ABSTRACT

The idea of ‘Western Philosophy’ is the product of a legitimation project for European colonialism, through to post-second world war Pan-European identity formation and white supremacist projects. Thus argues Ben Kies (1917-1979), a South African public intellectual, schoolteacher, trade unionist, and activist-theorist. In his 1953 address to the Teachers’ League of South Africa, The Contribution of the Non-European Peoples to World Civilisation, Kies became one of the first people to argue explicitly that there is no such thing as ‘Western philosophy’. In this paper, I introduce Kies as a new figure in the historiography of philosophy with important insights, relevant today. I outline his three key arguments: that ‘Western Philosophy’ is the product of political mythmaking, that it is a recent, largely mid-twentieth century fabrication, and that there is an alternative to ‘Histories of Western Philosophy’, namely ‘mixed’ or entangled histories. I show that Kies’ claims are supported both by contemporary scholarship and bibliometric analysis. I thus argue that Kies is right to claim that the idea of a distinctive, hermetically sealed ‘Western Philosophy’ is a recent, political fabrication and should be abandoned. We should instead develop global, entangled historiography to make sense of philosophy and its history today.

“The West is not in the West. It is a project, not a place.”

Édouard Glissant (Caribbean Discourse, 2)

Introduction

Over the last century, the idea of a ‘Western Philosophy’ has become hegemonic in academia. It is widely and uncritically used as a neutral, pseudo-geographic descriptor. It has also entered wider cultural milieus through popular texts like Bertrand Russell’s (1945) History of Western Philosophy and, more recently, histories like Anthony Gottlieb’s (2000) The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy, Anthony Kenny’s (2010) New History of Western Philosophy or James Garvey and Jeremy Stangroom’s (2012) The Story of Philosophy: a History of Western Thought. While the idea is used by its defenders and detractors alike,Footnote1 remarkably few authors have defined this vague term, or even brought it into view, never mind questioning the very idea. Indeed, while it seems most often deployed to implicitly acknowledge or explicitly highlight the existence of so-called ‘Non-Western Philosophy’,Footnote2 most authors simply take for granted that the term makes sense and picks out something real. It was not always like this. The ideas behind a ‘Western Philosophy’ are relatively recent, emerging primarily in the wake of European colonialism since the sixteenth century and culminating at the turn of the twentieth century, with the term ‘Western Philosophy’ only widely used since the 1940s.

To critique the idea of ‘Western Philosophy’, I introduce the work of Ben Kies (1917-1979), a South African activist-theorist who remains almost unknown, even by contemporary political philosophers in South Africa. Kies is a prime example of a thinker from the Global South who offers insights not only about his own context, but for the historiography of philosophy more globally. Indeed, his 1953 lecture, The Contribution of the Non-European Peoples to World Civilisation, is one of the earliest explicit challenges to the idea of ‘Western Philosophy’ – if not the earliest. His approach, which generally seeks “systematically to demolish the idea of ‘Western Civilisation’”, and specifically ‘Western Philosophy’, is “almost unheard of anywhere in the world at the time” (Soudien, Cape Radicals, 138), and indeed for over half a century thereafter in academic scholarship. Kies highlights that “one of the more important tasks of our time”, sadly still incomplete seventy years later, “is to dissect this myth of “European” or “White” or “Western” or “Christian” civilisation and to give our reply to it, on the level of ideas and in the field of practice” (Contribution, 9). It is only much more recently that academic philosophers have taken direct issue with the idea of ‘Western Philosophy’, especially in South Africa by Lucy Allais’ (2016) Problematising Western Philosophy, and elsewhere including Sean Meighoo (2016) in The End of the West, Eric Nelson’s (2017) Chinese and Buddhist Philosophy, and Christoph Schuringa’s (2020) On the Very Idea of “Western” Philosophy.Footnote3 Even so, the historiography of philosophy has generally yet to recognize the kinds of critiques Kies offers, and especially his key contribution: ‘mixed’ (or entangled), global histories.Footnote4

In the Contribution, Kies forcefully argues that there is no such thing as “Western philosophy”, and that this idea arises as little more than a legitimation project, from European colonialism through to Nazi mythmaking, white supremacist projects, and post-second world war Pan-European identity formation. Moreover, as a conceptual product of a distorted history, “Western Philosophy” does not fit the facts and inhibits our understanding of philosophy and its history. Kies offers more than just critique, however. He presents an alternative to ‘History of Western Philosophy’ narratives: by understanding the history of philosophy as globally ‘mixed’ or entangled. Throughout the Contribution, Kies demonstrates the exchanges, interactions, and hybrid knowledge formations arising throughout global history and the history of philosophy specifically.

In what follows, Section I discusses the common presentations of “Western Philosophy” and the ‘History of Western Philosophy’. In Section II, I introduce Ben Kies and present his 1953 argument that there is no such thing as “Western Philosophy” except as a reframing of colonial-era racial mythology. In Section III, I expand Kies’ argument that the idea of “Western Philosophy” is a “matter of myth and political metaphysics”, supported in Section IV by original quantitative bibliometric evidence, and qualitative evidence from recent scholarship that “Western Philosophy” is a recent fabrication, post-second world war. In Section V, I argue that Kies offers a positive contribution to the historiography of philosophy through the idea of ‘mixed’ or entangled history, reflecting contemporary concerns in the historiography of philosophy while opening new methodological possibilities. Section VI concludes.

I. The idea of ‘Western philosophy’

In 1927, Bertrand Russell (Outline of Philosophy, 1) wrote that philosophy “arises from an unusually obstinate attempt to arrive at real knowledge. What passes for knowledge in ordinary life suffers from three defects: it is cocksure, vague, and self-contradictory”. Unfortunately, his world-famous History of Western Philosophy (1945) adopted precisely such an unphilosophical position towards its core term: never even attempting to explain what “Western Philosophy” is, and thereby succumbing to the defects he identified. Russell’s History, which has been reprinted numerous times, with over 10,000 citations and “probably over two million readers”,Footnote5 has had a massive influence on subsequent ‘Histories of Western Philosophy’. Some of the most recent histories of philosophy have a more global and less Eurocentric scope, including Grayling (2019, The History of Philosophy) and Baggini (Citation2018, How the World Thinks). Nevertheless, even these sources recreate the narrative of hermetically sealed traditions in isolation from one another, whether by relegating ‘non-Western’ traditions to a single separate section (Grayling) or by maintaining a strict comparative dichotomy between ‘Western’ and ‘Non-Western’ philosophy throughout (Baggini).

Moreover, none of these offers a definition of “Western Philosophy”, never mind a philosophical account that is “tentative, precise, and self-consistent” (Russell, Outline, 2). Indeed, as Allais (Problematising, 539) has noted, “a vanishingly small amount of “Western” philosophy is concerned with the question of what makes its philosophical tradition “Western”; this is simply not taken to be a question that requires answering”. The closest to careful explanation of the designator ‘Western’ is in comparative and intercultural philosophy, likely because this branch of philosophy most often uses designators like ‘Eastern’ and ‘Western’. According to Mall (Intercultural, 81), comparative studies generally “mechanically placed philosophies of different traditions side-by-side to highlight rigid contrasts between Western and non-Western philosophies” (emphasis added), claiming to have found profound differences between their styles, approach, content, and subject-matter. Such studies, however, are selective with their evidence and still rarely explain what constitutes “Western Philosophy”, often tending instead simply to reify the category. Intercultural philosophy, by contrast, was supposed to have acknowledged that “phrases like Indian, Chinese, Western, and German philosophy are intellectual constructs” and that in “all traditions … converse with each other” (Mall, Intercultural, 81). However, precious little – even in intercultural philosophy – discusses the genealogy of these “intellectual constructs”, their implications, or, crucially, whether they offer value at all.

To seek explanations of what counts as “Western” philosophy, we are largely left with inferring from what is often implicit in sources like ‘Histories of Western Philosophy’.Footnote6 From this, I suggest, there are four major species of explanation, which I outline here and critique in the remainder of this paper. The first is “Western Philosophy” is a straightforward geographic designator: it is obviously just Philosophy from the West. A second account is that “Western Philosophy” is distinctive because of some unifying essence or unique, inherent characteristic, such as being reasoned, argued, or secular. A third account suggests that there is a tradition, or cultural/intellectual continuity. As Meighoo (End, xii) characterizes this position, the “Western tradition is ostensibly constituted by a continuous line of thought extending from the ancient Greeks to modern European thinkers, a tradition that has remained impervious to all non-Western traditions”. A final species of justification includes ethnocentric celebrations of ‘The West’ and “Western Philosophy” which attempt to give it a ‘Greek/Judeo-Christian’ veneer. Some such narratives also rely on racialized pseudo-scientific biological explanations, if not explicitly racist accounts of history. While rarer today, there are still some fairly influential contemporary scholars who advocate variations of these views (such as Jordan Peterson and Ricardo Duchesne) – even if not always working in the history of philosophy specifically. While most historians of philosophy today would likely disavow this position, Ben Kies’ Contribution helps to illuminate how the very idea of “Western Philosophy” is itself the product of this line of thinking.

II. Ben Kies and the Contribution (1953)

Why is it so difficult to find explanations for what “Western Philosophy” is? One answer is that it is a category of dubious value and origin, and that drawing attention to the category would be to expose its more sordid underbelly for examination. This kind of answer is what Ben Kies offers to explain the political stakes of terminology around ‘The West’ and “Western Philosophy”. Despite what “devotees of the calcified Bertrand Russell” might believe (Contribution, 25), Kies argues that it is nonsensical mythmaking to assert the existence of a “Western Civilisation” with a “Western philosophy” (8).

Benjamin Magson Kies (1917–1979) was a South African radical activist-theorist, public intellectual, schoolteacher, trade unionist, lawyer, and revolutionary socialist. He finished his schooling in 1934 and undertook a BA, MA, and Bachelor of Education at the University of Cape Town, before becoming a teacher at Trafalgar High School in Cape Town. From the mid-1930s, he was associated with the Workers’ Party, the Teachers’ League of South Africa (TLSA) trade union, and the Unity Movement, a group of anti-colonial, anti-racist, and anti-capitalist activists. This milieu generally comprised non-Stalinist socialists, many of whom began working on public education under the banner of the New Era Fellowship over the 1930s-1950s. They challenged not only the white-supremacist governments of the day and collaboration with the regime, but even the very basis of racial thinking (see especially Soudien, Cape Radicals). Together with Helen Kies, his wife, Ben Kies contributed to writing, editing, and disseminating publications, from the more polemical Bulletins and The Torch to the high-quality Education Journal, addressing issues from pedagogy to politics (Braam, Discourse).

Kies was thus an important intellectual in his own right and a prominent figure in this milieu, but also a representative of the kinds of debates that were live and core to radical movements in mid-twentieth century Cape Town and South Africa more widely. Their interventions emerge against a global background of the rise of fascism, socialist revolutions, and the endgame of colonial rule, and they sought to respond to and theorize their “conjuncture”, as Soudien puts it (Re-Reading, 198).Footnote7 In doing so, they often prefigured debates in academic social sciences and humanities by several decades, including on issues like the sociology of “race”, postcolonial theory, world-systems theory, comparative and world history, and history “from below” (Lee, Comparative Imagination; Soudien, Re-Reading). Despite this, Kies’ work (and the Unity Movement more generally) are rarely acknowledged in philosophy circles, even in South Africa.Footnote8

Kies was an outspoken anti-segregationist, who from the early 1940s began challenging the basis on which “Western philosophy” stands, arguing that the categories of “East and West”, and further subdivisions “segregated into races and nations”, have been constructed “in the interests of tyranny and world domination” (Background of Segregation, 1). He highlights how, for oppressors, the “most important weapon has been the enslavement of the mind” (Background of Segregation, 1), and how a unity of theory and action amongst the divided-and-ruled was necessary to overcome segregation, oppression, and racism (Kies, Basis of Unity, 6, 8).

Kies’ contributions to the historiography of philosophy, specifically, are clearest in his 1953 address to the Teachers’ League of South Africa, entitled The Contribution of the Non-European Peoples to World Civilisation. In the Contribution, Kies argues that there is no such thing as “race” or “Western civilisation” – and, by extension, there is no such thing as a “Western man” with a “Western philosophy” (Contribution, 8). Central to his argument is that these “Western” modifiers are implicitly, but inherently, racialized: they are used interchangeably with “White” or “European” (Contribution, 8). As such, they cannot hold: Kies highlights that distinguishing between “European” and “non-European” based on ““racial”, historical, or cultural lines” is largely “a matter of myth and political metaphysics” (Contribution, 9). Drawing on then-contemporary research in genetics, biology, and archaeology, he reaches a conclusion that took decades to become widely accepted: that “the human race is now, as it was when homo sapiens evolved, one biological species”, and that for all the superficial differences there may be, these “have made not the slightest difference to the biological unity of man [sic] as a single species, and provide no scientific basis for a division into what are popularly mis-called ‘races’” (Contribution, 12). While this may sound obvious seventy years later in 2023, it was radical and impactful in 1953, just five years after the start of the Apartheid regime in South Africa, which entrenched legal categorization, definition, and oppression on the very basis of ‘race’.

Kies argues that these ideas – of ‘Western civilisation’, ‘Western philosophy’ and the like – are myths. But they are myths that have found purchase across a wide spectrum. As he puts it, from

South African backvelders,Footnote9 backbenchers and university backscratchers to learned anthropologists, psychologists, Unesco pamphleteers on “The race question in Modern Science” and the Princes of the Church … to the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Pope.

(Contribution, 8)

In the three following sections, I develop three of Kies’ arguments in conversation with more recent scholarship to demonstrate that his key insights were accurate and remain relevant today. These are, (1) That the idea of ‘Western Philosophy’ is a political myth, (2) that ‘Western Philosophy’ is a recent fabrication, and (3), that it is a category produced by a distorted history that inhibits us from understanding the history of philosophy accurately, and that we should instead think in terms of entangled histories.

III. Myths of ‘Western Philosophy’, ‘Western Civilization’, and ‘The West’

Building on Kies’ foundational critique, a key aspect of questioning ‘Western Philosophy’ must involve questioning the very idea that there is a ‘West’ to begin with. Indeed, the term is a suspicious one: seemingly geographic and neutral, common use of the term ‘West’ homogenizes and essentializes a far more complex reality. Three decades ago, authors like Stuart Hall (1992, The West) pointed out that ‘The West’ is discursively constructed through opposition to a series of opposites and ‘Others’, especially the ‘Orient’ or ‘East’. The term “West” was only widely adopted in the twentieth century on racialized geopolitical terms to include Europe and “White” settler-colonies, such as the United States and, problematically for the geographically minded, Australia and New Zealand (Appiah, Lies that Bind, 191). This was always in contradistinction to the “rest”: an amorphous, ever-changing Other against which the “West” was defined, which at various times included a supposedly premodern “Orient”, a communist Eastern Europe and China, a civilization-clashing “Islam”, or generally the colonized peoples of the “third world” in Asia, Africa, and Latin America (GoGwilt, Westernness, 228-9, 248). “The West” has always been “an amalgam of intellectual constructs which were designed to further the interests of their authors” (Davies, Europe, 25). It could never have been purely geographic.

The second approach is to distinguish ‘Western Philosophy’ by some essential or defining characteristic. An exemplar of this approach is Flew (Introduction, 36), who suggests that the subject matter of his book, “Western philosophy”, equates to philosophy as such, because it is “concerned first, last and all the time with argument”. Flew offers a flailing assertion that “because most of what is labelled Eastern Philosophy is not so concerned – rather than for any reasons of European parochialism – that this book draws no materials from any sources east of Suez” (ibid.). Myopic in scope, asserted without evidence, and demonstrably false, this is hardly an argument worthy of its name. It is undermined externally by the existence of philosophy that matches the given criteria (say, Cārvāka-Lokāyata) but would not be considered ‘Western Philosophy’.Footnote10 Moreover, as Allais (Problematising, 543) points out, there is unlikely to be anything close to consensus on the criteria that would constitute ‘Western philosophy’, whether content, topics, approach, or methods.Footnote11

Others suggest a continuity of culture or intellectual tradition, with Ancient Greece as the intellectual foundation for the ‘West’. Narratives of ‘Western Philosophy’ specifically usually rely on this origin myth, beginning with a kind of incantation, ‘in the beginning were the Greeks’, with philosophy emerging from the shift from mythos to logos. As several scholars have argued, however, much of this is simply selective retelling of history, implausible and self-serving (see, e.g. Schuringa, Idea; Meighoo, End). As Kies argues (Contribution, 26), ancient Greek philosophers saw themselves as being in extended discourse with Asian and African predecessors, with the Mediterranean as the hub for trade and knowledge production in the region (see more recently, for example, Whitmarsh & Thomson, Romance). It was only much later, from the eighteenth century, that the historical entanglements of the Greeks with their near-Eastern and African peers were erased from the history of philosophy and replaced with a fully Eurocentric narrative (Bernasconi, Parochialism; Park, Africa; Cantor, Thales). Key twentieth-century French and German philosophers further embedded the trope of cultural origins that served to legitimate the narrative of ‘Western Philosophy’ (Meighoo, End; Nelson, Chinese and Buddhist Philosophy). However, this is not just an issue with origins: as Nelson (Chinese and Buddhist Philosophy, 2) puts it, there is an “ideological spell of a continuous Western identity from the Greeks to the moderns”. However, as various ‘History of Western Philosophy’ narratives cited earlier demonstrate, philosophy in the Islamic world is almost always conspicuously absent, despite responding extensively to ancient Greek philosophers (especially around 700–1200 C.E.) – and impacting philosophy in Europe for centuries thereafter. There is no direct and neat line of intellectual continuity between the ancient Greeks and present-day Europe, much less the recent discourse of the “West” (Bernasconi, Ethnicity, 573), or at a minimum, philosophy in the Islamic world would automatically be considered part of ‘Western Philosophy’. The continuity argument is thus often taken to be about something more substantial than a mere history of ideas.

That substance, usually left unspoken in polite circles, is that of ethnocultural or racial identity, as Kies observes. However, ancient Greeks had no conception of themselves as “European”: as Kies (Contribution, 26) drily notes, Aristotle himself claimed that those living in Europe are “full of spirit, but wanting in intelligence and skill” (Politics VII.7, 1327b19-1328a5). Indeed, ancient Greeks were largely uninterested in (and for centuries ignorant about) the rest of Europe, particularly as regards its northern and westernmost parts (Irby, Mapping, 98). Moreover, as Kies argues, there was no continuity of racial identity stretching back from contemporary ‘White’ Europeans: the framing of ancient Greeks as ‘White’ is itself a modern invention, as contemporary classicists and historians of the ancient world agree (see e.g. Whitmarsh, Black Achilles; McCoskey, Race). The purported racial basis of the ‘West’ is a part of its political-ideological project, and central (albeit often implicit) to its own self-presentation. Like raciology in general, however, this is not grounded in reality. There are, certainly, ideological points of connection in proto-racial and racial theories, with later authors from the eighteenth century drawing on, say, defences of slavery and environmental theories of human difference in Aristotle and the Hippocratic corpus (see e.g. McCoskey, Race, especially 46-49; 54), or that grew out of medieval forms of racialization and racism in Europe (see especially Heng, Invention). Nevertheless, this repugnant history does not justify the claims of racial continuity, whether cast as ‘Aryan’ or ‘White’, to uphold the narrative of ‘Western’ continuity. Moreover, it is precisely this racialized understanding of ‘The West’ that makes visible the exclusion or marginalization from ‘Western Philosophy’ of Black philosophers from within Europe (or the US) – or themes like white supremacy, as Charles Mills (Racial Contract) demonstrated decades ago (Allais, Problematising, 540-1). Of the four main ways of explaining what ‘Western Philosophy’ might be (geographical, essential/characteristic, traditional, or ethnocultural/racial), none succeed. To make sense of why, Kies offers insights into the genealogy of the idea.

IV. ‘Western Philosophy’ as a recent fabrication

Kies’ second key intervention is to argue that ‘Western Civilisation’, and its by-product ‘Western Philosophy’, are not only myths, but recently fabricated ones. Kies’ explanation is that they were created to legitimate European colonial dominance from the 1600s and crystallising only recently: in the twentieth century amongst imperialists, white supremacists, fascists, and in post-second world war Pan-European identity formation.

Kies’ argument (Contribution, 7) is that ideas of the “West” are founded upon the pre-existing “myth of race”, which itself was “a rationalisation of colonial plunder”.Footnote12 As Kies puts it,

Imperialist conquest was offered as claim and proof of the inherent “racial” superiority of the conquerors and the inherent “racial” inferiority of the conquered.

(Contribution, 7)

After the Second World War, these racialized narratives were repurposed to build a common identity across Europe, and to justify continued European dominance globally. In a key passage, Kies argues,

Since the defeat of the “Nordic” Axis, two of the victors, America and Britain, have resurrected and re-minted the Nordic Myth, which is now presented as “Western Civilisation” or “European Civilisation” or “White Civilisation”, with the term “Christian” added whenever divine agreement is deemed suitable. There is a “Western man” with a “Western soul”, a “Western philosophy”, a “Western science” and a “Western way of life”, whose gospel opens with the words: “In the beginning was the West”.

(Contribution, 8)

Fabrication argument: digital humanities quantitative evidence

The digital humanities offer a useful way of assessing Kies’ claim for the novelty and origins of the idea of ‘Western Philosophy’. Digital scholarly database searches can check across decades and even centuries for the relative occurrence of a particular term, indicating the term’s frequency across a textual corpus. This offers insight into general and relative trends, such as when terms like ‘Western Philosophy’ entered widespread usage amongst academics and authors, even if not offering final proof of origin.

I draw on four sources: Google NGram, Scopus, Web of Science, and JStor, doing an initial search across their corpus for ‘Western Philosophy’ on 3rd March 2022. NGram offers a broad overview of printed works, especially published books, that Google has digitized. It displays results as a percentage of matches against total works, tracking the relative proportion of a term’s use in the corpus, indicating its prevalence in a discourse over time. The three other databases return absolute numbers of matches in their corpus, predominantly academic journal articles. The least relevant was Web of Science (WoS), only cataloguing documents since 1900 and focusing on the natural sciences. It nevertheless does index some mentions of ‘Western Philosophy’ across 1900-2022. The second was Scopus, which covers over 82 million documents dating back to 1865, including over 234,000 books. Finally, the most relevant was JStor, focusing on the humanities and social sciences with records of over 12 million journal articles and books, dating back to 1600.

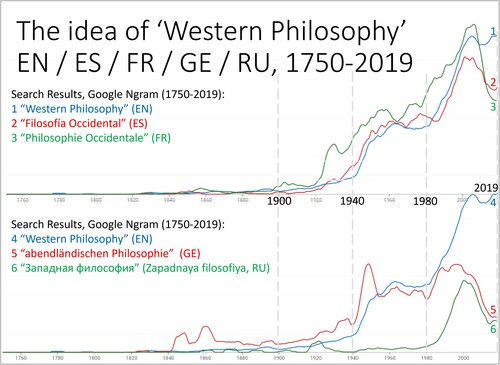

The results are stark: ‘Western Philosophy’ is almost unheard of across any database until the 1900s, and even thereafter is hardly mentioned until the mid-1940s (see ). NGram results demonstrate that, as a proportion of total use, ‘Western Philosophy’ is practically non-existent prior to the 1900s and rises only very gradually until the 1940s. Indeed, its first major spike is precisely in the early to mid-1940s, around the time that Kies identifies “Western Civilisation” emerging as a “resurrected and re-minted” racial myth (Contribution, 8). This rise is most prominent in English-language searches, but roughly equivalent terms in other European languages have similar trajectories, especially in French (‘Philosophie occidentale’) and Spanish (‘Filosofía Occidental’). Interestingly, there are two exceptions to this trend: in Russian, where ‘Zapadnaya Filosofiya’ only becomes widely used in the 1980s towards the end of the Cold War, and in German, where ‘Abendländischen Philosophie’ is used prior to the 1940s, but with a distinctive meaning from ‘Western Philosophy’ until then, discussed below. From the 1940s, there is a dramatic spike in references to ‘Abendländischen Philosophie’ as the term become more synonymous with ‘Western Philosophy’.

Figure 1. NGram results (1750-2019): ‘Western Philosophy’ (EN), ‘Philosophie occidentale’ (FR), ‘Filosofía Occidental’ (ES), ‘Zapadnaya Filosofiya’ (RU), ‘Abendländischen Philosophie’ (GE). Author Created.

This is similar in journal-focused databases (). On WoS, searching all databases for ‘Western Philosophy’ prior to 1945 returns only one result (in 1943), out of roughly 850,000 documents indexed. Of the 8,808 results for ‘Western Philosophy’ on Scopus across its corpus, only a single result (in 1918) is returned prior to 1945 (of almost 900,000 documents indexed for that period). Jstor finds 21,488 matches for ‘Western Philosophy’, but only 256 between 1600-1945, mostly from 1918–1945 (the three centuries between 1600–1918 return only 33 results). This is not for lack of records: JStor catalogues over 2 million documents prior to 1945.

Table 1. Pre-/Post-1945 bibliometrics, ‘Western Philosophy’ (EN). Author created.

Bibliometric analysis demonstrates that mentions of ‘Western Philosophy’ were rare prior to 1945, with only 259 mentions out of almost 4 million articles and books. Although this cannot confirm the reasons, the fact that there is an explosion of discussion of ‘Western Philosophy’ almost entirely after the Second World War does offer prima facie evidence for Kies’ claim that the idea of ‘The West’ is a recent fabrication, and likely that there was some significant change in global society and knowledge production.

Fabrication argument: qualitative evidence

The quantitative evidence confirms that Kies was correct to argue in 1953 that ‘Western Philosophy’ was a recent fabrication. But was it the product of World War II’s victors reinscribing Nazi racial mythology under a ‘Western’ banner? The most relevant scholarly literature of the last three decades indicates that the idea of ‘The West’ does not originate in the mid-1940s. The idea had already existed, loosely, from the nineteenth century in Europe, the United States, Russia, and some east Asian countries.

However, Kies’ fundamental political argument is nevertheless supported, even if he is mistaken about the term’s origin date. Like Kies, Bonnett (Idea of the West) argues that there was a shift in identification from ‘white’ to ‘Western’ that took place in Britain (and hence also its extensive Anglophone empire), although dates this to the turn of the twentieth century. From the late 1800s, British imperialist interests increasingly claimed their actions were in defence of “The West”, as a discursive justification for European conquest, with “apocalyptic” warnings of the destruction of “Western Civilisation” (GoGwilt, Westernness, 248). Indeed, as Bavaj & Steber (Germany, 6, 16) argue, terms like “The West” and “Western Civilization” became widely adopted to provide an alternative to “white civilization” that “avoided untenable assumptions about racial homogeneity without precluding racist overtones” and was “reconcilable with racist and social Darwinist assumptions in the established colonial empires”. Kies’ argument is supported by contemporary scholarship: such categories are marked by their birth as imperialist and racist ideas.

In philosophy specifically, only a handful of works originally written prior to WWII use the specific term, ‘Western Philosophy’. As Eric Schliesser (What’s Western) has pointed out, pre-1914 uses of ‘Western Philosophy’ are “negligible”, “very idiosyncratic”, and far from settled. Several of these earlier uses of ‘Western Philosophy’ are specifically comparative and geographical, sometimes meaning ‘Western Roman Empire’, in other cases attempting to distinguish something happening in Western Europe from philosophy in India, China, or Russia and Eastern Europe. Some are entirely obscure, singular, one-off uses, such as referring to Emerson as having founded a “new, Western philosophy” (Aylesworth, Educational Values). The term lacked a stable, commonly understood referent.

In European scholarship, pre-1945 uses do not define, explain, or clarify the term, but often slip between using ‘White’ and ‘Western’ interchangeably. Prominent British classicist F.M. Cornford, for example, in From Religion to Philosophy: A Study in the Origins of Western Speculation (1912), addressed “that period, in the history of the western mind, which marks the passage from one to the other” (v) and contrasts the Greek achievements in philosophy and science from the “savage tribes comparatively untouched by white civilisation” (79).Footnote13 Cornford also labels Thales the “father of western philosophy” (4). Others, like Kline (Citation1939, First Philosopher), also present Thales as first, simultaneously acknowledging that “the predecessors from whom he learned were Egyptian and Syrian” while implicitly distinguishing these from the history of “western philosophy” without offering a word of explanation for why (81).

The term is also used, albeit rarely, in histories of philosophy. Sabine (1937, History of Political Theory), for instance, claims to outline the “history of Western political theory” (vi), and once mentions “the rational tradition of Western philosophy” (925), without explaining this further. The earliest use of ‘Western Philosophy’ in a work’s title seems to be from Japan: Amane Nishi’s 1862 Lecture Fragments on the History of Western Philosophy ( 「西洋哲学史の講案断片」) (Greco, Die Begegnung, 73).Footnote14 Nishi imported the term “philosophy” as tetsugaku (哲学) from European writings of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, while maintaining the “exclusivist” understanding of the borders of philosophy and equating “Western Philosophy” to “Philosophy” as such (Krings et al., Histories, 24-26).

Most of these references are one-off, unexplained, and often gestural. But they are also unstable, sometimes fading away after a particular war or great power struggle or losing their meaning as geopolitics changed. They are never widely accepted or used uniformly. For most of the 1800s and until the mid-1900s, for instance, there was much ambiguity and ambivalence as to whether Germany was a part of the “West” (Bavaj & Steber, Germany, 14). The term occasionally took on specific meanings, often racialized, but just as easily dropped out of use without a war or anti-immigrant panic. As Bavaj & Steber (Germany, 14) argue, “in the wider discursive context, the concept of the West did not re-emerge in full use until 1914” in Germany, and even then, Germany was still taken to be in opposition to “the West”.Footnote15 Indeed, they demonstrate that it was only after 1945 that Germany became a part of ‘The West’, which by then had primarily taken on new meanings, especially shaped by pan-European identity formation in the context of the Cold War and decolonization. Those who believe in ‘Western Philosophy’ today are unlikely to imagine German Idealism being excluded from it. The term’s current usage is thus strange in historical terms – demonstrating how recently it has adopted its current patterns of meanings.

Kies argues that the idea of ‘Western Philosophy’ is a recent fabrication. His central claim here is that the victors of World War II “resurrected and re-minted” racial mythology as “Western”. Recent scholarship confirms that this is a (partial) account of the origins of how terms like ‘The West’ and ‘Western Philosophy’ in use today took root and became widespread, with the stability, obviousness, and unquestionability now widely associated with them. However, Kies does not explain why the term ‘West’ was used in the first place. Drawing on his work and the recent scholarship, I suggest it is because ‘Western’ was (a) already used erratically, including being used interchangeably with ‘White’, and thus would not have been entirely unfamiliar (especially to audiences in Europe); while (b) having no stable referent, thus being easily redefined and repurposed to fabricate a tradition; it was also (c) capacious enough to include Germany, the US, and other colonial empires in a project of post-war Euro-American identity-formation; while (d) masking the horrors of racial ideology in the wake of Nazism behind a seemingly neutral geographic designator. If so, ‘Western Philosophy’, although slippery and ambiguous, is indelibly marked by its genesis as a political project: the term subtly indicates (‘dogwhistles’) a racialized, ethnocultural understanding of the history of philosophy, while granting itself plausible deniability to defer to geography, unique characteristics, or an intellectual tradition.

V. From the ‘History of Western Philosophy’ to entangled histories of philosophy

As such, Kies argues, terms like ‘Western Philosophy’ (and ‘Western Civilisation’ generally) are little more than the latest iteration of colonial ideology, a recently (1940s) recast myth to justify imperialism, racism, and exploitation. Dispelling the myths would mean recognising that there is no such thing as ‘Western Philosophy’; if so, it would be nonsensical (or purely propagandistic) to narrate the ‘History of Western Philosophy’.Footnote16 If not with reference to that, how else could we then understand philosophy’s history?

Here, Kies’ third contribution becomes central, offering a way out of the binds of ‘Western Philosophy’ that have constricted broad narratives of the history of philosophy, with an alternative for such historiography today. Kies argues that once we have “deflated” the “myth of “Western”, “European”, or “White” civilisation”, it becomes possible to think afresh (Contribution, 25). As he puts it, we should understand,

Not “European” civilisation, but civilisation in Europe; not “Western” civilisation, but civilisation in the so-called West; not “Western” philosophy, science, art, music, architecture, literature – but the development of these accomplishments of civilisation in Europe.

(Contribution, 25)

a special group or “racial” or national genius, still less upon individual geniuses isolated from, and elevated above, the toiling, sweat-begrimed mass

(Kies, Contribution, 23).

Writing entangled histories of philosophy today

In recent decades, amidst the latest iterations of globalization, philosophers have begun to delineate ‘intercultural’ and ‘comparative’ philosophy as areas of serious scholarship.Footnote18 Mall (Intercultural Philosophy) claims this is a “new orientation in and of philosophy”. While only recently given the title ‘intercultural’, such philosophising has in fact existed for millennia. Eric Nelson argues that the “history of Western philosophy is historically already interculturally and intertextually bound up with non-Western philosophy”. There is, he argues, a long history of this in a

multidimensional space of encounter between philosophies of different social-historical provenience, each of which is a complex dynamic formation that cannot be fixated and reduced to the identity of a cultural or linguistic essence, or racial type, underlying a supposedly unitary community or tradition.

(Chinese and Buddhist Philosophy, 3)

Shifting attention from individuals to the standard periodization of the ‘History of Western Philosophy’ reveals a similar pattern: periods that are taken to be paradigmatic of ‘Western Philosophy’ are themselves deeply intertwined with exchanges of ideas, reflections, rebuttals, and general interaction with places and people beyond any European borders. This dynamic is hardly new. Kies himself (Contribution, 26) highlights that “in philosophy, generally acknowledged to be the greatest contribution to civilisation made by the Greeks, it is equally true that the roots were in the East, outside Europe”. The Greeks, he highlights, “were as happily intermixed as any of the [other] peoples” of the ancient world, where “the greatest cultural developments came from those parts where there was the greatest mixing”, and specifically that “it was in the most “mixed” part that the very flower of Greek philosophy flourished, namely, the Ionian school” (Contribution, 26). Recent scholarship has supported this claim, exploring the entangled history of philosophy in Ancient Greece in the broader context of its exchanges with Babylonia, Egypt, and indeed as far afield as India (Beckwith, Greek Buddha; Rutherford, Greco-Egyptian Interactions; Stevens, Greece and Babylonia). Indeed, Cantor (Thales) reaffirms that, contrary to contemporary common-sense, most Greek thinkers themselves acknowledged prior, non-Greek traditions and did not advocate a Greek origin of philosophy.

The trend holds throughout late antiquity and into the medieval period, especially with interactions between thinkers in North and West Africa and the Middle East with those in Europe, as Kies highlights on several occasions (Contribution, 31, 35, 37). Rome, “even more so [than] Greece”, boasted a culture “created by a thoroughly “mixed” population from North Africa, Western Asia and the Mediterranean Basin, and the end-result was as cosmopolitan as the people who achieved it” (Contribution, 27). This pattern continued: over the medieval period, Kies cites Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre in saying that “European and African interests were deeply intermingled” (Contribution, 31). This has been extensively demonstrated by more recent scholars like Peter Adamson (Islamic World) and Souleyman Bachir Diagne (Decolonizing the History). Indeed, scholars such as Saliba (Islamic Science), and Hobson (Eastern Origins) have argued that the creative effervescence of the period commonly understood as the Renaissance in Europe would not have been possible without key intellectual and philosophical advances learnt from elsewhere, especially from the Islamic world.Footnote20

This accelerates around the turn of the sixteenth century, in the ‘early modern’ period, with European colonial expansion and the interaction of Europeans with people from across the planet more widely. Take, for example, what is generally understood as the Enlightenment in Europe. Graeber and Wengrow (Dawn of Everything, Chapter 2) argue that critique by indigenous peoples in the Americas under colonization became a central impetus for debates in Europe around liberty, equality, secularism, and progress – defining markers of political philosophy of the period and since. Laurent Dubois (Enslaved Enlightenment) has argued for the centrality of the transatlantic slave trade, and especially Caribbean plantation slavery, for philosophical debates about personhood and humanism, ethics, and political philosophy more broadly: enslaved people, predominantly Africans, who escaped (maroons) and resisted colonial slavery became real-world models for radical political theories of free individuals with natural rights developing in enlightenment-era Europe (see also Conrad, Enlightenment, 1014).

Some of the most dynamic areas in the historiography and history of philosophy over the last decades have been in documenting interactions between philosophers in Europe and the Islamic world, India, and China, including several works that demonstrate the centrality of thinkers in the Islamic world for the Enlightenment (such as Attar, Vital Roots; Garcia, Islam and the English Enlightenment, or Bevilacqua, Republic of Arabic Letters). The influence of Indian and Chinese philosophy in Europe has been widely documented over the last few decades (e.g. Halbfass, India and Europe; Clarke, Oriental Enlightenment; Macfie, Eastern Influences on Western Philosophy), with recent work by scholars like Ambrogio (Chinese and Indian Ways). What these works demonstrate is the extensive engagement amongst philosophers in Europe with sources and ideas often dubbed ‘Oriental’, but which variously formed important bases for their own philosophical contributions, foils for their own arguments, and new ways of understanding the world, nature, politics, society, religion, and a host of other philosophical issues.Footnote21

Histories of philosophy, and especially of ‘Western Philosophy’, have largely erased philosophical contributions from beyond Europe. This is largely rooted in late eighteenth-century historiography, especially due to racism and colonial arrogance on the part of historians and philosophers in Europe (Park, Africa; Bernasconi, Parochialism; König-Pralong, Colonie). In this period, women were also systematically erased from the history of philosophy, as feminist scholarship has shown (e.g. O’Neill, Disappearing Ink; Ebbersmeyer, Memorable Place). To be able to write new histories of philosophy that are neither parochial nor patriarchal, further research is needed to explore the relationships between these erasures, while expanding the literature on marginalized figures and traditions, as journals like the BJHP have begun doing (Beaney, Twenty-Five Years).

Demonstrated by Ben Kies’ 1953 Contribution, and supported by recent literature, there is no history of ‘Western Philosophy’ that can accurately be told in the absence of philosophy from beyond Europe: from across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. As Meighoo (End, xii) argues, “this Western tradition has been punctured by innumerable points of contact with other intellectual traditions as well as by innumerable points of rupture within”. If this was only a matter of several (or even many) points of influence and contact, then a ‘History of Western Philosophy’ that fills that gap and addresses those connections ought to be sufficient.

However, Kies’ earlier arguments reveal a further problem: the vague and ambiguous descriptor ‘Western’ equivocates between a seemingly neutral geographic descriptor and a more substantive political-racial term that emerges from recent racist and colonial efforts to categorize and control. The problem, then, is deeper: no history that adopts the category of ‘Western Philosophy’ can avoid its baggage; no such history can accurately tell a history of philosophy, for its very conceptualization as ‘Western’ means that it fixes in place the conceptual outcome of a distorted history. A ‘History of Western Philosophy’ is retrogressive; the future of the history of philosophy must recognize entanglement.

VI. Conclusion

This paper has identified a problem central to the history of philosophy: that one of its most common terms, ‘Western Philosophy’, is vague and ambiguous at best, and the product of distorted, racist historiography at worst. To understand why, I have introduced a new figure to the historiography of philosophy: Ben Magson Kies, a twentieth-century South African activist-intellectual. Kies, in his 1953 Contribution, argues that the idea of a ‘Western Philosophy’ is a recently fabricated political myth, grounded in racial thinking, and becoming widespread from the 1940s. Emerging from justifications for European imperialism, Nazism, and post-second world war Euro-American identity formation, the idea fails to capture the history of philosophy accurately and with explanatory power. It should be abandoned. Kies’ insights are supported by recent developments in academic scholarship (in e.g. Allais, Problematising), and philosophers have begun to question the idea of a distinctive “Western Philosophy”, “hermetically sealed off” from other parts of the world (Schuringa, Idea). I have also presented qualitative and original quantitative evidence that Kies is correct to identify the proliferation of the idea as a recent (1940s) development.

In place of ‘Histories of Western Philosophy’, Kies points towards an alternative conceptualization: seeing the history of philosophy as profoundly ‘mixed’, with entanglements between regions and thinkers as the norm for millennia, not only in Europe but globally. The historiography of philosophy broadly has yet to reflect such insights, although there are such recent developments in individual studies and adjacent disciplines, such as global history.Footnote22 Dissolving the conceptual rigidity around ‘Western Philosophy’ would help make visible the philosophical contributions of people globally, against the racism, sexism, and imperial arrogance in the formation of the philosophical canon. A ‘mixed’ or entangled history of philosophy, recognising contributions from across the planet under specific historical conditions, would contribute to global epistemic justice (Chimakonam, African Philosophy). Ben Kies offers the foundation for a global, entangled history of philosophy: an overarching conceptual framework that makes sense of interconnections between specific figures, themes, and debates, without recourse to problematic pre-established categories like ‘Western Philosophy’ to which reality never quite corresponds.

Acknowledgements

This paper develops research for a project entitled The Myth of “Western Philosophy”, conducted with Lea Cantor, to whom I am deeply indebted and without whom this work would not exist. I would also like to thank Michael Nassen Smith, who initially introduced me to the work of Ben Kies; Peter Adamson and Jonathan Egid, who read earlier drafts of the paper; Lucy Allais, who gave valuable feedback on an earlier draft; and two anonymous reviewers for their encouraging comments. Finally, I wish to thank colleagues who gave critical and valuable feedback on numerous aspects of the paper in seminars and conferences, especially at the 2022 British Society for the History of Philosophy annual conference in Edinburgh, as well as from the University of Cape Town, South Africa, to Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, to Universität Hildesheim’s HiPhi: Histories of Philosophy in a Global Perspective group in Germany, and the Associação Latino-Americana de Filosofia Intercultural (ALAFI) in Brazil.

Notes

1 Russell being an exemplar of the former, with the latter position taken by numerous critics in so-called ‘Non-Western Philosophy’ and decolonial theory; see, for example, Grosfoguel (Epistemic Decolonial Turn).

2 In both cases, authors’ motivations may be modest and reasonable, even to ‘provincialize’ so-called ‘Western Philosophy’ and situate it as one-amongst-many.

3 In several important papers, Robert Bernasconi (e.g., Parochialism, 213; Ethnicity, 573) also casts aspersions on the term, referring for instance to the “so-called Western philosophical tradition” and using scare quotes around ‘Western Philosophy’, while making many of the crucial substantive arguments that I address in this paper. He does not, however, directly address it as a category, its genealogy, or ramifications. More generally, many scholars over the last decades have pointed to the incoherence of the very idea of ‘The West’ and ‘Western Culture’, including David Graeber, who nevertheless deploys the idea of “the Western philosophical tradition” (There Never Was a West, 338), and more recently Kwame Anthony Appiah in his well-known 2016 Reith Lectures, published as The Lies that Bind (191-211), though without focusing much on ‘Western Philosophy’ specifically.

4 Kies uses the term ‘mixed’, while contemporary global historiographical scholarship tends to speak of ‘cross-cultural’, ‘connected’, or ‘Histoire Croisée’ approaches. I have adopted ‘entangled’ largely because it points to the depth of connectedness and difficulty of separating out supposedly different ‘cultures’ or units, thereby preserving Kies’ insights, while updating the terminology to speak to contemporary scholarship.

5 Citation count from Google Scholar as of 13th April 2022. Readership estimated by Gottlieb, Anthony. “Introduction to the Collectors’ Edition”. In: History of Western Philosophy, by Bertrand Russell. London: Routledge, 2009 [1945].

6 Such as those mentioned above by Russell, Gottlieb, Kenny, Garvey and Stangroom, Grayling and Baggini.

7 Kies’ three core texts are the 1943 Background of Segregation, a critique of the role of ideology in political domination and outlined the role of intellectuals in political movements; the 1945 Basis of Unity, which addressed questions of the relationship between theory and practice, political strategy and tactics, and especially how to build solidarity across difference; and the 1953 Contribution. Developing across each is a critical theory of ‘race’ and its relationship to imperialism and capitalism. Alongside are vast numbers of shorter texts, many anonymous or collectively written, published especially in the Bulletin, The Torch, and Education Journal (Soudien, Re-Reading, 194).

8 For important exceptions, see Soudien (Contribution and Re-Reading), Erasmus (Non-Racialism), and Hull (Unity Movement). As Soudien (Re-Reading, 192) points out, however, it is not just in philosophy circles: there are precious few scholarly sources that assess the work of Ben Kies specifically. Kies’ work (and that of the Unity Movement) has often been marginalized relative to the focus on activist intellectuals linked to the African National Congress (ANC) or Black Consciousness Movement (BCM). Crain Soudien and a colleague are currently working on a political biography of Ben Kies (Personal Communication, 8 March 2023).

9 Roughly, ‘people from the back bush’, a term likely used to refer to rural Afrikaner farmers.

10 Even if there may have been some influence from Cārvāka-Lokāyata on thinkers in Europe from the late sixteenth century (Wojciehowski, East-West Swerves).

11 There is, after all, little consensus even on the boundaries and relationship between ‘analytic’ and ‘continental’ philosophy!

12 More recent scholarship has traced longer histories of race-making/racialization in Europe (see e.g., Heng, Invention; McCoskey, Race). Nevertheless, ‘race’ becomes a politically central organising principle at a world-systemic scale after the Spanish Reconquista, through the colonial conquests of the Americas, and especially in the transatlantic slave trade (although precise timings and relationships remain contentious; see e.g., Hanchard, Race, 485). Here, I maintain that Kies is correct – even if racialization was reconstituted and repurposed from earlier iterations, it was deployed as a “rationalisation of colonial plunder”, and given its global impacts, it is this process that we can call “world-historic”.

13 Cornford himself changed his mind, critiquing and ridiculing these views towards the end of his life, as recorded in his posthumously published Principium Sapientiae (1952).

14 The earliest reference at all to ‘Western Philosophy’ seems either to come from the “Letters Writ by a Turkish Spy” (c.1690s in French; see Schliesser, Origin), although this is an oblique passing reference in a disputed source, and does not correspond to any contemporary usage; or Chōei Takano’s 1835 notes in Japanese (“The Theories of Western Philosophers”, 西洋學師の説) on the history of natural philosophy from Thales to the eighteenth century (Greco, Die Begegnung, 73).

15 To complicate matters, in the early 1900s, German authors could even remain discursively ‘Anti-Western’ (referring especially to Britain, France and the US) while using ‘Okzident’ (Occident) or ‘Abdendland’ (lit. Evening Land) to describe various assemblages of geopolitical/cultural entities, which could include Germany (Bavaj & Steber, Germany, 20).

16 Except, of course, as a history of how this misleading idea emerged.

17 It is this constraint that has led to absurd tangles for some historians of philosophy, paradigmatically when the classicist Eduard Zeller claimed that it was “most natural to call Philosophy Greek, so long as there is in it a preponderance of the Hellenic element over the foreign, and whenever that proportion is reversed to abandon the name” (History, 9-10).

18 Such approaches have also flourished in other areas of history in recent decades, from Global and ‘connected histories’ (Conrad, Global History; Subrahmanyam, Connected History) and Histoire Croisée (Werner & Zimmermann, Beyond Comparison) to Global and Cross-Cultural Intellectual History (Moyn & Sartori, Global Intellectual History; Shogimen, Dialogue). However, these have yet to be widely acknowledged in the history of philosophy specifically.

19 Although entangled histories are clearly not uniquely between Europe and Elsewhere.

20 Such exclusions necessitate mental gymnastics in ‘histories of Western philosophy’, such as highlighting the four-century-long importance of ‘Latin Averroism’ in Europe from the 1200s (e.g., Sabine, 1937, History), without mentioning Ibn Rushd (1125-1198, Latinized as Averroes) or his milieu.

21 This has continued over the last century: theorising of concepts like the state, nation, citizenship, and indeed humanity in Euro-America have been reshaped by struggles of anti-colonial revolutionaries (Getachew, Worldmaking After Empire), including black women from Africa and the Americas (Joseph-Gabriel, Reimagining Liberation).

22 In the history of philosophy, the closest debates are as recent as 2020 in Gordon et al (Creolizing the Canon), although this still uses the idea of ‘Western Philosophy’.

Bibliography

- Adamson, Peter. Philosophy in the Islamic World. A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, Vol. 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Allais, Lucy. “Problematising Western Philosophy as one Part of Africanising the Curriculum”. South African Journal of Philosophy 35, no. 4 (2016): 537–545.

- Attar, Samar. The Vital Roots of European Enlightenment: Ibn Tufayl’s Influence on Modern Western Thought. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2010.

- Ambrogio, Selusi. Chinese and Indian Ways of Thinking in Early Modern European Philosophy: The Reception and the Exclusion. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

- Appiah, Kwame Anthony. The Lies That Bind: Rethinking Identity. London: Profile Books, 2019.

- Aylesworth, Barton O. “Educational Values.—(III.)”. The Journal of Education 70, no. 5 (1909): 119-120.

- Baggini, Julian. How the World Thinks: A Global History of Philosophy. London: Granta, 2018.

- Bavaj, Riccardo, and Martina Steber. Germany and ‘The West’: The History of a Modern Concept. New York: Berghahn, 2015.

- Beaney, Michael. “Twenty-five years of the British Journal for the History of Philosophy”. British Journal for the History of Philosophy 26, no. 1 (2018): 1–10.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. Greek Buddha: Pyrrho’s Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

- Bernasconi, Robert. “Philosophy’s Paradoxical Parochialism: The Reinvention of Philosophy as Greek”. In Cultural Readings of Imperialism, edited by Keith Ansell-Pearson, Benita Parry, and Judith Squires, 212–226. London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1997.

- Bernasconi, Robert. “Ethnicity, Culture and Philosophy”. In The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy, 2nd Edition. Edited by Nicholas Bunnin, and E. P. Tsui-James, 567-581. London: Blackwell, 2003 [1996].

- Bevilacqua, Alexander. The Republic of Arabic Letters: Islam and the European Enlightenment. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Bonnett, Alastair. The Idea of the West. New York: Palgrave, 2004.

- Braam, Daryl. “The Discourse of the New Unity Movement: Recalling Progressive Voice”. Education as Change 22, no. 2 (2018): 1–25.

- Cantor, Lea. “Thales – the ‘First Philosopher’? A Troubled Chapter in the Historiography of Philosophy”. British Journal for the History of Philosophy 30, no. 5 (2022): 727–750.

- Chimakonam, Jonathan O. “African Philosophy and Global Epistemic Injustice”. Journal of Global Ethics 13, no. 2 (2017): 120–137.

- Clarke, J. J. Oriental Enlightenment: The Encounter Between Asian and Western Thought. London: Routledge, 1997.

- Conrad, Sebastian. What is Global History? Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Conrad, Sebastian. “Enlightenment in Global History: A Historiographical Critique”. The American Historical Review 117, no. 4 (2012): 999–1027.

- Cornford, F. M. From Religion to Philosophy: A Study in the Origins of Western Speculation. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1957 [1912].

- Cornford, F. M. Principium Sapientiae: The Origins of Greek Philosophical Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952.

- Davies, Norman. Europe: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Diagne, Souleymane Bachir. “Anton Wilhelm Amo Lectures: Decolonizing the History of Philosophy”. In Anton Wilhelm Amo Lectures, Vol. 4, edited by Matthias Kaufmann, Richard Rottenburg, and Reinhold Sackmann. Halle-Wittenberg: Martin-Luther-Universität, 2018.

- Dubois, Laurent. “An Enslaved Enlightenment: Rethinking the Intellectual History of the French Atlantic *”. Social History 31, no. 1 (2006): 1–14.

- Ebbersmeyer, Sabrina. “From a ‘Memorable Place’ to ‘Drops in the Ocean’: On the Marginalization of Women Philosophers in German Historiography of Philosophy”. British Journal for the History of Philosophy 28, no. 3 (2020): 442–462.

- Erasmus, Zimitri. “Rearranging the Furniture of History: Non-Racialism as Anticolonial Praxis”. Critical Philosophy of Race 5, no. 2 (2017): 198–222.

- Fanon, Frantz. Black Skins, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markman. London: Pluto, 2008 [1952]. Originally published as Peau Noire, Masques Blanc (Paris: Editions de Seuil, 1952).

- Flew, Antony. An Introduction to Western Philosophy. Revised Edition. London: Thames and Hudson, 1989 [1971].

- Garcia, Humberto. Islam and the English Enlightenment 1670-1840. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

- Garvey, James, and Jeremy Stangroom. The Story of Philosophy: A History of Western Thought. London: Quercus, 2013 [2012].

- Getachew, Adom. Worldmaking After Empire: The Rise and Fall of Self-Determination. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019.

- Glissant, Édouard. Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996 [1989].

- Gordon, Jane Anna, Gopal Guru, Sundar Sarukkai, Kipton E. Jensen, and Mickaella L. Perina. “Creolizing the Canon: Philosophy and Decolonial Democratization?”. Journal of World Philosophies 5, no. 2 (2020): 94–138.

- GoGwilt, Christopher, Holt Meyer, and Sergey Sistiaga (Eds). Westernness: Critical Reflections on the Spatio-Temporal Construction of the West. Berlin: de Gruyter, 2022.

- Gopnik, Alison. “Could David Hume Have Known About Buddhism?: Charles François Dolu,: The Royal College of La Flèche, and the Global Jesuit Intellectual Network”. Hume Studies 35, no. 1&2 (2009): 5–28.

- Gottlieb, Anthony. The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. New York; London: Penguin Books, 2016 [2000].

- Graeber, David. “There Never Was a West”. In Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire, edited by David Graeber, 329–374. Oakland, CA: AK Press, 2007.

- Graeber, David, and David Wengrow: The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity. London: Allen Lane, 2021.

- Grayling, Anthony C. The History of Philosophy: Three Millenia of Thought from the West and Beyond. London: Penguin Books, 2020 [2019].

- Greco, Francesca. “Die Begegnung mit den eigenen Schatten: Polylogisches Philosophieren in globaler Perspektive zur Zeit der Dekolonisierung”. In Polylog als Aufklärung? Interklulturell-Philosophsche Impulse, edited by Franz Gmeiner-Pranzl, and Lara Hofner, 49–82. Wien: Facultas, 2023.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón.: “The Epistemic Decolonial Turn” Cultural Studies 21, nos. 2-3 (2007): 211-223.

- Halbfass, Wilhelm. India and Europe: An Essay in Philosophical Understanding. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1990.

- Hall, Stuart. “The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power”. In Formations of Modernity, edited by Stuart Hall, and Bram Gieben. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995 [1992].

- Hanchard, Michael G. “Dialogue: Race in the Capitalist World-System, Author Responses”. Journal of World-Systems Research 25, no. 2 (2019): 484–489.

- Heng, Geraldine. The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Hobson, John M. The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Hull, George. “Neville Alexander and the non-Racialism of the Unity Movement”. In Debating African Philosophy, edited by George Hull, 75–96. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Irby, Georgia L. “Mapping the World: Greek Initiatives from Homer to Eratosthenes”. In Ancient Perspectives: Maps and Their Place in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and Rome, edited by Richard J.A. Talbert, 81–108. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Joseph-Gabriel, Annette K. Reimagining Liberation: How Black Women Transformed Citizenship in the French Empire. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2020.

- Kenny, Anthony. A New History of Western Philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2010.

- Kline, Susan W. “The First Philosopher of the Western World”. The Classical Journal 35, no. 2 (1939): 81–85.

- Kies, Ben. The Background of Segregation. Durban: APDUSA, 1943. 29 May. Available Online: https://vital.seals.ac.za/vital/access/manager/Repository/vital:33176 [Accessed 5 April 2022]

- Kies, Ben. The Basis of Unity. Cape Town: Non-European Unity Movement, 1945, 4-5 January. Available Online: http://www.apdusa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/bbunity.pdf [Accessed 5 April 2022]

- Kies, Ben. 1953. The Contribution of the Non-European Peoples to World Civilisation. Cape Town: Teachers’ League of South Africa, 1953, 29 September. Available Online: https://www.tinyurl.com/KiesContribution [Accessed 5 April 2022]

- König-Pralong, Catherine. La Colonie Philosophique. Écrire L'histoire de la Philosophie aux XVIIIe-XIXe Siècles. Paris: EHESS, 2019.

- Krings, Leon, Yoko Arisaka and Tutsuri Kato (eds). Histories of Philosophy and Thought in the Japanese Language: A Bibliographical Guide from 1835 to 2021. Hildesheim: Universitätsverlag Hildesheim, 2022.

- Lee, Christopher Joon-Hai. “The Uses of the Comparative Imagination: South African History and World History in the Political Consciousness and Strategy of the South African Left, 1943–1959”. Radical History Review 92 (2005): 31–61.

- Perkins, Franklin. Leibniz and China: A Commerce of Light. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Mall, Ram Adhar. “Intercultural Philosophy: A Conceptual Clarification”. Confluence: Journal of World Philosophies 1 (2014): 67–84.

- Macfie, Alexander Lyon (Ed). Eastern Influences on Western Philosophy - A Reader. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2003.

- McCoskey, Denise Eileen. Race: Antiquity and its Legacy. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021 [2012].

- Medien, Kathryn. “Foucault in Tunisia: The Encounter with Intolerable Power”. The Sociological Review 68, no. 3 (2020): 492–507.

- Meighoo, Sean. The End of the West, and Other Cautionary Tales. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

- Moyn, Samuel, and Andrew Sartori (Eds), Global Intellectual History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

- Nelson, Eric S. Chinese and Buddhist Philosophy in Early Twentieth-Century German Thought. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017.

- O’Neill, Eileen. “Disappearing Ink: Early Modern Women Philosophers and Their Fate in History”. In Philosophy in a Feminist Voice: Critiques and Reconstructions, edited by Janet A. Kourany, 17–62. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

- Park, Peter K. J. Africa, Asia, and the History of Philosophy: Racism in the Formation of the Philosophical Canon, 1780–1830. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2013.

- Russell, Bertrand. An Outline of Philosophy. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1927.

- Russell, Bertrand. History of Western Philosophy. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1947 [1945].

- Rutherford, Ian (Ed). Greco-Egyptian Interactions: Literature, Translation, and Culture, 500BCE-300CE. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Sabine, George H. A History of Political Theory. 3rd Edition. London: George G. Harrap & Co., 1968 [1937].

- Saliba, George. Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

- Schliesser, Eric. 2020. “What's Western in Russell's History of Western Philosophy (II)”. Digressions&Impressions. January 8, 2020. https://digressionsnimpressions.typepad.com/digressionsimpressions/2020/01/whats-western-in-russells-history-of-western-philosophy-ii.html

- Schliesser, Eric. 2020. “On the Origin of ‘Western Philosophy’”. Digressions&Impressions. February 25, 2020. https://digressionsnimpressions.typepad.com/digressionsimpressions/2020/02/on-the-origin-of-western-philosophy.html

- Schuringa, Christoph. 2020. “On the very idea of ‘Western’ philosophy”. Medium. June 10, 2020. https://medium.com/science-and-philosophy/on-the-very-idea-of-western-philosophy-668c27b3677

- Shogimen, Takashi. “Dialogue, Eurocentrism, and Comparative Political Theory: A View from Cross-Cultural Intellectual History”. Journal of the History of Ideas 77, no. 2 (2016): 323–345.

- Soudien, Crain. “The Contribution of Radical Western Cape Intellectuals to an Indigenous Knowledge Project in South Africa”. Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 76 (2011): 44–66.

- Soudien, Crain. The Cape Radicals: Intellectual and Political Thought of the New Era Fellowship 1930s-1960s. Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2019.

- Soudien, Crain. “A re-Reading of Ben Kies’s “The Contribution of the Non European Peoples to World Civilisation””. Social Dynamics 48, no. 2 (2022): 191–206.

- Stevens, Kathryn. Between Greece and Babylonia: Hellenistic Intellectual History in Cross-Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. Connected History: Essays and Arguments. London: Verso, 2022.

- Werner, Michael, and Bénédicte Zimmermann. “Beyond Comparison: Histoire Croisée and the Challenge of Reflexivity”. History and Theory 45, no. 1 (2006): 30–50.

- Whitmarsh, Tim, and Stuart Thomson (Eds). The Romance Between Greece and the East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Whitmarsh, Tim. “Black Achilles”. Aeon. May 9, 2018. https://aeon.co/essays/when-homer-envisioned-achilles-did-he-see-a-black-man

- Wojciehowski, Hannah C. “East-West Swerves: Cārvāka Materialism and Akbar’s Religious Debates at Fatehpur Sikri”. Genre (Los Angeles, CA) 48, no. 2 (2015): 131–157.

- Zeller, Eduard. A History of Greek Philosophy. Vol. I. Trans. S.F. Alleyne. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1881 [1876].