ABSTRACT

In 1909 Alice Lucy Hodson’s memoir Letters from a Settlement was published. It is unique in providing an intimate first-hand account of what it meant to reside and (attempt) to settle in the women’s settlement Lady Margaret Hall in Lambeth, South London. This article considers how home was experienced, imagined, and represented by Hodson, who like many late-Victorian and Edwardian women were finding more opportunities and roles open to them at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Building on the work of geographers of home and translocal studies, I argue that Hodson’s fragmentary letter chapters show how her homemaking relied on several home imaginaries that included the settlement house, street, neighbourhood, her familial home, and Lady Margaret’s College. This was bound up with her middle-class status and wider imperial understandings of home. Yet, home making also relied on a process of home unmaking. This article will show how her fashioning of the self was dependent on how she narrativised her experiences of translocal homemaking and home unmaking.

Over 236 pages, the London-based philanthropist Alice Lucy Hodson charted the ups and downs of settlement life to readers of her Letters from a Settlement. Published in 1909, her chapter vignettes were initially sent as letters to an unnamed college friend. Hodson explained in her foreword that she was compelled to publish them to help answer the question, ‘What do you do at a settlement?’Footnote1 This article focuses on Hodson’s small book in order to discover how one woman was both at home and unsettled by her life at the single-sex, collective residency Lady Margaret Hall Settlement (LMHS). Hodson was one of the settlement’s first residents, joining in April 1897 and leaving in the summer of 1902. Located on Kennington Road in Lambeth, London, the settlement house was an extension of the kinship and friendship networks formed at the University of Oxford’s women’s college Lady Margaret Hall. It was founded in 1897 by the Bishop of Rochester with the support of Elizabeth Wordsworth, principle of the college, ‘to provide a centre for work in co-operation with parochial and other organisations in North Lambeth and Vauxhall’.Footnote2 During Hodson’s time at LMHS, she was an unpaid Charity Organisation Society (COS) worker, parish district visitor, boy’s club worker, choir mistress, Children’s Country Holiday Fund administrator, and the settlement house’s treasurer. Her five-year residency was remembered in the twenty-four chapters of her Letters from a Settlement. This letter memoir offers a unique glimpse of homemaking (and unmaking) within the settlement and the local community more widely.

Hodson provides an intimate first-hand account of what it meant for a middle-class woman to reside and (attempt to) settle in a largely working-class area. Public-facing settlement records tended to provide a short overview of settlers’ work, but do not recount their everyday, intimate experiences of settlement life. Likewise, settler autobiographies and biographies can frame settlement life beyond a home narrative. Historians need to move beyond a hagiographical approach to the settlement movement that draws on the voice of specific individuals who were either central to the foundation of the movement or subsequently played a key role in the creation of the twentieth-century social welfare state. Not every settler’s life ended up in such hallowed places. Hodson, like many settlement workers in this period, was not destined to be a ‘great woman’.Footnote3 Indeed when LMHS reflected on their history after the Second World War, Hodson was not listed as one of their ‘notable people’.Footnote4 On the surface, she appears to have led an insignificant life and, even with her privileged elite class status, she did not leave much of an impression beyond her letter memoir. Glimpses of her have been caught in digital newspapers records, but they reveal little of her life or views.Footnote5

Hodson is not a voiceless woman, nor is she straightforwardly absent from the historical record, but she has often been reduced to the sidelines of histories charting middle-class philanthropic engagement with urban working-class communities. Her letter memoir often appears in footnotes to support claims made by other more famous middle-class social investigators, for example in the work of Ellen Ross and Anna Davin.Footnote6 Elsewhere, David M. Burnham uses Hodson’s Letters from a Settlement to discuss the naivety and inexperience of female voluntary COS workers.Footnote7 Martha Vicinus situates Hodson’s work within the broader context of London’s female settlement houses, using the letter memoir to provide an occasional settler perspective on settlement life.Footnote8 Meanwhile, Seth Koven has used Hodson’s discussion of Lambeth dirt to affirm his claim that female social investigators were part of a wider project that eroticised the Victorian slum. Using Hodson’s phrase ‘go dirty’, he maintains that elite women were able to ‘flout bourgeois class and gender expectations’, while simultaneously bringing in bourgeois culture to reaffirm class difference.Footnote9 In doing so, he argues that Hodson ‘throw[s] social and sexual categories into disarray’.Footnote10

This special issue considers how cultures of home and domesticity were challenged in the modern period. Hodson’s letter memoir reveals the ways in which home was experienced, imagined, and represented by women who were finding more opportunities and roles open to them at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote11 This article proposes that Hodson’s Letters from a Settlement should be read as home life writing that articulates and moves the reader through a series of home spaces. These fragmentary letter chapters show that settling into LMHS, her Lambeth home, involved Hodson thinking through and engaging with various home settings and imaginings. Women’s and gender historians have long recognised that the ideology of separate spheres did not neatly map onto the lives of Victorian women.Footnote12 There is a tendency to contain female homemaking, especially where middle-class women are concerned, within the interior staging of the familial home.Footnote13 However, scholars are increasingly acknowledging that home was not exclusively confined to heteronormative domestic models that privileged the familial household.Footnote14 Rather, home and homemaking were connected to a wider world. As Alison Blunt and Ann Varley put it, ‘geographies of home traverse scales from the domestic to the global in both material and symbolic ways’.Footnote15

This article argues that Hodson’s sense of being at home was not confined to the bricks and mortar of the settlement house. She shows in her letters how her view of home extended beyond LMHS’s front and back doors. In doing so, she articulates what I describe as a form of translocal homemaking and home unmaking. Home unmaking is a term used by Richard Baxter and Katherine Brickell to explore the emotional, material, and psychological ways in which home can be undone. They argue that unmaking home can help people to achieve a sense of homeliness either within their current home or in a new one. Unmaking home is not always negative.Footnote16 An exploration of Hodson’s homemaking and home unmaking will therefore demonstrate the processes through which her home(s) was made, unmade, and made again. After all, home is not a fixed, natural entity and Hodson’s letter memoir offers a multi-scalar reading of home through her engagement with the homely/unhomely and comfort/discomfort. Moreover, it reinforces the argument that middle-class domestic space was not exclusively tied to the nuclear family and closed off from the wider world.Footnote17 In her letters, Hodson challenges a reading of the public sphere as standing in opposition to the domestic sphere because it is through her engagement with various homes (familial, educational, national-imperial) that she came to experience and conceptualise her place within the settlement home (LMHS) and local community (Lambeth).

Epistolary homemaking and home unmaking

Hodson’s Letters from a Settlement should be understood as a form of epistolary homemaking. This was done in two stages: firstly, in the moment when she wrote the letters, and secondly, when she subsequently edited them to have them published in book form. Many of the conventional markers of a letter were edited out, including the date, address, salutation, and closing. Hodson did retain her personal opening and closing remarks, which often conveyed the sentiment ‘I am so sorry not to have written before, but I have been very busy.’Footnote18 Another letter closes with the observation that it is past midnight, and she needs to sign off, implying that settlement life made it difficult to retain the much-needed links she desired, and she acknowledges that she ‘loves’ receiving the letters that her unnamed friend sends her. In initially sending these letters, Hodson was connecting herself to a home space beyond Lambeth. Indeed, her letters can be conceived as a way of returning to her college home in Oxford, a place that she evokes as being one of quiet repose and studious activity.Footnote19 Even though the recipient of Hodson’s initial letters is unknown, comments left in the chapters imply that they were written to a female friend at Lady Margaret Hall, who was still engaged in her studies. Similarly, there is a suggestion that this female friend resided temporarily at LMHS during the summer vacation, with plans of becoming a settler herself. Hodson also mentions having written letters to her mother in Wolverhampton. Perhaps, some of these chapters are drawn from the ‘long letter[s]’ that she sent home.Footnote20

Hodson’s letter memoir produced another, more public form of homemaking, in that it was a public remembering of belonging to LMHS. The writing itself was thus a form of homemaking. Because we do not have access to the original letters that formed the basis of Letters from a Settlement, we cannot be sure if Hodson chose to retain letters written during her time at LMHS or whether she wrote new text, in the form of letters, specifically for the purpose of the book. The letters that make up the memoir were perhaps not sent as individual letters but may have been edited or stitched together from several original letters, and details in original letters may have been subsequently expanded. Without the original letters, we cannot be sure of the emotional scripts that may have been teased out onto the page by crossings out and other stylistic clues. Yet the fact that Hodson chose the letter as the narrative form for her published telling of settlement homemaking and home unmaking shows that she found composure in this genre and sharing her correspondence. As Penny Summerfield argues: ‘[C]omposure indicates the dual process of composing a story about a life and achieving personal composure or psychic equilibrium in so doing.’Footnote21 Hodson evidently did not want to write within the genres of the social scientific investigation or journalistic slum writing.Footnote22

Hodson was at home within her letters. There are several reasons why this may have been the case. Firstly, she developed a ‘writing I’, to use Liz Stanley’s term, that helped her to reaffirm her central place in the narrative.Footnote23 She was not a simple eyewitness, but a participant who was able to use letters to make home and express moments of home unmaking in the everyday, translocal dynamics of the settlement. As Stanley has shown, women in this period struggled to create an ‘auto/biographical I’ within more traditional forms of life writing.Footnote24 Letter-writing has often been understood to be a part of women’s literary practice.Footnote25 Thus, Hodson’s familiarity with this genre would have helped her to express her subjectivity and agency. Secondly, and linked to the previous point, Hodson chose the letter genre as a ‘strategy of self-actualisation’.Footnote26 She was able to use these letters as a self-fashioning process; they became tools to perform and play out her identity as a translocal settler. This article will show how her fashioning of the self was dependent on how she narrativised her experiences of translocal homemaking and home unmaking. At the same time, Hodson’s selfhood was contained within the memoir. Her letters captured a specific moment in her life; the memoir did not force her to reflect on her experiences with hindsight or provide readers with a discussion of her life before or after taking up residency in Lambeth. Finally, as I have noted above, her letters had an intended audience. In response to the ‘writing I’, Stanley has argued that letters have a ‘reading I’.Footnote27 Hodson would have known that her letters were read or shared more widely than the intended receiver.Footnote28 She must have therefore already have created a sense of composure in sharing her letters more widely and to a public middle-class audience. For Hodson, either the intended audience of her letter memoirs was the same as the recipients of the original letters or she was able to write more clearly to this audience if she imagined them to be someone who was receiving her chapter as letters. Within the context of Letters of a Settlement, she was able to use the letter voice to pull the ‘reader I’ into the chapters.

Nevertheless, Hodson’s homemaking relied on editorial practices that unmade place. Readers with no connection to Hodson or LMHS are homeless readers, even with the accompanying photographs, because they never know where they are. The settlement and places of her work are nameless, and the effect is therefore to make some readers more intimately connected with her home narrative than others. The only clue that Hodson gives to her LMHS connection is in her preface, where she expresses her ‘indebtedness’ and ‘gratitude’ to Dorothy Kempe, the then head of LMHS, for her encouragement to publish her letter memoir.Footnote29 This suggests that this type of homemaking was initially supported by members of the settlement. Yet, if, as seems likely, she had thought that this would cement her place in the corporate memory of LMHS then she would have been disappointed. The settlement did not publicly embrace the letter memoir and there was no mention of Letters from a Settlement in its 1909–1910 annual report. Instead, Kempe ‘at the request of the council’ was asked to write a three-page article on ‘Personal Work’ that year. This article strikes a different tone from Hodson’s narrative of class difference and alienation. A pivotal theme in Kempe’s short piece was LMHS’s commitment to winning ‘allies amongst the people’ in order that they might declare that ‘we are friends’.Footnote30 Unlike Hodson’s letter memoir, the language of cross-class friendship plays a central part in Kempe’s account of settling.Footnote31 As the final section will show, Hodson’s tone and discussion of Lambeth and her working-class neighbourhoods reinforced a wilderness narrative. Her ‘reading I’ was never going to be her working-class friends.

When Kempe wrote her piece in 1909–1910, Letters from a Settlement had been reviewed by several publications. Critics complained that it was ‘trite if not trifling’.Footnote32 A review in the Westminster Gazette not only found the letter memoir to be poorly written, but also argued that it revealed Hodson to be naïve in her settlement work. The critic concluded that a copy of Hodson’s book should be given to every women’s college for the express purpose of making undergraduates reflect with caution on whether they really should get involved in settlement work.Footnote33 A review published in the Charity Organisation Review was also critical of Hodson, for revealing the more intimate aspects of the settlement household. Written by ‘M.M.’ (Margaret McMillian, the influential campaigner for the rights of children), it confessed that the reviewer was disappointed by the ‘frankness with which the domestic economy of the settlement is discussed’. She noted that Hodson had ‘failed to grasp the Settlement ideal’ and made the settlement sound like a ‘boarding house’. Worse still, Hodson had broken the sacred covenant between residents to reveal the domestic underpinnings of the settlement to all. This led McMillian to conclude that ‘we think it would appear unseemly that the life of their House should thus be given forth in print “for all the world to see”’.Footnote34 In publishing the intimate details of the settlement, Hodson had exposed the private world of settling. The middle-class female settlement house was not to be exposed in this way. Yet her decision to reflect on the domestic economy of settlement life provides scholars with a glimpse of a sphere often denied to us. In addition, it allows us to explore how Hodson made herself at home in the settlement. Her translocal homemaking and home unmaking was multi-scalar, drawing on the settlement household, the garden, the working-class home, Oxford, Tettenhall in Wolverhampton, and British imperialism.

Translocal homemaking

Hodson’s homes were framed within a translocal mindset. The concept of ‘translocalism’ has been developed by human geographers and anthropologists interested in exploring how locality fits within the nation-state and global arenas. They argue that scholars need to consider the multi-scalar nature of the local that enables local subjects to move within and beyond the local–local, local–nation, and local–global axes. For instance, Brickell and Ayona Datta have argued that translocal places include homes, streets, neighbourhoods, and rural, urban, regional, national, and imagined settings.Footnote35 The study of the translocal has been dominated by explorations of the experience of global migrants within their new local spaces. In the nineteenth century, internal and external migration was a distinct urban pattern; and it occurred at a time when ordinary people were more likely to see themselves through their local identity.Footnote36 While urban migration in the United Kingdom can be linked to specific national groups, such as the Irish, and to class groups, such as rural labourers, more needs to be done to consider the movement of social elites with the UK during this period. I argue here that a consideration of translocal mobility provides scholars with a conceptual lens to understand emergent forms of middle-class social action in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Settling was a translocal activity. It privileged the idea that socially concerned middle-class individuals should reside in specific working-class neighbourhoods to overcome the geographical separation of rich and poor caused by the Victorian processes of industrialisation and urbanisation. At its most basic level, settling involved bringing non-locals into a neighbourhood with which they were unlikely to have a physical or emotional connection. Conceiving the settlement within a translocal framework enables us to reconsider how place was experienced by settlers. Translocal actors create physical and imagined local corridors as they move between places and tie them together. Local, place-based, subjectivity is therefore not limited to the place where someone resides, but rather to the places that people have a personal, social, or historical connection with. According to Suzanne Hall and Ayona Datta, translocal mobility invites people to:

engage with difference and change [that] requires an ability to live with more than one sense of a local or familiar place—a “here” as well as a “there”, and a “then” as well as a “now”—and an ability to live amongst different people.Footnote37

The settlement movement placed significant emphasis on dwelling in an assigned residential dwelling known as a settlement house. Settling should therefore be conceived as also being a domestic activity: settler placemaking required a process of homemaking. According to John Tomaney, the sense of feeling at home and belonging is central to the development of translocal subjectivities associated with ‘attachment, loyalty, solidarity and sense of affinity’.Footnote38 Homemaking does not have to be tied to the immediate act of house dwelling. It can be experienced both figuratively and literally. Hodson describes a process of settlement homemaking that drew on the settlement house as well as other home spaces. According to Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling ‘home is both a place/physical location and a set of feelings’; ‘imaginaries of home occur in and construct other scales’.Footnote39 Hodson’s experience of home was translocal: her descriptions move from the room to the house, the garden, or the street, to working-class domestic spaces, to her family home, to Oxford, to the countryside, and to Britain. All of this was conceived with an imperial bent that framed settling as a therapeutic practice of residing that would, firstly, reconnect rich and poor and, secondly, transform the metropolitan wilderness into something more ‘civilised’. Hodson’s translocal homemaking therefore interwove several scales, and she relied on overlapping and interlinking home spaces when making herself at home.

The settlement house was Hodson’s most personal and intimate home space for the duration of her time in the settlement movement. It was the place where she slept, rested, and boarded. LMHS was also a single-sex collective residential dwelling. Its main purpose was to provide female settlers with a room of their own, to help them undertake social work in a specific neighbourhood. As a home space, it was active and purposeful. As Hodson explained:

the main idea of this place is that a number of ladies, who are more or less congenial to one another, should live together, partly as students, partly as workers, with the general intention of doing something to check obvious abuses, and of helping those who are in need of assistance.Footnote40

Hodson’s first year of study at Lady Margaret Hall was disrupted by the death of her father, William, in May 1890.Footnote43 This event most likely strengthened her emotional connection to the college. The establishment of the LMHS in 1897, a year after she left the college, provided Hodson with an additional, transitional home space after quitting her student home in Oxford. Her attachment to the LMHS project saw her collect subscriptions as the settlement’s treasurer before it had even opened. These funds were sent to her at mother’s new house, The Grove, Tettenhall, Wolverhampton.Footnote44 (The death of her father had seen her brother inheriting their family home, Crompton Hall, in the same village.)

Despite striking out independently after university, Hodson was still dependent on maintaining a connection to her family in the process of her settlement homemaking. She initially decided that she needed the consent of her parents to live at the LMHS, writing that ‘I should never have decided to come here against the wishes of every one [sic]; it would have made me miserable.’ She notes that, while her ‘father’ was initially ‘alarmed by the idea of a settlement’, he was ‘broad-minded and tolerant’ enough to give his permission. He even offered to cover her board and give her a small allowance. Although her mother was sad that Hodson was not staying at home after Oxford, she ‘was quite pleased that I should be independent’. Her mother even went as far as to state that she ‘would have loved such a life’ but she had instead married her ‘handsome husband’. Hodson’s father had in fact died seven years before she decided to live in Lambeth at LMHS. It is likely that her brother, Lawrence, was the one to offer his blessing and financial support, and that he was described as Hodson’s father in her memoirs because of the paternal role he played in her life. This role extended to showing that settlement life did not unmake single women’s connection to their families. As Hodson was quick to point out, ‘I do not mean to say “good-bye” to my home at all; I shall have the ordinary holidays three times a year, and an occasional Saturday to Monday; this is quite possible, for there are generally some short-time workers.’Footnote45 Thus, a translocal reading of home spaces is necessary to understand Hodson’s self-fashioning after her university years: she still considered her mother’s Wolverhampton house to be ‘my home’, but she was moving on.

Settlements were therefore not necessarily seen as the anthesis of familial domesticity. Hodson’s letter memoir illustrates the ways in which home space was imagined across the familial home, college rooms, and the settlement, interweaving family and non-family households. Her home imaginaries incorporated both her family home and her settlement home because each functioned for her in different ways. This was quite typical of how settlers thought of their identities. LMHS was an urban work-home space for Hodson, whereas her Wolverhampton home became a space of true relaxation because of its country air and greenery. It was when she was away from the settlement house that she was able to recover and be remade for settlement living.

For women like Hodson, reverting to family life might not have been their preferred option after university. College life had showed them the benefits of corporate living and a strong, supportive female leader. Settlement living continued this. Edith Langridge was the Head of LMHS; Hodson describes her as the ‘Head Gardener’. Hodson’s choice of language implied that Langridge was planting settlers into a wilderness and, more importantly, helping them to grow. It was ‘the head gardener that keeps us all alive, and adds a touch of colour here, a bit of comfort there, just to keep us going when the days are cold and dark, and tempers are short’.Footnote46 Langridge was pivotal to the household, according to Hodson, as was especially noticeable when she left LMHS for her annual visit to Italy.Footnote47 LMHS residents were not encouraged to undertake the household management of the settlement in Langridge’s absence. The results, in Hodson’s account, led to oversights and a lack of good or sufficient food. Feeling at home can be tied to the stomach, and this is certainly emphasised in Hodson’s account of LMHS: ‘we are really looked after, I may tell you that in addition to breakfast, lunch, dinner, and tea we have hot cocoa and biscuits last thing at night’.Footnote48 The cocoa was a welcome domestic ritual for her because after walking Lambeth’s cold streets late at night she needed to be ‘warmed and fed’.Footnote49

In this collective residential space, female settlers were encouraged to be unselfish. Hodson’s account of a fellow settler stealing all of the house’s hot water shows that the comfort of the settlement depended on people being aware of others. Such misdemeanours brought the household together in a united front to make sure the hot-water fiend was always the last person in the bathroom. Similarly, Hodson noted that, if a settler stayed up late and then asked for breakfast in bed, Langridge would carry the tray up herself. This unsettling of household roles was enough to prevent anyone from asking for this service again.Footnote50 Consequently, middle-class LMHS settlers were engaged in forms of homemaking that involved considering others. Personal comfort needed to be rethought in a collective setting. One of the reasons this needed to be considered was to prevent household costs becoming unreasonable. Settlement houses needed to be self-sufficient and subscriptions were not to be used to offset daily household expenses. Domestic servants and local charwomen were one of LMHS’s largest expenses. Making the settlement homely required the labour of domestic servants and local charwomen so that, as Laura Schwartz has shown, enabled socially concerned middle-class women could conduct their public-facing work without the worries or concerns of running their households.Footnote51 The comfort of the house, and therefore residents, was thus achieved by the labour of a group of women who came from the social group the settlement was supposedly assisting outside. This also shows that homemaking for female settlers moved beyond the practicalities of running a household.

Homemaking through the garden

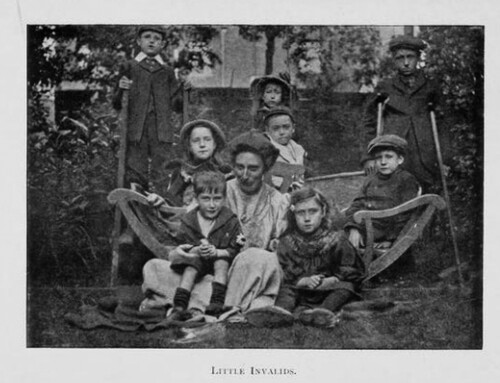

In this section, I will turn to one letter chapter that discusses the settlement garden to explore one of Hodson’s settlement homemaking practices in more detail. The garden was a unique space in having its own dedicated chapter; and the only photographs included in the book that captured settlement spaces were of the garden (see and ). Chapter 22, ‘The Settlement Garden’, discussed the planting and use of the garden, or ‘our “little Park”’, as LMHS residents described it.Footnote52 Hodson wrote this chapter to thank an unknown recipient for sending the house a ‘lovely hamper of herbaceous roots’.Footnote53 Her engagement with this residential green space was a form of homemaking that offset her unhomely experiences of the settlement house and wider community. For her, the settlement garden was a place of attachment and possession, especially when compared to how she framed other settlement rooms in home imaginings. Urban residential gardens are often overlooked as part of the immediate home space.Footnote54 This section will show how the settlement garden was a part of Hodson’s homemaking and central to her expression of home. Here she drew on an English mindset that viewed the domestic garden not as a separate place, but as one that was connected and bound up with the domestic home.Footnote55

Figure 1. ‘The Pride of the Garden’, in Alice Lucy Hodson, Letters from a Settlement (London: Edward Arnold, 1909), facing 236.

Figure 2. ‘Little Invalids’, in Alice Lucy Hodson, Letters from a Settlement (London: Edward Arnold, 1909), facing 244.

Hodson starts her chapter with a description of the settlement garden in its early years. She writes that ‘When the Settlement first took possession here the gardens were a little pathetic.’Footnote56 The grass had an unhealthy appearance and was patchy. The pear tree needed care, and the shrubs pruning. The whole place was untidy and unruly. The garden was overrun with snails.Footnote57 The chapter charts the coming together of this green space. Using Mass Observation surveys and life writings, Mark Bhatti, Andrew Church, and Amanda Claremount have noted that gardening should be understood to be a form of homemaking. As such, they propose that domestic gardens should not be understood simply as landscapes but as a ‘taskscape’ that ‘can at times be a source of inventiveness, emotionality and comfort; a poetic creativity that gives meaning and purpose to everyday life’.Footnote58 For Hodson, the garden became a site of individual and collective homemaking. As the previous section noted, LMHS’s female residents were not usually involved in settlement housekeeping. In contrast, the garden was a home space where residents were able to come together to maintain and cultivate it. ‘In the summer’, Hodson writes, ‘watering alone was a big job; but fortunately, it was so fascinating to see the obvious delight of the flowers and grass, after a long day, with their refreshing bath, that everyone was willing to lend a hand’.Footnote59

Hodson acknowledged that the garden was a space of both ‘joy’ and ‘toilsomeness’. Yet, even with its hard and time-consuming labour, ‘the beauty and health-giving delight’ of the garden was worth the effort.Footnote60 Rebecca Preston has argued that, in the nineteenth century, gardening ‘was increasingly promoted as a healthy and useful activity for women’.Footnote61 If respite appears anywhere in Hodson’s letter memoir, then it is when she pauses to take her reader on a constitutional around the garden. The garden became her refuge from the world outside. Halfway through the chapter she poses the question ‘Do we use the garden?’ To this she replies:

All the year round, but especially, of course, in the spring and summer. What, indeed, should we do on those hot dusty days, when the sun beats down on road and houses and on our poor selves, and we come in after a long day, tired and footsore. Why, the very sight of tea in the garden revives us; there we sit in those comfortable deck-chairs, with the kettle boiling away in a corner, and in no time we are rested and cheered, and quite ready to start on another round. Then, again, we can do all our writing so much better under a tree in the garden; we can sew and read too, and even think far more comfortably out-of-doors than in the hot rooms.Footnote62

The garden was a space of enchantment for Hodson and other LMHS residents, a pull that was felt even when indoors. Far from separating the house from the garden, windows at the back of the house helped frame and bring the garden inside. Judith W. Page and Elise L. Smith have argued that ‘entry points’ like doors and windows are ‘membranes that allow home and garden to flow together’.Footnote63 According to Hodson, indoor and outdoor domestic space worked together to create a boundary around her settlement home:

for the house itself the garden does wonders, for not only does it keep the back rooms quiet and cool, holding far away the discords of the slums, but it gives to those who sit by the windows quite a large stretch of sky to lighten them, green trees and grass to rest them, and bright colour to cheer them; till at last they are tempted to come down and walk in the midst of the delights that are spread out before them.Footnote64

The settlement’s green spaces were not straightforwardly private, domestic spaces. As shows, beyond the wall, houses bordered and looked onto the garden. For Hodson, then, the settlement garden played a wider, more public, curative role. In the front garden, she noted that:

the blue cornflowers and cheery marigolds, which are often to be seen in the beds in front of the house, give it an air of distinction; and, it may be, bring dreams of the country to the poor things who sometimes linger outside the palings.Footnote65

This is further supported by Hodson’s inclusion of a back garden photograph of a group of disabled children with a female settler, possibly Hodson herself. However, this picture was not inserted in the garden chapter, but rather in the following chapter on ‘Little Invalids and Parochial Relief’.Footnote67 Hodson’s selection of this photograph speaks to the significance of her and the settlement’s work with disabled children. Within the context of the chapter, it is the people she wants to show to her readership. Nevertheless, the garden stages this picture, confirming Preston’s argument that the back garden was not only a practical space to take a photograph in this period but also that these images signified the importance of the garden to the household.Footnote68

It is noteworthy that no photograph of the settlement house is included in Hodson’s memoir. In many ways, the garden in and appears as an anonymous space. Interior shots of the settlement might have given the settlement away to a knowledgeable audience.Footnote69 Of course, there might have been practical reasons why the garden was photographed instead of interior spaces, as it was light and therefore easier to photograph. Even though the ‘Little Invalids and Parochial Relief’ letter chapter outlined the winter programme of work with disabled children, the clothing and the leaves on the trees suggest this photograph was taken in late spring or summer.Footnote70 A well-lit photograph was especially important when the cost of a film was still quite high for a female settler concerned with budgeting.Footnote71 The garden might also have provided more space, ease, and comfort for the sitters; a disabled child stands on stilts, another leans on crutches, while other children sit in a rocking chair. This enables the photographer to stand away from them. Yet, photographs do more than capture a moment, especially when they have been staged and selected for wider publication.Footnote72 The value Hodson inscribed to both these images was their ability to further trace her emotional attachment towards the garden. Her sense of being at home was captured through the ‘pride’ in recording the settlement’s well-grown lilies and her work with the children. If her likeness is captured as the female settler in , then she is permanently traced back into the settlement garden.

Garden homemaking also pulled in external audiences. As already mentioned, this letter chapter was initially written to thank an unnamed recipient for sending plant roots to Hodson and the settlement. Flowers and plants sent by kinship networks helped settlers to cultivate and maintain relationships. LMHS’s annual reports show that Hodson’s mother and brother both sent floral gifts to the settlement.Footnote73 Far from removing Hodson from her family, we can see that the settlement garden entwinned and connected settlers like Hodson to home spaces from which they were physically. This is an example of how settlers made home places into translocal sites through the movement of plants. Hence gifts of plants and flowers were able to heighten Hodson’s attachment to the garden because of the personal connection she was able to maintain while cultivating the garden. By this means, settlement spaces—far from removing elite middle-class settlers from their families and family homes—were able to link and tie them together.

The settlement garden was also a home space to which Hodson returned when she had left LMHS in 1902. The following year she gave the ‘most beautiful garden tools’ to the settlement. These were prizes for children who had that year been given small plots to plant and sow in.Footnote74 On 28 June 1918, Hodson attended LMHS’s twenty-first birthday party, where she gave a ‘happy and graceful speech’. She then presented the settlement house with a gift of £350 that she had collected from settlement supporters and local community members.Footnote75 This money was used to build an architect-designed hut for hosting working-class guests and to provide covered outside space for disabled children. By 1920 when the hut opened, the council was able to declare its gratitude to Hodson and the donors. Hodson’s brother, Lawrence, wrote out the names of the donors in a little book for the settlement.Footnote76

Hodson’s attachment to plants and flowers also reveals a flaw in settling. In her final chapter, she acknowledges that she was mentally and physically broken by the work of settling. Simply put, she was exhausted after five years of settlement work. In this letter, she also explained her realisation that her act of settling in south London was not really for the poor, but for herself. She recognised what she could not have when she first arrived: that settlement work cultivated the minds and characters of the middle-class settlers as much as their working-class neighbours. She had originally thought ‘the effect of our united doings would be that the wilderness would blossom like the rose, and the poor and needy would rejoice at our coming’.Footnote77 Read against the gardening chapter, we see that Hodson’s metaphorical roses failed to flower. Her attempt to cultivate working-class districts was a slog that never bloomed, unlike the settlement garden. Rather, it remained a ‘wilderness’. In contrast, turning to the settlement garden enabled her to see her hard work paid off by the yearly planting, growth, and blossoming.

Translocal home unmaking

Hodson’s Letters from a Settlement provides a home narrative that enables us to understand how female settlers made themselves at home in new urban home environments. However, this did not stop translocal homemaking being unsettling. Hodson’s letter memoir shows that she struggled to feel a sense of belonging in Lambeth, and she therefore provides an illustrative example of translocal home unmaking. Baxter and Brickell define home unmaking as ‘the precarious process by which material and/or imaginary components of home are unintentionally or deliberately, temporary or permanently, divested, damaged or even destroyed’.Footnote78 They have argued that the process of home unmaking needs greater consideration if scholars are to understand the ways in which people’s home biographies are made. Baxter and Brickell argue that there are four stages to home unmaking; firstly, ‘home unmaking is part of the lifecourse of all homes and is experienced by all home dwellers at some point in their house biographies’. Secondly, homemaking and home unmaking are not separate processes; rather they can occur together. Thirdly, home unmaking can be ‘liberating and empowering’, especially when it is linked to the ‘recovery and making of home’. Finally, home unmaking reminds us that being at home is never a completed process. Each of these home unmaking stages can be read into Hodson’s letter memoir.Footnote79

Letters from a Settlement reveals that homemaking and home unmaking are interconnected with one another. Hodson’s home unmaking did not simply occur once she had decided to leave LMHS. Rather, feelings of not being at home in either the settlement or the Lambeth and Vauxhall community are reflected upon throughout. Hodson’s home unmaking occurred within the settlement house. From the beginning, she describes as disruptive the noise of trams and market carts that invade her bedroom day and night. Although she appears to have moved to a bedroom overlooking the garden, she struggled with how much she needed to do as time went on. From the beginning she found settling ‘really very trying’, but the narration of fatigue gains pace through the memoir, to the final letter, where she notes that she needs to go home for a long holiday.Footnote80 Fatigue clearly placed strain on the LMHS household. According to Hodson, settlers were likely to suffer from ‘bad-tempered or disappointed nerves, dyspeptic or even hysterical nerves—though the latter are fortunately rare—and lastly, and very generally, tired and highly strung nerves’.Footnote81 Apparently, everyone at some point would become disappointed and depressed. When this happened, the house would rally around the afflicted settler with tonics and pills or encourage them to go away to help them recover. Home unmaking can, by this means, sometimes have the effect of making a household.

Even the rhythms of the settlement house did not always provide her with the space for relaxation that she craved. Dining at LMHS at lunchtime, rather than providing much-needed sustenance, could feel rushed and make the settlement feel like a hotel. This was not always helped by the decision to let outsiders dine at the settlement. LMHS opened the doors to non-resident charity workers because there was a feeling that there were no good places to eat in Lambeth (itself an assumption that Lambeth was not a home space). While Hodson felt that letting paying guests dine in the settlement was ‘amusing and interesting’, it could be ‘a little tiring’ if you were in need of relaxation and a break from the world outside.Footnote82 As good hosts they had to talk to and entertain their guests, no matter how tired they were. This was probably not helped by the decision that all guests, even if late, were to be offered the best food option, leaving the settlers sometimes having to go with ‘bread and cheese’.Footnote83

Hodson’s letter memoir suggests that settling was never going to be a long-term option for her. Arjun Appadurai argues that locality is inscribed onto the body.Footnote84 Lambeth was not positively inscribed onto Hodson’s body. Rather, her home unmaking was repeatedly conveyed by the embodied discomfort she felt towards working-class courts and streets. She did this not only by referring to the exhaustion she experienced from settling, but also through sensory unfamiliarity. It was ultimately through her body that Hodson came to experience a sense of unbelonging in and foreignness to Lambeth. In contrast to LMHS, the working-class homes she visited continually enabled her to reaffirm her home-unmade narrative. Like many other social investigators in this period, she emphasised the unravelling of working-class domesticity.Footnote85 Her memoir confirms Ruth Livesey argument that middle-class female domestic visitors read for character in the working-class domestic interior.Footnote86 Hodson joined a group of COS workers who found these homes wanting, acknowledging that ‘I did not feel at all comfortable’ in one home because of ‘the dirt!’ and its general untidiness. The sofa-cum-bed was covered in dirty sheets, food was left out, and ‘Dinner plates, knives, forks, and spoons were piled up in a hopeless mess on a corner of this maid-of-all-work sort of table.’Footnote87 On leaving the house, Hodson remarked ‘How could the family be decent in such surroundings, and could any decent person get a place into such a mess?’Footnote88 She reflected that she was depressed because ‘it seemed hopeless to visit these people and not offer to help them to clean up a little’.Footnote89

Hodson’s desire to clean up was further expressed on Lambeth’s dirty streets, where she envisaged herself walking ‘about with a sponge, a can of water, and towel hung round the waist’, cleaning away the ‘dust, fog and smuts’.Footnote90 Such envisioned cleaning turned Hodson into a social housekeeper, which in turn reaffirmed her household manager identity. Settling had the potential to undercut her legitimate womanly identity, yet, as Shannon Jackson has pointed out, when ‘a female settler tried to rationalise her life choices, she borrowed from the language of Victorian ideals, reworking rather than dismissing the association of femininity with domesticity, morality and virtue’.Footnote91 Settling therefore extended women’s domestic roles into new home spaces. The problem for Hodson was that she struggled to find composure in this collective housewifery. She was unable to break down class barriers or dismantle her class prejudices to be able to understand working-class housewives or homes.

Lambeth’s working-class homes and streets are not just dirty in Hodson’s account, but also smelly. She reported that crowded houses smelt of human clothing, bodies, and questionable cooking. On the street, she discussed fried fish and chip shops. Turning tourist guide, she leads her reader to a shop window, where she notes the heaped piles of whiting, plaice, flounders, and sometimes mackerel. At night they do a roaring trade, especially around 10.00–10.30.Footnote92 This disrupted the homeliness of the city for middle-class women because it departed from normal dinner-time routines.Footnote93 Hodson’s outsider status was not only confirmed by her obsession with the smell; her memoir also reveals a fascination with ‘a bottle which is shaken violently over each piece of fish, after it is purchased’, which she subsequently describes as a vinegar bottle. There was nevertheless a sense that Hodson’s sensory experiences were diminishing over time. She concluded:

I am getting a little bit used to the dirt and the smells, but on the whole it is a mistake to have a sensitive nose, or in fact any sensitive organ. If only one could temporarily shut off one’s senses, what a relief it would be.

Hodson’s sensory home unmaking led her to become unsettled in her nation’s capital city. Unlike settlers and missionaries in the colonies, she was more likely to share her British national identity with her working-class neighbours. She was even a Londoner, having been born in Spitalfields.Footnote95 However, national citizenship can play a secondary role in the framing of place identities.Footnote96 Hodson’s unhomeliness occurred because her middle-class status prevented her from sharing her neighbours’ sense of placemaking. She relied on a wider imperial settler imaginary that conceived the local spaces as a wilderness. Unlike the settlement garden discussed above, she understood working-class outdoor domestic space to be problematic. Turning to the courts, she revealed that her domestic floriculture was gendered, classed, and racialised.

According to Anna M. Lawrence, middle-class women were central to the development of a moral botany that emphasised the civilising potentials of flowers. The caring and maintenance of flowers were thought to teach good habits and create better habitats.Footnote97 While there is no evidence that Hodson, as either a COS officer or a district visitor, actively promoted the cultivation of flowers amongst court dwellers, she does frame her understanding of domestic courts within a moral botany framework. She nostalgically observed in her chapter on ‘Some Friends’ that, in ‘prosperous days, the gardens had not yet been paved and made into yards, but were bright with flowers’.Footnote98 For her and her ‘favourite old couple’, who provide her with this information, the lack of flowers served to visually reinforce the sense that the area had degenerated.Footnote99 Her letter memoir shows that she was not able to transform the courts she worked in, even if she could cultivate the settlement garden. Reading this anecdote with the garden chapter demonstrates how her settling was co-opted to be a part of a wider imperial domestic mission. Therefore, by extending Lawrence’s discussion of floriculture, we can see how Hodson, through her discussion of the settlement garden, implied the domestic barbarism of the working class in Lambeth and Vauxhall because of their lack of domestic green spaces. As domestic spaces, the settlement garden and working-class yard reinforced class difference by establishing what Lawrence has described as a ‘hierarchy in levels of civility’.Footnote100 Hence Hodson was enabled to make a home by unmaking the homes of the working class.

Settling implied that there would be a transfer of middle-class behaviours and attitudes to the working class. Hodson’s social and national privileges prevented her from thinking that she needed to reframe her sense of belonging. Homes are an extension of people’s identity. Living in a settlement house was a public declaration to transform and improve working-class neighbourhoods and homes. As noted above, Hodson’s memoir shows that she felt that her working-class neighbours were in need of reform. Consequently, she was always forced to connect or draw on other home spaces to create a sense of non-residential home belonging. This explains the draw of Lady Margaret Hall and her family. Conversely, she reports that Lambeth is not like the West End where there are ‘fascinating shops and carriages to look at’.Footnote101 Settlers like Hodson worked within their local communities, but becoming a local subject was always going to be a challenge for them. They needed to be open to their neighbourhood’s home spaces but there were always ties to other home spaces and imaginaries that helped them to reinforce their class identity and homemaking.

Nevertheless, Hodson’s letter memoir indicates that the local could be inhabited by several social groups who had differing home visions. Female settlers were more likely to reside in settlement houses as professional agents working for organisations that often reinforced that social standing. Similarly, LMHS was a new organisation in Lambeth when Hodson arrived as a settler. Working-class residents probably did not see it as a local organisation rooted in the community. Hodson’s memoir therefore shows that the settlement house gave settlers a home and an affiliation, but it did not necessarily extend personal belonging and attachment into the wider community. This was compounded by Hodson’s roles, which made it difficult for her to build reciprocal relationships with local people in the court districts she visited and worked with. She never went into these spaces as an equal nor as someone able to negotiate neighbourly relations. Leaders of the settlement movement might have been keen to frame their work within the rhetoric of neighbourliness, but the increasing professionalisation of female settlers made this impossible. Hodson acknowledged that she did not follow the class script that local working-class people wanted from her. She did not readily give alms. Her ‘business-like appearance’, made up of washable items and short walking skirts, was not appreciated by working-class court dwellers, unlike the West End ladies who visited in ‘pretty frocks and feathered hats’.Footnote102 Even, Hodson’s working-class neighbours made it impossible for her to belong.

Conclusion

LMHS was only one of Hodson’s many homes during her life. Official records show that she lived between London and Wolverhampton, before settling down in Oxford. In 1911, living off ‘private means’, the 41-year-old Hodson cohabited with her 72-year-old mother, Helen, and two domestic servants in London’s affluent Marylebone.Footnote103 Helen died in July 1920 in Wolverhampton.Footnote104 It is not clear whether Alice returned to Oxford after her mother died or if she was already living there. The 1921 census reveals her, at the age of 52, visiting a Wiltshire vicarage as a ‘Science Student’.Footnote105 Eighteen years later, the 1939 Register listed her living at 98b Banbury Road, Oxford. During the Second World War, she was an air raid warden, a role that she carried out throughout her early 70s.Footnote106 After the war, she continued to live in Oxford. In her obituary of Hodson, Christine Anson, the niece of Edith Langridge, the first Head of LMHS, listed a range of activities Hodson engaged in once she left LMHS.Footnote107 She taught at Morley College, worked on the Education Committee of the County Council in Wolverhampton, and became treasurer of Birmingham’s Women’s Hostel. Nevertheless, her longest home attachment was to Lady Margaret Hall. Students and alumni appear to have fostered a close relationship with her. Anson visited her in her Oxford nursing home or met up with her for lunch. Anson noted that Hodson was ‘always witty and gay and always giving a helping hand’. She also remembered Hodson to ‘be the most lively and amusing companion, a botanist, an artist, and one who saw fun and interest in many things’.Footnote108 These attributes are missing from the letter memoir, perhaps because Hodson struggled so much with settlement work. When she died, in 1963, at the age of 94, Hodson left the college library ‘beautifully illustrated botanical volumes’.Footnote109 She also left an estate of £86,420 (representing purchasing power of £1,850.668.30 in today’s money).Footnote110

This article has argued that settling should be understood as a form of translocal homemaking. Choosing to become a settler was a commitment to dwell somewhere unfamiliar. Moving to working-class urban areas involved creating a sense of homeliness both within the settlement house and within other home spaces in a wider local community. For many women at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, settling challenged conventional ideas about where they should reside. Hodson’s letter memoir provides a unique opportunity to understand, firstly, the agency of one such woman and, secondly, experiences of home life from the point of view of a female settler. Within the LMHS annual report Hodson was always listed as ‘Miss A. L. Hodson’. Her letter memoir therefore provides us with the means to recover a personal home narrative that comes from within the settlement house and extends outwards. The presence of her letter memoir is also a reminder that there are many female (and male) settlers whose voices can no longer be heard.

Moreover, Hodson’s letter memoir does not just show how women extended their domestic roles to became unchallenged angels of the state. Rather it shows that settlers’ attempts to make themselves at home contested conventional ideas of domesticity and home life. Hodson was able to reside in a collective household that relied on her previous home (Lady Margaret Hall), while actively dismantling the private and public spheres. This article has shown that her translocal homemaking was multi-scalar. It pulled together the spaces of house, garden, street, working-class homes, metropole, and empire. Historians need to do more to uncover the homes that our historical actors inhabited and how they were simultaneously made and unmade. As Hodson shows in her letters, translocal homemaking relied on imaginative and symbolic homes. She was able to move from the immediate spaces of the settlement dwelling to engage with her family home in Wolverhampton and Lady Margaret Hall in Oxford. Her sense of home and belonging unravelled when her body could no longer make her feel at home in LMHS and Lambeth. It was at this point that Hodson was forced to confront the idea that her home was finally unmade, and that she could no longer settle into settlement life.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Kate Bradley, Mike Benbough-Jackson, Diana Maltz, James Mansell, Eloise Moss, and Charlotte Wildman for their feedback on this article. Earlier versions of this paper were delivered to the AHRC Challenging Domesticities network, the Life Writing Group and LJMU History’s Social Cluster research group. I am grateful for comments made during these sessions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lucinda Matthews-Jones

Lucinda Matthews-Jones is a Reader in Victorian History at Liverpool John Moores University, where she teaches nineteenth-century gender and urban modules. She researches the British settlement movement and has published articles in Victorian Studies, Historical Journal, Cultural and Social Studies, and Journal of Victorian Culture. She co-edited Material Religion in Modern Britain, with Timothy W. Jones. She is currently writing her monograph Settling at Home: The Making of the British Settlement Movement, 1880–1920.

Notes

1 Alice Lucy Hodson, Letters from a Settlement (London: Edward Arnold, 1909), x.

2 ‘Lady Margaret Hall Settlement’, The Times, February 20, 1897, 5. For histories of the LMHS, see Katherine Bentley Beauman, Women and the Settlement Movement (London: Radcliffe Press, 1996), 105–19; Martha Vicinus, Independent Women: Work and Community, 1850–1920 (London: Virago, 1994), 211–46.

3 June Purvis, ‘From “Women Worthies” to Poststructuralism: Debate and Controversy in Women’s History in Britain’, in Women’s History: Britain, 1850–1945: An Introduction, ed. June Purvis (London: Routledge, 1995), 1–23.

4 K. E. M. Thickenesse, ‘Introductory Notes on Lady Margaret Hall Settlement’, Lambeth Local Library and Archives.

5 See ‘Oxford Preservation Trust’, The Times, July 9, 1936, 12; ‘Court Circular: The Oxford Society’, The Times, July 14, 1939, 17.

6 Ellen Ross, Love and Toil: Motherhood in Outcast London, 1870–1918 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993); Anna Davin, ‘Loaves and Fishes: Food in Poor Household in Late Nineteenth-Century London’, History Workshop Journal 41, no. 1 (1996): 188 n. 53.

7 David Burnham, The Social Worker Speaks: A History of Social Workers throughout the Twentieth Century (London: Routledge, 2016), 18–20. See also Ruth Livesey, ‘Reading for Character: Women Social Reformers and Narratives of Urban Poor in Late Victorian and Edwardian London’, Journal of Victorian Culture 9, no. 1 (2004): 52; Jane Lewis, ‘Family Provision of Health and Welfare in the Mixed Economy of Care in the Late Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries’, Social History of Medicine 8, no. 1 (1995): 9.

8 Vicinus, Independent Women, 211–46.

9 Seth Koven, Slumming: Sexual and Social Politics in Victorian London (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 198.

10 Ibid., 192–3.

11 See Arlene Young, From Spinster to Career Woman: Middle-Class Women and Work in Victorian England (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019).

12 Amanda Vickery, ‘Golden Age of Separate Spheres: A Review of the Categories and Chronology of English Women’s History’, Historical Journal 36, no. 2 (1993): 383–414; Jane Hamlett and Sarah Wiggins, ‘Victorian Women in Britain and the United States: New Perspectives’, Women’s History Review 18, no. 5 (2009): 707–9.

13 Thad Logan, The Victorian Parlour: A Cultural Study (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001).

14 Kelly Hager and Talia Schaffer, ‘Introduction: Extending Families’, Victorian Review 39, no. 2 (2013): 7–21; Naomi Tadmor, ‘Early Modern English Kinship in the Long Run: Reflections on Continuity and Change’, Continuity and Change 25, no. 1 (2010): 13–48.

15 Alison Blunt and Ann Varlet, ‘Introduction: Geographies of Home’, Cultural Geographies 11, no. 1 (2004): 3.

16 Richard Baxter and Katherine Brickell, ‘For Home UnMaking’, Home Cultures 11, no. 2 (2014): 134.

17 See articles in Victorian Review 39, no. 2 (2013).

18 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 69.

19 Ibid., 9.

20 Ibid., 99.

21 Penny Summerfield, ‘Concluding Thoughts: Performance, the Self, and Women’s History’, Women’s History Review 22, no. 2 (2013): 350.

22 See Ellen Ross, ‘Introduction: Adventures among the Poor’, Slum Travellers: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860–1920, ed. Ellen Ross (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 1–39.

23 Margaretta Jolly and Liz Stanley, ‘Letters As/Not a Genre’, LifeWriting 1, no. 2 (2005): 95.

24 Liz Stanley, The Auto/Biographical I: The Theory and Practice of Feminist Auto/Biography (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992).

25 Penny Summerfield, Histories of the Self: Personal Narratives and Historical Practice (London: Routledge, 2019), 34–37.

26 ‘Concluding Thoughts’, 350.

27 Jolly and Stanley, ‘Letters’, 95.

28 Summerfield, Histories of the Self, 23.

29 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, x.

30 Lady Margaret Hall Settlement Report, May 1909–1910, 21, 23.

31 Ibid., 23.

32 ‘Workers Among the Poor’, The Globe, March 17, 1909.

33 ‘In a University Settlement’, Westminster Gazette, May 28, 1909.

34 M.M. ‘Review: Letters from a Settlement’, Charity Organisation Review, 25, no. 150 (1909): 328. On Margaret McMillian’s life, see Carolyn Steedman, Childhood, Culture and Class in Britain: Margaret McMillan, 1860–1931 (London: Virago, 1990).

35 Katherine Brickell and Ayona Datta, ‘Introduction: Translocal Geographies’, in Translocal Geographies, ed. Katherine Brickell and Ayona Datta (London: Routledge, 2011), 3–21.

36 Philip Harling, ‘The Centrality of Locality: The Local State, Local Democracy, and Local Consciousness in Late-Victorian and Edwardian Britain’, Journal of Victorian Culture 9, no. 2 (2004): 216–34.

37 Suzanne Hall and Ayona Datta, ‘The Translocal Street: Shop Signs and Local Multi-Culture along the Walworth Road, South London’, City, Culture and Society 1 (2010): 69.

38 John Tomaney, ‘Region and Place II: Belonging’, Progress in Human Geography 39, no. 4 (2015): 508.

39 Alison Blunt and Robyn Dowling, Home (London: Routledge, 2006), 22, 29.

40 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 5.

41 ‘University Intelligence’, The Times, June 22, 1896.

42 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 9.

43 ‘Deaths’, Northern Whig, May 24, 1890, 1. See also ‘Deaths’, Worthing Gazette, May 28, 1890, 5.

44 ‘Lady Margaret Hall Settlement’, The Queen, February 6, 1897, 247.

45 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 4.

46 Ibid., 52.

47 Ibid.

48 Ibid., 105.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid., 8.

51 See also Ellen Ross, ‘Slum Journeys: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860–1940’, in The Archaeology of Urban Landscapes: Explorations in Slumland, eds. Alun Mayne and Tim Murray (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 14.

52 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 242.

53 Ibid., 234.

54 Mark Bhatti, Andrew Church, and Amanda Claremount, ‘Peaceful, Pleasant and Private: The British Domestic Garden as an Ordinary Landscape’, Landscape Research 39, no. 1 (2004): 40–52.

55 Ibid., 45.

56 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 234.

57 Ibid., 235.

58 Mark Bhatti, Andrew Church, Amanda Claremount, and Paul Stenner, ‘“I love being in my garden”: Enchanting Encounters in Everyday Life’, Social and Cultural Geography 10, no. 1 (2009): 63.

59 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 237–8.

60 Ibid., 239–40.

61 Rebecca Preston, ‘“Hope you will be able to recognise us”: The Representation of Women and Gardens in Early Twentieth-Century British Domestic “Real Photo” Postcards’, Women’s History Review 18, no. 5 (2009): 781–800.

62 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 239.

63 Judith W. Page and Elise, Women, Literature, and the Domesticated Landscape: England’s Disciples of Flora, 1780–1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 123.

64 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 241–2.

65 Ibid., 242.

66 Ibid., 241.

67 Ibid., 243–53.

68 Rebecca Preston, ‘The Pastimes of the People: Photographing House and Garden in London’s Small Suburban Homes, 1880–1914’, London Journal 39, no. 3 (2014): 216.

69 For instance, Deborah Cohen has argued that homes are ‘reveal personalities’: see Household Gods: The British and their Possessions (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006), 124.

70 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 243–53.

71 Risto Sarvas and David Frohlich, From Snapshots to Social Media: The Changing Picture of Domestic Photography (London: Springer, 2011), 5–22; Brian Coe and Paul Gates, Snapshot Photograph: The Rise of Popular Photography, 1888–1939 (London: Ash & Grant, 1977), 85.

72 Deborah Poole, Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image World (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 9.

73 Lady Margaret Hall Settlement Report. [1899–1900]

74 Lady Margaret Hall Settlement Annual Report, 1902–1903, 10.

75 Lady Margaret Hall Settlement Report, 1918–1919.

76 Lady Margaret Hall Settlement Report, 1919–1920, 12.

77 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 260.

78 Baxter and Brickell, ‘For Home UnMaking’, 134.

79 Ibid., 135–6.

80 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 12.

81 Ibid., 254.

82 Ibid., 11.

83 Ibid., 104.

84 Arjun Appadurai, ‘The Production of Locality’, in Counterworks: Managing the Diversity of Knowledge, ed. Richard Fardon (London: Routledge, 1995), 205.

85 Emily Cuming, ‘“Home is home be it never so homely”: Reading Mid-Victorian Slum Interiors’, Journal of Victorian Culture 18, no. 1(2013): 368–86. Ellen Ross, ‘Adventures among the Poor’, in Slum Travelers: Ladies and London Poverty, 1860–1920, ed. Ellen Rose (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 1–39.

86 Ruth Livesey, ‘Reading for Character’, 43–67.

87 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 14–15.

88 Ibid., 15.

89 Ibid., 16.

90 Ibid., 13.

91 Shannon Jackson, Lines of Activity: Performance, Historiography, and Hull-House Domesticity (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000), 42.

92 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 101–2.

93 See Rachel Rich, ‘“If you desire to enjoy life, avoid unpunctual people”: Women, Timetabling, and Domestic Advice, 1850–1910’, Cultural and Social History 12, no. 1 (2015): 95–112.

94 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 102, 19, 101.

95 1871 Census return for Alice Lucy Hodson, The National Archives of the UK (TNA), Kew, UK.

96 David Conradson and Deirdre McKay, ‘Translocal Subjectivities: Mobility, Connection, Emotion’, Mobilities 2, no. 2 (2007): 169.

97 Anne M. Lawrence, ‘Morals and Mignonette; or, the Use of Flowers in Moral Regulation of the Working Classes in High Victorian London’, Journal of Historical Geography 70 (2000): 24–35.

98 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 56–57.

99 Ibid., 56.

100 Lawrence, ‘Morals and Mignonette’, 32. For a discussion on the uses of the courtyard by working-class people, see Lesley Hoskins and Rebecca Preston, ‘Chickens, Ducks, Rabbits and Me Dad’s Germaniums: The Uses and Meanings of Yard, Gardens, and Other Outside Spaces of Urban Working-Class Homes, 1890–1930’, in The Working Class at Home, 1790–1940, ed. Joseph Harley, Vicky Holmes, and Laika Nevalainen (Cham: Springer, 2022), 145–70.

101 Hodson, Letters from a Settlement, 18.

102 Ibid., 36, 140.

103 1911 Census return for Alice Lucy Hodson, TNA.

104 Helen O Hodson, England & Wales 1837–2007, 6B, 427, https://www.findmypast.co.uk.

105 1921 Census return for Alice Lucy Hodson, TNA.

106 Alice Lucy Hodson, 98b Banbury Road, Oxford, 1939 Register, 29 September 1939, https://www.findmypast.co.uk. See also C. Anson, ‘Alice Lucy Hodson: 1869–1963’, The Brown Book: Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford (December 1963), 40.

107 Anson, ‘Alice Lucy Hodson’, 40. Beauman, Women and the Settlement Movement, 110.

108 Anson, ‘Alice Lucy Hodson’, 40.

109 Ibid.

110 ‘Deaths’, The Times, December 12, 1963. Historical currency converter https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetary-policy/inflation/inflation-calculator.