ABSTRACT

To review the applicability and accessibility of physical activity guidelines for adults living with long-term conditions whilst shielding during the COVID-19. A narrative review with systematic methodology was conducted between 2015 and 2021, with two stages: 1) Search of electronic databases PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, PsycInfo, and Cinahl; 2) search of long-term condition organisations. Sixty-five articles were identified, where nine included specific guidelines during the COVID-19, 28 specific guidelines to individuals living with long-term conditions and 7 identified the utilization of online resources. Twenty-one long-term condition organizations websites were reviewed where all of them included a section regarding physical activity guidelines and seven referred to online and offline accessible resources during COVID-19. Accessibility and applicability were variable across academic databases and long-term conditions organisation websites. Findings could inform long-term condition policy and guidelines development to better and more relevant support people living with long-term conditions to be physically active.

Introduction

Globally, having one or more long-term conditions (LTCs) is associated with 41 million deaths each year, which is equivalent to 71% of all deaths worldwide (World Health Organization Citation2020). In England, LTCs affect ~15.4 million people and this figure is expected to rise to 18 million by 2025 (Stafford et al. Citation2018; Rolewicz et al. Citation2020). Regular physical activity (PA) participation has been proven to help prevent and manage various LTCs, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and several cancers (World Health Organisation. Physical Activity Citation2021a), and has shown to be beneficial in improving mental health and/or people wellbeing (Sallis et al. Citation2020; Woods et al. Citation2020). PA and exercise participation may be prescribed, adjusted, and scaled to the needs and abilities of each individual across the lifespan (Siedler et al. Citation2021). The most recent UK Chief Medical Officers’ Physical Activity Guidelines sets out the recommendations for adults (aged 19–64 years) and older adults (aged 65+ years), including those with LTCs (UK Chief Medical Officers’ PA guidelines. Citation2019).

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by severe coronavirus 2 acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2), and since March 2020 has severely impacted the daily lives of UK residents. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the UK’s Prime Minister and Secretary for Culture, Media and Sport released regular guidance on how to limit the spread of COVID-19, which included measures such as social distancing, self-isolation and/or shielding, with and without periods of ‘lockdown’ for the general population, including those living with LTCs. However, during times when restrictions were eased, some individuals, particularly those with LTCs, remained adhering to shielding guidelines as a precautionary measure. These strategies, aimed at reducing the spread of COVID-19, have been shown to exacerbate poor lifestyle behaviours, namely resulting in a reduction in PA, impaired physical and psychological health, and higher mortality (UK Chief Medical Officers’ PA guidelines. Citation2019; Siedler et al. Citation2021). For example, with 48,440 adults who had a positive COVID-19 test or diagnosis, physical inactivity was associated with a higher risk for hospitalisations, admission to intensive care units and patient death (Sallis et al. Citation2021). Furthermore, physical and social distancing during COVID-19 has been linked with a decrease (≤32%) in PA (Meyer et al. Citation2020; Faulkner et al. Citation2021) and this has resulted in poorer mental health compared to individuals who maintained or increased their PA (Faulkner et al. Citation2021, Citation2022). Mental health is an important parameter to monitor during the Covid-19 pandemic as it provides an indication of how people can cope with normal stresses of life (World Health Organization Citation2021c). Furthermore, recent research undertaken during a period of COVID-19 ‘lockdown’, where individuals were advised to stay and/or shield at home (except for very specific reasons), showed that 17.3% of individuals with a self-reported LTC indicated a negative change in their overall exercise behaviour (Faulkner et al. Citation2021). There is also evidence that adults with LTCs engaged in less intensive PA during COVID-19 restrictions than before (Rogers et al. Citation2020). Indeed, such negative changes in PA and exercise behaviour may promote the development and/or worsening of many LTCs, which may also contribute to potentially poorer outcomes in those who contract COVID-19 (Word Health Organization, Citation2021a). What is unclear in the literature, however, are reasons for this decrease in volume and intensity of PA with individuals living with LTCs.

Despite the UK government issuing advice for individuals living with LTCs to ‘stay at home’, no official guidance was provided on how these individuals could remain or improve their PA participation whilst doing so. It is important, therefore, to determine whether people living with LTCs had access to appropriate guidance and resources that could facilitate their engagement in PA throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly whilst shielding at home. A lack in availability of appropriate resources would indicate areas for development to ensure maximum benefit, and optimal health, to individuals living with LTCs throughout future periods of movement restriction due to COVID-19 or other future pandemics. Consequently, the aim of this study was to review the applicability and accessibility of PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources for adults living with LTCs whilst shielding during the COVID-19 pandemic. The following two review questions were proposed: i) what online/offline PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources were accessible to adults living with LTCs during the COVID-19 pandemic? ii) how applicable were available guidelines, recommendations and/or resources for adults living with LTCs, and who may have been shielding at home, during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methods

In accordance with Jahan et al. (Citation2016), a narrative review with systematic methodology was conducted.

Search strategy

The search strategy encompassed two main stages:

Stage 1. Search of literature databases

The following electronic databases were systematically searched from January to September 2021: PubMed/Medline, Web of Science, PsycInfo and Cinahl. The included Mesh- and truncated terms are presented in . Study eligibility criteria included: English and Spanish language studies, adults over 18 years of age, publication date between 2015–2021. Studies were included if they: i) referred to online or offline PA or exercise guidelines, recommendations, or resources for adults, including adults living with at least one LTC, pregnant adults, older adults (World Health Organization Citation2020), and/or ii) presented guidelines that include PA or exercise recommendations for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiometabolic diseases (e.g. Coronary heart disease, Diabetes Mellitus, Stroke). Exclusion criteria were: i) online or offline PA or exercise guidelines, recommendations, or resources for children and adolescents, ii) evidence that did not include primary presentation of PA or exercise guidelines, recommendations and/or resources.

Stage 2. Search of LTCs Organisations’ online and offline resources

Initially, a review of information provided on the websites of LTCs Organisations was conducted (Stansfield et al. Citation2016) to identify any relevant guidelines, recommendations and/or resources to facilitate PA engagement for individuals with LTCs, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The review of information was conducted between January to June (30th) 2021. The Quality and Outcomes Framework (2019) was used to identify the most prevalent LTCs within the UK, which then guided the review into the various organisational websites associated with these conditions. Freely available (published online) PA and exercise guidelines, recommendations and/or resources provided on organisations’ websites were reviewed by the authors for applicability for adults living with LTCs during the period of COVID-19 restrictions. LTC organisations, namely charities, professional organisations, and societies, and national or international government agencies, as well as non-profit health organisations, were contacted via email by LA to identify any unpublished offline PA or exercise guidelines, recommendations and/or resources offered by them (e.g. via newsletter, post, etc.) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data extraction

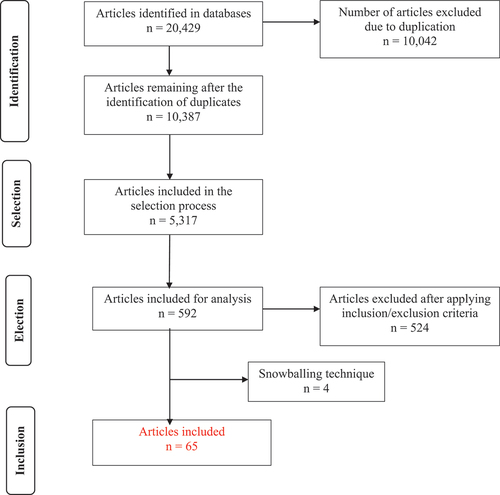

Data extraction during Stage 1 adhered to PRISMA guidelines (Moher et al. Citation2009), which included the screening of titles and abstracts from the relevant electronic databases. Articles that clearly did not meet the study inclusion criteria were rejected. All remaining full texts were read to determine their inclusion in the study (). This process was led by LA and validated by DL. The methodological quality of the articles was not evaluated as the purpose of the review was to identify the accessibility and applicability of PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources during COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2. Flow diagram of the article selection process.

For data extraction during Stage 2, authors LA and DL independently, systematically analysed the data on organisations’ websites (Stansfield et al. Citation2016) for accessibility and applicability of PA information for individuals living with LTCs during COVID-19. Consensus was reached in relation to each organisation following subsequent discussion.

Results

Stage 1. Search of literature databases

Of the 10,634 articles identified, 5,317 were screened for inclusion. Sixty-four articles referred to PA guidelines for adults, either in relation to the general population and which were deemed applicable for individuals living with LTCs, or with a specific focus on individuals living with LTCs and were therefore included within this review (see ). All of the articles identified included at least one type of PA and/or exercise guidelines, recommendations and/or resources, which were applicable for adults living with at least one LTC during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority (n = 57) of the 65 applicable articles were freely accessible to the general public, that is, these were not behind a paywall or accessible only via an institutional licensing agreement (see ).

Table 1. Main features of articles related to physical activity guidelines.

Of the 65 articles identified, 29 were reviews, 6 editorials, and 5 were original articles, while the remaining (n = 25) were official guidelines, discussion, or commentary articles. Thirty-six articles were relevant for the general population, which included pregnant women and/or individuals living with LTCs. In addition, 28 articles provided PA guidelines that were specific to individuals living with LTCs. For example, the European Society of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (Hindieh et al. Citation2017; Rausch Osthoff et al. Citation2018; Macías-Rodríguez et al. Citation2019; Kim et al. Citation2019; Rock et al. Citation2020; Sepulveda-Loyola et al. Citation2020) provided specific PA guidance for individuals living with cardiovascular diseases.

Nine out of 65 articles (Baisi-Chagas et al. Citation2020; Ranasinghe et al. Citation2020; Jurak et al. Citation2020; Roschel et al. Citation2020; Castañeda-Babarro et al. Citation2020; Baena Morales et al. Citation2020; World Health Organization Citation2021b; Polero et al. Citation2021) included PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources for adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically (see ). Of these, only two presented clear written text and visual images detailing how to stay active and reduce sedentary behaviour whilst at home in self-quarantine (Baisi-Chagas et al. Citation2020; World Health Organization Citation2021b).

Eight articles (Sepulveda-Loyola et al. Citation2020; Baisi-Chagas et al. Citation2020; Castañeda-Babarro et al. Citation2020; Baena Morales et al. Citation2020; Srivastav et al. Citation2021; Ranasinghe et al. Citation2020; World Health Organization Citation2021b) identified the utilization of online PA and/or exercise resources, such as YouTube. With regard to online exercise platforms, YouTube and Zoom were identified as suitable technology from which to conduct both recorded and live sessions (Castañeda-Babarro et al. Citation2020). As for online applications, mobile-based or tablet-based apps (‘Workout trainer’, ‘Fitocracy’, ‘Runstatic Pro’ or ‘Strava’) and virtual reality-based media (‘Wii Balance board with WiiFit’, ‘Nintendo Wii Training’ or ‘Dance video game with pad’) were recommended to facilitate PA at home during the COVID-19 pandemic (Srivastav et al. Citation2021). The utilization of online PA and/or exercise applications was considered viable, safe, and effective to be physically active at home during COVID-19 restrictions for general population and for those living with LTCs, such as cardiovascular diseases or neurological conditions (e.g. Parkinson’s disease) (Baisi-Chagas et al. Citation2020; Srivastav et al. Citation2021).

Stage 2. Search of LTCs organisations’ online and offline resources

presents the written resources, videos, and podcasts associated with PA and COVID-19 specific guidance provided by 21 LTC organisations. All of the 21 LTC organisations reviewed included a PA and exercise section on their websites, including exercise guidelines, recommendations and/or resources and other relevant exercise and disease-specific information. Seven of the 21 LTC organisations indicated that their online resources were also accessible offline, while all other LTC organisations (n = 16) did not have any accessible offline PA resources during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2. Main themes from LTCs organizations.

Written resources and information: Eighteen of the 21 LTC organisation websites provided written information about the general benefits of PA for health and/or in relation to their specific condition of concern. Only three organisations (MIND, Macmillan and Kidney Research UK) provided comprehensive information that was clear and easy to navigate and included ideas for physical activities that are applicable for individuals living with specific LTCs, as well as providing information on the positive relationship between increased PA and mental health.

There were nine organisations that presented PA guidance that was relevant and applicable to people living with LTCs during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically. Some organisations acknowledged the change in circumstances (e.g. shielding/being at home more than ‘normal’) and presented ideas and information on how to be physically active around the home and garden, and some provided a printable, weekly exercise plan that people could follow or use as a guide (see ). However, at least one organisation website contained outdated information that was applicable only to the first ‘lockdown’, making the information less applicable to later stages of the pandemic.

Several organisations (n = 10) signposted users to various external sources of information relating to PA guideline guidelines, recommendations and/or resources. Often, NHS websites were recommended, including NHS choices, NHS Fitness Studio, and NHS Better Health, as well as National projects, such as the ‘Undefeatable’ campaign and ‘Move More’ project (Bangor University), or the promotion of current ‘influencers’ (e.g. Joe Wicks and Oti Mabusi) offering PA-based engagement with the general population, including those with LTCs. However, it was noted that some of these sources of information (e.g. information linked with the influencers) had become outdated by the later stages of the pandemic.

Visual resources: A small number of organisations (n = 5) provided patient-led videos which focussed on differing aspects of fitness (e.g. aerobic, strength, and endurance) or a range of activities (e.g. yoga, Pilates, and fatigue management) which people living with LTCs could watch and follow at home. As access to gym equipment could be difficult for some users, some organisations provided practical examples of what items around the home could be used instead of resistance weights, such as tin cans or filled water bottles (e.g. MacMillan Cancer Support). Only one organisation provided dedicated safety advice for people participating in unsupervised home-based exercise (MacMillan Cancer Support).

Booklets: In addition to written information included on organisation websites, some (n = 3) offered downloadable pdf booklets that provided example activities that could be completed both indoors and outdoors, exercise plans, and information on how to break up sitting time, adding health benefits over-and-above PA participation. One organisation indicated that the audio version of their booklet could also be requested via their website (MacMillan Cancer Support).

Podcasts: One organisation (MacMillan Cancer Support) provided podcasts by ‘experts’ to discuss the importance of PA in a generic sense after a diagnosis of their specific LTC and how this could be managed during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

Other resources: One organisation (National MS Society) provided other resources, including ‘live’ online sessions (Zoom exercise classes, webinars) that people could join in with, in real-time.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review to explore the accessibility and applicability of PA guidelines, recommendations, and/or resources available to adults living with LTCs whilst shielding during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our review has shown that the accessibility and applicability of information is variable across academic databases and LTC organisations. This may have important implications for individuals who use only those resources most closely linked to their specific condition/s.

Although PA information from scientific databases was largely accessible to people living with LTCs during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is unclear how useful this source of information actually is. It is suggested that scientific databases are not the best source of information for the general public as the use of databases of this nature requires specific scientific knowledge that members of the general public may not have (Stansfield et al. Citation2016). Furthermore, some potentially applicable information may be inaccessible to the general public due to being hidden behind a paywall. In the current study, seven articles containing potentially useful information on PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources were inaccessible to the general public for paywall reasons.

In total, 89% of all reviewed LTC organisations’ websites provided open and free-to-access online PA resources for the general public. All identified PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources were accessible online; none were easily or overtly accessible by way of an offline resource. Only 30% of the reviewed LTCs organizations offered the opportunity to make resources available offline, and only if specifically requested by an individual. Although online resources seem to be the most applicable way to provide PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources, particularly while physical distancing was required, access to- and cultural acceptability of internet-based technologies could be far from universal (Sallis et al. Citation2020). Many people, especially those with low incomes, may not have the financial resources to have access to computers and internet, or indoor space, or may have limitations with internet coverage that makes at-home PA unrealistic. Moreover, some people living with LTCs, as per the general population, may also be precluded from accessing online information due to low digital literacy (Pan et al. Citation2022). Hence, routinely offering offline methods of delivery of information may be a useful means to reach a broader population, both with and without LTCs. A practical solution may be to incorporate more conventional and accessible ways of delivering exercise and/or PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources, such as print guidelines or network television, although the cost implications of this may be a precluding factor.

In total, 43% of the organisation websites reviewed provided external links from their host site to other internet-based PA and/or exercise resources (e.g. influencer Joe Wicks or NHS Fitness Studio) (see ). In some cases, one could argue that this could be useful in facilitating access to a broader network of information, but practically this is reliant on higher levels of digital literacy and a stable internet connection, and it may also result in information being accessed that is less applicable to individuals with specific LTCs. Moreover, from the organizations’ perspective, they have less content control and a greater need to monitor external links, as if links become broken or content is changed then this could become difficult for people to navigate, resulting in a barrier for the person to find appropriate information relating to PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources.

Official websites of LTC organizations are typically considered a great source of information as they are accessible to the general public, including those living with LTCs, and [often] present useful and applicable information related to PA (Goodwin et al. Citation2010). Generic PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources are not suitable for everyone as differences in age, gender, physical abilities, PA preferences, and LTC severity may underpin different contraindications to exercise (Sallis et al. Citation2020). Therefore, five of the 21 organisations reviewed did not provide any guidelines, recommendations and/or resources; only provided general PA guidance not tailored to the LTC. Three organisations in particular provided comprehensive information that included useful resources and ideas on activities for individuals to participate in, in order to remain physically active. Moreover, some organisations included information pertaining to the positive relationship between PA and mental health (Sallis et al. Citation2020) albeit in a generic sense, but which is of particular relevance when considering the evidence of the deleterious effects of pandemic restrictions, such as shielding, on people’s PA, mental health, and wellbeing (Faulkner et al. Citation2021). Arguably, the most beneficial information was that which acknowledged the change in circumstances (e.g. shielding/being at home more than ‘normal’) and presented ideas and information on how to be physically active around the home and garden. Only nine of the 21 organisations reviewed provided advice or information relating to PA or exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic, specifically. This is a key aspect because information was adjusted and consequently, applicable to current circumstances regarding COVID-19 restrictions. In some cases, information provided had been tailored to acknowledge the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and provide appropriate resources to support engagement in PA, but at the time of review, that is, following the initial ‘lockdown’, this information had become outdated and was therefore no longer applicable for those seeking guidance.

For individuals with LTC, it is important that unsupervised home-based exercise programmes, whether online or offline, are designed: i) according to the disease characteristic/s in order to most effectively encourage participation and to ensure the safety of the individual, and ii) acknowledging potential personal circumstances that could be a barrier to engagement. In this study, five organisations provided video resources to demonstrate appropriate home-based activities and exercise technique; some accounted for differences in functional ability (e.g. providing both standing exercises and sitting exercises). One organisation provided advice on how to use items around the home to assist in their exercises, such advice is really useful for people who may otherwise be unable to source or afford to purchase exercise equipment, either during or outside of pandemic restrictions. Only one organisation included specific safety advice for exercising at home. During pandemic circumstances when individuals with LTCs are being encouraged to stay at home, more widespread information on how to remain physically active safely, whether this is in relation to specific exercise programmes or general PA, is warranted (Kaur et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, as PA and/or exercise programmes designed for the general population (e.g. Joe Wicks) may not be appropriate for clinical groups from a safety perspective, simple strategies, such as ‘move more and sit less’ or ‘breaking up sitting time’ could be promoted as safe and accessible options for those living with LTCs, to counter physical inactivity and encourage PA while at home during the COVID-19 pandemic (Pinto et al. Citation2020).

It is important that we contextualise our findings in light of the study’s strengths and limitations. Although most prevalent LTCs organisation websites were reviewed and contacted based on the Quality and Outcomes Framework (2019) it is possible that other LTCs organisations websites in the UK were not included. Also, despite identifying several LTCs organisations websites, we are unaware of how many people accessed and utilised these resources during the COVID-19 pandemic, and how this compared to the frequency of use of the same/similar resources pre-COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, data extraction was subjective, and it is plausible that some relevant information may have been inadvertently overlooked. To counter this possibility, data extraction was conducted systematically and independently by two researchers. A strength of the study was the identification of major LTC websites that correspond to the most prevalent LTCs in the UK. The relevance of this means that our findings have the greatest potential to be meaningful to a wide number of individuals. The findings may be useful for policy development and LTC organisations, in highlighting gaps and widespread differences in the guidance presented to individuals with specific LTCs, in order to promote PA engagement safely, effectively and consistently during COVID-19 restrictions, and/or future pandemics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the rationale for this study was based upon the observation that government guidance for individuals living with LTCs was typically to stay at home and shield during the COVID-19 pandemic, without providing any specific guidance on how to become or remain physically active. This study has shown that the accessibility and applicability of PA guidelines, recommendations and/or resources for people living with LTCs during the COVID-19 pandemic was variable across academic databases and LTC organisation websites. Although differing ways to present information have been used across differing LTC websites, it remains unclear which dissemination methods are most effective or well used by people living with LTCs who wish to become/remain physically active during periods of restriction (i.e. shielding) caused by a pandemic. This information would be beneficial for stakeholders at the micro-, meso- and macro-level to inform LTC policy development, to better support people living with LTCs to be physically active during future periods of mobility restriction and/or pandemics.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the library staff of University of Southampton.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baena Morales S, Tauler Riera P, Aguiló Pons A, Garcia Taibo O. 2020. Physical activity recommendations during the COVID-19 pandemic: a practical approach for different target groups. Nutr Hosp. 38(1):194–200.

- Baisi-Chagas E, Rodrigues P, Biteli P. 2020. Physical exercise and COVID-19: a summary of the recommendations. Bioengineering. 7(4):236–241. doi:10.3934/bioeng.2020020.

- Castañeda-Babarro A, Arbillaga-Etxarri A, Gutierrez-Santamaria B, Coca A. 2020. Physical activity change during COVID-19 confinement. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(6878):1–10. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186878.

- Faulkner J, O’-Brien WJ, McGrane B, Wadsworth D, Batten J, Askew CD, Badenhorst C, Byrd E, Coulter M, Draper N, et al. 2021. Physical activity, mental health, and well-being of adults during initial COVID-19 containment strategies: a multi-country cross-sectional analysis. J Sci Med Sport. 24(4):320–326. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2020.11.016

- Faulkner J, O’-Brien WJ, Stuart B, Stoner L, Batten J, Wadsworth D, Askew CD, Badenhorst CE, Byrd E, Draper N, et al. 2022. Physical activity, mental health and wellbeing of adults within and during the easing of COVID-19 restrictions, in the United Kingdom and New Zealand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 19(3):1792. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031792

- Goodwin N, Curry N, Naylor C, Ross S, Duldig W. 2010. Managing people with long-term conditions. The King’s Fund.

- Hindieh W, Adler A, Weissler-Snir A, Fourey D, Harris S, Rakowski H. 2017. Exercise in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a review of current evidence, national guideline recommendations and a proposal for a new direction to fitness. J Sci Med Sport. 20(4):333–338. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2016.09.007.

- Jahan N, Naveed S, Zeshan M, Tahir MA. 2016. How to conduct a systematic review: a narrative literature review. Cureus. 8(11):e864. doi:10.7759/cureus.864.

- Jurak G, Morrison SA, Leskosek B, Kovac M, Hadzic V, Vodicar J, Truden P, Starc G. 2020. Physical activity recommendations during the coronavirus disease-2019 virus outbreak. J Sport Health Sci. 9(4):325–327. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.05.003.

- Kaur H, Singh T, Arya YK, Mittal S. 2020. Physical fitness and exercise during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative enquiry. Front Psychol. 11:1–10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.590172.

- Kim Y, Lai B, Mehta T, Thirumalai M, Padalabalanarayanan S, Rimmer JH, Motl RW. 2019. Exercise training guidelines for multiple sclerosis, stroke, and Parkinson disease: rapid review and synthesis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 98(7):613–621. doi:10.1097/PHM.0000000000001174.

- Macías-Rodríguez RU, Ruiz-Margain A, Roman-Calleja BM, Moreno-Tavarez E, Weber-Sangui L, Gonzalez-Arellano MF, et al. 2019. Exercise prescription in patients with cirrhosis: recommendations for clinical practice. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 84(3):326–343.

- Meyer J, McDowell C, Lansing J, Brower C, Smith L, Tully M, Herring M. 2020. Changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviour due to the COVID-19 outbreak and associations with mental health in 3,052 US adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(18):6469. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186469.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. 2009. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Pan Q, Reichert F, de la Torre J, Law N. 2022. Measuring digital literacy during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences with remote assessment in Hong Kong. Educat Meas Issues Pract. 0(0):1–5.

- Pinto AJ, Dunstan DW, Bonfá E, Gualano B. 2020. Combating physical inactivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 16(7):347–348. doi:10.1038/s41584-020-0427-z.

- Polero P, Rebollo-Seco C, Adsuar JC, Pérez-Gómez J, Rojo-Ramos J, Manzano-Redondo F, Garcia-Gordillo MA, Carlos-Vivas J. 2021. Physical activity recommendations during COVID-19: narrative review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(65):1–24.

- Quality and Outcomes Framework. Prevalence LTCs (2019-2020). NHS digital. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMDZiMmI2MzEtMWVjZC00YTVlLWI5NjEtMTNkODM3M2M0NDk3IiwidCI6IjUwZjYwNzFmLWJiZmUtNDAxYS04ODAzLTY3Mzc0OGU2MjllMiIsImMiOjh9

- Ranasinghe C, Ozemek C, Arena R. 2020. Exercise and well-being during COVID-19 – time to boost your immunity. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 18(12):1195–1200. doi:10.1080/14787210.2020.1794818.

- Rausch Osthoff AK, Niedermann K, Braun J, Adams J, Brodin N, Dagfinrud H, Duruoz T, Appel Esbensen B, Gunther KP, Hurkmans E, et al. 2018. EULAR recommendations for physical activity in people with inflammatory arthritis and osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 77(9):1251–1260. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213585

- Rock CL, Thomson C, Gansler T, Gapstur SM, McCullough ML, Patel AV, Andrews KS, et al. 2020. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. Am Cancer Societ J. 70(4):245–271.

- Rogers NT, Waterlow N, Brindle H, Enria L, Eggo RM, Lees S, Roberts CH. 2020. Behavioural change towards reduced intensity physical activity is disproportionately prevalent among adults with serious health issues or self-perception of high risk during the UK COVID-19 lockdown. Front Public Health. 8(8):575091. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2020.575091.

- Rolewicz L, Keeble E, Paddison C, Scobie S. 2020. Are the needs of people with multiple long-term conditions being met? evidence from the 2018 general practice patient survey. BMJ Open. 10(11):1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041569.

- Roschel H, Artioli GG, Gualano B. 2020. Risk of increased physical inactivity during COVID-19 outbreak in older people: a call for actions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 68(6):1126–1128. doi:10.1111/jgs.16550.

- Sallis JF, Adlakha D, Oyeyemi A, Salvo D. 2020. An international physical activity and public health research agenda to inform coronavirus disease-19 policies and practices. J Sport Health Sci. 9(4):328–334. doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2020.05.005.

- Sallis R, Rohm Young D, Tartof SY, Sallis JF, Sall J, Li Q, Smith G, Cohen DB. 2021. Physical inactivity is associated with a higher risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes: a study in 48 440 adult patients. B J Sports Med. 55(19):1–8.

- Sepulveda-Loyola W, Rodriguez-Sanchez I, Perez-Rodriguez P, Ganz F, Torralba R, Oliveira DV, Rodriguez-Mañas L. 2020. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: mental and physical effects and recommendations. J Nutr Health Aging. 25(10):1–10.

- Siedler MR, Lamadrid P, Humphries MN, Mustafa RA, Falck-Ytter Y, Dahm P, et al. 2021. The quality of physical activity guidelines, but not the specificity of their recommendations, has improved over time: a systematic review and critical appraisal. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 00:1–12.

- Srivastav AK, Khadayat S, Samuel AJ. 2021. Mobile-Based health apps to promote physical activity during COVID-19 lockdowns. J Rehabil Med. 4:1–4.

- Stafford M, Steventon A, Thorlby R, Fisher R, Turton C, Deeny S. 2018. Briefing: understanding the health care needs of people with multiple health conditions. The Health Foundation.

- Stansfield C, Dickson K, Bangpan M. 2016. Exploring issues in the conduct of website searching and other online sources for systematic reviews: how can we be systematic? Syst Rev. 5(191):1–9. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0371-9.

- UK Chief Medical Officers’ PA guidelines. 2019. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/832868/uk-chief-medical-officers-physical-activity-guidelines.pdf

- Woods J, Hutchinson NT, Powers SK, Roberts WO, Gomez-Cabrera MC, Radak Z, Berkes I, Boros A, Boldogh I, Leeuwenburgh C, et al. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic and physical activity. Sport Med Health Sci. 2(2):55–64. doi:10.1016/j.smhs.2020.05.006

- World Health Organisation. 2021a. Physical Activity. https://www.who.int/health-topics/physical-activity#tab=tab_1

- World Health Organization. 2020. Noncommunicable diseases. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases#:~:text=Key%20facts,71%25%20of%20all%20deaths%20globally

- World Health Organization. 2021b. Stay physically active during self-quarantine. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/publications-and-technical-guidance/noncommunicable-diseases/stay-physically-active-during-self-quarantine

- World Health Organization. 2021c. Mental health. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/mental-health