ABSTRACT

The objective of the study was to evaluate the outcomes of Brainz, a low intensity community-based treatment programme for people with acquired brain injury (ABI). Participants were 62 people with sustained ABI (5.2 years post-injury, SD = 4.5) and 35 family caregivers. Participants attended two to five cognitive and physical group modules and received two hours of individual home treatment every two weeks. Primary outcomes for people with ABI were participation, perceived difficulties in daily life and need of care, level of goal attainment, and self-esteem. Primary family caregiver outcome was perceived burden of care. Attrition rate of people with ABI was 24% (n = 15), and of family caregivers was 31% (n = 11). People with ABI were more satisfied with the level of their participation after completing Brainz (p < .01), but showed no change in participation frequency or in restrictions (both ps > .01). They perceived fewer difficulties in daily life and less need of care (both ps < .01). Also, in two cognitive modules people improved on their goal achievement (p < .01). However, their self-esteem was reduced (p < .01). Caregiver burden was reduced (p < .01). This study has provided preliminary evidence of the effectiveness of a combined group-based clinical and individual home-based treatment programme, but more research is needed, preferably in larger controlled studies.

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is an important public health problem with a significant global impact. In The Netherlands, between 34,000 and 41,000 adults suffer a stroke each year (Vaartjes et al., Citation2008), making stroke one of the most common causes of disability in adults (Bach et al., Citation2011). Another major cause of disability due to ABI is traumatic brain injury (TBI). In the period 2010–2012, a mean of 34,681 people visited Dutch emergency departments annually due to TBI (Scholten, Haagsma, Panneman, van Beeck, & Polinder, Citation2014). Cognitive, emotional and behavioural problems are common after ABI and can persist long term (Bergersen, Frøslie, Stibrant Sunnerhagen, & Schanke, Citation2010; Hommel et al., Citation2009; Scholten et al., Citation2014; Stocchetti & Zanier, Citation2016). These problems often have a considerable impact on the lives of people with ABI and their families, as they interfere with many aspects of daily and social functioning (Wood & Rutterford, Citation2006). Even people with ABI who do not experience obvious physical consequences due to the brain injury, or those who are discharged from neurorehabilitation, may experience a range of psychosocial consequences once they return to their home environment and try to live an independent life within the full scope of societal participation (Blömer, van Mierlo, Visser-Meily, van Heugten, & Post, Citation2015; Scheenen et al., Citation2016; Tiersky et al., Citation2005; Visser-Meily, van Heugten, Schepers, & van den Bos, Citation2007).

Integrated programmes that address all aspects of brain injury consequences have been shown to be effective in the post-acute and chronic phases after ABI (Chua, Ng, Yap, & Bok, Citation2007; Cicerone et al., Citation2008; Cicerone, Mott, Azulay, & Friel, Citation2004; Malec, Citation2001; Ponsford, Olver, Ponsford, & Nelms, Citation2003; Salazar et al., Citation2000; Sarajuuri et al., Citation2005; Svendsen & Teasdale, Citation2006; Tiersky et al., Citation2005). However, such programmes may be too intensive for people with ABI who are able to function independently in the chronic phase post-injury, but nevertheless experience some difficulties in daily life (Rasquin et al., Citation2010).

There is some evidence for the effectiveness of low intensity integrated outpatient programmes that target cognitive, emotional and behavioural problems in the chronic phase after ABI. Rasquin et al. (Citation2010) and Brands, Bouwens, Gregório, Stapert, and van Heugten (Citation2012) examined the effectiveness of two such rehabilitation programmes for people with ABI in the chronic phase. The purpose of these programmes was to improve participants’ insight into the consequences of the brain damage, to help them learn compensatory strategies and social skills, and to support them in finding new goals and values in life. It appeared that both programmes had a positive effect on the attainment of individual goals set by the participants, but did not result in improvements in the level of participation or in quality of life.

Several explanations have been given by Rasquin et al. (Citation2010) and Brands et al. (Citation2012) for the absence of effects beyond the attainment of individual goals. The lack of effect on quality of life and general participation level might be due to the lower intensity level of their programme in comparison with other programmes. Also, the standardised outcome measures for measuring quality of life and participation level may not focus sufficiently on the participant’s personal problems and perspective, and for that reason these effects could not be captured. Another explanation is that the effects of treatment do not generalise to daily life. Offering a more explicit link between the clinical and home setting may result in more pronounced treatment effects. After all, earlier studies on the effects of cognitive rehabilitation have shown that generalisation does not occur automatically and should be discussed explicitly during learning (Geusgens, Winkens, van Heugten, Jolles, & van den Heuvel, Citation2007). Practising a strategy or skill while varying the practice situation as much as possible is a prerequisite for the occurrence of generalisation.

There have been many studies investigating the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes that take place in either a clinical environment or in the home setting, and studies comparing the effectiveness in both types of settings. For an overview of these studies see the reviews of Turner-Stokes, Pick, Nair, Disler, and Wade, Citation2015, and Brasure et al., Citation2012. However, to our knowledge, there are no studies that have focused on the possible additional gains of a combined programme that treats people with ABI alternately in a clinical and in a home setting.

In this pilot study we therefore evaluate the outcomes of a community-based treatment programme for people with ABI, offered in the chronic phase post-injury. A distinct feature of the Brainz programme is the combination of group sessions in a clinical setting and individual treatment at home. This explicitly encourages generalisation, because participants are supported in applying the skills and knowledge gained in the programme in their own home environment. The Brainz programme consists of a combination of cognitive, psychomotor and physical treatment; using diverse learning domains helps the participant to better comprehend the learned material and implement it in daily routine. The purpose of Brainz is five-fold: (1) to teach people with ABI how to deal with the cognitive, emotional and behavioural problems in order to decrease both their perceived difficulties in daily life and their need of care; (2) to support people with ABI in finding and attaining new goals in life considering the related consequences; (3) to improve social participation; (4) to enhance self-esteem; and (5) to relieve the family caregivers’ burden. In our study, outcomes of the programme are examined for people with ABI and their family caregivers. We hypothesise that, after completing the programme, people with ABI will achieve improvements with respect to (1) perceived difficulties and need of care, (2) attainment of goals, (3) participation, and (4) self-esteem, and that (5) the caregivers’ perceived burden will be reduced.

Method

Study design

A prospective cohort study was conducted. Measurements were obtained before the start of the treatment programme (T0: baseline), one year after the start of the programme (T1), and at the end of each module (between measurements).

Participants

Six healthcare organisations in The Netherlands that specialise in supporting and treating people with ABI and that provided the Brainz programme at the time of the study, participated in the study (Heliomare, InteraktContour, De Noorderbrug, Middin, Stichting Gehandicaptenzorg Limburg and Samenwerkende Woon- & Zorgvoorzieningen). All people with ABI and their caregivers who had been referred to one of the six participating organisations to receive the Brainz programme between September 2014 and January 2015, and who met the inclusion criteria for participation in the programme, were eligible for this study. People with ABI were referred to the Brainz programme by rehabilitation physicians, social workers, general practitioners and the health organisations that provided the Brainz programme themselves.

People with ABI were included in the study if they were over 18 years old, had sustained ABI and experienced cognitive, emotional and/or behavioural problems that interfered with daily functioning, lived at home without receiving medical or rehabilitation treatment, and had sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language to read and understand the questionnaires and give informed consent. In addition, the head practitioner judged suitability for participation in group modules by looking at other characteristics, such as sufficient ability to concentrate and self-reflect, an adequate level of social behaviour, and sufficient cognitive function and motivation to improve one’s functioning. The head practitioner is a health psychologist and has ultimate responsibility for the treatment. People were excluded if they had a progressive neurodegenerative disease (e.g., dementia, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease), severe aphasia, substantial memory deficits, substantial behavioural problems, predominant psychiatric disorders (e.g., serious depression), predominant addiction or substance abuse or other problems in the person’s life impeding the course of the treatment process (e.g., conflicts, financial problems). Suitability for participation in the treatment programme and current study was decided on the basis of clinical judgement.

Family caregivers were included if they expressed the intention to attend the home sessions and, if applicable, the individual sessions of the cognitive modules in which goals were set, had sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language to read and understand the questionnaires and were over 18 years old. The caregiver’s ability to meet these criteria was assessed by the home practitioner. The home practitioner is a cognitive trainer with additional training in the Brainz home treatment programme. A cognitive trainer is either a healthcare- or neuropsychologist, or a care professional with a psychosocial background who has received additional training in the cognitive modules of Brainz. One family caregiver per participating person with ABI was invited to participate in the study.

Intervention

A team of psychologists and behavioural scientists from the participating healthcare organisations selected and developed the programme modules based on existing evidence-based treatment programmes available in The Netherlands, adapting them to fit the intended population. The Brainz programme is developed for people with ABI in the chronic phase who experience cognitive, emotional and/or behavioural problems that interfere with daily functioning. The aims of the Brainz programme are described in the introduction. With these aims, the impairments resulting from the ABI are not treated as such, but participants learn to manage, compensate for and accept these consequences in order to maximise independent functioning and societal participation. Accordingly, the aim is to rebuild the patients’ perspective in life by helping them to set and achieve new goals and enhancing their self-esteem.

Prior to the start of the programme, the person with ABI, the family caregiver and the home practitioner get acquainted with one another. Together they formulate an individual treatment plan including the goals towards which the person with ABI will work throughout the programme. They determine which modules of the Brainz programme best fit the person’s goals and can be followed to achieve them. The assembly of the modules and duration of the programme are thus determined by the individual’s needs and goals.

The Brainz programme consists of attending at least two and at most five group modules and receiving individual treatment at home. The group modules consist of three cognitive modules (“Dealing with change”; “Getting a grip on your energy”; “Thinking and doing”) and two physical modules (“Getting active A” and “Getting active B”). A group consists of a minimum of six and a maximum of eight participants. One trainer conducts the group sessions, but when there are more than six in the group, a second trainer may assist.

The three cognitive modules are conducted by a cognitive trainer and each module consists of 14 sessions. The modules start with an individual session in which the goals for this specific module are set, followed by 12 weekly group sessions of two hours, and end with an individual session in which the goals are evaluated. For the individual sessions, the family caregiver is invited, along with the person with ABI, the cognitive trainer and the home practitioner.

The two physical modules are conducted by a psychomotor therapist or physiotherapist with additional training in the physical modules. The physical modules consist of 28 two-hour sessions, offered twice a week for 14 weeks. They are offered alongside the cognitive modules so that the material learned can be put into practice directly. For example, if the cognitive module “Getting a grip on your energy” discusses the topic of relaxation, the physical module teaches participants relaxation techniques. The physical modules can be followed only in combination with a cognitive module.

In addition, every two weeks participants receive individual home treatment sessions of two hours, which continue as long as the person with ABI follows the modules of Brainz. Family caregivers are invited to attend these home sessions. During home treatment, the home practitioner is in regular contact with the home environment of the person with ABI and aims to support the family system to cope with the changed situation, such as changed roles, burden of care and the capacity of family and friends for support. Also, the home practitioner helps the participant apply the knowledge and skills that he or she learned in the group interventions in daily life situations.

Procedure

After referral to the Brainz treatment programme, people with ABI and family caregivers were asked to participate in the current study. After informed consent was obtained, baseline measurements were conducted. Participants were asked to complete the questionnaires themselves and could get assistance from the home practitioner, research assistant or other healthcare professional (if not a practitioner) if necessary. Questionnaires had to be completed two weeks before the participant started the Brainz programme (T0) and 12 months after the start of the programme (T1). Exceptions were the goal attainment thermometer, the Berg Balance Scale and a 10 metre timed walking test, which were inherent parts of the programme and conducted only at the beginning and end of a module (between measurements) by the practitioners.

Measurements

Demographic and injury-related characteristics were collected by the home practitioner or research assistant by means of a questionnaire, including age and sex of participants, relationship between the person with ABI and the family caregiver, educational level, employment status, type of household, time since injury, age at injury, cause of injury and cognitive functioning of people with ABI. Cognitive function was measured by the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA 30 point test; Nasreddine et al., Citation2005); a score of < 26 out of 30 indicates mild cognitive impairment in a population with cerebrovascular disease (Pendlebury, Mariz, Bull, Mehta, & Rothwell, Citation2012).

Primary outcome measures for people with ABI

Participation of people with ABI was measured with the Utrecht Scale for Evaluation of Rehabilitation-Participation (USER-P), which rates objective and subjective participation in persons with physical disabilities (Post et al., Citation2012). The USER-P has acceptable reproducibility and good validity in rehabilitation outpatients, and the internal consistencies of the scales are satisfactory (α 0.70–0.91; Post et al., Citation2012). The USER-P is comprised of 32 items in three scales: Frequency, Restrictions and Satisfaction. The frequency of activities is assessed based on hours per week spent on vocational activities (four items) and on the frequency of leisure and social activities in the last four weeks (seven items). Participation restrictions experienced because of health conditions are assessed by 11 items (Likert-scale: “not possible to perform” to “performed without difficulty”). Satisfaction with participation is assessed by 10 items (Likert-scale: “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied”). Total scores are calculated per scale by summing up the item scores and transforming these scores linearly into a 0–100 scale. Higher total scores indicate a higher level of participation (higher frequency, less restrictions and higher satisfaction).

Perceived difficulties in daily life and need of care were assessed by the Need of Care questionnaire which was developed for the purpose of this study. We developed a new questionnaire because other well-validated questionnaires assessing functional capacity in the participation domain were too extensive and therefore not suitable to apply to the participants. The Need of Care questionnaire is based on the participation domain of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model (World Health Organization, Citation2001). The questionnaire contains 10 items with regard to communication, mobility, moving and getting around, self-care, domestic responsibilities, relationships, interacting with other people, work and school, financial and administrative and leisure activities. For each item, the person with ABI was asked if he or she perceived difficulty in daily life (yes or no), and, if yes, if he or she was in need of care (yes or no). Two scores were calculated per person; one assessing perceived difficulties and one assessing need of care. The scores are a summed amount reflecting the number of items to which individuals responded yes. Scores range from 0–10; higher scores indicate more perceived difficulties in daily life and more care needs, respectively.

Level of goal attainment was also measured. An individual goal session at the start of a cognitive module took place in which the person with ABI set goals together with the family caregiver, cognitive trainer and home practitioner. Goals had to be specific, measurable, attainable, realistic and timely. In this session, the participant assessed how well the baseline situation was with regard to the goal, by scoring the level of attainment on a so-called goal attainment thermometer. The intended level was also depicted. The goals were evaluated at the end of the module by filling in the goal attainment thermometer for the second time. Thermometer scores range from 1 = “I am really bad at this” to 10 = “I am really good at this”. We used this adapted measure of goal attainment scaling because the conventional Goal Attainment Scaling process appeared to be too difficult to apply for the participants while a thermometer is easy and straightforward to understand. The goal thermometers were developed by the developers of the Brainz programme.

Global self-esteem was assessed by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, Citation1979). Earlier research supports the usefulness of the Dutch RSES as a measure for global self-esteem (Everaert, Koster, Schacht, & De Raedt, Citation2010; Franck, de Raedt, Barbez, & Rosseel, Citation2008). The instrument contains 10 questions and is scored using four response choices, ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Total scores range from 0 to 30; higher scores indicate higher self-esteem.

Secondary outcome measures for people with ABI

Secondary outcomes were functional status (Darthmouth COOP Functional Health Assessment Charts/World Organisation of Family Doctors; COOP/WONCA; Van Weel, König-Zahn, Touw-Otten, van Duijn, & Meyboom-de Jong, Citation2012), neuropsychiatric symptoms (Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire; NPI-Q; Kaufer et al., Citation2000), balance (Berg Balance Scale; Berg, Wood-Dauphine, Williams, & Gayton, Citation1989), and functional mobility (10 Metre Timed Walking Test; Collen, Wade, & Bradshaw, Citation1990). The latter two tests were administered at the start and end of the physical modules.

Primary outcome measure for family caregivers

Family caregivers’ perceived burden of care was assessed with the Caregiver Strain Index (CSI; Robinson, Citation1983). By asking about caregivers’ experiences in 13 common problem areas, the CSI leads to a non-weighted sum score ranging from 0 to 13. A score higher than six indicates high strain on the caregiver.

Secondary outcome measure for family caregivers

Family caregivers’ life satisfaction was measured by the Life Satisfaction Questionnaire-9 (LiSat-9; Boonstra, Reneman, Stewart, & Balk, Citation2012). In this study we assessed only one aspect, namely “life as a whole”.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the background characteristics. To investigate the treatment results, differences in outcome measures between T0 and T1 were tested using paired samples t-tests. A Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was used if the distribution was skewed. The alpha level was set at .01 (two-sided). A more stringent alpha level was chosen to correct for multiple testing. Statistical analyses were performed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 22).

Ethical considerations

The Medical Ethics Committee of Maastricht University Medical Centre assessed the study protocol, but approval was not necessary because all measurements were conducted as part of routine clinical practice. All participants gave written consent for use of their data for this study.

We have conducted a separate process evaluation in which we address the feasibility of the programme, including issues such as how treatment integrity was maintained and monitored. We are currently preparing an article on the process evaluation.

Results

Participants and practitioners

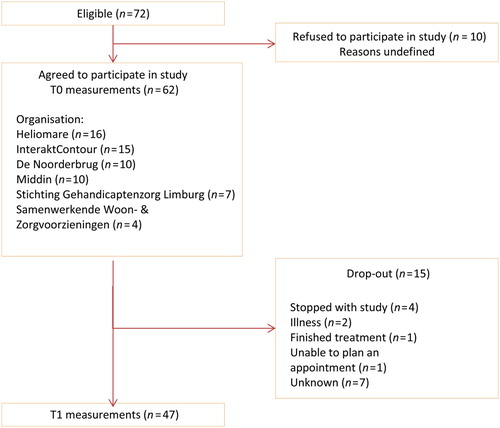

At the start of the study, 72 persons with ABI entered the Brainz programme (see flowchart in ). Ten people refused participation in the study for undefined reasons. The remaining 62 people (86%) were included in this study. During the study period, 15 people (24%) were not included in the between and/or T1 measurements. The reasons for dropping out are shown in .

Figure 1. Flow of people with ABI through the study. T0: prior to the start of the programme; T1: one year after the start of the programme.

presents the demographic characteristics of people with ABI (n = 62). Most people were middle-aged (M = 52.4, SD = 11.6) and 57% (n = 35) were male. More than half the people had a low level of education (n = 43, 69%). A small number had a job at the start of the Brainz programme (n = 6, 10%), in comparison with the situation before the ABI (n = 45, 73%). presents the medically relevant characteristics. The most frequent cause of brain injury was stroke (n = 33, 54%), followed by TBI (n = 15, 25%). The mean time since injury was 5.2 years (SD = 4.5). The vast majority of people with ABI (66%) scored below the threshold of the MoCA (26), indicating mild cognitive impairment.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of people with ABI (n = 62).

Table 2. Medically relevant characteristics of people with ABI (n = 61).

Of the 62 individuals with ABI that were included in the study, 35 (56%) had a family caregiver who wanted to be involved in the Brainz programme and agreed to participate in the study. During the study period, 11 caregivers (31%) were not included in the measurements at T1. Six of them dropped out because the person with ABI dropped out. The reasons the other five dropped out are unknown.

The mean age of family caregivers (n = 35) was the same as the mean age of people with ABI (M = 52.8, SD = 12.1, range 33–75) and 43% (n = 15) were male. The most frequent relationship between caregivers and people with ABI was partner (n = 26, 74%), followed by brother/sister (n = 5, 14%), parent (n = 1, 3%), child (n = 1, 3%), cousin (n = 1, 3%), and daughter in law (n = 1, 3%). Three-quarters of the caregivers (n = 26, 74%) lived with the person with ABI.

The vast majority of people with ABI (n = 50, 86%) attended at least two group modules and received individual home treatment. The module “Dealing with change” was the most frequently received group module (n = 52, 90%), followed by “Getting Active A” and/or “Getting Active B” (n = 43, 74%) and “Getting a grip on your energy” (n = 32, 55%). On average, people with ABI followed 13 out of 14 sessions for “Dealing with change” and “Getting a grip on your energy” and 11 out of 14 sessions for “Thinking and doing”. Furthermore, 19 out of 28 sessions for “Getting active A” and 18 out of 28 sessions for “Getting active B” were followed. Participants received a mean of 82.0 minutes of home treatment (SD = 41.0, range 4–190). Two people with ABI (3%) did not receive individual home treatment.

The mean time between T0 and T1 was 11.2 months (SD = 1.4, range 7.5–15.7). By mistake, the T1 measurement of one person with ABI took place at the completion of the programme (7.5 months after T0 measurement) instead of 12 months after T0, and the T1 measurements of two individuals were completed longer than 15 months after T0. Furthermore, the T1 measurements of some people with ABI were conducted before treatment had been completed. Unfortunately the number of participants for which this was the case is unknown.

Most head practitioners, cognitive group trainers, home practitioners, and physical group trainers that conducted the group modules or home treatment had an appropriate background with additional training in Brainz (98%, 94%, 100%, 58%, respectively).

Outcomes of the programme

presents the results of the paired samples t-tests that were conducted to compare the primary outcome measures at the end of the Brainz programme with those at the start of the programme. Considering the USER-P, people with ABI were significantly more satisfied with their level of participation at the end of the programme (t = 3.4, p < .01), but showed no significant change in frequency of and restrictions on participation (t = 1.5, p > .01 and t = 1.1, p > .01, respectively). Furthermore, people with ABI perceived significantly fewer difficulties in daily life and less need of care after completing Brainz (t = −3.0, p < .01 and t = −3.2, p < .01). However, people’s self-esteem (RSES) was significantly reduced following the programme (t = −2.9, p < .01). As for family caregivers, their burden of care (CSI) was found to have been reduced significantly at the end of the programme (t = 3.4, p < .01).

Table 3. Mean scores on the primary outcome measures.

The results of the goal attainment thermometers that were used during the cognitive modules are presented in . Since the scores of the modules “Getting a grip on your energy” and “Thinking and doing” were not normally distributed, the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test was run for all three cognitive modules to assess whether the median scores differed over time. For all cognitive modules (“Dealing with change”, “Getting a grip on your energy”, and “Thinking and doing”), the level of goal attainment at the end of the module was higher than at the start of the module, although the difference for the “Thinking and doing” module did not reach statistical significance (Z = 5.0, p < .001; Z = 3.2, p < .01; Z = 2.5, p > .01, respectively). Also, people with ABI participating in the modules “Getting a grip on your energy” and “Thinking and doing” achieved an end score that was comparable to the intended end score they had depicted on their thermometers at the start of the module (Z = 1.1, p > .01 and Z = 1.9, p > .01, respectively). However, people participating in the module “Dealing with change” scored significantly lower at the end of the module than intended (Z = 2.8, p < .01).

Table 4. Median scores on the goal attainment thermometer, per module.

The results of the secondary outcome measures are presented in . Concerning functional status (COOP/WONCA), the domains physical fitness, feelings, daily activities, and social activities were better post-programme in comparison with pre-progamme, but none of these changes reached statistical significance. Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI-Q) showed a significant difference between T0 and T1 (M = 24.8, SD = 15.9 versus M = 15.3, SD = 16.9, respectively, t = 3.6, p < .01), indicating that people with ABI experienced fewer and milder neuropsychiatric symptoms. Balance (Berg Balance Scale) and functional mobility (10 Metre Timed Walking Test) also improved (Z = 4.2, p < .001; Z = 3.0, p < .01, respectively). With respect to the family caregivers, life satisfaction (LiSat-9) was higher at the end of the programme, in comparison with life satisfaction at the start of the programme, although this difference did not reach significance (t = 2.5, p > .01).

Table 5. Mean scores on the secondary outcome measures.

Discussion

The present pilot study was performed to examine the outcomes of a newly developed community-based treatment programme offered to people with ABI in the chronic phase post-injury and their family caregivers. We showed that significant improvements were achieved in people’s satisfaction with their level of participation, in perceived difficulties in daily life and related need of care, in attainment of individual goals in two cognitive modules, in perceived neuropsychiatric symptoms, and in balance and functional mobility after completion of the programme. Moreover, significant improvements were reached with respect to the perceived burden of the family caregiver.

However, we did not find significant improvements in the other participation domains (frequency and restrictions), nor in any of the functional status domains (physical fitness, feelings, daily and social activities and overall health). Also, the self-esteem of people with ABI decreased after the programme. Finally, we did not find a significant improvement in the life satisfaction of the family caregivers.

A possible explanation for the fact that people’s satisfaction with their level of participation increased even though no improvement occurred in frequency of participation or in restrictions on participation, is that people with ABI became better adjusted to their disabilities. After all, the need for care was also reduced. Second, perhaps the fact that they participated in the programme made them feel more satisfied with their participation level, even though it did not help them decrease their perceived restrictions and, subsequently, did not help them to participate more in other activities outside the programme. Another explanation is that people with ABI had already adjusted to leisure and social activities in the years before participating in the programme, since it is probably easier to adjust to these types of activities in comparison with vocational activities (Blömer et al., Citation2015). It is therefore possible that, after the programme, the frequency of participation and the amount of participation restrictions experienced had improved in vocational activities, but not in leisure and social activities. However, in this study we did not differentiate for type of activity.

The reduced self-esteem in the present study may be the result of people with ABI gaining more insight into their own functioning. The same is seen when people with ABI return home after being discharged from hospital or inpatient neurorehabilitation and return to their pre-injury daily routines: most people are faced with a range of psychosocial consequences when they try to live an independent life (Tiersky et al., Citation2005; Visser-Meily et al., Citation2007). It is known that ABI has a negative impact on self-esteem and feelings of competence, which is in turn associated with negative emotional consequences, maladaptive coping and reduced community participation (Longworth, Deakins, Rose, & Gracey, Citation2016; Ponsford, Kelly, & Couchman, Citation2014). The study of Longworth et al. (Citation2016) suggests that negative social evaluations are key targets for cognitive intervention with ABI survivors; more research is needed to design therapeutic interventions targeting the increase of self-esteem after ABI. For our programme, we suggest that practitioners direct more explicit attention towards, for example, perceptions of being unlikeable after ABI, as well as towards the perceived likelihood of negative evaluation due to acquired impairments and towards the perceived low self-efficacy to withstand difficulties.

This study indicated a significant degree of attainment of predefined individual goals for two out of three cognitive modules. We did not find significant attainment for “Thinking and doing” which might be due to the small number of participants in this module. Rasquin et al. (Citation2010) and Brands et al. (Citation2012) also found significant improvement on reaching individualised goals. Since Rasquin et al. (Citation2010) did not find evidence for fewer cognitive failures, improved quality of life or higher levels of participation, Brands et al. (Citation2012) explain that the positive effects on Goal Attainment Scaling in both studies might be explained by such shared characteristics as provision of information, group sessions facilitating contact with and support from fellow participants, and positive reinforcement. Indeed, Brainz also has these characteristics and these are plausible explanations for the attainment of goals that we found.

Considering the improvements we found on the various outcome measures, Brainz seems to be a valuable alternative to the low intensity, outpatient rehabilitation programmes evaluated by Rasquin et al. (Citation2010) and Brands et al. (Citation2012). Contrary to our findings, these studies did not find any significant improvements on people’s physical and psychological health status or improvement in family caregivers’ perceived burden of care. Possibly our positive findings are the result of offering a more explicit link between the group-based clinical and home-based settings, thereby providing the opportunity to explicitly discuss generalisation, which was not done during the programmes of Rasquin et al. (Citation2010) and Brands et al. (Citation2012).

Although there are, to our knowledge, no other studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes that provide treatment in both the clinical and home settings, it stands to reason that such programmes have potential benefits for people with ABI in the chronic phase, in comparison with programmes that take place only in a clinical environment. In the first place, it is known from studies in rehabilitation settings that in order to facilitate generalisation, training locations and materials should bear as close a resemblance to the person’s experience and daily life as possible (Geusgens et al., Citation2007). For example, a recent review by Krasny-Pacini, Chevignard, and Evans (Citation2014) found that the effectiveness of goal management training in people with ABI was greater when it was combined with other interventions such as personal homework and daily life training activities rather than with paper-and-pencil, office-type tasks. Furthermore, the Evidence-Based Review of Moderate to Severe Acquired Brain Injury project (Brasure et al., Citation2012) concluded that transitional living settings during the last weeks of inpatient rehabilitation are associated with greater independence than inpatient rehabilitation alone. In another review, which discussed the effectiveness of remediation of language and communication deficits in people with TBI and stroke, Cicerone et al. (Citation2005) suggest that interventions provided in the home or community by trained volunteers or caretakers may be valuable adjuncts to traditional treatments, particularly for chronic aphasia. Finally, in a review that evaluated the effectiveness of errorless learning of everyday tasks in people with minimal to moderate dementia, four studies were mentioned that promoted additional practice in the home environment, and all four were found to be effective in the short and long term (De Werd, Boelen, Olde Rikkert, & Kessels, Citation2013).

Shortcomings and strengths of the study

The results should be interpreted against the shortcomings of the study. First of all, there was no control group, which means we cannot attribute the differences in baseline and post-treatment outcomes to the treatment. This complicates the interpretation of our data. Furthermore, the study is based on a small sample; only 47 participants out of the 72 participants that were referred to the Brainz programme were included in the T1 measurements. Because of the small sample size we did not investigate treatment effects in subgroups of participants. Therefore, this study provides an initial insight into the programme’s effects on a wide array of outcome measures; a randomised controlled trial is recommended in order to assess whether the results observed are induced by the intervention. It would be valuable to compare Brainz to other treatment programmes that have demonstrated effectiveness for people with ABI in the chronic phase and to conduct a cost-effectiveness study. Also, this study lacked a long-term follow-up assessment investigating whether the improvements last. It is therefore recommended that a follow-up measurement be conducted one year after the treatment programme is completed. No information on the reliability and validity of the Need of Care questionnaire was available. Finally, the study took place just after the Brainz programme had been initiated, and there were several teething problems in the procedures.

Several strengths of the current study are noteworthy. First, the study had a broad population, including people with ABI in the chronic phase, with different causes and of all ages, who were treated by a considerable number of health organisations. This increases the generalisability of our results. In addition, the group modules and the individual home treatment sessions formed an integrated programme in which participants and practitioners worked towards achieving the participants’ individual goals throughout the programme, these were always in line with the five generic aims of Brainz. In this way, the outcomes of the programme that focused on participants’ individual goals and personal difficulties could be captured by generic outcome measures and we could detect the outcomes that we expected.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Brainz is a promising intervention, as our study shows that the treatment programme reached almost all of its main aims. Our results indicate that the programme (1) reduced people’s perceived difficulties in daily life and their need of care; (2) supported people with ABI in attaining new goals in life; (3) improved perceived social participation; and (4) relieved family caregivers’ perceived burden of care. However, the programme did not improve the frequency of participation nor decrease restrictions on participation, and it reduced the self-esteem of people with ABI. More research in larger, controlled studies is needed to confirm these results. In addition, maintaining self-esteem is an important matter that merits more attention.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants, the healthcare professionals who led the group sessions and who did the in-home sessions, the research assistants and the Brainz research group for participating in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bach, J. P., Riedel, O., Pieper, L., Klotsche, J., Dodel, R., & Wittchen, H. U. (2011). Health-related quality of life in patients with a history of myocardial infarction and stroke. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 31(1), 68–76. doi: 10.1159/000319027

- Berg, K., Wood-Dauphine, S., Williams, J. I., & Gayton, D. (1989). Measuring balance in the elderly: Preliminary development of an instrument. Physiotherapy Canada, 41(6), 304–311. doi: 10.3138/ptc.41.6.304

- Bergersen, H., Frøslie, K. F., Stibrant Sunnerhagen, K., & Schanke, A. K. (2010). Anxiety, depression, and psychological well-being 2 to 5 years poststroke. Journal of Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, 19(5), 364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.06.005

- Blömer, A. M., van Mierlo, M. L., Visser-Meily, J. M., van Heugten, C. M., & Post, M. W. (2015). Does the frequency of participation change after stroke and is this change associated with the subjective experience of participation? Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 96(3), 456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.09.003

- Boonstra, A. M., Reneman, M. F., Stewart, R. E., & Balk, G. A. (2012). Life satisfaction questionnaire (Lisat-9): reliability and validity for patients with acquired brain injury. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 35(2), 153–160. doi: 10.1097/MRR.0b013e328352ab28

- Brands, I. M. H., Bouwens, S. F. M., Gregório, G. W., Stapert, S. Z., & van Heugten, C. M. (2012). Effectiveness of a process-oriented patient-tailored outpatient neuropsychological rehabilitation programme for patients in the chronic phase after ABI. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation: An International Journal, 1–14. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2012.734039

- Brasure, M., Lamberty, G. J., Sayer, N. A., Nelson, N. W., MacDonald, R., Ouellette, J., … Wilt, T. J. (2012). Multidisciplinary postacute rehabilitation for moderate to severe traumatic brain injury in adults. AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC101-EF. Rockville (Maryland): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- Chua, K. S., Ng, Y. S., Yap, S. G., & Bok, C. W. (2007). A brief review of traumatic brain injury rehabilitation. Annual Academic Medicine Singapore, 36(1), 31–42.

- Cicerone, K. D., Dahlberg, C., Malec, J. F., Langenbahn, D. M., Felicetti, T., Kneipp, S., … Catanese, J. (2005). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 1998 through 2002. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 86(8), 1681–92. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.024

- Cicerone, K. D., Mott, T., Azulay, J., & Friel, J. C. (2004). Community integration and satisfaction with functioning after intensive cognitive rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85(6), 943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.07.019

- Cicerone, K. D., Mott, T., Azulay, J., Sharlow-Galella, M. A., Ellmo, W. J., Paradise, S., & Friel, J. C. (2008). A randomized controlled trial of holistic neuropsychologic rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 89, 2239–2249. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.06.017

- Collen, F. M., Wade, D. T., & Bradshaw, C. M. (1990). Mobility after stroke: reliability of measures of impairment and disability. International disability studies, 12(1), 6–9. doi: 10.3109/03790799009166594

- De Werd, M. M., Boelen, D., Olde Rikkert, M. G. M., & Kessels, R. P. C. (2013). Errorless learning of everyday tasks in people with dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 8, 1177–1190. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S46809

- Everaert, J., Koster, E., Schacht, R., & De Raedt, R. (2010). Evaluatie van de psychometrische eigenschappen van de Rosenberg zelfwaardeschaal in een poliklinisch psychiatrische populatie. [in Dutch] Gedragstherapie, 43, 307–317.

- Franck, E., de Raedt, R., Barbez, C., & Rosseel, Y. (2008). Psychometric properties of the dutch rosenberg self-Esteem scale. Psychologica Belgica, 48(1), 28–35. doi: 10.5334/pb-48-1-25

- Krasny-Pacini, A., Chevignard, M., & Evans, J. (2014). Goal Management Training for rehabilitation of executive functions: A systematic review of effectiveness in patients with acquired brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(2), 105–116. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.777807

- Geusgens, C. A., Winkens, I., van Heugten, C. M., Jolles, J., & van den Heuvel, W. J. (2007). Occurrence and measurement of transfer in cognitive rehabilitation: A critical review. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 39(6), 425–439. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0092

- Hommel, M., Trabucco-Miguel, S., Joray, S., Naegele, B., Gonnet, N., & Jaillard, A. (2009). Social dysfunctioning after mild to moderate first-ever stroke at vocational age. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 80(4), 371–375. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.157875

- Kaufer, D. I., Cummings, J. L., Ketchel, P., Smith, V., MacMillan, A., Shelley, T., … DeKosky, S. T. (2000). Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry & Clinical Neurosciences, 12(2), 233–239. doi: 10.1176/jnp.12.2.233

- Longworth, C., Deakins, J., Rose, D., & Gracey, F. (2016). The nature of self-esteem and its relationship to anxiety and depression in adult acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2016.1226185

- Malec, J. F. (2001). Impact of comprehensive day treatment on societal participation for persons with acquired brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 82(7), 885–895. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.23895

- Nasreddine, Z. S., Phillips, N. A., Bédirian, V., Charbonneau, S., Whitehead, V., Collin, I., … Chertkow, H. (2005). The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(4), 695–699. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x

- Pendlebury, S. T., Mariz, J., Bull, L., Mehta, Z., & Rothwell, P. M. (2012). MoCA, ACE-R, and MMSE versus the national institute of neurological disorders and stroke-Canadian stroke network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards neuropsychological battery after TIA and stroke. Stroke, 43(2), 464–469. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.111.633586

- Ponsford, J., Kelly, A., & Couchman, G. (2014). Self-concept and self-esteem after acquired brain injury: A control group comparison. Brain Injury, 28(2), 146–54. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.859733

- Ponsford, J., Olver, J., Ponsford, M., & Nelms, R. (2003). Long-term adjustment of families following traumatic brain injury where comprehensive rehabilitation has been provided. Brain Injury, 17(6), 453–468. doi: 10.1080/0269905031000070143

- Post, M. W., van der Zee, C. H., Hennink, J., Schafrat, C. G., Visser-Meily, J. M., & van Berlekom, S. B. (2012). Validity of the utrecht scale for evaluation of rehabilitation-participation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 34(6), 478–485. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2011.608148

- Rasquin, S. M., Bouwens, S. F., Dijcks, B., Winkens, I., Bakx, W. G., & van Heugten, C. M. (2010). Effectiveness of a low intensity outpatient cognitive rehabilitation programme for patients in the chronic phase after acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 20(5), 760–777. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2010.484645

- Robinson, B. C. (1983). Validation of a caregiver strain index. Journal of Gerontology, 38(3), 344–348. doi: 10.1093/geronj/38.3.344

- Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books.

- Salazar, A. M., Warden, D. L., Schwab, K., Spector, J., Braverman, S., Walter, J., … Ellenbogen, R. G. (2000). Cognitive rehabilitation for traumatic brain injury: A randomized trial. Defense and Veterans Head Injury Program (DVHIP) Study Group. Journal of the American Medical Association, 283(23), 3075–3081.

- Sarajuuri, J. M., Kaipio, M. L., Koskinen, S. K., Niemela, M. R., Servo, A. R., & Vilkki, J. S. (2005). Outcome of a comprehensive neurorehabilitation program for patients with traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 86, 2296–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.06.018

- Scheenen, M. E., Spikman, J. M., de Koning, M. E., van der Horn, H. J., Roks, G., Hageman, G., & van der Naalt, J. (2016). Patients “At Risk” of suffering from persistent complaints after mild traumatic brain injury: The role of coping, mood disorders, and post-Traumatic stress. Journal of Neurotrauma. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1089/neu.2015.4381

- Scholten, A. C., Haagsma, J. A., Panneman, M. J. M., van Beeck, E. F., & Polinder, S. (2014). Traumatic brain injury in The Netherlands: Incidence, costs and disability-Adjusted life years. PLOS ONE, 9(10), e110905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110905

- Stocchetti, N., & Zanier, E. R. (2016). Chronic impact of traumatic brain injury on outcome and quality of life: A narrative review. Critical Care, 20(1), 148. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1318-1

- Svendsen, H. A., & Teasdale, T. W. (2006). The influence of neuropsychological rehabilitation on symptomatology and quality of life following brain injury: A controlled long-term follow-up. Brain Injury, 20, 1295–1306. doi: 10.1080/02699050601082123

- Tiersky, L. A., Anselmi, V., Johnston, M. V., Kurtyka, J., Roosen, E., Schwartz, T., & DeLuca, J. (2005). A trial of neuropsychologic rehabilitation in mild-spectrum traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 86, 1565–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.013

- Turner-Stokes, L., Pick, A., Nair, A., Disler, P. B., & Wade, D. T. (2015). Multi-disciplinary rehabilitation for acquired brain injury in adults of working age. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 12, CD004170. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004170.pub3

- Vaartjes, I., Reitsma, J. B., de Bruin, A., Berger-van Sijl, M., Bos, M. J., Breteler, M. M., … Bots, M. L. (2008). Nationwide incidence of first stroke and TIA in the Netherlands. European Journal of Neurology, 15(12), 1315–1323. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02309.x

- Van Weel, C., König-Zahn, C., Touw-Otten, F., van Duijn, N., & Meyboom-de Jong, B. (2012). Measuring functional status with the COOP/WONCA charts: a manual. Second revised edition. UMCG/University of Groningen, Research Institute SHARE

- Visser-Meily, J., van Heugten, C., Schepers, V., & van den Bos, G. (2007). There are also suitable treatments during the chronic phase following a stroke. [in Dutch] Nederlands Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde, 15(151), 2753–2757.

- World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health: ICF. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Wood, R. L. I., & Rutterford, N. A. (2006). The effect of litigation on long term cognitive and psychosocial outcome after severe brain injury. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21(3), 239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2005.12.004