the local town centre management and business associations. Additionally, we conducted more than 50 bilateral meetings with complementors on specific issues, i.e., training them on how to use the platform’s functionality, increasing awareness of digital channels, advising (and giving hands-on support to) complementors on how to issue campaigns on the platform, and providing IT support and troubleshooting. We involved a total of 74 high street complementors in using smartmarket2. Of these, 58 complementors – comprising 28 retailers, ten service organisations and 20 bars/restaurants – were equipped with BLE beacons and added their master data to smartmarket2. The other 16 were stall operators who joined the experiment during the annual Christmas market (December 2018). We encouraged the participating complementors to publish at least one campaign per week. Forty-five complementors published one or more campaigns in the experiment, totalling 96 campaigns. We decided not to exclude complementors who did not launch any campaigns, since involving more complementors is crucial to fostering network effects (Eisenmann et al., Citation2006; Hagiu & Wright, Citation2015).

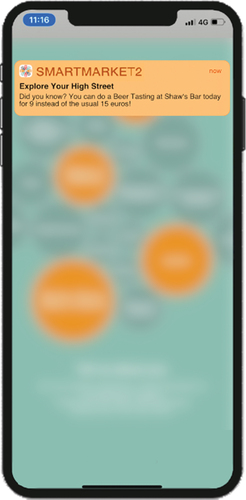

On the consumer side, we equipped a group of 421 students randomly with one of four different versions of our mobile application (Tables B11 and B12). To specifically discuss the impact of LBA on interactions, we need to look at the differences between two of these groupsFootnote4. For our treatment, we decided to send automatic push notifications on campaigns. For the control group, the app contained full functionality but with all LBA mechanisms disabled, such that participants could receive campaigns via pull requests only. The campaigns delivered via pull were presented in a list that could be sorted alphabetically in ascending or descending order, to prevent the order of campaigns from biasing the results (Molitor et al., Citation2020). By contrast, participants in the treatment group could use the app’s full functionality, including push notifications (). Members of both groups were asked to start a digital high street trip when entering the high street to track their trajectoriesFootnote5 via BLE beacons. While the control group did not receive any push notifications, starting a trip was still essential to the tracking of consumer trajectories. At the end of the field experiment, we ran a survey among participating consumers to collect feedback on the attractivity of complementors (e.g., profile and campaign design) and on the overall consumer experience of engaging with complementors via smartmarket2.

Table 3. Overview of Selected Experimental Groups.

During our eight-week experiment, consumers across the two groups generated 23,769 data entries that document the delivered campaigns, the delivery mechanism (pull, push), a timestamp and a binary variable “viewed after delivery”. Consumers in the control group pulled 10,547 campaigns, while participants in the treatment group pulled 12,065 campaigns. Participants in the treatment group received an additional 1,157 campaigns via LBA push notifications ().

Table 4. Campaign Delivery for Participants in the Experimental Group.

Additionally, we performed a regression analysis to analyse if LBA impacted the share of campaigns viewed after delivery. This analysis revealed a highly significant difference (p < .001) between the two groups in the share of viewed campaigns, both for pull delivery and for LBA, with a regression coefficient of .038 (pull delivery between groups) and .089 (pull delivery – control group – and LBA, cf. Table B13). A robustness check (cf. Table B14) revealed that the positive effect on actor engagement was even higher when LBA was provided as the only mechanism by which consumers were informed about the campaigns. The share of campaign views was significantly higher in the treatment than in the control group.

Apart from actor engagement, we further assumed that offering digital campaigns in a high street ecosystem impacts consumer behaviour (e.g., Ghose et al., Citation2019; Klumpe et al., Citation2020). Concerning the groups in our experiment, we looked for effects on both the length of high street trips and the number of complementors (). The consumers in our experiment recorded 672 digital high street trips that included at least one complementor (a signal from a beacon installed at a complementor’s venue detected by a consumer’s smartphone). A total of 158 of the 239 participants performed and recorded at least one digital high street trip. A t-test on trip length (p = 0.785) and the number of complementors passed (p = 0.061) did not reveal any significant differences between the two groups. Thus, our experiment provided no evidence of LBA impacting the length of a high street trip or the number of complementors passed.

Table 5. Analysis of consumer behaviour.

4.2.2. Reflection and learning

From interpreting the evaluation results of the second iteration, we obtained major learnings on both the complementor and the consumer sides. Concerning complementors, (1) profiles were most attractive if all information was available and if they were visually appealing (e.g., by providing multiple pictures of a store’s exterior and interior), (2) the more active a complementor was on the platform, the more attractive the store was to consumers, (3) the most viewed campaigns were those that gave discounts and were short-dated and (4) the installed BLE beacons did not cover the high street to sufficiently enable the tracking of consumer paths. On the consumer side, we identified that (1) both push and pull mechanisms for campaign delivery positively impacted campaign views, but (2) the number of delivered campaigns was not (significantly) dependent on the type of notification. Furthermore, (3) additional digital resources did not impact the high street trip length and the number of visited complementors and (4) the vast majority of consumers did not want to reveal personal data (name, address etc.) or location data by starting a high street trip in the app.

4.3. Third ADR iteration: Ensemble artefact

4.3.1. Building, intervention and evaluation

Informed by the results of the second iteration and their interpretation, we implemented functionality that enabled complementors to add additional digital resources (i.e., multiple pictures) to their profiles and campaigns. Furthermore, we concluded that a combination of LBA push notifications and pull requests is most likely to facilitate interactions and thus foster actor engagement over the long term. Hence, we enabled both campaign delivery mechanisms in the consumer mobile application. Because consumers hesitated to add personal data and share location data while visiting the high street, we implemented two additional features. First, we included privacy management options allowing consumers to self-govern personal data handling. Second, we added a geofence functionality that reminded consumers to start and record a high street trip via push notification once they entered the high street. To eliminate restrictions and ensure inclusion, we added an onboarding process to support first-time users.

For interventions in this iteration, we presented the results of the field experiment in the second iteration to all participating complementors. We explained which profiles and types of campaigns were most successful and provided them with guidelines on how to create appealing profiles and publish attractive campaigns. Additionally, we held more than 25 bilateral meetings to maintain the profiles of complementors who freshly joined the platform, and supported them in creating their first campaigns. We also installed BLE beacons at the locations of the new complementors and added approximately 50 additional BLE beacons in the public space (e.g., onto lamp posts) to cover the high street. Finally, we encouraged the town centre management to actively market smartmarket2 and to support complementors throughout the study.

We conducted a field study to evaluate the artefact. First we launched smartmarket2 in a press conference co-hosted with the town centre management, to announce that the mobile application is available in the Android and iOS app stores and to invite the general public to use it. We also advertised the platform in the local media (newspapers, TV shows and radio stations). During the six-month field study from July to December 2019, a total of 1,925 consumers registered on smartmarket2, while 87 complementors published a profile. The complementors comprised 47 retailers, 19 bars and restaurants, 15 service organisations, five municipal institutions, and one ecclesiastical institution. During special events, such as the city’s annual fair and the Christmas market, 64 additional stall operators joined smartmarket2. In total, 243 campaigns were published on our digital platform (of which 165 were issued by operators other than stallholders).

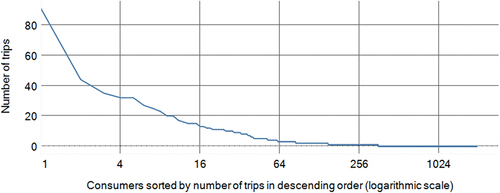

Compared to the number of digital high street trips (672) recorded during the field experiment in the second BIE phase, the number of trips (1,127) recorded in the field study was much lower in relation to the number of participants. On average, one consumer performed 0.59 digital high street trips (compared to 2.81 average trips in the field experiment). Further analysis revealed that ten percent of participants recorded 86.5% of the digital high street trips (cf. ).

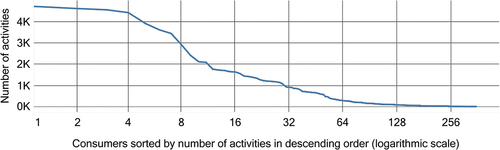

For consumers who enabled data loggingFootnote6 in their profile, we identified a highly significant (p < .001) correlation of 0.594 (spearman correlation) between their activity on the app and their number of high street trips. Thus, the more a consumer used the app, the more digital high street trips were generated. However, the low number of high street trips recorded indicates that many consumers used the app as a (passive) source of information without actually performing any trips. Analysing the activity of different consumers () revealed a similar pattern. While consumers who gave their consent to log their data used the app on 4.1% of the total field study days, on average (median: 1.4%), the top ten percent of consumers who used the app most frequently did so on 23.5% of all field study days (median: 16.4%).

As can be seen, the data revealed a long tail phenomenon (Anderson, Citation2006): A short head of consumers on smartmarket2 behaved differently in contrast to the majority of consumers (the long tail). This finding is in line with research on other online communities, in which “a 90:9:1-distribution can be observed, meaning that 90% of participants are mostly passive, 9% show mediocre engagement and 1% show top participation (McConnell & Huba, Citation2007)” (Troll et al., Citation2017, p. 5). Unsurprisingly, a higher consumer activity was associated with a significantly higher number of digital high street trips and delivered campaigns (both push- and pull-based). Our data shows that the most active consumers were heterogeneous regarding age, gender and interests.

An analysis of the complementors’ usage behaviour revealed a similar long tail pattern. On the 165 days on which the complementors had access to smartmarket2, they logged in on 6.24 days, on average, with a median of 4 days. Nine of 87 complementors (10%) performed almost 45% of all log-ins. Furthermore, 10% of all complementors created more than 55% of all campaigns.

A closer inspection of the top ten percent of complementors reveals that this group is heterogeneous, too. Nearly all of these complementors used social media channels before and are, thus, used to dealing with digital content and channels. The only characteristic that distinguished them from long-tail complementors was that they had in-house communication and marketing departments that gave them superior capabilities to exchange and integrate their digital resources. Short-head complementors, therefore, were not SMEs or one-man-operated businesses typical of most European high streets.

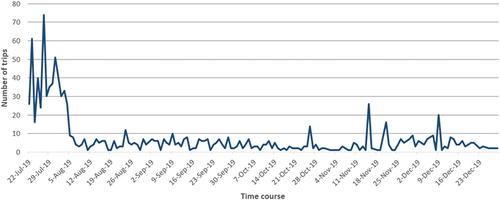

The majority of consumer activity in the app and the number of digital high street trips were recorded at the beginning of our field study (), which may have reflected the fact that our interventions to promote the app were focused on this phase, aimed at establishing network effects. The launch of our field study coincided with the start of an annual funfair, which resulted in additional stall operators joining smartmarket2. During the funfair, the stall operators were the most active group of complementorsFootnote7 promoting campaigns on smartmarket2. After the first few weeks, we observed a decline in the platform’s usage on both the complementor and the consumer side. When another funfair (October) and the Christmas market (November and December) were held on the high street, we again observed small spikes in activity ().

4.3.2. Reflection and learning

Just like other platforms in their early stages (Evans & Schmalensee, Citation2010), smartmarket2 struggled to reach a critical mass within the study period. Only the short head of complementors who already possessed the resources and capabilities to publish attractive campaigns regularly provided value propositions that attracted consumers to engage in resource integration processes over the entire study period. Since providing user-generated content is essential for a digital platform to establish network effects and to attract other actors to join the platform, we assume that the lack of a sufficient number of attractive campaigns ultimately led to the decline in the number of active consumers (negative indirect network effects). Nevertheless, the short head of consumers who engaged with the short head of complementors regularly and over the entire study period shows that smartmarket2 provided value for them. An overview of the BIE phases and learnings is presented in Appendix C.

5. Formalization of learning: Design principles for digital actor engagement platforms in local high streets

Drawing on Gregor et al. (Citation2020), we derived design principles (DPs) as “prescriptive statements that show how to do something to achieve a goal” (Gregor et al., Citation2020, 1622). Our DPs prescribe how a digital platform ought to be designed to increase actor engagement on the collective level of a local high street. The DPs were formulated in line with (1) prior theories, (2) prior design work, (3) outcomes of design activities and/or (4) evaluation results (Purao et al., Citation2020). Further, the development of the digital platform and the DP formalisation processes were informed by actor engagement theory (Brodie et al., Citation2019; Storbacka et al., Citation2016) and design knowledge on digital platforms (Avgerou & Li, Citation2013; Schreieck et al., Citation2016; Spagnoletti et al., Citation2015). For each DP, we formulated an aim and a rationale. We also present the mechanisms and users characterising each DP (Gregor et al., Citation2020). The context for all four DPs is high street ecosystems in middle-sized European cities. A systematic overview of all four DPs is presented in Appendix D.

5.1. Design principle 1: Engagement dispositions

The likelihood of actors engaging with other actors in a service ecosystem is impacted by engagement dispositions, i.e., actors’ willingness and ability to connect and interact with other actors (Brodie et al., Citation2019). The concept of actor engagement is based on the assumption that actors in a service ecosystem can integrate resources with all other actors irrespective of their roles. In two- or multi-sided markets, however, where actors engage via digital platforms, different groups of actors need to embody different roles (Boudreau & Hagiu, Citation2009; Hagiu, Citation2006; Hagiu & Wright, Citation2015). In our ADR study, we identified complementors and consumers as two groups of actors on a local high street that required different functionalities – e.g., different types of user profiles – from the digital actor engagement platform. According to our evaluation, both groups of actors felt sufficiently inclined to use their specific functionalities – demonstrating a high level of engagement dispositions, which enables them to engage with each other. We conclude that digital actor engagement platforms must provide actor-specific functionalities to empower both complementors and consumers to fulfil their specific roles on a local high street in line with their engagement dispositions. Implementing actor-specific functionality enables complementors to build relationships with consumers that go beyond essential transactional exchange, which is hard to achieve without using a digital actor engagement platform.

5.2. Design principle 2: Engagement behaviour

Actor engagement theory states that both adding resources to and integrating current resources in a service scape via digital touch points will foster actor engagement (Breidbach et al., Citation2014; Chandler & Lusch, Citation2015; Frow et al., Citation2015; Ramaswamy, Citation2009). Hence, a digital actor engagement platform for a local high street should be designed with mechanisms that increase the desired actor engagement behaviour (Brodie et al., Citation2019). For example, we deployed BLE beacons to enable the pull and push information on events on a local high street (cf. Figure B6). Such technology-triggered interactions can support complementors in attracting consumers to visit their store and engage in further physical interactions.

Because value-in-use is idiosyncratic and determined during service consumption by the beneficiary (Grönroos & Voima, Citation2013; Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016), customised interactions enable superior value-in-use and thus increase the likelihood of positively impacting actors’ engagement behaviour. To customise value on the complementors’ side, digital actor engagement platforms ought to offer features that enable analysing and understanding the behaviour of consumers on high streets. This allows complementors to learn about the behaviour and preferences of consumers, and to continuously refine and improve their value proposition based on data-driven decision-making processes, which can help to enable network effects. Analysing consumer behaviour enables complementors to build long-term relationships, comprising multiple and recurrent online and offline interactions with the consumers on a local high street.

5.3. Design principle 3: Engagement connectedness

Actor engagement is subject to engagement connectedness, encompassing the degree to which actors are connected in a network, and their interactions shaped by the connections and the institutional context (Brodie et al., Citation2019). One way of increasing actor engagement is by extending the network with additional actors. This extension can be achieved by removing all existing platform access constraints for all actor groups, i.e., by designing a platform with a high degree of openness (Ondrus et al., Citation2015). To maximise engagement connectedness on a local high street ecosystem, a digital actor EP ought to provide functionalities that enable complementors and consumers to engage with each other on their own terms. Our evaluation showed that some consumers gave their consent to integrate personal data to receive push notifications, while others were unwilling to share their data and settled for the pull functionalities. Likewise, some consumers enabled geo-fencing functions, while others did not. Complementors, on the other hand, preferred different front ends for entering their event data (e.g., mobile app or website). This makes a clear case for digital actor engagement platforms to provide a range of functionalities that enables customised options for actors to engage with the platform, according to personal preferences. Ultimately, customising options can help to overcome the challenge of establishing network effects that depend on individual perceptions of a platform’s functionalities.

A further reason to make actor connectedness a priority is to promote network effects that are essential to establishing a critical mass of actors on each side of a platform (Evans & Schmalensee, Citation2010). Direct network effects (e.g., more complementors attract more complementors) and indirect network effects (e.g., more complementors attract more consumers, and vice versa) (Eisenmann et al., Citation2006; Gawer, Citation2014; Hagiu & Wright, Citation2015) occur in platform ecosystems if actors perceive a benefit from entering the platform (Beverungen et al., Citation2020), resulting in increased actor connectedness. To promote network effects on a local high street, it is imperative to actively communicate the benefits of joining the platform to all actor groups as early as possible, not only to overcome cold start problems but also to foster the emergence of network effects.

5.4. Design principle 4: Long-term engagement

Actor engagement theory states that actor engagement is coordinated through shared practices that determine the intensity of the connections established among actors (Chandler & Lusch, Citation2015). Hence, to foster long-term engagement, a digital actor engagement platform must prioritise complementors’ and consumers’ value-in-use over platform profitability, which is achieved by routinising actor behaviour, which in turn intensifies engagement (Brodie et al., Citation2019). To communicate the benefits of participating in our digital actor engagement platform, we performed a range of interventions with actor groups to educate them about the use of the functionalities to their advantage. The problem of communicating the EP’s value to all relevant actors can be addressed this way.

Because value-in-use is determined individually by the beneficiary (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016), platform design must allow actors to routinise their engagement behaviour, even if it remains stuck on a rather superficial level. Still, to substantiate the value co-created among all actors in the long-term, designers should strive to gradually increase actor engagement over time. This view on value co-creation contrasts with many of the current business models of platforms – including retail platforms – that concentrate value around “hub firms that capture a growing share of the overall economic value created” (Iansiti & Lakhani, Citation2017, p. 87). Since a digital engagement platform perspective rejects the possibility of a complementor controlling or owning the engagement ecosystem, platform designers must ensure that single actors cannot gain prevalence in the ecosystems and wield authority over other actors. To establish fair allocation mechanisms among complementors and consumers on a local high street, the platform owner and provider should be a local actor, and preferably not a single actor but an association of multiple complementors.

6. Discussion

6.1. Design knowledge on and contextualisation of digital actor engagement platforms

Building on instantiated IT artefacts and interventions in a natural high street ecosystem, the four presented DPs provide the first prescriptive knowledge on digital actor engagement platforms, answering recent calls for research (Reuver et al., Citation2018) and elaborating on earlier work on types of EPs (Frow et al., Citation2015). The DPs add a much-needed prescriptive dimension to the actor engagement literature that has, until now, remained limited to discussing the conceptual properties of actor engagement and EPs (Breidbach et al., Citation2014; Brodie et al., Citation2019).

The new design knowledge includes IT meta-artefacts, instantiated IT applications, and design knowledge condensed into four design principles. All three types of knowledge lend themselves to be reused by other designers. While we subjected the IT artefacts to “heavy” naturalistic evaluations in the field, we performed an additional minimum reusability evaluation to reflect the design principles’ reusability by (engagement) platform designers and high street managers who were not involved in our ADR project. We applied the criteria introduced by Iivari et al. (Citation2021), which have proved useful for testing the external validity of IT artefacts (e.g., Recker, Citation2021). The reusability evaluation is presented in Appendix E.

Our study illustrates that online and offline channels can interplay in exceptionally complex ways that are difficult to design and analyse. Part of the challenge involves the collection, integration and analysis of data from both the digital and the physical realms. We see our study as a starting point for theorising this interplay in situ, based on designing and performing interventions with a digital actor engagement platform.

Digital actor engagement platforms are similar to, but different from, other types of digital platforms. Similarities refer to the technical components of platforms and the social interaction structures proposed for digital platforms that facilitate online communities (Spagnoletti et al., Citation2015). Furthermore, we identified that the concept of engagement disposition – an actor’s readiness to integrate resources with other actors (Brodie et al., Citation2019) – is strongly related to the occurrence of network effects. Concerning indirect network effects, consumers found the digital actor engagement platform more valuable when more campaigns were launched, while complementors were more willing to publish campaigns after more consumers had signed up to the platform. Concerning direct network effects, publishing success stories of retailers using the platform attracted additional complementors. However, consumers’ interest in the platform was not intensified after more consumers had joined. We attribute this absence of direct network effects on the consumers’ side to a lack of feedback functionality in our platform, which limited their sharing by electronic word-of-mouth. More research is needed to elucidate the integration of and the relationship between actor engagement dispositions – drawing on the service literature (Brodie et al., Citation2019) – and network effects (Gawer, Citation2014) on (digital) platforms.

Differences from other platforms appertain to the properties of EPs that foster the value-in-use experienced by different groups of actors, increasing their dispositions to invest resources beyond essential transactions. Even if digital platforms can be a source of significant competitive advantage through network effects (Iansiti & Lakhani, Citation2017), they can only provide value propositions aimed at attracting actors to engage in resource integration processes (Hein et al., Citation2020). While complementors and consumers engaged with each other using our digital actor engagement platform, the platform did not always provide enough value-in-use to secure their long-term engagement.

Because actor engagement platforms enable both digital and physical interactions, actors can decide which channel they prefer, which entails an inherent contradiction. On the one hand, actors hold different attitudes towards EPs because engagement has an emotional dimension and refers to psychological states that differ among the actors (Brodie et al., Citation2011; Troll et al., Citation2017). Hence, the degree of engagement among actors achieved with a digital EP is subject to individual assessments made by beneficiaries (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2016). On the other hand, EPs must be able to match diverse actors and actor groups in a service ecosystem (Bonina et al., Citation2021), as engagement connectedness is vital for platform success (Brodie et al., Citation2019). Our results provide evidence that customising the functionality provided by the platform can help to reconcile this contradiction. For instance, allowing consumers to switch off data-intensive functionalities enabled us to uphold the engagement of consumers unwilling to enable push mechanisms due to data privacy concerns.

Consequently, EPs need to empower users to determine which functionalities provide value-in-use for them, and offer low-entry opportunities for engaging with others. Once network effects are realised and engagement connectedness increases, platform managers should gradually strive to increase the intensity of actors’ engagement, nudging them to unlock more advanced functionalities and routinise engagement-intensive behaviour. Still, actors unwilling to engage with others on digital channels could limit their use to basic functionalities and focus their engagement on physical channels. Both types of engagement are welcome to co-create value on a collective level in a hybrid service ecosystem, such as a high street.

6.2. Extending actor engagement and engagement ecosystems theory

Our study answers a recent call to perform longitudinal studies to better understand actors’ interactions and relationships in an engagement ecosystem (Brodie et al., Citation2019). We obtained three insights in this regard that enhance our knowledge of actor engagement theory and previous conceptualisations of EPs.

First, we find that if we strive to analyse or foster actor engagement in any particular service ecosystem – such as in a high street – one of the first steps has to be the identification of different groups of actors and their different views of engaging in value co-creation (cf. DP 1). This view contradicts actor engagement theory, which proposes abstract principles and mechanisms of value co-creation, arguing that all actors are “fundamentally engaged in similar ways” (Storbacka et al., Citation2016, p. 3009). While this viewpoint seems plausible on a conceptual level of service ecosystems and value co-creation, we argue that in any particular context, designers should distinguish the roles of the actors that are likely to use the interfaces, functions, data objects or affordances enabled by an actor engagement platform. This view is also in line with state-of-the-art software engineering principles, emphasising the need to identify personas for whose requirements different software properties are designed (Cooper, Citation2003). Our findings outline that we need to distinguish the abstract level of service (eco-)systems – at which general mechanisms of actor engagement can be identified to theorise about value co-creation – from the concrete context in which we seek to increase actor engagement. To reconcile both views, future research needs to determine how the conceptual level and the concrete contexts of actor engagement interrelate and complement each other.

Second, our results provide evidence for the crucial role played by information technology in the dynamic process of actor engagement. Extant research has argued that “actor engagement emerges through a dynamic, iterative process, where its antecedents and consequences affect actors’ dispositions and network connections” (Brodie et al., Citation2019, p. 181). All actors in a service ecosystem contribute to fostering (dis-)engagement on a system’s level by continuously integrating resources via multiple channels (Brodie et al., Citation2019). Still, the literature has remained silent on the role of information technology and the ongoing digital transformation of SMEs in this process (Mandviwalla & Flanagan, Citation2021). We were able to confirm previous research (Molitor et al., Citation2018; Unni & Harmon, Citation2007) that identified LBA to positively impact the number of interactions between actor groups. Thus, future research needs to unpack the impact of the generative mechanisms of EPs as IT artefacts on the engagement behaviour of different actor groups.

Third, our results illustrate that adding additional digital touch points to a physical service scape can facilitate interactions on a high street, demonstrating that digital innovation opens up new pathways for action (Mendling et al., Citation2020). However, the increase in actor engagement might remain limited to a short head of actors. As is common in online communities and other platforms (Enders et al., Citation2008; Jung & Pham, Citation2011), most actors’ engagement will remain faint. This uneven distribution highlights the importance of considering individual engagement dispositions more fully to understand why engagement intensity often remains low, even when engagement connectedness is high. We call on future research to conceptualise different degrees of engagement intensity on an EP along with new strategies, functionalities and interventions that gradually help platform managers to foster actors’ engagement intensity.

6.3. Field evidence on the effectiveness of location-based advertising

From an empirical point of view, our study provides much-needed field evidence on the effectiveness of LBA because extant research has primarily investigated LBA in controlled settings, like experiments (e.g., Fang et al., Citation2015; Ghose et al., Citation2019; Molitor et al., Citation2018, Citation2020) or secondary data analyses (e.g., Molitor et al., Citation2016). In contrast with applications of LBA in shopping malls (Ghose et al., Citation2019), which are ecosystems managed by one central actor (i.e., the owner of the mall), high streets are public spaces that feature diverse types of complementors that independently decide if and how they engage with others. Since the effectiveness of LBA in our setting was lower than in most of the available studies, we conclude that experimental research might substantially overestimate the potential market penetration and success of LBA. It appears to us that most studies quantifying the impact of mobile advertising technologies focus on the short head of complementors and consumers (e.g., Fang et al., Citation2015; Ghose et al., Citation2019; Molitor et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). However, our study results strongly suggest that the higher LBA effectiveness discovered for these groups is not generalisable to a population level (cf. third BIE phase).

A significant motive for consumers being reluctant to engage is their concern for data protection. Our empirical findings complement related observations from qualitative interview studies that highlighted the crucial role of consumers’ concerns over data protection in the context of in-store beacon scenarios (van de Sanden et al., Citation2019). Our results suggest the importance of conducting further empirical research on the effectiveness of LBA in naturalistic settings to triangulate findings from controlled environments and secondary data analyses. We see our study as a first step towards quantifying the efficacy of LBA on a population level and determining if this effect is strong enough to generate a critical mass of actors to join an EP.

6.4. Limitations

Developing design knowledge on digital platforms is particularly tricky since platforms rely on the actions of actors that lie outside of a platform owner’s control (van Alstyne et al., Citation2016). In addition, their actions may not correspond directly to the form and function of platforms as IT artefacts. Thus, design knowledge cannot prescribe if and how stakeholders will use the platform to exchange and integrate resources, apart from the possibility that actors can also appropriate a platform (un-)faithfully (DeSanctis & Poole, Citation1994). We neither found rival DPs for digital actor engagement platforms nor any similar IT artefacts that were instantiated and used publicly on other local high streets. Thus, while we acknowledge the general limitations of design knowledge regarding platforms, our DPs can serve as a starting point to further investigate the impact of digital platforms on actor engagement in a high street ecosystem.

We piloted and evaluated smartmarket2 in Paderborn, a medium-sized German city. Although this city is representative in size and structure for many European cities, instantiating and evaluating smartmarket2 in other cities may have led to different results. We expect cultural differences to govern the role of data protection concerns that impact the effectiveness of LBA since German citizens are notoriously reluctant to give others access to their data (Horstmann et al., Citation2021). Further, local business associations and the town centre management helped us to promote smartmarket2 to both complementors and consumers. Other researchers implementing a digital actor engagement platform in a high street should also benefit from partnering with local organisations to foster early participation in the platform.

7. Conclusion

Our study introduces four DPs as prescriptive knowledge on digital actor engagement platforms for local high streets that can be employed to increase actor engagement on the collective level. These DPs consolidate insights from implementing and evaluating smartmarket2 – the first instantiation of a digital actor engagement platform – in a longitudinal ADR study. Beyond the proposed DPs, our study contributes to conceptual actor engagement theory and triangulates related work on LBA effectiveness with field evidence from a naturalistic setting. Implementing digital actor engagement platforms is one step towards achieving a restriction-free and citizen-centric City 5.0 (Becker et al., Citation2023). Managers can build on our results to review existing digital platforms with a view to increasing actor engagement. At the same time, they can instantiate our DPs to implement their own digital actor engagement platforms to facilitate actor engagement in a high street. Complementors might make use of our results to explore new ways of engaging with other actors in a high street, building on digital engagement platforms.

Acknowledgements

Designing and evaluating our digital actor engagement platform would not have been possible without the profound engagement of various actors in Paderborn, especially the local city administration, the local town centre management and the retailers and citizens participating in our field study. We also gratefully acknowledge the valuable and constructive feedback from Tuure Tuunanen and the team of editors and reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We refer to the actor groups on digital platform ecosystems as complementors and consumers, in line with Hein et al. (Citation2020), instead of using related concepts (e.g., user and customer), while retaining those that are firmly established in the literature, e.g., customer experience.

2. For more information visit: https://github.com/google/eddystone.

3. For more information visit: https://developer.apple.com/ibeacon/.

4. The baseline group (cf. Table B12) remained unconsidered, as its participants could not receive any campaigns. We used the push group for a later robustness check (cf. Table B14).

5. BLE Beacons were used primarily to send push notifications on campaigns to consumers’ smartphones. However, we added a back-end feature to smartmarket2 that generates a database entry for each BLE beacon detected. An entry comprises the beacon ID, time, date and consumer ID – even if a complementor did not connect a campaign to a particular BLE beacon. This enabled us to track and analyse consumer trajectories in a high street by analysing their digital high street trips, even if no push notifications were sent to members of the control group.

6. We collected data on the consumer’s usage of the app to detect any malfunctions and to analyse their usage behaviour. To comply with GDPR, we asked the consumer for their consent for their data to be logged. Hence, data were received only from those participants who gave consent and enabled logging. The analysis of consumer activity was based on log entries that are generated when a consumer uses the app (e.g., by clicking a link or button).

7. Because they only joined for a limited period of time, they are not among the complementors in the short head, considering the entire period. Still, this fact indicates that the platform enables all types of complementors to interact on our digital actor engagement platforms.

References

- Alexander, C. (1964). Notes on the synthesis of form. Harvard University Press.

- Alexander, M. J., Jaakkola, E., & Hollebeek, L. D. (2018). Zooming out: Actor engagement beyond the dyadic. Journal of Service Management, 29(3), 333–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-08-2016-0237

- Anderson, C. (2006). The long tail: Why the future of business is selling less of more. Hyperion.

- Asadullah, A., Faik, I., & Kankanhalli, A. (2018). Digital platforms: A review and future directions. PACIS 2018 Proceedings, Yokohama, Japan.

- Avgerou, C., & Li, B. (2013). Relational and institutional embeddedness of Web-enabled entrepreneurial networks: Case studies of netrepreneurs in China. Information Systems Journal, 23(4), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12012

- Bartelheimer, C., zur Heiden, P., Lüttenberg, H., & Beverungen, D. (2022). Systematizing the lexicon of platforms in information systems: A data-driven study. Electronic Markets, 32(1), 375–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-022-00530-6

- Becker, J., Chasin, F., Rosemann, M., Beverungen, D., Priefer, J., Vom Brocke, J., Matzner, M., Del Rio Ortega, A., Resinas, M., Santoro, F., Song, M., Park, K., & DiCiccio, C. (2023). City 5.0: Citizen involvement in the design of future cities. Electronic Markets, 33(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-023-00621-y

- Bellavista, P., Küpper, A., & Helal, S. (2008). Location-based services: Back to the future. IEEE Pervasive Computing, 7(2), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1109/mprv.2008.34

- Benlian, A., Hilkert, D., & Hess, T. (2015). How open is this platform? The meaning and measurement of platform openness from the complementers’ perspective. Journal of Information Technology, 30(3), 209–228. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.6

- Berendes, C. I., zur Heiden, P., Niemann, M., Hoffmeister, B., & Becker, J. (2020). Usage of local online platforms in retail: Insights from retailers’ expectations. European Conference on Information Systems, Marrakech, Morocco.

- Beverungen, D., Kundisch, D., & Wünderlich, N. (2020). Transforming into a platform provider: Strategic options for industrial smart service providers. Journal of Service Management, 32(4), 507–532. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-03-2020-0066

- Blasco-Arcas, L., Hernandez-Ortega, B. I., & Jimenez-Martinez, J. (2016). Engagement platforms. Journal of Service Theory & Practice, 26(5), 559–589. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-12-2014-0286

- Bollweg, L., Lackes, R., Siepermann, M., Sutaj, A., & Weber, P. (2016). Digitalization of local owner operated retail outlets: The role of the perception of competition and customer expectations. PACIS 2016 Proceedings, Chiayi, Taiwan.

- Bollweg, L., Lackes, R., Siepermann, M., & Weber, P. (2020). Drivers and barriers of the digitalization of local owner operated retail outlets. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(2), 173–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2019.1616256

- Bonina, C., Koskinen, K., Eaton, B., & Gawer, A. (2021). Digital platforms for development: Foundations and research agenda. Information Systems Journal, 31(6), 869–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12326

- Boudreau, K. J., & Hagiu, A. (2009). Platform rules: Multi-sided platforms as regulators. Platforms, Markets and Innovation, 1, 163–191. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1269966

- Breidbach, C. F., Brodie, R., Hollebeek, L., Gummesson, E., Mele, C., & Polese, F. (2014). Beyond virtuality: From engagement platforms to engagement ecosystems. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 24(6), 592–611. https://doi.org/10.1108/MSQ-08-2013-0158

- Brodie, R. J., Fehrer, J. A., Jaakkola, E., & Conduit, J. (2019). Actor engagement in networks: Defining the conceptual domain. Journal of Service Research, 22(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670519827385

- Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511411703

- Brodie, R. J., Ilic, A., Juric, B., & Hollebeek, L. (2013). Consumer engagement in a virtual brand community: An exploratory analysis. Journal of Business Research, 66(1), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.07.029

- Chandler, J. D., & Lusch, R. F. (2015). Service systems: A broadened framework and research agenda on value propositions, engagement, and service experience. Journal of Service Research, 18(1), 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670514537709

- Cooper, A. (2003). The inmates are running the asylum. SAMS.

- DeSanctis, G., & Poole, M. S. (1994). Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive structuration theory. Organization Science, 5(2), 121–147. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.2.121

- Eisenmann, T., Parker, G., & van Alstyne, M. W. (2006). Strategies for two-sided markets. Harvard Business Review, 84(10), 92.

- Enders, A., Hungenberg, H., Denker, H. P., & Mauch, S. (2008). The long tail of social networking. European Management Journal, 26(3), 199–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2008.02.002

- Evans, D. S., & Schmalensee, R. (2010). Failure to launch: Critical mass in platform businesses. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1353502

- Fang, Z., Gu, B., Luo, X., & Xu, Y. (2015). Contemporaneous and delayed sales impact of location-based mobile promotions. Information Systems Research, 26(3), 552–564. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2015.0586

- Frow, P., Nenonen, S., Payne, A., & Storbacka, K. (2015). Managing co-creation design: A strategic approach to innovation. British Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12087

- Gawer, A. (2014). Bridging differing perspectives on technological platforms: Toward an integrative framework. Research Policy, 43(7), 1239–1249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.03.006

- Ghose, A., Li, B., [BEIBEI], & Liu, S. (2019). Mobile targeting using customer trajectory patterns. Management Science, 65(11), 5027–5049. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3188

- Giessmann, A., & Legner, C. (2016). Designing business models for cloud platforms. Information Systems Journal, 26(5), 551–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12107

- Gregor, S., Chandra Kruse, L., & Seidel, S. (2020). Research perspectives: The anatomy of a design principle. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 21(6), 1622–1652. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00649

- Grewal, D., Noble, S. M., Roggeveen, A. L., & Nordfalt, J. (2020). The future of in-store technology. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00697-z

- Grönroos, C., & Voima, P. (2013). Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 41(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-012-0308-3

- Hagiu, A. (2006). Pricing and commitment by two-sided platforms. The RAND Journal of Economics, 37(3), 720–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2171.2006.tb00039.x

- Hagiu, A., & Wright, J. (2015). Multi-sided platforms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 43(1), 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2015.03.003

- Hart, C., Stachow, G., & Cadogan, J. W. (2013). Conceptualising town centre image and the customer experience. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(15–16), 1753–1781. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.800900

- HDE. (2018). Frühjahrspressekonferenz des Handelsverband Deutschland (HDE). https://einzelhandel.de/images/presse/Pressekonferenz/2018/PK_Charts.pdf

- HDE. (2020). Zahlenspiegel 2020 des Handelsverband Deutschland (HDE). https://einzelhandel.de/index.php?option=com_attachments&task=download&id=10613

- HDE. (2022). Online Monitor 2022 des Handelsverband Deutschland (HDE). https://einzelhandel.de/index.php?option=com_attachments&task=download&id=10659

- Hein, A., Schreieck, M., Riasanow, T., Setzke, D. S., Wiesche, M., Böhm, M., & Krcmar, H. (2020). Digital platform ecosystems.Electronic Markets. 30(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00377-4

- Hein, A., Schreieck, M., Riasanow, T., Setzke, D. S., Wiesche, M., Böhm, M., & Krcmar, H. (2020). Digital platform ecosystems. Electronic Markets, 30(1), 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00377-4

- Hönigsberg, S. (2020). A platform for value co-creation in SME networks. In S. Hofmann, O. Müller, & M. Rossi (Eds.), Lecture notes in computer science. Designing for digital transformation. Co-creating services with citizens and industry (Vol. 12388, pp. 285–296). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64823-7_26

- Horstmann, K. T., Buecker, S., Krasko, J., Kritzler, S., & Terwiel, S. (2021). Who does or does not use the ‘Corona-warn-app’ and why? European Journal of Public Health, 31(1), 49–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa239

- Hyvärinen, H., Risius, M., & Friis, G. (2017). A blockchain-based approach towards overcoming financial fraud in public sector services. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 59(6), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-017-0502-4

- Iansiti, M., & Lakhani, K. R. (2017). Managing our hub economy: Strategy, ethics, and network competition in the age of digital superpowers. Harvard Business Review, 95(5), 84–92.

- Iivari, J., Rotvit Perlt Hansen, M., & Haj-Bolouri, A. (2021). A proposal for minimum reusability evaluation of design principles. European Journal of Information Systems, 30(3), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1793697

- Jung, J. J., & Pham, X. H. (2011). Attribute selection-based recommendation framework for long-tail user group: An empirical study on MovieLens dataset. In P. Jędrzejowicz, N. T. Nguyen, & K. Hoang (Eds.), Computational collective intelligence. Technologies and applications (pp. 592–601). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-23935-9_58

- Klumpe, J., Koch, O. F., & Benlian, A. (2020). How pull vs. Push information delivery and social proof affect information disclosure in location based services. Electronic Markets, 30(3), 569–586. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-018-0318-1

- Kumar, V., & Pansari, A. (2016). Competitive advantage through engagement. Journal of Marketing Research, 53(4), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.15.0044

- Lemke, F., Clark, M., & Wilson, H. (2011). Customer experience quality: An exploration in business and consumer contexts using repertory grid technique. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(6), 846–869. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0219-0

- Lika, B., Kolomvatsos, K., & Hadjiefthymiades, S. (2014). Facing the cold start problem in recommender systems. Expert Systems with Applications, 41(4), 2065–2073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2013.09.005

- Lusch, R. F., & Nambisan, S. (2015). Service innovation: A service-dominant logic perspective. MIS Quarterly, 39(1), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.1.07

- Maedche, A., Gregor, S., Morana, S., & Feine, J. (2019). Conceptualization of the problem space in design science research. In B. Tulu, S. Djamasbi, & G. Leroy (Eds.), Lecture notes in computer science. extending the boundaries of design science theory and practice (Vol. 11491, pp. 18–31). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-19504-5_2

- Mandviwalla, M., & Flanagan, R. (2021). Small business digital transformation in the context of the pandemic. European Journal of Information Systems, 30(4), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2021.1891004

- McConnell, B., & Huba, J. (2007). Citizen marketers: When people are the message. Wokingham, UK: Kaplan Publishing.

- Mendling, J., Pentland, B. T., & Recker, J. (2020). Building a complementary agenda for business process management and digital innovation. European Journal of Information Systems, 29(3), 208–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1755207

- Molitor, D., Reichhart, P., & Spann, M. (2016). Location-based advertising and contextual mobile targeting. ICIS 2016 Proceedings, Dublin, Ireland.

- Molitor, D., Spann, M., Ghose, A., & Reichhart, P. (2018). Measuring the effectiveness of location-based mobile push vs. pull targeting. ICIS 2018 Proceedings, San Francisco, USA.

- Molitor, D., Spann, M., Ghose, A., & Reichhart, P. (2020). Effectiveness of location-based advertising and the impact of interface design. Journal of Management Information Systems, 37(2), 431–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2020.1759922

- Newman, M. E. J. (2016). Networks: An introduction. Reprinted.). Oxford University Press.

- Ondrus, J., Gannamaneni, A., & Lyytinen, K. (2015). The impact of openness on the market potential of multi-sided platforms: A case study of mobile payment platforms. Journal of Information Technology, 30(3), 260–275. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2015.7

- Otto, B., & Jarke, M. (2019). Designing a multi-sided data platform: Findings from the International data spaces case. Electronic Markets, 29(4), 561–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00362-x

- Parker, G., van Alstyne, M. W., & Jiang, X. (2017). Platform ecosystems: How developers invert the firm. SSRN Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2861574

- Purao, S., Kruse, L. C., & Maedche, A. (2020). The origins of design principles: Where do … they all come from? In S. Hofmann, O. Müller, & M. Rossi (Eds.), Lecture notes in computer science. Designing for digital transformation. Co-Creating services with citizens and industry (Vol. 12388, pp. 183–194). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64823-7_17

- Ramaswamy, V. (2009). Leading the transformation to co-creation of value. Strategy & Leadership, 37(2), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1108/10878570910941208

- Recker, J. (2021). Improving the state-tracking ability of corona dashboards. European Journal of Information Systems, 30(5), 476–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2021.1907235

- Reuver, M. D., Sørensen, C., & Basole, R. C. (2018). The digital platform: A research agenda. Journal of Information Technology, 33(2), 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41265-016-0033-3

- Schreieck, M., Wiesche, M., & Krcmar, H. (2016). Design and governance of platform ecosystems – key concepts and issues for future research. ECIS 2016 Proceedings, Istanbul, Turkey.

- Sein, M. K., Henfridsson, O., Purao, S., Rossi, M., & Lindgren, R. (2011). Action design research. MIS Quarterly, 2011(35), 37–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/23043488

- Spagnoletti, P., Resca, A., & Lee, G. (2015). A design theory for digital platforms supporting online communities: A multiple case study. Journal of Information Technology, 30(4), 364–380. https://doi.org/10.1057/jit.2014.37

- Storbacka, K., Brodie, R. J., Böhmann, T., Maglio, P. P., & Nenonen, S. (2016). Actor engagement as a microfoundation for value co-creation. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3008–3017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.02.034

- Tiwana, A. (2014). Platform ecosystems: Aligning architecture, governance, and strategy. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2012-0-06625-2

- Troll, J., Naef, S., & Blohm, I. (2017). A mixed method approach to understanding crowdsourcees’ engagement behavior. Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information Systems, Seoul, South Korea.