ABSTRACT

Effective interventions that facilitate adjustment following acquired brain injury (ABI) are needed to improve long-term outcomes and meaningful reengagement in life. VaLiANT is an 8-week group intervention that combines cognitive rehabilitation with Acceptance and Commitment therapy to improve valued living, wellbeing, and adjustment. This study explored participant experiences of VaLiANT to optimize its ongoing development. This included characterization of individually meaningful treatment outcomes, mechanisms of action, and intervention acceptability. Qualitative interviews and quantitative ratings were collected from 39 ABI survivors (Mage = 52, SD = 15; 54% stroke) following their participation in VaLiANT. Participants reported diverse outcomes which resulted in three themes being generated following reflexive thematic analysis. “A fuller toolkit for life with brain injury” indicated increased strategy usage and better daily functioning; “The value of connection and belonging” captured the importance of social experiences in shaping recovery; and “Finding the me I can be” represented cognitive, behavioural, and emotional aspects of identity reconstruction post-ABI. The content and delivery of the intervention were rated highly but participants desired greater follow-up and tailoring of the intervention. Overall, VaLiANT appears to facilitate adjustment through several mechanisms, but greater intervention individualization and dosage may be required to enhance the treatment impact.

Introduction

Survivors of acquired brain injury (ABI) commonly experience lasting changes in cognitive and emotional functioning which negatively impact daily activities, participation in meaningful life roles, and overall wellbeing and quality of life (Draper et al., Citation2007; Kutlubaev & Hackett, Citation2014; Stolwyk et al., Citation2021; Wood & Rutterford, Citation2006). This can lead to significant changes in self-identity with an associated loss of direction and meaning in life (Carroll & Coetzer, Citation2011; Shipley et al., Citation2018). Many intervention approaches do not adequately address this whole-person impact of ABI and remain focused on addressing specific impairments in isolation. For example, cognitive rehabilitation can improve cognitive functioning following ABI (Velikonja et al., Citation2023; Withiel et al., Citation2019) but these interventions typically do not improve meaningful participation, quality of life, or adjustment (Elliott & Parente, Citation2014; Wang et al., Citation2018).

In contrast, growing evidence suggests that integrated interventions that simultaneously target cognitive and emotional changes can consistently improve these broader outcomes (Davies et al., Citation2023). For example, intensive holistic interventions result in ongoing improvements beyond the impairment level up to three years post-treatment, reduce the need for additional therapeutic supports, and appear more effective than standard multidisciplinary rehabilitation (Cicerone et al., Citation2008; Holleman et al., Citation2018; Shany-Ur et al., Citation2020). However, delivery of these interventions requires substantial resources and time due to their intensive nature (e.g., 10 months of treatment, 5 + hours daily; Shany-Ur et al., Citation2020) which limits their implementation in many healthcare systems.

Therefore, there is a need to develop and evaluate a briefer and more efficiently delivered holistic intervention. VaLiANT (Valued Living After Neurological Trauma) is a novel 8-week group intervention for adult survivors of ABI and other acquired neurological conditions that combines cognitive rehabilitation with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) to facilitate adjustment to brain injury, increase engagement in meaningful behaviours (valued living), and improve quality of life and overall wellbeing. Our Phase I single case experimental design supported the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, with reliable improvements identified across a range of secondary outcome measures (Sathananthan, Dimech-Betancourt, et al., Citation2022). A Phase II pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) has recently been completed which further supported the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy potential of VaLiANT (Sathananthan et al., Citationunder review). Compared to treatment-as-usual, VaLiANT did not improve the primary outcome of wellbeing. However, VaLiANT resulted in medium reductions in anxiety and stress symptoms, small-medium improvements in psychological flexibility, and greater proportions of reliable improvement for valued living and self-identity.

In addition to establishing efficacy through clinical trials, the Medical Research Council guidelines for developing complex interventions highlight the importance of understanding participant experiences with the intervention. This involves identifying individually meaningful treatment outcomes, the mechanisms underpinning these outcomes, contextual factors influencing treatment responses, and the acceptability of intervention content and delivery (Moore et al., Citation2015; Sekhon et al., Citation2017; Skivington et al., Citation2021). Therefore, this mixed-methods study served as an in-depth evaluation of VaLiANT to complement and aid in the interpretation of the main trial results and to assist in the refinement of the intervention for future delivery and evaluation. We aimed to:

characterize participants’ experiences and ideas about the value and therapeutic impact of the intervention beyond trial outcome measures.

identify potential mechanisms of action within the intervention that contributed towards therapeutic outcomes.

explore the acceptability of the intervention components and delivery.

identify factors that participants recognized as important for the implementation or success of the intervention.

Method

Research design

This study utilized a mixed methods design that was primarily qualitative with embedded quantitative elements (QUAL + quan; Fetters et al., Citation2013; Schoonenboom & Johnson, Citation2017). The data were collected simultaneously and interpreted together, and the study is reported in line with the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (CORE-Q; Tong et al., Citation2007).

Participants

Participants were community-dwelling adults with ABI. Inclusion criteria required individuals to be at least 3 months post-brain injury with ongoing cognitive and/or emotional difficulties impacting meaningful participation (self- or informant-reported). Individuals with potentially progressive neurological conditions (e.g., multiple sclerosis; MS, brain tumour) were eligible providing they were in a stable period of remission with no new symptoms or disease progression in the last 12-months. Individuals with pre-existing intellectual disability, severe psychiatric disorders, comorbid neurodegenerative disorders, insufficient cognitive and/or language abilities to complete outcome assessments or participate in the group, or who were unable to attend the program in-person (or via telehealth during COVID-19 related restrictions) were excluded. We included participants who had completed the VaLiANT intervention as part of our Phase I single case experimental design (n = 10; Sathananthan, Dimech-Betancourt, et al., Citation2022) or Phase II randomized controlled trial (n = 29; Sathananthan et al., Citationunder review). A sample size of approximately 25 was initially estimated as being sufficient to capture a range of opinions and depth based on similar qualitative studies of rehabilitation interventions (Lawson et al., Citation2022; Ramirez-Hernandez et al., Citation2022). However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in methodological changes to the intervention delivery (e.g., shifting to telehealth/blended delivery). As such, data collection was extended to reach information power with 39 interviews sufficiently capturing participant experiences (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). Individuals were invited to participate in the interview during a follow-up assessment after completion of the VaLiANT intervention. To capture a range of opinions and identify barriers to treatment engagement, those with low intervention attendance were not excluded providing they had attended at least one VaLiANT session. Participants were not compensated for their time.

Intervention

VaLiANT is an 8-week group intervention that aims to improve meaningful participation, wellbeing, and adjustment following ABI. It focuses on reconnecting participants to what gives their lives a sense of meaning by integrating cognitive rehabilitation and ACT techniques to target barriers to valued living. Each weekly session runs for two hours and involves values clarification exercises, identification of weekly committed actions or SMART goals in line with personal values, psychoeducation, teaching of cognitive compensatory and emotion regulation strategies, group discussion and sharing, and homework setting. All intervention sessions were facilitated by a senior clinical neuropsychologist (DW) with support from two provisionally registered psychologists. Group sizes ranged from three to eight participants and were delivered in-person at the La Trobe University Psychology Clinic before transitioning to telehealth/blended delivery during the RCT after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Detailed information on the VaLiANT intervention and pandemic-related methodological changes are described in the trial protocol (Sathananthan, Morris, et al., Citation2022).

Materials

Sample characterization included pre-intervention assessment of mood with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983) and of cognitive functioning with the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (Schmidt, Citation1996), Trail Making Test with the oral version substituted during telehealth delivery (Ricker & Axelrod, Citation1994; Tombaugh, Citation2004), and Controlled Oral Word Association test which was administered to RCT participants only (Lezak, Citation1995).

Semi-structured interviews with an embedded quantitative survey were used to explore each participant’s individual experience of VaLiANT while also drawing out their feedback on different elements of the intervention and its delivery. The purpose of the interview was explained to participants as gaining feedback to aid in understanding of what was useful from VaLiANT while helping refine the intervention for future delivery. Interviews were opened by asking participants to describe their overall experience of the intervention and whether it was helpful. Subsequent prompts explored which aspects of the intervention were helpful and why, whether participants were integrating strategies from VaLiANT into their daily lives, areas for improvement, and overall satisfaction with the intervention. Following the onset of COVID-19, three interview prompts were added to ask about telehealth delivery. The interviewing style was kept open and could be tailored to allow the interviewer to pursue lines of questioning relevant to each individual or to seek more detail on comments made by each participant. To support those with cognitive and/or communication difficulties, the interview questions and prompts were provided both in written and oral format, repeated and simplified/paraphrased if needed, and examples were used to remind participants of specific aspects of the intervention for which feedback was sought.

Within the interview, participants also completed a quantitative survey to prompt further feedback on the intervention. This included two general questions relating to satisfaction/helpfulness of the intervention rated on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., please rate how helpful you found the VaLiANT intervention; Not at all helpful 1 – Very helpful 5). Participants also completed a 24-item checklist that listed different components of VaLiANT (e.g., values clarification exercises) and asked participants to tick whether they found that component helpful. Finally, participants completed a 13-item survey relating to the general delivery of the intervention (e.g., too much information was delivered in each session) rated on a 5-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Quantitative ratings were completed within the interview to allow for elaboration and clarification on the ratings, which were included in the transcripts. Appendix reflects the layout of the interview schedule and quantitative items which could be flexibly adapted to follow the participants’ line of conversation providing all topics were covered. The quantitative items were generally completed once the interview topics had been covered.

Data collection

Ethics approval was obtained from the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC #18423) for both studies from which participants were recruited, and each participant provided informed consent. Data collection occurred between April 2019 – August 2021. Interviews were conducted individually, either in-person at the La Trobe University Psychology Clinic (n = 12) or in the participant’s home (n = 5), or via videoconferencing following the onset of COVID-19 (n = 22). The time between treatment and collection of the interview varied depending on the original study and treatment condition. Participants from the single case experimental design study and RCT waitlist control condition completed the interview 1–2 weeks following treatment (those in the latter condition received the intervention after their final outcome assessment for the trial). Those in the RCT treatment condition completed the interview 8–9 weeks following treatment to prevent unblinding of the outcome assessor during their post-intervention outcome assessment. All interviews were conducted at the end of an outcome assessment by one male and three female provisionally or generally registered psychologists with postgraduate training in Clinical Neuropsychology (NS = 14 interviews, HM = 16, BDM = 5, KB = 4). Before conducting interviews, they were familiarized with the interview schedule and provided opportunities to observe recordings of previous interviews to facilitate learning. NS was involved with the delivery of some VaLiANT groups but did not conduct interviews for those participants, and participants had no relationships with the interviewers prior to their involvement in the research. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription company before being checked for accuracy.

Data analysis

Analysis of the transcripts was primarily guided by Braun and Clarke's reflexive thematic analysis approach to characterize experiential aspects of the intervention and to gain a deeper understanding of the change processes and individual therapeutic outcomes (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2022). We adopted a critical realist orientation to the data which is compatible with reflexive thematic methodologies (Fryer, Citation2022; Wiltshire & Ronkainen, Citation2021). This allowed for coding to be conducted in a data-driven and reflexive manner to characterize participant experiences while also supporting the development of a deeper understanding of VaLiANT (Fletcher, Citation2017). In the context of the current study, analysis and interpretation positioned each participant’s experience as true to them while also interpreting these experiences through theoretical assumptions of how the intervention worked (e.g., contextual behavioural theories underpinning ACT; compensatory approaches to cognitive rehabilitation) and prior knowledge of rehabilitation and theory relating to brain injury (e.g., theories of identity reconstruction) to identify underlying causal mechanisms that contributed towards meaningful outcomes. We considered this analytic orientation and approach to be the most pragmatic in answering our research questions.

For aims 1 and 2, relating to participants’ reported experiences of the intervention and potential mechanisms of action, data were coded both inductively and deductively using a mixture of semantic and more interpretative/latent codes with the generated themes capturing core meanings shared across transcripts. Analysis shifted between immersion and familiarization with the data, extensive coding, theme generation, and review. For aims 3 and 4, relating to the acceptability of the content and delivery of the intervention, a “codebook” thematic analysis approach was used as we sought to capture predefined information relating to specific components of the intervention (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). This second approach was primarily deductive using semantic coding, with themes representing domain summaries of feedback relating to different intervention components. These feedback data were supplemented by the quantitative ratings completed during the interview, which were analysed using descriptive statistics.

Coding was conducted over three successive rounds by the first author (NS) using NVivo12 (QSR international, Citation2021). After each round, the code labels, descriptions, and codebook structure were discussed and refined with DW to encourage reflexivity. Theme generation occurred between NS, DW, and EM. The initial themes were collapsed, expanded, and/or refined during a subsequent meeting and several follow-up discussions to improve their coherence. The researchers drew on their experiences of designing and delivering VaLiANT and their clinical expertise in ACT and cognitive rehabilitation during this process to develop a richer analysis of the data. The structure and interpretation of these themes were reviewed and discussed by all authors to triangulate perspectives before finalization.

Results

Individual participant demographic and injury-related information is presented in . Participants were 39 community-dwelling adults (Mage = 51.72, SD = 15.49; 59% male) who were predominately Caucasian. Five spoke English as a second language and none identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander. Brain injury aetiology mostly included stroke (54%) and traumatic brain injury (23%). Those with MS (8%) were in a stable period of remission at study entry with no change in MS status during the study period. Time since injury was particularly long for some ABI aetiologies (e.g., multiple sclerosis, brain tumour) resulting in high variability (Myears = 6.94, Mdnyears = 4.21, SD = 9.17). Most participants (32/39; 82%) self-reported elevated anxiety and/or depression symptoms (>7) during their baseline assessment and over half the sample (22/39; 56%) displayed cognitive impairment on at least one baseline cognitive measure (1.5SD below the normative mean). Participants attended 7.3/8 intervention sessions on average and delivery modality varied between completely in-person (44%), completely telehealth (28%), and blended delivery that was predominately in-person (28%).

Table 1. Participant demographic and injury information.

No individuals who were invited to participate in the interview refused. Participants expressed a breadth of perspectives and experiences during their interviews, covering direct feedback on the intervention, their personal experience of the intervention, life with brain injury more generally, and the impact of the intervention on aspects of their recovery or functioning. The richness of information and amount of feedback varied between interviews and appeared to be influenced by individual participant characteristics (i.e., memory impairment, treatment engagement). Interviews conducted immediately post-intervention tended to include more granular feedback on intervention components, while interviews at the 8-week follow-up timepoint included more reflections on the broader impact of VaLiANT and experience of integrating the strategies into daily life. Interviews varied from 5–54 min (median length 22 min; 85% of interviews were over 15 min).

Qualitative findings

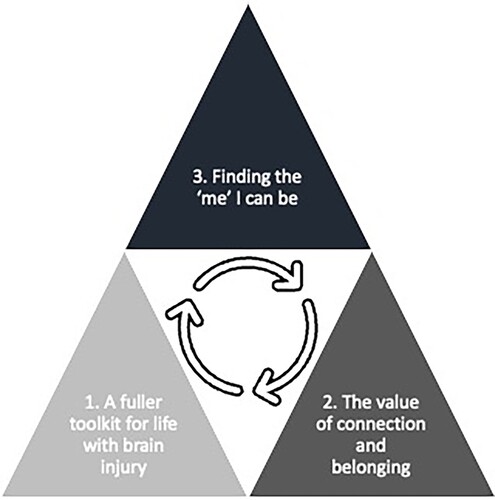

Reflexive thematic analysis resulted in the generation of three final themes. (1) “A fuller toolkit for life with brain injury” represented increased strategy usage which led to better daily functioning and management of ABI-related difficulties. (2) “The value of connection and belonging” captured how social experiences, particularly within VaLiANT, shaped recovery and self-identity following ABI. (3) “Finding the ‘me’ I can be” represented aspects of identity reconstruction and behavioural adjustment. It was best represented by three subthemes: (i) “Understanding who I am now”, (ii) “Exploring new possibilities”, and (iii) “Noticing a shift in feeling”. depicts the conceptualized relationship between the three main themes as a hierarchical but interacting model whereby changes in functioning and strategy usage (theme 1) and social connection (theme 2) contributed to changes in adjustment (theme 3). This adjustment process then reinforced participant’s new behaviours and their orientation towards social connection. Qualitative themes are discussed in detail below with supporting data extracts (edited for brevity and clarity).

Figure 1. Conceptual model of reflexive thematic themes.

A fuller toolkit for life with brain injury (theme 1)

This theme captured participants’ reflections on how VaLiANT had provided them with a flexible suite of tools that helped them better manage their lives with brain injury. The strategies taught within the program were identified as either being useful in helping improve daily functioning through better management of ABI-related symptoms, or helping improve coping with difficult emotions and thoughts that arose due to ABI-related changes. This included strategies to support the management of cognitive symptoms, sleep and fatigue difficulties, mood symptoms or frustration, and changes in relationships and communication:

I’ve downloaded the mindfulness body scan exercise. I have used that in between meetings at work. I’ve recognised that it’s almost like having a little rest … it helps me keep going. (Charlotte, 49)

It was good having information specifically related to my condition, rather than just general information about sleep and diet. (Zoe, 35)

It was useful to identify my barriers, because if there are strategies or ways of minimising them it can keep me on my goals. (Madison, 49)

I find I’m doing it each time I set a new goal or want to tweak the direction of things. I use that framework and think, ‘is this something I have control over? Or are there barriers blocking my path? (Mary, 65)

I just feel the group has taught us how to deal with different areas of life. It has covered areas such as social or physical or mental, different areas of your personal life, and how you can deal with problems that occur in these areas as well. (Chloe, 20)

The value of connection and belonging (theme 2)

This theme captured how social interactions and connections shaped the experience of brain injury and influenced recovery and adjustment. Many participants identified significant changes in their day-to-day social functioning and a reduction in their sense of connection following their brain injury. This was often characterized by loneliness and isolation:

That’s one thing that I’ve missed out on for too long, contact with other people. (Noah, 41)

A common thing I hear from family or friends who haven’t got brain injury is ‘oh you’re too hard on yourself.’ It feels like being invalidated. I still feel the deficits and you’re not acknowledging it. (Amelia, 26)

I’ve got two adult children who do not allow me the grace of having an ABI and that hurts. They don’t trust me because I’m a bit unpredictable now. (Mary, 65)

In one session someone said ‘I feel quite hard on myself and frustrated because where I am is not where I was before, and it feels like a definite sense of loss’. That was the first time I’ve heard someone say what I’ve been feeling for the last decade. (Amelia, 26)

You learn that you’re not alone and not to blame yourself for the injury because it could happen to the most fit person in the world. It doesn’t discriminate. (Ethan, 63)

I feel like it was rushed and we didn't really get to know each other, to feel each other. That connection is important because we don’t have that connection - what we feel as people with strokes is so far away from people that live life normally. Getting to know one another gives us strength. (Grace, 50)

There’s the chance of actually forming some sort of friendship with the people that were in the group. One of the participants has got everybody’s email. So in time she’ll organise meeting at a coffee shop. (Matthew, 40)

Telehealth is less pleasant than meeting someone in-person because you feel a deeper connection if you see them face-to-face. (Chloe, 20)

That session made me talk to people about what struggles I do have. Helping them understand that sometimes I might forget things. I’m not being ignorant, I just can’t remember. (Luke, 55)

I was impressed with the strategies that she used. Listening to her talk about them week after week, I started using them and they were helpful. (Olivia, 49)

Finding the “me” I can be (theme 3)

This theme captured various aspects of identity reconstruction and adjustment to brain injury that participants described due to participation in VaLiANT. It was best represented by three subthemes which reflected cognitive, behavioural, and affective elements of adjustment.

Understanding who I am now (cognitive)

This subtheme represented cognitive aspects of adjustment including shifts in self-concept and identity reconstruction. Participants discussed how significant changes in their functioning following their ABI had prevented engagement in previously important life roles, negatively impacted their self-concept, and culminated in a loss of meaning, purpose, and direction in life:

In the years since the stroke, having a sense of purpose was missing. I had to give up work and I was going through a divorce at the time. I was feeling lost, like a lot of my identity was tied up in family, in work, and in hobbies. All of those things suddenly stopped, and it felt like a huge vacuum. (David, 54)

I don’t think I mentioned the word ‘stroke’ more than five times prior to the group. It wasn’t talked about in my house. It was a chance to deal emotionally with the fact I had a stroke. (Olivia, 49)

I’m trying to be kinder to myself while going back to work and not taking on too much. On the days that I work, that’s what I do. I go to work and don’t plan anything else for those days. Things take longer now because of the fatigue. (Zoe, 35)

It showed me what was important in my life, because I was thinking about work being important. I think I’ve realised that family is more important and having fun is more important than work. (Eliza, 60)

It was good to be in a group with other people, and it was good to see that I was in better shape than a lot of the other people there. I could appreciate my situation wasn’t as bad as some of the other people. (Joseph, 57)

Exploring new possibilities (behavioural)

This subtheme captured behavioural aspects of adjustment including participants adapting their behaviour to accommodate their limitations, engaging in new meaningful behaviours, and having an increased sense of agency and control over the direction of their life. Several participants described new behaviours that they were engaging in which gave them a sense of purpose or that aligned with values that they had identified during VaLiANT:

I’m taking things less seriously and I’m having fun. There was one participant who came in with colourful clothes. Having fun things really stuck so I bought some really colourful leggings that I wouldn’t have normally done. I care less now about what other people think. (Eliza, 60)

I’m making sure I take time out for me which I wasn’t really doing. Now I feel all right about going and just having to lie down for half an hour, then coming back to everything. I wasn’t doing that before and everything was getting on top of me. (Victoria, 53)

My weakness is cooking, but one of my homework tasks was to cook a vegan meal for my family. It went down well. I had to go and do it because it was part of my homework. Now I’ve got the confidence to go and do it a second time. (Oliver, 62)

During the program I had the epiphany that my children were the negative passengers on my bus. I love them but they are distracting me from my goals. I now make goals that don’t include them. (Mary, 65)

The behaviours I put on my worksheet were things I wanted to achieve. I followed through and did the behaviours. I think that reflects that since my stroke I’ve come a long way and I’m on a path that’s heading in the right direction. (Daniel, 56)

Noticing a shift in feeling (affective)

This final subtheme captured how VaLiANT fostered positive growth and emotions which reinforced the behaviour change that participants were making. Several participants referenced having a deeper sense of enjoyment and fun in their lives following VaLiANT:

When I actually put aside time for leisure, I was just like ‘wow, I enjoy life more.’ I got deeper enjoyment out of my free time. (Amelia, 26)

You just want your life to change for the better. It's definitely improved my life. (Luke, 55)

When we were encouraged to pick actions for the week, it’s something I wouldn’t have done before without that encouragement. It just pushes you along. It just makes you want to better yourself. (Oliver, 62)

Don’t sign yourself off. You’re in the game. If you feel there is some hope, you work harder towards the goal to be completed. For me, I want to try and fight as hard as I can to try and achieve what is achievable. (William, 53)

Intervention acceptability and feedback

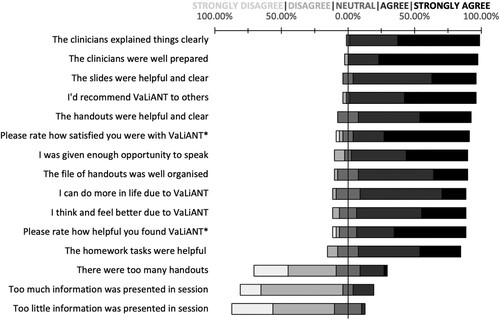

The overall acceptability of the intervention and its delivery were high, with most participants rating VaLiANT as helpful and indicating that the program had a positive impact on the way they thought, felt, and behaved (see ). Almost all participants agreed they would recommend VaLiANT to others (95%; n = 37/39):

I feel that for all the others who will have a stroke that there’s now something they can participate in that will be of help to them. (Daniel, 56)

Figure 2. Distribution of overall intervention acceptability ratings. *Indicates different response scale; please rate how satisfied you were with VaLiANT overall (extremely dissatisfied, a little bit dissatisfied, indifferent, mostly satisfied, extremely satisfied), please rate how helpful you found VaLiANT (not at all helpful, slightly helpful, somewhat helpful, moderately helpful, very helpful).

It was stuff that I got taught in the hospital when I first woke up from the coma. I’ve been doing it for years. (Penelope, 19)

I had a lot of trouble finding the energy to implement strategies because externally things are really difficult. Maybe if I attended regular therapy in conjunction with VaLiANT, I could have participated better. (Anthony, 24)

Initially it was really good, but I’m finding over time that I’m forgetting what I learnt. (Eliza, 60)

You’re looking at a screen and looking at people. It’s like watching television. It’s not the real thing and it was not personal. (Leo, 74)

When you actually see people you pick up on a lot more than when you’re just watching a screen. There’s a lot of energy that you miss out on. That’s the big downer to telehealth for this particular thing. (Joseph, 57)

I found that the scope of values that were presented on the cards was really comprehensive. There were things that I hadn’t considered that the cards presented. (Aiden, 41)

The exercise with the bus, I realised ‘oh there aren’t things that are actually holding you back. It’s usually just in your head and you holding yourself back’. (Luke, 55)

Discussion

This study served as an in-depth exploration of the VaLiANT intervention. Findings of our thematic analysis indicated that participants experienced VaLiANT as facilitating adjustment to brain injury, with multiple therapeutic components underpinning this process. While intervention content and delivery were acceptable to participants, future delivery of VaLiANT could be improved through increased tailoring of the content to individual participant needs and further follow-up to support ongoing behaviour change and adjustment following completion of the initial 8-week group program.

Table 2. Ratings of intervention components and individual sessions.

A wide range of individually meaningful outcomes were identified across the interviews. These included positive shifts in self-identity, the incorporation of injury-related limitations into self-concept, engagement in new behaviours that provided a sense of purpose, adaptation of existing behaviour to accommodate injury-related limitations, and increased wellbeing and enjoyment of life. These outcomes are consistent with existing models of adjustment to brain injury. For example, adjustment is thought to include the formation of an updated post-injury self-concept that incorporates injury-related changes (Gracey et al., Citation2009). This updated identity facilitates subsequent adaptive behaviour change which allows for the pursuit of meaningful goals that are possible within injury-related limitations (Brands et al., Citation2012). Engagement in these psychological and behavioural aspects of adjustment has been strongly associated with higher wellbeing and quality of life (Carroll & Coetzer, Citation2011; Schönberger et al., Citation2014). These outcomes are also consistent with our phase II pilot RCT findings which suggested that VaLiANT may be effective at improving psychological distress, psychological flexibility, barriers to valued living, and self-identity, although improvements in wellbeing or quality of life were not identified (Sathananthan et al., Citationunder review). Taken together, these findings suggest that VaLiANT may help some individuals engage in different aspects of the adjustment process.

Valued living appeared to be a key mechanism underpinning these positive outcomes. Participant experiences suggested that exploring values-based action helped them identify new ways of expressing important aspects of their identity within post-injury capabilities (e.g., returning to work in a less demanding role). Results also suggested that values work promoted a reprioritization process as some individuals redefined the important aspects of their identity (e.g., choosing not to return to work to focus on family instead). Linking core values to these new/adapted behaviours may have increased the intrinsic reward of engaging in them, even if they represented a change from pre-injury behavioural expressions of self-identity (Arch & Craske, Citation2008; Van Bost et al., Citation2020). From an ACT perspective, this may reflect defusion from self-as-content, whereby connecting to values results in a more flexible sense of self due to the loosening of pre-injury self-conceptualizations. Values work may therefore facilitate adjustment by promoting connection to a deeper and more enduring self-identity that can guide engagement in meaningful behaviour despite the presence of persistent limitations.

Social connection also appeared to be an important treatment mechanism. Participants rated positive social connection with other group members as the most helpful intervention component and described how this connection reduced feelings of isolation, validated their experience of ABI, helped them make sense of their own recovery, and inspired behaviour change. Similar benefits have been reported following other group rehabilitation programs (Large et al., Citation2020; Tulip et al., Citation2020; Withiel et al., Citation2020) and group connection following ABI is linked to psychological growth particularly when there is a strong sense of belonging or identification with other group members (Griffin et al., Citation2022; Lyon et al., Citation2021). In contrast, isolation and invalidating social experiences post-ABI have been shown to reduce self-worth and reinforce the discrepancy between an individual’s pre- and post-injury identity (Levack et al., Citation2014; Villa et al., Citation2021; William et al., Citation2014). These findings demonstrate the unique value-add of group-based rehabilitation and highlight the importance of facilitating positive social connections to improve self-identity following ABI.

Finally, positive outcomes were also linked to better management of ABI-related symptoms. Participants reported that VaLiANT increased their awareness of their injury-related limitations which guided usage of cognitive and ACT (e.g., mindfulness, self-compassion) strategies to improve daily functioning. Engagement in more effective coping around cognitive and emotional sequelae has been associated with higher self-efficacy, better acceptance of ABI, and better wellbeing and quality of life (Brands et al., Citation2014; Brands et al., Citation2019; Cicerone & Azulay, Citation2007; Yehene et al., Citation2020). The inclusion of strategies targeting both cognitive and emotional changes was also rated highly by participants in terms of usefulness. These findings largely support the rationale of incorporating both cognitive and psychological strategies in VaLiANT to promote more positive self-perceptions, management of ABI-related barriers, and to facilitate values-based behaviour change.

The overall acceptability of VaLiANT was high with most participants identifying it as helpful, well-designed, and delivered appropriately. Participant ratings supported several components of the Sekhon et al. (Citation2017) acceptability framework, including “affective attitude” (satisfaction with the intervention), “perceived effectiveness” (perceiving impact from the intervention), and “intervention coherence” (understanding intervention design/rationale), while suggesting that the “self-efficacy” component (confidence in being able to perform intervention related behaviours) could be better supported to improve overall acceptability. Specifically, the dosage and structure of the program did not adequately meet the needs of all participants. Some identified the need for increased individualization of content to their personal circumstances, more treatment sessions, or further follow-up to help consolidate content and maintain perceived progress following the intervention.

Several factors appeared to impact the treatment experience. These included significant mood disturbance which impacted behaviour change outside of sessions; significant memory/cognitive problems which reduced understanding of abstract concepts and retention of information; and telehealth delivery which reduced feelings of connectedness to other group members. This can be understood through the “capability” element of the COM-B model of behaviour change which indicates that an individual must feel physically and psychologically capable of performing a behaviour to engage in behaviour change (Michie et al., Citation2014). Some participants may need more time and support to engage in meaningful behaviour change, particularly those with characteristics that may have negatively influenced treatment engagement. Inclusion of individual and/or booster sessions alongside the 8-week VaLiANT group could improve acceptability and allow greater intervention tailoring and support over time, which may improve capability to engage in behaviour change.

This study provides several theoretical and clinical implications for the way holistic interventions are designed, delivered, and evaluated. Clinically, our findings support the rationale of integrating strategies that target different domains of functioning (e.g., cognitive, emotional, social, health) into a broader person-centred framework (e.g., valued living) to support adjustment following ABI. These findings also support valued living as a viable framework around which to organize person-centred rehabilitation, particularly given that higher valued living is linked to better long-term outcomes (Baseotto et al., Citation2022; Miller et al., Citation2023; Pais et al., Citation2019). Secondly, group connection was important but some participants noted this connection was attenuated online. Therefore, additional support may be required to facilitate group connection if delivered via telehealth. Thirdly, many of the positive outcomes reported by participants were subtle and varied between individuals. These may be difficult to capture on standard outcome questionnaires which are often narrowly defined. Qualitative paradigms can therefore add value and depth by characterizing the nuanced impact of complex holistic interventions. Finally, our themes have similarity with findings from other qualitative studies exploring the adjustment process and adjustment-related interventions following ABI (Domensino et al., Citation2022; Fadyl et al., Citation2019; Large et al., Citation2020; Salas et al., Citation2018). A qualitative meta-synthesis could be conducted to better understand how positive adjustment is facilitated by mapping themes onto existing models of adjustment and wellbeing (Gracey et al., Citation2009; Tulip et al., Citation2020). This could guide future intervention development and better measurement of these outcomes.

Our findings need to be considered in the context of certain methodological limitations. The current sample excluded individuals with moderate-severe language/communication impairments and VaLiANT’s acceptability needs to be explored in this population to identify possible accessibility issues. Exploration of participant acceptability also did not cover all components of the acceptability framework (Sekhon et al., Citation2017). “Ethicality” (whether the intervention fits with participant’s values systems), “burden” (amount of effort required to participate), and “opportunity costs” (whether benefits outweigh costs of the treatment) could be explored explicitly in the future to evaluate the acceptability of VaLiANT more comprehensively. This could also include exploration of facilitator’s experiences of delivering VaLiANT and the influence of participant ethnicity and socioeconomic status given that these factors impact treatment engagement and outcomes (Proctor et al., Citation2011; Williams et al., Citation2016). Additionally, the intervention delivery modality varied across participants resulting in differences in how certain aspects of content were delivered. Nevertheless, acceptability ratings were high regardless of delivery modality, suggesting that the different delivery modalities were all acceptable.

In conclusion, this mixed methods study provides insight into how VaLiANT influenced adjustment for some participants through the targeting of ABI-related barriers, the facilitation of valued living, and by providing the opportunity for positive social connection. Intervention outcomes could be enhanced in the future through the provision of individual and/or booster sessions in addition to the current group delivery to assist participants in maintaining progress over time. These findings add to the growing evidence supporting holistic interventions that integrate cognitive and psychological therapies in influencing outcomes related to adjustment and identity following ABI.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants who participated in the study. Thanks are also given to Hannah Miller, Katharine Baker, and Bleydy Dimech-Betancourt for their assistance in conducting the outcome assessments and collecting the data used for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arch, J. J., & Craske, M. G. (2008). Acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: Different treatments, similar mechanisms? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 15(4), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.2008.00137.x

- Baseotto, M. C., Morris, P. G., Gillespie, D. C., & Trevethan, C. T. (2022). Post-traumatic growth and value-directed living after acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(1), 84–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1798254

- Brands, I., Köhler, S., Stapert, S., Wade, D., & van Heugten, C. (2014). Influence of self-efficacy and coping on quality of life and social participation after acquired brain injury: A 1-year follow-Up study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 95(12), 2327–2334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2014.06.006

- Brands, I. M. H., Verlinden, I., & Ribbers, G. M. (2019). A study of the influence of cognitive complaints, cognitive performance and symptoms of anxiety and depression on self-efficacy in patients with acquired brain injury. Clinical Rehabilitation, 33(2), 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215518795249

- Brands, I. M., Wade, D. T., Stapert, S. Z., & van Heugten, C. M. (2012). The adaptation process following acute onset disability: An interactive two-dimensional approach applied to acquired brain injury. Clinical Rehabilitation, 26(9), 840–852. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215511432018

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000196

- Carroll, E., & Coetzer, R. (2011). Identity, grief and self-awareness after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 21(3), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2011.555972

- Cicerone, K. D., & Azulay, J. (2007). Perceived self-efficacy and life satisfaction after traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 22(5), 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HTR.0000290970.56130.81

- Cicerone, K. D., Mott, T., Azulay, J., Sharlow-Galella, M. A., Ellmo, W. J., Paradise, S., & Friel, J. C. (2008). A randomized controlled trial of holistic neuropsychologic rehabilitation after traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 89(12), 2239–2249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2008.06.017

- Davies, A., Rogers, J. M., Baker, K., Li, L., Llerena, J., das Nair, R., & Wong, D. (2023). Combined cognitive and psychological interventions improve meaningful outcomes after acquired brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-023-09625-z

- Domensino, A.-F., Verberne, D., Prince, L., Fish, J., Winegardner, J., Bateman, A., Wilson, B., Ponds, R., & van Heugten, C. (2022). Client experiences with holistic neuropsychological rehabilitation: “It is an ongoing process”. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(8), 2147–2169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.1976222

- Draper, K., Ponsford, J., & Schonberger, M. (2007). Psychosocial and emotional outcomes 10 years following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 22(5), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HTR.0000290972.63753.a7

- Elliott, M., & Parente, F. (2014). Efficacy of memory rehabilitation therapy: A meta-analysis of TBI and stroke cognitive rehabilitation literature. Brain Injury, 28(12), 1610–1616. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699052.2014.934921

- Fadyl, J. K., Theadom, A., Channon, A., & McPherson, K. M. (2019). Recovery and adaptation after traumatic brain injury in New Zealand: Longitudinal qualitative findings over the first two years. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(7), 1095–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1364653

- Fetters, M. D., Curry, L. A., & Creswell, J. W. (2013). Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research, 48(6), 2134–2156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12117

- Fletcher, A. J. (2017). Applying critical realism in qualitative research: Methodology meets method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1144401

- Fryer, T. (2022). A critical realist approach to thematic analysis: Producing causal explanations. Journal of Critical Realism, 21(4), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2022.2076776

- Gracey, F., Evans, J. J., & Malley, D. (2009). Capturing process and outcome in complex rehabilitation interventions: A “Y-shaped” model. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 19(6), 867–890. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602010903027763

- Griffin, S. M., Kinsella, E. L., Bradshaw, D., McMahon, G., Nightingale, A., Fortune, D. G., & Muldoon, O. T. (2022). New group memberships formed after an acquired brain injury and posttraumatic growth: A prospective study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(8), 2054–2076. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.2021950

- Holleman, M., Vink, M., Nijland, R., & Schmand, B. (2018). Effects of intensive neuropsychological rehabilitation for acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 28(4), 649–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2016.1210013

- Kutlubaev, M. A., & Hackett, M. L. (2014). Part II: Predictors of depression after stroke and impact of depression on stroke outcome: An updated systematic review of observational studies. International Journal of Stroke, 9(8), 1026–1036. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijs.12356

- Large, R., Samuel, V., & Morris, R. (2020). A changed reality: Experience of an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) group after stroke. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(8), 1477–1496. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2019.1589531

- Lawson, D. W., Stolwyk, R. J., Ponsford, J. L., Baker, K. S., Tran, J., & Wong, D. (2022). Acceptability of telehealth in post-stroke memory rehabilitation: A qualitative analysis. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2020.1792318

- Levack, W. M. M., Boland, P., Taylor, W. J., Siegert, R. J., Kayes, N. M., Fadyl, J. K., & McPherson, K. M. (2014). Establishing a person-centred framework of self-identity after traumatic brain injury: A grounded theory study to inform measure development. BMJ Open, 4(5), Article e004630. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004630

- Lezak, M. D. (1995). Neuropsychological assessment. Oxford University Press.

- Lyon, I., Fisher, P., & Gracey, F. (2021). “Putting a new perspective on life”: A qualitative grounded theory of posttraumatic growth following acquired brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(22), 3225–3233. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1741699

- Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. Silverback Publishing.

- Miller, L. R., Divers, R., Reed, C., Cherry, J., Patrick, A., & Calamia, M. (2023). Value-consistent rehabilitation is associated with long-term psychological flexibility and quality of life after traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2023.2256964

- Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., Moore, L., O’Cathain, A., Tinati, T., Wight, D., & Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical research council guidance. BMJ, 350(mar19 6), Article h1258. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1258

- Pais, C., Ponsford, J. L., Gould, K. R., & Wong, D. (2019). Role of valued living and associations with functional outcome following traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 29(4), 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2017.1313745

- Proctor, E., Silmere, H., Raghavan, R., Hovmand, P., Aarons, G., Bunger, A., Griffey, R., & Hensley, M. (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(2), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7

- QSR international. (2021). NVivo 12 data analysis software. (Version 12.6.1). https://lumivero.com/products/nvivo/

- Ramirez-Hernandez, D., Stolwyk, R. J., Chapman, J., & Wong, D. (2022). The experience and acceptability of smartphone reminder app training for people with acquired brain injury: A mixed methods study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(7), 1263–1290. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.1879875

- Ricker, J. H., & Axelrod, B. N. (1994). Analysis of an oral paradigm for the trail making test. Assessment, 1(1), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191194001001007

- Salas, C. E., Casassus, M., Rowlands, L., Pimm, S., & Flanagan, D. A. J. (2018). "Relating through sameness": a qualitative study of friendship and social isolation in chronic traumatic brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 28(7), 1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2016.1247730

- Sathananthan, N., Dimech-Betancourt, B., Morris, E., Vicendese, D., Knox, L., Gillanders, D., Das Nair, R., & Wong, D. (2022). A single-case experimental evaluation of a new group-based intervention to enhance adjustment to life with acquired brain injury: VaLiANT (valued living after neurological trauma). Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 32(8), 2170–2202. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.1971094

- Sathananthan, N., Morris, E. M. J., das Nair, R., Gillanders, D., Wright, B. J., & Wong, D. (under review). Evaluating the VaLiANT (Valued Living After Neurological Trauma) group intervention for improving wellbeing and adjustment to life with acquired brain injury: A pilot randomised controlled trial.

- Sathananthan, N., Morris, E. M. J., Gillanders, D., Knox, L., Dimech-Betancourt, B., Wright, B. J., das Nair, R., & Wong, D. (2022). Does integrating cognitive and psychological interventions enhance wellbeing after acquired brain injury? Study protocol for a phase II randomized controlled trial of the VaLiANT (valued living after neurological trauma) group program. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 2, Article 815111. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2021.815111

- Schmidt, M. (1996). Rey auditory verbal learning test: A handbook. Western Psychological Services.

- Schönberger, M., Ponsford, J., McKay, A., Wong, D., Spitz, G., Harrington, H., & Mealings, M. (2014). Development and predictors of psychological adjustment during the course of community-based rehabilitation of traumatic brain injury: A preliminary study. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 24(2), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2013.878252

- Schoonenboom, J., & Johnson, R. B. (2017). How to construct a mixed methods research design. Cologne Journal for Sociology and Social Psychology, 69(2), 107–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-017-0454-1

- Sekhon, M., Cartwright, M., & Francis, J. J. (2017). Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), Article 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

- Shany-Ur, T., Bloch, A., Salomon-Shushan, T., Bar-Lev, N., Sharoni, L., & Hoofien, D. (2020). Efficacy of postacute neuropsychological rehabilitation for patients with acquired brain injuries is maintained in the long-term. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 26(1), 130–141. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617719001024

- Shipley, J., Luker, J., Thijs, V., & Bernhardt, J. (2018). The personal and social experiences of community-dwelling younger adults after stroke in Australia: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open, 8(12), Article e023525. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023525

- Skivington, K., Matthews, L., Simpson, S. A., Craig, P., Baird, J., Blazeby, J. M., Boyd, K. A., Craig, N., French, D. P., McIntosh, E., Petticrew, M., Rycroft-Malone, J., White, M., & Moore, L. (2021). A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: Update of medical research council guidance. BMJ, 374, Article n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061

- Stolwyk, R. J., Mihaljcic, T., Wong, D. K., Chapman, J. E., & Rogers, J. M. (2021). Poststroke cognitive impairment negatively impacts activity and participation outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke, 52(2), 748–760. https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032215

- Tombaugh, T. N. (2004). Trail making test A and B: Normative data stratified by age and education. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 19(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0887-6177(03)00039-8

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Tulip, C., Fisher, Z., Bankhead, H., Wilkie, L., Pridmore, J., Gracey, F., Tree, J., & Kemp, A. H. (2020). Building wellbeing in people With chronic conditions: A qualitative evaluation of an 8-week positive psychotherapy intervention for people living With an acquired brain injury. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 66. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00066

- Van Bost, G., Van Damme, S., & Crombez, G. (2020). Goal reengagement is related to mental well-being, life satisfaction and acceptance in people with an acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(9), 1814–1828. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2019.1608265

- Velikonja, D., Ponsford, J., Janzen, S., Harnett, A., Patsakos, E., Kennedy, M., Togher, L., Teasell, R., McIntyre, A., Welch-West, P., Kua, A., & Bayley, M. T. (2023). INCOG 2.0 guidelines for cognitive rehabilitation following traumatic brain injury, part V: Memory. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 38(1), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0000000000000837

- Villa, D., Causer, H., & Riley, G. A. (2021). Experiences that challenge self-identity following traumatic brain injury: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(23), 3298–3314. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1743773

- Wang, S. B., Wang, Y. Y., Zhang, Q. E., Wu, S. L., Ng, C. H., Ungvari, G. S., Chen, L., Wang, C. X., Jia, F. J., & Xiang, Y. T. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for post-stroke depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 235, 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.011

- William, M. M. L., Pauline, B., William, J. T., Richard, J. S., Nicola, M. K., Joanna, K. F., & Kathryn, M. M. (2014). Establishing a person-centred framework of self-identity after traumatic brain injury: A grounded theory study to inform measure development. BMJ Open, 4(5), Article e004630. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004630

- Williams, D. R., Priest, N., & Anderson, N. B. (2016). Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health Psychology, 35(4), 407–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000242

- Wiltshire, G., & Ronkainen, N. (2021). A realist approach to thematic analysis: Making sense of qualitative data through experiential, inferential and dispositional themes. Journal of Critical Realism, 20(2), 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2021.1894909

- Withiel, T. D., Sharp, V. L., Wong, D., Ponsford, J. L., Warren, N., & Stolwyk, R. J. (2020). Understanding the experience of compensatory and restorative memory rehabilitation: A qualitative study of stroke survivors. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 30(3), 503–522. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2018.1479275

- Withiel, T. D., Wong, D., Ponsford, J. L., Cadilhac, D. A., New, P., Mihaljcic, T., & Stolwyk, R. J. (2019). Comparing memory group training and computerized cognitive training for improving memory function following stroke: A phase II randomized controlled trial. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 51(5), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2540

- Wood, R. L., & Rutterford, N. A. (2006). Demographic and cognitive predictors of long-term psychosocial outcome following traumatic brain injury. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 12(3), 350–358. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617706060498

- Yehene, E., Lichtenstern, G., Harel, Y., Druckman, E., & Sacher, Y. (2020). Self-efficacy and acceptance of disability following mild traumatic brain injury: A pilot study. Applied Neuropsychology: Adult, 27(5), 468–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/23279095.2019.1569523

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

Appendix. Qualitative interview schedule and quantitative ratings

I would like to ask you some questions about your experience with the VaLiANT group program that you recently completed. Please feel free to elaborate on any of these questions with relevant thoughts and ideas. The purpose of this interview is to learn how helpful the program is. The investigators of this program hope to use this information to improve the program in the future.

Opening question: Please describe your overall experience of VaLiANT and whether it was helpful.

Planned questions (*ask for telehealth delivery only):

What were the most helpful aspects of the VaLiANT program for you?

What were the least helpful aspects of the VaLiANT program for you?

Which strategies do you find yourself using in your daily life?

Do you have any particular suggestions to help us improve the VaLiANT program?

Do you have any other comments about your experiences in the VaLiANT program?

*How would you describe your experience doing the group via telehealth?

*Were there any positives or negatives with using telehealth for the VaLiANT program?

*How did you find the process of accessing worksheets and handouts and completing the value card sort activity online?

Planned prompts (*indicates prompts for quantitative ratings):

Can you tell me more about that?

Could you provide an example?

*Can you tell me why you provided that rating?

Quantitative items:

Please rate how helpful you found VaLiANT.

Not at all helpful

Slightly helpful

Somewhat helpful

Moderately helpful

Very helpful

Which of the following aspects of the VaLiANT program did you find helpful? (Tick all that apply):

Learning about values and how to determine what is most important to me

Doing the values card sort activity each week

Identifying and noticing your “passengers on the bus”

Doing the passengers on the bus group activity

Using SMART goals to identify committed actions in line with your values each week

Filling out the “way to valued living” worksheet each week

Identifying strengths that enable you to carry out your committed actions each week

Identifying barriers that might stop you from carrying out your committed actions each week

Learning and practising “doing” strategies (i.e., cognitive/memory/planning strategies) to address the barriers for each committed action, e.g., calendars, alarms, lists, name associations, activity schedules

Learning and practising “coping” strategies to address the barriers for each committed action, e.g., mindfulness, S.T.O.P., self-compassion

Getting a recording of the mindfulness exercise

The information on the slides

Sharing experiences and ideas with others in the group

Doing the homework tasks

Reviewing the notes and handouts

Having the opportunity to bring along a family member/friend to Session 7

Session 1 content: Getting introduced to values and valued living

Session 2 content: Learning more about sleep difficulties and fatigue

Session 3 content: Learning more about diet and exercise

Session 4 content: Learning more about ways to get involved in work, study, and community activities

Session 5 content: Learning more about participating in different leisure activities

Session 6 content: Learning more about communication strategies

Session 7 content: Learning more about how to have healthy relationships with family and friends

Session 8 content: Revising all of the values, committed actions, barriers and strategies

Please rate the following questions to indicate your opinion regarding the VaLiANT program (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree):

The clinicians were well prepared

The clinicians explained things clearly

Too much information was presented in each session

Too little information was presented in each session

The slides were helpful and clear

The handouts were helpful and clear

There were too many handouts

The handouts were well organized

I was given enough opportunity to speak and contribute to sessions

The homework tasks were appropriate and helpful

The way I think and feel is better as a result of VaLiANT

I think I can do more of the things I value in life as a result of VaLiANT

I would recommend this program to other people

In an overall, general sense, how satisfied are you with the VaLIANT group?

Extremely dissatisfied

A little bit dissatisfied

Indifferent

Mostly satisfied

Extremely satisfied