ABSTRACT

Outcome measurement is the cornerstone of evidence-based health care including neuropsychological rehabilitation. A complicating factor for outcome measurement in neuropsychological rehabilitation is the enormous number of measures available and the lack of a standard set of outcome measures. As a first step towards such a set, we reviewed intervention evaluation studies of the last 20 years to get an overview of instruments used for measuring outcome. The instruments were divided into two main categories: neuropsychological tests (International Classification of Functioning (ICF) level of functions) and other instruments (all other ICF domains). We considered the most common cognitive domains: memory, attention, executive functions, neglect, perception, apraxia, language/communication and awareness. Instruments used most for measuring outcome were neuropsychological tests (n = 215) in the domains of working memory, reaction times, neglect and aphasia. In the second category (n = 166) the multi-domain instruments were most represented. Several steps can be taken to select a standard set of outcome measures for future use. Next to evaluation of quality and feasibility of the instruments, expert opinion and consensus procedures can be applied.

Introduction

Measuring the outcome of health care is “a central component of determining therapeutic effectiveness and, therefore, the provision of evidence-based healthcare” (van der Putten, Hobart, Freeman, & Thompson, Citation1999, pp. 480–484). This is not different for neuropsychological rehabilitation. In clinical practice it is common to test and measure extensively as part of the diagnostic assessment (i.e., neuropsychological assessment). However, neuropsychological assessment is less often used to measure post-treatment outcomes (Casaletto & Heaton, Citation2017). This is not surprising given the traditional focus of (clinical) neuropsychology on diagnostics. Also, neuropsychological assessment has a longstanding tradition in deficit measurement for which many instruments with excellent psychometric properties are available (i.e., Lezak, Howieson, Bigler, & Tranel, Citation2012). The focus on other domains besides neuropsychological impairments (i.e., activities, participation, and quality of life) has evolved later and therefore less validated instruments are available for use in clinical neuropsychology. Since the aim of neuropsychological rehabilitation is much broader than reducing cognitive deficits but rather to enable patients to live with, manage, by-pass, or come to terms with cognitive deficits precipitated by injury to the brain (Wilson, Citation1997) other outcome measures, in addition to neuropsychological tests are needed.

There are many reasons why outcome measurement is important. Tate (Citation2014) mentions the following reasons: “to document improvement or deterioration, for differential diagnosis, to evaluate treatment effectiveness, to identify areas of need, plan treatments, help people make practical decisions, and educate people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) and their family professionals and other professionals” (Tate, Citation2014, pp. 163–164). Others have also mentioned quality assurance and accountability purposes (Haigh et al., Citation2001). Outcome measurement can have different goals for various stakeholders. For (fundamental) researchers and clinicians efficacy is most relevant: does this treatment work, why and how and for whom? For applied researchers, clinicians but also for the patients and their family effectiveness is more important: Is the treatment beneficial/helpful for the patient group or for the individual patient? And finally, one can also consider efficiency: does the treatment work as expected and what is the cost–benefit ratio? In current health care, quality, cost-effectiveness and patient-centricity are key elements leading to many different systems and ways of measuring outcome. Along this line, the National Institute of Health (NIH) stimulates the development of Common Data Elements (CDEs) in neuroscience to improve research quality and the ability to transfer information between centres and allows for comparison and meta-analyses (Van Heugten, Citation2017). Just to name a few recent developments related to CDEs: in the field of neurology NEURO-QOL was developed which is a brief, reliable, valid, standardized quality of life assessment which can be applied across different neurological diseases (Cella et al., Citation2012), and the NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioural function is now available consisting of a standard set of concise, well-validated instruments (Gershon et al., Citation2012). Recently, an international standard set of Patient Centered Outcome Measures (PCOMs) after stroke was proposed to enable the assessment of healthcare value and stimulate value-based health care in which patients and costs are brought together (Salinas et al., Citation2016).

Over the years, recommendations on common outcome measures in traumatic brain injury research have been put forward, such as by Wilde and colleagues in 2010 (Wilde et al., Citation2010) and Tate and colleagues in 2013 (Tate, Godbee, & Sigmundsdottir, Citation2013). Recently, recommendations were published on outcome instruments for use in psychosocial research on patients with moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Honan et al., Citation2017). In total 56 instruments were recommended through nomination, literature search and expert opinion. These instruments represent all levels of the International Classification of Functioning (ICF): body functions, activities/participation, environmental and personal factors; and additionally, health-related quality of life. However, neuropsychological rehabilitation is aimed at other groups of patients with acquired brain injury besides TBI. Measuring outcome of neuropsychological rehabilitation may therefore entail other instruments than the ones recommended by Wilde et al. (Citation2010), Tate et al. (Citation2013), and Honan et al. (Citation2017). In addition, none of these studies is aimed at neuropsychological rehabilitation. The recommendations of Honan et al. aim at psychosocial research. Psychosocial studies entail the mental, emotional, social, and spiritual effects of a disease. Although psychosocial research is closely related to the aims of neuropsychological rehabilitation, it does not fully overlap. From our point of view, therefore, an overview of outcome measures for neuropsychological rehabilitation research is lacking.

To measure the outcome of neuropsychological rehabilitation, and allow for comparison and meta-analyses, a standard set of outcome measures is not yet available and researchers and clinicians are confronted with an overwhelming number of available instruments to choose from. To facilitate this choice, and as a first step towards a possible standard set of outcome measures in neuropsychological rehabilitation we performed a review of currently used outcome measures with a focus on intervention evaluation. We therefore reviewed outcome measures used in studies evaluating the outcomes of neuropsychological rehabilitation programmes in the last 20 years in our field. for each outcome measure we will present the frequency of use and we will group the instruments according to the framework of the International Classification of Functioning (ICF; World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2001) which informs us about the outcome domains which have been considered (most). Our overview is mainly aimed at the most common forms of acquired brain injury in adult (neuropsychological) rehabilitation being stroke and traumatic brain injury. The aim of this review was to identify outcome measures, which have been used in intervention research until now in order to offer researchers and clinicians an overview of the many outcome measures which are available. The overview can help to choose measurement instruments for future use. In this paper, we present the results of this review and propose future steps to come to a standard set of outcome measures and to help researchers and clinicians to choose among these many instruments in future. The instruments are divided into two main categories: neuropsychological tests and other measures.

Methods

Eligibility criteria. We aimed to give an overview of outcome measures, which were used in studies evaluating the outcome of neuropsychological interventions over the past 20 years. Reviews presenting the best evidence in terms of treatment effects based on outcome measurement in the field of neuropsychological rehabilitation as our starting point. Since many well-established, well-received and cited reviews are available in our field, we decided to extract the highest quality studies from those reviews. We considered the following categories: cognitive rehabilitation, both single domain (i.e., memory rehabilitation) and multi-domain (i.e., comprehensive neuropsychological rehabilitation), rehabilitation of emotional consequences (i.e., depression and anxiety) and rehabilitation of behavioural problems (i.e., aggression). For most of these categories, the highest quality studies were Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs). If available, those were eligible for our review. In the category multi-domain cognitive rehabilitation, no RCTs are performed yet and the highest level of evidence with corresponding designs were taken into account in this category. This was not our decision but followed from the available reviews.

Information sources and search. Our search was conducted in August 2015. First, reviews were considered in the field of cognitive rehabilitation and comprehensive neuropsychological rehabilitation for patients with acquired brain injury such as stroke and traumatic brain injury (i.e., Cicerone et al., Citation2000, Citation2005, Citation2011). We also included the recommendations from an international team of researchers and clinicians known as INCOG for management of cognition following traumatic brain injury. From the INCOG papers, we extracted the RCTs on which the recommendations for cognitive rehabilitation in the areas of memory, attention, executive functions and self-awareness and aphasia were based. We considered the most common cognitive domains: memory, attention, language/communication, executive functions, neglect, perception, apraxia and awareness. Next, we searched the Cochrane library using the search terms stroke and (traumatic) brain injury which led to additional reviews in the field of aphasia, depression and anxiety. Additionally, we searched Pubmed with the search term “neuropsychological rehabilitation” using the filter “reviews” which led to additional reviews in the field of awareness, computer-based cognitive rehabilitation and behavioural interventions.

Study selection. The first and last author of this paper (CvH, IW) selected the reviews. The list of selected reviews was presented to the special interest group on neuropsychological rehabilitation of the World Federation for NeuroRehabilitation (WFNR SIG-NR) executive committee leading to the inclusion of additional reviews. We excluded one meta-analysis (Elliot & Parente, Citation2014) because the papers underlying this review were difficult to retrieve and mainly based on other reviews already considered.

Data collection process. We made an excel file of all RCTs presented in the selected reviews and removed duplicates as well as studies older than 1995. If a Cochrane review contained an ongoing study, we searched whether the study had been published meanwhile and included the most recent publication. In the field of comprehensive neuropsychological rehabilitation (Geurtsen, van Heugten, Martina, & Geurts, Citation2010) we also included designs other than RCTs because the evidence in this field is still weak and hardly any RCTs have been conducted. For each study included in the final list, we extracted all outcome measures used.

Synthesis of results. We translated the excel file into two lists of outcome measures (neuropsychological tests and other measures) categorized according to domain. For the categorization we used Lezak et al. (Citation2012) for neuropsychological tests measuring cognitive functioning. If a test was not presented in Lezak, we followed the author’s own categorization. We used Tate (Citation2010) for the categorization of the other domains arranged using the framework of the International Classification of Functioning (ICF; WHO, Citation2001).

Results

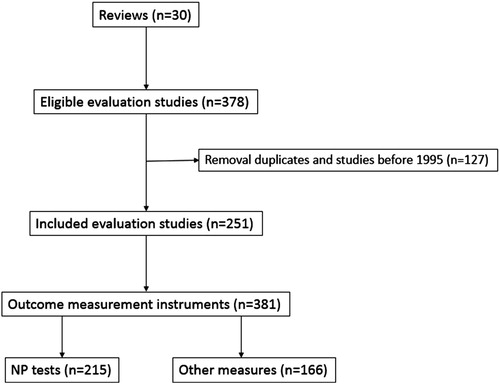

Our search led to a total of 30 reviews in which studies on the effectiveness of neuropsychological rehabilitation were discussed. Reviews were found in the following domains: memory (n = 4), attention (n = 2), executive functioning (n = 3), neglect (n = 2), perception (n = 1), apraxia (n = 1), aphasia (n = 2), awareness (n = 4), multi-domain (n = 3), emotional functioning (n = 7) and behavioural functioning (n = 1). The references of these reviews are presented in Appendix. In we present a flow diagram of the search and selection process.

In total 215 neuropsychological tests were used in outcome studies () and 166 other outcome measures (). The detailed excel tables in which the references are added for each instrument can be obtained from the first author upon request.

Table 1. Neuropsychological tests categorized according to Lezak et al. (Citation2012).

Table 2. Other outcome measures categorized according to Tate (Citation2010) following the ICF framework.

As can be seen in , the number of neuropsychological tests is large. Many instruments were used in only one RCT. Instruments which have been used in five or more studies are: digit span, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task (PASAT), Stroop test, digit symbol test, Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), Trail Making Test (TMT), letter cancellation test, Behavioural Inattention Test (BIT), line bisection, star cancellation, Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test (RBMT),California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT), Western Aphasia Battery (WAB), Communication Abilities in Daily Living, the awareness of social interference test (TASIT), Psycholinguistic Assessments of Language Processing in Aphasia, the communicative effectiveness index (CETI), Amsterdam-Nijmegen Everyday Language Test, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST), (modified) six elements test, Color-Word Interference Test, Behavioural Assessment of the Dysexecutive Syndrome (BADS), and the DysExecutive Questionnaire (DEX). Outcome measurement with neuropsychological tests was most often performed in the domains of working memory, reaction times, visual attention/neglect and aphasia.

In the other instruments are presented. Although the number of instruments in this category is somewhat lower, it is still very high and also in this category some instruments are only used once. Instruments used in five studies or more are only a few: Awareness Questionnaire, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE), Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI), Scandinavian Stroke Scale (SSS), Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90), Barthel Index, Functional Independence Measure (FIM), Community Integration Questionnaire (CIQ), General Health Questionnaire 28 or 12 (GHQ-28, GHQ-12), Short-form health survey / Medical Outcome Scale (SF-36), Cognitive Failure Questionnaire (CFQ), Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS), and the EuroQOL. Instruments other than neuropsychological tests were most often measures on emotional functioning, on multi-category mental functions, multi-domain measures of activities and participation, multidimensional measures and measures on personal factors.

Discussion

In this overview, outcome measures used in intervention evaluation studies of neuropsychological rehabilitation are gathered. Most measures are found on the level of cognitive functioning, which is in line with the many neuropsychological tests that are available. Many countries have their own preferences and many neuropsychologists have personal favourites. Most common domains, which are often presented in neuropsychological assessment, are also found in outcome assessment. Some more than others, such as working memory, neglect and aphasia, but this is to be expected given that most RCTs are performed in these fields.

The focus of (neuropsychological) rehabilitation, however, is much broader than cognitive functioning in helping patients with brain injuries to achieve their optimum level of physical, psychological, social, and vocational well-being (Wilson, Citation2002). Moreover, most of the evidence on the effectiveness of neuropsychological rehabilitation is found in treatments focusing on compensation or adjustment to cognitive impairments rather than restoring them (i.e., Cicerone et al., Citation2011; Spikman & Fasotti, Citation2017). Repeating the neuropsychological tests after treatment, therefore, may not be the most evident form of outcome measurement.

The British Society for Rehabilitation Medicine (BSRM) and Royal College of Physicians (RCP) in the United Kingdom define rehabilitation as “a process of active change by which a person who has become disabled acquires the knowledge and skills needed for optimal physical, psychological and social function” and in terms of service provision this entails “the use of all means to minimize the impact of disabling conditions and to assist disabled people to achieve their desired level of autonomy and participation in society” (BSRM/RCP National Clinical Guidelines, Citation2003, p. 7). Considering the ICF framework this would mean that the outcome of (neuropsychological) rehabilitation should be measured on the level of activities and participation.

Concerning the other measures, many multi-domain, multi-category and multi-dimensional instruments are used covering many different aspects of human functioning. From efficiency and feasibility point of view this is even to be preferred instead of using separate instruments for each domain.

It is remarkable that this overview resulted in about half of the number of instruments covered by Tate et al. (Citation2013) (381 versus 728). On the one hand more instruments would have been expected because the current overview is not only about traumatic brain injury. On the other hand, neuropsychological rehabilitation is aimed at specific domains of human functioning and not all ICF domains are relevant in our field. In comparison, for instance, many body functions (i.e., sensory functions, pain, neuromusculoskeletal functions, movement-related functions) are not measured as outcomes of neuropsychological rehabilitation, nor is mobility on the level of activities. Most overlap is found on the measurement of mental functions which is to be expected.

Future steps towards a standard set of outcome measures

The tables presented in this paper can be used as a reference guide for future research. There are different ways to choose a core set of instruments from the enormous number of instruments that have been used so far. One could select from those currently used, or the most common ones or most used ones. These are, however, not necessarily the best instruments (Van Heugten, Citation2017). Another or additional criterion for selection could be the quality of the instrument in terms of its psychometric properties. Many different sets of criteria are suggested (i.e., Andresen, Citation2000; Terwee et al., Citation2007), but for outcome measurement one could argue that the instrument should at least have adequate responsiveness, the ability of the instrument to detect clinically relevant changes over time. One could determine the minimally important difference (MID) which represents the smallest change on a patient reported outcome measure that is relevant to patients. For the most commonly used outcome measures we provide references to sources where information on the psychometric properties of these instruments relevant to brain injury can be found. At this stage, it is up to the clinician or researcher to decide which properties are most relevant to their intended use of the instrument. Additionally, the feasibility in clinical practice can be considered in terms of, for instance, the availability of the instrument and the duration of assessment.

We took such an approach in our reviews on assessments instruments to measure awareness deficits after brain injury (Smeets, Ponds, Verhey, & van Heugten, Citation2012) and coping after brain injury (Gregório, Brands, Stapert, Verhey, & van Heugten, Citation2014). In both reviews, we performed a systematic search for instruments and made an inventory of the information, which is available on the psychometric properties and feasibility aspects in the next step. This led to cautious recommendations for future use of only a few instruments on these specific outcome domains. Recommendations are cautious because often information is not available and decisions are difficult to make. If we would take the current list of measures presented in this review and apply a set of quality criteria, there will probably still be too many instruments left to choose from. As a first step, we added a table () with a list of the most commonly used instruments with reference to the ICF domain which they represent and a reference to information on their psychometric properties.

Table 3. Properties of most used instruments.

A future step could then be to seek the opinion of experts and/or adopt Delphi or consensus procedures. An example in which common use, quality criteria and expert opinion were all combined is the European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care (Moniz-Cook et al., Citation2008). Recently, a similar approach was used to recommend outcome instruments for psychosocial research in moderate-to-severe TBI (Honan et al., Citation2017). Especially the latter of the two may provide a good starting point for the minimization of the set of reviewed instrument in neuropsychological rehabilitation in this paper albeit that neuropsychological rehabilitation is not only aimed at TBI patients and psychosocial research may not fully overlap with neuropsychological rehabilitation. To illustrate the partial overlap between neuropsychological rehabilitation and psychosocial functioning, the instruments recommended by Honan et al. (Citation2017) are marked in and ; only 17 of the 59 recommended instruments are used in the studies described here. However, the stepwise procedures for the selection of instruments may be followed.

Limitations

This review does have some limitations. First, we took existing reviews in our field as starting point instead of applying a full search on studies in neuropsychological rehabilitation. However, we expect that we have not missed many studies by incorporating the Cochrane, Cicerone and INCOG reviews. Extracting the search terms from these reviews would most probably lead to the selection of the same evaluation studies, which is why we choose to start from there. Second, these reviews do focus on the most common forms of acquired brain injury (i.e., stroke, TBI) which means that we did not incorporate other forms of brain injury such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS) for which also a Cochrane review on neuropsychological rehabilitation exists (Rosti-Otajärvi & Hämäläinen, Citation2014). Often, however, MS specific outcome measures are used in these studies, which would not be considered for a standard set of outcome measures in neuropsychological rehabilitation. Next, we limited our selection of studies to those performed in the last 20 years. Again, however, we did not miss many studies this way because not much high quality RCTs were published before 1995 as can be seen from the included studies in the Cochrane reviews we selected. Finally, we undertook our search in August 2015 which is already three years ago. We therefore did not include the most recent studies which may have introduced new outcome measures. Since 2015, there are three new Cochrane reviews which are relevant to our field: memory deficits after stroke (das Nair, Cogger, Worthington, & Lincoln, Citation2016), anxiety after stroke (Knapp et al., Citation2017) and aphasia after stroke (Brady, Kelly, Godwin, Enderby, & Campbell, Citation2016). The evidence has increased rapidly in the field of memory rehabilitation: in 2007 two trials including 18 participants were included in the review, while in the latest review 13 trials including 514 participants were taken into account. However, no new instruments were included that we have missed in our overview. Moreover, the authors concluded, among other things, that there was a lack of consistency in the choice of outcome measures which hinders comparison of effects. This means that, although the evidence has increased, there is still a large variation in outcome measures and further step towards consensus on outcome measurement in memory rehabilitation has not been made so far. We therefore expect that our review is sufficiently up to date to draw conclusions about outcome measurement. Finally, we cover many domains in which outcome measurement is established, while emerging domains such as social cognitive functioning are not taken into account yet. Since there have not been many intervention evaluation studies in these emerging fields yet, outcome measures are also not represented either.

Conclusions

In this paper the importance of outcome measurement is emphasized and an overview of instruments used in the past 20 years is presented. Clinicians wanting to evaluate an intervention or researchers setting up an evaluation study can use the overview of commonly used outcome measures to guide their measurement choices. Since the number of outcome measures is too large, the development of a standard set of measures is a necessary next step. In current health care, clinical neuropsychologists are probably better off by suggesting our own preferred instruments than waiting for policy makers, management or governments forcing routine outcome measurements upon them. Suggestions are offered on how to select outcome measures and to come to a core set of outcome measures on the basis of different selection criteria. The overall quality of the instrument can be considered, and the feasibility of the instrument for use in clinical practice or research can be taken into account. Additionally, expert opinion and/or consensus can be sought as has been done successfully in other, related fields of health care.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Andresen, E. M. (2000). Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81(12 Suppl 2), S15–S20. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.20619

- Bech, P. (2015). The responsiveness of the different versions of the Hamilton depression scale. World Psychiatry, 14, 309–310. doi: 10.1002/wps.20248

- Bech, P., Bille, J., Møller, S. B., Hellström, L. C., & Østergaard, S. D. (2014). Psychometric validation of the Hopkins symptom checklist (SCL-90) subscales for depression, anxiety, and interpersonal sensitivity. Journal of Affective Disorders, 160, 98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.005

- Bouwens, S., van Heugten, C. M., & Verhey, F. (2009). The practical use of goal attainment scaling for people with acquired brain injury who receive cognitive rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation, 23(4), 310–320. doi: 10.1177/0269215508101744

- Brady, M. C., Kelly, H., Godwin, J., Enderby, P., & Campbell, P. (2016, June 1). Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, CD000425.

- British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine and Royal College of Physicians National Clinical Guidelines. (2003). p. 7.

- Burton, L. J., & Tyson, S. (2015). Screening for mood disorders after stroke: A systematic review of psychometric properties and clinical utility. Psychological Medicine, 45(1), 29–49. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714000336

- Carrozzino, D., Morberg, B. M., Siri, C., Pezzoli, G., & Bech, P. (2018). Evaluating psychiatric symptoms in Parkinson's disease by a clinimetric analysis of the Hopkins symptom checklist (SCL-90-R). Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 2(81), 131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.10.024

- Casaletto, K. B., & Heaton, R. K. (2017). Neuropsychological assessment: Past and future. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 23, 778–790. doi: 10.1017/S1355617717001060

- Cella, D., Lai, J. S., Nowinski, C. J., Victorson, D., Peterman, A., Miller, D., … Moy, C. (2012). Neuro-QOL: Brief measures of health-related quality of life for clinical research in neurology. Neurology, 78(23), 1860–1867. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318258f744

- Cicerone, K. D., Dahlberg, C., Kalmar, K., Langenbahn, D. M., Malec, J. F., Bergquist, T. F., … Morse, P. A. (2000). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Recommendations for clinical practice. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 81, 1596–1615. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2000.19240

- Cicerone, K. D., Dahlberg, C., Malec, J. F., Langenbahn, D. M., Felicetti, T., Kneipp, S., … Catanese, J. (2005). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 1998 through 2002. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 86, 1681–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2005.03.024

- Cicerone, K. D., Langenbahn, D. M., Braden, C., Malec, J. F., Kalmar, K., Fraas, M., … Ashman, T. (2011). Evidence-based cognitive rehabilitation: Updated review of the literature from 2003 through 2008. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 92, 519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.11.015

- das Nair, R., Cogger, H., Worthington, E., & Lincoln, N. B. (2016, September 1). Cognitive rehabilitation for memory deficits after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, CD002293. [Epub ahead of print] Review.

- Elliot, F., & Parente, M. (2014). Efficacy of memory rehabilitation therapy: A meta-analysis of TBI and stroke cognitive rehabilitation literature. Brain Injury, 28(12), 1610–1616. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2014.934921

- Gershon, R. C., Lai, J. S., Bode, R., Choi, S., Moy, C., Bleck, T., … , Cella, D. (2012). Neuro-QOL: Quality of life item banks for adults with neurological disorders: Item development and calibrations based upon clinical and general population testing. Quality of Life Research., 21(3), 475–486. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9958-8

- Geurtsen, G. J., van Heugten, C. M., Martina, J. D., & Geurts, A. C. H. (2010). Comprehensive rehabilitation programmes in the chronic phase after severe brain injury: A systematic review. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 42, 97–110. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0508

- Graetz, B. (1991). Multidimensional properties of the general health questionnaire. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 26, 132–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00782952

- Grant, M., & Ponsford, J. (2014). Goal attainment scaling in brain injury rehabilitation: Strengths, limitations and recommendations for future applications. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24(5), 661–677. doi: 10.1080/09602011.2014.901228

- Gregório, G. W., Brands, I., Stapert, S., Verhey, F. R., & van Heugten, C. M. (2014). Assessments of coping after acquired brain injury: A systematic review of instrument conceptualization, feasibility, and psychometric properties. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 29(3), E30–E42. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31828f93db

- Haigh, R., Tennant, A., Biering-Sørensen, F., Grimby, G., Marincek, C., Phillips, S., … Thonnard, J. L. (2001). The use of outcome measures in physical medicine and rehabilitation within Europe. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 33(6), 273–278. doi: 10.1080/165019701753236464

- Honan, C. A., McDonald, S., Tate, R., Ownsworth, T., Togher, L., Fleming, J., … Ponsford, J. (2017, July 2). Outcome instruments in moderate-to-severe adult traumatic brain injury: Recommendations for use in psychosocial research. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 1–21. [Epub ahead of print ].

- Khan, A., Khan, S. R., Shankles, E. B., & Polissar, N. L. (2002). Relative sensitivity of the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale, the Hamilton depression rating scale and the clinical global impressions rating scale in antidepressant clinical trials. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 17(6), 281–285. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200211000-00003

- Knapp, P., Campbell Burton, C. A., Holmes, J., Murray, J., Gillespie, D., Lightbody, C. E., … Lewis, S. R. (2017, May 23). Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 5, CD008860.

- Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B., Bigler, E. D., & Tranel, D. (2012). Neuropsychological assessment (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lindenstrøm, E., Boysen, G., Christiansen, L. W., Hansen, B. R., & Nielson, P. W. (1991). Reliability of scandinavian neurological stroke scale. Cerebrovascular Diseases, 1, 103–107. doi: 10.1159/000108825

- Moniz-Cook, E., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Woods, R., Verhey, F., Chattat, R., De Vugt, M., … Orrell, M. (2008). A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging & Mental Health, 12(1), 14–29. doi: 10.1080/13607860801919850

- Polinder, S., Haagsma, J. A., Bonsel, G., Essink-Bot, M. L., Toet, H., & van Beeck, E. F. (2010). The measurement of long-term health-related quality of life after injury: Comparison of EQ-5D and the health utilities index. Injury Prevention, 16(3), 147–153. doi: 10.1136/ip.2009.022418

- Polinder, S., Haagsma, J. A., van Klaveren, D., Steyerberg, E. W., & van Beeck, E. F. (2015). Health-related quality of life after TBI: A systematic review of study design, instruments, measurement properties, and outcome. Population Health Metrics, 13, 4. doi: 10.1186/s12963-015-0037-1

- Rosti-Otajärvi, E. M., & Hämäläinen, P. I. (2014, February 11). Neuropsychological rehabilitation for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2, CD009131.

- Salinas, J., Sprinkhuizen, S. M., Ackerson, T., Bernhardt, J., Davie, C., George, M. G., … Schwamm, L. H. (2016). An international standard set of patient-centered outcome measures after stroke. Stroke, 47, 180–186. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.010898

- Smeets, S. M., Ponds, R. W., Verhey, F. R., & van Heugten, C. M. (2012). Psychometric properties and feasibility of instruments used to assess awareness of deficits after acquired brain injury: A systematic review. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 27(6), 433–442. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182242f98

- Spikman, J. M., & Fasotti, L. (2017). Recovery cand treatment. In R. Kessles, P. Eling, R. Ponds, K. Spikman, & M. van Zandvoort (Eds.), Clinical neuropsychology (pp. 113–133). Amsterdam: Boom Publishers.

- Tate, R. L. (2010). A compendium of tests, scales and questionnaires. Hove: Taylor & Francis.

- Tate, R. L. (2014). Measuring outcomes using the ICF with special reference to participation and environmental factors. In H. S. Levin, D. H. K. Shum, & R. C. K. Chan (Eds.), Undersatnding traumatic brain injury (pp. 163–189). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tate, R. L., Godbee, K., & Sigmundsdottir, L. (2013). A systematic review of assessment tools for adults used in traumatic brain injury research and their relationship to the ICF. NeuroRehabilitation, 32(4), 729–750. doi: 10.3233/NRE-130898

- Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. M., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. M., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., … de Vet, H. C. W. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60, 34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

- Timmerby, N., Andersen, J. H., Søndergaard, S., Østergaard, S. D., & Bech, P. (2017). A systematic review of the clinimetric properties of the 6-item version of the Hamilton depression rating scale (HAM-D6). Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86(3), 141–149. doi: 10.1159/000457131

- van der Putten, J. J., Hobart, J. C., Freeman, J. A., & Thompson, A. J. (1999). Measuring change in disability after inpatient rehabilitation: Comparison of the responsiveness of the barthel index and the functional independence measure. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 66(4), 480–484. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.4.480

- Van Heugten, C. M. (2017). Outcome measures. In B. A. Wilson, J. Winegardner, C. M. van Heugten, & T. Ownsworth (Eds.), Neuropsychological rehabilitation. The international handbook (pp. 537–546). Oxford: Routledge Raylor & Francis group.

- Van Heugten, C., Walton, L., & Hentschel, U. (2015). Can we forget the mini-mental state examination? A systematic review of the validity of cognitive screening instruments within one month after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation, 29(7), 694–704. doi: 10.1177/0269215514553012

- Wilde, E. A., Whiteneck, G. G., Bogner, J., Bushnik, T., Cifu, D. X., Dikmen, S., … von Steinbuechel, N. (2010). Recommendations for the use of common outcome measures in traumatic brain injury research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 91(11), 1650–1660.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.06.033

- Wilson, B. A. (1997). Cognitive rehabilitation: How it is and how it might be. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 3, 487–496. doi: 10.1017/S1355617797004876

- Wilson, B. A. (2002). Cognitive rehabilitation in the 21st century. Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair, 16(2), 207–210. doi: 10.1177/08839002016002002

- World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: Author.

Appendix. Selected reviews

Cognitive functioning, domain-specific

Cognitive functioning, multi-domain

Cha and Kim; Effect of computer-based cognitive rehabilitation for people with stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis; Neurorehabilitation 2013: 32;359–368.

Heugten CM van, Wolters Gregorio G, Wade DT. Evidence Based Cognitive Rehabilitation after acquired brain injury: systematic review of content of treatment. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation 2012: 22(5): 653–73.

Geurtsen GJ, Heugten CM van, Martina JD, Geurts ACH. Comprehensive rehabilitation programmes in the chronic phased after brain injury: a systematic review. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 2010; 42(2): 97–110.

Emotions: non-pharmacological treatment

Anger WH, Jr. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare. 2012;10(1):82–3.

Campbell Burton CA, Holmes J, Murray J, Gillespie D, Lightbody CE, Watkins CL, et al. Interventions for treating anxiety after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011(12):CD008860.

Hackett ML, Anderson CS, House A, Xia J. Interventions for treating depression after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008.

Soo, Tate. Psychological treatment for anxiety in people with TBI. Cochrane review 2007.

Stalder-Luthy et al. Effect of psychological interventions on depressive symptoms I long-term rehabilitation after an acquired brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2013;94:1386–97.

Barker-Collo S, Starkey N, Theadom A. Treatment for depression following mild traumatic brain injury in adults: a meta-analysis. Brain Injury 2013; 17(10): 1124–1133.

Fann J, Hart T, SChomer K. Treatment for depression after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 2009; 26(12): 2383–2402.

Behaviour: non-pharmacological treatment

Cattelani R, Zettin M, Zoccolotti P. Rehabilitation treatments for adults with behavioural and psychosocial disorders following acquired brain injury: a systematic review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2010 Mar;20(1):52–85.