ABSTRACT

Purpose: Close others of people with acquired neurological disability often play a key role in supporting their relative to get necessary support, and therefore have valuable insight into what facilitates quality support. Situated within a series of studies aiming to build a holistic model of quality support grounded in the lived experience of adults with acquired neurological disability, support workers and close others, this study explores the perspective of close others. Method: Following grounded theory methodology, ten close others participated. In-depth interview data was analyzed using constructivist grounded theory methods to develop themes and explore relationships between the themes. Results: A multi-level system model characterizing quality support at three levels was developed. Key factors at the dyadic level included the support worker recognizing the person as an individual and the dyad working well together. At the team level, it was important for the support team, close others, and providers to engage constructively together. At the sector level, building quality systems to develop the workforce emerged as essential. Conclusions: The findings complement the perspective of people with disability and support the key notion of quality support honouring the person’s autonomy and highlight the need to raise accountability in the disability sector.

Introduction

Acquired neurological disability is associated with long-term impacts on physical, cognitive and communication capacity. Consequently, many adults with acquired neurological disability rely upon assistance from disability support workers. Disability support workers are the key frontline staff assisting people with disability to live an ordinary life and upholding their rights to participate fully and independently in society (UN General Assembly, Citation2007, Citation2016). Support workers provide a broad spectrum of supports encompassing daily and domestic living, as well as assistance with finances, employment, and housing (Hewitt & Larson, Citation2007; Iacono, Citation2010; Redhead, Citation2010).

Traditionally, support provision was largely institutionalized leaving people with little choice as to who supported them. Promisingly, in recent years there has been international progress in the disability sector towards individualized funding and personalized supports. In Australia, the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was introduced in 2013 with the promise of reforming the disability sector and creating a market-based support system centering on the needs and preferences of people with disability (National Disability Insurance Scheme Act, Citation2013). However, almost ten years on there is still limited data from the perspective of those with lived experience as to what people want from disability support. The NDIS aims to invest in the independence and social and economic participation of people with disability. Disability support is costing the Australian public upwards of $27 billion per annum (National Disability Insurance Agency, Citation2022), yet the quality of support provided by NDIS funded workers varies a great deal (Mavromaras et al., Citation2018). For the scheme to achieve its objectives, there is a need to better understand what good disability support looks like and improve the quality and consistency of the support delivered to people with disability in Australia. Thus, this research is one in a series of studies aiming to build a holistic understanding of quality support grounded in lived experience, the first of which explored the perspective of adults with acquired neurological disability (Topping et al., Citation2022b). Considering the complex needs many adults with neurological disability experience, close others (family or partners) often play a role in either providing informal support or coordinating paid supports (Holloway et al., Citation2019; Manskow et al., Citation2015). Close others therefore tend to have considerable understanding of what quality support looks like. In addition to sharing their own perspective, they can give some insights into the experience of people with disability who are not able to be their own informants because they do not have the capacity to participate in an interview. Despite the clear value of close other experience, limited research has explored their perspective on support provision, as evidenced in our scoping review in which less than a third of the reviewed papers considered the close other perspective (Topping et al., Citation2020).

Research has described how acquired neurological disability affects the family or partner. Family members often experience psychological distress and reduced quality of life in response to adjusting to the changes in their loved one following illness or injury (Rasmussen et al., Citation2020; Tam et al., Citation2015) and coping with changes in family dynamics (Holloway et al., Citation2019; Stenberg et al., Citation2022). Close others frequently take on significant caregiving roles which come at a cost to their health and well-being (Douglas & Spellacy, Citation2000; Holloway et al., Citation2019; Manskow et al., Citation2015). Exacerbating the psychological distress, family members often cover significant financial costs to meet the needs of their close other with disability (Everhart et al., Citation2020; Lehan et al., Citation2012). Feeling supported by professionals and informal supports can reduce distress for close others (Holloway et al., Citation2019), but lack of continuity of support increases stress and anxiety (Ahlström & Wadensten, Citation2011; Gridley et al., Citation2014). Moreover, evidence suggests that the impact of psychological distress can be reciprocal, e.g., the higher the close others’ feelings of burden, the poorer neuropsychological functioning of their relative with disability (Lehan et al., Citation2012). Thus, it is important to consider the familial impact of neurological disability when considering support for people with acquired disabilities.

The limited research exploring close others’ perspective on quality support provision aligns with our scoping review and research reporting the perspective of adults with acquired neurological disability (Topping et al., Citation2020, Citation2022b). Crucially, it is concluded that people with disability must have autonomy over their support provision (Ahlström & Wadensten, Citation2011; Topping et al., Citation2022b). Close others of people with severe neurological disability in Ahlström and Wadensten’s (Citation2011) study considered it to be a lack of respect when support workers take over and do not allow people to use their capacity. Correspondingly, close others value support workers taking time to build an understanding of the person’s needs and taking a flexible approach in responding to needs (Fadyl et al., Citation2011; Gridley et al., Citation2014). Thus, it is important that support workers have sufficient knowledge to fulfil their role but are also willing to listen and learn (Fadyl et al., Citation2011). Aligned with our earlier research, close others stressed the importance of people with disability feeling seen and treated as a person by their support workers (Ahlström & Wadensten, Citation2011; Fadyl et al., Citation2011).

Given the proximity of support work, close others recognized the value of the person with disability and support worker building a mutually respectful relationship (Ahlström & Wadensten, Citation2011). Close others felt personal chemistry (i.e., getting along well) between the person and their support worker fostered a good relationship (Ahlström & Wadensten, Citation2011). This sentiment was reinforced by people with acquired neurological disability who wanted support workers who they feel are the right fit (Topping et al., Citation2022b). A good working relationship also promotes reciprocal trust and respect between the person with disability and their support worker (Bourke, Citation2021), which close others consider to be vital for quality support (Mitsch et al., Citation2014).

Considering the limited research from the perspective of close others on the quality of support but the considerable role they often play, this study aims to understand the perspective and lived experience of close others around quality support provision. We also hoped to gain a better understanding of the experiences of people with disability who do not have the capacity to participate in an interview. Upon completion, we plan to combine this perspective with our research with people with acquired disability (Topping et al., Citation2022b) and support workers (Topping et al., Citation2022) to inform practice and policy and improve the quality of paid disability support.

Method

Study design

This qualitative research study followed a constructivist grounded theory approach (Charmaz, Citation2006, Citation2014). Constructivist grounded theory recognizes the multiple perpectives that different people can take in life (Charmaz, Citation2006). It is therefore appropriate for exploring research questions concerning interactional experiences about which little is known, like that of paid support for adults with acquired disability. Social constructivism recognizes knowledge as a socially constructed process and appreciates the influence of the reciprocal interaction between the researcher and the participant on the generation of data (Charmaz, Citation2014). Consequently, the meaning derived from the data and the subsequent theory generation is considered to be mutually constructed between the researcher and the researched (Charmaz, Citation2014).

Participant recruitment

Institutional approval was obtained from the University Human Ethics Committee (HEC20253). Participants were purposively recruited via a non-for-profit organization or through snowball sampling via participants in the related studies (Topping et al., Citation2022b, Citation2022). Participants were contacted via telephone or email by an independent staff member and screened to ensure that they met the following criteria: 1) had a close other (e.g., partner, family) with a neurological disability who was in receipt of one-to-one paid disability support; 2) at least 18 years of age; 3) able and willing to participate in a 60-min interview. Participants were given a gift voucher following participation. One invited participant could not participate due to personal commitments.

Participants

Ten close others (9 female, 1 male; mean age 64 years, range 57–74 years) of people with neurological disability living in Australia (9 Victoria; 1 New South Wales) participated in the study (see ). Eight participants were parents, and two were spouses of people with disability (9 with acquired brain injury; 1 with cerebral palsy). The people with disability had high support needs, ranging from Level 4 (can be left alone for part of the day and overnight) to Level 7 (cannot be left alone) on the Care and Needs Scale (Tate, Citation2004) and required an average of 117 h of paid support per week (range 20–168).

Table 1. Participants characteristics.

Procedure

Participants were provided with a written and verbal introduction to the study, and the researcher’s motivations (i.e., doctoral research), from the independent staff member. Upon confirming interest in taking part, potential participants were offered the opportunity to discuss the study with the first author. Following written consent to participate, participants completed a self-reported questionnaire to capture demographic information about themselves and the support needs of their close other. The first author, a female doctoral candidate with experience conducting research interviews with a range of adults, conducted the interviews between December 2020 and March 2022 via Zoom videoconferencing (6) or telephone (4). Interviews lasted between 30 and 90 min and lasted mostly around 60 min. One participant’s husband was present, and one participant’s son was in the home during the interview. Otherwise, only the researcher and participant were present. The interviews followed a semi-structured schedule with open-ended questions around experiences with paid support workers, and the factors that influence the quality of support (see Appendix 1). The researcher took a flexible approach to interviewing, using probes to encourage detailed reflections and insights. Considerations were made to ensure the remote interviews were practically, ethically, and methodologically sound in accordance with the literature (Topping et al., Citation2021, Citation2022a). One consideration involved the researcher having informal conversations with participants to build rapport prior to the interviews. Interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. On receipt of the transcription, the researcher verified the transcripts against the audio recordings to ensure accuracy. No repeat interviews were necessary.

Data analysis

Analysis followed Charmaz’s (Citation2006, p. 2014) constructivist grounded theory iterative coding process (initial, focused, and axial coding) and was conducted using NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2020) concurrently with data collection. The first five transcripts were coded by the first and second author to identify alternative interpretations which had not been considered before the first author coded the remaining transcripts. Facilitated by field notes and ongoing memo writing, assertions and emerging themes arising from the data were scrutinized through regular interactions between the three authors. Constant comparison techniques were employed to compare within and among data cases to facilitate conceptual abstraction and ensure the themes remained grounded in the original data. Once theme saturation in relation to the research question was apparent, no further sampling was undertaken (Constantinou et al., Citation2017; Vasileiou et al., Citation2018).

Quality

The authors approached credibility of the study by incorporating strategies to create a comfortable space for participants to share authentic information (i.e., rapport building) and thoroughly documenting the data collection process to ensure the analysis and subsequent theory generation were grounded in the data (i.e., through memos, field notes and diagrams). Regular debriefing sessions between the three authors, who have varied academic and practice experience, provided opportunities for reflexivity, and helped in providing alternative interpretations and enhanced credibility. Alternative interpretations by the authors during the emerging analysis were resolved by considerations of the transcripts, field notes and memos, with further discussions until agreement was reached. To ensure data authenticity and resonance with participants, the first author prepared a short summary of each participant’s interview contributions for the participant to review and provide feedback or additional insights. Resonance and usefulness at a broader scale were established through presentation and discussion at local and international forums throughout the research process. To illustrate that the themes are grounded in the participant’s lived experience, supporting quotes are presented throughout the results with additional quotes in . Pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of the participants and their close others with disability. The study was conducted and reported according to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Table 2. Themes, subthemes and additional quotes illustrating the factors that influence the quality of support.

Results

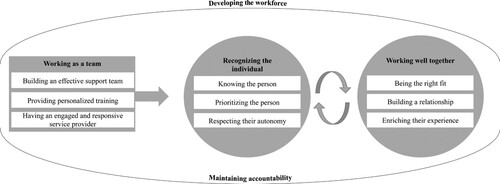

The factors influencing the quality of support emerged as a multi-level process with factors at 1) the dyadic level between the person with disability and support worker, 2) the wider support team level (i.e., support worker team, close others, and service providers), and 3) the sector and broader system (see ). In the dyadic space, participants felt that it is important that support workers recognize the person as an individual and the dyad work well together. These two factors interact such that getting one right influences the realization of the other. Underlying both the dyadic space and the support team level is a perception of the need for the support worker to maintain accountability for their role. It was also felt that support workers need to be accountable in preparing to be a support worker, as well as in the delivery of support in the dyadic space. At the wider support team level, it is important for informal supports, service providers and support workers to work as a team. Finally, at the broader sector and system level, it was felt that we need to develop the workforce to ensure they are supported to provide the best quality support.

Figure 1. Model of quality disability support from the close other perspective.

Recognizing the person as an individual

Close others considered it critical for support workers to see the person with disability as an individual with unique needs and preferences. It was felt that support workers should not make assumptions based on disability type, and instead take a holistic view of the person and be focused on their individualized needs. Correspondingly, close others wanted support workers to show respect and interact directly with the person with disability as described by Laurie.

They need to respect Jade. And they need to be mindful of her dignity … we had trouble in the early days of people talking about Jade in front of Jade, you know? … You don’t talk about Jade as if she’s not there, you address her and all of that so that’s certainly one of the things you know and just respect. Laurie (parent)

Knowing the person

Close others felt it was important that support workers take time to get to know the person, learn how they communicate and how they want to be supported. They stressed this as a safety precaution when supporting someone with complex needs (e.g., providing medication). They felt that knowing the person well enables support workers to better read the person and pick up on their needs, which is especially important for people who cannot direct their supports in the moment.

He’s very, very dependent on who is with him at the time, and whether they know how to read the signs … whether they know that he should sleep or whether he should wake up or whether he’s had a bad night, so you don’t expect him to be doing his switching or something that requires a lot of concentration … . you have to be able to read the person and where the person is at the time. I think there’s two aspects: knowing the person really well and having that ability to read the situation and the person. Chris (parent)

Prioritizing the person and their needs

Close others emphasized that support workers should prioritize the person with disability, pay attention to them and be proactive in responding to their needs. They overwhelmingly condemned support workers spending too much time on their phone, rather than focusing on meeting the person’s needs. Considering the complexity of people’s needs, close others stressed the dangers of support workers not paying attention to the person’s well-being.

And part of that job is not that you go off and sit on your phone and say, “I’ll be there in a minute,” which we have had done, because they’re on Facebook. No. Your client comes first. So, if they’re not prepared to do that, they shouldn’t be going into that job … If you’ve done your job, no one has any problem with that. But it’s not the priority. It’s not the thing you think about first. Taylor (parent)

Respecting the person’s autonomy

Close others emphasized the support worker’s role is to support people to live the life they want to live. Support workers should ask the person what they want and be willing to listen and take direction, rather than thinking they know best. Close others wanted workers to take a flexible approach to supporting the individual to meet their needs and preferences. Correspondingly, they felt that support workers need to respect the person’s dignity of risk.

I think the best quality would be to do what the client wants. To ask them, and to do what they want, and the way they want it done … They’re the two but listening to the client is really – not imposing your way, which a lot of people do. “I’m doing it my way because my way is better.” No. You are here for the client, that’s really important. Taylor (parent)

Working well together

Being the right fit

Considering the amount of time support workers spend with people with complex needs, close others emphasized the importance of the pair getting along well and being a good fit. Close others felt support workers who were a similar age and the same gender were often the best fit as they could relate to the person and were more likely to have similar personalities and shared interests. For some people with disability, it was important to have support workers who were the same gender due to previous trauma.

Similar personalities can be a great one, especially if somebody’s interested. Jo played the guitar really well before he got sick, so if there was anybody that was interested in music or could come and play the guitar or you know? They’re human beings. The carers are human beings that come in and it must be really hard for them to walk into a house with people and try to find that – they spend a lot of their life here with Jo, so they’ve got to be able to get on with each other. Shannon (parent)

Building a working relationship

Close others deemed a good working relationship one that reflected friendship, but with an understanding that it is a working relationship. They discussed how some service providers placed too much importance on boundaries, rather than the connections they believed were critical to quality support. Relationship quality was especially important as those with complex needs did not tend to have large social networks. However, this notion was tempered by the importance of the relationship being led by the preferences of the person with disability. Largely, close others felt that the relationship naturally develops over time as familiarity and rapport grows.

Sort of on a friend line, you know. Close but not too close because I think when they’re too close, they think they should sit right beside you, they should do everything with you, as a friend, you know … but that’s Jess’ choice. And a lot of the times, that’s what Jess will have. But sometimes she likes to change it. Francis (parent)

I guess the things about this journey for us is - I mean, Lou can't choose people - Lou, today, still does not know the name of the support workers that he has had with him for six years. But he’s familiar … comfort, like around security about, “Oh, they know my stories” sort of thing - but he couldn't tell you what their name is. And he couldn't tell you when he saw them last … but he has the feeling of safety. Sammy (spouse)

They need to not get offended if they’re not asked to join a group at the table, because they’re not there to be – you know, Jess usually does have people join her –, the carers join her, but sometimes she doesn’t want them if she just wants a girls’ day out, but they need to be there to toilet her or something. You know, they get offended if they’re not included. Francis (parent)

Enriching the person’s experience

Close others emphasized the importance of support workers understanding their impact on the person’s experience and wanting the best for them. Correspondingly, they wanted support workers to be kind and come to work with a positive attitude, leaving their personal problems behind. Close others reflected that this was particularly important for people who rely upon support workers for interaction as well as support. Close others also valued support workers who used their initiative to find hobbies and interests the person may enjoy and motivated the person to engage in activities.

[Support worker], that works with him on a Tuesday, is so caring, and she really puts kindness into the day. And so, when he’s been out with her for a walk along the water, for an hour, and done the shopping, he comes home happy. She’s made a difference in his day, she’s brought a smile to his face, he’s laughed, he’s been a human again. Because he hasn’t been like that since his injury. Like he used to laugh, and we all have lovely times together, but being out in the sunshine, and – in other words, she wants Drew to have the best day he can. And if she can bring that smile and the loveliness to the day, it’s so beautiful. And I don’t have to worry on a Tuesday because I know that he’s happy. And that’s a beautiful thing, it puts me in a – well, it gives me a smile on my face. Remy (parent)

Maintaining accountability

Close others believed quality support provision relies upon support workers maintaining accountability in their role by committing, preparing, and engaging in reflective practice.

Once they get in the place of hire, I think a lot of them work a lot better when I’m down there. When Jess is on her own, I don’t think some of them work as well … One carer, every time we go down, she walks up and down the kitchen area looking for something to do. And you see her. And I just really want to laugh because I think, yeah, normally you’d be sitting here watching TV with Jess, but because we’re there, you’re looking for something to do. But she doesn’t actually touch anything or do anything, she just walks up and down … Jess tells me things all the time, you know, what happens when I’m not there. Francis (parent)

Wanting to do the role

Close others felt quality support workers are those who genuinely want to do the role and commit to the person they are supporting. Close others had experienced support workers who were only doing the role because they needed a job and felt the best support workers were those who were interested and enthusiastic and dedicated to the person they support. Commitment was critical because people with complex needs depend upon support workers knowing their needs, and reliably showing up to support them.

There needs to be a screening process of, who is doing this because they can’t get a job doing anything else, and who has a desire to do it, or who wants a job and doesn’t necessarily have their total heart in it but will do their best? … And I did interview people – At one stage, we put a job on Gumtree, and people were ringing me crying and saying, “I need a job.” “I need a job.” And I’m thinking, “I can’t. I feel for you, but that can’t be the quality that I employ you on. That you need a job. You have to want to do something to help my daughter.” Taylor (parent)

Being prepared for the role

The first step in preparing for the role was support workers understanding what their role entails. At a high level, close others wanted support workers to understand that their job is to holistically support the person to live how they want to live. At an individualized level, close others felt support workers have a responsibility to ask questions to gain a comprehensive understanding of what is expected of them, as it will differ person-to-person. Close others believed some workers come to the role underestimating the complexity and importance of the position. Correspondingly, some close others wanted support workers to have training about what it is like to have a disability from the perspective of people with lived experience. Coming to the role with a good understanding also means support workers are more likely to stay and be committed.

Your client comes first … That would be really important to get in that first day. This is what the job entails, you know. This is what you might be doing. You know, you might be going to the toilet. Helping people go to the toilet. There’s things that you mightn’t like the sound of, so understand that this is what the job entails, but also understand that the dignity of those people relies on people coming in and being prepared to help them do those things. You know, it’s really important. Taylor (parent)

I want someone who has basic skills definitely, but also, you know, it really does help if they have some experience with people who are non-verbal or have severe communication difficulties and also severe physical impairment, because if they’ve got that experience then we’ve got a base and we can just do Jackie specific training. Chris (parent)

So, just being willing to learn. Look like as if you're interested in the job. It's like anything, really … and whatever they've been taught outside, I'll probably teach them something new, or they might teach me something new. So, you learn off each other. Kelsey (spouse)

Engaging in reflective practice

Close others emphasized that support workers need to engage in reflective practice to improve and maintain quality support. Crucial to engaging in reflective practice was support workers understanding that they will make mistakes and being willing to take responsibility and learn from mistakes. Additionally, close others wanted workers to communicate when mistakes had been made to the person they’re supporting, the key worker or the close other. Close others also valued support workers acknowledging when they are unsure, being confident to ask for help and get advice from the person with disability, or people who know the person well. Close others felt support workers should continually reflect on their practice and decide if there is a better way to support the person. One close other had set up a mechanism for the key worker to facilitate this reflection through regular performance reviews.

Give it a go. Don't be frightened. If you make mistakes, make them and ask questions. Don't just stand there like a - whatever. Kelsey (spouse)

Working as a team

Building an effective support team

Close others played a key role in building and coordinating their close other’s support team and provided strategies around building an effective team. First, close others stressed that the person with disability and close others should be involved in choosing support workers. Discussing roles within the support team, close others stated that all team members should be competent to fulfil required tasks and capable to cover any shift. Some workers were employed or rostered according to specific skills or interests, but this was supplementary to knowing the basics.

And the idea is that everybody can do everything here 'cause it hasn’t worked in the past when they haven’t … I think it only probably applies to us because Jo’s so high-level care, but it’s got to be all-inclusive. If you’re looking after somebody that’s high care, you’ve got to do everything that they can’t do. Shannon (parent)

And it’s why I need that communication is Allison can’t relay what she’s done. She can’t explain. “Oh, nothing,” she’ll say, and I’ll say, “Well, he can’t be there for four hours and you do nothing, you must be doing,” so you sort of think, “Oh God, I hope they did something.” Vic (parent)

They're casual workers. They're not employed permanently. They get asked to do shifts, and they can say “yes” or “no”. I feel like there's not as much commitment when you have people who can just do whatever they like and they can call up an hour before and say, “Look, I'm not coming on the shift”. Absolute nightmare stuff. So, I pushed very very very hard to give the smaller section of the team that did consistent rosters week after week after week, permanent part-time - to employ them permanent part-time … Because it's not working for the stability of the team when you can have people that can just say, “No, I'm not coming”. Or, worse, what I found when I was first interviewing people, I'd say, “Well, how many hours a week are you looking for?” “Oh, well, I do 96 hours at the moment”. I work 38 hours, 40, and I'm exhausted … you know, then I'd say, “okay, that's a lot of hours” and then “I do 96 to 110 hours a fortnight”. I'm like, f**k, that's crazy. And as I sort of learnt more as I went along, I realized it’s because they didn’t know what was going to happen the next fortnight. So, they did all the work they could, and then they were exhausted. Sammy (spouse)

Honestly if everybody could have a team leader like [key worker] that would be amazing. In fact, I honestly think that would help families so much. We have been so lucky. We’ve always had team leaders 'cause I created that and you know to try and pass on you know to organize and plan and do rosters and all that, we’ve always had them but mainly at much, much lower scale than what we have now. And [key worker]’s the perfect person to do this, she oversees everything. What a tremendous support … she’s amazing at overseeing the program … and the team know they can text [key worker] or email her any time … [key worker]’s just a tremendous support. To the team and to us so I think, you know, you can’t have a program like that without anybody at the helm and overseeing it. Laurie (parent)

Providing personalized training

Close others stressed that support workers need to be trained in how to provide personalized support. They acknowledged the importance of taking time to train new support workers to ensure they are comfortable and competent before doing independent shifts.

It takes a long time to be able to work with Jo, so they can’t just phone anybody in off the street or off their books. It’s got to be somebody that’s personally trained to work with Jo … It takes a long time and I think 'cause Jo’s non-verbal and can’t do anything or instigate anything, there’s so much to learn … So, they’re never thrown in the deep end. Takes about six months and I’ve got to feel comfortable, and they’ve got to feel comfortable before they do an independent shift with Jo. Shannon (parent)

I just say to them, “We’ll give you a few shadow shifts and let’s see what happens.” And I bought four shifts, to be fair, so they can see what’s involved, and ask them, “How do you feel about it?” Because there’s personal care. And especially when it’s males it’s sometimes not – and then if they’re okay with it, then we just work out how many more shifts they need. Give them as many shadow shifts as they like. No limits. And that’s another thing where agencies, often you don’t get any or you might get one. So, these last two, I think they had two solid weeks each, every day … You tell me when you’re ready. Ali (parent)

Having an engaged and responsive service provider

The importance of an engaged, hands-on service provider was emphasized by close others who did not directly employ support workers. Close others described quality service providers as those who know the person with disability well and reliably match appropriate workers to them. They reflected that it helps if there is a staff member assigned to the person’s rosters, who develops a relationship with the person with disability and close others and involves them in choosing support workers. Quality service providers should also know their support worker employees well and ensure they are competent and prepared before working with a person with disability. Close others wanted service providers who prioritize the needs of people with disability over making money. Crucially, service providers need to listen to and communicate with the person with disability and their close others (when appropriate) effectively. Close others also discussed the need for service providers to have efficient processes (e.g., onboarding new workers), look after their staff (e.g., pay fairly and provide managerial support) and have competent and stable management. Finally, close others discussed the importance of the service provider’s values aligning with theirs (e.g., not having rules and regulations that limit the person’s autonomy).

I think you have to pick your care agency well. And you have to develop a good relationship with the person who is finding the staff, so they understand and [service provider], they’ll come out and they meet Jackie, they talk to me and whoever’s managing will develop a good rapport with me and a good rapport with Jackie, and work as part of the team. So I think that’s really important, too. It’s not just a faceless person sitting at a desk, allocating staff. I think it’s really important to have an agency where they become very involved and hands on at the management level. Chris (parent)

Developing the workforce

Increasing and retaining quality workers

Close others commented on the variable quality of the workforce, stating that while some workers were of high quality, a considerable number were poor-quality workers. This inconsistency meant the close others’ role in coordinating and overseeing their close others’ support team was greater. Close others also discussed the low availability of quality workers of certain demographics (e.g., younger males) or with the skillsets required for complex needs.

It’s not always easy to get that, the age. Especially, like, the males are much harder to get. To get people at that age with the kind of mentality you want and character and stuff like that is a bit tricky too. Ali (parent)

I think it’s the industry growing too quickly, which it has to – because people are finally being given the time they need and the support that they need, but the sector can’t cope with it, and there’s not enough people, and there’s not enough good people. Taylor (parent)

We’re trying to train up some people, but yeah, it’s really unsettling too, because consistency is so important to Jackie. I mean, variety is good to an extent, but we've just had – got COVID at his house. Well, first of all, we had a dreadful manager and everybody left, because they couldn’t work with her and then we’ve had – this is all during COVID. And then we’ve had the staff shortages because people have been, you know, close contacts or they’ve had COVID, so there’s been so many agency staff in there. It’s really been very, very tough. Chris (parent)

Improving working conditions

Close others felt with better working conditions, the sector would better attract, retain, and foster quality workers. Considering the casualization of the workforce, close others discussed the importance of giving support workers security in their roles. Close others believed uncertainty around income led to burnout in workers who overcommit to shifts. In turn, leading to poor quality or unreliable workers, and workers leaving the sector for permanent roles. Some close others tried to overcome this problem by negotiating with service providers to give the support team a set-roster or employ them on a permanent part-time basis. Otherwise, they employed workers directly and provided set-shifts.

They have long shifts and they have set shifts. And I think that makes a huge difference to the workers because they’ve got security. And we don’t cancel shifts. If Ellis went to hospital, they go too. So, 24/7, 365 days a year … they’ve got bills to pay and have got to work to make the money to do so, so a two-hour shift here and then I’ve got to drive an hour and a half to get to there … So, out of my 10-hour day, I might work five hours. Or cancelling at the last minute … That can be a problem for staff too. Of course, they’re going to go where they’re going to get permanent set shifts. And the longer the shift, the better … And they know that they’ve got that shift. Well, one of them says, like, “I don’t even need to because I earn enough money that I don’t have to burn myself out.” And that’s the other thing too, if people were getting paid low and having to run around and do all – they’re just going to work seven days a week and burnout. And why would they have patience on the seventh day for your kid? Ali (parent)

Jo’s really high care and it is almost like nursing. And yet, they get the same pay that somebody gets just to take somebody to the pictures. Or take them to the shops. And we’ve always thought that if you’re doing the higher level of care there should be different grades of pay. And I think if they brought that in, they’d get a lot more support workers wanting to do more of the personal care shifts and the higher care shifts. Shannon (parent)

An agency’s involved and you’re getting treated like crap, you kind of get deflated sooner or later and then you’re burning out because you’re doing 10-hour days and get five hours pay and you’re travelling. So you know, that something’s got to give. Ali (parent)

And a difference to the support workers as well, because the support workers felt undervalued. They didn’t feel undervalued by Lou or I. They definitely love being with us, and they all say that. They’ll all say they have quite a connection with us and really like being with us, but you know how management can fall down, and it just doesn’t work. They’ve really loved having [key worker] step into that role, because she cares about them as individuals. And speaks to them about their needs and makes sure that those needs are met for them which makes them better employees because they’ve got job satisfaction and job security – and they feel like they’ve got someone to turn to when there’s a problem. So, it’s powerful. Sammy (spouse)

Raising accountability in the sector

Close others deemed the disability sector to have lower standards for workers than other human service industries and therefore stressed the need for the sector to be more accountable for service quality. Close others provided examples of service providers sending incompetent, unprepared staff to support their close other and felt there were minimal consequences for workers or providers on these occasions, despite the dangerous risks for people with disability. Some close others did not want to directly employ support workers because they did not trust agencies to reliably provide backup support should their regular workers call in sick. Correspondingly, close others wanted better oversight to hold providers and workers accountable, as they experienced providers and workers giving excuses for poor quality services, rather than being responsible and making changes.

They don’t have the same standards that they have for any other employment. No boss pays you to sit and smoke, to go on Facebook, to, you know, read a book, whatever, unless there’s down time … It’s a real culture shock coming into this sector which is so poorly run … My job demanded so much accountability that I can’t cope with this sector that there is no accountability. And there is no, “Oh, well, you know, we’re sorry that happened but, you know, we will make sure it doesn’t happen again.” It’s always excuses why it happened. And, you know, “Oh, well, we can’t get staff. We can’t do this. We can’t do that.” Well, no one’s overseeing that, you know … But this sector, this is people’s lives as well, and no one’s doing anything about it. Taylor (parent)

And for people that have an acquired brain injury, that don't have an advocate, oh, it's so sad. It makes me sad. Makes me want to cry sometimes when I think about people who don't have an advocate … I do wonder how people that have a disability that don’t have an advocate, how they have quality support workers, how they have consistent support workers, how they just survive. Sammy (spouse)

There’s no way I can fix this. That’s the frustrating thing. I can’t make providers do the right thing. I can’t get support workers to be reliable and turn up and do the right thing. I can hope the ones that she’s got now are good and they’ll stay with her. But I’ve just got no control that this industry has anyone checking that things are okay … because I don’t believe the NDIS Commission is doing that. I believe the NDIS Commission, like the NDIS, is geared towards providers. I don’t even think the NDIS puts people with disabilities first. I think they put providers first. The NDIS should be responsible for the people they register. They should be checking them. They’re not. You know, they’re not. It’s, sort of, all care, no responsibility … They’re not even checking a provider that’s looking after people that can’t do things for themselves, you know … . Especially at a time when there’s a Royal Commission. It’s almost like, “Oh, we’re not worried by that.” You know. “It doesn’t scare us. Nothing will come of that.” Taylor (parent)

Discussion

This study sought to understand the perspectives of close others of people with acquired neurological disability around what facilitates quality disability support. Combining the findings from this study with our earlier studies exploring the experiences of people with acquired neurological disability and support workers (Topping et al., Citation2022b, Citation2022), we hoped to identify policy and practice recommendations to raise the standard of disability support. Quality support from the close other perspective emerged as a multi-level system, with factors influencing quality at the dyadic level, team level (e.g., support workers, providers, and close others) and sector level.

Encouragingly, there is strong congruence around the key elements of quality support in the dyadic space across the perspectives, with the most important factors being the support worker recognizing the person as an individual and the dyad working well together. Considering the focus of the NDIS on individualized, person-centered support (National Disability Insurance Scheme Act, Citation2013), these findings are promising. The dyadic factors identified by close others reinforce our findings from the perspective of people with disability (Topping et al., Citation2022b) and support previous research endorsing the importance of autonomy, humanizing practice, and developing a balanced working relationship (Ahlström & Wadensten, Citation2011; Fadyl et al., Citation2011; Robinson et al., Citation2020; Topping et al., Citation2020). A limitation of our earlier study was that it did not include people with severe cognitive and communication impairments because they were unable to participate in an interview. However, close others in this study gave insight into the experience of people with severe communication impairments, including memory challenges acquired as a result of the neurological disability, and respecting autonomy and building a relationship were still deemed critical. The slight nuance of these findings is the close others’ emphasis on the support worker getting to know the individual and in turn, being able to read the person, deliver support safely and in line with their preferences. The importance of knowing the individual aligns with previous research stating that support workers should take time to learn how to support someone (Fadyl et al., Citation2011; Gridley et al., Citation2014). These findings also put the onus on the support worker getting to know the individual, rather than the person leading their supports, which as previous research suggests, can be burdensome for people with disability (Bourke et al., Citation2019; Fadyl et al., Citation2011; Gridley et al., Citation2014; Martins & Dreyer, Citation2012; Topping et al., Citation2022b). Thus, while some people will want and have the capacity to lead their supports, different strategies may be required with people who do not want to or cannot due to severe neurological disability, but the key principles around recognizing the person and respecting their autonomy remain.

Beyond the dyadic space, close others discussed the importance of working as a team to provide quality support to people with complex needs. A strong sense of the close other’s commitment to managing and training the support team was evident among participants. Consistent with previous research documenting the “unavoidable duty” and psychosocial burden close others experience (Douglas & Spellacy, Citation2000; Holloway et al., Citation2019; Knight et al., Citation1998; Lehan et al., Citation2012; Manskow et al., Citation2015), participants discussed the impact of this responsibility on their emotional well-being. Some close others had established mechanisms to reduce this burden, including appointing a team leader, implementing communication strategies, and ensuring all support staff were competent to cover all shifts. However, the burden prevented some close others from directly employing staff, and those participants stressed the importance of having a good service provider who was committed to reliably providing quality, personalized support. Therefore, more robust support for close others and better back-up support networks to facilitate people’s authentic choice around their support arrangements are needed.

Given the abuse and neglect uncovered by the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability in Australia (Commonwealth of Australia, Citation2021), it is unsurprising that close others lack trust in the disability sector to provide quality support. Close others voiced concerns about what would happen if they could not oversee workers or cover shifts and therefore wanted to raise accountability within the sector. With workers and providers being held accountable at the sector level, close others would be better positioned to trust workers and providers, and therefore be less involved in coordinating supports. At the support worker level, with greater sector accountability, support workers would come prepared and willing to learn, allowing time for effective personalized training, rather than time and effort spent on training basic competencies (Bourke et al., Citation2019; Gridley et al., Citation2014; Topping et al., Citation2020, Citation2022b). Further, consistent with our earlier findings (Topping et al., Citation2022b), close others felt they could rely on workers who understood and were committed to the role and engaged in reflective practice. These findings align with the expert consultant on our scoping review, who felt that the wider system needs to hold support workers accountable to ensure best practice (Topping et al., Citation2020).

The factors identified relevant to the broader sector are consistent with the struggle Australia is facing to build a quality workforce large enough to meet the needs of over 500,000 NDIS participants. In response to this challenge, there are government and industry efforts to improve the workforce (Australian Government, Citation2021; Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Social Services), Citation2019), and a regulatory body, the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission, has been established to uphold support standards (Australian Government Department of Social Services, Citation2016). However, with labour shortages, close others felt that quality is often sacrificed to meet demand. Moreover, close others feared poor working conditions exacerbate labour shortages and result in burnt out workers (Alcover et al., Citation2018; Judd et al., Citation2017; National Disability Services, Citation2018, Citation2021; Smyth et al., Citation2015). Echoing concerns raised by people with disability (Topping et al., Citation2022b), workforce issues have a flow on effect to people’s choice of quality workers. Thus, with better working conditions and more accountability in the sector, the workforce could be of higher quality, giving people with disability authentic choice and control over their support provision.

Future research

The next step in this research is merging the perspectives of people with acquired neurological disability (Topping et al., Citation2022b), support workers (Topping et al., Citation2022), and close others to form a holistic model of quality support. With this foundation, we plan to conduct a co-design project with people with acquired neurological disability to develop and test practical solutions to improve support quality. Additionally, and importantly for the Australian context, future research should endeavour to learn the perspectives of different cultural groups including Indigenous communities in relation to support provision. As seen in this study and our previous research (Topping et al., Citation2020, Citation2022b), quality support is determined at the individual level, and considering the relational nature of support, expectations are likely to differ between communities.

Implications

This study demonstrates the pressing need to raise the standards and expectations of the disability support sector. The responsibility of coordinating and overseeing supports should not fall to close others, especially given the detrimental impact on the health and well-being of close others and many adults with disability do not have close others who can take on this role. Consistent checks and balances at the provider and sector level are needed to ensure competent support workers are reliably showing up and providing quality support. In support of our earlier research (Topping et al., Citation2022b), this research highlights the demand for micro-credentials for specific technical competencies, and support workers coming prepared to engage in personalized training, rather than relying on broad formal qualifications. To tackle labour shortages and attract and develop quality workers, employers should look after staff, incorporate professional development opportunities, and provide the means and support to deliver best practice. However, it would be remiss to assume these changes will eliminate the close others’ role in supporting relatives with complex needs to receive quality support, at least in the short term. Therefore, this research, along with expertise from people with disability (Topping et al., Citation2022b), should be used as a foundation for co-design work producing resources to guide people with disability and their close others who are navigating support systems, screening, and training workers and managing support teams.

Strengths and limitations

This research is the first constructivist grounded theory study to explore the close other perspective on quality support for people with acquired neurological disability. The greatest contribution of this project will be the amalgamation of the findings from the three perspectives to build a model of quality support grounded in lived experience. A strength of this study was the breadth of experience the participants had with support workers, providers, and the NDIS, meaning they provided rich data around support quality. Beyond the close other perspective, this study provided insights into the experience of people with higher support needs, who are unable to directly lead their supports. Thus, this study combined with our previous work represents a larger spectrum of disability needs. Moreover, these findings complement and expand upon those from our earlier study (Topping et al., Citation2022b), strengthening the development of a holistic model of support. The most pertinent limitation of this study is that it represents one perspective, and while close others can provide great insight into the experience of people with disability, they are not the primary voice in this conversation. Thus, these findings should be viewed alongside the perspective of people with disability (Topping et al., Citation2022b). In addition, the participants experiences are specific to the Australian disability system and multicultural representation was limited in the participant group, thus as described above, more research is necessary to understand the support experience across different cultural groups.

Conclusions

Seeking the perspectives of close others of adults with acquired neurological disability has deepened our understanding of what quality support looks like for this group. We have developed a quality support model involving influential factors at multiple levels (i.e., dyadic, team and sector). This study has provided additional insights into working as a support team and the interaction with the broader sector. The broader system was discussed by people with disability in terms of how it facilitates or hinders choice, but close others have provided additional insights. Crucially, the factors at the dyadic level between the person with disability and their support worker complement and strengthen our findings from people with disability emphasizing the importance of recognizing the person as an individual and respecting their autonomy (Topping et al., Citation2022b). Together, these studies have important policy and practice implications and advance our learning to improve the quality of disability support.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge and thank the close others who generously shared their experiences and perspectives, making this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahlström, G., & Wadensten, B. (2011). Family members’ experiences of personal assistance given to a relative with disabilities. Health and Social Care in the Community, 19(6), 645–652. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01006.x

- Alcover, C. M., Chambel, M. J., Fernández, J. J., & Rodríguez, F. (2018). Perceived organizational support-burnout-satisfaction relationship in workers with disabilities: The moderation of family support. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 59(4), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12448

- Australian Government Department of Social Services. (2016). NDIS Quality and Safeguarding Framework. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/04_2017/ndis_quality_and_safeguarding_framework_final.pdf

- Australian Government, D. of S. S. (2021). NDIS National Workforce Plan: 2021–2025. https://www.itsanhonour.gov.au/coat-arms/index.cfm

- Bourke, J. A. (2021). The lived experience of interdependence: Support worker relationships and implications for wider rehabilitation. Brain Impairment, https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2021.24

- Bourke, J. A., Nunnerley, J. L., Sullivan, M., & Derrett, S. (2019). Relationships and the transition from spinal units to community for people with a first spinal cord injury: A New Zealand qualitative study. Disability and Health Journal, 12(2), 257–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2018.09.001

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage.

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2021). Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. https://Disability.Royalcommission.Gov.Au/

- Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Social Services). (2019). Growing the NDIS Market and Workforce. https://www.pmc.gov.au/government/its-honour

- Constantinou, C. S., Georgiou, M., & Perdikogianni, M. (2017). A comparative method for themes saturation (CoMeTS) in qualitative interviews. Qualitative Research, 17(5), 571–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116686650

- Douglas, J. M., & Spellacy, F. J. (2000). Correlates of depression in adults with severe traumatic brain injury and their carers. Brain Injury, 14(1), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/026990500120943

- Everhart, D. E., Nicoletta, A. J., Zurlinden, T. M., & Gencarelli, A. M. (2020). Caregiver issues and concerns following TBI: A review of the literature and future directions. Psychological Injury and Law, 13(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12207-019-09369-3

- Fadyl, J., McPherson, K., & Kayes, N. (2011). Perspectives on quality of care for people who experience disability. BMJ Quality and Safety, 20(1), 87–95. http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/20/1/87.full.pdf https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs.2010.042812

- Gridley, K., Brooks, J., & Glendinning, C. (2014). Good practice in social care: The views of people with severe and complex needs and those who support them. Health & Social Care in the Community, 22(6), 588–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12105

- Hewitt, A., & Larson, S. (2007). The direct support workforce in community supports to individuals with developmental disabilities: Issues, implications, and promising pactices. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(2), 178–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20151

- Holloway, M., Orr, D., & Clark-Wilson, J. (2019). Experiences of challenges and support among family members of people with acquired brain injury: A qualitative study in the UK. Brain Injury, 33(4), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2019.1566967

- Iacono, T. (2010). Addressing increasing demands on Australian disability support workers. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 35(4), 290–295. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2010.510795

- Judd, M. J., Dorozenko, K. P., & Breen, L. J. (2017). Workplace stress, burnout and coping: A qualitative study of the experiences of Australian disability support workers. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 1109–1117. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12409

- Knight, R. G., Devereux, R., & Godfrey, H. P. D. (1998). Caring for a family member with a traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 12(6), 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/026990598122430

- Lehan, T., Arango-Lasprilla, J. C., de Los Reyes, C. J., & Quijano, M. C. (2012). The ties that bind: The relationship between caregiver burden and the neuropsychological functioning of TBI survivors. NeuroRehabilitation, 30(1), 87–95. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-2011-0730

- Manskow, U. S., Sigurdardottir, S., Røe, C., Andelic, N., Skandsen, T., Damsgard, E., Elmstahl, S., & Anke, A. (2015). Factors affecting caregiver burden 1 year after severe traumatic brain injury: A prospective nationwide multicenter study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 30(6), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000085

- Martins, B., & Dreyer, P. (2012). Dependence on care experienced by people living with duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal cord injury. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 44(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182477a62

- Mavromaras, K., Moskos, M., Mahuteau, S., Isherwood, L., Goode, A., Walton, H., Smith, L., Wei, Z., & Flavel, J. (2018). Evaluation of the NDIS: A Final Report. February. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/04_2018/ndis_evaluation_consolidated_report_april_2018.pdf

- Mitsch, V., Curtin, M., & Badge, H. (2014). The provision of brain injury rehabilitation services for people living in rural and remote New South Wales, Australia. Brain Injury, 28(12), 1504–1513. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2014.938120

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2022). NDIS Quarterly Report to disability ministers - 2021-2022 Q4.

- National Disability Insurance Scheme Act. (2013). (testimony of Parliament of Australia).

- National Disability Services. (2018). Australian Disability Workforce Report: 2nd edition February 2018. www.carecareers.com.au

- National Disability Services. (2021). State of the Disability Sector Report.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2020). NVivo (No. 12). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home?_ga=2.57117602.966813235.1638426383-1710954617.1638426383

- Rasmussen, M. S., Arango-Lasprilla, J. C., Andelic, N., Nordenmark, T. H., & Soberg, H. L. (2020). Mental health and family functioning in patients and their family members after traumatic brain injury: A cross-sectional study. Brain Sciences, 10(10), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10100670

- Redhead, R. (2010). Supporting adults with an acquired brain injury in the community - a case for specialist training for support workers. Social Care and Neurodisability, 1(3), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.5042/scn.2010.0598

- Robinson, S., Graham, A., Fisher, K. R., Neale, K., Davy, L., Johnson, K., & Hall, E. (2020). Understanding paid support relationships: Possibilities for mutual recognition between young people with disability and their support workers. Disability and Society, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2020.1794797

- Smyth, E., Healy, O., Lydon, S., S, E., H, O., Smyth, E., Healy, O., & Lydon, S. (2015). An analysis of stress, burnout, and work commitment among disability support staff in the UK. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 47, 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.09.023

- Stenberg, M., Stålnacke, B. M., & Saveman, B. I. (2022). Family experiences up to seven years after a severe traumatic brain injury–family interviews. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(4), 608–616. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1774668

- Tam, S., McKay, A., Sloan, S., & Ponsford, J. (2015). The experience of challenging behaviours following severe TBI: A family perspective. Brain Injury, 29(7–8), 813–821. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2015.1005134

- Tate, R. L. (2004). Assessing support needs for people with traumatic brain injury: The care and needs scale (CANS). Brain Injury, 18(5), 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050310001641183

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Topping, M., Douglas, J., & Winkler, D. (2021). General considerations for conducting online qualitative research and practice implications for interviewing people with acquired brain injury. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211019615

- Topping, M., Douglas, J., & Winkler, D. (2022a). Adapting to remote interviewing methods to investigate the factors that influence the quality of paid disability support. Sage Research Methods: Doing Research Online, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529601442

- Topping, M., Douglas, J., & Winkler, D. (2022b). “They treat you like a person, they ask you what you want”: A grounded theory study of quality paid disability support for adults with acquired neurological disability. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2086636

- Topping, M., Douglas, J., & Winkler, D. (2022). Let the people you’re supporting be how you learn”: A grounded theory study on quality support from the perspective of disability support workers. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–13 . https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2148300

- Topping, M., Douglas, J. M., & Winkler, D. (2020). Factors that influence the quality of paid support for adults with acquired neurological disability: Scoping review and thematic synthesis. Disability and Rehabilitation, https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1830190

- UN General Assembly. (2007). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Resolution adopted by the General Assembly, A/RES/61/106. http://www.unhcr.org/refworld/docid/45f973632.htm

- UN General Assembly. (2016). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (Theme: Access to Rights-Based Support for Persons with Disabilities) A/HRC/34/58. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Disability/SRDisabilities/Pages/Reports.aspx

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

Appendix 1.

Participant Interview Schedule

Begin interview by thanking the participant for participating in this study and remind the participant that their participation is voluntary, and they can stop the interview at any time. Give the participant the opportunity to ask questions. Once consent has been re-confirmed verbally, confirm any incomplete items from the demographics form and then use the following questions as an interview guide. Prompt participants as necessary (e.g., tell me more, can you give me an example of a time …) and alter questions and ordering of questions as necessary in line with the participant’s narrative.

Tell me about your close other’s support arrangements and your involvement

What do you think of the quality of support [close other’s name] receives?

Tell me about time/s when your close other received excellent support

Does your close other have (or previously had) any excellent support workers? Can you describe them to me? What makes them excellent?

Tell me about time/s when you feel the support could have been better

What can make it difficult for [close other’s name] to work with support workers?

What do you look for (/value) in a support worker? (If prompts needed e.g., skills, qualities, characteristics, training, experience)

What does the ideal support worker – person with disability relationship look like?

Are there other factors you think influence the quality of support your close other receives? What makes it better / what makes it worse?

How do you think the quality of support could be improved? / or has improved (if it’s got better)?

What advice would you give to a new support worker about how to be an excellent support worker?

What is the most important factor that influences the quality of support?