ABSTRACT

This study aims to design and pilot an empirically based mobile application (ActiviDaily) to increase daily activity in persons with apathy and ADRD and test its feasibility and preliminary efficacy. ActiviDaily was developed to address impairments in goal-directed behaviour, including difficulty with initiation, planning, and motivation that contribute to apathy. Participants included patients with apathy and MCI, mild bvFTD, or mild AD and their caregivers. In Phase I, 6 patient-caregiver dyads participated in 1-week pilot testing and focus groups. In Phase II, 24 dyads completed 4 weeks of at-home ActiviDaily use. Baseline and follow-up visits included assessments of app usability, goal attainment, global cognition and functioning, apathy, and psychological symptoms. App use did not differ across diagnostic groups and was not associated with age, sex, education, global functioning or neuropsychiatric symptoms. Patients and care-partners reported high levels of satisfaction and usability, and care-partner usability rating predicted app use. At follow-up, participants showed significant improvement in goal achievement for all goal types combined. Participant goal-directed behaviour increased after 4 weeks of ActiviDaily use. Patients and caregivers reported good usability and user satisfaction. Our findings support the feasibility and efficacy of mobile-health applications to increase goal-directed behaviour in ADRD.

Introduction

Apathy is the most prevalent and debilitating neuropsychiatric symptom in patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders (ADRDs). The overall prevalence of apathy in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) is ∼60% (Terum et al., Citation2017), and it is highly common in other ADRDs, including behavioural variant frontotemporal degeneration (bvFTD), where apathy is present in ∼90% of patients at initial presentation (Dujardin, Citation2007). Apathy manifests as a decrease in goal-directed behaviour (GDB) (Cosseddu et al., Citation2020) with deficits in planning, motivation and initiation of even the simplest self-care activities, which contribute to deteriorating function and quality of life. As functional decline worsens, so does the impact on caregiver depression, burden, and stress (Marin et al., Citation1991; Breitve et al., Citation2018; Miyagawa et al., Citation2020) Not surprisingly, without effective treatments available, the presence of apathy has been associated with poor prognostic outcomes, including conversion from MCI to dementia, accelerated functional decline, and mortality (Terum et al., Citation2017; O'Connor et al., Citation2016; Morris, Citation1997). Thus, the prevalence of apathy across ADRDs and its significant impact on patients and caregivers argue for the importance of developing empirically validated and innovative interventions for patients and families struggling to manage apathy on a daily basis.

Defining the multidimensional syndrome of apathy using the model of impaired goal-directed behaviour

While once broadly defined as a lack of motivation (Kaufer et al., Citation2000), apathy is increasingly recognized as a multidimensional syndrome arising from impairments in distinct components of GDB (Cosseddu et al., Citation2020). Our group has demonstrated that impairments in each of the three GDB processes – initiation, planning and motivation – play a role in apathy in ADRD, reflecting that apathy is a heterogenous syndrome that includes disruption of any GDB processes (Albert et al., Citation2011; Marin, Citation1996). Initiation involves the ability to activate both cognitive and motor functions to begin an act or thought and impairment results in a loss of spontaneous action (Schwab et al., Citation1969). Planning is a multi-step executive process that supports the execution of GDB. Patients with planning deficits are unable to mentally sequence and manipulate multiple components of a task to execute an action (Massimo & Evans, Citation2014). Lastly, motivation involves the ability to select a behavioural goal (Cosseddu et al., Citation2020). Incentive is lost when there is an inability to evaluate and interpret the consequences of behaviour (Folstein et al., Citation1975). The treatment of apathy has been hindered because apathy has historically been viewed and treated as a homogeneous entity. Here we apply our current understanding of GDB mechanisms underlying apathy to inform the development of our novel mobile-app intervention, ActiviDaily.

Assistive technology to support persons with ADRD and their caregivers

There has been growing interest in the use of assistive technology in dementia care. Mobile health applications offer many advantages including easy access, portability, and user customization (Zamboni et al., Citation2008). While most ADRD-related apps are targeted at caregivers to provide content such as resources for support, individuals with ADRD, especially those in the mild stage of illness, may also benefit from app-based behavioural interventions. However, existing apps for patients with ADRD focus on increasing socialization or minimizing health and safety issues but not on the management of behavioural symptoms (Tsai et al., Citation2021). To address this gap, we developed a novel, mobile-based application to help persons with ADRD increase their daily activities. The overall objective of our study was to develop and test the mobile app, “ActiviDaily” that incorporates a scientifically based model of apathy to address the three core components of GDB (initiation, planning and motivation) that have thus far evaded management. The aims of our 2-phase study were to: (1) design a mobile application that is informed by patients, caregivers and clinicians (Phase I) (2) assess feasibility of ActiviDaily (Phase I & II) and, (3) evaluate the preliminary efficacy of ActiviDaily on patient activity (Phase II). We hypothesized that an engaging and easy-to-use app based on empirically supported components of GDB would provide a framework for patients and caregivers to increase goal-directed behaviours and better manage apathy. We also hypothesized that regular use of ActiviDaily would be associated with improved daily functioning in patients and reduced burden in caregivers.

Methods

Participants

Patient participants were diagnosed using published criteria for Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), (Lewis, Citation1995) Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) (McKhann et al., Citation2011) or behavioural variant Frontotemporal Degeneration (bvFTD), (Dujardin, Citation2007) through weekly multidisciplinary consensus meetings in the University of Pennsylvania, Penn Memory Center and Frontotemporal Degeneration Center. Participants were required to have a care-partner who had daily contact and was willing and able to complete study visits. We included those with mild-stage disease defined by a global Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) plus NACC FTLD rating of .5–1, which includes behaviour and language domains (Levy & Dubois, Citation2006). An Android smartphone was provided to the patient-caregiver dyad and they were required to use the study smartphone for the duration of the study. Prior smartphone use was not required. Patients were eligible for recruitment if they scored >19 on the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) within 12 months prior to enrolling and endorsed apathy on the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Questionnaire (NPI-Q). Patients with clinically significant and unmanaged depression were excluded due to overlap in symptoms with dementia-related apathy. Potentially eligible subjects were recruited from clinical and research cohorts within the PMC and the FTDC at the University of Pennsylvania. See Table S1 for study timeline and assessments. The study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania IRB, and all participants gave informed consent.

Actividaily mobile application

The ActiviDaily mobile application was developed and piloted in a 2-phase approach to address impaired goal-directed behaviour and target low initiation, planning and motivation in persons with dementia. ActiviDaily prompts patients to engage in activities from four commonly impacted categories of daily function: Brain Health, Body Health, Personal Care, and Housework. To target initiation, prompts alert users with an audible tone and a push notification. The push notification displays the activity’s name and prompts the user to open ActiviDaily. To target planning, calendars and checklists were used to simplify activities in a step-by-step fashion, thereby creating a specific plan to attain a goal. Some activities have an assigned day and time to complete an activity (i.e., “Scheduled” activity), while other activities were assigned to a day, but could be completed throughout the day (i.e., “Anytime” activity). The app was designed to be engaging and user-friendly. The interface design includes a minimal button design and simple mechanics to avoid confusion and distraction and excludes sliders and scrolling to keep the interface simple and consistent (see Figure S1). There are options for the user to “Skip” the activity or “Snooze” the alerts for 15 min, as needed, to allow for flexible scheduling with built-in repeated reminding. Once an activity was completed, the participants were prompted to indicate “task completion” by tapping a checkbox. Lastly, as patients complete their activities, they receive rewards (digital coins) that they can spend on motivating features, such as music and games from the app’s game store. Users were instructed to keep the phone close to their person or in a central location of their home, where audible alerts could be heard.

Phase I

Phase I included 6 patient-caregiver dyads (), who participated in a baseline visit, one week of at-home ActiviDaily use, and a follow-up visit. Participants completed a brief baseline assessment of cognition, neuropsychiatric symptoms and function (MMSE, NPI-Q, CDR), and a semi-structured interview to complete a Goal Attainment Scale (GAS). The study coordinator completed a training session with the dyad, including (1) demonstrating ActiviDaily features and step-by-step tasks and, (2) each member of the dyad completed pre-specified tasks with corrective feedback. Training was dynamic and tailored to the participant and care partner’s skill level with smartphone technology.

Table 1. Phase I and II participant demographics and baseline features.

Focus groups

At the end of one week of home use of ActiviDaily, the dyad participated in a focus group and completed the follow-up GAS. The focus group included a semi-structured discussion to solicit feedback on user experience and included a multi-disciplinary team comprised of app developers and research staff. Feedback from participants provided useful insight into usability improvements, many of which were implemented prior to Phase II (e.g., design of the home screen, contrast).

Phase II

Phase II included 24 dyads (), who participated in a baseline visit, four weeks of at-home ActiviDaily use, and a follow-up visit. Baseline data were obtained across two visits and included a semi-structured interview to establish GAS (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) goals and measures of global cognition (MMSE Massimo et al., Citation2009 or Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status TICS, Yousaf et al., Citation2020), functioning (CDR Weintraub et al., Citation2005), and presence and level of apathy (NPI-Q) (Zarit et al., Citation1985). Secondary outcomes included the Apathy Evaluation Scale (AES) (Massimo et al., Citation2015), Dementia Quality of Life instrument (DEMQOL) (Jennings et al., Citation2018), Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) (Rascovsky et al., Citation2011), Schwab and England Activities of Daily Living scale (SEADL) (van Reekum et al., Citation2005), and the Zarit Burden Interview; (ZBI) (Brandt et al., Citation1988). We measured usability and user satisfaction with the IBM Computer Usability Satisfaction Questionnaire (IBM CUSQ) (Brod et al., Citation1999).

Semi-structured interview and goal attainment scale

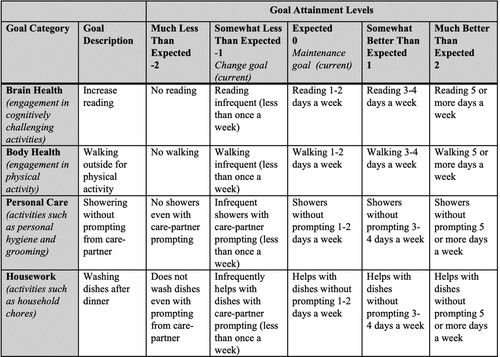

Patients and care-partners met with study clinicians (LM or DMH) pre-intervention to identify activities to establish actionable goals. To ensure standardized GAS procedures, including rater training and consensus, both raters completed GAS measurements on goal setting and attainment in Phase I. Through a semi-structured interview, the study clinician and participants identified daily activity goals. The semi-structured interviews probed for details of a “typical day,” including activities completed by the participant during morning and evening routines and throughout the day, the participant’s home, hobby, social, physical and intellectual areas of interest, activities that were previously engaged in and discontinued, and the amount of prompting required for personal, household, and hobby-based activities. Examples of experiences shared during the semi-structured interview included missed personal hygiene activities during a morning routine, forgetting to call friends and family, reduced physical activity, and less engagement in prior hobbies such as reading and card games. The semi-structured interview was used to establish goals that were personalized to participant needs, that would improve quality of life (e.g., engage in a hobby), reduce caregiver burden (e.g., set the table), or support body health (e.g., take daily walks). See for example. ActiviDaily prompted the patient to perform activities at an agreed-upon schedule (e.g., at 3:30pm every day, prompt to take medication) or to be completed at some point during the day. Our primary outcome was goal attainment. The GAS (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) identified the current level of functioning and operationalized the actions necessary to change a behaviour. The GAS places personalized goals on a standard scale ranging from −2 to 2 to compare goal achievement pre- and post-intervention (i.e., −2 representing a decrease, −1 representing no change, and 0, 1 and 2 representing an increase in GDB), as well as between goals and participants. The GAS was used to measure the impact of the participant’s use of ActiviDaily on goal attainment.

Figure 1. Example Goal Assessment Scale (GAS) Worksheet. The GAS allows for individualized goals to be established on a standard scale (−2–2). The above table is an example of four goals (reading, walking, showering, washing dishes) across each of the four goal categories (Brain Health, Body Health, Personal Care, and Housework). The goal attainment levels operationalize the behaviour in order to determine if there is an improvement. The level of change ranges from Much (−2) or Somewhat (−1) Less Than Expected, to Expected (0), to Somewhat (1) or Much (2) Better Than Expected. The goals set in this study were “change goals,” meaning the reported level of baseline behaviour was set at −1.

Activities were programmed into ActiviDaily before participants received a phone, but care-partners were able to change the notifications for activities, create new activities, or delete activities. No care-partners changed the activities for which goals were created without first speaking with a member of the study team.

COVID-19 adjustments

In order to continue enrolment during the COVID-19 pandemic, procedures were changed to remote visits. All study materials, including the study phone and charger and questionnaires, were sent to participants. The TICS, which can be completed remotely, replaced the MMSE. Study sessions were primarily completed via video conferencing. Actividaily use was demonstrated via video conference to ensure participant and study partner understanding of the app features.

Data management

Data on app use was collected after phones were returned to the study team. The app log recorded events within the app only and was saved to a secure server. Events recorded on the log included activity timestamps, completed or skipped or snoozed activities, newly created and deleted activities, tokens earned and spent, purchases within the shop, and other events.

Statistical methods

When comparing characteristics across diagnostic groups (i.e., MCI, AD, bvFTD), we applied ANOVA for continuous characteristics and chi-squared tests for categorical characteristics. For variables that were noted to be significant, we further applied pairwise tests with Bonferroni corrections to account for multiple comparisons. We applied linear mixed-effects (LME) models to assess the impact of demographic characteristics (e.g., age, sex, education) on patterns of app use across four weeks, such as the frequency that the app was opened, or use of “skip” and “snooze” features. A random intercept was used in the LME model to account for correlations among repeated outcomes. To test whether each subtype of goals (e.g., brain health and housework) or the combined goal has been achieved, we used one-sided t-tests after verifying the data normality assumption via the Shapiro–Wilk test. We used logistic regression to determine associations between GAS score and psychological measures in the patient and care-partner. In these analyses, our predictor was task completion and our outcome was GAS treated as a binary variable (e.g., ≥ 0 indicated goals were attained; < 0 goals were not attained). To compare changes in outcomes from pre- to post-intervention, we adopted two sample paired t-tests. Statistical analyses were done using R software (version 4.0.2).

Results

Sample characteristics

Phase I included six patient-caregiver dyads, who participated between February and April 2019. Patient participants were 17% female, 69 ± 8.9 years old, with a mean MMSE of 22.2 ± 3.1 and a global CDR plus NACC FTLD of 0.92 ± 0.2 (). Phase II included 24 participants who were 42% female, 70.4 ± 8.4 years old with a mean MMSE of 24.7 ± 3.1 and a global CDR of 0.69 ± 0.39 (). Participants completed phase II between June 2019 and October 2020. Comparisons between Phase II diagnostic groups showed no group differences for sex, education, and MMSE. There were significant group differences in age, CDR total and NPI-Q severity scores. The bvFTD group was significantly younger (p = .02), had a higher CDR (p = .005) and a higher NPI-Q severity score (p = .049) than either the MCI or AD group (). The Phase II care-partners were 75% female, 20 were spouses, 2 were adult children, and 2 were friends.

App use and usability

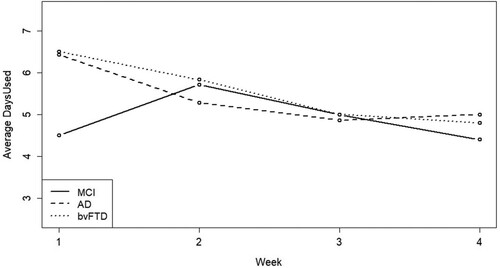

Over the 4 weeks of Phase II, participants used the app 19.38 ± 7.5 days (). Days used by group was 16 ± 9.32 for the MCI group, 21.57 ± 5.53 for the AD group, and 21.33 ± 5.92 for the bvFTD group. Participants opened ActiviDaily 88.5 ± 64.3 times, and app opening by group was 85 ± 80.2 for the MCI group, 89.3 ± 52.5 for the AD group and 92.3 ± 64.8 for the bvFTD group. App use over the four weeks is presented in . LME analyses examining the influence of age, sex, education, CDR, NPI and diagnostic category on app opening behaviour and frequency of use were not significant. Additionally, there was no difference in app opening between diagnostic groups over the four weeks of participation. Participants used the “skip” and “snooze” functions 19.6 ± 19.8 times over their participation. The skip function was used by 87.5% of participants in the MCI group, all participants in the AD group, and 83.3% in the bvFTD group. The snooze function was used by 62.5% of participants in the MCI group, 85.7% in the AD group, and all participants in the bvFTD group. Half of the participants used the coin reward feature, spending coins on in-app purchases, 5 were in the MCI group, 3 were in the AD group and 4 were in the bvFTD group.

Figure 2. App daily use over study participation depicts average daily use of ActiviDaily during each of the four weeks of study participation. The clinical group (MCI, AD, or bvFTD) data is presented separately.

Table 2. App use over study participation.

Participant ratings of app usability on the IBM CUSQ [0 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree)], indicated overall satisfaction with the app (7.3 ± 1.7) and on the individual item “Overall, I am satisfied with how easy it is to use this system” (7.9 ± 1.1). Similarly, care-partners indicated satisfaction across all IBM items and (7.2 ± 1.5) on the satisfaction item (7.2 ± 1.8). Participant assessment of usability was not predictive of goal achievement, while care-partner assessment of usability was predictive of app use (p = .04) and showed a trend for goal attainment (p = .06).

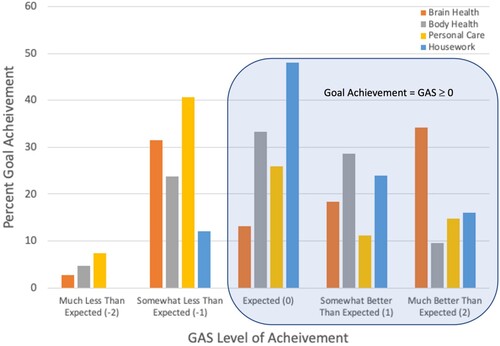

App use and outcomes

Goal-attainment scaling (GAS) was used to identify individual goals and track change in behaviour from pre- to post-intervention with ActiviDaily (). Participants identified 4.6 ± 1.0 goals, ranging from 3 to 7 goals across four areas including brain health, body health, personal care, and housework. Participants showed significant goal achievement (GAS ≥ 0) for all goal types combined (p = .03) and for brain health (p = .004) and housework goals (p = .02), but not for body health and personal care goals. Task completion was not significantly associated with GAS outcomes.

Figure 3. Percent of goal achievement on GAS by activity area illustrates the percent goal achievement for all goals set at each level of the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS). Goals are presented separately for each of the four goal categories (Brain Health, Body Health, Personal Care, and Housework). Achievement of a GAS score of 0, 1 or 2 indicates improvement on the 5 point GAS scale from a baseline behaviour of −1. A score of −1 indicates no change from baseline and −2 indicates a decline in the behaviour.

There was no association between goal achievement (GAS) and patient psychological and functional outcomes (i.e., AES, DASS, ADL, DEMQOL) or care-partner psychological outcomes (i.e., DASS and ZBI) (Table S2). While the average ratings on the DASS decreased for both participants and care-partners from pre- to post-intervention, only participant anxiety was significantly reduced (p = .04) (Figure S2). Care-partner ratings on the Zarit Burden Questionnaire were 33.5 ± 13.8 at baseline and 31.7 ± 14.8 post-interventions but did not reach significance (p = .27).

Discussion

Impairment of GDB, often labelled apathy, is the most common and disabling behavioural symptom in persons with neurodegenerative disease (Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't, Citation2011). Prior studies suggest there are at least three different mechanisms of impaired GDB that contribute to the syndrome of apathy in dementia including deficits in initiation, planning, and motivation (Albert et al., Citation2011) Therefore, a “one size fits all” approach to managing apathy appears to be inappropriate. To this end, with input from our clinical team, app developers, patients with ADRD and their care-partners, we developed the ActiviDaily mobile app to address each component of goal-directed behaviour known to be impaired in patients with dementia. After 4 weeks of app use, we observed an increase in goal-directed behaviour. Importantly, we suggest that ActiviDaily demonstrates feasibility and preliminary efficacy in persons with MCI, AD and bvFTD.

The use of mobile-health apps to promote health and well-being has become increasingly popular, and using mobile-health apps to manage symptoms associated with chronic conditions such as ADRDs is an important but underused strategy to promote functional independence. A recent systematic review evaluating the availability of mobile apps to support ADRD patients found that most apps focused on education, alerts and social networking functions, lacking a comprehensive design to support the complex needs of persons with dementia (Guo et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, existing apps target the person with ADRD or their caregiver but rarely consider a design that includes the patient-caregiver dyad as end users (Zamboni et al., Citation2008). We designed an empirically based mobile app with input from patients and caregivers as end users, taking into account each participants’ app experience and usability ratings. Furthermore, ActiviDaily is a multi-component intervention that incorporates multiple strategies from cognitive rehabilitation interventions to increase GDB.

While assistive technologies can be useful to support persons living with dementia, usability of technology is a key element to consider in the design process. Persons with ADRD experience cognitive limitations such as memory and comprehension difficulties, executive limitations and visuospatial impairment that may make it difficult to use technology efficiently (Choi et al., Citation2020) Consistent with prior recommendations (Guo et al., Citation2020; Choi et al., Citation2020) we involved persons with dementia and their care-partners in the design process. We conducted focus groups and collected usability data to provide insight into ease of use with ActiviDaily features. Focus group participants were generally satisfied with the overall design of ActiviDaily but suggestions were made to simplify the home screen to show only four activity groups and to add more colour contrast on the home screen, and we made these adjustments before proceeding to Phase II. Data from the IBM scale suggests that both persons with ADRD and their care-partners were satisfied with design of ActiviDaily, which we attribute to the careful attention given to potential cognitive barriers and the iterative design process that considered both patient and care-partner feedback.

The overall intent of the intervention was to increase patient engagement in daily activity, therefore we used goal-attainment scaling (GAS) as our primary outcome measure, which measures personalized change in health behaviours. GAS has been used previously in dementia research where it is important to capture diverse preferences for health outcomes (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). GAS allowed us to measure clinically meaningful, patient-centric outcomes and showed significant improvement in overall goal achievement. We also collected a number of traditional psychological measures as secondary outcomes; however, the heterogenous nature of the participants (MCI, AD, and bvFTD) and small sample size were limiting factors for the use of these instruments as outcome measures. Future well-powered studies should consider clinically meaningful outcomes such as the GAS and its relationship to psychological measures often used in clinical trials.

Several suggestions could not be immediately implemented but will be included in future versions including a companion app on the care-partner’s device that allows the care-partner to easily programme activities and monitor patient progress. Participants were provided with Android OS phones, but many reported greater familiarity with Apple iPhones, therefore in the future we hope to increase availability of ActiviDaily on other operating systems. Our own observations also led to improvements to the app, including an option to purchase audio books with earned tokens. A recent scoping review (Choi et al., Citation2020) of usability barriers in ADRD suggests that attention should be paid to physical ability barriers such as tremor. We also explored voice-to-text options and voice commands. While these options were not feasible to implement in the current study, these features would benefit those with tremors, arthritis, or unfamiliarity with smartphones. Another area for future development is to incorporate a goal-setting function within the app to engage the patient and care-partner through targeted questions and a decision-tree, informed by phase I and II of this study. A goal-setting feature would be helpful in expanding the accessibility of ActiviDaily use to a fully at-home setting.

Several limitations should be considered in the current study. First, this was a small feasibility study with a ADRD sample. Future studies should include different forms of ADRDs that are well-powered within each disease group. Participants in the study were given the app for only four weeks. In the future, this type of study might lend itself to a pragmatic trial where the sustainability of the app intervention is evaluated. While this pilot study was intended to develop and assess the feasibility of ActiviDaily, it must be noted that a limitation of the design is the lack of a control group and blinded raters, which will be addressed with a subsequent randomized controlled trial, based on lessons learned from this pilot study. The results from our pilot work are informative for evaluating the feasibility and usability of ActiviDaily, however, they may be biased by all study staff having knowledge of the intervention. Additionally, the participants used dedicated study phones, not their personal smartphones. There are several issues that need to be accounted for in comparing the generalizability of study phone use to future studies using participants’ personal smartphones. These include the potential unfamiliarity with the study phone operating system, not incorporating the habit of carrying a study phone or reluctance to carry a second phone on a daily basis, and the lack of other apps on the phone. The lack of other apps on the study phone has the potential to either encourage or discourage use of ActiviDaily. For example, the lack of other apps may decrease the likelihood of distraction while engaging with ActiviDaily, but it could also lead to less overall engagement with the phone and therefore fewer opportunities to respond to prompts. Finally, participants were patients at a large academic medical setting. They were well-educated and generally had access to other digital resources; thus, our participants are not entirely representative of the population of adults living with dementia.

With these caveats in mind, we developed a user-friendly mobile app to increase daily activity in persons with ADRD. We demonstrated that persons living with ADRD and their care-partners are willing to engage with ActiviDaily and found the usability of the app to be satisfactory. Importantly, we demonstrated preliminary efficacy of ActiviDaily in improving patient health goals. In sum, the results of this pilot study suggest that a mobile app intervention for persons with ADRD provides a promising avenue to deliver a multi-component non-pharmacological intervention to support daily activity in persons with dementia.

ActiviDaily_RehabNeuropsych_SupplementaryMaterials.docx

Download MS Word (964 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albert, M. S., DeKosky, S. T., Dickson, D., Dubois, B., Feldman, H. H., Fox, N. C., Gamst, A., Holtzman, D. M., Jagust, W. J., Petersen, R. C., Snyder, P. J., Carrillo, M. C., Thies, B., & Phelps, C. H. (2011). The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 7(3), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008

- Brandt, J., Spencer, M., & Folstein, M. (1988). The telephone interview for cognitive status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, & Behavioral Neurology, (2), 111–117.

- Breitve, M. H., Bronnick, K., Chwiszczuk, L. J., Hynninen, M. J., Aarsland, D., & Rongve, A. (2018). Apathy is associated with faster global cognitive decline and early nursing home admission in dementia with Lewy bodies. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy, 10(1), 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-018-0416-5

- Brod, M., Stewart, A. L., Sands, L., & Walton, P. (1999). Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: The dementia quality of life instrument (DQoL). The Gerontologist, 39(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/39.1.25

- Choi, S. K., Yelton, B., Ezeanya, V. K., Kannaley, K., & Friedman, D. B. (2020). Review of the content and quality of mobile applications about Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 39(6), 601–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464818790187

- Cosseddu, M., Benussi, A., Gazzina, S., Alberici, A., Dell'Era, V., Manes, M., Cristillo, V., Borroni, B., & Padovani, A. (2020). Progression of behavioural disturbances in frontotemporal dementia: A longitudinal observational study. European Journal of Neurology, 27(2), 265–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14071

- Dujardin, K. (2007). Apathie et pathologies neuro-dégénératives: Physiopathologie, évaluation diagnostique et traitement. Revue Neurologique, 163(5), 513–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-3787(07)90458-0

- Engelsma, T., Jaspers, M. W. M., & Peute, L. W. (2021). Considerate mHealth design for older adults with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias (ADRD): A scoping review on usability barriers and design suggestions. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 152, 104494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2021.104494

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

- Guo, Y., Yang, F., Hu, F., Li, W., Ruggiano, N., & Lee, H. Y. (2020). Existing mobile phone apps for self-care management of people with Alzheimer disease and related dementias: Systematic analysis. JMIR Aging, 3(1), e15290. https://doi.org/10.2196/15290

- Jennings, L. A., Ramirez, K. D., Hays, R. D., Wenger, N. S., & Reuben, D. B. (2018). Personalized goal attainment in dementia care: Measuring what persons with dementia and their caregivers want. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 66(11), 2120–2127. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15541

- Kaufer, D. I., Cummings, J. L., Ketchel, P., Smith, V., MacMillan, A., Shelley, T., Lopez, O. L., & DeKosky, S. T. (2000). Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the neuropsychiatric inventory. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 12(2), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.12.2.233

- Levy, R., & Dubois, B. (2006). Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits. Cerebral Cortex, 16(7), 916–928. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhj043

- Lewis, J. R. (1995). IBM computer usability satisfaction questionnaires: Psychometric evaluation and instructions for use. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 7(1), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447319509526110

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Marin, R. S. (1996). Apathy and related disorders of diminished motivation. In American Psychiatry Association Review of Psychiatry (pp. 205–242). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

- Marin, R. S., Biedrzycki, R. C., & Firinciogullari, S. (1991). Reliability and validity of the apathy evaluation scale. Psychiatry Research, 38(2), 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(91)90040-V

- Massimo, L., Evans, L. K., & Grossman, M. (2014). Differentiating subtypes of apathy to improve person-centered care in frontotemporal degeneration. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 40(10), 58–65. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20140827-01

- Massimo, L., Powers, C., Moore, P., Vesely, L., Avants, B., Gee, J., Libon, D. J., & Grossman, M. (2009). Neuroanatomy of apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 27(1), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1159/000194658

- Massimo, L., Powers, J. P., Evans, L. K., McMillan, C. T., Rascovsky, K., Eslinger, P., Ersek, M., Irwin, D. J., & Grossman, M. (2015). Apathy in frontotemporal degeneration: Neuroanatomical evidence of impaired goal-directed behavior. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00611

- McKhann, G. M., Knopman, D. S., Chertkow, H., Hyman, B.T., Jack Jr., C. R., Kawas, C. H., Klunk, W. E., Koroshetz, W. J., Manly, J. J., Mayeux, R., Mohs, R. C., Morris, J. C., Rossor, M. N., Scheltens, P, Carrillo, M. C., Thies, B., Weintraub, S., Phelps, C. H. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement, (3), 263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005

- Miyagawa, T., Brushaber, D., Syrjanen, J., Kremers, W., Fields, J., Forsberg Leah, K., Heuer Hilary, W., Knopman, D., Kornak, J., Boxer, A., Rosen Howard, J., Boeve Bradley, F., Appleby, B., Bordelon, Y., Bove, J., Brannelly, P., Caso, C., Coppola, G., Dever, R., … Wszolek, Z. (2020). Utility of the global CDR®plus NACC FTLD rating and development of scoring rules: Data from the ARTFL/LEFFTDS consortium. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 16(1), 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12033

- Morris, J. C. (1997). Clinical dementia rating: A reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. International psychogeriatrics, 9(1, Suppl 1:173-6; discussion ), 177–178.

- O'Connor, C. M., Clemson, L., Hornberger, M., Leyton Cristian, E., Hodges John, R., Piguet, O., & Mioshi, E. (2016). Longitudinal change in everyday function and behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology: Clinical Practice, 6(5), 419–428. https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000264

- Rascovsky, K., Hodges, J. R., & Knopman, D. (2011). Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain, 134(9), 2456–2477. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aw179

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't. (2011). Alzheimer's & dementia. The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association, 7(3):263–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005

- Schwab, R. S., England, A. C., Schwab, Z. J., England, A. C., & Schwab, R. S. (1969). Projection technique for evaluating surgery in Parkinson’s disease.

- Terum, T. M., Andersen, J. R., Rongve, A., Aarsland, D., Svendsboe, E. J., & Testad, I. (2017). The relationship of specific items on the neuropsychiatric inventory to caregiver burden in dementia: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(7), 703–717. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4704

- Tsai, C. F., Hwang, W. S., Lee, J. J., Wang, W.-F., Huang, L. C., Huang, L.-K., Lee, W.-J., Sung, P.-S., Liu, Y.-C., Hsu, C.-C., & Fuh, J.-L. (2021). Predictors of caregiver burden in aged caregivers of demented older patients. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02007-1

- van Reekum, R., Stuss, D. T., & Ostrander, L. (2005). Apathy: Why care? The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 17(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.17.1.7

- Weintraub, D., Moberg, P. J., Culbertson, W. C., Duda, J. E., Katz, I. R., & Stern, M. B. (2005). Dimensions of executive function in Parkinson's disease. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 20(2-3), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1159/000087043

- Yousaf, K., Mehmood, Z., Awan, I. A., Saba, T., Alharbey, R., Qadah, T., & Alrige, M. A. (2020). A comprehensive study of mobile-health based assistive technology for the healthcare of dementia and Alzheimer's disease (AD). Health Care Management Science, 23(2), 287–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10729-019-09486-0

- Zamboni, G., Huey, E. D., Krueger, F., Nichelli, P. F., & Grafman, J. (2008). Apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal dementia: Insights into their neural correlates. Neurology, 71(10), 736–742.

- Zarit, S., Orr, N. K., & Zarit, J. M. (1985). The hidden victims of Alzheimer's disease: Families under stress. NYU Press.