ABSTRACT

This article uncovers the important participation by women in adult education between 1920 and 1945 in Yorkshire. It contributes to the current historiography by using statistical evidence, not previously used, to quantify and analyse the numbers of women and men students participating in adult education. Regional statistics collected by the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA) in Yorkshire and the University of Leeds, show that the number of women students matched and sometimes outnumbered male students attending adult education classes before and during the Second World War. The evidence reinforces the hypothesis that when male students were not present (as in war time) to attend adult education, women students readily filled those student places. This hypothesis indicates that a paradox existed in the world of adult education whereby in theory equal opportunities existed for men and women to access adult education, but structural barriers remained in place that limited the ability of women to attend classes. The article argues that structural barriers were a distinctive element in making adult education realistically accessible to women following their enfranchisement in 1918 and 1928 as equal citizens. It encourages a rethinking of the relationship between gender, educational opportunities and citizenship in the early twentieth century.

Introduction

The extension of the franchise to all qualified women over the age of twenty-one [*sic] years of age will bring responsibilities of citizenship to a very large number of young wives and mothers, and if they are to be a strength, not a weakness, to the political life of the nation, a determined effort must be made to cater for their special educational needs. (J.H.B Masterman, 1920)Footnote1

This article will help re-balance the historiography by drawing attention to the presence of women in the world of adult education from c.1920 to 1945. Greater knowledge of the presence of women in adult education will inform a new understanding of how and why women participated as newly enfranchised citizens in a world where the boundaries between the domestic and public spheres were becoming blurred. The impact of the First World War gave women opportunities to enter the world of work and contribute to the war effort in meaningful ways. Women took up employment in roles previously only occupied by men. This critical development proved women to be equal citizens, and this led to a re-thinking of the role of women in society at large. In the world of adult education, the idea of women as equal citizens who participated in several spheres became more accepted and as a result adult education was re-shaped to accommodate women who existed simultaneously at work and at home.

Following their enfranchisement women were essentially learning how to be equal citizens and attending adult education was a significant part of that process. This approach leads to new ways of thinking about how citizenship works at ground level. The main analysis is based on historical statistics collected by the WEA (Yorkshire District) and the University of Leeds that show evidence of women students participating in adult education at a regional level. The significance of the evidence used is that it provides a snapshot of student participation in adult education in a sizeable region in Great Britain. It also shows how historical statistics can be used to investigate the participation of men and women in adult education, and the questions those statistics raise about access to adult education from a gender perspective.

Women and adult education—the context

Here, I argue that the participation of women in adult education occurred in a political framework that accommodated citizenship in favour of women’s rights, duties and interests. In this framework the concept of women as citizens took priority over that of women as feminists, the difference being that feminism addressed the broader structural inequalities that women faced in contrast to the women’s movement for citizenship, which focused solely on acquiring the right to vote on the same basis as men. Caitriona Beaumont’s research supports this argument, analysing how conservative women’s organisations including the National Federation of Women’s Institutes campaigned for the rights of women as enfranchised citizens.Footnote4 Such organisations avoided an association with overtly feminist ideology because they perceived it to be destructive to the sanctity of domestic life, encouraging women to move into the public sphere of work to the detriment of their families. However, the reality, as Beaumont observes, was that feminist societies throughout the inter-war period ‘ … never challenged traditional gender roles within the family and accepted that the majority of women would choose to work at home as wives and mothers.’Footnote5 This insight shows that the idea that domesticity formed a vital part of a woman’s life was generally accepted and desired by many women of the interwar era. This is not at all to say that women did not care about the persistence of the profound political, social, and economic inequalities affecting them. Rather, the strategy of how to correct these inequalities changed from one based on the language of feminism to one based on the language of democratic citizenship, initiating a debate about how to judiciously exercise political rights and duties. Anne Logan emphasises this approach in her study on the impact of the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, 1919, which admitted women to the magisterial benches. She argues that ‘entry into the magistracy was central to the establishment of women’s claims to citizenship because it could be presented as both the right [sic.] of enfranchised women and also as a fundamental duty [sic.] of the individual citizen.’Footnote6

Logan’s and Beaumont’s scholarship frames this approach to understanding women in the world of adult education by building and extending the premise that non-feminist apolitical organisations supported women as equal citizens. Adult education organisations, namely the universities and the Workers’ Educational Association (WEA), were firmly non-partisan and non-sectarian in substance and style. As such, in support of citizenship, they offered women from all social and political backgrounds an inclusive space in which to interact, socialise, and educate themselves on their own terms. The lack of an explicit political agenda in adult education as disseminated by the WEA and universities gave women the opportunity to be themselves for themselves rather than placing political or ideological demands on them. It is this aspect of adult education, that makes it unique and worth exploring from the perspective of women as citizens. The WEA focussed on teaching people how to think rather than what to think. This aspect of the delivery of teaching was very important in making education meaningful to a wide range of people, many of whom were not particularly political in their outlook. By placing education in a non-political framework, women students were free to develop their interests to suit their own understanding of how to conduct their lives and be active citizens.

Moving forwards in the historiography, recent research undertaken by Eve Worth shows how women who took educational opportunities as mature students became more empowered and socially mobile in the 1970s.Footnote7 Worth, accepting the premise that women had autonomy to make changes in their own lives, defines female social mobility on the basis of the post-secondary educational qualifications women achieved rather than in terms of a woman’s husband’s occupation and position.Footnote8 In doing so Worth succeeds in discovering how women were empowered by their educational achievements to advance their careers and class position.Footnote9 Worth’s research is insightful because it presents a gendered model of class and social mobility that examines how women followed a different educational route to men in becoming socially mobile at a time when some structural inequalities to accessing education had been dismantled. This research seeks to emulate Worth’s approach by applying the idea of a gendered model to the world of adult education in Yorkshire between 1920 and 1945.

This article builds on current research demonstrating that during the interwar period, organisers of adult education were thinking seriously about how to include women in classes and support them as fully enfranchised citizens. The analysis will support current research by presenting women in the world of adult education as a continuum, whereby women students who had always been present in the world of education gained prominence after their partial and full enfranchisement in 1918 and 1928 respectively. In line with Worth’s research, based on evidence from thirty life history interviews to explain improved access to adult education for women in the 1970s, this research will show how women took up opportunities to engage in adult education when specific barriers to getting access to it were removed.

In the context of the 1970s, the removal of structural inequalities made this possible. The marriage bar was an example of a specific barrier to further education for women. Removing it enabled women to re-enter the job market and to pursue educational qualifications in support of their ambitions for employment. Also, the creation of a new tier of higher education in the form of polytechnics and the Open University, gave those who wished to, more options to return to the world of education as working adults.Footnote10 In addition, adult students returning to education in the 1970s were not compelled to pay fees and in some cases did not need A Level qualifications to take up a place in higher education at some institutions.Footnote11 As a whole, these changes to how higher education was organised made it much more accessible to a wider range of disadvantaged non-standard, entrants, many of whom were women.

My research gives a different perspective of women and adult education to Worth’s because it focusses on the period between 1920 and 1945, well before the creation of the post war welfare state. In addition, it uses evidence from statistics to support the argument that women as newly enfranchised citizens with voting power became a priority group for greater inclusion in adult education programmes. Unlike Worth’s research that draws attention to the opportunities for self-improvement and social mobility for women via adult education in the 1970s, this research seeks to explore the connection between women, democracy, and adult education at a time when women were in the process of learning how to be active citizens.

During the interwar period, the presence of structural inequalities remained firmly in situ. The major change that made adult education accessible to more women during this period was the Second World War. This article argues that it was ultimately the absence of men, many of whom had been conscripted, that made it possible for more women to take up adult education. The outcome of this more detailed approach will show the numbers of women students involved in adult education, their occupations, and the subjects that they studied in tutorial classes provided by the WEA in collaboration with the University of Leeds and how that changed during the inter-war era.

To support the argument that women were able to access adult education to a greater extent in the absence of men, this article first presents an analysis of adult education for women in the broader context of university extension and the WEA. It will then make an analysis of statistics of students by gender collected by the WEA in Yorkshire and the extra mural department of the University of Leeds to show that women were more active than previously thought in accessing adult education at a time when educational opportunities for women were limited. The significance of this evidence and the knowledge it creates is that it highlights an intersection between women, adult education and citizenship that has been overlooked. The world of adult education offered women important opportunities to explore their ability to be active citizens at home and in the public sphere.

Adult education—the broader context

In the early twentieth century the world of adult education was a community sphere in which women could exercise their agency irrespective of their traditionally assigned roles as wives, mothers, and workers. As Valerie Yow notes women attended adult education as a way of fulfilling their personal intellectual desires rather than as a way of contributing to different causes. This attitude is best summed up by a quote made by a female student attending classes organised by the National Council of Labour Colleges who declared to Ellen Wilkinson ‘I’ve washed up for Socialism, I’ve washed up for Disarmament, but I’m not going to wash up for Education, because I want to be in class and not at the sink.’Footnote12 The picture that emerges of the world of women is one of interconnectivity between different spheres of activities—domestic, work, community, public service, self-improvement, and leisure. No one sphere existed in exclusion of another, instead they overlapped to a greater or lesser extent. Knowing more about women in the world of adult education will help inform our understanding of the connections between the range of different spheres available to women during the first half of the twentieth century. This will help inform new approaches to women’s history that reflect the ‘total’ woman rather than the woman ‘split’ between carer, marital, home maker and work-place responsibilities.

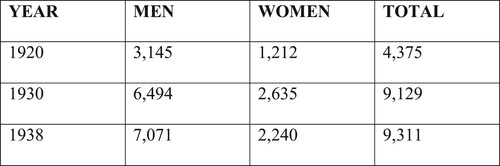

By 1900 serious inequalities in education continued to exist for both men and women. The 1870 Elementary Education Act and subsequent legislation made primary education free and compulsory up to the age of ten during the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century the 1918 Education Act made education compulsory up to the age of fourteen. However, secondary education for many remained remote and access to higher education remoter still. Evidence of this can be seen in which displays the numbers of male and female students obtaining first degrees from universities in 1920, 1930 and 1938.

Figure 1. Students obtaining university first degrees, UK (1920, 1930 and 1938). Source: Adapted from Paul Bolton, Education: Historical Statistics, House of Commons Library.Footnote50

As can be seen the numbers of men and women obtaining first degrees during the interwar period were low, especially for women. Wealth, ultimately, irrespective of gender, pre-determined the level of education an individual could access. For women an added barrier was based on gender discrimination with universities remaining accessible only to men until Girton and Newnham College, Cambridge University, welcomed female only students in 1869 and 1871 respectively.

The British adult education movement in the form of university extension, established by James Stuart and others in 1871 and the WEA founded by Albert Mansbridge in 1903, shared the aim of disseminating higher education to greater numbers of men and women who would otherwise never be able to access any education beyond primary level.Footnote13 However, university extension without subsidisation was unaffordable to many working-class students, already challenged daily for time and money. For example, typically a twelve-meeting lecture university extension course cost seventy pounds which meant that even if 300 students attended, tickets were still costly for some at five shillings each thus pricing out many low paid working-class people.Footnote14

Mansbridge established an effective working partnership between universities and working-class organisations that coordinated and delivered university extension education to a greater number of working-class men and women than ever before. This was achieved by creating university extension joint committees on which working class organisations such as co-operative societies, trade unions and the WEA were strongly represented. An example of how this worked in practice is the founding of the York WEA branch in 1917 following a ‘Delegate Conference called by the Education Committee of the York Equitable Industrial Society’. The Conference was organised to plan for post war industrial reconstruction and was attended by almost two hundred delegates from trade unions and other related groups. The delegates expressed a wish to have a tutorial class on ‘Problems arising as a result of the War’. To this end the Executive Committee of the York Branch was elected in June 1917 by the delegates to organise WEA classes in York.Footnote15 What this shows is the bottom-up nature of the organisation of WEA tutorial classes, whereby local people associated with the labour movement took the initiative to establish a class on a topic of their choice via the WEA. In effect Mansbridge helped shift control of adult education resources—university extension—from the universities (who co-operated in this enterprise) to working class organisations and students. The WEA described itself as ‘impartial, unsectarian and democratic’ and disseminated non-vocational adult education in the liberal arts taught from multiple perspectives to encourage students to think in an independent, critical, and impartial way. It did not explicitly make women’s rights or issues a priority. Rather, it supported Labour Party policies to improve universal access to education and aimed to promote active democratic citizenship. Tom Hulme’s research identifies the impact of the First World War, the extension of the franchise and the influence of idealism as key factors that supported this trend in adult education.Footnote16

The WEA became the largest provider of adult education during the inter-war period. In 1919–20 the WEA nationwide ran a total of 557 classes with a total of 12,438 students. In 1941–42 the total number of classes the WEA ran increased to 3288 with a total of 58,582 students.Footnote17 A wide range of students from different social backgrounds made up the student body of the WEA. Details of past and present students engaged in some form of public service in England and Wales are listed in The Adult Student as Citizen, a pamphlet published by the WEA in 1938 to demonstrate the impact of adult education on citizenship. Hulme’s research provides a case study of how the WEA disseminated education for citizenship in Manchester that corresponds closely with the themes of The Adult Student as Citizen.Footnote18 In the preface of The Adult Student as Citizen R.H. Tawney argued that the WEA were committed to public service stating that ‘WEA students take their full share of public responsibilities’.Footnote19 The total number of individuals listed is 2174. Details of their names, their position in public service and their geographical location are given in the pamphlet. Fifteen of the individuals listed were MPs and included William Dobbie (MP, York), John Arnott (MP, Leeds) and James Dobbs (MP, Leeds). 356 of the students named were city and borough councillors.Footnote20 Of the 2174 students listed in the pamphlet 335 were women. Little was known about the biographies of these women, but my research provides information about two of them—Bridget Bertha Quinn (1873–1951), a Leeds City Councillor (1929–1943) and Jeanine Mercer (1880–1969), (neé Jane Forster) a York City Councillor and Magistrate.Footnote21 Quinn, a militant suffragette, organised the Leeds branch of the National Tailors and Garments Workers from 1915 to 1940.Footnote22 She was also a member of the Labour Party from 1918. The many issues that Quinn campaigned on included education, air pollution, poor housing, and inadequate poor relief. A controversial and lively councillor who could sometimes hold exaggerated views in comparison to her socialist peers, Quinn represented the sort of active citizenship and public service that the WEA wished to nurture.

Mercer, in contrast with Quinn’s exuberant approach to public service, maintained a much lower but equally effective profile as one of the first women in Great Britain to become a magistrate in 1924. She too, like Quinn, was involved in several areas of public service and served on the Insurance Committee from 1917, a precursor to the NHS and then as committee member on the York Health Executive Council from 1948 to her retirement in 1964. Mercer was a schoolteacher and in addition to her work in health care spent forty five years as secretary to the York Co-operative Society Education Committee. For a short period, she also represented Scarcroft Ward on York City Council.Footnote23 These examples show that a significant minority of women students of the WEA were identified as active citizens by their work in public service. The work these women did included being members of maternity and child welfare committees, city councillors, magistrates, parish councillors, school, and hospital governors.Footnote24

Zoë Munby argues that the WEA recognised that women were important to include and support as part of its mission to disseminate higher education to the working class. To this end in 1907 the national committee of the WEA ‘ … invited a group of influential women to form a women’s advisory committee’(WAC).Footnote25 This was significant because it shows that the WEA, a perhaps unintentionally male oriented organisation, took specific action to include women in its management structure to adapt itself to the educational needs of women students. The WAC functioned to ‘ … discuss the education of working women with a view to making recommendations to the executive’.Footnote26 It advised the national committee on the education of women workers until 1915. It also lobbied successfully, via motions to the national executive, for WEA branch committees to include more women as ‘ … representatives of women’s organisations, and to promote the formation of women’s committees and sections.’Footnote27 The WAC adopted this strategy with a focus on including women as members on WEA committees, a strategy that reflected Mansbridge’s approach to creating joint committees which included members from working class organisations.

Munby shows that the WAC’s campaign to increase female representation in the WEA was very successful—‘by 1914–15 there were thirty four branches which had either women’s committees or secretaries, out of a total of 179 branches.’Footnote28 In addition there were ‘seventy six women’s classes, numerous study circles and lectures—there were fifty women’s lecture programmes in London alone, consisting of 130 individual lectures.’Footnote29 The above are reported figures and it is likely that unreported work taking place in women’s education by the WEA was much greater. The WAC may have been a victim of its own success as in 1915 it was disbanded by the WEA executive because local women’s organisations were carrying out much of its work. Of note here is the London women’s committee which prevailed until the advent of the Second World War.Footnote30

The issue of how the WEA could widen participation among women in adult education fell into the background but re-emerged as a concern in 1925. At a conference in April 1925 the Women’s Committee of the London District discussed ‘ … how best the WEA could help stimulate and to meet the educational demands of women workers.’ Labour M.P. Margaret Bondfield chaired the conference attended by forty delegates ‘ … representing the Women’s Co-operative Guilds, the Women’s Sections of the Labour Party, and Trade Unions with women members in London’.Footnote31 The consensus of the conference was that ‘ … there should be more co-operation in educational matters between women’s organisations, and between these bodies and the WEA.’Footnote32 The Women’s Education Committee (WEC) was set up with two representatives from the London District WEA, the Southern Co-operative Education Association and the Women’s Advisory Committee of the London Labour Party.Footnote33 One representative each from sixteen trade unions all with women members in London were also on the committee. The reason put forward for why the WEC was formed was because:

women workers have so far taken a much smaller part than they should in the work of the WEA, and the purpose has been throughout to bring them to a greater extent into educational activities, by helping to meet their special needs and difficulties.Footnote34

women are not so well organised as men, [sic] and are less used to the public discussion of questions of general interest—thus they frequently feel nervous about attending classes, and, when they do attend, take little part in discussion.Footnote36

The report gives an insight into the specific problems that women faced in the world of adult education. It implies that the organisation of classes as well as subjects taught by the WEA were much more tailored to the demands and interests of working men rather than their female equivalents. Also, the report highlighted the gender divisions between men and women with respect to class subjects and general ability. To draw more women into adult education, the WEA would have to start providing classes that taught female friendly topics and accommodated the real lives of women. Despite the implications of gender divisions in the report, the committee stated that it did not:

aim at creating a division between men and women within the WEA: it believes in a common educational activity. But it also believes that, to bring women effectively into this common activity, a great deal of pioneering work must be done, of a kind which, for the time being, deliberately takes the woman’s point of view.Footnote38

The WEA formed a successful partnership with the Women’s Co-operative Guild (WCG) to deliver education to women workers. The female-friendly programme they devised included ‘women’s subjects’ including hygiene, home nursing and embroidery’ that reflected traditional female roles locating women firmly in the domestic sphere.Footnote39 Margaret Macmillan, a firm advocate of women’s education, questioned this approach, which appeared to consolidate the domestic role of women rather than using education to expand their horizons. In 1909, Macmillan in The Highway (the WEA’s journal) argued that working-class girls were limited only by their economic circumstances when compared to girls from the upper classes. The working-class girl’s challenge was to change her circumstances, not possible to do if she accepted them.Footnote40

However, these classes, oriented towards domestic life, were not prescribed but designed for women who did not necessarily wish to embark on a programme of abstract higher learning that had little to do with the very practical aspects of their daily lives. An argument that supports the idea that women students themselves shaped the curriculum to reflect domestic aspects of their lives is that the WEA did not impose subjects for study on students, but rather negotiated with students about what they desired from education. If the resources to hand allowed, the WEA tailored courses and classes to teach subjects that students identified as important to learn about. Thus, accepting this rationale, women who took up classes in cookery and embroidery did so because they wanted to. Furthermore, Munby argues that the very act of attending such classes, domestic or otherwise, was the first step towards creating a community outside the home and enabling women students to explore what education could offer them.Footnote41 This, perhaps even more than the subjects taught in class, may have had a significant impact in giving women opportunities to form social networks outside the family and home environment.

In addition to classes that focused on domestic subjects, the WEA disseminated education to women in literature, drama, music, and dance. These classes flourished during the interwar years and gave women opportunities to exercise their creativity outside the domestic environment with like-minded people. Such classes opened up a new world of fun and leisure to women who may otherwise have been confined completely to the world of domesticity. The WEA may not have broken the mould by using education programmes to directly challenge structural discrimination against women, but they did offer women spaces in which to explore their individuality, and form networks outside the home. WEA education programmes for women were in this way geared towards empowering them within their comfort zones, building their confidence and affirming their status as active citizens.

Women students in the WEA—Yorkshire

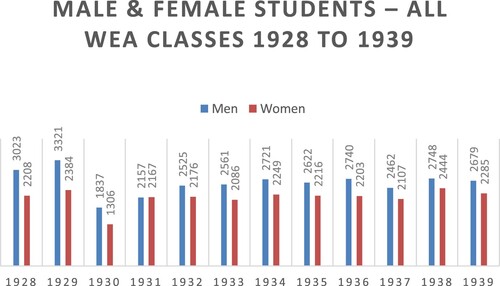

Information about the numbers of women students who attended WEA classes will help clarify the impact of the WEA on the education of women. From its foundation the WEA maintained statistics of the number of students attending tutorial classes in centralised annual reports that covered all WEA districts nationwide. The percentage of women students attending tutorial classes rose from 9% in 1910–11 to 32% in 1919–20.Footnote42 From 1919–20 statistics of student occupations were maintained as well as attendances to all other classes and courses in addition to the tutorial classes. Munby reports that the ‘WEA published student numbers for all provision and separated out men and women only for a brief period from 1954–55 to 1965–66’.Footnote43 Munby’s search for women students in the WEA used the WEA annual national reports that give national numbers of students collected by each WEA district. However, as Munby suggests, district and local archives may hold sources that reflect richer information about students attending WEA classes. For example, the WEA Yorkshire District and Yorkshire District North Annual Reports give details of the number of students, their gender and their occupation,Footnote44 attending adult education classes organised by the University of Leeds and the WEA in Yorkshire.Footnote45 I will present and analyse some of the statistics on male and female students that the WEA Yorkshire District and Yorkshire District North Reports provide us with in . I have interpreted the statistics very simply to compare the number of women and men students attending adult education courses provided by the WEA and the University of Leeds and then to identify what courses men and women enrolled on and the years they attended.

Figure 2. Male & female students—all WEA classes 1928–1939. Source: West Yorkshire Archive Service (WYAS) WYL6691/2 & TUC, /4/2/1/2 WEA Yorkshire District & Yorkshire District North Annual Reports (1928–1939).Footnote51

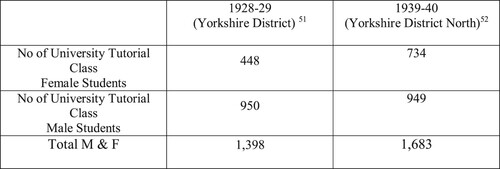

Figure 3. Male & female university tutorial class students (1928–29 and1939–40). Source: WYAS, WYL6691/2 & WYL669/1/3. WEA Annual Reports Yorkshire District & Yorkshire District North.

Note:51 WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD 14th AR (1928), 3.52 WYAS, WYL669/1/3, WEA YD North 25th AR (1939), 8. Only the total number of male and female university tutorial class students are represented in .

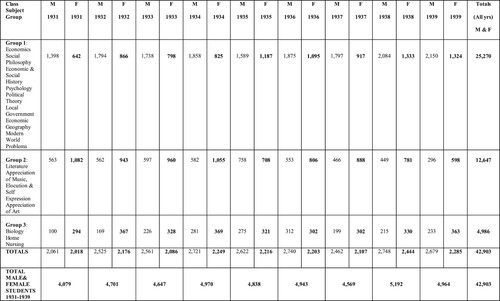

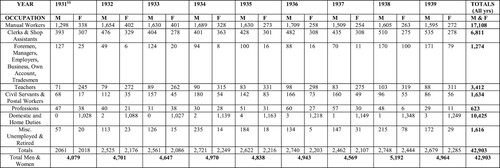

Figure 4. WEA Yorkshire District North: male & female students 1931–1939 (All Classes – university tutorial, extension, one year & terminal). Source: WYAS, WYL 669 1/3 & TUC, /4/2/1/2. WEA Yorkshire District North Annual Reports (1932–1939).Footnote52

Figure 5. WEA Yorkshire District North: male & female students by occupation 1931–1939 (All Classes). Source: As for .

Note:55 1931 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, YD North 17th AR (1931), 4.; 1932 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, YD North 18th AR (1932), 6.; 1933 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, YD North 19th AR (1933), 5.; 1934 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, YD North 20th AR (1933), 4.; 1935 – TUC, /4/2/1/2, YD North 21st AR (1935), 6.; 1936 – TUC, YD North 22nd AR (1936), 7.; 1937 – TUC, YD North 23rd AR (1937), 16.; 1938 – TUC, YD North 24th AR (1938), 7.; 1939 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, YD North 25th AR (1939), 8.

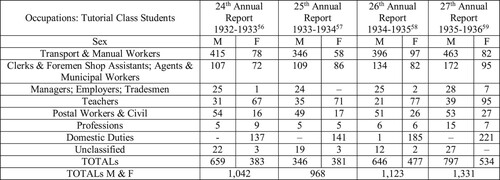

Figure 6. University of tutorial classes: male & female tutorial class student numbers by occupation (1932–1936). Source: University of Leeds Archive, LUA/DEP/076/1/46. University of Leeds Extension Lectures and Tutorial Classes (1932–1936).

Note:56 LUA/DEP/076/1/46 University of Leeds Extension Lectures and Tutorial Classes, 24th Annual Report (AR) (1932–33), 3-4.57 LUA/DEP/076/1/46, 25th AR (1933-34), 3-4.58 LUA/DEP/076/1/46, 26th AR (1934–35), 3, 5.59 LUA/DEP/076/1/46, 27th AR (1935–36), 3-4.

First, an explanation of the districts will clarify what regions the figures refer to. WEA Yorkshire District until 1929 covered a region that included Cleethorpes in the North and Chesterfield in the South but excluded Middlesbrough and Teeside. After 1929, to allow better administration of classes and courses, the Yorkshire District was re-organised into two districts—Yorkshire District North and Yorkshire District South. Yorkshire District South, the smaller of the two districts covered Sheffield and parts of Derbyshire and Lincolnshire. Middlesbrough and Cleveland formerly administered by the North-Eastern WEA District became part of Yorkshire District North. Both districts collected student statistics, but Yorkshire District North collected statistics that provide clearer information about female students than Yorkshire District South. The tables and bar charts here reflect only information about students in Yorkshire District prior to 1929 and Yorkshire District North after 1929. An additional and more detailed study than is possible here is required to decipher the statistics for men and women students in the Yorkshire District South Annual Reports. shows the numbers of all male and female students taking part in some form of WEA class from 1928 to 1939 in Yorkshire District and Yorkshire District North. The dip in student numbers in 1930 may represent the reorganisation of Yorkshire District into a North and South District in 1929.

presents comparative data on the total numbers of students, male and female, attending all WEA classes—university tutorial, extension courses, one year and terminal classes from 1928 to 1939. University tutorial classes took place over a period of three years and provided in-depth education on a particular topic. The other courses and classes provided by the WEA were shorter, taking place over one year or a term.Footnote46 Though statistical information about male and female students attending tutorial and other WEA classes is available prior to 1928 it is only in 1928 that formal reference is first made to female students where the Annual Report states ‘For the first time we are able to present figures showing the number of Women [sic.] in our classes compared with Men [sic.]’.Footnote47 1928 was of course also the year in which the Representation of People (Equal Franchise) Act became law, giving all men and women over the age of twenty-one the right to vote. To avoid confusion about the number of male and female students attending WEA classes between 1928 and 1939 I have chosen, where possible, to present the absolute numbers of students as computed and recorded by the WEA itself in the reports.

shows that an average of 2616 male students attended WEA classes annually against 2153 female students between 1928 and 1939. These figures imply that many more women than previously thought were accessing and attending adult education during the inter-war period, at least in Yorkshire. Indeed the 1928 Annual Report notes that ‘It will come as a surprise … to find that we have almost as many Women [sic] as Men [sic] in our classes.’, and this in a year when the number of male students far outstripped the number of female students compared to later years. Only once, in 1931 and then only by ten students, did the total number of female students exceed the total number of male students between 1928 and 1939. Otherwise, the total number of male students in excess of female students ranged from between 1815 in 1928 and 304 in 1938 during this period.

The reason for parity between male and female student numbers was attributed to a ‘growth in the number of classes for Women [sic.] only with classes timetabled to occur in the afternoons to accommodate Housewives [sic.] who have heavy and family responsibilities’.Footnote48 What this shows evidence of is that WEA administrators were conscious of the needs and circumstances of female students and made practical arrangements to make it easier for female students to attend classes. It also shows evidence of the success of the strategy to run women’s only classes.

selects some of the statistics in to gives a snapshot of how the number of male and female university tutorial class students changed in the decade from 1928 to 1939 with a considerable increase in female students from 448 in 1928 to 734 in 1939 while the number of male tutorial students remained relatively static. This data is evidence of how regional statistics may give a more accurate and nuanced impression of the male-female divide in students attending WEA classes than the National Annual Reports.

But, to get a more detailed understanding of the statistics collected in the regional reports we need to break the figures down further. More information about students in relation to their occupation, gender and, the subjects they studied is provided in and . gives details of the number of male and female students by subject group from 1931 to 1939 in Yorkshire District North.Footnote49 The information relates to university tutorial classes, extension courses, one-year classes and terminal courses. The subjects can be summarised as: Group 1—Economics and Politics; Group 2—Literature and the Arts; Group 3—Biology and Home Nursing.

A general analysis of the figures in in relation to class subjects shows that between 1931 and 1939 men outnumbered women by a significant margin in Group 1 subjects. However, the figures for Group 2 and 3 tell a different story and show how women, albeit in smaller numbers overall, outnumbered men in these subject areas.

provides information about the occupations of all WEA male and female students in Yorkshire District North from 1931 to 1939. The data in is based on the same statistics as except presented with respect to occupations as opposed to subject groups. The most interesting statistics in are those on students engaged in domestic duties. Women made up the vast majority of students engaged in domestic duties and reflected similar numbers to men engaged in manual occupations. For example, in 1931 male students in manual occupations numbered 1298 while women students in domestic occupations numbered 1028, a pattern that reoccurs in the other years represented. It is clear then from the figures that male students in manual occupations outnumbered their female counterparts. However, even more dramatically, female students engaged in domestic duties outnumbered their male equivalents. Given the entrenched attitudes to gender roles, the lack of employment opportunities and structural inequalities that discriminated against women these figures are not surprising. What is surprising is that from 1931 to 1939 in absolute figures, women engaged in domestic duties were the second largest group of students by occupation (numbering 10,409) after male manual workers (numbering 14,319).

The significance of these figures is that they show clear evidence that women were, to a significant extent, actively engaged in adult education during the interwar period and were, if not challenging the boundaries of domesticity, certainly exploring them. Not only this, but women were attending WEA classes in greater numbers than previously thought during this period. Further investigation on a national scale using more regional records would enhance our understanding of this hidden phenomenon that shows women as active citizens interested in broadening their horizons through adult education.

present statistical information about the number of adult male and female students by occupation attending tutorial classes only (not extension lectures) organised and administered by the University of Leeds from 1932 to 1946. Tutorial classes were administered jointly by the University of Leeds and the WEA whereas extension lectures were administered solely by the University of Leeds. Therefore, there may be some duplication between the WEA statistics for Yorkshire District North and the figures recorded in the University of Leeds reports. It has not been possible to clearly identify duplication in the statistics of the two organisations and for that reason I have chosen to analyse the reports separately. The records from 1936–37 to 1940–41 are missing but even so it is interesting to consider the data.

As reflected in the WEA Annual Reports for Yorkshire and Yorkshire North District, the University of Leeds extra mural records also show that female tutorial class students dominated the domestic duties, nursing and teaching occupations in all years. The number of women in domestic occupations remains relatively constant throughout this period but there is a large increase in the number of female students who are listed as teachers by occupation from 67 in 1932–33 () to 214 in 1943–44 (). This may reflect the demand for female teachers in the absence of male teachers during the Second World War.

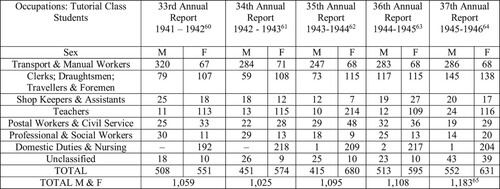

Figure 7. University of Leeds tutorial classes male & female tutorial class student numbers by occupation (1941–1946). Source: University of Leeds Archive, LUA/DEP/076/1/46 University of Leeds Extension Lectures and Tutorial Classes (1941–1946).

Note:60 LUA/DEP/076/1/46, 33rd AR (1941–42), 3.61 LUA/DEP/076/1/46, 34th AR (1942–43), 3-4.62 LUA/DEP/076/1/46, 35th AR (1943–44), 3.63 LUA/DEP/076/1/46, 36th AR (1944–45), 3.64 LUA/DEP/076/1/46, 37th AR (1945–46), 3.65 The 1945–46 Reports states that a total of 1179 students attended classes but repeated adding up of the student figures comes to 1183 as recorded in this table.

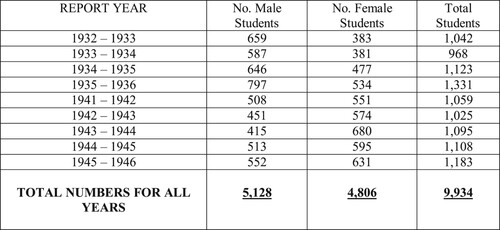

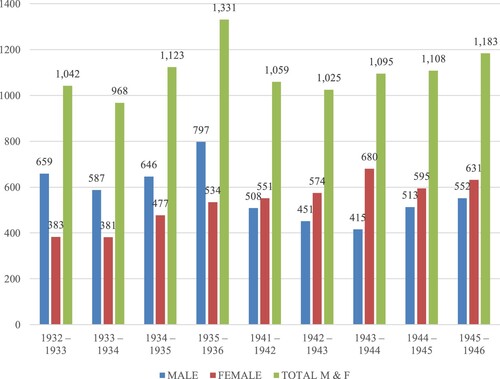

However, the most striking thing about the information detailed in and is the increase in the total number of female tutorial class students attending classes between 1932–33 and 1945–46. and below, using the data from and , give and depict the total numbers of male and female tutorial class students attending classes during these years.

Figure 8. Total number of male & female tutorial class students 1932–1946. Source: As for and .Footnote53

Figure 9. Universtiy of Leeds tutorial classes number male & female students 1932–1946. Source: As for and .

In 1932–33 the total number of students, male and female, attending tutorial classes was 1042. The number of female students was 383 (37%), while male students numbered 659 (63%). Male students thus outnumbered female students in that year by 276 (26%). However, as the War years progressed the total number of female tutorial class students increased steadily. From 1941–42 female student began to outnumber male students. In 1943–44 the total number of students attending tutorial classes was 1095. 680 (62%) female tutorial class students were recorded against 415 (38%) male students, outnumbering male students by 265 (24%)—a close reversal of the 1932–33 figure.

The total number of tutorial class students remained relatively constant from 1932–33 to 1945–46 with an average of 1034 per year. What then does the increase in the number of female tutorial class students signify? I will put forward one suggestion. It may imply that there were more places available for women students to take up because adult male students who would otherwise have taken up study were conscripted into the military as part of the War effort. Given the problem of the missing records my analysis of the statistics is speculative but if these records are taken account of in connection with the WEA Annual District Reports examined above it is reasonable to argue that a change was occurring in the adult education sector, whereby more women were attending classes.

The statistics raise several questions about the recruitment of female students to adult education. In peacetime was there a bias (implicit and/ or explicit) in favour of male students? When men were not competing for study places did women have greater access to adult education as disseminated by the WEA and universities? Did the war and war effort push women beyond domestic boundaries to explore their potential in a time of crisis through adult education? It is not possible to answer these questions here given that the statistics analysed represent only a microscopic proportion of students in adult education. However, what these statistics show is that it is possible to get a clearer idea about the numbers, the occupations of female students and the class subjects that women chose to study, provided the search for women students is broadened. A larger study of similar records and reports across several universities and WEA districts might expand our understanding of the factors at play in first when, and then why and where women took up adult education.

Conclusion

This article has explored and analysed the place of adult education as disseminated by the WEA and the University of Leeds in relation to women during the interwar period. It has provided evidence of the motivations and activities that the WEA undertook to welcome and include women into the world of adult education by promoting non-gender-based education in order to nurture and promote parliamentary democracy and active citizenship. The WEA recognised that women as equal citizens possessed significant political power that would, in part, determine the results of future elections. The education of women was significant then, not only to individual women but also to a society undergoing rapid change whereby women had important roles to play, and work to do that lay well beyond the boundaries of domesticity. During the interwar period there may not have been a strong feminist focus on removing gender based structural barriers that limited the employment and life prospects of women, but ironically, considerable attention was placed on how to prepare women for work and their public duties as citizens. The WEA reflected that aim irrespective of gender.

What is perhaps most revealing about this study is that a considerable minority—and perhaps even a tiny majority—of women were taking part in adult education during this period, as the statistics analysed from regional records show. To understand the greater significance of this phenomenon and to gain a more accurate understanding of women in the world of adult education, a national study using the regional records of the WEA districts and the extra mural records of universities is required. For now, though, this article has made headway in showing evidence of the extent to which women students took up adult education, their occupations and the subjects they studied in Yorkshire during the inter-war period.

Acknowledgements

This article is based on research undertaken for my PhD thesis funded by a 110th University of Leeds Anniversary scholarship and subsequent post-doctoral research sponsored by the University of Leeds Arts and Humanities Institute and funded by a University of Leeds Brotherton Short-Term Post-Doctoral Fellowship in April 2019. All errors in calculations are my own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pushpa Kumbhat

Pushpa Kumbhat is a lecturer in Foundation Year Studies at Newman University, Birmingham. She was awarded her PhD, ‘Working Class Adult Education in Yorkshire 1918–1939’, by the University of Leeds in 2018. She has published articles about adult education and the labour movement in the Socialist History (2021), Urban History (2020), the History of Education Journal (2020), and the Journal of Co-operative Studies (2016).

Notes

1 JHB Masterman, ‘Democracy and Adult Education’, in Cambridge Essays on Adult Education, ed. R. St. John Parry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1920, republished by Forgotten Books in 2012), 104. *Only women over thirty were eligible to vote in 1920. Either Masterman made an error, or his essay has been published incorrectly.

2 The 1919 Report. The final and interim reports of the Adult Education Committee of Reconstruction 1918–1919, reprinted with introductory essays by Harold Wiltshire, John Taylor and Bernard Jennings (Nottingham: University of Nottingham, 1980).

3 See Zoë Munby, ‘Women’s Involvement in the WEA and Women’s Education’, in A Ministry of Enthusiasm. Centenary Essays on the Workers’ Educational Association, ed. Stephen J Roberts (London: Pluto Press, 2003), 215–37; Roseanne Benn, ‘Women and Adult Education’, in A History of Modern British Adult Education, ed. Roger Fieldhouse et al. (Leicester, National Institute of Adult Continuing Education, 1996), 376–90; Gillian Scott, ‘As a War-Horse to the Beat of Drums’: Representations of Working-Class Femininity in the Women’s Co-operative Guild, 1880s to the Second World War’, in Radical Femininity. Women’s Self-Representation in the Public Sphere, ed. Eileen Janes Yeo (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1998), 196–219.

4 Caitriona Beaumont, ‘Citizens not Feminists: the Boundary Negotiated Between Citizenship and Feminism by Mainstream Women’s Organisations in England, 1928–39’, Women’s History Review 9, no. 2 (2000): 411–29.

5 Beaumont, ‘Citizens Not Feminists’, 412.

6 Anne Logan, ‘In Search of Equal Citizenship: The Campaign for Women Magistrates in England and Wales, 1910 – 1939’, Women’s History Review 16, no. 4 (September, 2007): 515.

7 Eve Worth, ‘Education and Social Mobility in Britain during the Long 1970s’, Cultural and Social History 16, no. 1 (2019): 67–83.

8 Ibid., 75–6.

9 Ibid., 77.

10 Ibid., 71.

11 Ibid.

12 Quoted by Valerie Yow, ‘In the Classroom Not at the Sink: Women in the National Council of Labour Colleges’, History of Education 22, no.2 (2006): 187.

13 For works on Albert Mansbridge and the WEA please see Bernard Jennings, Albert Mansbridge. The Life and Work of the Founder of the WEA (Leeds: University of Leeds, 2002); Jennings, ‘Knowledge is Power. A Short History of the Workers’ Educational Association 1903 – 1978’, Newland Papers, no. 1 (Department of Adult Education: University of Hull, 1979). The WEA initially called the Association to Promote Higher Learning in Working Men was renamed the ‘WEA’ in 1905 in acknowledgment that it served female as well as male students

14 A.J. Allaway, ‘Foreword’, in University Extension Reconsidered, Vaughan Papers in Adult Education, ed. B.W Pashley (University of Leicester, 1968), 4–5.

15 ‘Branch Histories – ‘X York’, The Supplement of the Yorkshire (North) Record, no. 41 in The Highway, Vol. XXVI, (February, 1934): np.

16 Tom Hulme, ‘Putting the City Back into Citizenship: Civics Education and Local Government in Britain, 1918–45’, Twentieth Century British History 26, no. 1 (2015): 26–51.

17 Workers’ Educational Association, Workers’ Education in Great Britain: a Record of Education Service to Democracy Since 1918 (London: WEA, 1943), 31.

18 Hulme, 45–6.

19 R.H.Tawney, The Adult Student as Citizen. A Record of Service by WEA Students Past and Present (Wea: London, 1938), 3–4.

20 Details of some of their biographies can be found in Christine Pushpa Kumbhat, ‘Working Class Adult Education in Yorkshire, 1918–1939’ (Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Leeds, 2018), 115–43.

21 Kumbhat, 125–7, 135.

22 In Kumbhat, 125.

23 Ibid., 135.

24 The Adult Student as Citizen, 2.

25 Munby, 231.

26 Ibid., Quoted, 231.

27 Ibid., 232.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 WEA, Educational Facilities for Women. Report of a Woman’s Educational Committee Operating in the London District (London: WEA, 1926), np.

32 WEA, Educational Facilities for Women, np.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.

35 Ibid.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Munby, 226–7.

40 Margaret Macmillan quoted by Munby, 227.

41 Munby, 227.

42 Ibid., 216.

43 Ibid.

44 West Yorkshire Archive Services (WYAS), WYL669/2/1 Yorkshire District WEA Annual Reports and Statement of Accounts, No. 1-10 (1915–1924); WYL669/2/2 Yorkshire District WEA Annual Reports and Statement of Accounts, No.11–20 (1925–1934); WYL669/3/1 Yorkshire District North WEA Annual Reports and Statement of Accounts, No. 25-26 (1939–1940); TUC Archive, London Metropolitan University, /4/2/1/2, WEA Districts Reports 1912–1954, WEA Yorkshire District North Annual Reports (1930–1939).

45 University of Leeds Archive, LUA/DEP/076/1/46 University of Leeds Extension Lectures and Tutorial Classes Reports 1932–1946. (Reports from 1936–1937 to 1940–1941 inclusive were unavailable.)

46 For more information on classes and courses offered the WEA see The 1919 Report. 62-68. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=0RBOAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed February 5, 2021).

47 WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD 14th AR (1928), 3.

48 Ibid.

49 Figures for 1930 have not been included in because the subject groups for Group 1 and 2 were reversed in 1930 with Group 1 representing ‘Literature & the Arts’ and Group 2 representing ‘Economics & Politics’ From 1931 to 1939 the subject groups for Group 1 represented ‘Economics & Politics’ and the subject groups for Group 2 represented ‘Literature & the Arts’. To maintain uniformity between the statistics for each year the author judged that it was better to compare like with like, by excluding statistics for 1931, to avoid ambiguity and confusion in understanding the statistics.

50 Paul Bolton, Education: Historical Statistics, House of Commons Library, November, 2012: p.20. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN04252/SN04252.pdf (accessed November 30, 2021).

51 The references for each year depicted in are as follows: 1928 – WYAS, WYL669 1/2 WEA Yorkshire District (YD)15th Annual Report(AR) (1929), ‘Women and Men Students 1927/28’, 3. 1929 – WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD 15th AR (1929), ‘Women and Men Students 1928/29, 3. 1930 – WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD North 17th AR (1931) ‘Summary, 1929–30’, 5. 1931 – WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD North 17th AR (1931) ‘Summary, 1930–31’, 5. 1932 – WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD North 18th AR (1932) ‘Occupational Analysis, Totals all Classes’, 6. 1933 – WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD North 19th AR (1933) ‘Occupational Analysis’, 5. (The WEA did not record the total figures for male and female students in this report, so the author calculated the total number of male and female students by adding the totals of each subject group.) 1934 – WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD North 20th AR (1934) ‘Summary of Group Totals’, 4. 1935 – TUC, /4/2/1/2, WEA Districts Reports 1912–1954, WEA YD North 21st AR (1935) ‘Occupational Analysis’, 6. 1936 – TUC, YD North 22nd AR (1936) ‘Occupational Analysis’, 7. 1937 – TUC, YD North 23rd AR (1937), ‘Occupational Analysis’ & ‘Summary for Totals by Subject Group’, 13, 16. I found a discrepancy between the figure given for the total number of male students under ‘Occupational Analysis’ and the ‘Summary of Totals by Subject Group’. Under ‘Occupational Analysis’ the total number of male students was given as 2,642 but under ‘Summary’ the total number of male students was 2,462. The author checked the male total number by adding the totals of each subject group. 2,462 is the correct total of male students for 1937. 1938 – TUC, YD North 24th AR (1938) ‘Occupational Analysis’, 7. 1939 – WYAS, WYL669 1/2, YD North 25th AR (1939) ‘Summary of Totals by Group Subject’, 8.

52 The references for each year depicted in are as follows: 1931 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, WEA YD North 17th AR (1931), 4. I found three calculations to be incorrect in the statistics for student numbers by occupation and subject group on page 4. 364 was the number of female tutorial and extension class students for Group 1 subjects recorded. The correct figure is 384. 125 was the total number of female students taking one-year and terminal courses recorded. The correct figure is 258. I have adjusted the figures presented for 1931 in to reflect these corrections. A discrepancy exists between the total numbers of male and female students recorded on page 4 and the statistical summary on page 5 of the report. This is explained as occurring because ‘Particulars of occupations have not been supplied in a few instances. This explains the discrepancy between the gross totals … and the statistical summary’, 5. In order to get a sense of the number of male and female students attending WEA classes by group subject the figures from the table depicting students by group subject and occupation have been presented . 1932 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, WEA YD North 18th AR (1932), 6. 1933 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, WEA YD North 19th AR (1933), 5. 1934 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, WEA YD North 20th AR (1933), 4. 1935 – TUC, /4/2/1/2, WEA YD North 21st AR (1935), 6. 1936 – TUC, YD North 22nd AR (1936), 7. 1937 – TUC, YD North 23rd AR (1937), 16. 1938 – TUC, YD North 24th AR (1938), 7. 1939 – WYAS, WYL 669 1/3, YD North 25th AR (1939), 8.

53 Excludes Summer School Student Numbers.