ABSTRACT

This study aimed to (1) describe the scope of research related to the Dynamic Comprehensive Model of Awareness (DCMA) (Toglia & Kirk, 2000); (2) identify themes and support for key model postulates; and (3) suggest future research directions related to this model. Using PRISMA scoping guidelines, 366 articles were reviewed, and 54 articles met our inclusion criteria. Selected studies were clustered into three themes: (1) the relationship between general and online self-awareness (50%); (2) interventions based on the model (41%); and (3) factors contributing to self-awareness (9%). Most studies were conducted with participants with acquired brain injury (BI) and traumatic BI (68%), most used a cross-sectional design (50%), and most intervention studies utilized a single-subject design (18%), followed by an experimental design (9%). This review provides evidence for the wide application of the DCMA across varying ages and populations. The need for a multidimensional assessment approach is recognized; however, stronger evidence that supports a uniform assessment of online self-awareness is needed. The intervention studies frequently described the importance of direct experience in developing self-awareness; however, few studies compared how intervention methods to influence general versus online self-awareness, or how cognitive capacity, self-efficacy, psychological factors, and context, influence the development of self-awareness.

Introduction

Self-awareness, the ability to understand one’s strengths and limitations as well as to monitor, recognize and evaluate performance errors is crucial to everyday functioning, participation, and rehabilitation outcomes. In clinical populations decreased self-awareness presents a major challenge to rehabilitation and is associated with motivation, functional outcome, caregiver burden, and psychosocial outcomes (Chesnel et al., Citation2018; Engel et al., Citation2019; Geytenbeek et al., Citation2017; Medley & Powell, Citation2010; Toglia & Foster, Citation2021). Yet, up to 20 years ago, the field of rehabilitation lacked a comprehensive theoretical framework of self-awareness.

The Dynamic Comprehensive Model of Awareness (DCMA), (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000) was developed in an attempt to fill this void by characterizing the multidimensional nature of self-awareness and guiding the development of rehabilitation assessment tools and interventions. The DCMA integrates parallel themes from cognitive psychology, social psychology, and neuropsychology. It proposes a dynamic relationship between knowledge, beliefs, task demands, personal factors, cognitive skills, and the context of a situation.

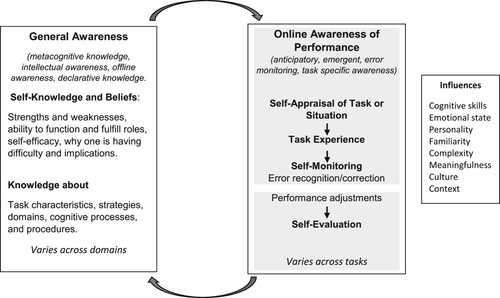

The DCMA expands upon components introduced by the Pyramid model of awareness (intellectual, emergent, and anticipatory awareness) (Crosson et al., Citation1989) and highlights the distinction between two main subtypes of self-awareness: Metacognitive knowledge (aka. general awareness), and beliefs that exist outside the context of a task or situation (i.e., offline) or that which is activated within the context of an activity or situation (i.e., online awareness) (emergent and anticipatory awareness based on the Pyramid model). illustrates this particular aspect of the DCMA and includes other terms that are used interchangeably in the literature to refer to these two aspects of awareness. The full model is included in Supplementary file 1.

Figure 1. General vs. online awareness.

The DCMA argues that general and online awareness is distinct from each other. For example, a person may acknowledge difficulties in activities of daily living (ADL) during an interview yet be unable to use this knowledge about their difficulties to monitor performance while actually performing ADL and vice versa. Furthermore, the DCMA postulates that self-awareness can vary within and across domains (e.g., cognitive, behavioural, social, and functional), depth or level of awareness, and can be influenced by cognitive, task, contextual, personal, and psychological variables. This suggests that self-awareness deficits may be observed in some tasks or situations and not in others. It also implies that self-awareness deficits can be expressed differently in two clients with similar cognitive profiles depending on psychological, task or contextual variables.

Based on these concepts, the DCMA recommended a multidimensional assessment of awareness that examines components of self-awareness across domains, tasks, and levels of specificity. The importance of developing and using online measures that examine self-awareness before, during (at-the-moment error recognition and correction), and immediately after task experiences was emphasized.

The DCMA model describes how general and online awareness affect each other reciprocally in a dynamic relationship. This relationship provides implications for treatment because it explains how self-awareness can change through experience with tasks and describes the mechanism of change. General self-awareness (i.e., pre-existing knowledge and beliefs) is relatively stable and changes slowly through experiences of repeated difficulties and successes across time, while online awareness is variable and is highly dependent on task characteristics, meaningfulness, mood, personality, and other factors (illustrated in ). Repeated discrepancies between self-appraisal, expectations, and actual task performance outcomes modify one’s online self-awareness that in turn updates and restructures general self-awareness leading to performance adjustments. Inability to update knowledge based on task experiences decreases effective strategy use and can lower self-efficacy or perceived sense of control that can shake one’s sense of self. The DCMA model, therefore, suggests that online self-awareness may be more responsive to the immediate effects of intervention and emphasizes the interplay of self-efficacy and other factors (cognitive, task, contextual, personal, and psychological) with online and general self-awareness.

The DCMA model also draws upon Bandura’s concept of “guided mastery” (Bandura, Citation2019) and suggests that treatment should be based on guided questions and structured familiar activity experiences to allow the person to discover errors themselves (i.e., self-discovery). Familiar and meaningful tasks are likely to be more effective in facilitating self-awareness because they provide a basis for evaluating and comparing current experiences.

Overall, there are no reviews that have synthesized knowledge based on the DCMA with the aim of identifying major gaps in evidence. Therefore, the main aim of this scoping review was to identify key evidence and gaps and suggest future research needs related to the DCMA. Such scoping review can provide initial evidence related to the conceptualization of self-awareness, which will inform assessment and treatment. This scoping review examines the influence of the DCMA model in research, including the scope of application, how it has been studied and incorporated into clinical assessment and treatment since its publication. Thus the questions that we aimed to answer while conducting this scoping review were: (1) What is the evidence to support the DCMA key themes and what populations have been included? (2) What is the evidence to support the application of DCMA concepts to assessment and treatment? (3) What are the gaps in research and what should be done in future studies to further support the model?

Methods

Scoping reviews are utilized to map an area of study and to determine the need for more studies by helping to identify important evidence gaps and provide a clear indication of the volume of literature and studies available (Mendelsohn et al., Citation2015). The scoping review used in this research followed the PRISMA guidelines and the steps outlined in Levac et al. (Citation2010). First, we identified the aim and the questions of this scoping review; second, using Google Scholar, PsychInfo, PubMed, and CINAHL we identified relevant studies that cited the DCMA from 2000 through June 2021; third, we selected studies for this review based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed below; and, finally, we extracted and tabulated the data. The scope of this inquiry was to identify the current findings related to the DCMA model and areas for future research, with an intended outcome of advancing research and practice of self-awareness within the field of rehabilitation.

Search and selection

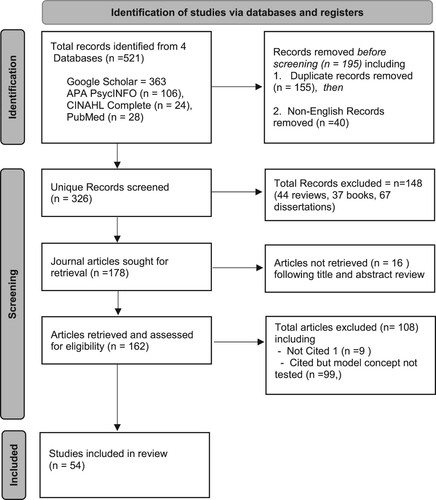

The full search strategy was carried out in five main steps which are also illustrated in :

An initial search in Google scholar using the phrase: “cited by Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000” OR “Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000” AND “self-awareness” OR “awareness” OR “model of self-awareness” OR “DCMA” OR “DCMA model” resulted in 521 records.

This initial search results were downloaded into excel and duplicates were removed electronically. We then inspected and excluded the non-English records leaving a total of 326 records.

Abstract were reviewed in two stages: first, review articles, dissertations, and books or book chapters were excluded. Second, articles that involved surveys of clinicians, treatment protocols, and topics that were completely not related to self-awareness were removed. This review yielded a total of 162 articles

Each article was then reviewed for relevancy by considering how well each paper matched and referred to themes and concepts introduced by the DCMA. We opted to exclude articles that did not directly include the DCMA model in their methods, results, and/or discussion, but only mentioned the model as a reference for the definition of self-awareness. Thus, the manuscript that just cited the model without referring to concepts described by the model were excluded; in addition, articles that did not cite the model or the paper describing the model were also excluded.

Finally the review included total 54 articles that went through a thematic analysis

Figure 2. Prisma flow chart illustrating the screening and selection of articles.

We reviewed each study at the full-text review stage for distinctions between intervention studies and relationships between main model constructs; any study that incorporated these elements in relation to the DCMA was included. One of two reviewers (JT or YG) made exclusion decisions. Those studies for which exclusion criteria were inconclusive were noted and discussed until a final decision was made. The references-cited list of all included articles identified within the original search was checked for additional relevant citations.

Procedure

The procedure used in this scoping review was a Framework synthesis using a deductive approach (Dixon-Woods, Citation2011): With this approach, a tentative framework of themes was identified based on the DCMA model. Three main themes were examined in the scoping are (1) General awareness (metacognitive knowledge) and online self-awareness: (1.1) Differences between general and online awareness (1.2) Assessment of online awareness (1.3) Variations of self-awareness across domains and tasks; and (2) Treatment based on the DMCA: (2.1) Effectiveness of familiar or meaningful tasks in improving self-awareness; (2.2) Self-discovery of errors and types of feedback; (2.3) Relationship of strategy use to online awareness. The last theme explored (3) Factors that influence self-awareness.

Using the predefined framework, the reviewers (YG and JT) actively searched for data to support the themes identified. One researcher assigned each study to a primary theme within this framework. As coding progressed, some themes were combined or deleted or new themes were added; previously coded studies were reassessed within the updated framework.

Then, one researcher (YG) assigned primary themes to each study, and the second researcher (JT) validated them. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved. Where appropriate, studies were assigned primary and secondary themes; however, studies were grouped according to the primary theme. Each study was also described according to study aim/s, methodology, population, and key results (See ).

Table 1. Summary of articles included within the scoping review of the DCMA.

Results

The search yielded a total of 366 articles, 54 of which were included in this review. ( describes the exclusion process). These were clustered according to three primary themes: (1) relationship between general and online self-awareness (n = 27); (2) research studies related to interventions (n = 22); and (3) factors influencing self-awareness (n = 5). It should be noted that some studies could be categorized under more than one theme (indicated in ).

Theme 1. General awareness (metacognitive knowledge) and online self-awareness

Twenty-seven studies examine directly and indirectly the difference and the relationship between metacognitive knowledge, that is, knowledge of task characteristics and knowledge of one’s own capabilities and online self-awareness. The majority of the studies in this theme utilized a cross-sectional design. Only two studies utilized a longitudinal design.

Most studies in this theme consisted of samples of persons with traumatic brain injury (TBI) (n = 9; including two studies with children with TBI), dementia (n = 4), and acquired brain injury (ABI) (n = 4). Two of the studies (within the ABI and dementia sample) were done with participants with aphasia. Additionally, studies were done with adults with Huntington disease (n = 1), bipolar disorder (n = 2), multiple sclerosis (n = 3), and persons with HIV (n = 1), as well as middle-school children (n = 1) and healthy adults (n = 2).

Three subthemes were identified within this main theme: (1.1) the difference and relationship between general and online self-awareness; (1.2) Assessment of online awareness; and (1.3) Variations of self-awareness across domains and tasks.

1.1 Distinction between general and online self-awareness

The model “clearly differentiates between knowledge and beliefs related to one’s self that are pre-existing or stored within long-term memory and knowledge and awareness that is activated during a task”. (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 59)

This theme was assigned to any study that measured both general self-awareness and online self-awareness. The theme included 13 studies describing the distinction and the relationship between online self-awareness and general self-awareness (AKA metacognitive knowledge or general awareness). describes the different self-awareness components assessed in the studies reviewed. Only three studies assessed all components of online awareness (before, during, and following task performance), four studies used functional tasks to assess online self-awareness; six studies assessed general and anticipatory self-awareness (before task), and six studies assessed general self-awareness and error monitoring (during task performance).

Table 2. Studies examining different components of self-awareness.

The method used to assess general self-awareness was quite unified. Most studies used a discrepancy score between self and informant ratings or a self-rating of one’s own intellectual, emergent, and anticipatory self-awareness during a semi-structured interview. The method used to assess online awareness, on the other hand, was less unified. Studies differed in the components of online awareness assessed, the rating format, specificity of ratings, type and number of tasks used, and scoring methods For example, some studies used verbal reports to mark the number of recognized or corrected errors in a laboratory-based task (e.g., Dockree et al., Citation2015) while other studies used self-evaluation immediately after a series of functional tasks which were compared to actual performance (e.g., O’keeffe et al., Citation2007). The variations in online assessment methods are further summarized in .

Table 3. Online awareness methods: Examples of variations in online assessment methods.

Results indicated that some sample populations showed greater impairment in general self-awareness (MS, bipolar) (Chen & Goverover, Citation2021; Goverover et al., Citation2014; Torres et al., Citation2016), while persons with dementia, TBI, stroke (including neglect) and Huntington’s disease appeared to have more impairment in online self-awareness than in general self-awareness (Chen & Toglia, Citation2019; Hoerold et al., Citation2013; O’Keeffe et al., Citation2007).

Studies did not demonstrate consistent results regarding the association between general and online self-awareness. Some studies showed that online and general self-awareness were not correlated linearly. For example, O’Keeffe et al. (Citation2007) investigated the relationship between online and general self-awareness in persons with TBI. They found that metacognitive knowledge did not correlate with emergent and anticipatory self-awareness. Similar findings were demonstrated in persons with bipolar disorder (Torres et al., Citation2016), Huntington’s disease (Hergert et al., Citation2020), frontal lesions (Hoerold et al., Citation2013), and aphasia (Dean et al., Citation2017). In contrast, Dockree et al. (Citation2015) found a positive relationship between metacognitive knowledge (over-estimation of daily life) and emergent self-awareness of errors during laboratory tasks. Lahav et al. (Citation2014) also found a positive correlation between self-knowledge and online self-awareness, while online self-awareness was more closely associated with actual performance. Lastly, a study comparing general and online self-awareness in HIV found that general self-awareness was more significantly associated with task performance than was online self-awareness (Fazeli et al., Citation2017). However, in this study, general self-awareness included assessment of prediction accuracy of performance. Prediction accuracy has been used as an indicator of online awareness in other studies (Casaletto et al., Citation2016; Fazeli et al., Citation2017; Quiles et al., Citation2020).

1.2 Assessment of online self-awareness

Measures that characterize awareness by an overall score do not consider the multidimensionality of awareness and, therefore, are too broad to be useful. Assessment of awareness needs to include systematic methods for examining perception of abilities within the context of a task or situation … . The proposed model also implies that assessment of awareness should include both global and specific estimation measures across different tasks and levels of difficulty. (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 68)

Four studies specifically examined the use of clinical assessment tools that were developed based on the DCMA. The first study (Bivona et al., Citation2020) proposed a new clinical tool to assess self-awareness at its various levels based on the DCMA. They examined the validity of the Self-Awareness Multi-Level Assessment Scale (SAMAS) to assess impairment of self-awareness after severe acquired brain injury. The authors found that SAMAS allows the assessment of emergent and anticipatory self-awareness, as long as it is completed within the context of accurate clinical observation.

The second study (Doig, et al., Citation2017a), examined a new task analytic approach to assessing online self-awareness involving observation and classification of errors during meaningful activities (e.g., cooking, drink-making, organization of time, budgeting, and use of an iPad application). The authors concluded that the assessment was feasible and provided important information about error behaviour and correction; however, since it requires a time investment in training and planning, it would be best suited to be performed in clinical practice by occupational therapists.

The third study (Krasny-Pacini et al., Citation2015) examined the feasibility of three ways of assessing self-awareness of executive dysfunction in children with TBI during a rehabilitation programme, based on goal management training. Their study also called for the assessment of both online and metacognitive knowledge when assessing self-awareness. Importantly, they point to relevant ways to use specific stimuli when evaluating children’s self-awareness suggesting using stories to assess intellectual self-awareness and real cooking tasks to assess online self-awareness.

An additional study (Plutino et al., Citation2020) provided evidence of the need to assess online self-awareness during evaluation. In that study, an online self-awareness assessment differentiated between groups of patients with dementia above and beyond executive function. It concluded that online self-awareness error monitoring was the only measure to differentiate between groups. summarizes the methods used to measure online awareness across research studies.

1.3. Variations of self-awareness across domains and tasks: online self-awareness varies across tasks and contexts and general self-awareness varies across domains

Online awareness or ongoing monitoring and regulation of actual performance varies with the task and the context of a situation and is relatively unstable. However, because online awareness is dependent on the task and the situation, this framework implies that anticipatory and/or emergent awareness may be evident on some tasks and situations but not on others. (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 59)

Self-monitoring skills may be highly dependent on task characteristics, such as familiarity and difficulty level (p. 62). Self-awareness can differ in various areas of function: physical, cognitive, perceptual, interpersonal, emotional and functional domains. Thus, individuals may exhibit blind spots’and may be aware of some areas and not others (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 60).

Ten articles were clustered within this theme. Of the six articles that only assessed general self-awareness, five demonstrated that metacognitive or general self-awareness varies across domains (Banks & Weintraub, Citation2008; Goverover et al., Citation2009; Hurst et al., Citation2020; Lloyd et al., Citation2021; Schoo et al., Citation2013; Torres et al., Citation2021). For example, Hurst et al. (Citation2020), showed that participants with TBI displayed significantly poorer self-awareness in the activities of daily living (ADLs) domain than in the interpersonal and emotional domains. Goverover et al. (Citation2009) found that among persons with MS, self-awareness of problem-solving and task performance was lower than self-awareness of social interaction. Schoo et al. (Citation2013) found that self-awareness for the visuoperception domain was significantly worse than for the memory domain. Only Hurst et al. (Citation2020) provided limited support for domain-specific deficits in general self-awareness. Nagele et al. (Citation2021) assessed both general and online self-awareness. Similar to Hurst et al, they also found no difference in general self-awareness between domains, but they did find that online self-awareness distribution (measured by a visual analogue) varied robustly from the memory composite domain to executive function. They concluded that when assessing self-awareness, measures should assess both general and online self-awareness.

Three studies examined online self-awareness across tasks and contexts. Rotenberg-Shpigelman et al. (Citation2014) found that anticipatory and emergent self-awareness were significantly more impaired in the instrumental ADL (IADL) tasks compared to basic ADL tasks. Quiles et al. (Citation2020) noted that online self-awareness was different for memory tasks in comparison to social cognitive tasks. Lastly, Doig, Fleming, and Lin (Citation2017a) compared online self-awareness and error behaviour during tasks of meaning and importance in participants with TBI. They found that error behaviours (i.e., frequency of errors, the ability to self-correct errors, and the types of errors made) may vary according to the nature and complexity of the activity and its relevance to the individual. In addition, error behaviour varied according to the characteristics of the task being performed.

Theme 2. Studies supporting treatment based on the DMCA

Studies focusing directly or indirectly on improving self-awareness were assigned the intervention or treatment theme. We distinguished between treatment studies designed to directly improve awareness versus those that support awareness treatment concepts but did not directly attempt to improve awareness. From the 22 studies reviewed in this cluster, 16 studies intended to improve awareness directly. These studies are presented in each section relevant to the theme.

Most of the studies in this theme utilized a single subject design (n = 7) to assess treatment efficacy, five studies utilized experimental design, and the rest used qualitative or mixed design (n = 3), cross-sectional and secondary analysis (n = 3), and quasi-experiment (n = 2).

Twenty studies in this theme were done with persons with TBI and ABI (primarily stroke; one study focused on people with ABI and unilateral neglect); one study was with adolescents with ADHD; another was with community-dwelling older adults.

Studies related to treatment based on the DMCA were clustred into three subthemes (2.1) Efficacy of familiar or meaningful tasks in improving self-awareness used familiar, occupation-based, or functional tasks to improve self-awareness, (2.2) intervention that emphasized self-discovery of errors or type of feedback, and (2.3) Studies that examined the relationship between strategy use and online awareness.

2.1. Efficacy of familiar or meaningful tasks in improving self-awareness

Familiar tasks may be more effective in facilitating awareness than remedial or unfamiliar tasks because they provide a basis for evaluating current experiences. Familiar tasks should be simplified and structured (feedback) so that they match the individual’s information processing abilities. (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 65)

From the 12 studies reviewed, one used RCT, six utilized single-subject designs, one utilized data from a previous RCT to conduct a secondary analysis, one used a cross-sectional design, one used a case report, and two used qualitative methodology to provide more information on the development of self-awareness following brain injury. Studies in this theme were done with samples of persons with TBI and ABI. Each of the studies presented a unique approach or support for treatment to improve self-awareness, but the common theme of these studies was the use of familiar functional, occupation-based tasks to improve self-awareness.Footnote1

From these 12 studies, nine were designed specifically to improve self-awareness and therefore were classified as direct studies and are listed in . For example, Fleming et al. (Citation2006) and Fleming et al. (Citation2020) provided initial support for the use of familiar occupation-based tasks in facilitating participants’ online and general self-awareness. Thus, studies listed under this theme all based their treatment on the performance of functional everyday tasks. Of these, four provided full support and another three provided partial support to the use of functional everyday tasks in improving online self-awareness. As for general self-awareness, two studies provided full support for improvement, four partial support, and three provided no support. The studies listed in , Section 2.1, provide initial support for using familiar, meaningful tasks while providing treatment to directly improve self-awareness. However, it is important to note the numerous variations in type and methods of self-awareness assessment, as seen in and . For example, some studies did not assess online self-awareness (Fleming et al., Citation2006; Miyahara et al., Citation2018), and most studies used a single-subject design to examine the efficacy of the treatments.

Table 4. Studies that support treatment based on the DMCA.

Three studies in this group were not designed directly to improve self-awareness. Two studies (Dirette, Citation2002; O’callaghan et al., Citation2006) explored the process of developing self-awareness. Both studies presented that, in addition to using familiar tasks, participants should be given the chance to “discover” their strengths and limitations while performing familiar tasks. Lastly, Chudoba and Schmitter-Edgecombe (Citation2020) support the use of familiar occupations in improving self-awareness. In fact, they found that people with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) showed intact self-updating while performing functional but not memory tasks, indicating that the ability to self-update knowledge may differ depending on the task.

2.2. Intervention: self-discovery of errors and type of feedback

Awareness training techniques, which are geared towards helping patients self-discover their own errors, may be more effective in enhancing awareness than verbal feedback (p.65). Treatment needs to be directed towards creating structured experiences where individuals can experience and recognize errors themselves and, at the same time, achieve a sense of control and mastery over performance. (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 66)

Seven articles were categorized into this theme that emphasizes how to provide feedback during treatment sessions to improve self-awareness (, Section 2.3). Note that there is some overlap between treatment studies as some presented in the other sections also used a self-discovery approach (Toglia et al., Citation2010). However, some of them were not classified into this theme because they did not fully describe how prompts or questions were provided, or they fit better to another theme.

Kersey et al. (Citation2019) conducted a secondary analysis of data collected from a randomized controlled trial, in which treatment consisted of a performance of activities and identifying barriers to performance. The treatment was based on prompting questions, as well as workbooks to facilitate learning and aid the participants in implementing the strategy. The treatment resulted in improvement of strategy behaviour immediately after treatment for both groups, however, only the treatment group showed continued improvement at six months post-treatment. Toglia and Chen (Citation2020) based the intervention on the DCMA. The therapist provided supportive feedback and semi-structured guidance to promote strategy learning and self-discovery of omission errors. This intervention resulted in improved online awareness. In a cross-sectional study with community-dwelling older adults, Ng et al. (Citation2018) found that metacognitive awareness acquired during the retrospective and prospective memory tasks influenced how older adults’ modified their predictions of subsequent task performance. Thus awareness that emerged from experiential feedback or ongoing task experiences helped to shape predictions of later tasks.

Ownsworth et al. (Citation2008) used predictions, role reversal, and video review interventions to improve self-awareness. Participants preferred and benefited from experimental feedback and from working on tasks that were optimally challenging. FitzGerald et al. (Citation2019) used direct audio-visual feedback consisting of an alerting tone whenever participants made an error. They concluded that while performing a computerized attention task, individuals may become aware of their own errors through experiential feedback that is structured, planned, and supported.

Schmidt et al. (Citation2013) conducted the only study that compared three types of feedback: video combined with verbal, verbal, and experiential. The study demonstrated that multi-modal feedback was superior to solely experiential practice or experiential practice paired with post-task verbal feedback. Furthermore, their study found that video feedback paired with verbal feedback improved both online and intellectual self-awareness.

Richardson et al. (Citation2015) was the only study that was not designed to directly improve self-awareness but instead studied the relationship between the nature of feedback and self-awareness in individuals with TBI through retrospective reports from their informants. Their study supports various types of feedback but emphasizes the value of experimental feedback.

2.3. Relationship of strategy use to online awareness

Accurate task appraisal or judgment of task difficulty level is related to recognition of the need for strategies and self-monitoring. (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 62)

Three studies presented findings related to this category. See , Section 2.4 for a description of these studies. Levanon-Erez et al. (Citation2019) examined a treatment programme using the Cog-Fun treatment to improve functional performance in children with ADHD. The Cog-Fun treatment included structured reflection on occupational experiences and teaching general problem-solving strategies – goal-setting, planning, and self-monitoring. The authors found a positive significant correlation between occupational functioning gains and strategy behaviour and concluded that children with better online self-awareness tended to use strategies and have better occupational performance.

Casaletto et al. (Citation2016) used goal-management methods (stop, define, list/outline, learn/apply, check) while providing feedback on executive function impairment prior to task performance. They found that those with HIV who completed the goal management strategy training had better online self-awareness compared to a control group. Although strategy use was not directly measured, it suggests that those with better online awareness may be effectively applying the strategy learned during the study.

Lastly, van Erp and Steultjens (Citation2020) concluded that lower levels of self-awareness seem to be associated with low motivation to persist and complete the activity. This latter study is not listed in as it was observational and did not report an intervention. Thus, online awareness appears to be important for effective strategy use. However, literature in this area is limited.

All in all, participants were able to benefit from treatment designed to improve self-awareness; more specifically, online self-awareness appeared to be more responsive to treatment than general self-awareness. For example, across all studies described in , there were 13 studies providing support for improvements in online awareness (10 = full and 3 = partial) and 8 studies supporting improvement in general awareness (3 = full, 5 = partial).

Theme 3. Factors that influence self-awareness (e.g., cognitive severity, denial, and self-efficacy)

Although knowledge and understanding of one’s deficits may not be related to severity of cognitive-perceptual deficits, the ability to anticipate, recognize and self-correct errors within the context of current task performance may be related to the severity of cognitive-perceptual deficits. (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 65)

Five studies discussed this theme of the model. Morton and Barker (Citation2010) and Villalobos et al. (Citation2020) found that executive functions are significant contributors to metacognition and self-awareness. These studies emphasize that the ability to anticipate, recognize, and self-correct errors within the context of current task performance may be related to the severity of cognitive-perceptual deficits; furthermore, self-monitoring, which is part of executive function, is crucial for self-awareness. Villalobos et al. (Citation2020) further stressed the role of self-awareness as a mediator between cognitive functions of memory and executive functions.

Other factors can also influence online awareness and self-monitoring abilities such as … , motivation, beliefs, emotional state … … .. (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000, p. 60)

Ownsworth et al. (Citation2007) sorted individuals into four groups according to neuropsychological and psychological factors related to self-awareness deficits and compared emotional and psychosocial adjustment. Interestingly, they found that the group with poor self-awareness and high symptom reporting experienced poorer outcomes than did the highly defensive and self-aware group. In fact, this study differentiates between psychological and neuropsychological self-awareness.

Lastly, Medley et al. (Citation2010) characterized three groups of TBI participants, based on profiles of subjective beliefs about TBI. This study and that of Ownsworth et al. (Citation2007) are unique in that they show the importance of understanding subjective perceptions, coupled with individually tailored rehabilitation tasks to promote mastery, self-efficacy, perceived control, and self-awareness.

Discussion

This scoping review demonstrates that the multidimensional nature of self-awareness highlighted in the DCMA has been well-established over the past 20 years since its initial publication. In this discussion, we present the findings of this scoping review, connect these findings with the main concepts and postulates presented by the DCMA model, and discuss what requires further evidence.

General and online self-awareness

The DCMA distinguishes between general awareness of abilities that are offline or independent of tasks and online self-awareness that is activated within the context of task experiences. The disassociation between general and online self-awareness has been demonstrated across a wide range of clinical populations (e.g., TBI, ABI, MS) and ages (children and adolescents to community-dwelling older adults). Importantly, one study provided evidence for neuroanatomical areas that are responsive to these two types of awareness, further supporting this disassociation (Plutino et al., Citation2020). However, cross-sectional studies investigating both general and online awareness are limited in number and hampered by variations in assessment methodology. Studies comparing general and online awareness frequently used measures that differed in domains of cognition or functional tasks (Robertson & Schmitter-Edgecombe, Citation2015). For example, general self-awareness may have been assessed using questions related to activities of daily living, or social participation while online awareness was measured in relation to a cognitive abstract task (Dockree et al., Citation2015). In this review, only two studies assessed both general and online awareness in relation to the same context, within and outside the context of performance (Chen & Toglia, Citation2019; Lahav et al., Citation2014). If awareness can vary across domains and tasks, it is also important to compare general and online awareness with similar domains or tasks within the same study (Merchán-Baeza et al., Citation2020).

This review suggests that further clarification and consensus is needed about the concepts of general and online self-awareness. For example, some studies included prediction accuracy as a measure of general self-awareness and verbal formulation of a plan as a measure of task appraisal or anticipatory awareness (Fazeli et al., Citation2017). Although it can be argued that prior to a task, individuals use their stored knowledge and beliefs to appraise task difficulty, most studies used prediction accuracy as an online awareness measure. Also, many studies assessed selected components of online awareness such as error recognition, prediction accuracy, or post-performance ratings but did not examine all aspects of online self-awareness (e.g., Chen & Goverover, Citation2021; Dockree et al., Citation2015).

Additional ambiguities and discrepancies were noted in the literature about what constitutes an online self-awareness measure. For example, some authors included the Self-Regulation Strategy Interview (SRSI) as a measure of online self-awareness (e.g., Kersey et al., Citation2019), while others included it as a measure of general self-awareness (Toglia et al., Citation2010). The SRSI is categorized as a measure of general and not online self-awareness because it includes anticipation and error recognition questions outside the context of activities (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000). A person can say all the right things during an interview but fail to assimilate this knowledge during actual task performance. Therefore, the DMCA would not classify an interview outside the context of an activity as being a measure of online self-awareness. Differences found within the results between the SSRI and other self-awareness questionnaires may be related to the specificity, content, and format of the questions (Goverover et al., Citation2007).

These differences observed with both general and online measures of self-awareness add to the confusion within the research literature and make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions about comparisons and relationships between online and general self-awareness.

Need to include online self-awareness within assessment

Despite the variations observed in the literature regarding assessment methodology for online self-awareness, a consensus exists of the importance to measure online self-awareness and incorporate it into everyday clinical evaluation (Bivona et al., Citation2020). The DCMA describes different components of online self-awareness immediately before (anticipation and task appraisal), during (error recognition and correction), and after-task performance (self-evaluation and appraisal) and suggests that these online self-awareness components involve different skills. A few recent papers provide clinical guidelines for assessing some components of online self-awareness (Bivona et al., Citation2020; Doig, Fleming, Ownsworth, et al., Citation2017); however, the investigation of standardized clinical tools that provide a comprehensive assessment of online self-awareness is limited.

Online self-awareness varies across tasks and contexts; general self-awareness varies across domains

The majority of studies reviewed in this paper support that both general and online self-awareness can vary within and across domains. However, cross-sectional research studies that include online self-awareness have primarily used abstract tasks restricted to specific cognitive domains. Further systematic investigation is warranted on online self-awareness across everyday tasks that differ in complexity, perceived importance, or meaningfulness; also needed is an identification of the task conditions under which the individual shows the highest levels of emergent and anticipatory self-awareness.

Studies supporting treatment based on the DMCA

The DCMA inspired occupation-based metacognitive interventions that include experiences with relevant everyday tasks. The majority of intervention studies demonstrate the effectiveness of incorporating familiar tasks into treatment so that the person has a basis for evaluating current abilities (Chudoba & Schmitter-Edgecombe, Citation2020; Doig et al., Citation2021). As Dirette (Citation2002) describes, self-awareness is a slow process in which participants compare current performance to pre-morbid performance on functional tasks. Although a few studies have observed and documented the relationship between strategy use and online self-awareness of performance, more studies are needed to empirically investigate this (Dirette, Citation2002; Nagelkop et al., Citation2021).

Treatments that improve online self-awareness

The DCMA suggests that online self-awareness is less stable than metacognitive knowledge and, therefore, is more susceptible to change. Overall, studies demonstrate that online awareness appears to be more responsive to treatment than general self-awareness. However, treatment varied in terms of dose, method, and frequency, while assessments varied across studies, making it difficult to generalize findings and draw valid conclusions.

The DCMA suggests using training methods that help people self-discover their own errors rather than directly pointing out their errors; however, detailed guidelines for therapists on how to use guided prompts and structure-activity experiences have only recently been published (Toglia & Foster, Citation2021). The literature generally supports the use of feedback (FitzGerald et al., Citation2019) in increasing online self-awareness, specifically, experiential feedback (Ownsworth et al., Citation2008, Citation2010) and systematic feedback (Ownsworth et al., Citation2006); however, direct comparison between types of feedback or between guided methods and direct feedback in enhancing online awareness is needed.

Systematic examination of changes in self-efficacy as a result of intervention is a missing component across the self-awareness intervention literature. The DCMA suggests that self-awareness intervention should involve simultaneously building self-efficacy and a sense of control and mastery over performance as self-awareness emerges. Although self-efficacy is occasionally mentioned within the context of case examples, a greater focus on self-efficacy is needed within intervention studies.

Support for the relationship between executive function and self-awareness exists, but it is unclear whether the severity of executive function deficits differentially impacts general versus online self-awareness or response to treatment. Initial research on the interplay between psychological factors and self-awareness has been conducted by Medley et al. (Citation2010), who explored belief schematas with measures of awareness and coping, and Ownsworth et al. (Citation2007), who examined self-awareness typologies based on neuropsychological and psychological measures, including the level of defensiveness. However, no empirical research focuses on how the interplay of these factors impacts response to treatment. Areas needing more attention include the process of emergence of online and general self-awareness – how they are influenced by personal, psychological, cognitive, and contextual variables, and how they change across treatment and recovery.

Limitations

Only studies citing or referring directly to the DCMA and its main concepts or methodology were included in this review. Many studies were not included that could support some of the postulates because they did not cite the DCMA model directly (i.e., they cited papers that cited the DCMA model). These papers were also not included in this review. Therefore, multiple components that were discussed in the original paper (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000) were not addressed in this scoping review (e.g., implicit self-awareness, depth of self-awareness).

Conclusion

Over the past 20 years, the literature has supported the multi-dimensional and dynamic nature of self-awareness proposed by the DCMA model. Multiple studies identified differences between general and online self-awareness across different diagnostic and age groups. This current review sheds light on the need to understand how general and online self-awareness influence each other and change with repeated experiences and feedback. Additionally, across the studies reviewed, online awareness was a modifiable outcome, however, because of the variation in the operational conceptualization of online awareness, it is hard at this time to draw a definitive conclusion about the assessment, outcome, and intervention related to online awareness.

In the area of treatment, numerous studies demonstrate promise and support for occupation-based interventions or the use of familiar and meaningful task experiences that provide experiential feedback to increase self-awareness, as emphasized in the DCMA model. However, a comparison of treatment methods or activities was not found, and comparison of feedback methods is limited. Additionally, the relationship between online awareness and strategy use requires further study within the treatment context.

The DCMA also discussed the importance of task variables, personality characteristics, self-efficacy, methods of interaction, emotional reactions, and the context of the person’s life (e.g., understanding the client’s personality, values, and way of life). These concepts add complexity to the study of self-awareness and were not addressed in the majority of studies reviewed. A wider focus on how personal and psychosocial factors influence self-awareness is needed (e.g., Ownsworth et al., Citation2007).

Overall, this review highlights the need to think more broadly about patterns of variables that interact and impact the person’s reactions to task challenges or performance difficulties as a foundation for both assessment and treatment. For example, self-awareness may be best understood by creating self-awareness profiles or by simultaneous consideration of self-awareness components with other task and psychological variables as described above, to allow for analysis of patterns across multiple variables. Going forward, greater attention on the interplay and dynamic relationship between areas of self-awareness and key factors (i.e., contextual, personal-psychological, and task variables) influencing aspects of self-awareness is needed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (241 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Carolina Herrera for her assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 In addition, several studies, noted in , Sections 2.2 and 2.3, also used functional and familiar activities for treatment, with positive results, and these studies even though not listed in this section also provide support for the use of functional tasks for self-awareness improvement.

References

- Bandura, A. (2019). Applying theory for human betterment. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(1), 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691618815165

- Banks, S., & Weintraub, S. (2008). Self-awareness and self-monitoring of cognitive and behavioral deficits in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, primary progressive aphasia and probable Alzheimer’s disease. Brain and Cognition, 67(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2007.11.004

- Bivona, U., Ciurli, P., Ferri, G., Fontanelli, T., Lucatello, S., Donvito, T., Villalobos, D., Cellupica, L., Mungiello, F., Lo Sterzo, P., Ferraro, A., Giandotti, E., Lombardi, G., Azicnuda, E., Caltagirone, C., Formisano, R., & Costa, A. (2020). The self-awareness multilevel assessment scale, a new tool for the assessment of self-awareness after severe acquired brain injury: Preliminary findings. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1732. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01732

- Casaletto, K. B., Moore, D. J., Woods, S. P., Umlauf, A., Scott, J. C., & Heaton, R. K. (2016). Abbreviated goal management training shows preliminary evidence as a neurorehabilitation tool for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders among substance users. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 30(1), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2015.1129437

- Chen, M. H., & Goverover, Y. (2021). Self-awareness in multiple sclerosis: Relationships with executive functions and affect. European Journal of Neurology, 28(5), 1627–1635. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14762

- Chen, P., & Toglia, J. (2019). Online and offline awareness deficits: Anosognosia for spatial neglect. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(1), 50–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000207

- Chesnel, C., Jourdan, C., Bayen, E., Ghout, I., Darnoux, E., Azerad, S., Charanton, J., Aegerter, P., Pradat-Diehl, P., Ruet, A., Azouvi, P., & Vallat-Azouvi, C. (2018). Self-awareness four years after severe traumatic brain injury: Discordance between the patient’s and relative’s complaints. Results from the PariS-TBI study. Clinical Rehabilitation, 32(5), 692–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517734294

- Chudoba, L. A., & Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. (2020). Insight into memory and functional abilities in individuals with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 42(8), 822–833. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2020.1817338

- Crosson, B., Barco, P. P., Velozo, C. A., Bolesta, M. M., Cooper, P. V., Werts, D., & Brobeck, T. C. (1989). Awareness and compensation in postacute head injury rehabilitation. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 4(3), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-198909000-00008

- Dean, M. P., Della Sala, S., Beschin, N., & Cocchini, G. (2017). Anosognosia and self-correction of naming errors in aphasia. Aphasiology, 31(7), 725–740. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2016.1239014

- Dirette, D. (2002). The development of awareness and the use of compensatory strategies for cognitive deficits. Brain Injury, 16(10), 861–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050210131902

- Dixon-Woods, M. (2011). Using framework-based synthesis for conducting reviews of qualitative studies. BMC Medicine, 9(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-39

- Dockree, P. M., Tarleton, Y. M., Carton, S., & FitzGerald, M. C. C. (2015). Connecting self-awareness and error-awareness in patients with traumatic brain injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 21(7), 473–482. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617715000594

- Doig, E., Fleming, J., & Lin, B. (2017a). Comparison of online awareness and error behaviour during occupational performance by two individuals with traumatic brain injury and matched controls. NeuroRehabilitation, 40(4), 519–529. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-171439

- Doig, E., Fleming, J., Ownsworth, T., & Fletcher, S. (2017b). An occupation-based, metacognitive approach to assessing error performance and online awareness. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12322

- Doig, E. J., Fleming, J., & Ownsworth, T. (2021). Evaluation of an occupation-based metacognitive intervention targeting awareness, executive function and goal-related outcomes after traumatic brain injury using single-case experimental design methodology. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31(10), 1527–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1786410

- Engel, L., Chui, A., Goverover, Y., & Dawson, D. R. (2019). Optimising activity and participation outcomes for people with self-awareness impairments related to acquired brain injury: An interventions systematic review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(2), 163–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1292923

- Fazeli, P. L., Casaletto, K. B., Woods, S. P., Umlauf, A., Scott, J. C., & Moore, D. J. (2017). Everyday multitasking abilities in older HIV+ adults: Neurobehavioral correlates and the mediating role of metacognition. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 32(8), 917–928. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx047

- FitzGerald, M. C. C., O’Keeffe, F., Carton, S., Coen, R. F., Kelly, S., & Dockree, P. (2019). Rehabilitation of emergent awareness of errors post traumatic brain injury: A pilot intervention. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(6), 821–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1336102

- Fleming, J., Tsi Hui Goh, A., Lannin, N. A., Ownsworth, T., & Schmidt, J. (2020). An exploratory study of verbal feedback on occupational performance for improving self-awareness in people with traumatic brain injury. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(2), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12632

- Fleming, J. M., Lucas, S. E., & Lightbody, S. (2006). Using occupation to facilitate self-awareness in people who have acquired brain injury: A pilot study. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(1), 44–55. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.05.0005

- Geytenbeek, M., Fleming, J., Doig, E., & Ownsworth, T. (2017). The occurrence of early impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury and its relationship with emotional distress and psychosocial functioning. Brain Injury, 31(13–14), 1791–1798. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1346297

- Goverover, Y., Chiaravalloti, N., Gaudino-Goering, E., Moore, N., & DeLuca, J. (2009). The relationship among performance of instrumental activities of daily living, self-report of quality of life, and self-awareness of functional status in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitation Psychology, 54(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014556

- Goverover, Y., Genova, H., Griswold, H., Chiaravalloti, N., & DeLuca, J. (2014). Metacognitive knowledge and online awareness in persons with multiple sclerosis. NeuroRehabilitation, 35(2), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-141113

- Goverover, Y., Johnston, M. V., Toglia, J., & DeLuca, J. (2007). Treatment to improve self-awareness in persons with acquired brain injury. Brain Injury, 21(9), 913–923. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050701553205

- Hergert, D. C., Haaland, K. Y., & Cimino, C. R. (2020). Evaluation of a performance-rating method to assess awareness of cognitive functioning in Huntington’s disease. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(3), 477–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2019.1640286

- Hoerold, D., Pender, N. P., & Robertson, I. H. (2013). Metacognitive and online error awareness deficits after prefrontal cortex lesions. Neuropsychologia, 51(3), 385–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.11.019

- Hurst, F. G., Ownsworth, T., Beadle, E., Shum, D. H. K., & Fleming, J. (2020). Domain-specific deficits in self-awareness and relationship to psychosocial outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(5), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1504993

- Kersey, J., Juengst, S. B., & Skidmore, E. (2019). Effect of strategy training on self-awareness of deficits after stroke. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(3), 7303345020p1–7303345020p7. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.031450

- Krasny-Pacini, A., Limond, J., Evans, J., Hiebel, J., Bendjelida, K., & Chevignard, M. (2015). Self-awareness assessment during cognitive rehabilitation in children with acquired brain injury: A feasibility study and proposed model of child anosognosia. Disability and Rehabilitation, 37(22), 2092–2106. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.998783

- Lahav, O., Maeir, A., & Weintraub, N. (2014). Gender differences in students’ self-awareness of their handwriting performance. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77(12), 614–618. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802214X14176260335309

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Levanon-Erez, N., Kampf-Sherf, O., & Maeir, A. (2019). Occupational therapy metacognitive intervention for adolescents with ADHD: Teen cognitive-functional (Cog-Fun) feasibility study. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 82(10), 618–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022619860978

- Lloyd, O., Ownsworth, T., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Fleming, J., & Shum, D. H. K. (2021). Measuring domain-specific deficits in self-awareness in children and adolescents with acquired brain injury: Component analysis of the paediatric awareness questionnaire. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.1926290

- Medley, A., Powell, T., Worthington, A., Chohan, G., & Jones, C. (2010). Brain injury beliefs, self-awareness, and coping: A preliminary cluster analytic study based within the self-regulatory model. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 20(6), 899–921. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2010.517688

- Medley, A. R., & Powell, T. (2010). Motivational interviewing to promote self-awareness and engagement in rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: A conceptual review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 20(4), 481–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010903529610

- Mendelsohn, J. B., Calzavara, L., Daftary, A., Mitra, S., Pidutti, J., Allman, D., Bourne, A., Loutfy, M., & Myers, T. (2015). A scoping review and thematic analysis of social and behavioural research among HIV-serodiscordant couples in high-income settings. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1488-9

- Merchán-Baeza, J. A., Rodriguez-Bailon, M., Ricchetti, G., Navarro-Egido, A., & Funes, M. J. (2020). Awareness of cognitive abilities in the execution of activities of daily living after acquired brain injury: An evaluation protocol. BMJ Open, 10(10), e037542. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037542

- Miyahara, T., Shimizu, H., Yamane, S., & Hanaoka, H. (2018). Occupation-based intervention to improve self-awareness in persons with acquired brain injury: A single-case experimental design. Asian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 14(1), 33–41. https://doi.org/10.11596/asiajot.14.33

- Morton, N., & Barker, L. (2010). The contribution of injury severity, executive and implicit functions to awareness of deficits after traumatic brain injury (TBI). Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 16(6), 1089–1098. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617710000925

- Nagele, M., Vo, W. P., Kolessar, M., Neaves, S., & Juengst, S. B. (2021). Assessment of impaired self-awareness by cognitive domain after traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 66(2), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000376

- Nagelkop, N. D., Rosselló, M., Aranguren, I., Lado, V., Ron, M., & Toglia, J. (2021). Using multicontext approach to improve instrumental activities of daily living performance after a stroke: A case report. Occupational Therapy In Health Care, 35(3), 249–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2021.1919954

- Ng, A. R. J., Bucks, R. S., Loft, S., Woods, S. P., & Weinborn, M. G. (2018). Growth curve models in retrospective memory and prospective memory: The relationship between prediction and performance with task experience. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 30(5–6), 532–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2018.1491854

- O’callaghan, C., Powell, T., & Oyebode, J. (2006). An exploration of the experience of gaining awareness of deficit in people who have suffered a traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 16(5), 579–593. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010500368834

- O’keeffe, F., Dockree, P., Moloney, P., Carton, S., & Robertson, I. H. (2007). Awareness of deficits in traumatic brain injury: A multidimensional approach to assessing metacognitive knowledge and online-awareness. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 13(1), 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617707070075

- O’Keeffe, F. M., Murray, B., Coen, R. F., Dockree, P. M., Bellgrove, M. A., Garavan, H., Lynch, T., & Robertson, I. H. (2007). Loss of insight in frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy. Brain, 130(3), 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl367

- Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., Desbois, J., Strong, J., & Kuipers, P. (2006). A metacognitive contextual intervention to enhance error awareness and functional outcome following traumatic brain injury: A single-case experimental design. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 12(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S135561770606005X

- Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., Strong, J., Radel, M., Chan, W., & Clare, L. (2007). Awareness typologies, long-term emotional adjustment and psychosocial outcomes following acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 17(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010600615506

- Ownsworth, T., Quinn, H., Fleming, J., Kendall, M., & Shum, D. (2010). Error self-regulation following traumatic brain injury: A single case study evaluation of metacognitive skills training and behavioural practice interventions. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 20(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010902949223

- Ownsworth, T. L., Turpin, M., Andrew, B., & Fleming, J. (2008). Participant perspectives on an individualised self-awareness intervention following stroke: A qualitative case study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 18(5–6), 692–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010701595136

- Plutino, A., Camerucci, E., Ranaldi, V., Baldinelli, S., Fiori, C., Silvestrini, M., & Luzzi, S. (2020). Insight in frontotemporal dementia and progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurological Sciences, 41(8), 2135–2142. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-04290-z

- Quiles, C., Prouteau, A., & Verdoux, H. (2020). Assessing metacognition during or after basic-level and high-level cognitive tasks? A comparative study in a non-clinical sample. L'Encéphale, 46(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2019.05.007

- Richardson, C., McKay, A., & Ponsford, J. L. (2015). Does feedback influence awareness following traumatic brain injury? Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 25(2), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2014.936878

- Robertson, K., & Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. (2015). Self-awareness and traumatic brain injury outcome. Brain Injury, 29(7–8), 848–858. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2015.1005135

- Rotenberg-Shpigelman, S., Rosen-Shilo, L., & Maeir, A. (2014). Online awareness of functional tasks following ABI: The effect of task experience and associations with underlying mechanisms. NeuroRehabilitation, 35(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-141101

- Schmidt, J., Fleming, J., Ownsworth, T., & Lannin, N. A. (2013). Video feedback on functional task performance improves self-awareness after traumatic brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 27(4), 316–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545968312469838

- Schoo, L. A., van Zandvoort, M. J. E., Biessels, G. J., Kappelle, L. J., & Postma, A. (2013). Insight in cognition: Self-awareness of performance across cognitive domains. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 20(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/09084282.2012.670144

- Toglia, J., & Chen, P. (2020). Spatial exploration strategy training for spatial neglect: A pilot study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 0(0), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1790394

- Toglia, J., & Foster, E. E. (2021). The Multicontext Approach to Cognitive Rehabilitation. Gatekeeper Place. https://www.target.com/p/the-multicontext-approach-to-cognitive-rehabilitation-by-joan-toglia-erin-r-foster-paperback/-/A-83426367

- Toglia, J., Johnston, M. V., Goverover, Y., & Dain, B. (2010). A multicontext approach to promoting transfer of strategy use and self regulation after brain injury: An exploratory study. Brain Injury, 24(4), 664–677. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699051003610474

- Toglia, J., & Kirk, U. (2000). Understanding awareness deficits following brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation, 15(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-2000-15104

- Torres, I. J., Hidiroglu, C., Mackala, S. A., Ahn, S., Yatham, L. N., Ozerdem, E., & Michalak, E. E. (2021). Metacognitive knowledge and experience across multiple cognitive domains in euthymic bipolar disorder. European Psychiatry, 64(1), 1–13. . https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.31

- Torres, I. J., Mackala, S. A., Kozicky, J.-M., & Yatham, L. N. (2016). Metacognitive knowledge and experience in recently diagnosed patients with bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 38(7), 730–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803395.2016.1161733

- van Erp, S., & Steultjens, E. (2020). Impaired awareness of deficits and cognitive strategy use in occupational performance of persons with acquired brain injury (ABI). Irish Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48(2), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOT-10-2019-0012

- Villalobos, D., Caperos, J. M., Bilbao, Á, Bivona, U., Formisano, R., & Pacios, J. (2020). Self-awareness moderates the association between executive dysfunction and functional independence after acquired brain injury. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 35(7), 1059–1068. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acaa048

- Villalobos, D., Caperos, J. M., Bilbao, Á, López-Muñoz, F., & Pacios, J. (2021). Cognitive predictors of self-awareness in patients with acquired brain injury along neuropsychological rehabilitation. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31(6), 983–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1751663