ABSTRACT

This article seeks to untangle the relationship between religion, humour, and feminism by analysing the humour which underscored the campaign for women’s ordination in the Church of England. By examining the wordplay, the cartoons, and the physical objects through which humour was expressed, this article highlights the creativity which underscored the activism of these lesser-known activists. Through centring the experiences of these religious activists, this article extends existing scholarly conversations which seek to diversify understandings of who and what should be considered part of the ‘women’s movement’.

Introduction

In 1988, at a conference held in Durham, Monica Furlong identified the cathartic role humour served within the campaign for women’s ordination in the Church of England. During her lecture titled ‘Exploring for Divine Newness’, the journalist, novelist, and self-proclaimed feminist explained: ‘I enjoy employing humour at the expense of complacent church leaders, which I find to be a relatively harmless way of harnessing my considerable aggression’.Footnote1 Reflecting on her work as a Spiritual Director, in which she supported women working within the church in their attempts to deepen their relationship with the divine, Furlong stressed how common feelings of anger were amongst the women she worked with. She described anger as a ‘strong and important emotion, so profoundly valuable’, but cautioned her audience about the destructive impact anger could have on one’s life ‘when it turns inwards’ draining ‘lives of joy or meaning’.Footnote2

Furlong encouraged Christian women to channel these feelings into creative outputs, finding expression for her own ‘aggression’ in the creation of her 1990s newsletter: Uppity. The ironic title reclaimed an insult levied against her and other activists involved in the campaign for women’s ordination who were accused of being too loud, too confrontative, too strident. Within the newsletter, Furlong used humour to both inform and galvanise action. In October 1992, Furlong encouraged readers to ‘go sick, resign your job, cancel your holiday, neglect the kids, sell the antiques to pay your fare’ in order to form part of a vigil outside Church House, London on 11 November 1992.Footnote3 Inside, the church’s representative body, the General Synod, was set to vote on the Priests (Ordination of Women) Measure.Footnote4 As Anglican women gathered on the steps of Church House, those inside eventually passed the Measure by a margin of two votes—thereby dismantling the male-only priesthood by enabling Christian women to become priests, although significantly not bishops, in the Church of England.Footnote5 In the immediate aftermath of the vote, activists who had dedicated decades of their lives to this campaign for legislative reform sang, danced, and laughed in joyful thanksgiving.

This article seeks to untangle the relationship between religion, humour, and feminism by analysing the humour which underscored the campaign for women’s ordination. The timeframe of this article spans the ‘long 1980s’, defined here as 1978–1994—mirroring the founding and closure of the main organisation championing legislative reform in the post-war era: the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW). It questions the role humour played in conveying activist messaging and explores the ways in which humour operated publicly, as a tool of communication, and privately, as a personal expression of frustration, defiance, or despair. By examining the wordplay, the cartoons, and the physical objects through which humour was expressed, this article highlights the creativity which underscored the activities of these under-studied activists. It begins by introducing some of the activists within the campaign, to provide an insight into the demographic of women who populated the movement. Through centring the experiences of these older, religious activists, this article echoes Caitríona Beaumont by urging that the term ‘women’s movement’ should ‘refer to all groups which promoted the social, political and economic rights of women, regardless of whether or not they identified themselves as feminist’.Footnote6 Moreover, by exploring a campaign which extended into the 1990s, this article challenges the accepted periodisation of women’s action and activity in the post-war period. It also extends emerging conversations about the grassroots British Christian feminist movement.Footnote7 From here, the article is split into three sections: material objects and humour, humour and performance, and printed humour. Throughout each section it is demonstrated that there is power in unruly women laughing.

Commencing in the early twentieth century, the campaign for women to enter the professional ranks of the male-only priesthood was initially championed by prominent Anglican suffragists Maude Royden, Ursula Roberts, and Edith Picton-Turbervill.Footnote8 As the sex-bar was, at least formally, lifted from professions such as law, medicine, and higher education, female ordination appeared a natural progression after political emancipation. Collectively these social reformers lobbied the Church of England’s representative bodies throughout the 1920s and 1930s, urging that legislation must be passed to enable women to be ordained priests.Footnote9 These activists drew inspiration from the lives of their foremothers: saints like Hilda of Whitby (the founder and first abbess of Whitby’s monastery); anchoresses of the Middle Ages like Julian of Norwich (remembered in part for her extended comparisons of God to a mother); and nineteenth century activists like Catherine Booth (co-founder of the Salvation Army) and Mary Sumner (founder of the Mothers’ Union).Footnote10 However, the hopes of these Anglican suffragists were tempered by an awareness of the magnitude of their task. Writing in 1916, Royden declared that:

The mere question, ‘Why should not women be admitted to holy orders?’ causes some Churchmen to cry out and cut themselves with knives, while others, more reasonable, assure us that there are indeed reasons, but of a character so ‘fundamental’ as to prohibit their being put into words.Footnote11

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s opponents of women’s ordination remained ‘vehemently and implacably’ opposed to women entering the sanctuary, the sacred space surrounding the altar.Footnote12 Their opposition provides an insight into the spectrum of fears and taboos surrounding women’s bodies, and their capacity to defile sacred spaces, which governed the mentalities of some clergymen.Footnote13 Encompassed within these taboos was an implicit belief in the separation between the spiritual and the physical. Within this dualistic understanding, men were associated with rationality, intellect, and spirituality, women with corporality, sexuality, and desire.Footnote14 The power and potency of these beliefs proved difficult to overcome, and with little success the campaign for women’s ordination entered a period of latency which endured until the 1970s.Footnote15

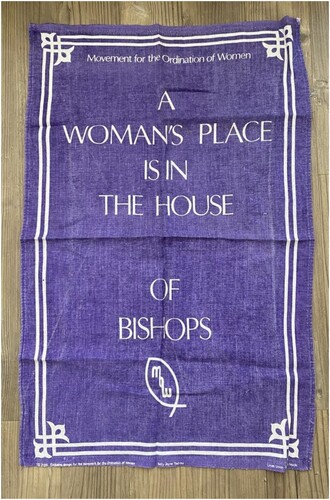

During the 1970s members of the global Anglican Communion, notably Canada (1975), New Zealand (1976), and North America (1976), began rapidly ordaining women after the Anglican Consultative Council (the most senior advisory body in the Anglican Communion) passed Resolution 28 which advised bishops that there were ‘no valid theological objections’ to the ordination of women and asked every national church to study the question.Footnote16 Following this trend, in 1978 the General Synod of the Church of England voted on whether to remove the legal barriers prohibiting women’s ordination. The vote took place against the backdrop of decades of Christian women’s activism, first led by women like Maude Royden, and subsequently taken up by an organisation called the Anglican Group for the Ordination of Women (AGOW) which was founded in 1929 and became the main Anglican organisation championing women’s ministry during the mid-twentieth century. Notably the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) took little interest in this campaign during the 1970s.Footnote17 Despite the efforts of Christian campaigners, the vote failed to achieve an overall majority and the Church of England continued to declare itself not ready for women priests.Footnote18 For many Christian women in England the result elicited feelings of anger, frustration, and disappointment. Sally Barnes, a headteacher, clergy wife, and committed advocate for women’s ordination, watched the vote whilst at home sick with pleurisy. As she sat on the floor by the fire to keep warm, she described weeping with anger as the result was announced.Footnote19 The vote also galvanised action, and the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW) was formed later that year. Founded in 1978, MOW was the most significant, and indeed successful, campaigning organisation predominately led, populated, and championed by Christian women in the post-war era. At its peak in 1992 MOW attracted 10,000 supporters, making it an influential minority movement within the Anglican church. MOW was a single-issue pressure group which campaigned at both a national and regional level for women to be ordained priests in the Church of England. At a national level members of MOW’s Central Council organised conferences, pilgrimages, and celebratory services in cathedrals across the country. They produced booklets, pamphlets, and leaflets which outlined the theological arguments in favour of women’s ordination. They published newsletters and, from 1986 to 1994, a magazine called Chrysalis: Women and Religion. Members of MOW’s regional branches stood as candidates for the General Synod. They lobbied existing Synod members to vote in favour of the ordination of women and wrote letters to their Members of Parliament asking them to state publicly their support for women priests. They staged demonstrations, protests, and vigils with ordination services of male clergy members serving as a frequent target for activism. One particularly memorable demonstration took place during an ordination service of male clergy held at St Paul’s Cathedral on 29 June 1980. During the service, eight demonstrators took part in a silent protest in which they displayed banners declaring ‘ORDAIN WOMEN’ to hundreds of worshippers at the cathedral. The demonstrators were quickly removed from the building, and the Bishop of London, Dr Gerald Ellison, subsequently described the demonstration as ‘stupid and discourteous’ to members of the press.Footnote20 During these gatherings MOW members wore badges and t-shirts which featured playful slogans such as ‘A Woman’s Place is in the House of Bishops’ and ‘God is an Equal Opportunities Employer—Pity About the Church’.Footnote21

These tongue-in-cheek slogans were indicative of the humour which underscored much of this campaign. The solemnity associated with religious rituals and rites of passage can obscure the interactions and interconnections between humour and religion. Humour is a capacious category which encompasses satire, wit, banter, jokes, irony, folly, mockery, jest, puns, and play. What is considered humorous is subjective, historically contingent, and culturally contextual. The transient nature of humour (that humour is often spoken and quickly forgotten, without being written down or recorded) raises an array of methodological issues.Footnote22 How can historians build an archive of historical humour? Is it possible to capture something so ephemeral? How might tone, intonation, and body language impact delivery and reception? A converse set of problems exists for instances of printed humour. The sheer volume of work created by cartoonists, for example, raises methodological questions for historians about source material selection and censorship.Footnote23 When considering the methodological challenges of studying humour, a distinction must also be made between humour and laughter—particularly when analysing women’s activism. Laughter is bodily, and as such it is vital to acknowledge the misogynistic, violent, and racist contexts in which women’s bodies exist. The decision to laugh, or to abstain from laughing, can therefore be understood variously as a political act, a mechanism of self-care, an expression of superiority, an indication of nervousness, a method of de-escalation, a form of release, and sometimes as a weapon to puncture patriarchal values.Footnote24

Throughout this campaign, humour served as an antidote to the theological wranglings surrounding male leadership and authority. In seeking to find a biblical precedent for their activism, those on both sides of the ordination debate found contrary evidence in the church’s sacred texts. Supporters of women priests found biblical authority for their campaign in Galatians 3:28, in which St Paul wrote: ‘There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus’. Supporters argued this passage demonstrated the divinely inspired equality of men and women, and thus suggested that women should be able to enter the priesthood on the same terms as men. They emphasised the biblical precedent for women’s leadership, highlighting the respect Christ demonstrated to women which transgressed the traditional gender conventions of Palestinian society (Acts 1:15–26; John 4:27; Luke 8:2–3).Footnote25 Moreover, they celebrated biblical women like Phoebe, Priscilla, and Lydia who took part in evangelism and teaching and were leaders of house churches.Footnote26 Those opposed found contrary evidence in St Paul’s injunctions to the Corinthian Church: ‘women should remain silent in the churches. They are not allowed to speak, but must be in submission, as the Law says’ (1 Cor. 14:34). Opponents argued for the headship of man over woman, emphasising the spiritual equality of men and women whilst maintaining that they had different gifts and roles in relation to home, family, and marital life, and indeed religious leadership. They highlighted that Christ was incarnated as a man and chose only male disciples, as such to be an Icon of Christ a priest must embody Christ’s male form. Moreover, some opponents emphasised that the Church of England simply did not have the authority to make such a momentous decision which would ultimately preclude a reunion with the Roman Catholic church (despite the existing analogous differences between the two churches, such as married priests and Latin services).Footnote27 These divergent interpretations of texts which were deemed to be infallible were at the heart of this debate which spanned across the twentieth century.

Activists in the Movement for the Ordination of Women (MOW)

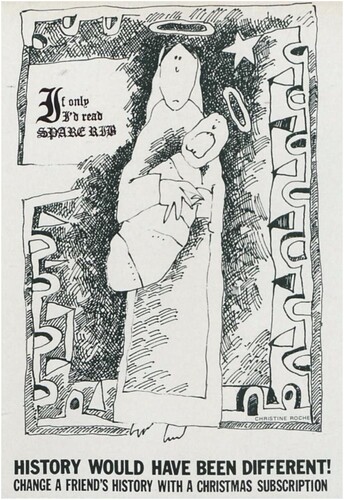

In February 1977 Catherine Ebenezer, a self-identified Christian feminist, wrote to Spare Rib, the iconic second-wave feminist magazine (1972–1993), to express her disgust at the magazine’s use of ‘religious imagery for advertising purposes’. In a letter entitled ‘Blasphemous Imagery’, Ebenezer criticised the iconic second-wave feminist magazine for using a cartoon drawing of the Virgin Mary to entice new subscribers. The drawing, which depicted a rueful looking Mary holding a screaming infant, was accompanied by the words ‘if only I’d read Spare Rib’. The advertisement declared that, had Mary had her consciousness raised, ‘History would have been different!’ (). Reflecting on the image, Ebenezer wrote: ‘Christian feminists are fairly thin on the ground, but they do exist; some like this writer even subscribe to Spare Rib! Cannot our feelings be taken into some consideration?’.Footnote28 Ebeenezer’s impassioned plea to the editors of Spare Rib highlighted the inherent subjectivity of humour and raised questions about the magazine’s imagined audience.

Figure 1. ‘If Only I’d Read Spare Rib’. Spare Rib, Issue 53, p.47. Reproduced with permission from Christine Roche.

Ebeenezer’s letter also illuminated the sense of marginalisation felt by many Christian women involved in the post-1968 women’s movement. Women who identified as both religious and as a feminist occupied a liminal space within the women’s movement of the late-twentieth century. In their book exploring the debate surrounding women’s ordination to the priesthood in the Church of England, clergy wives Susan Dowell and Jane Williams explained that during the 1970s religious women frequently ‘operated as closet feminists in the Church and closet Christians in the women’s movement’. Whilst ‘the Church was busy dismissing feminists as incompatible with—or irrelevant to—good Christian womanhood’, the authors suggested that the women’s movement ‘was seriously doubting whether Christians could be feminists at all!’.Footnote29 This sense of liminality and isolation was further compounded by the activists’ age. Pat Thane has noted that the contemporaneous WLM was ‘overwhelmingly a movement of younger women’.Footnote30 The demands set out by the WLM, particularly those related to access to childcare and bodily and sexual autonomy, predominately reflected the concerns of younger women and new mothers. Moreover, the anti-establishment and anti-hierarchical structure of the WLM, which prided itself on a refusal of stars, meant that the movement ‘tended to be hostile or indifferent to constitutional action through parliament’.Footnote31 Whilst Claire Langhammer, Hester Barron, and Selina Todd have used youthful experiences to demonstrate that the life cycle has determined historical meanings of work, gender, and family life, historians have been somewhat reluctant to apply these insights to later life.Footnote32 Indeed, Charlotte Greenhalgh has noted that age is rarely given the ‘analytical primacy’ that is afforded to ‘class, race, and gender’.Footnote33

In contrast to the WLM, the campaign for women’s ordination was ultimately a movement for legislative reform, predominately populated by middle and upper-class white women over the age of 40. Whilst these activists were relatively unknown outside of Anglican circles, within the Church of England many of the women involved in the campaign became prominent and influential figures—particularly in light of the frequent letters and articles they penned for the religious press, or the speeches they made in General Synod.Footnote34 Notably, many of the prominent figures within the campaign for women’s ordination were born between 1915 and 1930, for example: Dame Christian Howard (1916–1999), Rev Una Kroll (1925–2017), and Monica Furlong (1930–2003). Explorations of the lives of those involved in the campaign reveal that MOW, like the movement for women’s suffrage, was forced to navigate intense disagreements between advocates of conservative constitutional reform and those who wished to engage in radical and confrontative action. Howard represented the former approach. Born in Castle Howard, North Yorkshire, to Ethel Christian Methuen and Geoffrey Howard, a Liberal politician who served in Asquith’s government, and granddaughter of the suffragist Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle, Christian Howard was shaped by her political heritage and frequently described herself as ‘a political animal’.Footnote35 As an outstanding public speaker, and an advocate of constitutional reform, she was involved in church governance and decision making at a regional, national, and international level.Footnote36 Her experience navigating the church’s governmental structures over many decades led her to be a key figure in devising MOW’s synodical strategy for achieving legislative reform.

If Howard represented a moderate and constitutional approach to activism, Una Kroll and Monica Furlong served as figureheads for radical action. Kroll, a doctor, an eventual priest, and a later convert to Catholicism, gained notoriety in the immediate aftermath of the General Synod’s refusal in 1978 to remove the legal barriers preventing women from being ordained as priests. Observing this refusal from the gallery of Church House, she declared to those below: ‘we asked you for bread and you gave us a stone’.Footnote37 In transgressing the silence and sobriety associated with both the ceremony of General Synod, and women’s perceived subordinate roles in the church, Kroll’s cry was met with a ‘roar of disapproval’ and in the days which followed Kroll was ‘subjected to relentless ridicule from the press and derision and anger from the clergy’.Footnote38 Yet, Kroll’s declaration served as a clarion call to many Christian women.Footnote39 The subsequent flurry of activism, best typified by the formation of MOW, led scholars such as Jenny Daggers to designate 1978 as ‘a watershed in Christian women’s consciousness and activity’.Footnote40 Emerging slightly later than the WLM, the post-1968 British Christian feminist movement was forged within the context of extensive secular activism for women’s rights; epitomised in the founding of the National Abortion Campaign (1979).Footnote41

Monica Furlong, like other activists in MOW such as Diana and Rev John Collins who were important figures in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, was shaped by her involvement in secular activism.Footnote42 As a journalist and religious affairs correspondent, Furlong cut her activist teeth by becoming involved in the campaign for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the 1960s.Footnote43 Her activism was shaped by events in her personal life, particularly an affair which led to the end of her marriage in 1977. Drug taking, together with Freudian psychoanalysis in her early 50s, became a vital part of her psychological and spiritual growth.Footnote44 Her feelings of sorrow surrounding her troubled marriage propelled her to speak out on behalf of others whose alleged failings were frowned on by the church, she wrote pamphlets on divorce for the Mother’s Union and on homosexuality for the Society of Friends.Footnote45 Furlong’s life exemplified the feminist maxim the ‘personal is political’. When confronted with difficult or painful situations in both her personal and activist life, Furlong used humour as a way of giving vent to these feelings. As a prominent figure within the campaign, serving as MOW’s leader between 1982 and 1985 and subsequently the editor of MOW’s magazine Chrysalis between 1986 and 1988, Furlong’s confrontative and frequently irreverent approach to figures of authority infused the shape and style of action deployed by MOW throughout the 1980s.

Furlong’s irreverence is perhaps best epitomised in her comments following the eviction of the St Hilda Community in 1988 from St Benet’s Chapel, Queen Mary College, by the Bishop of London, Graham Leonard.Footnote46 The Community had been inviting women ordained in the Anglican Communion to celebrate weekly Sunday evening services. These celebrations, dubbed ‘illegal Eucharists’ as they were held at a time when women were not allowed to be ordained priests in the Church of England, caused much contestation and controversy. The Community initially ignored the Bishop’s command to desist with their celebrations, noting that St Benet’s was an ecumenical centre and it was therefore common for Methodist women to celebrate in that space. However, the London Diocesan Fund discovered they owned the land on which the chapel stood, and the Community were sent a stern letter from the lawyers of the diocese stating that the Community were committing trespass. This exchange led Monica Furlong to drily observe that: ‘Plainly the bishop was not into forgiving our trespasses’.Footnote47

Humour and laughter, often expressed through wordplay, have been important tools utilised by activists throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote48 Krista Cowman, in the context of the women’s suffrage movement, has explored the ways in which humour was deployed by women as a ‘deliberate tactic’ to ‘diffuse hostility’, and ‘give vent to critical feelings in a comparatively safe manner’.Footnote49 Drawing on this tradition, members of MOW similarly used humour as a method of challenging ecclesiastical mores and of subverting patriarchy. Reflecting on the humour which underscored the campaign for women’s ordination, Margaret Webster (one of MOW’s Executive Secretaries) explained: ‘one reason why I think that people have stuck with MOW over so many years of struggle and snail’s pace progress is that we have laughed such a lot’.Footnote50 Laughter served as an antidote to those opponents that had ridiculed and mocked women who spoke about their longings for ordained ministry (with some opponents declaring, for example, that one could no more ordain a woman than a pork pie).Footnote51 Humour was therefore used by activists as both a method of uniting women and as a retaliatory tool.

Material objects and humour

Gloria Kaufman has suggested that a commitment to social revolution underscored feminist humour, which frequently ridiculed social systems in need of reform. Feminist humour was, for Kaufman, a ‘humour of hope’.Footnote52 In a similar vein, humour provided a vehicle for supporters of women priests to envision a different church, in which women’s lives and ministries were validated and valued. Epitomising this sense of hope was a mass-produced object of activism: a tea towel embossed with the slogan ‘A Woman’s Place is in the House of Bishops’. The tea towels cost £2.50 and were available through MOW’s mail order list which was circulated to all members.Footnote53 The colour scheme of the tea towel was white and episcopal purple in a nod to the colour traditionally worn by male bishops, thereby implicitly conveying a desire for women to reach the highest echelons of the Church of England’s hierarchy. The use of purple and white additionally drew on the movement’s political heritage, evoking images of the women’s suffrage movement.Footnote54 Whether the colour scheme was a conscious or unconscious decision to call upon their suffrage heritage, the choice served to position the campaign for women’s ordination as part of a longer trajectory of women agitating for equality. Thereby reminding us that our definitions of the ‘women’s movement’, and women’s activism more widely, must be broadened and diversified ().

Figure 2. ‘A Woman’s Place is in the House of Bishops’. Reproduced with permission from Grace Heaton.

The choice of item was also significant as tea towels were often used during the performance of church duties traditionally ‘assigned’ to older women, such as catering events, serving post-service teas, or running creches.Footnote55 Meanwhile, the slogan ‘A Woman’s Place is in the House of Bishops’ was a reformulation and extension of the idiom ‘A Woman’s Place is in the Home’. The space left between the two separate sections of text on the tea towel encourages the reader to pause, leaving the final two words to operate as a punch line—and for some a call to arms. Phrases like ‘A Woman’s Place is in the House of Bishops’ exemplify what Kaufman has termed ‘pickup’ humour; a form of humour based on equity which is predicated on laughing with people, rather than at them.Footnote56 This example of ‘pickup’ humour challenged stereotypes which cast feminists as humourless ‘kill-joys’ and subverted the ideology of domesticity through imbuing objects traditionally associated with housework with new meaning.Footnote57 Beyond their strategic importance these tea towels also came to be imbued with significant symbolic importance for activists and many formed emotional attachments to them. Christian Howard’s obituary, for example, detailed that during the final weeks of her life in 1999 the wall next to her hospital bed was ‘enlivened by a purple tea-towel declaring “A Woman’s Place is in the House of Bishops”’.Footnote58 The tea towel commemorated the role she had played in an historic campaign and signified her hope for future generations of Christian women.

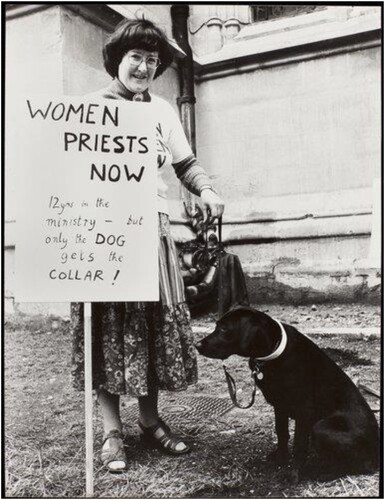

During the same 1978 meeting of the General Synod, in which Una Kroll shouted down from the gallery of Church House, another activist staged her own protest. Bernice Broggio held a homemade placard in one hand, and a dog lead in her other. Broggio’s demure outfit, comprised of a long skirt and a long-sleeved high-necked top, was partially covered by an ‘ORDAIN WOMEN NOW’ T-shirt, just visible in . During the late-twentieth century T-shirts were a common canvas for activist messaging as they tended to be inexpensive, easily mass-produced, and ideal for screen-printing slogans. They provided activists with a ‘form of political dress, and political address’.Footnote59 The mass-produced T-shirt identified Broggio as part of a wider activist community. In the days that followed the meeting of General Synod, a photograph of Kroll making her declaration whilst wearing the same ‘ORDAIN WOMEN NOW’ T-shirt appeared on the front page of the Church Times, a weekly Anglican newspaper, under the headline ‘Women Priests: Battle Hots Up’.Footnote60 Photographs of the T-shirt, and the message it sought to convey, were therefore seen by Anglicans across the country. Notably, the front page also reported the anti-abortion protests staged by the organisation ‘Life’ which took place during the same November 1978 meeting of General Synod. The pro-ordination statement T-Shirt therefore existed within, and contributed to, a wider discussion about women’s rights within the Anglican Church.

Figure 3. Bernice Broggio displays a placard which reads: ‘WOMEN PRIESTS NOW 12yrs in the ministry – but only the DOG gets the COLLAR!’. TWL/2004/238. Orphan Licence: OWLS000401-1.

The mass-produced T-Shirt contrasted effectively with Broggio’s homemade placard which demonstrated her wit and creativity. Echoing the same irreverent tone which would come to characterise much of MOW’s activism throughout the ‘long 1980s’, her placard read: ‘WOMEN PRIESTS NOW 12yrs in the ministry—but only the DOG gets the COLLAR!’. Thereby highlighting the significant and enduring, albeit lay rather than clerical, service women offered to the Church of England.Footnote61 Her demonstration also exhibited her scepticism at the authority of those in positions of ecclesiastical power by satirically challenging women’s subordinate roles within the church. In an act of humorous defiance, Broggio’s dog is photographed wearing a white clerical collar, colloquially termed a dog collar, which would have symbolised the holy orders of male clerics to contemporary observers. By placing this item of sacred religious dress on a dog, the authority and indeed superiority of clerical men was called into question. Broggio’s eye-catching use of props and puns quickly and effectively drew attention to her cause. Whilst it is difficult to trace who took and staged the photograph, and indeed whether it was published or kept as a personal record of the protest, this image provides an immersive insight into the wit, satire, and irony which infused these women’s methods of activism. For many activists throughout the ‘long 1980s’ these expressions of humour became a way of engaging with a topic which was experienced as deeply painful in a public and performative way.

Humour and performance

Alongside deciphering humour within objects of protest, humour is also evident in instances of collective action. On Saturday 26 June 1982, MOW hosted the second annual Festival of Women at St James’s Piccadilly, London. Located near the loci of power situated in Whitehall and Westminster, this Anglican church was designed by Sir Christopher Wren and consecrated in 1686.Footnote62 Under the steer of Rev Donald Reeves, Rector of St James’s between 1980 and 1998, a liberal church community grew which, like those active in left-wing politics, objected to the Falklands War (1982), supported the miners’ strike (1984–85), and opposed the unregulated market.Footnote63 Whilst the Labour Party weathered what Eliza Filby has termed ‘a period of self-inflicted paralysis’, the Church of England ‘stepped up as the “unofficial opposition” to defend what its clergy considered to be Britain's Christian social democratic values’.Footnote64 From the benches of the Lords to the picket line, Anglican clergymen denounced neoliberal theory and practices as transgressing Christian values of ‘fellowship interdependence, and peace’.Footnote65 Reeves’ vocal opposition to Conservative policies led Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to decry him as ‘a very dangerous man’.Footnote66 St James’s, with its internal galleries on three sides and a large forecourt, thus provided the ideal practical and ideological space to host the Festival of Women. Moreover, Reeves’ willingness to open St James’s to MOW serves as evidence of the important role that supportive male clergy members played in facilitating the campaign.Footnote67

The culmination of this all-day festival was an evening performance of ‘Another After Eve—A Tease in Two Parts’, written and produced by Monica Furlong.Footnote68 The satirical production was performed by a drama group called Eve’s Lot, which believed that ‘the best way to deal with a painful situation is to joke about it’.Footnote69 The group’s name formed part of a wider trend within the British Christian feminist movement which sought to rehabilitate Eve’s image, thereby celebrating, rather than demonising, women’s sexuality.Footnote70 At the core of their performance was a ‘concern about the disregard of women and their abilities in the Church of England’, notably evident in the Church of England’s refusal to ordain women as priests. For members of the drama group this refusal was ‘not just an isolated piece of religious conservativism’, but was indicative of a wider devaluing of the lives and contributions of women in the Anglican church.Footnote71 The press release teased that the ‘targets’ of the performance were ‘those archbishops, bishops, clergy and laity (even the Pope gets in on the act) whose attitude to women leaves, in their view, a lot to be desired’.Footnote72

The performance took place inside St James’s, beginning with a procession of the cast members. Imitating and inverting the rituals normally undertaken by male priests, the script instructed: ‘A verger with staff conducts Sue D. to [the] pulpit, bows to her, and she climbs into it’ whilst the ‘rest of the cast stand along the front of the nave’.Footnote73 Susan Dowell opened the performance by addressing the audience from the pulpit, a space which has traditionally embodied male clerical authority.Footnote74 From the outset, the cast thus subverted the divinely inspired gender hierarchy at the heart of oppositional arguments against women’s ordination. This reclamation of religious space set the tone for the rest of the performance, as did the opening remarks made by Dowell, co-author of one of the first books of feminist theology produced in Britain.Footnote75 She explained to her audience that the cast’s ‘main purpose is to make you laugh’ as there are ‘not many laughs in the Church of England today. Or at least not many people who intend to make you laugh’.Footnote76 The cast executed this aim through various means: monologues, songs, jokes, and physical comedy (during which the cast searched the chancel and found ‘an old shoe’, ‘an empty whisky bottle’, ‘a pair of false teeth’ and a ‘dead mouse’—prompting the narrator to quip: ‘It’s time the C. of E. had a thorough spring-clean’).Footnote77 Each of the actors played themselves, an artistic decision on behalf of the writer which hinted at how high profile some of the actors had become within Anglican circles as a result of their involvement in the campaign for women’s ordination.

One way in which the cast addressed the ‘disregard of women and their abilities in the Church of England’ was by satirically challenging the stereotypes surrounding women. During an exchange, two activists discussed the possibility of being ordained:

No, stoopid, you’re a girl. Girls can’t do those things

Why not?

Because they didn’t row at Oxford, and they don’t belong to the Athenaeum, and because Jesus doesn’t like them, because their voices are all funny, and because they’ve got bosoms, and because … well … you know …

What?

You know, like your Mum every month. It’s because women are … well rude.

Well, what can girls do then, if they can’t be archbishops, or bishops, or lovely clergymen...?

Girls can be the Queen, and Prime Minister, and sopranos, and writers on the Guardian and Angela Rippon and the Virgin Mary.Footnote78

Jibes about the ‘old boys’ network’ which dominated the Church of England, evident in the references to elite male-dominated educational institutions and male-only members’ clubs, were recurrent throughout the performance. These jibes were intermingled with discussions about the fears and taboos surrounding women’s bodies. The comments about women being ‘rude’ made light of questions commonly asked by clergy members and parishioners, sometimes innocently, sometimes maliciously, of women seeking ordination: would they celebrate the eucharist whilst menstruating? What would happen if a woman was pregnant when she was ordained? Would the ordination of a pregnant woman result in the twin ordination of mother and baby? Would the baby distract her from her priestly duties? Would her priestly duties impede her capacity to be a good mother? Alongside fears about the incompatibility of motherhood and the priesthood (which implied that all women would wish to be mothers), stereotypes of women as the seductress Eve were also addressed throughout the performance. The cast promised the performance would provide ‘entertainment, or tease, as we call it’. The pun both played on the idea of teasing or taunting opponents, whilst also alluding to the ways in which women were objectified and sexualised by the male gaze. In Act Two, for example, one female cast member begins a strip tease as a poem describing ‘A Perfect Woman’ draws to a close. The script instructs the cast member to remove ‘her anorak, gloves, woolly hat, jumpers’ to finally reveal her ‘ORDAIN WOMEN NOW’ T-shirt.Footnote79 The performance itself challenged the idea that sexuality and desire were preserves of the young, whilst the punchline served as what Anna Frey has termed an ‘in-group wink’.Footnote80 Moreover, the church setting, the sexualised behaviour, and the conservative attire served as a satirical reminder of the stereotypical roles forced on women.

Alongside challenging stereotypes, opponents were also teased. A segment at the end of Act One was devoted to reading out letters from the Church Times, to ridicule some of the more extreme statements made by opponents. A letter from Canon John Chapman, from Surrey typifies the misogyny that activists were navigating:

A man is not a woman, nor a woman a man. Each sex is utterly different in spirit, mind and body. Each has his or her particular sphere of work. In latter days a few women have penetrated into jobs pioneered by men, such as in schools, colleges, science, raiment, but they still gaze pathetically towards the male when the car won’t go. A few women today seek priesthood also. A few, I say, because the idea is obnoxious to the great majority of them.Footnote81

During this segment of the performance, in which familiar insults were recounted, the audience was invited to engage in a collective eye roll and reflect on their own encounters with ecclesiastical misogyny.

The performance concluded in the release of balloons and streamers into the audience, a colourful and joy-filled culmination to close the show. Reflecting on these types of performances, Margaret Webster, one of MOW’s Executive Secretaries, explained that: ‘To be able to laugh so much at what had seemed so threatening showed us once and for all the power of humour to take away fear’.Footnote82 For many of those involved in the campaign for women’s ordination their activism felt dangerous and transgressive as they had been raised to view clergymen as their fathers-in-God. Speaking directly to these concerns Monica Furlong opined that:

there will always be siren voices raised to say that if only we are quiet, sweet, obedient, submissive, humble, then those who would otherwise be hostile towards us will vote for us, whereas if we show ourselves to be strong they will vote against us.Footnote83

She cautioned her audience ‘Don’t believe a word of it’.Footnote84 Performances like ‘Another After Eve’ therefore sought to embolden supporters, to cultivate intimacy amongst activists through giving vent to common insults levied against women, and to provide light relief during a long and arduous campaign.

Printed humour

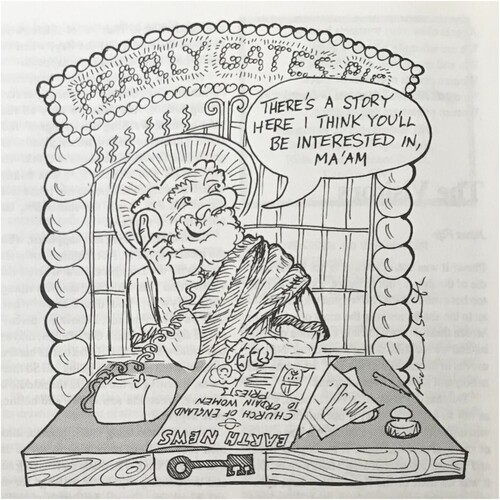

Whilst one-off performances like ‘Another After Eve’ reached a limited audience, MOW’s publications had a much larger circulation. Created in 1986, MOW’s magazine Chrysalis (which was sent to all MOW members and was often left in churches for others to read) quickly became the mouthpiece of the movement. Informative and entertaining, the tone of the magazine combined satire with seriousness. Chrysalis included opinion pieces from members of the movement, book reviews on recently published works of feminist theology, and provided a forum for heated debates about MOW’s tactics in the ‘Letters Page’. The text within the magazine was frequently organised around drawings and cartoons related to the campaign. One of these humorous vignettes, featured in the July 1993 edition, depicted St Peter sat at a desk in front of the ‘Pearly Gates’. A newspaper article is visible on his desk which declares: ‘Earth News Church of England to Ordain Women Priests’. St Peter is shown on the phone to God explaining: ‘There’s a story here I think you’ll be interested in, Ma’am’. By addressing God as ‘Ma’am’ the cartoonist playfully intervened in a much larger theological debate surrounding the practice of using female or non-gendered language such as ‘Mother’, ‘Sister’, ‘Beloved’, or ‘Redeemer’ rather than ‘Father’, ‘Lord’, or ‘Master’ to speak about God.Footnote85 Whilst many supporters of women’s ordination took comfort in traditionally feminine language and images of the divine, which frequently sought to emphasise the maternal, opponents decried such experimentations with religious language.Footnote86 The feminist theologian Janet Morley noted the contradiction evident in the angry expostulations surrounding inclusive language, highlighting the paradoxical insistence that on the one hand the issue was too trivial to be discussed, and on the other hand that to raise the issue was positively satanic.Footnote87 Although it was understood by those on both sides of the debate that God transcended human understandings of gender, the reliance on traditionally male images of God was, and largely still are, deeply ingrained. Cartoons, such as the drawing of St Peter outside the ‘Pearly Gates’, therefore provided a moment of light-relief within a campaign in which women sought to have their lives and lived experiences reflected in their language of worship ().

Figure 4. ‘Pearly Gates’ cartoon, Chrysalis: Women and Religion, July 1993, p.13. TWL/6MOW/11.Orphan Licence: OWLS000401-2.

Yet, instances of printed humour could cause controversy within the movement. Writing under the headline ‘The Other Cheek Department’—a play on the Christian teaching which dictates that one should respond to insults without retort—in the first edition of Chrysalis (Feb 1986), Monica Furlong explained that ‘since misogyny-watching is one of the new sports of the ‘eighties we feel we would like to give space to it’. Furlong asked readers to send examples of misogyny which featured in sermons, diocesan newsletters, and church newspapers (noting that ‘letters columns are often splendid for this’). After considering the various entries, the editors of Chrysalis planned to award ‘the title Misogynist of the Year to the most promising candidate’ on St Jerome’s Day (September 30).Footnote88 Submitted entries included an extract from The Observer in which Rev Geoffrey Kirk, vicar of the Anglo-Catholic and inner-city parish of St Stephen in Lewisham, stated that the idea of a woman priest is ‘like a dog walking on its hind legs with a skirt on. It is impossible and not what the Almighty intended’.Footnote89 The Misogynist of the Year award typified Chrysalis’ frequently irreverent tone. Whilst the letters page suggests that many readers were amused by this tongue-in-cheek response to instances of ecclesiastical misogyny, the award also galvanised critique amongst some MOW members—once again highlighting the subjective nature of humour. Margaret Royle, of Stourport-on-Severn, wrote to inform Chrysalis that the ‘misogyny-watching competition has lost you one member of MOW’. She explained that the competition had confirmed her ‘suspicion that many feminists are looking out for opportunities for retribution or ridicule’. She implored the editors to follow Jesus’s teaching to ‘turn the other cheek’ and ‘get on with the real work’.Footnote90 Petra Clarke, of London, similarly wrote that ‘misogynist hunts’ must be an answer to the ‘prayers’ of those opposed. Imploring MOW to change its tact she asked, ‘Why not be positive and down to earth’.Footnote91 Despite these critiques, the editors remained defiant writing that ‘further contributions for the Misogynist of the Year competition are invited’.Footnote92

Subverting the doctrine of subordination, these female activists invoked a form of topsy-turvy inversion in which those in positions of power within the church were mocked by those barred from obtaining positions of leadership within the ecclesiastical hierarchy. In this sense both the patriarchy (as a commanding structure within the ecclesiastical sphere) and individual patriarchs (bishops and clergy opposed to women’s ordination) became targets of ridicule. By exploring the power inversion evident in these examples of humour it becomes possible to view events like ‘The Festival of Women’ or the ‘Misogynist of the Year’ award as serving as a ‘safety valve’ for tensions within the Anglican church.Footnote93 The ‘safety valve’ metaphor draws on the image of a steam boiler releasing excess steam when the pressure becomes too intense.Footnote94 Frequently used to examine the rituals associated with carnivals in early modern Europe (during which the normal rules of order were disputed, subverted, and mocked), the ‘safety valve’ metaphor is used to demonstrate that these temporary disruptions to the existing social order served to ‘clarify the structure by the process of reversing it’.Footnote95 Yet beyond merely reinforcing existing societal structures, Natalie Zemon Davis has noted that these instances of disorder and unruliness could also serve as a method of breaking taboos—thereby creating a space in which new ideas could be expressed.Footnote96 By applying the ‘safety valve’ metaphor to the campaign for women’s ordination, it becomes possible to view humour and performance as a method purposefully deployed by activists to release tension and frustration at the status quo within the Anglican church, whilst simultaneously cultivating a space for the expression and cultivation of transgressive and challenging ideas.

Conclusion

Whilst the rites and rituals associated with Christianity may appear devoid of humour, religious individuals, families, and communities have inspired comedians and script writers alike (from Derry Girls to Father Ted). The popular BBC comedy series The Vicar of Dibley (1994–2007) followed the inhabitants of a rural Oxfordshire parish as they adjusted to life with a woman priest at the centre of their community. During a memorable scene in the first episode aired in November 1994, mere months after the first women were ordained priests in the Church of England, the Rev Geraldine Granger met the chairman of the parish council, David Horton. His bemusement at her appointment led to the following exchange:

You were expecting a bloke - beard, bible, bad breath.

Yes, that sort of thing.

And instead you got a babe with a bob cut and a magnificent bosom.Footnote97

Geraldine’s frequent references to her body and sexual desires (wryly telling a bishop in series three that she is ‘holy in more ways than one’) challenged and reclaimed the sexualisation and objectification that many activists had endured from both their opponents and the media.Footnote98 Moreover, her deployment of excuses (such as ‘women’s problems of the most dramatic nature’) to avoid tasks repurposed the fears and taboos which had, for so long, governed ideas about women’s bodies. Geraldine’s one-liners and use of physical comedy (from jumping in puddles to diving in chocolate fountains) endeared her to her audience, demonstrating that priests, despite their sacred callings, are not immune to feelings of desire, lust, embarrassment, and awkwardness. The public portrayal of a fleshed out, and in many ways flawed, female priest in the immediate aftermath of a long and drawn-out battle for women’s ordination moreover served to humanise a group of women who had been for decades objects of scorn and ridicule.Footnote99

This article has demonstrated the centrality of humour to the campaign for women’s ordination. In doing so it has sought to untangle the complicated interactions between religion, humour, and feminism. Throughout the article it is possible to decipher two genres of humour used by activists within the campaign: hostile humour (which taunts, mocks, and seeks to highlight the absurdity of one’s opponent, thereby inverting inherent power imbalances) and hopeful humour (jokes, wordplay, and wit which seeks to envisage a better, more hopeful future). Whilst exploring these two genres, this article has paid particular attention to the various placards, T-shirts, and tea towels, which were used as eye-catching canvases for activist messaging. In doing so, it has demonstrated how useful the lens of material culture can be in unravelling experiences of campaigning. It has also demonstrated that activists involved in the campaign for women’s ordination drew on an established tradition of using humour to draw attention to their cause. Like their suffragist and suffragette foremothers, these women used humour as a ‘deliberate tactic’ to ‘diffuse hostility’, and ‘give vent to critical feelings in a comparatively safe manner’.Footnote100 By situating the activists involved in the campaign for women’s ordination within a longer lineage of women’s activism, this article has additionally sought to expand our understandings of post-1968 women’s activism by exploring the oft-overlooked activism of older, religious women. In doing so it has drawn attention to the role religion continued to play in the lives of modern Britons, proving that women could be both pious and political, and encouraging historians to diversify their definitions of women’s ‘activism’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Grace Heaton

Grace Heaton is an historian of modern Britain, with a particular interest in gender, religion, and activism during the twentieth century.

Notes

1 Monica Furlong ‘Exploring for divine newness II’ 1988/9, 6MOW/6/3, The Women’s Library (hereafter TWL).

2 Ibid. See also, Barbara H. Rosenwein, Anger: The Conflicted History of an Emotion (Yale, 2020).

3 ‘Uppity’, Oct 1992, 6MOW/23/2, TWL.

4 The General Synod is comprised of three houses: the House of Laity, the House of Clergy, and the House of Bishops. By 1992 women sat in both the houses of laity and clergy (in their capacity as deacons) and were thus able to vote on legislative matters like the Priests (Ordination of Women) Measure.

5 The Bishops and Priests (Consecration and Ordination of Women) Measure, which enabled women to enter the highest echelons of the church’s hierarchy, was passed in 2014.

6 Caitríona Beaumont, ‘Citizens Not Feminists: The Boundary Negotiated Between Citizenship and Feminism by Mainstream Women’s Organisations in England, 1928–39’, Women’s Historical Review 9, no. 2 (2000): 413. See also, Beaumont’s article in this Special Issue: ‘“What We Think on Questions of Interest to Women” (Six Point Group 1965): Hazel Hunkins Hallinan and Intergenerational Female Activism in England, 1960s–1982’.

7 For more on the British Christian feminist movement generally, and the campaign for women’s ordination specifically, see: Jenny Daggers, The British Christian Women’s Movement: A Rehabilitation of Eve (London, 2018); Susan Mumm, ‘Women, Priesthood, and the Ordained Ministry in the Christian Tradition’, in Religion in History: Conflict, Conversion, and Coexistence, ed. John Wolffe (Manchester, 2004), 190–216; Jessica Thurlow, ‘The “Great Offender”: Feminists and the Campaign for Women’s Ordination’, Women’s Historical Review 23 (2014): 480–99; Grace Heaton, ‘Christian Feminism? Women Against the Ordination of Women and the St Hilda Community, 1986–1992’, Historical Research 96, no. 271 (2022): 124–37. See also: ‘It Did Get Tiring to Welcome Everyone to the Fire—Politics and Spirituality at Greenham Common Peace Camp’, https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/observingthe80s/2013/11/08/it-did-get-tiring-to-welcome-everyone-to-the-fire-politics-and-spirituality-at-greenham-common-peace-camp/ (accessed March 15, 2024).

8 Sheila Fletcher, Maude Royden: A Life (Oxford, 1989); Susan Pederson, ‘Turbervill, Edith Picton-’, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-45465 (accessed July 14, 2022); Ursula Roberts, Living in Two Worlds: The Autobiography of Ursula Roberts (London, 1984). For more on religion and suffrage see: Robert Saunders, ‘“A Great and Holy War”: Religious Routes to Women’s Suffrage, 1909–1914’, English Historical Review 134, no. 571 (2019): 1471–502; Lyndsey Jenkins, ‘“Where the Church had Refused to Perform its Duty the Women Themselves Came Forward”: the Prayer Campaign of the Women’s Social and Political Union, 1913–1914’, Journal of Social History 19, no. 2 (2022): 161–84; Carmen M. Mangion, ‘Religious Suffrage Societies’, in Women’s Suffrage, ed. Krista Cowman (Forthcoming). See also, ‘Special Issue: Challenging Women’, Women’s History Review 29, no. 4 (2020).

9 Timothy Willem Jones, ‘“Unduly Conscious of Her Sex”: Priesthood, Female Bodies, and Sacred Space in the Church of England’, Women’s History Review 21, no. 4 (2012): 639–56.

10 Midori Yamaguchi, ‘The Religious Rebellion of a Clergyman’s Daughter’, Women’s History Review 16, no. 5 (2007): 641–60; Sue Anderson-Faithful, ‘Aspects of Agency: Change and Constraint in the Activism of Mary Sumner, Founder of the Anglican Mothers’ Union’, Women’s History Review 28, no. 6 (2019): 835–52.

11 A. Maude Royden, Women and the Church of England (London, 1916), 7.

12 Jones, ‘“Unduly Conscious of Her Sex”’, 640.

13 Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (London, 2002).

14 Christina Rees, Voices of the This Calling: Experiences of the First Generation of Women Priests (Norwich, 2020), 18–19.

15 Periods of latency do not, necessarily, equate to activist inactivity—see for example Caitríona Beaumont, Louise Ryan, and Mary Clancy, ‘Networks as “Laboratories of Experience”: Exploring the Life Cycle of the Suffrage Movement and its Aftermath in Ireland 1870–1937’, Women’s History Review 29, no. 6 (2020): 1054–74. For an insight the activism surrounding women’s ordination in the 1940s and 1950s see Thurlow, ‘The “Great Offender”’, 480–99.

16 The Lambeth Conference 1968: Resolutions and Reports (London, 1968), 39–40.

17 However, by early 1980 MOW had forged a formal allegiance with the Fawcett society, and by the 1990s MOW was a member of the National Alliance of Women’s Organisations.

18 The vote failed in the House of Clergy.

19 Interview with Sally Barnes conducted by Grace Heaton.

20 The Times, ‘And the Bishops Passed by On the Other Side’, 3 July 1980.

21 Grace Heaton, ‘Radical Object: Campaign for Women’s Ordination Badges’, History Workshop, August 2021.

22 Bob Nicholson and Mark Hall, ‘Building The Old Joke Archive’, in The Palgrave Handbook of Humour, History and Methodology, ed. Daniel Derrin ad Hannah Burrows (Cham, 2020), 499–514.

23 The Cartoonist John Ryan, who produced an array of cartoons for the Catholic Herald which offered commentary on contemporary controversies like the 1968 papal encyclical Humanae Vitae (which reaffirmed the Catholic church’s rejection of artificial birth control) is a good example of this. See Alana Harris, Sink or Swim, p. v. For more on Humane Vitae see Alana Harris, ed., The Schism of ’68: Catholic Contraception and ‘Humanae Vitae’ in Europe, 1945–1975 (2018).

24 Anna Frey, ‘Introduction’, in Who’s Laughing Now?, ed. Anna Frey (Ontario, 2021), 1–5.

25 Notably, these passages were also used by suffragists to legitimise their cause. See, Robert Saunders, ‘“A Great and Holy War”: Religious Routes to Women’s Suffrage, 1909–1914’, English Historical Review 134, no. 571 (2019): 1471–502.

26 Continuing this trend, in recent years feminist theologians have sought to reimagine and re-tell the life stories of these women. See, Paula Gooder, Lydia (London, 2022) and Paula Gooder, Phoebe: A Story (With Notes): Pauline Christianity in Narrative Form (London, 2018).

27 Moreover, Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical of 1896 (Apostolicae Curae) had already declared Anglican Orders invalid, regardless of whether women were admitted to them. For more on the opposition to women’s ordination see Heaton, ‘Christian Feminism?’, 124–37.

28 Spare Rib, Issue 55, p. 4.

29 Susan Dowell and Jane Williams, Bread, Wine and Women: Ordination Debate in the Church of England (London, 1994), 54–5.

30 Pat Thane, ‘Women and Political Participation in England’, in Women and Citizenship in Britain and Ireland in the Twentieth Century—What Difference did the Vote Make?, ed. Pat Thane and Esther Breitenback (London, 2010), 24.

31 Margaretta Jolly and Sasha Roseneil, ‘Researching Women’s Movements: An introduction to FEMCIT and Sisterhood and After’, Women’s Studies International Forum 35, no. 3 (2012): 128; Thane, ‘Women and Political Participation in England’, 24.

32 Claire Langhamer and Hester Barron, Class of 37. Girls Growing up Before the War (Metro, 2021); Selina Todd, Young Women, Work, and Family in England 1918–1950 (Oxford, 2005). Pat Thane’s work represents a notable exception to this trend. See Pat Thane, Old Age in English History: Past experiences, Present Issues (Oxford, 2000).

33 Charlotte Greenhalgh, Aging in Twentieth-Century Britain (California, 2018), 11.

34 Moreover, MOW’s hierarchical structure (with elected leaders, secretaries, and treasures) promoted ‘leading figures’ in a way that the WLM, which prided itself of a refusal of stars, did not. For more on the WLM’s devoted structure see: Margaretta Jolly and Sasha Roseneil, ‘Researching Women’s Movements: An Introduction to FEMCIT and Sisterhood and After’, Women’s Studies International Forum 35, no. 3 (2012): 128.

35 Margaret Webster, A New Strength, A New Song: Journey to Women’s Priesthood (London, 1994), 47.

36 Margaret Webster, ‘Howard, Dame (Rosemary) Christian’, https://www.oxforddnb.com/display/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-72174;jsessionid=EF88B25C6120CDCC9031614A89508556 (accessed August 22, 2023).

37 Una Kroll, ‘Beyond the Issue of Ordination’, Ecumenical Review 40 (1988): 57–65.

38 Dowell and Williams, Bread, Wine and Women, 47.

39 Una Kroll, ‘An Eventful Journey from Christian Feminism to Christian Humanism’, Women’s History Review 24, no. 6 (2015): 1009.

40 Daggers, The British Christian Women’s Movement, 26.

41 The campaign for women’s ordination was one of many causes championed by Christian women in the late-twentieth century. Activists also, for example, formed a presence at Greenham Common Peace Camp (1981–2000), notably situating themselves at the Violet Gate. Moreover, alongside MOW, other groups emerged such as the Christian Parity Group (founded in 1978); Roman Catholic Feminists (1977); Women in Theology (1983); Catholic Women’s Network (1984). See also: ‘Timeline of the Women’s Liberation Movement’, https://www.bl.uk/sisterhood/timeline (accessed August 22, 2023).

42 Hannah Elias, ‘John Collins, Martin Luther King, Jr, and Transnational Networks of Protest and Resistance in the Church of England During the 1960s’, in The Church of England and British Politics Since 1900, ed. Thomas Rodger, Philip Williamson and Matthew Grimley (Woodbridge, 2020), 279–97.

43 Monica Furlong, Bird of Paradise: Glimpses of Living in Myth (London, 1995), 76.

44 For example, her book Travelling In (London, 1971), which explored her experiences of taking LSD in search of religious transcendence, was banned in Church of Scotland bookshops. Furlong, Bird, 80.

45 Monica Furlong, Divorce: One Woman’s View (London: Mothers’ Union, 1981); Monica Furlong, Shrinking and Clinging (London: Friends Homosexual Fellowship, 1981).

46 For more on the St Hilda Community see: Heaton, ‘Christian Feminism?’, 124–37.

47 Monica Furlong, A Dangerous Delight: Women and Power in the Church (London, 1991).

48 For examples from the late-twentieth century see: Sarah Crook, ‘Confronting Patriarchy: Humour and the British Women’s Liberation Movement, 1968–1992’, in Humour in Times of Confrontations, 1900 to the Present, ed. Shun-liang Chao, Alvin Dahn, and Vivienne Westbrook (London, 2023); Lisa Power, No Bath But Plenty of Bubbles: An Oral History of the Gay Liberation Front 1970–1973 (London, 1995), especially Chapter 11.

49 Krista Cowman, ‘“Doing Something Silly”: The Uses of Humour by the Women's Social and Political Union, 1903–1914’, International Review of Social History 52, no. 15 (2007): 261.

50 Webster, A New Strength, 54.

51 Cowman, ‘“Doing Something Silly”’, 268, 272. Rees, Voices of the This Calling, 20.

52 Gloria Kaufam and Mary Kay Blakely, eds., Pulling Our Own Strings: Feminist Humor & Satire (Indiana, 1980), 13.

53 ‘Mail Order List’, May 1989, 6MOW/6/1, TWL.

54 For an explanation of why the women’s suffrage movement adopted the colours purple, white, and green see: UCL Special Collections, Laurence Housman Collection’, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/library/exhibitions/dangers-and-delusions/votes-for-women (accessed August 12, 2022).

55 It is noteworthy that tea towels, adorned with slogans such as ‘Greet the Dawn: Give Labour Its Chance’ and ‘Mothers Vote Labour’, were also a canvas used by the Labour Party throughout the twentieth century.

56 Kaufam and Blakely, Pulling Our Own Strings, 16.

57 Sara Ahmed, The Promise of Happiness (Durham, 2010), Chapter 2. The act of subverting the traditionally ascribed meaning of objects and ‘recasting them with feminist meaning’ was a commonly used tactic across the world during the 1970s and 1980s. See Delap, Feminisms, 263. See also, Gail Green, ‘Badges’, in Things that Liberate: An Australian Feminist Wunderkammer’, ed. Alison Bartlett and Margaret Henderson (Cambridge, 2013), 31–8.

58 ‘Obituary: Dame Christian Howard’, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/obituary-dame-christian-howard-1089713.html (accessed August 7, 2022).

59 Bartlett and Henderson, ‘What is a Feminist Object?’, 163.

60 Church Times, ‘Women Priests: Battle Hots Up’, 3 November 1978.

61 Sisters, nuns, and deaconess were considered to be members of the Laity rather than the Clergy.

62 Survey of London, Volumes 29 and 30, St James Westminster, Part 1, pp. 31–55.

63 Ben Jackson, Aled Davies, and Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, eds., The Neoliberal Age? Britain Since the 1970s (London, 2021); Jonathan Davis and Rohan McWilliam, eds., Labour and the Left in the 1980s (Manchester, 2018).

64 Church Times, ‘When the Iron Lady Met a Steely Church’, 17 April 2015.

65 Ibid.

66 Donald Reeves, The Memoirs of a ‘Very Dangerous Man’ (London, 2009). For more on Thatcher’s relationship with the Church of England see Eliza Filby, God and Mrs Thatcher: The Battle for Britain’s Soul (London, 2015).

67 For more on the integral role played by male clergy see Grace Heaton, ‘“Smashing the Stained Glass Ceiling”: An Exploration of the Campaign for Women’s Ordination, 1968–1994’ (D. Phil thesis, University of Oxford, 2023), Chapter One.

68 ‘Another After Eve’, 6MOW/6/2, TWL.

69 ‘Press Release’, 17 June 1982, 6MOW/2/2, TWL.

70 Daggers, The British Christian Women’s Movement.

71 ‘Press Release’, 17 June 1982, 6MOW/2/2, TWL.

72 Ibid.

73 ‘Another After Eve’, 6MOW/6/2 (folder 1 of 5), TWL.

74 Jones, ‘“Unduly Conscious of Her Sex”’, 639–56.

75 Susan Dowell and Lind Hurcombe, Dispossessed Daughters of Eve: Faith and Feminism (London, 1981).

76 ‘Another After Eve’, 6MOW/6/2 (folder 1 of 5), TWL.

77 Ibid.

78 Ibid.

79 Ibid.

80 Frey, Who’s Laughing Now?, 2.

81 ‘Another After Eve’, 6MOW/6/2 (folder 1 of 5), TWL.

82 Webster, A New Strength, 61–2.

83 Monica Furlong ‘Exploring for divine newness II’ 1988/9, 6MOW/6/3, TWL.

84 Ibid.

85 Grace Heaton, ‘“The Male God Blessed the Male Patriarchy”: Language, Ritual and the History of Women’s Ordination’, Crucible (April 2020), 14–25.

86 See for example, Graham Leonard, Peter Toon and Iain MacKenzie, Let God Be God (London, 1989).

87 Janet Morley, ‘The Faltering Words of Men’, in Feminine in the Church, ed. Monice Furlong (London, 1984), 60.

88 Chrysalis, February 1986, p. 13. Identified by Furlong as a misogynistic early church father.

89 The Observer 30/03/86 as cited in Chrysalis, June 1986, p. 14.

90 Chrysalis, June 1986, p. 13.

91 Ibid.

92 Ibid., 14.

93 Edward Muir, Ritual in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, 1997), 90–2.

94 Ibid., 90.

95 Natalie Zemon Davis, Society and Culture in Early Modern France: Eight Essays (Stanford, 1975), 130.

96 Ibid.

97 The Vicar of Dibley, Series One, ‘The Arrival’.

98 Upon the passing of the Priests (Ordination of Women) Measure in 1992 The Sun ran the headline ‘The Church says Yes to Vicars in Knickers’—simultaneously trivialising and sexualising those involved. For more see: Sarah-Jane Page, ‘The Scrutinized Priest: Women in the Church of England Negotiating Professional Sacred Clothing Regimes’, Gender, Work, & Organisation 21, no. 4 (2014), 295–307.

99 Church Times, ‘Parish Life on the Small Screen’, 11 September 2020.

100 Cowman, ‘“Doing Something Silly”’, 261.