ABSTRACT

This article uses a spatial framework to explore socialist and feminist activism by mixed sex revolutionary organisation Big Flame (1970–1984). It focuses on a Big Flame ‘base group’ embedded within the working class community of Kirkby, Merseyside. It adds to the growing historiography on women-centred community-based organising to situate Big Flame amongst the groups across Europe engaging in activism around spaces for new types of politics. Activists used ‘the second front’ to engage with feminist debates and challenge gendered discourses. These initiatives, as well as having a socio-psychological impact on the activists themselves also formed part of what was to be the ‘personal and collective liberation’ which Gerd-Rainer Horn outlined as a key legacy of 1968. This article will suggest that Big Flame’s prioritisation of feminism and experience enabled them to blur the boundaries between the private, public, social and intimate everyday experience. The use of oral history interviews sheds light on the inner world of activists’ subjective experience as they navigated the complexities of the discursively connected structures of gender and class. Women in Big Flame documented their own autonomous feminist experience and as Big Flame made the personal political for working-class women on the estates, these expressions made their unseen activism as women visible.

Introduction

We’ve seen that the housewives are not necessarily isolated and powerless. We’ve seen them build the backbone of community networks and organisation, slowly turning Tower Hill from a housing estate into a community that can be a power base for the whole class.Footnote1 (Big Flame Tower Hill Base Group, 1978)

Big Flame (1970–1984) was a mixed sex socialist feminist organisation made up of men and women whose political outlook was shaped by the post 1968 activist milieux. Initially, the organisation was a newspaper entitled Big Flame and was produced on Merseyside by several students, activists and trade unionists. By 1971, members of the collective formed small groupings they called ‘base groups,’ intervening in workplace and community struggles to try and draw together a socialist and feminist analysis. Big Flame placed the home at the centre of their analysis with a focus on ‘women-centred’ issues such as social space, domestic work, childcare and reproduction.Footnote2 As an example of what Gerd Rainer-Horn termed, ‘laboratories of a new kind of politics,’ Big Flame activism often included food co-ops, shared childcare and communal living all signified a utopian reimagined way of organising, a turn to the personal with a shared experience of reimagining revolutionary living in all aspects of everyday life.Footnote3 By forging their own spaces for political activism, base groups were embedded within working-class communities; intervening, experiencing, and documenting working-class struggle, contesting the private, public and social space of the estates around them.

Recent scholars focused on feminist community activism have used a spatial framework, enabling a ‘window’ through which to observe the multi-faceted uses, significance and political meanings of private and public spaces such as book shops and squatted houses. This work has largely focused on the role of women’s groups in this period, to shed light on how the feminist challenge redefined the scope of the political.Footnote4 This kind of activism often altered the urban landscape as spaces were shaped, defined or contested by people, and filled with their social, cultural and political praxis.Footnote5 Lucy Delap’s work concentrated on feminist bookshops as a safe environment for feminist political activism, a significant space for activism and as a meeting place aiding and diffusing feminist ideas.Footnote6 Christine Wall also assessed the collective activity of squatting by women engaged in feminist activism to explore how it provided a ‘spatial framework’ within which to operate.Footnote7

In this article, I use the example of Big Flame’s activism in one of their base groups on a working-class housing estate in Kirkby, Merseyside, to explore their role in feminist community organising around the Kirkby rent strike of 1972–1973. As sociologist Leslie Sklair has shown, the importance of the Kirkby rent strike lay not in its ability to ‘win’ but in its capacity for ‘mass action.’Footnote8 I argue that activism around this rent strike should be understood as a form of feminist activism which was gendered as well as being class-based. The private space of the home was the focus of Big Flame’s analysis, expanding the housing issues of the rent strike to politicise women-centred private experiences related to motherhood, the domestic role of wife and carer referring to the campaigns for a better social community area as the ‘mass struggle of housewives.’Footnote9

The introduction of the Housing Finance Act (HFA) in July 1971 exacerbated the national housing crisis by raising the rents of local authority housing and prompted often women-led working-class organisation and resistance in and around the space of housing estates.Footnote10 The bill sparked rent strikes across the UK, with housing and streets becoming a key site for the contestation of space and community activism, and marked the beginning of the Tower Hill Big Flame base group.Footnote11 Acting in support of the tenants, several members, including Janice Marks and Christine Davidson initially travelled to Tower Hill during the rent strike before moving to the estate to start a women’s group. The Tower Hill women’s group enabled them to work across the interconnected private, public, and social spaces to politicise the everyday experience of housewives. They did this by challenging the urban environment and its policies, blurring the lines of these boundaries to make the personal political, as well as making their own activism seen.Footnote12 Moreover, the structure, urban development and character of Tower Hill and Kirkby more broadly had enabled Big Flame to embed themselves within an already-militant community.

Big Flame’s prioritisation of feminism and experience enabled them to blur the boundaries between private, public, social and intimate experience in the everyday, providing an alternative within the left-wing milieu of the period. As Big Flame base groups politicised the physical spaces they occupied, they also reflected the experience of class struggle, explored the ‘double burden’ for women and recast these spaces as areas for feminist activism.Footnote13 These physical spaces were accessed and provided a space to diffuse ideas and document experience. Although Big Flame publications used familiar gendered discourses to appeal to women and their responsibilities around the home, their intervention encouraged women to challenge the fixity of gendered discourses surrounding women, motherhood and domesticity.Footnote14 Furthermore, as they documented their own experience, women in Big Flame uncovered their gendered ‘invisible labor’ within the mixed-sex organisation.Footnote15 Influenced by the ‘expressive revolution’ and increased attention for the ‘quest for an authentic self,’ these expressions made their own ‘invisible’ work as women active in a mixed sex group ‘visible.’Footnote16 Activists also documented their own experience of working-class life.Footnote17 By living on working-class housing estates, often as outsiders from a middle-class background, activists were able to access, document and navigate the working-class experience as the abstract space between themselves and the world.Footnote18 Using gender and class as a focus they were able to access and experience these interconnected systems.Footnote19

This article uses documents from Big Flame’s own archives as well as five oral history interviews I conducted with former Big Flame members between 2017 and 2022. As Penny Summerfield has demonstrated, anecdotal memories are usually dramatic or amusing, consisting of significant symbolic ‘snapshots.’Footnote20 Key themes from the memories provide rich detail into the private and public life of the activists, often expressing emotional recollections at injustice, exploitation, and depth of feeling often providing an insight into their ongoing activism. This article situates Big Flame as a significant interventionist organisation engaged in socialist and feminist organising on a working-class housing estate, adding a tile to what Lucy Delap recently termed the ‘mosaic’ of global feminist activism.Footnote21

Kirkby, a post-war housing experiment

There is no doubt that the Kirkby development will be a very attractive one, and the standards of designs, not only for the layout, but in the individual dwellings will be high.Footnote22 (Ronald Bradbury, Architect and Director of Housing for Liverpool, 1953)

I wonder if they built these flats deliberately to hurt us.Footnote23 (Female resident of Tower Hill, 1974)

In 1971 there were two active Big Flame base groups based in Merseyside; one based around the Liverpool Docks and the other at Fords in Halewood. Activists initially shared a house in Liverpool, which contained a fluctuating number of four to six activists, mostly radicalised students, as well as several women who had been involved in women’s liberation groups.Footnote24 In his oral history interview, Big Flame founder and former member, Nick Davidson recalled moving to Liverpool, in an evocative memory how one of the members raised the funds for the property:

She had rich parents and she was also a would-be violin player, and she had a really expensive violin which she sold and pressurised her parents. With that we were able to buy a house in Old Swan.Footnote25

Several activists lived together in the house before separating to work in and live around base groups across Merseyside, including on the Tower Hill estate of Kirkby, eight miles north of Liverpool. Kirkby was one of several new towns built to ease the post-war housing crisis in the city, with 50,000 local authority tenants uprooted from city slums over 6 years.Footnote26 Kirkby became part of the post war experiments in modern living with brutalist high density, high rise living, constructed to house working-class council tenants ().Footnote27

Housing estates, including the streets, social space and private homes within them have historically been spaces of contestation for class-based struggles. The post-war slum clearances of the late 1960s in the UK had reconfigured urban landscapes, with working class tenants uprooted out of the cities into unfamiliar new towns and new estates. Recent work has complicated the narrative of experiences of displacement and decline in new towns after slum clearances, particularly in Glasgow.Footnote28 However, the example of the unfinished estate of Tower Hill unswervingly points to a narrative of displacement and discontent. Officials were perceived by tenants as ‘virtual slumlords,’ who made compulsory purchases of the land to demolish slum housing, forcefully uprooting tenants and dividing already-established communities and networks. Criminal negligence of officials in the planning of the town exacerbated discontent and poor town planning meant a lack of transport links, amenities, healthcare or leisure facilities.Footnote29 Tenants in high rise flats on the estate of Tower Hill were significantly affected, with the ‘crude, slab-like structures’ containing small, badly built and poorly insulated flats.Footnote30 As early as 1965 over 130 Tower Hill tenants had written and signed a letter to be handed to Prime Minister Harold Wilson, detailing their grievance at paying high rents for sub-standard housing.Footnote31

Former Big Flame activist Janice Marks reflected on the housing provision with a memory which encapsulated the depth of feeling as she recalled the scene before her.

You’d have women quite often living at the bottom alone with their children, already struggling with their mental health. On top of everything else they’d have all this water coming down and they’d get flooded and flooded again. The damp wasn’t just from that, it was also a structural problem in the flats as well, I remember once me and Chris going to a house, a flat, and there was literally fungi growing on the walls and the black mould. They were told by housing officers that they breathed too heavily, they didn’t open the windows enough, they had sex too often, all this shit about why the flats were damp.Footnote32

There was a massively disproportionate number of working-class families being moved with 99% of tenants reported to be white working-class.Footnote33 There was also a disproportionate number of young people. Dubbed, ‘A Children’s Township,’ by the local press, the potential issues were largely ignored, and youth was linked to the future ‘great success,’ of the town.Footnote34 However, as young working-class children came of age, the labour market was flooded with unskilled workers. This highlighted what Rankin referred to in 1974 as Kirkby’s ‘abnormalities of structure.’Footnote35 The early ghettoization of Kirkby was exacerbated as the young children who were moved to Kirkby grew into teenagers, vandalism, gangs and crime rocketed.

The economic and social deprivation, high crime rates and vandalism in Kirkby caught the attention of the national as well as the local press in several expose articles.Footnote36 The Daily Mail, reporting in 1975, interviewed residents in a tell-all vulgar article about the ‘third world’ town. The report covered social malaise in Kirkby with images of graffiti, and lead-stripped rooftops. Kirkby became infamous nationally, with the newspaper referring to the town as ‘a social experiment gone wrong.’Footnote37 Over a number of articles, the Daily Mail’s preferred discourse when writing about Kirkby was the language of war and terror. Repeatedly referring to ‘no go areas’ with phrases like ‘siege mentality’ comparing Kirkby to a town torn apart by war.Footnote38 Kirkby would be known as bearing the hallmark of a ‘classic illustration of the failures of planning.’Footnote39 A report in 1981 by the Centre for Environmental Studies clearly reveals the failings of town and urban planning, claiming ‘policy-makers and planners must carry considerable responsibility for failing to ensure means and resources were available to implement the original plan.’Footnote40

Indeed, some of these people did carry the responsibility in the form of jail sentences. As reported in The Guardian in 1978, builder George Leatherbarrow, leader of the council David Tempest and architect William Marshall were all convicted of corruption for their part in the creation of the town of Kirkby, guilty of accepting bribes for contracts.Footnote41 Amongst evidence cited was the construction of a ski slope which was built over a main water pipe and reportedly facing the wrong way. At a cost of £100,000 the ski slope was demolished without ever being used.Footnote42

In July 1971, Edward Heath’s conservative government introduced the Housing Finance Act (HFA). Essentially, the HFA raised rents of local authority dwellings by an act of parliament, and promised rents that would reflect, ‘value by reference to its character, location, amenities and state of repair.’Footnote43 Known as the ‘fair rents act,’ those who could not afford the new rents would be entitled to a rebate, paid for by better-off tenants.Footnote44 However, it was raised in parliament by leader of the Labour party Harold Wilson that the take-up of means-tested payments would probably be low.Footnote45 Pressure was exerted from central to local government councillors to implement the act. Labour voted against its implementation, but the party hierarchy urged Labour councillors to use the act to protect tenants, resulting in struggles within the Labour Party and a split over the issue.Footnote46 Liverpool councillor Bill Sefton announced that ‘the Labour movement shall not take any steps which may lead to the implementation of this bill.’Footnote47 Interviewed by the local press, Tony Boyle, an activist in Kirkby and member of the International Socialists, stated, ‘we want a hundred per cent support, and the council members at a meeting on Wednesday said we would have it.’Footnote48 However, the lack of organisation at local government level, compounded by impending threats by a central conservative government hell-bent on getting its way meant that Labour-controlled councils conceded. Demonstrators jeered Sefton as he made the announcement.Footnote49 Adding insult to injury, it was reported that as well as the rent increase, rate rises in Kirkby were the third highest for any urban district in the country.Footnote50 As slum clearance continued amidst the rent rise, a city planning officer remarked, ‘not only were [tenants] generally reluctant to move, but they would be unable to pay.’Footnote51

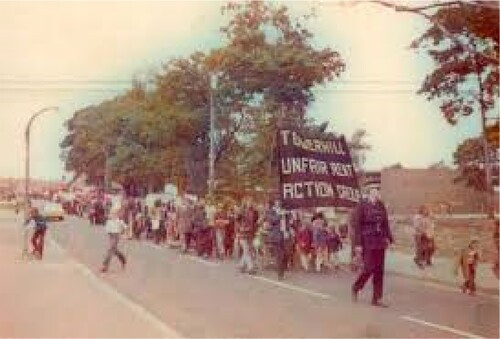

Despite Labour council leader David Tempest’s reassurance that they would press for the ‘lowest possible rent increase,’ tenants were already planning to organise.Footnote52 Tower Hill Unfair Rents Action Group was formed, made up of community members, International Socialists and communist activists. They met to organise resistance to the rent and rate rises. Tower Hill Unfair Rents Action Group secretary Tony Boyle announced to the local press: ‘as soon as the Housing Finance Act is implemented, the council will have a total rent and rate strike on their hands.’Footnote53 The rent strike began in October 1972 and was facilitated by the far left, including the Communist Party, the International Socialists and Big Flame.

The Kirkby rent strike (1972–1973)

Although there was a wave of rent strikes nationally, Kirkby stood out as the only district in the country to enact a total rent and rate strike. Importantly, alongside the rent strike, workers and tenants organised collectively to protest redundancies and rent increases, drawing together community and workplace issues.

During the rent strike Big Flame produced weekly leaflets to keep tenants updated on developments, lobbied council meetings, and leafletted local factories for support.Footnote54 Activists regularly travelled to the estate to assist Tower Hill Unfair Rents Action Group and utilised the urban space on the estate. Tower Hill was divided into eleven zones, each zone sub-divided and an anti-eviction system put in place. Groups of activists followed rent collectors to ensure there would be no ‘strike breakers.’Footnote55 Tenants were urged to send their rent demand letters back to sender with ‘on rent strike’ written in ink, and barriers were erected to keep the bailiffs out. In early December, 1972 Big Flame and other activists stormed the council offices in Kirkby town centre, clashing with police and council officials.Footnote56

Testimony by former Big Flame members often depicted iconic scenes, evocative images of radical activism confirmed Big Flame’s involvement and situated them as a radical interventionist group on the estate. Christine Davidson was one of three activists who became involved with the rent strike and established the Tower Hill base group. Christine had moved to Liverpool from Sussex University having been radicalised during 1968 demonstrations against the war in Vietnam and becoming involved in women’s groups.Footnote57 Reflecting on her involvement later in a written document, she focused on the importance of the landscape of Kirkby. She emphasised how the few access roads and a main road allowed residents to make the best use of barriers against the authorities. The document provides radical ‘snapshots’ of what some of the women did on the estate, demonstrating their radical approach.

Following and obstructing rent collectors (at one point kidnapping a Granada TV reporter by mistake, and then using the opportunity to educate him).Footnote58

Former member Martin Yarnitt’s fragmented memories from the time included an image of an isolated incident, and like the reflection above, projected a representation of radicalism with a reckless streak.

All I can remember is one day for some reason we had highjacked a double decker bus and my job was to drive it around. I don’t know why exactly or what we did with it.Footnote59

As police entered Kirkby to make arrests of rent-strikers, the Big Flame newspaper enthusiastically reported the use of air raid sirens and roadblocks by activists and over 100 tenants marched to Kirkby industrial estate to try and get support from industrial workers.Footnote60 When jail sentences were announced there was an immediate walk-out at Anglia Paper Products in Kirkby, and on Sunday the 9th December, there was a demonstration of over 400 people outside Walton jail.Footnote61 Activists used loud speakers to draw attention to their cause, and two coach loads of supporters from Manchester and Oldham attending in solidarity.Footnote62 The newspaper reported that police were overwhelmed by the ‘organised defiance’ of the rent strikers.Footnote63 The mass protests outside Walton Jail were captured on film by Nick Broomfield, a red Big Flame flag held aloft in one of the scenes.Footnote64 The march attracted the attention of the national press, with The Guardian sympathetically reporting that a jailed tenant’s son, Paul, aged 4, held a banner reading ‘Release my Daddy for Christmas’ ().Footnote65

Big Flame’s published material always offered a gendered analysis and aimed to prompt residents to draw together community and industrial action. ‘Mass action’ was encouraged from the outside, with Big Flame interventions and publications including women as well as men in their class analysis.Footnote66 As early as 1970, Big Flame had reported rent rises across Merseyside with the headline ‘Don’t Let the Missus Do all the Battling,’ identifying the key role of housewives and encouraging men to support issues that affected the whole community.Footnote67

In January 1972, alongside the rent strike, eighteen workers occupied the Fisher-Bendix factory following threats of mass redundancy, hanging a sign above the entrance declaring ‘under new management.’Footnote68 The occupation lasted five weeks and was covered by the national press. The Guardian reported that 600 workers had taken over the factory.Footnote69 Big Flame produced a two-sided report in collaboration with the workers, using their own words to demonstrate the radical potential of the occupation, focusing on workers control to the exclusion of the shop steward. Leaflets, newspapers and pamphlets used the workers interviews to include an explanation of the novel implications of a sit-in rather than a strike, stating that women ‘were as involved as anyone else in the occupation.’Footnote70 The statement issued from the workers called on a complete boycott of Fisher Bendix products, specifically addressing housewives.Footnote71

Former East London Big Flame member, Jenny Fortune recalled visiting the estate during the rent strike, and described a dramatic scene, demonstrating the example of Big Flame organising on the estate.

Something that really impressed me was that the Birds Eye factory was occupied in Kirkby, and I’m pretty sure I was there when people marched out of the occupied factory to defend people who were being threatened with eviction on the Tower Hill estate.Footnote72

Workers who participated in the rent strike marches were suspended from the factory on Kirkby Industrial Estate. In response, tenants organised a mass picket; women with babies in prams and members of THURAG with loudhailers were joined by workers and dockers.Footnote73 Big Flame reported the inclusion of women in these actions to blur the line between the ‘privatised female’ and the industrial worker, who were sometimes one and the same, with the Big Flame newspaper reporting a resident saying, ‘after all, the majority of people in Birds Eye live on the estate.’Footnote74

After fourteen months, seven tenants were jailed for non-payment and the rent strike in Kirkby ended, and tenants were ordered to repay what they owed at the rate of £1 a week.Footnote75 Activism around the community continued, and members of Big Flame moved from Old Swan to Kirkby, continuing their activism as part of Big Flame’s Tower Hill base group.

Big Flame Tower Hill Base Group

In October 1973, Big Flame activists Janice Marks and Marcello dall’Aglio entered the council offices in Kirkby, in search of housing in the area. In her oral history interview, Janice Marks set the scene.

We entered the office as a married couple. We literally walked in and said, ‘we’d like to live on Tower Hill’ and we walked out with a key to number 21 Pear Tree Court.Footnote76

From the flat, members intervened in community issues, centring the working-class housewife. For a small organisation, Big Flame produced a wide range of publications, ensuring the ‘democratisation of debate.’Footnote77 As well as physical autonomous space being used for activism on the Tower Hill estate, socialist and feminist print culture was also significant.Footnote78 Underpinned by a socialist analysis and with the inclusion of a feminist perspective, Big Flame publications often used the appeal of familiar gendered discourses of women as wives and mothers, encouraging women to embrace the identity of the housewife as a ‘producer of capital,’ to feel empowered to oppose exploitation.Footnote79 On Tower Hill, Big Flame publications situated the housewife as a put-upon homemaker or bearing the duel burden of housewife and waged worker. Publications showed how low wages meant ‘scrimping and scraping,’ and cuts to hospital spending meant more work for women as nurses, or more work for women undertaking unpaid ‘care in the community.’Footnote80

To introduce the new women’s group to the estate, the base group reported that over 2000 leaflets were distributed, and weekly meetings were arranged in Tower Hill Community centre, attended by around thirty women.Footnote81 Their print material concentrated on women-centred issues on the estate relating to the domestic and social spaces for children and families. Tower Hill base group’s self-published documents were intended to be read widely inside and outside of the estate reflecting feminism’s key idea of making the personal political in the everyday experience. Kirkby Bulletin, and later the Kirkby Radical Alternative Press were produced together with women on the estate at Tower Hill Community Centre, as well as producing articles for the series of women’s publications, Women’s Struggle Notes, which was produced collectively within the women’s commission in Big Flame. Publications encouraged women on the estate to embrace the identity of the housewife as a ‘producer of capital,’ to feel empowered to oppose exploitation.Footnote82 Typically, articles focused on the private space of the home, including housework and childcare, to local areas of activity; workplace disputes and campaigns for road safety barriers to national concerns, and public demonstrations by the National Abortion Campaign against the James White Bill, moving in and out of private and public concerns to make links between the two.Footnote83 These articles often included hand-drawn cartoons of women performing the role of wife, mother and worker in the home. Tower Hill base group reported back centrally to Big Flame that ‘housewives can’t detach wages from rent prices, school buses or the state of the houses.’Footnote84 As rents increased, and public spending was cut, Big Flame emphasised the exploitation of the housewife as a home-maker or bearing the dual burden of housewife and waged worker.

One of the key tropes within the oral histories of Big Flame members was the idea of building significant relationships with women on the estate and using their interventions as a support network for women, encouraging them to become active around their own everyday experience. Janice Marks’ narrative emphasised the role of activists in support of women on the estate.

It was about us supporting people in their struggles and supporting people to develop and empower themselves, not that we’d have used the word empower, but kind of find their own way and maybe, certainly when we were working on the flats in Tower Hill, maybe get involved with other things as well.Footnote85

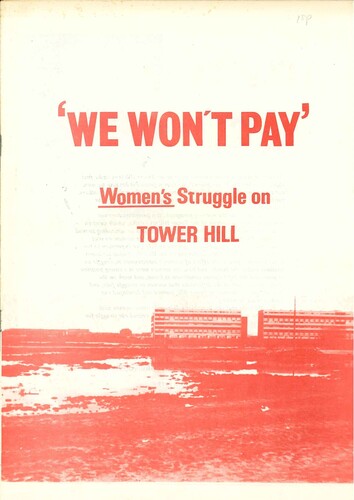

Big Flame publications often demonstrated the political development of women with the base group and on the estate and documented their increased confidence and political engagement and radicalisation. The 1973 pamphlet, We Won’t Pay, Women’s Struggle on Tower Hill, documented Big Flame involvement in the rent strike and activism in Kirkby. Beginning with a history of Kirkby, the document focuses on the private role of women at home, their life in public, in workplaces and the community, their personal and political development socially with other women.Footnote86 The base group was shown to be important to ‘reshape class consciousness’ and to encourage the autonomous organising of women. Interviews with women on the estate were used to show this in action in everyday private and public life and put forward an active, confident, militant political identity of the ordinary working-class housewife, embedded within the familiar role of wife and mother. One woman is quoted on the rent strike, her words linking back to the familiar role of the housewife, the strike presented as a way to uphold her position, ‘it’s your house and you’ve been brought up to look after that.’Footnote87 Another demonstrated how women in particular had overcome their insecurities to feel empowered ().

I didn’t think I was capable of doing it. But I’m not surprised now that women are going from strength to strength.Footnote88

As the Tower Hill Base Group settled in, they embedded themselves in working-class life, engaging in community struggles as part of the women’s group, demonstrating the crucial importance of these smaller-scale spaces Big Flame activists and interventions. The flat in Tower Hill planted Big Flame within the working-class community and enabled them to encourage women on the estate to claim the public space as their own through autonomous organising, blurring the division between private and public space.Footnote89

Discussions within the women’s group centred on women’s everyday concerns, beginning with the isolation of women on the estate, the need for a playgroup, better road safety and school buses for children and a centre for reproductive healthcare for women.Footnote90 Discussions took place about ‘organising autonomously, in relation to the whole class struggle,’ to empower and encourage women to value their key role in community activism.Footnote91 Political consciousness by the women on the estate was also demonstrated by Tower Hill resident and activist May Stone in the film Behind the Rent Strike.Footnote92 Interviewed by Broomfield, she commented

I question everything now. I still talk to other women about babies, but conversations go deeper—you’re no longer discussing their teething problems, you’re talking about the kind of clinics there for you.Footnote93

Big Flame activism also sought to make the link between women’s paid and unpaid work in the workplace and community was highlighted using the example of cuts to hospital budgets which meant more work for women as nurses, or more work for women undertaking unpaid ‘care in the community.’Footnote94 These discussions led to the base group’s engagement with the Wages for Housework debate.

Big Flame’s feminist analysis and challenges to women’s oppression focused on the private space of the home and the connecting duties linked to the role of women as wife and mother.Footnote95 As the post-war employment pattern saw a significant increase in women entering the workplace, discussions in feminist groups oriented around waged and unwaged work.Footnote96 Socialist feminist groups, including Big Flame, made links directly between the home, the reproduction of labour and the oppression of women, drawing together key ideas about the relationship of class, gender and capitalism.Footnote97

These ideas had been diffused and found expression for many feminists the Wages for Housework campaign which gained traction amongst feminists internationally.Footnote98 The campaign had emerged in the early 1970s as a global feminist movement and began in Padova, Italy in 1972. Dalla Costa’s Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community, published in 1971 used the work of Marx and Engels to form a Marxist-feminist analysis to situate the housewife central to the struggle against patriarchy and capitalism. For Dalla Costa, the production and reproduction of labour power was undertaken by housewives as hidden work inside the home, and consequently, the housewife was an unwaged worker. WfH would therefore provide women with a ‘lever of power.’Footnote99 Silvia Federici had pointed to the escape from housework as a ‘delusion’ she concluded that all women were housewives, including those engaged in waged work outside the home, and maintained that ‘until we recognise our slavery we cannot recognise our struggle against it.’Footnote100 The WfH debate within the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) involved theoretical, ideological and strategic arguments and was widely debated in the journals and pamphlets of the WLM such as Red Rag, Shrew and Spare Rib, as well as within the broader Left.Footnote101

Specific to Kirkby, in the 1970s, 55% of the employment force were women, working mainly in manufacturing in unskilled production line work in food processing such as the Birds Eye factory on Kirkby industrial estate.Footnote102 In a document produced to argue for the adoption of the WfH demand by Big Flame, Christine Davidson argued that all the activism that the base group had engaged in, including the rent strike back in 1972, was inspired by, and for, the WfH campaign. This prompted a debate within the organisation itself.

In 1975 Big Flame published a series of internal documents debating the idea of WfH. Influenced by the work of Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James documents produced set out the perspective of Liverpool Big Flame, although it was not representative of all members. The author declared that ‘housework is the work of producing and reproducing labour power for the bosses.’Footnote103 She explicitly stated that WfH informed her own activism, but she had avoided using the slogan on the estate. ‘These are part of WfH—we didn’t want to use the term WfH because it might not have made anything clearer. It’s a demand which shapes a perspective, a perspective which shapes a demand.’Footnote104

Big Flame remained self-critical and open to debate within Big Flame regarding WfH. Liverpool Big Flame reported to the national conference that for the women on Tower Hill, realistically it was impossible to ignore that housework ‘defines and affects the lives of all working-class women.’Footnote105 In the ongoing debate within Big Flame, activists in support of WfH used their experience of the Tower Hill Base Group to argue their support; community struggles for road safety barriers, housing and zebra crossings, the author referring to Tower Hill as ‘one of the most militant, organised and experienced estates in the country.’Footnote106 Christine stated that ‘every one of them has picked up on W for H quicker than anything else.’Footnote107 As the only base group to support the demand for WfH, reflections about these debates on Tower Hill were often sketchy and were not a key part of participants’ narratives. Nick Davidson, editor of the Big Flame newspaper who lived in the flat in Tower Hill consigned the WfH debate as on the radical feminist agenda. When asked about this, Nick presented a memory of conflict and a dismissal of the debate as tangential to Big Flame.

There was a good deal of hostility towards them. We had a run in with Selma James. They had a meeting at the university, and we went along and probably asked naïve question she was incredibly dismissive, and it was difficult to have a dialogue with her. It wasn’t a big issue for us.Footnote108

Janice recalled their support for the campaign differently, recalling using Kirkby market to set up a stall to communicate the debate to women on the estate.

We used to occasionally do these stalls in the market. I remember doing one about the woman’s right to choose, which was a bit scary in Kirkby market. I think we might have done one on the Wages for Housework because me and Chris were on the, we were very sympathetic to Wages for Housework.Footnote109

Janice also recalled being active around community spaces, communicating these ideas to women as they engaged in everyday community and domestic settings, and recalled the debates more broadly in Big Flame.

One of the places we would go to tell people about that with leaflets was the launderette, which was underneath one of the blocks. Some of the women, men as well in Big Flame, and most of the people on the left were against Wages for Housework.Footnote110

Big Flame did not adopt the slogan ‘Wages for Housework,’ and the base group on Tower Hill was the only one in support. Instead, it was agreed that the Big Flame standpoint was to demand a ‘guaranteed independent income for all.’Footnote111

Big Flame often produced documents which explored their own lived experience of activism in working-class spaces. The democratisation of psychology in the late 1960s had prompted a ‘confessional’ turn, and a desire for feminists to explore their authentic self.Footnote112 Experience around 1968 in consciousness-raising or close-knit women’s groups enabled them think, speak, and write about their own experience. This enabled activists to further embed themselves within their activist spaces, to document their experience as lesser-known activists and to show the often ‘hidden’ work of women in Big Flame.Footnote113 Living on the estate meant that their focus was on building relationships, making emotional bonds, nurturing and empathy.Footnote114 This type of emotional activism is invisible, but crucial for sustaining the social and political ties to working-class women and their everyday lives on the estate. By making this emotional activism visible, they were able to politicise their own everyday experience as activist feminist women within a socialist feminist group.

Contained in the 1977 internal bulletin, A Week in April detailed one week of a woman’s subjective experience as a Big Flame activist as she navigated the abstract and physical private, public and political space of Tower Hill. Her experience is portrayed against the backdrop of the urban working-class environment, presenting her life as an activist intertwined with experience of working-class life as a woman and an activist. The document offers a snapshot of her life as she navigates her social and public world to present these spaces as the terrain for political action. Her motive for writing the report is explained within it.

In my experience on Tower Hill, in the rent strikes, squatting, safety barriers, etc. I've seen just how important it is what goes on between militants.Footnote115

The report communicated activity to other Big Flame activists outside of the base group and presented their intimate experience as activists. This included their often-challenging experience of class and gender on the estate as well as their own social, political, and private world.

The urban built environment of Kirkby was important to the author as the report communicated the difficulties ‘especially in a place like Tower Hill.’ She observed the lack of social provisions, reflecting the concerns raised in the women’s group, a lack of nurseries, playgroups, reliable transport and healthcare, particularly for women.

As well as exploring the wider difficulties, the report situated her own invisible personal struggle intertwined with the more visible struggles as an activist. The extent of her activism in the week was reported; she organised a coach to London for women in Tower Hill to attend the National Abortion Campaign demonstration, raised funds through raffles and jumble sales, whilst also trying to arrange pregnancy tests, and later, an abortion for herself. The author’s engagement with deprivation in Kirkby is demonstrated as she queues in a shop, lending two pence to the woman in front who does not have enough money. She reported on the reality of everyday life for women experiencing double burden as they get off the bus straight from work, ‘all looking tired and white,’ shopping bags in hand. She also reported on her personal friendships and sexual relationships with men documenting her boredom at compliments by her male friends on her body, and their lack of support for her right to choose.Footnote116

At the end of a long day, she reported that she walked home from one of the pubs in Tower Hill and evocatively recasts this urban, dilapidated and left-behind town’s space as her own.

Walk home across the estate—half the lights are missing, and it looks like a lunar landscape. Feel nervous but even at times like this I like the place—it’s home.Footnote117

The way that activists used the urban built environment for their feminist analysis and praxis was a key tenet in Big Flame activism. Their approach to documenting their own activism as they lived it, publicly in their newspaper and privately in their internal documents demonstrates the importance of the urban built environment, their analysis focused on the working-class housewife.

As an interventionist organisation made up of mostly middle-class members, Big Flame reflected some of the issues experienced as part of the WLM network more broadly around class and experience. Big Flame attempted to break down potential class barriers to include working-class women in Big Flame politics, particularly through the use of publications.Footnote118 Pamphlets such as Struggle Notes were criticised by Big Flame members as being difficult to read, perhaps making BF ‘unapproachable to working-class women.’Footnote119 In an internal discussion bulletin, proposals for a new Struggle Notes were outlined in key points: The need to communicate to working-class women the root of their oppression as unwaged housewives, revolutionary change through the unification of all working-class struggles, as well as supporting the six demands of the WLM to empower women.Footnote120 Big Flame used this communication as a method of intervention. By communicating effectively with working-class women, their strategy of interventionist politics would enable already politically aware women to understand BF politics of uniting industrial and domestic struggles as one community struggle. Jenny Fortune reflected on the problem of middle class activists communicating with working-class women, ‘it’s always an issue I think—how middle class political women relate to working-class women.’Footnote121 Reflecting on this, Jenny recalled that she had observed Big Flame women living in the flats were able to get closer to people and issues in Tower Hill, and ‘gained the trust a lot of working-class women on the estate.’Footnote122

On Tower Hill, community struggle continued as the women of Big Flame worked to empower women to campaign for school buses, road safety barriers and against rent and rate increases. The base group also leafletted and campaigned in Kirkby town centre for the National Abortion Campaign, getting involved in street theatre in Liverpool city centre.Footnote123 All of these initiatives were identified as the ‘mass struggle of housewives.’Footnote124 Big Flame’s aim of uniting these issues was led by Big Flame women on Tower Hill, as they experienced the specificities of issues that affected women. They reported back centrally to Big Flame that ‘housewives can’t detach wages from rent prices, school buses or the state of the houses.’Footnote125 For the base group, the situation in Kirkby meant that women who were already politically aware on the estate would have potential to become involved in mass community action ().

In keeping with Big Flame’s strategy of direct communication with the community, the base group began writing the Kirkby Bulletin for distribution on Tower Hill and producing their own radical newspaper on Thursday evenings in Tower Hill Community Centre. Kirkby Radical Alternative Press (KRAP) sold for two pence in 1977 and promised to be the ‘voice of the community,’ including stories about struggle in Kirkby overall.Footnote126 An article on the front page of KRAP details clashes with the council over road safety barriers. Knowsley Council would not accept responsibility for installing them and referred the residents back to Merseyside County Council, again showing that the organisation of Kirkby was still in disarray even after the town had been established.Footnote127 In response, activists set up barriers and road blocks to prevent access. A meeting was arranged with councillors but the concluding remark was that the activists had been given ‘a bit of sympathy and f-all action.’Footnote128 After the tragic death of four-year-old Alex Simpson in 1977 who was killed by a lorry, the women in Big Flame campaigned for road safety initiatives with the council. The council responded by issuing leaflets and providing education to school children the meaning of road signs that did not even exist on the Tower Hill estate. The BF newspaper interpreted the leaflets as placing the blame firmly back with parents for the road deaths, and reported that zebra crossings, school bus stops and safety barriers had all been requested by BF women and activists, but all requests had been refused or put back.Footnote129 BF activists on Tower Hill expressed their anger at this, relating this to the exploitation of housewives once more, as the council shifted the responsibility back to them. The BF newspaper reported that the Chief of Merseyside County Council remarked that there should be ‘greater parental control,’ to prevent further road deaths.Footnote130 Ultimately, for the women on Tower Hill, this was all part of the exploitation of the housewife that had resulted in the Kirkby rent strike and was ongoing in community activism. However, the list of demands that furnished the front page and were clear: metal safety barriers to be installed around the estate, crossings and patrols, speed limit signs, more play facilities and amenities for the children.Footnote131 Eventually, their perseverance would win them all of these things for Kirkby.Footnote132

The Big Flame leaflet ‘Notes on a Community Struggle,’ produced by the base group documents activism after the rent strike, revealing the endurance and relevance of Big Flame politics. ‘If anything happens on the estate, we get in touch to see what help is needed and to see if it can be linked with other struggles.’Footnote133 Even after the rent strike, there were still community struggles that BF women were involved in with the same politics and commitment.Footnote134

Together, in 1978 Christine Davidson and other activists created the Flat-dwellers Association as they were still housed in Tower Hill’s sub-standard flats, which Christine after described as a ‘ghetto within a ghetto.’Footnote135 Following a gas explosion in one of the main tower blocks in Tower Hill, families were sent to live in the community centre. The full extent of the criminal town planning of Kirkby was revealed as a lack of fire safety and alarms was noted in the building.Footnote136

Tower Hill flats were eventually demolished, unfortunately causing chaos and damaging houses nearby resulting in further disruption, affecting forty-seven people and costing over £100,000 damage.Footnote137 The imposing tower blocks were as damaging in their destruction as they were in their conception. The community organised pickets to stop the explosions continuing until safety measures were put in place. Activists held firm, preventing workers from crossing a picket line and forcing the council to act.Footnote138

Conclusion

Tower Hill needn’t be seen as a huge defeat. It lasted a fucking long time and involved good things. It’ll mainly be a defeat if everyone’s passive and demoralised as a result, if continuity is broken, and if the experience isn’t spread round the working class as a whole. So we have to work out ways forward. Within BF this shouldn’t be left to the base group ‘specialising’ in community struggle. It’s a task for us all.Footnote139 (BF Tower Hill Base Group Leaflet 1974)

The base group model was a crucial part of Big Flame’s organisation and enabled them to embed themselves within working class life and experience. Former Big Flame activist, Nick Davidson, explained the significance of this approach.

We weren’t forming the line; we were filtering what was going on to create the line. Base groups could do that. The idea that you were on the outside, listening to what was going on inside and you reflected back inside what they were thinking but didn’t know they were thinking.Footnote140

Nick’s description revolved around proximity, figurative and literal, as activists worked as outsiders on the inside of estates, becoming close to residents, accessing their experience, and documenting their struggle and their own experience as activists. These spaces were used by members to observe and engage with people in the community to reimagine revolution in everyday spaces and challenge all aspects of ‘ordinary living’ using a feminist approach.Footnote141 These initiatives, as well as having a socio-psychological impact on the activists and the Left more broadly, also formed part of what was to be the ‘personal and collective liberation’ which Gerd-Rainer Horn outlined as a key legacy of 1968 New Left and Far Left movements.Footnote142

The material presented here has demonstrated that the Tower Hill Big Flame base groups under discussion focused, in print and on the estates, on working-class housewives using the key experiences and discourses around women as mothers, wives and carers of the home to engage with women initially and then to challenge these assumptions. Key feminist ideas were discussed in and around the estate as they challenged the cost of living, the state of housing, and services available. By documenting struggles beginning at the private point of the home and extending to the public spaces within the community and workplace settings, Big Flame aimed to blur the boundaries between these spaces to draw working-class struggles together, empowering the working-class housewife as a ‘worker’ become active on the ‘second front.’Footnote143 Furthermore, by living on the estates, Big Flame members documented their own private experience as activists and women on the estate, exploring their hidden labour as activists in self-published texts. Complex layers of emotional labour are shown as they made friends on the estates, created close relationships with people inside and outside of Big Flame and faced the challenge of intervening in the private space of the home and interconnected public spaces around the estates. With their focus on the involvement of women in sharing the work of shopping and budgeting, as well as providing a meeting-place for women on the estate in Kirkby, Big Flame added to these ‘new spaces for sisterhood’ that emerged across Europe in this period.Footnote144

Pete Ayrton, who was involved with several Big Flame groups from 1974, explained how interventions on housing estates worked, acknowledging his own experience as an outsider on a Manchester housing estate, expressing hope at the impact of his involvement.

You’re not actually part of the estate so obviously your experiences are different from the people on the estate, but you have to believe that you can be a useful support and facilitator and get on with it and hope that your organising and organisation is appreciated.Footnote145

Despite the difficulties in class and gender sometimes encountered, the base group was able to use their position on the housing estates to access the experience to provide support to working-class feminist struggles from the inside.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kerrie McGiveron

Kerrie McGiveron is a PhD candidate at the University of Liverpool. Her PhD thesis is entitled ‘What is Big Flame, uncovering an internationalist socialist feminist organisation.’

Notes

1 Big Flame, ‘Housework, a Long Way to Go yet’, 1978, Salford, Working Class Movement Library, ORG/FLAME. Box 2.

2 Susan Stall and Randy Stoecker, ‘Community Organizing or Organizing Community? Gender and the Crafts of Empowerment’, Gender and Society 12, no. 6 (1998): 729–56. These ideas from the nascent WLM were discussed widely in popular feminist publications Spare Rib, Shrew and Red Rag encouraging debate in women’s groups over childcare, housework, housing, consumption and the cost of living.

3 Gerd-Rainer Horn, The Spirit of ‘68: Rebellion in Western Europe and North America, 1956–1976 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007).

4 Geoff Eley, Forging Democracy: The History of the Left in Europe, 1850–2000 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 32.

5 Daphne Spain, Constructive Feminism: Women’s Spaces and Women’s Rights in the American City (New York: Cornell University Press, 2016).

6 Lucy Delap, ‘Feminist Bookshops, Reading Cultures and the Women’s Liberation Movement in Great Britain, c. 1974–2000’, History Workshop Journal 81, no. 1 (2016): 171–96, 171.

7 Christine Wall, ‘Sisterhood and Squatting in the 1970s: Feminism, Housing and Urban Change in Hackney’, History Workshop Journal 83, no. 1 (2017): 79–97.

8 Leslie Sklair, ‘The Struggle Against the Housing Finance Act’, in The Socialist Register, ed. R. Miliband and J. Saville (1976), 250–92, 274.

9 Big Flame, ‘Wages for Housework Is Not Enough but Necessary’ (May 1976), reproduced at https://bigflameuk.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/hwkcd2.pdf (accessed July 17, 2020).

10 Sklair, ‘The Struggle Against the Housing Finance Act’, 250.

11 Joe Moran, ‘Imagining the Street in Post-war Britain’, Urban History 39, no. 1 (2012): 166–86, 166.

12 Eleanor Jupp, ‘Home Space, Gender and Activism: The Visible and the Invisible in Austere Times’, Critical Social Policy 37, no. 3 (2017): 348–66.

13 Dave Welsh, interview with author 31st August 2019.

14 Neil Gray, ed., Rent and Its Discontents, A Century of Housing Struggle (London: Roman and Littlefield, 2018), 5.

15 Stall and Stoecker, ‘Community Organizing or Organizing Community?’, 729–56.

16 Jupp, ‘Home Space, Gender and Activism’, 348–66.

17 Class as a historical category has been shown to be highly significant in the shaping of twentieth-century history, but, as Selina Todd has shown, it is only by focusing closely on the experience of class that we can offer our analysis. See Selina Todd, ‘Class, Experience and Britain’s Twentieth Century’, Social History 39, no. 4 (2014): 489–508.

18 Todd, ‘Class, Experience and Britain’s Twentieth Century’, 489–508.

19 Joan W. Scott, ‘Language, Gender and Working-Class History’, in First Class, ed. P. Joyce (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 154–61, 159.

20 Penny Summerfield, ‘Culture and Composure: Creating Narratives of the Gendered Self in Oral History Interviews’, Cultural and Social History 1 (2015): 65–93, 89.

21 Lucy Delap, Feminisms: A Global History (London: Pelican, 2021), 20–2.

22 R. Bradbury, ‘New Ideas in Liverpool’s Biggest Housing Venture’, Liverpool Daily Post, October 29, 1953, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970–1976. KB1.

23 Big Flame, ‘Notes on a Community Struggle’, Big Flame, Women’s Struggle Notes, 1975, Personal archive of K. McDonnell.

24 Janice Marks, interview with author, 29th January 2021.

25 Nick Davidson, interview with author, 25th September 2019.

26 Norman Rankin, ‘Social Adjustment in a Northwest Town’, in Migration and Social Adjustment, Kirkby and Maghull, ed. K.G. Pickett and D.K. Boulton (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1974), 10.

27 Colin Ward, Housing, an Anarchist Approach (London: Freedom Press, 1976), 168.

28 Lynn Abrams, Ade Kearns, Barry Hazley, and Valerie Wright, Glasgow High-Rise Homes, Estates and Communities in the Post-War Period (London: Routledge, 2020).

29 David Martin Muchnick, Urban Renewal in Liverpool, A Study of the Politics of Redevelopment (London: Bell, 1970), 28.

30 Ward, Housing, an Anarchist Approach, 168.

31 ‘Rents Protest for Premier’, Liverpool Daily Post, April 8, 1965, Liverpool Records Office, 942.729, KIR 1964–1985.

32 Janice Marks, interview with author, 29th January 2021.

33 The socio-economic issues of Kirkby were widely reported both in the media and on film. See Kirkby, Portrait of a Town, R. Gosling and J. Clarke (Granada Television, 1973) Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) KA149/O/Z2.

34 ‘Kirkby: A Children’s Township’, Liverpool Echo, July 17, 1957, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970–1976. KB1.

35 Rankin, ‘Social Adjustment in a North West Town’, 23.

36 Following concerns over high crime and vandalism, a damning police report by Sergeant Norman Chappell was published in 1972. The investigation, which fills two volumes, opens with a quote from Thomas Hardy, warning the reader, ‘if a way to the better there be, it exacts a full look at the worst.’ The report detailed Kirkby’s social and economic malaise covering crime, housing, and unemployment. N.L. Chapple, Kirkby New Town, an Objective Assessment of Social Economic and Police Problems, Vol. 1 (December 1975), ii.

37 John Edwards, ‘It All Looked Great on the Drawing Board but now Kirkby Has Joined the Third World … and Needs Missionaries’, Daily Mail, December 4, 1975, 16–17. Daily Mail Historical Archive, https://link-gale-com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/EE1866671325/DMHA?u=livuni&sid=bookmark-DMHA&xid=e4879749 (accessed April 24, 2022).

38 Daily Mail Reporter, ‘Save Our Children, Say Terror-flat Families’, Daily Mail, October 29, 1973, 12. Daily Mail Historical Archive, https://link-gale-com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/EE1862430794/DMHA?u=livuni&sid=bookmark-DMHA&xid=aeacf0a0 (accessed April 24, 2022).

39 Centre for Environmental Studies (CES) Limited, Urban Resource Centre, Knowsley Metropolitan Council Merseyside County Council, Kirkby: An Outer Estate (Liverpool, 1982), 5, Kirkby, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK), R301.54.

40 Ibid.

41 Correspondent, A., ‘Home News: Builder and Council Men Gaoled for Bribes’, The Guardian (1959–2003), June 10, 1978, https://liverpool.idm.oclc.org/login?url?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/home-news/docview/185979942/se-2?accountid=12117 (accessed April 24, 2022).

42 ‘Jail for Council Men Who Took Bribes’, Daily Mail, June 10, 1978, 9. Daily Mail Historical Archive, https://link-gale-com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/apps/doc/EE1862278378/DMHA?u=livuni&sid=bookmark-DMHA&xid=62accc2a (accessed April 24, 2022).

43 Kirkby Urban District Council, Health and Housing: Agendas and Reports for the Health and Housing Committee Meetings, September 27, 1971, Kirkby, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) KUDC Box 12/1.

44 Liverpool Free Press reporting in 1971 announced that hundreds of thousands of tenants would never claim or receive the rebate that they were owed. Liverpool Free Press, which was written by three Liverpool Echo journalists and promised to be ‘the news you’re not supposed to know,’ were responsible for investigating and exposing the corruption scandal of the development of Kirkby. Liverpool Free Press (August–September 1971), Liverpool Records Office, Class 072 FRE.

45 See Hansard, HC Deb, November 2nd, 1971, column 22 Wilson debated that the fair rents would on average double the rent of council tenants, as well as low successful applications for rent rebates.

46 Sklair, ‘The Struggle Against the Housing Finance Act’, 253.

47 Quoted in Sklair, ‘The Struggle Against the Housing Finance Act’, 253.

48 ‘Council Won’t Raise Rents, Tenants Told’, Kirkby Reporter, July 19, 1972, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970–1976. KB1.

49 ‘One Vote Brings Kirkby Rent Act’, Liverpool Echo, September 12, 1972, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970–1976. KB2.

50 ‘Kirkby Attack on “Crippling Rates”’, Liverpool Echo, November 23, 1971, Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970–1976. KB2.

51 Quoted in C. Couch, City of Change and Challenge: Urban Planning and Regeneration in Liverpool (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), 59.

52 ‘One Vote Brings Kirkby Rent Act’.

53 ‘Rent Strike Threat over Rises’, Kirkby Reporter, September 13, 1972. Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970–1976.

54 Christine Oliver, Tower Hill (unpublished document, 2017). Personal archive of C. Oliver.

55 ‘Liverpool Tenants Say “Rent Rise – Rent Strike”’, Big Flame No. 3 (September 1972), Liverpool, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9.

56 Behind the Rent Strike, Dir: Nick Broomfield (National Film School, 1974), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0anu9hlQ9iA (accessed July 21, 2020).

57 Oliver, Tower Hill.

58 Ibid.

59 Martin Yarnitt, interview with author 25th November 2019.

60 ‘Rent Striker Jailed – Hundreds Demonstrate Outside Walton’, Big Flame, December 1973, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9.

61 ‘A Lion’s Den by Rent Strikers’, Kirkby Reporter, December 12, 1973. Archive Resource for Knowsley (ARK) Rent and Rate Newspaper Archive 1970–1976.

62 ‘Rent Striker Jailed – Hundreds Demonstrate Outside Walton’.

63 Ibid.

64 Behind the Rent Strike.

65 Our own Reporter, ‘Prison Picket Stops’, The Guardian (1959–2003), December 12, 1973, https://liverpool.idm.oclc.org/login?url?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/prison-picket-stops/docview/185615228/se-2?accountid=12117 (accessed April 24, 2022).

66 Sklair, ‘The Struggle Against the Housing Finance Act’, 274.

67 ‘Don’t Let the Missus Do All the Battling’, Big Flame, July 7, 1970, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9.

68 ‘Bendix – How the Workers Took over’, Big Flame, 1972. Reproduced online https://bigflameuk.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/bendix-how-the-workers-took-over.pdf (accessed August 14, 2020).

69 Geoffrey Whiteley, Northern, Labour Correspondent, ‘600 Workers Stage Factory Sit-in’, The Guardian (1959–2003), January 6, 1972, https://liverpool.idm.oclc.org/login?url?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/600-workers-stage-factory-sit/docview/185544226/se-2?accountid=12117 (accessed April 24, 2022).

70 ‘Bendix – How the Workers Took over’.

71 ‘We’ll Go on Fighting Because We Have to – Kirkby Women Speak’, Big Flame, September 1972, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9.

72 Jenny Fortune, Interview with author 12th June 2017.

73 Kim Singleton, Thousands Say, We Won’t Pay! Merseyside Tenants in Struggle, 1968–1973 (Saarbrucken: LAP Lambert, 2012), 174.

74 ‘We’ll Go on Fighting Because We Have to – Kirkby Women Speak’.

75 Sklair, ‘The Struggle Against the Housing Finance Act’, 274.

76 Janice Marks, interview with author, 29th January 2021.

77 Horn, The Spirit of ‘68, 162.

78 Delap, ‘Feminist Bookshops, Reading Cultures and the Women’s Liberation Movement’, 171.

79 See Silvia Federici, Wages Against Housework (Bristol: Falling Wall Press, 1975), 8. Federici argued that for some women, identifying as a housewife might be a ‘fate worse than death,’ due to the perceived powerless of the role. Federici advocated embracing the identity of the housewife and to subvert the role that capitalism intended for it to play. Recognising the escape of housework as a ‘delusion’ she concluded that ‘Until we recognise our slavery, we cannot recognise our struggle against it.’

80 ‘We Won’t Pay: Women’s Struggle on Tower Hill’, Big Flame, 1975. Reproduced online https://bigflameuk.files.wordpress.com/2009/05/tower-all.pdf (accessed August 19, 2020).

81 Big Flame, ‘Report on Big Flame 1973’, Personal archive of Kevin McDonnell.

82 See Federici, Wages Against Housework, 8. Federici argued that for some women, identifying as a housewife might be a ‘fate worse than death,’ due to the perceived powerless of the role. Federici advocated embracing the identity of the housewife and to subvert the role that capitalism intended for it to play. Recognising the escape of housework as a ‘delusion’ she concluded that ‘Until we recognise our slavery, we cannot recognise our struggle against it.’

83 Big Flame, Women’s Struggle Notes, No. 4, reproduced online at https://archive.leftove.rs/documents/EBH (accessed February 4, 2022).

84 Big Flame, ‘Tower Hill Base Group’, Libertarian Newsletter 4, January 1974, 10. Personal archive of K. McDonnell.

85 Janice Marks, interview with author, 29th January 2021.

86 One of these original pamphlets is now held at the Liverpool Museum as part of a display detailing the rent strike. None of the far-left organisations in the area are credited.

87 ‘We Won’t Pay: Women’s Struggle on Tower Hill’.

88 Ibid.

89 Spain, Constructive Feminism, 2.

90 ‘Report on Big Flame 1973’. In the 1950s and 1960s, campaigns for social spaces on Merseyside for children were started by women, but often controlled by men and it was not until the 1970s that these spaces began to be run autonomously by women. See Krista Cowman, ‘“The Atmosphere is Permissive and Free”: The Gendering of Activism in the British Adventure Playgrounds Movement, ca. 1948–70’, Journal of Social History 53, no. 1 (2019): 218–41.

91 ‘Report on Big Flame 1973’.

92 Behind the Rent Strike, Dir: Nick Broomfield.

93 Ibid.

94 ‘We Won’t Pay: Women’s Struggle on Tower Hill’.

95 Sarah Stoller, ‘Forging a Politics of Care: Theorizing Household Work in the British Women’s Liberation Movement’, History Workshop Journal 85, no. 1 (2018): 95–119.

96 Helen McCarthy, ‘Women, Marriage and Paid Work in Post-war Britain’, Women’s History Review 26, no. 1 (2017): 46–61.

97 Christina Rousseau, ‘The Dividing Power of the Wage: Housework as Social Subversion’, Atlantis 37, no. 2 (2016): 238–52, 241.

98 Maud Anne Bracke, ‘Between the Transnational and the Local: Mapping the Trajectories and Contexts of the Wages for Housework Campaign in 1970s Italian Feminism’, Women’s History Review 22, no. 4 (2013): 625–42.

99 Silvia Federici, ‘Introduction in Historical Perspective in Wages for Housework’, in Wages for Housework: The New York Committee 1972–1977: History, Theory, Documents, ed. S. Federici and A. Austin (New York: Autonomedia, 2017), 18.

100 Federici, Wages Against Housework, 8.

101 See Caroline Freeman, ‘When Is a Wage Not a Wage?’, in The Politics of Housework, ed. E. Malos (Cheltenham: New Clarion Press, 1980), 142–8; Sheila Rowbotham, ‘The Carrot, The Stick and the Movement’, in The Politics of Housework, ed. E. Malos (Cheltenham: New Clarion Press, 1980), 14; Ros Delmar, ‘Sexism, Capitalism and the Family’, in Papers from the Women’s Movement, ed. S. Allen, L. Sanders, and J. Wallis (Leeds: Feminist Books, 1974), 229–43, 237.

102 CES Limited, Kirkby: An Outer Estate, 7.

103 Big Flame, ‘Introduction to Liverpool Big Flame on Wages for Housework’, 1976, 1 reproduced at https://bigflameuk.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/hwkcd1.pdf (accessed April 12, 2020).

104 Ibid., 6.

105 Big Flame, ‘Contribution to the Open Conference from Big Flame Women’s Commission’ (1977). Salford, Working Class Movement Library, ORG/FLAME. Box 2.

106 Big Flame, ‘Wages for Housework Is Not Enough’, 3.

107 Ibid.

108 Nick Davidson, interview with author, 25th September 2019.

109 Janice Marks, interview with author, 29th January 2021.

110 Janice Marks, interview with author, 29th January 2021.

111 Big Flame, ‘Housework: Its Role in Capital Relations of Production and in Revolutionary Strategy’, 1977, reproduced at https://bigflameuk.files.wordpress.com/2009/10/hwksm.pdf (accessed June 12, 2021).

112 Lynn Abrams, ‘Heroes of Their Own Life Stories: Narrating the Female Self in the Feminist Age’, Cultural and Social History 16, no. 2 (2019): 205–24.

113 Jupp, ‘Home Space, Gender and Activism’, 348–66.

114 Stall and Stoecker, ‘Community Organizing or Organizing Community?’, 732.

115 Big Flame, ‘A Week in April’ (1977) Salford, Working Class Movement Library, ORG/FLAME. Box 4.

116 Ibid.

117 Ibid.

118 Big Flame, ‘A New Struggle Notes and the Need for a Changing Perspective on Women’, 1976, reproduced at https://bigflameuk.files.wordpress.com/2010/07/new-struggle-notes.pdf (accessed July 23, 2020).

119 Ibid.

120 Ibid.

121 Jenny Fortune, interview with the author: 12th June 2017.

122 Jenny Fortune, interview with the author: 12th June 2017.

123 Big Flame, ‘Women’s Group Report for Liverpool General Meeting’, 1975, Salford, Working Class Movement Library, ORG/FLAME, Box 2.

124 Big Flame, ‘Wages for Housework Is Not Enough’.

125 Big Flame, ‘Tower Hill Base Group’, 10.

126 Kirkby Radical Alternative Press (KRAP), June 1977. Personal Archive of Ritchie Hunter.

127 ‘Diary of Events and Non-Events’, Kirkby Radical Alternative Press (KRAP), June 1977. Personal archive of Ritchie Hunter.

128 Ibid.

129 ‘Kirkby: ‘Barricades Against the Cuts’, Big Flame, December 1977, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9.

130 Ibid.

131 ‘Demands’, Kirkby Radical Alternative Press (KRAP), June 1977, Personal archive of Ritchie Hunter.

132 Email correspondence with C. Oliver 5th June 2017.

133 Big Flame, ‘Notes on a Community Struggle’, in Women’s Struggle Notes, 5 (June–August 1975), Personal archive of K. McDonnell.

134 Email correspondence with C. Oliver 5th June 2017.

135 Oliver, Tower Hill.

136 Ibid.

137 ‘Cool-it Plea to Flats Blast Victims’, Liverpool Echo, May 18, 1982, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9.

138 J. Shaughnessy, ‘Kirkby Pickets on Full Alert’, Liverpool Echo, June 8, 1982, Liverpool Records Office, M329 COM/36/9.

139 Big Flame, ‘Tower Hill Base Group’, 8.

140 Nick Davidson, interview with author, 25th September 2019.

141 Eley, Forging Democracy, 344.

142 Horn, The Spirit of ‘68, 1.

143 See Cowman, ‘The Atmosphere is Permissive and Free’, 218–41.

144 Stoller, ‘Forging a Politics of Care’, 95–119.

145 Pete Ayrton, interview with author, 21st September 2019.