ABSTRACT

Background: Relational aspects of self-awareness following Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) are increasingly being recognized. However, research underpinning the nature of the association between self-awareness and quality of relationships has yet to be synthesized. Method: Searches, which were completed between February 2022 and February 2023, consisted of combining terms related to ABI, self-awareness, and quality of relationships. Data were analyzed using the Synthesis Without Meta-Analysis (SWiM) approach. Results: Associations between self-awareness and relationship quality across eight studies identified for this review differed in direction and significance. A more consistent pattern emerged, however, when studies assessing the quality of specific types of relationships i.e., spousal (N = 1) and therapeutic (N = 3), were compared to studies assessing the quality of a person’s broader network of relationships (N = 4). In particular, good awareness was positively associated with the quality of specific relationships (r = 0.66) whereas it was negatively associated with the quality of a person’s broader network of relationships (r = −0.35). Conclusion: Results are discussed with consideration given to measures assessing the quality of specific relationships. In particular, such measures may tap into important patterns of interaction between two individuals, such as those related to attunement or communication, which may be valuable preconditions for improving awareness.

Introduction

An Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) is considered as any acute and rapid onset damage to the brain occurring after birth and which is not related to a congenital or degenerative disease. Its aetiology includes, but is not limited to: trauma from events such as road traffic accidents, assaults, falls, or post-surgical damage; issues related to blood or oxygen supply in the brain; toxic or metabolic insult; and infection or other inflammation (Royal College of Physicians and British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine, Citation2003). As one of the leading causes of death and disability around the globe (World Health Organization, Citation2020a, Citation2020b), the social and emotional consequences of ABI may be devastating to those who sustain these injuries as well as to their families and friends (Gorgoraptis et al., Citation2019; Pavlovic et al., Citation2019; Ruet et al., Citation2019).

One of the more challenging consequences of ABI for patients, families, and service providers is impaired self-awareness. That is, knowledge about the self, one’s weaknesses, and problems faced or anticipated (Sansonetti et al., Citation2021). This is a useful summary definition that incorporates the key concepts related to awareness including intellectual awareness (i.e., knowledge of current skills and deficits), online awareness (i.e., knowledge of within-task performance), and psychological denial (see Sansonetti et al., Citation2021 for a review).

Current estimates suggest that impaired awareness, particularly intellectual awareness, occurs in over 30%–50% of cases of ABI (Dromer et al., Citation2021a; Vallat-Azouvi et al., Citation2018) and typically involves the overestimation of abilities (Bivona et al., Citation2019). However, it can also represent individuals who underestimate their abilities as well (Ownsworth et al., Citation2007; Sansonetti et al., Citation2021). Regardless of which end of the spectrum an individual with impaired self-awareness lies, poor outcomes have been documented including reduced independence, reduced emotional and occupational functioning, and reduced quality of life (Belchev et al., Citation2017; Hurst et al., Citation2020; Prigatano & Sherer, Citation2020; Smeets et al., Citation2017). Despite this, those who overestimate their abilities tend to experience better emotional functioning than those who underestimate their abilities (Dromer et al., Citation2021b; Smeets et al., Citation2017), in what some consider to be the buffering effect of overestimation against the emotional fallout of unwanted changes to the sense of self post-ABI (Lloyd et al., Citation2021).

In addition to self-awareness, ABI can also have a negative and enduring impact on the quality of one’s relationships (Rogers & McKinlay, Citation2019; Salas et al., Citation2021). Relationship quality in this regard refers to how a person subjectively experiences and rates the quality of a relationship but it can also refer to the interpersonal patterns of interaction within that relationship, i.e., conflict or communication (Fincham & Rogge, Citation2010). Across both manners of assessing relationship quality, studies have found reduced quality of relationship between couples following ABI (Bodley-Scott & Riley, Citation2015; Brickell et al., Citation2021; Hammond et al., Citation2011; Moreno et al., Citation2013; O’Keeffe et al., Citation2020), a trend which is also observed in other familial relationships, i.e., siblings and children (Perlesz et al., Citation2000). Reduced relationship quality, in turn, has been found to reduce overall life satisfaction (Johnson et al., Citation2010) and rehabilitation outcomes post-ABI (Backhaus et al., Citation2016; Backhaus et al., Citation2019; Godwin et al., Citation2011). This is despite the pivotal role that strong interpersonal relationships play in recovering from an ABI (Maggio et al., Citation2018), as captured in Bowen et al. (Citation2018)’s relational approach to rehabilitation. The importance of strong therapeutic relationships has also long been recognized in the field of neurorehabilitation (Bowen et al., Citation2018; Stagg et al., Citation2019), with several studies linking strong working alliances to improvements in treatment completion, employment outcomes, depressive symptoms, and family discord (Evans et al., Citation2008; Lustig et al., Citation2003; Rowlands et al., Citation2020; Williams & Douglas, Citation2022).

Linking the areas of self-awareness and interpersonal relationships post-ABI, several studies have found impaired awareness to be associated with a number of aspects of family experience, including family member distress (Prigatano et al., Citation2005), depressive symptoms of “close others” (Richardson et al., Citation2015), and caregiver burden (Chesnel et al., Citation2018; Rubin et al., Citation2020). Self-awareness has also been linked to therapeutic alliance, with awareness thought to influence the strength and quality of interpersonal relationships that can be formed (Stagg et al., Citation2019). However, stronger quality relationships are also considered to help individuals to confront, understand, and accept injury-related impairments (Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000), in what may be a bi-directional association between the two constructs.

Examining this association between awareness and quality of relationships, Yeates et al. (Citation2007) interviewed individuals with impaired self-awareness following ABI and their relatives. They found that certain interpersonal aspects of close relationships such as mutual feelings of tension or anxiety can perpetuate unawareness. In particular, based on their findings they hypothesized that the distress experienced by relatives in the aftermath of an ABI may lead them to adopt a disempowering position in the relationship in which they view the injured person as lacking autonomy. This can, in turn, be met by the injured person with stronger attempts to orient their relative to their abilities. The outcome of this, however, may be further anxiety in the relative, further tension in the relationship, and, as a result, further unawareness in the individual with ABI.

However, to the authors’ knowledge, no systematic review has brought together research exploring the nature of the association between self-awareness and interpersonal relationships post-ABI. The authors of this current systematic review will therefore attempt to bring together the abovementioned perspectives on self-awareness and relationships to consider for the first time how the quality of any of a person’s close relationships can influence or be influenced by their ability to recognize and accept changes. Specifically, this systematic review will address the following research questions: (1) is there an association between perceptions of relationship quality and self-awareness following ABI and (2) what is the nature of this association?

Method

This systematic review was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022261608). It was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., Citation2021) and its extension Synthesis Without Meta-analysis (SWiM) (Campbell et al., Citation2020).

Search strategy

An extensive search strategy was developed for this review for searching the following databases: AMED, APA PsycINFO, CINAHL Complete, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science. Specifically, a range of terms related to ABI, self-awareness, and quality of relationships were combined using the Boolean operator “AND”. See Appendix A in the supplementary material for the full search strategy which was applied systematically to each database from the date of database inception to February 2022. Searches were then re-run in June 2022 and again in February 2023 to identify any additional relevant papers.

Eligibility criteria

Only studies published in peer-reviewed journals and which were available in the English language were included in this review. Where full texts were unavailable, the relevant authors were contacted before excluding the study. Studies on progressive neurological disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders were excluded as well as studies on impaired awareness, the root of which was conditions other than ABI, i.e., mental health conditions such as schizophrenia. Studies with participants recruited in childhood (i.e., ≤ 17 years of age) were also excluded. Each study was required to include a measure of self-awareness in the individual with ABI, whether it measured intellectual awareness, online awareness, or psychological denial. Studies were also required to include a self or other-rated measure of relationship quality related to the individual with ABI, be it a specific relationship of theirs or their interpersonal relationships more generally. Finally, papers were excluded if they had fewer than three participants or if they were a conference proceeding, clinical practice guideline, opinion piece, commentary, book, book chapter, protocol, or a review article.

Study selection

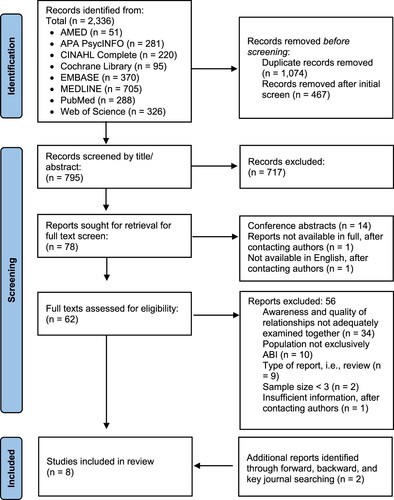

Search results were exported to EndNote where duplicates were removed following Bramer et al. (Citation2016)’s deduplication process. At this stage, titles and citations were reviewed by one reviewer to screen out inappropriate studies emanating from grey literature sources or from biomedical research or related fields. Following this, the inclusion and exclusion criteria were systematically applied to all remaining studies to screen titles and abstracts. This was completed by two reviewers (CMcC and ND) who were blinded to each other’s decisions. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or, if consensus could not be reached, through consultation with a 3rd reviewer (DGF). For studies meeting the inclusion criteria or where adherence to the criteria was unclear, full texts were retrieved and reviewed. Again, this was completed by the two reviewers using the same process as before. After selecting studies for synthesis in this manner, key journals which featured those studies were searched for additional papers. Forward and backward searching of these selected studies was then performed on Web of Science to further supplement the overall search (see ).

Data extraction

Data extraction from selected studies was carried out by CMcC and checked by ND. The following data was extracted and tabulated: author(s), year of publication, title, design, country, aim(s), hypotheses, funding sources, conflicts of interest declared, setting, participant characteristics, control group(s), inclusion and exclusion criteria, methods used (including measure of self-awareness and quality of relationships), any interventions/exposures, method of analysis, main findings, and any limitations described. In the event of missing information or information that was not sufficiently reported, the relevant authors were contacted to request this information.

Quality assessment

Selected studies were quality assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Citation2018). This instrument was chosen as it allows the quality of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies to be assessed according to the individual design of a study. It relies on two screening questions in the first instance which both must be passed in order for a study to be considered. These screening questions ask about the clarity of a study’s research questions and the suitability of their data to address those questions. These items are rated according to the following response categories: “Yes,” “No,” or “Can’t tell.” If a study passes the screening questions, five criteria are then used to rate the quality of the study according to its design type using the same three response categories as before. The developers of the MMAT discourage the calculation of an overall score from these criterion ratings, and instead recommend a presentation of the ratings of each criterion to better inform the quality of the studies included in the review (Hong et al., Citation2018).

The MMAT was completed independently by CMcC and ND who were blinded to each other’s decisions. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or consultation with the 3rd reviewer (DGF). Importantly, no study was excluded from this review on the basis of methodological quality.

In addition to the MMAT, the Outcome Reporting Bias in Trials (ORBIT I) classification tool (Kirkham et al., Citation2010; Saini et al., Citation2014) was used in the same manner as the MMAT to help determine risk of bias with regard to studies selectively reporting specific outcomes. The ORBIT I classifications were made in this review with respect to all outcome(s) of interest to this review within a study, not just those reported sufficiently to be included in the synthesis. See Appendix B in the supplementary material for a description of the nine classifications, A-I, that could be given to a study classifying it as high risk, low risk, or no risk of bias with regards to selective reporting.

Finally, the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach was used. This classifies certainty of evidence in a review as very low, low, moderate, or high (Guyatt et al., Citation2011). Considering randomized studies to automatically provide high certainty of evidence and observational studies to automatically provide low certainty of evidence (Higgins et al., Citation2019), the lowering of the GRADE rating was considered if risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, or publication of bias was present. Conversely, the rating could be raised if there were large effects, dose responses, or the consideration of plausible residual confounders.

Strategy for data synthesis

Although studies of any design could be included in this review, each included study was quantitative in nature. As a result, the method of synthesis followed the SWiM method (Campbell et al., Citation2020; Higgins et al., Citation2019). This method was undertaken as meta-analysis was not possible due to too few studies being included in the review as well as observed clinical heterogeneity between studies with regards to their outcomes. Furthermore, effect directions differed considerably between studies. As such, effect estimate summary statistics and bubble plots were instead produced; a method of synthesis that was further supplemented by vote counting the direction of effects. The vote counting method used in this review followed that of Boon and Thomson (Citation2021) with effect direction plots developed to aid in interpretation. Further aiding interpretation was the use of the Sign Test which helped determine how statistically significant the different effect directions were between self-awareness and relationship quality. GraphPad (Citationn.d) was used to complete this two-tailed Sign Test.

Prior to this manner of synthesis, study characteristics were described narratively and tabularly, ordering the tables alphabetically by first author. As each study included in this review contributed to the synthesis based on non-arbitrary decision-making by the reviewers, sensitivity analyses were not necessary (Higgins et al., Citation2019).

Results

Search outcome

Searches of the chosen databases resulted in the detection of 1,980 papers until February 2022 and an additional 356 papers until February 2023 (see ). Following the removal of 1,074 duplicates, 1,262 studies were screened by title and/or abstract, as described previously. This resulted in 78 studies being sought for retrieval. Fourteen of these were conference abstracts, one was not available in full, and one was not available in English after contacting the authors. As such, 62 papers were ultimately screened by their full texts. The main reasons for excluding studies at this stage were: self-awareness and quality of relationships not adequately studied in relation to one another (n = 34), a non-ABI exclusive sample (n = 10), the type of article (n = 9), a sample size of < 3 (n = 2), or insufficient information regarding the age range of participants after contacting the authors (n = 1). This process resulted in the identification of six studies which met the inclusion criteria of this review. A further two studies were identified through forward and backward reference searching which was undertaken in May 2022 and again in February 2023, and together yielded a total of 8 studies for synthesis.

Study characteristics

The eight included studies comprised a total of 355 separate participants with ABI (Burridge et al., Citation2007; Hurst et al., Citation2020; Neal & Greenwald, Citation2022; Pettemeridou et al., Citation2020; Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022; Sasse et al., Citation2013; Schönberger et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b). These studies, which were published between 2006 and 2022, originated from western countries such as Cyprus (N = 2), Denmark (N = 2), the UK (N = 1), Australia (N = 1), Germany (N = 1), and the USA (N = 1). Although no restrictions were placed on studies for their research design, each of the eight papers in this review were quantitative (see for more characteristics). Using the MMAT to categorize study design (see ), four of the studies were considered to be analytical cross-sectional studies due to their use of control groups (Burridge et al., Citation2007; Hurst et al., Citation2020; Pettemeridou et al., Citation2020; Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022). There were also two before-after time series design studies (Schönberger et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b) and the two remaining studies were descriptive cross-sectional (Neal & Greenwald, Citation2022; Sasse et al., Citation2013).

Table 1. Characteristics of studies organized alphabetically by first author.

In terms of the age of participants, this was inconsistently reported. While most studies reported the mean and standard deviation (SD) of their sample’s age, only five studies specified participants’ age range in their inclusion criteria and/or in their description of participants. The three studies in this review which did not report this information were included on the basis that they cited their sample as an adult sample. During full-text screening and after contacting the authors, one study was excluded from this review on the basis of insufficient information relating to the age range of participants. With regard to sex, all eight studies reported a predominantly male sample (see ).

ABI characteristics

All but two studies in this review (Burridge et al., Citation2007; Neal & Greenwald, Citation2022) specified the exact types of brain injuries their participants had experienced. These included: various types of road traffic, workplace, and sporting accidents; falls; assaults; objects falling; stroke; tumours; infections; and anoxia. With regard to the severity of these injuries, one study recruited only severe brain injuries (Hurst et al., Citation2020) while others either did not report this or focused additionally on moderate and milder severities as well. See Appendix C in the supplementary material for more information.

Assessment of self-awareness

Self-awareness was measured across each of the eight studies in a variety of different ways (see ). Two of the studies used therapist ratings of self-awareness from a four-item scale derived from Fleming et al. (Citation1996); (Schönberger et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b). The remaining six studies enlisted the use of self and informant discrepancy scores from psychometric tools such as the Socio-Emotional Questionnaire (Bramham et al., Citation2002), the Patient Competency Rating Scale (Borgaro & Prigatano, Citation2003; Kolakowsky-Hayner, Citation2010), the Dysexecutive Questionnaire Revised (DEX-R; Dimitriadou et al., Citation2018), and the Awareness Questionnaire (Sherer et al., Citation1995). The two studies by Pettemeridou et al. (Citation2020) and Pettemeridou and Constantinidou (Citation2022) additionally used the Self-Regulation Skills Interview to measure awareness (Ownsworth et al., Citation2000). Finally, this study by Pettemeridou and Constantinidou (Citation2022) also used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and brain volume in awareness-related regions-of-interest (ROIs) as a measure of awareness. ROIs were taken from Neurosynth.org (Yarkoni et al., Citation2011) where 903 studies of self-concept were meta-analyzed to create a brain map of awareness-related ROIs. In this study, ROIs most associated with their psychometric measures of awareness were the temporal cortex, cingulate cortex, and temporal pole (Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022).

Table 2. Association between self-awareness and quality of relationships organized alphabetically by first author.

Assessment of quality of relationships

In terms of quality of relationships, the types of relationships assessed varied across spousal (N = 1), therapeutic (N = 3), and general relationships (N = 4; See ). General relationships here refer to studies where the quality of a person’s broad network of social and interpersonal relationships were collectively assessed while studies that measured spousal and therapeutic relationships specifically are referred to hereafter as studies which explored specific types of relationships. Regarding the manner in which general relationships were assessed, one study used the Tate et al. (Citation1999) informant-rated Sydney Psychosocial Reintegration Scale (Hurst et al., Citation2020). Three studies, Sasse et al. (Citation2013), Pettemeridou and Constantinidou (Citation2022), and Pettemeridou et al. (Citation2020), used the Quality of Life after Brain Injury scale (QOLIBRI) (Von Steinbüchel et al., Citation2010; Von Steinbuechel et al., Citation2012) which includes a measure of the quality of a patient’s social relationships. Pettemeridou and Constantinidou (Citation2022) and Pettemeridou et al. (Citation2020) additionally used the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument-BREF (WHOQoL Group, Citation1993). The remaining four studies in this review explored the quality of a specific type of interpersonal relationship. In particular, the Working Alliance Inventory (Horvath & Greenberg, Citation1989) was used to measure therapeutic relationships (Neal & Greenwald, Citation2022; Schönberger et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b) and the Relationship Questionnaire was used to measure spousal relationship satisfaction (Burridge et al., Citation2007). This Relationship Questionnaire was a 10-item tool derived from a paper by Rust et al. (Citation1988).

Quality assessment

For all eight studies included in this review, there were clear research questions and objectives. As the studies varied across MMAT design categories, the remaining items were rated according to each study’s individual and specific design (see ). Overall, two of the six non-randomized studies (Hurst et al., Citation2020; Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022) as well as one of the descriptive cross-sectional studies (Sasse et al., Citation2013) achieved perfect MMAT ratings. These ratings reflect aspects of each study including participants being considered representative of the target population, appropriate measures being used, complete outcome data available, confounders or covariates being considered, appropriate sampling strategies being used, low risk of non-response, and/or appropriate analysis techniques. Common reasons why the remaining studies did not achieve higher ratings related to their having incomplete data or reporting insufficient information to make that determination. Some studies also failed to acknowledge or account for potential confounders or covariates in their research design and some did not employ the use of standardized psychometric measures.

Table 3. Quality assessment.

With regards to selective non-reporting, displays the ORBIT I classifications assigned to each study based on their reporting of all outcomes of potential interest to this review. The results of this risk of bias assessment were such that two studies were considered high risk due to the results of some analyses of interest only being reported for outcomes that were statistically significant (Burridge et al., Citation2007; Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022). One study was considered low risk, on the other hand, due to insufficient information being available in order to consider the results fully tabularized (Schönberger et al., Citation2006a). No reporting bias was identified in any of the five remaining studies.

Synthesis

The primary research questions of this review were: (1) is there an association between perceptions of relationship quality and self-awareness following ABI and (2) what is the nature of that association? To address the first research question, associations reported in the seven applicable studies were inspected for significance. From this, it was found that four of the seven studies showed a significant association between their respective measures of self-awareness and quality of relationships (see ; Burridge et al., Citation2007; Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022; Sasse et al., Citation2013; Schönberger et al., Citation2006b). However, Sasse et al. (Citation2013) reported that their association did not remain significant after using a Bonferroni adjusted alpha level. In addition, an association between self-awareness and quality of relationships was supported in the one remaining study by Schönberger et al. (Citation2006a) whose significant correlations between participants’ report of injury-related problems and working alliance did not remain significant when self-awareness was included in the analysis. The conclusion drawn, therefore, was that participants who self-reported high levels of injury-related problems had significantly greater therapeutic relationships but only when their ability to self-report problems was a sign of good awareness.

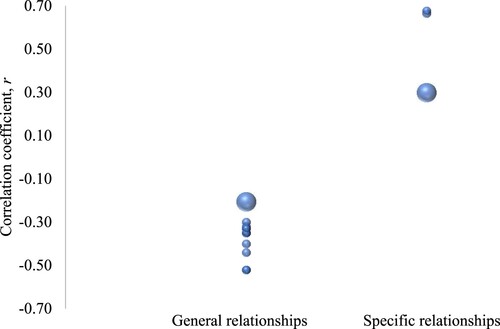

Next, the strength of significant associations was explored by way of summarizing significant effect estimates. As Schönberger et al. (Citation2006a) did not report sufficient results (see ), it was not included in this part of the synthesis. Furthermore, there was a slight trend observed in which the significant associations found in studies measuring general relationships were negative whereas the significant associations found in studies that measured the quality of specific types of relationships were positive. Negative associations here refer to associations in which good awareness is related to poor-quality relationships while positive associations refer to associations in which good awareness is related to strong-quality relationships. As such, summary statistics were produced separately for studies measuring general vs specific types of relationships.

In sum, the median correlation coefficient, r, for significant associations that measured general relationships was −0.35 (interquartile range −0.33 to −0.42). On the other hand, the median coefficient, r, for significant associations that measured the quality of specific types of relationships was 0.66 (interquartile range 0.3–0.68). A visual representation of the range and distribution of these effects is shown in . Overall, the general relationships effect estimate was moderate in strength while the effect estimate when specific relationships were assessed was large (Cohen, Citation1988).

Figure 2. Bubble plot of effect estimates for significant associations.

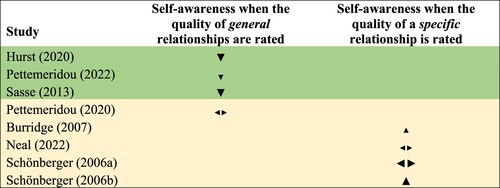

Next, the direction of the majority of effects (positive or negative associations) for each study was explored and plotted in . In accordance with Boon and Thomson (Citation2021), the majority of effects within each study was considered as the number of effects consistently trending in the same direction ≥70% of the time.

Figure 3. Effect direction plot summarizing direction of the associations between self-awareness and relationship quality.

Similar to that shown in , clarifies that for the four studies measuring the quality of general relationships, three reported consistent effect directions, each of which described negative associations exclusively, i.e., good awareness being related to poor quality relationships (Hurst et al., Citation2020; Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022; Sasse et al., Citation2013). For the four studies measuring the quality of specific relationships, on the other hand, two reported consistent effect directions and described positive associations exclusively, i.e., good awareness being related to strong quality relationships (Burridge et al., Citation2007; Schönberger et al., Citation2006b). These two studies measured the quality of spousal and therapeutic relationships, respectively, although their slightly lower quality, as assessed on the MMAT, is noted here. In addition, a Sign Test was carried out to examine the significance of the different effect directions between self-awareness and relationship quality for the five studies which reported consistent effect directions. This test was not statistically significant (p = 1), suggesting no significant difference in the effect directions between studies that explored general vs specific types of relationships.

Certainty of evidence

Finally, the GRADE approach was used to evaluate certainty of evidence in the observed associations between self-awareness and quality of relationships across subgroups measuring specific vs general relationship. As none of the studies in this review were randomized, a low certainty of evidence rating was automatically given and this rating was subsequently lowered due to risk of reporting bias and imprecision. In other words, our confidence in the summary effect estimates for the two groups is very low and so, the true effect is likely to be substantially different due to the quality of evidence overall (Higgins et al., Citation2019).

Discussion

This is the first known systematic review to have synthesized peer-reviewed data examining the nature of the association between self-awareness and quality of relationships following ABI. Having identified eight relevant studies through the systematic searching of scientific databases, several different associations were found between the quality of one’s relationships and self-awareness post-ABI. However, less than half of these associations were statistically significant and the direction in which they trended was inconsistent across studies.

There are several possible reasons for inconsistencies in the significance and direction of effects across studies. Firstly, there was variability across studies with regard to measuring awareness, with five studies using patient-proxy discrepancies, two using clinician-rated scales, and one using brain volume in awareness-related ROIs. This may have introduced variability as proxies can be biased due to their own denial, affect, or misjudgement (Mahoney et al., Citation2019). Clinicians, on the other hand, may not always have sufficient opportunities to observe the range of client abilities referred to in questionnaires. Furthermore, the validity of using brain volume to indicate awareness functioning is unclear as specific causal relationships cannot be explicitly inferred from its correlation with other metrics of awareness (Kalin, Citation2021). Secondly, research shows that injury-specific variables such as cognitive functioning (Villalobos et al., Citation2021), time since injury (Richardson et al., Citation2014), and injury severity (Dromer et al., Citation2021b) can influence awareness, variables which were not consistently considered in the results synthesized in this review.

In addition, studies differed with regard to how relationship quality was assessed with four studies relying on self-report, one relying on informant-report, and three using both. This introduces variability where self-report may be influenced by the injury-related factors described previously. Informants, on the other hand, may not possess the necessary knowledge to comment on the quality of their relatives’ network of relationships (Aza et al., Citation2022).

There was also variability with regard to the types of relationships explored in this review with three studies examining therapeutic relationships, one examining spousal relationships, and four examining the quality of a person’s broader network of relationships (i.e., relationship quality not specific to any one relationship but to a broader network of individuals in a person’s life). However, when studies were grouped according to whether they explored a specific type of relationship (i.e., therapeutic or spousal) or whether they explored the person’s broader network of interpersonal relationships more generally, a more consistent pattern emerged.

In particular, when the quality of social relationships more generally was assessed, relationship quality was found to be higher in those with more impaired self-awareness; an association of moderate strength (Cohen, Citation1988). This is consistent with much of the existing research suggesting that impaired self-awareness buffers against many of the negative experiences one faces after an ABI (Lloyd et al., Citation2021), not least of which could include the emotional consequences of general relationship breakdown. It remains unclear, however, if individuals in these situations simply underreport relationship difficulties due to impaired self-awareness (Ownsworth et al., Citation2006). It is also possible that their relationships are genuinely stronger because their impaired awareness buffers against the breakdown of relationships in a manner that is akin to how impaired self-awareness buffers against the overall emotional consequences of an ABI (Dromer et al., Citation2021b).

In contrast, studies in this review which assessed the quality of more specific types of relationships (i.e., spousal and therapeutic), found positive associations such that better self-awareness was associated with higher quality relationships and vice versa for poorer self-awareness; an association that was large in effect size (Cohen, Citation1988). This is consistent with other studies which have found impaired awareness to be associated with significantly poorer injury-related relationship outcomes, including significant changes to the quality of spousal and familial relationships as well as friendships (Geytenbeek et al., Citation2017). One possible reason for this finding is that better awareness may allow for more open and honest communication between individuals following ABI which may allow for better quality relationships to be formed or maintained (Stagg et al., Citation2019). Alternatively, it is possible that better quality relationships provide a safe relational space in which ABI-related difficulties may be confronted and processed by an individual (Schönberger et al., Citation2006a). This is in keeping with recent relational approaches to self-awareness post-ABI as part of which strong interpersonal relationships are thought to act as catalysts for improving self-awareness (Bowen et al., Citation2018). This is related to the increasing recognition that brain injuries occur not only inside the skull of one individual but also in the relational space between that individual and those around them (Bowen et al., Citation2018; Salas, Citation2021). Perhaps Freed (Citation2002) captures this best with the idea that the connection and attunement between two individuals helps provide essential auxiliary functions to a person following ABI, such as those related to cognition and emotional regulation.

It would therefore seem reasonable to hypothesize that where conditions for connection and attunement are met between two individuals, the non-injured person may provide important auxiliary functions to the person with ABI beyond those that were just mentioned. Perhaps the relational space between two individuals provides important functions related to the self-awareness of the injured person. Indeed, self-awareness is increasingly considered to be the product of a dynamic process involving both intrapersonal and interpersonal components (Bowen et al., Citation2018). It would also follow then that auxiliary functions related to self-awareness served by an individual close to the injured person would only be tapped into by certain studies. Those studies being ones which consider the quality of that specific relationship rather than studies exploring the quality of the person’s broader network of interpersonal relationships more generally. This is an idea that is supported by the findings of this review and has implications for increasing the extent to which the broader relational environment is prioritized in neurorehabilitation settings. It also adds support to clinical interventions emphasizing strong quality therapeutic relationships in improving awareness deficits (Dirette, Citation2010; Sherer & Fleming, Citation2018).

However, given the limited number of studies in this review overall, it is important to consider the quality of the individual studies contributing to these findings and the overall certainty of evidence. Whilst the quality and level of reporting bias was mixed across studies, the higher MMAT ratings assigned to studies which assessed general relationships should be noted, ratings mostly attributed to their use of standardized psychometric tools as well as their lack of missing data points (Hurst et al., Citation2020; Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022; Sasse et al., Citation2013). Despite this, the group of studies measuring general relationships as well as the group of studies measuring specific relationships both contained one study deemed to be at a high risk of reporting bias (Burridge et al., Citation2007; Pettemeridou & Constantinidou, Citation2022). This, in combination with the lack of significant difference in the direction of effects between both groups as well as the very low certainty of evidence, means that the findings of this review should be considered tentatively. However, it should be noted that the test of significant difference between groups is, itself, potentially underpowered (Higgins et al., Citation2019).

Nevertheless, the tentative findings of this review provide direction for future research. In particular, research should consider the impact of injury-specific factors, such as the degree of cognitive impairment, on any association between awareness and the quality of specific types of relationships given its potential role on both the quality of relationships that can be formed and on awareness levels (Stagg et al., Citation2019; Villalobos et al., Citation2021). It would also be important to select measures of relationship quality that tap into the specific patterns of interactions relevant to that relationship. For example, therapeutic relationship measures should tap into the collaboration, bond, and level of agreement that comprises a strong therapeutic relationship (Bordin, Citation1979), i.e., the WAI (Hatcher & Gillaspy, Citation2006) or the Scale to Assess Therapeutic Relationship (STAR; McGuire-Snieckus et al., Citation2007). The Relationship Quality Scale (Chonody et al., Citation2018) may also be a useful measure of romantic relationships as it taps into the commitment and shared enjoyment or companionship between two people.

Limitations

While the current systematic review used a comprehensive evidence-based approach to the data with thorough and transparent assessments of bias, there are some limitations. Namely, it was not possible to undertake a meta-analysis due to clinical heterogeneity among the identified studies and due to the limited number of relevant studies overall. In addition, given the variability in terminology used to describe the constructs of interest to this review, and despite the meticulous search strategy employed, we cannot rule out the possibility that some relevant articles may have been missed. Finally, the variety of different methods and psychometric tools used to assess the constructs of interest in the eight identified studies presents additional challenges for systematic review as well as the fact that all eight studies were from western nations. So, we cannot rule out the possibility that findings may not generalize to non-western nations.

Conclusion

This is the first known systematic review to have brought together research exploring the nature of the association between self-awareness and quality of relationships following ABI. Although studies were of mixed quality with inconsistent findings overall, one interesting pattern emerged when the specific types of relationships being studied were considered. In summary, better self-awareness was associated with higher quality relationships when the quality of very specific and close relationships were examined. In contrast, when the quality of a person’s broader network of interpersonal relationships was considered, better self-awareness was associated with poorer quality relationships. Potential reasons for this have been discussed with regard to current literature in the field.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.1 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aza, A., Verdugo, M. Á., Orgaz, M. B., Andelic, N., Fernández, M., & Forslund, M. V. (2022). The predictors of proxy- and self-reported quality of life among individuals with acquired brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(8), 1333–1345. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1803426

- Backhaus, S., Neumann, D., Parrot, D., Hammond, F. M., Brownson, C., & Malec, J. (2016). Examination of an intervention to enhance relationship satisfaction after brain injury: A feasibility study. Brain Injury, 30(8), 975–985. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2016.1147601

- Backhaus, S., Neumann, D., Parrott, D., Hammond, F. M., Brownson, C., & Malec, J. (2019). Investigation of a new couples intervention for individuals with brain injury: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(2), 195–204.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.08.174

- Belchev, Z., Levy, N., Berman, I., Levinzon, H., Hoofien, D., & Gilboa, A. (2017). Psychological traits predict impaired awareness of deficits independently of neuropsychological factors in chronic traumatic brain injury. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(3), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12134

- Bivona, U., Costa, A., Contrada, M., Silvestro, D., Azicnuda, E., Aloisi, M., Catania, G., Ciurli, P., Guariglia, C., & Caltagirone, C. (2019). Depression, apathy and impaired self-awareness following severe traumatic brain injury: A preliminary investigation. Brain Injury, 33(9), 1245–1256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2019.1641225

- Bodley-Scott, S. E., & Riley, G. A. (2015). How partners experience personality change after traumatic brain injury – Its impact on their emotions and their relationship. Brain Impairment, 16(3), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2015.22

- Boon, M. H., & Thomson, H. (2021). The effect direction plot revisited: Application of the 2019 Cochrane handbook guidance on alternative synthesis methods. Research Synthesis Methods, 12(1), 29–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1458

- Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085885

- Borgaro, S. R., & Prigatano, G. P. (2003). Modification of the Patient Competency Rating Scale for use on an acute neurorehabilitation unit: The PCRS-NR. Brain Injury, 17(10), 847–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/0269905031000089350

- Bowen, C., Palmer, S., & Yeates, G. (2018). A relational approach to rehabilitation: Thinking about relationships after brain injury. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429471483

- Bramer, W. M., Giustini, D., de Jonge, G. B., Holland, L., & Bekhuis, T. (2016). De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association: JMLA, 104(3), 240. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014

- Bramham, J., Morris, R. G., Hornak, J., & Rolls, E. T. (2002, March 25–26). The socio-emotional questionnaire. Rotman Research Institute 12th Annual Conference, Toronto, Canada.

- Brickell, T. A., French, L. M., Varbedian, N. V., Sewell, J. M., Schiefelbein, F. C., Wright, M. M., & Lange, R. T. (2021). Relationship satisfaction among spouse caregivers of service members and veterans with comorbid mild traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder. Family Process, 61(4), 1525–1540. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12731

- Burridge, A. C., Huw Williams, W., Yates, P. J., Harris, A., & Ward, C. (2007). Spousal relationship satisfaction following acquired brain injury: The role of insight and socio-emotional skill. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 17(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010500505070

- Campbell, M., McKenzie, J. E., Sowden, A., Katikireddi, S. V., Brennan, S. E., Ellis, S., Hartmann-Boyce, J., Ryan, R., Shepperd, S., & Thomas, J. (2020). Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ, 368, l6890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890

- Chesnel, C., Jourdan, C., Bayen, E., Ghout, I., Darnoux, E., Azerad, S., Charanton, J., Aegerter, P., Pradat-Diehl, P., & Ruet, A. (2018). Self-awareness four years after severe traumatic brain injury: Discordance between the patient’s and relative’s complaints. Results from the PariS-TBI study. Clinical Rehabilitation, 32(5), 692–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517734294

- Chonody, J. M., Gabb, J., Killian, M., & Dunk-West, P. (2018). Measuring relationship quality in an international study: Exploratory and confirmatory factor validity. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(8), 920–930. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516631120

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

- Dimitriadou, M., Michaelides, M. P., Bateman, A., & Constantinidou, F. (2018). Measurement of everyday dysexecutive symptoms in normal aging with the Greek version of the dysexecutive questionnaire-revised. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(6), 1024–1043. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2018.1543127

- Dirette, D. (2010). Self-awareness enhancement through learning and function (SELF): A theoretically based guideline for practice. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(7), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12759925544344

- Dromer, E., Kheloufi, L., & Azouvi, P. (2021a). Impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Part 1: Assessment, clinical aspects and recovery. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 64(5), 101468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2020.101468

- Dromer, E., Kheloufi, L., & Azouvi, P. (2021b). Impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Part 2. Consequences and predictors of poor self-awareness. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 64(5), 101542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101542

- Evans, C. C., Sherer, M., Nakase-Richardson, R., Mani, T., & Irby, J. W., Jr. (2008). Evaluation of an interdisciplinary team intervention to improve therapeutic alliance in post–acute brain injury rehabilitation. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 23(5), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HTR.0000336845.06704.bc

- Fincham, F. D., & Rogge, R. (2010). Understanding relationship quality: Theoretical challenges and new tools for assessment. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 2(4), 227–242. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00059.x

- Fleming, J. M., Strong, J., & Ashton, R. (1996). Self-awareness of deficits in adults with traumatic brain injury: How best to measure? Brain Injury, 10(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/026990596124674

- Freed, P. (2002). Meeting of the minds: Ego reintegration after traumatic brain injury. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 66(1), 61. https://doi.org/10.1521/bumc.66.1.61.23375

- Geytenbeek, M., Fleming, J., Doig, E., & Ownsworth, T. (2017). The occurrence of early impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury and its relationship with emotional distress and psychosocial functioning. Brain Injury, 31(13-14), 1791–1798. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1346297

- Godwin, E. E., Kreutzer, J. S., Arango-Lasprilla, J. C., & Lehan, T. J. (2011). Marriage after brain injury: Review, analysis, and research recommendations. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 26(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182048f54

- Gorgoraptis, N., Zaw-Linn, J., Feeney, C., Tenorio-Jimenez, C., Niemi, M., Malik, A., Ham, T., Goldstone, A. P., & Sharp, D. J. (2019). Cognitive impairment and health-related quality of life following traumatic brain injury. Neurorehabilitation, 44(3), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-182618

- GraphPad. (n.d). Sign and binomial test. Retrieved May 14, 2022, from https://www.graphpad.com/quickcalcs/binomial1/

- Guyatt, G., Oxman, A. D., Akl, E. A., Kunz, R., Vist, G., Brozek, J., Norris, S., Falck-Ytter, Y., Glasziou, P., & DeBeer, H. (2011). GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction—GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(4), 383–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026

- Hammond, F. M., Davis, C. S., Whiteside, O. Y., Philbrick, P., & Hirsch, M. A. (2011). Marital adjustment and stability following traumatic brain injury: A pilot qualitative analysis of spouse perspectives. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 26(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e318205174d

- Hatcher, R. L., & Gillaspy, J. A. (2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16(1), 12–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503300500352500

- Higgins, J. P., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M. J., & Welch, V. A. (2019). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (2nd ed.). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119536604

- Hong, Q. N., Gonzalez-Reyes, A., & Pluye, P. (2018). Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(3), 459–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.12884

- Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the working alliance inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36(2), 223. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.36.2.223

- Hurst, F. G., Ownsworth, T., Beadle, E., Shum, D. H., & Fleming, J. (2020). Domain-specific deficits in self-awareness and relationship to psychosocial outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(5), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1504993

- Johnson, C. L., Resch, J. A., Elliott, T. R., Villarreal, V., Kwok, O.-M., Berry, J. W., & Underhill, A. T. (2010). Family satisfaction predicts life satisfaction trajectories over the first 5 years after traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(2), 180. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019480

- Kalin, N. H. (2021). Understanding the value and limitations of MRI neuroimaging in psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(8), 673–676. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21060616

- Kirkham, J. J., Dwan, K. M., Altman, D. G., Gamble, C., Dodd, S., Smyth, R., & Williamson, P. R. (2010). The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ, 340, c365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c365

- Kolakowsky-Hayner, S. (2010). The patient competency rating scale. The Center for Outcome Measurement in Brain Injury. Retrieved 4 August 2022, from www.tbims.org/combi/pcrs

- Lloyd, O., Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., Jackson, M., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. (2021). Impaired self-awareness after pediatric traumatic brain injury: Protective factor or liability? Journal of Neurotrauma, 38(5), 616–627. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2020.7191

- Lustig, D. C., Strauser, D. R., Weems, G. H., Donnell, C. M., & Smith, L. D. (2003). Traumatic brain injury and rehabilitation outcomes: Does the working alliance make a difference? Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 34(4), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1891/0047-2220.34.4.30

- Maggio, M. G., De Luca, R., Torrisi, M., De Cola, M. C., Buda, A., Rosano, M., Visani, E., Pidalà, A., Bramanti, P., & Calabrò, R. S. (2018). Is there a correlation between family functioning and functional recovery in patients with acquired brain injury? An exploratory study. Applied Nursing Research, 41, 11–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2018.03.005

- Mahoney, D., Gutman, S. A., & Gillen, G. (2019). A scoping review of self-awareness instruments for acquired brain injury. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 7(2), 3. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1529

- McGuire-Snieckus, R., McCabe, R., Catty, J., Hansson, L., & Priebe, S. (2007). A new scale to assess the therapeutic relationship in community mental health care: STAR. Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706009299

- Moreno, J. A., Arango Lasprilla, J. C., Gan, C., & McKerral, M. (2013). Sexuality after traumatic brain injury: A critical review. Neurorehabilitation, 32(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-130824

- Neal, J. W., & Greenwald, M. (2022). Self-Awareness and therapeutic alliance in speech-language treatment of traumatic brain injury. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2123041

- O’Keeffe, F., Dunne, J., Nolan, M., Cogley, C., & Davenport, J. (2020). “The things that people can’t see” The impact of TBI on relationships: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Brain Injury, 34(4), 496–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1725641

- Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., Strong, J., Radel, M., Chan, W., & Clare, L. (2007). Awareness typologies, long-term emotional adjustment and psychosocial outcomes following acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 17(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010600615506

- Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J. M., & Hardwick, S. (2006). Symptom reporting and associations with compensation status, self-awareness, causal attributions, and emotional wellbeing following traumatic brain injury. Brain Impairment, 7(2), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1375/brim.7.2.95

- Ownsworth, T. L., McFarland, K., & Young, R. M. (2000). Development and standardization of the self-regulation skills interview (SRSI): A new clinical assessment tool for acquired brain injury. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 14(1), 76–92. https://doi.org/10.1076/1385-4046(200002)14:1;1-8;FT076

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., & Brennan, S. E. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88, 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

- Pavlovic, D., Pekic, S., Stojanovic, M., & Popovic, V. (2019). Traumatic brain injury: Neuropathological, neurocognitive and neurobehavioral sequelae. Pituitary, 22(3), 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-019-00957-9

- Perlesz, A., Kinsella, G., & Crowe, S. (2000). Psychological distress and family satisfaction following traumatic brain injury: Injured individuals and their primary, secondary, and tertiary carers. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 15(3), 909–929. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-200006000-00005

- Pettemeridou, E., & Constantinidou, F. (2022). The cortical and subcortical substrates of quality of life through substrates of self-awareness and executive functions, in chronic moderate-to-severe TBI. Brain Injury, 36(1), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2022.2034960

- Pettemeridou, E., Kennedy, M. R., & Constantinidou, F. (2020). Executive functions, self-awareness and quality of life in chronic moderate-to-severe TBI. Neurorehabilitation, 46(1), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-192963

- Prigatano, G. P., Borgaro, S., Baker, J., & Wethe, J. (2005). Awareness and distress after traumatic brain injury: A relative’s perspective. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 20(4), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-200507000-00007

- Prigatano, G. P., & Sherer, M. (2020). Impaired self-awareness and denial during the postacute phases after moderate to severe traumatic brain injury. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1569. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01569

- Richardson, C., McKay, A., & Ponsford, J. L. (2014). The trajectory of awareness across the first year after traumatic brain injury: The role of biopsychosocial factors. Brain Injury, 28(13-14), 1711–1720. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2014.954270

- Richardson, C., McKay, A., & Ponsford, J. L. (2015). Factors influencing self-awareness following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 30(2), E43–E54. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000048

- Rogers, A., & McKinlay, A. (2019). The long-term effects of childhood traumatic brain injury on adulthood relationship quality. Brain Injury, 33(5), 649–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2019.1567936

- Rowlands, L., Coetzer, R., & Turnbull, O. H. (2020). Building the bond: Predictors of the alliance in neurorehabilitation. Neurorehabilitation, 46(3), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-193005

- Royal College of Physicians and British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine. (2003). Rehabilitation following acquired brain injury: National clinical guidelines (L. Turner-Strokes, Ed.). RCP, BSRM.

- Rubin, E., Klonoff, P., & Perumparaichallai, R. K. (2020). Does self-awareness influence caregiver burden? Neurorehabilitation, 46(4), 511–518. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-203093

- Ruet, A., Bayen, E., Jourdan, C., Ghout, I., Meaude, L., Lalanne, A., Pradat-Diehl, P., Nelson, G., Charanton, J., & Aegerter, P. (2019). A detailed overview of long-term outcomes in severe traumatic brain injury eight years post-injury. Frontiers in Neurology, 10, 120. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00120

- Rust, J., Bennun, I., & Crowe, M. (1988). The golombok rust inventory of marital state (GRIMS): Test and handbook. NFER-Nelson.

- Saini, P., Loke, Y. K., Gamble, C., Altman, D. G., Williamson, P. R., & Kirkham, J. J. (2014). Selective reporting bias of harm outcomes within studies: Findings from a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ, 349, g6501. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g6501

- Salas, C. (2021). The historical influence of psychoanalytic concepts in the understanding of brain injury survivors as psychological patients. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 703477. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.703477

- Salas, C. E., Rojas-Líbano, D., Castro, O., Cruces, R., Evans, J., Radovic, D., Arévalo-Romero, C., Torres, J., & Aliaga, Á. (2021). Social isolation after acquired brain injury: Exploring the relationship between network size, functional support, loneliness and mental health. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(9), 2294–2318. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.1939062

- Sansonetti, D., Fleming, J., Patterson, F., & Lannin, N. A. (2021). Conceptualization of self-awareness in adults with acquired brain injury: A qualitative systematic review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(8), 1726–1773. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.1924794

- Sasse, N., Gibbons, H., Wilson, L., Martinez-Olivera, R., Schmidt, H., Hasselhorn, M., von Wild, K., & von Steinbuchel, N. (2013). Self-awareness and health-related quality of life after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 28(6), 464–472. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e318263977d

- Schönberger, M., Humle, F., & Teasdale, T. W. (2006a). Subjective outcome of brain injury rehabilitation in relation to the therapeutic working alliance, client compliance and awareness. Brain Injury, 20(12), 1271–1282. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050601049395

- Schönberger, M., Humle, F., & Teasdale, T. W. (2006b). The development of the therapeutic working alliance, patients’ awareness and their compliance during the process of brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Injury, 20(4), 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050600664772

- Sherer, M., Boake, C., Silver, B., Levin, E., Ringholz, G., Wilde, M., & Oden, K. (1995). Assessing awareness of deficits following acquired brain injury: The awareness questionnaire. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 1, 163.

- Sherer, M., & Fleming, J. (2018). Awareness of deficits. In J. M. Silver, T. W. McAllister, & D. B. Arciniegas (Eds.), Textbook of traumatic brain injury (3rd ed., pp. 269–280). American Psychiatric Pub.

- Smeets, S. M., Vink, M., Ponds, R. W., Winkens, I., & van Heugten, C. M. (2017). Changes in impaired self-awareness after acquired brain injury in patients following intensive neuropsychological rehabilitation. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 27(1), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2015.1077144

- Stagg, K., Douglas, J., & Iacono, T. (2019). A scoping review of the working alliance in acquired brain injury rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 41(4), 489–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2017.1396366

- Tate, R., Hodgkinson, A., Veerabangsa, A., & Maggiotto, S. (1999). Measuring psychosocial recovery after traumatic brain injury: Psychometric properties of a new scale. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 14(6), 543–557. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-199912000-00003

- Toglia, J., & Kirk, U. (2000). Understanding awareness deficits following brain injury. Neurorehabilitation, 15(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-2000-15104

- Vallat-Azouvi, C., Paillat, C., Bercovici, S., Morin, B., Paquereau, J., Charanton, J., Ghout, I., & Azouvi, P. (2018). Subjective complaints after acquired brain injury: presentation of the Brain Injury Complaint Questionnaire (BICoQ). Journal of Neuroscience Research, 96(4), 601–611. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.24180

- Villalobos, D., Caperos, J. M., Bilbao, Á, López-Muñoz, F., & Pacios, J. (2021). Cognitive predictors of self-awareness in patients with acquired brain injury along neuropsychological rehabilitation. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31(6), 983–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1751663

- Von Steinbüchel, N., Wilson, L., Gibbons, H., Hawthorne, G., Höfer, S., Schmidt, S., Bullinger, M., Maas, A., Neugebauer, E., & Powell, J. (2010). Quality of Life after Brain Injury (QOLIBRI): scale development and metric properties. Journal of Neurotrauma, 27(7), 1167–1185. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2009.1076

- Von Steinbuechel, N., Wilson, L., Gibbons, H., Muehlan, H., Schmidt, H., Schmidt, S., Sasse, N., Koskinen, S., Sarajuuri, J., & Höfer, S. (2012). QOLIBRI overall scale: A brief index of health-related quality of life after traumatic brain injury, Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 83(11), 1041-1047. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2012-302361

- WHOQoL Group. (1993). Study protocol for the World Health Organization project to develop a quality of life assessment instrument (WHOQOL). Quality of Life Research, 2(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00435734

- Williams, L. M., & Douglas, J. M. (2022). It takes two to tango: The therapeutic alliance in community brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Impairment, 23(1), 24–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2021.26

- World Health Organization. (2020a). Global health estimates 2020: Deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2019.

- World Health Organization. (2020b). Global health estimates 2020: Disease burden by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2019.

- Yarkoni, T., Poldrack, R. A., Nichols, T. E., Van Essen, D. C., & Wager, T. D. (2011). Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nature Methods, 8(8), 665–670. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1635

- Yeates, G., Henwood, K., Gracey, F., & Evans, J. (2007). Awareness of disability after acquired brain injury and the family context. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 17(2), 151–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010600696423