ABSTRACT

Changes in sexual functioning and wellbeing after a traumatic brain injury (TBI) are common but remain poorly addressed. Little is known about the lived experiences and perspectives of individuals with TBI. Through semi-structured interviews with individuals with TBI (n = 20), this qualitative study explored their experiences with post-TBI sexuality, along with their needs and preferences for receiving sexuality support and service delivery. Three broad themes were identified through reflexive thematic analysis of interview transcripts. First, individuals differed significantly at the start of their journeys in personal attributes, TBI-associated impacts, and comfort levels in discussing sexuality. Second, journeys, feelings, and perspectives diverged based on the nature of post-TBI sexuality. Third, whilst responses to changes and preferences for support varied widely, individuals felt that clinicians were well-placed to help them navigate this area of their lives. The impacts felt by individuals with TBI, and the infrequency of clinical discussions highlight the need for clinician education and clinically validated assessment and treatment tools to improve how post-TBI sexuality is addressed and managed.

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is one of the leading causes of disability globally, resulting in physical, cognitive, and emotional impairments that can have profound impacts on an individual’s life (Ponsford et al., Citation2014; Stocchetti & Zanier, Citation2016). Individuals with TBI have reported experiencing changes in sexuality that have been shown to persist for over a decade (Ponsford et al., Citation2014). In recent years, there has been increasing recognition of the effects that TBI has on sexuality (Fraser et al., Citation2022; Fraser et al., Citation2020; Hwang et al., Citation2021; Marier-Deschênes et al., Citation2020). However, sexuality changes that impact approximately half of individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI remain largely overlooked across research and clinical contexts (Downing & Ponsford, Citation2018; Moreno et al., Citation2013). Recognising the connections between sexuality, identity, life satisfaction, overall well-being, and the well-documented challenges that individuals with TBI face in maintaining the stability and quality of partner relationships, underscores the importance of addressing sexuality (Anderson, Citation2013; van den Broek et al., Citation2022).

Due to its broadness and complexity, sexuality can be hard to define. The working definition provided by the World Health Organization (Citation2006) refers to sexuality as a fundamental aspect of the human experience comprising multi-faceted sexual experiences beyond sexual reproduction. This could include gender identity, orientation, self-image, relationships, intimacy, eroticism, pleasure and more. However, sexuality after TBI has been predominantly approached from a physiological perspective by both researchers and clinicians, thereby failing to embrace its multifaceted and holistic nature (Moreno et al., Citation2013). In this study, sexuality is conceptualised as a combination of sexual functioning outcomes, including libido, erectile function, vaginal lubrication, and reproductive ability, along with subjective sexual wellbeing outcomes including desire, body image, communication ability, relationship quality, self-esteem and sexual efficacy (Verschuren et al., Citation2010).

Sexuality is a difficult topic to talk about in general, much less in a clinical setting. The paucity of clinical discussions on this topic is unsurprising given that health professionals are rarely given the education or training opportunities to build their skills and confidence in this area (Arango-Lasprilla et al., Citation2017; Fraser et al., Citation2021). The highly heterogeneous presentations of sexuality changes after TBI also make it challenging to address this topic well. Research suggests that most individuals experience reduced sexual outcomes or hyposexuality, and the smaller minority experience increased outcomes or hypersexuality (Fraser et al., Citation2020; Sander et al., Citation2012).

As posited by Gan’s (Citation2005) biopsychosocial model, sexuality changes arise from an intersection of relationship changes, medical and physical issues, and neuropsychological and psychological effects after brain injury. However, little is known of the exact biomechanisms for sexuality changes. The literature on the localisation of sexual function and TBI remain largely inconclusive due to the diffuse nature of TBI pathophysiology (Johnson et al., Citation2013; Moreno et al., Citation2013). Interview studies by Gill et al. (Citation2011) and O'Keeffe et al. (Citation2020) involving individuals with TBI and their uninjured partners identified possible barriers to intimacy. These included sexual difficulties, injury-related changes, emotional reactions to changes such as emotional fallout on each individual and the relationship, changes in relationship dynamic and role conflict, family issues, communication issues and social isolation.

In general, there has been little insight into the subjective experiences of both partnered and unpartnered individuals with TBI around not just sexual functioning, but sexual wellbeing outcomes as well. Despite the impacts and chronicity of post-TBI sexuality changes, research on this topic has been limited, mainly quantitative, and largely focused on sexual functioning outcomes (Hibbard et al., Citation2000; Sander et al., Citation2012; Simpson & Baguley, Citation2012). There is also a dearth of clinical options or standards for addressing and treating post-TBI sexuality issues which is likely due to the lack of knowledge around mechanisms of change and patient needs. Therefore, to better understand the nuances of the complex lived experiences of individuals with TBI around sexuality, the current study aimed to qualitatively explore TBI-related impacts on sexuality, experiences of help-seeking, and preferences of individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI around addressing sexuality with and receiving support from their health professionals.

Methods

Participants

Individuals who were previously admitted to the Epworth Acquired Brain Injury (ABI) Rehabilitation Unit for moderate-to-severe TBI and had completed the Brain Injury Questionnaire of Sexuality (BIQS; See Appendix; Stolwyk et al., Citation2013) in a longitudinal survey study (n = 2959) investigating long-term outcomes following TBI (Ponsford et al., Citation2014), were recruited by phone. Individuals who were considered by the research neuropsychology team to be cognitively capable of giving informed consent and completing a 60-minute interview, and were five or less years post-injury to maximise potential for recall of rehabilitation experiences, were included for recruitment.

Purposive sampling was utilised with the aim of representing a range of experiences based on BIQS scores (hyposexual, hypersexual, no changes). Scores of 15–44 were categorised as hyposexual changes, a score of 45 was categorised as no change, and scores of 46–75 were classified as hypersexual changes. While it was likely that these three groups would differ significantly in their experiences, it was expected that there might be commonalities in perspectives and preferences for service delivery. Identifying these could provide helpful information for clinicians when approaching patients whose nature of post-TBI sexuality experiences may not be known beforehand.

Interview participants meeting selection criteria (hyposexual, hypersexual, no changes) were randomly sampled. Recruitment was stopped at 20 participants when data were subjectively considered by the authors as sufficiently rich to address the research questions, with additional pragmatic considerations for resource and time limitations (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021; Malterud et al., Citation2015). One unpartnered participant (P16) did not respond to relationship related questions on the BIQS, and thus her total score was not available. However, she was still included in the study as the rest of her BIQS responses indicated hyposexual experiences. Prior to the study, there were no pre-existing relationships between the interviewer and participants. Six individuals declined to participate as they were either not interested in being involved in this study or were too busy to participate. Eleven individuals were not able to be contacted. None of the individuals who accepted the invitation to participate dropped out of the study at any point. See for participant characteristics.

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Measures

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were guided by an interview schedule (See Appendix). Questions on the schedule explored participants’ understanding of sexuality in general, post-TBI sexuality experiences and any changes, experiences with seeking and receiving help with sexual issues, and preferences around post-TBI sexuality discussions with their health professionals. As per a reflexive design, the interview schedule was iteratively revised throughout the interview process and was updated three times. See for the nature of post-TBI sexuality as reported by participants in the interviews, as well as initially via their BIQS scores.

Table 2. Reported nature of participants’ post-TBI sexuality.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee. One-to-one interviews were conducted by a female interviewer, JH, who is trained in quantitative interviewing and analysis. Interviews ranged between 29 and 87 minutes long (M = 45.4 minutes) and each participant was interviewed once with no non-participants present. Interviews were conducted over telephone (n = 4) and videoconference (n = 16), which were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviewer journaled observations and reflections after each interview. Participants were provided an explanatory statement before the interviews and informed that the interviewer (JH) was a graduate psychology student conducting this study as part of a wider research project to explore how sexuality after TBI can be addressed better. Participants either provided their electronic consent through an online form or verbal consent that was audio recorded.

Data analysis

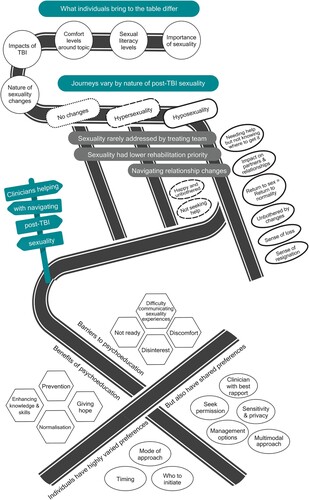

Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2022) six-phase reflexive thematic analysis process was undertaken recursively to explore patterns of meaning in the data. Data familiarisation was performed through repeated readings of transcripts by all authors. The data were semantically coded with an inductive-driven approach and managed through NVivo (Release 1.7; QSR International Pty Ltd, Citation2022). As per the recommendations for reflexive thematic analysis, member-checking and cross-coding were not performed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022; Varpio et al., Citation2017). Traditional member-checking activities were deemed inappropriate given the extensive training and knowledge required to navigate and code lengthy interview data, as well as researcher subjectivity involved in performing reflexive thematic analysis. Data were coded by a single coder, JH. In engaging in a recursive thematic analysis process, it was important to be mindful of how the subjectivity of the researchers interacts with the phenomenon being explored. The authors have witnessed the challenges faced by individuals with TBI in navigating sexual difficulties following across decades of research collectively. Additionally, JH and JP work with survivors of TBI clinically in their roles as a neuropsychology student and experienced neuropsychologist respectively. Hence, the authors acknowledge the strong inclination to emphasize sexual difficulties that were mentioned by participants in the interviews but were wary of our subjectivities. The authors navigated this by representing positive, neutral, and negative sexuality and service-related experiences in the analytical process and focused on analysing manifest content. All researchers involved in the data analysis are female, with two (JP, MD) being PhD holders who conduct psychological research, and JH undertaking doctoral training in clinical neuropsychology at the time of this study. Major themes and subthemes were developed from codes and refined four times through discussions between authors JH, JP, and MD. The research team discussed the meaning and interpretation of the codes and themes with the aim of achieving richer interpretations rather than reaching a consensus (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). A visual representation of the relationships between themes and subthemes was produced through a thematic map as seen in .

Figure 1. Thematic map of individuals’ experiences and views on sexuality after TBI.

Findings

As illustrated in the post-TBI journey roadmap of “SEX” in , three themes, including 29 subthemes, broadly captured the varied and personal post-TBI sexuality journeys and preferences for support as described by the 20 participants.

Individuals differed significantly at the start of their journeys in terms of personal attributes and TBI-associated impacts. Journeys diverged based on the nature of post-TBI sexuality. Whilst journeys were highly heterogeneous, individuals felt that clinicians were well placed to help navigate this area of their lives. They suggested possible barriers and benefits to psychoeducation, alongside shared and varied preferences around receiving sexuality support.

What individuals bring to the injury differ

There was variability between study participants in the perceived importance of sexuality, sexuality literacy levels, and comfort levels in discussing sex. The impacts of TBI were also noted as heterogeneous and multi-faceted. These factors resulted in significant variability across individuals in their sexuality journeys.

Sexual literacy levels

Most participants struggled to conceptualise and define sexuality even with prompts provided by the interviewer: “I’m not too sure. Actually, I don’t know.” (P7, Hyposexuality). This was especially so for those who rarely discuss sexuality in their personal lives: “They were never deep and meaningful conversations. It was just essentially saying to my wife, ‘Do you want to?’ or saying yes, if she says, ‘Do you want to?’” (P13, No changes). Participants’ sexual literacy levels in the broader topic of sexual functioning and wellbeing, their views on their premorbid sexuality, or on how TBI can impact sexuality were noted to vary greatly: “I wouldn’t know like, how … how things could change?” (P3, No changes). Low literacy levels and the resultant difficulties with reflecting on changes meant that a handful of participants, who initially indicated that they had not experienced any changes at the start of the interview, later realised that they had experienced hyposexual changes as the interview progressed and the topic of sexuality was explored in greater detail.

Importance of sexuality

Most participants saw sexuality as a core aspect of life that was no less important than other rehabilitation goals such as driving, work, cognitive abilities, and physical functioning. However, some acknowledged that perceived levels of importance can change across different stages of life and recovery.

As I've been starting to come good the last six months or so, in my head, I have this plan of what I'm doing, where I'm going, how I'm recovering, and the finding a partner thing is sneaking up in that process. It's not quite here, but it's gonna come more of the forefront in the coming months, no doubt, in my head. (P19, Hyposexuality)

Comfort levels around topic

Comfort levels around having discussions on sexuality or seeking help for sexual issues also differed. Low comfort levels were noted to limit help-seeking behaviours: “Some people would be too frightened to actually bring that up and wouldn’t go on a website for fear that someone could see what they’ve done.” (P9, Hyposexuality). A few participants further raised cultural norms and taboos that can impact comfort levels: “in some religions and some ethnicity and stuff like that, you don’t talk about sex.” (P9, Hyposexuality). Some participants indicated that clinicians could help by initiating the discussion: “Ideally if someone would bring it up, I think that would be better because sometimes you're too embarrassed to ask about it.” (P15, Hyposexuality)

Multi-faceted impacts of TBI

Participants spoke about the cognitive, emotional, and physical sequelae of TBI that again differed widely across the group. These led to different recovery journeys, new perspectives on life goals, and a general sense of loss from having to re-negotiate life with these sequelae: “I’m still not used to the new me, living 26 years one way and then having it change so suddenly.” (P12, Hyposexuality).

Journeys vary by nature of post-TBI sexuality

Participants’ experiences and journeys varied based on whether they experienced no changes, hyposexuality or hypersexuality after TBI as illustrated in . Hypersexuality was reported by two participants who experienced increased sexual desire and frequency of sexual activity: “basically wanting to have sex all the time. Sometimes it’s like three or four times a day.” (P11, Hypersexuality). Notably, most participants described experiencing hyposexuality in the forms of reduced sexual functioning such as reduced frequency or complete cessation of activity, reduced desire, dizziness during sex, erectile dysfunction, and anorgasmia. Reduced sexual wellbeing was also described, which included difficulties with self-image and self-worth, feeling undesirable, experiencing a loss of sexual identity, difficulties communicating their sexual needs, loss of opportunity for partnered sexual activity, and lowered sexual confidence.

... as confident as I was back then, I'd be pretty brazen about it, to be honest, but now I couldn't. I don't know how to broach it. I think a lot of that is obviously to do with my own self, just confidence and worth nowadays. (P19, Hyposexuality)

I didn’t care about him or loved him like that. I just – he kind of was giving me what I wanted and that’s all that mattered and then, as soon as I knew [the relationship and sex] was gonna stop, I was mad! (P4, Hypersexuality)

While there were commonalities as illustrated, individuals who had post-TBI sexuality changes faced unique experiences.

Unique experiences after hypersexual changes

Happy and unbothered

The two participants who experienced hypersexuality after TBI indicated that they were happy with the change when asked how it had impacted them: “I guess a little bit liberating and just happy about it. I don’t see any problems with it.” (P11, Hypersexuality). These individuals further added that they did not require additional help or support with addressing these changes.

There’s nothing bad about it that’s happened or badly impacted on me or my partner – if there were some health issues then, yes, I’d seek medical help straightaway. But there’s nothing. (P4, Hypersexuality)

Unique experiences after hyposexual changes

In contrast to participants who experienced hypersexuality, participants who experienced hyposexuality indicated some distress, although emotional reactions to hyposexual changes still differed considerably across the board.

Needing help but not knowing where to get it

Participants indicated that they were unaware of how and where to seek help and were largely left to their own devices: “I have no idea what to do, or how to do it, I got no idea.” (P19, Hyposexuality). Help-seeking behaviours also largely pertained to erectile difficulties.

Impact on partners and relationships

Participants who were partnered at the time of their accident spoke about how reduced sexuality had an impact on their partners and the relationship.

But I guess after the accident, we probably didn’t have sex for really good six to eight months maybe, and I think that was – again, not thinking I wasn’t attractive or he wasn’t attracted to me, it was just – there were so many appointments to go to and I couldn’t dress or undress myself. He had to shower me. And so, it wasn’t even like a sexual thing like you saw a naked body shower. It was just – he was generally caring for his wife. (P9, Hyposexuality)

Return to sex = return to normality

While participants were inclined to prioritise other rehabilitation outcomes over hyposexual changes, there was a shared sentiment that sex is a part of “normal life” (P7, Hyposexuality). P9 spoke about how she had not been particularly bothered but felt relief after returning to sexual activity for the first time since her injury:

It was like, to be honest, old [me] was back – I remember laughing and – the next day, I sang again. I hadn’t sung for a long time. ‘Cause I remember my kids actually said at the time, “So nice to hear you sing again, mum.” So, obviously, I really did feel normal.

Unbothered by changes

A handful of participants mentioned they were unconcerned by the hyposexual changes for reasons such as sexuality rehabilitation being low on their priority list, seeing these changes as a temporary side effect of medications, or simply being unbothered by a loss in sexual desire, which was the case for P16 (Hyposexuality): “it’s affected me but it doesn’t bother me, but I’m sure there’s people that are in my position and it does bother them.”

Sense of loss

Other participants with hyposexuality described a general sense of loss in function, self-identity, self-worth, confidence and quality of life in general.

[Sex is] something that me as a person enjoyed and you always think it’s like when you lose a leg and you can’t walk on it … when you start adding up the list of what I’ve lost from the accident, it gets to be quite long. (P5, Hyposexuality)

Clinicians helping with navigating post-TBI sexuality

Regardless of premorbid attributes and the nature of their post-TBI sexuality, individuals felt that clinicians may be able to help them navigate this area of their lives through psychoeducation. Individuals shared possible benefits and barriers to psychoeducation, alongside their shared and varied preferences in receiving support.

Benefits to psychoeducation

Prevention

One possible benefit was that psychoeducation may serve as a preventative intervention to sexuality changes and resultant impacts on relationships: “if this was addressed sooner, maybe things might be different in our relationship. Do you know what I mean? I don’t know. But who knows?” (P16, Hyposexuality).

Enhancing knowledge and skills

Basic psychoeducation could help with raising sexuality literacy levels on the general topic of sexuality, their awareness of prevalent post-TBI sexuality issues and reflecting on changes within themselves: “somebody can actually answer when [a health professional asks], ‘How is sexuality feeling? How are your desires?’” (P18, Hyposexuality). Some individuals also reflected that having conversations about these changes could empower them to seek help.

It’s not something that I sort of gave much thought to, but now having spoken to [interviewer] and realising it is something that everyone that’s had a brain injury probably should be aware of, but also know that there’s options if there are options. (P16, Hyposexuality)

Normalisation

Some individuals indicated that basic psychoeducation from clinicians could normalise and validate the changes they faced “Basically it’s not unusual. Other people have experienced it, so people don’t feel so bad for experiencing it” (P11, Hypersexuality).

Barriers to psychoeducation

Not ready or disinterested

Some individuals highlighted that they may not have been ready for a conversation early on in their recovery: “At the time, for me, it wasn't a priority. And if someone had brought it up to me at the time, I probably would have dismissed it … It would be good to have that conversation later on down the track.” (P19, Hyposexuality). Some individuals also indicated that they were disinterested in seeking help or receiving information about the topic: “It doesn’t really bother me, to be honest. I’ve got a pretty busy life, a schedule with work and all that so I don’t really think of it much.” (P7, Hyposexuality).

Discomfort

Most individuals spoke of the discomfort associated with speaking about this topic openly, either because of their discomfort or perceived discomfort from their treating clinicians: “I don’t think [my GP] really likes talking about it to tell you the truth.” (P1, Hyposexuality).

Difficulty communicating sexuality experiences

Aside from discomfort, almost all individuals also found it challenging to communicate their post-TBI sexuality experiences largely due to low sexual literacy levels in the general topic of sexuality and therefore in reflecting on their sexuality and changes, and limited experiences in exploring this area of their lives: “Honestly, I was a little bit nervous [doing this interview]. I was like, ‘Oh, no, you're asking me about something that I don't even know about,’ but it's been fine.” (P15, Hyposexuality).

Varied preferences for sexuality support

When it came to preferences around receiving information and support on sexuality after TBI, there was significant variability seen across individuals.

Comfort

There were mixed feelings about how comfortable individuals would be with clinicians initiating the topic of sexuality with them. While many individuals indicated that they would be unbothered by it, “Yeah, I'm not fazed with it” (P13, No changes), a few expressed clear levels of discomfort: “Yeah, it’s just uncomfortable” (P4, Hypersexuality).

Timing

There were again mixed opinions amongst individuals upon reflecting on when the best time for clinicians would be to initiate the discussion. Some felt that individuals should be warned about the possible impacts of TBI on sexuality before leaving the hospital: “any time before discharge so they understand. They’re getting out of hospital, so they need to understand what happens in the real world” (P12, Hyposexuality). However, as mentioned under barriers to psychoeducation, others felt they would not have been ready to have had the conversation so early on in their recovery. Importantly, most spoke about the idea of planting the seed early, giving time for individuals to absorb the information, and providing a clear opportunity to revisit the topic at a later time if need be: “I think verbally brought up so then you’re given the chance to think about it for a day or so because it’s not something that you’re gonna know all the questions for straight away.” (P5, Hyposexuality).

Who to initiate

Individuals were asked if they would prefer for the topic to be initiated by themselves or by their clinicians. Some suggested that it may be easier for individuals to bring the topic up themselves, but many indicated that individuals are likely too embarrassed to do so and that clinicians are better placed and trained to initiate the conversation: “ideally if someone would bring it up, I think that would be better because sometimes you're too embarrassed to ask about it.” (P15, Hyposexuality).

Shared preferences for sexuality support

Despite the significant variability in preferences, individuals provided a few aspects that would be helpful for clinicians to consider when providing psychoeducation on sexuality.

Seek permission

All of the individuals felt it was imperative that clinicians seek permission before delving further into the topic: “ask them if they want to talk about it first, I would say. So, approach the situation carefully.” (P15, Hyposexuality).

Clinician with best rapport

Many individuals suggested that the conversation should be initiated by the clinician within their treating team with whom they have the best rapport: “it doesn’t matter actually if it isn’t your profession or what your knowledge about it, it’s how much you care.” (P20, No changes).

Sensitivity and privacy

All individuals felt that it was paramount for clinicians to approach the topic with sensitivity and to protect their privacy when conducting discussions on sexuality: “instead in front of everyone, you want it more secluded. That way it might give the patient a bit more willingness to open up about it” (P14, Hyposexuality).

Multimodal approach

Due to the significant heterogeneity in cognitive and sensory impairments following TBI and varied preferences in receiving information, a multimodal approach to sharing information with individuals (e.g., verbally, short- and long-form printed, online, audio-visual options) was recommended to ensure that resources or information were accessible to all.

… a video, but one that you know, with a real person talking, not a um … not a screen that’s got writing on it. A little tiny bit of writing would have been ok, but you know, I really couldn’t handle it. (P2, Hyposexuality)

Having management options

In terms of the type of information that individuals would like to see on psychoeducation materials, options for treatment and management of sexuality after TBI was a shared preference for most individuals.

… advice that if this happens, give these people a call, or that kind of thing, or ‘let us know and we’ll work through it together, or something like that, just to know that it could very well be an effect of your injury, but it’s something we can maybe work on, if you can. I don’t know if it’s even a possibility that it can be – I know there’s coping strategies for other things. So I don’t know if there’s coping strategies for that. (P16, Hyposexuality)

Discussion

Changes in sexuality are commonly observed after TBI, but little has been done to explore the lived experiences of individuals with TBI in this topic. In the existing literature, O'Reilly et al. (Citation2023) qualitatively explored women’s reproductive health issues following TBI, while Gill et al. (Citation2011) and O'Keeffe et al. (Citation2020) explored the impact of TBI on intimate relationships. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first qualitative study that has purposively sampled a wider range of sexual functioning and wellbeing experiences across partnered and unpartnered individuals who identify as females and males.

This study explored individuals’ views regarding sexuality, their post-TBI sexuality experiences, and preferences for receiving information and support from health professionals. Three major themes were identified through reflexive thematic analysis. First, individuals differed significantly at the start of their journeys in terms of personal attributes, TBI-associated impacts, as well as comfort levels in discussing sexuality. Second, their journeys, feelings, and perspectives, diverged further based on the nature of their post-TBI sexuality. Third, whilst journeys were highly heterogeneous, individuals felt that clinicians were well placed to help navigate this area of their lives and shared their preferences around receiving support for post-TBI sexuality.

Everyone is different

While previous survey studies have hinted at the varied attitudes and needs pertaining to discussing sexual topics after a TBI (Moreno et al., Citation2015; Sander et al., Citation2012), the in-depth exploratory analysis in this study underscores the substantial diversity among individuals in their pre-injury attitudes, post-injury needs, and responses to sexuality changes. These factors include the perceived importance of sexuality, levels of sexuality literacy, comfort levels, and impacts from their injury. Importantly, these factors have been shown to influence help-seeking behaviours for sexual issues across different populations such as multiple sclerosis patients, individuals with disabilities and older adults (Kedde et al., Citation2012; Schaller et al., Citation2020; Tudor et al., Citation2018). Consequently, this heterogeneity may account for the equally diverse views noted in their reactions to sexuality changes, and preferences regarding support and service delivery.

Sexuality is complex

While sexuality is intrinsic to most, it is nevertheless a complex and multi-faceted concept that is constantly evolving based on prevailing social standards. It was observed that many participants had difficulty defining sexuality and reflecting on changes. Several participants who first reported unchanged sexuality at the start of the interviews were revealed to have experienced hyposexual changes upon deeper discourse. Many of the participants were also found to have experienced different experiences with post-TBI sexuality than previously reported on the BIQS (e.g., hyposexuality on interview vs unchanged based on BIQS scores).

Experiences in sexuality, such as desire, can fluctuate in the general population based on mood and relationship states (Harris et al., Citation2023). Normal fluctuations could have also been exacerbated by TBI-related factors, making it even trickier for participants to reflect on. For instance, reduced sexual outcomes have been associated with older age, reduced cognitive functioning, anxiety and pain, with depression acting as a mediator of elevated fatigue and decreased social participation impacting sexuality (Fraser et al., Citation2020; Ponsford et al., Citation2013; Sander et al., Citation2012). While increased time post-injury has been associated with improved outcomes in one study (Ponsford et al., Citation2013), other studies have not found significant associations (Fraser et al., Citation2020; Kreuter et al., Citation1998; O'Carroll et al., Citation1991; Sandel et al., Citation1996). Research investigating the associations between injury severity and post-TBI sexual dysfunction has been notably inconsistent (Fraser et al., Citation2020; Sander et al., Citation2013; Strizzi et al., Citation2017; Strizzi et al., Citation2015).

Sexuality is rarely addressed and help-seeking behaviours are limited

Despite the high incidence of experiencing changes in sexuality, only a few individuals reported engaging in discussions with their health providers on this topic. Moreover, those who did have such conversations reported that they were insufficient in addressing information regarding possible sexual concerns and help-seeking options or were marred by perceived discomfort from the health provider. The explored barriers to discussing sexuality topics with their healthcare team included being unprepared for such conversations especially early on during the recovery journey, disinterest in addressing sexuality with their health professionals, discomfort with discussing intimate topics, and low levels of sexual literacy levels leading to difficulties communicating experiences related to sexuality.

Of greater consequence, individuals who expressed a need for help with navigating these changes were unaware of how to do so and were uncomfortable with initiating the help-seeking process. The low incidence of patients reporting issues in clinical settings may potentially be contributing to the inadvertent neglect of assessment and treatment of hyposexual issues in TBI healthcare and chronicity of post-TBI sexuality issues (Fraser et al., Citation2021; Hwang et al., Citation2021; Ponsford et al., Citation2013). Prior research has also highlighted the negative repercussions that post-TBI sexuality changes have on the quality of life and sexuality outcomes of intimate partners (Downing & Ponsford, Citation2018; O'Keeffe et al., Citation2020). This may be seen as a secondary outcome of limited help-seeking behaviours, potentially perpetuating poorer reciprocal and dyadic sexuality outcomes after injury for partnered individuals (Pascoal et al., Citation2014). Individuals’ reluctance to seek professional assistance likely stems from low levels of sexual literacy, and the prevailing stigma across wider healthcare in speaking about difficulties with sexual wellbeing, or issues that fall outside physiological or reproductive domains, which are arguably the more substantial components of sexuality and subjective satisfaction with sexuality (Anderson, Citation2013; Barrett et al., Citation2022; Fraser et al., Citation2022; Stead et al., Citation2003).

The stigma surrounding seeking information on sexuality and discussing it openly can also make it challenging for individuals to reflect on their sexuality experiences consistently and confidently. Health providers often feel responsible for addressing sexuality but point to the lack of knowledge, training, time constraints, and organisational support, and stigma-related discomfort as significant barriers (Arango-Lasprilla et al., Citation2017; Dyer & Das Nair, Citation2014; Hwang et al., Citation2021). Thus, addressing sexuality is likely to remain a peripheral concern for most clinicians until the social stigma around this topic is dismantled at a structural level and integrated into professional training.

A tailored and careful approach is required

Currently, there is no gold standard approach to addressing sexuality. However, in considering the diverse needs and situations of individuals with TBI, health professionals can use the insights provided by participants in this study as a starting point for improving their approach to addressing sexuality concerns. These include having the healthcare team member that has the best rapport with the individual address the topic, seeking permission to broach the topic, providing multimodal options for take-home information that cater to their post-TBI cognitive and perception deficits (e.g., verbally, short- and long-form printed, online, audio-visual options), and providing education and information on available treatment options.

With health literacy as a midstream social determinant of health outcomes, improving literacy levels pertaining to sexual health and wellbeing, specifically in post-TBI sexuality, could potentially improve help-seeking behaviours for individuals with TBI (Nutbeam & Lloyd, Citation2021). Health professionals could assist with these challenges and destigmatise sexuality-related discussions by employing the Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, Intensive Therapy (PLISSIT) model, a four-step sexual counselling model that has been well-received across multiple clinical populations (Annon, Citation1976; Chun, Citation2011; Khakbazan et al., Citation2016). For instance, health professionals can help to create a permissive and safe environment for patients to raise concerns in utilizing the first step of the model. This could involve using simple language that is tailored to an individual’s level of understanding, and open-ended questioning on sexuality to encourage discourse. Notably, the reported lack of clinical assessment and treatment tool utilisation for post-TBI sexuality is a huge impediment to health professionals’ confidence in tackling this highly sensitive topic (Dyer & Das Nair, Citation2014; Hwang et al., Citation2021).

Limitations

One limitation is the absence of cognitive screening, mood measures, preinjury sexuality assessments, and TBI pathology data. The wide range in participant age and the known impact of older age on diminished sexual outcomes may have compounded sexuality issues, alongside other cognitive changes, and psychosocial factors such as anxiety and depression. Moreover, hypersexuality and inappropriate sexual behaviours may be attributed to reduced inhibition, insight, and increased impulsivity following moderate-to-severe TBI and frontal lobe damage (Sandel et al., Citation1996).

Despite efforts to cover a range of post-TBI sexuality experiences, there was uneven representation across groups, with hyposexual changes being most frequently reported by participants. Notably, this aligns with existing research suggesting approximately half of individuals with moderate-to-severe TBI experience hyposexual changes (Downing et al., Citation2013; Fraser et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the in-depth approach to exploring post-TBI sexual experiences may have heightened awareness and recognition of otherwise unnoticed sexuality issues, leading to higher rates of identified hyposexual symptoms. Future studies could aim to represent each group individually to gain a deeper understanding of their unique experiences.

Notably, research interviews are traditionally conducted in-person and critiques of tele-mediated communication argue that social context cues may be missed (Opdenakker, Citation2006). However, a tele-approach was considered appropriate given that individuals were more likely to feel comfortable discussing a highly sensitive topic in their home environment (Thunberg & Arnell, Citation2022). Furthermore, we were able to interview rural individuals who may not have been able to travel for an in-person interview. The loss of visual and social cues was also mediated by using semantic coding for data analysis.

Conclusion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first study to qualitatively explore partnered and unpartnered individuals’ lived experiences of both sexual functioning and wellbeing outcomes after TBI, along with their needs and preferences in sexuality support and service delivery. Given that sexuality changes are common after TBI and are a clinically significant aspect of health and wellbeing, further research is required to understand these changes better within the TBI population and to develop viable assessment and treatment options to assist health professionals in addressing sexuality with greater confidence. Establishing tailored discussions around post-TBI sexuality as a standard practice in clinical settings is imperative if we seek to adequately support individuals in this highly neglected issue.

Ethical standards

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Monash University, Project ID No. 29935 (16 July 2021).

Appendix updated.docx

Download MS Word (32 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, R. (2013). Positive sexuality and its impact on overall well-being. Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz, 56(2), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-012-1607-z

- Annon, J. S. (1976). The PLISSIT model: A proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 2(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01614576.1976.11074483

- Arango-Lasprilla, J. C., Olabarrieta-Landa, L., Ertl, M. M., Stevens, L. F., Morlett-Paredes, A., Andelic, N., & Zasler, N. (2017). Provider perceptions of the assessment and rehabilitation of sexual functioning after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 31(12), 1605–1611. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2017.1332784

- Barrett, O. E. C., Ho, A. K., & Finlay, K. A. (2022). Supporting sexual functioning and satisfaction during rehabilitation after spinal cord injury: Barriers and facilitators identified by healthcare professionals. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 54(10), jrm00298. https://doi.org/10.2340/jrm.v54.1413

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. London Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE

- Chun, N. (2011). Effectiveness of PLISSIT model sexual program on female sexual function for women with gynecologic cancer. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing, 41(4), 471–480. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2011.41.4.471

- Downing, M., & Ponsford, J. (2018). Sexuality in individuals with traumatic brain injury and their partners. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 28(6), 1028–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2016.1236732

- Downing, M. G., Stolwyk, R., & Ponsford, J. L. (2013). Sexual changes in individuals with traumatic brain injury: A control comparison. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 28(3), 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e31828b4f63

- Dyer, K., & Das Nair, R. (2014). Talking about sex after traumatic brain injury: Perceptions and experiences of multidisciplinary rehabilitation professionals. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(17), 1431–1438. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.859747

- Fraser, E. E., Downing, M. G., Haines, K., Bennett, L., Olver, J., & Ponsford, J. L. (2022). Evaluating a novel treatment adapting a cognitive behaviour therapy approach for sexuality problems after traumatic brain injury: A single case design with nonconcurrent multiple baselines. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 11(12), 3525. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm11123525

- Fraser, E. E., Downing, M. G., & Ponsford, J. L. (2020). Understanding the multidimensional nature of sexuality after traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 101(12), 2080–2086. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2020.06.028

- Fraser, E. E., Downing, M. G., & Ponsford, J. L. (2021). Survey on the experiences, attitudes, and training needs of Australian healthcare professionals related to sexuality and service delivery in individuals with acquired brain injury. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2021.1934486

- Gan, C. (2005). Sexuality after ABI [Conference presentation]. Third Annual TBI conference: Expression of sexuality and behaviours following TBI, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

- Gill, C. J., Sander, A. M., Robins, N., Mazzei, D. K., & Struchen, M. A. (2011). Exploring experiences of intimacy from the viewpoint of individuals with traumatic brain injury and their partners. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 26(1), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182048ee9

- Harris, E. A., Hornsey, M. J., Hofmann, W., Jern, P., Murphy, S. C., Hedenborg, F., & Barlow, F. K. (2023). Does sexual desire fluctuate more among women than men? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 52(4), 1461–1478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02525-y

- Hibbard, M. R., Gordon, W. A., Flanagan, S., Haddad, L., & Labinsky, E. (2000). Sexual dysfunction after traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation, 15(2), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-2000-15204

- Hwang, J. H. A., Fraser, E. E., Downing, M. G., & Ponsford, J. L. (2021). A qualitative study on the attitudes and approaches of Australian clinicians in addressing sexuality after acquired brain injury. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.2012605

- Johnson, V. E., Stewart, W., & Smith, D. H. (2013). Axonal pathology in traumatic brain injury. Experimental Neurology, 246, 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.01.013

- Kedde, H., van de Wiel, H., Schultz, W. W., Vanwesenbeeck, I., & Bender, J. (2012). Sexual health problems and associated help-seeking behavior of people with physical disabilities and chronic diseases. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 38(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.569638

- Khakbazan, Z., Daneshfar, F., Behboodi-Moghadam, Z., Nabavi, S. M., Ghasemzadeh, S., & Mehran, A. (2016). The effectiveness of the Permission, Limited Information, Specific suggestions, Intensive Therapy (PLISSIT) model based sexual counseling on the sexual function of women with Multiple Sclerosis who are sexually active. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 8, 113–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2016.05.007

- Kreuter, M., Dahllöf, A. G., Gudjonsson, G., Sullivan, M., & Siösteen, A. (1998). Sexual adjustment and its predictors after traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 12(5), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/026990598122494

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2015). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Marier-Deschênes, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Déry, J., & Lamontagne, M.-E. (2020). Traumatic brain injury and sexuality: User experience study of an information toolkit. Journal of Participatory Medicine, 12(1), e14874–e14874. https://doi.org/10.2196/14874

- Moreno, J. A., Arango Lasprilla, J. C., Gan, C., & McKerral, M. (2013). Sexuality after traumatic brain injury: A critical review. NeuroRehabilitation, 32(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-130824

- Moreno, A., Gan, C., Zasler, N., & McKerral, M. (2015). Experiences, attitudes, and needs related to sexuality and service delivery in individuals with traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation, 37(1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.3233/NRE-151243

- Nutbeam, D., & Lloyd, J. E. (2021). Understanding and responding to health literacy as a social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health, 42(1), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102529

- O'Carroll, R., Woodrow, J., & Maroun, F. (1991). Psychosexual and psychosocial sequelae of closed head injury. Brain Injury, 5(3), 303–313. https://doi.org/10.3109/02699059109008100

- O'Keeffe, F., Dunne, J., Nolan, M., Cogley, C., & Davenport, J. (2020). “The things that people can’t see” The impact of TBI on relationships: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Brain Injury, 34(4), 496–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699052.2020.1725641

- Opdenakker, R. (2006). Advantages and disadvantages of four interview techniques in qualitative research. Forum, Qualitative Social Research, 7(4), 11. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-7.4.175

- O'Reilly, K., Wilson, N. J., Kwok, C., & Peters, K. (2023). An exploration of women's sexual and reproductive health following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(5-6), 901–911. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16510

- Pascoal, P. M., Narciso, I. d. S. B., & Pereira, N. M. (2014). What is sexual satisfaction? Thematic analysis of lay people's definitions. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(1), 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.815149

- Ponsford, J. L., Downing, M. G., Olver, J., Ponsford, M., Acher, R., Carty, M., & Spitz, G. (2014). Longitudinal follow-up of patients with traumatic brain injury: Outcome at two, five, and ten years post-injury. Journal of Neurotrauma, 31(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1089/neu.2013.2997

- Ponsford, J. L., Downing, M. G., & Stolwyk, R. (2013). Factors associated with sexuality following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 28(3), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e31828b4f7b

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2022). Nvivo. (Version 1.7). [Computer software]. QSR International Pty Ltd.

- Sandel, M., Williams, K., Dellapietra, L., & Derogatis, L. (1996). Sexual functioning following traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 10(10), 719–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/026990596123981

- Sander, A. M., Maestas, K. L., Nick, T. G., Pappadis, M. R., Hammond, F. M., Hanks, R. A., & Ripley, D. L. (2013). Predictors of sexual functioning and satisfaction 1 year following traumatic brain injury: A TBI model systems multicenter study. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 28(3), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e31828b4f91

- Sander, A. M., Maestas, K. L., Pappadis, M. R., Sherer, M., Hammond, F. M., & Hanks, R. (2012). Sexual functioning 1 year after traumatic brain injury: Findings from a prospective traumatic brain injury model systems collaborative study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93(8), 1331–1337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2012.03.037

- Schaller, S., Traeen, B., & Lundin Kvalem, I. (2020). Barriers and facilitating factors in help-seeking: A qualitative study on how older adults experience talking about sexual issues with healthcare personnel. International Journal of Sexual Health, 32(2), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2020.1745348

- Simpson, G., & Baguley, I. (2012). Prevalence, correlates, mechanisms, and treatment of sexual health problems after traumatic brain injury: A scoping review. Critical Reviews in Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 24(1-2), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1615/CritRevPhysRehabilMed.v24.i1-2.10

- Stead, M. L., Brown, J. M., Fallowfield, L., & Selby, P. (2003). Lack of communication between healthcare professionals and women with ovarian cancer about sexual issues. British Journal of Cancer, 88(5), 666–671. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600799

- Stocchetti, N., & Zanier, E. R. (2016). Chronic impact of traumatic brain injury on outcome and quality of life: A narrative review. Critical Care, 20(1), 148–148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-016-1318-1

- Stolwyk, R. J., Downing, M. G., Taffe, J., Kreutzer, J. S., Zasler, N. D., & Ponsford, J. L. (2013). Assessment of sexuality following traumatic brain injury: Validation of the Brain Injury Questionnaire of Sexuality. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 28(3), 164–170. https://doi.org/10.1097/HTR.0b013e31828197d1

- Strizzi, J., Olabarrieta-Landa, L., Olivera, S. L., Valdivia Tangarife, R., Andrés Soto Rodríguez, I., Fernández Agis, I., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2017). Sexual function in Men with traumatic brain injury. Sexuality and Disability, 35(4), 461–470. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11195-017-9493-9

- Strizzi, J., Olabarrieta Landa, L., Pappadis, M., Olivera, S. L., Valdivia Tangarife, E. R., Fernandez Agis, I., Perrin, P. B., & Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2015). Sexual functioning, desire, and satisfaction in women with TBI and healthy controls. Behavioural Neurology, 2015, 247479. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/247479

- Thunberg, S., & Arnell, L. (2022). Pioneering the use of technologies in qualitative research – A research review of the use of digital interviews. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25(6), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1935565

- Tudor, K. I., Eames, S., Haslam, C., Chataway, J., Liechti, M. D., & Panicker, J. N. (2018). Identifying barriers to help-seeking for sexual dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology, 265(12), 2789–2802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-018-9064-8

- van den Broek, B., Rijnen, S., Stiekema, A., van Heugten, C., & Bus, B. (2022). Factors related to the quality and stability of partner relationships after traumatic brain injury: A systematic literature review. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 103(11), 2219–2231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2022.02.021

- Varpio, L., Ajjawi, R., Monrouxe, L. V., O'Brien, B. C., & Rees, C. E. (2017). Shedding the cobra effect: Problematising thematic emergence, triangulation, saturation and member checking. Medical Education, 51(1), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13124

- Verschuren, J. E., Enzlin, P., Dijkstra, P. U., Geertzen, J. H., & Dekker, R. (2010). Chronic disease and sexuality: A generic conceptual framework. Journal of Sex Research, 47(2-3), 153–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224491003658227

- World Health Organization. (2006). Defining sexual health: report of a technical consultation on sexual health. https://www.who.int/teams/sexual-and-reproductive-health-and-research/key-areas-of-work/sexual-health/defining-sexual-health