ABSTRACT

Aim: This cross-sectional study investigated the association between self-awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships following acquired brain injury (ABI) while controlling for the potential impact of cognitive problems. It also aimed to investigate attachment as a potential moderator. Method: 83 adults with ABI were recruited alongside a key member of their community neurorehabilitation team. The Scale to Assess Therapeutic Relationships (STAR) was used to measure therapeutic relationship quality and attachment was measured using the Experiences in Close Relationships – Relationship Structure (ECR-RS) questionnaire. Awareness was measured using the Patient Competency Rating Scale (PCRS) and the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4) provided a measure of cognitive problems. The MPAI-4 also provided an additional measure of awareness. Results: A significant association between self-awareness and therapeutic relationships was found in some regression models such that higher-quality relationships were associated with better awareness, after controlling for the impact of cognitive problems. Neither childhood parental attachment nor participants’ attachment towards their rehabilitation staff were moderators. Conclusion: The observed associations between awareness in clients and therapeutic relationships with rehabilitation staff may have importance for rehabilitation in this context. Results highlight the value of continuing to prioritize the therapeutic relational environment in ABI rehabilitation and research.

Introduction

Acquired brain injury (ABI) is one of the leading causes of death and disability around the world (World Health Organization, Citation2020a, Citation2020b) and may be associated with significant physical, cognitive, behavioural, and emotional changes to those who survive (Pavlovic et al., Citation2019). An important determinant of the impact of these changes is intellectual or offline awareness (Chesnel et al., Citation2018; Geytenbeek et al., Citation2017; Hurst et al., Citation2020; Robertson & Schmitter-Edgecombe, Citation2015). This refers to the extent to which a person can accurately recognize and acknowledge the presence, severity, and impact of their injury (Brown et al., Citation2021; Crosson et al., Citation1989). This will hereafter be referred to as awareness or self-awareness.

Current estimates suggest that impaired awareness affects 30% to 50% of individuals with ABI (Dromer et al., Citation2021; Vallat-Azouvi et al., Citation2018) and typically involves the overestimation of abilities. Biological factors related to impaired awareness include the organic nature of the injury itself (Prigatano & Klonoff, Citation1998; Terneusen et al., Citation2021), including its severity (Dromer et al., Citation2021b), as well as affected cognitive processes such as executive functioning, verbal fluency, and memory (Villalobos et al., Citation2021; Zimmermann et al., Citation2017). This is in keeping with the idea that awareness requires accurate and plastic memory systems in order to retain and update information about abilities as well as some executive control to facilitate information processing in relation to goal-directed behavior (Tate et al., Citation2014; Villalobos et al., Citation2021). Psychological factors such as defensive denial may also be related to awareness from the perspective that avoidance and denial are defences that can protect individuals from the emotional anguish that can be associated with an ABI (Belchev et al., Citation2017). Indeed, better mood and emotional adjustment have been found in individuals with more impaired awareness (Dromer et al., Citation2021b), in what some consider to be a buffering effect of impaired awareness against the emotional fallout of unwanted changes to the sense of self post-ABI (Lloyd et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the social environment in which impaired awareness occurs is also considered to be important because this often determines whether the individual has opportunities for their impairments to be discovered and understood (Ownsworth et al., Citation2006; Terneusen et al., Citation2021). Moreover, an individual’s social circle, including their family, friends, and clinicians, often provide the benchmark against which awareness deficits are measured and therefore related social factors may influence the level of unawareness that is perceived and subsequently measured (Bowen et al., Citation2018). A recent systematic review also found positive associations between better awareness and higher quality spousal and therapeutic relationships following ABI (McCabe et al., Citation2023). In one interpretation of this finding, it is possible that better quality relationships provide a safe relational space in which ABI-related difficulties may be confronted and processed by an individual and thus they may present with better awareness (Bowen et al., Citation2018; Schönberger et al., Citation2006a; Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000). Alternatively, a client with strong awareness may form and maintain higher-quality therapeutic relationships, i.e., through increased motivation for and collaboration regarding rehabilitation goals. Conversely, being confronted with the true magnitude of one’s deficits when previously unaware can elicit defensive reactions which can place a strain on the relationship (Schönberger et al., Citation2006b; Stagg et al., Citation2019).

Whilst the direction of the association between awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships cannot be inferred from correlational studies, the relational framework on which this current study is based posits that social relationships may be at the core of sense-making and self-awareness (Bowen et al., Citation2018; Yeates et al., Citation2006, Citation2007), with therapeutic relationships considered to be particularly important in some interventions for improving awareness following ABI (Dirette, Citation2010; Sherer et al., Citation1998; Sherer & Fleming, Citation2018). However, to the current authors’ knowledge, only three published studies have investigated the association between self-awareness and therapeutic relationships following ABI (McCabe et al., Citation2023). Firstly, Schönberger et al. (Citation2006a) investigated how demographic variables impact the interplay between therapeutic relationship, awareness, and intervention adherence during outpatient rehabilitation. Of particular note from this study is the finding that clients’ ratings of their emotional bond with their primary therapists (predominantly psychologists) accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in client awareness such that stronger emotional bonds were related to better awareness. Furthermore, the emotional bond accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in awareness after controlling for injury-related variables such as injury localization and length of hospitalization (Schönberger et al., Citation2006a). Secondly, Schönberger et al. (Citation2006b) found that clients who reported high levels of injury-related problems had significantly better therapeutic relationships than those who did not. However, these correlations did not remain significant when clients’ awareness levels were included in the analysis and controlled for. The conclusion drawn is that participants who reported high levels of injury-related problems had significantly better therapeutic relationships, but not due to their high levels of problem reporting. Rather, the authors hypothesized that participants who reported high levels of injury-related problems had better awareness which, in turn, was what allowed for better therapeutic relationships (Schönberger et al., Citation2006b). Finally, Neal and Greenwald (Citation2022) investigated the association between self-awareness and therapeutic relationships with speech-language pathologists but did not find significant correlations between the two variables.

The limited number of studies that have investigated the association between self-awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships represents an important gap in the literature. Furthermore, the potential influence of cognitive problems has not yet been adequately considered in relation to this association (McCabe et al., Citation2023). This is despite the impact that cognitive impairment can have on awareness levels following ABI (Villalobos et al., Citation2021; Zimmermann et al., Citation2017). In addition, the association between therapeutic relationships and awareness has only been studied in the past from the perspective of relationships with psychologists (Schönberger et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b) and speech therapists (Neal & Greenwald, Citation2022). However, Bordin (Citation1979s) conceptualization of the therapeutic relationship incorporates key processes that relationships between clients and non-clinically trained frontline staff involve. This includes the emotional bond between both parties as well as their level of agreement on therapy tasks, goals, and desired outcomes (Rowlands et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, not all individuals with ABI have access to or require in-depth psychotherapy (Coetzer, Citation2014) and the nature of many stepped-care brain injury services is such that individuals often spend more time with non-clinically trained frontline staff than with any other professional (Burke et al., Citation2020; Chouliara et al., Citation2021). In fact, several studies on stroke rehabilitation have found that therapeutic relationships with frontline professionals including healthcare assistants, rehabilitation assistants, and nurses are active components of successful outcomes (Bishop et al., Citation2021; Gordon et al., Citation2022; Heredia-Callejón et al., Citation2023) and so, it is important to capture these therapeutic relationships. This will help determine whether previously identified associations between awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships with psychologists were due to the explicit training that psychologists receive in forming strong working alliances or whether they are also due to factors related to therapeutic relationships more broadly, i.e., those which can be formed with non-clinically trained frontline rehabilitation staff.

Moreover, no study has sought to understand potential moderating variables in the association between self-awareness and therapeutic relationships. The current authors, however, consider whether attachment may play a role. Attachment bonds have long been considered important in the context of therapeutic relationships (Bordin, Citation1979; Egozi et al., Citation2023), including therapeutic relationships in neurorehabilitation settings (Lustig et al., Citation2003). Furthermore, we posit that the formative role that paternal attachment has in awareness development in childhood (Cassidy, Citation1988; Goodvin et al., Citation2008; Pipp et al., Citation1992; Rosen & Patterson, Citation2011; von Tetzchner, Citation2022) can be extended to consider how awareness may re-develop following ABI in the context of therapeutic relationships. In essence, we propose that strong working alliances in the context of secure attachments may support the re-development of awareness following injury to the brain. This is supported by the idea that childhood relational experiences regularly feature in the therapeutic relationships formed during neurorehabilitation (Salas, Citation2012). Importantly, because such transferential processes are implicit by nature they are rarely compromised by cortical damage (Salas, Citation2012) and, so, it is possible that such relational experiences may act as blueprints for awareness to re-develop following ABI. Indeed, attachment theory has already been considered by Yeates and Salas (Citation2019) with regard to the degree to which individuals with ABI acknowledge their need to reach out to others for support. In particular, they state that those whose caregivers were available and responsive to them as children may be more likely to recognize their need to depend on others following ABI whereas those with more insecure attachments may be more rejecting of support (Yeates & Salas, Citation2019). However, self-awareness following ABI is much more nuanced than just recognizing the need for and accepting support. It also relates to the acquisition of new self-knowledge regarding the presence of specific impairments and an understanding of their implications in daily life (Sansonetti et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, attachment is not necessarily considered to be rigidly fixed across the lifespan (Belsky, Citation2002; Fraley & Roisman, Citation2019). As such, it is also possible that attachments in other relationships, perhaps therapeutic relationships, may similarly underlie the association between the quality of those relationships and awareness.

In summary, few studies have investigated the association between self-awareness and therapeutic relationships following ABI and none have controlled for the potential impact of cognitive problems, something the current study aimed to do. Furthermore, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this was the first study to investigate attachment as a potential moderating variable in the association between awareness and therapeutic relationships. This study investigated this association with regard to therapeutic relationships with frontline rehabilitation staff.

Aims and hypotheses

The current study aimed to investigate the nature of the association between self-awareness following ABI and quality of therapeutic relationships with predominantly frontline rehabilitation staff. We hypothesized that therapeutic relationships would account for a significant proportion of the variance in clients’ self-awareness while controlling for the degree of cognitive problems. We also predicted that clients’ childhood parental attachment and their current attachment with their rehabilitation staff would moderate the association between awareness and therapeutic relationship quality.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The current sample of 83 participants consisted of 54 males and 29 females with ABI. In 2022, they were recruited to this cross-sectional study using opportunity sampling. Participants were recruited from an organization in Ireland providing publicly-funded non-acute brain injury rehabilitation services under Section 39 of the Health Act, 2004. This CARF-accredited organization provides post-acute community and residential rehabilitation as well as family and carer support, day services, and vocational rehabilitation. In the current study, 10 participants were receiving residential rehabilitation at the time of data collection while the remaining 73 lived independently in the community and received community support. This typically takes the form of biweekly rehabilitation sessions delivered by frontline rehabilitation staff in participants’ own homes and is overseen by a multidisciplinary team consisting of psychologists, occupational therapists, and/or social workers. For residential clients, it involves 24/7 ongoing staff support, also overseen by the MDT, with a focus on promoting independent living and community engagement.

For each ABI participant, hereafter referred to as a client, a key member of their rehabilitation staff who worked with them towards mutually agreed goals for at least three months was also recruited. This formed a client-staff dyad from which scores could also be collected and compared. These members of staff are hereafter referred to as keyworkers. Overall, 34 keyworkers were recruited for this study, with 15 of these participating as part of more than one dyad. Twenty-three of the keyworkers were female and 11 were male. For three clients who volunteered to participate, the keyworker recruited as part of their respective dyads consisted of two clinical psychologists and one social worker. This was due to there being no other rehabilitation staff available to participate. For the remaining 80 clients, their keyworkers consisted of frontline rehabilitation staff, all of whom were required to possess a minimum qualification of their Irish school leavers examinations: the Leaving Certificate, as well as a third-level qualification in health or social care to a minimum standard of Level 5 Quality and Qualifications Ireland (QQI). Although some frontline rehabilitation staff may have possessed additional third-level training, these staff members did not conduct assessments, develop formulations, or offer therapeutic interventions as part of their employment by the host organization. Instead, their roles centred on the implementation of individual rehabilitation plans which were designed by the host organization’s multi-disciplinary clinicians.

Regarding the clients who participated in this study, those aged between 18 and 65 years at the time of data collection were considered eligible for inclusion. Clients with co-morbid mental illness which impaired their self-awareness were excluded from this study by the host organization’s senior clinicians who took on a gatekeeping role for the recruitment process. Clients with episodic/autobiographical memory impairments that resulted in an inability to describe the quality of their interpersonal relationships were also excluded.

This study received formal ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the host organization and from the Education and Health Science’s Research Ethics Committee of the University of Limerick (2021_11_26_EHS_OA). To complete the research questionnaires, clients met with a member of the research team while keyworkers completed their questionnaires independently online. All participants provided informed written consent and the study adhered to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guideline (STROBE).

Measures

Patient Competency Rating Scale (PCRS)

The PCRS (Prigatano & Fordyce, Citation1986) is a 30-item questionnaire with self and informant versions that are designed to rate the abilities of individuals with brain injuries to complete tasks of everyday living. In addition to a total score, it has four subdomains including Activities of Daily Living (ADLs), Cognitive, Interpersonal, and Emotional sub-domains. Response options which are on a five-point Likert scale range from “can’t do” to “can do with ease,” with higher scores indicating higher perceived abilities. In line with its intended use (Mahoney et al., Citation2019), the discrepancy between self and keyworker versions of the PCRS was used to help determine clients’ self-awareness in the current study. Namely, the PCRS double criterion by Bivona et al. (Citation2019) was used to classify clients as presenting with either minimal/no impaired self-awareness or as presenting with severely impaired self-awareness. In particular, clients were categorized as having severely impaired self-awareness when: (i) the PCRS client total score was >100 points (suggesting that clients perceived themselves as having minimal difficulties) and when (ii) there was a positive PCRS discrepancy score of >20 points (suggesting that client’s rated their abilities as higher than their keyworkers did). In the current study, 21.7% of clients (N = 18) had severely impaired self-awareness (21.7%) which was comparable to the original study where 20% of the sample were found to experience severely impaired self-awareness based on this double criterion (Bivona et al., Citation2019).

Although originally designed for traumatic brain injury (TBI), good psychometric properties have been found for PCRS total scores in individuals with TBI (Prigatano et al., Citation1990; Sveen et al., Citation2015) and ABI (Barskova & Wilz, Citation2006; Hellebrekers et al., Citation2017). Understandably, given the nature of the domains assessed, the psychometric properties of PCRS subdomains are less well-supported in the literature (Hellebrekers et al., Citation2017; Hurst et al., Citation2020). The internal consistency of PCRS total scores in the current sample across self (α = .865) and keyworker versions (α = .938) was good and excellent, respectively.

Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4)

The MPAI-4 (Malec & Lezak, Citation2008) is a well-established valid and reliable 35-item tool that assesses common sequelae of ABI across cognitive, behavioural, emotional, and social domains (Guerrette & McKerral, Citation2021; Kean et al., Citation2011; Malec et al., Citation2012). Designed for use in post-acute settings, the MPAI-4 is usually completed by allied health professionals, with or without the individual with the ABI and/or a significant other. MPAI-4 items are answered on a five-point Likert scale from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicating a greater level of disability. The first 29 items can be combined to calculate an overall score as well as three subdomain scores: an Abilities Index, an Adjustment Index, and a Participation Index. In the current sample, MPAI-4 scores came from participants’ most recent quarterly-rated MPAI-4 which was completed by the host organization’s multidisciplinary team, overseen by a senior or principal psychologist who was present when the ratings were provided.

From the MPAI-4, the impaired self-awareness item, item 20, was used as an additional measure of self-awareness in the current study as it is defined as the extent to which a client lacks recognition of their personal limitations and disabilities. The majority of clients in the current study (84.42%) were rated as having either “normal” awareness (score of 0) or a tendency to minimize impairments (score of 1). This item was therefore dichotomised into 0 (complete absence of impaired awareness) and 1 (some level of impaired awareness where the original scores were 1–4). Using item 20 in this way is similar to past research by Elanjithara et al. (Citation2022), Geytenbeek et al. (Citation2017), and Malec and Moessner (Citation2000).

Furthermore, the six individual cognitive items from the Abilities Index of the MPAI-4 were combined in the current study to form a measure of cognitive problems which was used as a control variable. These six items were: verbal communication, attention/concentration, memory, fund of information, novel problem-solving, and visuospatial abilities. It is noted though that these MPAI-4 items have not been combined in this way before and that they merely provide an observer-rated indication of the impact of cognitive problems in everyday activities rather than being a direct measure of cognition. Nevertheless, the combination of these six items had acceptable internal consistency in the present sample (α = .794).

Scale to Assess Therapeutic Relationships (STAR)

The STAR is a 12-item measure of therapeutic relationship quality designed for use in community mental health settings (McGuire-Snieckus et al., Citation2007). Its self-report and other-rated versions used a five-point Likert scale to assess the quality of dyadic therapeutic relationships in the current sample from the perspective of both the client and their keyworker. Items are combined to calculate an overall score for each version with higher scores indicating a better quality relationship.

Although developed for community mental health settings, the STAR was deemed suitable for this study as it was developed to be a very short questionnaire that would be easy to administer and understand by patient populations (McGuire-Snieckus et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, all 12 items refer to events that the dyads in this study experienced as part of their neurorehabilitation, e.g., goal planning. The STAR was also chosen for its satisfactory psychometric properties, including strong factor validity, convergent validity, internal consistency, and test re-test reliability (Gairing et al., Citation2011; Geirdal et al., Citation2015; Loos et al., Citation2012; Matsunaga et al., Citation2019; McGuire-Snieckus et al., Citation2007). The STAR also showed good internal consistency in the current sample of clients (α = .865) and excellent internal consistency in our sample of keyworkers (α = .916).

Experiences in Close Relationships – Relationship Structure Questionnaire (ECR-RS)

The ECR-RS questionnaire (Fraley et al., Citation2011) is a self-report measure of attachment within and across a variety of specific relational contexts (Fraley et al., Citation2015). It assesses attachment using nine items on a seven-point Likert scale which can be applied to specific relationships such as one’s relationship with their mother (or mother-like figure), father (or father-like figure), and keyworker/therapist. The nine bi-dimensional items are combined to form an attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety score per relationship, with higher scores indicating higher levels of avoidance and/or anxiety and with lower scores reflecting a more secure attachment. This is based on a bidimensional model of adult attachment by Bartholomew and Horowitz (Citation1991) whereby the extent to which a person holds positive images of the self and of others respectively determines the level of attachment anxiety and avoidance they experience in relationships. The ECR-RS questionnaire was chosen for the current study due to its strong psychometric properties and for the empirical support for its two-factor structure (Deveci Şirin & Şen Doğan, Citation2021; Fraley et al., Citation2011; Moreira et al., Citation2015; Rocha et al., Citation2017; Sarling et al., Citation2021).

In the current study, clients completed the ECR-RS concerning their relationship with their keyworker. Similar to Jarnecke and South (Citation2013), clients in the current study also completed the ECR-RS questionnaire retrospectively with regard to their childhood attachment to their rearing mother (or mother-like figure) and rearing father (or father-like figure). Clients were asked to do so with specific reference to their middle childhood years. Good and acceptable internal consistency for the ECR-RS questionnaire was found in the current sample of clients for their ratings of attachment avoidance and anxiety towards their keyworkers (α = .865 and α = .754, respectively). Excellent internal consistency was found for clients’ childhood parental attachment avoidance (mother α = .948 and father α = .927) and childhood parental attachment anxiety (mother α = .913 and father α = .9).

Data analysis

A power calculation was completed using G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., Citation2009). This determined that a sample size of 77 clients was required for the current study to detect a medium effect size at a power of 0.8 and an alpha level of .05.

Data were first analysed with preliminary descriptive statistics as well as inferential statistics to explore relationships between variables. This was to inform subsequent regression models. In particular, the association between both client and keyworker ratings of the therapeutic relationship was explored. Additionally, the association between the awareness outcome variables and clients’ time since injury, as well as the length of time clients and keyworkers had worked together, was explored. This was to determine whether time since injury or time worked together had any impact on awareness in the current sample. Transformations were first applied to these variables if outliers were present. Where assumptions of normality were violated even after transforming the variables, non-parametric alternatives were used for these correlations. Otherwise, additional checks were completed to ensure that no outliers remained present and that there was homogeneity of variance and a monotonic relationship between variables, where applicable.

SPSS (IBM Corp, Citation2021) was then used to run hierarchical regression models to test the study’s first hypothesis that quality of therapeutic relationship would account for a significant proportion of the variance in clients’ awareness, after controlling for the degree of cognitive problems. To assess the potential moderating impact of attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety on these associations, Hayes’ (Citation2022) PROCESS Macro moderation statistics were used. Prior to these analyses, checks were completed for assumptions regarding linearity, multicollinearity, and outliers. Missing data were treated listwise by PROCESS Macro for the moderation statistics and were treated pairwise for all other models.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The current sample of 83 clients were aged between 22 and 72 years at the time of data collection (mean 45.19, standard deviation 11.45). Fifty-four of these were male and 29 were female. The average time since ABI was 7.87 years (standard deviation 7.87, range 1–33 years). A breakdown of the types of ABIs experienced is provided in below. Regarding awareness levels, as assessed using the PCRS, 21.7% of clients were considered to present with severely impaired self-awareness (N = 18) while 78.3% were considered to present with minimal/no impaired self-awareness (N = 65). On the other hand, using the dichotomous MPAI-4 awareness variable, some level of impaired awareness was rated as present in 41.6% of clients (N = 32) and rated as absent in 58.44% (N = 45). On average, clients had been working with their keyworker for 20.77 months at the time of data collection (standard deviation 24.68, range 3–180 months).

Table 1. Participants’ types of ABI.

Preliminary analyses

Firstly, the strength of the association between therapeutic relationship ratings provided by clients and their keyworkers was explored. A Spearman rank-order correlation found a statistically significant but weak correlation between the two variables (rho(78) = .256, p = .022). As a result, it was decided that each of the study’s hypotheses would be tested separately for therapeutic relationship ratings provided by both clients and their keyworkers in order to explore any differences between the two.

Secondly, correlation analyses were used to determine whether any association existed between clients’ time since injury and either of the awareness outcome variables. Results indicated that time since injury was not significantly associated with the PCRS variable (τb = .092, p = .325) or with the MPAI-4 variable (τb = .014, p = .888), as determined by Kendall’s tau-b correlations (Marascuilo & McSweeney, Citation1977). As all clients in this study were recruited from a post-acute rehabilitation service and because time since injury did not impact awareness, time since injury was not controlled for in subsequent analyses.

Finally, correlation analyses were used to determine whether any association existed between the length of time clients and keyworkers had worked together and either of the awareness variables. Results indicated that the length of time worked together was not significantly associated with the PCRS variable (rpb(82) = .009, p = .935) or with the MPAI-4 awareness variable (rpb(75) = −.047, p = .684), as determined by point biserial correlations. As such, the length of time clients and keyworkers had worked together was not controlled for in subsequent analyses.

Self-awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships

Two hierarchical regression models assessed the likelihood of clients presenting with severely impaired self-awareness, based on the PCRS variable. The first regression model used cognitive problems and client-rated therapeutic relationship as predictor variables. The first iteration of this model, which included only cognitive problems, was statistically significant, correctly classifying 79.2% of cases (χ2(1) = 7.374, p = .007, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .138). The model that also included client-rated therapeutic relationship was also statistically significant, correctly classifying 80.5% of cases (χ2(2) = 7.454, p = .024, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .139) but did not lead to a significant increase in predictive power (χ2(1) = .08, p = .778, ΔNagelkerke pseudo R2 = .001). See .

Table 2. Hierarchical logistic regression model predicting the PCRS awareness variable from cognitive problems in Model 1 and Cognitive problems and client-rated therapeutic relationship in Model 2.

In the next logistic regression model, keyworker ratings of therapeutic relationship were used. The first iteration of this model which included only cognitive problems was statistically significant, correctly classifying 78.4% of cases (χ2(1) = 5.915, p = .015, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .116). The model that also included keyworker-rated therapeutic relationship was also statistically significant, correctly classifying 81.1% of cases (χ2(2) = 10.372, p = .006, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .198) and led to a significant increase in predictive power (χ2(1) = 4.457, p = .035, ΔNagelkerke pseudo R2 = .082). See .

Table 3. Hierarchical logistic regression predicting the PCRS awareness variable from cognitive problems in Model 1 and cognitive problems and keyworker-rated therapeutic relationship in Model 2.

Next, two more logistic regressions were performed to explore the likelihood of an awareness deficit being present, based on the dichotomous MPAI-4 awareness variable. The first model used cognitive problems and client-rated therapeutic relationship as predictor variables. The first iteration of this model which included only cognitive problems was statistically significant, correctly classifying 70.1% of cases (χ2(1) = 20.525, p < .001, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .315). The model that also included client-rated therapeutic relationship was also statistically significant, correctly classifying 70.1% of cases (χ2(2) = 24.479, p < .001, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .367), and led to a significant increase in predictive power (χ2(1) = 3.954, p = .047, ΔNagelkerke pseudo R2 = .052). However, client-rated therapeutic relationship was not a unique significant predictor in this final model. See .

Table 4. Hierarchical logistic regression predicting the MPAI-4 awareness variable using cognitive problems in Model 1 and cognitive problems and client-rated therapeutic relationship in Model 2.

In the next regression model, keyworker ratings of the therapeutic relationship were used. The first iteration of this model which included only cognitive problems was statistically significant, correctly classifying 68.9% of cases (χ2(1) = 17.069, p < .001, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .279). The model that also included keyworker-rated therapeutic relationship was also statistically significant, correctly classifying 68.9% of cases (χ2(2) = 17.792, p < .001, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .29), but this addition did not lead to a significant increase in predictive power (χ2(1) = .724, p = .395, ΔNagelkerke pseudo R2 = .011). See .

Table 5. Hierarchical logistic regression predicting the MPAI-4 awareness variable using cognitive problems in Model 1 and cognitive problems and keyworker-rated therapeutic relationship in Model 2.

Attachment as a potential moderator

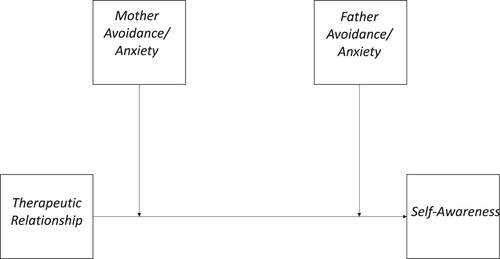

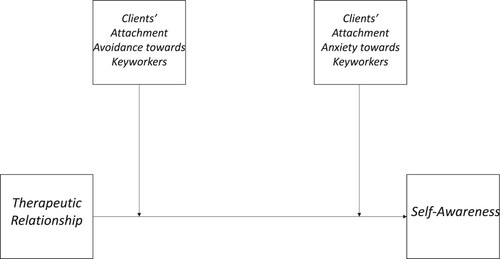

Models 1 and 2 from Hayes’ (Citation2022) PROCESS Macro were used to assess the potential moderating role of attachment avoidance and attachment anxiety in the association between quality of therapeutic relationships and awareness. As mean-centring was not used in these analyses, only overall model fit and interaction terms are reported. See and for a conceptual representation of these moderation analyses.

Figure 1. Hypothesized Moderation of the Association between Self-Awareness and Therapeutic Relationship by Childhood Parental Attachment Avoidance in One Model and Attachment Anxiety in Another.

Figure 2. Hypothesized Moderation of the Association between Self-Awareness and Therapeutic Relationship by Clients’ Attachment Avoidance and Attachment Anxiety towards Keyworkers.

Childhood parental attachment avoidance

The first moderation model explored the likelihood of clients presenting with severely impaired awareness, based on the PCRS, using client-rated therapeutic relationships, maternal attachment avoidance, paternal attachment avoidance, and their interactions. Although the full model was statistically significant (N = 80, G2(5) = 12.164, p = .033, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .219), there was no significant moderating effect of maternal (B = −.018, se = .011, p = .095, 95%CI: −.04 to .003) or paternal attachment avoidance (B = .005, se = .009, p = .544, 95%CI: −.012 to .022). When keyworker ratings of therapeutic relationship were used instead, the full model was also statistically significant (N = 77, G2(5) = 12.285, p = .031, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .23). However, there was no significant moderating effect of maternal (B = −.007, se = .009, p = .463, 95%CI: −.025 to .011) or paternal attachment avoidance (B = .006, se = .006, p = .335, 95%CI: −.006 to .017).

Next, similar moderation analyses were performed with the MPAI-4 awareness outcome variable. The first full model that used client-rated therapeutic relationship, maternal attachment avoidance, paternal attachment avoidance, and their interactions was statistically significant (N = 74, G2(5) = 13.46, p = .019, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .224). However, there was no significant moderating effect of maternal (B = −.006, se = .011, p = .588, 95%CI: −.028 to .016) or paternal attachment avoidance (B = −.003, se = .008, p = .667, 95%CI: −.019 to .012). When keyworker ratings of therapeutic relationship were used instead, the full model was not statistically significant (N = 71, G2(5) = 9.148, p = .1, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .164). There was also no significant moderating effect of maternal (B = −.005, se = .01, p = .566, 95%CI: −.023 to .012) or paternal attachment avoidance (B = .005, se = .006, p = .43, 95%CI: −.007 to .016).

Childhood parental attachment anxiety

The first model explored the likelihood of clients presenting with severely impaired awareness, based on the PCRS, using client-rated therapeutic relationships, maternal attachment anxiety, paternal attachment anxiety, and their interactions. The full model was not statistically significant (N = 80, G2(5) = 6.449, p = .265, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .12) and there was no significant moderating effect of maternal (B = −.069, se = .063, p = .278, 95%CI: −.193 to .056) or paternal attachment anxiety (B = .036, se = .038, p = .344, 95%CI: −.039 to .111). When keyworker ratings of the therapeutic relationship were used instead, the full model was statistically significant (N = 77, G2(5) = 11.903, p = .036, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .224). However, there was no significant moderating effect of maternal (B = .012, se = .03, p = .7, 95%CI: −.047 to .07) or paternal attachment avoidance (B = .012, se = .026, p = .644, 95%CI: −.039 to .063).

Next, similar moderation analyses were performed using the MPAI-4 awareness outcome variable. The first full model that used client-rated therapeutic relationship, maternal attachment anxiety, paternal attachment anxiety, and their interactions was not statistically significant (N = 74, G2(5) = 7.687, p = .174, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .133). There was also no significant moderating effect of maternal (B = .011, se = .021, p = .617, 95%CI: −.031 to .052) or paternal attachment anxiety (B = −.006, se = .016, p = .708, 95%CI: −.038 to .026). When keyworker ratings of therapeutic relationship were used instead, the full model was also not statistically significant (N = 71, G2(5) = 9.244, p = .1, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .165). There was also no significant moderating effect of maternal (B = .031, se = .029, p = .28, 95%CI: −.025 to .088) or paternal attachment anxiety (B = −.011, se = .02, p = .572, 95%CI: −.05 to .028).

Clients’ attachment towards their keyworkers

The first moderation model explored the likelihood of clients presenting with severely impaired awareness, based on the PCRS, using client-rated therapeutic relationships, keyworker attachment avoidance, keyworker attachment avoidance, and their interactions. Although the full model was statistically significant (N = 83, G2(5) = 11.372, p = .045, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .197), there was no significant moderating effect of attachment avoidance (B = .002, se = .009, p = .847, 95%CI: −.015 to .018) or anxiety (B = .049, se = .13, p = .71, 95%CI: −.207 to .304). When keyworker ratings of therapeutic relationship were used instead, the full model was also statistically significant (N = 80, G2(5) = 16.648, p = .005, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .292). However, there was no significant moderating effect of attachment avoidance (B = .002, se = .01, p = .826, 95%CI: −.017 to .022) or anxiety (B = .05, se = .086, p = .562, 95%CI: −.119 to .219).

Next, similar moderation analyses were performed with the MPAI-4 awareness outcome variable. The first full model that used client-rated therapeutic relationship, keyworker attachment avoidance, keyworker attachment anxiety, and their interactions was not statistically significant (N = 77, G2(5) = 6.907, p = .228, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = 116). Furthermore, there was no significant moderating effect of attachment avoidance (B = −.003, se = .009, p = .72, 95%CI:.−02 to .014) or attachment anxiety (B = −.007, se = .033, p = .837, 95%CI: −.072 to .058). When keyworker ratings of therapeutic relationship were used instead, the full model which included keyworker-rated therapeutic relationship, keyworker attachment avoidance, keyworker attachment anxiety, and their interactions was also not statistically significant (N = 74, G2(5) = 8.845, p = .115, Nagelkerke pseudo R2 = .153). Furthermore, there was no significant moderating effect of attachment avoidance (B = −.001, se = .008, p = .882, 95%CI: −.017 to .015) or attachment anxiety (B = −.005, se = .031, p = .873, 95%CI: −.066 to .056).

Discussion

This study contributes to pioneering investigations on the association between self-awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships following ABI and is the first to control for the potential impact of cognitive problems in the association. To the current authors’ best knowledge, this study was also the first to investigate attachment as a potential moderator of the association between self-awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships with predominantly frontline rehabilitation staff.

Using hierarchical regression models, partial support was found for the study’s first hypothesis. That was that quality of therapeutic relationships would account for a significant proportion of the variance in clients’ self-awareness, after controlling for the impact of cognitive problems. In particular, support for this hypothesis was found when keyworker ratings of the therapeutic relationship were used to predict the likelihood of clients presenting with severely impaired awareness, based on the PCRS variable. In contrast, when predicting the likelihood of an awareness deficit being present based on the MPAI-4 awareness variable, it was the addition of client-rated therapeutic relationship that significantly improved the predictive power of the model, albeit that client-rated therapeutic relationship was not a unique significant predictor on its own. Across both findings, higher-quality therapeutic relationships were associated with a reduced likelihood that an awareness deficit would be present.

It remains unclear, however, why keyworker-rated therapeutic relationship quality added significant predictive power in a model with one outcome variable and not the other, and vice versa for client-rated therapeutic relationship. In fact, our preliminary analyses showed a weak but statistically significant correlation between both relationship quality ratings. Nevertheless, there are obvious differences in how awareness was measured across models. Namely, the PCRS was a discrepancy-based measure and one which was used to identify clients with severely impaired awareness. The MPAI-4, on the other hand, provided a clinician-rated measure as to whether impaired awareness was present or absent in clients, regardless of severity. However, these differences do not fully explain the pattern of findings and there is no previous research to consult because the existing literature on the association between therapeutic relationships and self-awareness previously only explored this in relation to client-rated relationship quality (Neal & Greenwald, Citation2022; Schönberger et al., Citation2006a). It is important to remember though that client-rated therapeutic relationship was not a unique significant predictor in its model predicting the MPAI-awareness variable. Rather, its inclusion added significantly more predictive power to the model overall than when it was just the cognitive problems variable that was included. This possibly relates to the fact that the measures of both awareness and cognitive problems in this model were extracted from different indices of the same psychometric tool, the MPAI-4. So, it is possible that high internal consistency between the measure of cognitive problems and awareness in the MPAI-4 (Malec & Lezak, Citation2008) could have muted any potential additional significance that could be added by therapeutic relationship quality, individually.

In terms of the hypothesis of a potential moderating effect of attachment, our findings found that neither childhood parental nor keyworker attachment significantly moderated the association between self-awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships. Although childhood parental attachment can influence adulthood attachment and adult relationships (Bowlby, Citation1969; Doyle & Cicchetti, Citation2017; E.M., Citation1970), it is now widely accepted that childhood attachment does not necessarily pre-determine adult relational patterns in a fixed manner (Belsky, Citation2002; Fraley & Roisman, Citation2019). This may provide some explanation as to why childhood parental attachment did not moderate the association between awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships in the current sample. Regarding keyworker attachment, it is also important to note that the nature of the attachment measure used in this study was to measure the level of attachment avoidance and anxiety experienced by clients in their relationships with their keyworkers, regardless of whether they had an attachment bond or not. This is important because not all social relationships are underpinned by an attachment. For example, many have highlighted the distinction between the attachment and affiliation systems, which both form part of social relationships but with the attachment system serving to manage distress and increase safety while the affiliation system focuses on acquiring companionship, alliances, and knowledge (Gillath & Karantzas, Citation2015; Mikulincer & Selinger, Citation2001; Weiss, Citation1998). It may be the case that not all clients in the current study shared an attachment bond with their keyworkers which could explain why attachment in this regard did not moderate the association between awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships. After all, client-keyworker relationships are professional and sometimes transitory relationships.

It may also be that the association between awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships is instead underpinned by other relational qualities within these relationships. For example, the STAR questionnaire that was used in the current study to measure the quality of therapeutic relationships has three subscales. Of these subscales, the creators noted that the Positive Collaboration subscale explained the most variance in their original study and that this subscale taps into the level of openness and trust within the relationship, and a mutual understanding of therapy goals (McGuire-Snieckus et al., Citation2007). Importantly, they noted that this subscale is the least likely to be influenced by additional skills teaching with clinicians (McGuire-Snieckus et al., Citation2007). Instead, it reflects some of the more implicit relational qualities of the clinician/relationship. This is important because previously published research in the area of therapeutic relationships and self-awareness had only examined their association from the perspective of relationships with highly-trained professionals, i.e., psychologists or speech-therapists (Neal & Greenwald, Citation2022; Schönberger et al., Citation2006a, Citation2006b). However, the current study demonstrated that a significant proportion of variance in awareness may be accounted for by good-quality therapeutic relationships with predominantly frontline rehabilitation staff who would not have received explicit training in the development of working alliances or in delivering psychological interventions. This could suggest that what seems to promote better awareness following ABI in the context of therapeutic relationships is not merely the specific training that professionals receive. Rather, it could also be the implicit relational qualities and processes within those relationships, i.e., the collaboration, bond, or trust. This idea is supported by the finding that high-quality spousal relationships, too, are associated with better awareness following ABI (Burridge et al., Citation2007; McCabe et al., Citation2023). Whilst attachment may not strengthen or weaken the association between the quality of these interpersonal relationships and awareness, it has been suggested that perhaps high-quality relationships provide safe relational spaces where ABI-related difficulties can be confronted and where they may be processed and accepted by the individual (Dirette, Citation2010; Schönberger et al., Citation2006b; Sherer & Fleming, Citation2018; Toglia & Kirk, Citation2000). It is acknowledged, however, that awareness itself may influence the quality of therapeutic relationships in what may be a bidirectional association between the two constructs. For example, Schönberger et al. (Citation2006b) note that a client with strong awareness may form and maintain higher-quality therapeutic relationships, i.e., through increased motivation for and collaboration regarding rehabilitation goals. Conversely, being confronted with the true magnitude of one’s deficits when previously unaware can elicit defensive reactions which can place a strain on the relationship (Schönberger et al., Citation2006b; Stagg et al., Citation2019). However, the decision to study the association in one direction in the current study was guided by the theoretical framework that emphasizes the importance of therapeutic and working alliances in psychotherapy and neurorehabilitation outcomes (Bordin, Citation1979; Bowen et al., Citation2018; Stagg et al., Citation2019). Specifically, the quality of the working alliance is seen as a facilitator to enhancing client engagement, promoting communication, and ultimately creating an environment that supports introspection and the re-evaluation of self-perceptions, which are considered critical for developing insight post-ABI (Dirette, Citation2010; Sherer & Fleming, Citation2018). Studying the reverse relationship, i.e., how awareness may influence therapeutic relationships, represents a fundamentally different research question and one which implies a less therapist-centred model of rehabilitation, which was not the focus of the present work.

Strengths and limitations

Overall, this study adds to the literature in several important ways. Firstly, it contributes to pioneering investigations on the association between self-awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships while controlling for the potential impact of cognitive problems. Secondly, this study considered this association from the point of view of therapeutic relationships with predominantly frontline rehabilitation staff which allowed a number of preliminary conclusions to be drawn with regard to the aspects of therapeutic relationships that may be most associated with awareness, i.e., potentially non-clinically trained implicit relational qualities and processes such as collaboration, bond, or trust. Thirdly, this study was the first to investigate attachment as a potential moderating variable in the association between therapeutic relationships and awareness, albeit that attachment was not found to be a moderator in this case. Finally, this study tackled complex conceptual issues surrounding the measurement of awareness by following the recommendation to employ multiple measures of awareness and to assess it from more than one perspective (Brown et al., Citation2021; Fleming et al., Citation1996).

Despite these strengths, there are some limitations to note. Firstly, despite internal consistency ranging from acceptable to excellent in the current study, to the best of the current author’s knowledge, the ECR-RS has not been validated with regard to assessing child–parent attachment retrospectively, or with regard to therapeutic relationships. This is despite the authors of the measure endorsing its use for this latter purpose (Fraley et al., Citation2011).

Secondly, our measure of cognitive problems was extracted from the six cognitive items of the MPAI-4. Despite acceptable internal consistency in the current sample and strong face validity, to our knowledge, this is the first time these items have been used together as a measure of the degree of cognitive problems in this context. Furthermore, it is acknowledged that this combination of MPAI-4 items while providing an observer-rated indication of the impact of cognitive problems in everyday activities is not a direct measure of cognition. Moreover, it is not possible to rule out the possibility that the predictive contribution that cognitive problems made to our MPAI-4 awareness variable in those models stemmed from a high level of internal consistency between the two variables.

Finally, it is important to note that 15/34 keyworkers in this study participated in more than one participant-keyworker dyad. As such, it is not possible to rule out that keyworkers with a greater propensity for building relationships or promoting client awareness were not over- or under-represented in the current sample or showed within-subjects correlation. In fact, few variables were normally distributed in this study, i.e., predominantly low discrepancy scores were recorded on the PCRS and most dyads rated the therapeutic relationship as high-quality. However, this may relate to the screening that all clients undergo prior to receiving rehabilitation in order to ensure that they have sufficient insight to participate and to set realistic goals. It also likely reflects the strict recruitment criteria for brain injury rehabilitation assistants/keyworkers, ensuring that only those who espouse the host organization’s values and vision are employed into those roles.

Future directions

A number of important areas for future research have emerged from the findings of this study. Firstly, previous research demonstrated that high-quality therapeutic relationships with highly trained professionals, i.e., psychologists, can be associated with better self-awareness (Schönberger et al., Citation2006a). Our finding that better awareness may also be associated with therapeutic relationships with predominantly non-clinically trained frontline rehabilitation staff suggests that perhaps it may be the implicit relational qualities of those relationships that promote better awareness rather than merely the specific training that clinicians such as psychologists receive. As previously mentioned, this idea is supported by the finding that high-quality spousal relationships, too, are associated with better awareness following ABI (Burridge et al., Citation2007). However, like other studies, this study did not control for the potential impact of cognitive problems. As such, future research in this area should control for the impact of cognitive problems and other factors considered to influence awareness such as mood (Dromer et al., Citation2021b). Future research would also benefit from doing so using direct measures of cognitive functioning such as those that may be available through formal and direct neuropsychological testing.

Secondly, it is noted that neither keyworker nor childhood parental attachment was found to be a moderator in this study. However, future research may refine this hypothesis and consider further how other or more current attachment patterns may impact the association between self-awareness and quality of relationships.

Finally, the PCRS used in the current study measured just one type of awareness: intellectual awareness. That is, the extent to which a person can accurately recognize and acknowledge the presence, severity, and impact of their injuries. However, there are also emergent and anticipatory forms of awareness which reflect an individual’s ability to monitor within-task performance and to anticipate problems in the future (Crosson et al., Citation1989). Given the effect of each form of awareness on rehabilitation engagement and outcomes (Brown et al., Citation2021; Robertson & Schmitter-Edgecombe, Citation2015), future research may consider using psychometric tools that assess awareness more holistically such as the Self-Awareness in Daily Life-3 Scale (SADL-3; Winkens et al., Citation2019).

Implications for clinical practice

Despite previously limited empirical research, some interventions for impaired awareness had considered strong therapeutic relationships to be part of what may help insight to improve following ABI-related disruption (Dirette, Citation2010; Sherer et al., Citation1998; Sherer & Fleming, Citation2018). Our findings may add empirical support to these interventions by endorsing strong therapeutic relationships as potential drivers of better awareness following ABI, which in turn can lead to better rehabilitation outcomes (Chesnel et al., Citation2018; Geytenbeek et al., Citation2017; Hurst et al., Citation2020; Robertson & Schmitter-Edgecombe, Citation2015). This has clinical implications for the extent to which the therapeutic relational environment is prioritized during neurorehabilitation, with our findings suggesting that therapeutic relationships with frontline rehabilitation staff, too, can be associated with better awareness. As previously mentioned, this is particularly important because not all individuals with ABI have access to or require in-depth psychological therapy (Coetzer, Citation2014). In fact, the nature of many stepped-care brain injury services is such that individuals often spend more time with frontline rehabilitation staff than with any other professional (Burke et al., Citation2020; Chouliara et al., Citation2021). This finding that self-awareness is associated with high-quality relationships with frontline staff also lends itself to the hypothesis that the quality of other types of interpersonal relationships, too, may have an impact on awareness, similar to findings on spousal relationships (Burridge et al., Citation2007). Taken together, this supports recent relational approaches to rehabilitation which encourage the bringing together of clients, their families, and key clinicians to focus more holistically on entire “brain-injured relationships’ rather than just “brain-injured individuals’ (Bowen et al., Citation2018).

Conclusion

This was the first study to investigate the association between self-awareness and quality of therapeutic relationships following ABI while controlling for the degree of cognitive problems. To the authors’ best knowledge, it was also the first to investigate attachment as a potential moderator of this association. Overall, the current findings showed that higher-quality therapeutic relationships with predominantly frontline rehabilitation staff were associated with better self-awareness in individuals following ABI. This was after controlling for the impact of cognitive problems on awareness in most models. Although attachment did not emerge as a significant moderating variable in this study, the overall findings have implications for increasing the extent to which the relational environment is prioritized during neurorehabilitation because awareness is an important determinant of injury and rehabilitation-related outcomes. In addition, considering the association between awareness and therapeutic relationships with predominantly frontline rehabilitation staff allowed a number of important preliminary conclusions to be drawn with regard to the aspects of therapeutic relationships that may be most associated with awareness, i.e., potentially non-clinically trained implicit relational qualities and processes such as collaboration, bond, or trust.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Barskova, T., & Wilz, G. (2006). Psychosocial functioning after stroke: psychometric properties of the patient competency rating scale. Brain Injury, 20(13-14), 1431–1437. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050600976317

- Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: a test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

- Belchev, Z., Levy, N., Berman, I., Levinzon, H., Hoofien, D., & Gilboa, A. (2017). Psychological traits predict impaired awareness of deficits independently of neuropsychological factors in chronic traumatic brain injury. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(3), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12134

- Belsky, J. (2002). Developmental origins of attachment styles. Attachment & Human Development, 4(2), 166–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730210157510

- Bishop, M., Kayes, N., & McPherson, K. (2021). Understanding the therapeutic alliance in stroke rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(8), 1074–1083. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1651909

- Bivona, U., Costa, A., Contrada, M., Silvestro, D., Azicnuda, E., Aloisi, M., Catania, G., Ciurli, P., Guariglia, C., & Caltagirone, C. (2019). Depression, apathy and impaired self-awareness following severe traumatic brain injury: A preliminary investigation. Brain Injury, 33(9), 1245–1256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2019.1641225

- Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085885

- Bowen, C., Palmer, S., & Yeates, G. (2018). A relational approach to rehabilitation: Thinking about relationships after brain injury. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429471483

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume I. Hogarth Press.

- Brown, L., Fish, J., Mograbi, D. C., Bellesi, G., Ashkan, K., & Morris, R. (2021). Awareness of deficit following traumatic brain injury: A systematic review of current methods of assessment. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 31(1), 154–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2019.1680393

- Burke, S., McGettrick, G., Foley, K., Manikandan, M., & Barry, S. (2020). The 2019 neuro-rehabilitation implementation framework in Ireland: Challenges for implementation and the implications for people with brain injuries. Health Policy, 124(3), 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.12.018

- Burridge, A. C., Huw Williams, W., Yates, P. J., Harris, A., & Ward, C. (2007). Spousal relationship satisfaction following acquired brain injury: The role of insight and socio-emotional skill. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 17(1), 95–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010500505070

- Cassidy, J. (1988). Child-mother attachment and the self in six-year-olds. Child Development, 59(1), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130394

- Chesnel, C., Jourdan, C., Bayen, E., Ghout, I., Darnoux, E., Azerad, S., Charanton, J., Aegerter, P., Pradat-Diehl, P., & Ruet, A. (2018). Self-awareness four years after severe traumatic brain injury: discordance between the patient’s and relative’s complaints. Results from the Paris-TBI study. Clinical Rehabilitation, 32(5), 692–704. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215517734294

- Chouliara, N., Fisher, R., Crosbie, B., Guo, B., Sprigg, N., & Walker, M. (2021). How do patients spend their time in stroke rehabilitation units in England? The REVIHR study. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(16), 2312–2319. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1697764

- Coetzer, R. (2014). Psychotherapy after acquired brain injury: Is less more? Revista Chilena de Neuropsicología, 9(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.5839/rcnp.2014.0901E.03

- Crosson, B., Barco, P. P., Velozo, C. A., Bolesta, M. M., Cooper, P. V., Werts, D., & Brobeck, T. C. (1989). Awareness and compensation in postacute head injury rehabilitation. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 4(3), 46–54. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-198909000-00008

- Deveci Şirin, H., & Şen Doğan, R. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the experiences in close relationships–relationship structures questionnaire (ECR-RS). SAGE Open, 11(1), 215824402110060–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211006056

- Dirette, D. (2010). Self-awareness Enhancement through Learning and Function (SELF): a theoretically based guideline for practice. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(7), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12759925544344

- Doyle, C., & Cicchetti, D. (2017). From the cradle to the grave: The effect of adverse caregiving environments on attachment and relationships throughout the lifespan. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 24(2), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12192

- Dromer, E., Kheloufi, L., & Azouvi, P. (2021b). Impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Part 2. Consequences and predictors of poor self-awareness. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 64(5), 101542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2021.101542

- Dromer, E., Kheloufi, L., & Azouvi, P. (2021). Impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. Part 1: assessment, clinical aspects and recovery. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 64(5), 101468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2020.101468

- Egozi, S., Talia, A., Wiseman, H., & Tishby, O. (2023). The experience of closeness and distance in the therapeutic relationship of patients with different attachment classifications: an exploration of prototypical cases. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 14, 1029783. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1029783

- Elanjithara, T., McIntosh, C., Ramos, S. D., Rogish, M., & Coetzer, R. (2022, May 26-27). Self-awareness of deficits following brain injury: Implications for mental capacity and recovery. The 35th British Neuropsychiatry Annual Conference, London.

- E.M. (1970). Review: Attachment and loss. Volume 1: Attachment. International Psycho-analytic Library by John Bowlby. The British Journal of Criminology, 10(2), 190–192.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Fleming, J. M., Strong, J., & Ashton, R. (1996). Self-awareness of deficits in adults with traumatic brain injury: How best to measure? Brain Injury, 10(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/026990596124674

- Fraley, R. C., Heffernan, M. E., Vicary, A. M., & Brumbaugh, C. C. (2011). The Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire: A method for assessing attachment orientations across relationships. Psychological Assessment, 23(3), 615–625. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022898

- Fraley, R. C., Hudson, N. W., Heffernan, M. E., & Segal, N. (2015). Are adult attachment styles categorical or dimensional? A taxometric analysis of general and relationship-specific attachment orientations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(2), 354–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000027

- Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2019). The development of adult attachment styles: Four lessons. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.008

- Gairing, S. K., Jäger, M., Ketteler, D., Rössler, W., & Theodoridou, A. (2011). „Scale to assess therapeutic relationships, STAR”: evaluation der deutschen skalenversion zur beurteilung der therapeutischen beziehung. Psychiatrische Praxis, 38(04), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1265979

- Geirdal, AØ, Nerdrum, P., Aasgaard, T., Misund, A., & Bonsaksen, T. (2015). The Norwegian version of the Scale To Assess the Therapeutic Relationship (N-STAR) in community mental health care: Development and pilot study. International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation, 22(5), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijtr.2015.22.5.217

- Geytenbeek, M., Fleming, J., Doig, E., & Ownsworth, T. (2017). The occurrence of early impaired self-awareness after traumatic brain injury and its relationship with emotional distress and psychosocial functioning. Brain Injury, 31(13-14), 1791–1798. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1346297

- Gillath, O., & Karantzas, G. (2015). Insights into the formation of attachment bonds from a social network perspective. In V. Zayas, & C. Hazan (Eds.), Bases of adult attachment: Linking brain, mind and behavior (pp. 131–156). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9622-9

- Goodvin, R., Meyer, S., Thompson, R. A., & Hayes, R. (2008). Self-understanding in early childhood: Associations with child attachment security and maternal negative affect. Attachment & Human Development, 10(4), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730802461466

- Gordon, C., Ellis-Hill, C., Dewar, B., & Watkins, C. (2022). Knowing-in-action that centres humanising relationships on stroke units: an appreciative action research study. Brain Impairment, 23(1), 60–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/BrImp.2021.34

- Guerrette, M.-C., & McKerral, M. (2021). Validation of the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory-4 (MPAI-4) and reference norms in a French-Canadian population with traumatic brain injury receiving rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 44(18), 5250–5256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.1924882

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press. (3rd ed).

- Hellebrekers, D., Winkens, I., Kruiper, S., & Van Heugten, C. (2017). Psychometric properties of the awareness questionnaire, patient competency rating scale and Dysexecutive Questionnaire in patients with acquired brain injury. Brain Injury, 31(11), 1469–1478. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1377350

- Heredia-Callejón, A., García-Pérez, P., Armenta-Peinado, J. A., Infantes-Rosales, MÁ, & Rodríguez-Martínez, M. C. (2023). Influence of the therapeutic alliance on the rehabilitation of stroke: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(13), 4266. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12134266

- Hurst, F. G., Ownsworth, T., Beadle, E., Shum, D. H., & Fleming, J. (2020). Domain-specific deficits in self-awareness and relationship to psychosocial outcomes after severe traumatic brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(5), 651–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2018.1504993

- IBM Corp. (2021). IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 28.0.

- Jarnecke, A. M., & South, S. C. (2013). Attachment orientations as mediators in the intergenerational transmission of marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(4), 550–559. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033340

- Kean, J., Malec, J. F., Altman, I. M., & Swick, S. (2011). Rasch measurement analysis of the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4) in a community-based rehabilitation sample. Journal of Neurotrauma, 28(5), 745–753. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2010.1573

- Lloyd, O., Ownsworth, T., Fleming, J., Jackson, M., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. (2021). Impaired self-awareness after pediatric traumatic brain injury: protective factor or liability? Journal of Neurotrauma, 38(5), 616–627. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2020.7191

- Loos, S., Kilian, R., Becker, T., Janssen, B., Freyberger, H., Spiessl, H., Grempler, J., Priebe, S., & Puschner, B. (2012). Psychometric properties of the German version of the Scale to Assess the Therapeutic Relationship in community mental health care (D-STAR). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(4), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000105

- Lustig, D. C., Strauser, D. R., Weems, G. H., Donnell, C. M., & Smith, L. D. (2003). Traumatic brain injury and rehabilitation outcomes: Does the working alliance make a difference? Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 34(4), 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1891/0047-2220.34.4.30

- Mahoney, D., Gutman, S. A., & Gillen, G. (2019). A scoping review of self-awareness instruments for acquired brain injury. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 7(2), 3. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1529

- Malec, J. F., Kean, J., Altman, I. M., & Swick, S. (2012). Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory: Comparing psychometrics in cerebrovascular accident to traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(12), 2271–2275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.06.013

- Malec, J. F., & Lezak, M. D. (2008). Manual for the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (MPAI-4) for adults, children and adolescents. The Center for Outcome Measurement in Brain Injury. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.628.1750

- Malec, J. F., & Moessner, A. M. (2000). Self-awareness, distress, and postacute rehabilitation outcome. Rehabilitation Psychology, 45(3), 227–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0090-5550.45.3.227

- Marascuilo, L. A., & McSweeney, M. (1977). Nonparametric and distribution-free methods for the social sciences. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Matsunaga, A., Yamaguchi, S., Sawada, U., Shiozawa, T., & Fujii, C. (2019). Psychometric properties of scale to assess the therapeutic relationship—JapaneseVersion (STAR-J). Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 575. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00575

- McCabe, C., Sica, A., Doody, N., & Fortune, D. G. (2023). Self-awareness and quality of relationships after acquired brain injury: Systematic review without meta-analysis (SWiM). Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2023.2186437

- McGuire-Snieckus, R., McCabe, R., Catty, J., Hansson, L., & Priebe, S. (2007). A new Scale to Assess the Therapeutic Relationship in community mental health care: STAR. Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706009299

- Mikulincer, M., & Selinger, M. (2001). The interplay between attachment and affiliation systems in adolescents’ same-sex friendships: The role of attachment style. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 18(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407501181004

- Moreira, H., Martins, T., Gouveia, M. J., & Canavarro, M. C. (2015). Assessing adult attachment across different contexts: Validation of the Portuguese version of the experiences in close relationships–relationship structures questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 97(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2014.950377

- Neal, J. W., & Greenwald, M. (2022). Self-Awareness and therapeutic alliance in speech-language treatment of traumatic brain injury. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 25, 757–767. https://doi.org/10.1080/17549507.2022.2123041

- Ownsworth, T., Clare, L., & Morris, R. (2006). An integrated biopsychosocial approach to understanding awareness deficits in Alzheimer's disease and brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 16(4), 415–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010500505641

- Pavlovic, D., Pekic, S., Stojanovic, M., & Popovic, V. (2019). Traumatic brain injury: neuropathological, neurocognitive and neurobehavioral sequelae. Pituitary, 22(3), 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-019-00957-9

- Pipp, S., Easterbrooks, M. A., & Harmon, R. J. (1992). The relation between attachment and knowledge of self and mother in One-to three-year-Old infants. Child Development, 63(3), 738–750. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01658.x

- Prigatano, G. P., Altman, I. M., & O’Brien, K. P. (1990). Behavioral limitations that traumatic-brain-injured patients tend to underestimate. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 4(2), 163-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854049008401509

- Prigatano, G. P., & Fordyce, D. J. (1986). Cognitive dysfunction and psychosocial adjustment after brain injury. In G. P. Prigatano, D. J. Fordyce, H. K. Zeiner, J. R. Rouceche, M. Pepping, & B. C. Woods (Eds.), Neuropsychological rehabilitation after brain injury (pp. 96–118). John Hopkins University Press.

- Prigatano, G. P., & Klonoff, P. S. (1998). A clinician's rating scale for evaluating impaired. Self-awareness and denial of disability after brain injury. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 12(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1076/clin.12.1.56.1721

- Robertson, K., & Schmitter-Edgecombe, M. (2015). Self-awareness and traumatic brain injury outcome. Brain Injury, 29(7-8), 848–858. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2015.1005135

- Rocha, G. M. A. d., Peixoto, E. M., Nakano, T. d. C., Motta, I. F. d., & Wiethaeuper, D. (2017). The Experiences in Close Relationships - Relationship Structures Questionnaire (ECR-RS): validity evidence and reliability. Psico-USF, 22(1), 121-132. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712017220111

- Rosen, L. H., & Patterson, M. M. (2011). The self and identity. In M. K. Underwood, & L. H. Rosen (Eds.), Social development: Relationships in infancy, childhood, and adolescence (pp. 73–100). The Guilford Press.

- Rowlands, L., Coetzer, R., & Turnbull, O. H. (2020). Building the bond: Predictors of the alliance in neurorehabilitation. Neurorehabilitation, 46(3), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-193005

- Salas, C. E. (2012). Surviving catastrophic reaction after brain injury: The use of self-regulation and self-other regulation. Neuropsychoanalysis, 14(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/15294145.2012.10773691

- Sansonetti, D., Fleming, J., Patterson, F., & Lannin, N. A. (2021). Conceptualization of self-awareness in adults with acquired brain injury: A qualitative systematic review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(8), 1726–1773. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.1924794

- Sarling, A., Jansson, B., Englén, M., Bjärtå, A., Rondung, E., & Sundin, Ö. (2021). Psychometric properties of the Swedish version of the experiences in close relationships – relationship structures questionnaire (ECR-RS global nine-item version). Cogent Psychology, 8(1), 1926080. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2021.1926080

- Schönberger, M., Humle, F., & Teasdale, T. W. (2006a). The development of the therapeutic working alliance, patients’ awareness and their compliance during the process of brain injury rehabilitation. Brain Injury, 20(4), 445–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050600664772